Abstract

13C NMR is a powerful tool for monitoring metabolic fluxes in vivo. The recent availability of automated dynamic nuclear polarization equipment for hyperpolarizing 13C nuclei now offers the potential to measure metabolic fluxes through select enzyme-catalyzed steps with substantially improved sensitivity. Here, we investigated the metabolism of hyperpolarized [1-13C1]pyruvate in a widely used model for physiology and pharmacology, the perfused rat heart. Dissolved 13CO2, the immediate product of the first step of the reaction catalyzed by pyruvate dehydrogenase, was observed with a temporal resolution of ≈1 s along with H13CO3−, the hydrated form of 13CO2 generated catalytically by carbonic anhydrase. In hearts presented with the medium-chain fatty acid octanoate in addition to hyperpolarized [1-13C1]pyruvate, production of 13CO2 and H13CO3− was suppressed by ≈90%, whereas the signal from [1-13C1]lactate was enhanced. In separate experiments, it was shown that O2 consumption and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle flux were unchanged in the presence of added octanoate. Thus, the rate of appearance of 13CO2 and H13CO3− from [1-13C1]pyruvate does not reflect production of CO2 in the TCA cycle but rather reflects flux through pyruvate dehydrogenase exclusively.

Keywords: carbon dioxide, heart, hyperpolarization, NMR spectroscopy, pyruvate

Noninvasive measures of flux through specific enzyme-catalyzed reactions remain an important goal in physiology and clinical medicine. Standard radionuclide imaging methods do not provide information about individual reactions because the measured signal represents the weighted sum of the tracer plus the biochemical products produced by tissue. 13C NMR spectroscopy is much more powerful in this regard because it can easily differentiate between specific 13C-labeled products of biochemical reactions (1). The sensitivity enhancement gained by hyperpolarization of 13C nuclei (2) offers the possibility of using noninvasive 13C NMR spectroscopy and imaging to measure fluxes through individual enzyme-catalyzed reactions. [1-13C1]Pyruvate, for example, is a substrate that is avidly metabolized in most tissues. The individual metabolic products of this tracer, [1-13C1]lactate, [1-13C1]alanine, and H13CO3−, can be separately detected in vivo because of the inherent chemical shift dispersion of 13C NMR (3). Because decarboxylation of [1-13C1]pyruvate via pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) must produce 13CO2, the appearance of H13CO3− potentially directly reflects flux through PDH. A substantially reduced H13CO3− signal in hearts after coronary occlusion and reflow was previously attributed to an effect of transient ischemia on the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (3). However, it is known that the heart switches rapidly among a wide variety of substrates to supply acetyl-CoA (4, 5), and because fats and ketones are not metabolized via PDH the rate of production of H13CO3− from [1-13C1]pyruvate in vivo should be sensitive to the availability of other substrates.

Noninvasive detection of flux through PDH would unquestionably be of value in understanding potentially high-impact therapies for heart disease. Pharmacological and metabolic interventions that would be expected to increase flux through PDH have been examined since the 1960s with the goal of protecting ischemic myocardium (6–9) or improving function in the failing heart (10, 11). However, because of the complex interconnections between fatty acid and carbohydrate oxidation, it has been difficult to separate effects of metabolism through a specific reaction, PDH, from effects on oxygen consumption, myocardial efficiency, and overall TCA cycle flux in intact hearts. Despite intensive investigations, the clinical value of these interventions remains controversial (12).

In this study, metabolism of hyperpolarized [1-13C1]pyruvate was monitored in isolated rat hearts where, in contrast to the in vivo situation, substrate concentrations are easily controlled. Fatty acids were used to modulate PDH flux. Propionate, a three-carbon fatty acid, converts >90% of PDH to the active, phosphorylated form and stimulates PDH flux (13), whereas even-carbon fatty acids strongly inhibit PDH (13–15). Experiments were performed under ideal conditions for detecting downstream metabolites (only hyperpolarized pyruvate was available to the heart) and conditions in which competing even- and odd-carbon fatty acids were available. Dynamic observations in the intact heart were correlated with separate experiments performed on the bench to obtain direct measures of enzyme fluxes and oxygen consumption. Metabolism of [1-13C1]pyruvate to [1-13C1]alanine, [1-13C1]lactate, and H13CO3− was confirmed, and, for the first time, the immediate decarboxylation product of [1-13C1]pyruvate, 13CO2, was detected with 1-s temporal resolution. Addition of competing substrates dramatically inhibited the appearance of both 13CO2 and H13CO3−, yet citric acid cycle flux was unchanged. These observations demonstrate that hyperpolarized 13C NMR may be used for real-time detection of unidirectional fluxes in single reactions in functioning hearts.

Results

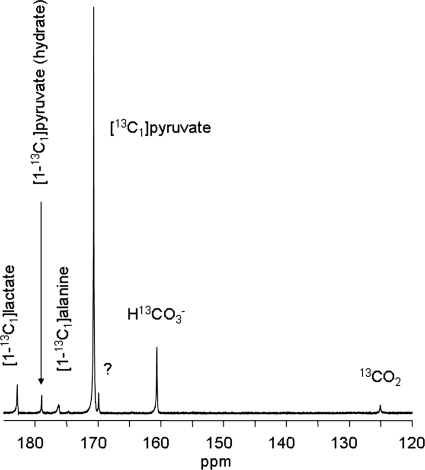

A typical 13C NMR spectrum from a heart supplied with 2 mM hyperpolarized [1-13C1]pyruvate was dominated by the resonance from pyruvate C1 (170.6 ppm) (Fig. 1). The resonances due to lactate C1 (183.2 ppm), alanine C1 (176.5 ppm), pyruvate hydrate C1 (179.0 ppm), bicarbonate (160.9 ppm), and 13CO2 (124.5 ppm) were easily observed. Individual spectra with 1-s time resolution demonstrating the kinetics of appearance of pyruvate, lactate, and bicarbonate are shown in Fig. 2, left column, after switching from unlabeled pyruvate to hyperpolarized [1-13C1]pyruvate. Because the metabolite pool sizes were already established, the appearance of [1-13C1]lactate does not represent net synthesis but instead reflects exchange of labeled pyruvate into the lactate pool (16).

Fig. 1.

13C NMR spectrum of an isolated rat heart. This spectrum is the sum of 100 scans. Resonances assigned to dioxane (external standard, 67.4 ppm), CO2, HCO3−, pyruvate C1, lactate C1, alanine C1, and pyruvate hydrate C1. The resonance labeled with the question mark at 169.2 ppm is an impurity in the pyruvate.

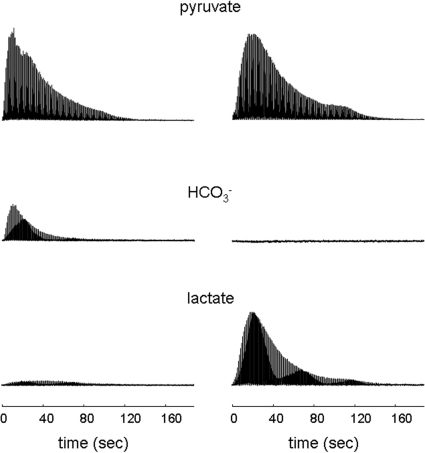

Fig. 2.

Stacked plot of 13C NMR spectra from hearts supplied with [1-13C1]pyruvate. Each resonance is a single scan from the chemical shift ± ≈10 Hz from the region assigned to pyruvate C1, H13CO3−, or lactate C1. The Left column is from a heart supplied with [1-13C1]pyruvate. The Right column is from a heart supplied with [1-13C1]pyruvate plus unlabeled octanoate.

Oxygen consumption (in micromoles per gram dry weight per minute) in each group was as follows: pyruvate, 29.2 ± 4.6; pyruvate plus octanoate, 43.2 ± 4.9; and pyruvate plus octanoate plus propionate, 39.0 ± 4.9. Oxygen consumption was slightly higher in the hearts supplied with octanoate because of the known oxygen wasting effects of fatty acids. Octanoate dramatically increased the signal from [1-13C1]lactate and suppressed appearance of H13CO3− (Fig. 2). There was little effect on the kinetics of alanine appearance and 13CO2 was undetectable in all hearts supplied with octanoate (data not shown). Thus, reduced appearance of 13CO2 or H13CO3− does not reflect a change in myocardial oxygen consumption.

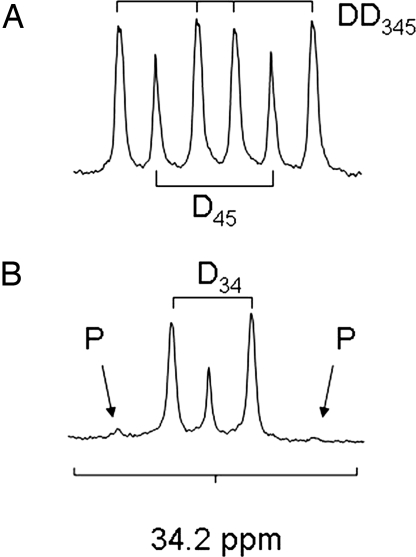

13C NMR spectra of the C4 resonance of glutamate collected from heart tissue extracts are shown in Fig. 3. The 13C-labeling patterns in pyruvate and octanoate used in these experiments were selected because the more complex patterns allow measurement of oxidation of endogenous energy stores, pyruvate, and octanoate simultaneously from a single 13C NMR spectrum. These spectra are easily interpreted because [1,2-13C2]acetyl-CoA is derived from [U-13C3]pyruvate and, after turnover in the TCA cycle, produces the characteristic multiplets in Fig. 3A due to the presence of scalar coupling between enriched 13C nuclei. [2-13C1]Acetyl-CoA is derived exclusively from [2,4,6,8-13C4]octanoate and produces glutamate multiples that are easily distinguished. An isotopomer analysis of the full 13C NMR spectrum (data not shown), allowed an estimate of the rates of pyruvate carboxylation and oxidation of unenriched sources of acetyl-CoA such as triglycerides and glycogen. In all experiments, the multiplets in alanine and lactate due to exchange of [U-13C1]pyruvate with these metabolite pools were easily detected and demonstrate metabolism of the tracer in the cytosol (data not shown). Models of lactate production in tumors as detected by hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate already exist.††

Fig. 3.

Proton-decoupled 13C NMR spectrum of the C4 resonance of glutamate in heart tissue extracts. (A) The spectrum taken from a heart supplied with [U-13C3]pyruvate, shows multiplets in the glutamate C4 due to TCA cycle turnover. From the chemical shift and J coupling pattern, all of the 13C signal is due to oxidation of [1-13C]pyruvate. (B) Spectrum taken from a heart supplied with [U-13C3]pyruvate and [2,4,6,8-13C4]octanoate. The C4 resonance of glutamate was changed from a six-line multiplet due to oxidation of [U-13C3]pyruvate, to a multiplet dominated by a singlet and a doublet, due to oxidation of [2,4,6,8-13C4]octanoate. P, resonance due to oxidation of pyruvate; Dxx, doublets or doublet of doublets, derived from J-coupling between the appropriate 13C-labeled positions of glutamate.

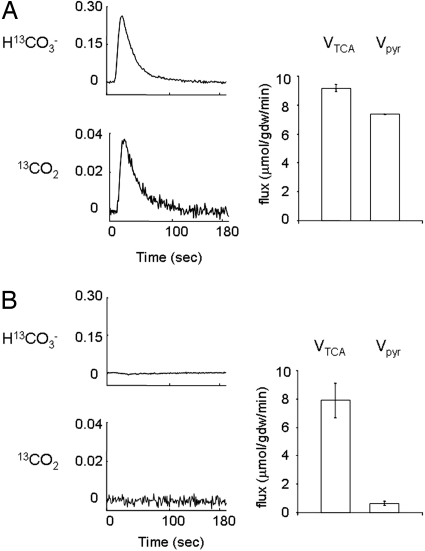

The complete 13C isotopomer analysis of these spectra (17, 18) indicated that 80 ± 2% of the acetyl-CoA entering the TCA cycle was derived from [U-13C3]pyruvate in the hearts supplied exclusively with pyruvate and that this fraction was reduced dramatically to 8 ± 1% in the presence of octanoate. Total flux through the combined anaplerotic reactions involving TCA cycle intermediates was <5% of TCA cycle flux. The analysis also indicated that very little pyruvate entered the TCA cycle pools via direct carboxylation in those hearts where octanoate was also present (Fig. 4). Total TCA cycle flux, Vtca, was not different between hearts supplied with pyruvate (9.18 ± 0.27 μmol/g dry weight per min) compared with hearts supplied with pyruvate and octanoate (7.89 ± 1.21 μmol/g dry weight per min. However, flux through PDH, Vpyr, was inhibited almost completely, from 7.37 ± 0.03 μmol/g dry weight per min in hearts supplied with pyruvate compared with 0.66 ± 0.13 μmol/g dry weight per min in hearts supplied with pyruvate and octanoate (P < 0.0001). Flux from octanoate into the TCA cycle, Voct, was correspondingly high in the latter group, 6.02 ± 1.93 μmol/g dry weight per min. By definition, flux of unlabeled sources of acetyl-CoA, triglycerides, and glycogen, Vunlab, is equal to Vtca − Vpdh − Voct, or ≈1.5 μmol/g dry weight per min. There was no difference in oxidation of endogenous substrates between groups.

Fig. 4.

Effect of octanoate on appearance of 13CO2 and H13CO3−. The average 13C NMR signals from dissolved 13CO2 and H13CO3− are shown relative to the maximum pyruvate signal from hearts supplied with [1-13C1]pyruvate (A) or [1-13C1]pyruvate plus octanoate and propionate (B). Data are the mean signal from three to four hearts acquired each second. Standard deviation was ≈10%; the error bars are omitted for clarity. Flux through PDH and the citric acid cycle are shown to the right. Under conditions in which 13CO2 and H13CO3− do not appear in the intact heart, independent measurements made by using isotopomer analysis of freeze-clamped hearts showed near-complete suppression of PDH flux, but no significant effect on TCA cycle flux.

The intensity of the H13CO3− and 13CO2 resonances reached a maximum at ≈20 s after injection of hyperpolarized [1-13C1]pyruvate and the ratio of resonance areas, H13CO3−/13CO2, was 7.3 ± 0.5, and constant (±7%) until T1 relaxation began to destroy the 13CO2 signal, rendering accurate estimates of its intensity impossible at longer times. To demonstrate that exchange between the two pools is rapid, each resonance was selectively saturated for 1 s before excitation and detection. After saturation of the H13CO3− resonance, the 13CO2 signal was undetectable, and after saturation of the 13CO2 resonance, the H13CO3− signal was reduced by 36% ± 3%. This demonstrates bidirectional exchange between these two species. Together with the known high activity of carbonic anhydrase (19), these observations demonstrate that H13CO3− ⇔ 13CO2 interconversion is rapid under these conditions.

Discussion

In view of the worldwide increase in prevalence of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and ischemic heart disease, better methods for evaluating the metabolic state of the heart are vital. NMR spectroscopy in combination with 13C tracers has been used to monitor intermediary metabolism in intact hearts for some time (20–22). Notwithstanding the rich information in a single 13C spectrum, 13C NMR spectroscopy is limited by low sensitivity. The demonstration that hyperpolarized metabolites may be detected after administration of hyperpolarized [1-13C1]pyruvate offers a fundamentally new method to assess cardiac metabolism (3, 23, 24). Pyruvate is a particularly attractive compound for metabolic studies using hyperpolarization for two reasons. First, the T1 relaxation time for the C1 position of pyruvate is long (40 s at 14.1 T), which means the polarized nuclei can potentially undergo many reactions before the NMR signal returns to thermal equilibrium and becomes undetectable. Also, pyruvate easily passes into the cytosol where biochemical reactions can take place. Here, we used 13C NMR to monitor metabolism of hyperpolarized [1-13C1]pyruvate in the intact heart under different metabolic conditions. These observations were integrated with high-resolution spectroscopy of extracts from hearts studied under the same conditions but with different 13C-labeling patterns to probe multiple pathways simultaneously (17, 18). With pyruvate as the sole available substrate, ≈80% of all acetyl-CoA entering the TCA cycle is derived from pyruvate, whereas flux through pyruvate carboxylase is small, ≈5% of TCA cycle flux. There was no difference in TCA cycle flux between hearts supplied exclusively with pyruvate compared with pyruvate plus octanoate, but the rate of appearance of 13CO2 and H13CO3− was very sensitive to the available substrate. In the presence of octanoate, 13CO2 and H13CO3− appearance was nearly abolished and did not recover even in the presence of propionate, a potent activator of PDH.

Because heart tissue avidly metabolizes pyruvate in the TCA cycle, the absence of signals from 13CO2 or H13CO3− in a heart supplied with [1-13C1]pyruvate plus octanoate might at first suggest that TCA cycle activity is impaired. However, an isotopomer analysis showed that the TCA cycle was equally active in the presence of all substrate mixtures, and hence the absence of signals from hyperpolarized 13CO2 or H13CO3− can be directly attributed to very effective competition of octanoate with pyruvate for supplying acetyl-CoA to the heart. Pyruvate could also potentially enter the TCA cycle via pyruvate carboxylation (17, 25), yet the isotopomer analysis demonstrated that flux of pyruvate through this pathway was negligible. Thus, rate of appearance of H13CO3− (or 13CO2) from [1-13C1]pyruvate does not reflect TCA cycle activity but rather flux through PDH. Because the myocardium is capable of rapidly switching among a wide variety of substrates to provide acetyl-CoA (4, 5) and it has long been known that substrates such as octanoate compete effectively in providing acetyl-CoA, the observations reported here are not particularly surprising. However, it is noteworthy that hyperpolarized [1-13C1]pyruvate produces detectable H13CO3− in heart tissue even when hearts are exposed to physiological mixtures of fatty acids, ketones, lactate, and glucose in vivo (3). The current observations emphasize the need to cautiously interpret the appearance of H13CO3− because changes in the concentration of either plasma free fatty acids or catecholamines may alter β-oxidation and influence the availability of alternate sources of acetyl-CoA.

The ability to detect both HCO3− and dissolved CO2 may offer a new method to evaluate pH in the functioning heart. Carbonic acid, H2CO3, has two acidic hydrogens with dissociation constants pKa1 ≈ 3.60 and pKa2 ≈ 10.25. Although the chemical shift of H13CO3− has been used to measure pH in the range of 8–10 (26), the chemical shift of H13CO3− in the physiological range of the heart will be insensitive to pH, because protonation will convert it to the transient species, carbonic acid, and rapidly to dissolved CO2. A more promising approach might be to take advantage of the fact that the interconversion 13CO2 ⇔ H213CO3 ⇔ H+ + H13CO3− is a rapid, pH-dependent reaction. Although the observed H13CO3−/13CO2 ratio will depend on pulsing conditions, a simple substitution of the measured H13CO3−/13CO2 ratio (7.3) in these experiments into the Hendersen–Hasselbalch relationship reports that the pH in these hearts was 7.0 ± 0.2, similar to results using other methods (27). The ability to simultaneously detect both dissolved 13CO2 and H13CO3− raises the interesting possibility that imaging intracellular cardiac pH is feasible.

These experiments highlight the general advantages of the large inherent chemical shift dispersion of 13C nuclei in detecting cardiac metabolism using hyperpolarized [1-13C1]pyruvate. First, the appearance of [1-13C1]pyruvate demonstrates tissue perfusion. Second, equilibration of 13C label into the alanine and lactate pools provides information about redox reactions and transamination reactions that are largely confined to the cytosol even in the absence of net synthesis of either lactate or alanine. Third, pyruvate is oxidized irreversibly to acetyl-CoA, a mitochondrial reaction, with stoichiometric release of 13CO2 that is rapidly converted to H13CO3−. The rate of appearance of either product provides an index of flux through PDH. Finally, the 13CO2 to H13CO3− ratio is pH sensitive. The inherent ability to separate perfusion from metabolic events is an important advantage of [1-13C1]pyruvate compared with conventional clinical radiotracers.

Methods

[1-13C1]Pyruvate, [U-13C3]pyruvate, and [2,4,6,8-13C1]octanoate (all 99% enriched) were obtained from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. The trityl radical, Tris{8-carboxyl-2,2,6,6-tetra[2-(1-hydroxyethyl)]-benzo(1,2-d:4,5-d)bis(1,3)dithiole-4-yl}methyl sodium salt, was obtained from Oxford Molecular Biotools. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma. Sprague–Dawley rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories and given free access to standard rat chow and water.

Heart Perfusions.

Protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Hearts from adult male rats were rapidly excised under general anesthesia and perfused at 37°C and 100-cm H2O by using standard Langendorff methods. Heart rate was monitored through an open-ended catheter in the left ventricle. After the aorta was cannulated, the heart was supplied initially with 200–500 ml of recirculating medium and placed in an 18-mm NMR tube. The perfusing medium was a modified Krebs–Henseleit buffer containing the following: 118 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, and unenriched oxidizable substrate(s) described below. The medium was filtered and bubbled continuously with a 95:5 mixture of O2/CO2. The water-jacketed glass perfusion apparatus was then placed into the bore of a 14.1-T magnet. During a preparation and stabilization time of ≈20 min, the NMR probe was tuned and the field homogeneity was optimized by using the free induction decay from the 23Na signal. A line width of 15 Hz was typically obtained. Completion of this set-up process was timed to coincide with dissolution of the hyperpolarized substrate. The available substrates in the perfusing medium were varied as follows (n = 4–6 hearts in each group): group 1, 2 mM pyruvate followed by 2 mM hyperpolarized pyruvate; group 2, 2 mM octanoate followed by 2 mM octanoate and hyperpolarized [1-13C1]pyruvate; group 3, 2 mM propionate and 2 mM octanoate followed by 2 mM propionate, 2 mM octanoate, and 2 mM hyperpolarized [1-13C1]pyruvate.

Hyperpolarization and Delivery of 13C-Enriched Substrates.

The polarization process, similar to the procedure described by Golman et al. (28), was started ≈90 min before each heart was isolated, cannulated, and perfused. This time period is sufficient to achieve 95% of the maximum polarization for the pyruvate.‡‡ Aliquots (≈10 μl) of a 2.5 M substrate solution prepared in deionized H2O were mixed with an equal volume of 15.5 mM trityl radical in glycerol. The solutions were placed in the 3.35-T Oxford Hypersense (Oxford Instruments Molecular Biotools) dynamic nuclear polarization system and polarized before dissolution and ejection. The electron irradiation frequency was set to 94.118 GHz. Approximately 100 min of microwave irradiation at 1.4 K typically yielded ≈15% polarization. The polarized sample was rapidly thawed by dissolution in 4 ml of heated water containing 0.85 mM Na2EDTA. Three milliliters of this solution was further diluted into 20 ml of perfusate to stabilize the pH and oxygenation. Total time of dissolution, ejection of the sample, and further dilution was ≈10 s. The solution was injected by catheter into the perfusion column directly above the heart over a period of ≈60 s. The temperature of all solutions entering the heart was 37°C, and the pH was 7.3–7.4. The NMR console was triggered to start acquisition at the beginning of the dissolution process.

13C NMR Spectroscopy of the Isolated Heart.

13C NMR spectra were acquired at 14.1 T (Varian INOVA) in an 18-mm broadband probe (Doty Scientific) using 66° pulses. A small glass bulb containing dioxane was secured near the right atrium. The first free induction decays (FIDs) were acquired a few seconds before injection of the hyperpolarized solution. Serial, single FIDs were acquired with proton decoupling over a ±16,000-Hz bandwidth into 16,384 points. Acquisition time was ≈1 s, giving a time to repeat of 1 s for each scan. Typically 150–180 separate FIDs were collected. These data were zero-filled before Fourier transformation. The relative peak areas were measured by integration using the VNMR software. The plots of signal intensity for the respective substrates as a function of time are the mean values obtained from four heart perfusions using each perfusion condition. Chemical shifts were assigned relative to the dioxane external standard at 67.4 ppm. The chemical shift of dissolved 13CO2 was taken from previous reports (29, 30). Magnetization transfer was performed by saturating either the 13CO2 or H13CO3− resonance (31).

Oxygen Consumption and Metabolic Fluxes.

In separate experiments outside the NMR spectrometer, another group of hearts was studied in the same perfusion apparatus for measurement of oxygen consumption and fluxes intersecting in the TCA cycle. Oxygen consumption was determined by using coronary flow measurements and the difference in pO2 between the arterial perfusate and the coronary effluent (Instrumentation Laboratory) for all three metabolic conditions studied with hyperpolarized pyruvate. In addition, two groups of hearts were studied in the presence of 2 mM [U-13C3]pyruvate or 2 mM [2,4,6,8-13C4]octanoate plus [U-13C3]pyruvate plus unenriched propionate. These hearts were perfused for 30 min, freeze-clamped, and stored at −85°C. Tissue was extracted with perchloric acid, neutralized, freeze-dried, and resuspended in 0.6 ml of 2H2O for proton-decoupled 13C NMR spectroscopy (17, 18). Flux through PDH and citric acid cycle flux was determined by using 13C NMR isotopomer analysis and O2 consumption. The relative rates of oxidation of each energy source, pyruvate, octanoate, or endogenous stores, were measured from the proton-decoupled 13C NMR spectrum of glutamate (17, 18). After correcting for generation of NADH outside the citric acid cycle, the relative rate of flux through each pathway was converted to absolute flux with the measured oxygen consumption (32).

Acknowledgments

We thank Angela Milde for outstanding technical support and William Mander for expert advice regarding the operation of HyperSense. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants RR02584 and HL34557.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Zierhut M. L., Chen A. P., Bok R., Albers M., Zhang V., Pels P., Tropp J., Park I., Vigneron D. B., Kurhanewicz J., et al., Joint Annual Meeting of International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine–European Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine and Biology, May 19–25, 2007, Berlin, Germany.

Schroeder M. A., Cochlin L. E., Radda G. K., Clarke K., Tyler D. J., Joint Annual Meeting of International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine–European Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine and Biology, May 19–25, 2007, Berlin, Germany.

References

- 1.Shulman RG, Rothman DL, editors. Metabolomics by in Vivo NMR. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Fridlund B, Gram A, Hansson G, Hansson L, Lerche MH, Servin R, Thaning M, Golman K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golman K, Petersson JS. Acad Radiol. 2006;13:932–942. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeffrey FMH, Malloy CR. Biochem J. 1992;287:117–123. doi: 10.1042/bj2870117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taegtmeyer H. Basic Res Cardiol. 1984;79:322–336. doi: 10.1007/BF01908033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaitman BR, Skettino SL, Parker JO, Hanley P, Meluzin J, Kuch J, Pepine CJ, Wang W, Nelson JJ, Hebert DA, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1375–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Opie LH. Nature. 1970;227:1055–1056. doi: 10.1038/2271055a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sodi-Pallares D, Testelli MR, Fishleder BI, Bisteni A, Medrano GA, Friedland C, De Micheli A. Am J Cardiol. 1962;9:166–181. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(62)90035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vik-Mo H, Mjos OD. Am J Cardiol. 1981;48:361–365. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(81)90621-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee L, Campbell R, Scheuermann-Freestone M, Taylor R, Gunaruwan P, Williams L, Ashrafian H, Horowitz J, Fraser AG, Clarke K, et al. Circulation. 2005;112:3280–3288. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.551457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neubauer S. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1140–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra063052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Diaz R, Zhu J, Pais P, Xavier D, Paolasso E, Ahmed R, Xie C, Kazmi K, et al. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;293:437–446. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Latipaa PM, Peuhkurinen KJ, Hiltunen JK, Hassinen IE. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1985;17:1161–1171. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(85)80112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dennis SC, Padma A, DeBuysere MS, Olson MS. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:1252–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olson MS, Dennis SC, DeBuysere MS, Padma A. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:7369–7375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Day SE, Gallagher FA, Kettunen MI, Brindle KM. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med. Berlin, Germany: Int Soc for Magn Reson in Med; 2007. p. 368. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malloy CR, Sherry AD, Jeffrey FMH. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:6964–6971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malloy CR, Sherry AD, Jeffrey FMH. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:H987–H995. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.3.H987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindskog S, Henderson L, Kannan K, Liljas A, Nyman P, Strandberg B. In: The Enzymes. Boyer PD, editor. Vol 5. New York: Academic Press; 1971. pp. 587–665. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bailey IA, Gadian DG, Matthews PM, Radda GK, Seeley PJ. FEBS Lett. 1981;123:315–318. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80317-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malloy CR, Sherry AD, Jeffrey FMH. FEBS Lett. 1987;212:58–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81556-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherry AD, Nunnally RL, Peshock RM. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:9272–9279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Fridlund B, Gram A, Hansson G, Hansson L, Lerche MH, Servin R, Thaning M, Golman K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Golman K, in't Zandt R, Thaning M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11270–11275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601319103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taegtmeyer H. Basic Res Cardiol. 1983;78:435–450. doi: 10.1007/BF02070167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gout E, Bligny R, Douce R. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13903–13909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garlick PB, Radda GK, Seeley PJ. J Biochem. 1979;184:547–554. doi: 10.1042/bj1840547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golman K, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Petersson JS, Mansson S, Leunbach I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10435–10439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733836100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liger-Belair G, Prost E, Parmentier M, Jeandet P, Nuzillard JM. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:7560–7563. doi: 10.1021/jf034693p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shporer M, Forster RE, Civan MM. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:C231–C234. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1984.246.3.C231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malloy CR, Sherry AD, Nunnally RL. J Magn Reson. 1985;64:243–254. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malloy CR, Jones JG, Jeffrey FMH, Jessen ME, Sherry AD. MAGMA. 1996;4:35–46. doi: 10.1007/BF01759778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]