Abstract

Here, we show how targeting protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), a key regulator of cellular protein phosphorylation, can either induce or prevent apoptosis depending on what other signals the cell is receiving. The oncoprotein polyoma small T interacts with PP2A to regulate survival. In the presence of growth factors, small T induces apoptosis. Akt activity, which usually promotes survival, is required for this death response, because inhibitors of Akt or PI3 kinase protect cells from death. The activation of Akt under these conditions is partial, characterized by T308 phosphorylation but not S473 phosphorylation. In the absence of growth factors, small T protects from cell death. Here, small T uses PP2A to promote phosphorylation of Akt on both T308 and S473. This effect results in a different pattern of phosphorylation of Akt substrates and shifts Akt from a proapoptotic (presence of growth factors) to an antiapoptotic mode (absence of growth factors). An intriguing possibility is that Akt phosphorylation could be therapeutically disregulated to decrease the survival of cancer cells.

Keywords: apoptosis, cancer, DNA tumor virus

The kinase Akt, a downstream target of PI3 kinase (1), is well known to be involved in transformation and cell survival. Akt inactivates cellular pro-apoptotic proteins such as GSK3, FOXO1/3a, BAD, and caspase 9. It affects prosurvival proteins as well. For example, it induces expression of the Bcl2 family of proteins, stabilizes Xiap, and activates IKK (2, 3). Akt has other critical functions as well. It regulates proteins important for cell cycle progression, carbohydrate metabolism, and the control of translation. The activation of Akt occurs when phosphoinositides produced by PI3 kinase direct the relocalization of the enzyme and its activation by phosphorylation on residues T308 and S473. Both phosphorylations are thought to be required for full activation of the enzyme. Whereas the phosphatase PHLPP has recently been proposed to dephosphorylate S473 (4, 5), protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is known to dephosphorylate T308 (6).

In addition to its many other functions, PP2A, a major cellular serine/threonine phosphatase (7, 8), has been shown to regulate cell survival (9–11). The enzyme consists of a catalytic subunit C and two additional subunits: A, which functions as a scaffold, and B, which has many family members and confers specificity. Polyoma virus small T antigens affect cellular transformation, cell cycle regulation, gene transcription, and apoptosis. For example, SV40 small T was shown to be part of the formula for the transformation of human mammary epithelial cells (12, 13). The functions of small Ts have largely been attributed to their ability to bind PP2A. Polyomavirus small Ts target PP2A by replacing PP2A B subunits. Small Ts of polyoma and SV40 are also known to either promote or prevent cell death (14, 15).

A continuing lesson is the importance of context to cell signaling. This work shows how Akt can be switched between anti- and proapoptotic functions depending on the presence of growth factors in the medium. The mechanism depends on the regulation of protein phosphatase 2A activity to control the phosphorylation status of Akt. In turn, this modulates the pattern of phosphorylation of Akt substrates.

Results

Polyoma Small T Induced Apoptosis in the Presence of Growth Factors.

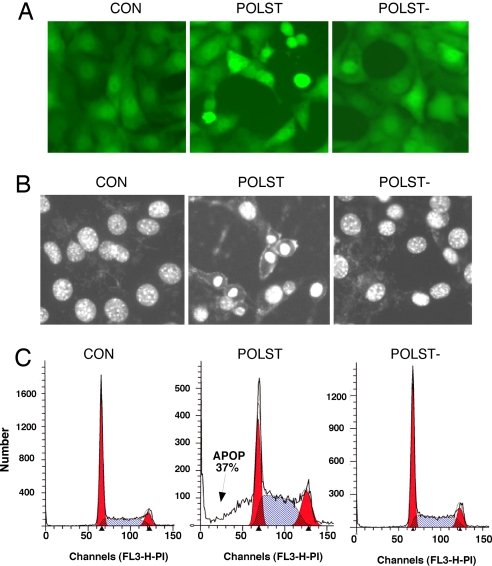

To study how small T antigens could affect host cell survival, we obtained cells expressing either wild-type polyoma small T antigen or a mutant that does not bind PP2A (PP2A−). A retroviral construct (Pinco retroviral vector) (16) that allows the expression of small Ts and GFP from independent promoters was used for this purpose. Within a few days of small T expression, mouse fibroblasts looked rounded, whereas controls or cells expressing polyoma small T defective for PP2A binding did not (Fig. 1A). Hoechst staining showed a large number of nuclei with condensed morphology when wild-type small T was expressed (Fig. 1B). FACS analysis indicated that wild-type small T cells were undergoing apoptosis as evidenced by a sub G1 peak (Fig. 1C) as well as by DNA laddering [supporting information (SI) Fig. 6A]. All these effects depended on PP2A binding, because a mutant that failed to bind PP2A (POLST−) had little or no effect (Fig. 1 A–C). These results were a first indication that polyoma small T is capable of inducing apoptosis in host cells. Not surprisingly, the number of GFP-positive cells, the intensity of GFP expression (data not shown), and the expression of small T all decreased with passage number (SI Fig. 7B).

Fig. 1.

Polyoma small T is proapoptotic in presence of serum: NIH 3T3 cells were infected with retrovirus expressing GFP only (CON), expressing GFP and wild-type small T (POLST), or GFP and mutant small T defective in PP2A binding (POLST−). (A) Morphology of cells growing in 10% calf serum seen by fluorescence microscopy (×20 magnification). (B) Nuclear morphology seen by Hoechst 33342 staining and fluorescence microscopy (×20 magnification). (C) FACS analysis of cells growing in 10% calf serum stained with propidium iodide. Cells with subG1 DNA content (37% of the population) are indicated by the arrow.

This effect could also be seen in other cell types. We transfected small T together with GFP into the human osteosarcoma cell line, U2OS. Both cellular and nuclear morphology confirmed that these cells developed apoptotic features in a PP2A-dependent manner as was seen in stably expressing cells (SI Fig. 6 B and C).

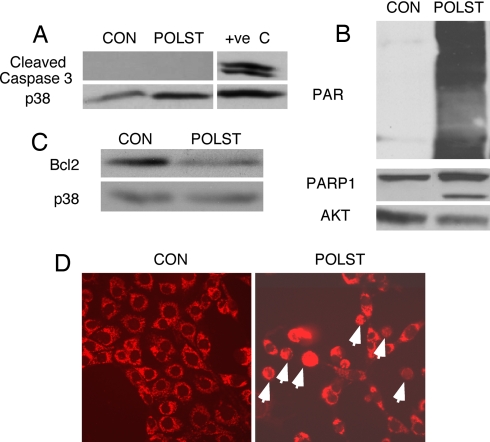

Small T Induced Apoptosis by a Caspase-Independent Mechanism.

Apoptosis commonly features caspase activation, with caspase 3 as a central component. Blotting did not show any evidence that caspase-3 was activated in polyoma small T-mediated apoptosis (Fig. 2A), suggesting that it may be mediated by caspase-independent pathways. Another characteristic of apoptosis is the activation and cleavage of PARP-1 (Poly ADP Ribosyl polymerase-1). PARP-1 can be activated by caspase-independent mechanisms in response to DNA damage (17, 18). Activated PARP-1 adds polymers of ADP-Ribose onto a number of cellular proteins that are involved in transcription, DNA repair, chromatin modifications, and apoptosis (19, 20). Polyoma small T-expressing cells showed robust activation of PARP-1 as seen by its cleavage and ADP-ribosylation of cellular proteins (Fig. 2B). DPQ, an inhibitor of PARP-1, reduced ADP ribosylation and the amount of DNA laddering produced by small T (SI Fig. 8 A and B), thus suggesting that apoptosis was mediated by PARP-1. Consistent with the induction of apoptosis, we also saw that small T-expressing cells had lower levels of Bcl2 protein, suggesting that the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane was compromised (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of apoptosis induced by small T. (A) Blotting of cleaved caspase 3 in control or small T-expressing cells growing in 10% calf serum. Extract from NIH 3T3 cells serum-starved overnight was used as a positive control (+ve C). Total p38 was used as a loading control. (B) Blotting of cell extracts with antibody against Poly ADP Ribose (PAR) or PARP-1. Total Akt was used as a loading control. (C) Blotting of cell extracts with antibody against Bcl2. Total p38 was used as loading control. (D) Translocation of apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) from mitochondria to the nucleus in polyoma small T-expressing, but not control cells, detected by immunofluorescence stained with Trit-C by using antibody against AIF.

Activation of PARP-1 is accompanied by translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) from mitochondria to the nucleus, where it initiates DNA fragmentation together with other endonucleases, including endonuclease G (21). AIF translocation was enhanced by 3- to 4-fold in small T-expressing cells that were undergoing cell death (Fig. 2D and SI Fig. 6D), although there was no difference in the level of expression of AIF between the control and small T-expressing cells (SI Fig. 6E).

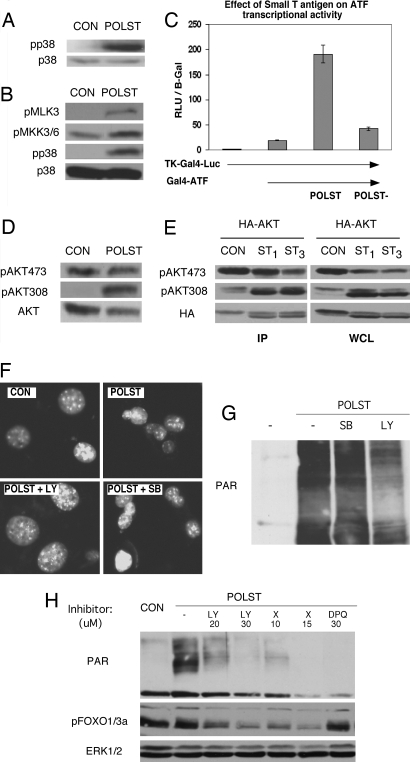

Small T Regulates both the p38 and the PI3K/Akt Pathways.

What mechanisms are involved in regulating cell survival? p38 is activated in response to stress (22, 23) and can induce apoptosis. Blotting for phospho-p38 indicated a substantial increase in phosphorylation in small T-expressing cells (Fig. 3A). In addition, both upstream elements (MKK3/6 and MLK3) (Fig. 3B) as well as downstream targets such as ATF2 (Fig. 3C) and MAPKAP-K2 (SI Fig. 8C) were activated. All these results again depended on the interaction of small T with PP2A. As was seen for small T expression, activation of p38 was lost upon passaging (SI Fig. 7A).

Fig. 3.

Small T regulation of cell signaling in growing conditions. NIH 3T3 cells infected with retrovirus expressing GFP only (CON) or expressing GFP and wild-type small T (POLST) were grown in 10% calf serum. (A) Cell extracts were blotted with antibody specific for phospho p38 (pp38) or total p38 (p38). (B) Cell extracts of control or small T-expressing cells were blotted with anti-phospho MLK3 or MKK3/6. Phospho p38 and p38 blots are shown as controls. (C) Effect of small T on the activity of ATF2, a downstream target of p38. ATF2 activity was measured in a reporter assay by cotransfection of TKGal4 luciferase, GAL4-ATF2 with wild-type small T (POLST), PP2A− small T (POLST−), or empty vector as shown. (D) Cell extracts were blotted with antibody specific for phosphorylation of T308 or phosphorylation of S473 to assess activation of Akt. Anti-Akt was used to determine the amount of protein. (E) Cells (293T) were transfected with HA-Akt and control (CON), 1 μg (ST1), or 3 μg (ST3) of small T plasmid. Extracts (Right) or HA-Akt immunoprecipitates (Left) were made 48 h after transfection. Blotting with antibody specific for phosphorylation of T308 or phosphorylation of S473 on Akt was used to assess activation, and total transfected HA-Akt was determined by using HA11. (F) Nuclear morphology seen by Hoechst 33342 staining and fluorescence microscopy (×20 magnification) in untreated cells or in cells treated with PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 (24 h, 20 μM) or with p38 inhibitor SB203580 (24 h, 20 μM). (G) Small T-expressing cells growing in 10% serum were treated with PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 (20–24 h, 20 μM) or p38 inhibitor SB203580 (20–24 h, 20 μM). Extracts from control and treated cells were blotted with PAR antibody. (H) Small T-expressing cells growing in 10% serum were treated with specific Akt inhibitor AktX (10 μM and 15 μM), PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 (20 μM and 30 μM), or PARP-1 inhibitor DPQ (30 μM) for 16–20 h. Extracts from control and treated cells were blotted with PAR antibody. The inhibition of Akt activity was indicated by blotting with phosphospecific FOXO1/3a antibody, and ERK1/2 served as a loading control.

Because PI3 kinase signaling to Akt has a central role in cell survival, we checked for Akt activation. Phosphorylation of Akt at T308 was dramatically stimulated in small T-expressing cells, but phosphorylation at S473 was not affected (Fig. 3D). Small T had a similar effect on T308 of Akt1 in cotransfections in 293T cells, but S473 phosphorylation showed a significant decrease in HA-Akt immunoprecipitates (Fig. 3E). These effects of small T were again PP2A-dependent because the mutant polyoma small T did not have any effect on Akt phosphorylation (data not shown). Similar effects of small T were also seen on Akt2 (data not shown).

Inhibitor Experiments Demonstrate the Importance of Akt.

To distinguish the relative contributions of the PI3 kinase and p38 pathways, inhibitor experiments were performed. Inhibition of p38 with SB203580 had no effect on survival as assessed by Hoechst staining or levels of ADP ribosylation (Fig. 3 F and G), even though it blocked phosphorylation of the p38 substrate MAPKAP-K2 (SI Fig. 8C). On the other hand, the PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 reduced nuclear condensation as measured by Hoechst staining (Fig. 3F), polyADP ribosylation seen by blotting with PAR antibody (Fig. 3G), and DNA laddering (SI Fig. 8B). The extent of the LY effect depends on when LY is added with respect to small T expression. Earlier addition (as in Fig. 3H) before any morphologic effects could be seen was more effective in blocking induction. AktX, a specific inhibitor of Akt kinase activity (24), reduced phosphorylation of FOXO1/3a at Akt sites and also reduced ADP ribosylation (Fig. 3H). This confirmed a role for Akt in small T-induced cell death. These results contrast sharply with the usual role of PI3 kinase/Akt signaling in promoting cell survival.

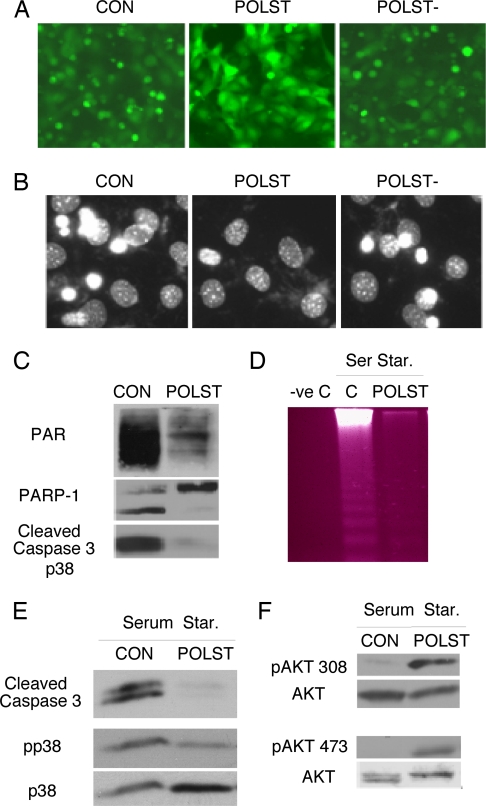

Small T Resisted Caspase-Dependent Apoptosis Induced by Serum Starvation.

Comparison of the effects of small T under different conditions emphasized the importance of context for survival signaling. Serum-starved 3T3 cells undergo caspase-dependent cell death (25) that also involves PARP-1 activation. Control or small T-expressing cells were cultured in medium lacking serum for 16–24 h. When cells expressed small T, they were protected from apoptosis as seen by cellular morphology (Fig. 4A) and Hoechst staining of the nuclei (Fig. 4B and SI Fig. 9A), reduced polyADP ribosylation, lack of PARP-1 and caspase 3 activation (Fig. 4C), and reduced DNA laddering (Fig. 4D). Once again, a small T mutant lacking the ability to bind PP2A failed to protect cells from starvation-induced death. This indicates that PP2A is the essential regulator of cell survival in these circumstances. Inhibition of the Akt pathway by addition of LY294002 (SI Fig. 9B) enhanced serum starvation-induced cell death in 3T3s as shown by enhanced PARP cleavage (SI Fig. 9B). Taken together, the data suggest that Akt is functioning in its traditional role to promote cell survival in this context.

Fig. 4.

Polyoma small T is prosurvival under serum-starvation conditions. (A) Morphology of control, wild type or PP2A− mutant small T-expressing cells growing in the absence of serum overnight (16–24 h) as seen by fluorescence microscopy for GFP (×10 magnification). (B) Nuclear morphology seen by Hoechst 33342 staining and fluorescence microscopy (×20 magnification) of cells treated as in A. (C) Control and small T-expressing cells were serum starved overnight. Cells were protected from death by small T as shown by blotting of cell extracts for PAR, PARP-1, and caspase 3 activation. (D) Polyoma small T suppressed DNA laddering caused by serum starvation. DNA was extracted from cells growing in 10% serum (-ve C) or starved overnight (control or small T). Equal amounts of DNA were loaded on a 2% gel and stained with ethidium bromide. (E) Cell extracts from control or small T-expressing cells starved overnight were blotted with antibody specific for caspase 3, phospho p38 (pp38), or total p38 (p38). (F) Cell extracts from control or small T-expressing cells starved overnight were blotted with anti-p308 Akt antibody (Upper) and anti-pS473 Akt antibody (Lower). Anti-Akt was used to determine the amount of Akt protein.

The pattern of signaling changes seen when serum was withdrawn was studied next. Although small T induced p38 phosphorylation in growing cells, it reduced p38 phosphorylation in starved cells (Fig. 4E). In contrast to growing conditions, small T induced phosphorylation at both S473 and T308 on Akt (Fig. 4F). One simple interpretation of this result is that, in the absence of growth factors, PP2A controls the phosphorylation of both Akt sites. The stimulation of both T308 and S473 phosphorylation is consistent with patterns previously reported when Akt functioned as a prosurvival protein.

Change in Apoptotic Phenotype Under Different Growth Conditions Was Accompanied by Changes in Akt-Mediated Phosphorylation.

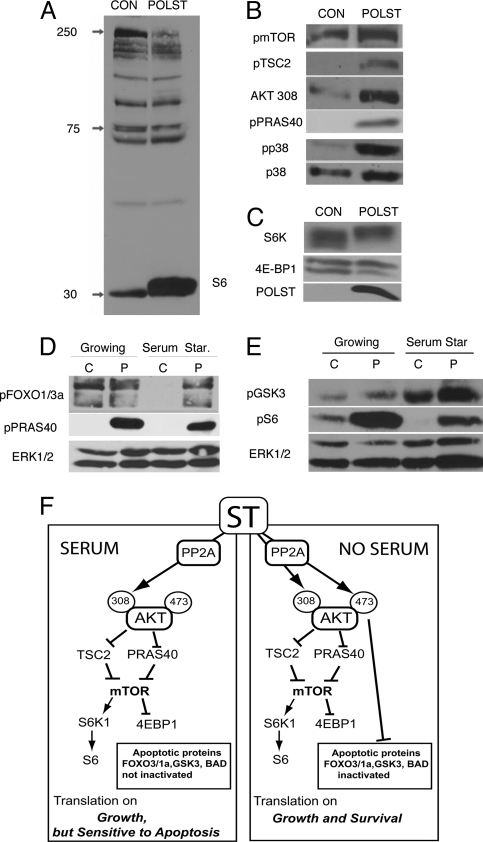

Targeting PP2A has wide-ranging, differential effects on Akt substrates. Blotting with an antibody directed against Akt phosphorylation sites (RXRXXS/T) shows that phosphorylations of some substrates are unchanged, whereas other phosphorylations increase or decrease when small T is expressed (Fig. 5A). One of the highly phosphorylated substrates was identified as S6, raising the possibility that the mTOR pathway might be involved. In the presence of serum, phosphorylation of mTOR itself, phosphorylation of the recently identified mTOR regulator PRAS40 (26) (27), and proteins both upstream (TSC2) and downstream (S6, S6 kinase, and 4EBP-1) of mTOR (28) were elevated (Fig. 5 B and C). These results suggest that activation of the pathways for regulating translation did not require stimulation of S473 phosphorylation of Akt, and partially phosphorylated Akt T308 is sufficient to activate the translational pathway. Similar observations have been made by other groups as well (29, 30).

Fig. 5.

Effects of small T on phosphorylation of Akt pathway substrates. (A) Phosphorylation of Akt substrates was assessed by blotting of extracts from control or small T-expressing cells grown in 10% serum. Akt substrate antibody that recognizes the phosphorylated consensus Akt substrate site (RXRXXS/T) was used for blotting. The identification of one band as S6 was confirmed with phosphospecific S6 antibody (data not shown). (B) Phosphorylation of mTOR pathway proteins mTOR, TSC2, and PRAS40 was determined by using phosphospecific antibody for each substrate. Phosphorylation of Akt 308 and p38 was used as a control for small T-induced signaling, and total p38 was used as a loading control. Cells were grown in 10% serum. (C) Small T expression enhances S6K and 4EBP1 phosphorylation as demonstrated by reduced gel mobilities shown in blots with anti S6K and 4EBP1 antibodies of small T-expressing compared with control cells. Cells were grown in 10% serum. (D) Some differences in signaling that change from growing conditions (in presence of serum) and serum starvation. Extracts were made from cells growing in 10% serum or after serum starvation (16–24 h). Extracts from control (C) or polyoma (P) small T-expressing cells were blotted for phosphorylation of FOXO1/3a and PRAS40 by using antibodies that detect Akt phosphorylation sites on these proteins. Total ERK1/2 was used as loading control. (E) Extracts from control (C) or polyoma (P) small T-expressing cells as in D were blotted for phospho GSK3α/β and phospho S6 by using phosphospecific antibodies. ERK1/2 was used as loading control. (F) Proposed model showing the signaling of small T in growing and serum-starvation conditions. Branch 1 shows that in growing conditions (presence of serum), small T shifts the Akt signaling to translational pathway only, whereas proteins involved in apoptosis like FOXO1/3a, GSK3, and BAD are not inactivated. In serum starvation (Branch 2), small T causes Akt phosphorylation at both S473 and T308, which activates Akt fully and causes phosphorylation of relevant substrates including FOXO1/3a, GSK3, and BAD, thereby giving protection against apoptotic signals.

Consistent with the changes in the phosphorylation of Akt between growing and serum-starvation states, there were changes in phosphorylation of some substrates as well. Under growing conditions, little or no difference was observed in the phosphorylation of FOXO1/3a or GSK3α/β between the control and small T-expressing cells (Fig. 5 D and E), suggesting that S473 phosphorylation may be important for their phosphorylation. In the absence of growth factors, where Akt phosphorylation occurs at both T308 and S473 in response to small T, the phosphorylation of proteins involved in the translational pathway like phospho PRAS40 and phospho S6 (Fig. 5 D and E), are again elevated in small T-expressing cells as compared with the controls. However, small T now stimulates the phosphorylation of FOXO1/3a and GSK3α/β at the Akt phosphorylation sites (31) (Fig. 5 D and E).

Discussion

In summary, Akt can be either a prosurvival protein or a prodeath protein in the same cell, depending on two things: the function of PP2A and what signal is being received from outside. Small T-induced apoptosis is blocked by Akt inhibitors, demonstrating that Akt is contributing directly to cell death. In cells growing in serum, there is balance between T308 and S473 phosphorylation. By targeting PP2A, small T causes unbalanced signaling with high T308 and lower S473 phosphorylation, which results in cell death. In serum-starved cells, basal levels of Akt phosphorylation are very low, and the cells undergo apoptosis. Here, small T targets PP2A to stimulate both T308 and S473 phosphorylation and promotes cell survival (Fig. 4F).

How could the balance of Akt phosphorylation affect its role in regulating cell survival? Small T via PP2A/Akt stimulates phosphorylations associated with growth by stimulating a functional mTOR (TORC1) pathway. PRAS40 and S6 are two examples of activation. This stimulation occurs when only T308, and not S473, of Akt is phosphorylated. However, limiting Akt phosphorylation to 308 is insufficient to protect cells from apoptosis, perhaps because of its inability to regulate apoptotic proteins like FOXO1/3a, GSK3, and BAD (Fig. 5 D and E and SI Fig. 10). Other proteins such as Xiap might be expected to act in the same way. Similar observations have been made by others, although under different conditions. Knockout of mSin1 led to the defective phosphorylation of Akt on S473 because of the lack of TORC2 complex formation (29, 30). As a result, cells were susceptible to apoptosis in response to various apoptotic stimuli. As in the case of small T-expressing cells, the mSin1 null cells had fully functional mTOR pathway activation, but proteins like FOXO1/3a were not phosphorylated.

Similarly, activations of PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 were shown to stimulate the dephosphorylation of Akt at S473, again leading to the unbalanced phosphorylation of Akt at T308. Likewise, these cells were susceptible to apoptosis when exposed to proapoptotic agents (4, 5). In the work presented here, control is exerted at the level of PP2A. When serum-starved cells are stimulated by serum or express small T in the absence of serum, Akt is phosphorylated in a balanced way on T308 and S473. Under these circumstances, FOXO1/3a, like PRAS 40 or S6, was phosphorylated. The result was survival. A model describing the situation is shown in Fig. 5F.

How does small T reprogram PP2A signaling to switch Akt behavior? It is unlikely to act by stimulation of PDK1, the kinase that phosphorylates T308. Examination of other PDK1 substrates, such as PKCζ did not show comparable stimulation (data not shown). It is not simply inhibition of PP2A because okadaic acid does not recreate the effect of small T on substrates (data not shown). One attractive possibility is that small T targets one or more B subunits that ordinarily regulate the ability of PP2A to dephosphorylate T308. For example, SV40 small T is known to target B56γ preferentially (32). An intriguing goal for the future would be to use disregulation of Akt phosphorylation to selectively decrease the survival of cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

Retroviral Infections.

Polyoma small T and polyoma small T defective in binding PP2A (POLST−, also known as BC1075) (33) were cloned in the Pinco vector (16) that also expresses GFP from a separate promoter. Phoenix cells stably expressing packaging proteins were transfected with small T-containing vectors by the calcium phosphate method. Briefly, 5 μg of the DNA was transfected into cells that were 60–80% confluent in 60-mm plates. After 48 h, NIH 3T3 cells were infected with the viral supernatant supplemented with 8 μg of polybrene per milliliter. Polybrene was purchased from Sigma.

Nuclear Staining.

Cells were grown on coverslips. For nuclear staining, cells were washed with PBS fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 10–15 min and permeabilized with cold methanol for 15–20 min. After washing once with PBS, cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma) for 30 min. This was followed by three to five washes with PBS for 5 min each. Coverslips were inverted and mounted on glass slides by using 50% glycerol as the mounting medium. The cells were then observed by fluorescence microscopy.

Western Blotting.

Cells were washed with cold PBS, harvested and resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH7.5; 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, in the presence of protease inhibitors (1 μg/ml leupeptin, pepstatin, and aprotinin), and phosphatase inhibitors I and II (1:100; Sigma) for 30 min. Equal amounts of protein were loaded as estimated by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad).

Antibodies against p38, phospho p38, phospho MLK3, phospho MKK3/6), MAPKAP2, Akt, phospho Akt 308 and 473, Akt substrate antibody, phospho FOXO1/3a, mTOR and phospho mTOR (Ser 2448), phospho TSC2 (Thr-1462), S6K and phospho S6K (Thr 389), S6 and phospho S6 (Ser 235/236), 4E-BP1, ERK1/2, cleaved caspase 3, AIF phospho BAD (S136), and PARP-1 were from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti phospho PRAS40 was from Invitrogen, anti polyADP polymerase (PAR) was from Trivegen, and anti-HA11 was from Covance. For polyoma small T and its mutant, PN116, monoclonal antibody that recognizes the N-terminal domain was used. Trit-C antibody and secondary antibodies were from Jackson Immunochemicals.

Immunofluorescence.

Cells were grown on coverslips, washed once with PBS, and fixed with cold methanol (−20°C) for 20 min at room temperature and washed again three times for 5 min each with TBS (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH7.4, 150 mM NaCl). Cells were quenched in fresh 0.1% sodium borohydride in TBS for 5 min, washed three times for 5 min each, and blocked with blocking buffer (10% goat serum, 1% BSA, 0.02% NaN3 in TBS) for 1 h at room temperature. This was followed by incubation with primary antibody in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C (1:100). Cells were again washed three times for 5 min each with TBS, followed by incubation with Trit-C-labeled secondary antibody at 1: 800 in 1% TBS for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were washed again three times for 5 min each and mounted on glass slides with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) that stains the nuclei. Cells were observed by fluorescence microscopy.

DNA Laddering.

DNA isolation for chromosomal fragmentation was performed as described by (25). Briefly, NIH 3T3 cells were grown in 100-mm plates, chilled on ice for 15 min, collected by scraping and centrifugation, washed once with cold PBS, and lysed in 0.4 ml of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, pH7.4, 25 mM EDTA, and 0.25% Triton X-100) on ice for 30 min. This was followed by centrifugation at 13,800 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant was treated with RNase A (200 μg/ml) at 37°C for 1–2 h, followed by incubation with Proteinase K (100 μg/ml) at 56°C overnight. The mixture was then purified sequentially with phenol-chloroform and chloroform and then precipitated with 0.1 volume of 5 M NaCl and 2 volumes of ethanol at −20°C overnight. After resuspension, equal amounts of the DNA (determined by spectrometry at 260/280 nm) were loaded on a 2% agarose gel (50 volts for 2 h), stained with ethidium bromide (1 mg/ml), and observed by UV illuminator.

Cell Cycle Analysis.

Cells were washed once with PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ and supplemented with 0.1% EDTA, and then incubated again for 5 min at 37°C in PBS/EDTA. To include apoptotic cells, cells were collected at all stages, including the ones floating in the medium, during PBS washing and after disruption by PBS/EDTA. After centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 min, the pellet was washed once with PBS supplemented with 1% serum and spun at 1,000 × g for 5 min again. The pellet was resuspended in 0.5 ml of PBS and fixed by the addition of 5–10 ml of ethanol slowly while vortexing to prevent clumping. At this stage, the cells were stored at 4°C for at least overnight in the dark. This was followed by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 min, washed once with PBS/1% serum, spun again, and resupended in 200–500 μl of propidium iodide/RNase solution (50 μg/ml propidium iodide, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, and 20 μg/ml RNase A) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Samples were then subjected to flow cytometry and analyzed by ModFit.

Inhibitor Treatment.

At 48 h after infection, cells were grown further for 2–3 days to give enough time for expression for proteins. One day before treatment, cells were split so that they were 60–70% confluent. Cells were fed with fresh medium and supplemented with the inhibitors for ≈16–24 h. Cells were then harvested for Western blotting, DNA isolation, or immunofluoresence as mentioned previously. PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002, p38 inhibitor SB203580, PARP-1 inhibitor DPQ (3,4-dihydro-5[4-(1-piperindinyl)butoxy]-1(2H)-isoquinoline), and Akt inhibitor X were from Calbiochem.

Reporter Assays.

NIH 3T3 cells were split 1 day before the transfection so that they were 30–40% confluent. For a 60-mm plate, 2–3 μg of the TK-Gal4 luciferase reporter was cotransfected with ≈1 μg of control vector or small T, 1 μg of pCMV β-galactosidase, and 1 μg of Gal4-ATF2. The calcium phosphate method was used for transfection, and the precipitate was left on the cells overnight. Medium was changed the next day, and 48 h after transfection, cells were harvested and samples were used for luciferase assays. β-Galactosidase assays done on the same samples were used to normalize the luciferase values.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants CA34722 and PO1-CA50661 (to B.S.) and CA30002 and PO1-CA50661 (to T.M.R.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0706696104/DC1.

References

- 1.Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:606–619. doi: 10.1038/nrg1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Datta SR, Brunet A, Greenberg ME. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2905–2927. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maurer U, Charvet C, Wagman AS, Dejardin E, Green DR. Mol Cell. 2006;21:749–760. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao T, Furnari F, Newton AC. Mol Cell. 2005;18:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brognard J, Sierecki E, Gao T, Newton AC. Mol Cell. 2007;25:917–931. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Millward TA, Zolnierowicz S, Hemmings BA. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:186–191. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arroyo JD, Hahn WC. Oncogene. 2005;24:7746–7755. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sontag E. Cell Signal. 2001;13:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(00)00123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strack S, Cribbs JT, Gomez L. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47732–47739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kong M, Fox CJ, Mu J, Solt L, Xu A, Cinalli RM, Birnbaum MJ, Lindsten T, Thompson CB. Science. 2004;306:695–698. doi: 10.1126/science.1100537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grethe S, Porn-Ares MI. Cell Signal. 2006;18:531–540. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn WC, Dessain SK, Brooks MW, King JE, Elenbaas B, Sabatini DM, DeCaprio JA, Weinberg RA. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2111–2123. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2111-2123.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao JJ, Gjoerup OV, Subramanian RR, Cheng Y, Chen W, Roberts TM, Hahn WC. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:483–495. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gjoerup O, Zaveri D, Roberts TM. J Virol. 2001;75:9142–9155. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.19.9142-9155.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qian W, Wiman KG. Cell Growth Differ. 2000;11:31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nolan RD, Lapetina EG. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2441–2445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu SW, Wang H, Poitras MF, Coombs C, Bowers WJ, Federoff HJ, Poirier GG, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Science. 2002;297:259–263. doi: 10.1126/science.1072221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koh DW, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Pharmacol Res. 2005;52:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong SJ, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim MY, Zhang T, Kraus WL. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1951–1967. doi: 10.1101/gad.1331805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li LY, Luo X, Wang X. Nature. 2001;412:95–99. doi: 10.1038/35083620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deschesnes RG, Huot J, Valerie K, Landry J. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1569–1582. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.6.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCormick C, Ganem D. Science. 2005;307:739–741. doi: 10.1126/science.1105779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thimmaiah KN, Easton JB, Germain GS, Morton CL, Kamath S, Buolamwini JK, Houghton PJ. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31924–31935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507057200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen HH, Zhao S, Song JG. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:516–527. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sancak Y, Thoreen CC, Peterson TR, Lindquist RA, Kang SA, Spooner E, Carr SA, Sabatini DM. Mol Cell. 2007;25:903–915. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vander Haar E, Lee SI, Bandhakavi S, Griffin TJ, Kim DH. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:316–323. doi: 10.1038/ncb1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hay N, Sonenberg N. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacinto E, Facchinetti V, Liu D, Soto N, Wei S, Jung SY, Huang Q, Qin J, Su B. Cell. 2006;127:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Q, Inoki K, Ikenoue T, Guan KL. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2820–2832. doi: 10.1101/gad.1461206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, Anderson MJ, Arden KC, Blenis J, Greenberg ME. Cell. 1999;96:857–868. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen W, Possemato R, Campbell KT, Plattner CA, Pallas DC, Hahn WC. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:127–136. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martens I, Nilsson SA, Linder S, Magnusson G. J Virol. 1989;63:2126–2133. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.2126-2133.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.