Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) efficiently capture HIV-1 and mediate transmission to T cells, but the underlying molecular mechanism is still being debated. The C-type lectin DC-SIGN is important in HIV-1 transmission by DCs. However, various studies strongly suggest that another HIV-1 receptor on DCs is involved in the capture of HIV-1. Here we have identified syndecan-3 as a major HIV-1 attachment receptor on DCs. Syndecan-3 is a DC-specific heparan sulfate (HS) proteoglycan that captures HIV-1 through interaction with the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. Syndecan-3 stabilizes the captured virus, enhances DC infection in cis, and promotes transmission to T cells. Removal of the HSs from the cell surface by heparinase III or by silencing syndecan-3 by siRNA partially inhibited HIV-1 transmission by immature DCs, whereas neutralizing both syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN completely abrogated HIV-1 capture and subsequent transmission. Thus, HIV-1 exploits both syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN to mediate HIV-1 transmission, and an effective microbicide should target both syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN on DCs to prevent transmission.

Sexual transmission is the main route of HIV-1 dissemination and accounts for 80% of new HIV-1 infections (1). The sequential events that take place from the moment the virus hits the mucosal wall until systemic HIV-1 infection is established remain obscure. Because cell-free particles ineffectively cross genital epithelial cells (2), it has been postulated that HIV-1 employs dendritic cells (DCs) to penetrate the mucosal epithelium (3–5).

DCs capture pathogens in the peripheral tissues and migrate into the lymphoid tissues to prime T cells to initiate immune responses (6). DCs are the first immune cells to encounter HIV-1 in the genital mucosa (7). DCs extend their dendrites into the lumen of mucosal cavities to sense pathogens such as HIV-1 (8). It has been proposed that HIV-1 hijacks DCs in the mucosal tissues to be transported to lymph nodes, where the virus is transferred to T cells, leading to an explosive viral replication (3, 4, 9).

DCs, in vitro, efficiently bind HIV-1 (10) and transfer the virus to T cells (3, 4, 11). The initial interactions between HIV-1 and DCs are not fully clarified yet. HIV-1 binds to DCs. However, the identity of the HIV-1 receptors on DCs is currently under intense debate (11–15). Different receptors have been demonstrated to interact with HIV-1 on DCs, such as the C-type lectin DC-SIGN (11, 16), the mannose receptor (17), langerin (18), and CD4 (17). Most of these experiments have been carried out by using HIV-1 glycoprotein gp120. Experiments using HIV-1 particles, rather than recombinant gp120, have suggested that other unknown receptors are involved (13–15).

In this study, we set out to identify the attachment receptors for HIV-1 on DCs. We demonstrate that syndecan-3 is an HIV-1 receptor that is highly expressed by DCs. Syndecan-3, a heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG), captures HIV-1 specifically through interaction by its HS chains, enhances the endurance of the virus, and promotes HIV-1 transmission to T cells. Neutralization of both syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN impairs HIV-1 binding to DCs and transfer to T cells. By identifying syndecan-3 as a DC-specific attachment receptor for HIV-1, this study sheds light on the interplay among HIV-1, DCs, and T cells.

Results

HIV-1 Exploits Trypsin-Sensitive Molecules Other than DC-SIGN to Bind DCs.

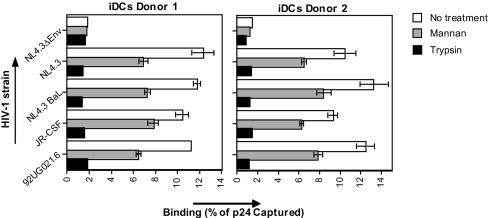

To investigate the receptors for HIV-1 on DCs, we used immature monocyte-derived DCs that express intermediate levels of HLA-DR, CD86, and low levels of CD83. These cells express high levels of DC-SIGN and mannose receptor, intermediate levels of HIV-1 entry receptors CD4, CCR5, and low levels of CXCR4 [supporting information (SI) Fig. 8A]. Therefore, these DCs mostly resemble the subepithelial and dermal DCs (17, 19, 20). We investigated the interaction of DCs with various HIV-1 strains, such as R5-tropic (NL4.3-BaL and JR-CSF), X4-tropic (NL4.3 and 92UG021.6), and gp120-deficient (NL4.3ΔEnv) viruses. Viruses were all produced in peripheral blood monocytic cells (PBMCs) to mimic the physiological in vivo environment for virus production because it has been shown that viruses produced in 293T cells acquire a distinct binding phenotype (21). DCs captured HIV-1 efficiently (8–15% of the input virus), and no significant difference between R5- and X4-tropic viruses was observed (Fig. 1). DCs interacted with the virus specifically through gp120 because the gp120-deficient virus did not bind DCs (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

HIV-1 exploits trypsin-sensitive molecules other than DC-SIGN to bind DCs. The 0.25 × 106 cells per ml DCs were preincubated with 1 mg/ml mannan or trypsin, exposed to 1 ng of p24 HIV-1 [strains NL4.3 Δ-envelope, NL4.3 (X4), NL4.3BaL (R5), JR-CSF (R5), or NL-92UG021.6 (X4)] for 2 h at 37°C, washed, and lysed, and the p24 content of lysate was measured by ELISA. Results are expressed in percentage of p24 captured relative to the inoculum. Error bars represent the standard deviation of duplicates (n = 3 donors).

To determine involvement of C-type lectins, DCs were preincubated with mannan. Mannan partially blocked HIV-1 binding to DCs (Fig. 1), confirming that C-type lectin receptors partly contribute to HIV-1 binding to DCs (11, 17). Trypsin reduced HIV-1 binding close to background levels (Fig. 1), suggesting that HIV-1 interacts with C-type lectins, as well as with an unidentified trypsin-sensitive receptor.

Neutralizing antibodies directed against CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 did not inhibit HIV-1 binding to DCs (SI Fig. 8B), indicating that DCs express a functional HIV-1 receptor distinct from C-type lectin and entry receptors.

HSPGs Mediate Attachment of HIV-1 to DCs.

HSPGs mediate attachment of HIV-1 to adherent cells such as macrophages, endothelial cells, and epithelial cells (2, 21, 22–24). In contrast, HSPGs do not mediate HIV-1 attachment to suspension cells because of the fact that suspension cells such as monocytes, T lymphocytes, and B lymphocytes poorly express HSPGs (2, 21, 24). The cell-surface expression of HSPGs on DCs has not been reported to date.

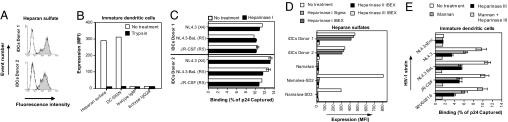

We thus analyzed HS expression of DCs. As previously shown (22), monocytes did not express HS (data not shown). Interestingly, immature DCs expressed high HS levels (Fig. 2A). Moreover, trypsin removed both HS and DC-SIGN (Fig. 2B). Therefore, we hypothesized that HS mediates the C-type lectin-independent binding of HIV-1 to DCs.

Fig. 2.

HSPGs mediate attachment of HIV-1 to DCs. (A) DCs were analyzed for HS expression by FACS. Open histograms represent isotype control; filled histograms represent specific antibody staining. (B) DCs were treated with trypsin and stained for DC-SIGN (DCN46) and HS (10E4). Expression is depicted as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). (C) DCs were pretreated or not with heparinase I, exposed to 1 ng of p24 HIV-1 for 2 h at 37°C, washed, and lysed, and the p24 content was measured by ELISA. Results are expressed as percentage of p24 captured relative to the inoculum. Error bars represent the standard deviation of duplicates. (D) DCs as well as parental-, syndecan-2-, and syndecan-3-transfected Namalwa cells were treated with heparinase I, II, and III and stained for HS. (E) DCs were pretreated with heparinase III, mannan, or a combination of both; exposed to 1 ng of p24 HIV-1 for 2 h at 37°C; washed; and lysed; and the p24 content was measured by ELISA. Results are expressed as percentage of p24 captured relative to the inoculum. Error bars represent the standard deviation of duplicates (n = 3 donors).

DCs have been claimed to capture HIV-1 independently of HSPGs (15). Specifically, HIV-1 binding to DCs was not inhibited by heparinase I (15). We confirmed that heparinase I does not prevent the binding of HIV-1 to DC (Fig. 2C), whereas it prevents HIV-1 binding to cell lines expressing HSPGs (21). To determine whether heparinase I removes HS from DCs, cells were stained for HS before and after heparinase I treatment. Strikingly, heparinase I did not affect HS staining on DCs (SI Fig. 9), in contrast to HS on cell lines (SI Fig. 9) (21). Thus, DCs express HSs that are resistant to heparinase I, and therefore heparinase I cannot be used to examine the role of HS as a potential HIV-1 receptor on DCs. In contrast to heparinase I, heparinase II and III reduced HS expression on DCs to background levels (Fig. 2D). We thus used heparinase III to study the interaction of HIV-1 with HSPGs on DCs.

To determine the role of HS in HIV-1 capture by DCs, DCs were pretreated with heparinase III. Heparinase III blocked HIV-1 binding to DCs, indicating that HSs are major receptors for HIV-1 on DCs (Fig. 2E). The combination of heparinase III and mannan inhibited HIV-1 binding to levels similar to those of the gp120-deficient virus (Fig. 2E), suggesting that HIV-1 exploits both HS and C-type lectins to bind to DCs.

Syndecan-3 Is the Major HSPG Expressed by DCs.

Human cells express two families of HSPGs: syndecans and glypicans (25). The syndecans are the major family of HSPGs expressed by macrophages (22). We investigated which family of HSPGs contributes to the HS expression on DCs. DCs were treated with either heparinase III, which removes HS chains linked to HSPGs, or phospholipase C, which removes proteins attached by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor, including glypicans, but not syndecans. Similar to macrophages, heparinase, but not phospholipase C, removed HS from DCs (SI Fig. 10A), demonstrating that syndecans, but not glypicans, represent the major source of HS on DC. The staining of CD14, a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein, was lost after phospholipase C treatment (SI Fig. 10A), confirming the efficacy of the enzymatic treatment. DC-SIGN expression was not affected by heparinase, validating the specificity of the enzymatic treatment (SI Fig. 10A). Thus, DCs express high HS levels, which are mostly contributed by syndecans.

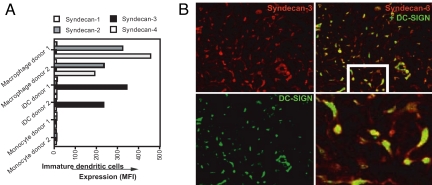

The syndecan family consists of four members: syndecan-1 to syndecan-4 (26). We investigated which members of the syndecan family are expressed by DCs. As previously described, monocytes lack syndecans, whereas macrophages express high levels of syndecan-2 and syndecan-4, variable levels of syndecan-1, but no detectable levels of syndecan-3 (Fig. 3A) (22). In sharp contrast, immature DCs express high levels of syndecan-3, but not syndecan-1, syndecan-2, and syndecan-4 (Fig. 3A and SI Fig. 10B).

Fig. 3.

Syndecan-3 represents the main HSPG on DCs. (A) Monocytes, macrophages, and immature DCs were stained with antibodies against syndecan-1 (1D4), syndecan-2 (10H4), syndecan-3 (1C7), syndecan-4 (8G3), and DC-SIGN (AZN-D1) and analyzed by FACS (n = 10 donors). The expression is depicted as MFI. Open histograms represent isotype control; filled histogram specific antibody staining. (B) Cryosections of human cervix were stained for syndecan-3 (1C7, red color) and DC-SIGN (DCN-46, green color) and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy.

We investigated whether syndecan-3 expresses HS. Syndecan-3 immunoprecipitated from a DC lysate by using an anti-syndecan-3 antibody is specifically recognized by an anti-HS antibody, demonstrating that syndecan-3 is not only abundantly expressed by DCs, but also sulfated (SI Fig. 10C). Supporting our in vitro data, syndecan-3 was highly expressed on DCs that reside in cervical tissue (Fig. 3B), whereas syndecan-1, syndecan-2, and syndecan-4 were absent (data not shown). We observed a significant colocalization between syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN, but interestingly also a distinct cellular localization: Syndecan-3 localizes in the dendrites and at the center of the cell, whereas DC-SIGN mainly localizes at the center of the cell. Altogether these in vitro and in situ data suggest that syndecan-3 is the main HSPG expressed by DCs.

The HS Chains of Syndecan-3 Bind HIV-1.

To assess the potential of syndecan-3 to serve as an HIV-1 receptor, we examined the capacity of Namalwa transfectants expressing DC-SIGN or syndecan-3 to capture HIV-1. Parental Namalwa cells did not bind HIV-1 (SI Fig. 11A), whereas both Namalwa DC-SIGN and Namalwa syndecan-3 transfectants bound HIV-1 (SI Fig. 11A). To analyze the specificity of the receptors, cells were treated with mannan or heparinase III. The binding of HIV-1 to DC-SIGN was blocked with mannan, but not with heparinase III (SI Fig. 11A), whereas binding of HIV-1 to syndecan-3 was inhibited with heparinase III, but not with mannan (SI Fig. 11A). This finding indicates that mannan and heparinase III are specific methods to investigate HIV-1-binding capacities of DC-SIGN and syndecan-3.

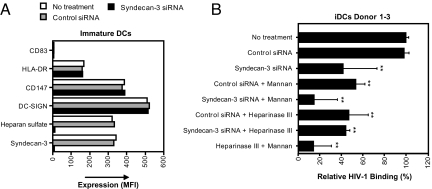

To further determine the role of syndecan-3 for HIV-1 binding to DCs, we silenced syndecan-3 by siRNA. DCs were transfected with control or syndecan-3 siRNA. siRNA transfection did not alter the phenotype of DCs (Fig. 4A). The knockdown was complete because expression of both syndecan-3 and HS was lost after siRNA transfection (Fig. 4A). Knockdown of syndecan-3 blocked HIV-1 binding to DCs to similar levels as we observed with heparinase III. Heparinase III did not further reduce the binding compared with syndecan-3 knockdown, indicating that syndecan-3 is the major HSPG that binds HIV-1 to DCs (Fig. 4B). Among different donors, differences were observed for the respective contribution of syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN to HIV-1 binding by DCs (SI Fig. 11B). However, in all donors, neutralization of both DC-SIGN and syndecan-3 resulted in binding levels that were similar to background levels as observed for the gp120-deficient virus (data not shown), suggesting that syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN are the major receptors for HIV-1 on immature DCs.

Fig. 4.

HIV-1 binds to DCs by the HS chains of syndecan-3. (A) DCs were transfected with control or syndecan-3 siRNA; stained with antibodies against CD83 (HB-15E), HLA-DR (G46–6), DC-SIGN (DCN46), syndecan-3 (1C7), and HS (10E4); and analyzed by FACS. (B) DCs were transfected with control or syndecan-3 siRNA, treated with heparinase III or mannan, exposed to 1 ng of p24 NL4.3 (X4) for 2 h at 37°C, washed, and lysed, and the p24 content was measured by ELISA. Results are expressed in percentage of p24 captured relative to the initial inoculum. The results were normalized to the no treatment control, and the mean of three different donors is depicted as relative HIV-1 binding. Error bars represent standard deviation of three donors, and the means were analyzed by ANOVA. **, P < 0.01, versus the no treatment condition.

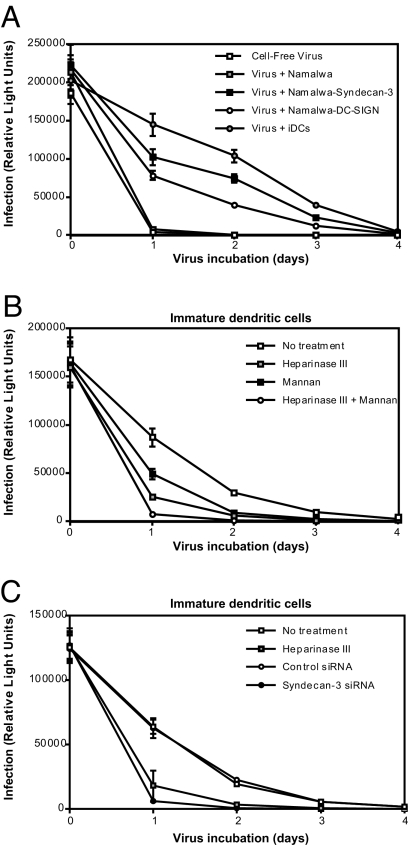

HIV-1 Captured by DCs by Syndecan-3 Retains Infectivity After Long-Term Culture.

HIV-1 bound to syndecan-2 on cell lines retains its infectivity for days (21). Similarly, HIV-1 bound to DC-SIGN expressing cell lines or DCs retains infectivity for >4 days (10, 11). However, it is becoming clear that most of the virus is degraded (27, 28). We investigated whether the binding of HIV-1 to syndecan-3 results in viral protection or degradation. We compared the resistance of cell-free HIV-1 to that of HIV-1 bound to DCs or Namalwa transfectants expressing DC-SIGN or syndecan-3. At different time points, supernatant containing free virus or virus-pulsed cells were collected and added to TZM reporter cells to determine the infectivity and endurance of cell-free and cell-associated viruses. Cell-free viruses or viruses incubated with parental Namalwa cells lost infectivity after a single day, whereas HIV-1 incubated with DC-SIGN transfectants retained infectivity for days (Fig. 5A). Importantly, HIV-1 incubated with Namalwa syndecan-3 cells or DCs retained infectivity for >3 days (Fig. 5A). Both syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN were involved in preserving infectivity of HIV-1 bound to DCs because DCs pretreated with heparinase III, syndecan-3 siRNA, or mannan exhibited reduced levels of viral protection (Fig. 5 B and C). Small differences in the respective contribution of syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN were observed among donors. However, for all donors, the binding and retention of infectivity depended on both receptors (SI Fig. 12). Thus, syndecan-3 not only mediates HIV-1 attachment to DCs, but it also preserves infectivity of captured particles.

Fig. 5.

Binding of HIV-1 to syndecan-3 on DCs retains infectivity after long-term culture. DCs as well as 0.25 × 106 cells per milliter parental-, syndecan-3-, and DC-SIGN-transfected Namalwa cells were exposed to 1 ng p24 NL4.3 (X4) for 2 h at 37°C, washed, and cultured at 37°C. Every day, aliquots of HIV-1-pulsed Namalwa cells were added to TZM cells. As a control, an amount of virus, identical to the virus initially attached to the cells, was incubated at 37°C in medium without cells. TZM infection was scored after 2 days. (B) DCs were treated with heparinase III, mannan, or the combination of both before virus exposure. (C) DCs were transfected with control or syndecan-3 siRNA or pretreated with heparinase III before virus exposure. The previous experiments are representative of three independent experiments by using three different DC donors.

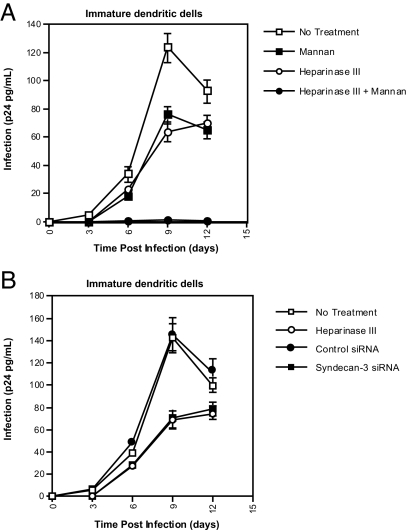

Syndecan-3 Enhances HIV-1 Infection of DCs.

Syndecans and C-type lectin receptors do not mediate entry of HIV-1 (11, 21). However, these receptors enhance infection in cis by serving as attachment receptors (22, 29, 30). To investigate the role of syndecan-3 in DC infection, cells were pretreated with heparinase III before HIV-1 exposure. Infection was monitored by measuring amounts of p24 released into DC culture. Although virus production is weak compared with T cells, DCs were productively infected, and the infection peaked at day 9 (Fig. 6). Heparinase III and syndecan-3 silencing reduced HIV-1 infection (Fig. 6 and SI Fig. 13). Thus, syndecan-3 enhances HIV-1 infection of DCs probably by promoting virus attachment and/or endurance. The combination of heparinase III and mannan profoundly hampered DC infection (Fig. 6A), demonstrating that both syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN are the predominant attachment receptors for HIV-1 on DCs and enhance DC infection in cis.

Fig. 6.

Syndecan-3 facilitates HIV-1 infection of DCs. The 0.1 × 106 cells per milliter DCs were transfected with control or syndecan-3 siRNA; treated with heparinase III, mannan, or a combination of both; and were exposed to 1 ng of p24 NL4.3 (X4). After 1 day, cells were washed and replated in a 96-well plate. Viral replication was monitored by p24 ELISA. Error bars represent the standard deviation of duplicates. These experiments are representative of three independent experiments by using three different DC donors.

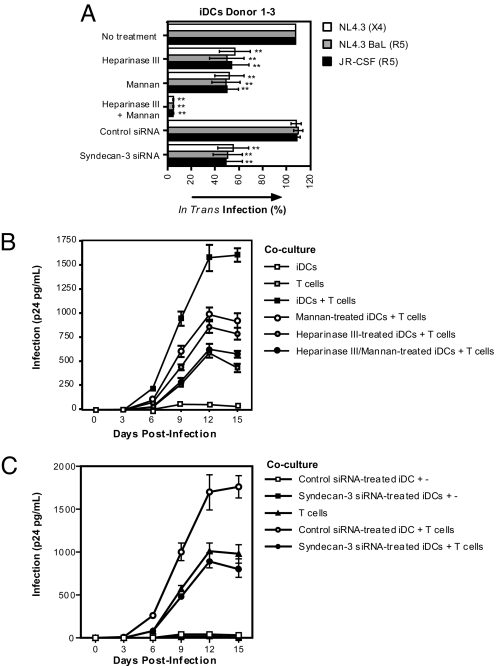

Syndecan-3 Promotes HIV-1 Transmission by DCs to T Cells.

DCs mediate transmission to T cells of captured virus, a process referred to as in trans infection as well as de novo-produced viruses (11, 27). To determine whether syndecan-3 is involved in in trans transmission, we used TZM cells, which permit the detection of early events of HIV-1 transmission independently of de novo-produced virus. DCs pulsed with HIV-1 efficiently transfer viruses to TZM cells (Fig. 7A). Importantly, syndecan-3 enhances DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission because pretreatment of DCs with heparinase III or syndecan-3 siRNA reduced TZM infection (Fig. 7A). The respective contribution of syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN to HIV-1 transmission was donor-dependent (SI Fig. 13) because neutralization of these receptors by heparinase III or mannan resulted in different proportions of block of infection among different DC donors. A combination of heparinase III and mannan inhibited viral transmission to levels similar to those of the gp120-deficient virus (data not shown), indicating that both syndecan-3 and C-type lectin receptors are crucial for HIV-1 transmission (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

HSPGs and C-type lectins mediate HIV-1 transmission by DCs. (A) The 0.25 × 106 cells per milliter DCs were transfected with control or syndecan-3 siRNA; treated with heparinase III, mannan, or the combination of both; and exposed to 1 ng of p24 HIV-1. After 2 h, cells were washed and titrated on TZM cells to determine transmission. To compare the data of the different virus, results are depicted relative to the transmission observed with untreated DCs. The means of three different donors are depicted. Error bars represent standard deviation of three donors, and the means were analyzed by ANOVA. **, P < 0.01, versus no treatment control. (B and C) The 0.1 × 106 cells per millilter DCs were transfected with control or syndecan-3 siRNA; treated with heparinase III, mannan, or the combination of both; and exposed to 1 ng of p24 NL4.3 (X4). Without washing, T cells were added, and cocultures were plated in 96-well plates. Supernatants were collected after different days, and viral replication was monitored by p24 ELISA. As controls, DCs were cultured without T cells, and T cells without DCs were infected with the initial inoculum as for DCs. Error bars represent the standard deviation of duplicates.

The addition of DC- or DC-SIGN-expressing cell lines to T cells enhances T cell infectivity (3, 4, 11). We investigated whether syndecan-3 is involved in the enhancement of HIV-1 replication in a DC–T cell coculture system. As previously shown, DCs enhance HIV-1 replication in T cells (Fig. 7 B and C and SI Fig. 14B). Both syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN are important for viral enhancement because heparinase III or mannan inhibited the enhancement of infection. Combinational neutralization of both receptors blocked the DC-mediated enhanced HIV-1 infection of T cells to levels of T cells alone (Fig. 7 B and C and SI Fig. 14B). These data demonstrate that on DCs both syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN are crucial for HIV-1 transmission.

Discussion

In this study, we clarified the initial interactions of HIV-1 with immature DCs. We identified syndecan-3 as a major attachment receptor for HIV-1 on DCs. Syndecan-3 captures HIV-1, stabilizes the virus, enhances DC infection in cis, and promotes transmission to T cells. Furthermore, we demonstrated that neutralization of both syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN inhibits viral capture and transmission to background levels. We thus conclude that syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN are the major receptors for HIV-1 on DCs.

It is well accepted that DCs mediate HIV-1 transmission. However, the underlying mechanisms and receptors involved in these processes have been under serious debate. We demonstrated that HIV-1 is primarily captured by syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN. Both classes of receptors are important because inhibition of both receptors was necessary to obtain a complete block of HIV-1 capture and transmission.

A recent study excluded HSPGs as HIV-1 receptors on DCs because heparinase I did not inhibit viral capture by DCs (15). Indeed, heparinase I did not inhibit HIV-1 binding to DCs. However, we showed that heparinase I failed to remove HS on DCs, in contrast to heparinase II and III. This enzymatic specificity is not proteoglycan-dependent because heparinase I digests HS on macrophages (22), HeLa cells (23, 31), and syndecan-expressing Namalwa cells (21), suggesting that HS composition on DCs differs from that on other cells. Heparinase I cleaves HS at the level of some highly O-sulfated disaccharides, heparinase III cleaves only at hexosaminic linkages with glucuronic acid in nonsulfated or N-sulfated disaccharides, and heparinase II cleaves a variety of HS forms (32). Thus, HSs from syndecan-3 on DCs are differentially sulfated. The particular composition also suggests a specific regulatory function of HS on DCs because the degree and pattern of sulfation in HS dictate syndecans' binding-specificity (33).

The fact that syndecan-3 is expressed by DCs is striking because syndecan-3 expression has only been described in the nervous system (32). During wound healing, syndecan-1, syndecan-2, and syndecan-4 bind different chemokines and matrix proteins (32, 34). Thus, binding of HIV-1 to syndecan-3 on DCs might affect DC function. Moreover, syndecan-3 might have a specific function in the immune system and influence viral transmission in vivo. We showed that syndecan-3 localizes in the dendrite-like arms of cervical DCs, whereas DC-SIGN localizes at the center of the cell. This finding is reminiscent of the localization of syndecan-2 in dendritic spines of neurons (35). Because DCs within the Lamina propria (8) extend their dendritic processes into the lumen of the vagina (36), our findings suggest that HIV-1 exploits syndecan-3, richly expressed by dendrites and breaching the epithelial surface, to hijack DCs.

Previous studies identified C-type lectins, especially DC-SIGN, as major DC receptors for HIV-1 (11, 17, 37), whereas others challenged these observations (10, 13, 15, 38, 39). These apparent discrepancies may result from the fact that some studies used recombinant gp120 (11, 17, 37), whereas others used virus particles (13, 15). Moreover, divergent sources of viruses for DC-binding studies might have contributed to these conflicting observations. We and others have shown that gp120-deficient viruses derived from 293T, but not from T cells, bind to target cells (21, 23). Similarly, we found here that gp120-deficient viruses derived from T cells failed to bind to DCs (Fig. 1), whereas gp120-deficient viruses derived from 293T cells bind to DCs (data not shown). This finding demonstrates that DC-binding studies using viruses derived from 293T cells, rather than from physiological T cells, should be analyzed with caution. Another possibility for conflicting results is the use of different DC culture protocols. Specifically, we observed a strong reduction in HS when DCs were grown with decreased IL-4 levels, resulting in less differentiated DCs (data not shown).

The route of HIV-1 after its initial capture by DCs also is under debate. A recent report concluded that primarily cell-surface-bound HIV-1 is transferred to T cells (40), whereas previous studies have shown that mainly the internalized virus is transferred (37). These latter reports demonstrated that, although a large part of the virus is degraded in lysosomes (27, 28), part of the virus recycles to infectious synapse (41, 42) or exosomes (43). Because we now demonstrate that HIV-1 is captured by both syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN, which are receptors with distinct functions, it is tempting to speculate that these receptors contribute to different internalization routes.

Our work demonstrates that HIV-1 exploits both syndecan-3 and C-type lectin receptors to bind to DCs. A microbicide-targeting virus capture by DCs should thus act on both classes of receptors. Alternatively, it would be appealing to design compounds that target gp120 and block virus binding to both syndecan-3 and DC-SIGN. However, the domains in gp120 required for HIV-1–syndecan and HIV-1–C-type lectins are distinct. An arginine located in the third variable region of gp120 is necessary for HIV-1–syndecan interactions (44), whereas mannose residues on the immunologically silent face of gp120 are necessary for HIV-1–C-type lectin interactions (45). Recent failures of clinical trials using microbicides to prevent HIV-1 transmission demonstrate the complexity of HIV-1 transmission and indicate that more knowledge is needed to develop an effective microbicide (46). It is imperative to develop compounds that specifically prevent HIV-1–syndecan-3 interactions to exclusively examine the role of syndecan-3 in HIV-1 capture and transfer by DCs.

Experimental Procedures

Enzymatic Treatments.

In the heparinase treatment, 5 × 106 cells per ml were treated with 10 milliunits heparinase I, II, and III (IBEX, Montreal, Canada) or heparinase I (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in PBS/0.25% BSA for 1 h at 25°C. Cells were washed and used for subsequent experiments. In the trypsin treatment, 5 × 106 cells per ml were washed and treated with 0.05% of trypsin/EDTA buffer (Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 15 min at 37°C. In the phospholipase treatment, removal of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked proteins by phospholipase C (Sigma–Aldrich) was performed as described previously (22).

siRNA.

The 1 × 106 cells per ml DCs were transfected on day 6 of culture with control or syndecan-3 siRNAs, which is a pool of three target-specific 20- to 25-nt siRNA designed to knock down the syndecan-3 gene (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) by using the human DC nucleofactor kit (Amaxa Corproation, Gaithersburg, MD). Procedures were conducted following the manufacturer's instructions. After 2 days, DCs were washed and analyzed for syndecan-3 and HS expression and immediately used in subsequent experiments.

Viruses.

293T cells were transfected with 9 μg of proviral and 1 μg of VSV-G plasmids. At day 3, viruses were harvested and used to infect activated PBMCs. At day 3, viruses were harvested, and the p24 content was measured by ELISA (PerkinElmer Instruments, Norwalk, CT). The following proviral constructs were used: pNL4.3 (X4); pNL4.3-BaL (R5), in which NL4.3 Env was switched for the BaL Env (gift from D. Trono, Global Health Institute, Lausanne, Switzerland) (47); pNL4.3-ΔEnv (gift from C. Aiken, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN); JR-CSF isolate (contributed by I. Chen, University of California, Los Angeles); and pNL-92UG021.6, in which NL4.3 Env was switched for the primary X4 92UG021.6 Env (gift from P. Bieniasz, The Rockefeller University, New York) (48).

Immunofluorescence Stainings.

Paraffin sections of paraformaldehyde-fixed material (4% in 0.1 M phosphate buffer) were blocked with PBS containing 1% BSA and 10% goat serum and incubated at 4°C with 10 μg/ml of anti-CD209 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and 25 μg/ml of 1C7. Primary antibodies were detected with Alexa-conjugated antibodies (Invitrogen) 1:1,000 in PBS/BSA/goat serum. Images were obtained by confocal microscopy.

Syndecan-3-Specific HS ELISA.

The 10 × 106 cells per millilter DCs were lysed in PBS/1% TX-100, and 10 μg/ml antibodies against a syndecan-3 (1C7) were coated onto ELISA plate. After blocking with PBS/5%BSA, wells were incubated with DC lysate in PBS/5%BSA for 12 h at 4°C. After washing, 5 μg/ml 10E4, the HS antibody, was added for 2 h at 25°C. Antibody binding was detected by using an antibody specifically against mouse IgM conjugated with peroxidase.

HIV-1 Capture, Transmission, and Protection Assay.

DCs or Namalwa cells were treated with heparinase, phospholipase C, or trypsin, as described earlier, and washed. The 0.25 × 106 cells per ml per 500-μl cells were then preincubated with 1 mg/ml mannan or 20 μg/ml blocking antibodies for 30 min at 37°C and exposed to 1 ng of p24 virus. After 2 h, cells were washed. To determine viral capture, cells were lysed, and capsid content in cell lysate was measured by p24 ELISA as described previously (21). To determine viral transmission, HIV-1-pulsed cells were titrated on TZM cells. To determine HIV-1 protection, HIV-1 pulsed cells were cultured for 1 week, and, at different time points, cell aliquots were collected and titrated for infectivity on TZM cells as described previously (49).

HIV-1 Infection and Enhancement Assay.

The 0.1 × 106 cells per ml DCs were pretreated with heparinase III and, subsequently, with 1 mg/ml mannan for 30 min at 37°C. For infection assay, cells were exposed to 1 ng of p24 virus for 1 day, washed, and cultured in a 96-well plate. For enhancement assay, cells were incubated with 1 ng of p24 virus for 2 h at 37°C, and T cells were subsequently added. Supernatants were collected after different days, and viral replication was monitored by p24 ELISA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Saal van Zwanenbergstichting. This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grant AI 071952 (to P.G.) and Dutch Scientific Research Program NWO 917–46-367 (to T.B.H.G.).

Abbreviations

- DC

dendritic cell

- gp

glycoprotein

- HS

heparan sulfate

- HSPG

HS proteoglycan

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- PBMC

peripheral blood monocytic cell.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0703747104/DC1.

References

- 1.Royce RA, Sena A, Cates W, Jr, Cohen MS. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1072–1078. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bobardt MD, Chatterji U, Selvarajah S, Van der Schueren B, David G, Kahn B, Gallay PA. J Virol. 2007;81:395–405. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01303-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron PU, Freudenthal PS, Barker JM, Gezelter S, Inaba K, Steinman RM. Science. 1992;257:383–387. doi: 10.1126/science.1352913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pope M, Betjes MG, Romani N, Hirmand H, Cameron PU, Hoffman L, Gezelter S, Schuler G, Steinman RM. Cell. 1994;78:389–398. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cameron PU, Lowe MG, Crowe SM, O'Doherty U, Pope M, Gezelter S, Steinman RM. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;56:257–265. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patterson BK, Landay A, Siegel JN, Flener Z, Pessis D, Chaviano A, Bailey RC. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:867–873. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64247-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rescigno M, Urbano M, Valzasina B, Francolini M, Rotta G, Bonasio R, Granucci F, Kraehenbuhl JP, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:361–367. doi: 10.1038/86373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Kooyk Y, Geijtenbeek TB. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:697–709. doi: 10.1038/nri1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trumpfheller C, Park CG, Finke J, Steinman RM, Granelli-Piperno A. Int Immunol. 2003;15:289–298. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geijtenbeek TBH, Kwon DS, Torensma R, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GCF, Middel J, Cornelissen IL, Nottet HS, KewalRamani VN, Littman DR, et al. Cell. 2000;100:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turville SG, Arthos J, Mac Donald K, Lynch G, Naif H, Clark G, Hart D, Cunningham AL. Blood. 2001;98:2482–2488. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granelli-Piperno A, Pritsker A, Pack M, Shimeliovich I, Arrighi JF, Park CG, Trumpfheller C, Piguet V, Moran TM, Steinman RM. J Immunol. 2005;175:4265–4273. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurney KB, Elliott J, Nassanian H, Song C, Soilleux E, McGowan I, Anton PA, Lee B. J Virol. 2005;79:5762–5773. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5762-5773.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gummuluru S, Rogel M, Stamatatos L, Emerman M. J Virol. 2003;77:12865–12874. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.23.12865-12874.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arrighi JF, Pion M, Wiznerowicz M, Geijtenbeek TB, Garcia E, Abraham S, Leuba F, Dutoit V, Ducrey-Rundquist O, van Kooyk Y, et al. J Virol. 2004;78:10848–10855. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.10848-10855.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turville SG, Cameron PU, Handley A, Lin G, Pohlmann S, Doms RW, Cunningham AL. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:975–983. doi: 10.1038/ni841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Witte L, Nabatov A, Pion M, Fluitsma D, de Jong MA, de GT, Piguet V, van Kooyk Y, Geijtenbeek TB. Nat Med. 2007;13:367–371. doi: 10.1038/nm1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ebner S, Ehammer Z, Holzmann S, Schwingshackl P, Forstner M, Stoitzner P, Huemer GM, Fritsch P, Romani N. Int Immunol. 2004;16:877–887. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jameson B, Baribaud F, Pohlmann S, Ghavimi D, Mortari F, Doms RW, Iwasaki A. J Virol. 2002;76:1866–1875. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.4.1866-1875.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bobardt MD, Saphire AC, Hung HC, Yu X, Van der Schueren B, Zhang Z, David G, Gallay PA. Immunity. 2003;18:27–39. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saphire AC, Bobardt MD, Zhang Z, David G, Gallay PA. J Virol. 2001;75:9187–9200. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.19.9187-9200.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mondor I, Ugolini S, Sattentau QJ. J Virol. 1998;72:3623–3634. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3623-3634.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bobardt MD, Salmon P, Wang L, Esko JD, Gabuzda D, Fiala M, Trono D, Van der Schueren B, David G, Gallay PA. J Virol. 2004;78:6567–6584. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6567-6584.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.David G. FASEB J. 1993;7:1023–1030. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.11.8370471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallay P. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:617–622. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turville SG, Santos JJ, Frank I, Cameron PU, Wilkinson J, Miranda-Saksena M, Dable J, Stossel H, Romani N, Piatak M, Jr, et al. Blood. 2004;103:2170–2179. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nobile C, Petit C, Moris A, Skrabal K, Abastado JP, Mammano F, Schwartz O. J Virol. 2005;79:5386–5399. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5386-5399.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee B, Leslie G, Soilleux E, O'Doherty U, Baik S, Levroney E, Flummerfelt K, Swiggard W, Coleman N, Malim M, et al. J Virol. 2001;75:12028–12038. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12028-12038.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burleigh L, Lozach PY, Schiffer C, Staropoli I, Pezo V, Porrot F, Canque B, Virelizier JL, Renzana-Seisdedos F, Amara A. J Virol. 2006;80:2949–2957. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2949-2957.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saphire AC, Bobardt MD, Gallay PA. EMBO J. 1999;18:6771–6785. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gallagher JT, Turnbull JE, Lyon M. Biochem Soc Trans. 1990;18:207–209. doi: 10.1042/bst0180207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esko JD, Lindahl U. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:169–173. doi: 10.1172/JCI13530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimmermann P, David G. FASEB J. 1999;13(Suppl):S91–S100. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.9001.s91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ethell IM, Yamaguchi Y. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:575–586. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.3.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller CJ, McChesney M, Moore PF. Lab Invest. 1992;67:628–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon DS, Gregorio G, Bitton N, Hendrickson WA, Littman DR. Immunity. 2002;16:135–144. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baribaud F, Pohlmann S, Leslie G, Mortari F, Doms RW. J Virol. 2002;76:9135–9142. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9135-9142.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boggiano C, Manel N, Littman DR. J Virol. 2007;81:2519–2523. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01661-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cavrois M, Neidleman J, Kreisberg JF, Greene WC. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e4. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDonald D, Wu L, Bohks SM, KewalRamani VN, Unutmaz D, Hope TJ. Science. 2003;300:1295–1297. doi: 10.1126/science.1084238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arrighi JF, Pion M, Garcia E, Escola JM, van Kooyk Y, Geijtenbeek TB, Piguet V. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1279–1288. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiley RD, Gummuluru S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:738–743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507995103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Parseval A, Bobardt MD, Chatterji A, Chatterji U, Elder JH, David G, Zolla-Pazner S, Farzan M, Lee TH, Gallay PA. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39493–39504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504233200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hong PW, Nguyen S, Young S, Su SV, Lee B. J Virol. 2007;81:8325–8336. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01765-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Check E. Nature. 2007;446:12. doi: 10.1038/446012b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gallay P, Hope T, Chin D, Trono D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9825–9830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parent SA, Zhang T, Chrebet G, Clemas JA, Figueroa DJ, Ky B, Blevins RA, Austin CP, Rosen H. Gene. 2002;293:33–46. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00722-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chatterji U, Bobardt MD, Stanfield R, Ptak RG, Pallansch LA, Ward PA, Jones MJ, Stoddart CA, Scalfaro P, Dumont JM, et al. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40293–40300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506314200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.