Abstract

Background

Poor adherence with inhaled corticosteroids is an important problem in asthma management. Previous approaches to improving adherence have had limited success.

Aim

To determine whether treatment with a single inhaler containing a long-acting β2-agonist and a corticosteroid for maintenance treatment and symptom relief can overcome the problem of poor adherence with inhaled corticosteroids.

Design of study

Randomised, parallel group, open-label trial.

Setting

Forty-four general practices in Nottinghamshire.

Method

Participants who used less than 70% of their prescribed dose of inhaled corticosteroid and had poorly controlled asthma were randomised to budesonide 200 μg one puff twice daily plus their own short-acting β2-agonist as required (control group), or budesonide/formoterol 200/6 μg one puff once daily and as required (active group) for 6 months. The primary outcome was inhaled corticosteroid dose.

Results

Seventy-one participants (35 control, 36 active group) were randomised. Adherence with budesonide in the control group was approximately 60% of the prescribed dose. Participants in the active group used approximately 80% more budesonide than participants in the control group (448 versus 252 μg/day, mean difference 196 μg, 95% confidence interval 113 to 279; P<0.001) and were less likely to withdraw from the study (3 versus 13; P<0.01). No safety issues were identified.

Conclusion

Using a single inhaler for both maintenance treatment and symptom relief approximately doubled the dose of inhaled corticosteroid taken, suggesting this could be a useful strategy to overcome the problems related to poor adherence with inhaled corticosteroids.

Keywords: asthma, budesonide, formoterol, inhaled corticosteroids, patient-non-adherence

INTRODUCTION

Poor adherence with inhaled corticosteroids is a major problem in asthma management,1–3 occurring in 30–60% of patients.4–6 Reasons for poor adherence are numerous, but include a dislike of inhaled corticosteroids, lack of rapid symptom relief, and complicated treatment regimens.7–9

Because the β2-agonist formoterol has a rapid onset and long duration of action,10 it can be used for symptom relief and maintenance treatment.11–13 When combined with budesonide in a single inhaler and used in this way it simplifies asthma treatment and provides a dose of inhaled corticosteroid with every dose of relief medication. Recent large multicentre studies show that this single-inhaler approach improves asthma control compared with a higher dose of inhaled corticosteroid,14–16 or an equivalent or higher dose of a combined long-acting β2-agonist and corticosteroid used for maintenance treatment only.16–19 The same approach may be particularly useful in patients who have poor adherence with inhaled corticosteroids because they would be unable to use a β2-agonist without taking an inhaled corticosteroid at the same time. For these patients the aim would be to increase the dose of inhaled corticosteroid taken.

This research was a pragmatic, parallel group, feasibility study to determine whether the underuse of inhaled corticosteroids by patients who are poorly adherent could be overcome by using a single inhaler containing budesonide and formoterol once daily and as required. The study had to be open-label as the specific focus of the study was to determine the effects of patients having only one inhaler, and a double-blind study would have required a double-dummy design and, therefore, two inhalers. Interventions during the study were limited to minimise the effect that being in the study had on patient adherence.

METHOD

Participants

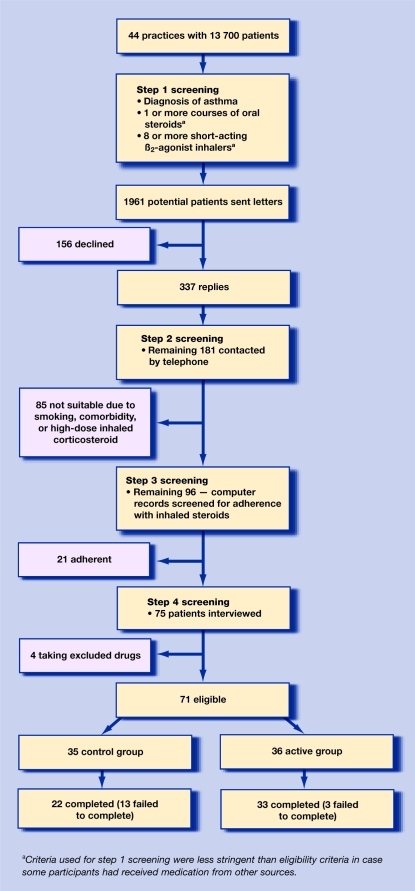

General practices in Nottinghamshire were asked to participate if patient records had been stored for at least a year on an accessible database (Torex, EM IS or Micro Medic). Suitable patients were identified using a stepwise approach combining computerised general practice records and interviews (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing stepwise participant selection and reasons for exclusions.

The study recruited patients aged 18–70 years with a diagnosis of asthma and currently prescribed 400–1000 μg/day of beclometasone dipropionate or equivalent. Participants had to have evidence of poor adherence, which was defined as having collected less than 70% of the expected number of prescriptions for inhaled corticosteroid in the year prior to the study. They also had to have evidence of poor asthma control which was defined as: having prescriptions for at least two courses of prednisolone or 10 canisters of short-acting β2-agonist in the year prior to the study; and taking four or more rescue puffs of β2-agonist for at least 4 days a week over the previous 4 weeks.

Exclusion criteria included the use of a long-acting β2-agonist, leukotriene antagonist, or oral corticosteroids in the previous 4 weeks, other significant medical problems, smoking history more than 20 pack years, pregnancy, or inadequate contraception in women of childbearing age.

Study design

This was a randomised, open-label, parallel group, 6-month study. An independent pharmacist used computer-generated random numbers to randomise each participant to one of two groups.

Control group

Participants were provided with one budesonide inhaler containing 100 doses with 200 μg budesonide per puff (Pulmicort Turbohaler® 200 μg, AstraZeneca), and were asked to take one puff twice daily and use their usual short-acting β2-agonist as required.

Active group

Participants were provided with one combined budesonide/formoterol inhaler containing 120 doses with 200 μg budesonide and 6 μg formoterol per puff (Symbicort Turbohaler® 200/6 μg, AstraZeneca). They were asked to take one puff once daily and as required, and to use no other inhaler.

Measurements

The Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (MiniAQLQ),20 and the Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ)21 were completed by participants. The MiniAQLQ score ranges from 1 to 7, with 1 indicating severely impaired asthma-related quality of life. The ACQ score ranges from 0 to 6, with 6 indicating severely uncontrolled asthma. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) were measured with participants seated, as the best of three readings (MicroLab 3500 spirometer, Micro Medical).

Protocol

Participants were seen at their general practice for study visits. At the first visit participants completed baseline MiniAQLQ and ACQ, and underwent spirometry. Study medication was then given in exchange for the patients' usual asthma medication, with instructions on its correct use. Participants in the control group kept their usual short-acting β2-agonist.

Participants were asked to contact the study coordinator to arrange a visit when their study inhaler was nearly empty. At these visits a replacement study inhaler was provided and the number of doses remaining in the returned inhaler was counted. The two asthma questionnaires were completed, information about oral steroid use or visits to their GP for asthma-related problems since the last visit were noted, and spirometry was performed. GP records were checked to corroborate the information provided by participants about unscheduled visits. A visit was arranged at 3 months if participants had not requested a new inhaler by that time, and a final visit was scheduled at 6 months. For safety reasons, participants in the active group were asked to contact the study investigator if they used 10 or more puffs of their study inhaler in 1 day.

How this fits in

Poor adherence with inhaled corticosteroid is an important problem in asthma management. Previous approaches to improving adherence have had limited success. This study has shown that using a single inhaler for both maintenance treatment and symptom relief approximately doubled the dose of inhaled corticosteroid taken. This could be a useful strategy to overcome the problems associated with poor adherence with inhaled corticosteroids.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the difference between the two groups in dose of inhaled budesonide during the 6-month study period. The total dose of budesonide taken by participants was calculated by subtracting the dose of budesonide remaining in the returned inhalers from the total dose of budesonide provided. Participants' average daily dose of budesonide was obtained by dividing the total dose taken by the number of days the participant was in the study.

Secondary outcomes included the difference between the two groups for change in MiniAQLQ and ACQ score, change in mean FEV1, oral corticosteroid use, and participants' visits to the GP for asthma-related problems.

Power calculations were based on the assumption that a 25% difference in the inhaled corticosteroid dose would be clinically important. Assuming an average dose of inhaled budesonide of 45 mg (standard deviation [SD] 10 mg) over the 6 months in the control group, 50 patients in each group gave more than 90% power to detect a 25% difference in corticosteroid dose between the treatment groups. Due to difficulty in recruitment, only 71 participants were enrolled, but the study still had 90% power to detect this difference.

Analysis

All participants seen at least once after randomisation were included in the analysis. Daily dose of budesonide and change in FEV1, MiniAQLQ, and ACQ scores were compared between groups by unpaired t-test. Average FEV1 over the study period was calculated as the mean of all FEV1 measurements obtained after the first visit. The number of participants who did not complete the study, and the number of participants visiting their GP or requiring oral steroids were compared using χ2test. Mean and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are given where appropriate.

RESULTS

Computerised records of 44 general practices were screened, from which 1961 potential participants with a diagnosis of asthma and evidence of poor asthma control were contacted by their GP on the researchers' behalf. A total of 181 patients were willing to participate and were screened further as shown in Figure 1. Of these, 71 participants fulfiled the inclusion and exclusion criteria and were randomised into two reasonably well-matched groups: 35 in the control, and 36 in the active group (Table 1). Three participants from the active group and 13 from the control group withdrew from the study (P = 0.005). There were no outcome data for the 14 participants who failed to attend after their first visit. Of the five patients who could be contacted, reasons for discontinuing were worsening asthma (2 versus 0), difficulty in using the inhaler (1 versus 3), and sore throat (1 versus 0) in the control and active groups respectively; some participants gave more than one reason.

Table 1.

Mean (SD) baseline data for control and active groups.

| Control group | Active group | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants, n | 35 | 36 |

| Age, years | 40.3 (12.3) | 40.3 (12.8) |

| Sex, male/female | 15/20 | 17/19 |

| Duration of asthma, years | 22.6 (14) | 23.1 (12) |

| Daily dose of ICS prescribed, μga,b | 565 (254) | 611 (222) |

| Daily dose of ICS used, μgb,c | 272 (185) | 283 (152) |

| Adherence with ICS, %b | 45.4 (16.6) | 45.6 (17) |

| Prednisolone courses, nb | 1.17 (1) | 1.0 (0.9) |

| Canisters of short-acting β2-agonist, nb | 10.2 (5.3) | 12.4 (4.9) |

| FEV1, litres | 2.65 (0.82) | 2.9 (0.84) |

| FEV1 % predicted | 82.3 (18.7) | 88.1 (19.3) |

| GP visits for asthma, nb | 2.4 (1.4) | 1.4 (1.1) |

| Mini AQLQ score | 4.7 (0.9) | 4.9 (1.1) |

| ACQ score | 2.11 (0.9) | 1.82 (0.8) |

| Smokers (previous or current), n | 15 | 15 |

| Pack-years among smokers | 9.5 (7) | 6.7 (5) |

ICS = inhaled corticosteroid.

Dose of ICS equivalent to beclometasone delivered by a metered dose inhaler.

Over the year prior to the study.

Estimated dose of ICS taken from number of prescriptions collected.

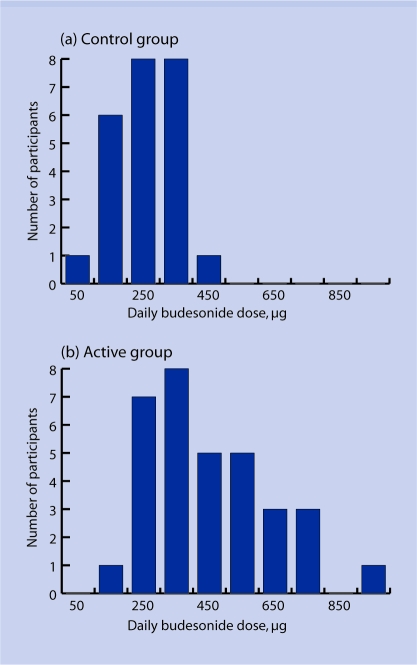

Budesonide use

The mean total dose of budesonide taken over the study period was 45.4 mg (SD = 17 mg) and 84.1 mg (SD = 35 mg) in the control and active groups respectively. The mean daily dose in the control and active groups was therefore 252 μg and 448 μg respectively, giving a mean difference of 196 μg (CI = 113 to 279; P<0.001). The mean daily dose of budesonide ranged from 10 μg to 402 μg in the control group and from 143 μg to 915 μg in the active group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Range of mean daily budesonide dose during the 6-month study. (a) Control group; (b) active group.

Adherence with inhaled corticosteroid treatment, measured from GPs' electronic prescription records, was 43% in the year prior to the study. Adherence, measured from returned inhalers during the study, was 64% in the control group but could not be measured in the active group because participants used study medication as required.

MiniAQLQ and ACQ scores

Asthma-related quality of life and asthma control improved in both groups over the study period (Table 2). Mean increases in the MiniAQLQ score were 1.02 and 1.37 in the control and active groups respectively, giving a mean difference of 0.35 (95% CI = −0.3 to 1.0; P = 0.27). Similar trends were seen for each domain score. Mean ACQ score fell over the 6 months by 0.65 and 0.80 in the control and active groups respectively, giving a mean difference between groups of 0.15 (95% CI = −0.5 to 0.7; P = 0.62).

Table 2.

Secondary outcomes: mean values for participants who visited at least once after randomisation.

| Control group | Active group | Mean difference (95% CI) | P-value χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MiniAQLQ scorea | ||||

| Baseline | 4.8 | 4.9 | ||

| Final | 5.8 | 6.3 | ||

| Change | 1.02 | 1.37 | 0.35 (−0.3 to 1) | P = 0.3 |

| ACQ scorea | ||||

| Baseline | 1.9 | 1.8 | ||

| Final | 1.25 | 1.0 | ||

| Change | −0.65 | −0.80 | 0.15 (−0.5 to 0.7) | P = 0.6 |

| FEV1 (L) | ||||

| Baseline | 2.46 | 2.86 | ||

| Average | 2.51 | 2.91 | ||

| Difference between baseline and average | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.01 (−0.2 to 0.2) | P = 0.9 |

| Final | 2.47 | 2.88 | ||

| Difference between baseline and final FEV1 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.01 (−0.2 to 0.2) | P = 0.9 |

| Number of participants visiting GP/total number of GP visits | 6/12 | 5/6 | P = 0.27 | |

| Number of participants prescribed oral steroids/total number of oral steroid courses | 3/6 | 4/6 | P = 0.63 | |

Increase in the MiniAQLQ score and a reduction in the ACQ score denotes improved asthma control. MiniAQLQ = Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. ACQ = Asthma Control Questionnaire. FEV1 = Forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

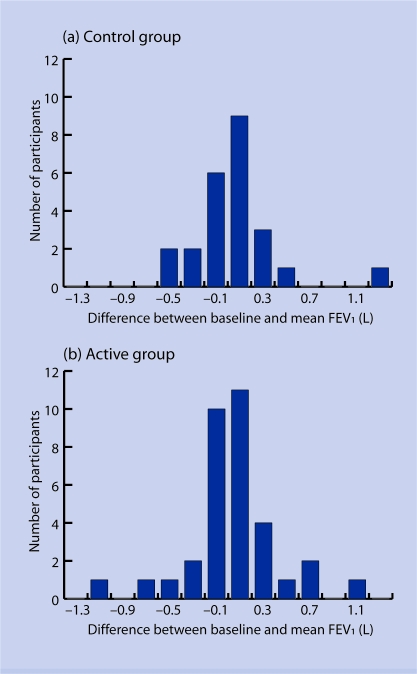

FEV1

The mean difference between baseline FEV1 and final FEV1 was 41 ml and 55 ml in the control and active group respectively. The mean change in FEV1 over the study period (difference between baseline FEV1 and average FEV1 for all subsequent study visits) was 52 ml and 46 ml in the control and active groups respectively (Appendix 1). Neither difference was significant. Average FEV1 was based on a median of two and three visits in the control and active groups respectively.

Appendix 1.

Mean change in Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) over the 6-month study period. (a) Control group; (b) active group.

Safety

No participant from the active group reported using 10 or more puffs a day of their study inhaler. During the study there were no hospital admissions, but six participants from the control group made a total of 12 visits to their GP for asthma-related problems, compared to five participants in the active group who had six visits. Three participants from the control group required a total of six courses of prednisolone for asthma-related problems compared to four participants and six courses in the active group. None of these differences was significant.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

Participants in the control group used approximately 60% of the prescribed dose of inhaled budesonide over 6 months. Providing a single inhaler containing budesonide and formoterol for both maintenance and symptom relief almost doubled the dose of budesonide taken, thereby overcoming the problem of poor adherence seen in the control group. More participants from the active group completed the study, suggesting a preference for the single-inhaler approach.

Comparison with existing literature

Using a single inhaler containing budesonide and formoterol for maintenance and symptom relief is a new approach to managing asthma, and comparisons with conventional treatment are encouraging. To date, this approach has reduced exacerbations when compared with a higher dose of inhaled corticosteroid,14–16 or an equivalent or higher dose of a combined long-acting β2-agonist and corticosteroid used for maintenance treatment only.16–19 As in most studies, patients known to have poor adherence to inhaled corticosteroid treatment were excluded from participating in these studies, and reported adherence rates during the studies were high, ranging from 85–99%.

Poor adherence with inhaled corticosteroids is a major problem in asthma management. It has been identified in 30% to 60% of patients,4–6 and is associated with poor asthma control,2 and increased mortality.22 Although some studies have shown that patient education can improve adherence with inhaled corticosteroids, these interventions have been labour intensive, and their implementation has had limited success overall.23 The present study found that using a single inhaler containing budesonide and formoterol for both maintenance and relief helped to overcome this problem because participants were unable to use their relief medication without inhaling a dose of budesonide.

Designing a study that does not affect adherence in the control group is difficult, because participation in any study is likely to influence behaviour and increase adherence, especially if there are regular study visits. The apparent increase in adherence in the control group (from 43% pre-study to 64% during the study) suggests that this may have occurred to some extent in the present study, despite attempts to minimise interventions. Nevertheless, the mean daily dose in the control group was still only 252 μg (64% of the prescribed dose), compared to 448 μg for patients in the active group. Considering the evidence for poor asthma control prior to the study, a mean daily dose of 448 μg would seem more appropriate than 252 μg, and is approximately the dose prescribed in the control group. Inhaled corticosteroid dose was chosen as the primary endpoint at this stage because clinical outcomes would have required a much larger study, and patients who rely on relief medication could have been at risk of over-treatment with the formoterol and budesonide combination. No evidence of this was found: no participant reported taking 10 or more puffs in one day, and only one patient averaged more than 800 μg budesonide a day.

Strengths and the limitations of the study

Strengths of the study include the focus on patients with poor adherence and the pragmatic design. The pragmatic approach makes the study relevant to routine clinical practice but did impose some constraints on the study design. Researchers chose to compare the single inhaler approach with twice-daily budesonide, rather than budesonide and formoterol, because the study aimed to evaluate the single inhaler approach with the treatment that most poorly-adherent patients in primary care in the UK are using.

The open-label design was essential because the intervention studied was the use of one inhaler, and a double-blind study would have required participants to use two inhalers. To reduce the effect of the study on adherence in the control group, outcome measures, such as FEV1, were measured opportunistically rather than at predetermined study visits. This meant that the study reflected usual clinical practice, but also that visits occurred at different times of day and, regardless of prior bronchodilator use, reduced the ability to detect differences in secondary outcomes, particularly FEV1.

Implications for future research and clinical practice

Poor adherence with inhaled corticosteroids is common, and a major determinant of asthma morbidity. This pragmatic study demonstrates that it can be overcome by using a single inhaler for maintenance and symptom relief. A larger study to evaluate this approach on clinically important outcomes, such as exacerbations in patients with poor adherence is now required.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants, Trent Focus for helping us to contact some of the practices, Sarah Pacey (senior pharmacist) for providing randomisation codes and dispensing the study medication, and Sarah Lewis (professor in medical statistics) for statistical advice. We are especially grateful to the practices, practice managers, and IT staff for help in conducting and running the initial search and writing to the patients on our behalf

Funding body

The study was supported by a non-conditional grant from AstraZeneca. The sponsors of the study commented on the protocol but had no role in data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing the paper apart from Tommy Ekström who commented on the final manuscript

Ethical approval

Nottingham City Hospital ethics committee approved the study, and all participants provided written informed consent

Competing interests

The study was conceived, designed, executed, analysed, and written up in Nottingham and was supported by a non-conditional grant from AstraZeneca which included Milind P Sovani's salary. Christopher I Whale, Janet Oborne, Sue Cooper, and Kevin Mortimer have no conflict of interest. Tommy Ekström is employed by AstraZeneca. Anne E Tattersfield has received honoraria from AstraZeneca for speaking at meetings. Timothy W Harrison has received honoraria from AstraZeneca for speaking at meetings and attending advisory groups

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Senthilselvan A, Lawson JA, Rennie DC, Dosman JA. Regular use of corticosteroids and low use of short-acting beta2-agonists can reduce asthma hospitalisation. Chest. 2005;127(4):242–251. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.4.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krishnan JA, Riekert KA, McCoy JV, et al. Corticosteroid use after hospital discharge among high-risk adults with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(12):1281–1285. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200403-409OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams LK, Pladevall M, Xi H, et al. Relationship between adherence to inhaled corticosteroids and poor outcomes among adults with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(6):1288–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh LJ, Wong CA, Cooper S, et al. Morbidity from asthma in relation to regular treatment: a community based study. Thorax. 1999;54(4):296–300. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.4.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cerveri I, Locatelli F, Zoia MC, et al. International variations in asthma treatment compliance: the results of the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) Eur Respir J. 1999;14(2):288–294. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14b09.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diette GB, Wu AW, Skinner EA, et al. Treatment patterns among adult patients with asthma: factors associated with overuse of inhaled beta-agonists and underuse of inhaled corticosteroids. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(22):2697–2704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.22.2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boulet LP. Perception of the role and potential side effects of inhaled corticosteroids among asthmatic patients. Chest. 1998;113(3):587–592. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van der Palen J, Klein JJ, van Herwaarden CLA, et al. Multiple inhalers confuse asthma patients. Eur Respir J. 1999;14(5):1034–1037. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.14510349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mann MC, Eliasson O, Patel K, ZuWallac RL. An evaluation of severity-modulated compliance with q.i.d. dosing of inhaled beclomethasone. Chest. 1992;102(5):1342–1346. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.5.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Noord JA, Smeets JJ, Raaijmakers JA, et al. Salmeterol versus formoterol in patients with moderately severe asthma: onset and duration of action. Eur Respir J. 1996;9(8):1684–1688. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09081684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tattersfield AE, Lofdahl CG, Postma DS, et al. Comparison of formoterol and terbutaline for as-needed treatment of asthma: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:257–261. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03611-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pauwels RA, Sears MR, Campbell M, et al. Formoterol as relief medication in asthma: a worldwide safety and effectiveness trial. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(5):787–794. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00055803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ind PW, Villasante C, Shiner RJ, et al. Safety of formoterol by Turbuhaler as reliever medication compared with terbutaline in moderate asthma. Eur Respir J. 2002;20(4):859–866. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00278302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabe KF, Pizzichini E, Stallberg B, et al. Budesonide/formoterol in a single inhaler for maintenance and relief in mild-to-moderate asthma. Chest. 2006;129(2):246–256. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scicchitano R, Aalbers R, Ukena D, et al. Efficacy and safety of budesonide/formoterol single inhaler therapy versus a higher dose of budesonide in moderate to severe asthma. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20(9):1403–1419. doi: 10.1185/030079904X2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Byrne PM, Bisgaard H, Godard PP, et al. Budesonide/formoterol combination therapy as both maintenance and reliever medication in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(2):129–136. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200407-884OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogelmeier C, D'Urzo A, Pauwels R, et al. Budesonide/formoterol maintenance and reliever therapy: an effective asthma treatment option? Eur Respir J. 2005;26(5):819–828. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00028305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lundborg M, Soren W, Bjermer W, et al. Maintenance plus reliever budesonide/formoterol compared with a higher maintenance dose of budesonide/formoterol plus formoterol as reliever in asthma: anefficacy and cost-effectiveness study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(5):809–821. doi: 10.1185/030079906X100212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rabe KF, Atienza T, Magyar P, et al. Effect of budesonide in combination with formoterol for reliever therapy in asthma exacerbations: a randomised controlled, double-blind study. Lancet. 2006;368:744–753. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Cox FM, et al. Development and validation of the Mini Asthma Quality of Life questionnaire. Eur Respir J. 1999;14(1):32–38. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14a08.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juniper EF, O'Byrne PM, Guyatt GH, et al. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure asthma control. Eur Respir J. 1999;14(4):902–907. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d29.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suissa S, Ernst P, Benayoun S, et al. Low-dose inhaled corticosteroids and the prevention of death from asthma. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(5):332–336. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008033430504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bender B, Milgrom H, Apter A. Adherence intervention research: What have we learned and what do we do next? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(3):489–494. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)01718-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]