Abstract

Research Objective

(1) To assess the effects of New York's Health Care Reform Act of 2000 on the insurance coverage of eligible adults and (2) to explore the feasibility of using the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) as opposed to the Current Population Survey (CPS) to conduct evaluations of state health reform initiatives.

Study Design

We take advantage of the natural experiment that occurred in New York to compare health insurance coverage for adults before and after the state implemented its coverage initiative using a difference-in-differences framework. We estimate the effects of New York's initiative on insurance coverage using the NHIS, comparing the results to estimates based on the CPS, the most widely used data source for studies of state coverage policy changes. Although the sample sizes are smaller in the NHIS, the NHIS addresses a key limitation of the CPS for such evaluations by providing a better measure of health insurance status. Given the complexity of the timing of the expansion efforts in New York (which encompassed the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks), we allow for difference in the effects of the state's policy changes over time. In particular, we allow for differences between the period of Disaster Relief Medicaid (DRM), which was a temporary program implemented immediately after September 11th, and the original components of the state's reform efforts—Family Health Plus (FHP), an expansion of direct Medicaid coverage, and Healthy New York (HNY), an effort to make private coverage more affordable.

Data Sources

2000–2004 CPS; 1999–2004 NHIS.

Principal Findings

We find evidence of a significant reduction in uninsurance for parents in New York, particularly in the period following DRM. For childless adults, for whom the coverage expansion was more circumscribed, the program effects are less promising, as we find no evidence of a significant decline in uninsurance.

Conclusions

The success of New York at reducing uninsurance for parents through expansions of both public and private coverage offers hope for new strategies to expand coverage. The NHIS is a strong data source for evaluations of many state health reform initiatives, providing a better measure of insurance status and supporting a more comprehensive study of state innovations than is possible with the CPS.

Keywords: Health insurance, Medicaid, state health reform

Lack of health insurance is a persistent problem in the U.S. health care system, with little consensus as to how to increase coverage (IOM 2004). As a result, states continue to explore alternative strategies that rely on both expansions of public programs and incentives to increase coverage in the private sector. It is important that we learn from these state efforts in developing new federal and state initiatives (Corrigan, Greiner, and Erickson 2002). Unfortunately, evaluating the effects of state health care reform is complicated by a lack of data (Davern et al. 2004). Recent evaluations have largely relied on special (and expensive) surveys (e.g., Moreno and Hoag 2001; Mitchell et al. 2002; Long, Coughlin, and King 2005; Long, Zuckerman, and Graves 2006), or the Current Population Survey (CPS) (e.g., Kronick and Gilmer 2002; LoSasso and Buchmueller 2004; Busch and Duchovny 2005). However, the CPS has limitations for such evaluations, including poor measurement of health insurance status.

This study explores the feasibility of using the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) to evaluate the effects of state health reform efforts. The NHIS, which is conducted each year for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, provides information on health indicators, health care utilization and access, and health-related behaviors for the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Although the sample sizes in the NHIS are smaller than CPS, the NHIS provides data on current health insurance coverage and offers data on additional outcomes, including access to and use of health care. If the NHIS proves to be a reasonable data source for evaluations of state reform efforts, it provides the possibility of a more comprehensive study than is possible with the CPS, without the need to invest in the significant expense of a state-specific survey.

In this paper we use the NHIS and CPS to assess the effects of health reform efforts in New York State, which passed legislation in 2000 that expanded eligibility for public coverage and provided supports to make private health insurance more affordable. Specifically, we estimate the effects of New York's initiative on insurance coverage using the NHIS and compare the results with estimates based on the CPS.

HEALTH CARE REFORM IN NEW YORK

In November 2000, New York passed the Health Care Reform Act of 2000 (HCRA), which, among other things, created two new programs. The first program, Family Health Plus (FHP), expanded public coverage to parents with incomes up to 150 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) and to childless adults with incomes up to 100 percent of the FPL. Previously, the state covered parents with incomes up to 100 percent of the FPL and childless adults with incomes up to 50 percent of the FPL. However, some counties provided expanded coverage for childless adults beyond that level, including expansions of up to about 75 percent of FPL in a few counties. FHP provides a benefit package similar to what is provided by the State's Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) under a managed care delivery system.

The second program, Healthy New York (HNY), makes private coverage more affordable for uninsured low-income individuals by reducing premiums for private coverage through a reinsurance mechanism that covers most of the expenses of high-cost enrollees. HNY also allows coverage of fewer benefits than are normally mandated, higher cost-sharing and mandated enrollment in an HMO network. HNY is available to qualifying small employers and their employees and to sole proprietors and working individuals with incomes less than 250 percent of the FPL who are not offered coverage by their employer. It is estimated that families might have to spend 5 percent of their incomes if they enroll in HNY (Swartz 2001). Although available to small businesses, only about 25 percent of HNY enrollment has been in group health plans.

HNY began enrollment in January 2001 and FHP was to begin enrollment on October 1, 2001. While FHP was implemented on time in upstate New York, the September 11th terrorist attacks delayed its implementation in New York City. In the aftermath of September 11th, New York established a temporary Medicaid program, Disaster Relief Medicaid (DRM), in New York City. The eligibility criteria in place under DRM were largely identical to those of FHP, but with fewer crowd-out restrictions, an expedited application process, and presumptive eligibility. Enrollment in DRM took place between September 2001 and February 2002. FHP was implemented in New York City in February 2002. The transition from DRM to FHP occurred over the next 9 months, with the state allowing coverage under DRM until November 2002.

The impact of these policy changes will play out through two distinct channels. The expansion of eligibility for public coverage under FHP could increase enrollment in public coverage by giving more people the option of enrolling, while the reduction in premiums under HNY could increase enrollment private coverage. However, the effects of HNY are not likely to be large, given that premium reductions relative to coverage through the small group market are estimated to be between 15 and 30 percent (Swartz 2001) and that the elasticity of the demand for coverage is not large (Marquis and Long 1995). A key research question is whether the increases in coverage under the combinations of FHP and HNY result in a net increase in insurance coverage, or do the enrollees in these two programs simply shift from other sources of coverage.

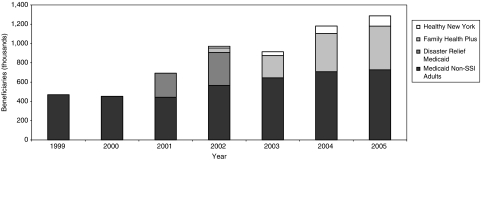

Administrative data show a clear increase in enrollment following the implementation of HNY, FHP, and DRM (Figure 1). However, the enrollment data cannot tell us whether the increased enrollment is due to New York's expansion in eligibility rather than other changes happening over the same time period (e.g., an economic downturn). Nor can the enrollment data tell us whether uninsurance declined as a result of the expansion in public coverage or whether the public expansion was crowding out existing private coverage. A recent descriptive study found that, relative to national trends, uninsurance did not fall among low-income adults—the primary group that FHP and HNY are trying to assist (EP&P Consulting 2005). However, more rigorous methods are needed to assess New York's expansion efforts with greater confidence.

Figure 1:

Nonaged/Nondisabled Adults with Public Coverage in New York, 1999–2005

Sources: Report on the Healthy NY Program 2005. A Report for the State of New York Insurance Department, EP&P Consulting, December 2005; Medicaid Quarterly Reports by Category of Eligibility and Social Service District, Calendar Year Enrollment Numbers; Rorer, Eleanor. “Disaster Relief Medicaid Enrollment to End January 31st,” United Hospital Fund press release, January 19, 2002; LeCouteur, Eugene. “New York's Disaster Relief Medicaid: What Happened When It Ended?” A Report for the Commonwealth Fund, Lake Snell Perry & Associates, July 2004.

Other Recent Changes in New York

In 2001, the New York State Court of Appeals ruled unconstitutional the 1996 welfare reform provision restricting Medicaid coverage for recent immigrants and unqualified aliens (Aliessa et al. v. Novello 2001). As a result, the state was required to restore Medicaid benefits and pay past medical bills for immigrants who would have been eligible under the prewelfare reform Medicaid rules. Later, in 2002, the state expanded Medicaid eligibility for pregnant women and infants from 185 percent of FPL to 200 percent of FPL, and in July 2003, New York established a Medicaid buy-in program for working adults with disabilities. There have also been several recent changes to FHP including an asset test for eligibility determination (in the second half of 2004), restrictions on eligibility for local, state and school district employees (2005), and a new copayment system for current enrollees (2005) (New York Department of Health 2005).

STUDY DESIGN, DATA, AND METHODS

Study Design

In order to isolate the effects of New York's FHP and HNY coverage initiatives from other factors, we take advantage of the “natural experiment” that occurred in New York to compare the health insurance coverage for adults before and after the state implemented these policy changes. To control for underlying trends in insurance coverage not related to the coverage initiatives, we subtract changes in health insurance coverage over the same time period for a comparison group of higher-income adults with incomes between 300 and 550 percent FPL who were not affected by the state's policy changes.1 We use the comparison group in a “difference-in-differences” (DD) or comparative change framework (Wooldridge 2002).

The DD model can be written as

where Y is insurance coverage for individual i in period t. The variable Eligible identifies individuals who are eligible for coverage under New York's postexpansion rules. Post is a dummy variable taking the value of 1 if the observation is in the postexpansion period. The interaction variable Eligible × Post identifies individuals who are eligible for coverage in the postexpansion period. Finally, the variable X captures individual and family characteristics. The β's are parameters to be estimated, with the coefficient on the interaction term, β3, providing the estimate of the impact of New York's coverage initiative.

Because of the complexity of the implementation period for New York's coverage initiative, we also estimate a model that includes two postimplementation periods: The initial period that included DRM, and the subsequent period that was limited to HNY and FHP. This issue is discussed further below. Finally, given the differences in the expansions of coverage for parents and childless adults, we estimate separate models for the two populations.

We focus on the effect of the coverage expansion on the total eligible population, rather than the newly eligible population, for three reasons. First, the publicity associated with the coverage expansion to higher income populations is likely to have a spillover effect on enrollment by those who were previously eligible, both by increasing awareness of the public programs and by reducing the stigma associated with them. Second, there is substantial measurement error in the income measures in the NHIS and CPS, making it difficult to define narrow income eligibility categories with precision. Finally, sample sizes, particularly in the NHIS, were such that detailed subgroup analyses were not feasible.

Data

This study relies on the NHIS and the CPS. The NHIS and CPS both provide representative samples of the civilian, noninstituionalized population in the United States. The primary focus of the NHIS is to provide information on the health and health-related characteristics of the U.S. population. Of relevance to this study, the NHIS, which is fielded continuously over the year, collects information on current health insurance status. The primary focus of the CPS is to provide government statistics on labor force participation, employment and income. However, information on health insurance coverage over the prior calendar year is collected as part of an annual March Supplement to the survey. The CPS is the most common data source for estimates of the uninsurance rate for the nation as a whole and by state (Blewett et al. 2004).

Both the NHIS and CPS are based on stratified, multistage sample designs, with samples drawn from every state. While neither survey is designed to produce direct state-specific estimates, the sample design of the surveys allow researchers to draw representative samples for large states, such as New York (DHHS 2004). State identifiers are included on the public use files of the CPS. Because state identifiers in the NHIS are viewed as confidential, access to those variables is through the National Center for Health Statistics Research Data Center (RDC), requiring us to conduct our NHIS analyses at the RDC.

As noted above, a key limitation of the CPS for studies of state health reform efforts is its health insurance measure. Health insurance is collected once each year (in March) in the CPS, at which time the household respondent is asked to report on coverage over the calendar year before the survey for all members of the household. Some respondents report on calendar year coverage, while others report on current health insurance status or on the status at the end of the previous calendar year (SHADAC 2001a, SHADAC 2001b). As the March health insurance measure in the CPS may cover 15 months before the survey and require significant recall, the pre- and postexpansion periods defined by the CPS may not be closely tied to the timing of a policy change.

By contrast, the NHIS is fielded on a continuous basis and asks each adult in the household about his/her insurance coverage at the time of the survey. This avoids the recall bias problems inherent in the CPS framework and allows us to define pre- and postexpansion periods based on the individual's date of interview. Thus, estimates of policy impacts in the NHIS are closely aligned to the timing of the policy change.

As noted above, we estimate program effects for the overall postimplementation period and for two separate postimplementation periods. The first postperiod is the period following September 11, 2001, when DRM was in place in New York City. Over this period, the HNY program was in place in both New York City and upstate New York and FHP was in place only in upstate areas. We refer to this as the DRM period, which corresponds to September 2001 to November 2002. The second postperiod is the period following DRM, when HNY and FHP were in operation statewide. We refer to this as the FHP/HNY period, which runs from November 2002 to March 2004 in our study. The latter period provides the estimate of the effects of New York's HCRA expansion effort, net of the effects of DRM. As is discussed further below, we do not attempt to isolate the effects of the different components of New York's expansion nor to separate the effects of the expansion efforts on the newly eligible populations from that of the overall eligible population.

Using the NHIS, we assign observations to the preperiod and the two postperiods based on their quarter of interview. We define the DRM period as the fourth quarter of 2001 through the end of the third quarter of 2002, and the FHP/HNY period as the fourth quarter of 2002 through 2004. For the CPS, we assign individuals to the preperiod and the two postperiods based on the calendar year for which they were to report insurance coverage. So, for example, observations from the March 2001 CPS are assigned to the preperiod, those from the March 2002 and 2003 CPS are assigned to the DRM period, and those from March 2004 and 2005 are assigned to the FHP/HNY period. The inability to align the CPS with the pre- and posttime periods suggests that CPS estimates for the DRM and FHP/HNY periods are measured with some error.

However, the NHIS is not without its own problems. Most important for this study, is the income measure. Unlike the CPS, which constructs income by summing categories of earned and unearned income obtained from a series of questions for each individual, the NHIS asks about individual earnings and total family income. It is likely that the omnibus income measure of the NHIS understates income relative to an income measure aggregated from multiple questions (Davern, Robin et al. 2005). Furthermore, having only the omnibus income measure prevents us from constructing a measure of income for the health insurance unit (HIU), that is, the members of a nuclear family who can be covered by one health insurance policy.

We address this issue by trying to align the NHIS income measure with the CPS measure as best we can. We do this by subtracting from total family income the earned income of all household members not in the HIU. Nevertheless, as we cannot subtract other sources of income for members not in the HIU (such as unearned income and cash assistance payments), it is likely that we overstate income, and understate program eligibility, in the NHIS relative to the CPS. To explore the biases in our findings that may result from these limitations of the NHIS income measure, we conducted a sensitivity analysis of the CPS in which we imposed the constraints of the NHIS income questions on the otherwise richer set of income data available from CPS. These results are presented below.

Another consideration is the definition of parents and childless adults in the two surveys. New York provides coverage to the parents and caretakers of children, including the parents of some 19- and 20-year-old children who are living at home. In both surveys we use information on the relationships between the individuals in the household to link parents and caregivers to the children for whom they are responsible. However, because the NHIS provides more detailed information on family relationships, that survey allows us to link nonparent caregivers of children (e.g., grandparents) with the children they care for. As a result, the sample of “parents” in the NHIS includes both parents and caregivers, while the sample of “parents” in the CPS is limited to parents only. As a test of the sensitivity of our findings to differences in the composition of the childless adult sample, we conducted supplemental analyses (not shown) that restricted the childless adult samples for both the CPS and NHIS to adults in households in which there were no children. We found no notable differences in our estimates.

Analysis Sample

In both the NHIS and CPS our analysis sample is adults aged 19–64 in New York. The treatment group is adults who would be eligible for coverage under the state's 2004 eligibility rules for FHP or HNY. Thus, we define as “eligible” any adult with family income below 250 percent of the FPL. We account for retrospective enrollment and eligibility changes after the Aliessa et al. v. Novello court decision by restricting our analysis sample to U.S. citizens only. As our CPS sample captures insurance coverage through, at most, March 2004 (the CPS survey month), we restrict our NHIS sample to those interviewed before April 2004. We do this to align the postperiod in the NHIS analysis more closely to the likely CPS postperiod. However, sensitivity analyses using the entire 2004 NHIS sample yielded nearly identical results as those reported here. Our treatment sample includes 10,189 adults in the NHIS and 19,636 adults in the CPS for the study period of 1999–2004.

One area of concern related to the CPS is how it imputes missing data for the March supplement. Specifically, state is not one of the variables used to conduct the hot-deck imputation and, as a result, insurance coverage could be understated in states with high rates of coverage and overstated in states with low rates of coverage (Davern et al. 2004). The possibility of imputation biases would not be serious if we were not focusing on a state-level policy change or if the number of imputed cases were trivial. However, in the CPS, imputations for nonresponse of the March Supplement account for nearly 12 percent of the New York sample. To assess how these imputations may affect our results, we conducted an additional sensitivity analysis in which we dropped all imputed cases from the CPS analytic sample, reweighted the remaining CPS data so that they were state representative, and reestimated our models. We present the results from that sensitivity test below.

Defining Insurance Status

Defining insurance status is complicated for this analysis because of the uncertainty about where respondents will report HNY. Some are likely to report it as public coverage, especially those who enroll as individuals, while others may report it as nongroup coverage or, for those covered through their employer, ESI coverage. Adding to the complexity, the NHIS, but not the CPS, includes HNY in its specific examples of public programs in New York. Because of this, it is likely that the NHIS captures more of HNY coverage as public coverage than does the CPS.

As we cannot separate those reporting coverage under HNY from other public coverage in the NHIS and as most enrollment in HNY is in nongroup coverage, we combine nongroup coverage with public coverage in both the NHIS and CPS. That is, we use the following hierarchical insurance groups in each year: (1) reported public coverage and nongroup coverage, (2) reported private coverage (includes employer coverage from a current or former employer or union or under a military program), and (3) uninsured. To test the sensitivity of our public coverage findings to the inclusion of nongroup coverage with public coverage, we also estimated the model using public coverage as reported in the survey as the dependent variable. The estimates were very similar using the two different measures, particularly for the NHIS. We include both public insurance groups (public/nongroup and public only) in our tables, focusing on the estimates for the combined public and nongroup coverage as our preferred measure of public coverage.

Methods

We isolate the effects of the state coverage expansions on insurance coverage through DD and multivariate regression methods. The regression models include a rich set of variables to control for differences in the treatment and comparison groups (beyond treatment status) and differences within each group over time that could affect our outcomes of interest—health insurance coverage. We estimate linear probability models for ease of computation and to facilitate comparisons across alternative models. As we are comparing the CPS and NHIS, we are constrained by the variables available in both surveys. Table 1 summarizes the control variables for analysis, providing the means for the two samples.

Table 1:

Summary of Explanatory Variables

| Parents | Childless Adults | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | NHIS | CPS | NHIS | CPS |

| Age (years) | 38.6 | 38.7 | 39.5 | 39.4 |

| Female (%) | 58.9 | 60.1 | 49.6 | 49.3 |

| Black (%) | 18.7 | 15.2 | 17.2 | 18.5 |

| Other nonwhite race (%) | 4.0 | 5.2 | 4.3 | 4.7 |

| Hispanic (%) | 14.3 | 15.2 | 12.6 | 12.6 |

| High school graduate (%) | 81.7 | 87.2 | 79.2 | 85.1 |

| Never married (%) | 13.4 | 13.3 | 49.6 | 54.2 |

| Widowed/separated/divorced (%) | 12.9 | 13.1 | 17.7 | 18.1 |

| Health is fair/poor (%) | 8.3 | 9.0 | 12.5 | 15.6 |

| Has functional limitation (%) | 7.0 | 6.1 | 15.7 | 13.7 |

| Spouse's health is fair/poor or spouse has functional limitation (%) | 6.4 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 4.6 |

| HIU size | 3.7 | 3.8 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

| Sample size | 4,603 | 8,886 | 5,586 | 10,815 |

Source: 2000–2004 CPS; 1999–2004 NHIS.

NHIS, National Health Interview Survey; CPS, Current Population Survey.

Estimating Standard Errors

As both the CPS and NHIS rely on complex survey design, obtaining design-adjusted estimates of the standard errors is important. Obtaining estimates of the variance assuming that the data come from a simple random sample when a complex, multistage design was used will bias the variance estimates downward and, as a result, overstate the statistical significance of the parameter estimates. The NHIS provides the information needed to obtain standard errors that reflect the survey design. Unfortunately, sample design information is censored from the CPS public-use files. We address this issue in our comparisons of the findings from the CPS and NHIS by providing estimates that build upon on the method developed by Davern, Jones et al. (2005) to approximate the survey-design adjustment for the CPS in the public-use files. In addition, our analyses of NHIS data uses the imputed income files developed by the National Center for Health Statistics, with adjustments of our estimates to account for the multiply-imputed data (Schenker et al. 2006).

Limitations of Our Methods

Although we use a strong quasiexperimental design and control for a wide array of individual and family characteristics in the regression analysis, it is always possible with quasi-experimental methods that unmeasured differences between the treatment and comparison samples may confound the impact estimates. Further, as with all analyses based on survey data, our ability to detect small changes in insurance coverage that result from New York's expansion effort is constrained by the sample sizes in the survey.

RESULTS

Changes in Eligibility

Both the NHIS and CPS show a substantial increase in eligibility for coverage under New York's expansion effort (Table 2). Using NHIS data, we find that the expansion of eligibility to higher income adults led to an increase from 12 to 32 percent for parents in New York eligible for public coverage (under Medicaid and FHP) or subsidized private coverage under HNY, and an increase in eligibility from 11 to 33 percent for childless adults.2 By contrast, we find somewhat higher eligibility levels using the CPS. The share of eligible adults in New York rose from 13 to 35 percent among parents, and from 13 to 37 percent among childless adults. Noted above, this NHIS–CPS difference likely reflects differences in the income measures in the two surveys. The NHIS likely overstates income relative to program eligibility rules.

Table 2:

Changes in Eligibility for Public Coverage for New York Parents and Childless Adults

| Period | Parents | Childless Adults |

|---|---|---|

| NHIS (%) | ||

| Preperiod | 12.2 | 10.5 |

| Postperiod | 32.4 | 32.8 |

| CPS (%) | ||

| Preperiod | 13.2 | 12.6 |

| Postperiod | 35.4 | 37.4 |

Source: 2000–2004 CPS; 1999–2004 NHIS.

NHIS, National Health Interview Survey; CPS, Current Population Survey.

Changes in Insurance Coverage

Table 3 shows the simple differences in insurance coverage between the period before New York's coverage expansions and the period after the expansion for parents and childless adults based on the NHIS (top panel) and CPS (bottom panel). We report the estimates for the full postperiod, and separately for the period in which DRM was in effect (Post 1) and the post-DRM period (Post 2). As noted above, we believe the post-DRM period is the appropriate period to focus on in accessing the effects of New York's HCRA expansion effort. Not surprisingly, given the differences in how the two surveys measure insurance coverage, the levels of insurance coverage in the CPS and NHIS differ. Our results show the CPS with somewhat higher levels of public coverage (including nongroup coverage as public) and, especially for childless adults, lower levels of ESI coverage than the NHIS.

Table 3:

Simple Differences in Insurance Status for Low-Income Parents and Childless Adults, Pre and Post New York's Coverage Expansions, 1999–2004

| Low-Income Parents | Low-Income Childless Adults | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Public | |||||||

| Public+ Nongroup† | Public Only | ESI | Uninsured | Public+ Nongroup† | Public Only | ESI | Uninsured | |

| NHIS | ||||||||

| Preperiod | 28.7% | 26.3% | 48.3% | 23.0% | 23.8% | 18.7% | 46.4% | 29.7% |

| Full postperiod | 35.9% | 33.8% | 46.8% | 17.3% | 27.6% | 22.7% | 43.9% | 28.5% |

| Post 1—DRM/FHP/HNY | 33.2% | 31.2% | 47.1% | 19.7% | 28.2% | 22.5% | 42.6% | 29.2% |

| Post 2—FHP/HNY | 37.9% | 35.7% | 46.6% | 15.5% | 27.3% | 22.9% | 44.6% | 28.1% |

| Change over time | ||||||||

| Full postperiod | 7.2** | 7.5** | −1.5 | −5.7* | 3.8 | 4.1 | −2.5 | −0.3 |

| Post 1—DRM/FHP/HNY | 4.5 | 4.9 | −1.2 | −3.3 | 4.4 | 3.8 | −3.8 | 0.5 |

| Post 2—FHP/HNY | 9.2** | 9.4** | −1.7 | −7.5* | 3.5 | 4.2 | −1.8 | −0.8 |

| CPS | ||||||||

| Preperiod | 31.6% | 26.1% | 45.8% | 22.6% | 30.5% | 23.1% | 33.9% | 35.6% |

| Full postperiod | 35.1% | 30.2% | 43.5% | 21.3% | 31.6% | 24.6% | 34.8% | 35.4% |

| Post 1—DRM/FHP/HNY | 34.9% | 28.9% | 41.9% | 23.1% | 29.2% | 22.9% | 35.8% | 35.1% |

| Post 2—FHP/HNY | 35.3% | 30.9% | 44.3% | 20.4% | 32.9% | 25.5% | 31.6% | 35.6% |

| Change over time | ||||||||

| Full postperiod | 3.5** | 4.1** | −2.2 | −1.3 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 0.9 | −0.2 |

| Post 1—DRM/FHP/HNY | 3.3 | 2.8 | −3.9 | 0.6 | −1.3 | −0.2 | 1.9 | −0.5 |

| Post 2—FHP/HNY | 3.7* | 4.8** | −1.4 | −2.2 | 2.3 | 2.4 | −2.3 | 0.0 |

Source: 2000–2004 CPS; 1999–2004 NHIS.

Significantly different from zero at the .10 and .05 level, respectively, two-tailed test.

Significantly different from zero at the .10 and .05 level, respectively, two-tailed test.

This category includes public and private nongroup insurance (see text).

Based on simple differences, both the CPS and NHIS show significant increases in public coverage for parents following New York's expansion effort, although there are differences in the magnitudes of those estimates. The NHIS shows an increase in public coverage of about 9 percentage points for parents in the post-DRM period, compared with a 4 percentage point increase in the CPS. Part of that difference likely reflects the explicit inclusion of HNY in the NHIS question on public coverage. The change in ESI coverage for parents is generally small, especially in the post-DRM period, and is not statistically significant in either survey. The result of those changes is a reduction in uninsurance for parents in both surveys in the post-DRM period, although the reduction in the CPS is not statistically significant.

For childless adults, we see no significant changes in insurance status over time in either the NHIS or CPS. Although not statistically significant, public coverage is somewhat higher and ESI coverage somewhat lower in the post-DRM period, with the effects largely offsetting. As a result, there are no changes in the rate of uninsurance for childless adults in either survey.

As noted above, our comparison group for the DD analysis is higher-income parents (for the eligible parents) and higher-income childless adults (for the eligible childless adults). As shown in Table 4, there were few significant changes in insurance coverage for the comparison groups. Uninsurance was relatively stable for both higher-income parents and higher-income childless adults. ESI coverage dropped slightly for higher-income childless adults in the CPS, while it rose slightly in the NHIS. Public coverage, which as discussed above, includes nongroup coverage in order to capture HNY enrollment, dropped slightly for higher-income parents, although the change was only significantly different from zero in the CPS. There were no significant changes in public coverage for higher-income childless adults. The changes in insurance status for these comparison groups provide our estimate of the counterfactual for the New York expansions; that is, in the absence of the state's expansion efforts, we assume there would have been similar changes among the low-income parents and childless adults.

Table 4:

Simple Differences in Insurance Status for the Higher-Income Parents and Childless Adults in the Comparison Groups, Pre and Post New York's Coverage Expansions, 1999–2004

| Higher-Income Parents | Higher-Income Childless Adults | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Public | |||||||

| Public+ Nongroup† | Public Only | ESI | Uninsured | Public+ Nongroup† | Public Only | ESI | Uninsured | |

| NHIS | ||||||||

| Preperiod | 2.7% | 1.2% | 92.1% | 5.3% | 5.3% | 1.2% | 80.5% | 14.2% |

| Full postperiod | 2.6% | 1.5% | 91.5% | 5.9% | 4.7% | 1.5% | 83.0% | 12.3% |

| Post 1—DRM/FHP/HNY | 2.0% | 0.7% | 91.8% | 6.3% | 4.3% | 1.3% | 80.6% | 15.1% |

| Post 2—FHP/HNY | 3.0% | 2.1% | 91.4% | 5.6% | 4.9% | 1.5% | 84.6% | 10.5% |

| Change over time | ||||||||

| Full postperiod | −0.1 | 0.3 | −0.6 | 0.6 | −0.6 | 0.3 | 2.5 | −1.9 |

| Post 1—DRM/FHP/HNY | −0.7 | −0.6 | −0.3 | 1.0 | −1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Post 2—FHP/HNY | 0.3 | 0.9 | −0.7 | 0.3 | −0.4 | 0.3 | 4.1* | −3.7* |

| CPS | ||||||||

| Preperiod | 4.5% | 1.2% | 91.6% | 3.9% | 5.9% | 1.8% | 82.4% | 11.7% |

| Full postperiod | 4.0% | 1.6% | 91.4% | 4.7% | 6.7% | 2.7% | 79.8% | 13.6% |

| Post 1—DRM/FHP/HNY | 2.8% | 0.5% | 92.6% | 4.7% | 6.1% | 1.2% | 80.3% | 13.6% |

| Post 2—FHP/HNY | 4.7% | 2.3% | 90.7% | 4.7% | 7.0% | 3.4% | 79.5% | 13.5% |

| Change over time | ||||||||

| Full postperiod | −0.5 | 0.4 | −0.2 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | −2.6* | 1.8 |

| Post 1—DRM/FHP/HNY | −1.7*** | −0.7 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.2 | −0.6 | −2.1 | 1.9 |

| Post 2—FHP/HNY | 0.2 | 1.1 | −0.9 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.7 | −2.9* | 1.8 |

Source: 2000–2004 CPS; 1999–2004 NHIS.

Note: Our comparison group is higher-income adults with incomes between 300 and 550% FPL who are not affected by the state's policy changes.

Significantly different from zero at the .10, and .01 level, respectively, two-tailed test.

Significantly different from zero at the .10, and .01 level, respectively, two-tailed test.

This category includes public and private nongroup insurance (see text).

Effects of the Expansion Effort on Insurance Coverage

Table 5 summarizes the difference-in-differences estimates for the effects of the New York's coverage expansion for parents and childless adults using the NHIS (top panel) and the CPS (bottom three panels). Looking first at the effect of the expansions on public insurance coverage for parents, we find that the results for parents are quite similar in the CPS and NHIS, with both showing significant increases in public coverage. Focusing on the post DRM period, we find that public coverage increased by 8.5 percentage points in the NHIS (p<.10) and between 4.3 and 5.1 percentage points in the CPS (p<.05).

Table 5:

Difference-in-Differences Estimates of the Impact of New York's Coverage Expansions on Insurance Status, 1999–2004 (Standard Errors in Parentheses)

| Parents | Childless Adults | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Public | |||||||

| Public+Nongroup† | Public Only | ESI | Uninsured | Public+Nongroup† | Public Only | ESI | Uninsured | |

| NHIS | ||||||||

| Model 1 | ||||||||

| Full postperiod | 0.067** | 0.066** | −0.010 | −0.057** | 0.039* | 0.033* | −0.043 | 0.004 |

| (0.033) | (0.035) | (0.035) | (0.027) | (0.023) | (0.019) | (0.035) | (0.026) | |

| Model 2 | ||||||||

| Post 1—DRM/FHP/HNY | 0.042 | 0.045 | −0.004 | −0.038 | 0.059** | 0.043* | −0.047 | −0.012 |

| (0.028) | (0.031) | (0.037) | (0.033) | (0.029) | (0.023) | (0.048) | (0.035) | |

| Post 2—FHP/HNY | 0.085* | 0.082* | −0.014 | −0.071** | 0.027 | 0.024 | −0.041 | 0.014 |

| (0.044) | (0.042) | (0.046) | (0.034) | (0.025) | (0.026) | (0.038) | (0.030) | |

| CPS | ||||||||

| Model 1 | ||||||||

| Full postperiod | 0.048*** | 0.047*** | −0.024 | −0.024 | 0.012 | 0.018 | 0.012 | −0.024 |

| (0.018) | (0.015) | (0.021) | (0.017) | (0.015) | (0.012) | (0.019) | (0.018) | |

| Model 2 | ||||||||

| Post 1—DRM/FHP/HNY | 0.053** | 0.039* | −0.052* | −0.001 | −0.002 | 0.019 | 0.037 | −0.035 |

| (0.023) | (0.020) | (0.027) | (0.022) | (0.020) | (0.014) | (0.027) | (0.025) | |

| Post 2—FHP/HNY | 0.045** | 0.050*** | −0.010 | −0.036* | 0.020 | 0.017 | −0.002 | −0.018 |

| (0.020) | (0.017) | (0.024) | (0.019) | (0.017) | (0.014) | (0.021) | (0.020) | |

| CPS—using NHIS income definition | ||||||||

| Model 1 | ||||||||

| Full postperiod | 0.046*** | 0.046*** | −0.027 | −0.020 | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.000 | −0.017 |

| (0.018) | (0.015) | (0.021) | (0.017) | (0.016) | (0.013) | (0.020) | −0.017 | |

| Model 2 | ||||||||

| Post 1—DRM/FHP/HNY | 0.051** | 0.036* | −0.055* | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.018 | 0.027 | −0.028 |

| (0.023) | (0.019) | (0.027) | (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.016) | (0.028) | (0.026) | |

| Post 2—FHP/HNY | 0.043** | 0.051*** | −0.011 | −0.032* | 0.026 | 0.013 | −0.015 | −0.012 |

| (0.020) | (0.017) | (0.024) | (0.019) | (0.018) | (0.015) | (0.022) | (0.021) | |

| CPS—excluding imputations | ||||||||

| Model 1 | ||||||||

| Full postperiod | 0.055*** | 0.047*** | −0.034 | −0.021 | 0.018 | 0.023* | 0.012 | −0.030 |

| (0.019) | (0.019) | (0.022) | (0.017) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.020) | (0.018) | |

| Model 2 | ||||||||

| Post 1—DRM/FHP/HNY | 0.062** | 0.037* | −0.069** | 0.007 | −0.007 | 0.011 | 0.045 | −0.038 |

| (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.027) | (0.009) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.028) | (0.025) | |

| Post 2—FHP/HNY | 0.051** | 0.050*** | −0.015 | −0.036* | 0.031* | 0.029* | −0.005 | −0.026 |

| (0.021) | (0.021) | (0.025) | (0.022) | (0.019) | (0.015) | (0.023) | (0.021) | |

Source: 2000–2004 CPS; 1999–2004 NHIS.

Significantly different from zero at the .10, .05, and .01 level, respectively, two-tailed test.

Significantly different from zero at the .10, .05, and .01 level, respectively, two-tailed test.

Significantly different from zero at the .10, .05, and .01 level, respectively, two-tailed test.

This category includes public and private nongroup insurance (see text).

The effect on ESI coverage is more mixed, with the NHIS showing a relatively small, off-setting reduction in ESI coverage, while the CPS finds a relatively strong offset in ESI coverage in the DRM period, followed by a much smaller effect in the Post 2 post-DRM period. Only the effect for the DRM period in the CPS is significantly different from zero. The NHIS-CPS differences in the DRM period likely reflect the difficulties of aligning the time period for reported insurance coverage in the CPS with the timing of the changes in eligibility in the DRM and post-DRM periods.

Both surveys show significant reductions in uninsurance for parents following the state's expansion efforts. Not surprisingly, the strongest effects are found for the later follow-up period—after the turmoil of September 11th and the DRM period. In the Post 2 period, uninsurance is down about 4 percentage points based on the CPS (p<.10) and 7 percentage points based on the NHIS (p<.05). These patterns hold in our basic CPS estimates (panel 2) as well as in estimates that adjust the CPS income measure to more closely reflect the measure from the NHIS (panel 3) and those that correct for potential imputation biases in the CPS (panel 4).

We also find broad similarity between the NHIS and the CPS in the estimates of the effect of New York's coverage expansion on childless adults, especially in the post-DRM period. We find no evidence of significant gains in public coverage or reductions in uninsurance for childless adults in either survey in the post-DRM period, suggesting there was no increase in insurance coverage for childless adults as a result of the coverage initiative. As with the analysis for parents, this result held in our basic CPS estimates (panel 2), the estimates that adjusted the income measure to more closely reflect the measure from the NHIS (panel 3) and in estimates that attempt to correct for potential imputation biases in the CPS (panel 4).

CONCLUSIONS

Concern about a large and growing uninsured population prompted New York State to pass legislation to increase the number of New Yorkers with health insurance coverage by expanding eligibility for public coverage and making private coverage more affordable. This paper estimated the impact of that policy change, while considering the strengths and weaknesses of the CPS and the NHIS as alternative data sources for an evaluation of state health reforms.

Although the turmoil of September 11th clearly affected the early implementation of the state's reform efforts, our study shows that New York has been quite successful at reducing uninsurance for parents through both expansions of public coverage and subsidies for private coverage. These findings for New York are consistent with earlier findings that show that state coverage expansions have had some success in expanding insurance coverage for low-income adults (Kronick and Gilmer 2002; Long et al. 2006).

For childless adults, the program effects are much less promising. Across the two data sources we used in this study, we found little evidence of a significant increase in public coverage, and, as a result, virtually no change in the overall rates of insurance coverage. We believe this reflects the more limited expansion in public coverage for childless adults than for parents and, as a result, the greater reliance on HNY for this group. Given that HNY was not expected to reduce premiums to a great extent, it is not surprising that this approach did not produce a significant expansion in coverage for childless adults.

On the methodological side, the NHIS offers a strong alternative to the CPS for evaluations of state health reform initiatives. Most importantly, the NHIS is fielded continuously over the year, gathering information on insurance status as of the interview month. As a result, the NHIS allows researchers to define insurance status and the pre- and postperiods for policy changes more accurately than is possible in the CPS. The NHIS also has the advantage of including a more comprehensive set of state program names in its health insurance questions than the CPS, which should allow the NHIS to capture more components of public coverage. Finally, with its access and use data, the NHIS offers the potential for a more comprehensive study of state innovations than is possible with the CPS.

The key limitation of the NHIS relative to the CPS is the size of the state samples. While the state sample sizes in the NHIS are smaller than in the CPS, more than 30 states likely have adequate sample sizes in the NHIS for state-specific analyses. In general, the NHIS offers the greatest potential for evaluating initiatives in larger states and/or initiatives that affect a larger share of a state's population. In support of efforts to use the NHIS for state-level analyses, the National Center for Health Statistics has work underway to develop strategies for using the NHIS for state-level tabulations and analyses, including reports on health insurance status at the state level. These efforts will provide an important foundation for future work using the NHIS for analyses of state-specific policies.

Acknowledgments

This research is part of the Assessing the New Federalism Project and received funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the W. K. Kellogg Foundation, the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and several other foundations. This work was conducted at the Research Data Center of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). We thank Robert Krasowski at NCHS for his help with the study.

Disclosures: There are no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimers: The analyses, interpretations, and conclusions presented in the paper are the responsibility of the authors and not the NCHS, which is responsible only for the initial NHIS data file.

NOTES

1. We explored different income bands for the comparison group of higher income adults and found that that had little effect on our findings. This likely reflects the fact that we found very few significant changes over time in public, ESI, or uninsurance rates for our comparison group samples in New York. In addition to using higher income adults as the comparison group, we also explored the possibility of using comparison groups from other states. However, with so many states making changes in insurance coverage over the same time period, we were not able to identify a reasonable comparison state (or states) for New York.

2. Given that some counties had higher eligibility for childless adults prior to HCRA, these tabulations are an upper-bound estimate of the gain in eligibility for this population. This is also true for the NHIS estimates.

REFERENCES

- Blewett LA, Good MB, Call KT, Davern M. Monitoring the Uninsured. A State Policy Perspective. 2004;29(1):107–45. doi: 10.1215/03616878-29-1-107. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch SH, Duchovny N. Family Coverage Expansions. Impact on Insurance Coverage and Health Care Utilization of Parents. 2005;24:876–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.03.007. Journal of Health Economics. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fostering Rapid Advances in Health Care: Learning from System Demonstration. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davern M, Blewett LA, Bershadsky B, Arnold N. Missing the Mark? Examining Imputation Bias in the Current Population Survey's State Income and Health Insurance Coverage Estimates. Journal of Official Statistics. 2004;20(3):1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Davern M, Jones A, Jr, Lepkrowski J, Davidson G, Blewett LA. “Estimating Standard Errors for Regression Coefficients Using the Current Population Survey's Public Use File.”. Working Paper. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Davern M, Robin H, Beebe TJ, Call KT. The Effect of Income Question Design in Health Surveys on Family Income, Poverty, and Eligibility Estimates. Health Services Research. 2005;40(5, Part I):1534–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00416.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EP&P Consulting. Report on the Healthy NY Program. Prepared for the State of New York Insurance Department. Washington, DC: EP&P Consulting; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) Insuring America's Health: Priorities and Recommendations. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kronick R, Gilmer J. Insuring Low-Income Adults. Does Public Coverage Crowd Out Private? 2002;21(1):225–39. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.1.225. Health Affairs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SK, Coughlin TA, King J. Capitated Medicaid Managed Care in a Rural Area. The Impact of Minnesota's PMAP Program. 2005;21(1):12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00057.x. Journal of Rural Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SK, Zuckerman S, Graves JA. Are Adults Benefiting from State Coverage Expansions? Health Affairs. 2006;25(2):w1–14. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.w1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoSasso AT, Buchmueller TC. The Effect of the State Children's Health Insurance Program on Health Insurance Coverage. Journal of Health Economics. 2004;23(5):1059–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquis MS, Long SH. Worker Demand for Health Insurance in the Non-Group Market. Journal of Health Economics. 1995;14(1):47–64. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(94)00035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JB, Haber SG, Khatutsky G, Donoghue S. Impact of the Oregon Health Plan on Access and Satisfaction of Adults with Low Income. Health Services Research. 2002;37(1):33–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno L, Hoag SD. Covering the Uninsured through TennCare. Does It Make a Difference? 2001;20(1):231–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.1.231. Health Affairs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York Department of Health. “Administrative Directive 05 OMM/ADM-4”. [2005 May 24]. Available at http://www.health.state.ny.us/health_care/medicaid/publications/docs/adm/05adm-4.pdf.

- Schenker N, Raghunathan TE, Chiu PL, Makuc DM, Zhang G, Cohen AJ. “Multiple Imputation of Family Income and Personal Earnings in the National Health Interview Survey: Methods and Examples”. [2006 April 20]. National Center for Health Statistics. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/tecdoc.pdf.

- State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC) “State Health Insurance Coverage Estimates: Why State-Survey Estimates Differ from CPS.”. Issue Brief 3.

- State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC) “The Current Population Survey (CPS) and State Health Insurance Coverage Estimates.”. Issue Brief 1.

- Swartz K. Healthy New York: Making Insurance More Affordable for Low-Income Workers. Washington, DC: The Commonwealth Fund; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge JW. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]