Abstract

The syntrophins are a family of structurally related proteins that contain multiple protein interaction motifs. Syntrophins associate directly with dystrophin, the product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus, and its homologues. We have generated α-syntrophin null mice by targeted gene disruption to test the function of this association. The α-Syn−/− mice show no evidence of myopathy, despite reduced levels of α-dystrobrevin–2. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase, a component of the dystrophin protein complex, is absent from the sarcolemma of the α-Syn−/− mice, even where other syntrophin isoforms are present. α-Syn−/− neuromuscular junctions have undetectable levels of postsynaptic utrophin and reduced levels of acetylcholine receptor and acetylcholinesterase. The mutant junctions have shallow nerve gutters, abnormal distributions of acetylcholine receptors, and postjunctional folds that are generally less organized and have fewer openings to the synaptic cleft than controls. Thus, α-syntrophin has an important role in synapse formation and in the organization of utrophin, acetylcholine receptor, and acetylcholinesterase at the neuromuscular synapse.

Keywords: dystrophin, dystrobrevin, nitric oxide synthase, acetylcholine receptor, acetylcholinesterase

Introduction

Syntrophins are a family of modular, signal transduction proteins that share a common domain structure (Adams et al. 1993; Yang et al. 1994; Ahn et al. 1996; Peters et al. 1997). Each of the three characterized syntrophins contains two pleckstrin homology (PH) domains, a PDZ domain (domain found in postsynaptic density protein-95, discs large, and zonula occludens-1 proteins), and a COOH-terminal syntrophin unique (SU) region. Syntrophins bind directly to members of the dystrophin protein family (dystrophin, utrophin, and dystrobrevin; Ahn and Kunkel 1995; Dwyer and Froehner 1995; Yang et al. 1995), an interaction mediated by the second PH domain and the SU region together (Kachinsky et al. 1999). The first PH domain of α-syntrophin can bind phophotidylinositol lipids, thus providing an additional mode of membrane interaction (Chockalingam et al. 1999). The PDZ domain of syntrophin binds to a variety of signaling molecules, including sodium channels (Gee et al. 1998a; Schultz et al. 1998), neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS; Brenman et al. 1996; Hashida-Okumura et al. 1999; Hillier et al. 1999), and serine/threonine kinases (Hasegawa et al. 1999; Lumeng et al. 1999). Thus, syntrophin links signaling proteins to the actin cytoskeleton and the extracellular matrix via dystrophin.

In skeletal muscle, all three syntrophins are found at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), although in different distributions (Peters et al. 1997; Kramarcy and Sealock 2000). α-Syntrophin is found on both the acetylcholine receptor (AChR)-rich crests and in the bottoms of the postsynaptic folds, where sodium channels are localized (Kramarcy and Sealock 2000). β1-Syntrophin is also concentrated at neuromuscular synapses, but this is in part due to its presence presynaptically. β2-Syntrophin is the isoform most highly localized at the synapse where it is predominantly in the bottoms of the folds (Peters et al. 1997; Kramarcy and Sealock 2000). The syntrophins also differ in their developmental regulation, with α-syntrophin being the first to appear on the postsynaptic membrane (Kramarcy and Sealock 2000). This complex distribution and developmental regulation of the syntrophins suggests that they each play unique roles in synapse formation and maintenance.

Mice rendered deficient in synaptic proteins through targeted gene disruption or other approaches have provided important evidence leading to the current models of neuromuscular synapse formation. Agrin, rapsyn, and a muscle-specific kinase (MuSk) are each essential for neuromuscular synapse formation (Gautum et al. 1995, Gautum et al. 1996; DeChiara et al. 1996). The absence of any of these proteins prevents the formation of nicotinic AChR clusters, leading to death of the mutant mice at birth. In contrast, disruption of TrkB signaling using a dominant-negative approach causes disassembly of mature NMJs (Gonzalez et al. 1999).

Similar studies have identified components of the dystrophin complex and dystrophin homologues as key proteins in synaptic structure. Loss of dystroglycan, which links dystrophin and utrophin to extracellular matrix proteins, such as agrin and laminin, leads to early embryonic death, preventing conventional studies of its role in synapse formation (Williamson et al. 1997). Recently, however, a study of chimeric mice, produced from embryonic stem (ES) cells in which both copies of the dystroglycan gene had been removed, revealed muscle degeneration and abnormalities in the gross structure of the neuromuscular synapse (Cote et al. 1999). Regions of the chimeric mice derived from the dystroglycan null ES cells have NMJs with reduced levels of AChRs, acetylcholinesterase (AChE), and utrophin. Utrophin-null mice are healthy, but have fewer postsynaptic folds and a modest decrease in AChR density (Deconinck et al. 1997; Grady et al. 1997). Finally, mice lacking most forms of α-dystrobrevin display moderate muscle degeneration (Grady et al. 1999) and have structurally abnormal muscle synapses (Grady et al. 2000). AChRs in α-dystrobrevin null myotubes are clustered by agrin, but in contrast to normal myotubes, the clusters disperse soon after agrin removal (Grady et al. 2000). These results provide clear evidence in support of a stabilization or maintenance function for the dystrophin complex at neuromuscular synapses.

Mice lacking α-syntrophin, the predominant form in skeletal muscle, do not have a dystrophic phenotype, but nNOS is absent from the sarcolemma (Kameya et al. 1999). However, effects of α-syntrophin deficiency on neuromuscular synapses have not been examined. In this study of an independently generated α-syntrophin null mouse, we show that the postsynaptic membrane is grossly abnormal and that the level of AChRs and AChE is significantly decreased. Furthermore, nNOS is absent from the postsynaptic membrane and the sarcolemma, despite a significant upregulation of β1- and β2-syntrophin. Perhaps the most surprising result is that expression of utrophin at postsynaptic sites is dependent on the presence of α-syntrophin.

Materials and Methods

Generation of α-Syntrophin Null Mice

Previously, we characterized the gene encoding mouse α-syntrophin using a genomic library derived from 129Sv DNA (Adams et al. 1995). A targeting vector was constructed by cloning a 7.4-kb NotI/XbaI restriction fragment from the region 5′ of exon 1 and a 1.5-kb XbaI fragment from intron 1 into the plasmid JNS2 (Dombrowicz et al. 1993; Fig. 1). The resulting recombinant gene is missing the entire first exon (amino acids 1–97, which encode half of the first PH domain and part of the PDZ domain), 0.8 kb of 5′ flanking sequence, and 1.7 kb of the first intron. The targeting vector was linearized with NotI and transferred to E14 ES cells by electroporation. After selection with G418 and gancyclovir (a gift from Roche Biosciences), homologous recombinant ES cells were identified by Southern blotting (Fig. 1) and used for C57Bl6 blastocyst injection. Injections were performed by the UNC-CH Embryonic Stem Cell Facility. Chimeras were bred with C57Bl6 females and germline transmission was confirmed by Southern blot analysis and PCR (primers: neo-CAAATTAAGGGCCAGCTCATTCCTCC; α-syntrophin first intron-ACAGGAGCCCAGTCTTCAATCCAGG). The mice used in this study were adults >10-wk old and either first generation with a mixed 129Sv/C57Bl6 background or had been bred back against C57Bl6 for 3 generations. Mice with either background show similar phenotypes.

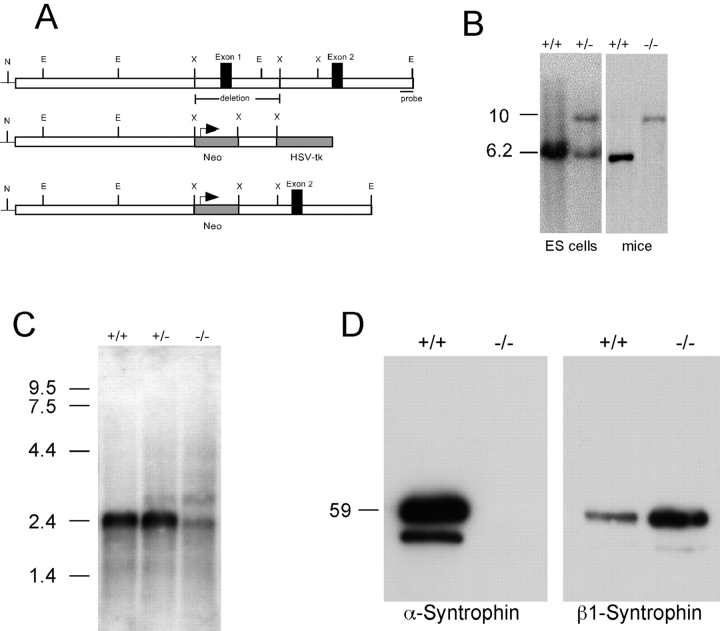

Figure 1.

Generation and characterization of α-syntrophin null mice. A, A targeting vector was constructed using a 7.4-kb Not I (N)/XbaI (X) restriction fragment long arm and a 1.5-kb XbaI fragment short arm. Homologous recombination resulted in the deletion of 2.8-kb of the α-syntrophin gene including all of exon 1. B, Southern blot analysis was performed using genomic DNA (isolated from ES cells or from mice) digested with EcoRI (E). Hybridization using the 500-bp probe shown in A, detected a 6.2-kb wild-type band and a 10-kb recombinant band. C, RNA blot analysis of poly A+ RNA from the mice indicated. The positions of RNA standards are indicated. D, Immunoblot of muscle proteins partially purified with mAb 1351 and detected with α-syntrophin and β1-syntrophin isoform specific antibodies. The position of a 59-kD protein standard is indicated on the left.

Southern Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from ES cells or mouse tail biopsies using a QIAmp tissue kit (Qiagen), digested with EcoRI, and resolved on a 1% agarose gel. GenScreen (NEN Life Science Products) replicas were incubated with radiolabeled probe as described previously (Adams et al. 1995). For RNA blot analysis, adult skeletal muscle RNA was isolated from α-syntrophin wild-type, heterozygous, and syntrophin null mice. Poly A+ RNA was purified (PolyAtract, Promega) and separated on a 1% formaldehyde gel, transferred to GeneScreen, and probed with a 32P-labeled full-length cDNA probe as described (Adams et al. 1993).

Antibodies

Previously, we characterized the following antibodies: pan-specific syntrophin mAb SYN1351 (Froehner et al. 1987); isoform-specific syntrophin Abs SYN17 (α-syntrophin), SYN28 (β2-syntrophin) and SYN37 (β1-syntrophin; Peters et al. 1997); Ab 1862 (utrophin; Kramarcy et al. 1994); Ab 2723 (COOH terminus of dystrophin; Kramarcy et al. 1994); dystrobrevin Abs 638 (α-dystrobrevin–1); and DΒ2 (α-dystrobrevin–2; Peters et al. 1998). The sodium channel Ab was a gift from S. Rock Levinson (University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver, CO). The polyclonal antibody to nNOS was purchased from Diasorin Inc. Antibodies against ankyrin G and synaptophysin were kind gifts of Vann Bennett (Duke University, Durham, NC) and Lian Li (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC), respectively.

Immunoblotting

Muscle protein extracts were prepared as previously described (Peters et al. 1997). Syntrophin complex was isolated by incubating the extract with the pan syntrophin mAb 1351, followed by precipitation with protein G coated beads (Sigma-Aldrich). The resulting pellets were resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, subjected to electrophoresis on a 10% polyacrylamide tricine-buffered gel, transferred to Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore Corp.), and incubated with the syntrophin isoform-specific antibodies SYN17 and SYN37, as previously described (Peters et al. 1997).

Fluorescence Microscopy

Immunofluorescence-labeling of unfixed muscle (see Fig. 2 Fig. 3 Fig. 4 Fig. 5 A) was done on 8-μm cryosections of quadriceps muscle as described (Peters et al. 1997). For high resolution images in Fig. 6, 100 nm sternomastoid muscle sections were prepared as described (Peters et al. 1998; Kramarcy and Sealock 2000). The two labels in Fig. 6 A were biotinylated Con A (Molecular Probes), followed by Alexa 488-streptavidin (all Alexa-conjugated fluophores were obtained from Molecular Probes) and unlabeled α-bungarotoxin (Bgtx), followed by rabbit antitoxin (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and Alexa 594 goat anti–rabbit IgG. The red and green channels in Fig. 6 A were digitally switched to conform to the other images (AChR label in green). The labels in Fig. 6 B were biotinylated Bgtx followed by Alexa 488-streptavidin and rabbit anti–α-dystrobrevin–2 or antiankyrin, followed by Alexa 594 goat anti–rabbit IgG.

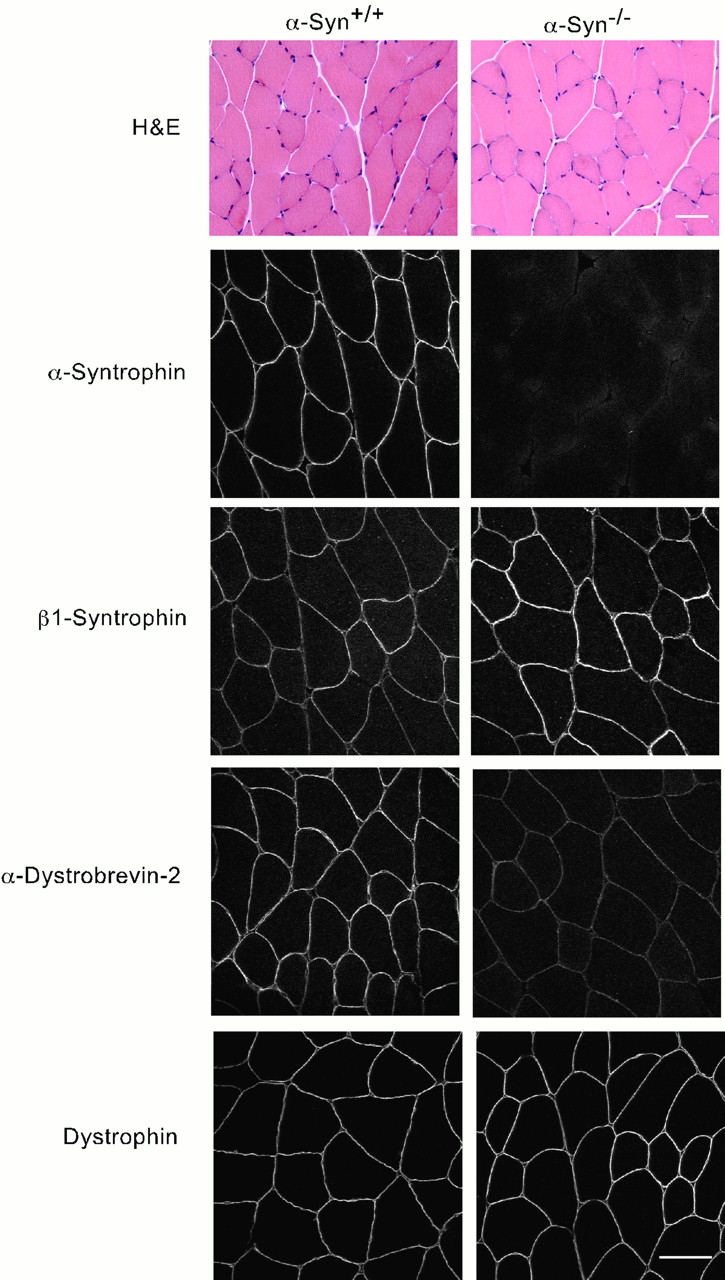

Figure 2.

Analysis of mouse quadriceps muscle. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E, top) stained quadriceps muscle from wild-type (α-Syn+/+) and α-syntrophin null (α-Syn−/−) mice. The bottom panels show immunofluorescence microscopy using the indicated antibody. Bar, 50 μm.

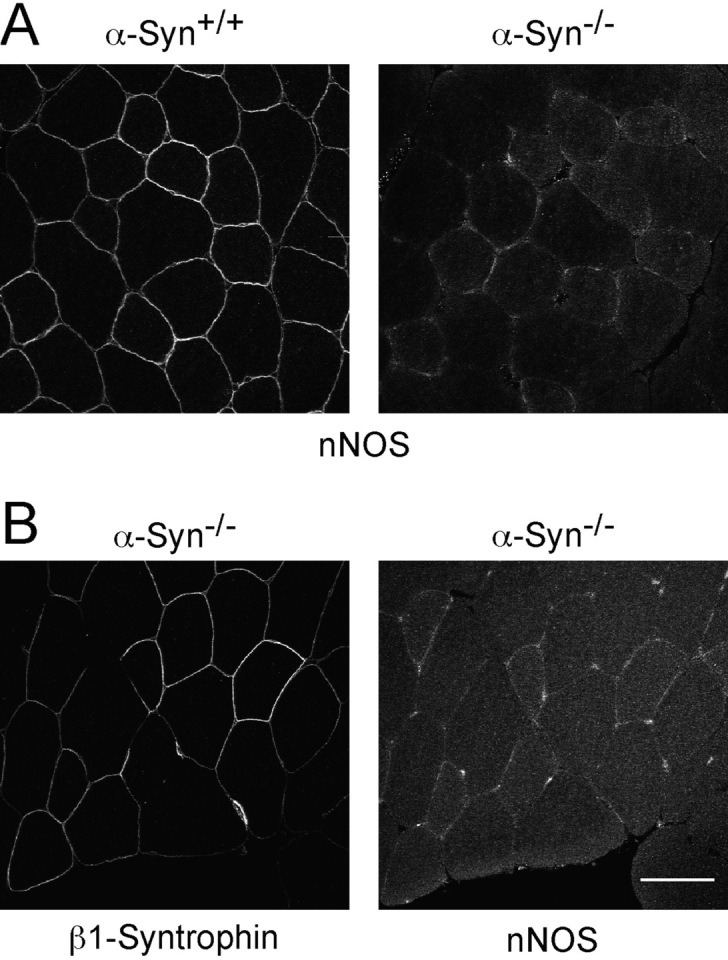

Figure 3.

nNOS distribution in wild-type and α-syntrophin null mouse quadriceps muscle. A, Immunofluorescent labeling of nNOS shows sarcolemmal staining in wild-type that is lost in the α-syntrophin null muscle. B, Immunofluorescence of serial sections of α-syntrophin null muscle shows nNOS is lost from β1-syntrophin containing fibers. Bar, 50 μm.

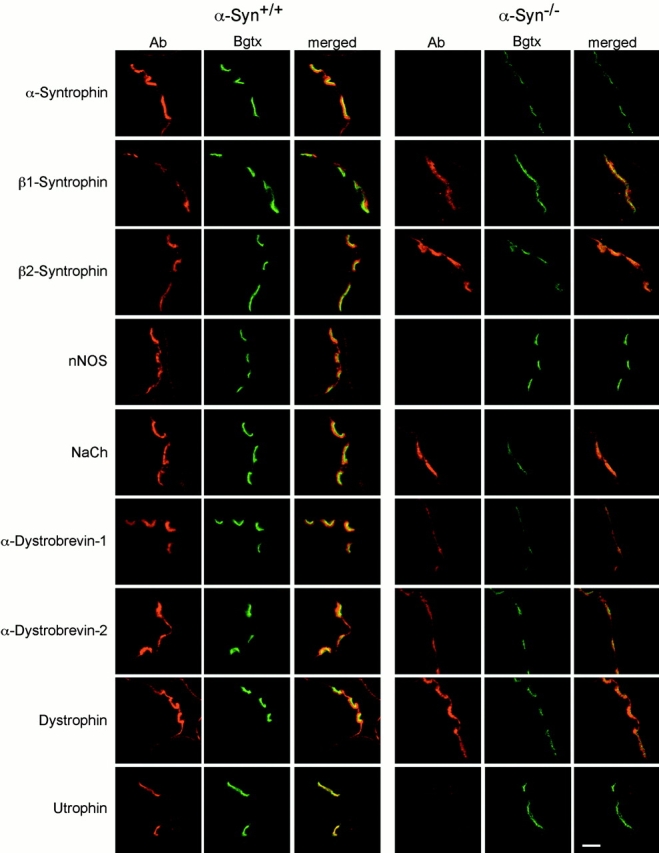

Figure 4.

Distribution of syntrophins and associated proteins at the NMJ. Mouse quadriceps muscle sections were double-labeled with the indicated antibody and bodipy-labeled Bgtx. The two images were combined (merged) to show the relative positions of the indicated proteins and AChRs. All wild-type (α-Syn+/+) and α-syntrophin null (α-Syn−/−) images were collected under identical conditions. Bar, 5 μm.

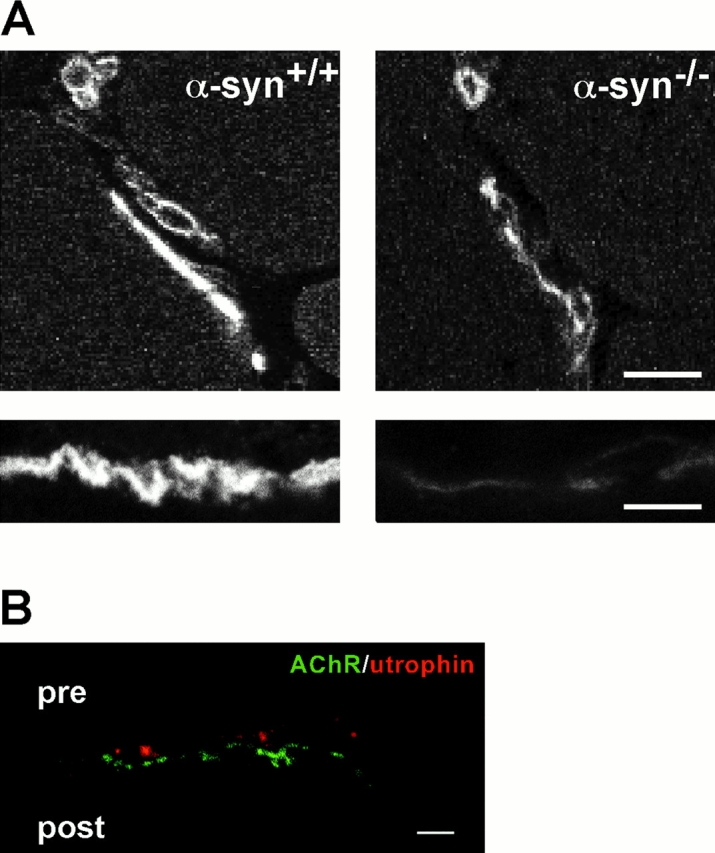

Figure 5.

Loss of utrophin from the α-Syn−/− postsynaptic membrane. A, Mouse quadriceps (8-μm sections) were labeled with antiutrophin antibody. NMJs are intensely labeled in α-Syn+/+ mice and weakly labeled in α-Syn−/− mice, whereas blood vessels are labeled with similar intensity. Bars, 10μm. B, High resolution images of 150-nm sections show that α-Syn−/− NMJ utrophin labeling is largely presynaptic. Bar, 2 μm.

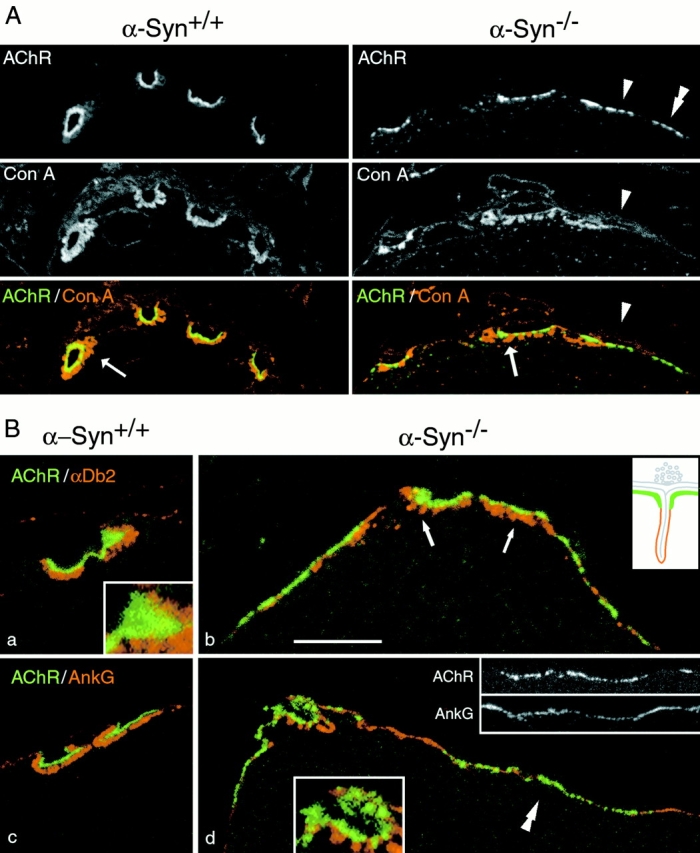

Figure 6.

Distribution of AChR in α-Syn−/− and α -Syn+/+ NMJs. Sternomastoid NMJs from littermate α-Syn−/− and α-Syn+/+ mice were labeled as indicated for AChR, concanavalin A receptors (basal lamina and other extracellular matrix materials), and postsynaptic/sarcolemmal proteins. Inset drawing in B, b, is a schematic of normal junctional folds with the utrophin/AChR-rich membrane in green, the sodium channel/ankyrin-G/dystrophin-rich membrane in red. A, Nerve terminals are unlabeled areas bounded by synaptic gutters and the overlying matrix. Arrow shows a contact with sparse junctional folds. A similar contact lies to the left, and a contact apparently without folds, to the right (arrowhead). AChR is organized in clusters at all three contacts, and clusters of AChR extend beyond nerve-muscle contacts (double arrowhead). B, α-Dystrobrevin-2 was present mainly in the troughs of the junctional folds in α-Syn−/− NMJs (b, arrows), as in wild-type mice (a; see also Peters et al. 1998). Ankyrin G appeared to be present exclusively in the troughs in α-Syn−/− NMJs (d), as in the wild type (c; Flucher and Daniels 1989). Synaptic AChR fields were smooth and continuous in the α-Syn+/+ NMJs (a, inset), but broken into clusters in the α-Syn−/− NMJs (d, color inset). Perisynaptically, these proteins interdigitated with clusters of AChR (grayscale insets). Microscope settings were separately optimized for each image. Bar: (A, α-Syn+/+) 10.6 μm; (A, α-Syn−/−) 8.9 μm; (B, a) 6.3 μm; (B, a, inset) 2.2 μm; (B, b) 6.2 μm; (B, c) 7.2 μm; (B, d) 7.7 μm, (B, d, color inset) 4.0 μm; (B, d, grayscale insets) 10.3 μm.

For en face views (see Fig. 7), thick (40 μm) cryosections were labeled on AChR with Texas red-Bgtx or with toxin/antitoxin as above, with fluorescein-conjugated VVAB4 lectin or biotinylated lectin VVΑ-B4 (Sigma-Aldrich), followed by Alexa-488-streptavidin; and with rabbit antisynaptophysin antibody, followed by Cy5-conjugated donkey anti–rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch). For each NMJ, the final image was obtained by combining 10–15 images taken every 0.3 μm along the z-axis into a single two-dimensional view.

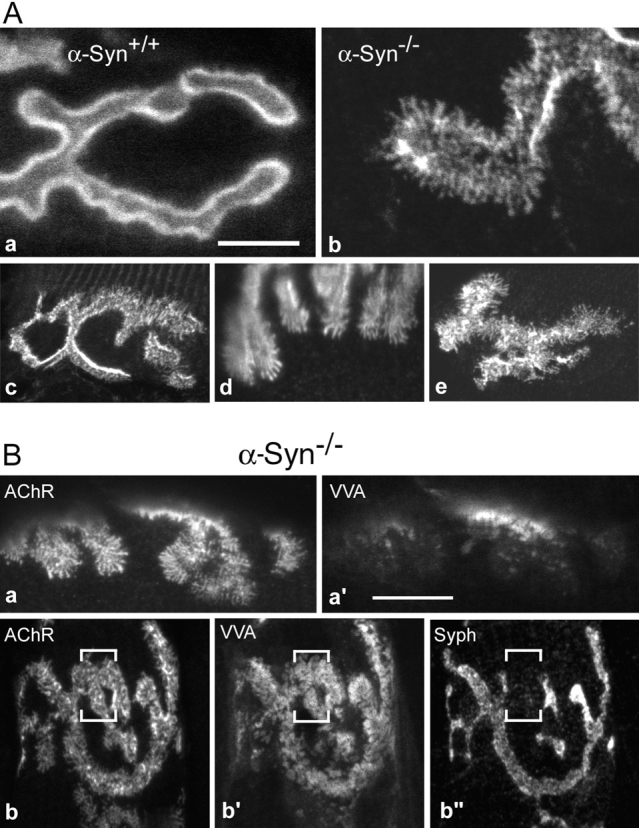

Figure 7.

Global distribution of AChR, folds, and synaptic vesicles within α-Syn−/− NMJs. A, Sternomastoid NMJs from wild-type and α-Syn−/− mice were labeled for AChR and imaged en face. In wild-type NMJs (a), AChR was distributed smoothly throughout the synaptic gutter and the gutter edges appeared bright. In α-Syn−/− NMJs (b–e), AChR in the gutters was distributed in streaks and clusters (b–e) and could even be absent in places (b). The gutter edges often showed little additional intensity, indicating shallow gutters. Most α-Syn−/− NMJs contained lines of AChR extending beyond the gutters (b–e). Some NMJs contained areas of near normal appearance (c), whereas others were abnormal throughout (e). Bar: (a) 5.0 μm; (b) 4.8 μm; (c) 14.7 μm; (d) 11.4 μm; (e) 13.1 μm. B, Sternomastoid NMJs from α-Syn−/− mice were double- or triple-labeled as indicated. Regions of highly altered AChR distribution (a) could be largely devoid of VVA-B4 labeling (a′), suggesting absence of junctional folds. In other NMJs, virtually the entire AChR field (b) was well labeled by VVA-B4 (b′). Regions that gave strong signals for both AChR (b) and junctional folds (b′), which suggests maturity, could nevertheless be devoid of synaptophysin labeling (b′′), suggesting absence of a functional nerve terminal. Bar: (a and a′) 12.1 μm; (b and b′′) 16.1 μm.

AChE was labeled with a fluorescent conjugate (Oregon green) of fasciculin 2, a snake alpha toxin that binds to the catalytic subunit, prepared and imaged as described (Peng et al. 1999).

All other fluorescence microscopy was done using a Leica TCS NT confocal microscope. For Fig. 2 Fig. 3 Fig. 4 Fig. 5 and Fig. 9, all microscope settings for α-Syn+/+ and α-Syn−/− were identical for direct comparison of fluorescence intensity. For Fig. 6 and Fig. 7, microscope settings were adjusted so that α-Syn+/+ and α-Syn−/− samples could be shown at similar intensity.

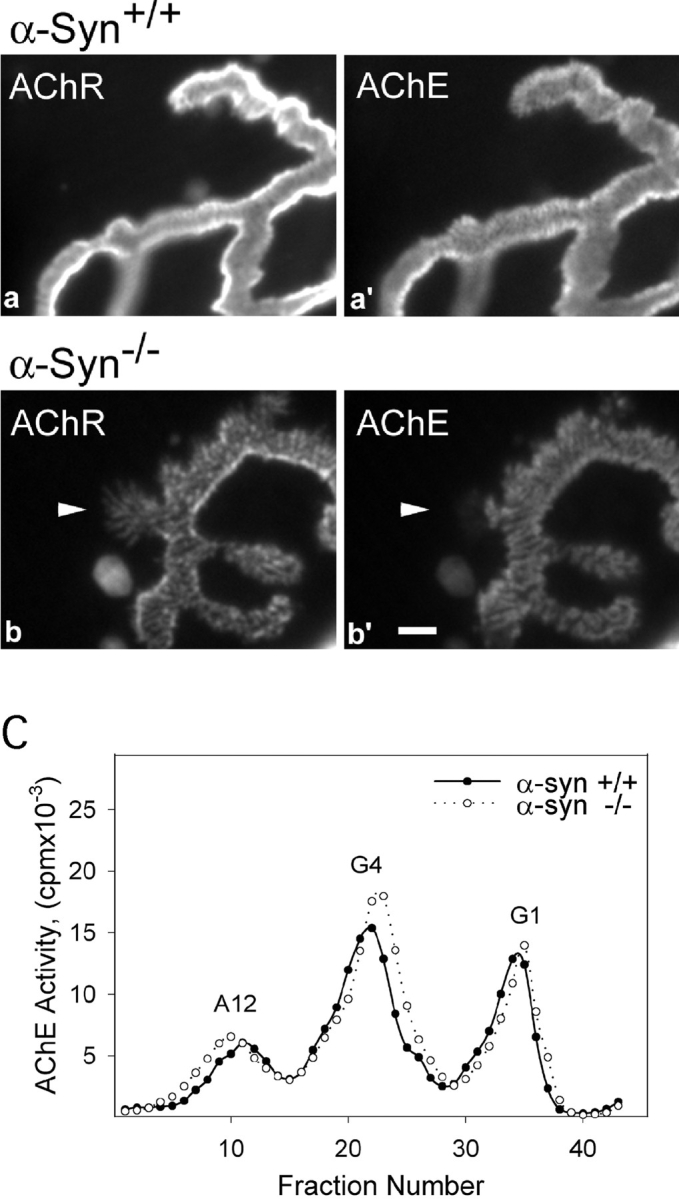

Figure 9.

AChE in wild-type and α-Syn−/− NMJs. Sternomastoid NMJs from wild-type and α-Syn−/− mice were double-labeled for AChR and AChE, and imaged en face under identical microscope settings. The intensities of both labels are substantially reduced in the null NMJs (b and b′) compared with wild-type (a and a′). The AChE distribution in null NMJs shows most of the alterations found in the AChR distributions, except that AChE does not extend into the thin fingers of AChR (arrowhead in b and b′). Bar, 2 μm. C, The muscles from α-Syn−/− mice show no apparent differences in the synthesis and assembly of AChE. The AChE from sternomastoid muscles of α-Syn+/+ and α-Syn−/− mice was extracted and analyzed by velocity sedimentation. G1, Monomeric AChE; G4, tetrameric AChE; A12, synaptic form of AChE consisting of three tetramers attached to a collagen-like tail.

Quantitation of AChR and AChE

To measure relative levels of AChR in NMJs at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, thick cryostat sections (40 μm) of sternomastoid muscles of wild-type and α-syntrophin null mice were labeled with Texas red-Bgtx. NMJs lying fully in the section were imaged in the confocal microscope with the pinhole fully open to eliminate optical sectioning. At the University of Miami, the fixed sternomastoid muscles were labeled for AChR and AChE and teased into single fibers. Images of the NMJs were captured using a digital camera. In both cases, wild-type and α-syntrophin null NMJs were imaged under identical conditions. After circumscribing the digital image of each NMJ using Adobe Photoshop (University of North Carolina) or Metamorph (University of Miami), the difference between the average pixel intensity in the circumscribed area and average background pixel intensity of the corresponding muscle fiber was determined. The product of this difference and the number of circumscribed pixels gave a total AChR- or AChE-specific intensity measure for each NMJ.

For quantitation of AChE enzyme activity, tibialis anterior muscle was homogenized in 10 vol 20 mM borate buffer, pH 9.0, containing 1% Trition X-100, 5 mM EDTA, 1 M NaCl, 0.5% BSA, and a protease inhibitor cocktail as previously described (Rossi and Rotundo 1993). The samples were analyzed by velocity sedimentation on 5–20% sucrose gradients in an SW41 rotor and the fractions assayed for catalytic activity using a radiometric assay.

Electron Microscopy

Sternomastoid muscles were pinned out under fixative (4% glutaraldehyde, 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, pH 7.4), fixed for 2 to 3 h, dissected into junction-containing pieces, incubated in 1% osmium tetroxide, 0.1 M sodium cacodylate for 2 to 3 h, incubated in 3% tannic acid (Mallinckrodt, no. 1764), 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, pH 7.4, for 3 h, and were then embedded in Epon (Simionescu and Simionescu 1976). Silver sections were poststained with uranyl acetate and lead (Sato 1968). The typical ultrathin section through an NMJ contained 2–5 nerve-muscle contacts. All contacts encountered were photographed in only one section, chosen without regard to the characteristics of the contacts. Each contact was analyzed by counting the number of junctional fold openings to the synaptic cleft and dividing by the total length of presynaptic membrane immediately apposed to the muscle cell (openings/μm).

Results

Generation of α-Syn−/− Mice

We established a line of mice lacking α-syntrophin by standard targeted gene disruption methods. The entire first exon (corresponding to amino acids 1–97, which encodes part of the first PH domain and ∼15 amino acids of the PDZ domain), as well as 0.8 kb of 5′ flanking sequence, and 1.7 kb of intron 1 of the α-syntrophin gene were deleted by homologous recombination (Fig. 1). Two ES cell lines were identified by Southern blotting and used for blastocyst injection. One of these lines produced chimeras capable of germline transmission. Subsequent breeding of the heterozygous mice produced offspring in the expected 1:2:1 ratio for wild-type (α-Syn+/+), heterozygotes (α-Syn+/−), and mice with the α-syntrophin gene disrupted on both alleles (α-Syn−/−). Analysis of RNA isolated from skeletal muscle of these mice showed the presence of the expected 2.4-kb transcript (Adams et al. 1993) encoding α-syntrophin in the α-Syn+/+ and α-Syn+/− mice (Fig. 1 C). The α-Syn−/− mice contained low levels of a slightly smaller transcript and a slightly larger transcript, the latter also being present in the α-Syn+/− mice. The top band most likely represents the product of transcription driven by the PGK promoter upstream of the neo gene. The source of the lower band is unknown, but is similar in size and intensity to the 1.9-kb band present in α-Syn−/− mice generated by deletion of exon 2 (Kameya et al. 1999).

To determine if α-syntrophin protein is produced from these transcripts, we immunoprecipitated total syntrophins from skeletal muscle extracts using mAb 1351 (a high affinity, pan-specific antisyntrophin antibody), and then immunoblotted the products using isoform-specific antibodies. mAb SYN1351 recognizes an epitope in exon 2 (the PDZ domain; Adams, M.E., and S.C. Froehner, unpublished results) and would capture NH2-terminal truncated syntrophin potentially expressed by the disrupted gene. The antibody SYN17, produced against a peptide sequence encoded by exon 3 of the α-syntrophin gene (Peters et al. 1994), detected the expected 58-kD protein (syntrophin) in skeletal muscle from the α-Syn+/+ mice, but detected no protein in the muscle from α-Syn−/− mice (Fig. 1 D). In contrast, a blot of identical samples showed that β1-syntrophin levels are moderately increased in skeletal muscle of α-Syn−/− mice.

Characterization of Skeletal Muscle in α-Syn−/− Mice

The α-Syn−/− mice are mobile, reproduce normally, and show no overt signs of muscular dystrophy. We tested their mobility by allowing them to run voluntarily on exercise wheels. The distances run and average speed were statistically indistinguishable from C57Bl6 control mice (data not shown). This result is consistent with the finding that the contractile properties of normal and α-Syn−/− muscles are the same (Kameya et al. 1999). Histologically, the skeletal muscle also appears normal (Fig. 2), with little fibrosis, few centralized nuclei, and a normal size distribution of muscle fibers.

To determine whether elimination of α-syntrophin affected the distribution of other members of the dystrophin protein complex, we examined quadriceps muscles by immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2). As expected, we detected no α-syntrophin staining in this or any other muscle examined. As in wild-type quadriceps muscle (Peters et al. 1997), β1-syntrophin was found in only a subset of fibers in the α-Syn−/− mice. However, in the α-Syn−/− muscle, fibers that do express β1-syntrophin show a modest increase in labeling intensity. This finding is in agreement with the increase found by immunoblotting (Fig. 1). Some muscles, such as the sternomastoid, consist totally of fibers that show no β1-syntrophin staining in the adult (Kramarcy and Sealock 2000). Immunofluorescence of adult α-Syn−/− sternomastoid showed no detectable upregulation of β1-syntrophin (data not shown). In contrast, we observed a decrease in the intensity of sarcolemmal-labeling for α-dystrobrevin–2 in all muscle fibers. The intensity of sarcolemmal dystrophin-labeling in the α-Syn−/− was indistinguishable from littermate control α-Syn+/+ muscle.

Previously, we and others have shown that α-syntrophin binds nNOS in vitro via a PDZ–PDZ interaction (Brenman et al. 1996; Gee et al. 1998a; Hashida-Okumura et al. 1999). Kameya et al. 1999 found that nNOS is no longer concentrated at the sarcolemma in α-Syn−/− mice and we have confirmed that levels of sarcolemmal nNOS are reduced to nearly undetectable amounts (Fig. 3). Interestingly, this loss of nNOS occurs even in those fibers that express sarcolemmal β1-syntrophin (Fig. 3 B). Thus, β1-syntrophin is not able to compensate for the loss of α-syntrophin in recruiting nNOS to the membrane, even though it binds nNOS in vitro (Gee et al. 1998b).

Dystrophin Complex Proteins at Neuromuscular Synapses

α-Syntrophin is present on the sarcolemma, but is enriched at the postsynaptic membrane. We therefore compared the morphology of NMJs from α-Syn+/+ and α-Syn−/− mice. We also studied localization of members of the dystrophin protein complex and signaling proteins associated with the complex at NMJs of the α-Syn−/− mice (Fig. 4). As was the case for sarcolemmal staining, no α-syntrophin was observed at the α-Syn−/− NMJs. Although β1-syntrophin was originally characterized as being enriched at the NMJ, this enrichment has been shown to be due, at least in part, to the presence of β1-syntrophin in presynaptic structures (Peters et al. 1997; Kramarcy and Sealock 2000). At α-Syn−/− synapses, we observed no increase in postsynaptic β1-syntrophin in both fibers expressing and not expressing β1-syntrophin on the sarcolemma. β2-Syntrophin, the isoform that is most tightly confined to the NMJ in adult muscle (Kramarcy and Sealock 2000), appeared to be somewhat upregulated in the α-Syn−/− mice, although this increase was not measured quantitatively. Despite the presence of β2-syntrophin, nNOS is absent from junctions lacking α-syntrophin establishing that β2-syntrophin, like β1-syntrophin, does not recruit nNOS to the membrane to compensate for the loss of α-syntrophin.

α-Syntrophin has also been shown to bind the muscle sodium channels, SkM1 and SkM2, via their COOH-terminal sequences (Gee et al. 1998a; Schultz et al. 1998). Using a polyclonal antibody that recognizes both isoforms, we found that sodium channels remain concentrated at the NMJ and on the perisynaptic membrane of α-Syn−/− muscle, a distribution similar to that found in control muscle. Thus, α-syntrophin is not required for expression or synaptic localization of sodium channels in skeletal muscle.

α-Dystrobrevin shares homology with dystrophin (Wagner et al. 1993; Blake et al. 1996; Sadoulet-Puccio et al. 1996) and is directly associated with it (Peters et al. 1997; Sadoulet-Puccio et al. 1997). Two isoforms, α-dystrobrevin–1 and –2, both bind syntrophin, but are differentially localized in skeletal muscle. α-Dystrobrevin–1 is largely synaptic, whereas α-dystrobrevin–2 is found on both the sarcolemma and at the synapse (Peters et al. 1998). Both α-dystrobrevin–1 and –2 are present at α-Syn−/− synapses, but at slightly lower levels than wild-type synapses.

The distribution of dystrophin (Byers et al. 1991; Sealock et al. 1991) appears unaltered at the α-Syn−/− junction, remaining concentrated in the postjunctional folds in the absence of α-syntrophin (Fig. 4). However, utrophin staining, which is normally at the crests of the folds (Bewick et al. 1992) and at much lower levels on presynaptic elements, is dramatically reduced in the postsynaptic membrane of the α-Syn−/− mice. Images of 8-μm sections show low levels of utrophin at the α-Syn−/− NMJ (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 A), but at high resolution (see Materials and Methods), even when the confocal microscope is adjusted to give a strong image of the weak presynaptic staining, utrophin is essentially undetectable on the postsynaptic membrane (Fig. 5 B). Thus, full expression and/or localization of utrophin at the postsynaptic membrane is dependent on the presence of α-syntrophin.

AChR Levels at Mutant Neuromuscular Synapses

During the immunofluorescent studies, we consistently observed that the levels of AChR were much lower in the junctions of α-syntrophin null mice than in the wild-type mice. Therefore, we measured total levels of AChR in NMJs of sternomastoid muscle from two α-Syn−/− and two α-Syn+/+ mice from a single litter and pooled the data. Analyses were performed independently in two separate laboratories (see Materials and Methods). Data collected from 70 wild-type and 92 α-syntrophin null junctions indicated that the average AChR content per NMJ in the null mice was reduced 60% (University of Miami lab) and 67% (University of North Carolina lab) compared with the wild-type junctions. The AChR content of the null junctions was thus only ∼35% of wild-type. This difference was highly significant by the two-tailed t test (P < 0.0001) for each of the two data sets.

Structure of Mutant Neuromuscular Synapses

The structure of α-Syn−/− NMJs was assessed at high resolution by double-labeling muscle sections with Bgtx and concanavalin A. The lectin labels extracellular glycoproteins throughout muscle tissue, particularly highlighting the synaptic cleft and junctional folds. It also labels the material overlying junctional nerve terminals, but not the terminals themselves. Wild-type NMJs are characterized by deep synaptic gutters, plentiful junctional folds, and an AChR distribution that is continuous, bright, and tightly confined to the gutters (Fig. 6 A, left, B, a and c). In contrast, nerve-muscle contacts in α-Syn−/− mice often had shallow gutters, fewer folds, synaptic AChRs separated into distinct clusters, and perisynaptic clusters of AChR (i.e., clusters that extended beyond recognizable nerve–muscle contacts; Fig. 6 A, right, and B, b and d). Proteins that normally occur perisynaptically and in the troughs of the junctional folds, such as α-dystrobrevin–2 (Fig. 6 B, a and b), ankyrin G (Fig. 6 B, c and d), β2-syntrophin (Fig. 4), and dystrophin (Fig. 4) retained these distributions in α-Syn−/− muscle (Fig. 6 B, b and d). The perisynaptic distribution of ankyrin G did not overlap, but rather interdigitated with, the perisynaptic clusters of AChR (readily seen in grayscale insets in Fig. 6 B, d).

To further characterize the AChR distribution, NMJs were visualized en face after labeling with Bgtx. In α-Syn+/+ NMJs, the AChR labeling was consistently smooth, continuous, and confined to the synaptic gutters (part of an NMJ is shown in Fig. 7 A, a). The edges of the gutters, which turn up parallel to the axis of the microscope in such samples, were intensely bright. In contrast, the α-Syn−/− NMJs were highly variable, even within single synapses. In the more extreme derangements (Fig. 7 A, b), the AChR pattern in synaptic gutters consisted of streaks and dots, while thin lines of AChR ∼1 μm in length extended beyond the gutters (see examples in Fig. 7 A). The edges of gutters were often little brighter that the center (Fig. 7A, Fig. b), consistent with the shallow gutters seen in cross-section. Some NMJs contained these features over their whole extent (Fig. 7 A, e), whereas others contained areas of aberrant AChR pattern next to areas of more normal appearance (Fig. 7 A, c).

To assess the presence of nerve terminals and junctional folds in regions of aberrant AChR distribution, sections were labeled with an antibody against the synaptic vesicle protein synaptophysin and with fluorophore-conjugated lectin, VVΑ-B4. This lectin labels only the NMJ in muscle (Scott et al. 1988), with much stronger labeling in the troughs of the folds than on the AChR-rich crests (Kramarcy, N., and R. Sealock, unpublished), thereby providing a measure of the extent of junctional folding. In α-Syn−/− NMJs, major areas of membrane containing AChR either were labeled weakly or not at all by VVA-B4 (Fig. 7 B, a and a′), suggesting the absence of junctional folds. Other areas were strongly stained (Fig. 7 B, b and b′). Interestingly, even areas that had folds, indicative of morphological maturity, could be devoid of labeling by antisynaptophysin (Fig. 7 B, b and b′′), suggesting the absence of a functional nerve terminal and making participation in synaptic transmission unlikely. This was a local phenomenon within NMJs, as the major portions of all α-Syn−/− NMJs labeled positive for synaptophysin (Fig. 7 B, b′′). These results contrast with α-Syn+/+ junctions, in which essentially the entire AChR-rich area was labeled by VVA-B4 and by antisynaptophysin (not shown).

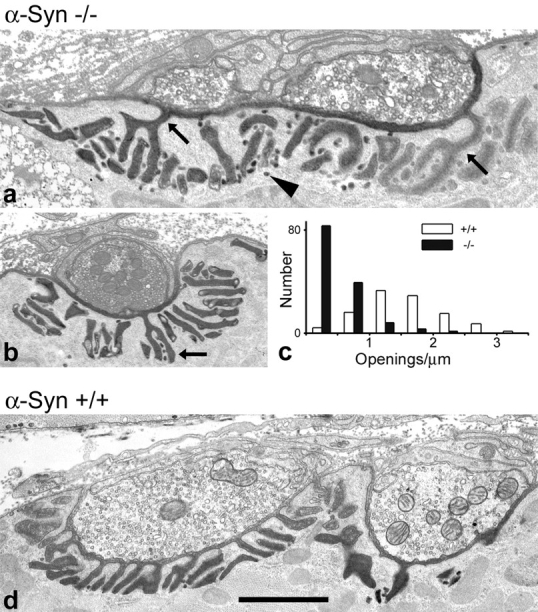

Ultrastructural Analysis

Sternomastoid muscles from one pair of α-Syn+/+ and α-Syn−/− littermates from each of two separate litters were examined by EM. After fixation and osmication, the muscles were treated with tannic acid to enhance heavy metal staining of extracellular elements, notably the basal lamina of the synaptic cleft and junctional folds. Examination was restricted to recognizable nerve–muscle contacts, i.e., sites at which nerve terminals were closely apposed to muscle cells. Presynaptic elements (nerve terminals and overlying Schwann cells) appeared normal in all samples.

EM revealed two main abnormalities in the postsynaptic membrane of α-Syn−/− NMJs. First, the number of junctional fold openings to the synaptic cleft was substantially reduced compared with α-Syn+/+ mice. Even where the folds were plentiful and oriented toward the synaptic cleft, the number that actually opened to the cleft was reduced (compare Fig. 8, a and b, with d). Quantitatively, the number of openings per micrometer of presynaptic membrane was reduced 59 and 77% in two α-Syn−/− mice from different litters, each compared with an α-Syn+/+ littermate. The pooled data are shown graphically in Fig. 8 c. In both pairs, the difference was highly significant (P < 0.0001; t test).

Figure 8.

Ultrastructural analysis of α-Syn−/− NMJs. Nerve-muscle contacts in null (a and b) and wild-type (d) sternomastoid muscles treated with tannic acid to highlight synaptic clefts and junctional folds (synaptic basal lamina). Folds in α-Syn−/− NMJs varied from near normal in appearance (straight, oriented toward the membrane; b) to moderately deranged (curved elements, short folds, folds parallel to the membrane; a). The number of junctional fold openings to the synaptic cleft was reduced in α-Syn−/− NMJs. Arrows in a and b indicate the only folds that open to the cleft in the views shown. In contrast, 12 such folds are apparent in the view of the wild-type NMJ (d). Pooled data for junctional fold openings per micrometer of presynaptic membrane in wild-type and null NMJs are shown in c. The small vesicle-like structures (arrowhead in a), which appear to be caveoli budding from the junctional folds, were plentiful in all NMJs, although few are present in the α-Syn+/+ image shown here (d). Bar: (a) 1.1 μm; (b) 1.5 μm; (d) 1.4 μm.

Secondly, the junctional folds in α-Syn−/− mice generally appeared to be less well organized than in α-Syn+/+ mice. This most often consisted of curved elements, short folds, and folds that ran parallel to the surface membrane (Fig. 8). Direct morphological examination showed that all these structures contained basal lamina, presumably indicating that they open to the surface at some point.

AChE in Mutant Neuromuscular Synapses

Despite the fact that the NMJs in α-Syn−/− mice are structurally abnormal and contain low levels of AChRs, the mutant mice show no deficiencies in mobility as assessed by voluntary running wheel experiments (see above). We considered the possibility that a compensatory change occurs in the mutant junction such that synaptic transmission is still effective. A possible candidate for compensation is AChE, which, if reduced at mutant NMJs, would enhance ACh efficacy. We therefore investigated the distributions and levels of AChE at junctions of α-Syn−/− mice. Bundles of sternomastoid muscle fibers from two normal and two mutant mice were labeled with fluorescently tagged fasciculin 2 (a toxin that specifically labels AChE; Peng et al. 1999), and then imaged as described in Materials and Methods. The distribution of AChE is altered in muscle lacking α-syntrophin and in general appears much like that of AChR (Fig. 9). Areas of AChR distribution that consisted entirely of fingers did not label for AChE (Fig. 9b and Fig. b′, arrowhead), as would be expected from the absence of folds in such areas (Fig. 7 B). Measurement of the levels of AChE in 24 junctions showed a significant reduction of 55% (P < 0.02) in the α-Syn−/− NMJs. Thus, AChRs and AChE are reduced by similar amounts in muscles of the α-Syn−/− mice.

The reduction in AChE could occur by either a defect in synthesis or in localization and retention at the synapse. To discern between these two mechanisms, we compared the total amount and isoform distribution of AChE in normal and mutant mice by sucrose gradient analysis (Rossi and Rotundo 1993). The total amount of soluble, catalytically active AChE, as well as the relative amounts of the monomeric (G1), tetrameric (G4), and collagen-tailed synaptic (A12) forms were indistinguishable between α-Syn+/+ and α-Syn−/− samples (Fig. 9 C). AChE analyzed by this method is derived largely from the cytosol, the Golgi, and the rough ER, and represents the pool available for export to the surface. Synaptic AChE is not solubilized by this method. The results suggest that the absence of α-syntrophin has no detectable effect on synthesis, assembly, or availability of the AChE forms in muscle. Thus, the abnormality must lie in localization and/or retention of the enzyme at the synapse.

Discussion

Syntrophins are thought to function by recruiting signaling proteins to the dystrophin/utrophin protein complex. We investigated the function of α-syntrophin using targeted gene disruption to delete the first exon of the α-syntrophin gene, thereby generating mice lacking α-syntrophin. Tissue immunofluorescence and protein blot analyses demonstrate that these mice do not produce α-syntrophin. Despite the loss of α-syntrophin, these mice are mobile, fertile, and show no signs of a dystrophic phenotype. These observations are consistent with those of Kameya et al. 1999 who have reported an α-syntrophin null mouse generated by deleting exon 2. A weak band hybridizing to the α-syntrophin cDNA is present on Northern blots of α-Syn−/− muscle RNA performed by us and by Kameya et al. 1999. This may represent a form of α-syntrophin produced by an alternative promoter that would presumably have to be located downstream of exon 3, since our SYN17 antibody is made to an epitope encoded by exon 3, but detects no protein. Alternatively, since β2-syntrophin can be encoded by a 10-, 5-, or 2-kb mRNA (Adams et al. 1993), it is possible that this band is a result of cross-hybridization to the 2-kb β2-syntrophin message.

In previous work, we and others have shown that α-syntrophin binds nNOS via a PDZ–PDZ interaction, thus providing a role for the dystrophin complex in targeting this signaling protein to the membrane. In agreement with Kameya et al. 1999, nNOS is absent from the sarcolemma of our mice lacking α-syntrophin. This defect occurs even in fibers that contain abnormally high amounts of β1-syntrophin, and at the NMJ where β2-syntrophin is concentrated. Thus, despite the highly conserved sequences of syntrophin PDZ domains, only α-syntrophin is able to bind nNOS PDZ in vivo. Sarcolemmal nNOS is important for maintenance of adequate blood flow to exercising muscles by counteracting adrenergically mediated vasoconstriction (Thomas et al. 1998). α-Syn−/− mice are not detectably impaired in their ability to exercise, since they run voluntarily for similar times and distances as controls. However, the voluntary exercise test may not reveal abnormalities in this system. Experiments examining adrenergic mediation of vasoconstriction in mice lacking α-syntrophin are underway.

The absence of α-syntrophin selectively affects the expression of other members of the dystrophin protein complex, although dystrophin itself appears to be unaltered. The levels of β1-syntrophin (in some fibers) and β2-syntrophin are increased at the sarcolemma and the NMJ, respectively. Despite the increase in β1-syntrophin, α-dystrobrevin–2 levels are significantly reduced on the α-Syn−/− sarcolemma. The reduced levels of α-dystrobrevin–2 are not sufficient, however, to induce the mild dystrophy seen in the α-dystrobrevin null mice (Grady et al. 1999). The most dramatic change observed in the α-Syn−/− mouse is the loss of utrophin from the postsynaptic membrane. This loss occurs despite the increased levels of β2-syntrophin at the NMJ. This is surprising since β2- and α-syntrophin have similar ability to bind utrophin in vitro (Ahn and Kunkel 1995) and β2-syntrophin is the isoform that is colocalized with utrophin in many nonmuscle tissues (Kachinsky et al. 1999). Thus, β2-syntrophin must perform a different synaptic role than α-syntrophin in vivo. These alterations suggest that α-syntrophin is a crucial component having unique activities in forming and/or maintaining the dystrophin protein complex.

The unexpected loss of utrophin from the α-Syn−/− NMJs could arise by either a structural or signaling mechanism. Utrophin, like dystrophin, is thought to be bound to the membrane primarily through interactions with β-dystroglycan. α-Syntrophin may stabilize these protein interactions, provide a second site of protein interaction, or potentially bind directly with phospholipids in the membrane (Chockalingam et al. 1999). A more intriguing possibility is that α-syntrophin is part of a signaling pathway that regulates the synaptic expression of utrophin. The recent observation that the receptor-tyrosine kinase, ErbB4, is associated via its COOH-terminal tail with the PDZ domain of syntrophins (Garcia et al. 2000; Huang et al. 2000) is particularly noteworthy since ErbB ligands upregulate the expression of utrophin (Gramolini et al. 1999; Khurana et al. 1999). Further studies of the function of α-syntrophin may bolster efforts to design a therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy based on upregulation of utrophin as a substitute for dystrophin.

The alterations seen at neuromuscular synapses of mice lacking α-syntrophin are similar to changes in other genetically altered mice. Like the utrophin null mice (Deconinck et al. 1997; Grady et al. 1997), the α-Syn−/− mice show reduced levels of AChR, fewer postjunctional fold openings, and no dystrophic muscle properties. Thus, some of the alterations seen in the α-Syn−/− mouse could be due to the loss of utrophin. However, the reduction in AChR levels is larger in α-Syn−/− muscle than in muscle lacking utrophin, indicating that additional factors must be involved. AChR number at the postsynaptic membrane could be regulated in several different ways, including synthesis, targeting and degradation. The recent observation that AChR in mdx muscle are less stable than in normal muscle suggests a role for the dystrophin complex in maintaining receptor stability (Xu and Salpeter 1997).

En face views of the α-Syn−/− NMJ are remarkably similar to those seen in the α-dystrobrevin–null mouse (Grady et al. 2000). These junctions have shallow nerve terminal gutters and an abnormal pattern of AChR distribution within and beyond synaptic gutters. These synaptic alterations in the α-dystrobrevin mutant may be secondary to the partial loss of α-syntrophin observed in these mice. However, the α-dystrobrevin null mouse suffers from a moderate level of dystrophy (Grady et al. 1999), suggesting there are additional alterations in α-dystrobrevin function in muscle that do not occur in the α-Syn−/− mice. Agrin induces AChR clusters on cultured myotubes lacking α-dystrobrevin, but the clusters are unstable and disperse after removal of agrin. Similar results are obtained with myotubes lacking α-dystroglycan (Grady et al. 2000). These findings, along with the observation that NMJs in chimeric muscle lacking α-dystroglycan are structurally abnormal and contain low levels of AChR and other synaptic proteins (Cote et al. 1999), indicate that the dystrophin complex plays an important role in synaptic stabilization. Our findings suggest that α-syntrophin may be especially important in the mechanisms by which stabilization occurs.

Severe reduction in AChR levels at the NMJ, due to acquired autoimmunity or congenital causes, leads to myasthenia gravis, a muscle weakness disease (reviewed in Lindstrom 1997). Here, we have shown that α-Syn−/− mice unexpectedly show reductions in total AChR levels to about one-third of normal. This raises the possibility that α-syntrophin mutations could be the primary defect in cases of congenital myasthenia in humans in which the AChR genes are normal. Interestingly, two candidate kinships have been described that have NMJs which lack utrophin and show reduced numbers of AChRs like the α-Syn−/− mouse (Sieb et al. 1998). The α-Syn−/− mice, however, do not show overt signs of myasthenia. It may be that this level of reduction is not sufficient to nullify the large safety factor at the normal NMJ (Wood and Slater 1997). In addition, we have identified one probable compensating factor, the reduction of AChE levels to about one-half of normal. The mechanism leading to the reduction of AChR and AChE in the absence of syntrophin will be the focus of future study.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Rock Levinson for providing sodium channel antibody, Vann Bennett for ankyrin G antibody, and Lian Li for synaptophysin antibody. We also thank Kirk McNaughton for providing histological samples, L. Gretta Gray for genotyping assistance, and our colleagues for helpful discussions.

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health grants NS33145 (to S.C. Froehner and R. Sealock) and AG05917 (to R.L. Rotundo), and grants from the Council for Tobacco Research and the Muscular Dystrophy Association (to R.L. Rotundo and R. Sealock).

Footnotes

Current address for Marvin E. Adams and Stanley C. Froehner is Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Box 357290, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-7290.

Abbreviations used in this paper: AChE, acetylcholinesterase; AChR, acetylcholine receptor; Bgtx, α-bungarotoxin; ES, embryonic stem; NMJ, neuromuscular junction; nNOS, neuronal nitric oxide synthase; PDZ, domain found in postsynaptic density protein-95, discs large, and zonula occludens-1 proteins; PH, pleckstrin homology.

References

- Adams M.E., Butler M.H., Dwyer T.M., Peters M.F., Murnane A.A., Froehner S.C. Two forms of mouse syntrophin, a 58 kd dystrophin-associated protein, differ in primary structure and tissue distribution. Neuron. 1993;11:531–540. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90157-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams M.E., Dwyer T.M., Dowler L.L., White R.A., Froehner S.C. Mouse alpha 1- and beta 2-syntrophin gene structure, chromosome localization, and homology with a discs large domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:25859–25865. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn A.H., Kunkel L.M. Syntrophin binds to an alternatively spliced exon of dystrophin. J. Cell Biol. 1995;128:363–371. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.3.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn A.H., Freener C.A., Gussoni E., Yoshida M., Ozawa E., Kunkel L.M. The three human syntrophin genes are expressed in diverse tissues, have distinct chromosomal locations, and each bind to dystrophin and its relatives. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:2724–2730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewick G.S., Nicholson L.V.B., Young C., O'Donnell E., Slater C.R. Different distributions of dystrophin and related proteins at nerve-muscle junctions. Neuro. Report. 1992;3:857–860. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199210000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake D.J., Nawrotzki R., Peters M.F., Froehner S.C., Davies K.E. Isoform diversity of dystrobrevin, the murine 87-kDa postsynaptic protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:7802–7810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenman J.E., Chao D.S., Gee S.H., McGee A.W., Craven S.E., Santillano D.R., Wu Z., Huang F., Xia H., Peters M.F. Interaction of nitric oxide synthase with the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95 and alpha1-syntrophin mediated by PDZ domains. Cell. 1996;84:757–767. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers T.J., Kunkel L.M., Watkins S.C. The subcellular distribution of dystrophin in mouse skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle. J. Cell Biol. 1991;115:411–421. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.2.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chockalingam P.S., Gee S.H., Jarrett H.W. Pleckstrin homology domain 1 of mouse alpha1-syntrophin binds phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Biochemistry. 1999;38:5596–5602. doi: 10.1021/bi982564+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote P.D., Moukhles H., Lindenbaum M., Carbonetto S. Chimeric mice deficient in dystroglycans develop muscular dystrophy and have disrupted myoneural synapses. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:338–342. doi: 10.1038/15519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeChiara T.M., Bowen D.C., Valenzuela D.M., Simmons M.V., Poueymirou W.T., Thomas S., Kinetz E., Compton D.L., Rojas E., Park J.S. The receptor tyrosine kinase MuSk is required for neuromuscular junction formation in vivo. Cell. 1996;85:501–512. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deconinck A.E., Potter A.C., Tinsley J.M., Wood S.J., Vater R., Young C., Metzinger L., Vincent A., Slater C.R., Davies K.E. Postsynaptic abnormalities at the neuromuscular junctions of utrophin-deficient mice. J. Cell Biol. 1997;136:883–894. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.4.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowicz D., Flamand V., Brigman K.K., Koller B.H., Kinet J.-P. Abolition of anaphylaxis by targeted gene disruption of the high affinity immunoglobulin E receptor alpha chain gene. Cell. 1993;75:969–976. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90540-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer T.M., Froehner S.C. Direct binding of Torpedo syntrophin to dystrophin and the 87 kDa dystrophin homologue. FEBS Letters. 1995;375:91–94. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01176-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flucher B.E., Daniels M.P. Distribution of sodium channels and ankyrin in the neuromuscular junction is complementary to that of acetylcholine receptors and the 43kD protein. Neuron. 1989;3:163–175. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehner S.C., Murnane A.A., Tobler M., Peng H.B., Sealock R. A postsynaptic Mr 58,000 (58K) protein concentrated at acetylcholine receptor-rich sites in Torpedo electroplaques and skeletal muscle. J. Cell Biol. 1987;104:1633–1646. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.6.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia R.A., Vasudevan K., Buonanno A. The neuregulin receptor ErbB4 interacts with PDZ-containing proteins at synapses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:3596–3601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070042497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautum M., Noakes P.G., Mudd J., Nichol M., Chu G.C., Sanes J.R., Merlie J.P. Failure of postsynaptic specialization to develop at neuromuscular junctions of rapsyn-deficient mice. Nature. 1995;377:232–236. doi: 10.1038/377232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautum M., Noakes P.G., Moscoso L., Rupp F., Scheller R.H., Merlie J.P., Sanes J. Defective neuromuscular synaptogenesis in agrin-deficient mutant mice. Cell. 1996;85:525–535. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee S.H., Madhavan R., Levinson S.R., Caldwell J.H., Sealock R., Froehner S.C. Interaction of muscle and brain sodium channels with multiple members of the syntrophin family of dystrophin-associated proteins J. Neurosci. 18 1998. 128 137a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee S.H., Sekely S.A., Lombardo C., Kurakin A., Froehner S.C., Kay B.K. Cyclic peptides as non-carboxy-terminal ligands of syntrophin PDZ domains J. Biol. Chem. 273 1998. 21980 21987b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez M., Ruggiero F.P., Chang Q., Shi Y.J., Rich M.M., Kraner S., Balice-Gordon R.J. Disruption of TrkB-mediated signaling induces disassembly of postsynaptic receptor clusters at neuromuscular junctions. Neuron. 1999;24:567–583. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady R.M., Merlie J.P., Sanes J.R. Subtle neuromuscular defects in utrophin-deficient mice. J. Cell Biol. 1997;136:871–882. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.4.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady R.M., Grange R.W., Lau K.S., Maimone M.M., Nichol M.C., Stull J.T., Sanes J.R. Role for alpha-dystrobrevin in the pathogenesis of dystrophin-dependent muscular dystrophies. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:215–220. doi: 10.1038/12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady R.M., Zhou H., Cunningham J.M., Henry M.D., Campbell K.P., Sanes J.R. Maturation and maintenance of the neuromuscular synapsegenetic evidence for roles of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex. Neuron. 2000;25:275–293. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80894-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramolini A.O., Angus L.M., Schaeffer L., Burton E.A., Tinsley J.M., Davies K.E., Changeux J.-P., Jasmin B.J. Induction of utrophin gene expression by heregulin in skeletal muscle cellsrole of the N-box motif and GA binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:3223–3227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M., Cuenda A., Spillantini M.G., Thomas G.M., Buee-Scherrer V., Cohen P., Goedert M. Stress-activated protein kinase-3 interacts with the PDZ domain of alpha1-syntrophin. A mechanism for specific substrate recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:12626–12631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashida-Okumura A., Okumura N., Iwamatsu A., Buijs R.M., Romijn H.J., Nagai K. Interaction of neuronal nitric oxide synthase with alpha1-syntrophin in rat brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:11736–11741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier B.J., Christopherson K.S., Prehoda K.E., Bredt D.S., Lim W.A. Unexpected modes of PDZ scaffolding revealed by structure of nNOS-syntrophin complex. Science. 1999;284:812–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.Z., Won S., Ali D.W., Wang Q., Tanowitz M., Du Q.S., Pelkey K.A., Yang D.J., Xiong W.C., Salter M.W., Mei L. Regulation of neuregulin signaling by PSD-95 interacting with ErbB4 at CNS synapses. Neuron. 2000;26:443–455. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachinsky A.M., Froehner S.C., Milgram S.L. A PDZ-containing scaffold related to the dystrophin complex at the basolateral membrane of epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 1999;145:391–402. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameya S., Miyagoe Y., Nonaka I., Ikemoto T., Endo M., Hanaoka K., Nabeshima Y., Takeda S. Alpha-syntrophin gene disruption results in the absence of neuronal-type nitric oxide synthase at the sarcolemma but does not induce muscle degeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:2193–2200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana T.S., Rosmarin A.G., Shang J., Krag T.O.B., Das S., Gammeltoft S. Activation of utrophin promoter by heregulin via the ets-related transcription factor complex GA-binding protein alpha/beta. Mol. Biol.Cell. 1999;10:2075–2086. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.6.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramarcy N.R., Sealock R. Syntrophin isoforms at the neuromuscular junctiondevelopmental time course and differential localization. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2000;15:262–274. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramarcy N.R., Vidal A., Froehner S.C., Sealock R. Association of utrophin and multiple dystrophin short forms with the mammalian M(r) 58,000 dystrophin-associated protein (syntrophin) J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:2870–2876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom J. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in health and disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 1997;15:193–222. doi: 10.1007/BF02740634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumeng C., Phelps S., Crawford G.E., Walden P.D., Barald K., Chamberlain J.S. Interactions between beta2-syntrophin and a family of microtubule-associated serine/threonine kinases. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2:611–617. doi: 10.1038/10165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H.B., Xie H., Rossi S.G., Rotundo R.L. Acetylcholinesterase clustering at the neuromuscular junction involves perlecan and dystroglycan. J. Cell Biol. 1999;145:911–921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters M.F., Kramarcy N.R., Sealock R., Froehner S.C. β2-Syntrophinlocalization at the neuromuscular junction in skeletal muscle. Neuro. Report. 1994;5:1577–1580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters M.F., Adams M.E., Froehner S.C. Differential association of syntrophin pairs with the dystrophin complex. J. Cell Biol. 1997;138:81–93. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters M.F., Sadoulet-Puccio H., Grady R.M., Kramarcy N.R., Kunkel L.M., Sanes J.R., Sealock R., Froehner S.C. Differential membrane localization and intermolecular associations of alpha-dystrobrevin isoforms in skeletal muscle. J. Cell Biol. 1998;142:1269–1278. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.5.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi S.R., Rotundo R.L. Localization of non-extractable acetylcholinesterase to the vertebrate neuromuscular junction. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:19152–19159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadoulet-Puccio H.M., Khurana T.S., Cohen J.B., Kunkel L.M. Cloning and characterization of the human homologue of a dystrophin related phosphoprotein found at the Torpedo electric organ post-synaptic membrane. Hum. Mol. Gen. 1996;5:489–496. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.4.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadoulet-Puccio H.M., Rajala M., Kunkel L.M. Dystrobrevin and dystrophinan interaction through coiled-coil motifs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:12413–12418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T. A modified method for lead staining of thin sections. Jap. J. Elect. Microsc. 1968;17:158–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J., Hoffmuller U., Krause G., Ashurst J., Macias M.J., Schmieder P., Schneider-Mergener J., Oschkinat H. Specific interactions between the syntrophin PDZ domain and voltage-gated sodium channels. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998;5:19–24. doi: 10.1038/nsb0198-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott L.J., Bacou F., Sanes J.R. A synapse-specific carbohydrate at the neuromuscular junctionassociation with both acetylcholinesterase and a glycolipid. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:932–944. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-03-00932.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sealock R., Butler M.H., Kramarcy N.R., Gao K.X., Murnane A.A., Douville K., Froehner S.C. Localization of dystrophin relative to acetylcholine receptor domains in electric tissue and adult and cultured skeletal muscle. J. Cell Biol. 1991;113:1133–1144. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.5.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieb J.P., Dorfler P., Tzartos S., Wewer U.M., Ruegg M.A., Meyer D., Baumann I., Lindemuth R., Jakschik J., Ries F. Congenital myasthenic syndromes in two kinships with end-plate acetylcholine receptor and utrophin deficiency. Neurology. 1998;50:54–61. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simionescu N., Simionescu M. Galloylglucoses of low molecular weight as mordant in electron microscopy. I. Procedure and evidence for mordanting effect. J. Cell Biol. 1976;70:608–621. doi: 10.1083/jcb.70.3.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G.D., Sander M., Lau K.S., Huang P.L., Stull J.T., Victor R.G. Impaired metabolic modulation of alpha-adrenergic vasoconstriction in dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:15090–15095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner K.R., Cohen J.B., Huganir R.L. The 87K postsynaptic membrane protein from Torpedo is a protein-tyrosine kinase substrate homologous to dystrophin. Neuron. 1993;10:511–522. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90338-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson R.A., Henry M.D., Daniels K.J., Hrstka R.F., Lee J.C., Sunada Y., Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O., Campbell K.P. Dystroglycan is essential for early embryonic developmentdisruption of Reichert's membrane in Dag1-null mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1997;6:831–841. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.6.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood S.J., Slater C.R. The contribution of postsynaptic folds to the safety factor for neuromuscular transmission in rat fast- and slow-twitch muscles. J. Physiol. 1997;500:165–176. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R., Salpeter M.M. Acetylcholine receptors in innervated muscles of dystrophic mdx mice degrade as after denervation. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:8194–8200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08194.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B., Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O., Moomaw C.R., Slaughter C.A., Campbell K.P. Heterogeneity of the 59-kDa dystrophin-associated protein revealed by cDNA cloning and expression. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:6040–6044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B., Jung D., Rafael J.A., Chamberlain J.S., Campbell K.P. Identification of alpha-syntrophin binding to syntrophin triplet, dystrophin, and utrophin. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:4975–4978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.4975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]