Abstract

The visual correction employed during isometric contractions of large proximal muscles contributes variability to the descending command and alters fluctuations in muscle force. This study explored the contribution of visuomotor correction to isometric force fluctuations for the more distal dorsiflexor (DF) and plantarflexor (PF) muscles of the ankle. Twenty-one healthy adults performed steady isometric contractions with the DF and PF muscles both with (VIS) and without (NOVIS) visual feedback of the force. The target forces exerted ranged from 2.5% to 80% MVC. The standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV) of force was measured from the detrended (drift removed) VIS and NOVIS steadiness trials. Removal of VIS reduced the CV of force by 19% overall. The reduction in fluctuations without VIS was significant across a large range of target forces and was more consistent for the PF than the DF muscles. Thus, visuomotor correction contributes to the variability of force during isometric contractions of the ankle dorsiflexors and plantarflexors.

Keywords: vision, force fluctuations, motor output variability, physiological tremor

1.0 Introduction

The neural mechanisms underlying force fluctuations during steady voluntary muscle contractions include altered discharge behavior of single and multiple motor units in agonist and antagonist muscles (De Luca & Erim, 1994; Laidlaw, Bilodeau, & Enoka, 2000; Welsh, Dinenno, & Tracy, 2006). In addition to variability related to the membrane noise properties of motor neurons (Calvin & Stevens, 1968; Powers & Binder, 2000), the discharge behavior of motor units is influenced by the supraspinal (voluntary command), spinal, and reflex inputs they receive (Parkis, Feldman, Robinson, & Funk, 2003; Salenius, Portin, Kajola, Salmelin, & Hari, 1997). As an example, when muscle spindle afferent feedback is disturbed by long term vibration, the variability of motor output during steady contractions is altered (Shinohara, Moritz, Pascoe, & Enoka, 2005; Yoshitake, Shinohara, Kouzaki, & Fukunaga, 2004). The supraspinal descending command can be modulated by visual information. For example, when visual feedback is used to exert a steady muscle force, voluntary visuomotor correction contributes variability to the excitation of motor units (Welsh et al., 2006) and muscle force fluctuations (Tracy, Dinenno, Jorgensen, & Welsh, 2006).

The ankle dorsiflexors and plantarflexors are very different from each other in size (Fukunaga, Roy, Shellock, Hodgson, & Edgerton, 1996), strength (Belanger, McComas, & Elder, 1983), motor unit number (Feinstein, Lindegard, Nyman, & Wohlfart, 1955; McNeil, Doherty, Stashuk, & Rice, 2005), corticospinal input (Bawa, Chalmers, Stewart, & Eisen, 2002; Brouwer & Ashby, 1990; Nielsen & Petersen, 1995), and typical use. Control of force is an important feature of neuromuscular performance for these muscles due to their role in postural control (Laughton et al., 2003). Visuomotor processing has been observed to contribute to fluctuations for a hand muscle (Sosnoff & Newell, 2006) and larger proximal muscles (Tracy, Dinneno et al., 2006), but not for fluctuations in pinch-grip muscles (Christou, 2005). However, the contribution of visuomotor correction to the variability of force output for larger, more distal ankle muscles has not been determined.

The purpose of this study was to determine the contribution of visuomotor correction to force fluctuations during dorsiflexor and plantarflexor contractions. The steadiness of isometric contractions was measured across a range of submaximal target forces with and without visual feedback of the force. These data have been presented previously in abstract form (Tracy, Dinenno, & Jorgensen, 2004).

2.0 Methods

Participants

Twenty one (11 young, 22.7 ± 2.7 yrs, range: 19−27 yrs, and 10 elderly, 72.8 ± 5.5 yrs, range: 66−82 yrs) healthy adults volunteered for the study. They neither reported nor exhibited neurological disease, reported no medications known to influence the dependent measures, and reported no more than 3 hours per week of moderate-intensity endurance exercise and no strength training for at least the preceding year. Participants were briefed on the study and provided written informed consent. The Human Research Committee at the University of Colorado in Boulder approved the procedures in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Experimental Design

Participants took part in a ∼ 2 hour experiment during which MVC force and steadiness were assessed for the ankle dorsiflexors and plantarflexors. The muscle groups were tested separately in random order. A rest break was given between the testing for each muscle group. Participants refrained from caffeine consumption and vigorous exercise prior to the experiment.

Experimental Set-up

Participants were seated in an experimental chair with the left leg extended in front of them. The foot was secured with nylon straps onto a foot plate that was secured to the wall vertically in front of the chair. The chair was secured to the floor. Load cells of differing sensitivities (1335 N, 223N, Siebe-Lebow, USA, and 22 N maximum, Sensotec, USA) were secured under the foot plate to measure dorsiflexion or plantarflexion force during strength and steadiness tasks. The position of the load cell was adjustable for different foot lengths. Force was measured perpendicular to the foot plate under the ball of the foot. The pelvis and left thigh was secured to the chair with nylon straps and lateral movement of the lower leg was prevented by two rigid restraints. During dorsiflexor tasks, the ankle angle was 5° (0.09 rad) plantarflexed from a right angle, the knee angle was 150° (2.63 rad) (180° = straight leg) and the fore-aft position of the chair was adjusted so that the left hip joint angle was 90° (1.58 rad) (180° = straight hip). During plantarflexor tasks, the ankle angle was the same, the knee was straight, and the hip angle was 110° (1.93 rad). The arms were crossed in front of the chest. The testing positions were chosen to best isolate the test muscle groups and minimize co-contraction of other muscles, based on pilot testing.

The force signal was collected using S-series transducer couplers (Coulbourn Instruments, USA), digitized at 0.5 kHz to a computer (1401 plus A/D device, Cambridge Electronic Design, UK), and analyzed offline (Spike 2, ver. 4, Cambridge Electronic Design, UK).

Experimental Protocol

MVC Task

Participants increased the force to maximal over ∼3 s and were strongly verbally encouraged to exert maximal force for approximately 3 s. At least three trials were performed. If two trials were not within 5% of each other, a fourth or fifth trial was performed (Tracy, Dinneno et al., 2006). At least one minute of rest was given between trials. This strategy does not produce muscle fatigue that can be detected as a reduction in maximal force. MVC force was measured with the same general protocol for both muscle groups. Ankle dorsiflexion force was exerted by pulling the front of the foot against the straps; plantarflexion force was exerted by pushing into the foot plate. Participants were instructed to isolate the test muscle as much as possible. For MVC trials visual feedback of the force was provided in the form of a bold line scrolling left-to-right across an oscilloscope screen. The oscilloscope was ∼75cm in front of the participant. Participants neither reported nor exhibited problems viewing and interpreting the visual feedback.

Isometric Steadiness

Force was measured during isometric constant-force tasks performed at 2.5%, 5%, 10%, 30%, 50%, and 80% of MVC force, in random order. The most sensitive load cell possible was used for a particular target force, to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio.

For constant-force tasks a bold horizontal target line was displayed on an oscilloscope display that was 10cm wide and 8cm high. For each target force the vertical sensitivity of the oscilloscope was adjusted so that the target line remained 6 cm up the screen (Tracy, Dinneno et al., 2006; Tracy & Enoka, 2002; Tracy, Mehoudar, & Ortega, 2006). This method of displaying the target force produced large differences in the visual gain of force feedback across target forces. For example, the visual gain was 2.4 cm/%MVC for the 2.5% MVC target force and 0.075 cm/%MVC for 80% MVC. The muscle force was represented by a bold horizontal line that moved up or down with changes in force. For a trial, participants increased the force over ∼1 s up to a target line and were instructed to maintain the force as steadily as possible for 5−10s with visual feedback and then 5−10s with the screen obscured. One practice trial was performed before two trials that were recorded for analysis. To prevent significant muscle fatigue, the force was held with visual feedback for approximately 5 s for the 50% and 80% MVC trials but 8−10 s was allowed for trials at lower target forces. A minimum of one minute of rest was given between the 50% and 80% MVC trials, and 30 s of rest was given between trials for the lower target forces. Participants reported no appreciable muscle fatigue during the protocol.

Data Analysis

For the MVC task the dependent variable was the maximal force (N) for a 0.25 s segment centered around the peak force for a trial.

As expected, the force signal drifted away from the target during the no-vision segments (Tracy, Dinneno et al., 2006; Welsh et al., 2006). This low frequency drift was removed using the DC remove function in the Spike 2 software with a 1s time constant. The function subtracted the mean of the signal calculated over a 1s window that was passed over the data in increments of one data point. This procedure, which was applied to both the vision and no-vision segments, removed frequencies < .5 Hz and produced a new signal that fluctuated around a mean of zero (Fig. 1). The drift was removed because it simply represents the fact that the target was invisible to the participant and would produce exaggerated SD of force values if included in the calculations. After extensive pilot testing, the 1s time constant for the DC remove function was chosen with the goal of removing the drift while at the same time preserving the force fluctuations that occurred around the drifting force (Fig. 1). The pilot testing was accomplished by detrending with multiple iterations of time constants and comparing the effects on the fluctuations. For the 1s time constant, the SD of force during the vision segments was not significantly affected but the drift was removed from the no-vision segment (see Fig. 1). The detrending process was applied to both vision and no-vision segments, therefore any signal content affected by detrending was similar for vision and no-vision – so they can be legitimately compared.

Fig. 1.

Constant-force tasks with the ankle dorsiflexors at 50% MVC (A) and plantarflexors at 10% MVC (B). The horizontal dashed line indicates the target force. The vertical dashed line indicates removal of visual feedback. The detrended force is inset below the original force trace. (C) Power spectrum averaged across forces, vision conditions, and age groups. Power is expressed in 0.49 Hz bins as a percent of the total power between 0 and 30 Hz and displayed as a smoothed line.

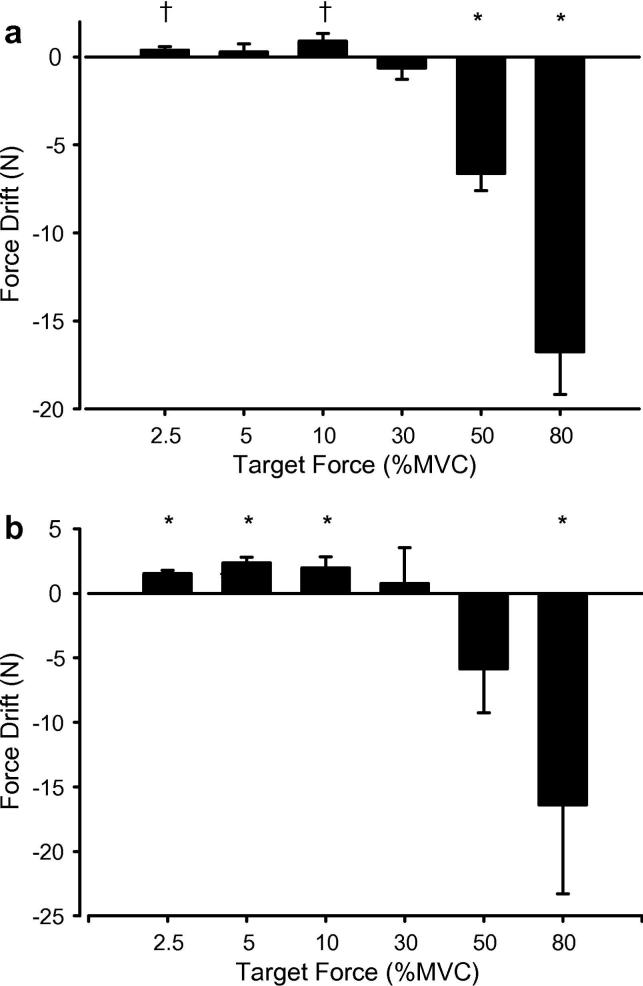

Because the detrended force fluctuated around a mean of zero, the mean force for an entire segment was calculated before removal of drift. The amount of drift (Fig. 2) was quantified by comparing the mean force for vision with no-vision segments. After detrending, the standard deviation (SD, N) and coefficient of variation (CV = SD of force/mean force *100) of force was calculated for the entire segment. This strategy provided a measure of the average fluctuations for an entire segment expressed as a percentage of the mean force exerted over the entire segment. We tested the use of 1s sequential bins averaged over the segment for the steadiness analysis (Vaillancourt & Russell, 2002), and found a similar vision result compared with the method presented here. Thus, it was decided to use the same analysis as our recent work on the topic (Tracy, Dinneno et al., 2006; Welsh et al., 2006).

Fig. 2.

The change (drift) in the average force (N) for vision compared with no-vision segments for the ankle dorsiflexors (A) and plantarflexors (B) for each target force. Young and elderly participants were not different and are pooled. * p < .05 for vision compared with no-vision. † p = .06 for vision compared with no-vision. Error bars are standard error of the mean (SEM).

The analyzed data segments were 5−6 s in duration for the 50% and 80% MVC target forces and 8−10 s for lower target forces. For each target force, the values from two trials were averaged.

Frequency spectral analysis of the force during steadiness tasks was conducted in the Spike 2 program using an FFT block size of 2048 with a Hanning window that yielded a frequency resolution of 0.49 Hz from 0−500 Hz. This frequency analysis was performed on the same detrended data segments that were used for the calculation of SD and CV of force. There was negligible power above 4−5 Hz; power values from 0−30 Hz were used in calculating the percent of total power for each frequency bin (Tracy, Dinneno et al., 2006).

Statistical analysis

Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine within-subjects variables: muscle group (plantarflexor, dorsiflexor), vision condition (vision, no-vision), and target force (2.5, 5, 10, 30, 50, and 80% MVC). The between-subjects variable was age group (young, elderly), however the data from young and elderly are pooled here because 1) there were no age differences in the effects of vision condition or effects of target force on force drift or fluctuations, and 2) the focus of this report was visual feedback effects between muscles. The effects of age group on fluctuations are reported elsewhere (under review), thus the young and elderly are pooled together here to examine vision effects. Planned comparisons were used to test differences between means; no corrections were made for multiple comparisons within a family (target force level) of tests. Exact P-values are reported wherever they convey the result of one comparison. When a stated result required more than one P-value, the significance is denoted as (p < .05, 0.01, 0.001) for clarity. SPSS version 13 was used.

3.0 Results

Participant characteristics

The young (23 ± 3 yrs, N = 11) and elderly (73 ± 6 yrs, N = 10) participants were of similar height (173 ± 11 cm, p = .3), body mass (76.3 ± 15.5 kg, p = .7), and body mass index (25.4 ± 4.1 kg/m2, p = .2). The MVC force of the PF muscles (598 ± 223 vs. 959 ± 242 N, p = .002), but not the DF muscles (204 ± 71 vs. 258 ± 93 N, p = .15), was lower for elderly compared with young adults.

Ankle dorsiflexors

Forces exerted

When visual feedback was removed, the force drifted for some target forces (Figs. 1 and 2A). At the 2.5% MVC target the force drifted up (p = .06), at 5% MVC there was no change (p = .55), at 10% MVC the force drifted up (p = .06), at 30% MVC there was no change (p = .33), and for 50% and 80% MVC the force decreased (p < .0001). The drift was significantly different across target forces (Force × Vision interaction, p < .05). The drift was not different between age groups (p = .7).

The purpose of the power spectrum data displayed was to describe the dominant frequencies of the force fluctuations. The power spectrum of the detrended force was dominated by frequencies between 0.5 and 4 Hz with negligible contribution to the total power above 4 Hz (Fig. 1C). The dominant frequency was not consistently different across muscle groups, target forces, vision conditions, or age groups; the data are pooled across these conditions.

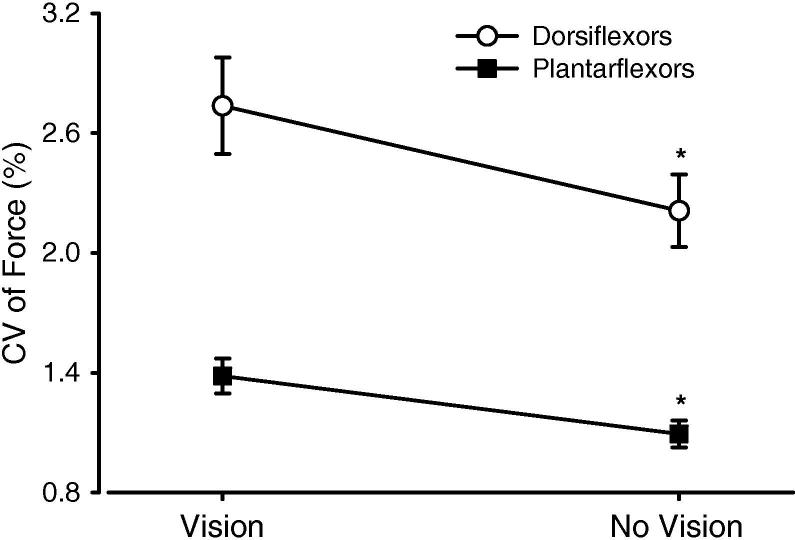

Force fluctuations

The CV of force decreased with target force from 2.5% to 30% MVC (p < .05) and did not change (p > .05) from 30% to 80% MVC (Fig. 4A). The decrease in CV of force from 2.5% to 10% MVC was less steep for the DF than the PF muscles (Muscle × Force interaction, p < .05). Pooled across target forces and age groups, the CV of force was reduced by 19.2% with removal of visual feedback (p < .001, Fig. 3). The effect of removal of vision was different for target forces; the decrease in the CV of force was significantly greater (Force × Vision interaction, p < .05) for 2.5% MVC (−27.9%, p = .003) and 5% MVC (−24.3%, p < .001) compared with the changes at 10% MVC (−13.2%, p = .1), 30% MVC (−20.9%, p = .002), 50% MVC (−20.6%, p = .06), and 80% MVC (+10.9%, p = .09) (Fig. 4A). The visual feedback effect was not different between age groups (p = .3).

Fig. 4.

Coefficient of variation (CV) of force during constant-force contractions of the ankle dorsiflexors (A) and plantarflexors (B) performed across a range of target forces both with and without visual feedback. Values are pooled across age group. * p < .05 for vision compared with no-vision. † p = .06 for vision compared with no-vision. Error bars are standard error of the mean (SEM). The actual average force exerted for no-vision was different than the nominal target forces (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 3.

Coefficient of variation (CV) of force during constant-force contractions of the ankle dorsiflexors and plantarflexors for vision and no-vision conditions. Values are pooled across target forces and age groups. * p < .001 for main effect of visual feedback. Error bars are standard error of the mean (SEM).

There were no significant interactions between muscle groups for the effect of target force (Muscle × Force interaction, p < .05).

Ankle plantarflexors

Forces exerted

At the 2.5%, 5%, and 10% MVC target forces the force drifted up without vision (p < .0001, p < .0001, p = .033). For 30% and 50% MVC the drift was not significant (p = .78, p = .10), and for 80% MVC the force decreased (p = .03) (Fig. 2B). The drift was significantly different across target forces (Force × Vision interaction, p < .05). The drift was not different between age groups (p = .45).

Fluctuations

The CV of force decreased (p < .0001) as target force increased from 2.5% to 10% MVC and did not change significantly (p > .05) from 10% to 80% MVC (Fig. 4B). Pooled across target forces and age groups, the CV of force declined by 21% with removal of visual feedback (p < .0001, Fig. 3). Unlike the dorsiflexors, the effect of removal of visual feedback was significant for all target forces (p < .01 for 2.5%, 5%, 10%, 30%, and 50% MVC; p = .03 for 80% MVC) (Fig. 4B). The effect of visual feedback removal was greater for 2.5% and 5% MVC compared with higher target forces (Force × Vision interaction, p < .05, Fig. 4B). The effect of visual feedback removal was not different between age groups (p = .4).

4.0 Discussion

The main findings were 1) the amplitude of dorsiflexor and plantarflexor force fluctuations was reduced when visual feedback was removed, and 2) the overall reduction in fluctuations was significant for both muscles and was more consistent for the plantarflexors than the dorsiflexors.

Visuomotor correction is employed to modulate the descending command and perform a constant-force task with vision. As would be expected (Vaillancourt & Russell, 2002), visual feedback during the task produced better overall matching of a specified target force. The force drifted without visual feedback of the target (Figs. 1 and 2). The present findings, however, provide support for the notion that visuomotor processing increased oscillations in the descending command and force variability during the isometric force task. This conclusion, that visual feedback actually contributes to the force fluctuations, initially may appear contrary to the clear benefit of vision during precision tasks (Woodworth, 1899). Importantly, however, the low-frequency drift (< .5 Hz) was removed before the fluctuations were quantified. Thus, the variability values presented here for no-vision represent voluntary correction using feedback from limb afferents but not drift away from the target. In the absence of visual feedback, the reduced variability is likely due to a reduced visuomotor contribution to the descending command. For example, we showed that visuomotor correction contributed to both force variability and motor unit discharge variability in large proximal muscles such as the elbow flexors and knee extensors (Tracy, Dinneno et al., 2006; Welsh et al., 2006). The contribution of visuomotor correction to force fluctuations thus appears to extend to larger distal muscles of the ankle.

The finding that the visuomotor effect was significantly greater for lower target forces supports the idea that removal of vision produced the observed effects. Across target forces, the target was at the same vertical location (by design), which produced a much greater visual gain of the force feedback (cm on screen/N of force) for the lowest target forces (see Methods). Although this strategy did not enable us to determine if differences in fluctuations across target forces were due to visual gain or target force, an experimental condition was produced at lower target forces where changes in force resulted in larger excursions on the screen - to compare with the no-vision condition. At the lower target forces, therefore, visual information was presumably more important to task performance and added to the fluctuations in the descending command, thus the difference between vision and no-vision conditions was greater.

Visual feedback was always provided before it was removed, thus there is the potential that the reduced fluctuations were partially due to an order or learning effect. We did not directly assess this possibility in this study and thus cannot definitively rule it out. However, this possibility is minimized by the following observations, 1) the change in force variability upon removal of visual feedback (see Fig. 1) was immediate and qualitatively striking for most trials, 2) when the visual gain was higher, the SD of force declined from vision to no-vision despite the fact that the force drifted up significantly – the opposite, a greater SD of force, would be expected when the exerted force is greater (Jones, Hamilton, & Wolpert, 2002; Tracy & Enoka, 2002), and 3) in a separate unpublished dataset we observed no change in the CV of force from the beginning to the end of 20s isometric trials with vision (1.35 ± 0.6% vs. 1.25 ± 0.6%, p > .05, N = 14 young participants). Our practice trials also serve to minimize the potential for the contribution of a learning effect. Also, Vaillancourt et al. (2002) found no change in fluctuations over the course of a 20 s constant-force trial (Vaillancourt & Russell, 2002). Together this minimizes the likelihood that a learning or order effect contributed to the reduced fluctuations without vision within a trial.

During a steady voluntary contraction, the descending command to motor neurons is adjusted in response to feedback from visual afferents, limb sensory afferents, and proprioceptive afferents. The synaptic input to motor neurons that ultimately determines the variability of their excitation and the muscle output includes the descending input as well as spinal inputs such as those from recurrent inhibition, muscle spindles, and tendon organs. The present findings suggest that an important source of variability arises from the voluntary process of correcting force in response to visual afferent information. The visual effects appear more consistent for the plantarflexors than dorsiflexors, suggesting that the balance of the various inputs for the plantarflexors was more altered by removing the visual afferent sources. Used to precisely clear obstacles during locomotor activities, the dorsiflexors may receive more corticospinal influence compared with the plantarflexors (Bawa et al., 2002; Capaday, Lavoie, Barbeau, Schneider, & Bonnard, 1999). Perhaps these factors are more important, in a relative sense, in the mixture of the inputs to motor neurons than the afferent information associated with visual feedback, and the change in visual afferent information makes less of a difference in the overall mix for the dorsiflexors. This notion is speculative, however, as these data cannot directly address this possibility.

In conclusion, the presence of visual feedback during steady isometric contractions of the ankle dorsiflexors and plantarflexors appears to contribute significant oscillation to the descending command and the motor output. The greater differences at low forces may have been due to the greater visual gain of the force feedback, although other factors may play a role. The visuomotor contribution was somewhat more consistent for the plantarflexors than the dorsiflexors.

Acknowledgments

The substantial contributions of Regan Howard and Kyle Kirby are gratefully acknowledged, as are the analytical contributions of Devin Dinenno and Bjørn Jørgensen. This project was supported by NIH K01 AG19171 to BL Tracy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bawa P, Chalmers GR, Stewart H, Eisen AA. Responses of ankle extensor and flexor motoneurons to transcranial magnetic stimulation. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2002;88:124–132. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belanger AY, McComas AJ, Elder GB. Physiological properties of two antagonist human muscle groups. European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology. 1983;51:381–393. doi: 10.1007/BF00429075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer B, Ashby P. Corticospinal projections to upper and lower limb spinal motoneurons in man. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1990;76:509–519. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(90)90002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvin WH, Stevens CF. Synaptic noise and other sources of randomness in motoneuron interspike intervals. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1968;31:574–587. doi: 10.1152/jn.1968.31.4.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaday C, Lavoie BA, Barbeau H, Schneider C, Bonnard M. Studies on the corticospinal control of human walking. I. Responses to focal transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;81:129–139. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christou EA. Visual feedback attenuates force fluctuations induced by a stressor. Medicine and Sciences in Sports and Exercise. 2005;37:2126–2133. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000178103.72988.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca CJ, Erim Z. Common drive of motor units in regulation of muscle force. Trends in Neuroscience. 1994;17:299–305. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein B, Lindegard B, Nyman E, Wohlfart G. Morphologic studies of motor units in normal human muscles. Acta Anatomica. 1955;23:127–142. doi: 10.1159/000140989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga T, Roy RR, Shellock FG, Hodgson JA, Edgerton VR. Specific tension of human plantar flexors and dorsiflexors. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1996;80:158–165. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KE, Hamilton AF, Wolpert DM. Sources of signal-dependent noise during isometric force production. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2002;88:1533–1544. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.3.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laidlaw DH, Bilodeau M, Enoka RM. Steadiness is reduced and motor unit discharge is more variable in old adults. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:600–612. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(200004)23:4<600::aid-mus20>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughton CA, Slavin M, Katdare K, Nolan L, Bean JF, Kerrigan DC, et al. Aging, muscle activity, and balance control: physiologic changes associated with balance impairment. Gait & Posture. 2003;18:101–108. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(02)00200-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil CJ, Doherty TJ, Stashuk DW, Rice CL. Motor unit number estimates in the tibialis anterior muscle of young, old, and very old men. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31:461–467. doi: 10.1002/mus.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen J, Petersen N. Evidence favouring different descending pathways to soleus motoneurones activated by magnetic brain stimulation in man. Journal of Physiology. 1995;486:779–788. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkis MA, Feldman JL, Robinson DM, Funk GD. Oscillations in endogenous inputs to neurons affect excitability and signal processing. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:8152–8158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-22-08152.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers RK, Binder MD. Relationship between the time course of the afterhyperpolarization and discharge variability in cat spinal motoneurones. Journal of Physiology. 2000;528(Pt 1):131–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salenius S, Portin K, Kajola M, Salmelin R, Hari R. Cortical control of human motoneuron firing during isometric contraction. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;77:3401–3405. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.6.3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara M, Moritz CT, Pascoe MA, Enoka RM. Prolonged muscle vibration increases stretch reflex amplitude, motor unit discharge rate, and force fluctuations in a hand muscle. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2005;99:1835–1842. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00312.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosnoff JJ, Newell KM. Information processing limitations with aging in the visual scaling of isometric force. Experimental Brain Research. 2006;170:423–432. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy BL, Dinenno DV, Jorgensen B. Removal of visual feedback reduces force fluctuations in the ankle dorsiflexor and plantarflexor muscles of young and old adults. Society for Neuroscience. 2004:188.19. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy BL, Dinenno DV, Jorgensen B, Welsh SJ. Aging, visuomotor correction, and force fluctuations in large muscles. Med Sci Spts Exerc. 2006 doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31802d3ad3. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy BL, Enoka RM. Older adults are less steady during submaximal isometric contractions with the knee extensor muscles. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2002;92:1004–1012. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00954.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy BL, Mehoudar PD, Ortega JD. The amplitude of force variability is correlated in the knee extensor and elbow flexor muscles. Experimental Brain Research. 2007;176:448–64. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0631-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt DE, Russell DM. Temporal capacity of short-term visuomotor memory in continuous force production. Experimental Brain Research. 2002;145:275–285. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh SJ, Dinenno DV, Tracy BL. Variability of quadriceps femoris motor neuron discharge and muscle force in human aging. Experimental Brain Research. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0785-z. in press, DOI 10.1007/s00221-006-0785-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodworth RS. The accuracy of voluntary movement. Psychol Rev. 1899;3:1–119. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshitake Y, Shinohara M, Kouzaki M, Fukunaga T. Fluctuations in plantar flexion force are reduced after prolonged tendon vibration. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2004;97:2090–2097. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00560.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]