Abstract

Objective To compare the energy expenditure of adolescents when playing sedentary and new generation active computer games.

Design Cross sectional comparison of four computer games.

Setting Research laboratories.

Participants Six boys and five girls aged 13-15 years.

Procedure Participants were fitted with a monitoring device validated to predict energy expenditure. They played four computer games for 15 minutes each. One of the games was sedentary (XBOX 360) and the other three were active (Wii Sports).

Main outcome measure Predicted energy expenditure, compared using repeated measures analysis of variance.

Results Mean (standard deviation) predicted energy expenditure when playing Wii Sports bowling (190.6 (22.2) kJ/kg/min), tennis (202.5 (31.5) kJ/kg/min), and boxing (198.1 (33.9) kJ/kg/min) was significantly greater than when playing sedentary games (125.5 (13.7) kJ/kg/min) (P<0.001). Predicted energy expenditure was at least 65.1 (95% confidence interval 47.3 to 82.9) kJ/kg/min greater when playing active rather than sedentary games.

Conclusions Playing new generation active computer games uses significantly more energy than playing sedentary computer games but not as much energy as playing the sport itself. The energy used when playing active Wii Sports games was not of high enough intensity to contribute towards the recommended daily amount of exercise in children.

Introduction

Young people are currently recommended to take an hour of moderate to vigorous physical exercise each day, which should use at least three times as much energy as is used at rest.1 2 Many adolescents have mostly sedentary lifestyles,3 however, as a result of a variety of factors. Time spent in front of television and computer screens has been causally linked to physical inactivity and obesity, although the associations are often weak.4

The new generation of wireless based computer games is meant to stimulate greater interaction and movement during play. A recent study reported that playing computer games using a hand held controller while seated increased energy expenditure above resting values by 22%, whereas activity based games that require upper body movements and dance games increased energy expenditure by 108% and 172%, respectively.5 The new generation of computer games could therefore be a useful addition to the range of opportunities for physical activity available to adolescents. Children spend a large amount of time playing computer games,6 and it is difficult to persuade them to relinquish these screen based activities.7 Activity promoting computer games might therefore be a useful way to increase activity in young people. In this study, we measured the energy expenditure of adolescent girls and boys playing Nintendo Wii (active) and Microsoft XBOX 360 (inactive) computer games.

Method

Participants and settings

A convenience sample of five girls and six boys aged 13-15 participated in the study. All participants regularly played sedentary computer games for at least two sessions of two hours each week and had not previously used Wii. All girls and boys were competent at sport; they regularly represented their school at hockey or netball (girls) and rugby or soccer (boys). Parents and adolescents consented to the study.

Anthropometry

We measured height to the nearest 0.1 cm using a portable stadiometer and weight to the nearest 0.1 kg using a calibrated mechanical flat scale. Measures were taken using standard anthropometric techniques.8

Familiarisation

On separate days from experimental trials, participants practised playing on the XBOX 360 and Wii computer consoles. For sedentary gaming, participants completed two races on a single player race mode on the game Project Gotham Racing 3 (XBOX 360) using a wireless hand held controller. For activity promoting gaming, participants completed the training modes for bowling, tennis, and boxing on the Wii Sports computer game. During familiarisation participants wore an IDEEA (intelligent device for energy expenditure and activity) system.

Energy expenditure

After at least two hours of fasting and five minutes of supine rest, we measured resting energy expenditure for six minutes using indirect calorimetry and a face mask. Energy expenditure during gaming was predicted using the previously validated IDEEA system, which can identify the type of activity and measure the intensity of physical activity in free living conditions.9 The IDEEA system comprises a small recorder worn at the waist and five sensors attached to three thin and flexible wires that connect to the recorder. Sensors are attached to the centre of the subject’s chest (about 4 cm below the clavicle), the front of each thigh, and the underside of each foot on the outside arch, using porous hypoallergic medical tape. Sensors measure the acceleration and angle of each body segment.10 Before data collection began, we initialised the IDEEA using each participant’s weight, height, age, and sex and calibrated the sensors. After each trial, we analysed the downloaded and processed data using ActView, a Windows based programme that provides detailed information on the energy expenditure of each activity.

Experimental trial

Each participant performed one experimental trial. The participants first played on Project Gotham Racing 3 (inactive)—they raced against central processing unit opponents for 15 minutes. After a five minute rest they then played on Wii Sports (active). Participants played competitive bowling, tennis, and boxing matches for 15 minutes each, as recommended by Nintendo, with a five minute rest between sports. Once a race, match, or game was completed participants restarted the event and continued to play for 15 minutes. Each child played for a total of 60 minutes.

Data analysis

We hypothesised that participants’ energy expenditure would be greater when playing activity promoting computer games (Wii) than when playing sedentary computer games (XBOX 360). Data were analysed using a one way repeated measures analysis of variance with corrected post hoc paired t tests.11 We used SPSS for statistical analyses and set statistical significance at P≤0.05.

Results

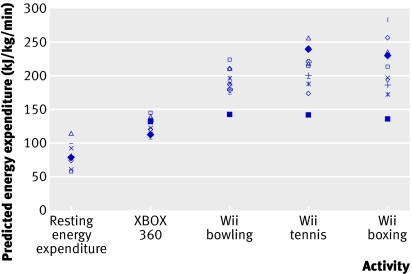

Table 1 and the figure give the participants’ characteristics and body mass adjusted values for resting energy expenditure and predicted energy expenditure during gaming.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics and energy expenditure

| All (n=11) | Boys (n=6) | Girls (n=5) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | |||

| Age (years) | 14.6 (0.5) | 14.9 (0.3) | 14.3 (0.5) |

| Weight (kg) | 60.4 (8.8) | 65.4 (8.5) | 54.4 (4.7) |

| Height (m) | 1.69 (0.1) | 1.78 (0.05) | 1.59 (0.04) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.2 (2.5) | 20.7 (2.6) | 21.7 (2.6) |

| Energy expenditure (kJ/kg/min) | |||

| Resting energy expenditure | 81.3 (17.2) | 83.0 (21.5) | 79.3 (12.4) |

| Predicted energy expenditure | |||

| XBOX 360 | 125.5 (13.7) | 127.9 (13.2) | 122.6 (15.3) |

| Wii Sports bowling | 190.6 (22.2) | 201.8 (16.3) | 177.2 (22.2) |

| Wii Sports tennis | 202.5 (31.5) | 222.2 (23.4) | 178.9 (22.8)* |

| Wii Sports boxing | 198.1 (33.9) | 206.8 (23.8) | 187.7 (43.9) |

*Significantly lower than in boys (P=0.013).

Participants’ mean resting energy expenditure and predicted energy expenditure when playing computer games

All games significantly increased predicted energy expenditure above resting energy expenditure (P<0.001). The boys’ predicted energy expenditure was significantly greater than that of the girls during Wii Sports tennis (P=0.013). Predicted energy expenditure was significantly greater for all activity promoting Wii Sports games than for inactive games on the XBOX 360 (P<0.001). Table 2 compares energy expenditure found in this study with energy expenditure during various sports and activities. More energy is used when actually bowling, boxing, or playing tennis than when playing the Wii versions of these sports.

Table 2.

Mean energy expenditure for all participants during gaming and various sports and activities

| Activity | Mean energy expenditure (kJ) | |

|---|---|---|

| Each minute | Each hour | |

| This study | ||

| Resting energy expenditure | 5 | 300 |

| XBOX 360 | 7.5 | 450 |

| Wii Sports bowling | 11.7 | 700 |

| Wii Sports tennis | 12.5 | 750 |

| Wii Sports boxing | 12.1 | 730 |

| Various activities | ||

| Sitting playing board games | 6.7 | 400 |

| Bowling | 13.3 | 800 |

| Tennis (doubles) | 22.2 | 1330 |

| Boxing (punch bag) | 26.8 | 1600 |

| Boxing (sparring) | 40.1 | 2410 |

We calculated values for the various activities using metabolic equivalents.12

Discussion

Predicted energy expenditure was at least 51% greater during active gaming than during sedentary gaming. This equates to an increase in energy expenditure of 250 kJ (60 kcal) an hour during active gaming compared with sedentary gaming. In a typical week of computer play for these participants, active gaming rather than passive gaming would increase total energy expenditure by less than 2%13 14; although this figure is trivial it might contribute to weight management. Active gaming used less energy than authentic bowling, tennis, and boxing, and the exercise was not intense enough to contribute towards the recommended amount of daily physical activity for children.2 Nevertheless, new generation computer games stimulated positive activity behaviours—the children were on their feet and they moved in all directions while performing basic motor control and fundamental movement skills that were not evident during seated gaming. Given the current prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity, such positive behaviours should be encouraged.

Sex comparisons interestingly showed that, although all participants were competent sportspeople, the boys’ predicted energy expenditure during active gaming was greater than that of the girls, significantly so for tennis. Such differences may therefore indicate enhanced interactive effects of active gaming in boys and additional advantages in terms of energy expenditure.

Limitations

The study has several limitations. Firstly, the IDEEA accurately estimates free living and physical activity energy expenditure, but the monitor does not detect arm movements well.9 Energy expenditure may therefore have been underestimated during active gaming, which involves arm movements. The use of this system was supported by a recent method comparison study, however, which used the IDEEA as its criterion measure.15 Secondly, the study was laboratory based and may not have replicated conditions in the home. However, the children followed the instructions provided for home use, and energy responses are unlikely to be significantly different in a home based study. Thirdly, although we detected statistically significant differences in energy expenditure, our study was small and results are applicable only to lean, sports competent 12-15 year old adolescents and to the Wii Sports computer game, which is more active than other Wii games. Finally, we did not randomise the order of gaming during trials. This was because the children’s availability was limited and because we wanted to make the experimental design as efficient as possible.

What is already known on this topic

Computer games have been implicated in obesity and inactivity in young people

Little information is available on the activity levels of young people when playing new generation computer games

What this study adds

New generation computer games significantly increased energy expenditure compared with sedentary games

These increases were of insufficient intensity to contribute towards recommendations for children’s daily exercise

Conclusion

Activity promoting new generation active computer games significantly increased participants’ energy expenditure compared with sedentary games, but not to the same extent as the authentic sports. Further research is needed to investigate the energy demands of active gaming across sexes, ages, and consoles.

Thanks to Greg Atkinson (Liverpool John Moores University) for statistical support and to students from Ormskirk school for their participation.

Contributors: GS and NTC conceived the study. NTC secured funding. NDR, GS, and LG helped plan and design the study. LG, NDR, and GS collected the data. GS and LG manipulated and analysed the data. GS and LG wrote the manuscript and all authors supplied comments. LG is guarantor.

Funding: This work was funded by Cake, marketing arm of Nintendo UK.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Liverpool John Moores University ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Strong WB, Malina RM, Blimkie CJ, Daniels SR, Dishman RK, Gutin B, et al. Evidence based physical activity for school-age youth. J Pediatr 2005;146:732-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trost SG, Pate RR, Sallis JF, Freedson PS, Taylor WC, Dowda M, et al. Age and gender differences in objectively measured physical activity in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002;34:350-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sproston K, Primatesta P. Health survey for England 2002: the health of children and young people London: Stationery Office, 2003

- 4.Vandewater EA, Shim M, Caplovitz AG. Linking obesity and activity level with children’s television and video game use. J Adolesc 2004;27:71-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lanningham-Foster L, Jensen TB, Foster RC, Redmond AB, Walker BA, Heinz D, et al. Energy expenditure of sedentary screen time compared with active screen time for children. Pediatrics 2006;118:1831-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olds T, Ridley K, Dollman J. Screenieboppers and extreme screenies: the place of screen time in the time budgets of 10-13 year-old Australian children. Aust N Z J Public Health 2006;30:137-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faith MS, Berman N, Heo M, Pietrobelli A, Gallagher D, Epstein LH, et al. Effects of contingent television on physical activity and television viewing in obese children. Pediatrics 2001;107:1043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric standardisation reference manual Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2001

- 9.Zhang K, Pi-Sunyer FX, Boozer CN. Improving energy expenditure estimation for physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004;36:883-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang K, Werner P, Sun M, Pi-Sunyer FX, Boozer CN. Measurement of human daily physical activity. Obes Res 2003;11:33-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Field A. Discovering statistics using SPSS for Windows London: SAGE Publications, 2000

- 12.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32:498-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandini LG, Schoeller DA, Dietz WH. Energy expenditure in obese and nonobese adolescents. Pediatr Res 1990;27:198-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazzer S, Boirie Y, Bitar A, Montaurier C, Vernet J, Meyer M, et al. Assessment of energy expenditure associated with physical activities in free-living obese and nonobese adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;78:471-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welk GJ, McClain JJ, Eisenmann JC, Wickel EE. Field validation of the MTI Actigraph and BodyMedia armband monitor using the IDEEA monitor. Obesity 2007;15:918-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]