Abstract

One of the many routes proposed for the cellular inactivation of endogenous nitric oxide (NO) is by the cytochrome c oxidase of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. We have studied this possibility in human embryonic kidney cells engineered to generate controlled amounts of NO. We have used visible light spectroscopy to monitor continuously the redox state of cytochrome c oxidase in an oxygen-tight chamber, at the same time as which we measure cell respiration and the concentrations of oxygen and NO. Pharmacological manipulation of cytochrome c oxidase indicates that this enzyme, when it is in turnover and in its oxidized state, inactivates physiological amounts of NO, thus regulating its intra- and extracellular concentrations. This inactivation is prevented by blocking the enzyme with inhibitors, including NO. Furthermore, when cells generating low concentrations of NO respire toward hypoxia, the redox state of cytochrome c oxidase changes from oxidized to reduced, leading to a decrease in NO inactivation. The resultant increase in NO concentration could explain hypoxic vasodilation.

Keywords: hypoxia, mitochondrial respiration, nitric oxide inactivation, nitric oxide synthase

Despite much research on its metabolic fate, the way in which the concentration of nitric oxide (NO) is regulated in cells and tissues is at present unresolved. Many routes for its inactivation have been discussed, including interaction with superoxide ions (1), hemoglobin (2–4) or myoglobin (5), accelerated autoxidation favored by partition within cell membranes (6), and interactions with free radicals derived from eicosanoid lipoxygenase (7), cyclo-oxygenase (8), different peroxidases (9), or catalase (10). Interactions with a flavohemoglobin-like NO dioxygenase (11–13) or with an unknown protein (14), and simple partitioning within mitochondrial membranes (15), have also been suggested.

Before the discovery of NO as a biological mediator (16) it had been shown that isolated cytochrome c oxidase, the terminal enzyme in the mitochondrial electron transport chain, catalyzes both the oxidation and reduction of NO (17). More recent evidence has suggested that cytochrome c oxidase may provide a metabolic route for NO, either by interaction of NO with the reduced enzyme, leading to the formation of N2O, (18, 19) or by interaction of NO with the oxidized enzyme, forming nitrite (NO2−; 20, 21). Although the NO reductase activity of the enzyme is too slow to constitute a physiological mechanism for the removal of NO (22), there is strong evidence in favor of the oxidation of NO to NO2− both by the purified enzyme (23, 24) and by cells (25). Nevertheless, the possibility that cytochrome c oxidase constitutes a significant metabolic route for NO remains controversial (26, 27) and has been directly challenged (28).

Clarifying the route(s) of the cellular inactivation of NO will be important for a fuller understanding of its biological functions. We have therefore investigated the role of cytochrome c oxidase in the metabolic fate of NO by using our method based on visible light spectroscopy (see refs. 29–31). This allows us to study cell respiration and the redox state of cytochrome c oxidase at the same time as which we monitor O2 and NO concentrations in cells respiring toward hypoxia in an O2-tight chamber. In most of our studies, we have used a cell system engineered to express an NO synthase under the control of an inducible promoter (32, 33). After induction, the amount of NO generated by this system depends on the concentration of substrate (l-arginine) added. Furthermore the synthesis and release of NO occur within the cells, thus avoiding the use of exogenously administered NO.

Our results indicate that cytochrome c oxidase provides a major route for the inactivation of endogenous NO when this enzyme is in its oxidized state. Furthermore, this inactivation only occurs when the enzyme is in turnover and when the concentration of NO is not sufficient to inhibit the enzyme completely. Cessation of this inactivation mechanism at low [O2] may explain hypoxic vasodilation.

Results

Effect of Hypoxia on the Release of NO.

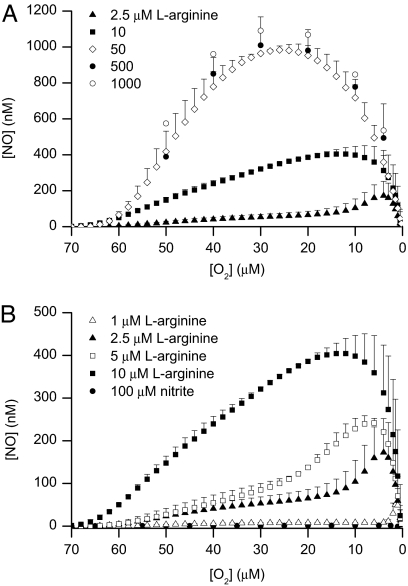

The addition of different concentrations of l-arginine at 70 μM O2 to induced Tet-iNOS-293 cells respiring toward hypoxia in the chamber led to a concentration-dependent release of NO that was maximal after the addition of 50 μM l-arginine (Fig. 1). The release induced by all concentrations of l-arginine was prevented by concomitant administration of a concentration of S-ethylisothiourea (S-EITU) sufficient to inhibit NO synthase (500 μM; data not shown). At concentrations of l-arginine above 10 μM, the release of NO occurred without a delay, reaching a maximum at ≈30 μM O2 and then declining as the [O2] in the chamber fell below 20 μM (Fig. 1A). In contrast, at concentrations of l-arginine below 10 μM, the release of NO was at first gradual, followed by a peak that was not observed until the [O2] fell below 20 μM (Fig. 1B). The lower the concentration of l-arginine, the lower was the [O2] at which the peak of NO was observed (Fig. 1B). The pattern of NO release at both high and low concentrations of l-arginine was unchanged when experiments were carried out in the presence of superoxide dismutase (500 units) administered immediately before the start of the experiment (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Release of NO from high and low concentrations of l-arginine. (A and B) Release of NO from induced Tet-iNOS-293 cells respiring toward hypoxia in a closed chamber after the addition of different concentrations of l-arginine at 70 μM O2 (n = 5–6). The filled circles in B show the lack of release of NO when nitrite (100 μM) was added at 70 μM O2 (n = 3).

Nitrite Reduction Does Not Contribute to the Release of NO in Hypoxia.

To determine the cause of the increase in NO release at low [O2], we first established whether the NO might be coming from a source other than NO synthase. Nitric oxide generated by the cells and released into the extracellular fluid is mainly oxidized to NO2− (34). In our experiments, the release of NO led to a progressive accumulation of NO2− in the chamber (6.2 ± 2.2 μM per 107 cells in 15 min when 100 μM l-arginine was added, n = 3), which was proportional to the amount of l-arginine added and therefore to NO released. One possibility, therefore, is that the release of NO at low [O2] was caused by the reduction of this accumulated NO2− back to NO, as has been suggested (35). If this were the mechanism, then the peak of NO observed at low [O2] would occur even at the higher concentrations of l-arginine and would be proportional to the amount of this substrate, which was not the case. Nevertheless, we carried out experiments in which a high concentration (100 μM) of NO2− instead of l-arginine was added at 70 μM O2 to cells that had been treated with digitonin (100 μg·ml−1), which disrupts the cells to ensure the uptake of NO2− without affecting oxidative phosphorylation (see ref. 36). Fig. 1B shows that there was no release of NO from this concentration of NO2− at any [O2].

Involvement of Cytochrome c Oxidase.

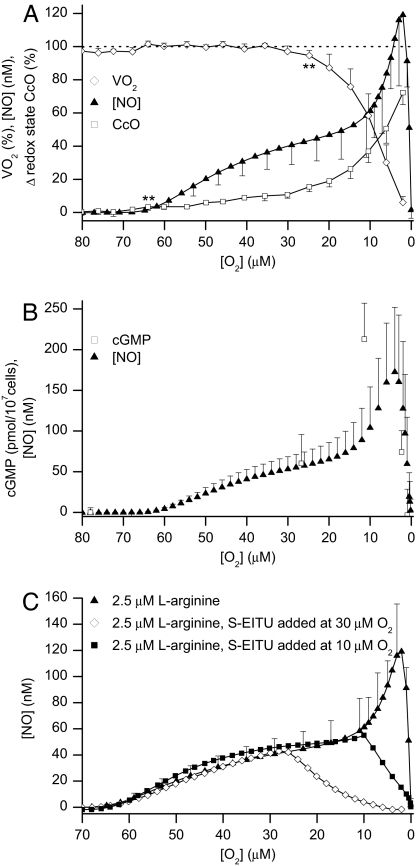

An alternative explanation for the peak of NO observed at low [O2] is that it is the result of decreased inactivation of NO by cytochrome c oxidase, which, as the [O2] decreases in the chamber, changes from an oxidized to a more reduced state. To evaluate this possibility we investigated in more detail the release of NO from cells treated with 2.5 μM l-arginine. This is also one of the concentrations of substrate at which we have shown that NO produces a reduction of cytochrome c oxidase without affecting the rate of O2 consumption (VO2) (31). Fig. 2A shows that the addition of 2.5 μM l-arginine produced a reduction of cytochrome c oxidase, which became significant at 64 ± 0.7 μM O2 without affecting VO2. VO2 decreased significantly only when the [O2] fell to 25 ± 0.8 μM. The reduction of cytochrome c oxidase occurred in two distinct phases, namely, a slow initial phase followed by a faster reduction at an [O2] below 20 μM. Thus, the profile of the release of NO resembled the reduction of the enzyme. Furthermore, when activation of soluble guanylate cyclase was used to monitor changes in the intracellular concentration of NO, an increase in cGMP production was observed as the [O2] fell below 20 μM, preceding the peak of NO detected by the NO electrode (Fig. 2B). This finding indicates that the instantaneous and continuous measurement of NO in the extracellular fluid, before the intervention of any degradation process that might occur outside the cell, reflects its intracellular concentration. When S-EITU was added at 30 or at 10 μM O2 to cells treated with 2.5 μM l-arginine, all further release of NO was abolished (Fig. 2C). Thus, all of the NO detected, including the peak observed at low [O2], derived from de novo synthesis by an active NO synthase rather than from conversion of NO2− to NO.

Fig. 2.

Release of NO correlates with reduction of cytochrome c oxidase and activity of soluble guanylate cyclase, and is inhibited by S-EITU. (A) Changes in VO2 (open diamonds), release of NO (filled triangles), and reduction of cytochrome c oxidase (CcO, open squares) after the addition of 2.5 μM l-arginine. ** indicates where the decrease in VO2 or the reduction of cytochrome c oxidase becomes significant (P < 0.01, n = 6). (B) Release of NO and changes in cGMP concentration after the addition of 2.5 μM l-arginine (n = 6). (C) Release of NO from cells treated with 2.5 μM l-arginine, either alone (filled triangles, n = 6) or when S-EITU (500 μM) was added at 30 μM O2 (open diamonds) or at 10 μM O2 (filled squares). S-EITU traces are representative of five similar experiments.

Inactivation of Exogenous NO.

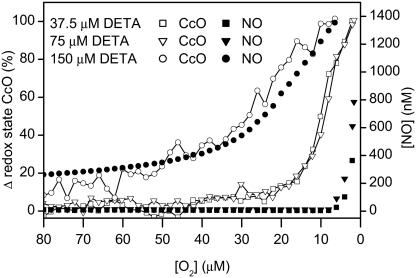

We next studied the fate of NO generated by the breakdown of the NO donor diethylenetriamine (DETA)-NO, which releases NO for long periods in an O2-independent manner. This approach enabled us to monitor the fate of NO, unrelated to the action of NO synthase. Noninduced Tet-iNOS-293 cells were incubated with a range of concentrations of DETA-NO that we established would release amounts of NO that would be fully or partially inactivated by cytochrome c oxidase in its oxidized state. While the [O2] remained above 20 μM, there was virtually no detectable release of NO from cells treated with 37.5 and 75 μM DETA-NO. In contrast, administration of 150 μM DETA-NO resulted in a detectable release of NO at high [O2]. However, in all cases, as the [O2] in the chamber decreased and cytochrome c oxidase became reduced there was a significant increase in the amount of NO detected (Fig. 3). These changes occurred at a higher [O2] in the presence of 150 μM DETA-NO than at the lower concentrations of NO donor. Thus, there was a clear correlation between reduction of cytochrome c oxidase and its decreased capacity to inactivate NO.

Fig. 3.

Reduction of cytochrome c oxidase (CcO, open symbols) and release of NO (filled symbols) at low [O2] from noninduced Tet-iNOS-293 cells respiring toward hypoxia in the presence of 37.5 (squares), 75 (triangles), and 150 μM (circles) DETA-NO. Traces are representative of three similar experiments.

The Redox State of Cytochrome c Oxidase Determines the Inactivation of NO.

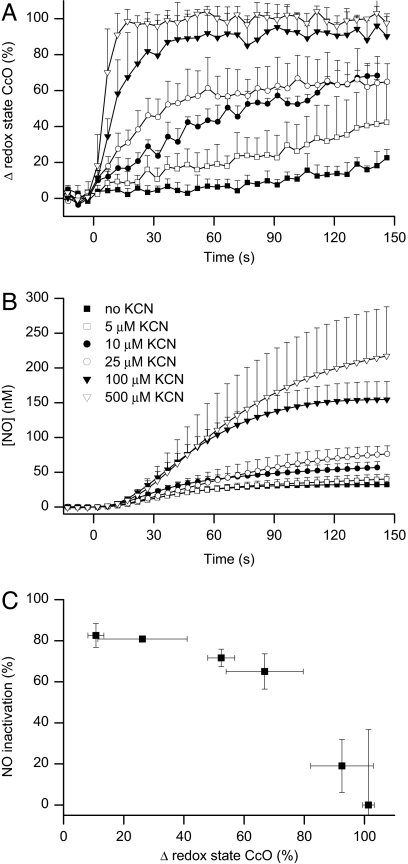

To substantiate these observations, we examined the effect of different concentrations of cyanide (KCN; 5–500 μM) on the redox state of cytochrome c oxidase and the release of NO from 2.5 μM l-arginine. These concentrations of KCN neither activated nor inhibited NO synthase under our experimental conditions (data not shown). KCN, given concomitantly with 2.5 μM l-arginine at 70 μM O2, resulted in a concentration-dependent reduction of cytochrome c oxidase (Fig. 4A) and a concentration-dependent release of NO (Fig. 4B). To demonstrate the relationship between these two parameters we compared them both at the arbitrary time of 100 s after the addition of l-arginine. The percentage inactivation of NO for each concentration of KCN was calculated (see Experimental Procedures) and compared with the percentage reduction of the enzyme (Fig. 4C). Addition of 500 μM KCN at 70 μM O2 to cells incubated with DETA-NO also resulted in an immediate reduction of cytochrome c oxidase, together with a rapid increase in the amount of NO detected (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Correlation between redox state of cytochrome c oxidase and inactivation of NO in KCN-treated cells. Effect of KCN on the redox state of cytochrome c oxidase (A) and the release of NO (B) from induced Tet-iNOS-293 cells treated with 2.5 μM l-arginine. Both KCN (5–500 μM) and l-arginine were added at 70 μM O2. (C) Shows the correlation between the percentage reduction of the enzyme and its inability to metabolize NO (n = 3).

These experiments indicate that cytochrome c oxidase in its oxidized state continuously inactivates NO, a process that does not occur when the enzyme is inhibited by KCN. Furthermore, the fact that the NO concentration increases when KCN inhibits O2 consumption (and therefore increases the available [O2]) argues against any contribution of extracellular O2-dependent oxidation to the inactivation of NO in our experiments, because this would be expected to increase at higher [O2], resulting in less rather than more NO in the presence of KCN.

The experiments above suggest that increasing the concentration of NO should progressively decrease its own inactivation by inhibiting and thus reducing cytochrome c oxidase. To demonstrate this we compared the release of NO produced by increasing concentrations of l-arginine in the presence or absence of 500 μM KCN. The differences in NO release, again measured at 100 s after the addition of l-arginine, were used to estimate the percentage inactivation of NO for each concentration of l-arginine. Although the results calculated in this way grossly underestimate the phenomenon, they do show that increasing concentrations of NO progressively inhibit its inactivation by cytochrome c oxidase (85 ± 11%, 48 ± 2%, and 6 ± 2% inactivation at 2.5, 10, and 100 μM l-arginine, respectively).

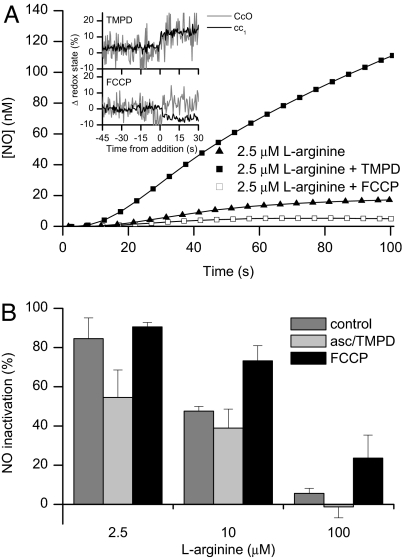

We next decided to manipulate cytochrome c oxidase pharmacologically to determine the relationship between the redox state and turnover of the enzyme and its capacity to inactivate NO. We used N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine (TMPD) and ascorbate to increase the electron flow in cytochrome c oxidase, increasing the turnover of the enzyme while also increasing its reduced state (see ref. 31 and Fig. 5A Inset). The addition of 180 μM TMPD and 6 mM ascorbate increased the VO2 from 12.9 ± 1.5 to 23.3 ± 1.2 μM·min−1 per 107 cells and the turnover from 50–60 to 80–100 e− per second. Under these conditions there was less inactivation of NO (Fig. 5A). The use of carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP, 1 μM), however, which uncoupled the electron transport chain, increasing the VO2 from 12.9 ± 1.5 to 21.4 ± 2.8 μM·min−1 per 107 cells and the turnover from 50–60 to 80–100 e− per second without reducing cytochrome c oxidase (see Fig. 5A Insert), actually increased the inactivation of NO generated from the same concentration of l-arginine (Fig. 5A). Fig. 5B shows the effects of TMPD and FCCP on the percentage inactivation of the NO generated by 2.5, 10, and 100 μM l-arginine. These experiments indicate that the turnover of cytochrome c oxidase and its redox state are responsible for the fine-tuning of cellular NO concentrations.

Fig. 5.

Effect of changes in redox state on inactivation of NO. (A) The release of NO from induced Tet-iNOS-293 cells treated with 2.5 μM l-arginine in the absence or presence of 180 μM TMPD plus 6 mM ascorbate or of 1 μM FCCP. (Inset) The redox state of cytochrome c oxidase (CcO, gray line) and its substrate cytochrome c (cc1, black line) before and after the addition of TMPD plus ascorbate or of FCCP. Traces are representative of three similar experiments. (B) The percentage inactivation of NO generated by different concentrations of l-arginine alone, in the presence of 180 μM TMPD and 6 mM ascorbate, or in the presence of 1 μM FCCP. The degree of inactivation was calculated as described in Experimental Procedures. (n = 3). A two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test showed that there were significant (P < 0.05) differences in NO inactivation among treatments (control, asc/TMPD, FCCP) and among l-arginine (2.5, 10, 100 μM) concentrations.

Discussion

By using a system that allows us to monitor a variety of parameters in cells respiring toward hypoxia, we have investigated the metabolic fate of NO. Nitric oxide was detected either by an electrode in the chamber where the cells were suspended or by the activity of soluble guanylate cyclase within the cells, giving an indication of the kinetics of NO once it had been generated by NO synthase.

Our results show that, in respiring cells, cytochrome c oxidase, in its oxidized state, constantly inactivates NO and thus regulates its intracellular concentration. This activity is prevented when the enzyme is inhibited (and therefore reduced) by KCN or NO itself or when it is reduced at low [O2]. The experiments using TMPD and ascorbate, or FCCP, further demonstrate that increases in turnover leading to similar rates of O2 consumption result in different inactivation rates of NO, depending on the redox state of the enzyme.

Thus, the metabolic fate of NO is determined by the subtle interplay between, on the one hand, the flux (i.e., change in concentration over time) of NO generated by NO synthase and, on the other hand, the redox state, turnover, and [O2] at which cytochrome c oxidase is operating. Therefore, this is a finely tuned mechanism that regulates intracellular concentrations of NO, operates efficiently at physiological or near-physiological NO fluxes, and is likely to take precedence over any of the other mechanisms previously identified for the inactivation of NO (see the introduction). Nevertheless, the relative importance of the various inactivating mechanisms needs to be determined, preferably in systems in which the three key enzymes, namely, NO synthase, cytochrome c oxidase, and soluble guanylate cyclase, are allowed to interact in the processing of endogenously generated NO. The use of NO donors alone, with all its attendant pitfalls, is unlikely to provide significant new information in relation to these interactions.

Our results shed light on the possible operation of this system of enzymes in two particular situations. In the first situation, the [O2] is not critical. We have previously demonstrated that increases in [NO] relative to [O2] that are not yet sufficient to inhibit respiration reduce cytochrome c oxidase and that the recruitment of excess capacity of this enzyme is able to maintain O2 consumption in the cell (31). Only when the NO:O2 ratio increases to a point at which this excess capacity is fully used does inhibition of respiration ensue. In this situation, the generation of NO will not be compromised because NO synthase will be operating at a noncritical [O2] and therefore the main determinant of the [NO] in and outside the cell will be the varying capacity of cytochrome c oxidase to inactivate NO, the latter ceasing when the enzyme is fully inhibited. Thus, in situations in which a high rate of NO generation leads to inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase, one would expect a lack of inactivation of NO that may lead to nonphysiological interactions.

The second situation is one in which the [O2] decreases to critical levels, such as occurs in our O2-tight chamber. The reported Km of NO synthase for O2 varies widely, from 6–23 μM (37) up to 135–400 μM (38). However, in our hands S-EITU was able to inhibit NO release even when given at an [O2] as low as 10 μM, indicating that NO synthase remains active in the cells at very low [O2]. This has been observed in other preparations (see ref. 39). Although we have not carried out detailed studies of the activity of NO synthase and the fluxes of NO it generates at low [O2], one possible explanation for its activity in cells at this unexpectedly low [O2] is that, as the inactivation of NO decreases at low [O2], it inhibits respiration, thus diverting O2 toward NO synthase in a process akin to that which we have described for the prolyl hydroxylases (40).

In a similar manner, the reduction and therefore inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase at low [O2] diverts the NO, which is now not inactivated, toward soluble guanylate cyclase and to other targets within and outside the cell. This would explain the release of NO that we observe at low [O2]. The fate of the NO interacting with the now reduced cytochrome c oxidase remains an interesting question. Determining whether the enzyme shows any NO reductase activity in cells, or whether the NO remains attached to the enzyme in a semistable situation (see refs. 23 and 24), will further help our understanding of the responses of tissues to hypoxia.

Recently there has been a great deal of interest in the possibility that NO might be generated by sources other than directly from NO synthase. The most widely discussed suggestions are that S-nitrosated hemoglobin (SNO-Hb) releases S-nitrosothiols during deoxygenation (41) or that hemoglobin is an allosteric regulated heme-based nitrite reductase that reduces NO2− to NO as hemoglobin deoxygenates (42). Both of these mechanisms have been suggested to explain hypoxic vasodilation. Reduction of NO2− to NO by a variety of other mechanisms has also been proposed (35, 43–45). Although our results do not directly challenge any of these interesting possibilities, they do show that the concentrations of locally generated NO are regulated by cytochrome c oxidase in an O2-dependent manner. The amount of available NO clearly increases at low [O2] when the activity of cytochrome c oxidase decreases. This NO is detected by soluble guanylate cyclase, showing the interplay between the enzymes to regulate the concentration of NO. The NO that we detect at low [O2] is all synthesized de novo by an active NO synthase; this suggests that any claim about the physiological relevance of NO generated from NO2− in cells, tissues, or in vivo should be reevaluated in relation to the present evidence.

Impaired inactivation of NO by cytochrome c oxidase could account for the numerous reports of an increase in local NO concentration after a decrease in [O2], both in vitro and in vivo (see ref. 46). Furthermore, it could explain hypoxic vasodilation as a process independent of the release of S-nitrosothiols (41) or of the reduction of NO2− to NO by hemoglobin or by any of the other mechanisms proposed (47, 48).

Experimental Procedures

Reagents.

Cell culture medium, hygromycin B, and trypsin-EDTA were purchased from Invitrogen. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich except blasticidin, which was obtained from Calbiochem.

Cell Culture and Induction of Human NOS in Tet-iNOS-293 Cells.

The tetracycline-inducible human embryonic kidney cell line Tet-iNOS-293, which stably expresses the NOS from human chondrocytes, was obtained as described in ref. 33. Maximal expression of NOS in Tet-iNOS-293 cells was achieved by 15 h incubation with induction medium (DMEM, 10% HI-FBS, 1.5 μg·ml−1 tetracycline, and 500 μM S-EITU). Induced cells were harvested and counted as described in ref. 31, then placed in a water bath at 37°C before measurement in the visible light spectroscopy (VLS) chamber.

Simultaneous Measurement of Cytochrome Redox States, [O2], and [NO] Generated from Exogenous l-Arginine During Cellular Respiration.

The VLS system was the same as described in refs. 29–31. In brief, measured changes in optical attenuation were converted into changes in the redox states of the mitochondrial cytochromes by two multiwavelength linear least-squares fits of their specific absorption coefficients (29). A first-order background was included in the least-squares fitting algorithm to account for nonabsorption changes (31). Calibration and operation of the Clark-type O2 electrode (Rank Brothers) and the NO electrode (amiNO-700, Innovative Instruments) have also been described (29–31).

The absorption spectrum of cytochrome c oxidase is a combination of the spectra of cytochrome a (heme a) and cytochrome a3 (heme a3), with the major contribution (80–90%) coming from cytochrome a (29). For convenience, we refer to the measurement of the redox state of cytochromes aa3 as the redox state of cytochrome c oxidase, which is expressed as a percentage change from the steady state at initial high [O2] to that at hypoxia. When the enzyme is in turnover and [O2] is not affecting its steady state, the catalytic center of cytochrome c oxidase (cytochrome a3-CuB) is mainly populated by the oxidized species (O, P, and F). We refer to this situation as cytochrome c oxidase being oxidized or in its oxidized state. As cells respire toward hypoxia, the enzyme becomes more and more reduced as the catalytic center is increasingly populated by reduced species E and R until cytochromes aa3 reach maximal reduction, as is found when dithionite is added to the purified preparation of cytochrome c oxidase. Furthermore, any disturbance in the catalytic center of cytochrome c oxidase, such as inhibition of electron turnover, will consequently increase the accumulation of electrons in cytochrome a and produce an increase in its reduced form, as is observed at hypoxia (31). We refer to both these situations, an accumulation of electrons at cytochrome a or an increase in reduced species at the catalytic center, as cytochrome c oxidase becoming more reduced.

l-Arginine was always added as close as possible to the point at which the [O2] in the chamber reached 70 μM. This [O2] was selected because the redox state of cytochromes aa3 and cc1 remain independent of [O2] above ≈50 μM (31) and to ensure that the [O2] was sufficient to sustain the activity of NO synthase (37, 38, 49).

Formation of Nitrite Inside the VLS Chamber.

The formation of nitrite from the addition of l-arginine to cells respiring in the VLS chamber was measured by extracting 10 μl of cell suspension at the beginning and at the end of the respiration trace and injecting them into a second chamber fitted with an amiNO-700 NO sensor and containing 10 mM KI and 100 mM H2SO4. The nitrite concentration was calculated by comparing the observed change in current with that of a nitrite standard.

Measurement of cGMP.

cGMP activity was measured by enzyme immunoassay system for intracellular cGMP, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Bioscience). Cell samples (5 μl; ≈0.8 × 105 cells) were taken from the VLS chamber and further diluted with 500 μl of lysing reagent. Values of cGMP were normalized to the cell number of each sample in the VLS chamber and expressed as picomoles per 107 cells.

Release of NO from DETA-NO.

DETA-NO (37.5, 75, and 150 μM) was used to generate NO. In the absence of cells, these concentrations of DETA-NO released ≈70, 260, and 565 nM NO, respectively, in the VLS medium over a period of 5 min. Noninduced cells were then incubated in the chamber for 5 min with each concentration of DETA-NO, the chamber was closed, and the cells were allowed to respire toward hypoxia. In some of these experiments KCN was administered at 70 μM O2 and the release of NO was monitored.

Inactivation of NO by Cytochrome c Oxidase in Respiring Cells.

To estimate the degree of inactivation of NO by cytochrome c oxidase per unit of time, we carried out experiments in which induced Tet-iNOS-293 cells were placed in the VLS chamber and different concentrations of l-arginine in the presence or absence of 500 μM KCN were added at 70 μM O2. Measurement of NO was carried out 100 s after the addition of l-arginine. The percentage inactivation of NO by cytochrome c oxidase was calculated as: 100 × (b − a)/b, where a and b are concentrations of NO in the absence and presence of 500 μM KCN, respectively. In other experiments the percentage inactivation of NO generated from 2.5 μM l-arginine was estimated in the presence of different concentrations of KCN (5–500 μM). In this case, the percentage inactivation was calculated as 100 × (b − c)/b, where b is the concentration of NO in the presence of 500 μM KCN and c is the concentration of NO in the presence of the lower concentration of KCN. A value of 500 μM was selected as the concentration of KCN required to prevent completely the inactivation of NO, based on titration of the effect of different concentrations of KCN on the redox state of cytochrome c oxidase.

Statistical Analysis.

Means ± standard deviations were calculated for quantitative analysis of the results. The number of samples in each experimental group is indicated in the related text. The (two-tailed) Z-test was used to determine statistically significant (P < 0.01) changes in VO2 and the reduction of cytochrome c oxidase. NO inactivation data were evaluated by using a two-way ANOVA, using Tukey's test for post hoc analysis to determine statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

Acknowledgments

We thank Annie Higgs for critically reviewing the manuscript. This work was supported, in part, by European FP6 Funding (LSHM-CT-2004-0050333).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gryglewski RJ, Palmer RMJ, Moncada S. Nature. 1986;320:454–456. doi: 10.1038/320454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lancaster JR., Jr Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8137–8141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu X, Miller MJ, Joshi MS, Sadowska-Krowicka H, Clark DA, Lancaster JR., Jr J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18709–18713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelm M, Feelisch M, Spahr R, Piper HM, Noack E, Schrader J. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;154:236–244. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(88)90675-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunori M. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:21–23. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01698-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu X, Miller MJ, Joshi MS, Thomas DD, Lancaster JR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2175–2179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffey MJ, Natarajan R, Chumley PH, Coles B, Thimmalapura P-R, Nowell M, Kühn H, Lewis MJ, Freeman BA, O'Donnell VB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8006–8011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141136098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Donnell VB, Coles B, Lewis MJ, Crews BC, Marnett LJ, Freeman BA. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38239–38244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abu-Soud HM, Hazen SL. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37524–37532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.48.37524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunelli L, Yermilov V, Beckman JS. Free Rad Biol Med. 2001;30:709–714. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00512-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardner PR, Martin LA, Hall D, Gardner AM. Free Rad Biol Med. 2001;31:191–204. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hallstrom CK, Gardner AM, Gardner PR. Free Rad Biol Med. 2004;37:216–228. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt K, Mayer B. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffiths C, Yamini B, Hall C, Garthwaite J. Biochem J. 2002;362:459–464. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiva S, Brookes PS, Patel RP, Anderson PG, Darley-Usmar VM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:7212–7217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131128898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmer RMJ, Ferrige AG, Moncada S. Nature. 1987;327:524–526. doi: 10.1038/327524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brudvig GW, Stevens TH, Chan SI. Biochemistry. 1980;19:5275–5285. doi: 10.1021/bi00564a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clarkson RB, Norby SW, Smirnov A, Boyer S, Vahidi N, Nims RW, Wink DA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1243:496–502. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(94)00181-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borutaite V, Brown GC. Biochem J. 1996;315:295–299. doi: 10.1042/bj3150295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao X-J, Sampath V, Caughey WS. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;212:1054–1060. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torres J, Cooper CE, Wilson MT. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8756–8766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stubauer G, Giuffrè A, Brunori M, Sarti P. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;245:459–465. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giuffrè A, Barone MC, Mastronicola D, D'Itri E, Sarti P, Brunori M. Biochemistry. 2000;39:15446–15453. doi: 10.1021/bi000447k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torres J, Sharpe MA, Rosquist A, Cooper CE, Wilson MT. FEBS Lett. 2000;475:263–266. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01682-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearce LL, Kanai AJ, Birder LA, Pitt BR, Peterson J. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13556–13562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109838200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall CN, Garthwaite J. J Physiol. 2006;577:549–567. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.118380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper CE, Giulivi C. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C1993–C2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00310.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shiva S, Oh J-Y, Landar AL, Ulasova E, Venkatraman A, Bailey SM, Darley-Usmar VM. Free Rad Biol Med. 2004;38:297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hollis VS, Palacios-Callender M, Springett RJ, Delpy DT, Moncada S. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1607:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palacios-Callender M, Quintero M, Hollis VS, Springett RJ, Moncada S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7630–7635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401723101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palacios-Callender M, Hollis V, Frakich N, Mateo J, Moncada S. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:160–165. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu W, Liu L, Smith GC, Charles IG. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:339–345. doi: 10.1038/35014028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mateo J, García-Lecea M, Cadenas S, Hernández C, Moncada S. Biochem J. 2003;376:537–544. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feelisch M. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1991;17:S25–S33. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castello PR, David PS, McClure T, Crook Z, Poyton RO. Cell Metab. 2006;3:277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villani G, Greco M, Papa S, Attardi G. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31829–31836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rengasamy A, Johns RA. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;276:30–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dweik RA, Laskowski D, Abu-Soud HM, Kaneko FT, Hutte R, Stuehr DJ, Erzurum SC. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:660–666. doi: 10.1172/JCI1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Land SC, Rae C. Am J Physiol. 2005;289:C918–C933. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00476.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hagen T, Taylor CT, Lam F, Moncada S. Science. 2003;302:1975–1978. doi: 10.1126/science.1088805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stamler JS, Jia L, Eu JP, McMahon TJ, Demchenko IT, Bonaventura J, Gernert K, Piantadosi CA. Science. 1997;276:2034–2037. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cosby K, Partovi KS, Crawford JH, Patel R, Reiter CD, Martyr S, Yang BK, Waclawiw MA, Zalos G, Xu X, et al. Nat Med. 2003;9:1460–1461. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H, Samouilov A, Liu X, Zweier JL. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24482–24489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gautier C, van Faassen E, Mikula I, Martasek P, Slama-Schwok A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:816–821. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiva S, Huang Z, Grubina R, Sun J, Ringwood LA, MacArthur PH, Xu X, Murphy M, Darley-Usmar VM, Gladwin MT. Circ Res. 2007;100:654–661. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000260171.52224.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nase GP, Tuttle J, Bohlen HG. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:H507–H515. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00759.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robinson JM, Lancaster JR., Jr Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:257–261. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.F292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gladwin MT, Raat NJH, Shiva S, Dezfulian C, Hogg N, Kim-Shapiro DB, Patel RP. Am J Physiol. 2006;291:H2026–H2035. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00407.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alvarez S, Valdez LB, Zaobornyj T, Boveris A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305:771–775. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00818-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]