Abstract

The iab-4 noncoding RNA from the Drosophila bithorax complex is the substrate for a microRNA (miRNA). Gene conversion was used to delete the hairpin precursor of this miRNA; flies homozygous for this deletion are sterile. Surprisingly, this mutation complements with rearrangement breakpoint mutations that disrupt the iab-4 RNA but fails to complement with breaks mapping in the iab-5 through iab-7 regulatory regions. These breaks disrupt the iab-8 RNA, transcribed from the opposite strand. This iab-8 RNA also encodes a miRNA, detected on Northern blots, derived from the hairpin complementary to the iab-4 precursor hairpin. Ultrabithorax is a target of both miRNAs, although its repression is subtle in both cases.

[Keywords: Ultrabithorax, noncoding RNA, abdominal-A, iab-8 RNA]

It has long been known that there are many noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) made from the bithorax complex (BX-C) in addition to the mRNAs encoding the three homeobox transcription factors. Some of these ncRNAs have been recovered from cDNA libraries (Lipshitz et al. 1987; Cumberledge et al. 1990), and many more have been detected by in situ hybridization to RNA in embryos (Sánchez-Herrero and Akam 1989; Bae et al. 2002). It has not been possible to assign any function to these ncRNAs, although there has been speculation that they may set the state of Polycomb Response Elements (Bender and Fitzgerald 2002; Hogga and Karch 2002; Rank et al. 2002; Schmitt et al. 2005).

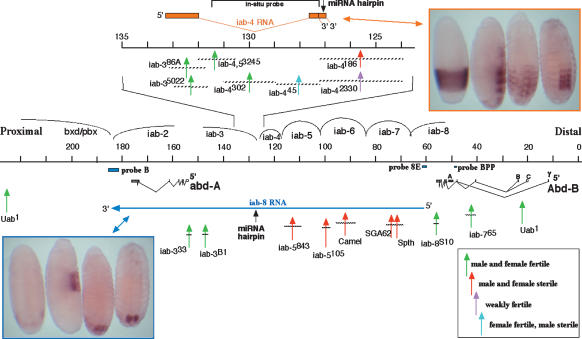

Aravin et al. (2003) characterized a large number of microRNA (miRNA) clones prepared from Drosophila RNA at a variety of developmental stages. Two of these clones matched sequences from the BX-C, mapping to the 3′ end of a ncRNA discovered by Cumberledge et al. (1990) (Fig. 1). This ncRNA was called the “iab-4 RNA,” because it was thought to come from the iab-4 segmental domain of the BX-C, and the miRNAs were named miR-iab-4 5p (five prime) and miR-iab-4 3p (three prime). More recent mapping of segmental domains (Bender and Hudson 2000) has shown that the RNA actually lies in the iab-3 domain (regulating parasegment 8), and indeed, the ncRNA is expressed from parasegment 8 through parasegment 12 (Fig. 1; Cumberledge et al. 1990). However, the iab-4 nomenclature is maintained here to avoid confusion with the designations in other studies. Two cDNA clones for the iab-4 RNA were described by Cumberledge et al. (1990), with alternate 3′ poly(A) sites separated by 304 base pairs (bp). The two miRNAs come from this region between these two poly(A) sites; both are presumably derived from a 70-base hairpin RNA precursor predicted from the sequence (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

The abdominal half of the BX-C, showing iab-4 and iab-8 ncRNAs, and the rearrangement breakpoints tested for complementation. The horizontal black line marks the sequence coordinates, following the convention of Martin et al. (1995). The 10-kb region covering the iab-4 ncRNA transcription unit is expanded above. The iab-4 transcription unit is diagrammed in orange, and embryos stained for the iab-4 RNA are in the orange box (at top right). The iab-8 transcription unit is diagrammed with the long blue arrow in the bottom half of the figure. Probes B, 8E, and BPP were used to detect the iab-8 RNA in prior studies (see Results and Discussion). Embryos stained for the iab-8 RNA are in the blue box (at bottom left). Embryos are shown at stages 5 or 6 (for iab-4 or iab-8 RNAs), stage 10, stage 13, and stage 15 (Campos-Ortega and Hartenstein 1985). The 4.2-kb fragment used for making both strand-specific probes is shown at the top. Vertical arrows indicate the positions of rearrangement breaks relative to the maps; the horizontal bars on these arrows indicate the region of uncertainty for each break. Breakpoint chromosomes that gave sterile flies when heterozygous with the ΔmiRNA conversion chromosome are shown with red arrows. Breakpoints that were fertile are shown in green. Note that four breakpoints upstream of the miRNA hairpin in the iab-4 RNA are fertile; five breakpoints upstream of the hairpin in the iab-8 RNA are sterile. Two breakpoints closely flanking the site of the miRNA hairpin gave distinctive results, as indicated in pink and blue.

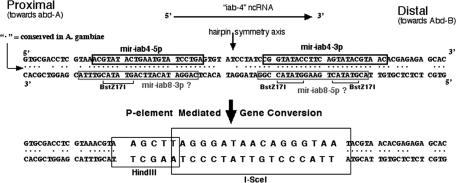

Figure 2.

DNA sequences of the wild-type miR-iab-4 precursor region and of the ΔmiRNA derivative. The black boxes on the top strand indicate the miR-iab-4 5p and miR-iab-4 3p sequences reported by Aravin et al. (2003). The gray boxes on the bottom strand indicate the hypothetical sequences of miR-iab-8 5p and miR-iab-8 3p, assuming they are near homologs to the known miRNAs from the top strand. The actual miR-iab-8 5p sequence is slightly shifted from this prediction (Stark et al. 2008), and miR-iab-8 3p has not been detected to date. Dots between the top and bottom strands mark the base pairs conserved in the mosquito. The BstZ17I restriction sites were used to replace most of the hairpin region with sequences for the HindIII and I-SceI restriction enzymes.

A recent study (Ronshaugen et al. 2005) suggested that the miR-iab-4 5p miRNA might be responsible for repression of Ubx in the abdominal segments where the miRNA is expressed. The conclusion was based on experiments in which miR-iab-4 5p was expressed at high levels in tissues, including the wing and haltere discs, where miR-iab-4 5p is not normally found. However, the pattern of UBX expression in PS8, where the miRNA is expressed, is very similar to the UBX pattern in PS7, which lacks the miRNA. The obvious repression of Ubx in both of these parasegments is clearly dependent on abd-A; any effect of miR-iab-4 5p must be subtle or redundant. Moreover, misexpression of miRNAs in other systems have been shown to give misleading effects (Bushati and Cohen 2007). The function of miR-iab-4 5p can best be examined by mutating or deleting the miRNA.

Prior studies characterized a large number of P element insertions in the BX-C (Bender and Hudson 2000; Fitzgerald and Bender 2001), including one called HCJ200, which maps only ∼200 bp proximal to the miRNAs. This provided the opportunity to mutate the miRNAs by P-element-mediated gene conversion (Nassif et al. 1994). Loss of the miRNAs derived from the iab-4 ncRNA causes no apparent morphological or behavioral phenotype, but the analysis revealed a functional miRNA derived from the opposite strand.

Results and Discussion

Gene conversion

A 3.7-kb conversion donor fragment was constructed with a mutated version of the miRNA precursor sequence. The precursor sequence is symmetrically cut by the BstZ17I restriction endonuclease; this permitted the replacement of most of the precursor sequence with a double-stranded oligonucleotide-containing sites for the HindIII and I-SceI endonucleases (Fig. 2). A plasmid with the donor sequence and a plasmid to supply P-element transposase were both injected into embryos with the HCJ200 (rosy+) P insertion. Offspring from the injected individuals were screened for loss of the HCJ200 P element (i.e., rosy−), and progeny from these exceptional flies were screened by PCR for a change in the size of the genomic DNA at the site of the insertion. One of 86 fertile injected animals gave the expected convertants. The conversion events were verified by sequencing the PCR product, and by whole-genome Southern blots. Genomic DNA was cut with HindIII, which cuts the oligonucleotide introduced in the conversion but does not cut the wild-type sequence within the 3.7-kb donor fragment. The sizes of the HindIII fragments on the Southern blot confirmed that the donor sequence was at the expected position in the BX-C and not at another genomic location.

Phenotype

Flies homozygous for the conversion chromosome (henceforth called “ΔmiRNA”) appeared normal. In particular, no evidence of segmental transformation was seen in mounted adult abdominal cuticles of either sex. However, both sexes were sterile. Females had ovaries with eggs of normal size, but only very rare individuals ever laid an egg, even after mating with wild-type males, and these rare eggs never hatched. Males had morphologically normal testes containing motile sperm. In single-fly tests for mating behavior, ΔmiRNA homozygous females mated with wild-type males as readily as their heterozygous siblings. The ΔmiRNA homozygous males showed normal courtship behavior toward wild-type females, except that they never completed copulation. The mutant males mounted the females, but they did not bend their abdomens quite far enough to mate. Thus, the sterility in both sexes appeared to be behavioral, due to a defect in the nerves or muscles required to lay eggs or to curl the abdomen.

Complementation

The ΔmiRNA mutation was tested for complementation with rearrangement mutations in the BX-C, including several that should disrupt the iab-4 RNA transcript upstream of the position of the miRNA precursor. Surprisingly, breaks disrupting the iab-4 transcription unit complemented with ΔmiRNA—i.e., trans-heterozygotes were fertile (Fig. 1). Thus, the iab-4 RNA is not the precursor for any miRNA that is responsible for fertility. In contrast, rearrangements distal to the position of the miRNAs failed to complement, even with breaks >50 kb distal (Fig. 1). Assuming that noncomplementing rearrangements are upstream in the precursor, one can deduce that the precursor is transcribed distal to proximal on the chromosome, and that the miRNA responsible for fertility comes from the opposite strand to those detected by Aravin et al. (2003). Similarly, one would predict that the precursor transcript for the fertility miRNA spans at least the iab-7 through the iab-3 segmental domains.

Several studies have detected such a transcript (Sánchez-Herrero and Akam 1989; Zhou et al. 1999; Bae et al. 2002; Bender and Fitzgerald 2002), which is usually called the iab-8 ncRNA. It has been detected and mapped solely by in situ hybridization to RNA in embryos, although the complementation analysis (Fig. 1) now corroborates the in situ mapping, at least for the iab-4 through iab-7 region. Its start site is near Abd-B; it was detected by probes 4 kb proximal to the 3′ end of the Abd-B transcripts (Fig. 1; probe 8E of Bae et al. 2002; probe IAB8 of Zhou et al. 1999). Zhou et al. (1999) defined a potential promoter for the iab-8 transcript, which lies ∼5 kb downstream from Abd-B, although their evidence did not preclude a start site further upstream. Bae et al. (2002) detected the iab-8 RNA upstream of the Abd-B class A RNA start site (the “BPP” probe, Fig. 1), suggesting a more distal start site. However, hybridization to the Abd-B class B RNA in the ninth abdominal segment (PS14) (Boulet et al. 1991; Kuhn et al. 1993) could have been mistaken for the iab-8 RNA pattern. Moreover, the iab-8S10 breakpoint, just proximal to Abd-B, does complement the sterility phenotype of ΔmiRNA, and so the promoter for the iab-8 fertility function should be to the left of that break.

At the 3′ end, the iab-8 RNA extends through abd-A. The iab-8 RNA in situ pattern was detected by a probe 5.5 kb proximal to the 3′ end of the abd-A poly(A) site (Fig. 1; probe “B” of Bender and Fitzgerald 2002; D. Fitzgerald and W. Bender, unpubl.). Thus the transcription unit spans at least 120 kb. The iab-8 RNA has not been detected by probes in the bxd regulatory region, further proximal to abd-A (B. Pease, D. Fitzgerald, and W. Bender, unpubl.).

The iab-8 transcript initiates at the cellular blastoderm stage (Zhou et al. 1999), as do most of the other embryonic ncRNAs (Akam et al. 1985; Cumberledge et al. 1990; Bae et al. 2002). However, it should take ∼45 min to transcribe to the position of the miRNA precursor hairpin, assuming a transcription speed of ∼1.3 kb/min (Mason and Struhl 2003). This would account for the developmental delay in the appearance of the RNA signal in Figure 1. The iab-8 RNA is located in the eighth abdominal segment and in more posterior segmental rudiments. In late embryos, the transcript persists in the posterior end of the ventral nerve chord (Fig. 1).

miRNAs on Northern blots

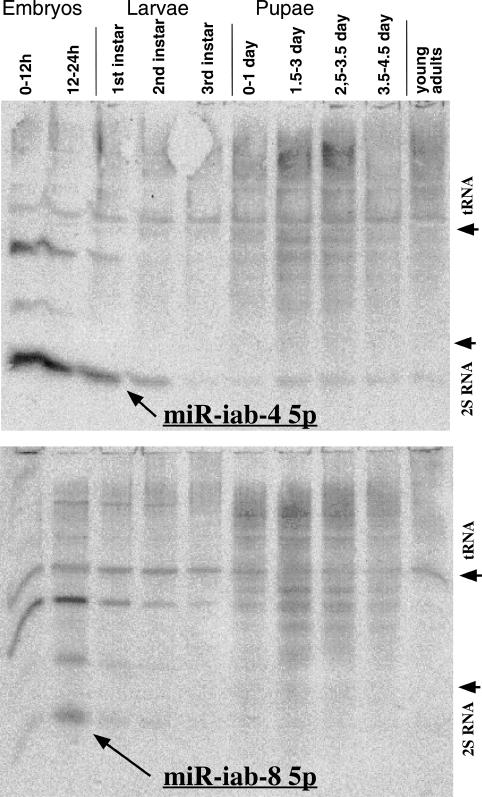

The complementation results predict a functional product from the part of the iab-8 RNA affected by the ΔmiRNA deletion. Northern blots were used to detect small RNAs from this region. Total RNA samples from various developmental stages of wild-type flies were separated on denaturing polyacrylamide gels and transferred to membranes. Probes were prepared against the expected miR-iab-4 5p and miR-iab-4 3p miRNAs, and also against the potential miRNAs that might be processed from the opposite strand (called miR-iab-8 5p and miR-iab-8 3p) (Fig. 2, gray boxes). The probe directed against miR-iab-4 5p gave a prominent band migrating at ∼24 bases (Fig. 3). There were also a variety of higher-molecular-weight products, especially in pupal RNA samples. The probe directed against miR-iab-4 3p showed the same higher-molecular-weight bands, but nothing in the 20- to 30-base range. The miR-iab-4 3p product was recovered in rare clones by two groups (Aravin et al. 2003; Stark et al. 2008), but it is too rare to be detected in these blots. The probe directed against miR-iab-8 5p gave a weak band in the ∼24-base region, as well as higher-molecular-weight bands (Fig. 3). The probe against miR-iab-8 3p gave only the high-molecular-weight bands. (Hereafter, miR-iab-4 5p will be abbreviated as miR-iab-4, and miR-iab-8 5p will be abbreviated as miR-iab-8.) The miR-iab-8 product is the obvious candidate for the fertility phenotype. Since the miR-iab-8 signal was about five times weaker than that from the miR-iab-4 product, the miR-iab-8 miRNA must be quite rare, as one might expect from the limited expression pattern of the iab-8 RNA precursor. Since the miR-iab-4 and miR-iab-8 have very similar sequences (Fig. 2), it seemed possible that the weaker miR-iab-8 signal might be due to cross-hybridization. However, the miR-iab-8 band migrated slightly more slowly than the miR-iab-4 band in adjacent lanes, and this migration difference was verified by stripping a miR-iab-8 Northern blot and rehybridizing with the probe to miR-iab-4.

Figure 3.

Developmental Northern blots. The probe for the top panel was directed against miR-iab-4 5p and for the bottom panel, against miR-iab-8 5p. Total RNA was extracted from wild-type (Canton S) animals at the indicated stages and separated on an 11% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The migration positions of Drosophila tRNA and 2S RNA are indicated.

Potential targets in the BX-C

It is difficult to predict the possible targets of miRNAs solely on the basis of sequence information because of the possibilities for mismatches and loop-outs in the miRNA/target duplex. In two initial studies of potential Drosophila miRNA targets (Stark et al. 2003; Enright et al. 2003), the rank orders of the predicted targets of miR-iab4 were discordant, presumably because the search algorithms were somewhat different. The homeotic transcription factors of the BX-C, UBX, ABD-A, and ABD-B, all had credible pairing sites in the 3′ untranslated regions of their mRNAs, and, although these genes were not high on either list of targets, monoclonal antibodies were available for all three products.

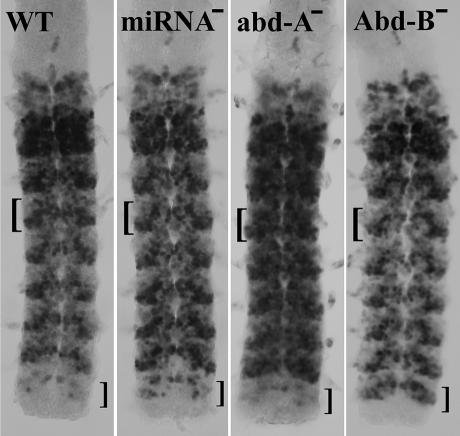

Embryos homozygous for the ΔmiRNA mutation showed no apparent changes in the patterns of ABD-A and ABD-B, but there were subtle differences in the UBX pattern (Fig. 4). UBX is expressed strongly and comprehensively in the cells of parasegment 6 (PS6, primarily the first abdominal segment). In the second abdominal segment (PS7), ABD-A appears and turns off UBX, especially in the more anterior cells of the parasegment. In the more posterior segments, the UBX staining pattern weakens progressively, and the ABD-A pattern becomes somewhat stronger (Karch et al. 1990). However, in ΔmiRNA embryos, the UBX pattern is nearly constant from PS7 through PS12 (Fig. 4). Thus, the progressive posterior decline in wild-type embryos appears not to be caused by ABD-A or ABD-B but rather by miR-iab-4 5p, whose expression shows a progressive posterior increase in PS8–12 (Fig. 1).

Figure 4.

UBX protein expression in the CNS of stage 15 embryos (∼12 h old). The brackets to the left of each nerve chord mark the region of the third abdominal segment (PS8), and the brackets to the right mark the eighth abdominal segment (PS13). The miRNA− embryo, lacking both miR-iab-4 and miR-iab-8 (ΔmiRNA homozygous), shows more uniform staining for UBX in the third through seventh abdominal segments, and ectopic staining in a few cells of the eighth abdominal segment. The repression of Ubx by ABD-A is much more dramatic, as illustrated in the abd-A− homozygote (using the abd-AD100.24 point mutation). Likewise, an Abd-B− homozygote (the HCJ199ry− mutation, a P-element insertion in the first exon of the Type I Abd-B mRNA) derepresses Ubx in the eighth abdominal segment much more dramatically than does miR-iab-8.

In the eighth abdominal segment (PS13) of a wild-type embryo, UBX is almost completely absent in both the epidermis and the CNS. Homozygotes for ΔmiRNA show a partial derepression of UBX in the CNS in PS13 (Fig. 4). The derepression is similar in pattern and intensity to that seen in AbdB−/+ heterozygotes (data not shown). The repression of Ubx could be indirect; miR-iab-8 could be a positive regulator of Abd-B (and miR-iab-4 a positive regulator of abd-A). But all known targets of miRNAs are negatively regulated, and so it seems more likely that both miRNAs directly regulate Ubx.

It is possible that the effects of these two miRNAs are masked by functional redundancy with abd-A (for miR-iab-4) and Abd-B (for miR-iab-8). Embryos lacking ABD-A (but retaining miR-iab-4) show a dramatic derepression of UBX in the second through seventh abdominal segments (Fig. 4). There does appear to be a slight decline in UBX levels in the more posterior segments, which could be attributed to miR-iab-4 repression. A complete analysis would include the UBX expression in embryos lacking both abd-A and miR-iab-4, but that will require construction of an abd-A, ΔmiRNA double mutant chromosome. In any case, miR-iab-4 repression of Ubx is subtle, even in the absence of ABD-A. Similarly, in an Abd-B homozygous mutant embryo (retaining miR-iab-8), UBX expression in the eighth abdominal segment closely resembles that in the seventh (Fig. 4). Again, a ΔmiRNA, Abd-B double mutant chromosome would be useful for comparison, but again it is clear that the repression of Ubx by miR-iab-8 is still subtle in the absence of ABD-B. There is no reason to expect that Ubx is the only target of these miRNAs; perhaps other target genes will be discovered which the miRNAs repress more dramatically.

MiR-iab-8 is the first example of a functional product of a ncRNA in the BX-C. There are no other predicted miRNA precursor sequences in the iab-8 RNA or elsewhere in the BX-C (the Antennapedia complex includes miR-10), but there are many other ncRNAs. The possibility that they also include functional products now seems more likely.

Two accompanying studies (Stark et al. 2008; Tyler et al. 2008) also demonstrate the existence of miR-iab-8 (called miR-iab-4AS or miR-iab-4AS-5p). Stark et al. (2008) recovered multiple clones of miR-iab-8, and thus define its sequence. Both studies predict, from sequence analysis, that miR-iab-8 might regulate Ubx.

Materials and methods

Gene conversion

The conversion donor plasmid was constructed starting with a genomic 3665-bp PstI fragment cloned into Bluescript II KS+ (Strategene). This was cut with BstZ17I, and the gap was filled with a double-stranded oligonucleotide, as shown in Figure 2. The mutated genomic sequence was removed from the Bluescript backbone as an EcoR1–NotI fragment, and was transferred to the pP{whiteOut} vector (generously provided by Jeff Sekelsky). The injection procedure was designed to yield both P-element transformants and direct convertants; in case no convertants were recovered in the first round, a genomic P insertion could be used as the donor in a second attempt. DNA from the donor plasmid (at 400 μg/mL) along with DNA from a P transposase source (Δ2–3 wings clipped, 150 μg/mL) was injected into eggs laid by a HCJ200/MKRS fly stock. Surviving G0 progeny were singly mated to MKRS/TM2 ry flies, and the progeny were screened for ry− eye color. Twenty-three vials yielded ry− exceptional progeny; each of these F1 flies was again crossed to MKRS/TM2 ry flies to establish balanced stocks, and flies homozygous for the treated chromosome were collected for PCR tests. Primers were chosen flanking the conversion site to yield a 209-bp product from the wild-type sequence and 185 bp from the donor. Several G0 flies yielded progeny with two PCR bands, indicating a wild-type sequence at the BX-C plus a P-element insert at another location. One G0 vial yielded three ry− offspring with only one PCR band, of the size expected for the successful conversion.

Drosophila strains

The wild-type strain used for genetic crosses was cn1; ry502, which was the background for the HCJ200 P-element insertion. The rearrangement mutations designated iab-386A, iab-35022, iab-4186, iab-42330, iab4,53245, and iab-5843 were provided by E.B. Lewis. Lewis induced all of these alleles with X rays on a In(3R)81/90C chromosome; all were recovered in a screen for rearrangements that disrupted transvection in the BX-C. The lesions for these alleles were mapped by Southern blotting, using DNA from hemizygous flies. The other rearrangements in Figure 4 were described in Karch et al. (1985). The breakpoints for iab-4302 and iab-445 were remapped, and the positions are adjusted or refined relative to the previous coordinates.

Fertility assays

Single males to be tested were added to a vial with three or more wild-type virgin females; single test females were similarly mated with wild-type males. The vials were left for at least 5 d at 25°C, and were then examined for the presence of larvae. Ten males and 10 females were scored for the genotypes judged to be sterile. The iab-8S10 breakpoint, associated with a transposition to the Y chromosome, was only tested in males.

Northerns

RNA was from staged animals of the Canton S wild type, stored at −70°C. RNA was isolated as described previously (Ali and Bender 2004). Total RNA samples (50 μg each) were separated on an 11% vertical denaturing polyacrylamide gel, 1.5 mm thick. The gels were run at 7 V/cm for 10 h and then stained with ethidium bromide (0.2 μg/mL) in 0.5× TBE. The stained gels were photographed to locate the tRNA and 2S RNAs and to verify equal loading in each lane. The RNA was transferred electrophoretically (5 min, 10 V) to Zeta-Probe GT (Bio-Rad) and was subsequently cross-linked to the membrane by UV irradiation (120 mJ). The membranes were hybridized with probe in ULTRAhyb-Oligo buffer (Ambion) for 40 h at 35°C, and washed for 45 min in six changes of wash buffer (0.3 M sodium chloride, 20 mM sodium phosphate, 2 mM ethylenediamine–tetra-acetic acid, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at pH 7.4). 32P-labeled probes were prepared using the Starfire Oligonucleotide Labeling System (Integrated DNA Technologies). The probe sequences were CTCAGGA TACATTCAGTATACGTTTACGAGCTCGCAC (for miR-iab-4 5′), GTGCTCTCTCGTGTTACGTATACTGAAGGTATACCGGATAG (for miR-iab-4 3′), CTATCCGGTATACCTTCAGTATACGTAACACGA GAGAGCAC (for miR-iab-8 5′), and GTGCGACCTCGTAAACGTATA CTGAATGTATCCTGAG (for miR-iab-8 3′). The blots were scanned on a Fuji BAS2500 PhosphorImager. RNA size standards were prepared by in vitro transcription from a T7 polymerase promoter in a derivative of the Bluescript II KS+ plasmid (Strategene), with templates truncated to give 11-, 21-, 24-, and 40-base products. 32P-labeled transcription products were run next to Drosophila total RNA on a denaturing acrylamide gel, as above. Subsequent gels for Northerns were cross-calibrated with reference to the 2S RNA band (30 bases long) (Tautz et al. 1988).

RNA in situ hybridization and embryo staining

The production of digoxigenin-labeled probes and the hybridization of embryos was as described by Fitzgerald and Bender (2001), except that acetone treatment (Nagaso et al. 2001) was used instead of proteinase K for permeabilization of the embryos. For protein detection, embryos were fixed, stained, and dissected as described by Karch et al. (1990). Mouse monoclonals were obtained for UBX (FP.3.38 ascites) (White and Wilcox 1985), ABD-A (6A18.12 ascites) (Kellerman et al. 1990), ABD-B (1A2E9 supernatant) (Celniker et al. 1989), and β-galactosidase (Promega). HRP-coupled goat anti-mouse (Bio-Rad) was used as the secondary antibody. All antibodies were used at 1/500 or 1/1000 dilutions. The CNS were hand-dissected with tungsten needles and mounted in Immu-mount (Shandon). Homozygous ΔmiRNA embryos from ΔmiRNA/TM3,ftz-lacZ parents were recognized by the absence of lacZ antigen.

Acknowledgments

The collection of rearrangement breakpoints was made possible by the efforts and generosity of Ed Lewis. Angela Pattitucci provided protocols for miRNA Northerns. Tom Tuschl shared results and analysis prior to publication, as did Alex Stark. Dan Fitzgerald and Benjamin Pease assisted with the in situ hybridizations. Ian Duncan provided the monoclonal antibodies for UBX and ABD-A; Susan Celniker provided the Abd-B monoclonal. Benjamin Pease provided helpful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

PHONE (617) 432-1906; FAX (617) 738-0516.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1614208

References

- Akam M.E., Martinez-Arias A., Weinzierl R., Wilde C.D. Function and expression of ultrabithorax in the Drosophila embryo. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1985;50:195–200. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1985.050.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali J., Bender W. Cross-regulation among the Polycomb group genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:7737–7747. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7737-7747.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravin A.A., Lagos-Quintana M., Yalcin A., Zavolan M., Marks D., Snyder B., Gaasterland T., Meyer J., Tuschl T. The small RNA profile during Drosophila melanogaster development. Dev. Cell. 2003;5:337–350. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae E., Calhoun V.C., Levine M., Lewis E.B., Drewell R.A. Characterization of the intergenic RNA profile at abdominal-A and abdominal-B in the Drosophila bithorax complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99:16847–16852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222671299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender W., Fitzgerald D.P. Transcription activates repressed domains in the Drosophila bithorax complex. Development. 2002;129:4923–4930. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.4923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender W., Hudson A. P element homing to the Drosophila bithorax complex. Development. 2000;127:3981–3992. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.18.3981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulet A.M., Lloyd A., Sakonju S. Molecular definition of the morphogenetic and regulatory functions and the cis-regulatory elements of the Drosophila Abd-B homeotic gene. Development. 1991;111:393–405. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.2.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushati N., Cohen S.M. microRNA functions. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007;23:175–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Ortega J.A., Hartenstein V. The embryonic development of Drosophila melanogaster. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Celniker S.E., Keelan D.J., Lewis E.B. The molecular genetics of the bithorax complex of Drosophila: Characterization of the products of the Abdominal-B domain. Genes & Dev. 1989;3:1425–1437. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.9.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumberledge S., Zaratzian A., Sakonju S. Characterization of two RNAs transcribed from the cis-regulatory region of the abd-A domain within the Drosophila bithorax complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1990;87:3259–3263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright A., John B., Gaul U., Tuschl T., Sander C., Marks D. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 2003;5:R1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald D.P., Bender W.B. Polycomb group repression reduces DNA accessibility. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:6585–6597. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.19.6585-6597.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogga I., Karch F. Transcription through the iab-7 cis-regulatory domain of the bithorax complex interferes with Polycomb-mediated silencing. Development. 2002;129:4915–4922. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.4915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch F., Weiffenbach B., Peifer M., Bender W., Duncan I., Celniker S., Crosby M., Lewis E.B. The abdominal region of the bithorax complex. Cell. 1985;43:81–96. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch F., Weiffenbach B., Bender W. abdA expression in Drosophila embryos. Genes & Dev. 1990;4:1573–1587. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.9.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellerman K.a., Mattson D.M., Duncan I. Mutations affecting the stability of the fushi tarazu protein of Drosophila. Genes & Dev. 1990;4:1936–1950. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.11.1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn D.T., Mack J.A., Duan C., Packert G. Tumorous-head (tuh-1; tuh-3) modulates Abd-B bithorax-complex functions in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1993;133:593–604. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.3.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipshitz H.D., Peattie D.A., Hogness D.S. Novel transcripts from the Ultrabithorax domain of the bithorax complex. Genes & Dev. 1987;1:307–322. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C.H., Mayeda C.A., Davis C.A., Ericsson C.L., Knafels J.D., Mathog D.R., Celniker S.E., Lewis E.B., Palazzolo M.J. Complete sequence of the bithorax complex of Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995;92:8398–8402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason P.B., Struhl K. The FACT complex travels with elongating RNA polymerase II and is important for the fidelity of transcriptional initiation in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:8323–8333. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8323-8333.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaso H., Murata T., Day N., Yokoyama K.K. Simultaneous detection of RNA and protein by in situ hybridization and immunological staining. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2001;49:1177–1182. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassif N., Penny J., Pal S., Engels W.R., Gloor G.B. Efficient copying of nonhomologous sequences from ectopic sites via P-element-induced gap repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:1613–1625. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank G., Prestel M., Paro R. Transcription through intergenic chromosomal memory elements of the Drosophila bithorax complex correlates with an epigenetic switch. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:8026–8034. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.8026-8034.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronshaugen M., Biemar F., Piel J., Levine M., Lai E.C. The Drosophila microRNA iab-4 causes a dominant homeotic transformation of halteres to wings. Genes & Dev. 2005;19:2947–2952. doi: 10.1101/gad.1372505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Herrero E., Akam M. Spatially ordered transcription of regulatory DNA in the bithorax complex of Drosophila. Development. 1989;107:321–329. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt S., Prestel M., Paro R. Intergenic transcription through a Polycomb group response element counteracts silencing. Genes & Dev. 2005;19:697–708. doi: 10.1101/gad.326205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark A., Brennecke J., Russell R.B., Cohen S.M. Identification of Drosophila microRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark A., Bushati N., Jan C.H., Kheradpour P., Hodges E., Brennecke J., Bartel D.P., Cohen S.M., Kellis M. A single Hox locus in Drosophila produces functional microRNAs from opposite strands. Genes & Dev. 2008 doi: 10.1101/gad.1613108. (this issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautz D., Hancock J.M., Webb D.A., Tautz C., Dover G.A. Complete Sequences of the rRNA genes of Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1988;5:366–376. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler D.M., Okamura K., Chung W.-J., Hagen J.W., Berezikov E., Hannon G.J., Lai E.C. Functionally distinct regulatory RNAs generated by bidirectional transcription and processing of microRNA loci. Genes & Dev. 2008 doi: 10.1101/gad.1615208. (this issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R.A.H., Wilcox M. Regulation of the distribution of Ultrabithorax proteins in Drosophila. Nature. 1985;318:563–567. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03889.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Ashe H., Burks C., Levine M. Characterization of the transvection mediating region of the Abdominal-B locus in Drosophila. Development. 1999;126:3057–3065. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]