Abstract

Over the course of the past century, flies in the family Drosophilidae have been important models for understanding genetic, developmental, cellular, ecological, and evolutionary processes. Full genome sequences from a total of 12 species promise to extend this work by facilitating comparative studies of gene expression, of molecules such as proteins, of developmental mechanisms, and of ecological adaptation. Here we review basic biological and ecological information of the species whose genomes have recently been completely sequenced in the context of current research.

IF most biologists were given one wish to facilitate their research, many would opt for the fully sequenced genome of their focal taxon. Others might ask for a diverse array of genetic tools around which they could design experiments to answer evolutionary, developmental, behavioral, or ecological questions. With the recent completion of full genome sequences from 12 species, Drosophila biologists are now in an unprecedented situation: they have both wishes—and more. Not only does the Drosophila model afford researchers full genome sequences and cutting-edge genetic tools, but also more is known about nearly every aspect of the biologies (genetics, development, ecology, phylogenetic relationships, and life history) of these species than of any other eukaryote. Furthermore, because of the comparative genomic framework of the 12 species, discoveries made in one taxon can immediately be placed in a larger evolutionary context.

While most researchers are well aware of the utility of Drosophila melanogaster and its close relatives to studies of genetics and developmental biology, few realize that several of the remaining species in this genus have been studied by ecologists and evolutionary biologists nearly since the time that Morgan picked up his first bottle of flies. For example, D. pseudoobscura, described by Frolova and Astaurov (1929), is well known from the classic evolutionary studies of Dobzhansky, his colleagues, and their students (Anderson et al. 1991; Popadic and Anderson 1994). D. virilis, in addition to being a genetic model system in its own right, has also been used to study speciation and chromosome evolution (McAllister 2002; Caletka and McAllister 2004).

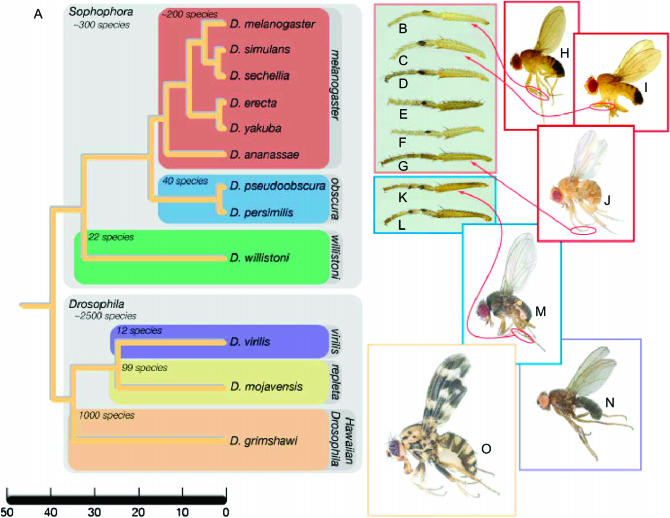

The genus Drosophila contains >2000 described species (Markow and O'Grady 2005, 2006), as well as several hundred taxa that await description. Most of these taxa belong to one of two major subgenera: Sophophora and Drosophila. Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic relationships and divergence times of the 12 species for which whole-genome sequences are now available. The 12 species with sequenced genomes represent a gradient of evolutionary distances from D. melanogaster, including taxa diverging within the past 1 million years to those species who last shared a common ancestor with D. melanogaster >30 million years ago (Figure 1). This range was selected to take advantage of the power of multiple, related genomes to discover conserved regulatory motifs, enhance gene prediction, and improve annotation of the D. melanogaster genome (Bergman et al. 2003; Boffelli et al. 2003). Eight of the newly sequenced species are closely related to D. melanogaster and belong to the subgenus Sophophora. Five of these, D. simulans, D. yakuba, D. erecta, D. sechellia, and D. ananassae, are included in the melanogaster species group; 2, D. pseudoobscura and D. persimilis, are placed in the obscura group, sister to the melanogaster species group; and another, D. willistoni, is in the willistoni group, a basal clade within Sophophora (O'Grady and Kidwell 2002). The remaining 3 species belong to the subgenus Drosophila, the sister taxon of Sophophora. D. virilis, a sap flux breeding species, and D. mojavensis, a cactophilic taxon, belong to what is referred to as the virilis–repleta radiation (Throckmorton 1975). D. grimshawi, a large, spectacularly patterned species, represents the Hawaiian Drosophila radiation, a closely related clade to the virilis–repleta species.

Figure 1.—

(A) Phylogenetic relationships of the 12 fully sequenced Drosophila species, along with a timescale for evolution in this group (after Russo et al. 1995). Species-level diversity in the containing subgenera and species groups are shown (Markow and O'Grady 2005a and references therein). (B–G) Sex combs in the melanogaster species group: (B) D. melanogaster, (C) D. simulans, (D) D. sechellia, (E) D. erecta, (F) D. yakuba, and (G) D. ananassae. (H) Adult male, D. melanogaster. (I) Adult male, D. simulans. (J) Adult female, D. ananassae. (K and L) Sex combs in the obscura species group: (K) D. pseudoobscura and (L) D. persimilis. (M) Adult male, D. pseudoobscura. (N) Adult male, D. virilis. (O) Adult male, D. grimshawi.

Selection of the species to be sequenced thus was based on two criteria: (1) their degree of relatedness to D. melanogaster and (2) the likelihood of discovering new genes and new pathways. In the case of the first criterion, it was important to densely sample species closely related to D. melanogaster as well as successively more distantly related taxa to discover and annotate conserved regulatory regions via phylogenetic shadowing (e.g., Boffelli et al. 2003). The dense sampling within the melanogaster subgroup (simulans, sechellia, and yakuba) and inclusion of the more distantly related D. erecta and D. ananassae has yielded a much more detailed picture of the cis-regulatory regions than comparisons between melanogaster and obscura (Moses et al. 2006; Pollard et al. 2006). Some of the species were selected because they are behaviorally and ecologically diverse and would yield either novel biochemical pathways or unique variations on already known networks of gene interaction. This avenue has proved particularly relevant for the evolution of the olfactory and gustatory receptor genes in D. sechellia, a taxon that oviposits only in the rotting fruit of Morinda citrifolia, a highly toxic substrate (McBride 2007). Another taxon selected on the basis of this criterion is the cactophilic species D. mojavensis, in which novel genes appear to be associated with the use of toxic cactus hosts (Matzkin et al. 2006) as well as with their mating system (Kelleher and Markow 2007).

The first Drosophila species, funebris, was described by J. C. Fabricius in 1787 and moved into the genus Drosophila by C. F. Fallen in 1823. Meigen described D. melanogaster in 1830 (Meigen 1830). The number of species described in this group rose slowly throughout the latter half of the 19th century. It was not until the early 1900s, however, after D. melanogaster was established as a model organism for understanding genetics that the rate of Drosophila species descriptions increased dramatically. Alfred H. Sturtevant, in addition to his contributions to Drosophila genetics, also produced early taxonomic treatments of Drosophila (Sturtevant 1916, 1919, 1921, 1939, 1942) and described species such as D. simulans, D. willistoni, and D. virilis. In the late 1930s Th. Dobzhansky began to use D. pseudoobscura and its sibling species, D. persimilis and D. miranda, in studies aimed at understanding the population genetic basis of species formation. Also around this time, extensive collections by J. T. Patterson and W. S. Stone's group at the University of Texas (Austin, TX) discovered hundreds of new species, mainly from the southwestern United States, Mexico, and Central and South America (Patterson 1943; Patterson and Mainland 1944). Subsequent efforts in Hawaii during the 1960s and the 1970s, the result of a collaboration between the University of Texas group and D. Elmo Hardy at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, discovered an immensely important radiation of Drosophila that numbers close to 1000 species (Spieth 1981). This work led to the popularization of several species as model systems for ecological, population, and behavioral genetics (Kambysellis 1968; Carson 1992; DeSalle 1992). Other groups, including those led by Lachaise, Tsacas, David, and Bock, worked throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s describing many taxa in Africa, Australia, and the South Pacific (Bock and Parsons 1981; Okada 1981; Tsacas et al. 1981).

For many problems there is an animal on which it can be most conveniently studied. August Krogh

According to the Krogh principle, for all biological phenomena there is a perfect model system that can be used to formulate questions and test hypotheses. For example, D. melanogaster, popularized by T. H. Morgan and his students in the first half of the 20th century, is one of the premier model systems of modern genetics. Investigations into the ecologies, life histories, and genome features of the 12 fully sequenced species of Drosophila demonstrate that each of these flies can be viewed as a model system to address specific biological questions.

In spite of all the work that has been done, what do we really know about the biology and ecology of these 12 species? What makes them compelling models to study interesting questions? What biological questions are each uniquely suited to address? The facility of rearing and manipulating so many diverse but related species of Drosophila has fueled the expansion of experimental studies. Several recent reports have reviewed the wealth of research that has been done using Drosophila (Powell 1997; Markow and O'Grady 2005, 2006; Ashburner et al. 2006). Here, we discuss several areas where the combination of full genome sequences and comparative life history data may help redefine ecological and evolutionary studies.

Distributions and ecological associations:

Choices about where to feed and oviposit are critical to the survival and fitness of all Drosophila species. However, the genetic pathways involved in host plant selection are largely unknown, as are the determinants that make some species specialists and others generalists. In spite of our current lack of understanding about these genes and how they might interact with the environment, they are of great interest to evolutionary biologists as they may be involved in driving the process of diversification at both the micro- and macroevolutionary levels. Related to host selection and selectivity are those factors (environmental, behavioral, population genetic, and otherwise) that allow some taxa to exist as widespread or cosmopolitan species, while the ranges of others are very narrowly defined. Range maps for Drosophila species are given in Markow and O'Grady (2005, 2006). Some species are known to be constrained by host plant distribution and geographic factors, but the ranges, or the bases for the ranges, of others are less well understood.

The 12 species with sequenced genomes display a great diversity in both geographic distribution and ecological association. Some species, such as D. melanogaster and D. simulans, are cosmopolitan and have spread beyond their ancestral distributions as a result of their commensal association with humans and their ability to breed in a wide variety of rotting fruits. Some close relatives of these generalist species also oviposit in fruit, but are more narrowly distributed and highly selective in their choice of substrate. For example, D. sechellia is endemic to the Seychelles and has specialized on the fruits of M. citrifolia, a resource toxic to other Drosophila (R'Kha et al. 1991). Another case of specialization occurs with D. erecta, which breeds in species of Pandanus in the Ivory Coast of western Africa (Lachaise and Tsacas 1983). D. yakuba, also restricted to Africa, is a generalist fruit breeder (Lachaise and Tsacas 1983), but has not become a cosmopolitan species like D. melanogaster and D. simulans. D. ananassae, another fruit breeding species that is widespread throughout Asia and the Pacific, is used extensively by some researchers as a genetic model (Tobari 1992). This species has spread beyond its initial distribution through its association with humans and the fruit trade and is now considered subcosmopolitan (Singh 2000).

The sibling species pair of D. pseudoobscura and D. persimilis is mainly distributed in western North America, although a small population of D. pseudoobscura is located in the mountains near Bogotá, Colombia (Dobzhansky et al. 1963). During the summer months, both species are abundant in mid- to high-elevation forests, especially those dominated by Ponderosa pines. As temperatures at these sites become colder, populations move to lower elevations and both taxa can be found in or near desert habitats throughout their ranges during the winter. These habitats are not available to these species during the hotter months of the year. Although few breeding records for either species exist, D. pseudoobscura has been reared from slime fluxes, domestic fruits, cacti, and agave (Powell 1997), suggesting that it may be an opportunistic species that can utilize a number of different host types. This would certainly agree with the almost complete lack of overlap in potential host plants between their summer (mountain) and winter (desert) ranges.

D. willistoni, a species that breeds in a wide range of rotting fruits, is probably one of the most numerous and broadly distributed drosophilids in the New World and can be found from southern South America to southern North America and throughout the Caribbean (Ayala 1971; Dobzhansky and Powell 1975). Although D. willistoni can be readily found in association with humans and the fruit trade within its traditional range, it has not yet been reported outside of the New World.

The three species in the subgenus Drosophila that have been sequenced also show a diversity of distributions and ecologies. D. virilis, a Holarctic species, has also been reared from fruits in urban settings, but naturally breeds in the fluxes of willows and other decaying parts of trees (Throckmorton 1982). D. mojavensis is found in the deserts of North America where it breeds in the necroses of several species of cacti (Heed 1978). This species and its relatives have evolved to tolerate not only the toxic compounds found in its hosts, but also the high desiccation conditions of the Sonoran Desert (Stratman and Markow 1998; Gibbs et al. 2003; Matzkin et al. 2006). Although most species of Hawaiian Drosophila are highly specific to a single host plant, D. grimshawi, a charismatic picture-winged species, is considered a generalist. It utilizes the decaying bark of over seven families of endemic Hawaiian plants (Magnacca and O'Grady 2006).

Behavioral evolution:

Variability in behavior has been reported for a great many Drosophila species, although measures have rarely been made in the same way. Genetics of nonreproductive behaviors for the genus have recently been reviewed by Sisodia and Singh (2005). Data exist on several of the sequenced species for behaviors such as pupation site preference, locomotor activity, phototaxis, and geotaxis. Far more is known of reproductive behaviors. Spieth (1952) was the first to categorize the elements of courtship behavior and to describe interspecific variability in these elements. Courtship behaviors of the 12 sequenced species differ in the relative roles of the particular sensory modes in mating: visual, chemical, and auditory (Markow and O'Grady 2005, 2006). For example, D. melanogaster and D. pseudoobscura will mate equally well in the light and the dark, while mating in their respective sibling species, D. simulans and D. persimilis, is repressed in darkness. Males of D. grimshawi, with their patterned wings, provide elaborate visual displays not seen in males of D. virilis or D. mojavensis, which tend to focus their courtship activities behind the females. Chemical profiles, or pheromones, differ in close relatives, both within and between species and between the sexes of a given species (Ferveur 2005). For example, D. melanogaster and D. sechellia possess long chain dienes not seen in D. simulans or D. erecta. The longest chain hydrocarbons are seen in D. mojavensis. These chemical differences predict that the olfactory and odorant binding receptors of these species would also be different. Finally, species such as D. virilis and D. mojavensis exhibit both male and female courtship songs, while in the other 10 species, only the males appear to sing (Markow and O'Grady 2005, 2006; Hoikkala 2006).

Life-history evolution:

Ecologists and evolutionary biologists now have the ability to use genomic information and genetic dissection tools to understand the heritable factors contributing to the dazzling array of life-history strategies observed in the genus Drosophila. This is an exciting avenue of research that will probe the selective forces that the environment exerts on the genome over evolutionary time. Several developmental and reproductive traits are currently being investigated. For example, there is a clear relationship between body size and egg-to-adult development time: the biggest flies require the longest time to develop (Table 1). Egg-to-adult development time is shortest in D. melanogaster, D. simulans, and D. ananassae, all of which require ∼10 days at 24°. The longest development time is in D. grimshawi. Development from egg to adult requires nearly a month.

TABLE 1.

Biological characteristics of the 12 sequenced species

| Species | F-thorax length (mm) | M-thorax length (mm) | Sexual dimorphisma | Egg to adult (days) | F-sexual maturity | M-sexual maturity | Female remating | Ovariole no. | Sperm length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. melanogaster | 0.99a | 0.88a | Ybc | 10a | 4a | 2a | 5a | 43a | 1.91a |

| D. simulans | 0.97a | 0.87a | Ybc | 10a | 3a | 1a | 5a | 40a | 1.14a |

| D. sechellia | Ybc | 12a | 16d | 1.60e | |||||

| D. yakuba | Ybc | 11a | 28e | 1.6g | |||||

| D. erecta | Ybc | 12a | 27e | 1.2g | |||||

| D. ananassae | 0.94 | 0.87 | Ybc | 10a | 7 | 30e | 3.3g | ||

| D. pseudoobscura | 1.09a | 1.01a | Ybc | 13a | 3a | 1a | 4a | 34a | 0.36af |

| D. persimilis | 1.06a | 0.93a | Ybc | 13a | 4a | 0a | 4a | 36a | 0.32af |

| D. willistoni | 0.83e | 0.79e | N | 13a | 3e | 2e | 4e | 36e | |

| D. mojavensis | 0.96a | 0.89a | N | 12a | 5a | 8a | 1a | 26a | 1.90a |

| D. virilis | 1.33a | 1.27a | N | 18a | 3a | 9a | 3a | 34a | 5.70a |

| D. grimshawi | 2.12e | 2.23e | N | 27a | 21e | 7e | Rarelye | 28e | 1.19e |

Columns 2–9: female (F)-thorax length, male (M)-thorax length, presence of sexual dimorphism, egg-to-adult development time in days, age in days at which 80% of females are sexually receptive, age at which 80% of males are sexually mature, number of days before female remates, female ovariole number, sperm length (mm).

Markow and O'Grady (2005a) and references therein.

Sexual dimorphism for color.

Sexual dimorphism for morphology: male sex combs.

T. A. Markow (unpublished data).

Sperm length dimorphism, Snook (1997).

Joly and Bressac (1974).

Interspecific differences in reproductive biology represent some of the most interesting features of the 12 species. Few species of Drosophila are ready to mate the moment they emerge from the pupa case. In those species in which flies are sexually mature upon emergence, the opposite sex typically requires several days before sexual maturity is achieved. Reproductive maturity times of the 12 species (Table 1) reflect the number of days after emergence by which 80% of flies of a given sex successfully mate with a sexually mature conspecific. Within the subgenus Sophophora, adult males tend to mature earlier than females, while in 2 species of the subgenus Drosophila, D. virilis and D. mojavensis, males require two to three time longer to reach sexual maturity. Female D. grimshawi, on the other hand, require at least 3 weeks to become sexually mature, almost three times longer than males. Proximate explanations for these differences appear to lie in the relative complexity of either gametogenesis or reproductive tract maturation in one sex or the other. An astounding 15-fold difference in sperm length exists among the 12 species, with D. persimilis having the shortest and D. virilis the longest sperm. Those species in which males mature before females tend to produce short sperm relative to those in which males mature much later than females (Table 1). In the case of D. mojavensis, whose sperm is similar in length to that of D. melanogaster, male accessory glands produce relatively large amounts of seminal fluid, the derivatives of which are taken up by females and incorporated into female somatic tissues and developing oocytes (Markow and Ankney 1984).

The development time in D. grimshawi may be related to egg development, rather than sperm formation. D. grimshawi females must produce eggs with immensely long chorionic filaments. Kambysellis and his collaborators have shown that the chorionic filament length is adaptive and correlated with the length of the female ovipositor, the type of oviposition substrate, and the depth to which the egg is inserted (Kambysellis 1993; Craddock and Kambysellis 1997). As the genetic pathways underlying life-history characteristics are elucidated, biologists will be able to better understand the complex interplay between the genome, development, behavior, and the environment.

Speciation genetics:

Biologists have long been interested in the genetic changes leading to the formation of new species. Much research has centered on the generation of partial or complete reproductive isolation, both in terms of premating and postmating barriers to the production of viable or fertile offspring. Genetic dissection techniques have been successful in implicating specific chromosomal regions or candidate genes (Ting et al. 2004; Brideau et al. 2006; Moehring et al. 2006), but the sequenced genomes will allow for finer-scale speciation genetics studies.

Most of the species sequenced have close relatives and have been the subject of intensive studies of speciation genetics involving both interspecific mating experiments and studies using nucleotide variation to examine cases of natural hybridization. When D. melanogaster females are crossed with males of either D. simulans or D. sechellia, the result is the production of sterile females and no males, in accordance with Haldane's rule—meaning that when hybrid inviability or sterility is observed it typically affects the heterogametic sex most profoundly (Haldane 1922; Coyne 1985; Wu et al. 1996; Orr 1997). The reciprocal crosses, however, are counter to Haldane's rule in that they produce sterile males and no surviving females (Lemeunier et al. 1986). Hybrids never have been obtained between D. erecta and any of its relatives, including its closest relative, D. orena, but this is not surprising given the great divergence times between these taxa. In the laboratory, D. ananassae produces fertile, viable hybrids in reciprocal crosses with its sibling species D. pallidosa, but in nature, sexual isolation, specifically differences in courtship song, prevent the two from interbreeding (Yamada et al. 2002).

Speciation genetics of the D. pseudoobscura–D. persimilis sibling pair began as early as 1929 (Lancefield 1929). Reciprocal crosses produce sterile male hybrids. With D. pseudoobscura mothers, however, ∼25% of the F1 females also are sterile, while the reciprocal cross produces fully fertile females (Dobzhansky 1936; Orr 1987). Sequence comparisons of mitochondrial and nuclear genes reveal evidence of recent introgression in different parts of the genomes of these two species (Machado and Hey 2003).

The sophophoran most distantly related to D. melanogaster is D. willistoni. While D. willistoni has been reported to inseminate and be inseminated by, at very low levels, its relatives such as D. equinoxialis and D. paulistorum, its reproductive isolation from these species is effectively complete and no hybrids are produced (Burla et al. 1949). Reproductive barriers also exist within D. willistoni. A population of D. willistoni collected west of the Andes near Lima, Peru, shows hybrid sterility with D. willistoni from the rest of South America, leading Ayala (1972) to designate the Peruvian strains as a separate subspecies, D. willistoni quecha.

In the subgenus Drosophila, D. virilis is able to cross with many of the other species in the virilis group. Not all crosses produce fertile or abundant progeny, however (Throckmorton 1982). This suggests that the barriers to reproductive isolation, and therefore the boundaries of what defines a species, in this group may be significantly different from those acting in the subgenus Sophophora. The cactophilic sibling pair D. mojavensis and D. arizonae have become a popular model system for speciation studies because they display a continuum of reproductive isolating mechanisms in interspecific crosses from various populations (Markow and Hocutt 1998). These include premating, postcopulatory–prezygotic, and postzygotic isolation. In addition, the distribution of D. mojavensis is bisected by the Sea of Cortez and populations from different regions exhibit signs of incipient speciation (Markow and Hocutt 1998).

Over 95% of the known Hawaiian Drosophila species are single island endemics. D. grimshawi is unusual in that it occurs on Maui, Molokai, and Lanai. Two of its closest relatives, D. craddockae from Oahu and Kauai and D. pullipes from Hawaii, are found on the remaining islands and thus the three species are allopatric. Crosses between D. pullipes and either D. craddockae or D. grimshawi produce some viable F1 progeny, but few males have motile sperm (Ohta 1980), indicating that D. pullipes is a distinct species, in spite of only subtle morphological differences. Crosses between D. grimshawi and D. craddockae produce fertile F1 progeny, but show a marked reduction in F2 fertility in reciprocal backcrossess, suggesting evidence for postmating breakdown (Kaneshiro and Kambysellis 1999). Furthermore, D. grimshawi is undergoing differentiation itself, genetically, morphologically, and ecologically, on the different islands it inhabits (Piano et al. 1997).

The evolution of genome size and rearrangement:

On the basis of comparative cytological studies of metaphase chromosomes, Patterson and Stone (1952) suggested that the ancestral karyotype in the genus Drosophila is composed of one dot and five acrocentric, or rod, chromosomes (Muller 1940; Sturtevant and Novitski 1941; Patterson and Stone 1952). All other chromosomal configurations are derived from this basic ancestral state via Robertsonian (Robertson 1957), or centromeric, fusions. It was Muller (1940) who first hypothesized that the genic content of these six different elements would remain relatively conserved over time because of the rarity of transposition events and the highly deleterious nature of pericentric inversions. The six chromosomal building blocks are lettered A–F and are referred to as Muller's elements. The D. melanogaster karyotype of one acrocentric, two metacentric, and one dot chromosome can be generated by two fusion events, one between Muller's B and C and another between Muller's D and E.

Following their role in demonstrating the chromosomal basis of inheritance, Drosophila have continued to be a model for studies of genome evolution and rearrangement. Genome sizes (Bosco et al. 2007, accompanying article in this issue; Gilbert 2007) and karyotypes (Table 2) are quite variable. Gain and loss of heterochromatin are likely explanations for the interspecific differences in genome size (Bosco et al. 2007; Gilbert 2007), while the basic Drosophila karyotype of five rods (acrocentric) and a dot chromosome differs among species primarily owing to centromeric fusions.

TABLE 2.

Genome sizes from assembled sequences, from flow cytometry (propidium iodide), both in megabases, and chromosome number for each species

| Species | Genome size assemblies | Genome size flow cytometryd | Chromosome no. (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| D. melanogaster | 117a | 178 ± 16 | 4 |

| D. simulans | 138b | 165 ± 2 | 4 |

| D. sechellia | 167b | 172 ± 4 | 4 |

| D. yakuba | 166b | 187 ± 11 | 4 |

| D. erecta | 153b | 146 ± 4 | 4 |

| D. ananassae | 231b | 206 ± 9 | 4 |

| D. pseudoobscura | 156c | 188 ± 4 | 4 |

| D. persimilis | 188b | 188 ± 5 | 4 |

| D. willistoni | 236b | 209 ± 7 | 3 |

| D. mojavensis | 193b | 143 ± 0 | 6 |

| D. virilis | 206b | 313 ± 11 | 6 |

| D. grimshawi | 201b | 216 ± 5 | 6 |

Bosco et al. (2007), accompanying article in this issue.

Conclusions and prospectus for future research:

The biological diversity of the 12 species provides unparalleled opportunities to address pressing questions about genome evolution, development, behavior, physiology, and species formation. Furthermore, the benefits of the genome sequences are not restricted to the 12 species: for each sequenced taxon, there are multiple related, biologically interesting species for which these genomes will prove a useful and informative springboard to future research. A century after its debut as a research organism, the Drosophila model now enters a new era as an even more robust tool for discovery.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gordon Bennett, Jeremy Bono, Erin Kelleher, Richard Lapoint, Karl Magnacca, Stacy Mazzalupo, Luciano Matzkin, Joel Nitta, Matthew Van Dam, and Tom Watts for critically reading earlier drafts of this manuscript. Kipling Will graciously allowed access to his Microptics camera for the adult and sex comb photos in Figure 1.

References

- Anderson, W. W., J. Arnold, D. G. Baldwin, A. T. Beckenbach, C. J. Brown et al., 1991. Four decades of inversion polymorphism in Drosophila pseudoobscura. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88: 10367–10371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner, M. A., K. G. Golic and R. S. Hawley, 2006. Drosophila: A Laboratory Handbook. Academic Press, New York.

- Ayala, F. J., 1971. Polymorphisms in continental and island populations of Drosophila willistoni. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 68: 2480–2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, F. J., 1972. Two new subspecies of the Drosophila willistoni group (Diptera). Pan-Pac. Entomol. 49: 273–279. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, C. M., B. D. Pfeiffer, D. E. Rincon-Limas, R. A. Hoskins, A. Gnirke et al., 2003. Assessing the impact of comparative genomic sequence data on the functional annotation of the Drosophila genome. Genome Biol. 3: 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock, I. R., and P. A. Parsons, 1981. Species of Australia and New Zealand, pp. 291–308 in The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila, Vol. 3a, edited by M. A. Ashburner, H. L. Carson and J. N. Thompson. Academic Press, London.

- Boffelli, D., J. McAuliffe, D. Ovcharenko, K. D. Lewis, I. Ovcharenko et al., 2003. Phylogenetic shadowing of primate sequences to find functional regions of the human genome. Science 299: 1391–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco, G., P. Campbell, J. T. Leiva-Neto and T. A. Markow, 2007. Analysis of Drosophila species genome size and satellite DNA content reveals differences among strains as well as between species. Genetics 177: 1277–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brideau, N. J., H. A. Flores, J. Wang, S. Maheshwari, X. Wang et al., 2006. Two Dobzhansky-Muller genes interact to cause hybrid lethality in Drosophila. Science 314: 1292–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burla, H., A. Brito da Cunha, A. R. Cordiero, Th. Dobzhansky, C. Malagolowkin et al., 1949. The willistoni group of sibling species of Drosophila. Evolution 3: 300–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caletka, B. C., and B. F. McAllister, 2004. A genealogical view of chromosomal evolution and species delimitation in the Drosophila virilis species subgroup. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 33: 664–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson, H. L., 1992. Inversions in Hawaiian Drosophila, pp. 407–439 in Drosophila Inversion Polymorphism, edited by C. B. Krimbas and J. R. Powell. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- Coyne, J. A., 1985. The genetic basis of Haldane's rule. Nature 314: 736–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, J. A., J. Rux and J. R. David, 1991. Genetics of morphological differences and hybrid sterility between Drosophila sechellia and its relatives. Genet. Res. 57: 113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celniker, S. E., E. Frise, A. Hodgson, R. A. George, R. A. Hoskins et al., 2002. Finishing a whole-genome shotgun: release 3 of the Drosophila melanogaster euchromatic genome sequence. Genome Biol. 3: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craddock, E. M., and M. P. Kambysellis, 1997. Adaptive radiation in the Hawaiian Drosophila (Diptera: Drosophilidae): ecological and reproductive character analyses. Pac. Sci. 51(4): 475–489. [Google Scholar]

- DeSalle, R., 1992. The intra- and inter-island relationships of Hawaiian Drosophila deduced from DNA sequence information. Am. J. Bot. 79(Suppl. 6): 126. [Google Scholar]

- Dobzhansky, Th., 1936. Studies of hybrid sterility II. Localization of sterility factors in D. pseudoobscura hybrids. Genetics 21: 113–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobzhansky, Th., and J. R. Powell, 1975. The willistoni group of sibling species of Drosophila, pp. 589–622 in Invertebrates of Genetic Interest, edited by R. C. King. Plenum Press, New York.

- Dobzhansky, Th., A. S. Hunter, O. Pavlovsky, B. Spassky and B. Wallace, 1963. Genetics of natural populations. XXXI. Genetics of an isolated marginal population of Drosophila pseudoobscura. Genetics 48: 91–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferveur, J. F., 2005. Cuticular hydrocarbons: their evolution and roles in Drosophila pheromonal communication. Behav. Genet. 35: 279–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frolova, S. L., and B. L. Astuarov, 1929. Die chromosomengarnitur als systematiches Merkmal. Eine verlechende untersuchung der russichen and amerkianischen Drosophila obscura Fallen. Z. Zellforsch. Mikrosk. Anat. 10: 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, A. G., M. C. Perkins and T. A. Markow, 2003. No place to hide: microclimates of desert Drosophila. J. Therm. Biol. 28: 353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, D. G., 2007. DroSpeGe: rapid access database for new Drosophila species genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 35: D480–D485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldane, J. B. S., 1922. Sex-ratio and unisexual sterility in hybrid animals. Genetics 12: 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Heed, W. B., 1978. Ecology and genetics of Sonoran Desert Drosophila, pp. 109–126 in Symposium on Genetics and Ecology: The Interface, edited by P. F. Brussard. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany.

- Hoikkala, A., 2005. Inheritance of male sound characteristics in Drosophila species, in Insect Sounds and Communication; Physiology, Ethology and Evolution, edited by S. Drosopoulis and M. Claridge. Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, FL.

- Joly, D., and C. Bressac, 1994. Sperm length in Drosophilidae (Diptera): estimation by testis and receptacle lengths. Int. J. Insect Morph. Embryol. 23(2): 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kambysellis, M. P., 1968. Comparative studies of oogenesis and egg morphology among species of the genus Drosophila. Univ. Tex. Publ. Stud. Genet. 4(6818): 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kambysellis, M. P., 1993. Ultrastructural diversity in the egg chorion of Hawaiian Drosophila and Scaptomyza: ecological and phylogenetic considerations. Int. J. Insect Morph. Embryol. 22: 417–446. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneshiro, K. Y., and M. P. Kambysellis, 1999. Description of a new allopatric sibling species of Hawaiian picture-winged Drosophila. Pac. Sci. 53(2): 208–213. [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher, E. S., and T. A. Markow, 2007. Reproductive tract interactions contribute to isolation in Drosophila. Fly 1: 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancefield, D. E., 1929. A genetic study of crosses of two races or physiological species of Drosophila obscura. Z. Indukt. Abstammungs. Vererbungsl. 52: 287–317. [Google Scholar]

- Lemeunier, F., J. R. David, L. Tsacas and M. A. Ashburner, 1986. The melanogaster species group, pp. 147–256 in The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila, Vol. 3e, edited by M. A. Ashburner, H. L. Carson and J. N. Thompson. Academic Press, London.

- Machado, C. A, and J. Hey, 2003. The causes of phylogenetic conflict in a classic Drosophila species group. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B 270: 1193–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnacca, K. N., and P. M. O'Grady, 2006. A subgroup structure for the modified mouthparts group of Hawaiian Drosophila. Proc. Hawaii. Entomol. Soc. 38: 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Markow, T. A., and P. F. Ankney, 1984. Drosophila males contribute to oogenesis in a multiple mating species. Science 224: 302–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markow, T. A., and G. D. Hocutt, 1998. Speciation in Sonoran Desert Drosophila: testing the limits of the rules, pp. 234–244 in Endless Forms: Species and Speciation, edited by D. A. Howard and S. Berlocher. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Markow, T. A, and P. M. O'Grady, 2005. Drosophila: A Guide to Species Identification and Use. Academic Press, London.

- Markow, T. A., and P. M. O'Grady, 2006. Evolutionary genetics of reproductive behavior in Drosophila. Annu. Rev. Genet. 39: 263–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzkin, L. M., T. Watts, B. G. Bitler, C. A. Machado and T. A. Markow, 2006. Functional genomics of cactus host shifts in Drosophila mojavensis. Mol. Ecol. 15: 4635–4643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister, B. F., 2002. Chromosomal and allelic variation in Drosophila americana: selective maintenance of a chromosomal cline. Genome 45: 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride, C. S., 2007. Rapid evolution of smell and taste receptor genes during host specialization in Drosophila sechellia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 4996–5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meigen, J. W., 1830. Systematische Beschreibung der Bekannten Europäischen Zweiflügeligen Insekten, Theil. Schulz, Hamm, Germany.

- Moehring, A. J., A. Llopart, S. Elwyn, J. A. Coyne and T. F. Mackay, 2006. The genetic basis of postzygtoic reproductive isolation between Drosophila santomea and D. yakuba. Genetics 173: 225–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses, A. M., D. A. Pollard, D. A. Nix, V. N. Iyer, X. Li et al., 2006. Large-scale turnover of functional transcription factor binding sites in Drosophila. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2: 1219–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, H. J., 1940. Bearings of the Drosophila work on systematics, pp. 185–268 in The New Systematics, edited by J. Huxley. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- O'Grady, P. M., and M. G. Kidwell, 2002. Phylogeny of the subgenus sophophora (Diptera: Drosophilidae) based on combined analysis of nuclear and mitochondrial sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 22(3): 442–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta, A., 1980. Coadapted gene complexes in incipient species of Hawaiian Drosophila. Am. Nat. 115: 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Okada, T., 1981. Oriental species, including New Guinea, pp. 261–290 in The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila, Vol. 3a, edited by M. A. Ashburner, H. L. Carson and J. N. Thompson. Academic Press, London.

- Orr, H. A, 1987. Genetics of male and female sterility in hybrids of Drosophila pseudoobscura and D. persimilis. Genetics 116: 555–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr, H. A., 1997. Haldane's rule. Annu. Rev. Evol. Syst. 28: 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, J. T., 1943. The Drosophila of the Southwest. Univ. Tex. Publ. 4313: 7–216. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, J. T., and G. B. Mainland, 1944. The Drosophilidae of Mexico. Univ. Tex. Publ. 4445: 9–101. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, J. T., and W. S. Stone, 1952. Evolution in the Genus Drosophila. Macmillian Press, New York.

- Piano, F., E. M. Craddock and M. P. Kambysellis, 1997. Phylogeny of the island populations of the Hawaiian Drosophila grimshawi complex: evidence of combined data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 7: 173–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, D. A., A. M. Moses, V. N. Iyer and M. B. Eisen, 2006. Detecting the limits of regulatory element conservation and divergence estimation using pairwise and multiple alignments. BMC Bioinform. 7: 376–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popadic, A., and W. W. Anderson, 1994. The history of a genetic system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91: 6819–6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell, J. R., 1997. Progress and Prospects in Evolutionary Biology: The Drosophila Model. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Richards, S., R. P. Meisel, O. Couronne, S. Hua, M. A. Smith et al., 2005. Comparative genome sequencing of Drosophila pseudoobscura: chromosomal, gene, and cis-element evolution. Genome Res. 15: 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R'Kha, S., P. Capy and J. R. David, 1991. Host plant specialization in the Drosophila melanogaster species complex: a physiological, behavioral and genetic analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88: 1835–1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, F. W., 1957. Studies in quantitative inheritance. J. Genet. 55: 410–427. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, C. A. M., N. Takezaki and M. Nei, 1995. Molecular phylogeny and divergence times of drosophilid species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 12(3): 391–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B. N., 2000. Drosophila ananassae: a species characterized by several unusual genetic features. Curr. Sci. 78: 391–398. [Google Scholar]

- Sisodia, S., and B. N. Singh, 2005. Behaviour genetics of Drosophila: non-sexual behaviour. J. Genet. 84: 195–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snook, R. R., 1997. Is the production of multiple sperm types adaptive? Evolution 51(3): 797–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spieth, H. T., 1952. Mating behaviour within the genus Drosophila (Diptera). Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 99: 395–474. [Google Scholar]

- Spieth, H. T., 1981. History of the Hawiian Drosophila project. DIS 56: 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Stratman, R., and T. A. Markow, 1998. Resistance to thermal stress in desert Drosophila. Funct. Ecol. 8: 965–970. [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant, A. H., 1916. Notes on North American Drosophilidae with descriptions of 23 new species. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 9: 323–343. [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant, A. H., 1919. A new species closely resembling Drosophila melanogaster. Psyche 26: 153–155. [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant, A. H., 1921. The North American species of Drosophila. Publ. Carnegie Inst. 301: 1–150. [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant, A. H., 1939. On the subdivision of the genus Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 25: 137–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant, A. H., 1942. The classification of the genus Drosophila, with descriptions of nine new species. Univ. Tex. Publ. 4213: 5–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant, A. H., and E. Novitski, 1941. The homologies of the chromosome elements in the genus Drosophila. Genetics 26: 517–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Throckmorton, L. H., 1975. The phylogeny, ecology and geography of Drosophila, pp. 421–469 in Invertebrates of Genetic Interest (Handbook of Genetics, Vol. 3), edited by R. C. King. Plenum Press, New York.

- Throckmorton, L. H., 1982. The virilis species group, pp. 227–297 in The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila, Vol. 3b, edited by M. A. Ashburner, H. L. Carson and J. N. Thompson. Academic Press, London.

- Ting, C. T., S. C. Tsaur, S. Sun, W. E. Browne, Y. C. Chen et al., 2004. Gene duplication and speciation in Drosophila: evidence from the Odysseus locus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 12232–12235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobari, Y. N., 1992. Drosophila ananassae: Genetical and Biological Aspects. Japan Scientific Societies Press, Tokyo.

- Tsacas, L., D. Lachaise and J. R. David, 1981. Composition and biogeography of the Afrotropical Drosophilid fauna, pp. 197–260 in The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila, Vol. 3a, edited by M. A. Ashburner, H. L. Carson and J. N. Thompson. Academic Press, London.

- Wu, C. I., N. A. Johnson and M. F. Palopoli, 1996. Haldane's rule and its legacy: Why are there so many sterile males? Trends Ecol. Evol. 11: 281–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, H., M. Matsuda and Y. Oguma, 2002. Genetics of sexual isolation based on courtship song between two sympatric species: Drosophila ananassae and D. pallidosa. Genetica 116: 225–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]