Abstract

Glucocorticoids are commonly used antiinflammatory agents whose use is limited by side effects. We have developed a series of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) ligands that retain the strong antiinflammatory activity of conventional glucocorticoids with reduced side effects. We present a compound, LGD5552, that binds the receptor efficiently and strongly represses inflammatory gene expression. LGD5552 bound to GR activates gene expression somewhat differently than glucocorticoids. It activates some genes with an efficacy similar to that of the glucocorticoids. However, other glucocorticoid-activated genes are not regulated by LGD5552. These differences may be because of the more efficient binding of corepressor in the presence of LGD5552, compared with glucocorticoid agonists. This class of nonsteroidal, GR-dependent antiinflammatory drugs may offer a safer alternative to steroidal glucocorticoids in the treatment of inflammatory disease.

Keywords: selective glucocorticoid receptor modulator (SGRM), nonsteroid, dissociated, repression

Glucocorticoids are widely prescribed to prevent the signs and symptoms of inflammation. These compounds are powerful inhibitors of inflammatory cells, cytokines, and signals. Unfortunately, their sustained use also results in a series of dose-limiting side effects that prevent their full antiinflammatory potential from being realized. Patients experience weight gain, diabetes, hypertension, osteoporosis, behavioral changes, and sleep disorders, among others (1). The effects of these small-molecule hormones are mediated by the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), a cytoplasmic, ligand-dependent transcription factor. GR adopts an altered conformation in response to ligand binding, translocates into the nucleus, and regulates gene expression directly by binding to specific DNA sequences within genes termed GR elements. The receptor also alters gene expression by direct interaction with nonreceptor proteins bound to promoters (2).

It might be possible to separate the antiinflammatory effects of steroidal glucocorticoids from some of the side effects by finding compounds that alter the structure and, subsequently, the function of GR differently from steroids. Initially, the hypothesis was proposed that separating the activation and repression functions of GR would be sufficient to produce a selective GR modulator (3). The glucocorticoid and progesterone antagonist, RU486, does have repression capability in some models and is extremely weak at activating transcription. However, it does not exhibit antiinflammatory activity in vivo (4).

The activation-repression hypothesis has led to the discovery of a number of interesting molecules (1, 5), a few of which exhibit some separation between activation and repression functions in vitro, (6), but not in all tissues (4). Others have demonstrated antiinflammatory efficacy with reduced side effects, but exhibit selective gene regulation to accomplish this result (7–9). These compounds appear to interact preferentially with certain coactivators. The profile of gene expression generated by GR bound to these ligands can be altered by the ligand's structure (9). We exploited this mechanism of action to detect, characterize, and develop newer, more potent compounds for use in the treatment of inflammatory disease.

We previously screened compound libraries by using high-throughput assays to detect GR ligands. After medicinal chemistry optimization of a selected lead series (10, 11), we characterized the activity of a C5-benzylidene compound, LGD5552, for its effects on GR structure and function both in vitro and in vivo. We found that this molecule reduces the ability of GR to activate transcription at some genes while maintaining or even enhancing its repression capability. We provide evidence that this altered gene expression profile is the result of diminished interaction with coactivator proteins and an enhanced interaction with corepressor proteins. Despite reductions in coactivator binding, this compound remains fully efficacious in vivo when tested in the mouse collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) model, compared with the glucocorticoid prednisolone. At fully efficacious doses in mice, LGD5552 reduced impact on bone formation and body fat relative to prednisolone. LGD5552 exhibits a potentially beneficial profile for therapeutic intervention in inflammatory disease.

Results

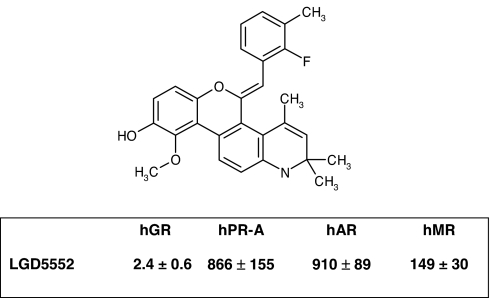

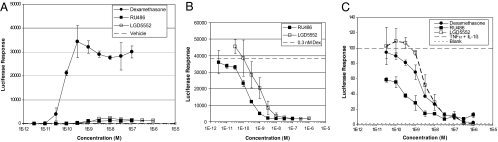

LGD5552 [(5Z)-5-[(2-fluoro-3-methylphenyl)methylene]-2,5-dihydro-10-methoxy-2,2,4-trimethyl-1H-[1]benzopyrano[3,4-f]quinolin-9-ol] has a molecular weight of 443.5 g/mole (C28H26FNO3) and binds efficiently to GR with a Ki of 2.4 nM (Fig. 1). LGD5552 is highly selective for GR, binding other steroid receptors with potency >100 nM (mineralocorticoid receptor exhibits a Ki of 149 nM) (Fig. 1). Binding of LGD5552 to GR induces gene-selective transcriptional regulation compared with prednisolone. When monitored by using the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter (MMTV):luciferase reporter construct in CV-1 cells, dexamethasone is extremely active and capable of inducing MMTV transcription >1,000-fold. In contrast, LGD5552 exhibits little transactivation activity and can act as an antagonist when tested against dexamethasone at subsaturating concentrations (Fig. 2 A and B). To test LGD5552 in an efficacy-related endpoint in vitro, we used the E-selectin promoter:luciferase assay and demonstrated that, although it is unable to transactivate MMTV, LGD5552 remains a potent repressor of transcription from the inflammatory marker gene E-selectin with efficacy similar to that of dexamethasone (Fig. 2C). Consistent with their binding affinity, LGD5552 and prednisolone are equally potent and efficacious in the repression of E-selectin (data not shown), although both are less potent than dexamethasone (LGD5552, ED50 = 2 nM, efficacy 100%; prednisolone, ED50 = 4 nM, efficacy 98%; dexamethasone, ED50 = 0.1 nM, efficacy 100%). RU486 also is capable of repressing E. selectin gene expression; however, it fails to reach full efficacy (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 1.

The benzylidene LGD5552 exhibits selective binding to human GR (hGR). The structure of LGD5552 is shown above a table with the binding affinity (Ki in nM) of the compound for human GR (hGR), human progesterone (hPR-A), human androgen (hAR), and human mineralocorticoid (hMR) receptors. This compound, (5Z)-5-[(2-fluoro-3-methylphenyl)methylene]-2,5-dihydro-10-methoxy-2,2,4-trimethyl-1H-[1]benzopyrano[3,4-f]quinolin-9-ol, has a molecular weight of 443.5 g/mole (C28H26FNO3).

Fig. 2.

Transcriptional activation and antagonist activity of LGD5552. (A) LGD5552 is not an agonist in the MMTV:luciferase reporter assay. Dexamethasone (filled circles) induces transcription from this promoter >1,000-fold. LGD5552 and RU486 exhibit <5% efficacy compared with dexamethasone. (B) LGD5552 is an antagonist of dexamethasone-mediated activation at MMTV. Dexamethasone is added at a half-maximal concentration of 0.3 nM Dex, and LGD5552 (open squares) or RU486 (filled squares) are titrated in dose–response. (C) LGD5552 and dexamethasone are highly efficacious at repression of the inflammatory marker E-selectin. The E-selectin promoter was induced with inflammatory stimuli (TNF and IL-1β), and compounds were added in dose–response. Strong repression is correlated with antiinflammatory activity. Consistent with their binding affinity, LGD5552 (ED50 = 2 nM, efficacy 100%) is less potent than dexamethasone (ED50 = 0.1 nM, efficacy 100%). However, LGD5552 is equally potent and efficacious as prednisolone in the E-selectin assay (Pred: ED50 = 4 nM, efficacy 98%) (data not shown).

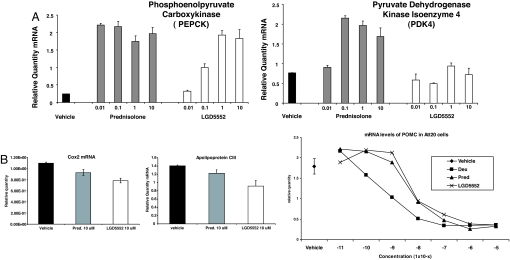

LGD5552 exhibits differential gene regulation of other genes across multiple cell lines, and it activates some genes similarly to steroidal glucocorticoids, whereas only weakly activating others that are strongly activated by glucocorticoids. To establish the impact of LGD5552 on GR-mediated transcriptional regulation of selected endogenous genes and to compare the results to prednisolone, we tested H4IIE liver cells containing endogenous GR for response to prednisolone and LGD5552. The compound exhibits differential gene regulation as demonstrated with the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4) and phosphoenol pyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) genes, both of which are likely involved in glucose homeostasis by using a PCR assay (Fig. 3). Treatment of H4IIE liver cells with prednisolone and LGD5552 resulted in an equal increase in the transcription of the PEPCK gene at the highest doses tested (Fig. 3A). However, prednisolone achieved maximal transcriptional activation at 0.01 μM, whereas LGD5552 was only fully active at concentrations ≥1.0 μM. The PDK4 gene exhibited a different profile (Fig. 3b). Prednisolone achieved maximal transcriptional activation of the PDK4 gene at 0.1 μM and maintained this level of transcriptional activation at all doses tested, whereas LGD5552 did not significantly increase transcription above the level of vehicle at any dose tested. We also tested two genes repressed by glucocorticoids in H4IIE cells, APOCIII and COX2. These genes were repressed by both glucocorticoid and LGD5552 (Fig. 3B). We went on to examine transcriptional repression by LGD5552 relative to prednisolone by using ATT20 cells measuring the response of the POMC gene to treatment. Similarly, this gene was potently and strongly repressed by the compounds (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Differential gene regulation of LGD5552 and prednisolone. H4IIE liver cells with endogenous GR were assayed for response to either prednisolone or LGD5552. RT-PCRs were used to quantify RNA from a variety of different genes. (A) (Left) Relative RNA levels for the PEPCK gene. (Right) Relative RNA levels for the PDK4. (B) (Left and Center) COX2 and APOCIII RNA levels were measured in response to vehicle, prednisolone, or LGD5552 in HEK293 cells transfected with hGR. (Right) POMC RNA was measured in ATT20 cells in response to vehicle, dexamethasone, prednisolone, or LGD5552 treatment in dose–response. Vehicle control is shown at the far left.

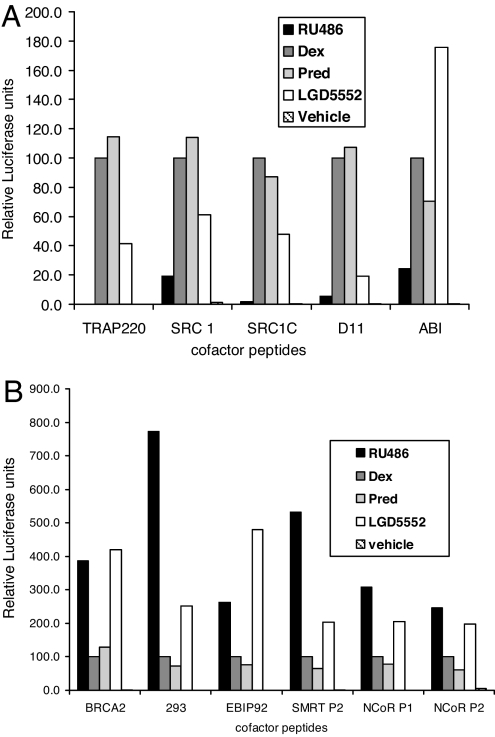

To understand the molecular mechanism of LGD5552 activity on GR, we undertook an analysis of the coactivator- and corepressor-binding profile of GR when bound to LGD5552 and the steroidal glucocorticoids by using a mammalian two-hybrid (M2H) assay system. This protein–protein assay utilizes both natural nuclear receptor interaction domains (LXXLL and LXXLL-like motifs) from coactivators and corepressors, as well as synthetic LXXLL motifs that interact with GR in the presence of glucocorticoids (12–14). These LXXLL motifs bind nuclear receptors in a cleft adjacent to helix 12 (15).

We tested the ability of ligand-bound GR to interact with these LXXLL motifs in response to LGD5552 and glucocorticoids by tethering the LXXLL-containing peptides to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain and assaying ligand-dependent activation from a GAL4:luciferase reporter. As shown in Fig. 4, LGD5552 exhibits a different interaction profile when compared with prednisolone, dexamethasone, and the antagonist, RU486.

Fig. 4.

Differential coactivator/corepressor interactions induced by LGD5552. M2H assay to measure ligand-dependent interaction between GR and various peptides. (A) M2H assay with GR and peptides that interact to a greater degree in the presence of the GR agonists, dexamethasone or prednisolone, than in the presence of the GR antagonist, RU486. (B) M2H assay with GR and peptides that interact to a greater degree in the presence of the GR antagonist, RU486, than in the presence of the GR agonists, dexamethasone or prednisolone.

In particular, differences between the GR steroidal agonists and LGD5552 are evident when the compound is tested with peptides corresponding to both the central and C-terminal LXXLL motifs of SRC-1, as well as LXXLL motifs from TRAP220 (16, 17). Furthermore, several synthetic peptides also interact differentially with GR bound to LGD5552 (D11 and ABI) (12, 13). The LXXLL motifs from SRC and TRAP 220 do not bind as efficiently to GR when LGD5552 is the ligand, compared with when prednisolone or dexamethasone is used. LGD5552 exhibits a profile reminiscent of the antagonist RU486 on several of the peptides studied. LXXLL-containing peptides BRCA2, 293, and EBIP92 interact with GR more strongly in the presence of both the antagonist and LGD5552 than with the glucocorticoids. LGD5552 consistently induces corepressor peptide interactions more efficiently than steroidal agonists. Thus, LGD5552 appears intermediate in its binding profile, inducing a conformation that has attributes of both agonist and antagonist structures.

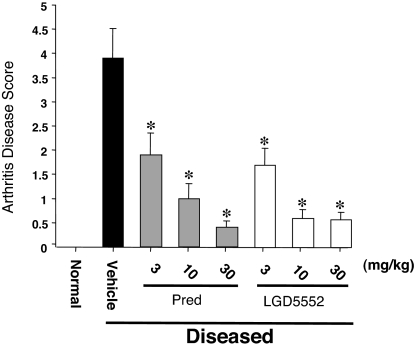

The results of our in vitro analysis suggest that there are significant differences between LGD5552 and the glucocorticoids. To ensure that this altered profile still has sufficient efficacy in vivo, we tested LGD5552 as an oral antiinflammatory agent in the CIA model (18). CIA is an animal model that shares certain clinical and pathological features with rheumatoid arthritis (18) and has been used to examine the mechanism and progression of the disease. This model utilizes acclimatized 6- to 8-week-old DBA mice injected into the tail vein with bovine type II collagen, together with complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) at days 1 and 7. Injected animals developed disease over the next 10 days based on a clinical signs scoring index from 0 to 4 for each limb (18). Oral administration of compounds began on day 17 after the onset of symptoms and continued through day 31 (15 days dosing). On day 31, animals were scored for clinical signs of arthritis (Fig. 5). The results indicate that no disease occurred in animals not injected with collagen and Mycobacterium (normal controls). Both prednisolone and LGD5552 were efficacious and decreased the clinical signs of arthritis in these animals at multiple doses. Treatment of animals after disease onset mimics the clinical situation where glucocorticoids are used in patients presenting with rheumatoid arthritis symptoms.

Fig. 5.

LGD5552 has full efficacy inhibiting CIA. The impact of treatment by vehicle, prednisolone, or LGD5552 on arthritis disease score in a mouse model of arthritis is shown. Animals injected with adjuvant and collagen develop severe disease (vehicle), whereas untreated animals (normal) do not. Glucocorticoids and LGD5552 are capable of blocking existing disease in these animals. Both compounds are active at <3 mg/kg. ∗, P < 0.05 versus vehicle. Statistical analysis used a one-way ANOVA followed by Fischer's LSD.

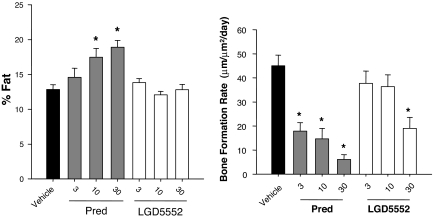

Similar efficacy of LGD5552, when compared with steroids, suggests that the antiinflammatory activity of the compound has not been significantly compromised by the alterations in its gene expression profile. Swiss–Webster mice treated for 28 days with glucocorticoid exhibit a number of steroid-related side effects, including increased percentage of body fat and decreased bone formation rate. Body fat was significantly higher in prednisolone-treated animals at both 10 and 30 mg/kg (Fig. 6A). In contrast, LGD5552 did not increase percentage of body fat relative to vehicle controls. Similarly, bone formation rate also was differentially affected by prednisolone and LGD5552. Prednisolone decreased bone formation rate at all doses tested, whereas LGD5552 only exhibited significant activity at the 30 mg/kg dose (Fig. 6B). Thus, LGD5552 exhibited reduced activity in mice, compared with prednisolone on both bone- and fat-related endpoints.

Fig. 6.

LGD5552 has less impact on bone formation and percentage of body fat than a steroid. Three-month-old male Swiss–Webster mice were treated orally with prednisolone or LGD5552 for 4 weeks. Treatment groups consisted of vehicle, prednisolone (3, 10, and 30 mg/kg), and LGD5552 (3, 10, and 30 mg/kg). Prednisolone (gray bars) raises the percentage of body fat at both 10 and 30 mg/kg, whereas LGD5552 (white bars) does not. Bone formation rate is significantly suppressed by prednisolone at all doses tested, whereas LGD5552 (white bars) suppresses at 30 mg/kg. LGD5552 is not significantly different from vehicle at 3 and 10 mg/kg.

Discussion

The effort to find selective GR modulators (SGRMs) has been ongoing for more than a decade (19). Compounds described to date have been both steroidal (20) and nonsteroidal (19, 21, 22) and have various activities that suggest a separation from steroidal side effects (5). Strong in vivo separation between efficacy and side effects is generally lacking in the published literature with a few exceptions: Schacke et al. (23) published separation in vivo for topical application, and Coghlan et al. (5, 6, 21, 22, 24) published separation between efficacy and side effects in vivo after oral administration. Others have published various nonsteroidal compounds with interesting activity in vitro (25–27) and some demonstrating antiinflammatory activity in vivo, but no side-effect data (27).

LGD5552 represents a new class of nonsteroidal SGRMs (Fig. 1). The compound has a steroid-like molecular weight of 443.5 g/mole, but exhibits less saturation in the rings, compared with the cholesterol-derived, fully saturated rings found in the steroids. In addition, the ring substituents differ significantly from the steroids. The size and generally planar crystal structure of LGD5552 suggest a molecule capable of binding directly in the GR ligand-binding domain. Direct interaction has been demonstrated by using a competitive binding assay. LGD5552 binds GR efficiently with nanomolar affinity (Fig. 1) and fails to interact strongly with other nuclear receptors (Fig. 1. and data not shown). The steroid receptor with the highest affinity for LGD5552 beside GR is the highly GR-related mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) (GR type I), which interacts with LGD5552 with a Ki of 150 nM. In contrast to steroids, however, the compound exhibits antagonist activity on MR, which may provide further differential activity in vivo.

Overlays can be made where the C5 benzylidene ring of LGD5552 overlaps that of the 11β-[p-(dimethylamino)phenyl] substituent on RU486 (28). This similarity not only applies to the chemical structure, but also, in some ways, to the function of LGD5552. In many assays, this compound exhibits significantly weaker transcriptional activation when compared with canonical glucocorticoid agonists (dexamethasone and prednisolone). In an extreme example of this finding, LGD5552 not only fails to induce MMTV:luciferase reporter activity, but is a strong antagonist of dexamethasone-induced activity on this reporter system (Fig. 2 A and B). However, the compound retains strong transcriptional repression activity on a number of genes, including TNFα/IL1β-induced transcription from the E-selectin promoter. Blockade of TNFα/IL1β signaling and blockade of E-selectin gene expression are hallmarks of the antiinflammatory action of steroids, suggesting that LGD5552 also should retain antiinflammatory activity.

Although significant differences are seen in the activation of the MMTV promoter, LGD5552 does not universally separate transcriptional activation from repression. This finding is different from the data obtained with specific mutations in the DNA-binding domain that exhibit much more separation between activation and repression (29). We have examined other genes that glucocorticoids are known to activate and have found a number of differing profiles for LGD5552. In particular, we have focused on the PEPCK and the PDK4 genes (Fig. 3). Regulation of blood glucose concentration by glucocorticoids in vivo is, in part, mediated by the effects on hepatic gluconeogenesis (30). PEPCK is the rate-limiting step in gluconeogenesis, and PDK4 acts to phosphorylate and inhibit pyruvate dehydrogenase, which metabolizes pyruvate into acetyl-CoA, preventing it from entering the gluconeogenic pathway (31). LGD5552 differentially regulates PEPCK and PDK4 gene expression, compared with prednisolone, which regulates the genes in concert. This result is striking because the binding affinities for GR of LGD5552 and prednisolone are similar (2.4 vs. 1.5 nM), and both compounds exhibit equal antiinflammatory activity on the inhibition of E-selectin expression.

This phenomenon of differential gene regulation induced by nonsteroidal GR ligands has been reported previously (7) and was attributed to selective interaction with differential activity on a number of coactivator peptides, suggesting a structural alteration in the coactivator-binding site structure in response to this ligand. The other major area of striking difference between steroidal agonists and LGD5552 is in the corepressor-binding profile. This compound induces better GR interaction with corepressor peptides than the steroidal agonists. This profile is similar, but not identical, to the profile of a known antagonist, RU486. Interactions with corepressors have been documented for GR previously in response to antagonists (32, 33). These results suggest that LGD5552-bound GR can adopt a conformation that also accommodates larger corepressor peptides (34). Transcriptional repression of critical inflammatory genes by glucocorticoids has been linked to interaction with corepressors in some cases (35) and coactivators in others (36).

To confirm our in vitro results, we determined the efficacy of LGD5552 relative to prednisolone by using the collagen-induced arthritis model in mice. This robust and relevant assay for rheumatoid arthritis maintains many of the characteristics of the human disease and has been used to test compounds from a variety of chemical classes (18, 24, 37). In this model, treatment was initiated only after animals exhibited disease, in much the same way a patient would seek treatment after the onset of symptoms. Treatment orally with either prednisolone or LGD5552 significantly decreased clinical signs of disease. Importantly, LGD5552 and prednisolone demonstrated dose-responsive efficacy at 3, 10, and 30 mg/kg. Oral antiinflammatory activity of an SGRM has been demonstrated previously, but the potency of this compound was weaker than prednisolone by 3-fold (7). Full efficacy and prednisolone-like potency in vivo for LGD5552 indicates that changes in the gene expression profile did not substantially affect the compound's antiinflammatory activity. To assess the potential for side effects at these doses, we used the same doses of compound to examine mice in a side-effect study where glucocorticoids have effects on bone formation rate and percentage of body fat. Fasting serum glucose was unaffected by either prednisolone or LGD5552 in this model (data not shown). Percentage of body fat as measured by DEXA was significantly increased as a result of prednisolone treatment at both the 10 and 30 mg/kg doses. In contrast, LGD5552 did not increase body fat significantly at any dose tested. We suspect that LGD5552 could act as an antagonist in this assay, but the window is not sufficient to reliably carry out such an experiment. Bone formation in these animals was also measured; as expected, prednisolone significantly decreased bone formation in the tibia at all doses tested. LGD5552 exhibited a weaker response on this endpoint, only producing significant suppression at 30 mg/kg and exhibiting no suppression at 3 and 10 mg/kg. These results suggest that, at fully antiinflammatory doses, LGD5552 exhibits less impact on certain side effects than prednisolone. This mouse model of glucocorticoid effects on bone and percentage of body fat represents known effects of glucocorticoids found in human studies.

LGD5552 binding to GR causes alterations in the coactivator/corepressor-binding profile, likely leading to the observed differential gene expression when compared with prednisolone. The compound is a potent and efficacious antiinflammatory agent when administered orally with a reduction in certain side effects. The discovery of a potent, selective GR ligand that significantly alters GR structure and function represents a step forward toward a SGRM that could be used to more safely treat inflammatory disease.

Materials and Methods

In Vitro Binding.

Extracts from SF-9 moth cells infected with recombinant baculovirus expressing the indicated receptor were used in labeled hormone-binding assays. Growth and purification of recombinant hGR baculovirus and binding assays followed the protocol as described (7).

Cotransfection Assays.

DMEM and Eagle's minimum essential media (EMEMs) were obtained from BioWhittaker. All FBS was purchased from HyClone. CV-1 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. The cells were maintained in culture with DMEM containing 10% FBS. Cells were seeded 24 h before transfection in T-225 flasks. Cells were transiently transfected with an expression plasmid containing the cDNA for hGR, pRShGR, a reporter plasmid, MMTV-LUC, containing the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) long-terminal repeat linked to luciferase, and filler DNA (pGEM) by using a nonliposomal formulation, the FuGene 6 transfection reagent (Roche) according to manufacturer's specifications. The Fugene 6/DNA mixture was added to the media, bathing the cells in T-225 flasks, and cells were incubated for 20 h at 37°C in a humidified incubator. Cells were plated into 96-well microtiter plates at a density of 10,000 cells per well.

Plasmids.

pRSV:hGRnx and MMTV:Luc were obtained from Ron Evans (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA). A reporter construct containing 600 bp of the E-selectin promoter region fused to the luciferase gene (E-Sel/luc) was used in repression assays, together with an expression vector encoding hGR driven by the Rous Sarcoma virus enhancer (RSV-hGR) cotransfected with a β-gal expression vector as a control. DMSO (Sigma–Aldrich), RNeasy mini-columns, RNA isolation and purification kits, and an RNase-Free DNase cleanup kit were obtained from Qiagen. SuperScript first-strand synthesis system for RT-PCR kit was obtained from Invitrogen. Real-time PCR master mix was obtained from Applied Biosystems International.

Compounds and Formulations.

LGD5552 was synthesized at Ligand Pharmaceuticals, and RU486 and prednisolone were purchased from Steraloids. Both LGD5552 and prednisolone were formulated for animal studies in a solution consisting of 50% olive oil and 50% carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) in water (0.2% CMC in water). Calcein and alizarin red (Sigma–Aldrich) were used for bone labeling. Calcein was dissolved in 2% NaHCO3, and alizarin red was dissolved in sterile water.

Two-Hybrid Assay.

GAL4 DNA-binding, domain-peptide fusions were constructed by first synthesizing oligonucleotides coding for the following protein sequences: VESGSSRLMQLLMANDLLT, D11; GPQTPQAQQKSLLQQLLTE, SRC1-C; SKGHKKLLQLLTCSSDD, SRC3–1; RTHRLITLADHICQIITQDFARN, NCoR peptide 1; DPASNLGLEDIIRKALMGSFDDK, NCoR peptide 2; GHQRVVTLAQHISEVITQDYTRH, SMRT peptide 1; HASTNMGLEAIIRKALMGKYDQW, SMRT peptide 2. For experiments using Gal4 peptides, experiments were conducted as described (38, 39). Transfections were carried out by using FuGene 6 per the manufacturer's protocol. After 24 h incubation at 37°C with compound at 1 μM, cells were lysed and assayed for luciferase and β-gal activity. All values shown are the mean of three wells and are representative of multiple experiments.

Gene Expression Analysis.

H4IIE rat liver carcinoma cells and ATT20 cells from the American Type Culture Collection (no. 234536) were carried in 10% FBS, seeded overnight in six-well plates at 3.5 × 105 cells per well in modified Dulbecco's medium, and obtained from Cambrex with 10% FBS. FBS and dextran/charcoal-treated FBS were purchased from HyClone. The next day, media were aspirated, and vehicle or compounds were introduced in 10% dextran/charcoal-treated FBS. Cells were incubated for 24 h and then lysed for RNA extraction and purification (RNeasy isolation kit). The RNA was quantified, and first-strand c-DNA was prepared by using an Invitrogen first-strand synthesis kit. Real-time PCRs were conducted by using an ABI 7700 at single reporter detector in 96-well standard format with a 50-μl reaction volume. The PCR conditions were 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C, and then 1 min at 60°C. All target gene data were normalized by using the unregulated control gene, 36B4. Normalization was done by dividing the value obtained from each target gene sample by the 36B4 gene value obtained for that sample. Triplicate biological samples and triplicate assays for each dose were run. Primers and probes for RT-PCR were as follows: PEPCK forward primer, 5′ ggc gca ctg gct gag cat 3′; reverse primer, 5′ ggc gca ctg gct gag cat 3′; probe, 5′ acc gcc cag cag cca agt tgc 3′; PDK4 forward primer, 5′ cac ctt cac cac atg ctc ttt ga 3′; reverse primer, 5′ gcc tcg act ggt gtc agg aaa 3′; probe, 5′ ttc aag aat gcc atg agg gcc acg 3′; 36B4 forward primer, 5′ctc cag agg tac cat tga aat cct3′; reverse primer, 5′gat gtt caa cat gtt cag cag tgt3′; probe, 5′agg ctg tgg tgc tga tgg gca ag3′; COX2 forward primer, COX2–950F, 5′ cca gca ggc tca tac tga tag ga 3′; reverse primer, COX2–1090R, 5′ caa tgc ggt tct gat act gga a 3′; probe, COX2–989(+), 5′ tga tcg aag act acg tgc aac acc tga gg 3′; POMC probe, agagcaacctgctggcttgcatcc; forward primer, ctcctgcttcagacctccataga; reverse primer, agaggtcgagtttgcaagcc. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA by using Dunnett's method for comparison of means.

CIA Mouse Model.

DBA/1 mice (female, 6–8 weeks old; The Jackson Laboratory) underwent a quarantine, acclimatization, and acceptance period of 10 days. The assay was conducted over the next 31 days. On day 1, mice were injected with bovine type II collagen dissolved and stored in 0.01 M acetic acid at 4 mg/ml (50 μm per mouse), together with CFA (Difco), intradermally at the base of the tail. The injection was repeated at day 7. The animals developed disease over the next 10 days. During days 17–31, the animals were dosed daily with vehicle, prednisolone, and LGD5552 by oral gavage (15 days dosing). There were eight groups with 10 mice per group. Mice were scored for clinical signs of arthritis and grades ranging from 0–4 (18, 40): grade 0, no visible abnormalities; grade 1, mild redness or swelling of wrist or up to three inflamed digits; grade 2, more than three inflamed digits or moderate redness and swelling of ankle or wrist; grade 3, severe ankle and wrist inflammation; grade 4, extensive ankle and wrist inflammation, including all digits, or new bone formation with reduced motion. A maximum score of 16 could be achieved for each mouse. The data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, followed by Fisher's LSD. P < 0.05 was the level necessary to achieve statistical significance.

Four-Week Mouse Study.

Three-month-old male Swiss–Webster mice (Harlan) were treated orally with prednisolone or LGD5552 for 4 weeks. Throughout the experiment, animals were singly housed, maintained on a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle (lights on at 0600 hours), and fed standard mouse chow ad libitum (Teklad 8604 containing 1.36% calcium, 1.01% phosphorus, and 2.40 units·units−1·g−1 vitamin D3). Mice were scanned by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA; Lunar) 3 days before the start of the experiment and were stratified into treatment groups by total body bone mineral density. A second DXA scan was performed 3 days before necropsy. Data from this scan were used to calculate percentage of body fat. Treatment groups consisted of vehicle, prednisolone (3, 10, and 30 mg/kg), and LGD5552 (3, 10, and 30 mg/kg). After 28 days of treatment, animals were killed by cardiac exsanguination under isoflurane anesthesia, and bones were harvested for analysis. All procedures involving animals were approved by Ligand's or Washington Biotechnology's Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee.

Cortical Bone Histomorphometry.

To fluorochrome label bones for histomorphometric analysis, mice received an s.c. injection of 30 mg/kg alizarin red at the time of the baseline DXA scans and an s.c. injection of 15 mg/kg calcein at the time of the final DXA scan. Specimens for histomorphometry were stored in 70% ETOH before processing. Bones were dehydrated in ascending concentrations of ETOH, cleared in xylene, and embedded undecalcified in methyl methacrylate. Transverse sections of the midfemoral dipahysis were cut with a low-speed saw (Isomet; Buehler), mounted on plastic slides, and manually ground to a thickness of ≈30 μm on a rotary grinder (Buehler). Static and dynamic histomorphometry was performed under epifluorescent illumination with a digital camera attached to a microscope (Leica Microsystems). Image quantification was performed with commercially available software (BioQuant NovaPrime) (41, 42). Primary measured indices included periosteal perimeter, medullary perimeter, tissue area, medullary area, cortical thickness, periosteal double-labeled surface, and interlabel width. Calculated indices included cortical area (cortical area = tissue area − medullary area), mineral apposition rate (MAR = interlabel width/days between injections), and periosteal bone formation rates (BFR = double-labeled surface × MAR/periosteal perimeter) (43).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors are or were employed by Ligand Pharmaceuticals.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Rosen J, Miner JN. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:452–464. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collingwood TN, Urnov FD, Wolffe AP. J Mol Endocrinol. 1999;23:255–275. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0230255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrlich P. Oncogene. 2001;20:2465–2475. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwasaki K, Mishima E, Miura M, Sakai N, Shimao S. J Dermatol Sci. 1995;10:151–158. doi: 10.1016/0923-1811(95)00401-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miner JN, Hong MH, Negro-Vilar A. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;14:1527–1545. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.12.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vayssiere BM, Dupont S, Choquart A, Petit F, Garcia T, Marchandeau C, Gronemeyer H, Resche-Rigon M. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1245–1255. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.9.9979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coghlan MJ, Jacobson PB, Lane B, Nakane M, Lin CW, Elmore SW, Kym PR, Luly JR, Carter GW, Turner R, et al. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:860–869. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin CW, Nakane M, Stashko M, Falls D, Kuk J, Miller L, Huang R, Tyree C, Miner JN, Rosen J, et al. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:297–303. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang JC, Shah N, Pantoja C, Meijsing SH, Ho JD, Scanlan TS, Yamamoto KR. Genes Dev. 2006;20:689–699. doi: 10.1101/gad.1400506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coghlan MJ, Kym PR, Elmore SW, Wang AX, Luly JR, Wilcox D, Stashko M, Lin CW, Miner J, Tyree C, et al. J Med Chem. 2001;44:2879–2885. doi: 10.1021/jm010228c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tegley CM, Zhi L, Marschke KB, Gottardis MM, Yang Q, Jones TK. J Med Chem. 1998;41:4354–4359. doi: 10.1021/jm980366a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang CY, McDonnell DP. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:647–660. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.4.0818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang C, Norris JD, Gron H, Paige LA, Hamilton PT, Kenan DJ, Fowlkes D, McDonnell DP. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8226–8239. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurebayashi S, Nakajima T, Kim SC, Chang CY, McDonnell DP, Renaud JP, Jetten AM. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;315:919–927. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darimont BD, Wagner RL, Apriletti JW, Stallcup MR, Kushner PJ, Baxter JD, Fletterick RJ, Yamamoto KR. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3343–3356. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han SJ, DeMayo FJ, Xu J, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:45–55. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito M, Roeder RG. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:127–134. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anthony DD, Haqqi TM. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1999;17:240–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schacke H, Rehwinkel H, Asadullah K. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;6:503–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doggrell SA. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;14:823–828. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.7.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barker M, Clackers M, Copley R, Demaine DA, Humphreys D, Inglis GG, Johnston MJ, Jones HT, Haase MV, House D, et al. J Med Chem. 2006;49:4216–4231. doi: 10.1021/jm060302x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Bosscher K, Vanden Berghe W, Beck IM, Van Molle W, Hennuyer N, Hapgood J, Libert C, Staels B, Louw A, Haegeman G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15827–15832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505554102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schacke H, Schottelius A, Docke WD, Strehlke P, Jaroch S, Schmees N, Rehwinkel H, Hennekes H, Asadullah K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:227–232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0300372101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Dios A, Shih C, Lopez de Uralde B, Sanchez C, del Prado M, Martin Cabrejas LM, Pleite S, Blanco-Urgoiti J, Lorite MJ, Nevill CR, Jr, et al. J Med Chem. 2005;48:2270–2273. doi: 10.1021/jm048978k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith CJ, Ali A, Balkovec JM, Graham DW, Hammond ML, Patel GF, Rouen GP, Smith SK, Tata JR, Einstein M, et al. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:2926–2931. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson CF, Quraishi N, Ali A, Tata JR, Hammond ML, Balkovec JM, Einstein M, Ge L, Harris G, Kelly TM, et al. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:2163–2167. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali A, Thompson CF, Balkovec JM, Graham DW, Hammond ML, Quraishi N, Tata JR, Einstein M, Ge L, Harris G, et al. J Med Chem. 2004;47:2441–2452. doi: 10.1021/jm030585i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ulmann A, Teutsch G, Philibert D. Sci Am. 1990;262:42–48. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0690-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reichardt HM, Kaestner KH, Tuckermann J, Kretz O, Wessely O, Bock R, Gass P, Schmid W, Herrlich P, Angel P, Schutz G. Cell. 1998;93:531–541. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Link JT. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;4:421–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Savkur RS, Bramlett KS, Michael LF, Burris TP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;329:391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frego L, Davidson W. Protein Sci. 2006;15:722–730. doi: 10.1110/ps.051781406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Y, Kawate H, Ohnaka K, Nawata H, Takayanagi R. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6633–6655. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01534-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang D, Simons SS., Jr Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1483–1500. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jee YK, Gilmour J, Kelly A, Bowen H, Richards D, Soh C, Smith P, Hawrylowicz C, Cousins D, Lee T, Lavender P. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23243–23250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503659200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rogatsky I, Luecke HF, Leitman DC, Yamamoto KR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16701–16706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262671599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paul-Clark MJ, Mancini L, Del Soldato P, Flower RJ, Perretti M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1677–1682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022641099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Langley E, Kemppainen JA, Wilson EM. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:92–101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langlands K, Yin X, Anand G, Prochownik EV. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19785–19793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.19785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams RO. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114:330–332. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00785.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turner RT, Hannon KS, Demers LM, Buchanan J, Bell NH. J Bone Miner Res. 1989;4:557–563. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650040415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wakley GK, Schutte HD, Jr, Hannon KS, Turner RT. J Bone Miner Res. 1991;6:325–330. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650060403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baylink D, Stauffer M, Wergedal J, Rich C. J Clin Invest. 1970;49:1122–1134. doi: 10.1172/JCI106328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]