Abstract

Peptide deformylase (PDF) catalyzes the removal of formyl group from the N-terminal methionine residues of nascent proteins in prokaryotes, and this enzyme is a high priority target for antibiotic design. In pursuit of delineating the structural–functional features of Escherichia coli PDF (EcPDF), we investigated the mechanistic pathway for the guanidinium chloride (GdmCl)-induced unfolding of the enzyme by monitoring the secondary structural changes via CD spectroscopy. The experimental data revealed that EcPDF is a highly stable enzyme, and it undergoes slow denaturation in the presence of varying concentrations of GdmCl. The most interesting aspect of these studies has been the abrupt reversal of the unfolding pathway at low to moderate concentrations of the denaturant, but not at high concentration. An energetic rationale for such an unprecedented feature in protein chemistry is offered.

Keywords: peptide deformylase, protein unfolding, denaturation, guanidinium chloride, CD spectroscopy

The mechanism of protein folding and unfolding has always been a fascinating topic for protein chemists from the point of view of unraveling the physical determinants of protein stability as well as for designing stable enzymes for use in diagnostic and therapeutic kits, bioreactors, etc. (Fágáin 1995). With the exception of a few examples of “unstructured” proteins (Wright and Dyson 1999), most proteins possess well-defined three-dimensional structures, and these proteins exhibit their functional properties only in their native (folded) states (Creighton 1990). Due to its interaction with the peptide backbone as well as hydrophobic side chains, GdmCl differentially stabilizes the native, semifolded, and unfolded states of proteins (Mason et al. 2003), and thus facilitates delineation of the overall microscopic pathways of protein unfolding. It has been invariably observed that once unfolding sets in (e.g., upon addition of high concentration of GdmCl to a protein solution), it goes to completion, irrespective of the “number” of intermediary species and their intrinsic stabilities (Creighton 1990). Apparently, the energetics of the GdmCl-assisted unfolding of proteins adheres to a “descending staircase” model, in which the native and fully denatured proteins represent the top and bottom stairs, respectively, and successive intermediary species are represented by descending steps.

We recently became interested in investigating the structural–functional relationships in Escherichia coli peptide deformylase (EcPDF)-catalyzed reaction from the point of view of designing enzyme inhibitors as potential antibiotics. Peptide deformylase is a mononuclear metalloenzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of the formyl group from the N-terminal formyl-methionine residue, and it works in conjunction with methionine aminopeptidase in removing the N-terminal residues from nascent proteins (Giglione et al. 2000). Since PDF is an essential enzyme for the growth and survival of bacterial cells and its human variant has low physiological activity, it has been recognized to be a high priority target for antibiotic design (Yuan and White 2006). Several multi-targeted approaches have been pursued ever since PDF has been isolated and purified from the bacterial sources (Meinnel and Blanquet 1995).

In a cursory experiment, we observed that our purified recombinant form of EcPDF was unusually stable both at elevated temperatures as well as in the presence of GdmCl as denaturant. When we monitored the kinetic profile for the unfolding of the enzyme in the presence of GdmCl via CD spectroscopy, we observed an unprecedented phenomenon (to the best of our knowledge) in the area of protein folding/unfolding kinetics. As will be elaborated in the next section, we noted that upon incubation with GdmCl, EcPDF initially started unfolding (as observed with all proteins) (Creighton 1990), but soon after accumulation of intermediary species, the overall unfolding pathway was “abruptly” reversed. Interestingly, the latter phenomenon occurred only when GdmCl was in low to moderate concentration, but not when it was present in high concentration.

Results and Discussion

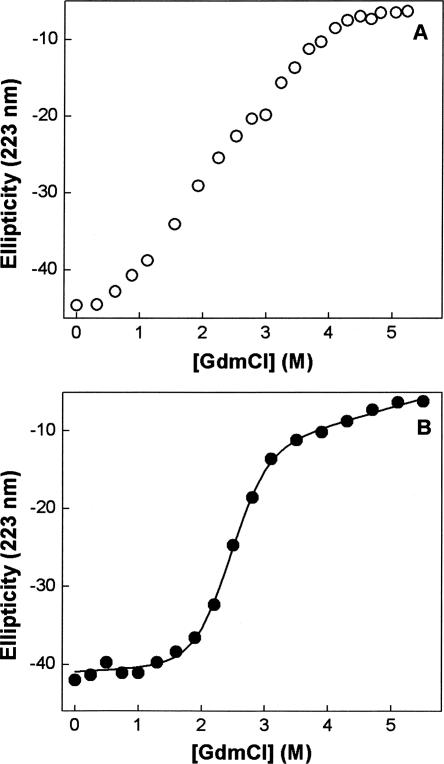

The X-ray crystallography (Chan et al. 1997) as well as NMR (Meinnel et al. 1996) data of E. coli peptide deformylase (EcPDF) reveals that the overall protein structure is comprised of about 40% α-helix, and this feature is corroborated by the CD spectral peaks in the far UV region (Rajagopalan et al. 1997). Utilizing this latter signal, we first sought to determine the energetics of the guanidinium chloride (GdmCl)-induced unfolding of our purified recombinant form of EcPDF harboring Ni(II) as the cofactor. In this endeavor, we realized that irrespective of GdmCl concentration, the denaturation of EcPDF was not complete in 5–10 min (the time regime usually taken as being adequate for establishing the equilibrium between native and denatured states of proteins), suggesting that the unfolding pathway of the enzyme was kinetically controlled. This also became evident from the fact that the molar ellipticity of EcPDF at 223 nm (θ223) did not exhibit typical sigmoidal behavior (Creighton 1990) as a function of GdmCl concentration (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, when the above species were incubated for 16 h, the θ223 value clearly exhibited the sigmoidal profile (Fig. 1B), and the unfolding profile conformed to the two-step folding–unfolding transition model of Santoro and Bolen (1988). We note that in their unfolding studies, Rajagopalan et al. (1997) also incubated the EcPDF with GdmCl for an extended time period, but offered no rationale for such a practice. The solid line of Figure 1B is the best fit of the data (according to Santoro and Bolen [1988]) for the ΔG° and m values of 4.4 kcal mol−1 and −1.8 kcal L mol−2, respectively.

Figure 1.

Guanidinium chloride (GdmCl)-induced unfolding profiles of Ni-EcPDF at 20°C as a function of the incubation time. The changes in ellipticity of EcPDF at 223 nm (θ223) as a function of GdmCl concentration for an incubation period of 5 min (A) and 16 h (B) are shown. The solid smooth line in B is the best fit of the data (according to Santoro and Bolen [1988]) for the ΔG° and m values of 4.4 kcal mol−1 and 1.8 kcal L mol−2, respectively.

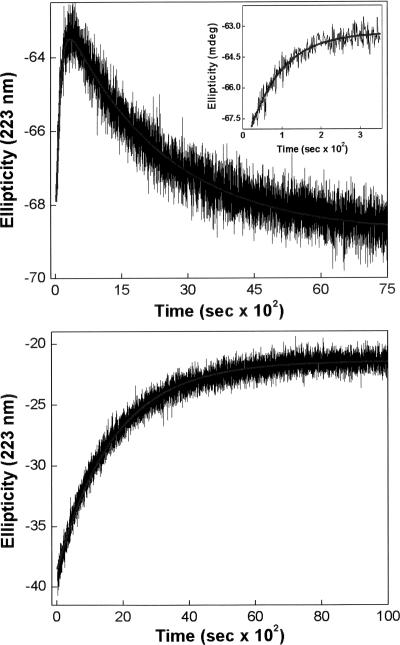

In attempting to determine the microscopic pathway for GdmCl-induced unfolding of EcPDF, we proceeded to determine the time course of changes in the CD signals (θ223) as a function of denaturant concentration. We were surprised to note that at lower concentrations (<2.0 M) of GdmCl, the protein underwent unfolding (as evident by the increase in θ223) at shorter time regimes, but then it started refolding (decrease in θ223) as the time progressed further (Fig. 2). Clearly, the pathway of EcPDF unfolding underwent an unexpected and abrupt reversal following the accumulation of some partially unfolded (metastable) intermediate. For clarity, the unfolding phase is shown as the inset of Figure 2. A complete analysis of the data of Figure 2 revealed that the overall kinetic profile of unfolding of the enzyme at 1.75 M GdmCl conformed to biphasic kinetics with rate constants of 1.0 × 10−2 (increasing phase) and 4.5 × 10−4 s−1 (decreasing phase), respectively. Contrary to this behavior, we observed that at higher (>2.0 M) concentrations of GdmCl, EcPDF simply underwent unfolding, and the time course of the overall process adhered to the single exponential rate profile, as is commonly observed with other proteins. For comparison, the kinetic trace for the unfolding of EcPDF by 3.5 M GdmCl (rate constant = 5.9 × 10−4 s−1) is also shown in Figure 2. To the best of our knowledge, the above results are unique to the GdmCl-induced unfolding of EcPDF, and there is no precedent of such a feature with other proteins.

Figure 2.

Time-dependent changes in ellipticity (θ223) of EcPDF upon incubation with 1.75 (top panel) and 3.5 M (bottom panel) GdmCl. The inset of top panel shows the magnified data of shorter time regime. The solid smooth lines are the best fit of the data according to the biphasic (top panel; k fast increasing phase = 1 × 10−2 s−1; k slow decreasing phase = 4.5 × 10−4 s−1) and single exponential (bottom panels; k = 5.9 × 10−4 s−1) rate equations.

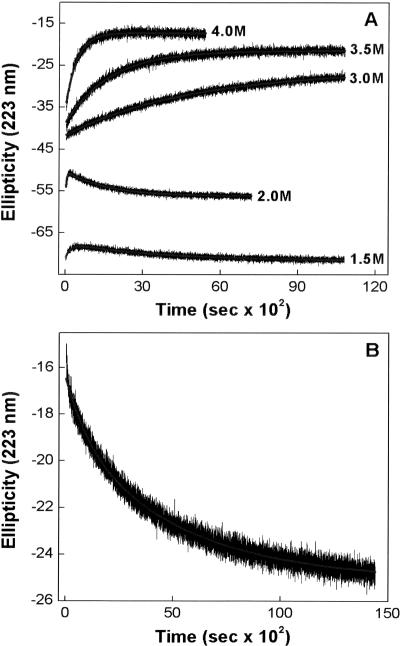

Generally, with slow unfolding proteins, whereas the rate of unfolding increases with increasing GdmCl concentration, the rate of refolding decreases (Rosengarth et al. 1999). Since the abrupt reversal of the unfolding pathway in the case of EcPDF appeared different than that observed with refolding of proteins (e.g., induced via instantaneous dilution of denaturant), we could not predict, a priori, whether the refolding rate would increase or decrease as a function of GdmCl concentration. Hence, we determined the rate constants of both unfolding and refolding processes as a function of GdmCl concentration. The experimental data (shown in Fig. 3A) revealed that both rate constants increased upon increase in GdmCl concentration. However, as observed with other proteins (Rosengarth et al. 1999), the rate of refolding of fully unfolded protein (upon dilution of the denaturant) decreased as a function of GdmCl, albeit the overall rate profile conformed to the biphasic kinetics (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Kinetic profiles for the GdmCl-induced unfolding (A) and refolding (B) of Ni-EcPDF at 25°C. (A) The time-dependent changes in θ223 in the presence of different concentrations of GdmCl. (B) The kinetic profile for the refolding (increase in θ223) of EcPDF upon diluting GdmCl (present in the equilibration mixture) from 4.0 M to 2.0 M. The solid lines are the best fit of the data as described in the legend of Figure 2. The resultant parameters are summarized in a table in the Electronic supplemental material.

In attempting to explain the molecular mechanism of reversal of the guanidinium chloride induced unfolding pathway of EcPDF, we hypothesized that the loss of the enzyme bound Ni2+ upon unfolding increased the energy level of the intermediate such that its conversion back to the native state (vis à vis the unfolded state) was more favorable. Unfortunately, our transient kinetic data for the GdmCl-induced unfolding of EcPDF on a shorter (millisecond) timescale did not support such a model. The latter studies, however, revealed that prior to the observed unfolding phase(s) of the enzyme (via CD spectroscopy) at least two intermediary species predominated during the course of the changes in the coordination geometry of the enzyme bound Ni2+ (A.K. Berg, S. Manokaran, D. Eiler, J. Kooren, S. Mallik, and D.K. Srivastava, unpubl.).

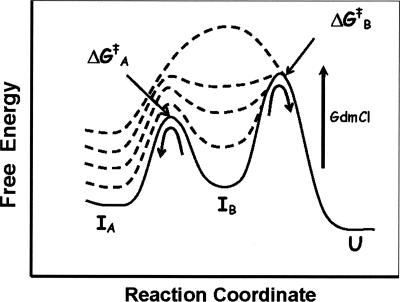

A cumulative account of all the experimental data led to formulation of the energetic basis for unfolding of EcPDF as a function of GdmCl concentration. As per the free energy diagram cartoon of Figure 4, at lower concentration regimes of GdmCl (i.e., <2.0 M), one of the intermediary species (denoted by IB, believed to be formed following the accumulation of intermediary species during the stopped-flow time regime) starts accumulating. This species “tests” the energy barrier to either go forward (i.e., undergoing further unfolding via ΔG ‡ B) or return backward (i.e., undergoing the refolding process via ΔG ‡ A). Since at lower concentrations (<2.0 M) of GdmCl, ΔG ‡ B emerges out to be higher than ΔG ‡ A, EcPDF undergoes “abrupt” refolding upon attaining an appropriate free energy of IB. As the concentration of GdmCl increases, the ground state energy of IB increases more rapidly than those of the flanking transition states, leading to the merger of ΔG ‡ A and ΔG ‡ B into a common transition state barrier. Hence, IB no more predominates at higher (>2.0 M) concentrations of GdmCl, and thus the overall unfolding pathway proceeds in the forward direction, obviating the reversal of the unfolding pathway as observed at lower concentrations of GdmCl. Whether the observed phenomenon is unique for EcPDF (as its origin is believed to lie in the differential stabilization of one of the ground or transition state species formed during the overall unfolding pathway) or it is prevalent with other proteins must await further investigation. We are currently in the process of delineating the structural basis of GdmCl-induced unfolding and refolding pathways of PDF via NMR spectroscopy, and we will report these findings subsequently.

Figure 4.

Cartoon of the free energy diagram for the unfolding of EcPDF in the presence of increasing concentrations of GdmCl.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, expression, and purification

The genomic DNA of E. coli was prepared from BL21 cells by following the standard molecular biology protocol of Ausubel et al. (1994). The coding sequence of E. coli peptide deformylase (EcPDF) (Mazel et al. 1994) was amplified by PCR using the purified genomic DNA as a template (as elaborated in the Electronic supplemental material). The PCR reaction product and the expression vector pET–20b(+) (EMD Biosciences) were digested with NdeI and XhoI and purified from an agarose gel using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). The purified products were ligated by T4 DNA ligase (forming EcPDF–pET plasmid) and transformed into both E. coli DH5α cells for plasmid propagation and E. coli BL21–RIL for protein expression.

The expression and purification of Ni2+-substituted E. coli peptide deformylase was accomplished essentially as described by Ragusa et al. (1998) with only minor modifications (described in the Electronic supplemental material). The protein concentration of EcPDF was determined via the Bradford assay using BSA as standard (Bradford 1976).

Circular dichroism

The kinetic and thermodynamic studies for unfolding of EcPDF in the presence of guanidinium chloride (GdmCl) were performed on a Jasco J-815 spectropolarimeter using a 1-mm path length quartz cuvette.

Thermodynamic studies for the unfolding of EcPDF in the presence of high concentrations of GdmCl were initially performed at 20°C by monitoring the changes in the CD signal at 223 nm. During these studies, the enzyme (35 μM in 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 5mM NiCl2) was either titrated with increasing concentrations of GdmCl, and the CD spectra (the average of 5 scans) acquired within 5 min of denaturant addition or individual aliquots were made at various denaturant concentrations and allowed to equilibrate for 16 h prior to scanning.

To ascertain the kinetics of unfolding of EcPDF, we incubated 55 μM enzyme with different concentrations of GdmCl and monitored the time-dependent changes in θ223. To avoid an increase in the local concentration of the denaturant for more than few seconds, we mixed the enzyme with GdmCl by rapidly shaking and inverting the CD cells. To ensure that the denaturant-induced unfolding of EcPDF was reversible, we performed the following dilution experiment: 55 μM enzyme was mixed with 4.0 M GdmCl, allowed to equilibrate for 35 min, and then the mixture was instantaneously diluted with buffer to reduce the concentration of GdmCl to the desired level. In both cases, the time dependence of θ223 was monitored and data conformed to either monoexponential or biphasic kinetic equations (described in the Supplemental material).

Electronic supplemental material

The electronic supplemental material contains the far-UV CD spectrum of EcPDF, a table summarizing the kinetic data, and supplemental methods, as indicated in the text.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH and NSF Grants CA113746 and DMR-0705767, respectively, to D.K.S. and S.M.

Footnotes

Supplemental material: see www.proteinscience.org

Reprint requests to: D.K. Srivastava, Department of Chemistry, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, North Dakota State University, Fargo, North Dakota 58105, USA; e-mail: dk.srivastava@ndsu.edu; fax: (701) 231-8324.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.073270608.

References

- Ausubel, F.M., Brent, R., Kingston, R.E., Moore, D.D., Seidman, J.G., Smith, J.A., Struhl, K. Current protocols in molecular biology. Supplement 30. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 1994. Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria; pp. 2.4.2–2.4.2. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, M.K., Gong, W., Rajagopalan, P.T.R., Hao, B., Tsai, C.M., Pei, D. Crystal structure of the Escherichia coli peptide deformylase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:13904–13909. doi: 10.1021/bi9711543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creighton, T.E. Protein folding. Biochem. J. 1990;270:1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj2700001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fágáin, C.O. Understanding and increasing protein stability. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1252:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(95)00133-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giglione, C., Pierre, M., Meinnel, T. Peptide deformylase as a target for new generation, broad spectrum antimicrobial agents. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;36:1197–1205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, P.E., Neilson, G.W., Dempsey, C.E., Barnes, A.C., Cruickshank, J.M. The hydration structure of guanidinium and thiocyanate ions: Implications for protein stability in aqueous solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100:4557–4561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0735920100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazel, D., Pochet, S., Marlière, P. Genetic characterization of polypeptide deformylase, a distinctive enzyme of eubacterial translation. EMBO J. 1994;13:914–923. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06335.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinnel, T., Blanquet, S. Enzymatic properties of Escherichia coli peptide deformylase. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:1883–1887. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.7.1883-1887.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinnel, T., Blanquet, S., Dardel, F. A new subclass of the zinc metalloproteases superfamily revealed by the solution structure of peptide deformylase. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;262:375–386. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragusa, S., Blanquet, S., Meinnel, T. Control of peptide deformylase activity by metal cations. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;280:515–523. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan, P.T.R., Yu, X.C., Pei, D. Peptide deformylase: A new type of mononuclear iron protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:12418–12419. [Google Scholar]

- Rosengarth, A., Rösgen, J., Hinz, H.J. Slow unfolding and refolding kinetics of the mesophilic Rop wild-type protein in the transition range. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;264:989–995. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, M.M., Bolen, D.W. Unfolding free energy changes determined by the linear extrapolation method. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8063–8068. doi: 10.1021/bi00421a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, P.E., Dyson, H.J. Intrinsically unstructured proteins: Re-assessing the protein structure–function paradigm. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;293:321–331. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z., White, R.J. The evolution of peptide deformylase as a target: Contribution of biochemistry, genetics and genomics. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006;71:1042–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]