Abstract

A cardinal feature of Parkinson’s disease (PD) is muscle hypertonicity, i.e. rigidity. Little is known about the axial tone in PD or the relation of hypertonia to functional impairment. We quantified axial rigidity to assess its relation to motor symptoms as measured by UPDRS and determine whether rigidity is affected by levodopa treatment. Axial rigidity was measured in 12 PD and 14 age-matched controls by directly measuring torsional resistance of the longitudinal axis to twisting (±10°). Feet were rotated relative to fixed hips (Hip Tone) or feet and hips were rotated relative to fixed shoulders (Trunk Tone). To assess tonic activity only, low constant velocity rotation (1°/s) and low acceleration (<12°/s2) were used to avoid eliciting phasic sensorimotor responses. Subjects stood during testing without changing body orientation relative to gravity. Body parts fixed against rotation could translate laterally within the boundaries of normal postural sway, but could not rotate. PD OFF-medication had higher axial rigidity (p<0.05) in hips (5.07 Nm) and trunk (5.30 Nm) than controls (3.51 Nm and 4.46 Nm, respectively), which didn’t change with levodopa (p>0.10). Hip-to-trunk torque ratio was greater in PD than controls (p<0.05) and unchanged by levodopa (p=0.28). UPDRS scores were significantly correlated with hip rigidity for PD OFF-medication (r=0.73, p<0.05). Torsional resistance to clockwise versus counter-clockwise axial rotation was more asymmetrical in PD than controls (p<0.05), however, there was no correspondence between direction of axial asymmetry and side of disease onset. In conclusion, these findings concerning hypertonicity may underlie functional impairments of posture and locomotion in PD. The absence of a levodopa effect on axial tone suggests axial and appendicular tone are controlled by separate neural circuits.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, muscle tone, hypertonicity, rigidity, levodopa, axial musculature

Introduction

Clinicians routinely assess neuromotor status in many motor disorders by measuring muscle tone. A cardinal symptom of Parkinson’s disease (PD) is muscle hypertonicity or rigidity. Most methods for assessing muscle tone have focused on appendicular rigidity including the arms, wrists, and knees (Meara and Cody, 1992, Meara and Cody, 1993, Prochazka, et al., 1997), even though the bulk of the musculature is axial and proximal. Stabilization of the trunk is very important to posture and gait and there are many mechanisms by which this is accomplished, particularly by controlling forces at the hip. In fact, disturbance to the control of axial segments may underlie many of the gait and postural impairments found in PD. The relevance of axial tone to functional impairments of gait, balance and motor control have been described in some studies (Horak, et al., 1996, Lakke, 1985, Prochazka, et al., 1997, Schenkman, et al., 2000, Steiger, et al., 1996, Tanigawa, et al., 1998, Weinrich, et al., 1988), however, none of these studies used direct measures of axial tone because the techniques for measuring limb and neck tone are difficult to apply to the trunk and hips.

A few direct measures of axial tone in PD have been reported. A bedside technique for measuring axial rigidity has been used to assess trunk tone by manipulating the legs and hips while the patient was supine (Nagumo and Hirayama, 1993, Nagumo and Hirayama, 1996). In these two studies, PD subjects were found to have greater tone than controls, but a drawback of this technique is that in the supine position, the body is relaxed and postural tone is reduced, making this technique useful only when tone is very high. A more recent study quantified differences in trunk tone between PD and healthy individuals using a device that isokinetically flexed and extended the trunk (Mak, et al., 2006). PD subjects had greater resistance in comparison to healthy controls during trunk extension, and to a lesser extent during flexion, but only when the trunk was repositioned with high angular velocities (>60°/sec). A drawback of the isokinetic technique is that subjects were strapped to the passive motion device, so that although the subjects were standing erect, their posture was supported, which may have altered the level of axial tone. Furthermore, fast, axial bending is likely to have evoked phasic sensorimotor responses from cervical, vestibular, and stretch reflexes. Finally, neither the bedside nor the isokinetic technique isolated and measured hip torque; instead, these techniques focused on the trunk alone. To measure more directly axial and proximal tone, Gurfinkel and colleagues (2006) developed a novel device to twist torsionally the body about the vertical axis.

The axial musculature is anatomically and physiologically complex. The axial muscles are controlled by a number of cortical and sub-cortical structures via somatic descending brain stem and monoaminergic pathways (Kuypers, 1964, Kuypers, 1981), which are distinct from the descending tracts leading to limb motor neurons. Because of this difference in supraspinal inputs, the axial musculature might respond differently to pharmacological treatment for hypertonicity compared to that of the extremities (Weinrich, et al., 1988). Structurally, the axial musculature links all parts of the body together. Postural stability and controlled mobility require constant activity of axial muscles, since any movement of the distal parts of the body must be compensated proximally. Tonic regulation of axial muscles is, therefore, a necessity for movement to be coordinated (Hesse, 1943). Although the tonic activity of postural regulation involves low levels of axial muscle activity, at least in comparison to the levels of superimposed phasic activity during rapid changes in body orientation, it is much higher than the resting tonic activity of appendicular muscles and quite important for effective movement.

In a recent study performed on standing subjects, the resistance of the neck, trunk, and hips to low velocity (≤1°/sec) torsional rotation was measured to assess tonic postural control in the axis. The torsional device tested subjects in the active postural state and did not displace the body center of gravity or restrict standing posture in any direction other than torsionally (Gurfinkel, et al., 2006). This study showed that the level of axial tone differed at different levels of the axis, e.g., the resistance of the trunk to rotation was much greater than that of the hip. Because the vertical segments of the body are not passively stable, they must be actively controlled. In particular, the heads of the two femurs pivot on the pelvis to balance everything above it. This biomechanical relation may be especially relevant to the current study, because the stooped posture characteristic of PD may enhance static torque at the hip even more than in the trunk. Unlike previous studies of axial rigidity in PD, the current study isolated and evaluated hip as well as trunk rigidity.

We hypothesize that direct measures of axial resistance to twisting will reveal that axial tone differs in PD subjects from that of healthy individuals. The three main goals of the current study were to: 1. Quantify low-level tonic activity during natural postural control in PD and control subjects. Both vertical and lateral segmental distributions of axial tone were examined. Parkinsonism typically begins unilaterally, and limb tone is often asymmetrical. Whether asymmetrical limb tone is associated with asymmetrical axial tone is unknown. 2. Determine the relation of axial rigidity to motor symptoms. No studies conducted on PD axial symptoms have correlated direct measures of axial rigidity to clinical scales. 3. Evaluate whether the tonic muscle activity of the axis is affected by treatment with levodopa.

Methods

Subjects

A total of 12 Parkinson’s disease (PD) subjects (66±11 yr old) undergoing treatment with L-DOPA and 14 healthy age-matched control subjects (65±10 yr old) participated in this study. The patients were selected based on being H&Y ≥ 1.5, which is characterized as PD with axial involvement, however they were not preselected based on having high axial rigidity as measured by UPDRS neck tone. All subjects provided informed consent in accordance with the Oregon Health & Science University Internal Review Board regulations for human subjects’ studies and the Helsinki Declaration.

The Parkinson’s subjects were tested in the morning after abstaining from anti-Parkinsonian medication overnight; the wash-out period was at least 12 hrs in the OFF-medication state. Subjects OFF-medication were assessed with the motor part of the UPDRS prior to participating in the experimental protocol. All subjects were able to stand for periods of ≥15 min without rest. After the subjects completed the OFF-medication portion of the protocol, they took their normal morning dosage of medications. The protocol was then repeated ON-medication. Once PD subjects reported that they felt “ON”, the UPDRS motor score was obtained. The UPDRS scores decreased for all PD subjects when ON-medication (20.7±11.6 SD) compared to when OFF-medication (33.4±13.4 SD) (paired 2-tailed t-test; p<0.0001).

Protocol

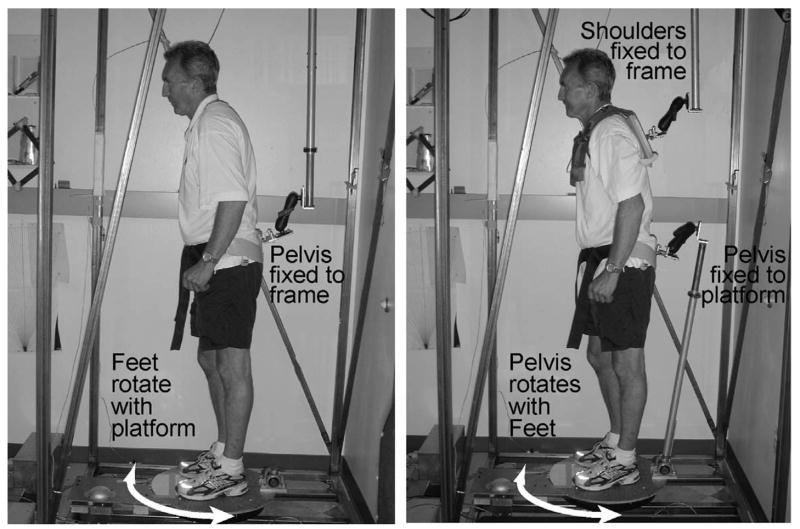

The torsional rotation device consists of a steel frame surrounding a rotating platform under the standing subject (Fig. 1). The steel frame and the rotating platform each has a fixation point for a steel rod that attaches to the subject with a harness at the opposite end. This attachment ensures that one part of the axis remains fixed relative to the floor, while another part is rotated about a vertical axis passing through the trunk roughly collinear with the spine. A torque sensor (Futek TFF400, Irvine, CA) located on the attachment between the frame and the body was used to measure the resistance of the body segment to passive rotation. This method for measuring axial tone and the equipment involved have been shown to be a repeatable-reliable measure of axial tone in healthy individuals (Gurfinkel, et al., 2006). The resistive torque of the subject and the platform position were digitized and recorded at 50 samples/s using Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Devices, Cambridge, UK) and analyzed offline using Matlab software (Mathworks, Natick, MA).

Figure 1.

Left: The torsional platform rotates the feet relative to the fixed pelvis while the sensor measures hip stiffness. Right: The platform twists the feet and pelvis together relative to the fixed trunk while the sensor measures trunk stiffness. The photo shows PD subject #11 from Table 1.

Several experimental conditions were investigated. In one condition (PD: n=12; CTL: n=14), we quantified the axial resistance to trunk rotation relative to the hips (Trunk Tone). A harness, snuggly attached to the subject’s shoulders, was attached to the steel frame by a double-hinge that allowed the subject to move translationally, but not torsionally. The shoulders were rigidly fixed to the external rigid frame to prevent torsional rotation while the platform under the subject cyclically rotated the feet and pelvis ±10° clockwise (CW) and counter-clockwise (CCW) with a saw-toothed pattern for 3–5 cycles. Each full cycle of torsional rotation lasted 40 s. The pelvis and feet were rotated together by the platform via an orthosis snugly fitted to the hips. The orthosis was mounted to a rigid pole linked at the other end to the rotating platform. The link between the orthosis and the platform was single-hinged to allow free anterior-posterior translation, while allowing no rotation of the hips relative to the feet.

In another condition (PD: n=10; CTL: n=13), we used the same rotation parameters as in the Trunk Tone condition, but a different fixation configuration (Hip Tone). The fixations in the Hip Tone condition allowed the legs to be passively rotated relative to a fixed pelvis in order to test hip muscle rigidity. The pelvis orthotic was attached, via the double-hinged bar to the rigid frame, while the feet were rotated by the platform. The shoulders were completely free in this condition. As the platform rotated the feet, the pelvis remained fixed relative to the floor, thus isolating the hip muscles.

The hinged connections to the platform and frame that allowed translation without rotation were employed to create a relatively natural mechanical environment for quiet stance. The set-up required the subjects to maintain standing equilibrium, as well as to prevent them from using fixed parts of the body as a spatial reference. The fixation linkages provided the degrees of freedom necessary to spontaneously sway within the normal base-of-support. In this way, postural tone was measured under conditions where it was tonically engaged in maintaining upright posture, rather than in a lesser or inactive state such as during supported stance or while lying supine. A very slow rotational speed was used to avoid muscle stretch reflex activation (Pisano, et al., 1996). Accordingly, the acceleration profile during reversals in direction (<12°/s2) and the velocity profile during motion (1°/s) were designed to create a tonic input devoid of phasic sensory events. Because subjects maintained orthograde posture and only passive twisting about the longitudinal body axis was applied, no imposed shifts in body mass or changes in orientation of the body relative to gravity occurred. The attachments to the body and fixation linkages were counterweighted with springs so no unnatural loading affected the postural behavior.

Data Analysis

For both Hip and Trunk Tone conditions, axial resistance was determined for each subject by calculating the net difference in peak-to-peak torque of all cycles of rotation. The symmetry of torsional resistance was defined as the difference in average peak torque during CW rotations and that during CCW rotation. The equation for lateral torque asymmetry (Eq. 1) can be described as the average absolute difference in resistance between CW and CCW rotation (refer to Fig 4), with zero representing perfect symmetry in resistance to CW and CCW rotation.

Figure 4.

Asymmetries in torsional stiffness to rotation of the trunk and hip are greater in PD subjects than in control subjects (upper). The raw data shows trunk stiffness during ±10° platform rotation (lower). The top trace of raw data shows the symmetrical trunk resistance of a representative age-matched healthy control subject and the middle trace shows trunk resistance of a PD patient OFF-medication. The torque asymmetry of the trunk (or hip) is calculated by taking the average of absolute differences between consecutive unsigned peaks of torque (pi, pi+1, … pn). Error bars indicate the standard error; *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

| (Eq. 1) |

The Pearson’s product moment correlation was used to quantify the interrelation of variables in all regressions. Paired t-tests were used to compare PD subjects when ON and OFF-medication. Unpaired t-tests were used to compare PD to control subjects. Significance was set at α = 0.05.

Results

Axial rigidity segmental distribution

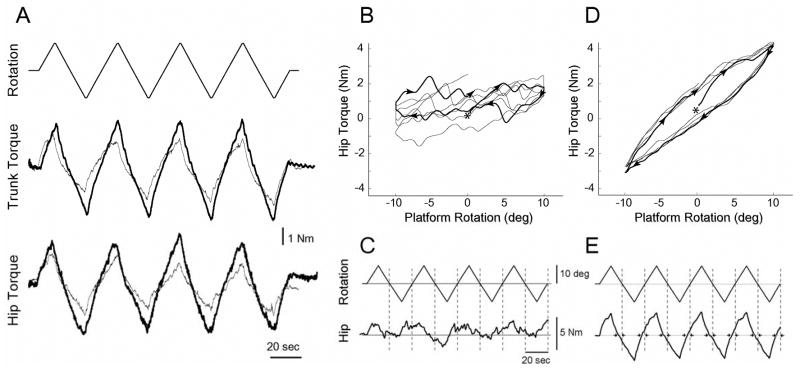

A representative trace for axial resistance to torsional rotation in the trunk and hips is shown in Figure 2 for one PD subject (thick trace) and an age-matched control (thin trace). Torque resistance to rotation was higher at both the hip and the trunk in the PD subjects compared to control subjects. On average, the axial muscle tone in PD subjects OFF-medication in both trunk and hips was elevated compared to control subjects (p ≤ 0.05). Mean trunk torque was 5.30 (SE 0.34) Nm in PD subjects OFF-medication and 4.46 (SE 0.36) Nm in control subjects. Mean hip torque was 5.07 (SE 0.56) Nm in PD subjects OFF- medication and 3.51 (SE 0.55) Nm in control subjects (Fig. 3). The ratio of hip-to-trunk torque was 0.77 (SE 0.09) for the elderly control subjects and 1.01 (SE 0.10) for the PD subjects OFF-medication (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 2.

Raw data of axial resistance to twisting showing differences in healthy and PD subjects in both magnitude and modulation. A. Comparison of torsional resistance in the trunk and hips of a representative Parkinson’s subject OFF-medication (thick line) and an age-matched control (thin line). Top trace is platform position with upward movement representing counterclockwise rotation (±10°, 1°/s). B shows the flattened torque-angle relation in the hip of a healthy subject during platform rotation suggesting high muscle modulation and C shows the same trace across time. D and E show much lower hip modulation but higher resistance in one PD subject ON-medication. E. Zero crossings of platform rotation show phase advances (small arrows:→←). The same scales are used in C and E.

Figure 3.

Average torsional stiffness of the trunk and hips of Parkinson’s subjects OFF-medication (gray) and ON-medication (black), and of age-matched control subjects (white). Error bars indicate the standard error; *p<0.05.

Axial rigidity lateral asymmetry

The asymmetry (Eq. 1) in resistance to torsional rotation was greater in PD subjects than in age-matched control subjects (Fig 4). For Trunk Tone (i.e., hip rotation with fixed shoulders), the mean torque asymmetry was 1.16 (SE 0.19) Nm in PD subjects OFF-medication, 0.75 (SE 0.20) Nm in PD subjects ON-medication, and 0.43 (SE 0.06) for control subjects (p ≤ 0.0005). The mean torque asymmetry for Hip Tone was 0.81 (SE 0.18) Nm for PD subjects OFF-medication, 0.99 (SE 0.24) Nm when ON-medication and 0.56 (SE 0.11) Nm for control subjects (p < 0.05). These results indicate that PD subjects had a more pronounced asymmetry in axial tone than healthy individuals. Interestingly, no relation between the direction of axial torque asymmetry and limb asymmetry or side of disease onset was found.

UPDRS correlations with axial rigidity

The UPDRS Part III motor scores correlated with the torsional stiffness of the hips (r=0.73, p<0.05) and tended towards a significant correlation with the trunk (r=0.53, p=0.08) for PD subjects when OFF-medication (Fig. 5, top row). However, the sub-scores of the motor UPDRS for items most pertinent to axial musculature, i.e. PIGD – Postural instability and gait difficulty, UPDRS items 27–30: arising, posture, gait, postural stability (Adkin, et al., 2003, Jacobs, et al., 2006) did not correlate with axial tone. The UPDRS rigidity score, which is the sum of the neck, arms and legs (UPDRS, item 22), accounted for a large portion of variability in the axial torque measures (Hip: r=0.78, Trunk: r=0.70, p<0.01) (Fig. 5, bottom row).

Figure 5.

Relationship between hip torque (left column) or trunk torque (right column) with all of UPDRS Part III (top row) or UPDRS Rigidity Item 22 (bottom row) in Parkinson’s disease subjects OFF-medication. Regression lines (solid) and 95% confidence intervals (dotted) are displayed.

Levodopa effect on axial rigidity

Levodopa had no significant effect on axial tone in PD subjects. Paired t-tests showed no significant influence of medication on trunk tone, 5.30 Nm (OFF) vs. 5.11 Nm (ON) (p=0.25) or on hip tone, 5.07 Nm (OFF) vs. 4.93 Nm (ON) (p=0.35). The ratio of hip-to-trunk torque also did not differ when PD subjects went from the OFF-medication state (1.01) to the ON-medication state (0.98) (p=0.28), suggesting that levodopa is not effective at reducing axial hypertonicity. There was no significant effect of levodopa on lateral torque asymmetry, either in the trunk (p=0.08) or in the hips (p=0.28). Ordering effects which may have occurred due to the fixed sequence which OFF- then ON-medication necessitated appeared to be absent. This was verified, first in PD subjects who were tested on multiple trials within a state of either ON- medication or OFF-medication, which showed no change in torques of hip or trunk within that state (p>0.10), and second in the healthy subjects who were tested in the entire protocol twice in the same day (to match what was required of the PD subjects), which also showed no significant change in torque measures across trials (p>0.10).

Active mechanisms of muscle response

A flattened torque-angle relation suggesting high levels of active muscle modulation could be seen in just over half of the healthy subjects (7/13) in the Hip Tone condition (Fig. 2B), but only one PD subject when ON-medication showed a moderately flattened torque-angle relation, and none when OFF-medication. In the Trunk Tone condition, only two healthy subjects showed flattening in the torque-angle relation but none in the PD group. All subjects did show non-linear resistance to the changing angle of rotation with phase leads relative to platform zero crossings (e.g. Fig. 2E), which can be due to a combination of active and passive properties.

Discussion

Torsional rotation of the axial body segments of standing PD subjects and age-matched controls revealed that: 1) axial rigidity was elevated, particularly in the hips, and abnormally distributed in PD subjects compared to control subjects, 2) objective measures of axial rigidity correlate with clinical UPDRS measures of the disease, and 3) levodopa does not significantly reduce axial rigidity.

Increased rigidity in axial muscles in PD

Increased rigidity in the trunk and hips was observed in PD (Fig. 2 and 3) using a method which has been shown to reflect the active modulation of tone in the axial musculature during a naturalistic postural task (Gurfinkel, et al., 2006). With this method, we have been able to describe a number of properties of axial tone that have not been previously quantified. Slow twisting of axial muscles (i.e., at 1°/s) during standing avoids phasic reflex responses of the muscles. In contrast to our methods, a recent study employed relatively fast passive flexion and extension movements of the trunk (Mak, et al., 2006). These investigators reported that axial resistance to trunk bending was increased in PD subjects compared to healthy controls, which the authors reported as axial hypertonia and hypothesized to be a result of medium or long-length reflex loops (Bergui, et al., 1992, Lee, 1989). However, Mak et al. (2006) noted that differences in axial resistance between PD and control subjects were only found at trunk bending speeds of >60°/s, so that the observed differences is more likely due to phasic reflexes than to tonic activity. At these higher speeds of trunk flexion and extension, the authors show a large difference in peak torque between PD and control subjects; however, the role of passive spring-like properties of structures such as vertebral disks, capsular and longitudinal ligaments, aponeuroses, and the linea alba cannot be excluded considering the velocity and range of trunk motion employed. In this and our previous studies of axial tone, we minimized the contributions of potentially confounding passive mechanical properties by working within the neutral zone (±10°) of the axis (Kumar, 2004, Kumar and Panjabi, 1995, Panjabi, 1992).

Other potential physiological differences arise when using axial twisting versus axial bending. Changing the orientation of the upper body and head can evoke vestibulospinal and cervicospinal reflexes, which may alter the resistance to trunk bending. Again, we minimized the contributions of such reflexes by rotating the trunk about the longitudinal axis. Finally, axial rotation optimally lengthens and shortens axial muscles because of the pinnate orientation of these muscles relative to the longitudinal axis. These differences in technique are described to make the point that, in order to measure axial tone, the testing conditions should be naturalistic, the speed of movement should be below the threshold of phasic reflexes, and motion should be in a region of joint space where passive resistance is very low or absent.

An important finding in the study by Gurfinkel and colleagues (2006) was that axial tone is actively modulated. Specifically, muscle lengthening and shortening reactions, which are opposite in direction to classic stretch reflexes (Sherrington, 1909), were present in the axial muscles of healthy adults during torsional twisting. In the current study, these reactions can also be seen most clearly in the phase plot of hip torque of the healthy subject (Fig. 2B). A flattened torque-angle relation appeared in only one PD subject which suggest some alteration in tonic muscle response, because most PD subjects showed much less modulation than healthy subjects (e.g. Fig. 2E). Tanigawa and colleagues (1998) were able to recognize enhanced shortening reactions in PD, by measuring axial EMG activity while performing Nagumo and Hirayama’s (1993) bedside technique, however, this was only found in patients with very high tone while supine. Our results suggest that although neural mechanisms such as shortening and lengthening reactions appear to be present in the axial musculature, they do not seem to be enhanced in PD relative to healthy subjects during active postural maintenance.

Shortening reactions have also been found to be enhanced or altered in PD in the limbs (Angel, 1982, Xia and Rymer, 2004), although a distinction may be made between the tonic state of appendicular and axial muscles and dissociable pathways innervating the muscle groups. Furthermore, much higher velocity movements were used in their studies (≥50°/s) than in the current study. Independent of differences in ours and earlier findings these active muscle responses appear to reflect a pathological state in the underlying tonic activity of the central nervous system. Although some of these results may appear contradictory, it was shown (Beritoff, 1915) in the decerebrate cat that tone fluctuated, but tonic neck reflexes appeared only when tone reached a specific level, which suggests that at least some reflexes operate only within an optimal tonic range. Such a finding also suggests that diseases affecting tone may have wide-ranging deleterious effects on motor behavior, in general. Indeed, the constellation of motor symptoms in PD may be just such an outcome of a tonic disorder.

Rigidity along axial segments abnormally distributed in PD

There are a number of reasons why the distribution of muscle tone differs at different axial levels in healthy individuals (Fig. 3). The masses of the different axial segments of the body are not vertically aligned. The center of mass of the head is in front of the neck, so the neck muscles must remain active to keep the head from falling forward. This is also true for the trunk, which has a center of mass that is anterior to the spinal column and the hip joint (Erdmann, 1997). Thus, in a terrestrial environment, the body is not structurally designed to optimize static equilibrium, and gravity creates a constant static torque on the hips. In fact, since the axis links the head and extremities, any targeted limb or head movement must be accompanied by a compensatory action in the body axis. The precise calibration of axial muscle during quiet standing and gait is likely to be easily disturbed by small changes in either the phasic control of axial musculature or the underlying tonic level of axial muscle activity (Carpenter, et al., 2004, Vaugoyeau, et al., 2006). Future studies should attempt to determine the relationship between axial tone and quantitative measures of gait and posture that are more sensitive than those measured by the UPDRS.

In healthy individuals, different moment arms, masses, and sizes of the axial muscles involved in standing suggest that antigravity axial tone may differ at different levels of the axis. When directly measured, the ratio of static hip-to-trunk torque in young healthy subjects was found to be <0.7 (Gurfinkel et al 2006). Static torque normally arises from a misalignment of axial masses with the underlying support structure, but such torque is likely to be magnified by the flexed posture commonly associated with Parkinson’s disease. With the trunk and head stooped forward, the center of mass of the upper body requires back and hip extensors to oppose a larger torque than normal. In fact, the evidence from our study shows that the ratio of hip-to-trunk torque increases in PD subjects. Although both hip and trunk torque levels were higher in PD subjects relative to control subjects, a larger difference between the two groups was found in the hip than in the trunk torque. This finding supports the possibility that increased tone in the hips is due to the stooped posture of PD, but we cannot discount alternative interpretations. One alternative possibility is that antigravity muscle activity is exaggerated, not due to a bent posture, but rather to counteract higher tonic activity of the anterior muscle groups such as internal/external obliques and rectus abdominis (Zhang, et al., 1999).

Axial asymmetries enhanced in PD

In the early stages of Parkinson’s disease symptoms often develop unilaterally, but in later stages these asymmetries fade. In the study described here, we also found asymmetry in axial rigidity in a sample of patients with a wide range of disease severity, but we found that the magnitude of asymmetry was independent of disease severity. Furthermore, these torsional asymmetries were as often opposite in direction to the side of disease onset as they were in the same direction. Our measure of torque asymmetry (Eq. 1) was not normalized for the higher tone found in PD subjects, which may have contributed to the significantly larger asymmetry present in PD subjects (Fig. 4). Although normalizing the lateral tone differences for the higher PD tone reduces the difference between healthy controls and PD subjects, we argue that the presence of larger absolute axial tone asymmetries in PD patients is just as important to the functioning of the CNS as are normalized axial torque asymmetries. The PD CNS is still left with the responsibility of controlling motor function in the presence of higher tone and larger lateral asymmetry.

Behavioral asymmetries have been linked to the side of nigrostriatal neuron loss in humans (Kempster, et al., 1989, Kumar, et al., 2003), which is also supported by findings from animal lesion studies (Fornaguera, et al., 1994). The origin of asymmetrical axial tone may be a central compensation for these early appendicular symptoms. Conversely, it may be directly caused by asymmetrical activation in basal ganglia-brain stem pathways. The basal ganglia outflow bilaterally projects directly towards areas in the brain stem involved in locomotion and postural muscle tone, such as the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus, midbrain locomotor region, and muscle tone inhibiting reticulospinal neurons in the medulla (Takakusaki, et al., 2004). The increased lateral asymmetry of axial tone in PD may be compensation for the increase in tone in the extremities, which would be primarily due to contralateral basal ganglia-cortical-spinal loops. But movement in a limb must be accompanied by activity in the axial muscles as they work to maintain equilibrium. If an enduring lateralization of symptoms exists in the appendages in PD, we expect axial muscles to functionally change their tonic state to compensate for these limb asymmetries.

Clinical measures correlate with torque measures in PD

Direct objective measures of axial rigidity in this study correlated with subjective clinical measures of disease severity. UPDRS motor measures of rigidity in the neck, arms and legs accounted for 50–60% of the variability in the torque measures (Fig. 5). These correlations suggest that rigidity in the extremities may also reflect the tonic state of the CNS despite having descending and dopaminergic pathways dissociable from those projecting to axial musculature. Although some axial symptoms are assessed in the motor part of the UPDRS, axial tone is directly assessed in the neck only. The present study is the first to show a direct significant correlation between the increased axial rigidity, especially in the hips, and motor symptoms as assessed by the UPDRS Part III. Interestingly, the PIGD symptoms, which predominantly reflect descending motor pathways to the axis, were not significantly correlated with axial tone. However, because our sample size was small, our power was limited. In addition to increasing sample size, comparisons between functional measures and axial rigidity would benefit from more quantifiable measures of gait and balance performance. A number of recent studies have begun to quantify axial stability during such functional tasks and have identified a relationship between increased trunk stiffness and decreased trunk angular velocities (Visser, et al., 2007) as well as finding evidence for the impact of increased axial stiffness on gluteal and paraspinal muscular responses to transient postural perturbations (Carpenter, et al., 2004). The next fruitful step will be to combine such objective measures of gait and balance with the current objective measures of axial rigidity.

Antiparkinson medication ineffective in reducing axial rigidity

There is conflicting evidence in the literature as to whether axial hypertonicity is reduced by levodopa (Bejjani, et al., 2000, Weinrich, et al., 1988). Our results show that axial tone, measured in the torsional direction, is unaffected by antiparkinson medication (Fig. 3). By measuring resistance to very low velocity twisting at both the hips and the trunk, we were able to establish that neither of these axial segments was affected by levodopa (or its equivalent dosage). Levodopa is clinically recognized to reduce limb hypertonia in PD and this has been quantified by laboratory torque and EMG measurements (Burleigh, et al., 1995, Prochazka, et al., 1997, Xia, et al., 2006), but these positive effects are generally ineffective in reducing balance or locomotor deficits (Bloem, et al., 2006). In a study of balance and gait in PD subjects, automatic postural responses to external displacements and some forms of freezing did not improve or get worse when the subjects were ON- vs. OFF-medication (Horak, et al., 1996).

Postural sway is another aspect of postural control that is not alleviated, and possibly worsened, by levodopa treatment. Specifically, an increase in sway area, especially in the mediolateral direction, was found while PD subjects were ON-medication (Rocchi, et al., 2002). Apparently, levodopa does not adequately treat all symptoms that interfere with balance and gait, and inadequacy may be because axial hypertonicity is not reduced by medication. Thus, the response of axial muscle tone to levodopa differs from that observed in the limbs, possibly because limb and axial muscle motoneurons are discretely innervated by the dorsolateral and ventromedial descending spinal pathways, respectively (Kuypers, 1964, Kuypers, 1981).

We conclude that hypertonia in the axial musculature and disorganization in the vertical and lateral distribution of axial tone might underlie functional impairments of posture and locomotion found in PD. This conclusion is supported by the observed correlation of axial rigidity with clinical measures. In PD patients, abnormally elevated and distributed axial tone might contribute to instability and lack of coordination during axial movements, such as turning-in-place, rolling and sit-to-stand tasks. The absence of a levodopa effect supports the hypothesis that axial tone is controlled by pathways distinct from those controlling tone in extremities. Future studies may focus on quantifying axial tone following interventions such as deep-brain stimulation, which has been shown to improve some aspects of functional performance (Lyons and Pahwa, 2005, Rocchi, et al., 2002, Shivitz, et al., 2006).

Table 1.

PD Subject Information

| UPDRS Motor Part III | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | H&Y | Medication | |||||||||||

| PD Sub | Sex | Duration of PD | Age | Ht | Wt | Side | ON | OFF | Rigid OFF | PIGD OFF | OFF | L-dopa | Other |

| 1 | F | 14 | 64 | 160 | 59 | L | 13 | 22 | 3 | 6 | 2.5 | 300 | Am, DA |

| 2 | F | 10 | 81 | 157 | 52.2 | L | 5 | 24 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 500 | DA, Sel |

| 3 | M | 8 | 79 | 178 | 77.1 | L | 29 | 33 | 8 | 9 | 3 | 600 | DA |

| 4 | M | 7 | 69 | 178 | 104.3 | L | 20 | 35 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 1000 | |

| 5 | F | 4 | 53 | 165 | 70.3 | L | 17 | 37 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 300 | DA |

| 6 | M | 10 | 71 | 178 | 77.1 | L | 39 | 55 | 12 | 5 | 3.5 | 1050 | |

| 7 | M | 7 | 64 | 180 | 90.7 | R | 9 | 18 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 300 | DA, AntiCh |

| 8 | M | 7 | 50 | 170 | 70.3 | R | 19 | 20 | 3 | 5 | 1.5 | 1250 | Am, DA |

| 9 | M | 7 | 51 | 178 | 68 | R | 5 | 21 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 500 | DA |

| 10 | M | 9 | 73 | 173 | 77.1 | R | 23 | 32 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 300 | DA |

| 11 | M | 18 | 59 | 173 | 74.8 | R | 36 | 50 | 8 | 12 | 3 | 500 | Am, DA |

| 12 | M | 17 | 74 | 175 | 66.7 | R | 33 | 54 | 16 | 8 | 3 | 1200 | Am, DA, Sel |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Mean | - | 9.8 | 65.7 | 172.1 | 74.0 | - | 20.7 | 33.4 | 6.3 | 5.2 | 2.5 | - | - |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Mean | Controls | 64.5 | 170.7 | 71.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

Duration of PD in years, Ht – height in cm, Wt – weight in kg, Side – side of disease onset, PIGD – Postural Instability and Gait Difficulty (UPDRS Items 27–30), Rigid – Rigidity (UPDRS Item 22), L-dopa – daily dose in mg/day, AntiCh – anti-cholinergic, Am – amantadine, DA – dopamine agonist, Sel – Selegeline

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NIH Grant NS45553 and AG006457. Thanks to Dr. Tim Cacciatore and Brian Schwab for assistance in conducting this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adkin AL, Frank JS, Jog MS. Fear of falling and postural control in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2003;18:496–502. doi: 10.1002/mds.10396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angel RW. Shortening reaction in normal and parkinsonian subjects. Neurology. 1982;32:246–251. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.3.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bejjani BP, Gervais D, Arnulf I, Papadopoulos S, Demeret S, Bonnet AM, Cornu P, Damier P, Agid Y. Axial parkinsonian symptoms can be improved: the role of levodopa and bilateral subthalamic stimulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:595–600. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.5.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergui M, Lopiano L, Paglia G, Quattrocolo G, Scarzella L, Bergamasco B. Stretch reflex of quadriceps femoris and its relation to rigidity in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 1992;86:226–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1992.tb05075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beritoff JS. On the reciprocal innervation in tonic reflexes from the labyrinths and the neck. J Physiol. 1915;49:147–156. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1915.sp001697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloem BR, Grimbergen YA, van Dijk JG, Munneke M. The “posture second” strategy: a review of wrong priorities in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2006;248:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burleigh A, Horak F, Nutt J, Frank J. Levodopa reduces muscle tone and lower extremity tremor in Parkinson’s disease. Can J Neurol Sci. 1995;22:280–285. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100039470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpenter MG, Allum JH, Honegger F, Adkin AL, Bloem BR. Postural abnormalities to multidirectional stance perturbations in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1245–1254. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.021147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erdmann WS. Geometric and inertial data of the trunk in adult males. J Biomech. 1997;30:679–688. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fornaguera J, Carey RJ, Huston JP, Schwarting RK. Behavioral asymmetries and recovery in rats with different degrees of unilateral striatal dopamine depletion. Brain Res. 1994;664:178–188. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91968-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurfinkel V, Cacciatore TW, Cordo P, Horak F, Nutt J, Skoss R. Postural muscle tone in the body axis of healthy humans. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:2678–2687. doi: 10.1152/jn.00406.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hesse WR. Teleokinetische und ereismaticsch Kräftesyseme in der Biomotorik. Helvetica Physiol Acta. 1943;1:C62–C63. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horak FB, Frank J, Nutt J. Effects of dopamine on postural control in parkinsonian subjects: scaling, set, and tone. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:2380–2396. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.6.2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs JV, Horak FB, Van Tran K, Nutt JG. An alternative clinical postural stability test for patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2006;253:1404–1413. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kempster PA, Gibb WR, Stern GM, Lees AJ. Asymmetry of substantia nigra neuronal loss in Parkinson’s disease and its relevance to the mechanism of levodopa related motor fluctuations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52:72–76. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.52.1.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar A, Mann S, Sossi V, Ruth TJ, Stoessl AJ, Schulzer M, Lee CS. [11C]DTBZ-PET correlates of levodopa responses in asymmetric Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2003;126:2648–2655. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar S. Ergonomics and biology of spinal rotation. Ergonomics. 2004;47:370–415. doi: 10.1080/0014013032000157940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar S, Panjabi MM. In vivo axial rotations and neutral zones of the thoracolumbar spine. J Spinal Disord. 1995;8:253–263. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199508040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuypers HG. The Descending Pathways to the Spinal Cord, Their Anatomy and Function. Prog Brain Res. 1964;11:178–202. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)64048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuypers HGJM. Handbook of Physiology, Sect.I: The Nervous System. II. 1981. Anatomy of the descending pathways; pp. 597–666. Motor Control, part I. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lakke JP. Axial apraxia in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 1985;69:37–46. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(85)90005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee RG. Pathophysiology of rigidity and akinesia in Parkinson’s disease. Eur Neurol. 1989;29(Suppl 1):13–18. doi: 10.1159/000116448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyons KE, Pahwa R. Long-term benefits in quality of life provided by bilateral subthalamic stimulation in patients with Parkinson disease. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:252–255. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.2.0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mak MKY, Wong ECY, Hui-Chan CWY. Quantitative measure of trunk rigidity in parkinonian patients. J Neurol. 2006:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0327-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meara RJ, Cody FW. Relationship between electromyographic activity and clinically assessed rigidity studied at the wrist joint in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 1992;115(Pt 4):1167–1180. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.4.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meara RJ, Cody FW. Stretch reflexes of individual parkinsonian patients studied during changes in clinical rigidity following medication. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1993;89:261–268. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(93)90105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagumo K, Hirayama K. [A study on truncal rigidity in parkinsonism--evaluation of diagnostic test and electrophysiological study] Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 1993;33:27–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagumo K, Hirayama K. [Axial (neck and trunk) rigidity in Parkinson’s disease, striatonigral degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy] Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 1996;36:1129–1135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis. J Spinal Disord. 1992;5:390–396. 397. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199212000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pisano F, Miscio G, Colombo R, Pinelli P. Quantitative evaluation of normal muscle tone. J Neurol Sci. 1996;135:168–172. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(95)00291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prochazka A, Bennett DJ, Stephens MJ, Patrick SK, Sears-Duru R, Roberts T, Jhamandas JH. Measurement of rigidity in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1997;12:24–32. doi: 10.1002/mds.870120106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rocchi L, Chiari L, Horak FB. Effects of deep brain stimulation and levodopa on postural sway in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:267–274. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.3.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schenkman M, Morey M, Kuchibhatla M. Spinal flexibility and balance control among community-dwelling adults with and without Parkinson’s disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M441–445. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.8.m441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherrington CS. On plastic tonus and proprioceptive reflexes. Q J Exp Physiol. 1909;2:109–156. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shivitz N, Koop MM, Fahimi J, Heit G, Bronte-Stewart HM. Bilateral subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation improves certain aspects of postural control in Parkinson’s disease, whereas medication does not. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1088–1097. doi: 10.1002/mds.20905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steiger MJ, Thompson PD, Marsden CD. Disordered axial movement in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;61:645–648. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.61.6.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takakusaki K, Oohinata-Sugimoto J, Saitoh K, Habaguchi T. Role of basal ganglia-brainstem systems in the control of postural muscle tone and locomotion. Prog Brain Res. 2004;143:231–237. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)43023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanigawa A, Komiyama A, Hasegawa O. Truncal muscle tonus in progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;64:190–196. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.64.2.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaugoyeau M, Viallet F, Aurenty R, Assaiante C, Mesure S, Massion J. Axial rotation in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:815–821. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.050666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Visser JE, Voermans NC, Nijhuis LB, van der Eijk M, Nijk R, Munneke M, Bloem BR. Quantification of trunk rotations during turning and walking in Parkinson’s disease. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:1602–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weinrich M, Koch K, Garcia F, Angel RW. Axial versus distal motor impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1988;38:540–545. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.4.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia R, Markopoulou K, Puumala SE, Rymer WZ. A comparison of the effects of imposed extension and flexion movements on Parkinsonian rigidity. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117:2302–2307. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.06.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xia R, Rymer WZ. The role of shortening reaction in mediating rigidity in Parkinson’s disease. Exp Brain Res. 2004;156:524–528. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-1919-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang T, Wei G, Yan Z, Ding M, Li C, Ding H, Xu S. Quantitative assessment of Parkinson’s disease deficits. Chin Med J (Engl) 1999;112:812–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]