Abstract

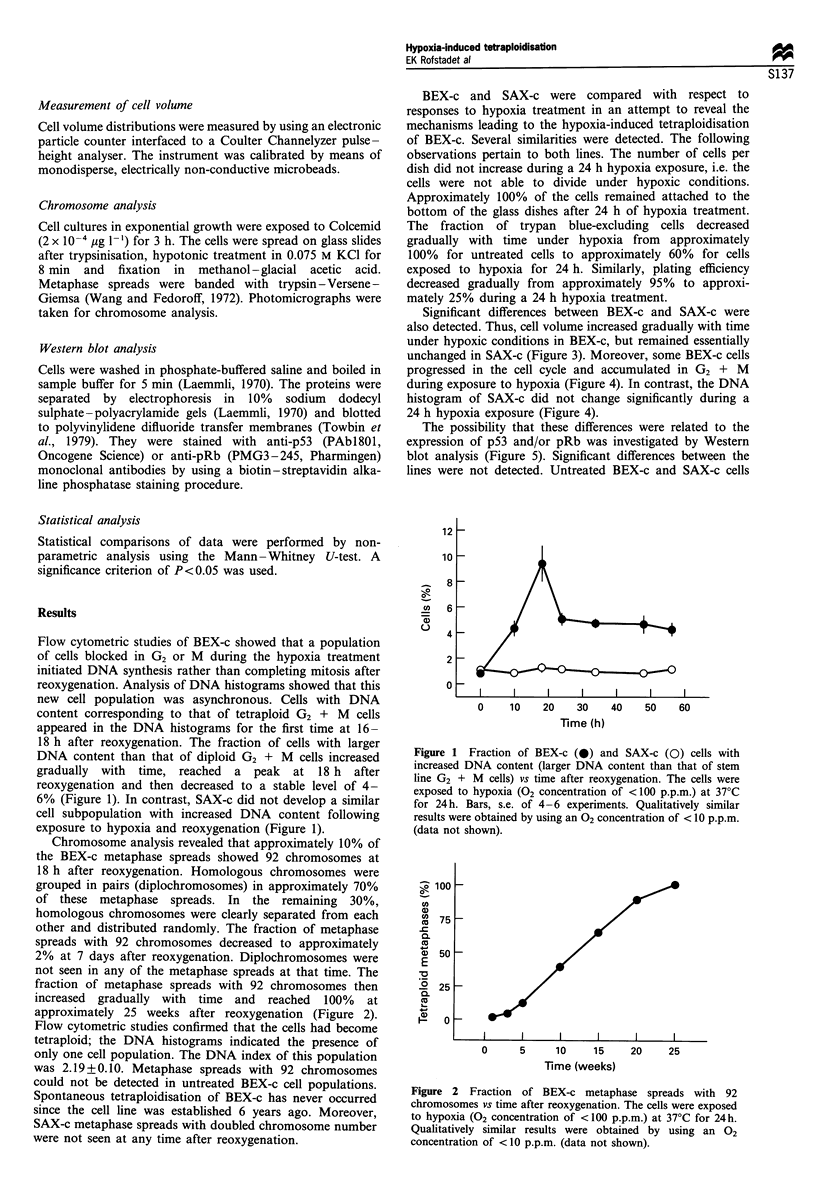

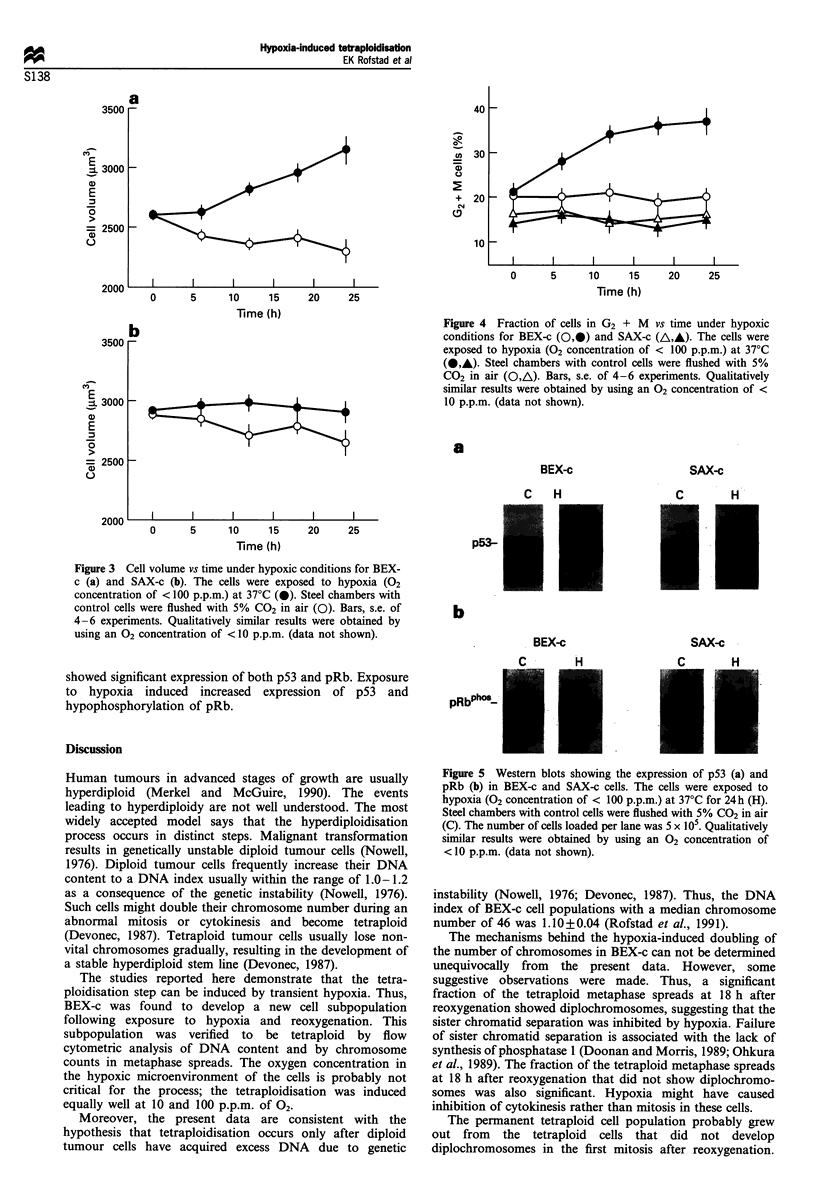

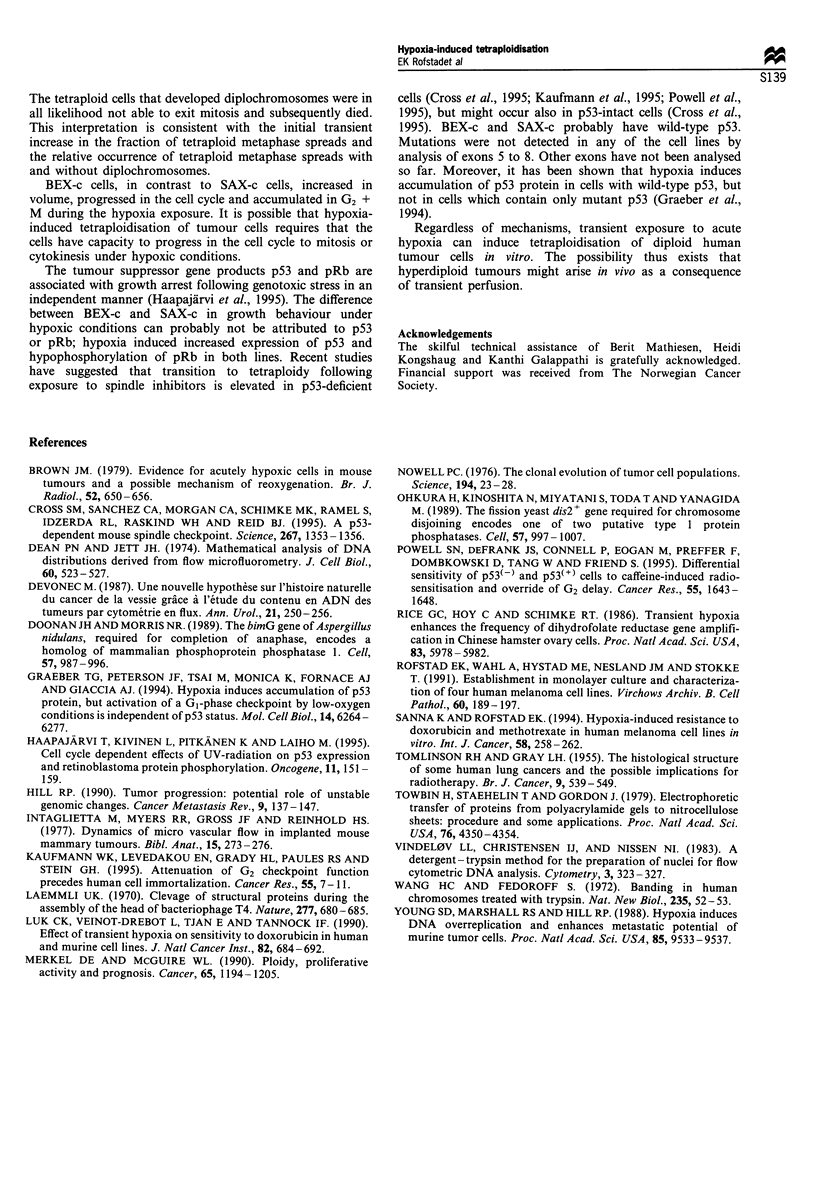

Many human tumours are hyperdiploid, particularly in advanced stages of growth. The purpose of the present work was to investigate whether exposure to hypoxia followed by reoxygenation might induce hyperploidisation of diploid human tumour cells in vitro. The investigation was performed by using the diploid melanoma cell line BEX-c (median chromosome number, 46; DNA index, 1.10 +/- 0.04) as test line and the hyperdiploid melanoma cell line SAX-c (median chromosome number, 61; DNA index, 1.42 +/- 0.03) as control line. Cell cultures kept in glass dishes in air-tight steel chambers were exposed to hypoxia (O2 concentrations < 10 p.p.m. or < 100 p.p.m.) at 37 degrees C for 24 h. DNA content was measured by flow cytometry. Metaphase spreads banded with trypsin-Versene-Giemsa were examined to determine the number of chromosomes per cell. An electronic particle counter was used to measure cell volume. The expression of p53 and pRb was studied by Western blot analysis. Transient exposure to hypoxia was found to induce a doubling of the number of chromosomes in BEX-c but not in SAX-c. The fraction of the BEX-c metaphase spreads with 92 chromosomes was approximately 10% at 18 h after reoxygenation, decreased to approximately 2% at 7 days after reoxygenation and then increased gradually with time. The whole cell population became tetraploid within 25 weeks. BEX-c and SAX-c behaved differently during the 24 h hypoxia exposure. Cell volume and fraction of cells in G2 + M increased with time in BEX-c but remained essentially unchanged in SAX-c. On the other hand, the expression of p53 and pRb was similar for the two lines; hypoxia induced increased expression of p53 and hypophosphorylation of pRb.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brown J. M. Evidence for acutely hypoxic cells in mouse tumours, and a possible mechanism of reoxygenation. Br J Radiol. 1979 Aug;52(620):650–656. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-52-620-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross S. M., Sanchez C. A., Morgan C. A., Schimke M. K., Ramel S., Idzerda R. L., Raskind W. H., Reid B. J. A p53-dependent mouse spindle checkpoint. Science. 1995 Mar 3;267(5202):1353–1356. doi: 10.1126/science.7871434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean P. N., Jett J. H. Mathematical analysis of DNA distributions derived from flow microfluorometry. J Cell Biol. 1974 Feb;60(2):523–527. doi: 10.1083/jcb.60.2.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devonec M. Une nouvelle hypothèse sur l'histoire naturelle du cancer de la vessie grâce à l'étude du contenu en ADN des tumeurs par cytométrie en flux. Ann Urol (Paris) 1987;21(4):250–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doonan J. H., Morris N. R. The bimG gene of Aspergillus nidulans, required for completion of anaphase, encodes a homolog of mammalian phosphoprotein phosphatase 1. Cell. 1989 Jun 16;57(6):987–996. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90337-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeber T. G., Peterson J. F., Tsai M., Monica K., Fornace A. J., Jr, Giaccia A. J. Hypoxia induces accumulation of p53 protein, but activation of a G1-phase checkpoint by low-oxygen conditions is independent of p53 status. Mol Cell Biol. 1994 Sep;14(9):6264–6277. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haapajärvi T., Kivinen L., Pitkänen K., Laiho M. Cell cycle dependent effects of u.v.-radiation on p53 expression and retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation. Oncogene. 1995 Jul 6;11(1):151–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill R. P. Tumor progression: potential role of unstable genomic changes. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1990 Sep;9(2):137–147. doi: 10.1007/BF00046340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intaglietta M., Myers R. R., Gross J. F., Reinhold H. S. Dynamics of microvascular flow in implanted mouse mammary tumours. Bibl Anat. 1977;(15 Pt 1):273–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann W. K., Levedakou E. N., Grady H. L., Paules R. S., Stein G. H. Attenuation of G2 checkpoint function precedes human cell immortalization. Cancer Res. 1995 Jan 1;55(1):7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk C. K., Veinot-Drebot L., Tjan E., Tannock I. F. Effect of transient hypoxia on sensitivity to doxorubicin in human and murine cell lines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990 Apr 18;82(8):684–692. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.8.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkel D. E., McGuire W. L. Ploidy, proliferative activity and prognosis. DNA flow cytometry of solid tumors. Cancer. 1990 Mar 1;65(5):1194–1205. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900301)65:5<1194::aid-cncr2820650528>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell P. C. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science. 1976 Oct 1;194(4260):23–28. doi: 10.1126/science.959840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkura H., Kinoshita N., Miyatani S., Toda T., Yanagida M. The fission yeast dis2+ gene required for chromosome disjoining encodes one of two putative type 1 protein phosphatases. Cell. 1989 Jun 16;57(6):997–1007. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90338-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell S. N., DeFrank J. S., Connell P., Eogan M., Preffer F., Dombkowski D., Tang W., Friend S. Differential sensitivity of p53(-) and p53(+) cells to caffeine-induced radiosensitization and override of G2 delay. Cancer Res. 1995 Apr 15;55(8):1643–1648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice G. C., Hoy C., Schimke R. T. Transient hypoxia enhances the frequency of dihydrofolate reductase gene amplification in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Aug;83(16):5978–5982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.16.5978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rofstad E. K., Wahl A., Hystad M. E., Nesland J. M., Stokke T. Establishment in monolayer culture and characterization of four human melanoma cell lines. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1991;60(3):189–197. doi: 10.1007/BF02899546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna K., Rofstad E. K. Hypoxia-induced resistance to doxorubicin and methotrexate in human melanoma cell lines in vitro. Int J Cancer. 1994 Jul 15;58(2):258–262. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910580219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMLINSON R. H., GRAY L. H. The histological structure of some human lung cancers and the possible implications for radiotherapy. Br J Cancer. 1955 Dec;9(4):539–549. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1955.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H., Staehelin T., Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Sep;76(9):4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vindeløv L. L., Christensen I. J., Nissen N. I. A detergent-trypsin method for the preparation of nuclei for flow cytometric DNA analysis. Cytometry. 1983 Mar;3(5):323–327. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990030503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S. D., Marshall R. S., Hill R. P. Hypoxia induces DNA overreplication and enhances metastatic potential of murine tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Dec;85(24):9533–9537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]