Abstract

Peroxiredoxins (Prx), a family of peroxidases that reduce intracellular peroxides with the thioredoxin system as the electron donor, are highly expressed in various cellular compartments. Among the antioxidant Prx enzymes, Prx2 is the most abundant in mammalian neurons, making it a prime candidate to defend against oxidative stress. Here we report that Prx2 is S-nitrosylated (forming SNO-Prx2) by reaction with nitric oxide at two critical cysteine residues (C51 and C172), preventing its reaction with peroxides. We observed increased SNO-Prx2 in human Parkinson's disease (PD) brains, and S-nitrosylation of Prx2 inhibited both its enzymatic activity and protective function from oxidative stress. Dopaminergic neurons, which are lost in PD, become particularly vulnerable. Thus, our data provide a direct link between nitrosative/oxidative stress and neurodegenerative disorders such as PD.

Keywords: nitric oxide, nitrosative stress, thioridoxin, sulfiredoxin, peroxides

Peroxiredoxins (Prx) are highly abundant and widely expressed antioxidant enzymes (1–3). In addition to the direct reduction of H2O2 mediated by Prx, the observations that Prx1 interacts with c-Myc (4) and c-Ab1 (5) and that Prx2 regulates PDGF receptor signaling (6) suggest that Prx are important factors linking reactive oxygen species metabolism to redox signaling events. Prx2 levels are significantly increased in neurodegenerative disease (7, 8). Because oxidative stress plays an important role in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders (9, 10), Prx2 up-regulation might counteract oxidative insults during neurodegeneration. Along these lines, Prx have been shown to protect hippocampal neurons from excitotoxic/oxidative injury in vivo (11). Besides regulation of H2O2 signaling by Prx, recent reports also show that oxidative stress shifts Prx from low-molecular-weight species to high-molecular-weight complexes, triggering a peroxidase-to-chaperone functional switch (12) and regulating cell-cycle arrest in C10 mouse lung epithelial cells (13).

Nitric oxide (NO) represents a pleiotropic signaling molecule regulating diverse cellular processes that is produced endogenously from l-arginine by NO synthases. The classical NO signaling pathway is mediated by the generation of cGMP to regulate protein kinase G. However, in the past several years, protein S-nitrosylation, covalent attachment of a −NO group to a cysteine thiol (14–16), has been recognized as a reversible posttranslational modification by which NO regulates the function of many target enzymes, transcription factors, and ion channels, such as Parkin (17, 18), NMDA receptors (19, 20), protein disulfide isomerase (21), NF-κB (22), matrix metalloproteinases (23), and other important proteins (24–29). Oxidative and nitrosative stress are thought to play important roles in neurodegeneration (9, 30–32). However, the pathogenic mechanisms underlying this relationship have not been fully elucidated. Here we report that Prx2 activity is regulated by NO in vitro and in vivo by S-nitrosylation of redox-active cysteine residues in Prx2, forming SNO-Prx2. S-nitrosylation of Prx2 inhibits its protective function against oxidative stress-induced neuronal cell death. This finding provides a mechanistic link between nitrosative/oxidative stress and neurodegenerative disorders.

Results

S-Nitrosylation of Prx2 in Vitro and in Vivo.

Initially, we obtained in vitro evidence that Prx2 was S-nitrosylated by the naturally occurring NO-related species, S-nitrosocysteine (SNOC). After exposure to SNOC, Prx2 in lysates obtained from human SH-SY5Y cells was S-nitrosylated as detected by the biotin-switch method (15, 17, 21). In this assay, SNO-Prx2 was identified on Western blots by replacing the NO group with a more stable biotin group after chemical reduction with ascorbate as described previously (17, 21). SNOC enhanced SNO-Prx2 levels in cell lysates in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A), whereas under the same conditions exposure to hydrogen peroxide did not (data not shown). When we exposed intact SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 1B) to SNOC, we also detected SNO-Prx2. Additionally, we found that SNO-Prx2 was stable even 24 h after SNOC exposure (Fig. 1C). Next, we determined whether endogenous NO could nitrosylate Prx2. For this purpose, HEK-293 cells stably expressing neuronal NO synthase (nNOS) were exposed to calcium ionophore to activate nNOS. In this experiment, we found that endogenous Prx2 could be S-nitrosylated by endogenous NO, and this reaction was inhibited by the NOS inhibitor, N-nitro-l-arginine (NNA) (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

S-nitrosylation of Prx2 in vitro and in vivo. (A) (Upper gel) Cell lysates from human SH-SY5Y cells were incubated in various concentrations of SNOC at room temperature, followed by assay for SNO-Prx2. SNO-Prx2 was detected by biotin-switch assay 30 min after SNOC exposure. (Lower gel) Total Prx2 in cell lysates by Western blot analysis. (B) (Upper gel) Human SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to 200 μM SNOC or control for 30 min, followed by assay for SNO-Prx2. Control samples were subjected to decayed (old) SNOC or SNOC but not to ascorbate. (Lower gel) Total Prx2. (C) Stability of SNO-Prx2 in SH-SY5Y cells. Thirty minutes after incubation in 200 μM SNOC, the medium was replaced and cells were cultured for an additional 8 or 24 h. SNO-Prx2 was detected by the biotin-switch assay. (D) (Upper gel) HEK-293 cells stably expressing nNOS were assayed for endogenous SNO-Prx2. nNOS was activated by the addition of 5 μM Ca2+ ionophore A23187 in the presence or absence of NNA. Activation of nNOS increased endogenous SNO-Prx2, and NNA prevented this increase. (Lower gel) Total Prx2. (E) Primary rat cortical neurons were exposed to 200 μM SNOC, and SNO-Prx2 was detected by the biotin-switch assay. Control samples were subjected to decayed (old) SNOC or SNOC but not to ascorbate. (F) SNO-Prx2 was detected in an NOS-dependent manner in primary mouse cortical cultures exposed to NMDA. Lanes 1–4 are samples from WT neurons and lane 5 from nNOS KO neurons.

Next, we determined whether Prx2 could be S-nitrosylated by NO in primary neuronal cultures. Exposure of primary neurons to SNOC stimulated SNO-Prx2 formation (Fig. 1E). Excitotoxic damage is thought to be critical in neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson's disease (PD) through production of free radicals, including NO, in part by excessive stimulation of NMDA-type glutamate receptors. Therefore, we exposed primary wild-type (WT) or nNOS knockout (KO) neurons to NMDA and found that this procedure induced SNO-Prx2 in an NOS-sensitive fashion (Fig. 1F). These data demonstrate that endogenous Prx2 in neurons is S-nitrosylated by both exogenous and endogenous NO. Moreover, inhibition of SNO-Prx2 formation by NNA or in nNOS KO neurons suggests that a pathophysiologically relevant amount of NO was produced under these conditions.

Prx2 Cys-51 and Cys-172 Are Targets for S-Nitrosylation.

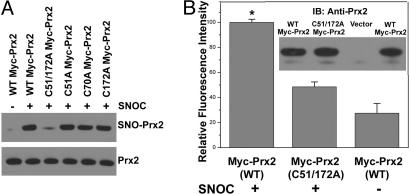

Mammalian Prx2 has three cysteine residues, Cys-51, Cys-70, and Cys-172. Prx1–4 manifest a conserved redox-active site that reduces H2O2 at cysteine residues 51 and 172. To determine the targets of S-nitrosylation on Prx2, we mutated these cysteines and assayed for SNO-Prx2 formation by using the biotin-switch method. HEK-293T cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding WT myc-Prx2 or mutant forms of the protein. Twenty-four hours later, cell lysates were exposed to SNOC or control conditions and monitored for SNO-Prx2. As opposed to single mutations, the C51A/C172A double mutant displayed almost no signal, suggesting that both residues were S-nitrosylated (Fig. 2A). To verify this result, we performed a chemical assay for S-nitrosylation on immunoprecipitates from HEK-293T cells transfected with WT or C51A/C172A double-mutant Prx2. For this purpose, we used the 2,3-diaminonaphthalene (DAN) assay, which monitors the release of the NO group from thiol by conversion of DAN to the fluorescent compound 2,3-naphthyltriazole (17, 21, 33). The fluorescence intensity of double mutant Prx2(C51A/C172A) decreased by ≈80%, compared with WT, indicating that Cys-51 and Cys-172 are the predominant targets for S-nitrosylation on Prx2 (Fig. 2B). As a control, Western blotting indicated that equivalent amounts of protein had been immunoprecipitated by the anti-myc antibody (Fig. 2B Inset).

Fig. 2.

S-nitrosylation of Prx2 Cys-51 and Cys-172. (A) HEK-293T cell lysates transduced with WT or C-to-A mutant myc-Prx2 protein were exposed to 200 μM SNOC or control for 30 min. (Upper gel) SNO-Prx2 was detected by the biotin-switch assay by using anti-myc antibody. (Lower gel) Total protein expression level was determined by Western blotting using anti-myc antibody. Mutation of critical cysteine thiol groups on Prx2 (C51A/C172A) prevented S-nitrosylation by SNOC. (B) HEK-293T cells overexpressing WT or mutant (C51A/C172A) myc-Prx2 were exposed to 200 μM SNOC or control for 30 min, and myc-tagged Prx2 was immunoprecipitated by using an anti-Myc agarose conjugate. Immunocomplexes were subjected to the DAN assay. Fluorescence intensity was normalized to the value obtained for WT Myc-Prx2. *, P < 0.01 (n = 3). (Inset) Immunoblotting was used to ensure equal amounts of Prx2 in the immunocomplex.

S-Nitrosylation of Prx2 Impairs Its Antioxidant Function.

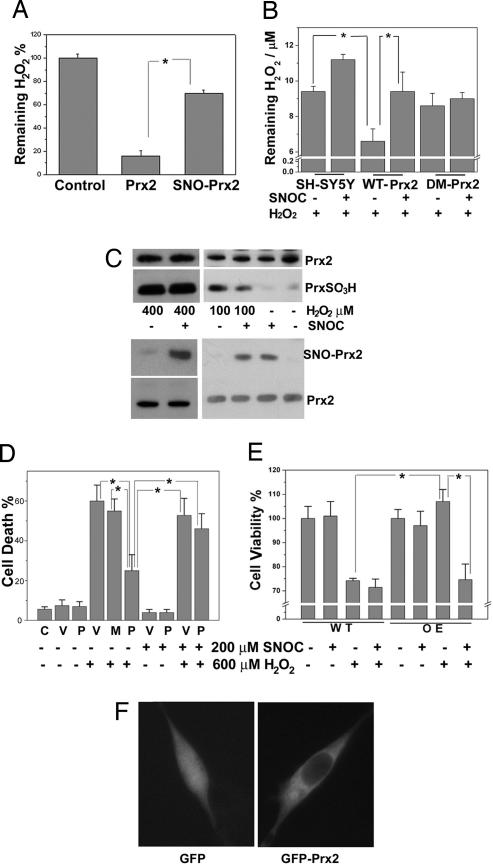

It is well documented that Prx2 has a critical role in the regulation of H2O2 metabolism (34–36). Prx2 reacts with H2O2 (1, 3, 35, 37, 38) with high affinity (Km <10 μM) (39) and a fast reaction rate (K ≈ 4 × 107 M−1·s−1) (35). To determine whether S-nitrosylation of Prx2 affects its reduction of H2O2, we performed an in vitro H2O2-reduction assay comparing WT Prx2 and SNO-Prx2. Exposure of recombinant Prx2 to SNOC dramatically decreased the chemical reduction of H2O2 (Fig. 3A). Consistent with prior reports that the double mutant Prx2(C51A/C172A) lacks catalytic activity (40), we found that this mutant had no effect on hydrogen peroxide levels in the presence or absence of SNOC. Additionally, in intact SH-SY5Y cells, we found that pretreatment with SNOC decreased the reduction of H2O2 by Prx2 (Fig. 3B). Moreover, exposure of SH-SY5Y cells to SNOC resulted in the formation of SNO-Prx2 and inhibited 100 μM H2O2-induced overoxidation of Prx2, as evidenced by less generation of PrxSO2/3H (Fig. 3C Right). This finding suggests that SNO-Prx2 does not reduce H2O2 as efficiently as WT Prx2. Increasing the concentration of H2O2 could overcome this effect probably by promoting further oxidation (23).

Fig. 3.

S-nitrosylation of Prx2 impairs its antioxidant function. (A) Chemical reduction of H2O2 by Prx2 or SNO-Prx2 in vitro. Recombinant Prx2 or SNO-Prx2 (after dissolution of any remaining free NO) was incubated with H2O2 for 20 min at room temperature. The remaining H2O2 level was assayed by using an H2O2 detection kit. *, P < 0.01 (n = 3). (B) SNOC inhibits reduction of H2O2 by Prx2 in SH-SY5Y cells. SH-SY5Y cells or SH-SY5Y cells stably overexpressing WT-Prx2 or double-mutant Prx2(C51A/C172A) (DM-Prx2) were pretreated with 200 μM SNOC before H2O2 challenge. Ten minutes later, the remaining H2O2 level was assayed. *, P < 0.01 (n = 4). (C) S-nitrosylation of Prx2 prevents its overoxidation by 100 μM H2O2. SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to 200 μM SNOC or control for 30 min and then incubated in 100 or 400 μM H2O2 for 10 min. Overoxidized forms of Prx, PrxSO2/3H, were detected by Western blotting using an antibody specific for PrxSO2/3H, and SNO-Prx2 was detected by the biotin-switch assay. (D) S-nitrosylation of Prx2 inhibits its protective function against H2O2-induced cytotoxicity in transiently transfected cells. SH-SY5Y cells were transiently transfected with WT Myc-Prx2 or C51A/C172A mutant Myc-Prx2. Cells were preexposed to SNOC or control for 30 min and then incubated in H2O2 for 24 h. Cell death was assayed by PI and Hoechst staining by counting the ratio of PI-positive (dead) to Hoechst-positive (total) cells. C, control; V, pCMV vector; P, myc-Prx2; M, C51A/C172A myc-Prx2. *, P < 0.05 (n = 4). (E) S-nitrosylation of Prx2 inhibits its protective function against H2O2-induced cytotoxicity in stably transfected cells. WT SH-SY5Y cells (WT) or SH-SY5Y cells stably overexpressing myc-Prx2 (OE) were preexposed to SNOC or control for 30 min and then incubated in H2O2 for 24 h. Cell viability was assayed by fluorescence intensity based on the metabolism of fluorescein diacetate to fluorescein in living cells. *, P < 0.05 (n = 4). (F) Overexpression of Prx2 does not affect its intracellular localization. SH-SY5Y cells were transiently transfected with GFP or GFP-Prx2. Prx2 distribution was monitored by deconvolution microscopy 24 h later.

To demonstrate the relevance of these findings to neurodegenerative disease models, we transiently transfected WT myc-Prx2 (P) or C51A/C172A double-mutant myc-Prx2 (M) into SH-SY5Y cells and evaluated their protective effects after H2O2 challenge in the presence or absence of NO. For this purpose, we used the dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cells because, unlike nigrostriatal or cerebrocortical neurons, they are resistant to direct NO-induced damage under conditions of SNO-Prx2 formation, allowing us to tease apart the effect of NO and Prx2 S-nitrosylation on cell death. WT Prx2 protected against H2O2-induced cell death, whereas the double-mutant Prx2 did not (Fig. 3D). However, after SNOC pretreatment, the protective effect of WT Prx2 against H2O2 significantly decreased. One concern with this kind of transient transfection experiment is the potentially variable level of construct expression among cells. To overcome this concern, we generated stable transformants of SH-SY5Y cells overexpressing WT myc-Prx2 and again found that SNOC pretreatment significantly inhibited the protective function of Prx2 against oxidative stress-induced cell death (Fig. 3E). Importantly, Prx2 overexpression did not affect the known intracellular localization of the endogenous protein in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3F). Moreover, these overexpression models have pathophysiological relevance because Prx2 levels also increase in human PD brains, compared with normal controls (Fig. 4D, lanes 1 and 2 vs. lanes 6 and 7; lanes 8 and 9 vs. lanes 10, 11, and 12).

Fig. 4.

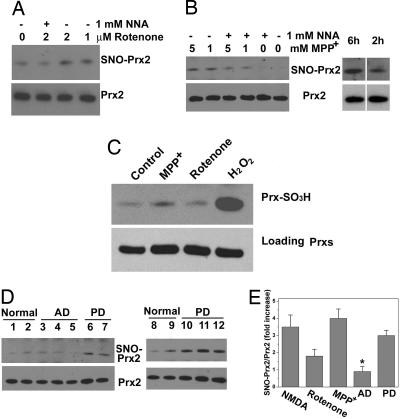

Increased levels of S-nitrosylated Prx2 in PD models and in brain tissues from PD patients. (A) Rotenone increased SNO-Prx2 levels in SH-SY5Y cells in an NOS-dependent manner. SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to rotenone for 4.5 h in the presence or absence of the NOS inhibitor NNA, and SNO-Prx2 was detected by the biotin-switch assay. (B) MPP+ increased SNO-Prx2 levels in SH-SY5Y cells in an NOS-dependent manner. (Left) SNO-Prx2 was detected by using the biotin-switch assay 6 h after MPP+ exposure. (Right) SNO-Prx2 accumulation was time-dependent after exposure to 1 mM MPP+. (C) Overoxidized Prx levels induced by 2 μM rotenone for 4.5 h or 1 mM MPP+ for 2 h in SH-SY5Y cells. Then 100 μM H2O2 for 10 min was used as a positive control. (D) Brain tissues from controls, AD patients, or PD patients were subjected to the biotin-switch assay to detect SNO-Prx2 in vivo. Equal amounts of total protein were loaded, and Prx2 in patient samples was detected by immunoblotting. (E) Ratio of increased SNO-Prx2 formation in PD models and in human brains. NMDA, NMDA-stimulated primary neurons; rotenone, 2 μM rotenone-exposed SH-SY5Y cells; MPP+, 5 mM MPP+-exposed SH-SY5Y cells for 6 h; AD, brain tissues from AD patient; PD, brain tissues from PD patient. Blots from the biotin-switch assay and Western blot analyses were quantified by densitometry, and the relative ratio of SNO-Prx2 to total Prx2 was calculated. *, P < 0.05 (n = 3–5).

SNO-Prx2 in PD Cell-Based Models and Human PD Brains.

The fact that nitrosative stress is thought to contribute to a number of neurodegenerative disorders such as PD (17, 18, 21, 41) prompted us to ask whether SNO-Prx2 could be detected in cell-based models of PD and human PD brains. First, we incubated dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cells with the mitochondrial complex I inhibitor rotenone or 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium iodide (MPP+), each of which injures or kills neurons and induces a Parkinsonian phenotype at least, in part, in an NO-dependent fashion (21). Exposure to rotenone or MPP+ led to the generation of SNO-Prx2 in these cells, but this effect was completely prevented (for rotenone) or partially inhibited (after MMP+) by the NOS inhibitor, NNA (Fig. 4 A and B). We found only low levels of overoxidized Prx (PrxSO2/3H) under the conditions assayed for SNO-Prx2, but much higher levels after exposure to H2O2 (Fig. 4C). To extend these findings to humans, we examined brains of patients manifesting PD with Lewy bodies obtained shortly after death (21). We found evidence for significantly increased SNO-Prx2 levels in all five PD brains examined, but not in Alzheimer's disease (AD) or control brains obtained from patients who had died of disorders not of CNS origin (Fig. 4 D and E). To determine whether the level of SNO-Prx2 in PD human brain is of pathophysiological significance, we calculated the ratio of SNO-Prx2 (by biotin-switch assay) to total Prx2 (from Western blotting) and found that this ratio was comparable to that encountered in our neuronal cell models manifesting cell death (Fig. 4E). This finding indicates that pathophysiologically relevant amounts of SNO-Prx2 are present in human brains with PD.

Discussion

Prx family proteins are important antioxidant enzymes that limit accumulation of intracellular peroxides by redox reactions at certain key cysteine residues. Prx2 is extremely abundant in the brain (42). Our data demonstrate a previously unrecognized relationship between NO and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disorders, showing that Prx2 is S-nitrosylated in vitro, in cell-based models of PD, and in human PD brain tissue. S-nitrosylation targets the redox-active Cys-51 and Cys-172 residues, which are both critical for Prx2 activity (40), thus inhibiting its neuroprotective function against oxidative stress. SNO-Prx2 formation, resulting in Prx2 dysfunction, therefore provides a mechanistic link between nitrosative/oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. Because the cysteine motifs are conserved in all Prx containing dual-thiol-active sites (Prx1–4), we hypothesize that each of them may be a target of S-nitrosylation, and that NO therefore regulates metabolism of intracellular peroxides through S-nitrosylation of these active sites.

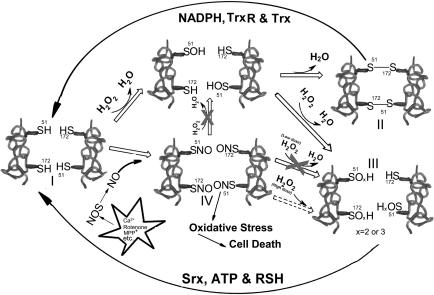

Active Prx2 reduces H2O2 and other peroxides to form a sulfenic acid (−SOH; Fig. 5, I). In turn, this adduct can either be reduced by another active Prx2 to form an intermolecular disulfide bond (S–S; Fig. 5, II) or overoxidized to produce sulfinic (−SO2H) or sulfonic acid (−SO3H; Fig. 5, III). Both the disulfide and overoxidized forms can be regenerated to their active states by coordinated action of the thioredoxin pathway (thioredoxin reductase, thioredoxin, and NADPH) and the sulfiredoxin pathway (1, 2, 43). By using this normal redox cycle, Prx2 detoxifies intracellular peroxides. In the present study, however, we found that SNO-Prx2, produced after nitrosative stress, cannot reduce peroxides (Fig. 5, IV). Thus, S-nitrosylation of Prx2, generating nonfunctional Prx2, interrupts the normal redox cycle and results in accumulation of cellular peroxides, inducing oxidative stress. Higher concentrations of peroxides, however, can probably further oxidize SNO-Prx2 to Prx2-SO2/3H (dashed line in Fig. 5) (23). PD results primarily from the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra; these neurons are particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress, in part, because of the oxidizing nature of dopamine. Interfering with the normal antioxidant system by the generation of SNO-Prx2 may contribute to neuronal cell death. Evidence for increased SNO-Prx2 formation in cell-based models of PD and human PD brain tissue strongly supports this mechanism. Our elucidation of an NO-mediated pathway leading to neuronal cell death involving Prx2 dysfunction may lead to the development of new therapeutic approaches for sporadic PD and other neurodegenerative disorders associated with nitrosative/oxidative stress.

Fig. 5.

Reaction mechanism of SNO-Prx2 contribution to oxidative stress and neuronal cell death in human neurodegenerative disorders. TrxR, thioredoxin reductase; Trx, thioredoxin; Srx, sulfiredoxin.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Antibodies.

Hepes, ascorbate, S-nitrosoglutathione, hydrogen peroxide, methyl methane thiosulfonate, NNA, propidium iodide (PI), rotenone, MPP+, mercury chloride, and DAN were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Biotin-HPDP and immobilized avidin were from Pierce Chemical (Rockford, IL). Anti-Prx2 and anti-PrxSO2/3H were obtained from Lab Frontier (Seoul, Korea). Anti-myc-agarose beads were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Fluorescein diacetate and Hoechst 33342 were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Primers for site-directed mutagenesis were from Sigma–Genosys (The Woodlands, TX). All reagents were of analytical grade.

Biotin-Switch Assay for Detection of SNO-Prx2.

Primary cortical cultures were prepared as described (21), exposed to 200 μM NMDA (plus 5 μM glycine) for 40 min in nominally Mg2+-free Earle's balanced salt solution with 1.8 mM CaCl2 supplemented with 0.4 mM l-arginine, and then replaced in the original conditioned medium for an additional 4.5 h. Cell lysates and brain tissue extracts were prepared in HENTS buffer [250 mM Hepes (pH 7.7), 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM neocuproine, 0.1% SDS, and 1% Triton X-100). By protein assay, cell lysates typically contained 500-μg and 1.7-mg tissue samples. Blocking buffer (2.5% SDS and 20 mM methyl methane thiosulfonate) in HEN buffer [250 mM Hepes (pH 7.7), 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 mM neocuproine] was mixed with samples and incubated for 30 min at 50°C to block free thiol groups. After removing excess methyl methane thiosulfonate by acetone precipitation, nitrosothiols were reduced to thiols with 1 mM ascorbate. Newly formed thiols were then linked with the sulfhydryl-specific biotinylating reagent N-[6-biotinamido]-hexyl]-l′-(2′pyridyldithio) propionamide. Biotinylated proteins were pulled down with Streptavidin-agarose beads, and immunoblot analysis detected the amount of total Prx2. SNO-Prx2 was detected by the biotin-switch assay (15, 17, 21).

Fluorometric Detection of SNO-Prx2.

S-nitrosothiol formation was detected by conversion of DAN to the fluorescent compound 2,3-naphthyltriazole with an emission wavelength of 450 nm and an excitation wavelength of 375 nm by using a fluorometric plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) (17, 21, 33). Conversion to S-nitrosothiol was linear over the 0.05–20 μM range as assayed by using S-nitrosoglutathione as a positive control (data not shown). For the DAN assay, either recombinant Prx2 was assayed or Prx2 purified from cells. For this purpose, HEK-293T cells were transfected with myc-Prx2 or C51A/C172A myc-Prx2. Thirty-six hours later, cells were incubated with or without 200 μM SNOC for 30 min. SNO-Prx2 was immunoprecipitated with anti-myc-agarose beads in the dark, and the immunocomplex was washed three times with HENTS buffer and twice with PBS. After resuspension of the immunocomplex in 150 μl of PBS, 200 μM HgCl2 and 200 μM DAN were added to the solution and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The fluorescence intensity of the supernatant was measured by using the fluorometric plate reader.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis of Prx2.

Mutant Prx2 plasmids were constructed by using the myc-Prx2 plasmid as a template. The following sets of forward and reverse primers were used to introduce mutations at Cys-51, Cys-70, and Cys-172: C51A, CTGGACTTCACTTTTGTGGCCCCCACCGAGATC (forward) and GATCTCGGTGGGGGCCACAAAAGTGAAGTCCAG (reverse); C70A, TTCCGGAAGCGCTGAAGTGCTGGGCGTC (forward) and GACGCCCAGCACTTCAGCGCCCAGCTTGCGGAA (reverse); and C172A, GAGCATGGGGAAGTTGCTCCCGCTGGCTGGAAG (forward) and CTTCCAGCCAGCGGGAGCAACTTCCCCATGCTC (reverse). The double-mutant C51A/C172A plasmid was constructed by using the C172A myc-Prx2 plasmid as a template. All mutant plasmids were constructed by using the QuikChange II kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Mutagenesis was confirmed by automated nucleotide sequencing.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Prx2.

WT Prx2 cDNA was cloned into a pGEX-4T-2 vector and expressed in BL21 cells according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). GST-fused Prx2 was purified on a column of glutathione Sepharose beads (MicroSpin GST Purification Module), and fusion proteins were treated with thrombin to remove GST.

Reduction of H2O2 by Prx2.

Recombinant Prx2 was exposed to 200 μM SNOC for 30 min at room temperature. After desalting by using a Bio-Spin 6 column, Prx2 or SNO-Prx2 was incubated with 50 μM H2O2 for 20 min at room temperature. The H2O2 concentration in the reaction mixture was then measured with a hydrogen peroxide assay kit (A22188; Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For cell-based models, SH-SY5Y cells or SH-SY5Y cells stably expressing WT-Prx2 or double-mutant Prx2(C51A/C172A) were pretreated with 200 μM SNOC for 30 min. After removing the medium and washing the cells once with PBS, the cells were further treated with 50 μM H2O2 for 10 min. The H2O2 level remaining in the media was then determined with a hydrogen peroxide assay kit.

Cell Death and Viability Assays.

SH-SY5Y cells were transiently transfected by using Lipofectamine 2000 (with ≈40% transfection efficiency as judged by GFP labeling). Twenty-four hours later, cells were exposed to 200 μM SNOC. Thirty minutes later, medium with or without 600 μM H2O2 replaced the old medium. Cells were cultured for an additional 24 h and then stained with PI to assess death and with Hoechst 33342 for total cell count (44). SH-SY5Y cells stably overexpressing Myc-Prx2 also were compared in viability assays with WT SH-SY5Y cells. Cells were exposed to 200 μM SNOC; 30 min later, fresh medium with or without 600 μM H2O2 replaced the old medium. Cells were cultured for another 24 h and incubated with fluorescein diacetate, which is taken up and cleaved to fluorescein in viable cells. Fluorescence intensity was measured at an emission wavelength of 510 nm and an excitation wavelength of 493 nm (45–47).

Cell-Based Models of PD and Human PD Brains.

SH-SY5Y cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% FCS in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After cells were incubated with rotenone (4.5 h) or MPP+ (2 or 6 h), SNO-Prx2 was detected by using the biotin-switch method. To inhibit NOS activity, 1 mM NNA was added to the medium 1 h before rotenone or MPP+ exposure. Human brain samples were analyzed with institutional permission under California and National Institutes of Health guidelines (21). Informed consent was obtained following the procedures of the Institutional Review Boards of the University of California at San Diego and the Burnham Institute for Medical Research.

Statistics.

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA, followed by a post hoc Scheffé test. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Acknowledgments

We thank Traci Hong Fang for preparation of primary cultures and Dr. Eliezer Masliah (University of California at San Diego) for kindly providing human brain tissues. This work was supported in part by a Japan Society for Promotion of Science Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research Abroad (to T.N.); National Institutes of Health Grants P01 HD29587, R01 EY09024, R01 EY05477, and R01 NS41207; the American Parkinson's Disease Association; an Ellison Medical Foundation Senior Scholar Award in Aging Research (to S.A.L.); and National Institutes of Health Blueprint Grant for La Jolla Interdisciplinary Neuroscience Center Cores P30 NS057096.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- DAN

2,3-diaminonaphthalene

- KO

knockout

- MPP+

1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium iodide

- NNA

N-nitro-l-arginine

- nNOS

neuronal NO synthase

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- PI

propidium iodide

- Prx2

peroxiredoxin 2

- SNOC

S-nitrosocysteine

- SNO-Prx2

S-nitrosylated Prx2.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Rhee SG, Kang SW, Jeong W, Chang TS, Yang KS, Woo HA. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rhee SG, Chae HZ, Kim K. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:1543–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood ZA, Schroder E, Robin Harris J, Poole LB. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:32–40. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egler RA, Fernandes E, Rothermund K, Sereika S, de Souza-Pinto N, Jaruga P, Dizdaroglu M, Prochownik EV. Oncogene. 2005;24:8038–8050. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wen ST, Van Etten RA. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2456–2467. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.19.2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi MH, Lee IK, Kim GW, Kim BU, Han YH, Yu DY, Park HS, Kim KY, Lee JS, Choi C, et al. Nature. 2005;435:347–353. doi: 10.1038/nature03587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SH, Fountoulakis M, Cairns N, Lubec G. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2001:223–235. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6262-0_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krapfenbauer K, Engidawork E, Cairns N, Fountoulakis M, Lubec G. Brain Res. 2003;967:152–160. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin MT, Beal MF. Nature. 2006;443:787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dauer W, Przedborski S. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hattori F, Murayama N, Noshita T, Oikawa S. J Neurochem. 2003;86:860–868. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jang HH, Lee KO, Chi YH, Jung BG, Park SK, Park JH, Lee JR, Lee SS, Moon JC, Yun JW, et al. Cell. 2004;117:625–635. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phalen TJ, Weirather K, Deming PB, Anathy V, Howe AK, van der Vliet A, Jonsson TJ, Poole LB, Heintz NH. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:779–789. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hess DT, Matsumoto A, Kim SO, Marshall HE, Stamler JS. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:150–166. doi: 10.1038/nrm1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaffrey SR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Ferris CD, Tempst P, Snyder SH. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:193–197. doi: 10.1038/35055104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hess DT, Matsumoto A, Nudelman R, Stamler JS. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:E46–E49. doi: 10.1038/35055152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao D, Gu Z, Nakamura T, Shi ZQ, Ma Y, Gaston B, Palmer LA, Rockenstein EM, Zhang Z, Masliah E, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10810–10814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404161101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung KK, Thomas B, Li X, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Marsh L, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Science. 2004;304:1328–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.1093891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi YB, Tenneti L, Le DA, Ortiz J, Bai G, Chen HS, Lipton SA. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:15–21. doi: 10.1038/71090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi H, Shin Y, Cho SJ, Zago WM, Nakamura T, Gu Z, Ma Y, Furukawa H, Liddington R, Zhang D, et al. Neuron. 2007;53:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uehara T, Nakamura T, Yao D, Shi ZQ, Gu Z, Ma Y, Masliah E, Nomura Y, Lipton SA. Nature. 2006;441:513–517. doi: 10.1038/nature04782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall HE, Hess DT, Stamler JS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8841–8842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403034101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu Z, Kaul M, Yan B, Kridel SJ, Cui J, Strongin A, Smith JW, Liddington RC, Lipton SA. Science. 2002;297:1186–1190. doi: 10.1126/science.1073634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshida T, Inoue R, Morii T, Takahashi N, Yamamoto S, Hara Y, Tominaga M, Shimizu S, Sato Y, Mori Y. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:596–607. doi: 10.1038/nchembio821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang G, Moniri NH, Ozawa K, Stamler JS, Daaka Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1295–1300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508354103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Y, Loscalzo J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:117–122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405989102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell DA, Marletta MA. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:154–158. doi: 10.1038/nchembio720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hara MR, Agrawal N, Kim SF, Cascio MB, Fujimuro M, Ozeki Y, Takahashi M, Cheah JH, Tankou SK, Hester LD, et al. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:665–674. doi: 10.1038/ncb1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipton SA, Choi YB, Pan ZH, Lei SZ, Chen HS, Sucher NJ, Loscalzo J, Singel DJ, Stamler JS. Nature. 1993;364:626–632. doi: 10.1038/364626a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang D, Qian L, Xiong H, Liu J, Neckameyer WS, Oldham S, Xia K, Wang J, Bodmer R, Zhang Z. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13520–13525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604661103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giasson BI, Duda JE, Murray IV, Chen Q, Souza JM, Hurtig HI, Ischiropoulos H, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Science. 2000;290:985–989. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5493.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coyle JT, Puttfarcken P. Science. 1993;262:689–695. doi: 10.1126/science.7901908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wink DA, Kim S, Coffin D, Cook JC, Vodovotz Y, Chistodoulou D., Jourd'heuil D, Grisham MB. Methods Enzymol. 1999;301:201–211. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)01083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang CS, Lee DS, Song CH, An SJ, Li S, Kim JM, Kim CS, Yoo DG, Jeon BH, Yang HY, et al. J Exp Med. 2007;204:583–594. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Low FM, Hampton MB, Peskin AV, Winterbourn CC. Blood. 2007;109:2611–2617. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-048728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim H, Lee TH, Park ES, Suh JM, Park SJ, Chung HK, Kwon OY, Kim YK, Ro HK, Shong M. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18266–18270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.24.18266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood ZA, Poole LB, Karplus PA. Science. 2003;300:650–653. doi: 10.1126/science.1080405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woo HA, Chae HZ, Hwang SC, Yang KS, Kang SW, Kim K, Rhee SG. Science. 2003;300:653–656. doi: 10.1126/science.1080273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chae HZ, Kim HJ, Kang SW, Rhee SG. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1999;45:101–112. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(99)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chae HZ, Chung SJ, Rhee SG. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27670–27678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung KK, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-Grand) 2005;51:247–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore RB, Mankad MV, Shriver SK, Mankad VN, Plishker GA. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18964–18968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Biteau B, Labarre J, Toledano MB. Nature. 2003;425:980–984. doi: 10.1038/nature02075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andrabi SA, Kim NS, Yu SW, Wang H, Koh DW, Sasaki M, Klaus JA, Otsuka T, Zhang Z, Koehler RC, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18308–18313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606526103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jackson PR, Pappas MG, Hansen BD. Science. 1985;227:435–438. doi: 10.1126/science.2578226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schanne FA, Kane AB, Young EE, Farber JL. Science. 1979;206:700–702. doi: 10.1126/science.386513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amano T, Hirasawa K, O'Donohue MJ, Pernolle JC, Shioi Y. Anal Biochem. 2003;314:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00653-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]