Abstract

The interesting observation was made 20 years ago that psychotic manifestations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus are associated with the production of antiribosomal-P protein (anti-P) autoantibodies. Since then, the pathogenic role of anti-P antibodies has attracted considerable attention, giving rise to long-term controversies as evidence has either contradicted or confirmed their clinical association with lupus psychosis. Furthermore, a plausible mechanism supporting an anti-P–mediated neuronal dysfunction is still lacking. We show that anti-P antibodies recognize a new integral membrane protein of the neuronal cell surface. In the brain, this neuronal surface P antigen (NSPA) is preferentially distributed in areas involved in memory, cognition, and emotion. When added to brain cellular cultures, anti-P antibodies caused a rapid and sustained increase in calcium influx in neurons, resulting in apoptotic cell death. In contrast, astrocytes, which do not express NSPA, were not affected. Injection of anti-P antibodies into the brain of living rats also triggered neuronal death by apoptosis. These results demonstrate a neuropathogenic potential of anti-P antibodies and contribute a mechanistic basis for psychiatric lupus. They also provide a molecular target for future exploration of this and other psychiatric diseases.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystemic autoimmune disease characterized by a wide range of clinical manifestations and the production of a variety of autoantibodies frequently directed against intracellular components (1). In most cases, the relationship between particular autoantibodies and disease manifestations is obscure. This is especially true for the abnormalities of the central nervous system (CNS). Neuropsychiatric (NP) symptoms or cognitive decline can be found in different series affecting a range from 6 to 95% of the patients (2–5). The CNS compromise varies from mild to severe but can be the most devastating manifestation of the disease, often being difficult to diagnose and treat (3, 6–9). In contrast with focal organic brain syndromes, such as strokes and seizures resulting from thrombotic and vasculitic alterations, the pathogenic mechanisms of diffuse brain manifestations such as mood and anxiety disorders or psychosis, as well as cognitive dysfunction, remain largely unknown (3, 8). Even without overt CNS symptoms, the brain of SLE patients presents nonfocal atrophy and cortical and subcortical functional alterations of unknown origin (10).

Several autoantibodies have been associated with NP-SLE. These include autoantibodies against antiribosomal-P proteins (anti-Ps) (11), neurofilaments (12), microtubule-associated protein 2 (13), N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) (14, 15), endothelial cells (16), and neuronal cells (17) (for reviews see references 3, 8). However, excluding anti-NMDAR antibodies, all of the other associations lack mechanistic explanations. Immunocomplex-mediated small vessel inflammation, which typically leads to tissue injury in the kidney and other organs, seems not to be important in the psychiatric manifestations (8). Evidence from other autoimmune diseases indicates that certain autoantibodies can directly cause damage to neuronal physiology by interfering with the function of cell-surface elements such as receptors and ion channels (18). In SLE, this possibility has been suggested by the finding of a subset of anti–double-stranded DNA autoantibodies that cross react with NMDAR and induce neurotoxicity and cognitive alterations (19–22). It thus seems likely that other autoantibodies, as yet unknown, could also display neuropathogenic properties by interacting with a suitable neuronal surface target to contribute to NP lupus.

Anti-P autoantibodies (23, 24) have been viewed for a long time as the most reiterative but also controversial candidates for a neuropathogenic role in SLE (5, 8, 25, 26). These antibodies are quite specific for SLE, but their reported prevalence varies widely from 6–45%, seemingly depending on differences in methodology and ethnic backgrounds (5, 26). There is also evidence that healthy individuals express anti-P antibodies masked by antiidiotypic antibodies, suggesting that anti-P antibodies could become detectable in SLE patients because of a loss of this regulatory network (27, 28). In 1987, Bonfa et al. made the seminal observation that anti-P autoantibodies associate with lupus psychosis (29). Afterward, anti-P has also been associated with lupus hepatitis and nephritis (30), but its pathogenic role remains controversial. Several studies have confirmed the clinical association between anti-P antibodies and psychiatric lupus, occasionally extending it to severe depression and other CNS-diffuse manifestations (8, 25, 31–33). The serum titer of anti-P has been reported to follow the psychiatric manifestations (29). Anti-P antibodies have also been detected in the cerebro spinal fluid of NP-SLE patients (34, 35). Furthermore, a recent study reported that injection of anti-P antibodies into the mice brain provokes a depression-like behavior (36). All of these data constitute strong evidence for a pathogenic role of anti-P antibodies (30, 37). However, several contradicting reports failed to find any association with NP-SLE (5, 26, 38), thus creating a controversy. Methodological and clinical considerations could explain certain discrepancies but are in fact insufficient to dissipate the doubts raised on the actual role of anti-P antibodies in NP-SLE (2, 5, 25, 37). Contributing to this uncertainty is the lack of explanatory mechanisms able to causally relate anti-P antibodies with CNS dysfunction (25). Actually, molecular, cellular, and physiological bases for the postulated anti-P neuropathogenicity remain unknown, and the direct effects of these antibodies on neurons have not been reported.

Anti-P autoantibodies recognize a C-terminal epitope of 22 amino acids shared by three highly conserved phosphoproteins called P proteins−P0 (38 kD), P1 (19 kD), and P2 (17 kD)—of the large ribosomal subunit (23, 24). Further refinement has restricted the P epitope location to the last 11 C-terminal residues (39). Being intracellular, these ribosomal antigens are normally inaccessible to circulating antibodies. However, a crucial advance toward understanding the pathogenic role of anti-P antibodies has been the observation that they bind to the surface of several kinds of cells, including human neuroblastoma and hepatoma cells (40). The cell-surface target for anti-P antibodies is currently believed to be a 38-kD protein, which is assumed to correspond to a cell-surface form of the P0 ribosomal protein (37). Subsequent studies led to the notion that anti-P antibodies might somehow penetrate into living cells and provoke deleterious effects (41). In this scenario, anti-P antibodies would have a generalized deleterious potential to cause dysfunctions in a variety of different cells (30, 37).

In this paper, we provide a novel mechanistic framework that is more specifically applicable to a neuropathogenic role for the anti-P antibodies. We demonstrate that a new nonribosomal protein present at the cell surface of certain neuronal populations is recognized by anti-P autoantibodies, with consequences for neuronal calcium homeostasis and survival.

RESULTS

A high molecular mass cell-surface protein (p331) exposes an extracellular P epitope

In a previous paper, we found anti-P antibodies in 15% of our cohort of 141 SLE patients, including 2 with psychosis (33). From these two patients with psychosis, we isolated specific anti-P antibodies by affinity chromatography using a synthetic P peptide of 11 residues (P11) (39). Unless otherwise specified, all of the experiments were performed indistinctly with either one of these sera, as both produced similar results. In the immunoblot, these affinity-purified human anti-P against P11 (α-hP11) antibodies showed reactivity with the three ribosomal P proteins: P0 (38 kD), P1 (19 kD), and P2 (17 kD; Fig. 1 A), which was blocked by competition with the synthetic P11 peptide, thus indicating specificity. With these affinity-purified antibodies, we analyzed neurons in primary culture and neuroblastoma N2a cells, searching for cell-surface anti-P immunoreactivity and molecular targets. Two complementary approaches, biotinylation assays and direct cell-surface protein immunocapture and precipitation, which we had used in previous studies to detect proteins at the cell surface (42–44), unexpectedly revealed not the described 38-kD protein (37) but a very high molecular mass protein (>200 kD) that exposes a cell-surface P epitope (Figs. 1 and Figs.2). We provisionally named this protein p331 based on its sequence data (see next section).

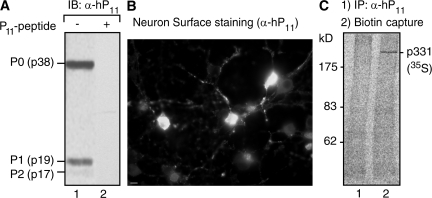

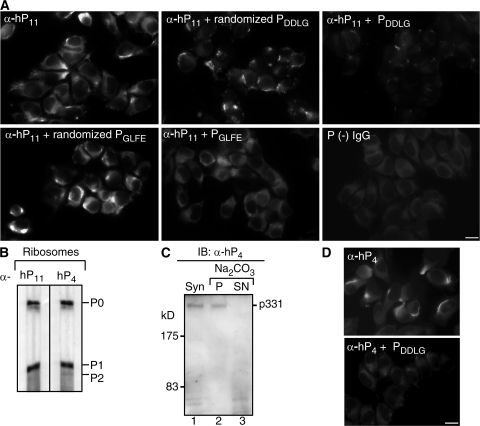

Figure 1.

Affinity-purified anti-P antibodies recognize a cell-surface protein of high molecular mass (p331) in neurons. (A) Immunoblot (IB) with affinity-purified anti-P antibodies (α-hP11) shows reaction with the P ribosomal proteins P0 (38 kD), P1 (19 kD), and P2 (17 kD; lane 1), which is blocked by the P peptide (lane 2). (B) Anti-P staining of the neuronal surface. Brain cortical primary culture cells were incubated with α-hP11 antibody at 4°C, and fixed and incubated with secondary FITC–anti–human antibody. Some neurons show intense surface staining. Bar, 10 μm. (C) Detection of anti-P target at the surface of brain cortical neurons. Neurons in primary culture were metabolically labeled for 16 h with 100 μCi [35S]methionine-cysteine, biotinylated at 4°C, and subjected to immunoprecipitation with either control P (−) serum from an SLE patient (lane 1) or α-hP11 antibodies (lane 2). The immunoprecipitated proteins were separated from the sepharose beads by heating in SDS buffer, and the biotinylated proteins were precipitated with immobilized neutravidin protein. A single high molecular mass protein (p331) is detected.

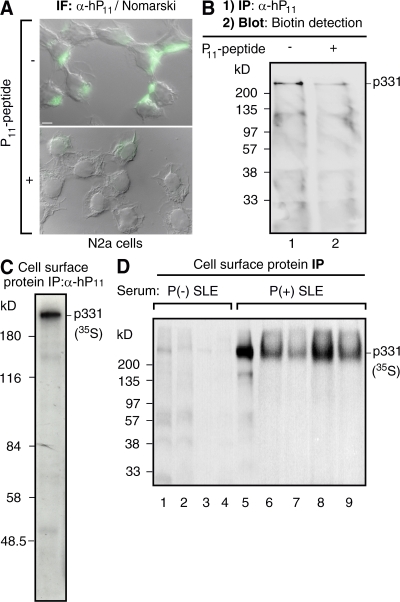

Figure 2.

Antibodies against ribosomal P epitope recognize p331 in the surface of N2a cells. (A) Anti-P indirect immunofluorescence in intact neuroblastoma N2a cells. The cell-surface staining, superimposed over images of Nomarski interference microscopy, is asymmetrically distributed and is displaced by the P peptide. Bar, 10 μm. (B) Biotinylation assays detect p331 as the cell-surface P epitope–bearing protein. Intact N2a cells were biotinylated at 4°C, lysed, and subjected to immunoprecipitation with α-hP11 antibodies either in the absence (lane 1) or presence (lane 2) of P peptide. The biotinylated proteins, resolved by SDS-PAGE, were detected in the blot with horseradish peroxidase–streptavidin. (C and D) Direct immunoprecipitation of cell-surface p331 anti-P target. N2a cells metabolically labeled for 16 h with 100 μCi [35S]methionine-cysteine were incubated intact, at 4°C, with either α-hP11 (C) or sera from lupus patients (D), including anti-P (−; lanes 1–4) or anti-P (+) with psychosis (lane 5) or without NP-SLE (lanes 6–9). The cells were lysed, and the immunocomplexes formed at the cell surface were precipitated with protein A–sepharose, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by fluorography, showing only the p331 protein.

Indirect immunofluorescence showed anti-P reactivity in rat brain cortex cells in primary culture. To avoid permeabilization during fixation, we initially incubated intact cells with the antibodies at 4°C and, after washing and fixing them, added the secondary antibody. Only certain neurons displayed strong fluorescence staining (Fig. 1 B), suggesting that a subset of cortex neurons express a cell-surface P antigen, at least at immunofluorescence-detectable levels. To identify the anti-P molecular target, we had to increase the sensitivity of the biotinylation assays by using metabolically labeled cells and phosphoroimaging detection (45). This strategy disclosed a single protein of high molecular mass (p331) in the neuronal surface (Fig. 1 C).

Rat neuroblastoma N2a cells gave coincident results, providing a more homogeneous cellular system that facilitated further analysis. These cells displayed strong and asymmetrically localized anti-P cell-surface staining (Fig. 2 A). Regular biotinylation assays indicated that most of this cell-surface immunoreactivity is attributable to the high molecular mass p331 antigen. After biotinylation of the cell surface, we initially immunoprecipitated with anti-P antibodies and then assessed the biotinylated proteins in the immunocomplexes by blotting with streptavidin conjugates (42, 43, 45). This stepwise order of the experiment ensured that the detected proteins are indeed biotinylated and, therefore, exposed at the cell surface. Only the p331 showed up in the cell surface of N2a cells (Fig. 2 B). The blocking effect of the P11 peptide indicated that p331 contains a P epitope (Fig. 2, A and B).

This unexpected p331 anti-P cell-surface target was further confirmed by direct immunocapture from metabolically labeled cells. N2a cells were initially metabolically labeled and then incubated intact with α-hP11 antibodies at 4°C. The immunocomplexes formed at the cell surface were isolated by protein A–sepharose precipitation, as previously described (42, 43). This approach also revealed p331 as the main, if not the only, protein exposing a P epitope at the cell surface (Fig. 2 C). Similar experiments made with whole serum instead of affinity-purified α-hP11 antibodies also demonstrated p331 as the cell-surface anti-P target (Fig. 2 D). Anti-P (−) sera showed no reaction with this p331 protein, whereas anti-P (+) sera from five different lupus patients, including one patient with lupus psychosis (lane 5) and four patients without NP symptoms (lanes 6–9), immunoprecipitated only the p331 from the cell surface (Fig. 2 D). All of these results disclosed a new P antigen–bearing protein accessible to anti-P autoantibodies from the extracellular medium, expressed by at least certain neurons in the brain (as shown in Fig. 1).

p331 is a novel integral membrane protein of unknown function expressed in brain neurons termed neuronal surface P antigens (NSPAs)

Rat brain synaptosomal fractions highly enriched in synaptic regions (46) provided additional evidence of the presence of p331 in brain neurons. Only P (+) sera, either from a patient with lupus psychosis or from patients without NP-SLE, recognized the p331 protein in synaptosomes (Fig. 3 A). Given the variety of autoantibodies produced by lupus patients, some sera also showed other immunoblot bands. However, when using affinity-purified α-hP11 antibodies instead of serum, p331 appeared as the main detectable anti-P target at the synaptic region (synaptosomes; Fig. 2 B, lane 1).

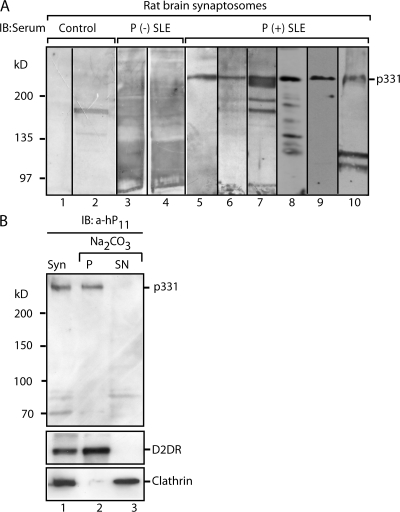

Figure 3.

The anti-P target p331 is an integral membrane protein present in rat brain synaptosomes. (A) Detection of p331 in rat brain synaptosomes. Membrane fractions prepared from rat brain synaptosomes were analyzed by immunoblot (IB) with control sera from healthy individuals (lanes 1 and 2), anti-P (−) from two SLE patients (lanes 3 and 4), and anti-P (+) from six SLE patients (lanes 5–10), including one with psychosis (lane 10). All P (+) serum detected p331, providing further evidence of its expression in brain neurons. (B) p331 is an integral membrane protein and the main α-hP11 target in synaptosomes. Immunoblot of synaptosomes (Syn) with affinity-purified α-hP11 antibodies shows p331 as the main target (lane 1). The lower bands are degradation products that vary in different experiments. Sodium carbonate extraction of synaptosomal membranes shows that p331 distributes exclusively to the pellet (P; lane 2), similar to the integral membrane protein dopamine receptor (D2DR), whereas peripherally associated clathrin distributes to the supernatant (SN; lane 3).

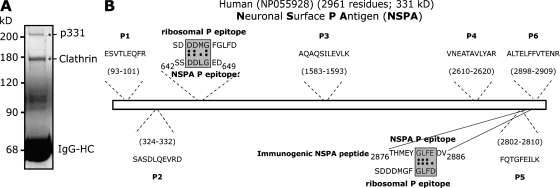

Synaptosomes provided abundant material for distinguishing between extrinsic and intrinsic membrane proteins by using the standard method of sodium carbonate extraction (47), as well as for preparative immunoprecipitations. Resistance to alkaline extraction (e.g., recovery of the protein in the pellet of extracted membranes) indicated that p331 is an integral membrane protein (Fig. 3 B, lanes 2 and 3). Preparative immunoprecipitations from synaptosomal fractions (P2 fraction) (46) yielded enough p331 to perform mass spectrometric analysis and microsequencing (Fig. 4 A). The major accompanying protein of 180 kD corresponded to the clathrin heavy chain. It might be that p331 interacts with clathrin, which is a cytosolic protein and certainly not an anti-P target. In contrast, p331 turned out to be a novel protein. Six internal peptides (P1–6) were microsequenced and found to align with the sequence of the human protein NP055928 (Fig. 4 B), which is of unknown function. This protein is encoded by the complementary DNA NM015113 originally reported in a high molecular weight complementary DNA library of the human brain (48). Its unique gene, located in chromosome 17, lacks any homologues in the entire human genome and encodes a protein of 2,961 residues (with an estimated molecular mass of 331 kD), which contains a calcium-binding domain, an anaphase-promoting complex 10 domain, a CUB domain, and two zinc-binding domains. It possesses 8–11 hydrophobic regions, each encompassing 19–23 residues, but its large size did not allow us to predict which of them correspond to membrane-spanning domains. Because it lacks an N-terminal signal peptide, its membrane insertion is most likely directed by an internal signal peptide that is also a transmembrane domain, similar to type II and to several polytopic proteins, but the actual signal peptide remains unpredictable by the available algorithms. Predicting transmembrane domains and discriminating them from signal peptides that currently look the same has inherent difficulties, which can only be circumvented by experimental data (49, 50). The sequence of NP055928 is available from GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ under accession no. NP_055928. Because our results indicated that p331 (NP055928) exposes a P epitope to the cell surface, we termed this protein NSPA.

Figure 4.

p331 is a novel protein named NSPA. (A) Preparative immunoprecipitation of neuronal anti-P target. Presynaptosomal fractions (P2) obtained from 50 rat brains were subjected to immunoprecipitation with affinity-purified anti-P antibodies. SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining show two main bands (asterisks; IgG-HC, IgG–heavy chain) that were analyzed by mass spectrometry and microsequencing. The 180-kD protein corresponds to clathrin, whereas p331 corresponds to the human protein NP055928 of unknown function. (B) Sequence of p331-derived peptides, possible P epitopes, and the immunogenic NSPA peptide. Six out of six peptides derived from p331 (P1–6) matched perfectly with the putative human protein NP055928 at the indicated regions. We named this protein NSPA. The NSPA sequences 644DDLG647 and 2884GLFD2887 are homologous to the ribosomal DDMG and GLFD P epitopes within the 11 C-terminal region. The peptide sequence 2876–2886 used to immunize rabbits to obtain anti-NSPA antibodies is also shown.

Possible P epitopes displayed by NSPA at the cell surface

Optimal binding of anti-P antibodies to the last 11 C-terminal residues of P ribosomal proteins (SE/DDDMGFGLFD) depends on clusters of acidic (E/DDD) and hydrophobic (GFGLFD) residues, which very likely correspond to two overlapping epitopes (51, 52). The phosphorylated amino acids of the P proteins are not critical epitope determinants (51). Analysis of peptide arrays has suggested that the GFGLFD motif is the key determinant recognized by anti-P antibodies (52). In NSPA, a region encompassing residues 2881GLFE2884 partially coincides with this P ribosomal epitope (Fig. 4 B), which accepts the conservative D/E substitution (53). Other studies modeled the paratope–epitope interaction on a monoclonal antibody and suggested that the DDxGF sequence, present in all members of the P protein family (i.e., P0, P1, and P2), conforms to a P epitope in which any residue can occupy the x position (54). In NSPA, a motif like this is represented by the sequence 644DDLG647 (Fig. 4 B). To assess whether these two motifs, in the context of NSPA, could mediate interactions with anti-P antibodies, we tested the blocking capability of synthetic peptides encompassing these regions (Fig. 5 A). NSPA synthetic peptides 642SSDDLGED649 and 2876THMEYGLFEDV2886 (underlined residues could conform a P epitope) dramatically decreased the characteristic asymmetrical cell-surface staining of α-hP11 antibodies, whereas the scrambled peptides containing the same residues in random positions had minor effects (Fig. 5 A). Because the peptide-array analysis of Mahler et al. (52) did not attribute a major role to the acidic cluster in the anti-P antibody recognition, contrasting with the findings of Hasler et al. (51), we tested more directly whether the NSPA peptide 642SSDDLGED649 could effectively interact with anti-P antibodies. Affinity chromatography with this peptide isolated a subset of anti-P antibodies (α-hP4) from P (+) sera. These α-hP4 antibodies mimicked the previously characterized α-hP11 antibodies, recognizing the P ribosomal proteins from rat liver (Fig. 5 B) and the p331 in carbonate-extracted synaptosomal membranes (Fig. 5 C), and displaying the regionalized immunofluorescent pattern at the surface of N2a cells, which was completely abrogated by the 642SSDDLGED649 peptide (Fig. 5 D). Therefore, our results indicate that NSPA exposes two regions to the cell surface encompassing the residues 644DDLG647 and 2881GLFE2884, which are recognized by anti-P antibodies, most likely within the context of a conformational epitope given their mutually distant locations.

Figure 5.

Two distant regions of NSPA containing 644DDLG647 and 2881GLFD2884 sequences participate in the cell-surface interaction with anti-P autoantibodies. (A) Blocking activity of synthetic peptides against the cell-surface staining of α-hP11 antibodies involved both 644DDLG647 and 2881GLFD2884 NSPA sequences. Indirect immunofluorescence with α-hP11 in nonpermeabilized N2a cells either in the absence or presence of NSPA peptides PDDLG (642SSDDLGED649) and PGLFE (2876THMEYGLFEDV2886) or their corresponding scrambled peptides, randomized PDDLG (LGDSSEDLD) and randomized PGLFE (DEYTEHFGLVM). Both PDDLG and PGLFE peptides, but not their randomized versions, decreased the cell-surface α-hP11 immunostaining. An IgG fraction isolated from a P (−) serum gives no staining. In all of the images, some staining background is depicted on purpose to visualize the cells. Bar, 10 μm. (B–D) A subset of anti-P antibodies (α-hP4) recognize P ribosomal proteins and NSPA. A P (+) serum was subjected to affinity chromatography with the NSPA peptide DDLGEDD containing a putative P epitope (DDLG). The isolated α-hP4 antibodies, similar to the α-hP11 antibodies, recognize in immunoblot (IB) the P ribosomal proteins in ribosomes isolated from rat liver (B), and the high molecular mass protein (p331) the in synaptosomes (Syn; lane 1) and pellet (P; lane 2) but not the supernatant (SN; lane 3) of carbonate-extracted membranes (C). (D) Indirect immunofluorescence with α-hP4 antibodies shows the characteristic asymmetrical cell-surface staining, which was abrogated by the PDDLG (642SSDDLGED649) peptide. Bar, 10 μm.

In the brain, NSPA is exclusively expressed by neurons at specific zones

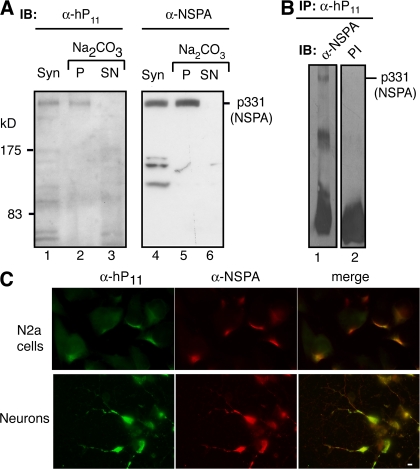

The finding of NSPA prompted us to produce rabbit antibodies suitable for immunohistochemistry and determine which brain cells and regions might be targets for anti-P autoantibodies. Anti-P antibodies are not convenient tools for this purpose because of their interaction with ubiquitous ribosomal proteins. We tried different peptides of NSPA as immunogens. Interestingly, a polyclonal antibody raised against an NSPA peptide containing the 2881GLFE2884 motif (THMEYGLFEDV; Fig. 4 B) did not recognize any of the P ribosomal proteins (not depicted), whereas it did interact with NSPA (Fig. 6). Thus, anti-P autoantibodies seem to differ from the antibodies produced by immunization, at least in the recognition of the GLFE sequence. However, these α-NSPA antibodies recognized the integral membrane protein p331 in alkaline-extracted synaptosomal membranes (Fig. 6 A), and showed cross reaction (Fig. 6 B) and cell-surface colocalization with α-hP11 antibodies (Fig. 6 C), indicating that they interact with the same protein recognized by α-hP11 antibodies.

Figure 6.

Polyclonal antibodies against NSPA. (A) Immunoblots (IB) with human α-hP11 autoantibodies and rabbit anti-NSPA (α-NSPA) antibodies of carbonate-extracted synaptosomal membranes. Both antibodies recognize the high molecular mass protein (p331/NSPA) in total the synaptosomal membranes (Syn; lanes 1 and 4) and pellet (P; lanes 2 and 5) but not the supernatant (SN; lanes 3 and 6) of carbonate extraction. (B) Immune cross reaction of NSPA with α-hP11 and α-NSPA antibodies. The p331/NSPA protein immunoprecipitated (IP) by α-hP11 from extracts of a synaptosomes (lane 1) is recognized in immunoblot by α-NSPA but not by the preimmune serum (PI; lane 2). (C) Double immunofluorescence with α-NSPA and α-hP11 antibodies. Nonpermeabilized N2a cells and cortical neurons in primary culture both show complete cell-surface colocalization of α-NSPA (red) and α-hP11 (green) staining. All of these results indicate that α-NSPA and α-hP11 antibodies recognize the same protein. Bar, 10 μm.

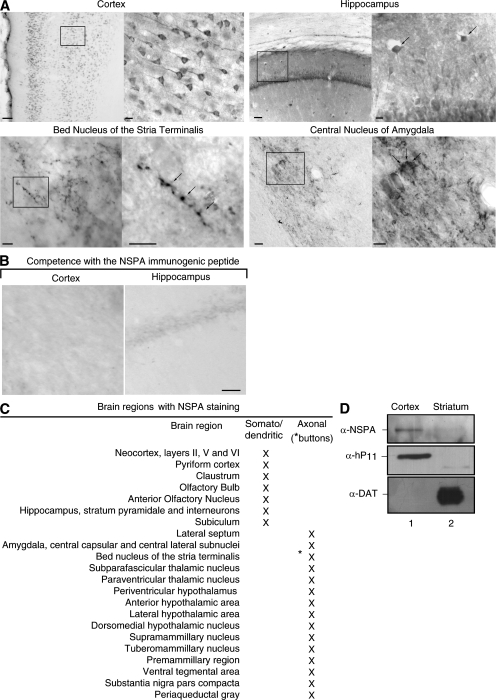

Strikingly, immunohistochemistry of the rat brain showed that α-NSPA antibody stained only neurons and only at specific brain zones (Fig. 7). In the neocortex, α-NSPA stained neurons of layers I, II, III, and V with somatodendritic distribution. Layer IV lacks staining. In the hippocampus, α-NSPA staining predominates in somatodendritic regions of interneurons (Fig. 7 A, arrows). Neurons of the bed nucleus of stria terminalis show NSPA in a pattern characteristic of synaptic buttons. In the central nucleus of the amygdala, NSPA also appeared concentrated in synaptic regions, including calyx-like terminals (Fig. 7 A, arrows), very much like the CGRP-immunoreactive calices that originate from the lateral parabrachial nucleus (55). The brain regions displaying α-NSPA immunostaining (Fig. 7 C) included regions preferentially involved in higher brain functions such as cognition, emotion, and memory. The specificity of the immunostaining was shown by its complete abrogation with the immunogenic peptide (Fig. 7 B) and by its correlation with NSPA expression (e.g., the lack of staining in the stratium and the lack of immunoblot detection of NSPA in synaptosomes isolated from this region; Fig. 7 C). In synaptosomes isolated from brain cortex, we detected NSPA by using not only α-NSPA or α-hP11 antibodies (Fig. 7 C) but also rabbit antibodies raised against a peptide of 11 residues of the C-terminal region of the ribosomal p38 (not depicted). The results summarized in Fig. 7 C indicate that NSPA is expressed by neurons of certain regions of the brain, which might well be involved in NP-SLE.

Figure 7.

NSPA is expressed by neurons at specific regions of the brain. (A) Immunohistochemistry of NSPA in the rat brain. Some brain regions with framed zones of higher magnification (insets) are illustrated. Arrows indicate interneurons, synaptic buttons, and calyx-like terminals. Bars: (cortex, left) 100 μm; (cortex, right) 10 μm; (hippocampus, left) 50 μm; (hippocampus, right) 10 μm. The bed nucleus of stria terminalis and the central nucleus of the amygdala are also shown. Bars, 10 μm. (B) The immunogenic NSPA peptide completely abrogated the staining (not depicted). (C) Summary of NSPA expression in neurons of different areas of the brain, indicating whether the staining was detected in somatodendritic or axonal (synaptic buttons) regions. (D) Correspondence between immunohistochemical staining and immunoblot detection of NSPA. Synaptosomes were isolated from the cortex (lane 1), which shows positive immunohistochemical staining, and from the striatum (lane 2), which completely lacks staining. Immunoblot with α-NSPA and α-hP11 show p331 only in synaptosomes from the cortex. In contrast, the dopamine transporter (DAT), which is 90% expressed in the striatum (reference 73), was exclusively detected in this region, thus showing that these two brain areas were effectively isolated.

Both anti-P and anti-NSPA antibodies elicit calcium entry into cortical neurons in primary culture

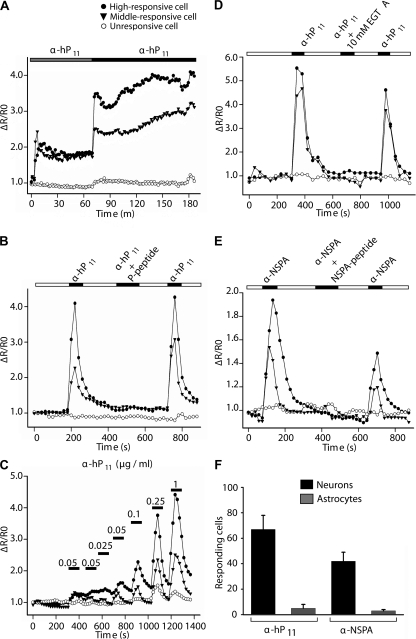

Having shown that anti-P antibodies interact with a protein located at the neuronal surface, we went on to study their possible impact on neuronal function. Initially, we monitored cytosolic calcium in rat cortical cultures loaded with fluorescent calcium indicators. Calibration experiments showed that resting calcium levels in these cultures fluctuate at ∼50 nM for astrocytes and 80 nM for neurons. Exposure to anti-P antibodies caused a rapid and sustained increase in cytosolic calcium in neurons (Fig. 8 A). The effect, which was readily reversible upon removal of the antibody, was blocked by the synthetic P peptide (Fig. 8 B), showed dependency on antibody concentration (Fig. 8 C), and reflected a calcium influx from the extracellular medium, as judged by inhibition with EGTA (Fig. 8 D). Affinity-purified anti-P antibodies from three different lupus patients that developed psychosis gave similar results, whereas the IgG fraction from the serum of normal individuals showed no effect (unpublished data). Strikingly, our anti-NSPA antibodies mimicked the effects of the anti-P antibodies, though in a lesser magnitude at a similar concentration (Fig. 8 E). Rabbit affinity-purified control antibodies against proteins unrelated to ribosomal P proteins caused no effect (unpublished data).

Figure 8.

Anti-P and anti-NSPA antibodies induce calcium influx in cortical primary neurons. Graphs illustrate cells displaying different degrees of responsiveness. (A) α-hP11 antibodies induce a sustained increase in calcium levels. The cells were incubated with 0.1 μg/ml (gray bar) and 0.2 μg/ml (black bar) of α-hP11 antibodies. (B) Neuronal responses to α-hP11 are specific and reversible. The increased calcium levels elicited by α-hP11 returned to basal levels after washing the antibody (white bar) and were abrogated by preincubating the antibodies with the P peptide (black bar). (C) Dose-dependent responses to α-hP11. The same cell showed increased responses to increasing amounts of antibody added after a wash out. Horizontal bars represent incubation time periods. (D) Chelation of extracellular Ca2 + with 10 mM EGTA abolished the effects of α-hP11. (E) 1 μg/ml of α-NSPA antibodies also provoke an increase in neuronal calcium levels of lower magnitude, which is reversible, specifically inhibited by the corresponding immunogenic peptide, and abolished by EGTA. (F) Neurons predominantly responded to both α-hP11 and α-NSPA. Although 67 and 51% of neurons increased their calcium levels in response to either α-hP11 or α-NSPA, respectively, only 5 and 3% of the astrocytes showed detectable responses. Control experiments showed that astrocytes responded to glutamate (not depicted). Error bars represent the mean ± SEM.

Anti-P acted selectively on neurons. Astrocytes, in which we could not detect NSPA by immunohistochemistry, responded very weakly or not at all, neither to human anti-P nor to rabbit anti-NSPA antibodies (Fig. 8 F). These results demonstrate that anti-P antibodies can effectively interfere with neuronal function through specific interaction with an extracellularly exposed P epitope. Because NSPA was the only anti-P target that we could detect in neurons and the antibodies against it also triggered calcium influx, it seems very likely that NSPA mediates the effects of anti-P antibodies.

Anti-P antibodies induce apoptosis and loss of neurons both in vitro and in vivo

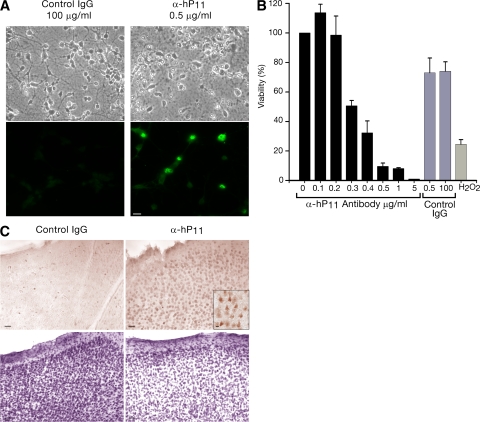

In neurons, moderate but sustained Ca2 + overloads are known to cause cell death (56). Consistently, brain cultures exposed to anti-P antibodies developed several signs of neuronal stress, including morphological changes, dramatic decrease of neuronal processes, nuclear alterations, and activation of the apoptotic marker caspase-3 (Fig. 9 A). Cell viability decreased, resulting in a loss of cells from the culture (Fig. 9 B).

Figure 9.

α-hP11 autoantibodies induce neuronal apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. (A) α-hP11 antibodies induce apoptosis in neurons in primary culture. Cells were incubated with 100 μg/ml of control IgG or 0.5 μg/ml of α-hP11 for 48 h. Indirect immunofluorescence against activated caspase-3 revealed apoptosis. (B) α-hP11 antibodies decrease neuronal viability. MTT assays show a concentration-dependent loss of viability. In contrast with the 30% viability loss caused by 0.5 μg/ml of an IgG fraction from a normal individual, the same concentration of α-hP11 lowered the viability by ∼90%. For comparison, H2O2 at 50 μM decreased the viability by 80%. Error bars represent the mean ± SEM. (C) α-hP11 antibodies induce apoptosis in neurons in situ. The rat brain cortex was injected with 0.7 μg of either control IgG or α-hP11 in contralateral sides, fixed after 24 h, and either stained with Cresyl violet or treated for immunohistochemistry of activated caspase-3. The region injected with α-hP11 shows caspase-3 activation (bottom right and inset) and lower cell density (top right) and. Bars, 100 μm.

Definitive proof of a neuropathogenic role of anti-P antibodies requires demonstration of their neurotoxicity in the brain. To this end, we performed in vivo experiments. Injection of anti-P antibodies into the primary motor cortex of living rats resulted in neuronal apoptosis, as revealed by caspase-3 activation, and loss of neurons (Fig. 9 C). Similar results were observed in four rats and with α-hP11 antibodies from two different SLE patients, including one with psychosis. Therefore, anti-P antibodies do have a strong neurotoxic potential to lead to CNS compromise.

Anti-P antibodies isolated from patients without NP-SLE also induce calcium influx and neuronal apoptosis

In all previous functional experiments, we used anti-P antibodies affinity purified from two SLE patients that presented psychosis at the moment of obtaining the serum samples. However, our results showed that anti-P (+) serum from patients that manifested no NP symptoms also recognized NSPA (Figs. 2 and Figs.3). Thus, it seems crucial to determine whether the anti-P antibodies produced by these two groups of patients display relevant functional differences to account for developing or not developing NP-SLE. Strikingly, anti-P antibodies affinity purified from two SLE patients that had never presented NP symptoms elicited sustained calcium influx and apoptosis (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20071285/DC1), thus revealing a pathogenic equivalence to the anti-P antibodies produced by SLE patients with psychosis.

DISCUSSION

We found a new target for anti-P autoantibody, termed NSPA, that is expressed at the surface of brain neurons and can potentially mediate anti-P–dependent NP symptoms. Sequence data and biochemical characterization showed that NSPA corresponds to a new integral membrane protein of high molecular mass (331 kD). A polyclonal antibody suitable for immunohistochemistry demonstrated that NSPA is expressed by neurons from specific regions of the brain, including regions involved in emotional responses, memory, and other higher brain functions that become affected in neuropshychiatric lupus. In addition, we disclosed for the first time that anti-P autoantibodies have neurotoxic potential, as shown on neurons in culture and in situ. Thus, our results contribute to mechanistic support for the role of anti-P autoantibodies in NP-SLE that has been studied for more than 20 years.

More than 100 autoantibodies have been described in SLE, but very few can be associated with clinical outcomes and even fewer revealed their pathogenic mechanism (1, 8). Particularly elusive has been the role of autoantibodies in the pathogenesis of NP-SLE (2, 6). The subset of anti–double-stranded DNA reported to cross react with NMDAR, resulting in apoptotic neuronal loss and cognitive impairment in mice, so far constitute the best documented factor with neuropathogenic potential to mediate CNS dysfunctions (19–22). However, the clinical evidence still seems limited (57). Two series coincidently reported their association with depression but differed in their association with cognitive decline in lupus patients (14, 15). In contrast, anti-P antibodies had remained for a long time as the most promising candidates for a neuropathogenic role in SLE, supported by numerous clinical data that reported their association with lupus psychosis and/or depression (25, 34, 35). However, contradictory studies (5, 26, 38), combined with the lack of any suitable neuronal target or evidence of deleterious actions on neuronal function, have consistently raised doubts about the pathogenic role of anti-P antibodies (25, 37).

The following evidence indicates that NSPA is a neuronal target of anti-P antibodies able to mediate neurotoxic effects. First, affinity-purified anti-P antibodies used in biotinylation and immunocapture assays detected NSPA as the only cell-surface target, both in N2a cells and in cortex neurons in primary culture. Experiments of alkaline extraction of synaptosomal membranes also showed NSPA as the only protein recognized by anti-P antibodies. Second, peptide competition blocked the interaction of anti-P antibodies with the cell surface, indicating that NSPA exposes a P epitope at the cell surface, very likely conformed by two separate regions encompassing residues 644DDLG647 and 2881GLFE2884. Third, affinity-purified anti-P antibodies from two SLE patients with psychosis and rabbit anti-NSPA antibodies both triggered calcium influx into neurons in primary culture showing specific target dependency, as demonstrated by the corresponding blocking peptide. Neither anti-P nor anti-NSPA antibodies elicited calcium influx in astrocytes that do not express NSPA. Fourth, anti-P antibodies elicited caspase-3 activation and neuronal death both in vitro and in the rat brain in vivo. Finally, experiments with rabbit anti-P antibodies raised against the 11 ribosomal C-terminal residues containing the P epitopes mimicked the reactivity and the effects of both α-hP11 and α-NSPA antibodies, including the recognition of cell surface and synaptosomal NSPA, and the induction of calcium influx and apoptosis in neurons (unpublished data). Collectively, these results indicate that anti-P antibodies interact with NSPA through a P epitope exposed at the cell surface, and as a consequence of such interaction, neurons experience enhanced calcium entry and undergo apoptosis.

Our anti-NSPA antibodies allowed us to define the distribution of a cell-surface protein bearing a P epitope in the brain. In immunohistochemistry, we found NSPA being expressed by neurons at specific brain regions, including neocortical layers II, V, and VI, and other zones of relevance for the pathogenesis of NP-SLE, such as the amygdala, which is involved in arousal and emotional responses (58), the cortex and hippocampus, which are involved in memory and higher brain functions (59), and the ventral tegmental area, which is associated with reward processing and drug addiction (60). A recent study reported that anti-P antibodies selectively stained certain limbic regions of the mice brain (36), but it did not clarify whether the immunostaining involved neuronal or glial cell bodies, or axons, and did not identify the antigen recognized by anti-P antibodies. Anti-P antibodies might decorate ribosomes in cells that could become inadvertently permeabilized during the immunohistochemistry. Instead, our α-NSPA antibody only showed immunohistochemical staining in neurons (neural bodies), and in some places we could distinguish immunostaining in axon terminals (synaptic buttons), including the calyx-like axon terminal in the central nucleus of the amygdala. Controls indicating that the immunohistochemical staining corresponds specifically to NSPA included competition with the immunogenic NSPA peptide and correlation with immunoblot detection in synaptosomes obtained from either the cortex or striatum, which displayed or lacked α-NSPA staining, respectively. Thus, our present work not only identifies a new P antigen that is expressed at the neuronal cell surface but also discloses in great detail its distribution in the brain. At least through interaction with NSPA, anti-P antibodies could provoke serious dysfunctions in the CNS and contribute to developing NP disorders.

Because not all SLE patients that produce anti-P antibodies develop an NP disease, an important yet unsolved question is whether anti-P antibodies from SLE patients that do not manifest psychiatric or other diffuse CNS symptoms are functionally equivalent to those produced by SLE patients with psychiatric compromise. We showed that anti-P antibodies from SLE patients without NP disease not only recognize NSPA but also induce calcium influx and apoptosis in neurons, indicating that they possess an equivalent pathogenic potential as psychiatrically associated anti-P antibodies. Therefore, besides the production of anti-P antibodies, additional risk factors are certainly required for eliciting psychiatric manifestations.

Both accessibility into the brain and the presence of other autoantibodies very likely cooperate in developing NP-SLE. Experiments in mice that produce or have been injected with antibodies against NMDAR recently highlighted the requirement of disrupting the blood–brain barrier (BBB) for autoantibody-mediated brain symptoms, which varied according to the region of the BBB breach (21, 22). Evidence of antibody production in situ in the brain and passage across the BBB have been described in SLE patients (22, 61). There are also several conditions that promote BBB breach, including infection, stress, hypertension, and nicotine exposure (21, 22, 62), which can vary among patients. In addition, the variety of NP symptoms in SLE patients very likely involves coexpression of autoantibodies with direct or indirect neuropathogenic potential, such as anti-NMDAR antibodies (19). In this paper, we show that anti-NSPA antibodies share with α-hp11 antibodies the capacity to trigger neuronal calcium influx. Future studies should determine whether SLE patients produce autoantibodies against NSPA, which might be distinct from anti-P antibodies. All of these factors could contribute to the NP outcome of SLE.

The identification of new neuronal surface molecules as autoimmune targets in the CNS also entails general interest. Disorders affecting the neuromuscular junction involve autoantibodies against nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in myasthenia gravis, calcium channels in the Lambert-Eaton syndrome, and potassium channels in Isaac's syndrome (18, 63). Whether autoantibodies underlie certain CNS disorders remains less apparent, as they would require a mechanism to access CNS targets (22). Autoantibody targets with pathogenic potential include the glutamate receptor 3 in Rasmussen's encephalitis (64), metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 in paraneoplastic cerebellar ataxia (65), the NMDAR in SLE (19), and neuropeptides in eating disorders (66). The protein that we described in this study, NSPA, is a candidate for alterations caused either by autoantibodies or mutations that may eventually promote psychiatric disease, not only in SLE. Although the function of NSPA is unknown, we can speculate, by analogy with the mentioned disorders, that it may be related to cell-surface receptors and/or ion channels.

In summary, we have contributed a mechanistic link to the vast body of clinical evidence supporting a role of anti-P antibodies in psychiatric lupus that can explain why they might be pathogenic. Deleterious calcium influxes can be triggered by anti-P antibodies in brain neuronal cells through interaction with NSPA at specific brain zones.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and viability assay

Neuroblastoma N2a cells were grown in DMEM with 7.5% FBS and antibiotics (200 U/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin). Primary cultures of cortical neurons were prepared from rat embryos (E18), as previously described (67), and were maintained for at least 7 d before the experiments, either without or with 4 μm of cytosine arabinoside (Sigma-Aldrich) added 48 h after plating to prevent nonneuronal cell proliferation (68). Cell viability assays were performed by 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium (MTT; Sigma-Aldrich) reduction, as previously described (69), except that the lysis buffer lacks formamide. All of the experiments were performed in triplicate.

Antibodies and affinity chromatography

Anti-P–positive sera from patients with SLE controlled at our Rheumatology Department of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile were screened by ELISA (33) and further characterized by immunoblotting with alkaline-phosphatase (42) against rat liver ribosomes (23). Specific α-hP11 anti-P antibodies were isolated by affinity chromatography (70) using the peptide SDEDMGFGLFD from C-terminal ribosomal P0. Antibodies against NSPA were raised by immunizing rabbits with peptide K-2876THMEYGLFEDV2886 of the human sequence NP055928, coupled to mollusk Concholepas concholepas hemocyanin (Blue Carrier; Biosonda Biotechnology), and were also affinity purified. Polyclonal antibodies were against D2R (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) or against clathrin (donated by T. Kirchhausen, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA).

Detection of P epitope–bearing proteins at the cell surface

Cell-surface biotinylation assays.

Cell-surface biotinylation was performed with Sulfo-NHS-biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to a previously established procedure (42, 43, 45). The cells were lysed in buffer A (50 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, and 1% Triton X-100, supplemented with a cocktail of protease inhibitors including 50 μg/ml pepstatin A and 1 mM PMSF) for 30 min at 4°C, and immunoprecipitation was performed with 10 μg of affinity-purified anti-P antibody prebound to protein A–sepharose, either with or without 50 μg of competing P peptide. After resolving the immunocomplexes by 7.5% SDS-PAGE, biotinylated proteins were detected with horseradish peroxidase–streptavidin (42). For brain cortical primary cultures, the biotinylation assay was performed in metabolically labeled cells for 16 h with 100 μCi [35S]methionine-cysteine. The immunocomplexes were resuspended in 10% SDS and heated to 100°C for 5 min, and after pelleting the beads, the supernatant was collected and incubated with immobilized neutravidin protein for 18 h at 4°C, thus separating by precipitation the cell-surface biotinylated proteins. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and revealed by phosphorimager scanning (Cyclone Storage Phosphor Scanner; PerkinElmer).

Immunocapture of cell-surface P epitope–bearing proteins.

N2a cells grown to confluence in 3.5-cm well dishes were metabolically labeled with 100 μCi [35S]methionine-cysteine for 18 h and incubated intact for 1 h at 4°C with 30 μl of either P-positive serum, to capture P epitope–bearing cell-surface proteins. After exhaustively washing out the unbound antibodies, the cells were lysed in buffer A, protein A–sepharose was added, and the immunocomplexes were sedimented by centrifugation, resolved by 7.5% SDS-PAGE, and revealed by fluorography (42, 43). To detect the high molecular mass anti-P target (p331), it is crucial to use fresh antiproteases, run the dye front out of the gel, and continue the electrophoretic migration for 90 min extra.

Detection of P epitope–bearing proteins in synaptosomes

Synaptosomes were isolated from the rat brain with the Percoll gradient method (46) and lysed in buffer A. Immunoblots were performed with a 1:1,000 dilution of anti-P (+) sera and revealed with electrochemiluminescence (ECL). Immune cross reaction of NSPA was assessed by immunoprecipitation with 10 μg of affinity-purified anti-P antibody prebound to 30 μl of protein A–sepharose (Sigma-Aldrich) and immunoblotting with either preimmune serum or affinity-purified anti-NSPA antibody, followed by peroxidase-labeled anti–rabbit (Rockland) and ECL. Sodium carbonate extraction was performed exactly as previously described (47).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

N2a cells grown in 10-mm coverglasses (VWR Scientific) were fixed and treated for indirect immunofluorescence either in intact cells or in cells permeabilized by 0.2% Triton X-100, as previously described (42, 70). Digital images of fluorescence and Nomarski interference were acquired on a microscope (Axiophot; Carl Zeiss, Inc.) with a 63× immersion objective and a 14-bit camera (Axiocam), and were transferred to a computer workstation running imaging software (Axiovision) (70).

Preparative immunoisolation of P epitope–bearing proteins and internal peptide sequence analysis

A presynaptosomal membrane fraction (P2) prepared from the brains of 50 rats was solubilized with lysis buffer A and used for immunoprecipitation of P-bearing proteins by adding 400 μg of affinity-purified anti-P antibody previously bound to 100 mg of protein A–sepharose for 2 h at 4°C. The immunocomplexes were exhaustively washed for 24 h at 4°C, resolved in preparative 7.5% SDS-PAGE, and stained with Coomassie blue. Relevant bands were isolated and treated for matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (TofSpec 2E; Micromass) and analysis (Protein Prospector, available at http://www.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/prospect.htm). The most abundant mass peaks were subjected to electrospray ionization for mass spectrometric sequencing (ESI-MS/MS; QT [Micromass]). In addition, peptide sequences were obtained by Edman's degradation at the Max-Delbrück-Center.

Rat brain immunohistochemistry

Male Sprague-Dawley rats were deeply anaesthetized, and the brains were fixed and processed for immunohistochemistry exactly as previously described (71), using 12 μg/ml of the affinity-purified anti-NSPA antibody or 1:500 dilution of anticleaved caspase-3 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). The sections were incubated with the secondary antibody (1:1,000 dilution) of Biotin-SP–conjugated AffiniPure goat anti–rabbit IgG (H+L; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Preadsorption of the anti-P antisera with the peptide K-2876THMEYGLFEDV2886 was used to control specificity.

Surgery and stereotaxis

Animal handling and care were performed according to the recommendations of the National Institutes of Health Guide for Animal Experimentation Care. The Commission on Bioethics and Biosafety of the Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile approved the study protocols. Adult Male Sprague-Dawley rats were anesthetized with 0.01%/100 g ketamine, placed in a stereotaxic frame, and bilaterally injected in the primary motor cortex with 0.7 μg of affinity-purified human anti-P antibody in 1 μl of sterile PBS, according to coordinates measured from bregma (72): anteroposterior, 1 mm; lateral, 2 mm; and horizontal, 1 mm from the skull. The rats (n = 4) were killed 24 h after lesion. As a control, rats were bilaterally injected with 0.7 μg of human IgG antibody purified by adsorption to protein A–sepharose.

Intracellular calcium levels

Confocal microscopy was used to assess intracellular calcium in cortical neurons (400,000 cells plated on coverslips) loaded for 30 min with 5 μM Fluo-3 AM and Fura Red AM (Invitrogen), as previously described (67). Real-time fluorophore emissions were registered at room temperature (23–26°C) in an inverted laser-scanning confocal microscope (LSM5 PASCAL; Carl Zeiss, Inc.) with a 40× objective (numerical aperture, 1.3). Cultures were excited at 488 nm every 15–30s, or every 2 min in Fig. 8 A, and Fluo-3 AM and Fura Red AM were imaged simultaneously. A ratio (R) minus background (ΔR) was calculated between the green (Fluo-3 AM) and red (Fura Red AM) emissions, which is proportional to the concentration of cytosolic calcium. Data are presented as ΔR/Ro, where Ro is the ratio at the beginning of each experiment.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 depicts the results obtained with anti-P antibodies affinity purified from SLE patients without NP symptoms. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20071285/DC1.

Supplemental Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jorge Garrido for his useful comments and suggestions to improve this manuscript. This work was approved by the Investigational Ethical Review Board of the Facultad de Medicina, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

This work received financial support from FONDAP (grant 13980001), Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (doctoral grant 2990025 to P.V. Burgos), a doctoral fellowship from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (to S. Matus and P.V. Burgos), and the Millennium Institute for Fundamental and Applied Biology, financed in part by the Ministerio de Planificación y Cooperación de Chile.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Abbreviations used: α-hP11 and α-hP4, affinity-purified human anti-P against a synthetic P peptide of 11 or 4 residues, respectively; anti-P, antiribosomal-P protein; BBB, blood–brain barrier; CNS, central nervous system; NMDAR,N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor; NP, neuropsychiatric; NSPA, neuronal surface P antigen; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

S. Matus and P.V. Burgos contributed equally to this study.

P.V. Burgos's present address is Cell Biology and Metabolism Branch, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892.

References

- 1.Sherer, Y., A. Gorstein, M.J. Fritzler, and Y. Shoenfeld. 2004. Autoantibody explosion in systemic lupus erythematosus: more than 100 different antibodies found in SLE patients. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 34:501–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.West, S.G. 2007. The nervous system. In Dubois' Lupus Erythematosus. Seventh edition. D.J. Wallace and B.H. Hahn, editors. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia. 707–746.

- 3.Hanly, J.G., A. Kuznetsova, and J.D. Fisk. 2007. Psychopathology of lupus and neuroimaging. In Dubois' Lupus Erythematosus. Seventh edition. D.J. Wallace and B.H. Hahn, editors. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia. 747–774.

- 4.Hanly, J.G., M.B. Urowitz, J. Sanchez-Guerrero, S.C. Bae, C. Gordon, D.J. Wallace, D. Isenberg, G.S. Alarcon, A. Clarke, S. Bernatsky, et al. 2007. Neuropsychiatric events at the time of diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus: an international inception cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 56:265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karassa, F.B., A. Afeltra, A. Ambrozic, D.M. Chang, F. De Keyser, A. Doria, M. Galeazzi, S. Hirohata, I.E. Hoffman, M. Inanc, et al. 2006. Accuracy of anti-ribosomal P protein antibody testing for the diagnosis of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus: an international meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 54:312–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanly, J.G. 2005. Neuropsychiatric lupus. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 31:273–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kozora, E., L.L. Thompson, S.G. West, and B.L. Kotzin. 1996. Analysis of cognitive and psychological deficits in systemic lupus erythematosus patients without overt central nervous system disease. Arthritis Rheum. 39:2035–2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senecal, J.L., and Y. Raymond. 2004. The pathogenesis of neuropsychiatric manifestations in systemic lupus erythematosus: a disease in search of autoantibodies, or autoantibodies in search of a disease? J. Rheumatol. 31:2093–2098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nived, O., G. Sturfelt, M.H. Liang, and P. De Pablo. 2003. The ACR nomenclature for CNS lupus revisited. Lupus. 12:872–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez-Crespo, M.R., F.J. Blanco, A. Ramos, E. Ciruelo, I. Mateo, M.A. Lopez Pino, and J.J. Gomez-Reino. 1995. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain in systemic lupus erythematosus. Br. J. Rheumatol. 34:1055–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonfa, E., J.L. Chu, N. Brot, and K.B. Elkon. 1987. Lupus anti-ribosomal P peptide antibodies show limited heterogeneity and are predominantly of the IgG1 and IgG2 subclasses. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 45:129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurki, P., T. Helve, D. Dahl, and I. Virtanen. 1986. Neurofilament antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Rheumatol. 13:69–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams, R.C., Jr., K. Sugiura, and E.M. Tan. 2004. Antibodies to microtubule-associated protein 2 in patients with neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 50:1239–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omdal, R., K. Brokstad, K. Waterloo, W. Koldingsnes, R. Jonsson, and S.I. Mellgren. 2005. Neuropsychiatric disturbances in SLE are associated with antibodies against NMDA receptors. Eur. J. Neurol. 12:392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lapteva, L., M. Nowak, C.H. Yarboro, K. Takada, T. Roebuck-Spencer, T. Weickert, J. Bleiberg, D. Rosenstein, M. Pao, N. Patronas, et al. 2006. Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antibodies, cognitive dysfunction, and depression in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 54:2505–2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conti, F., C. Alessandri, D. Bompane, M. Bombardieri, F.R. Spinelli, A.C. Rusconi, and G. Valesini. 2004. Autoantibody profile in systemic lupus erythematosus with psychiatric manifestations: a role for anti-endothelial-cell antibodies. Arthritis Res. Ther. 6:R366–R372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bluestein, H.G. 1997. Antibodies to brain. In Dubois' Lupus Erythematosus. Fifth edition. D.J. Wallace and B.H. Hahn, editors. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore. 517–522.

- 18.Whitney, K.D., and J.O. McNamara. 1999. Autoimmunity and neurological disease: antibody modulation of synaptic transmission. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 22:175–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeGiorgio, L.A., K.N. Konstantinov, S.C. Lee, J.A. Hardin, B.T. Volpe, and B. Diamond. 2001. A subset of lupus anti-DNA antibodies cross-reacts with the NR2 glutamate receptor in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Med. 7:1189–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kowal, C., L.A. DeGiorgio, T. Nakaoka, H. Hetherington, P.T. Huerta, B. Diamond, and B.T. Volpe. 2004. Cognition and immunity; antibody impairs memory. Immunity. 21:179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huerta, P.T., C. Kowal, L.A. DeGiorgio, B.T. Volpe, and B. Diamond. 2006. Immunity and behavior: antibodies alter emotion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:678–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kowal, C., L.A. DeGiorgio, J.Y. Lee, M.A. Edgar, P.T. Huerta, B.T. Volpe, and B. Diamond. 2006. From the cover: human lupus autoantibodies against NMDA receptors mediate cognitive impairment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:19854–19859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elkon, K.B., A.P. Parnassa, and C.L. Foster. 1985. Lupus autoantibodies target ribosomal P proteins. J. Exp. Med. 162:459–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francoeur, A.M., C.L. Peebles, K.J. Heckman, J.C. Lee, and E.M. Tan. 1985. Identification of ribosomal protein autoantigens. J. Immunol. 135:2378–2384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebert, T., J. Chapman, and Y. Shoenfeld. 2005. Anti-ribosomal P-protein and its role in psychiatric manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: myth or reality? Lupus. 14:571–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teh, L.S., and D.A. Isenberg. 1994. Antiribosomal P protein antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. A reappraisal. Arthritis Rheum. 37:307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stafford, H.A., C.J. Anderson, and M. Reichlin. 1995. Unmasking of anti-ribosomal P autoantibodies in healthy individuals. J. Immunol. 155:2754–2761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan, Z.J., C.J. Anderson, and H.A. Stafford. 1998. Anti-idiotypic antibodies prevent the serologic detection of antiribosomal P autoantibodies in healthy adults. J. Clin. Invest. 102:215–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonfa, E., S.J. Golombek, L.D. Kaufman, S. Skelly, H. Weissbach, N. Brot, and K.B. Elkon. 1987. Association between lupus psychosis and anti-ribosomal P protein antibodies. N. Engl. J. Med. 317:265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reichlin, M. 2006. Autoantibodies to the ribosomal P proteins in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Exp. Med. 6:49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneebaum, A.B., J.D. Singleton, S.G. West, J.K. Blodgett, L.G. Allen, J.C. Cheronis, and B.L. Kotzin. 1991. Association of psychiatric manifestations with antibodies to ribosomal P proteins in systemic lupus erythematosus. Am. J. Med. 90:54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isshi, K., and S. Hirohata. 1996. Association of anti-ribosomal P protein antibodies with neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 39:1483–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Massardo, L., P. Burgos, M.E. Martinez, R. Perez, M. Calvo, J. Barros, A. Gonzalez, and S. Jacobelli. 2002. Antiribosomal P protein antibodies in Chilean SLE patients: no association with renal disease. Lupus. 11:379–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshio, T., D. Hirata, K. Onda, H. Nara, and S. Minota. 2005. Antiribosomal P protein antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid are associated with neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Rheumatol. 32:34–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golombek, S.J., F. Graus, and K.B. Elkon. 1986. Autoantibodies in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 29:1090–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katzav, A., I. Solodeev, O. Brodsky, J. Chapman, C.G. Pick, M. Blank, W. Zhang, M. Reichlin, and Y. Shoenfeld. 2007. Induction of autoimmune depression in mice by anti-ribosomal P antibodies via the limbic system. Arthritis Rheum. 56:938–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reichlin, M. 2003. Ribosomal P antibodies and CNS lupus. Lupus. 12:916–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerli, R., L. Caponi, A. Tincani, R. Scorza, M.G. Sabbadini, M.G. Danieli, V. De Angelis, M. Cesarotti, M. Piccirilli, R. Quartesan, et al. 2002. Clinical and serological associations of ribosomal P autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus: prospective evaluation in a large cohort of Italian patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 41:1357–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elkon, K., E. Bonfa, R. Llovet, W. Danho, H. Weissbach, and N. Brot. 1988. Properties of the ribosomal P2 protein autoantigen are similar to those of foreign protein antigens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 85:5186–5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koren, E., M.W. Reichlin, M. Koscec, R.D. Fugate, and M. Reichlin. 1992. Autoantibodies to the ribosomal P proteins react with a plasma membrane-related target on human cells. J. Clin. Invest. 89:1236–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koscec, M., E. Koren, M. Wolfson-Reichlin, R.D. Fugate, E. Trieu, I.N. Targoff, and M. Reichlin. 1997. Autoantibodies to ribosomal P proteins penetrate into live hepatocytes and cause cellular dysfunction in culture. J. Immunol. 159:2033–2041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salazar, G., and A. Gonzalez. 2002. Novel mechanism for regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor endocytosis revealed by protein kinase A inhibition. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13:1677–1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bravo-Zehnder, M., P. Orio, A. Norambuena, M. Wallner, P. Meera, L. Toro, R. Latorre, and A. Gonzalez. 2000. Apical sorting of a voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ channel alpha-subunit in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells is independent of N-glycosylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:13114–13119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burgos, P.V., C. Klattenhoff, E. de la Fuente, A. Rigotti, and A. Gonzalez. 2004. Cholesterol depletion induces PKA-mediated basolateral-to-apical transcytosis of the scavenger receptor class B type I in MDCK cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:3845–3850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zurzolo, C., A. Le Bivic, A. Quaroni, L. Nitsch, and E. Rodriguez-Boulan. 1992. Modulation of transcytotic and direct targeting pathways in a polarized thyroid cell line. EMBO J. 11:2337–2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagy, A., and A.V. Delgado-Escueta. 1984. Rapid preparation of synaptosomes from mammalian brain using nontoxic isoosmotic gradient material (Percoll). J. Neurochem. 43:1114–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castle, J.D. 1995. Extraction of extrinsic proteins from membrane using sodium carbonate. In Current Protocols in Protein Science. J.E. Coligan, B.M. Dann, H.L. Ploegh, D.W. Speicher, and P.T. Wingfield, editors. John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York. 42–43.

- 48.Ishikawa, K., T. Nagase, D. Nakajima, N. Seki, M. Ohira, N. Miyajima, A. Tanaka, H. Kotani, N. Nomura, and O. Ohara. 1997. Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. VIII. 78 new cDNA clones from brain which code for large proteins in vitro. DNA Res. 4:307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ott, C.M., and V.R. Lingappa. 2002. Integral membrane protein biosynthesis: why topology is hard to predict. J. Cell Sci. 115:2003–2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elofsson, A., and G. von Heijne. 2007. Membrane protein structure: prediction versus reality. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76:125–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hasler, P., N. Brot, H. Weissbach, W. Danho, Y. Blount, J.L. Zhou, and K.B. Elkon. 1994. The effect of phosphorylation and site-specific mutations in the immunodominant epitope of the human ribosomal P proteins. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 72:273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mahler, M., K. Kessenbrock, J. Raats, R. Williams, M.J. Fritzler, and M. Bluthner. 2003. Characterization of the human autoimmune response to the major C-terminal epitope of the ribosomal P proteins. J. Mol. Med. 81:194–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mahler, M., K. Kessenbrock, J. Raats, and M.J. Fritzler. 2004. Technical and clinical evaluation of anti-ribosomal P protein immunoassays. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 18:215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lopez Bergami, P., P. Mateos, J. Hoebeke, M.J. Levin, and A. Baldi. 2003. Sequence analysis, expression, and paratope characterization of a single-chain Fv fragment for the eukaryote ribosomal P proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 301:819–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schwaber, J.S., C. Sternini, N.C. Brecha, W.T. Rogers, and J.P. Card. 1988. Neurons containing calcitonin gene-related peptide in the parabrachial nucleus project to the central nucleus of the amygdala. J. Comp. Neurol. 270:416–426, 398–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Orrenius, S., B. Zhivotovsky, and P. Nicotera. 2003. Regulation of cell death: the calcium-apoptosis link. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4:552–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pisetsky, D.S. 2006. Fulfilling Koch's postulates of autoimmunity: anti-NR2 antibodies in mice and men. Arthritis Rheum. 54:2349–2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McGaugh, J.L. 2004. The amygdala modulates the consolidation of memories of emotionally arousing experiences. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27:1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kandel, E., I. Kupfermann, and S. Iversen. 2000. Learning and memory. In Principles of Neural Science. E. Kandel, J. Schwartz, and T. Jessell, editors. Elsevier Science Publishing Co. Inc., New York. 1227–1246.

- 60.Kauer, J.A. 2004. Learning mechanisms in addiction: synaptic plasticity in the ventral tegmental area as a result of exposure to drugs of abuse. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 66:447–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abbott, N.J., L.L. Mendonca, and D.E. Dolman. 2003. The blood-brain barrier in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 12:908–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hawkins, B.T., and T.P. Davis. 2005. The blood-brain barrier/neurovascular unit in health and disease. Pharmacol. Rev. 57:173–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Albert, M.L., and R.B. Darnell. 2004. Paraneoplastic neurological degenerations: keys to tumour immunity. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 4:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rogers, S.W., P.I. Andrews, L.C. Gahring, T. Whisenand, K. Cauley, B. Crain, T.E. Hughes, S.F. Heinemann, and J.O. McNamara. 1994. Autoantibodies to glutamate receptor GluR3 in Rasmussen's encephalitis. Science. 265:648–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sillevis Smitt, P., A. Kinoshita, B. De Leeuw, W. Moll, M. Coesmans, D. Jaarsma, S. Henzen-Logmans, C. Vecht, C. De Zeeuw, N. Sekiyama, et al. 2000. Paraneoplastic cerebellar ataxia due to autoantibodies against a glutamate receptor. N. Engl. J. Med. 342:21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fetissov, S.O., J. Harro, M. Jaanisk, A. Jarv, I. Podar, J. Allik, I. Nilsson, P. Sakthivel, A.K. Lefvert, and T. Hokfelt. 2005. Autoantibodies against neuropeptides are associated with psychological traits in eating disorders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:14865–14870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Loaiza, A., O.H. Porras, and L.F. Barros. 2003. Glutamate triggers rapid glucose transport stimulation in astrocytes as evidenced by real-time confocal microscopy. J. Neurosci. 23:7337–7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Banker, G., and K. Goslin. 1991. Rat hippocampal neurons in low density culture. In Culturing Nerve Cells. G. Banker and K. Goslin, editors. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. 251–282.

- 69.De Ferrari, G.V., R. von Bernhardi, F.H. Calderon, S.C. Luza, and N.C. Inestrosa. 1998. Responses induced by tacrine in neuronal and non-neuronal cell lines. J. Neurosci. Res. 52:435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carcamo, C., E. Pardo, C. Oyanadel, M. Bravo-Zehnder, P. Bull, M. Caceres, J. Martinez, L. Massardo, S. Jacobelli, A. Gonzalez, and A. Soza. 2006. Galectin-8 binds specific beta1 integrins and induces polarized spreading highlighted by asymmetric lamellipodia in Jurkat T cells. Exp. Cell Res. 312:374–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meynard, M.M., J.L. Valdes, M. Recabarren, M. Seron-Ferre, and F. Torrealba. 2005. Specific activation of histaminergic neurons during daily feeding anticipatory behavior in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 158:311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paxinos, G., and C. Watson. 1986. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Second edition. Academic Press Inc., San Diego. 264 pp.

- 73.Gainetdinov, R.R., S.R. Jones, F. Fumagalli, R.M. Wightman, and M.G. Caron. 1998. Re-evaluation of the role of the dopamine transporter in dopamine system homeostasis. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 26:148–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.