Abstract

Cisterna chyli is prone to injury in any retroperitoneal surgery. However, retroperitoneal chylous leakage is a rare complication after anterior spinal surgery. To the best of our knowledge, only ten cases have been reported in the English literature. We present a case of a 49-year-old man who had lumbar metastasis and associated radiculopathy. He had transient retroperitoneal chylous leakage after anterior tumor decompression, interbody bony fusion, and instrumental fixation from L2 to L4. The leakage stopped spontaneously after we temporarily clamped the drain tube. Intraperitoneal ascites accumulation developed thereafter due to nutritional loss and impaired hepatic reserves. We gathered ten reported cases of chylous leak after anterior thoracolumbar or lumbar spinal surgery, and categorized all these cases into two groups, depending on the integrity of diaphragm. Six patients received anterior spinal surgery without diaphragm splitting. Postoperative chylous leak stopped after conservative treatment. Another five cases received diaphragm splitting in the interim of anterior spinal surgery. Chylous leakage stopped spontaneously in four patients. The remaining one had a chylothorax secondary to postop chyloretroperitoneum. It was resolved only after surgical intervention. In view of these cases, all the chylous leakage could be spontaneously closed without complications, except for one who had a secondary chylothorax and required thoracic duct ligation and chemopleurodesis. We conclude that intraoperative diaphragm splitting or incision does not increase the risk of secondary chylothorax if it was closed tightly at the end of the surgery and the chest tube drainage properly done.

Keywords: Anterior spinal surgery, Chylous leakage, Diaphragm splitting

Introduction

Chylous leakage is a rare complication that occurs after retroperitoneal surgery [5]. It is much rare after an anterior approach of spinal surgery. The etiology of this clinical entity is injury of retroperitoneal lymphatic vessels. However, because of the rich lymphatic network that reroute the disrupted lymphatic flow, chylous leakage usually heals spontaneously and seldom becomes clinically evident [10, 14].

Traditional or surgical management has been extensively discussed and universally applied in various etiologies of chylous leakage [5, 10]. For postoperative leakage, especially after an anterior spinal surgery, some unique and important characteristics exist. In the interim of the anterior approaches to either thoracolumbar or lumbar spines, the lymphatic system is usually not so extensively injured as in abdominal oncological surgery, but the diaphragm is sometimes incised or split for better exposure. Intactness of the diaphragm may likely affect the possibility of occurrence of chylothorax following retroperitoneal chylous leakage.

Herein, we report about a case where the subject had a transient retroperitoneal chylous leakage after an anterior spinal surgery from L2 to L4. We then reviewed ten similar published cases, in addition to our own, to delineate patterns of chylous leakage that depend on the integrity of the diaphragm.

Case report

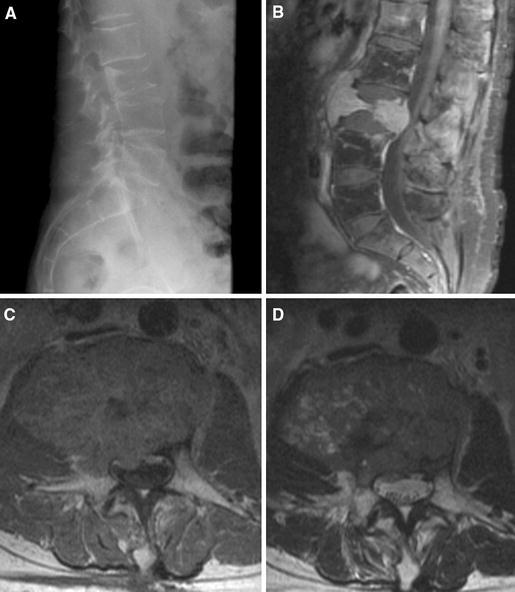

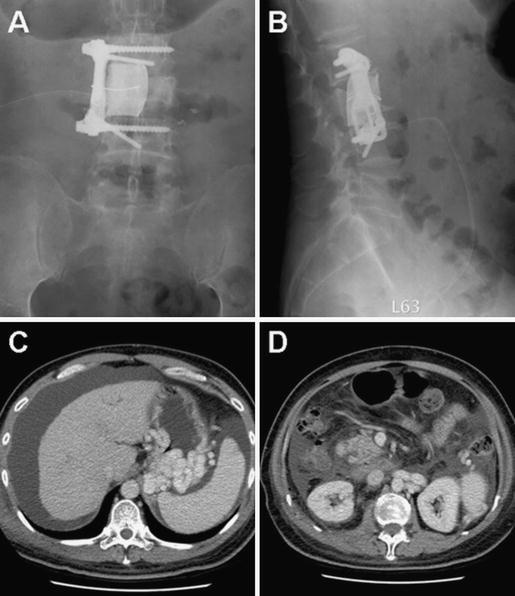

This patient, a 49-year old male, had a history of hepatitis C virus related liver cirrhosis (Child’s classification A) and hepatocellular carcinoma. He had received transarterial embolization and transcutaneous ethanal injection of the hepatomas 1 year earlier. A few weeks before admission, he presented a progressive difficulty in walking on the background of a 3 months severe lumbago. Physically, the patient had a mild hypesthesia at right L3 and L4 dermatome, and the muscle power of knee flexion slightly decreased on the right side. A lateral lumbosacral roentogenograph was consistent with a compressive fracture the L3 vertebral body with erosion of cortices (Fig. 1a). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the thoracolumbar spine showed a large paraspinal contrast-enhanced tumor involving the L3 vertebral body, pedicles and extending into the neural foramen and spinal canal (Fig. 1a–c). The right L3 nerve root was markedly compressed. A hepatocellular carcinoma with L3 spinal metastasis and radiculopathy was diagnosed. The patient underwent tumor decompression of L3 using a standard anterior-lateral retroperitoneal approach from the right side. Following decompression, anterior lumbar interbody fusion from L2 to L4 was performed followed by Z-plate internal fixation. During dissection, the right hemidiaphragm was left uninterrupted, and the cisterna chyli and chylous leakage were not identified throughout the operation. A retroperitoneal drain tube was routinely inserted. Postoperative roentogenographs showed that the bony fusion and plate were properly placed (Fig. 2a, b).

Fig. 1.

Preoperative lateral roentogenograph (a) showing a compressive fracture of L3 vertebral body. Sagittal (b) and axial (c) T1 MRI with intravenous gadolinium injection, and axial T2 MRI (d) of lumbar spine demonstrating a right paraspinal contrast-enhanced tumor involving the L3 vertebral body, pedicles and extending into the neural foramen and epidural space

Fig. 2.

Postoperative anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) roentogenographs showing a proper position of interbody bony cement, screws, and Z plate crossing from L2 to L4. CT scan 6 days after the operation demonstrating a large intraperitoneal ascites (c) without retroperitoneal fluid collection (d)

On the first postoperative day, 1,700 ml of milky white fluid was yielded from the indwelling drain tube. Evaluation of the fluid revealed a triglyceride level of 224 mg/dl and cholesterol level of 15 mg/dl. Corresponding serum levels for triglyceride were 64 mg/dl and for cholesterol 64 mg/dl. The findings were consistent with retroperitoneal chyle leak. The drain tube was clamped temporarily for half-a-day to tamponade the leakage. On postoperative day two, the drain became sanguineous in color instead of milky white, and the daily amount eased to less than 200 ml. The drain tube was removed 3 days after the operation.

From the fourth postoperative day, the patient’s abdominal girth and body weight increased gradually. Physically, the abdomen was distended and was dull in percussion. Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a large amount of intraperitoneal fluid collection without retroperitoneal accumulation (Fig. 2c, d). Diagnostic paracentesis yielded a clear and yellowish fluid. Laboratory analysis of the fluid found triglycerides at 10 mg/dl, cholesterol at 5 mg/dl, and albumin at 0 mg/dl. This was characteristic of transudatory ascites, not chyle. Laboratory serum study showed hypoalbuminemia and increased bilirubin level and prothrombin time, which indicated the patient’s poor nutritional status and impaired hepatic reserve. After intravenous albumin administration, nutritional support, and a continuous right lower quadrant drainage, the ascites disappeared on postoperative day 10. The tube draining the intraperitoneal space was then removed. Since then, the symptoms completely resolved. No recurrent chyle or ascites accumulation was observed. He thus started to receive irradiation for the spinal metastases.

Discussion

Chylous leakage is a rare complication after spinal surgery using an anterior retroperitoneal approach. This disease has been attributed to direct injury of the retroperitoneal lymphatic trunk by surgical maneuver. The main lymphatic vessels in this region include the thoracic duct, cisterna chyli, and its three tributaries.

Below the diaphragm, the lymphatic system is comprised of vessels following the aorta and inferior vena cava upward into the retroperitoneum [7, 10]. The cisterna chyli is formed by union of two lumbar lymphatic trunks and an intestinal trunk anterior to the L1 or L2 vertebra [5]. It is only after the contribution of chylomicron from the intestinal trunk that the characteristic whitish and milky chyles appear. It ascends through the aortic hiatus of the diaphragm and enters the posterior mediastinum [5, 10]. It then traverses in proximity with the aorta before crossing over to the left side of the thorax (at T5 level) and emptying into either the left subclavian or internal jugular vein [5, 10].

The diagnosis of chylous leakage is confirmed by its typical milky white appearance as well as by laboratory analysis of the fluid that consists of high amounts of triglycerides but small amounts of cholesterol [11]. Triglyceride values of chyle are usually above 200 mg/dl, while the ratio of ascites to serum cholesterol values should be less than one [5]. Because cisterna chyli and its rich lymphatic tributaries surround the vertebral column extensively, they are theoretically prone to injury in any retroperitoneal surgery. Interestingly, however, complications of postoperative chylous ascites remain rare [1, 5, 10]. In vascular surgery of abdominal aorta, chyloretroperitoneum comprises less than 1% of all complications [4, 10]. Retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy performed for testicular cancer results in 1.2% of incidence rate of chylous leakage [2]. Kaas et al. [9] reported an incident rate of 1.1% in all cancer patients undergoing abdominal surgical procedures, or of 7.4% in patients with high risk procedures. To our best knowledge, retroperitoneal chylous leakage is reported only in ten cases after an anterior thoracolumbar or lumbar spinal surgery [3, 7, 8, 12, 14]. Rarity of chylous leakage is probably attributed to two reasons. First of all, collateral lymphatic pathways that reroute disrupted lymphatic flow are thought to minimize the leakage. Meanwhile, fasting for 1 day before the operation dramatically reduces the lymphatic flow to less than 1 ml/min [8]. Therefore, the incidence will be under estimated if the chylous leakage is small in amount and heal spontaneously rapidly, or if it is admixed with the serosanguinous fluid removed from the routinely inserted retroperitoneal drain tubes.

The ten reported cases of chyloretroperitoneum after anterior spinal surgery could be categorized into two groups. In the first group, diaphragm was not split during blunt retroperitoneal dissection (Table 1). DeHart et al. [7] identified chylous leakage intraoperatively from the injured lymphatics in two cases during dissection. Attempts to repair the rent were partially successful, and a small leakage persisted. In these two cases, the wounds were closed without a retroperitoneal drain in an attempt to tamponade the leakage. No evidence of postoperative chylous leakage was noted. Nagai et al. [12] and Hanson et al. [8] reported another two cases where the subject had postoperative chyloretroperitoneum. The retroperitoneal drain was removed after the leakage stopped spontaneously, and no recurrence of chylous accumulation was noted. In our case, the chylous leakage was also stopped after the drainage tube was temporarily clamped for tamponade. Bhat et al. [3] interestingly, reported a case that had a combined occurrence of chyloretroperitoneum and chylothorax after the operation. Drainage tube was removed after chylous leak disappeared. No recurrence of leakage was observed. In analysis of six cases mentioned above, all of whom received anterior spinal surgery below the L1 level, without diaphragm splitting, the most likely mechanism of chylous leakage was injury of the cisterna chyli anterior to the L1 or L2 vertebral bodies or their tributaries [3]. Intact diaphragm acted as a barrier that prevented upward migration of chyle. Retroperitoneum thus remained a closed system that exerted an efficient tamponade effect and could promote spontaneous healing of lymphatic vessels [7, 14]. This mechanism probably contributed to the rapid diminish of chylous leak in our case after clamping of the drain tube. In other words, the retroperitoneal drain tube could usually be removed without complications when the diaphragm remained intact. The only case that had a combined occurrence of chyloretroperitoneum and chylothorax was believed to have an abnormal fistulous connection above and below the diaphragm [3]. Chyle might also slowly dissected into the posterior mediastinum with subsequent rupture into the pleural cavity [6].

Table 1.

Literature review of case reports: retroperitoneal chylous leakage following anterior spinal surgery using standard retroperitoneal dissection with or without diaphragm splitting

| Patient | Age/sex | Operative method | Treatment | Outcome | Author | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: Anterior spinal surgery without diaphragm splitting | ||||||

| 1 | 36/F | Anterior fusion L2–L4 | Repair injured vessela | No postop chylous accumulation | DeHart | [4] |

| 2 | 46/F | Anterior fusion L1–S1 | Repair injured vessela | No postop chylous accumulation | DeHart | [4] |

| 3 | 42/M | Decompression and fusion L1–L2 | Postop drainage | No recurrence | Nagai | [12] |

| 4 | 64/F | Anterior fusion L2–S1 | Simple drainage of both accumulationb | No recurrence | Bhat | [10] |

| Retroperitoneal serosanguinous fluid accumulation | ||||||

| 5 | 43/M | Anterior decompression and fusion L3–L4 | Postop drainage | No recurrence | Hanson | [11] |

| 6 | 49/M | Anterior decompression and fusion L2–4 | Clamp drain for tamponade | No recurrence | Our case | |

| Intraperitoneal ascites accumulation | ||||||

| Group 2: Anterior spinal surgery with diaphragm splitting | ||||||

| 7 | 22/M | Thoracolumbar arthrodesis | Postop chest and retroperitoneal drainage | No recurrence | Shen | [3] |

| 8 | 28/M | Decompression L2 | Repair injured vessela Postop chest drainage |

No postopchylous accumulation | DeHart | [4] |

| 9 | 14/F | Thoracolumar arthrodesis | Postop drainage | No recurrence | Bhat | [10] |

| 10 | 29/M | Decompression and thoracolumbar fusion | Postop retroperitoneal drainage | No recurrence | Nagai | [12] |

| 11 | 45/F | Decompression and thoracolumbar fusion | Postop retroperitoneal drainage | Chylothorax developed Require thoracic duct ligation and pleurodesis to stop leakage | Nagai | [12] |

aChylous leakage was found intraoperatively. The injured vessels were repaired during the surgery without postoperative retroperitoneal drain tube

bChyloretroperitoneum and chylothorax were both noted simultaneously

The second group was consisted of five cases that received anterior spinal surgery at the upper lumbar or thoracolumbar level with diaphragm splitting during retroperitoneal dissection (Table 1). At the end of the surgery, a fluid-tight anatomic closure of the diaphragm was performed. In addition to a retroperitoneal drain tube, a chest tube was prophylactically placed and was usually removed first after the operation. DeHart et al. [7] described one case that developed intraoperative chylous leakage. The injured lymphatic vessels were repaired. Though left hemidiaphragm was partially incised in the interim of retroperitoneal dissection and was closed at the end of procedure, no retroperitoneal fluid collections were noted after the operation. Shen et al. [14] reported one case that developed postoperative chyloretroperitoneum. No recurrence was noted after the drainage tube was removed on day 23, when the leakage was minimal. Nagai et al. [12] and Bhat et al. [3] reported two similar cases where postoperative chylous leakage disappeared after the drainage fluid stopped. The most characteristic case, reported by Nagai et al. [12] also developed postoperative chyloretroperitoneum. The drain tube was removed 2 days later because no fluid was draining at that time. Five weeks later, however, massive left chylothorax was found. Initial medical treatment, including a chest drainage tube and total parental nutrition support, failed to stop the leakage. Only after thoracic duct ligation followed by chemical pleurodesis did the chylous leakage stop. These five cases, that received anterior spinal surgery with diaphragm splitting, showed that the chylous leakage was attributed to injury of the cisterna chyli and/or thoracic duct [12]. Chyloretroperitoneum ceased spontaneously in all cases, and only one patient developed chylothorax secondary to either chyloretroperitoneum or injured thoracic duct [12]. The author attributed this complication to early removal of the drainage tube, which resulted in a delay in the detection of aspiration of chyle into the thoracic cavity through the incision in the diaphragm [12]. The unhealed diaphragm might act as a route for chyle spread [3, 11]. Diaphragmatic and/or parietal pleural defects have been shown to be responsible for the occurrence of chylothorax secondary to chyloretroperitoneum. To prevent this complication, some technical tricks were worthy of mention. While the crus of the diaphragm were divided away from the vertebral body, mobilization of the parietal pleura should be done with blunt dissection. All attentions should be paid to preserve the pleura intact. At the end of the surgery, diaphragm should be closed tightly. Tissue glues were also probably another option that was beneficial to seal off any diaphragmatic or pleural defects. After the operation, the routinely placed chest tube should be removed only when the tube does not aspirate any chylous fluid from retroperitoneal spaces. If operators followed these principles, chylothorax less likely developed secondary to the chyloretroperitoneum. In other words, diaphragmatic splitting itself did not increase the incidence rate of chylothorax. Retroperitoneal chylous leakage usually stopped spontaneously without complications.

When chylous leakage occurred, a low-fat diet should be undertaken to decrease lymphatic flow and promote closure of lymphatic vessels [5, 10]. However, nutritional support was also another important task in the treatment of chylous leakage. High protein and medium chain triglycerides diet were mandatory, since the latter bypassed the laympahtic vessels, and was directly absorbed into the bloodstream without contribution to the formation of lymph [5, 10]. Total parental nutrition was sometimes necessary if the modified diet still failed to stop chylous leakage. Occasionally, surgical intervention should be considered when medical treatment failed [5]. According to Selle et al’s [13] report, a daily chyle flow exceeding 1,500 ml in adults for a duration of more than 5 days is an indication for surgical ductal ligation. In our case, although chylous leakage spontaneously stopped, the high amount of chyle loss on postoperative day one, in association with poor intake for days, resulted in malnutrition and impaired hepatic reserve in this patient with chronic liver disease. This led to hypoalbuminemia and associated generalized edema. Only after the supplementation of albumin and nutritional support did the edema could subside. The importance of nutritional supplements in patients with chylous leakage thus cannot be over emphasized, especially in those with pre-existing liver diseases.

Conclusions

This case is illustrative of the possibility of chyloretroperitoneum after anterior spinal surgery, a complication rarely documented. Ten cases of retroperitoneal chylous leak after anterior spinal surgery have been reported in the English literature. Analyzing these cases, we summarize that chylous leakage in patients who received spinal surgery below L1 level without diaphragm splitting is attributable to injury of the cisterna chyli. The tamponade effect usually stopped the leakage spontaneously. In contrast, postoperative chyloretroperitoneum requiring diaphragm splitting is attributable to injury of the cisterna chyli and/or thoracic duct. Chylous leakage in the retroperitoneum stopped spontaneously in all cases, and only one out of five patients developed chylothorax secondary to chyloretroperitoneum or to unhealed thoracic duct injury. Therefore, diaphragmatic spitting itself did not increase the incidence rate of chylothorax.

Contributor Information

I-Chang Su, Email: ichangsu@ha.mc.ntu.edu.tw.

Chang-Mu Chen, Phone: +886-2-28285217, FAX: +886-2-28285217, Email: cmchen10@ms27.hinet.net.

References

- 1.Ablan CJ, Littooy FN, Freeark RJ. Postoperative chylous ascites: diagnosis and treatment. A series report and literature review. Arch Surg. 1990;125:270–273. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410140148027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baniel J, Foster RS, Rowland RG, et al. Management of chylous ascites after retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for testicular cancer. J Urol. 1993;150:1422–1424. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35797-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhat AL, Lowery GL. Chylous injury following anterior spinal surgery: case reports. Eur Spine J. 1997;6:270–272. doi: 10.1007/BF01322450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Busch T, Lotfi S, Sirbu H, et al. Chyloperitoneum: a rare complication after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Ann Vasc Surg. 2000;14:174–175. doi: 10.1007/s100169910030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardenas A, Chopra S. Chylous ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1896–1900. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cevese PG, Vecchioni R, D’Amico DF, et al. Postoperative chylothorax. Six cases in 2,500 operations, with a survey of the world literature. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1975;69:966–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeHart MM, Lauerman WC, Conely AH, et al. Management of retroperitoneal chylous leakage. Spine. 1994;19:716–718. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199403001-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanson D, Mirkovic S. Lymphatic drainage after lumbar surgery. Spine. 1998;23:956–958. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199804150-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaas R, Rustman LD, Zoetmulder FA. Chylous ascites after oncological abdominal surgery: incidence and treatment. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001;27:187–189. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2000.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leibovitch I, Mor Y, Golomb J, et al. The diagnosis and management of postoperative chylous ascites. J Urol. 2002;167:449–457. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)69064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muns G, Rennard SI, Floreani AA. Combined occurrence of chyloperitoneum and chylothorax after retroperitoneal surgery. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:185–187. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08010185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagai H, Shimizu K, Shikata J, et al. Chylous leakage after circumferential thoracolumbar fusion for correction of kyphosis resulting from fracture. Report of three cases. Spine. 1997;22:2766–2769. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199712010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selle JG, Snyder WH, 3rd, Schreiber JT. Chylothorax: indications for surgery. Ann Surg. 1973;177:245–249. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197302000-00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen YS, Cheung CY, Nilsen PT. Chylous leakage after arthrodesis using the anterior approach to the spine. Report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:1250–1251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]