Abstract

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (p42/p44 MAPK, also called Erk2 and Erk1) are key mediators of signal transduction from the cell surface to the nucleus. We have previously shown that the activation of p42/p44 MAPK required for transduction of mitogenic signaling is associated with a rapid nuclear translocation of these kinases. However, the means by which p42 and p44 MAPK translocate into the nucleus after cytoplasmic activation is still not understood and cannot simply be deduced from their protein sequences. In this study, we have demonstrated that activation of the p42/ p44 MAPK pathway was necessary and sufficient for triggering nuclear translocation of p42 and p44 MAPK. First, addition of the MEK inhibitor PD 98059, which blocks activation of the p42/p44 MAPK pathway, impedes the nuclear accumulation, whereas direct activation of the p42/p44 MAPK pathway by the chimera ΔRaf-1:ER is sufficient to promote nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK. In addition, we have shown that this nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK required the neosynthesis of short-lived proteins. Indeed, inhibitors of protein synthesis abrogate nuclear accumulation in response to serum and accelerate p42/p44 MAPK nuclear efflux under conditions of persistent p42/p44 MAPK activation. In contrast, inhibition of targeted proteolysis by the proteasome synergistically potentiated p42/p44 MAPK nuclear localization by nonmitogenic agonists and markedly prolonged nuclear localization of p42/p44 MAPK after mitogenic stimulation. We therefore conclude that the MAPK nuclear translocation requires both activation of the p42/p44 MAPK module and neosynthesis of short-lived proteins that we postulate to be nuclear anchors.

Keywords: growth factors, signal transduction, protein kinases, cell compartmentation, cell nucleus

The sequence of events linking cell surface receptor– mediated signals to expression of specific genes has received considerable attention over the years. One of such signaling modules is the p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)1 pathway, which transmits signaling from receptor tyrosine kinases, some G protein–coupled receptors, cytokine receptors, and integrins through the following activation cascade: Ras/Raf/MAPK kinase (MEK)/p42/p44 MAPK (for reviews see 25, 41). Among all the members of this signaling cascade, p44 and p42 MAPK isoforms (equivalent to Erk1 and Erk2) have been shown to be the only ones able to accumulate in the nucleus after mitogenic stimulation (8, 18, 27). In relation to this nuclear event, it has been demonstrated that p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylate multiple transcription factors, Elk-1 being one of the best characterized examples (16, 29), for which phosphorylation by p42/p44 MAPK has been demonstrated to increase its transcriptional activity (17, 21). Recently, Jaaro et al. (23) have shown that truncated or mutated forms of MEK can localize in the nucleus, but they confirm our initial report that the wild-type form of MEK remains in the cytoplasm (27), a feature dependent on a nuclear export signal in its sequence (14, 23). Thus, although MEK may enter in the nucleus, it is readily exported and thus cannot be found accumulated in it (14, 27, 35, 48). The mechanism by which p42/p44 MAPK are sequestered in the cytoplasm in resting cells and translocate to the nucleus upon mitogenic stimulation is still unknown. Certainly, it cannot be explained by the unmasking of a canonical nuclear localization signal (NLS) (6) that would accelerate this transfer to the nucleus (for reviews on nucleocytoplasmic transfer see 38, 40). Nuclear localization of p42/p44 MAPK is reversible (8, 18, 27), and the only known reversible modification of p42 and p44 MAPK is their dual phosphorylation upon activation by MEK (1, 10, 47). We and others have demonstrated that nonphosphorylatable and inactive mutated forms of p44 MAPK are still able to translocate to the nucleus (18, 26, 27). Recently, Khokhlatchev et al. (26) reported that microinjected mutants of p42 MAPK can dimerize with phosphorylated wild-type p42 MAPK to enter the nucleus. Further studies are needed to clarify the role of MAPK dimerization in the mechanism of nuclear translocation.

In this study, however, we have demonstrated in vivo that activation of the p42/p44 MAPK plays a key role in triggering its nuclear translocation. Moreover, this activation is both necessary and sufficient. Indeed, blocking the activation of p42/p44 MAPK with the MEK inhibitor Park Davis 98059 (PD 98059; references 2, 12) impedes nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK, while the sole activation of this pathway by the chimera ΔRaf-1:ER (28, 43, 44) results in the nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK. In addition, we have shown that the nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK that peaks after 3 h of serum stimulation requires the neosynthesis of short-lived proteins. Blocking serum-dependent transcriptional activation by actinomycin D or blocking protein synthesis by cycloheximide, two actions that do not suppress MAPK activation by serum, impedes nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK. In addition, blocking protein synthesis during mitogenic stimulation accelerates the efflux of p42/p44 MAPK from the nucleus. This result indicates that the proteins that contribute to the nuclear retention of p42/p44 MAPK are short-lived. In fact, the stabilization of these short-lived proteins via inhibition of targeted proteolysis by the proteasome (for reviews see 4, 42) greatly potentiated p42/p44 MAPK nuclear localization. However, the rapid entry of MAPK into the nucleus does not require protein synthesis. In conclusion, the data presented here lead us to dissociate two events: the rapid nuclear entry of p42/p44 MAPK and the nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK. Both processes require robust activation of p42/p44 MAPK, the second being dependent on neosynthesis of short-lived proteins (most likely nuclear anchors) induced by activation of the p42/p44 MAPK cascade.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Texas red–conjugated anti–rabbit antibody was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) and CITIFLUOR was purchased from UKC Chem Lab (Canterbury, UK). Anti-MAPK antibody R2 was obtained from Upstate Biotechnologies, Inc. (Lake Placid, NY). This antibody was directed against the peptide sequence corresponding to the amino acids 333–367 of the COOH terminus of Rat Erk1 (catalog #06-182). The proteasome inhibitor N-Acetyl-Leu-Leu-norLeucinal (LLnL) was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). The proteasome inhibitor lactacystin (synthetic) was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). All other chemicals were of the highest purity available.

Cell Line and Cell Culture

Chinese hamster lung fibroblasts CCL39 were maintained in DME (catalog #52100; Life Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) containing 25 mM NaHCO3. The derived CCL39-ΔRaf-1:ER clone (28) was maintained in DME without phenol red and supplemented with glutamine and glucose to reach the concentrations of normal DME (catalog #11880). Both culture media were supplemented with 7.5% FCS (GIBCO-BRL; Life Technologies, Inc.), penicillin (50 U/ml), and streptomycin (50 μg/ml). Cells were maintained at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2.

The CCL39-ΔRaf-1:ER clonal cell line was obtained by transfection of CCL39 cells with the plasmid pLNCΔRaf-1:ER (44) and selection of clones resistant to Geneticin (G418, GIBCO-BRL). The clone that displayed the highest stimulation of p42/p44 MAPK activity upon β-estradiol addition was selected, and its characteristics were reported (28).

Quiescent cells (G0-arrested) were obtained by incubating confluent cultures in serum-free medium for 24–48 h. Cells were then treated with various agents as described in Results and figure legends.

Indirect Immunofluorescence Analysis

G0-arrested or serum-stimulated CCL39 cells were fixed at −20°C for 10 min with methanol/acetone (70:30, vol/vol) without previous PBS wash. After a 10-min rehydration at 25°C in PBS containing 10% FCS (PBS/ FCS), fixed cells were then incubated with the R2 antibody from Upstate Biotechnologies, Inc., for 60 min at 25°C in PBS/FCS (dilution 1:2,000). Cells were then washed five times with PBS and incubated in PBS/FCS for 60 min at 25°C with Texas red–conjugated anti–rabbit antibody (1:500). Finally, cells were washed five times with PBS, mounted under glass coverslides with CITIFLUOR media, and examined under epifluorescent illumination with excitation-emission filters for Texas red. To control for specificity, (a) the same results were obtained when cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in methanol at −20°C for 15 min or with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 20°C for 15 min followed by permeabilization with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min at 20°C (data not shown), and (b) incubation with secondary antibody alone did not reveal any significant fluorescent signal (data not shown). R2 antibodies raised against the last 35 amino acids of Rat Erk1 are in fact very specific for p44 MAPK. This was resolved by using mouse embryo fibroblasts lacking Erk1 that we have obtained in our laboratory. With these cells, we showed that p42 MAPK translocation and retention in the nucleus follow the same features as those of p44 MAPK. Therefore, we invariably denote translocation of p42/p44 MAPK all along this manuscript.

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting

Confluent cells were lysed in a lysis buffer (0.1% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM benzamidine, 40 mM paranitrophenylphosphate, and 200 μM orthovanadate). 25 μg of detergent-extracted proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 12.5% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel (30:0.2) and electrophoretically transferred to immobilon-P membrane (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA). Immunoprobing was performed with the antibody E1B as previously described (28).

p42/p44 MAPK Kinase Assay

p42/p44 MAPK activity was assayed as previously described (28). In brief, cells were lysed in the lysis buffer described in the previous section. After centrifugation to remove insoluble cell fragments, the supernatant was incubated with 5 μl of the MAPK precipitating antibody Kelly as previously described (28) and protein A–Sepharose (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). The immune complex was washed five times with the lysis buffer and once with the kinase buffer without substrate. Immunoprecipitated MAPK was then incubated for 20 min at 30°C in the kinase buffer: 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 20 mM paranitrophenylphosphate, 0.25 mg/ml myelin basic protein and 30 μM ATP (3 μCi of [γ32P]ATP). The kinase reaction was stopped by adding Laemmli buffer, and the myelin basic protein was separated by an SDS–polyacrylamide gel (10%, 29:1). Radioactivity was measured by the MACBASS quantification program of the Fuji Phosphoimager (Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Activation of the p42/p44 MAPK Pathway Is Necessary for Inducing Nuclear Translocation of p42/p44 MAPK

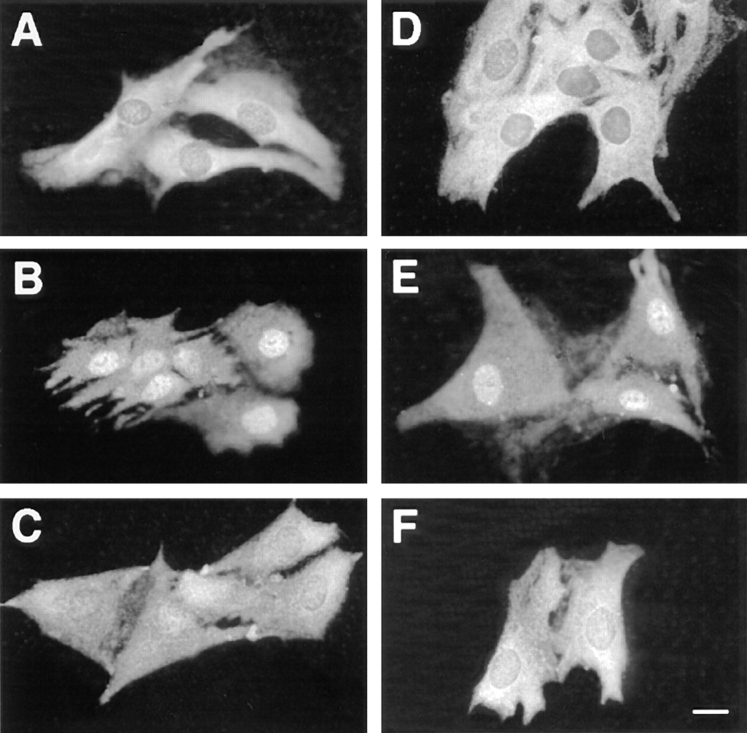

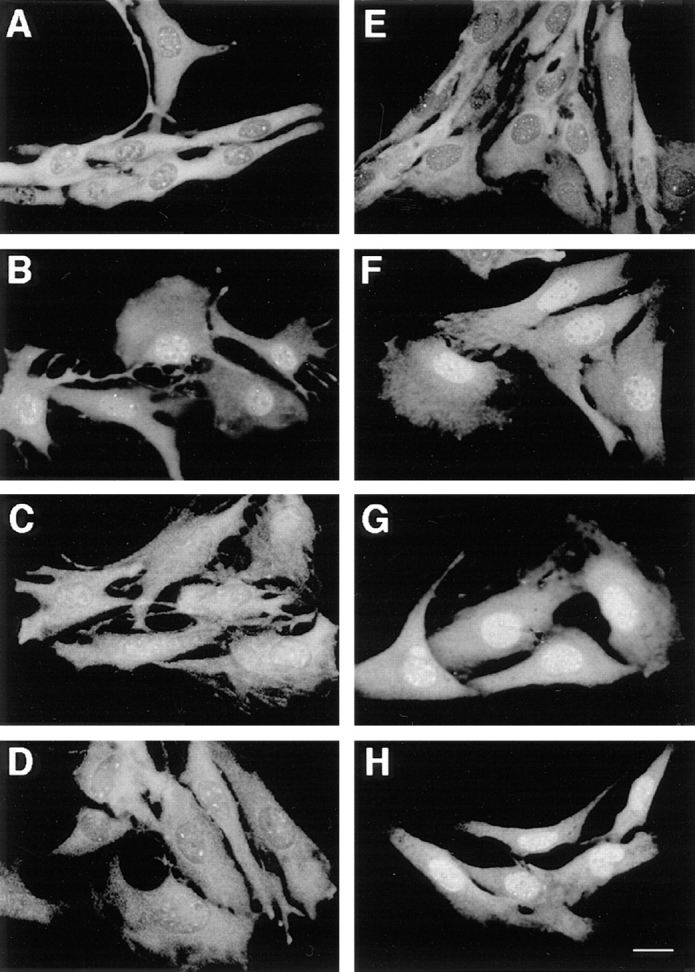

We previously reported that mitogenic stimulation of resting CCL39 cells led to a rapid nuclear translocation of MAPKs into the nucleus (27). Translocation into the nucleus correlated nicely with the persistent activation of MAPK during the G1 phase of the cell cycle. For example, serum or α-thrombin, two potent mitogens of CCL39 cells, induced persistent MAPK activation and nuclear localization. In contrast, the thrombin receptor peptide activator or TPA, which transiently activates MAPK, failed to induce nuclear translocation of MAPK (27). This result led us to postulate that the p42/p44 MAPK cascade itself controls the nuclear translocation of MAPK. Therefore, we tested whether addition of the specific MEK inhibitor PD 98059 (12) was sufficient to block the entry of p42/p44 MAPK in the nucleus in response to serum. This inhibitor has been previously shown to inhibit by up to 90% MAPK activation without affecting the activation of other MAPK cascades, such as the JNK and p38 MAPK pathways (2). In accordance to our and others' previous observations, p42/p44 MAPK immunostaining is predominantly cytoplasmic in serum-deprived cells (Fig. 1 A) and in cells treated by the MEK inhibitor PD 98059 alone (Fig. 1 D), whereas within 3 h of stimulation by 10% FCS, it is relocated markedly in the nucleus (Fig. 1 B). As depicted in Fig. 1 C, the addition of the MEK inhibitor PD 98059 (30 μM) at the time of serum addition was sufficient to block nuclear translocation of p42/p44 MAPK. As was reported by Alessi et al. (2) we found that MAPK activity was not totally inhibited by 30 μM of PD 98059 compound in CCL39 cells (up to 80% inhibition). This incomplete inhibition could explain why in certain cells some nuclear localization of p42/p44 MAPK remained. In these cells it is possible that MAPK stimulation by serum may be extremely potent. However, this result indicates that activation of the p42/p44 MAPK signaling cascade in response to serum is absolutely required for nuclear translocation of p42/p44 MAPK.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of the p42/p44 MAPK activity by PD 98059 suppresses MAPK nuclear translocation. CCL39 ΔRaf-1:ER cells were grown for 2 d on glass coverslides and serum-deprived for 24 h. Before fixation and p42/p44 MAPK immunolabeling, cells were treated as follows: (A) control cells were left unstimulated; (B) cells were stimulated for 3 h with 10% FCS; (C) cells were stimulated for 3 h with 10% FCS in the presence of 30 μM MEK inhibitor PD 98059; (D) cells were incubated 3 h in presence of 30 μM PD 98059; (E) cells were stimulated for 3 h with 1 μM estradiol; (F) cells were stimulated for 3 h with 1 μM estradiol in the presence of 30 μM PD 98059. For more details see Materials and Methods. Bar, 10 μm.

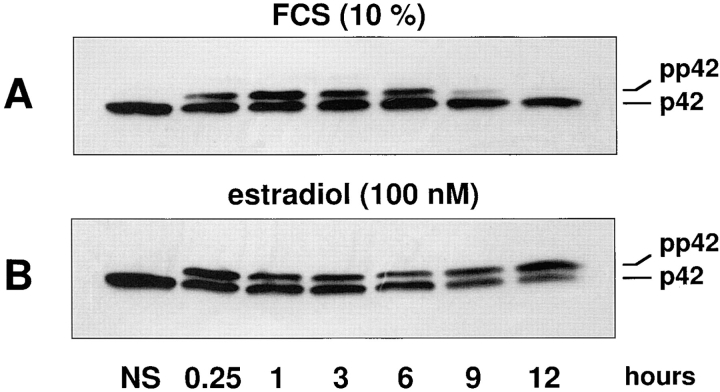

Persistent Activation of p42/p44 MAPK in Cells Expressing the ΔRaf-1:ER Chimera

To evaluate whether the sole activation of the p42/p44 MAPK signaling module is sufficient to promote nuclear translocation of p42/p44 MAPK, we have taken advantage of a fibroblastic cell line CCL39-ΔRaf-1:ER (28) stably expressing the chimera ΔRaf-1:ER (43, 44). Upon addition of β-estradiol to these cells, the Raf-1 kinase moiety of the chimera is unmasked and rapidly phosphorylates MEK, which in turn activates p42/p44 MAPK (28). As shown in Fig. 2 A, serum stimulation retards the electrophoretic mobility of p42 MAPK (due to phosphorylation). This activation observed after 15 min persists for up to 6 h, declines after 9 h, and is not detectable at 12 h when cells enter S-phase (Fig. 2 A). In sharp contrast, activation of the same cells with estradiol induces a gel mobility shift that persists as long as the cells are treated with estradiol (Fig. 2 B). In this experiment, only p42 MAPK is detected because of the specificity of the antibody used. However, activation of p44 MAPK (revealed with a less selective anti-MAPK antibody) parallels activation of p42 MAPK. The CCL39-ΔRaf-1:ER cell line offers two unique advantages. First, by its specific activation, downstream of Raf, estradiol exclusively turns on the p42/p44 MAPK module with no detectable activation of JNK or p38 MAPK within the first 16–24 h (33 and data not shown). Second, in contrast to serum activation that leads to the time-dependent desensitization of p42/p44 MAPK, β-estradiol induces a persistent p42/p44 MAPK activity. One can therefore easily manipulate the temporal activation of p42/p44 MAPK by adding β-estradiol or the MEK inhibitor PD 98059. It was therefore of interest to compare the p42/p44 MAPK translocation in cells stimulated with either serum or β-estradiol.

Figure 2.

p42 MAPK activation by serum is transient, whereas it is persistent when stimulating ΔRaf-1:ER by estradiol. ΔRaf-1: ER cells were stimulated by 10% FCS (A) or 100 nM estradiol (B) for different periods of time. p42 MAPK activation was monitored by electrophoretic mobility retardation in immunoblot studies. In lanes 2–7, CCL39 cells were stimulated for 15 min, 3 h, 6 h, 9 h, and 12 h, respectively. The lower band corresponds to inactive p42 MAPK, and the upper band corresponds to the phosphorylated (active) form of p42 MAPK.

Activation of the p42/p44 MAPK Signaling Pathway Is Sufficient to Promote the Nuclear Translocation of p42/p44 MAPK

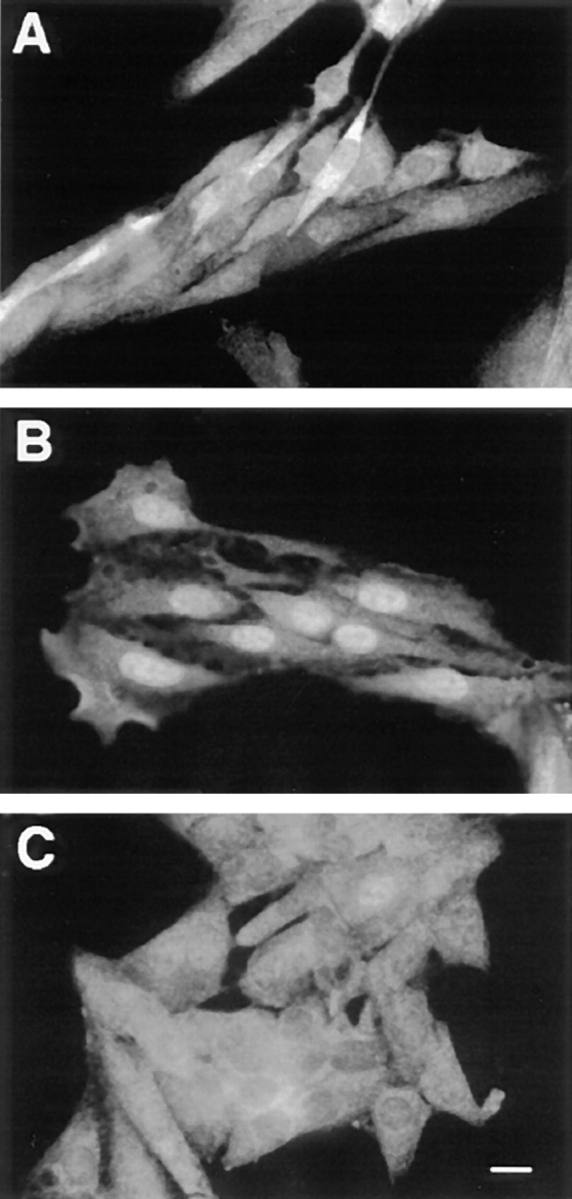

Fig. 3 depicts a typical time course of p42/p44 MAPK subcellular localization after stimulation of resting CCL39-ΔRaf-1:ER cells by either serum of β-estradiol. First, as illustrated in Fig. 3, A and E, the observed staining for p42/ p44 MAPK shows that in G0-arrested cells, p42/p44 MAPK immunolabeling was predominantly cytoplasmic, in accordance with our and other previously published results (8, 18, 27). Second, as judged by immunofluorescence microscopy, p42/p44 MAPK immunostaining underwent a complete redistribution in serum-stimulated cells, becoming almost exclusively nuclear after 3 h stimulation (Fig. 3 B). After 6 h of serum stimulation, p42/p44 MAPK immunostaining is uniformly distributed throughout the whole cell (Fig. 3 C). Finally, after 9 h of serum stimulation, p42/ p44 MAPK immunostaining was again predominantly cytoplasmic (Fig. 3 D). Interestingly, a 3-h stimulation of the ΔRaf-1:ER chimera by β-estradiol was sufficient to induce by itself the nuclear localization of p42/p44 MAPK (Fig. 3 F). In contrast to serum stimulation, activation of the ΔRaf-1:ER chimera prolonged the nuclear localization of p42/p44 MAPK for up to 6 h (Fig. 3 G) and 9 h (Fig. 3 H) after stimulation by β-estradiol. Furthermore, p42/p44 MAPK nuclear immunostaining was even detected after 15 h of ΔRaf-1:ER stimulation (data not shown). Later immunohistochemical observations were rendered more difficult because cells underwent rounding and detachment by the prolonged activation of this signaling cascade (35 and data not shown). As seen in response to serum, MAPK nuclear translocation initiated by activation of the ΔRaf-1:ER chimera was also abrogated in presence of the MEK inhibitor (Fig. 1, compare E and F).

Figure 3.

Time course of p42/p44 MAPK nuclear translocation parallels their temporal activation. CCL39-ΔRaf-1:ER cells were processed as described in Fig. 1. Cells were stimulated with 10% FCS for 3 h (B), 6 h (C), and 9 h (D) or with 100 nM β-estradiol for 3 h (F), 6 h (G), and 9 h (H). A and E represent unstimulated cells (control) in both sets of experiments. Bar, 10 μm.

The results presented above demonstrate that the sole activation of the p42/p44 MAPK signaling module is sufficient to promote the nuclear localization of p42/p44 MAPK. In addition, the nuclear localization of p42/p44 MAPK correlates well with the degree of activation of the p42/p44 MAPK pathway. As long as p42/p44 MAPK activity remains elevated, such as with long-term ΔRaf-1:ER stimulation, p42/p44 MAPK remains in the nucleus. On the contrary, if activation of the p42/p44 MAPK pathway decreases to unstimulated levels, as with long term serum stimulation, p42/p44 MAPK returns to the cytoplasm. We have shown previously that serum removal was sufficient to induce the efflux of p42/p44 MAPK from the nucleus within 1 h (27), a result consistent with the present observation.

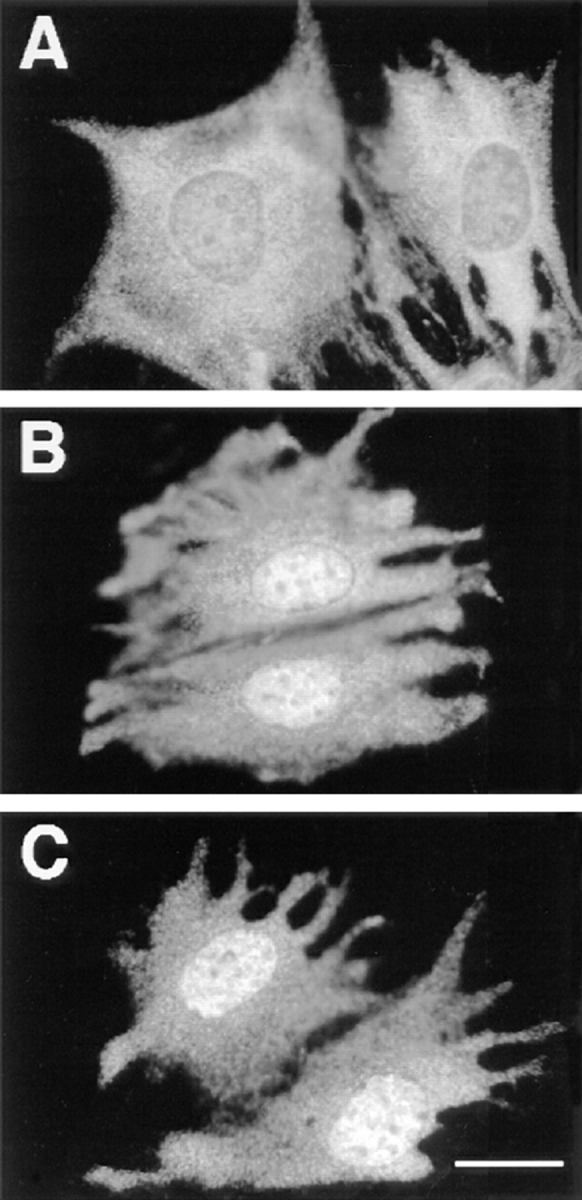

Neosynthesis of Proteins Is Required for p42/p44 MAPK Nuclear Retention

The results presented above indicated that activation of p42/p44 MAPK cascade was both required and sufficient for inducing p42/p44 MAPK nuclear translocation. p42/ p44 MAPK activation results from its dual phosphorylation by MEK (1, 10, 47). This reversible phosphorylation could explain the reversible nuclear localization of p42/ p44 MAPK. However, we and others have previously shown that nonphosphorylatable and inactive mutants of p42/p44 MAPK can still translocate into the nucleus. Thus, activation of p42/p44 MAPK must modify either its interactions with partner proteins and/or the cell physiology to induce nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK. First, we evaluated whether the activation of transcription induced by p42/p44 MAPK activation and the resulting neosynthesized proteins contribute to nuclear retention of MAPK. As illustrated in Fig. 4 C, inhibition of protein synthesis with 30 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) completely blocks the nuclear localization of p42/p44 MAPK after a 3-h serum stimulation (Fig. 4, compare B and C). Identical results were obtained when nuclear translocation of p42/p44 MAPK was induced with activation of the chimera ΔRaf-1:ER (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of protein synthesis by CHX suppresses MAPK nuclear accumulation. Parental CCL39 cells were grown on glass coverslides 2 d before a 24-h serum deprivation. Before fixation and p42/p44 MAPK immunolabeling, as described in Materials and Methods, (A) control cells were left unstimulated, (B) cells were stimulated with 10% FCS for 3 h, (C) cells were treated with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (30 μg/ml), and 15 min later were stimulated with 10% FCS for 3 h in continuous presence of CHX. Bar, 10 μm.

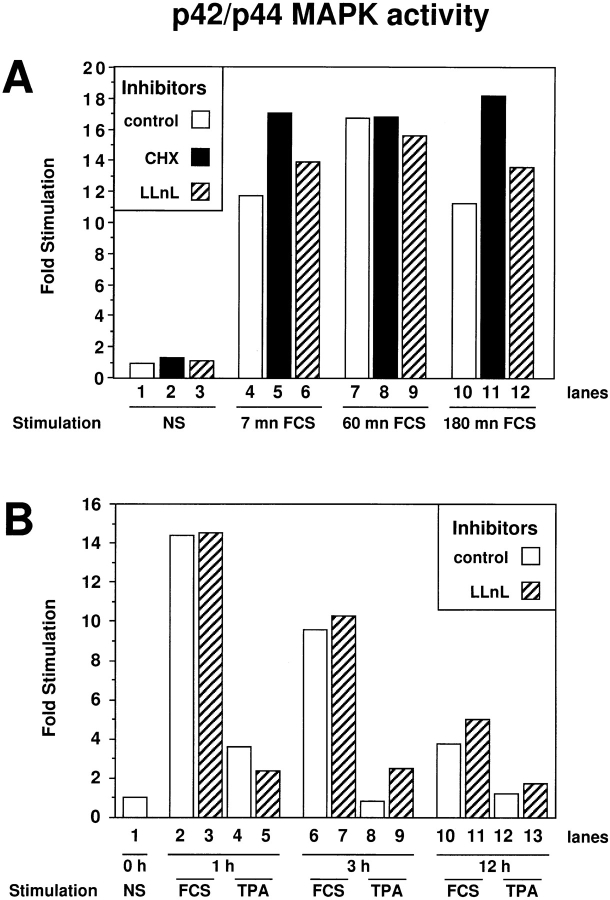

We demonstrated that the activation of the MAPK pathway closely parallels to the nuclear translocation of p42/p44 MAPK; therefore, it was essential to verify that CHX did not abrogate p42/p44 MAPK activity, since this would explain the inhibition of nuclear translocation.

Addition of CHX to serum-stimulated CCL39 cells did not modify the activity (Fig. 5) nor the levels of p42/p44 MAPK (data not shown). Indeed, CHX treatment did not affect serum stimulation of p42/p44 MAPK measured at 7 min (compare lanes 4 and 5) or at 60 min (compare lanes 7 and 8). CHX treatment even enhanced activation of p42/ p44 MAPK at 3 h (compare lanes 10 and 11), which is in accordance to previous observations (7). The prolongation of MAPK activation by CHX treatment may be a consequence of blocking the inducible expression of specific MAPK phosphatases of the MKP family: MKP-1 (45), MKP-2 (20, 34), and MKP-3 (19, 36). Thus, the inhibition of p42/p44 MAPK nuclear translocation by CHX treatment, observed in Fig. 4, cannot be attributed to inhibition of the p42/p44 MAPK signaling pathway. Furthermore, we were able to rule out the possibility that CHX exerted its action via nonspecific effects since inhibition of protein synthesis by 100 ng/ml anisomycin and inhibition of transcription by 5 μg/ml actinomycin D also prevented p42/ p44 MAPK nuclear localization after serum or ΔRaf-1:ER chimera stimulation (data not shown). In addition, we ruled out a possible effect of CHX via activation of JNK/ p38 stress-activated protein kinases (SAPK) by showing that IL1-β or low concentrations of anisomycin (two potent activators of SAPKs) did not change the nuclear accumulation of MAPKs in response to serum. Finally, by analyzing the localization of the transcription factor SP1, MEK, or a nuclear form of MEK (NLS:MEK), we ruled out unspecific effects of CHX on the nuclear import/export of proteins in general (data not shown). Taken together, these experiments clearly demonstrate that the transcriptional stimulation driven by p42/p44 MAPK activation and the resulting protein neosynthesis are absolutely required for the nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK observed after 1–3 h of mitogenic stimulation.

Figure 5.

p42/p44 MAPK activity is prolonged when protein synthesis is blocked by CHX and unaffected when the proteasome function is blocked by LLnL. Activity of immunoprecipitated p42/p44 MAPK was analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. MAPK activity is expressed as fold stimulations over basal activity. (A) Lane 1, CCL39 cells were left untreated; lanes 2 and 3, cells were treated with CHX and LLnL, respectively, for 3 h; lanes 4–6, cells were stimulated 7 min with 10% FCS; lanes 7–9, cells were stimulated for 1 h with 10% FCS; lanes 10–12, cells were stimulated for 3 h with 10% FCS. CHX (30 μg/ml) was added 15 min before FCS in lanes 5, 8, and 11 (black bars). LLnL (30 μM) was added 15 min before FCS in lanes 6, 9, and 12 (hatched bars). (B) (Separate experiment) Lane 1, CCL39 cells were left untreated; lanes 2 and 3, cells were stimulated for 1 h with 10% FCS; lanes 4 and 5, cells were stimulated 1 h with 100 ng/ml TPA; lanes 6 and 7, cells were stimulated for 3 h with 10% FCS; lanes 8 and 9, cells were stimulated for 3 h with 100 ng/ml TPA; lanes 10 and 11, cells were stimulated for 12 h with 10% FCS; lanes 12 and 13, cells were stimulated for 12 h with 100 ng/ ml TPA. LLnL (30 μM) was added 15 min before FCS or TPA in lanes 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13 (hatched bars).

Inhibition of Protein Synthesis Triggers the Exit of p42/p44 MAPK from the Nucleus

We have shown previously that terminating MAPK stimulation by rapid removal of serum growth factor induced the efflux of nuclear p42/p44 MAPK to the cytoplasm within 1 h (27). In light of the experiments described in Fig. 4, which demonstrate that protein neosynthesis is required for the nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK, we formulate the hypothesis that the nuclear efflux induced by serum removal is caused by a decrease in the synthesis of proteins associated with p42/p44 MAPK in the nucleus (nuclear anchors). Therefore, we predict that inhibition of protein synthesis should accelerate MAPK efflux from the nucleus.

Fig. 6, B and C, show the localization of p42/p44 MAPK after 3 and 5 h of serum stimulation, respectively. In both cases, MAPKs are clearly accumulated in the nucleus with perhaps a less intense signal at 5 h (Fig. 6 C) because of a decline in p42/p44 MAPK activity. However, the inhibition of protein synthesis with CHX for the last 2 h of serum stimulation markedly accelerated the cytoplasmic return of p42/p44 MAPK (Fig. 6, compare C and E). This acceleration of MAPK nuclear efflux was already apparent 1 h after CHX addition (Fig. 6 D).

Figure 6.

Inhibition of protein synthesis triggers the rapid nuclear efflux of p42/p44 MAPK. Parental CCL39 cells were grown on glass coverslides and p42/p44 MAPK immunolabeling was performed as described in Fig. 1, except that before fixation (A) control cells were left untreated; (B) cells were stimulated for 3 h with 10% FCS; (C) cells were stimulated for 5 h with 10% FCS; (D) cells were stimulated for 3 h with 10% FCS, and then 30 μg/ ml CHX was added for 1 h; (E) cells were stimulated for 3 h with 10% FCS and then 30 μg/ml CHX was added for 2 h. Bar, 10 μm.

Similarly, when CCL39-ΔRaf-1:ER cells were stimulated by β-estradiol, which induced a persistent activation and nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK (as shown in Fig. 3), addition of CHX was sufficient to trigger the efflux of p42/p44 MAPK from the nucleus (data not shown). As CHX treatment did not abrogate (and even slightly enhanced) p42/p44 MAPK activation, we conclude that continuous protein synthesis is required to retain p42/p44 MAPK in the nucleus.

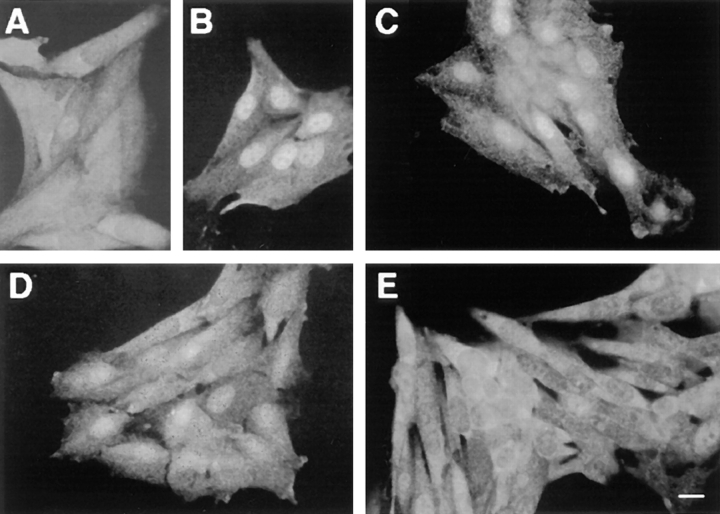

Inhibition of the Proteasome-dependent Protein Degradation Pathway Promotes Nuclear Accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK

The experiments presented above led us to propose that activation of the p42/p44 MAPK pathway triggers the neosynthesis of short-lived proteins that contribute to the nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK. A prediction of this proposal is that the stabilization of short-lived proteins should prolong the nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK.

Many short-lived proteins have been found to be targeted and degraded by the proteasome after their ubiquitinylation (39). Thus, to validate this hypothesis we inhibited the activity of the proteasome with LLnL, a membrane-permeable inhibitor of cysteine proteases that acts upon calpains and proteasomes (42, 46). The action of LLnL on p42/p44 MAPK subcellular localization was assessed after long-term serum stimulation.

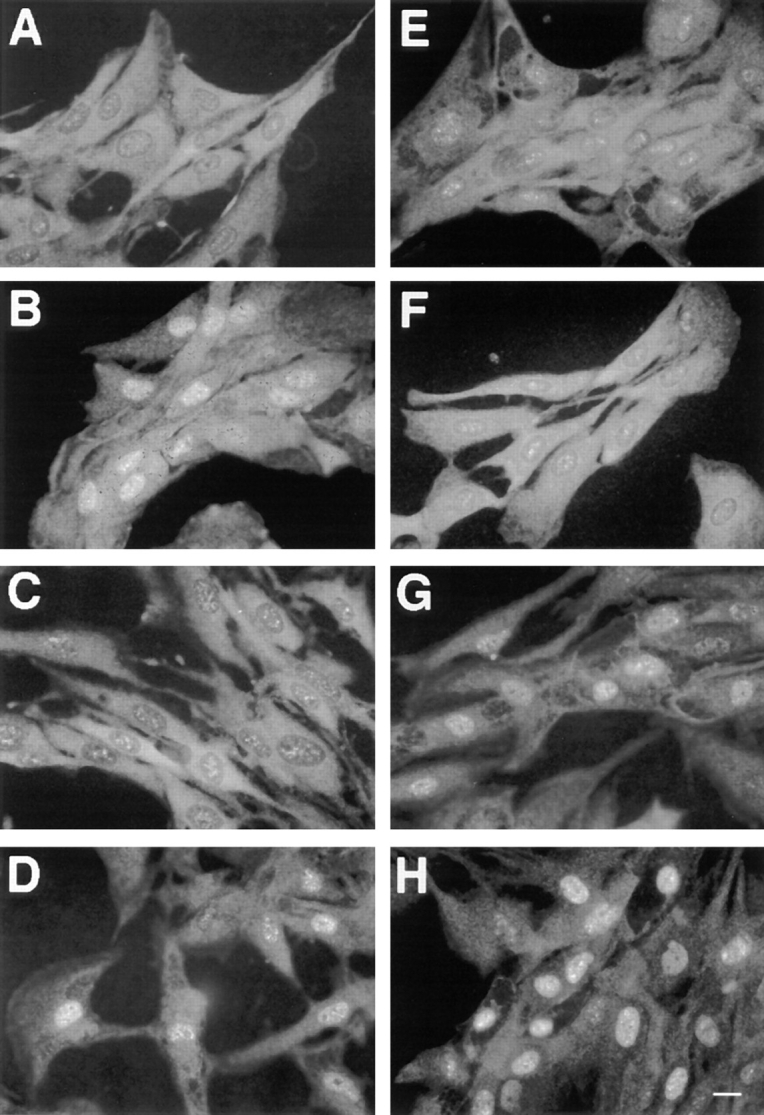

Fig. 7 recapitulates a typical immunolocalization of p42/ p44 MAPK. Mainly cytoplasmic in G0-arrested cells (Fig. 7 A), MAPKs display a clear nuclear localization after 3 h of stimulation with 10% FCS (Fig. 7 B) and return almost completely in the cytoplasm after 12 h when cells are beginning to enter S-phase (Fig. 7 C). In a parallel set of stimulated cells, addition of the proteasome inhibitor LLnL (30 μM), for 12 h, markedly prevented nuclear MAPK efflux (Fig. 7, compare D with C). In addition, if mitogenic stimulation was ended upon serum removal after 3 h and the cells were incubated for another 9 h in a serum-free medium containing the LLnL, the nuclear localization of p42/p44 MAPK was maintained (Fig. 7 H). We have previously shown that p42/p44 MAPK activity in exponentially growing cells is completely abolished after a 3-h serum removal (our unpublished results). Our results indicate that p42/p44 MAPK nuclear retention can be observed while MAPK activation is totally abrogated, provided that the targeted degradation of proteins is halted. Furthermore, we have previously shown that activation of CCL39 cells by nonmitogenic stimuli was not sufficient to promote nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK (27). For example, TPA, which is not mitogenic for CCL39 cells, does not induce any redistribution of MAPKs in the nucleus (Fig. 7 F). Surprisingly, blocking protein degradation by addition of LLnL during TPA stimulation for 12 h, triggered the nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK (Fig. 7, compare G and F). Interestingly, the nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK observed when cells were exposed to both TPA and LLnL was delayed as compared with that obtained with mitogenic stimulation (starting at ∼6 h, data not shown). For all the experiments presented here, it is important to note that LLnL alone is not able to stimulate p42/p44 MAPK activity nor alter the magnitude and temporal profile of stimulated MAPKs by serum (Fig. 5 A, lanes 6, 9, and 12 and Fig. 5 B, lanes 3, 7, and 11) or upon addition of TPA (Fig. 5 B, lanes 5, 9, and 12). Thus, any action of LLnL on the subcellular localization of p42/p44 MAPK cannot be attributed to the modification of MAPK activity. Furthermore, treatment with LLnL alone does not change the cytoplasmic localization of MAPKs in resting cells (Fig. 7 E). To verify that LLnL does not alter the general mechanism of nuclear import/export, treatment with LLnL for 12 h in presence of serum does not modify the subcellular localization of MEK or of the transcription factor SP1 (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Inhibition of the proteasome-prolonged serum-induced MAPK nuclear translocation. Parental CCL39 cells were grown on glass coverslides, and p42/p44 MAPK immunolabeling was performed as described in Fig. 1, except that before fixation (A) control cells were left untreated; (B) cells were stimulated for 3 h with 10% FCS; (C) cells were stimulated for 12 h with 10% FCS; (D) cells were stimulated for 12 h with 10% FCS in presence of 30 μM of the proteasome inhibitor LLnL; (E) serum-deprived cells were grown for 12 h in the presence of 30 μM of LLnL; (F) cells were stimulated for 12 h with 100 ng/ml of TPA; (G) cells were stimulated for 12 h 100 ng/ml of TPA in the presence of 30 μM of LLnL; (H) cells were stimulated for 3 h with 10% FCS, washed three times, and incubated for 9 h in serum-free medium in the presence of 30 μM of LLnL. Bar, 10 μm.

To further eliminate the possibility of nonspecific effect(s) of LLnL, treatment with lactacystin (Fig. 8 C) mimics the action of LLnL (Fig. 8 B). LLnL is a reversible and slow-binding inhibitor that blocks proteasome function and calpain proteases (46), whereas lactacystin, a compound shown to be a more specific proteasome inhibitor, alkylates irreversibly threonine 1 of the active β subunit of the proteasome (11, 13).

Figure 8.

Inhibition of the proteasome by either LLnL or lactacystin prolonged serum-induced MAPK nuclear translocation. Parental CCL39 cells were grown on glass coverslides, and p42/p44 MAPK immunolabeling was performed as described in Fig. 1, except that before fixation (A) cells were stimulated 9 h with 10% FCS; (B) cells were stimulated for 9 h with 10% FCS in the presence of 30 μM of LLnL; (C) cells were stimulated for 9 h with 10% FCS in the presence of 10 μM lactacystin. Bar, 10 μm.

Taken together, these results show the specific implication of newly synthesized proteins in the process of nuclear retention of p42/p44 MAPK and demonstrates that these nuclear anchor(s), which retain MAPKs in the nucleus, are finely regulated by the proteasome system.

Discussion

The MAPK cascade constitutes a functional signaling unit that links surface receptor–mediated signals to nuclear events. It is interesting that among the six to eight sequential components of this cascade, only p42 and p44 MAPKs, the most downstream elements, possess the unique potential to shuttle between the cytoplasm and the nucleus. This nuclear translocation was observed in virtually all cell types in culture (fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, mesangial cells, epithelial cells, PC12 cells, neurons), occurring in response to either potent mitogenic stimuli, differentiating agents, or depolarizing agents (8, 9, 18, 24, 27, 30, 32, 37). Although we believe that this regulatory mechanism is central to set the spatiotemporal activity of MAPKs and therefore their biological function, the mechanism by which MAPKs translocate to the nucleus upon stimulation is largely unknown.

In resting cells, p42/p44 MAPK are retained in the cytoplasm, presumably via a cytoplasmic anchoring complex. This notion is based on three findings: (a) Overexpression of either p42 or p44 MAPK leads to a spontaneous leakage of MAPK to the nucleus in the absence of stimuli (27). We interpreted this finding as a saturation of the cytoplasmic anchor. (b) MEK, the upstream activator of p42/p44 MAPK, is permanently excluded from the nucleus by a leucine-rich short sequence, which acts as a nuclear export signal (14, 23). (c) Thorner and colleagues have highlighted the existence of a specific p42/p44 MAPK docking site at the extreme NH2 terminus of MEK, a site conserved from yeast to human (3). Based on these observations, we hypothesized that MEK might represent a good candidate for being part of a MAPK cytoplasmic anchoring complex, a notion that has been largely substantiated by Fukuda et al. (15).

In this report, we have been able to identify the signal triggering MAPK nuclear translocation and its dissociation from the putative cytoplasmic anchor, and the process that regulates MAPK nuclear retention. The signal required to initiate MAPK nuclear translocation is clearly the activation of the p42/p44 MAPK module. This was best demonstrated by the use of the ΔRaf-1:ER–expressing cells. Activation of the module downstream of Raf alone is sufficient to initiate MAPK nuclear stimulation. This translocation is rapid since in most experiments, entry into the nucleus can be observed as early as 10 min after stimulation (our unpublished results), and more importantly, this action does not require new protein synthesis. These findings were best visualized by using antibodies specifically recognizing the doubly phosphorylated and thus active form of MAPK. Entry into the nucleus of active p42/p44 MAPK is seen as soon as 5 min after serum stimulation (data not shown). This result confirms and extends the observations of Fukuda et al. (15), demonstrating the nuclear localization of Xenopus MAPK when injected in conjunction with constitutively active MEK or v-Ras. More recently, MAPK was also shown to be constitutively nuclear in Ras-transformed cells (5).

How p42 and p44 MAPKs dissociate from the cytoplasmic anchoring complex upon activation and enter the nucleus is not entirely clear. One interesting idea proposed by Seger's group (23) is that upon serum stimulation, the MEK–MAPK complex translocates to the nucleus where, following dissociation, only MEK is rapidly excluded via its active nuclear export signal sequence. Alternatively, the model we favor, also proposed by Fukuda et al. (15), is a rapid dissociation of MAPK in the cytoplasm after retrophosphorylation of the anchoring complex via p42/p44 MAPK. Subsequent to this dissociation, MAPKs could easily translocate to the nucleus via simple diffusion, as illustrated by Nishida's group (15), although a cotransport involving association of MAPKs with their NLS-containing substrates cannot be excluded. This model is not in contradiction with a previous observation that we and others have made concerning the ability of nonphosphorylatable mutants of p42/p44 MAPK to translocate to the nucleus upon mitogenic stimulation (18, 27). Under these circumstances, the endogenous MAPK activity is still capable of regulating the dissociation of the inactive kinase from the cytoplasmic complex. Alternatively, a third model has been recently presented by Khokhlatchev et al. (26). The authors propose that phosphorylation of Erk2 (p42 MAPK) promotes its homodimerization and nuclear translocation. Although interesting, this model based on microinjection studies in fibroblasts awaits validation in vivo by an independent approach.

In contrast to the rapid process of MAPK dissociation from the cytoplasmic anchoring complex and nuclear entry, the events leading to p42/p44 MAPK nuclear retention do require new protein synthesis. This process that develops slowly with time also depends upon activation of the p42/p44 MAPK module. Indeed, MAPK nuclear retention mirrors the temporal activation of p42/p44 MAPK. This is best demonstrated by comparing serum with estradiol stimulation. The strong and persistent activation of the MAPK module attained with estradiol in ΔRaf-1:ER cells led to a massive and persistent MAPK nuclear retention. Under these conditions, an arrest of protein synthesis by CHX is sufficient to provoke an efflux of nuclear MAPK, although the MAPK module remains fully active. Another example of disjunction between MAPK activation and nuclear retention was obtained by inhibiting the proteasome. Under conditions where MAPK is transiently stimulated (TPA, serum during short pulses), MAPK does not accumulate in the nucleus. However, if protein degradation of short-lived proteins is inhibited by proteasome inhibitors, then MAPK nuclear retention is observed. This process is slower than with a physiological stimulation with serum, but the amplitude of nuclear retention is comparable (see Figs. 7 and 8). Interestingly, under these conditions of proteasome inhibition, MAPK activity is barely detectable, and yet MAPK nuclear retention is maximal (see Fig. 5). Therefore, when protein degradation is inhibited, it seems that MAPK nuclear retention occurs independently of MAPK-dependent phosphorylating events. Interestingly, the only reported case where p42/p44 MAPK nuclear translocation can occur regardless of its activation was in REF52 cells treated with thiol-modifying agents such as phenylarsine oxide and N-ethylmaleimide (31). Considering that N-ethylmaleimide is known to inhibit one peptidase activity of the proteasome by acting on a critical cysteinyl residue (11, 22), this agent could trigger, in some cells, the nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK by blocking the degradation of MAPK nuclear anchors.

We interpret our data by proposing that activation of the p42/p44 MAPK module leads to the neosynthesis of a MAPK nuclear anchor protein(s). This MAPK nuclear anchor protein(s) is rapidly synthesized upon activation of the p42/p44 MAPK module and has a very short half-life (estimated ∼1 hour). What may be the nature of this nuclear anchor protein(s)? It has the characteristic of an immediate early gene product, and it could well represent a set of transcription factors, substrates of p42/p44 MAPK, that have the capacity to accumulate in the nucleus and to physically interact with their signaling kinases. On the other hand, the MAPK-specific phosphatases, MKP-1 and MKP-2, represent another set of nuclear proteins, which are newly synthesized under the control of p42/p44 MAPK activity (7) and which share the features of a MAPK anchoring system. Alternatively, and perhaps more appealing, the MAPK nuclear anchor might represent a specific component of the MAPK cascade that, in view of long-term signaling, has evolved to address a pool of active MAP kinase in the nucleus. In fact, signals that trigger the nuclear accumulation of p42/p44 MAPK may not be mitogenic ones, but in all cases they convey long-term activation of p42/p44 MAPK. This is the case for differentiation of PC12 cell (9, 37) and for long-term facilitation of presynaptic cells in Aplysia (30). Alternatively, the pool of MAPKs in the nucleus could progressively become inactivated by the emergence of the nuclear MKPs. If this is the case, then MAPK nuclear retention could be an efficient mechanism of signal desensitization, by sequestering MAPK out of the cytoplasmic-activating complex. Indeed, nonphosphorylatable and inactive mutated forms of MAPK can accumulate into the nucleus (18, 27), providing an indication that inactive MAPK can bind to the nuclear anchor(s).

One of the next steps in our future investigation of MAPK nuclear signaling will clearly be the identification of the nuclear anchoring components and the analysis of the MAPK activity from the nuclear pool. Here we have established a set of conditions that should help to evaluate among positive “MAPK interactors” obtained from purification or by two hybrid screens, those specific components that contribute to MAPK nuclear retention.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Darren Richard for carefully reading the manuscript, Dominique Grall for efficient assistance in cell culture and all the members of the laboratory for fruitful discussions, and Y. Fantei for excellent computer assistance and computer graphics.

This work was supported by research grants from Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), the University of Nice, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Medicale (INSERM), Association pour la Recherche centre le Cancer (ARC), and from the Ligue Nationale de la Recherche centre le Cancer.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- CHX

cycloheximide

- ERK

extra cellular regulated kinase

- JNK

Jun NH2-terminal Kinase

- LLnL

N-Acetyl-Leu-Leu-norLeucinal

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MEK

MAPK or Erk kinase

- NLS

nuclear localization signal

- PD 98059

Park Davis 98059

- TPA

12-O-tetra decanoyl phorbol myristate acetate

Footnotes

References

- 1.Ahn NG, Seger R, Krebs EG. The mitogen-activated protein kinase activator. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1992;4:992–999. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(92)90131-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alessi DR, Cuenda A, Cohen P, Dudley DT, Saltiel AR. PD 098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and in vivo. . J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27489–27494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardwell L, Cook JG, Chang EC, Cairns BR, Thorner J. Signaling in the yeast pheromone response pathway: specific and high- affinity interaction of the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases Kss1 and Fus3 with the upstream MAP kinase kinase Ste7. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3637–3650. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumeister W, Lupas A. The proteasome. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:273–278. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjorkoy G, Perander M, Overvatn A, Johansen T. Reversion of Ras- and phosphatidylcholine-hydrolyzing phospholipase C-mediated transformation of NIH 3T3 cells by a dominant interfering mutant of protein kinase C lambda is accompanied by the loss of constitutive nuclear mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11557–11565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boulton TG, Nye SH, Robbins DJ, Ip NY, Radziejewska E, Morgenbesser SD, DePinho RA, Panayotatos N, Cobb MH, Yancopoulos GD. ERKs: a family of protein-serine/threonine kinases that are activated and tyrosine phosphorylated in response to insulin and NGF. Cell. 1991;65:663–675. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90098-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brondello JM, Brunet A, Pouyssegur J, McKenzie FR. The dual specificity mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 and -2 are induced by the p42/p44MAPK cascade. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1368–1376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen TH, Sarnecki C, Blenis J. Nuclear localization and regulation of ERK- and RSK-encoded protein kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:915–927. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowley S, Paterson H, Kemp P, Marshall CJ. Activation of MAP kinase kinase is both necessary and sufficient for PC12 differentiation and for transformation of NIH 3T3 cells. Cell. 1994;77:841–852. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crews CM, Alessandrini A, Erikson RL. The primary structure of MEK, a protein kinase that phosphorylates the ERK gene product. Science. 1992;258:478–480. doi: 10.1126/science.1411546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dick LR, Moomaw CR, Pramanik BC, DeMartino GN, Slaughter CA. Identification and localization of a cysteinyl residue critical for the trypsin-like catalytic activity of the proteasome. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7347–7355. doi: 10.1021/bi00147a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dudley DT, Pang L, Decker SJ, Bridges AJ, Saltiel AR. A synthetic inhibitor of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7686–7689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fenteany G, Standaert RF, Lane WS, Choi S, Corey EJ, Schreiber SL. Inhibition of proteasome activities and subunit-specific amino-terminal threonine modification by lactacystin. Science. 1995;268:726–731. doi: 10.1126/science.7732382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukuda M, Gotoh I, Gotoh Y, Nishida E. Cytoplasmic localization of MAP kinase kinase directed by its N-terminal, leucin-rich amino acid sequence, which acts as a nuclear export signal. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20024–20028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuda M, Gotoh Y, Nishida E. Interaction of MAP kinase with MAP kinase kinase: its possible role in the control of nucleocytoplasmic transport of MAP kinase. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1997;16:1901–1908. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gille H, Sharrocks AD, Shaw PE. Phosphorylation of transcription factor p62TCF by MAP kinase stimulates ternary complex formation at c-fospromoter. Nature. 1992;358:414–424. doi: 10.1038/358414a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gille H, Kortenjann M, Thomae O, Moomaw C, Slaughter C, Cobb MH, Shaw PE. ERK phosphorylation potentiates Elk-1-mediated ternary complex formation and transactivation. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1995;14:951–962. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez FA, Seth A, Raden DL, Bowman DS, Fay FS, Davis RJ. Serum-induced translocation of mitogen-activated protein kinase to the cell surface ruffling membrane and the nucleus. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:1089–1101. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.5.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groom LA, Sneddon AA, Alessi DR, Dowd S, Keyse SM. Differential regulation of the MAP, SAP and RK/p38 kinases by Pyst1, a novel cytosolic dual-specificity phosphatase. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1996;15:3621–3632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guan KL, Butch E. Isolation and characterization of a novel dual specific phosphatase, HVH2, which selectively dephosphorylates the mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7197–7203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hipskind RA, Baccarini M, Nordheim A. Transient activation of Raf-1, MEK and ERK2 coincides kinetically with ternary complex factor phosphorylation and immediate-early gene promoter activity in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6219–6231. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffman L, Rechsteiner M. Nucleotidase activities of the 26 S proteasome and its regulatory complex. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32538–32545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaaro H, Rubinfeld H, Hanoch T, Seger R. Nuclear translocation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK1) in response to mitogenic stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3742–3747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaffa AA, Miller BS, Rosenzweig SA, Naidu PS, Velarde V, Mayfield RK. Bradykinin induces tubulin phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of MAP kinase in mesangial cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:F916–F924. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.273.6.F916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson GL, Vaillencourt RR. Sequential protein kinase reactions controlling cell growth and differentiation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:230–238. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khokhlatchev AV, Canagarajah B, Wilsbacher J, Robinson M, Atkinson M, Goldsmith E, Cobb MH. Phosphorylation of the MAP kinase ERK2 promotes its homodimerization and nuclear translocation. Cell. 1998;93:605–615. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lenormand P, Sardet C, Pagès G, L'Allemain G, Brunet A, Pouysségur J. Growth factors induce nuclear translocation of MAP kinases (p42mapk and p44mapk) but not of their activator MAP kinase kinase (p45mapkk) in fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:1079–1089. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.5.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lenormand P, McMahon M, Pouysségur J. Oncogenic Raf-1 activates p70 S6 kinase via a mitogen-activated protein kinase-independent pathway. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15762–15768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marais R, Wynne J, Treisman R. The SRF accessory protein Elk-1 contains a growth factor-regulated transcriptional activation domain. Cell. 1993;73:381–393. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90237-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin KC, Michael D, Rose JC, Barad M, Casadio A, Zhu H, Kandel ER. MAP kinase translocates into the nucleus of the presynaptic cell and is required for long-term facilitation in Aplysia. Neuron. 1997;18:899–912. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meili R, Ballmer HK. Activation-independent nuclear translocation of mitogen activated protein kinase ERK1 mediated by thiol-modifying chemicals. FEBS Lett. 1996;394:34–38. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00927-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mii S, Khalil RA, Morgan KG, Ware JA, Kent KC. Mitogen-activated protein kinase and proliferation of human vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H142–H150. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.1.H142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minden A, McMahon M, Lange-Carter C, Dérijar B, Davis RJ, Johnson GL. Differential activation of ERK and JNK by Raf-1 and MEKK. Science. 1994;266:1719–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.7992057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Misra-Press A, Rim CS, Yao H, Roberson MS, Stork PJ. A novel mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase. Structure, expression, and regulation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14587–14596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moriguchi T, Gotoh Y, Nishida E. Activation of two isoforms of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in response to epidermal growth factor and nerve growth factor. Eur J Biochem. 1995;234:32–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.032_c.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muda M, Boschert U, Dickinson R, Martinou JC, Martinou I, Camps M, Schlegel W, Arkinstall S. MKP-3, a novel cytosolic protein-tyrosine phosphatase that exemplifies a new class of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4319–4326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen TT, Scimeca JC, Filloux C, Peraldi P, Carpentier JL, Van OE. Co-regulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1, and the 90-kDa ribosomal S6 kinase in PC12 cells. Distinct effects of the neurotrophic factor, nerve growth factor, and the mitogenic factor, epidermal growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9803–9810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nigg EA. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: signals, mechanisms and regulation. Nature. 1997;386:779–787. doi: 10.1038/386779a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pahl HL, Baeuerle PA. Control of gene expression by proteolysis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:340–347. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pante N, Aebi U. Sequential binding of import ligands to distinct nucleopore regions during their nuclear import. Science. 1996;273:1729–1732. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5282.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robinson MJ, Cobb MH. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:180–186. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rock KL, Gramm C, Rothstein L, Clark K, Stein R, Dick L, Hwang D, Goldberg AL. Inhibitors of the proteasome block the degradation of most cell proteins and the generation of peptides presented on MHC class I molecules. Cell. 1994;78:761–771. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samuels ML, McMahon M. Inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor- and epidermal growth factor-mediated mitogenesis and signaling in 3T3 cells expressing delta Raf-1:ER, an estradiol-regulated form of Raf-1. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7855–7866. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.7855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samuels ML, Weber MJ, Bishop M, McMahon M. Conditional transformation of cells and rapid activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade by an estradiol-dependent human raf-1 protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6241–6252. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun H, Charles CH, Lau LF, Tonks NK. MKP-1 (3CH134), an immediate early gene product, is a dual specificity phosphatase that dephosphorylates MAP kinase in vivo. Cell. 1993;75:487–493. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vinitsky A, Michaud C, Powers JC, Orlowski M. Inhibition of the chymotrypsin-like activity of the pituitary multicatalytic proteinase complex. Biochemistry. 1992;31:9421–9428. doi: 10.1021/bi00154a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng C-F, Guan K-L. Cloning and characterization of two distinct human extracellular signal-regulated kinase activator kinases, MEK1 and MEK2. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11435–11439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng C-F, Guan K-L. Cytoplasmic localization of the mitogen-activated protein kinase activator MEK. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19947–19952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]