Abstract

Assembly of the higher-order structure of mitotic chromosomes is a prerequisite for proper chromosome condensation, segregation and integrity. Understanding the details of this process has been limited because very few proteins involved in the assembly of chromosome structure have been discovered. Using a human autoimmune scleroderma serum that identifies a chromosomal protein in human cells and Drosophila embryos, we cloned the corresponding Drosophila gene that encodes the homologue of vertebrate titin based on protein size, sequence similarity, developmental expression and subcellular localization. Titin is a giant sarcomeric protein responsible for the elasticity of striated muscle that may also function as a molecular scaffold for myofibrillar assembly. Molecular analysis and immunostaining with antibodies to multiple titin epitopes indicates that the chromosomal and muscle forms of titin may vary in their NH2 termini. The identification of titin as a chromosomal component provides a molecular basis for chromosome structure and elasticity.

Autoimmune diseases are characterized by the presence of multiple autoantibodies that react with components of nuclear, cytoplasmic, or surface origin (for review see Nakamura and Tan, 1992; Fritzler, 1997). In clinical medicine, autoantibodies have been used to establish diagnosis, estimate prognosis, follow the progression of a specific autoimmune disease, and, finally, increase our knowledge of the pathophysiology of autoimmunity. In cell biology, autoantibodies have been extremely useful as probes for the identification of novel proteins and isolation of their corresponding genes. Human autoimmune sera have been particularly useful in the study of the eukaryotic nucleus where they have identified a wide range of nuclear antigens, including both single- and double-stranded DNA, RNA, histones, small nuclear RNA-binding proteins, transcription factors, nuclear lamins, heterochromatin-associated proteins, topoisomerase I and II, and centromere proteins (Tan, 1989, 1991; Earnshaw and Rattner, 1991; Fritzler, 1997).

Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis) is a multisystem connective tissue autoimmune disease of unknown etiology in which vascular lesions and tissue fibrosis are prominent features. Even though autoantibody production may be an epiphenomenon of autoimmune diseases, autoantibody targets in scleroderma are very specific (White, 1996). The autoantigens to which scleroderma sera typically react include topoisomerase I, centromere proteins, RNA polymerases, fibrillarin, and several other nucleolar antigens (LeRoy, 1996). However, autoantibodies of rare occurrence have been reported that react with antigens localized to metaphase chromosomes and to the centrosome (Jeppesen and Nicol, 1986; Nakamura and Tan, 1992).

Here, we report on the isolation of a Drosophila gene using a scleroderma serum that recognized an epitope on condensed mitotic chromosomes from both human cultured cells and early Drosophila embryos. Using this serum to screen a Drosophila expression library, we isolated the gene that encodes the chromosomal protein that proved to be the Drosophila homologue of vertebrate titin (D-Titin). Titin is a sarcomeric protein responsible for the elasticity of striated muscle and may also function as a molecular scaffold for the assembly of myofibrils (for review see Keller, 1995; Labeit and Kolmerer, 1995; Trinick, 1996; Labeit et al., 1997; Maruyama, 1997; Squire, 1997). We show that D-Titin is expressed early and continuously in striated muscle and that antibodies directed against two different, nonoverlapping domains of Drosophila TITIN label the Z-disks of Drosophila sarcomeres. The D-TITIN antibodies also stain condensed human and Drosophila mitotic chromosomes, consistent with the staining observed with the original scleroderma serum. Immunofluorescence with monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against multiple epitopes of vertebrate titin further supports its localization to condensed mitotic human chromosomes, suggesting a role for titin not only in myofibrillar assembly and muscle elasticity, but potentially in the architecture of mitotic chromosomes.

As the name implies, titin is a giant protein. Individual filamentous titin molecules, which range in molecular mass from 2,993 to 3,700 kD, span a half-sarcomere from the Z-disk to the M-line, a distance of ∼1.2 μm in sarcomeres of relaxed skeletal muscle (Labeit and Kolmerer, 1995; Kolmerer et al., 1996; Sorimachi et al., 1997). Nearly 90% of titin's mass is comprised of Ig-like and fibronectin type III (FN3)1-like repeats which are distributed throughout most of the protein (Labeit et al., 1990; Maruyama et al., 1993; Labeit and Kolmerer, 1995). The I-band region of vertebrate titin also contains a domain rich in proline (P), glutamic acid (E), valine (V), and lysine (K) that varies from 163 to 2,200 residues, the so-called PEVK domain. The PEVK domain and the tandemly arranged Ig domains of the I-band region of titin confer elasticity to the titin filament (Linke et al., 1996; Trombitas et al., 1998). Titin has phosphorylation sites (Sebastyén et al., 1995), recognition sites for muscle-specific calpain proteases (Sorimachi et al., 1995; Kinbara et al., 1997) and a serine/threonine kinase domain near the COOH terminus (Labeit et al., 1992; Takano-Ohmuro et al., 1992).

Titin may function as the scaffold upon which the sarcomeres are assembled into myofibrils (Keller, 1995; Trinick, 1996). Titin mRNA is expressed in myoblasts before fusion (Colley et al., 1990), and titin mRNA and protein are among the earliest molecules to localize within the developing sarcomere (Fulton and Alftine, 1997; van der Ven and Fürst, 1997). Titin binds to different proteins in each region of the sarcomere. In the Z-disk, the NH2 terminus of titin binds to the COOH-terminal region of α-actinin, an actin-binding protein that cross-links titin to actin filaments (Ohtsuka et al., 1997a ,b; Sorimachi et al., 1997; Turnacioglu et al., 1997). In cardiac muscle, the NH2 terminus of titin binds to actin in the Z-disk near the Z/I-band junction (Linke et al., 1997; Trombitas and Granzier, 1997; Trombitas et al., 1997). The A-band region of titin provides a molecular template for the regular assemblies of thick filament proteins such as myosin, MyBP-C, and MyBP-H (C- and H-protein; Itoh et al., 1988; Fürst et al., 1989; Soteriou et al., 1993; Houmeida et al., 1995; Freiburg and Gautel, 1996; Trombitas et al., 1997). Titin may also bind to myosin II (Eilertsen et al., 1994). In the M-line, titin binds to M-protein and phosphorylated myomesin, two myosin-binding proteins that cross-link titin to myosin filaments (Eppenberger et al., 1981; Obermann et al., 1996, 1997). Functional evidence that titin acts as a myofibrillar scaffold derives from experiments where an NH2-terminal fragment of titin was fused to green fluorescent protein. This fusion protein, which localizes to the Z-disk, causes myofibrillar disassembly when overexpressed (Turnacioglu et al., 1997). The identification of titin, a gigantic protein important in both the structure and elasticity of muscle, as a chromosomal component has significant ramifications for understanding chromosome condensation and chromosome integrity during mitosis.

Materials and Methods

Staining of HEp-2 cells

Fixed HEp-2 cells (Kallestad, Chaska, MN) were blocked for 30 min at RT in PBS plus 0.1% Triton X-100 and 3% BSA (PBSTB), incubated for 1 h at room temperature in primary antibody, washed 3× for 5 min in PBSTB, incubated for 1 h with fluorescently labeled secondary antibody and washed 3× for 5 min in PBSTB. Cells were then incubated for 5 min at room temperature in 1.25 μg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) and washed twice in PBS. RNaseA (100 μg/ml; Sigma Chemical Co.) was included during antibody incubations. Images were collected on a confocal microscope (Noran Instrument, Middleton, WI). Forty scleroderma sera, provided by D. Isenberg (King's College, London, UK) were tested at a range of dilutions from 1:25 to 1:5,000 in the initial screen. The chosen scleroderma serum was used at a 1:200 dilution for subsequent experiments. Vertebrate titin polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies were used at dilutions of 1:25 and 1:100, respectively (provided by S. Labeit, EMBL, Heidelberg, Germany and J. Trinick, Bristol University, Bristol, UK). All fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:200 (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA). Several fixative procedures (acetone/MeOH, acetone, formaldehyde based), with and without prior Triton X-100 permeabilization, were tested and produced the same staining patterns.

Antibody Production

The α-LG polyclonal antiserum was made by immunizing rabbits with 450 μg of β-gal:D-TITIN fusion protein administered subcutaneously. The α-LG antiserum was affinity-purified as described (Earnshaw and Rattner, 1991) and used at a dilution of 1:4. To produce the α-KZ antiserum, an XhoI/EcoRI fragment of the most 5′ cDNA (see Fig. 2) encoding 636 residues was ligated in-frame to the pTrcHisA expression vector (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) and transformed into BL21 (DE3) cells. Protein was purified from inclusion bodies 3 h after induction with 0.1 mM IPTG (Rio et al., 1986). Rat polyclonal antibodies were raised (Covance Inc., Denver, PA) against 1 mg of renatured inclusion body protein. The α-KZ antiserum was used at 1:5,000 dilution for embryo immunostaining in Fig. 3 and at 1:500 for all other experiments. Equivalent dilutions of preimmune α-LG and α-KZ sera were used as controls, as well as secondary antibodies alone.

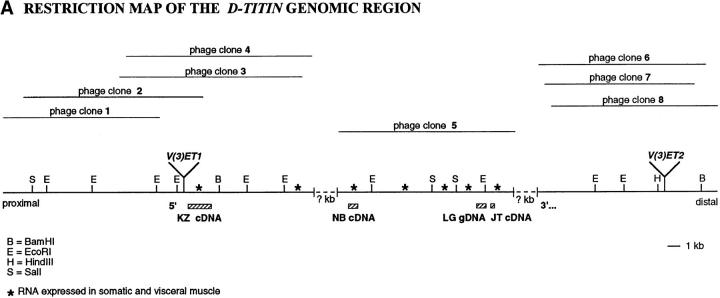

Figure 2.

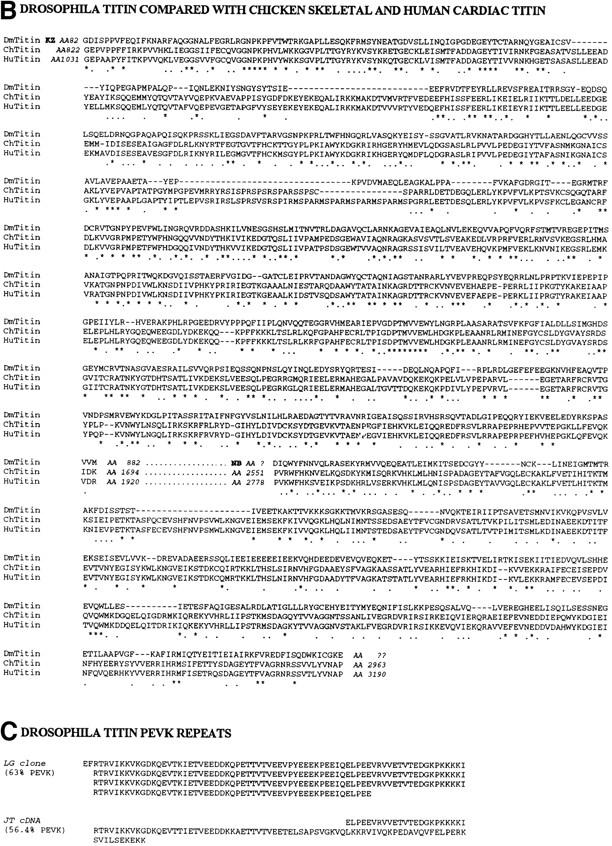

The chromosome-associated protein is Drosophila TITIN. (A) Restriction map of the genomic region of the D-Titin gene. The genomic phage clones were either isolated directly (phage clone 5) using the LG genomic DNA expression clone as a probe, or were isolated using DNA flanking two nearby P-element insertions. Phage clones 1–4 and 6–8 were isolated with DNA flanking the v(3)ET1 and v(3)ET2 insertions, respectively. Three different D-Titin cDNA fragments were isolated from multiple independent screens of seven available cDNA libraries. The 5′ KZ cDNA was isolated from a 9–12 h embryonic cDNA library (Zinn et al., 1988). We infer that the KZ cDNA encodes an NH2 terminus based on the presence of a putative initiator methionine codon followed by an ORF encoding 882 AA. The ORF is flanked at the 5′ end by 389 nt of noncoding sequence. The NB cDNA was isolated from a 12–24 h embryonic cDNA library (Brown and Kafatos, 1988). Within the unprocessed NB cDNA, there is a 1-kb ORF flanked at its 5′ end by a 3′ splice acceptor site and at its 3′ end by a 5′ splice donor site (Mount, 1982; Mount et al., 1992). Several small (⩽312 nt) cDNAs were isolated from a 0–24 h embryonic cDNA library (Tamkun et al., 1991). The largest cDNA isolated from the Tamkum library is indicated as JT cDNA. Multiple unsuccessful attempts were made to connect the genomic DNA from phage clone 5 to the surrounding phage containing DNA from this region. Nonetheless, all of the genomic phage clones (1–7) and all of the cDNA clones colocalize to the same site on polytene chromosomes from wild-type larvae, cytological region 62C1-2. Furthermore, genomic phage clones 1–5 and all the D-Titin cDNAs map to an interval for which only a single complementation group has been identified, based on genomic Southern mapping and in situ hybridization to polytene chromosomes from larvae carrying local deficiencies. An asterisk indicates genomic fragments that revealed somatic and visceral muscle RNA accumulation in whole-mount embryos by in situ hybridization. (B) Protein sequence alignment among the corresponding ORFs from two D-Titin cDNAs (KZ and NB), chicken skeletal titin and human cardiac titin. Identities among all three proteins are indicated by an asterisk and conserved residues shared among all three proteins are indicated by period. (C) Sequence of the PEVK-rich ORF originally isolated with the scleroderma autoimmune serum (LG clone) and the sequence from the largest cDNA isolated from the Tamkun library (JT cDNA). 63% of the residues in the LG clone are either proline (P), glutamic acid (E), valine (V), or lysine (K). 56.4% of the residues encoded by the JT cDNA are either P, E, V, or K. The PEVK-rich domain of vertebrate titin, which provides muscle elasticity, is ∼70% P, E, V, K. These sequence data are available from GenBank/EMBL/DDJB under accession numbers AF045775, AF045776, AF045777, and AF045778.

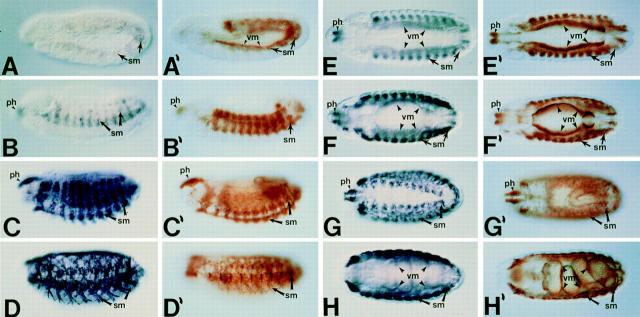

Figure 3.

D-Titin is expressed in all the somatic and visceral musculature during embryogenesis. Pairs of embryos at the same developmental stage and view are shown with in situ hybridization to detect RNA on the left (dark blue) and immunostaining to detect protein on the right (brown). All embryos are oriented with anterior to the left. For embryos shown in lateral view, dorsal is up. Stages and structures are as described (Campos-Ortega and Hartenstein, 1985). (A/A′) Embryonic stages 10/11, lateral view. D-Titin transcript and protein were first detectable in fully germ band extended embryos in the somatic and visceral mesoderm. (B/B′) Embryonic stage 13, lateral view. In germ band shortened embryos, D-Titin RNA and protein could be detected in the pharyngeal, somatic and visceral musculature. (C/C′) Embryonic stage 15, lateral view. High level accumulation of both transcript and protein were observed in both somatic and pharyngeal muscles. (D/D′) Embryonic stage 17, lateral view. RNA and protein can be detected in the fully developed larval muscle pattern. (E/E′) Embryonic stage 13, dorsal/ventral view. RNA and protein accumulation is evident in the pharynx and both visceral and somatic muscles. (F/F′) Embryonic stage 14, dorsal/ventral view. D-Titin expression was observed throughout the visceral and somatic musculature, both of which are striated in Drosophila. (G/G′) Embryonic stage 15, dorsal view. At this stage, individual muscle fibers are beginning to form. (H/H′) Embryonic stage 16, dorsal/ventral view. Expression of D-Titin persists in the pharyngeal, somatic, and visceral muscles. ph, pharynx/pharyngeal; sm, somatic mesoderm/musculature; vm, visceral mesoderm/musculature.

Drosophila Immunostaining and In Situ Hybridization

Embryo fixation and antibody staining were performed as described (Reuter et al., 1990). In situ hybridizations to whole-mount embryos were carried out as described (Tautz and Pfeifle, 1989), except formaldehyde was used in place of paraformaldehyde and levamisole was omitted from the staining reaction. Images were collected on an Axiophot microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY). Adult thoracic muscle and larval gut muscle were prepared for immunostaining and stained as described (Saide et al., 1989; Lakey et al., 1993). Texas red–phalloidin was used at a concentration of 0.1 U/ml (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR). Images were collected on a Noran confocal microscope.

Immunoblot Preparation

Samples were homogenized in 2× Laemmli sample buffer and electrophoresed on 2.5–7.5% SDS-PAGE gradient gels (Laemmli, 1970); the stacking gel was 0.6% agarose in 0.1% SDS, 0.125 M Tris-glycine, pH 6.8. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose filters (Schleicher & Schuell, Inc., Keene, NH) for 2 h at 900 mA as described (Wang et al., 1989). Samples from each extract were run on the same gel, transferred to nitrocellulose and cut into strips for antibody incubations. Immunoblots were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with blocking solution (5% nonfat dried milk in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS [PBT]), incubated with primary antibody for 2.5 h at room temperature (1:200 dilution of α-LG and 1:500 dilution of α-KZ), and washed 3× for 10 min in blocking solution. Filters were incubated in either a 1:4,000 dilution of HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (α-LG and LG preimmune; Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology Inc., Piscataway, NJ) or a 1:300 dilution of HRP-conjugated anti-rat F(ab)2 IgG (α-KZ and KZ preimmune; Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology Inc.), washed 3× for 10 min in blocking solution and 2× for 5 min in PBS. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by chemiluminescence (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL).

Results

Human Scleroderma Serum Stains Mitotic Chromosomes

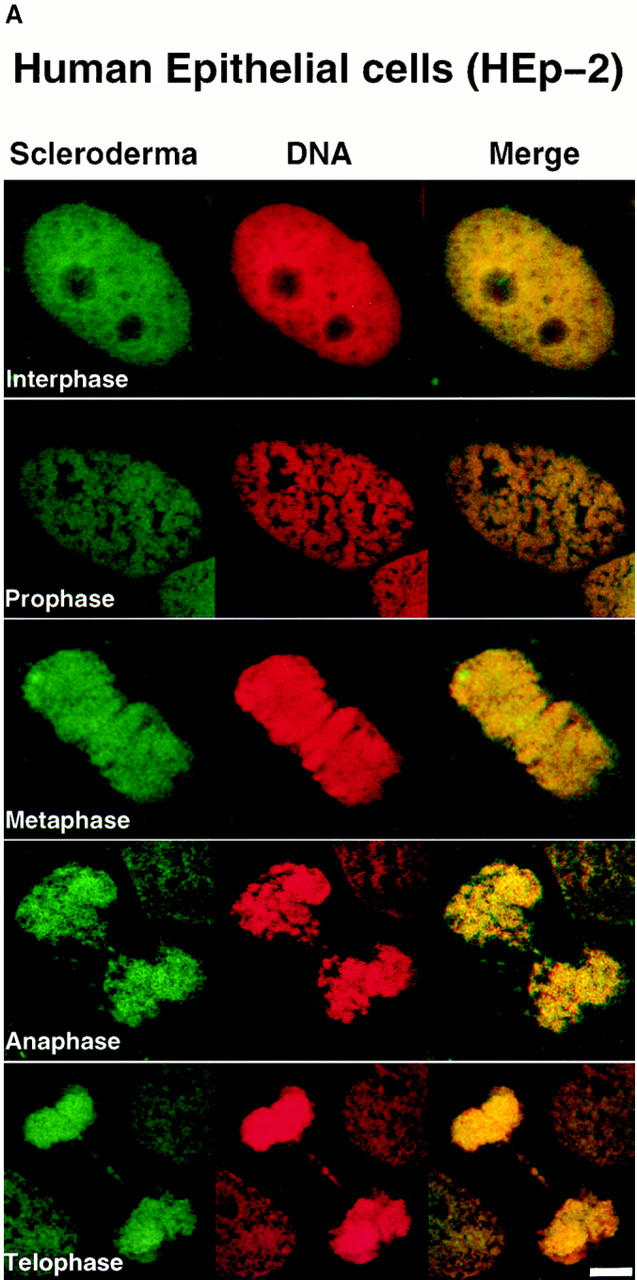

To identify novel nuclear components and to isolate and characterize the corresponding genes in Drosophila, we screened for human autoimmune sera that recognized nuclear components with cell cycle–dependent distribution in both human cells and early Drosophila embryos. Sera from 40 patients diagnosed with the autoimmune disease scleroderma were studied and only one serum was identified that gave chromosomal staining on both human epithelial HEp-2 cells and Drosophila 0–2 h embryos (Fig. 1 A). During interphase, when chromosomes are decondensed, low level staining was visible throughout the nucleus, with the exception of the nucleoli. During prophase, staining with this serum colocalized with the condensing chromosomes. From metaphase through telophase, chromosomes were stained uniformly.

Figure 1.

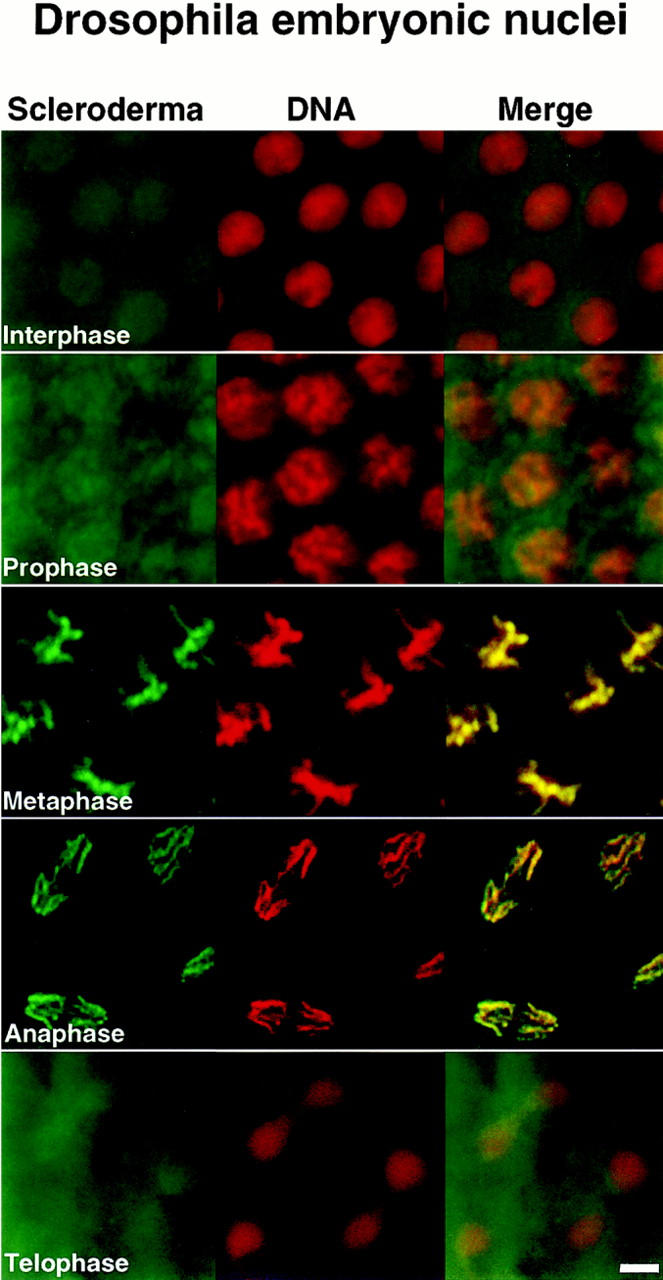

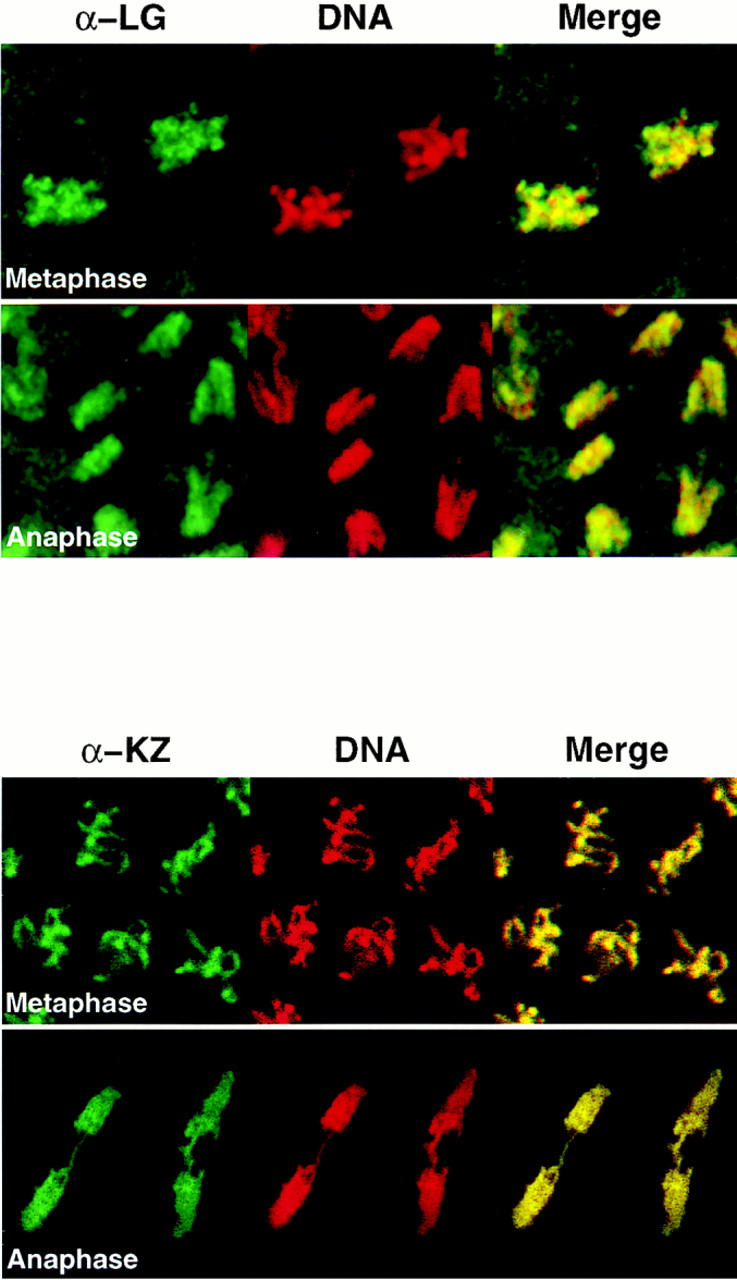

Human scleroderma serum identifies a chromosome-associated protein in human epithelial cells and Drosophila early embryos. (A) Chromosomal staining pattern recognized by the human autoimmune serum on HEp-2 cells (left panels) and Drosophila early embryos (right panels). HEp-2 cells and Drosophila 0–2 h embryos were double-stained with the scleroderma serum (green) and propidium iodide to detect DNA (red). The merged image is on the right (yellow in region of overlap). (B) Chromosomal staining pattern on HEp-2 cells (left panels) and Drosophila 0–2 h embryos (right panels) recognized by an affinity-purified polyclonal antibody (α-LG) raised against the PEVK-rich repeats of the Drosophila protein identified by expression cloning with the human autoimmune scleroderma serum. Top and bottom panels show metaphase and anaphase nuclei, respectively, stained with α-LG (green) and propidium iodide (red). The merged image is on the right (yellow). (C) Immunofluorescence of HEp-2 cells (left panels) and Drosophila 0–2 embryos (right panels) using a polyclonal serum (α-KZ) raised against an NH2-terminal peptide encoded by the KZ cDNA (green) and a DNA dye, propidium iodide (red). The merged image is on the right (yellow). Bar, 5 μm.

Cloning of Drosophila Titin

To isolate the corresponding gene in Drosophila, the human autoimmune scleroderma serum was used to screen a Drosophila genomic expression library (Goldstein et al., 1986). Out of 5 × 106 plaque-forming units screened, five independent, overlapping genomic clones were isolated, each encoding several copies of a 71–amino acid repeat rich in proline, valine, glutamic acid, and lysine residues (Fig. 2 C). The largest clone (designated LG) was expressed in Escherichia coli, and the corresponding fusion protein was purified and used to immunize rabbits. α-LG affinity-purified antibodies gave the same chromosomal staining pattern on both human HEp-2 cells and Drosophila 0–2 h embryos in all stages of the cell cycle as was initially observed with the human serum (Fig. 1 B). We subsequently isolated additional exons from this Drosophila gene (see below) and used a different domain of the protein to raise a second polyclonal antiserum in rat (designated α-KZ). The α-KZ antiserum reproduced the staining pattern observed with the human autoimmune serum and the α-LG antibody, that is, nuclear staining during interphase (not shown) and staining of condensed chromosomes during mitosis (Fig. 1 C).

Attempts to clone the entire genomic region corresponding to the chromosome-associated protein gene were unsuccessful most likely because of its repetitive structure. The isolation of cDNAs was similarly difficult due in part to the repetitive structure of the gene but also because of the predicted large size of the corresponding mRNA (see below). Nonetheless, cDNAs mapping to several discrete regions of the gene, encoding a total of 1,608 amino acids, were isolated and characterized (Fig. 2). The partial cDNAs, designated KZ, NB, and JT, were named according to the libraries in which they were found. See Fig. 2 legend for the details of cloning. All of the cDNA clones and genomic phage clones 1–5 map to cytological position 62C1-2 in a region known to contain only a single gene.

Notably, every open reading frame (ORF) identified from the chromosome-associated protein gene shows significant similarity to vertebrate titins (Fig. 2 B). Using the conceptual translation of the KZ cDNA to do a BLAST search, the two proteins with greatest similarity are chicken skeletal titin (P = 2.7e−99) and human cardiac titin (P = 1.2e−80). The ORF within the unprocessed NB cDNA also shows significant similarity to vertebrate titins. An alignment between the ORFs derived from the KZ and NB cDNAs and the chicken skeletal and human cardiac titins is shown in Fig. 2 B. In the region of overlap, the ORF encoded by the KZ cDNA shows 28.6% identity/ 58.3% similarity to chicken skeletal titin, and 27.4% identity/56.8% similarity to human cardiac titin. The ORF encoded by the NB cDNA shows 18.4% identity/48.9% similarity to chicken skeletal titin, and 17.2% identity/47.7% similarity to human cardiac titin in the region of overlap. The sequence conservation among the ORFs from the LG and JT clones and vertebrate titins is not as great; however, in these clones, the frequency of P, E, V, and K residues (63% for LG, 56.4% for JT) strongly suggests that these ORFs correspond to the elastic PEVK domain of vertebrate titin, which is 70% P, E, V, K (Fig. 2 C). Thus, starting with a human autoimmune scleroderma serum, we have cloned a Drosophila gene encoding a nuclear protein that localizes to chromosomes and is homologous to vertebrate titins.

D-Titin in Striated Muscles and Their Precursors

To determine whether the gene that encodes the nuclear, chromosome-associated form of titin also encodes the muscle form of titin, we examined both transcript and protein accumulation in embryos, and determined the subcellular localization of the protein in muscle. Analysis of RNA expression by in situ hybridization to whole-mount Drosophila embryos revealed RNA accumulation as early as the germ band extended stage in both somatic and visceral muscle precursors (Fig. 3 A). Protein was initially detected during late stage 11 in the precursors of both somatic and visceral muscles (Fig. 3 A′), before myoblast fusion (stage 13; Hartenstein, 1993). This early accumulation of protein in Drosophila muscle precursors parallels vertebrate titin accumulation in early myoblasts (Colley et al., 1990). Expression of both RNA and protein in all visceral and somatic muscles persisted throughout embryogenesis (Fig. 3, B–H′). These muscles include the somatic or body wall muscles, the pharyngeal muscles, and the visceral musculature which surrounds the digestive system. We did not detect RNA or protein in embryonic cardiac muscle or cardiac muscle precursors.

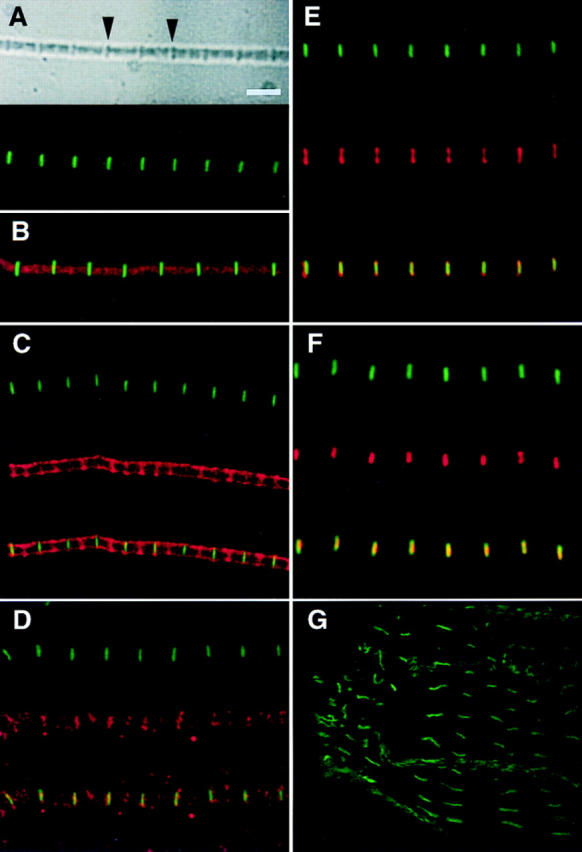

To determine if the protein localizes to specific regions in the sarcomere, we immunostained adult thoracic muscle with antibodies directed against two different domains of the protein (α-KZ and α-LG; Fig. 2) and with the original human autoimmune scleroderma serum. The α-KZ antiserum stained the Z-disks of each sarcomere, which can be identified as the phase-dark bands on myofibrils (Fig. 4 A). A double-stained image of a myofibril stained with α-KZ and Texas red–phalloidin, which stains the filamentous actin of the I-band, supports this localization (Fig. 4 B). Double staining with the α-KZ antiserum and either the human autoimmune scleroderma serum (Fig. 4 C) or the α-LG affinity-purified antibodies (Fig. 4 D) also revealed Z-disk staining. Both the α-LG antibodies and the scleroderma serum also stained the M-line suggesting potential cross-reactivity to other antigens. The scleroderma serum, but not the α-LG antibodies, also stained along the length of the myofibril (Fig. 4 C), suggesting the presence of additional, nontitin antibodies in the serum. Two antibodies against vertebrate titin recognized epitopes on Drosophila myofibrils: serum from a patient with myasthenia gravis, which recognizes the major immunogenic region (MIR) epitope in the I-band near the I/A-band junction (Fig. 4 E; Gautel et al., 1993), and anti-Zr5/Zr6, a polyclonal antiserum that was raised to the expressed α-actinin binding Z-repeat motifs Zr5/Zr6 (Fig. 4 F; Sorimachi et al., 1997). The nearly complete overlap of the signals with α-KZ and the MIR serum suggests that the resolution of confocal microscopy was insufficient to allow visual separation of Z-disk staining from I/A-band staining in nonstretched Drosophila myofibrils. We also found that the α-KZ and α-LG antibodies stained the Z-disks of visceral muscles from third instar larvae (Fig. 4 G). Drosophila visceral muscle, unlike vertebrate smooth muscle, is striated.

Figure 4.

Antibodies to Drosophila TITIN stain specific regions of the sarcomeres from Drosophila adult thoracic myofibrils and larval gut muscle. (A) The top panel shows a phase image of a myofibril from adult thoracic muscle, which has been immunostained with the α-KZ antiserum (lower panel). Arrows in upper panel indicate Z-disks. (B) Adult thoracic myofibril double-stained with α-KZ (green) and Texas red–phalloidin. (C) Double-staining of an adult thoracic myofibril with α-KZ (green) and the human autoimmune scleroderma serum (red); the lower panel shows the merged image (yellow in region of overlap). (D) Double-staining of an adult thoracic myofibril with α-KZ (green) and affinity-purified α-LG (red); the lower panel shows the merged image. (E) Double-staining of an adult thoracic myofibril with α-KZ (green) and the human serum MIR (red) that in vertebrate sarcomeres recognizes an epitope in the I-band near the I/A-band junction; the lower panel shows the merged image. (F) Double-staining of an adult thoracic myofibril with α-KZ (green) and with the anti-Zr5/Zr6 polyclonal serum (red) that was raised against the rabbit titin Z-repeats that bind to α-actinin; the lower panel shows the merged image. (G) Third instar larval gut muscle stained α-KZ antiserum (green). The fluorescent staining overlaps the phase-dark bands (not shown) that correspond to the Z-disks of the gut muscles. No staining was observed with the α-KZ preimmune serum nor with any of the secondary antibodies. However, a regular pattern of accumulation on myofibrils was detected with the LG preimmune serum. Bar, 3 μm.

We have named the gene isolated with the human autoimmune scleroderma serum D-Titin for Drosophila Titin. This name is based on the high level of similarity to vertebrate titins, the expression pattern of this gene during embryogenesis (Fig. 3), the localization of two different domains of the protein to the Z-disks in sarcomeres by immunofluorescence (Fig. 4) and the size of the protein on immunoblots (Fig. 5; see below).

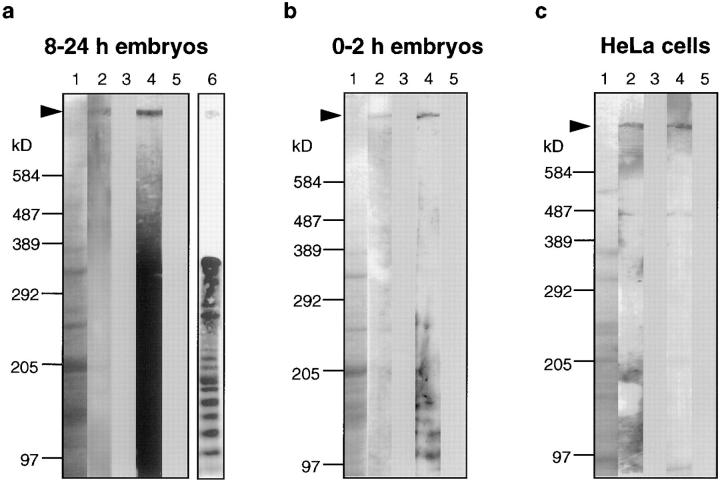

Figure 5.

D-TITIN migrates in the megadalton size range and is detected in nonmuscle cells. Total protein extracts from (a) Drosophila 8–24 h embryos (after myogenesis), (b) Drosophila 0–2 h embryos (several hours before myogenesis), and (c) HeLa cells were separated on SDS-PAGE 2.5–7.5% gradient gels. Lanes 1, Coomassie blue-stained SDS-gels. Lanes 2–5, immunoblots incubated with α-LG, LG preimmune serum, α-KZ, and KZ preimmune serum, respectively. Lane 6 in a is a shorter exposure of an immunoblot from 8–24 h embryos incubated with the α-KZ antiserum that reveals the ladder-like array of titin degradation products. The protein size markers (cross-linked phosphorylase b; Sigma Chemical Co.), were visualized by Coomassie blue staining.

D-TITIN Migrates in the Megadalton Size Range

Vertebrate muscle titin isoforms range in molecular mass from 2,993 to 3,700 kD (Labeit and Kolmerer, 1995; Kolmerer et al., 1996; Sorimachi et al., 1997). Because the mini-titins identified in Drosophila are smaller (500–1,200 kD; Ayme-Southgate et al., 1991, 1995; Fyrberg et al., 1992; Lakey et al., 1993), they are unlikely to span a half-sarcomere from the Z-disk to the M-line. Mutational analysis further suggests that these proteins do not provide the elasticity and proposed scaffolding functions of vertebrate titin. Our data shows that NH2-terminal regions of D-TITIN localize to the Z-disk, that D-TITIN has significant homology to vertebrate titins, and that D-TITIN is expressed early and continuously in striated muscles in Drosophila. These characteristics make D-TITIN a good candidate for the Drosophila homologue of vertebrate muscle titin. If it is indeed the homologue, D-TITIN should be in the 2–4-MD size range. To test this prediction, total protein extracts from 8–24 h embryos were prepared (in muscle precursors, D-TITIN is first detected at ∼7 h by immunostaining of embryos), proteins were separated on denaturing polyacrylamide gradient gels (2.5–7.5%), and were transferred to nitrocellulose filters. Immunoblots incubated with both α-LG and α-KZ detected a discrete band in the megadalton size range, consistent with vertebrate titin (Fig. 5 a, lanes 2 and 4). α-LG and α-KZ preimmune sera revealed no cross-reacting polypeptides (Fig. 5 a, lanes 3 and 5). Thus, D-TITIN is likely to be the Drosophila homologue of vertebrate sarcomeric titin based on size, sequence similarity, developmental expression and subcellular localization.

To determine the size of chromosome-associated D-TITIN in nonmuscle cells, total protein extracts were prepared from both 0–2 h Drosophila embryos (myogenesis does not begin until several hours later) and from HeLa cells (epithelial cells). In the 0–2 h embryonic extracts, we detected a discrete high molecular mass polypeptide of identical size on immunoblots with both α-LG (Fig. 5 b, lane 2) and α-KZ (Fig. 5 b, lane 4). No cross-reacting polypeptides were detected with either α-LG or α-KZ preimmune sera (Fig. 5 b, lanes 3 and 5). Using total cell extracts from HeLa cells, we also detected a megadalton polypeptide with both α-LG and α-KZ antisera (Fig. 5 c, lanes 2 and 4), with no staining with the preimmune sera (Fig. 5 c, lanes 3 and 5). Thus, antibodies to D-TITIN detected a very high molecular mass polypeptide in nonmuscle cells from Drosophila and in human epithelial cells. Since, by immunofluorescence, the only detectable staining with these antibodies on Drosophila 0–2 h embryos and HEp-2 cells is chromosomal, we concluded that the chromosomal form of D-TITIN migrates in the megadalton size range and is approximately as large as the muscle form.

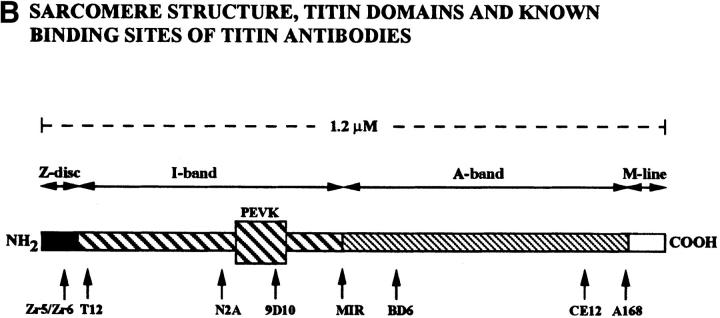

Antibodies to Vertebrate Muscle Titin Stain Human Chromosomes

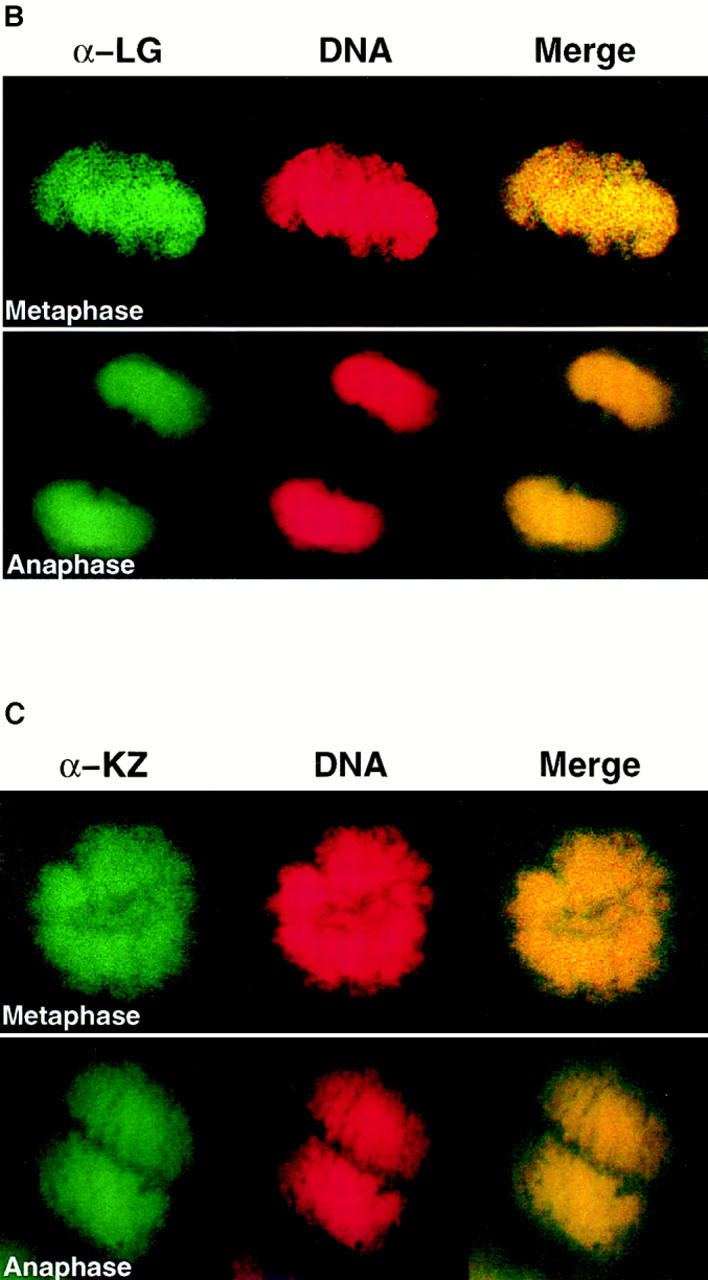

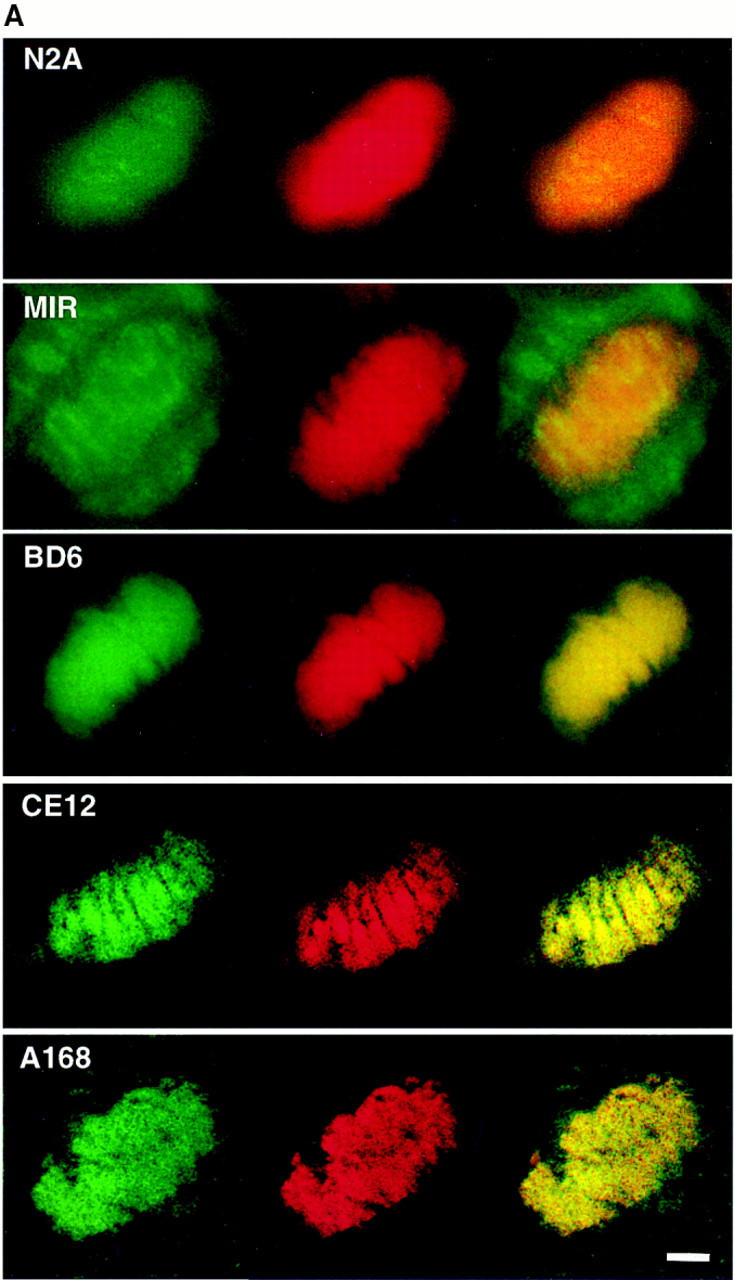

Given that Drosophila TITIN localized to condensed Drosophila mitotic chromosomes and that antibodies directed against this protein also stained human chromosomes, we were curious whether antibodies to vertebrate muscle titin also stained condensed chromosomes. We used a panel of eight antibodies directed against different epitopes of vertebrate titin to immunostain HEp-2 cells. Six of the eight antibodies directed against vertebrate titin stained the condensed chromosomes in a pattern indistinguishable from that observed with the original scleroderma serum and the antibodies to the D-TITIN protein (Fig. 6, A and B). The antibodies that gave chromosomal localization include three mouse monoclonals, two of which recognize distinct epitopes in the A-band (BD6 and CE12; Whiting et al., 1989) and one of which recognizes the PEVK domain in the I-band (9D10; data not shown; Wang et al., 1991). We also observed chromosomal staining with two rabbit polyclonal antibodies to vertebrate titin: N2A, which recognizes an I-band epitope in skeletal titin, and A168, which recognizes an M-line epitope (Linke et al., 1996). Finally, the MIR human autoimmune serum, which recognizes an I/A-band epitope (Gautel et al., 1993), also stained condensed mitotic chromosomes of HEp-2 cells although additional staining of the mitotic apparatus was visible with this serum (Fig. 6 A). The two vertebrate titin antibodies that did not recognize titin on HEp-2 chromosomes, anti-Zr5/Zr6 and T12, are directed against NH2-terminal regions of titin that either map to the Z-disk and bind to α-actinin (anti-Zr5/Zr6; Sorimachi et al., 1997) or map to the Z-disk/I-band junction (T12; Fürst et al., 1988). The NH2-terminal region of the D-Titin isoform encoded by the KZ cDNA does not contain regions homologous to the α-actinin–binding regions of vertebrate titin. It is likely that cDNAs encoding the NH2 terminus of the muscle D-TITIN isoform will reveal homologies to the α-actinin– binding regions since (a) the COOH-terminal sequence of α-actinin from Drosophila is highly homologous to the COOH terminus of human α-actinin (Fyrberg et al., 1990) and (b) the anti-Zr5/Zr6 antiserum stains Drosophila myofibrils but not chromosomes. Thus, titin localizes to chromosomes in both Drosophila embryos and human cells although the chromosomal and muscle forms of titin may vary in their NH2 termini.

Figure 6.

Titin localizes to condensed mitotic chromosomes. HEp-2 cells double-stained with antibodies to vertebrate titin (green) and propidium iodide (red). The merged image is on the right (yellow in region of overlap). From top to bottom: N2A, MIR, BD6, CE12, and A168. Antibodies directed against the most NH2-terminal regions of vertebrate titin, anti-Zr5/Zr6 and T12, did not detect titin on chromosomes. Antibodies directed against the I-band regions of titin, N2A and 9D10 (not shown) showed weak chromosomal staining. The MIR serum (I/A-band junction) showed stronger chromosomal staining, as well as staining of the mitotic apparatus. Titin antibodies directed against A-band epitopes (BD6 and CE12) and the M-line epitope (A168) showed very strong staining of condensed chromosomes. Bar, 5 μm.

Discussion

Proposed Function for Titin in Chromosome Structure

The uniform distribution of titin along condensed chromosomes suggests a structural role for titin in chromosome condensation, a role similar to the one titin plays as a scaffolding element in the sarcomeres (Trinick, 1994, 1996). Chromosome condensation during mitosis is essential for proper segregation and for compacting chromosomes so that they are no longer at the cleavage furrow during cytokinesis (for review see Hirano, 1995; Koshland and Strunnikov, 1996). Chromosome condensation is thought to occur by a deterministic process based on the fixed length and banding patterns of individual chromosomes in a given cell-type, the invariant position of specific sequences within a chromosome, and the fixed axial diameter of mitotic chromosomes (Koshland and Strunnikov, 1996). The invariant axial diameter of condensed mitotic chromosomes suggests the involvement of a protein that functions in part as a “molecular ruler”, a function that has already been ascribed to titin in muscles (Trinick, 1994, 1996). Thus, we can envision the chromosomal form of titin functioning in the assembly of the higher-order structure observed in condensed mitotic chromosomes, perhaps determining the length and/or axial diameter of condensed chromosomes.

Titin is the elastic component of sarcomeres where it acts as a molecular spring that prevents sarcomere disruption when muscles are overstretched. Likewise, the chromosomal form of titin could provide elasticity to chromosomes and resistance to chromosome breakage during mitosis. The elastic properties of purified titin (Kellermayer et al., 1997; Rief et al., 1997; Tskhovrebova et al., 1997) correspond well to the recently described elastic properties of chromosomes in living cells (Houchmandzadeh et al., 1997). Studies on vertebrate myofibrils have shown that the PEVK domain and the Ig/FN3 repeats constitute a two-spring system acting in series to confer reversible extensibility to titin (Linke et al., 1996; Trombitas et al., 1998). Under physiological stretching conditions, the Ig/FN3 domains straighten and the PEVK domain reversibly unfolds. Under more extreme nonphysiological stretching conditions, the Ig and FN3 domains also unfold. However, refolding of the Ig and FN3 repeats is slow and occurs only in the absence of stretch force. Similarly, metaphase chromosomes from living cells also show two levels of extensibility (Houchmandzadeh et al., 1997). Metaphase chromosomes from cultured newt lung cells can be stretched up to 10 times their normal length and return to their native shape. Further nonphysiological extensions of chromosomes from 10 to 100-fold are irreversible. The discovery of titin on chromosomes integrates the mechanical properties of muscle titin with the elastic properties of eukaryotic chromosomes.

Does titin remain associated with chromosomes during interphase? Although we detected titin in the nucleus during interphase with both the Drosophila titin antibodies and the antibodies directed against vertebrate titin, the resolution of confocal microscopy does not allow us to directly ask if titin remains bound to chromosomes. However, we have looked at the accumulation of D-TITIN on salivary gland polytene chromosomes from Drosophila third instar larvae using the α-KZ antiserum. Based on gene activity and chromatin ultrastructure, polytene chromosomes are functionally similar to diploid interphase chromosomes (Tissièrres et al., 1974; Elgin and Boyd, 1975; Bonner and Pardue, 1976; Woodcock et al., 1976). Low level D-TITIN staining was observed throughout the chromosomes with several discrete sites of higher accumulation (data not shown). These results suggest that titin remains associated with relatively decondensed interphase chromosomes, consistent with the chromosome core structure being templated during interphase (Andreasson et al., 1997). Measurements made at different stages in the cell cycle indicate that chromosome flexibility increases during the transition from interphase to metaphase (Houchmandzadeh et al., 1997). Regulated phosphorylation of titin may control the assembly of interphase chromosomes into the higher-order structure of metaphase chromosomes and indirectly alter chromosome flexibility.

Chromosomal and Muscle Forms of Titin

The chromosomal and muscle forms of titin are unlikely to be identical. Although both forms of D-TITIN appeared to comigrate, the resolution of the gradient gels used to detect both the muscle and chromosomal forms of D-TITIN may be insufficient to resolve the respective molecular mass differences. The most 5′ D-Titin cDNA isolated in this work, which encodes an NH2 terminus, does not contain the most 5′ sequences found in vertebrate muscle titin, the so-called Z-repeats that bind to α-actinin in the Z-disk (Turnacioglu et al., 1996; Ohtsuka et al., 1997a,b; Sorimachi et al., 1997). Antibodies directed against the α-actinin–binding region of vertebrate titin did not recognize titin on human chromosomes, although antibodies directed to more COOH-terminal epitopes were reactive (Fig. 6). Furthermore, the most 5′ cDNA contains a unique 81–amino acid sequence at the NH2 terminus. Titin mRNA and protein have been detected in BHK (Jäckel et al., 1997). Moreover, in a subline derived from the BHK cells, the titin gene contained deletions in the Z-disk region. Titin mRNA was still detected in the mutant cell line. Altogether, these results suggest that muscle titin and chromosomal titin vary at least in their most NH2-terminal regions. Our results with D-TITIN suggest that the muscle and chromosomal forms of titin are encoded by splice variants of the same gene, and that we have not cloned the exons encoding the most NH2-terminal regions of muscle titin. Polytene chromosome in situ hybridization and genomic southern analysis revealed that D-Titin is a single-copy gene (unpublished results). Determination of whether vertebrate chromosomal and muscle titins are also splice variants of the same gene or, instead, are encoded by two closely related genes awaits further investigation of vertebrate titin.

The previously known components of condensed chromatin include DNA, histones, topoisomerase II, the SMC family of proteins (for review see Chuang et al., 1994; Earnshaw and Mackay, 1994; Hirano and Mitchison, 1994; Peterson, 1994; Hirano, 1995; Saitoh et al., 1995; Strunnikov et al., 1995; Holt and May, 1996; Koshland and Strunnikov, 1996; Warburton and Earnshaw, 1997), the condensins, three recently identified proteins that form a complex with SMC family members (Hirano et al., 1997), and the cohesins, proteins that link condensation and sister chromatid cohesion (Guacci et al., 1997; Michaelis et al., 1997). Topo II and SMC were identified as the two most abundant chromosomal “scaffold” proteins, which by definition, comprise an insoluble fraction purified from isolated mitotic chromosomes. These scaffold proteins are proposed to determine the characteristic shape of mitotic chromosomes. Both genetic and in vitro depletion studies confirm that topo II and SMC proteins are indeed required for chromosome condensation and subsequent chromosome segregation; whether their roles in chromosome condensation are structural or entirely enzymatic, however, remains to be determined (see previously cited reviews and Kimura and Hirano, 1997; Sutani and Yanagida, 1997). If titin is part of the chromosomal scaffold, why was titin not identified in the initial biochemical analyses of scaffold proteins? The simplest explanation is based on the size of titin. Almost all of the protein gels used to identify topo II, SMC and other scaffold proteins were 12.5% polyacrylamide gels and did not resolve proteins of molecular mass >200 kD. Indeed, in almost every published photograph of a protein gel of purified scaffold components, there is a high molecular mass component that fails to enter the gel (Adolph et al., 1977; Paulson and Laemmli, 1977; Laemmli et al., 1978; Lewis and Laemmli, 1982; Earnshaw and Laemmli, 1983). We demonstrated that chromosomally associated titin from HEp-2 cells and early Drosophila embryos migrates in the megadalton size range. Although a protein of this size can be resolved in 2.5–7.5% gradient gels, titin would not enter the 12.5% gels typically used in chromosome scaffold studies.

Titin as an Autoantigen

As an alternative to a biochemical approach, autoimmune sera have been successfully used as probes in the isolation of novel chromosomal proteins and for expression cloning of the corresponding genes (for review see Earnshaw and Rattner, 1991; Tan, 1989, 1991; Fritzler, 1997). Even though the prevalence for autoantibodies against nuclear components appears to be higher, the spectrum of autoantibodies identified in sera from patients with autoimmune diseases is much broader, and includes numerous cytoplasmic antigens as well as several extracellular matrix proteins (Fritzler, 1997). Many autoantigens are proteins very well conserved throughout evolution, ranging from species as distant as man, fish, amphibia, Drosophila, yeast, and plants (Snyder and Davis, 1988; Tan et al., 1987; Mole- Bajer et al., 1990; Brunet et al., 1993; Shibata et al., 1993; Rendon et al., 1994; Bejarano and Valdivia, 1996). The work presented here is the first to identify titin autoantibodies in scleroderma sera, the first to reveal titin as a chromosomal component and, to our knowledge, the first successful cloning of a Drosophila gene using a human autoimmune serum.

The identification of autoantibodies against titin until now has been restricted to a subset of patients with myasthenia gravis (MG) who have also developed thymus neoplasia (Aarli et al., 1990; Gautel et al., 1993). However, the stimulus for the autoimmune response to titin may be due to molecular mimicry. This immunoreactivity is directed exclusively to a single epitope of titin, the MIR epitope. This epitope is shared with neurofilaments that are overexpressed in these thymomas (Marx et al., 1996). Since titin MIR autoantibodies can be detected in 97% of sera from MG-thymoma patients, the MIR epitope of titin is a sensitive marker for evaluating the presence of thymoma in MG patients (Gautel et al., 1993). The isolation of the D-Titin gene in Drosophila using a scleroderma autoimmune serum raises the inevitable question of whether titin may represent a new, unidentified autoantigen in scleroderma.

D-Titin represents the third Drosophila member of the titin gene family. The other two family members, both of which are referred to as mini-titins (Vibert et al., 1996), include KETTIN and PROJECTIN. KETTIN is a 500-kD family member with low homology to vertebrate titin. KETTIN has been proposed to be one of the structural components of Z-disks; however, mutations in the corresponding gene have not yet been described (Lakey et al., 1993). PROJECTIN is a highly homologous ∼1,200-kD titin family member most closely related to TWITCHIN (Ayme-Southgate et al., 1991, 1995; Fyrberg et al., 1992), a Caenorhabditis elegans mini-titin that binds to myosin filaments in body wall muscles. TWITCHIN has the Ig and FN3 repeats and a myosin light chain kinase domain near the COOH terminus, but does not have an obvious PEVK region (Benian et al., 1989; Benian et al., 1996). TWITCHIN is thought to regulate myosin activity because mutations in twitchin (unc-22) cannot develop or sustain muscle contractions (Waterston et al., 1980; Moerman et al., 1988). Furthermore, mutations in twitchin can be suppressed by mutations in the myosin heavy chain gene. Lethal alleles of Drosophila PROJECTIN exist as mutations in the bent locus. Homozygous bent mutant animals die as late embryos but, unlike twitchin mutant worms, have apparently normal muscle contractions (Fyrberg et al., 1992; Ayme-Southgate et al., 1995), suggesting normal sarcomere organization. The identification of a true titin homologue in a genetically tractable organism will greatly facilitate the analysis of titin function both in sarcomeres and in chromosome structure and flexibility. Indeed, we have mapped the D-Titin gene to a cytological interval known to contain only a single gene. A thorough characterization of D-Titin mutations is currently underway.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Isenberg for providing scleroderma sera from patients at the Immunology Unit, King's College (London, UK). We thank S. Labeit and J. Trinick for vertebrate titin antibodies. We thank J. Mason and A. Spradling for fly stocks. We thank M. Delannoy and K.D. Henderson for assistance with the NORAN confocal microscope. We thank P. Tuma for advice with the protein gradient gels. We thank D. Barrick, J.D. Castle, K.D. Henderson, A. Hubbard, C. Machamer, and K. Wilson for their critical comments on the manuscript. We also thank F. Domingues for assistance during the expression screen and all the members of the Andrew laboratory for their help and patience during the final stages of this study.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- E

glutamic acid

- FN3

fibronectin type III

- K

lysine

- MG

myasthenia gravis

- MIR

major immunogenic region

- ORF

open reading frame

- P

proline

- V

valine

Footnotes

C. Machado was supported by a Ph.D. fellowship from Junta Nacional de Investigação Cientifica e Tecnológica (JNICT) and, in part, by grants from Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento and Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. This work was supported by a grant from the Council for Tobacco Research to D.J. Andrew and a grant from JNICT to C.E. Sunkel.

Address all correspondence to Deborah J. Andrew, Department of Cell Biology and Anatomy, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 725 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21205-2196. Tel.: (410) 614-2722. Fax: (410) 955-4129. E-mail: debbie_andrew@qmail.bs.jhu.edu

References

- Aarli JA, Stefansson K, Marton LSG, Wollmann RL. Patients with myasthenia gravis and thymoma have in their sera IgG autoantibodies against titin. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;82:284–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb05440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolph KW, Cheng SM, Paulson JR, Laemmli UK. Isolation of a protein scaffold from mitotic HeLa cell chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:4937–4941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.11.4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasson PR, Lacroix FB, Margolis RL. Chromosomes with two intact axial cores are induced by G2 checkpoint override: evidence that DNA decatenation is not required to template the chromosome structure. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:29–43. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayme-Southgate A, Vigoreaux J, Benian G, Pardue ML. Drosophilahas a twitchin/titin-related gene that appears to encode projectin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7973–7977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.7973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayme-Southgate A, Southgate R, Saide J, Benian GM, Pardue ML. Both synchronous and asynchronous muscle isoforms of projectin (the Drosophila bentlocus product) contain functional kinase domains. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:393–403. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejarano LA, Valdivia MM. Molecular cloning of an intronless gene for the hamster centromere antigen CENP-B. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1307:21–25. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(96)00039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benian GM, Kiff JE, Neckelmann N, Moerman DG, Waterston RH. Sequence of an unusually large protein implicated in regulation of myosin activity in C. elegans. . Nature. 1989;342:45–50. doi: 10.1038/342045a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benian GM, Tang X, Tilney TL. Twitchin and related giant Ig super family members of C. elegansand other invertebrates. Adv Biophys. 1996;33:183–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner JJ, Pardue ML. The effect of heat shock on RNA synthesis in Drosophilatissues. Cell. 1976;8:43–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NH, Kafatos FC. Functional cDNA libraries from Drosophilaembryos. J Mol Biol. 1988;203:425–437. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet C, Quan T, Craft J. Comparison of the Drosophila melanogaster, human and murine SmB cDNAs: evolutionary conservation. Gene. 1993;124:269–273. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90404-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Ortega, J.A., and V. Hartenstein. 1985. The Embryonic Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Springer-Verlag, Berlin. 227 pp.

- Chuang P-T, Albertson DG, Meyer BJ. DPY-27: a chromosome condensation protein homolog that regulates C. elegansdosage compensation through association with the X chromosome. Cell. 1994;79:459–474. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colley NJ, Tokuyasu KT, Singer SJ. The early expression of myofibrillar proteins in round post mitotic myoblasts of embryonic skeletal muscle. J Cell Sci. 1990;95:11–22. doi: 10.1242/jcs.95.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw WC, Laemmli UK. Architecture of metaphase chromosomes and chromosome scaffolds. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:84–93. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw WC, Rattner JB. The use of autoantibodies in the study of nuclear and chromosomal organization. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;35:135–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw WC, Mackay AM. Role of nonhistone proteins in the chromosomal events of mitosis. FASEB (Fed Am Soc Exp Biol) J. 1994;8:947–956. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.12.8088460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilertsen KJ, Kazmierski ST, Keller TCS., III Cellular titin localization in stress fibers and interaction with myosin II filaments in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:1201–1210. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.5.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgin SCR, Boyd JB. The proteins of polytene chromosomes of Drosophila hydei. . Chromosoma. 1975;51:135–145. doi: 10.1007/BF00319831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppenberger HM, Perriard JC, Rosenberg UB, Strehler EE. The M r165,000 M-protein myomesin: a specific protein of cross-striated muscle cells. J Cell Biol. 1981;89:185–193. doi: 10.1083/jcb.89.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiburg A, Gautel M. A molecular map of the interaction between titin and myosin-binding protein C. Implications for sarcomeric assembly in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Biochem. 1996;235:317–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzler MJ. Autoantibodies: diagnostic fingerprints and etiological perplexities. Clin Invest Med. 1997;20:103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton AB, Alftine C. Organization of protein and mRNA for titin and other myofibril components during myofibrillogenesis in cultured chicken skeletal muscle. Cell Struct Funct. 1997;22:51–58. doi: 10.1247/csf.22.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fürst DO, Osborn M, Nave R, Weber K. The organization of titin filaments in the half-sarcomere revealed by monoclonal antibodies in immunoelectron microscopy: a map of ten nonrepetitive epitopes starting at the Z-line extends close to the M-line. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:1563–1572. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.5.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fürst DO, Nave R, Osborn M, Weber K. Repetitive titin epitopes with a 42 nm spacing coincide in relative position with known A band striations also identified by major myosin-associated proteins. An immunoelectron-microscopical study on myofibrils. J Cell Sci. 1989;94:119–125. doi: 10.1242/jcs.94.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyrberg E, Kelly M, Ball E, Fyrberg C, Reedy MC. Molecular genetics of Drosophilaα-actinin: mutant alleles disrupt Z disk integrity and muscle insertions. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:1999–2011. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.6.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyrberg CC, Labeit S, Bullard B, Leonard B, Fyrberg E. Drosophila projectin: relatedness to titin and twitchin and correlation with lethal(4)102 CDa and bent-dominantmutants. Proc R Lond B Biol Sci. 1992;249:33–40. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1992.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautel M, Goulding D. A molecular map of titin/connectin elasticity reveals two different mechanisms acting in series. FEBS (Fed Eur Biochem Soc) Lett. 1996;385:11–14. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00338-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautel M, Lakey A, Barlow DP, Holmes Z, Scales S, Leonard K, Labeit S, Mygland A, Gilhus NE, Aarli JA. Titin antibodies in myasthenia gravis: identification of a major immunogenic region of titin. Neurology. 1993;43:1581–1585. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.8.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein LSB, Laymon RA, McIntosh JR. A microtubule-associated protein in Drosophila melanogaster: identification, characterization, and isolation of coding sequences. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:2076–2087. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.6.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guacci V, Koshland D, Strunnikov A. A direct link between sister chromatid cohesion and chromosome condensation revealed through the analysis of MCD1 in S. cerevisiae. . Cell. 1997;91:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80008-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartenstein, V. 1993. Atlas of Drosophila development. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, New York. 57 pp.

- Hirano T. Biochemical and genetic dissection of mitotic chromosome condensation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:357–361. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T, Mitchison TJ. A heterodimeric coiled-coil protein required for mitotic chromosome condensation in vitro. Cell. 1994;79:449–458. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90254-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T, Kobayashi R, Hirano M. Condensins, chromosome condensation protein complexes containing XCAP-C, XCAP-E and a Xenopus homolog of the DrosophilaBarren protein. Cell. 1997;89:511–521. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, May GS. An extragenic suppressor of the mitosis-defective bim6 mutation of Aspergillus nidulanscodes for a chromosome scaffold protein. Genetics. 1996;142:777–787. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.3.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houchmandzadeh B, Marko JF, Chatenay D, Libchaber A. Elasticity and structure of eukaryote chromosomes studied by micromanipulation and micropipette aspiration. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1–12. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houmeida A, Holt J, Tskhovrebova L, Trinick J. Studies of the interaction between titin and myosin. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1471–1481. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Suzuki T, Kimura S, Ohashi K, Higuchi H, Sawada H, Shimizu T, Shibata M, Maruyama K. Extensible and less-extensible domains of connectin filaments in stretched vertebrate skeletal muscle as detected by immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy using monoclonal antibodies. J Biochem. 1988;104:504–508. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäckel M, Witt C, Antonova O, Curdt I, Labeit S, Jockusch H. Deletion in the Z-line region of the titin gene in a baby hamster kidney cell line, BHK-21-Bi. FEBS (Fed Eur Biochem Soc) Lett. 1997;408:21–24. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeppesen P, Nicol L. Non-kinetochore directed autoantibodies in scleroderma/CREST. Identification of an activity recognizing a metaphase chromosome core non-histone protein. Mol Biol Med. 1986;3:369–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller TCS. Structure and function of titin and nebulin. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:32–33. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellermayer MSZ, Smith SB, Granzier HL, Bustamante C. Folding-unfolding transitions in single titin molecules characterized with laser tweezers. Science. 1997;276:1112–1116. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5315.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, Hirano T. ATP-dependent positive supercoiling of DNA by 13S condensin: a biochemical implication for chromosome condensation. Cell. 1997;90:625–634. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80524-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinbara K, Sorimachi H, Ishiura S, Suzuki K. Muscle-specific calpain, p94, interacts with the extreme C-terminal region of connectin, a unique region flanked by two immunoglobulin C2 motifs. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;342:99–107. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolmerer B, Olivieri N, Witt C, Herrmann BG, Labeit S. Genomic organization of the M-line titin and its tissue-specific expression in two distinct isoforms. J Mol Biol. 1996;256:556–563. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshland D, Strunnikov A. Mitotic chromosome condensation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:305–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labeit S, Kolmerer B. Titins, giant proteins in charge of muscle ultrastructure and elasticity. Science. 1995;270:293–296. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labeit S, Barlow DP, Gautel M, Gibson T, Gibson M, Holt J, Hsieh C-L, Francke U, Leonard K, Wardale J, Whiting A, Trinick J. A regular pattern of two types of 100-residue motif in the sequence of titin. Nature. 1990;345:273–276. doi: 10.1038/345273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labeit S, Gautel M, Lakey A, Trinick J. Towards a molecular understanding of titin. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1992;11:1711–1716. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labeit S, Kolmerer B, Linke WA. The giant protein titin. Circ Res. 1997;80:290–294. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK, Cheng SM, Adolf KW, Paulson JR, Brown JA, Baumbach WR. Metaphase chromosome structure: the role of nonhistone proteins. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1978;423:351–361. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1978.042.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey A, Labeit S, Gautel M, Ferguson J, Barlow DP, Leonard K, Bullard B. Kettin, a large modular protein in the Z-disk of insect muscles. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1993;12:2863–2871. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05948.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoy EC. Systemic sclerosis. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 1996;22:675–693. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CD, Laemmli UK. Higher order metaphase chromosome structure: evidence for metalloprotein interactions. Cell. 1982;29:171–181. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke WA, Ivemeyer M, Olivieri N, Kolmerer B, Ruegg JC, Labeit S. Towards a molecular understanding of the elasticity of titin. J Mol Biol. 1996;261:62–71. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke WA, Ivemeyer M, Labeit S, Hinssen H, Ruegg JC, Gautel M. Actin-titin interaction in cardiac myofibrils: probing a physiological role. Biophys J. 1997;73:905–919. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78123-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama K. Connectin/titin, giant elastic protein of muscle. FASEB (Fed Am Soc Exp Biol) J. 1997;11:341–345. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.5.9141500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama K, Endo T, Kume H, Kawamura Y, Kanzawa N, Nakauchi Y, Kimura S, Kawashima S. A novel domain sequence of connectin localized at the I band of skeletal muscle sarcomeres: homology to neurofilament subunits. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;194:1288–1291. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx A, Wilisch A, Schultz A, Greiner A, Magi B, Pallini V, Schalke B, Toyka C, Nix W, Kirchner T, Müller-Hermelink H-K. Expression of neurofilaments and of a titin epitope in thymic epithelial tumors. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:1839–1850. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis C, Ciosk R, Nasmyth K. Cohesins: chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids. Cell. 1997;91:47–58. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moerman GD, Benian GM, Barstead RJ, Schrieffer LA, Waterston RH. Identification and intracellular localization of the unc-22 gene product of Caenorhabditis elegans. . Genes Dev. 1988;2:93–105. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mole-Bajer J, Bajer AS, Zinkowski RP, Balczon RD, Brinkley BR. Autoantibodies from a patient with scleroderma CREST recognized kinetochores of the higher plant Haemanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;17:1627–1631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mount SM. A catalogue of splice junction sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:459–472. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.2.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mount SM, Burks C, Hertz G, Stormo GD, White O, Fields C. Splicing signals in Drosophila: intron size, information content and consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4255–4262. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.16.4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura RM, Tan EM. Update on autoantibodies to intracellular antigens in systemic rheumatic diseases. Clin Lab Med. 1992;12:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermann WM, Gautel M, Steiner F, van der Ven PF, Weber K, Fürst DO. The structure of the sarcomeric M band: localization of defined domains of myomesin, M-protein, and the 250-kD carboxy-terminal region of titin by immunoelectron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:1441–1453. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.6.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermann WM, Gautel M, Weber K, Fürst DO. Molecular structure of the sarcomeric M band: mapping of titin and myosin binding domains in myomesin and the identification of a potential regulatory phosphorylation site in myomesin. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1997;16:211–220. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuka H, Yajima H, Maruyama K, Kimura S. Binding of the N-terminal 63 kD portion of connectin/titin to α-actinin as revealed by the yeast two-hybrid system. FEBS (Fed Eur Biochem Soc) Lett. 1997a;401:65–67. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01432-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuka H, Yajima H, Maruyama K, Kimura S. The N-terminal Z-repeat 5 of connectin/titin binds to the C-terminal region of α-actinin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997b;235:1–3. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson JR, Laemmli UK. The structure of histone-depleted chromosomes. Cell. 1977;12:817–828. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90280-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CL. The SMC family: novel motor proteins for chromosome condensation? . Cell. 1994;79:389–392. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90247-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendon MC, Bolivar J, Ortiz M, Valdivia MM. Immunodetection of the ribosomal transcription factor UBF at the nucleolus organizer regions of fish cells. Cell Struct Funct. 1994;19:153–158. doi: 10.1247/csf.19.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter R, Panganiban GEF, Hoffmann FM, Scott MP. Homeotic genes regulate the spatial expression of putative growth factors in the visceral mesoderm of Drosophilaembryos. Development. 1990;110:1031–1040. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.4.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rief M, Gautel M, Oesterhelt F, Fernandez JM, Gaub HE. Reversible unfolding of individual titin immunoglobulin domains by AFM. Science. 1997;276:1109–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5315.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rio DC, Laski FA, Rubin GM. Identification and immunochemical analysis of biologically active DrosophilaP-element transposase. Cell. 1986;44:21–32. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90481-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saide JD, Chin-Bow S, Hogan-Sheldon J, Busquets-Turner L, Vigoreaux JO, Valgeirsdottir K, Pardue ML. Characterization of components of Z-bands in the fibrillar flight muscle of Drosophila melanogaster. . J Cell Biol. 1989;109:2157–2167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.5.2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh N, Goldberg I, Earnshaw WC. The SMC proteins and the coming of age of the chromosome scaffold hypothesis. BioEssays. 1995;17:759–766. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastyén MG, Wolff JA, Greaser ML. Characterization of a 5.4 kb cDNA fragment from the Z-line of rabbit cardiac titin reveals phosphorylation sites for proline-directed kinases. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:3029–3037. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.9.3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata S, Muryos T, Saitoh Y, Brumeanu TD, Bona CA, Kasturi KN. Immunochemical and molecular characterization of anti-RNA polymerase I autoantibodies produced by tight skin mouse. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:984–992. doi: 10.1172/JCI116675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder M, Davis RW. A gene important for chromosome segregation and other mitotic functions in S. cerevisiae. . Cell. 1988;54:743–754. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)90977-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorimachi H, Kinbara K, Kimura S, Takahashi M, Ishiura S, Sasagawa N, Sorimachi N, Shimada H, Tagawa K, Maruyama K, Suzuki K. Muscle-specific calpain, p94, responsible for limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A, associates with connectin through IS2, a p94-specific sequence. J Mol Biochem. 1995;270:31158–31162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorimachi H, Freiburg A, Kolmerer B, Ishiura S, Stier G, Gregorio C, Labeit D, Linke WA, Suzuki K, Labeit S. Tissue-specific expression and α-actinin binding properties of the Z-disk titin. Implications for the nature of vertebrate Z-disk. J Mol Biol. 1997;271:1–8. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soteriou A, Gamage M, Trinick J. A survey of the interactions made by the giant protein titin. J Cell Sci. 1993;104:119–123. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire JM. Architecture and function in the muscle sarcomere. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:247–257. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strunnikov AV, Hogan E, Koshland D. SMC-2, a Saccharomyces cerevisiaegene essential for chromosome segregation and condensation defines a subgroup within the SMC-family. Genes Dev. 1995;9:587–599. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.5.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutani T, Yanagida M. DNA renaturation activity of the SMC complex implicated in chromosome condensation. Nature. 1997;388:798–801. doi: 10.1038/42062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano-Ohmuro H, Nakauchi Y, Kimura S, Maruyama K. Autophosphorylation of β-connectin (titin 2) in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;183:31–35. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91604-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamkun JW, Kahn RA, Kissinger M, Brizuela BJ, Rulka C, Scott MP, Kennison JA. The arf-like gene encodes an essential GTP-binding protein in Drosophila. . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3120–3124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan EM. Antinuclear antibodies: diagnostic markers for autoimmune diseases and probes for cell biology. Adv Immunol. 1989;44:93–151. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan EM. Autoantibodies in pathology and cell biology. Cell. 1991;67:841–842. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90356-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, E.M., G. Reimer, and K. Sullivan. 1987. Intracellular autoantigens: diagnostic fingerprints but etiological dilemmas. In Autoimmunity and autoimmune disease. D. Evered and J. Whelan, editors. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, NY. 25–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tautz D, Pfeifle C. A non-radioactive in situ hybridization method for the localization of specific RNAs in Drosophilaembryos reveals translational control of the segmentation gene hunchback. Chromosoma. 1989;98:81–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00291041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissièrres A, Mitchell HK, Tracy UM. Protein synthesis in salivary glands of Drosophila melanogaster: relation to chromosome puffs. J Mol Biol. 1974;84:389–398. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90447-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinick J. Titin and nebulin: protein rulers in muscle? . Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:405–408. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinick J. Titin as a scaffold and spring. Cytoskeleton Curr Biol. 1996;6:258–260. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00472-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trombitas K, Granzier H. Actin removal from cardiac myocytes shows that near Z line titin attaches to actin while under tension. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:662–670. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.2.C662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trombitas K, Greaser ML, Pollack GH. Interaction between titin and thin filaments in intact cardiac muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1997;18:345–351. doi: 10.1023/a:1018626210300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trombitas K, Greaser M, Labeit S, Jin J-P, Kellermayer M, Helmes M, Granzier H. Titin extensibility in situ: entropic elasticity of permanently folded and permanently unfolded molecular segments. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:853–859. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tskhovrebova L, Trinick J, Sleep JA, Simmons RM. Elasticity and unfolding of single molecules of the giant muscle protein titin. Nature. 1997;387:308–312. doi: 10.1038/387308a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnacioglu KK, Mittal B, Sanger JM, Sanger JW. Partial characterization of zeugmatin indicates that it is part of the Z-band region of titin. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1996;34:108–121. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1996)34:2<108::AID-CM3>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnacioglu KK, Mittal B, Dabiri GA, Sanger JM, Sanger JW. An N-terminal fragment of titin coupled to green fluorescent protein localizes to the Z-bands in living muscle cells: overexpression leads to myofibril disassembly. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:705–717. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.4.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Ven PF, Fürst DO. Assembly of titin, myomesin and M-protein into the sarcomeric M band in differentiating human skeletal muscle cells in vitro. Cell Struct Funct. 1997;22:163–171. doi: 10.1247/csf.22.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vibert P, York ML, Castellani L, Edelstein S, Elliott B, Nyitray L. Structure and distribution of mini-titins. Adv Biophys. 1996;33:199–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Fanger BO, Guyer CA, Staros JV. Electrophoretic transfer of high-molecular weight proteins for immunostaining. Methods Enzymol. 1989;172:687–696. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(89)72038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, McCarter R, Wright R, Beverly J, Ramirez-Mitchell R. Regulation of skeletal muscle stiffness and elasticity by titin isoforms: a test of segmental extension model of resting tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7101–7105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton PE, Earnshaw WC. Untangling the role of DNA topoisomerase II in mitotic chromosome structure and function. BioEssays. 1997;19:97–99. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterston RH, Thomson JN, Brenner S. Mutants with altered muscle structure in Caenorhabditis elegans. . Dev Biol. 1980;77:271–302. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(80)90475-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White B. Immunopathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 1996;22:695–735. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting A, Wardale J, Trinick J. Does titin regulate the length of muscle thick filaments? . J Mol Biol. 1989;205:163–169. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock CLF, Safer JP, Stanchfield JE. Structural repeating units in chromatin. Exp Cell Res. 1976;97:101–110. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(76)90659-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinn K, McAllister L, Goodman CS. Sequence analysis and neuronal expression of Fasciclin I in grasshopper and Drosophila. . Cell. 1988;53:577–587. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90574-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]