Abstract

Acquired resistance is a major problem limiting the clinical benefit of endocrine therapy. To investigate the mechanisms involved, two in vitro models were developed from MCF-7 cells. Long-term culture of MCF-7 cells in estrogen deprived medium (LTED) mimics aromatase inhibition in patients. Continued exposure of MCF-7 to tamoxifen represents a model of acquired resistance to antiestrogens (TAM-R). Long-term estrogen deprivation results in sustained activation of the ERK MAP kinase and the PI3 kinase/mTOR pathways. Using a novel Ras inhibitor, farnesylthiosalicylic acid (FTS), to achieve dual inhibition of the pathways, we found that the mTOR pathway plays the primary role in mediation of proliferation of LTED cells. In contrast to the LTED model, there is no sustained activation of ERK MAPK but enhanced responsiveness to rapid stimulation induced by E2 and TAM in TAM-R cells. An increased amount of ERα formed complexes with EGFR and c-Src in TAM-R cells, which apparently resulted from extra-nuclear redistribution of ERα. Blockade of c-Src activity drove ERα back to the nucleus and reduced ERα-EGFR interaction. Prolonged blockade of c-Src activity restored sensitivity of TAM-R cells to tamoxifen. Our results suggest that different mechanisms are involved in acquired endocrine resistance and the necessity for individualized treatment of recurrent diseases.

Keywords: breast cancer, FTS, mTOR, MAP kinase, ERα, c-Src, EGFR, tamoxifen

INTRODUCTION

The estrogen receptor (ER) is expressed in approximately two thirds of breast carcinomas. Estrogen plays a crucial role in promoting growth of ER positive breast cancer cells because removal of the ovaries in premenopausal patients causes objective tumor regression. Current therapeutic strategies involve blockade of the mitogenic effect of estrogen on breast carcinoma by drugs that inhibit ER activity or reduce estrogen biosynthesis. Tamoxifen was the first agent of targeted therapy for hormone-dependent breast cancer and remains the most commonly used agent in the adjuvant setting and for treatment of advanced disease. In addition to tamoxifen, postmenopausal patients benefit from aromatase inhibitors that reduce the levels of estrogen that are critical for tumor growth. Recent clinical trials suggest that third generation aromatase inhibitors are superior to tamoxifen as first line therapy and are effective in patients with disease relapse after tamoxifen treatment [1, 2]. While patients with hormone-dependent breast cancer initially experience objective tumor regression, the disease ultimately relapses. Preclinical and clinical studies have revealed that up-regulation of growth factor signaling pathways is associated with failure of endocrine therapy and targeting the growth factor signaling pathway has become an emerging therapeutic strategy for treatment of breast cancer.

In most cases, there is no loss of ERα when resistance to endocrine therapy develops. The receptor is apparently functioning because a portion of patients with relapsing disease are responsive to secondary endocrine therapies [3, 4]. Increased ER functionality has been found in breast cancer cells that become resistant to manipulations blocking estrogen action [5, 6]. This has been largely attributed to enhanced transcriptional activity of ERα by cross-talk with up-regulated growth factor pathways [7–9]. However, the process of adaptation to endocrine therapy varies in hormone-dependent breast cancer cells and the precise mechanisms are far from fully understood.

To investigate the mechanisms underlying failure of endocrine therapy, our laboratory has established two in vitro models using MCF-7 cells. Long-term culture of MCF-7 cells in estrogen deprived medium (LTED) mimics aromatase inhibition in patients. Continued exposure of MCF-7 cells to tamoxifen represents a model of acquired resistance to antiestrogens (TAM-R). We found that MCF-7 cells react differently to these two endocrine manipulations. Here we report possible mechanisms that are involved in the process of adaptation to endocrine therapy and re-growth of hormone dependent breast cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Farnesylthiosalicylic acid (FTS) was a gift from Drs. Yoel Kloog (Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel) and Wayne Bardin (Thyreos, New York, NY). Estradiol was from Steraloids (Wilton, NH). LY 294002 and rapamycin were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). U0126 was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). c-Src kinase inhibitor PP2 was from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). EGF was obtained from Collaborative Biomedical Products (Bedford, MA). Sources of antibodies for Western analysis are as follows: phospho-MAPK monoclonal antibodies (Sigma), total MAPK (Zymed Laboratories, Inc., South San Francisco, CA), Ser473-phospho-Akt, total Akt, Thr389-phospho-p70 S6K, total p70 S6K, Ser65-phospho-PHAS-I and total PHAS-I (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), Thr229-phospho-p70 S6K (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN), EGFR sheep polyclonal antibody (06-129) (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), agarose-conjugated EGFR antibody (R1), ERα antibodies (monoclonal D-12, polyclonal HC-20 and H-184), c-Src antibodies (monoclonal and polyclonal), FAK (c-20), 5’-nucleotidase (H-300), and nuclear transport factor 2 (5E8)(Santa Cruz Biotechnology), GW182 (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA). Recombinant protein G agarose was from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). Secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ). Cell culture medium, Improved Minimum Essential Medium, Eagle's (IMEM) was from Biosource International, Inc. (Camrillo, CA). Fetal bovine serum, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/F12 (DMEM/F12), glutamine, and trypsin were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Alex Fluor 568 phalloidin and Alex Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG were bought from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Most commonly used chemicals were obtained from Sigma.

Methods

Cell culture

Wild type MCF-7 cells (kindly provided by Dr. R. Bruggemeier, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) were grown in IMEM containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). LTED cells were routinely grown in phenol red free IMEM containing 5% charcoal-dextran-stripped FBS (DCC-FBS). Tamoxifen resistant cells derived from MCF-7 cells were continuously cultured in the medium containing 10−7 M of tamoxifen. The medium for matched control cells contained 0.1% ethanol.

Growth assay

Cells were plated in 6-well plates at a density of 60,000 cells/well in their culture media. Two days later the cells were treated as described in figure legends for five days with medium change on day three. The final concentration of vehicle (ethanol or DMSO) was 0.1%. At the end of treatment, cells were rinsed twice with saline. Nuclei were prepared by sequential addition of 1 ml HEPES-MgCl2 solution (0.01 M HEPES and 1.5 mM MgCl2) and 0.1 ml ZAP solution (0.13 M ethylhexadecyldimethylammonium bromide in 3% glacial acetic acid (v/v)), and counted using a Coulter counter.

Immunoblotting

Cells grown in 60 mm dishes were washed with ice cold PBS. To each dish was added 0.5 ml lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1% Triton X 100, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 µg/ml leupeptin and aprotinin, 1 mM PMSF). After a 5-min incubation on ice, the lysates were pulse-sonicated and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min. Cell lysates were stored at −80°C until analysis. Samples (50 µg total protein) were subjected to SDS-PAGE using 10% polyacrylamide gels before proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were probed with primary antibodies in 5% BSA dissolved in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20. Secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:2,000) were then applied. After reacting with SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL), targeted protein bands were visualized by exposing the membrane to X-ray film. Bands of specific proteins were scanned and relative optical densities of bands were determined using a Molecular Dynamics scanner and ImageQuant program.

Immunoprecipitation

Cells grown in 100 mm dishes were washed with cold PBS and extracted with 1 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 25 mM NaF, 2 mM NaVO4, 5% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, aprotinin, and pepstatin). Samples were incubated on ice for 30 min, sonicated, and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants containing 1 mg total protein were incubated with antibody against the target protein at 4°C for 4 h before addition of 40 µl Protein G beads and continued incubation at 4°C overnight. The protein G beads with immunocomplex were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 sec. The supernatant was carefully removed. The beads were washed twice with 1 ml buffer II (20 mM MOPS, 2 mM EGTA, 5 mM EDTA, 25 mM NaF, 40 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 2 mM NaVO4, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, aprotinin, and pepstatin) and then boiled in 50 µl 2× Limmaeli buffer. The samples were subjected to electrophoresis in 7.5–10% SDS polyacrylamide gel and immunoblotting as described above.

Immunofluorescent microscopy

Cells grown on sterile glass cover slips in 6-well plates were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 20 min. Cells were permeabilized in cold acetone at −20°C for 2–4 minutes. After background blocking with 5% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBS for 1 h, the cells were incubated with the anti-ERα antibody (H-184) overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Alexa Fluor 546-labeled phalloidin were used for F-actin counterstaining. The cells incubated with secondary antibody only served as the control for antibody specificity. Confocal images were captured under Zeiss LSM 510 confocal Microscope using LSM Image Browser software.

Measurement of ERK1/2 MAP kinase activity

ERK1/2 MAP kinase activity was measured using the kit from Cell Signaling Technology following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, LTED cells pretreated with inhibitors were collected in lysis buffer. An aliquot of cell lysate containing 750 µg protein was immunoprecipitated with anti-phospho-ERK1/2 antibody. Kinase activity was measured by incubating immobilized ERK1/2 with Elk-1 (3 µg) at 30 C for 30 min and phospho-Elk-1 was detected by Western blot analysis.

RESULTS

We have demonstrated in previous studies that enhanced activity of growth factor pathways in LTED cells renders the cells hypersensitive to the mitogenic effect of estradiol and dual blockade of the MAPK and PI3K pathways reverses the hypersensitive phenotype [10]. We proposed that inhibition of signal transduction at a nodal point where multiple pathways converge would provide an effective strategy for treatment of breast cancer with acquired endocrine resistance. Farnesylthiosalicylic acid (FTS), a novel Ras inhibitor, was chosen to test our hypothesis because Ras acts as a signal transducer that activates both the MAPK and PI3K pathways. Indeed, FTS effectively reduced cell number of LTED cells via inhibition of proliferation as well as induction of apoptosis [11].

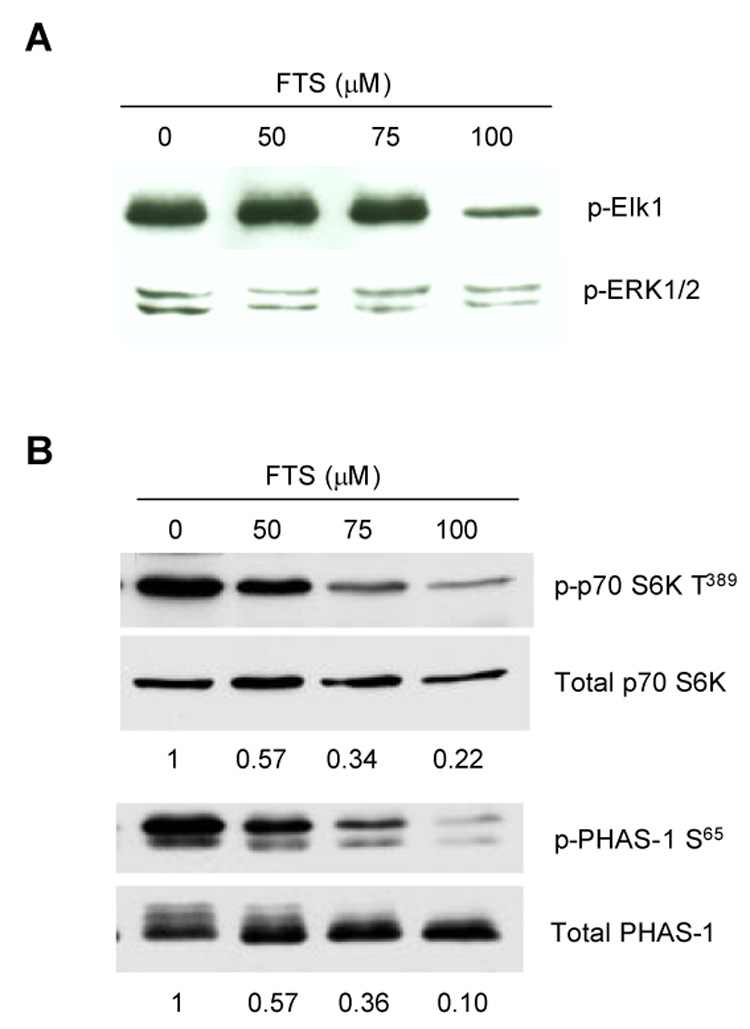

Growth inhibition of FTS correlated with inhibition of mTOR activity

To dissect out the mechanisms whereby FTS inhibits the proliferation of breast cancer cells, we first examined its effect on the MAP kinase pathway under serum containing conditions (serum is a source of endogenous growth factors). Surprisingly, FTS did not inhibit the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 MAP kinase at doses causing 50% inhibition of cell growth (i.e. 50 µM). Only higher doses of FTS (i.e. 75 µM) blocked ERK phosphorylation (data not shown). To obtain more direct evidence of MAP kinase effects, we then utilized a MAP kinase activity assay. ERK1/2 activity was measured in vitro by monitoring phosphorylation of Elk-1. Reduction of the level of phospho-Elk-1 was only seen in the cells that were exposed to 100 µM of FTS for 24 h (Fig. 1A). These results suggest that inhibition of MAP kinase activation is not the predominant mechanism for FTS-induced inhibition of proliferation of LTED cells.

Fig. 1. Effect of FTS on serum-stimulated activation of MAP kinase and mTOR.

MCF-7 and LTED cells grown in 60 mm dishes were treated with FTS for 24 h. Cells were then harvested and cell lysate prepared. (A) Activity of ERK1/2 MAP kinase was measured by incubation of immunoprecipitated ERK1/2 with Elk1 for 30 min followed by Western blot with antibody against phosphorylated Elk1. (B) Activity of mTOR was examined by Western blot analysis of phosphorylated p70 S6 kinase at Thr389 and PHAS-I at Ser65 using specific antibodies and quantitated by densitometry scanning.

In contrast to its effects on MAP kinase, FTS inhibited phosphorylations of p70 S6K (Thr389) and PHAS-1 (Ser65) in LTED cells in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 1B). Growth inhibition of FTS apparently correlated better with its inhibition on mTOR activity than on MAP kinase.

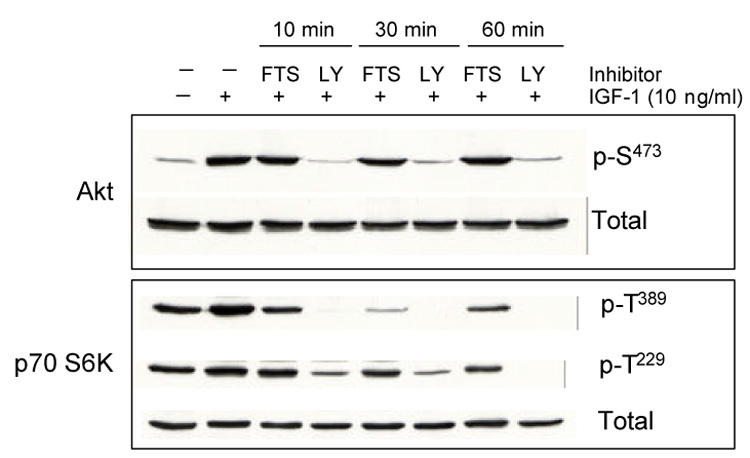

Lack of effect of FTS on PI3K

mTOR is a downstream effector of the PI3K pathway. Reduction of mTOR activity could be a result of direct inhibition of mTOR itself or an indirect inhibition of upstream molecules such as PI3K. We first examined the effect of FTS on activation of PI3 kinase by monitoring changes in phosphorylation of Akt (Ser473) stimulated by IGF-1. Pre-incubation with FTS (100 µM) did not inhibit Akt phosphorylation even with extended incubation time. In contrast, the inhibitory effect on IGF-1 induced phosphorylation of p70 S6K at Thr389 could be seen as early as 10 min (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Effect of FTS on IGF-1 induced phosphorylation of Akt (Ser473) and p70 S6K (Thr389 and Thr229).

Sub-confluent LTED cells grown in 60 mm dishes were serum starved for 24 h, pretreated with FTS (100 µM) or LY 294002 (LY, 20 µM) for 10, 30 or 60 min before addition of IGF-1 (20 ng/ml for 10 min). Cells were then harvested and cell lysate prepared. Phosphorylated and total kinases were detected by Western analysis using specific antibodies.

To further verify that inhibition of FTS on p70 S6K and PHAS-1 is not through inhibition of PI3 kinase, we examined the effect of FTS on phosphorylation of p70 S6K at Thr229, a site known to be phosphorylated by phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) [12, 13]. FTS had little, if any, effect on Thr229 phosphorylation in LTED cells treated with IGF-1 (Fig. 2). As a positive control, the known PI3K/mTOR inhibitor LY 294002 blocked IGF-1 induced phosphorylation of p70 S6K at both sites (Thr389 and Thr229) and phosphorylation of Akt as well. These findings indicate that the inhibitory effect of FTS on p70 S6K occurs at a point downstream of PI3 kinase/PDK1/Akt.

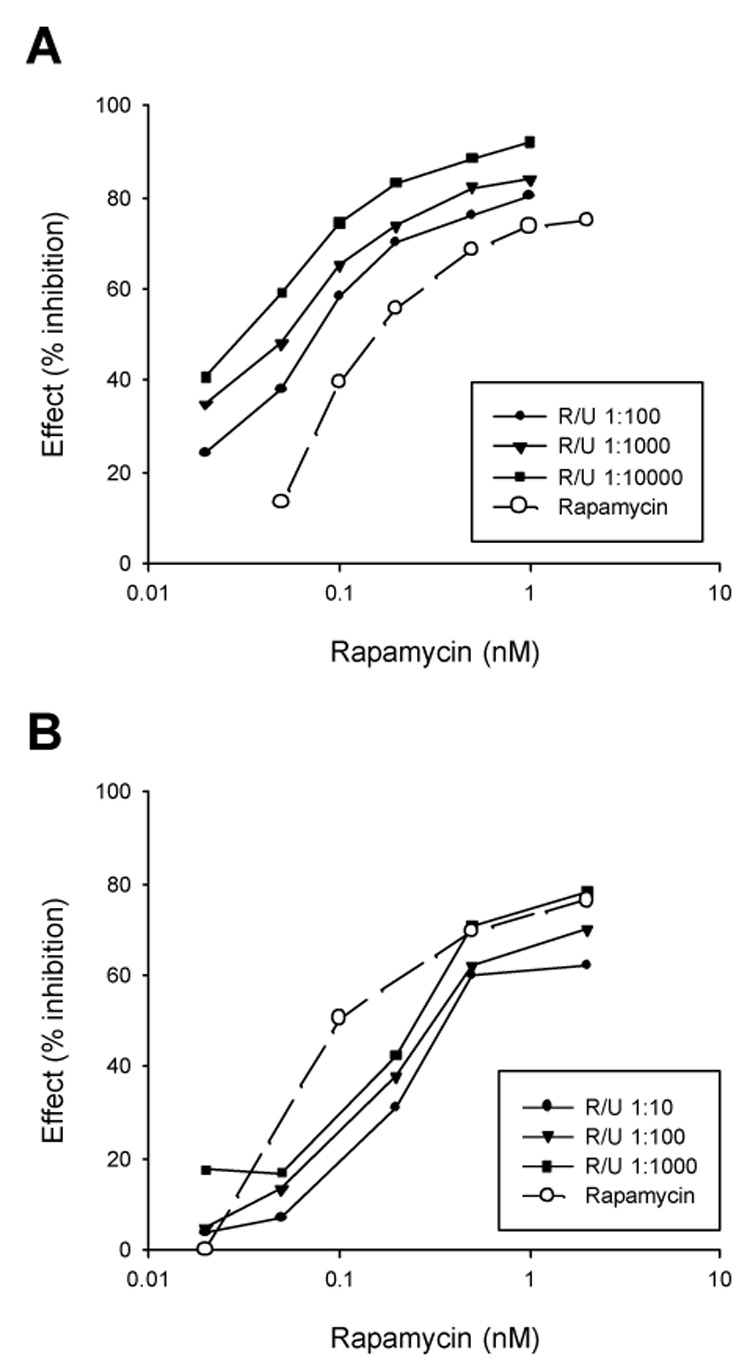

The mTOR pathway plays a predominant role in mediation of LTED cell growth

The lack of inhibition of MAPK and PI3K suggests that FTS induced growth inhibition of LTED cells is mainly due to blockade of the mTOR pathway. To determine the relative importance of the mTOR and the MAPK pathways in mediation of cell proliferation, selective inhibitors of mTOR (rapamycin) and MEK (U0126) were used. In wild type MCF-7 cells, rapamycin alone induced dose-dependent inhibition of cell growth. Addition of U0126 potentiated the inhibitory effect of rapamycin (Fig. 3A). In striking contrast, growth of LTED cells was effectively inhibited by rapamycin alone. Combination of U0126 did not show any additive effect (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that both the MAPK and mTOR pathways are important to mediate proliferation of wild type MCF-7 cells. In contrast, LTED cells relatively rely on the mTOR pathway for growth.

Fig. 3. Growth response of wild type MCF-7 cells (A) and LTED cells (B) to rapamycin alone and in combination with U0126.

Sixty thousand cells were plated into each well of 6-well plates in their culture media. Two days later, the cells were treated in triplicate wells for five days with rapamycin alone at indicated concentrations or in combination with U0126 for 5 days before counting the cell number. The results are expressed as percent inhibition.

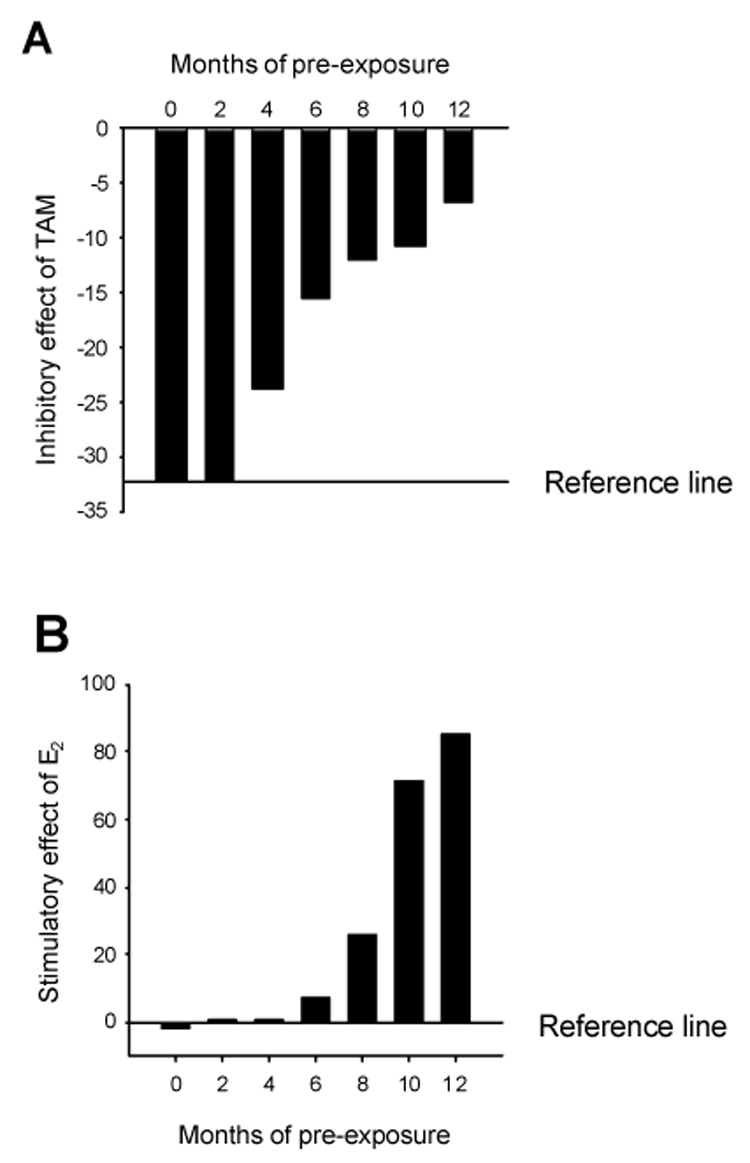

Characteristics of tamoxifen resistant model (TAM-R)

MCF-7 cells were continuously cultured in phenol-red and fetal bovine serum containing medium with 10−7 M tamoxifen. Characteristically, 5-day treatment of wild type MCF-7 cells with tamoxifen (10−7 M) in the medium containing phenol red and 5% FBS causes 30–35% reduction in cell number. The inhibitory effect of TAM was gradually diminished in the cells continuously exposed to TAM over a period of 12 months (Fig. 4A). Response of MCF-7 cells to the stimulatory effect of estradiol increased with the time of tamoxifen exposure (Fig. 4B) indicating that the cells became more sensitive to estrogen while developing resistance to tamoxifen.

Fig. 4. Altered acute responses of MCF-7 cells to tamoxifen and estradiol after long term tamoxifen exposure.

MCF-7 cells cultured for 0–12 months with 10−7 M tamoxifen (TAM) or ethanol were plated in 6-well plates at a density of 60,000 cells/well in IMEM containing 5% FBS. The cells were then treated with TAM (10−7 M) (A) or E2 (10−10 M) (B) for 5 days and cell number was counted. For TAM pre-exposed cells, tamoxifen was continuously present in the medium before the 5-day treatment with fresh medium containing either TAM or E2. The Reference line represents average response of untreated or ethanol treated MCF-7 cells under the same condition.

Activation of growth factor receptors and their downstream kinase cascades is an important mechanism involved in acquired resistance to tamoxifen [14, 15]. We monitored the basal levels of activation of ERK1/2 MAP kinase and Akt during the course of tamoxifen exposure. Differing from LTED cells, elevated MAPK phosphorylation in tamoxifen treated MCF-7 was transient and returned to the control after two months of treatment. The levels of phosphorylated Akt during tamoxifen treatment remained unchanged. Neither EGF receptor nor c-erbB2 was up-regulated in TAM-R cells (data not shown).

Non-genomic function of ERa is up-regulated in TAM-R cells

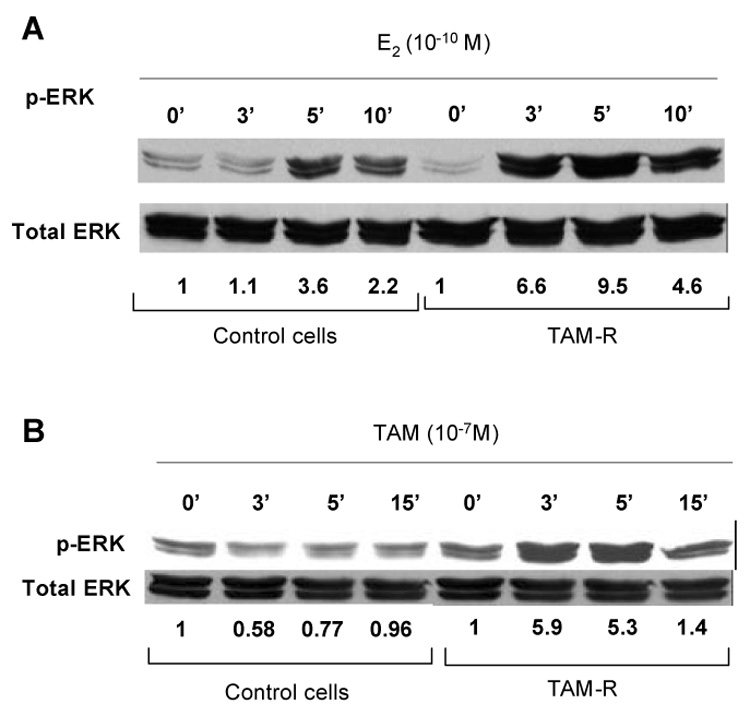

While the basal levels of phosphorylated ERK MAPK were not significantly increased, the rapid response to estradiol-stimulated activation of ERK1/2 was increased in TAM-R cells. Compared with the control cells, TAM-R cells showed an earlier and more drastic increase in the level of phosphorylated MAPK after E2 treatment (Fig. 5A). Tamoxifen (10−7 M), under this circumstance acted like an estrogen to induce phosphorylation of MAPK with peak stimulation of MAPK (more than 5 fold) occurring at 3–5 minutes. In contrast, tamoxifen showed slight inhibition on MAPK activation in matched control cells (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that the non-genomic effect of estrogen increased in TAM-R cells. In addition, tamoxifen acts as an agonist to elicit MAPK activation in TAM-R cells.

Fig. 5. Estradiol and tamoxifen induced rapid activation of ERK MAPK.

Control ells (ethanol treated) and tamoxifen resistant cells (TAM-R) were cultured for 96 h in phenol red-free medium containing 1% DCC-FBS and then incubated with E2 (A) or tamoxifen (B) for various time before preparation of cell lysates and Western blot analysis. The numbers shown under the bands of phospho-MAPK are fold changes of phospho-MAPK normalized by total MAPK. Results shown in this figure are representative of three repeatable experiments.

Re-distribution of ERα facilitates its interaction with EGFR in TAM-R cells

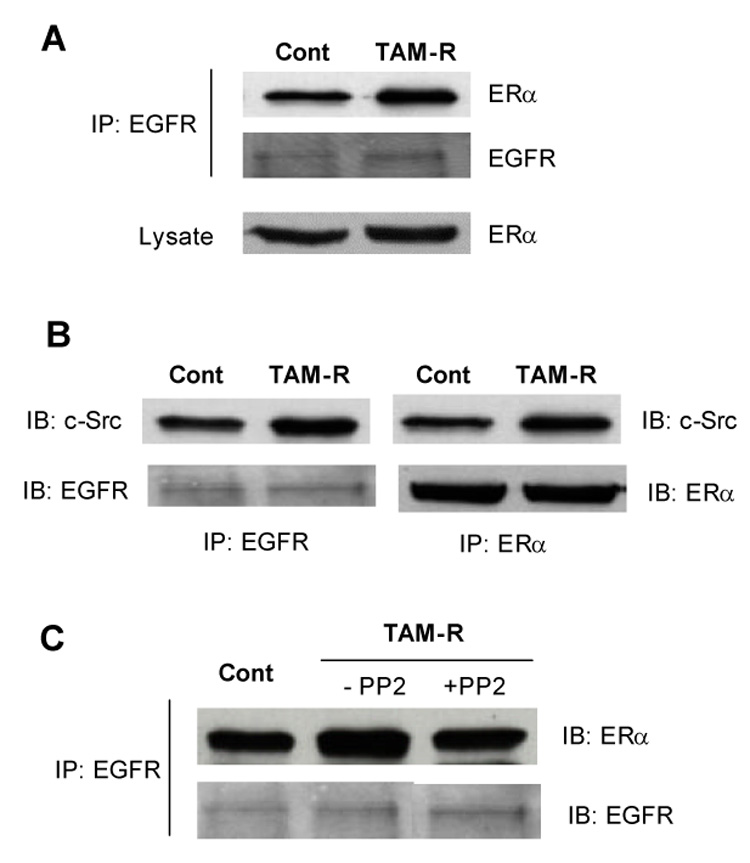

Estradiol elicits rapid activation of MAP kinase via extra-nuclear ERα in a variety of cell types [16–19]. This effect requires participation of growth factor receptors and other adaptor proteins[20–23]. In the cells treated with TAM for four months or longer a significantly increased amount of ERα was co-immunoprecipited with EGFR even though there was no change in the levels of these receptors compared with the control cells that had been treated with ethanol (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6. Kinase active c-Src facilitates ERα-EGFR interaction in TAM-R cells.

(A) Cell lysates were prepared from TAM-R cells and matched controls that had been exposed to TAM or ethanol for more than four months. Interaction between EGF receptor and ERα was examined by immunoprecipitation with antibody against EGFR followed by immunoblotting for ERα. (B) Co-immunoprecipitaion of c-Src by antibodies against EGFR and ERα. (C) TAM-R cells were treated with or without PP2 (5 µM) for 48 h before preparation of cell lysate. ERα-EGFR interaction was examined as mentioned above.

To determine whether enhanced interaction between EGFR and ERα required an adaptor protein, several candidate proteins were examined by immunoblots following immunoprecipitation with antibodies against EGFR or ERα. We found that c-Src rather than other adaptors was increased in the complex precipitated with EFGR and ERα in TAM-R cells (Fig. 6B). Kinase activity of c-Src is required for the complex formation since inhibition of c-Src kinase with PP2 reduced the interaction of ERα with EGFR (Fig. 6C).

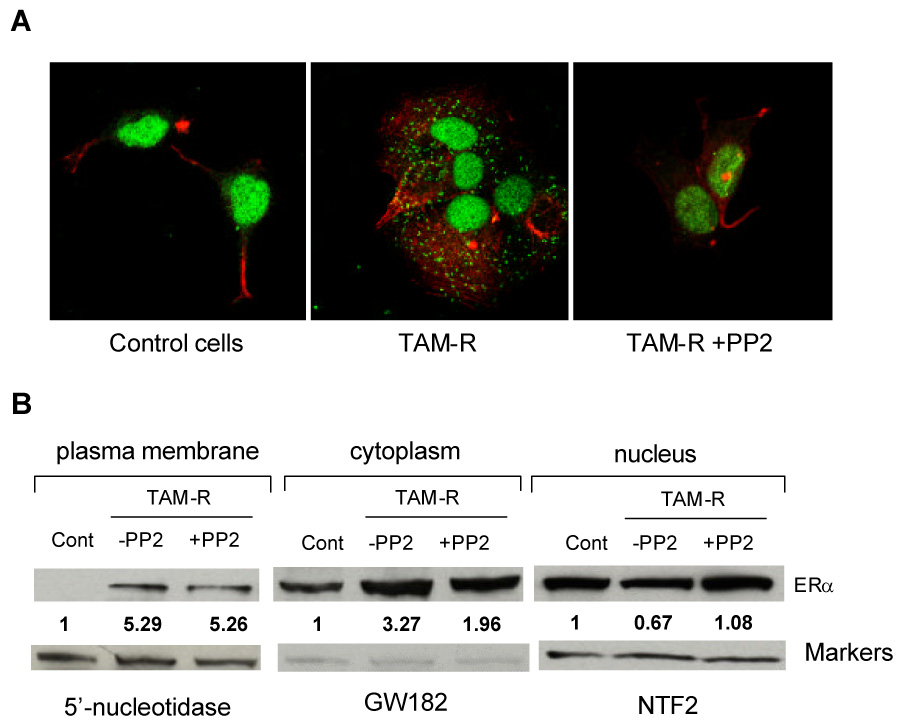

As observed in other tamoxifen resistant cell lines, there was no significant change in the amount of ERα expression in TAM-R cells. Therefore, increased interaction between ERα and EGFR must result from altered distribution of ERα. Immunofluorescent images using confocal microscopy showed that ERα (green staining) was predominantly located in the nucleus in control cells (ethanol treated). Compared to ethanol treated cells, TAM-R cells were larger with more spread cytoplasm. Green fluorescence was no longer restricted to the nucleus. Bright green spots were scattered throughout the cytoplasm and on the cell borders (Fig. 7A). Increased extra-nuclear distribution of ERα was confirmed by western blot analysis of the protein from cellular fractions (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, treatment of TAM-R cells with the c-Src inhibitor, PP2, for 48 hours promoted translocation of ERα from the cytoplasm back to the nucleus. As shown in Fig. 7A, green fluorescence (ERα staining) was concentrated in nuclei in TAM-R cells treated with PP2. Similarly, the levels of ERα in the membrane and cytoplasm fractions were reduced and the level of nuclear ERα was increased by PP2 in TAM-R cells (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7. Altered subcellular distribution of ERα in TAM-R cells.

(A) Cells cultured on coverslips for 2 days were fixed and incubated with anti-ERα antibody overnight at 4°C. After thorough wash with PBS, the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 labeled secondary antibody (green) for 1 h. Actin was stained with Alexa Fluor 546 labeled phalloidin (red). Confocal images were captured under Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (40× objective). (B) Protein levels of ERα in subcellular fractions. Nuclei, cytoplasm, and plasma membrane were isolated as described in Material and Methods. An equal amount of proteins from different fractions was subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and Western blot analysis for ERα. 5’-Nucleotidase (5′NT), GW182, and nuclear transport factor 2 (NTF2) were used as markers for plasma membrane, cytosol, and nucleus, respectively. Numbers under the ERα bands represent fold changes of ERα normalized by the marker of each fraction. PP2 treatment: 5 µM, 48 hours.

Blockade of c-Src activity restores tamoxifen sensitivity

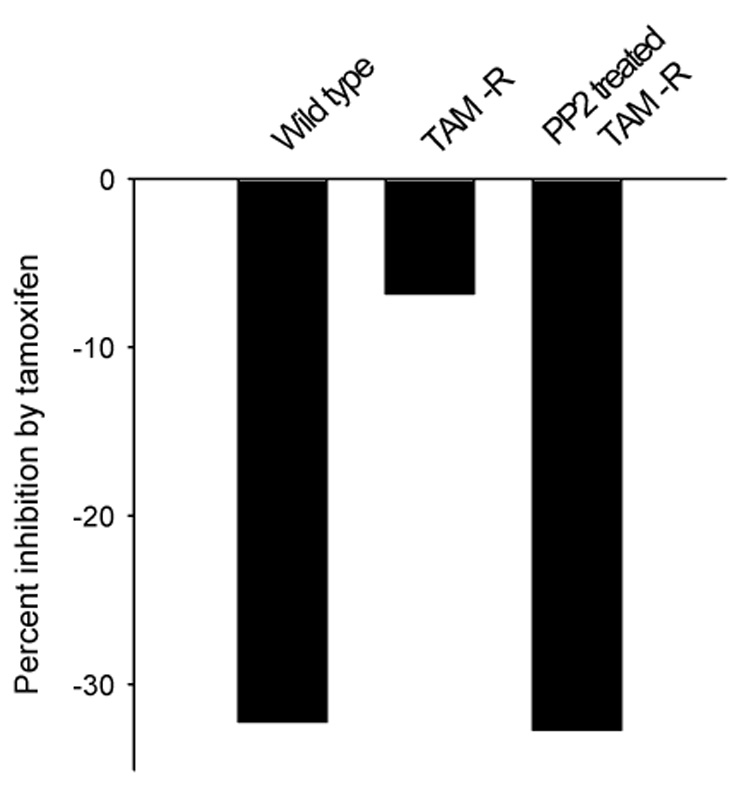

The above results suggest that kinase active c-Src is a key element to retain ERα in extra-nuclear sites and to form complexes with EGFR. Up-regulation of the extra-nuclear signaling of ERα with the aid of c-Src and EGFR allows MCF-7 cells to escape tamoxifen inhibition. To test this hypothesis, we treated TAM-R cells with PP2 for eight months and examined growth response of these cells to acute treatment with tamoxifen. As shown in Fig. 8, PP2 treatment completely restored cellular sensitivity to tamoxifen.

Fig. 8. Growth responses of wild type MCF-7 cells, TAM-R cells, and PP2 treated TAM-R cells to acute treatment of tamoxifen.

PP2 (5 µM) treatment lasted for eight months. Cell numbers were counted as described in the Materials and Methods. The result was expressed as percent reduction compared with the vehicle control of each cell type.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated that different mechanisms are involved when breast cancer cells adapt themselves to escape from the manipulations blocking the estrogen receptor signaling. Long term estrogen deprivation results in sustained activation of both the MAPK and the mTOR pathways in MCF-7 cells. Using FTS as a tool, we found that the mTOR pathway is a predominant pathway in mediation of proliferation of LTED cells. The specific mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin, effectively inhibited growth of LTED cells. Simultaneous blockade of ERK MAP kinase and mTOR with rapamycin did not produce synergistic inhibition. While transient increases in MAP kinase activation was observed for three months in tamoxifen resistant MCF-7 cells, the levels returned to basal thereafter. These cells are more sensitive to E2 and EGF to stimulate MAPK activation. Long term treatment with tamoxifen caused extra-nuclear distribution of ERα and enhanced interaction between ERα and EGF receptor. Kinase active c-Src is required for extra-nuclear localization of ERα and formation of ERα-EGFR complex. Blockade of c-Src activity with PP2 can restore the sensitivity of TAMR cells to the growth inhibition of tamoxifen.

We have shown that long-term estrogen deprivation causes enhanced sensitivity to the mitogenic effect of estradiol in MCF-7 cells, which is associated with up-regulation of the MAPK and the PI3K pathways [10, 24, 25]. It was reasoned that dual blockade of these two pathways at a nodal point would be an effective means to inhibit proliferation of LTED cells. We have chosen to use a novel Ras inhibitor, FTS, because Ras transmits the mitogenic signals through both the MAPK and the PI3K pathways. FTS inhibits growth of LTED cells via inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis [11]. However, growth inhibition by FTS correlated much better with its blockade of phosphorylation of p70 S6K and PHAS-I, two downstream effectors of mTOR than with the inhibition of phosphorylation of ERK1/2.

The PI3K/Akt pathway is upstream of mTOR and can be activated directly by growth factor receptors or indirectly via Ras. Therefore, reduction of mTOR activity induced by FTS could be a result of PI3K inhibition. By examining phosphorylation of Akt at serine 473, we found that the inhibitory effect of FTS on Akt phosphorylation was negligible compared with mTOR inhibition. Additionally, FTS did not inhibit phosphorylation of p70 S6K at Thr229, a phosphorylation site activated by PDK1, a downstream kinase PI3 kinase [13]. Both Akt and p70 S6K Thr229 phosphorylations were effectively inhibited by LY 294002 the known inhibitor of PI3K. These results provide additional evidence that FTS acts downstream of PI3K/PDK1/Akt to block mTOR signal transduction. Using separate model systems we have demonstrated that FTS inhibits mTOR activity through a unique ability to dissociate mTOR from its binding partner, RAPTOR [26].

To further dissect out the relative importance of the MAPK and the mTOR pathways in mediation of cell proliferation, the effect of specific inhibitors to MEK (U0126) and mTOR (rapamycin) used separately or in combination was examined. Both wild type and LTED cells were inhibited by single treatment with U0126 or rapamycin. Their responses to combined treatment were strikingly different. Addition of U0126 increased the efficacy and potency of rapamycin in wild type MCF-7 cells. In contrast, the inhibitory effect of rapamycin was not increased at all by U0126 in LTED cells. These results suggest that LTED cells are more dependent upon the mTOR pathway for proliferation whereas MCF-7 cells rely on both pathways.

Recent discoveries indicate the ERK pathway [27] can activate mTOR. Tuberin (TSC2) is the molecule linking these two pathways. TSC2 inhibits mTOR via reduction of GTP-Rheb [28]. Phosphorylation of TSC2 by ERK MAPK inactivates TSC2 and results in activation of mTOR [29]. Sustained activation of ERK MAPK in LTED cells may have contributed to up-regulation of mTOR activity. Our results suggest that the mitogenic signals from two pathways converge at mTOR in LTED cells because blockade of MAP kinase in addition to mTOR does not result in additive effects. The redundancy of the signal transduction network due to interactions between estrogen receptor and growth factors and among growth factor pathways implies that targeting a downstream molecule might be a useful strategy for treatment of breast cancer relapsed from endocrine therapy.

The signal transduction profile of tamoxifen resistant MCF-7 cells is different from that of LTED cells. The hallmark of cross talk between the ER and growth factor pathways in TAM-R cells is enhanced ERα-EGFR interaction without increases in expression of these receptors. One significant change after long-term tamoxifen exposure is translocation of ERα to the cytoplasm. This phenomenon is due to tamoxifen treatment rather than alteration in ERα expression because it does not occur in the same cell line under estrogen deprived condition (LTED). Elevation in the levels of extra-nuclear ERα increases the opportunity to associate with factors that facilitates activation of the MAP kinase pathway via non-genomic mechanism. Indeed, TAM-R cells displayed enhanced sensitivity to E2 to stimulate MAPK activation.

Interaction of ERα with EGFR requires adaptor proteins. A number of proteins, such as c-Src, FAK, MNAR [23] and striatin [30] are reported to form complex with estrogen receptors and to be involved in extra-nuclear function of ERs. In TAM-R cells, an increased amount of c-Src was recovered from the complex of EGFR and ERα. The amount of other adaptor proteins co-immunoprecipited with EGFR or ERα was unchanged or slightly reduced [31]. These data suggest that one role of kinase active c-Src in TAM-R cells is to retain ERα in the cytoplasm. The precise molecular mechanism to explain how relocalization of ERα occurs in TAM-R cells is unclear at the present time. The fact that PP2 treatment reduced the levels of cytoplasmic ERα implies that c-Src may also be involved in a dynamic process of ERα translocation. Further studies are needed to investigate in detail the mechanisms mediating this process.

c-Src, a non-receptor tyrosine kinase, mediates signal transduction pathways that regulate proliferation, survival, cell adhesion and migration [32]. c-Src can be activated by many cell surface receptors. Several lines of evidence indicate that c-Src is involved in extra-nuclear signaling of ERα [33, 34]. Mammary epithelial cells derived from c-Src-null mice exhibit delayed MAP kinase activation in response to exogenous estradiol [35]. Increased c-Src activity could modulate ERα function and promote agonist action of tamoxifen [36, 37]. Up-regulation of c-Src activity was reported in tamoxifen resistant breast cancer cells [38]. Our results indicate that c-Src plays a critical role in development of tamoxifen resistance. Blockade of c-Src activity in TAM-R cells led to nuclear distribution of ERα, reduced ERα-EGFR interaction, and inhibition of E2-induced MAPK activation. Prolonged treatment of TAM-R cells with c-Src inhibitor could completely restore the sensitivity to tamoxifen for growth inhibition. Synergistic interaction of EGFR, ERα, and c-Src enhances the responsiveness of MCF-7 breast cancer cells to the mitogenic stimulation of EGF and E2, which allows the cells to survive and proliferate in the presence of tamoxifen.

Preclinical studies from our laboratory and others suggest that various mechanisms can be used by hormone-dependent breast cancer cells to adapt themselves to different endocrine therapy. Redundancy and cross talk of growth factor signaling pathways increase the complexity of target identification. The results from LTED model suggest that mTOR converges mitogenic signals from several pathways and it may be a good candidate for targeted therapy of relapsed disease. Our tamoxifen resistance model reveals an important role of c-Src in development of tamoxifen resistance. Interfering with c-Src activity might be a feasible way to prevent or delay tamoxifen resistance. Our studies indicate that individualized regimen is necessary for the treatment of recurrent breast cancer after endocrine therapy.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: E2, estradiol; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; FTS, farnesylthiosalicylic acid; LTED, long term estrogen deprivation; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; p70 S6K, p70 S6 kinase; PHAS-I, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein 1; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase; TAM, tamoxifen.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baum M, Budzar AU, Cuzick J, Forbes J, Houghton JH, Klijn JG, Sahmoud T, Group AT. Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: first results of the ATAC randomized trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2131–2139. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, Robert NJ, Muss HB, Piccart MJ, Castiglione M, Tu D, Shepherd LE, Pritchard KI, Livingston RB, Davidson NE, Norton L, Perez EA, Abrama JS, Therasse P, Palmer MJ, Pater JL. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:1793–1802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Encarnacion CA, Ciocca DR, McGuire WL, Clark GM, Fuqua SAW, Osborne CK. Measurement of steroid hormone receptors in breast cancer patients on tamoxifen. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 1993;26:237–246. doi: 10.1007/BF00665801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunner N, Frandesen TL, Holst-Hansen C, Bei M, Thompson EW, Wakeling AE, Lippman ME, Clarke R. MCF7/LCC2: a 4-hydroxytamoxifen resistant human breast cancer variant that retains sensitivity to the steroidal antiestrogen ICI 182,780. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3229–3232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Long B, McKibben BM, Lynch M, van den Berg HW. Changes in epidermal growth factor receptor expression and response to ligand associated with acquired tamoxifen resistance or oestrogen independence in the ZR-75-1 human breast cancer cell line. Br. J. Cancer. 1992;65:865–869. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholson RI, Gee JMW. Oestrogen and growth factor cross-talk and endocrine insensitivity and acquired resistance in breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2000;82:501–513. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joel P, Smith J, Sturgill T, Blenis J, Lannigan D. pp90rsk1 regulates estrogen receptor-mediated transcription through phosphorylation of Ser-167. Molecular & Cellular Biology. 1998;18:1978–1984. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gee JM, Robertson JF, Gutteridge E, Ellis IO, Pinder SE, Rubini M, Nicholson RI. Epidermal growth factor receptor/HER2/insulin-like growth factor receptor signalling and oestrogen receptor activity in clinical breast cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2005;12:S99–S111. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shou J, Massarweh S, Osborne CK, Wakeling AE, Ali S, Weiss H, Schiff R. Mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance: increased estrogen receptor-HER2/neu cross-talk in ER/HER2-positive breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2004;96:926–935. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yue W, Wang J-P, Conaway MR, Li Y, Santen RJ. Adaptive hypersensitivity following long-term estrogen deprivation: involvement of multiple signal pathways. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003;86:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yue W, Wang J-P, Li Y-B, Fan P, Santen RJ. Farnesylthiosalicylic acid blocks mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in breast cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2005;117:746–754. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alessi DR, Kozlowski MT, Weng QP, Morrice N, Avruch J. 3-Phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1) phosphorylates and activates the p70 S6 kinase in vivo and in vitro. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pullen N, Dennis PB, Andjelkovic M, Dufner A, Kozma SC, Hemmings BA, Thomas G. Phosphorylation and activation of p70s6k by PDK1. Science. 1998;279:707–710. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5351.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donovan CH, Milic A, Slingerland JM. Constitutive MEK/MAPK activation leads to p27Kip1 deregulation and antiestrogen resistance in human breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:40888–40895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106448200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gee JMW, Robertson JFR, Ellis IO, Nicholson RI. Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 mitogen activated protein kinase is associated with poor response to anti-hormonal therapy and decreased patient survival in clinical breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2001;95:247–254. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010720)95:4<247::aid-ijc1042>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Migliaccio A, Di Domenico M, Castoria G, de Falco A, Bontempo P, Nola E, Auricchio F. Tyrosine kinase/p21ras/MAP-kinase pathway activation by estradiol-receptor complex in MCF-7 cells. EMBO J. 1996;15:1292–1300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Z, Yuhanna IS, Galcheva-Gargova Z, Karas RH, Mendelsohn ME, Shaul PW. Estrogen receptor α mediates the nongenomic activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by estrogen. J. Clin. Inv. 1999;103:401–406. doi: 10.1172/JCI5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endoh H, Sasaki H, Maruyama K, Takeyama K, Waga I, Shimizu T, Kato S, Kawashima H. Rapid activation of MAP kinase by estrogen in the bone cell line. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;235:99–102. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watters JJ, Campbell JS, Cunningham MJ, Krebs EG, Dorsa DM. Rapid membrane effects of steroids in neuroblastoma cells: effects of estrogen on mitogen activated protein kinase signaling cascade and c-fos immediate early gene transcription. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4030–4033. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.9.5489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Razandi M, Pedram A, Park ST, Levin ER. Proximal events in signaling by plasma membrane estrogen receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:2701–2712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205692200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song RX, Barnes CJ, Zhang Z, Bao Y, Kumar R, Santen RJ. The role of Shc and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor in mediating the translocation of estrogen receptor alpha to the plasma membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:2076–2081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308334100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song RXD, McPherson RA, Adam L, Bao Y, Shupnik M, Kumar R, Santen RJ. Linkage of rapid estrogen action to MAPK activation by ERα-Shc association and Shc pathway activation. Mol. Endocrinol. 2002;16:116–127. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.1.0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong CW, McNally C, Nickbarg E, Komm BS, Cheskis BJ. Estrogen receptor-interacting protein that modulates its nongenomic activity-crosstalk with Src/Erk phosphorylation cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:14783–14788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192569699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24.Masamura S, Santner SJ, Heitjan DF, Santen RJ. Estrogen deprivation causes estradiol hypersensitivity in human breast cancer cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995;80:2918–2925. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.10.7559875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yue W, Wang J-P, Conaway M, Masamura S, Li Y, Santen RJ. Activation of the MAPK pathway enhances sensitivity of MCF-7 breast cancer cells to the mitogenic effect of estradiol. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3221–3229. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMahon LP, Yue W, Santen RJ, Lawrence JCJ. Farnesylthiosalicylic acid inhibits mTOR activity both in cells and in vitro by promoting dissociation of the mTOR-raptor complex. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005;19:175–183. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signaling controls tumor cells growth. Nature. 2006;441:424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature04869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan K-L. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nature Cell Biol. 2002;4:648–657. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma L, Chen Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Pandolfi PP. Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk: implications for tuberous sclerosis and cancer pathogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levin ER. Integration of the extranuclear and nuclear actions of estrogen. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005;19:1951–1959. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan P, Wang J-P, Santen RJ, Yue W. Long term treatment with tamoxifen facilitates translocation of ERα out of the nucleus and enhances its interaction with epidermal growth factor receptor in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1020. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas SM, Brugge JS. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Migliaccio A, Castoria G, Domenico DI, De Falco A, Bilancio A, Auricchio F. Src is an initial target of sex steroid hormone action. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2002;963:185–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cato AC, Nestl A, Mink S. Rapid actions of steroid receptors in cellular signaling pathways. Sci. STKE. 2002;2002:RE9. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.138.re9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim H, Laing M, Muller W. c-Src-null mice exhibit defects in normal mammary gland development and ER signaling. Oncogene. 2005;24:5629–5636. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng W, Webb P, Nguyen P, Liu X, Li J, Karin M, Kushner PJ. Pontentiation of estrogen receptor activation function 1 (AF-1) by Src/JNK through a serine 118-independent pathway. Mol. Endocrinol. 2001;15:32–45. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.1.0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah YM, Rowan BG. The Src kinase pathway promotes tamoxifen agonist action in Ishikawa endometrial cells through phorphorylation-dependent stabilization of estrogen receptor a promoter interaction and elevated steroid receptor coactivator 1 activity. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005;19:732–748. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Planas-Silva MD, Bruggeman RD, Grenko RT, Smith JS. Role of c-Src and focal adhesion kinase in progression and metastasis of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;341:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]