Abstract

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are expressed throughout the central nervous system and influence a variety of higher order functions including learning and memory. While the effects of presynaptic nAChRs on transmitter release have been well documented, little is known about possible postsynaptic actions. A major species of neuronal nAChRs contains the α7 gene product and has a high relative permeability to calcium. Both on rodent hippocampal interneurons and on chick ciliary ganglion neurons these α7-nAChRs are often closely juxtaposed to GABAA receptors. We show here that in both cases activation of α7-nAChRs on the postsynaptic neuron acutely down-regulates GABA-induced currents. Nicotine application to dissociated ciliary ganglion neurons diminished subsequent GABAA receptor responses to GABA. The effect was blocked by α7-nAChR antagonists, by chelation of intracellular Ca2+ with BAPTA, and by inhibition of both Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and mitogen-activated protein kinase. A similar outcome was obtained in the hippocampus where electrical stimulation to activate cholinergic fibres reduced the amplitude of subsequent GABAA receptor-mediated inhibitory postsynaptic currents. The reduction showed the same calcium and kinase dependence seen in ciliary ganglion neurons and was absent in hippocampal slices from α7-nAChR knockout mice. Moreover, α7-nAChR blockade in hippocampal slices reduced rundown of GABAA receptor-mediated whole-cell responses, indicating ongoing endogenous modulation. The results demonstrate regulation of GABAA receptors by α7-nAChRs on the postsynaptic neuron and identify a new mechanism by which nicotinic cholinergic signalling influences nervous system function.

Nicotinic cholinergic signalling is widespread in the vertebrate nervous system and contributes to numerous higher order functions including arousal, attention, nociception, and learning and memory (Picciotto et al. 1995; Bannon et al. 1998; Marubio et al. 1999; Cui et al. 2003; Saint-Mleux et al. 2004; Lambe et al. 2005; Levin et al. 2006). It has also been implicated in a variety of neurodegenerative disorders associated with Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, ageing, and epilepsy, in addition to nicotine addiction (Newhouse et al. 1997; Zoli et al. 1999b; Dani, 2001; Mansvelder & McGehee, 2002; Picciotto & Zoli, 2002; Raggenbass & Bertrand, 2002; Laviolette & van der Kooy, 2004). How nicotinic signalling exerts these diverse effects is far from clear.

Nicotinic cholinergic transmission is mediated by the transmitter acetylcholine (ACh) acting on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), which, in vertebrates, are cation-selective ligand-gated ion channels (McGehee & Role, 1995; Margiotta & Pugh, 2004). One of the most abundant is a species composed of α7 subunits which appears early in development and has a high calcium permeability relative to sodium (Bertrand et al. 1993; Seguela et al. 1993; Zhang et al. 1998; Drisdel & Green, 2000; Adams et al. 2002). Numerous studies have identified a presynaptic role for these receptors (α7-nAChRs), showing that they enhance transmitter release at a variety of synapses (McGehee et al. 1995; Gray et al. 1996; Alkondon et al. 1997; Guo et al. 1998; Li et al. 1998; Radcliffe & Dani, 1998; Maggi et al. 2001, 2004; Mok & Kew, 2006). Much less is known about possible postsynaptic roles for α7-nAChRs though several studies have identified the receptors at postsynaptic sites (Fabian-Fine et al. 2001; Levy & Aoki, 2002) and have reported postsynaptic α7-nAChR responses (Alkondon et al. 1998; Frazier et al. 1998; Hefft et al. 1999; Hatton & Yang, 2002).

Relatively high levels of α7-nAChRs are found in the hippocampus early in postnatal life (Adams et al. 2002). The receptors cocluster in part with GABAA receptors on filopodia, dendritic shafts, and somatic surfaces of hippocampal interneurons (Liu et al. 2001; Kawai et al. 2002), and the sites appear to become dually innervated by cholinergic and GABAergic fibres (Zago et al. 2006). A similar juxtaposition of α7-nAChRs and GABAA receptors occurs on chick ciliary ganglion (CG) neurons where nicotinic receptors are concentrated on somatic spines (Wilson Horch & Sargent, 1995; Shoop et al. 1999). Recent evidence has identified clusters of GABAA receptors near nAChRs on the cells and has shown that GABAergic terminals contact the neurons, along with the cholinergic fibres (Liu et al. 2006).

We used patch-clamp recordings from dissociated CG neurons and from interneurons in mouse hippocampal slices to examine the acute interactions of α7-nAChRs and GABAA receptors. The results show that activation of α7-nAChRs diminishes subsequent responses from GABAA receptors and that the effect depends on intracellular calcium–calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) in the postsynaptic cell. Moreover, spontaneous activation of α7-nAChRs by endogenous cholinergic activity in hippocampal slices has an ongoing tonic effect on GABA responses. These results identify a new modulatory role for α7-nAChRs on the postsynaptic cell.

Methods

Slice preparation

C57/BL6 mice of both sexes were used, ranging in age from postnatal day 9–14 (P9–14). All animal procedures performed were in accordance with the institutional guidelines and approved by the UCSD Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The animals were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (40 mg (kg body weight)−1). The brains were dissected rapidly, and 300 μm thick hippocampal slices were obtained in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) using a Vibratome (series 1000, Technical Products International Inc., St Louis, USA). The ACSF was saturated with 95% O2–5% CO2 and contained (mm): NaCl 119, KCl 2.5, CaCl2 2.5, MgSO4 1.3, NaH2PO4 1.0, NaHCO3 26.2 and glucose 11. Slices were maintained in the gas-saturated ACSF at room temperature for at least 1 h before use.

Dissociation of chick CG neurons

CG were isolated from White Leghorn chick embryos at embryonic day 14 (E14) and treated with 1.25 mg ml−1 collagenase in dissection buffer containing (mm): NaCl 136, KCl 3, Hepes 10, glucose 10 (PH 7.4), at 37°C for 8–12 min. After rinsing, ganglia were transferred to Minimum Essential Medium Eagle (MEM, Mediatech, Herndon, VA, USA) with 10% horse serum, 50 U ml−1 penicillin–streptomycin, and 3% embryonic eye extract. Individual neurons were obtained by gentle trituration and plated onto poly d-lysine treated coverslips (Liu & Berg, 1999a; Liu et al. 2006). Cells were used for recording 1–5 h after plating.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell recordings were obtained from interneurons in the CA1 stratum radiatum (SR) of fresh hippocampal slices as previously described (Zhang et al. 2003). Slices were perfused with gas-saturated ACSF at 2–3 ml min−1 at room temperature. Pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA) with a P-97 pipette puller (Sutter Instruments), and were filled with solution containing (mm): potassium gluconate 120, KCl 30, Hepes 10, Na2-phosphocreatine 10, ATP 4, GTP 0.3 and EGTA 1, and had a resistance of 4–6 MΩ. In all experiments using hippocampal slices, 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6-nitro-2,3-dioxo-benzo[f]quinoxaline-7-sulfonamide (NBQX) (20 μm), 2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV; 50 μm), atropine (2 μm), and edrophonium (100 μm) were included in the ACSF to block AMPA, NMDA, and muscarinic receptors, and acetylcholinesterase, respectively. Synaptic responses were evoked by concentric bipolar tungsten electrodes placed either in the SR or the stratum oriens (SO). GABA was delivered to neurons by positioning the tip of a glass pipette containing GABA over the dendritic fields of SR interneurons, and applying brief pulses of air pressure generated by a Picospritzer (Parker Hannifin Corp., Cleveland, OH, USA). Nicotine was applied similarly but separately. When the effects of gabazine were to be tested on the GABA response, gabazine was applied through the bath perfusion.

For experiments on CG neurons, recordings were performed in a solution containing (mm): NaCl 140, KCl 1, CaCl2 1, Hepes 10, MgCl2 1, glucose 10 and 10% horse serum with the pH adjusted to 7.4. Nicotine and GABA were delivered to the neuron by a large bore multibarrelled applicator (Zhang et al. 1994). Gabazine, when present, was first applied from a separate barrel of the multibarrelled applicator and then with GABA from a different barrel.

In all experiments, neurons were clamped at −70 mV by a MultiClamp 700A amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), and signals were recorded by pCLAMP 9.2 (Molecular Devices). Data were filtered at 2 kHz and sampled at 5 kHz; pipette capacitance and serial resistance were compensated.

Materials

White Leghorn chick embryos were obtained locally and maintained in a humidified incubator. C57/BL6 mice heterozygous for knockout of the α7-nAChR gene were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and used to establish a colony. Wild-type and homozygous knockout pups (determined by PCR analysis of DNA samples) were taken for experiments. Methyllycaconitine (MLA) was purchased from Tocris (Ellisville, MO, USA). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise indicated.

Statistics

Statistical significance was assessed by Student's paired t test or by analysis of variance (ANOVA) as indicated. Data are presented as the mean ±s.e.m.

Results

Depression of GABAA receptor responses on CG neurons by activation of α7-nAChRs

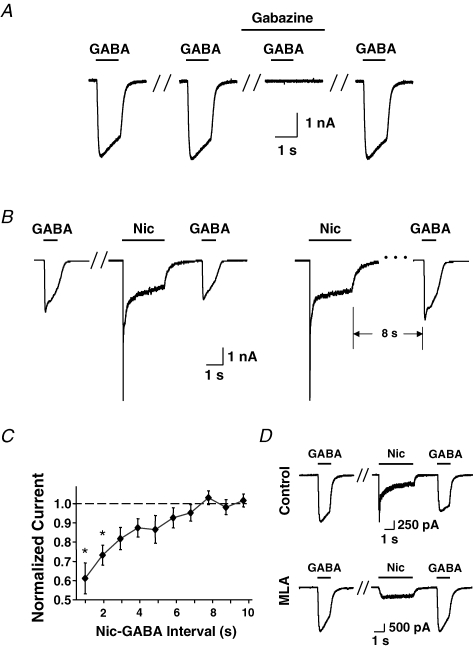

Freshly dissociated E14 chick CG neurons were examined with whole-cell patch-clamp recording techniques to identify acute effects of α7-nAChRs on GABAA receptors. Rapid application of GABA (100 μm) for 1 s induced a fast inward current, and the response could be reproducibly elicited at 1 min intervals (Fig. 1A). Blockade of the GABA-induced current by incubation in the GABAA receptor antagonist gabazine (10 μm) confirmed that the response was mediated by GABAA receptors. Rapid application of nicotine (20 μm) for 2–3 s prior to application of GABA caused a significant reduction in the amplitude of the GABA responses (Fig. 1B). The reduction reversed within 8 s following termination of the nicotine (Fig. 1C). Incubating the neurons in MLA (50 nm) throughout the test prevented the nicotine-induced reduction in the amplitude of GABA-induced currents (1.4 ± 0.3 nA for MLA alone and 1.4 ± 0.3 for MLA + nicotine; mean ±s.e.m., n = 8 in each case). MLA at this concentration is a specific inhibitor of α7-nAChRs, indicating that α7-nAChR activation was necessary for the nicotinic effect (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Nicotine application depresses GABA-induced responses in freshly dissociated chick CG neurons Nicotine (20 μm, 3 s) and GABA (100 μm, 1 s) were individually applied. A, stable GABA responses were elicited at 1 min intervals. The GABA-induced response was completely blocked by the specific GABAA receptor antagonist gabazine (10 μm) and fully recovered after washout. Pairs of hash marks here and below indicate 1 min intervals. B, GABA induced responses were attenuated after a 3 s nicotine application (left); allowing an 8 s lag after nicotine application allowed full recovery of the GABA response (right). C, compiled results showing the time course of recovery for GABA-induced current amplitudes after nicotine application (mean ±s.e.m.; n = 8 neurons). The response was significantly reduced by nicotine when the interval between nicotine and GABA application was ≤ 2 s *P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Dunnett's post hoc test. D, nicotine-induced depression of GABA responses (control) was abolished by the α7-nAChR antagonist MLA (50 nm). The residual nicotine-induced current in the presence of MLA (lower trace) results from heteromeric nAChRs containing α3 and other subunits (Vernallis et al. 1993).

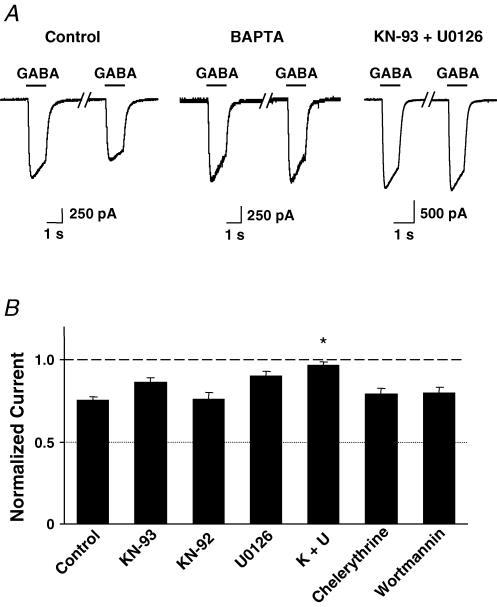

The mechanism by which α7-nAChR activation influences GABA responses was dissected by intracellular application of specific blockers. Calcium dependence was tested because α7-nAChRs have significant calcium permeability (Bertrand et al. 1993; Seguela et al. 1993). Introducing the calcium chelator BAPTA (11 mm) into the neuron via the recording pipette prevented nicotine application from affecting the GABA response (Fig. 2A). This focused attention on calcium-dependent pathways involving kinases. Infusion of the CaMKII antagonist KN-93 (10 μm) into the neuron via the recording pipette nominally produced partial blockade of the nicotine-induced reduction in GABA responses, but the effect did not reach statistical significance for the number of cells tested. The same was true for infusion of the MAPK antagonist U0126 (10 μm). Combining KN-93 and U0126, however, completely prevented the nicotine-induced effect (Fig. 2A and B). In contrast, KN-92, used as negative control for KN-93, had no effect. Infusing the protein kinase C blocker chelerythrine (10 μm) or the PI3K blocker wortmannin (100 nm) also had no effect, indicating that these kinases were not likely to be involved (Fig. 2B). The results show that activation of α7-nAChRs on CG neurons acts through calcium-dependent pathways involving CaMKII and MAPK to reversibly reduce GABAA receptor responses.

Figure 2.

Intracellular calcium, CaMKII and MAPK are required for α7-nAChR-mediated depression of GABAA receptor responses in CG neurons A, paired traces as in Fig. 1B showing GABA-induced responses 1 min before and 2 s after applying nicotine for 3 s using control solution (left), or solutions containing either 11 mm BAPTA (middle) or the CaMKII antagonist KN-93 plus the MAPK antagonist U0126 (right), both at 10 μm. B, compiled results obtained for GABA responses in the presence of nicotine after infusing the indicated compounds through the recording pipette; values are normalized to the response obtained in the absence of nicotine, and the error bars indicate s.e.m. (7–10 cells tested per condition). CaMKII blocker KN-93 (10 μm), MAPK blocker U0126 (10 μm), protein kinase C blocker chelerythrine (10 μm), PI3K blocker wortmannin (100 nm), negative control KN-92 (10 μm), and K + U (KN-93 + U0126, 10 μm). *P < 0.01 compared to control, one-way ANOVA, Dunnett's post hoc test; error bars indicate s.e.m.

Nicotinic depression of GABAergic IPSCs in mouse hippocampal interneurons

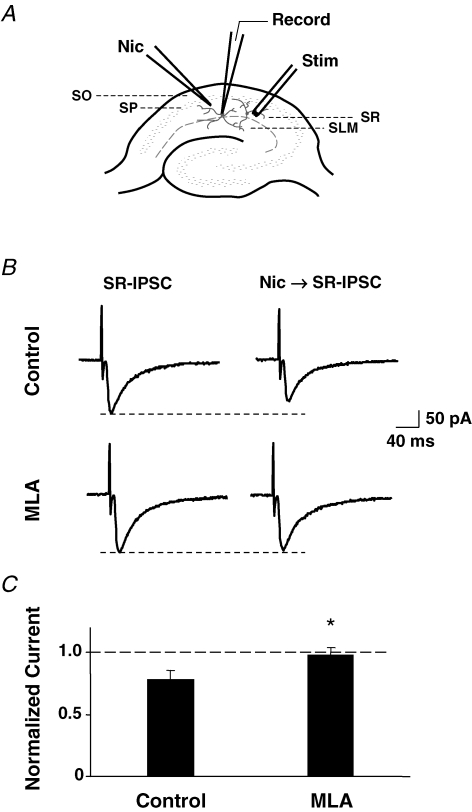

Hippocampal interneurons have significant numbers of α7-nAChRs coclustered with GABAA receptors on dendrites and filopodia. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed on interneurons in the SR of the CA1 region of hippocampal slices from P9–14 mice (Fig. 3A). NBQX (20 μm) and APV (50 μm) were applied to block AMPA and NMDA receptors, respectively. Stimulation of the SR with an extracellular concentric bipolar electrode elicited IPSCs in the interneuron (Fig. 3B). The IPSCs were blocked by gabazine (10 μm) as expected for responses generated by GABAA receptors (data not shown). Application of nicotine from a pipette placed about 0.1 mm from the cell body prior to stimulation of the SR caused a reduction in the amplitude of IPSCs elicited subsequently (Fig. 3B). The pipette position was chosen to optimize nicotine application to the dendritic tree and to avoid pressure-induced displacement of the soma. The reduction in IPSC amplitude was reversible, and was completely prevented when the slice was perfused with 50 nm MLA (Fig. 3B and C). The results indicate that activation of α7-nAChRs can reversibly diminish the response of synaptic GABAA receptors that produce the IPSCs.

Figure 3.

Nicotinic activation of α7-nAChR depresses GABAergic IPSCs in mouse hippocampal CA1 interneurons A, diagram showing electrode positions to elicit IPSCs by electrical stimulation in SR (Stim) while recording from an SR interneuron (Record). Nicotine 100 μm, 200 ms was delivered to the dendritic field of the neuron by glass pipette (Nic) 2–3 s before stimulation. SP, stratum pyramidale; SLM, stratum lacunosum moleculare. B, SR-elicited IPSCs before (SR-IPSC) and after (Nic → SR-IPSC) nicotine application in the absence (top traces) or presence (bottom traces) of 50 nm MLA. C, compiled results (mean ±s.e.m., n = 10 neurons) of IPSCs elicited in the presence of nicotine (± MLA) expressed as a fraction of the response in the absence of nicotine. *P < 0.01, Student's t test.

Activation of cholinergic fibres in situ depresses GABAergic IPSCs in hippocampal interneurons

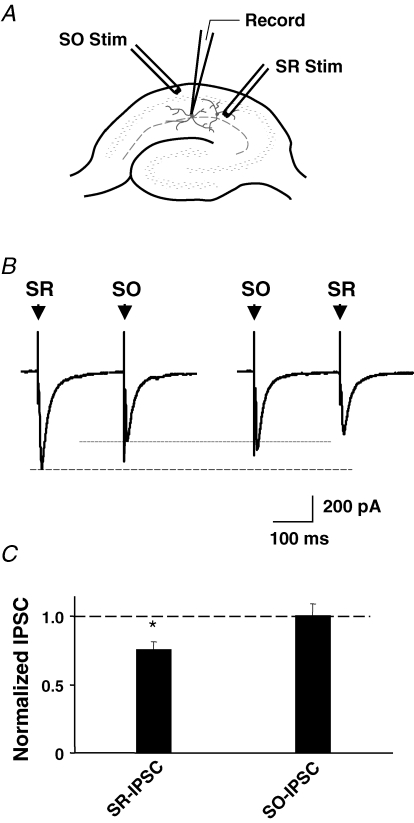

Cholinergic projections from the septum reach the SR by projecting through the SO of the CA1. Extracellular stimulation in the SO therefore can be used to release not only GABA from intrinsic GABAergic fibres but also ACh from invading cholinergic fibres (Maggi et al. 2003). To test the effect of cholinergic input on GABA responses, we placed one stimulating electrode in the SR and a second in the SO (Fig. 4A). NBQX, APV, atropine, and edrophonium (100 μm) were included to block AMPA, NMDA and muscarinic receptors, and cholinesterases, respectively. Pairs of IPSCs were elicited in an SR interneuron by stimulating the SO and SR sites 200 ms apart. Gabazine (10 μm) completely blocked the IPSCs, confirming they were generated by activation of GABAA receptors (data not shown). The stimulation protocol routinely employed six sets of paired stimuli at 1 min intervals using one stimulation order (e.g. SO and then SR), followed by another six sets with the stimulation order reversed. This pattern was repeated and yielded consistent results within a set and among sets. When the SO stimulation preceded SR stimulation in the pair, the SR-induced IPSC was smaller than when stimulation was applied in the reverse order (Fig. 4B). No reduction was seen if a delay of 2 s was interposed between the SO and SR pulses, indicating that the effect was transient (data not shown). No reduction was seen in the SO-induced IPSC when SR stimulation preceded SO stimulation (Fig. 4B and C). The results indicate that stimulation in the SO transiently reduces the amplitude of GABAergic IPSCs induced subsequently in SR interneurons.

Figure 4.

SO stimulation to activate cholinergic fibres depresses IPSCs elicited subsequently by SR stimulation A, diagram showing positions of stimulating (Stim) and recording electrodes (Record) in the SO and SR. B, pairs of IPSCs were induced by stimulating first one input (e.g. SR) and then the other (SO) after a 200 ms delay, and then repeating after a 1 min delay, and averaging 6-8 such trials. The stimulation order was then reversed and the process repeated. C, compiled results showing the mean amplitude (±s.e.m., n = 11 neurons) of an IPSC when it was elicited as the second of a pair, normalized for its amplitude when elicited first. When SO stimulation preceded SR stimulation, the SR-elicited IPSC (SR-IPSC) was significantly smaller than when the stimulation order was reversed. Stimulation order had no effect on SO-elicited IPSCs (SO-IPSC). *P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA, Dunnett's post hoc test.

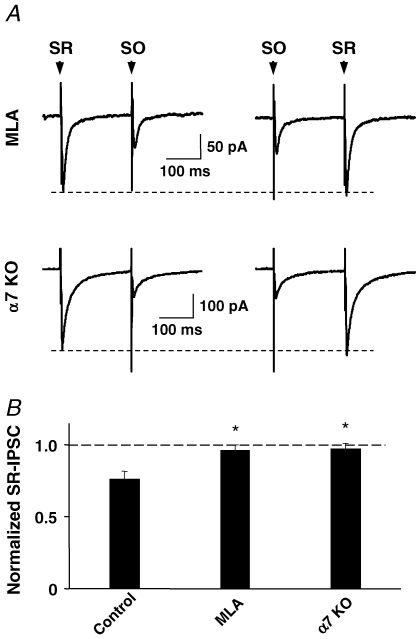

Two lines of evidence show that the SO-dependent reduction in GABAergic IPSC amplitude was mediated by α7-nAChRs. The first made use of MLA to block α7-nAChRs. In the presence of MLA, SO stimulation had no effect on subsequent SR-elicited IPSCs (Fig. 5A). The second approach employed α7-nAChR knockout mice (Orr-Urtreger et al. 1997). Stimulating the CA1 SO region of hippocampal slices from the knockout mice had no effect on subsequent IPSCs elicited in SR interneurons by stimulation of the SR, in contrast to wild-type (Fig. 5B). The results are consistent with SO stimulation recruiting cholinergic fibres that activate α7-nAChRs on SR interneurons, causing these receptors to produce a transitory reduction in GABAergic IPSC amplitude in the neurons.

Figure 5.

Knockout mice and nicotinic antagonists demonstrate that α7-nAChRs mediate the inhibitory effect of SO stimulation on SR-elicited IPSCs A, MLA (50 nm, upper traces) prevented SO stimulation from affecting the amplitude of SR-elicited IPSCs. SO stimulation also had no effect on SR-elicited IPSCs in hippocampal slices from α7-nAChR knockout mice (bottom traces). B, compiled data (mean ±s.e.m., n = 6–11 neurons) showing no effect of SO stimulation on SR-elicited IPCSs in the presence of MLA (MLA) or in α7-nAChR knockout slices (α7 KO), in contrast to wild-type slices in the absence of MLA (control). *P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Dunnett's post hoc test.

Postsynaptic site of action for α7-nAChRs mediating reduction of hippocampal IPSCs

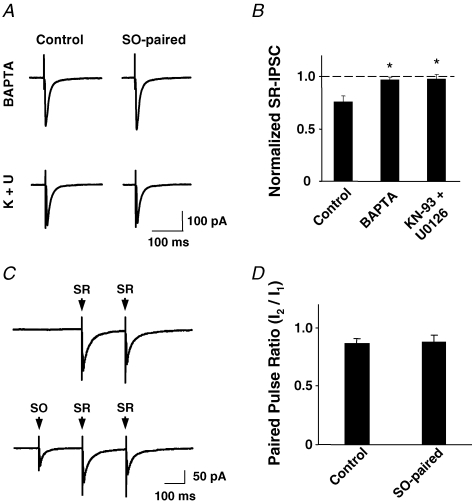

If activation of α7-nAChRs on the interneuron itself mediates the transient reduction of IPSC amplitude and utilizes the same mechanisms found in CG neurons, one would expect the process to be blocked by calcium chelators and inhibitors of CaMKII and MAPK. Indeed, infusing BAPTA (11 mm) through the recording electrode completely blocked the ability of SO stimulation to reduce the amplitude of IPSCs subsequently evoked in the SR interneuron (Fig. 6A). Similarly, infusing KN-93 (10 μm) plus U0126 (10 μm) completely blocked the effect (Fig. 6B). BAPTA infusion into SR interneurons had no effect in hippocampal slices from α7-nAChR knockout mice (data not shown), thereby excluding the possibility that the protection seen above resulted from a compensatory and independent enhancement of the GABAergic response. The results indicate that, as in CG neurons, a calcium-dependent process involving CaMKII and MAPK mediate the α7-nAChR-dependent reduction of IPSCs in hippocampal interneurons.

Figure 6.

Infusing a calcium chelator or blockers of CaMKII and MAPK into the patch-clamped neuron prevents SO stimulation from depressing SR-elicited IPSCs A, traces showing SR-elicited IPSCs alone (control) and after pairing with SO stimulation (SO-paired) as in Fig. 4. The cells were infused either with 11 mm BAPTA (upper traces) or 10 μm KN-93 + 10 μm U0126 (lower traces). B, quantification of changes in SR-elicited IPSC amplitude induced by pairing with a preceding SO stimulation, normalized for IPSC amplitude in the absence of pairing. Cells were infused with normal solution (Control) or solution containing either BAPTA or KN-93 + U0126 as indicated. Both treatments completely abolished the effect of SO stimulation on SR-elicited IPSCs, compared to controls. *P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA, Dunnett's post hoc test. C, traces showing paired SR-elicited IPSCs with (lower) or without (upper) a preceding stimulation in SO. D, quantification showing that SO stimulation did not affect the paired-pulse ratio of SR-evoked IPSC amplitudes. P > 0.05, Student's t test.

A second line of evidence supporting a direct action of α7-nAChRs on the postsynaptic cell was the finding that SO stimulation had no detectable presynaptic effects on GABA release. This was assessed by comparing the paired-pulse ratio for IPSCs in an interneuron elicited by two consecutive stimuli applied to the SR both before and after SO stimulation. Though SO stimulation reduced the amplitude of subsequent SR-elicited IPSCs, it did not change the paired-pulse ratio (Fig. 6C). It should be noted that the experiment would not detect all-or-none effects presynaptically, e.g. blockade of conduction in the presynaptic fibre. The results are clearly consistent, however, with the postsynaptic effect advanced above, namely that stimulation of cholinergic fibres in the SO activates α7-nAChRs on interneurons, turning on calcium-dependent kinase pathways to transiently reduce GABAA receptor responses.

Spontaneous α7-nAChR activity in hippocampal slices

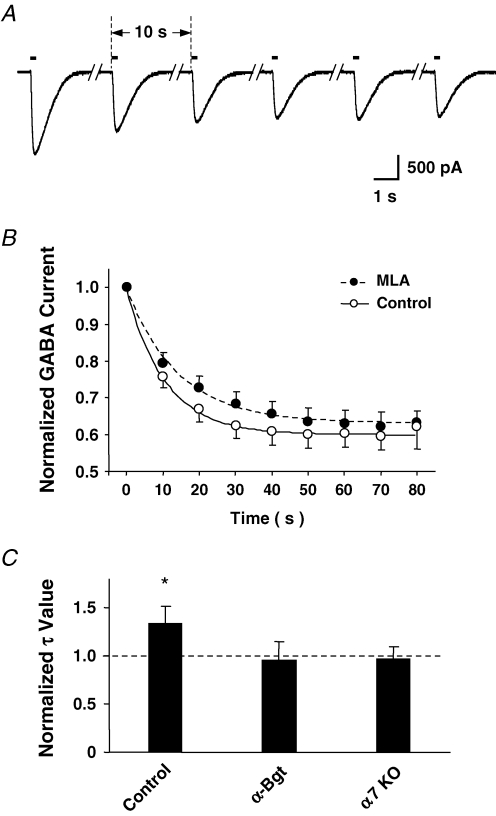

The stimulation experiments described above demonstrate that activation of α7-nAChRs can regulate GABAergic responses. The experiments reported here suggest that spontaneous agonist-induced activation of α7-nAChRs occurs in hippocampal slices and can provide ongoing regulation of GABAA receptor function.

GABA (100 μm) was applied to hippocampal slices from a glass pipette while perfusing the preparation with blockers for AMPA, NMDA and muscarinic receptors, as well as acetylcholinesterase (see above). This procedure elicited GABA-induced responses of consistent amplitude in SR interneurons when spaced at 1 min intervals. In contrast, application of GABA at 10 s intervals produced responses of decreasing amplitude (Fig. 7A). The time course of rundown had a τ-value (decay to 50%) of 10.3 ± 0.6 s (mean ±s.e.m.; n = 12 neurons). In the presence of 50 nm MLA to block α7-nAChRs, the τ-value increased to 14.8 ± 0.9 s (n = 11; Fig. 7B). The rundown completely reversed within 3–5 min (not shown). Pre-incubation of the slices with 100 nmα-bungarotoxin (αBgt), a slowly reversing antagonist of α7-nAChRs, prevented MLA from altering the time course of inactivation (Fig. 7C). MLA also had no effect on the time course in slices prepared from α7-nAChR knockout mice (Fig. 7C). Lastly, MLA had no detectable effect on isolated single GABA responses (not shown). The results are consistent with spontaneous activation of α7-nAChRs in the slice preparation exerting a low level of GABAA receptor regulation to cause greater use-dependent reversible rundown.

Figure 7.

Spontaneous activation of α7-nAChRs by endogenous agonist enhances rundown of GABAA receptors in hippocampal CA1 interneurons A, superimposed traces showing the currents induced by application of GABA (100 μm, 100 ms) at 10 s intervals (arrows). B, time course of changes in the mean IPSC amplitude normalized for the initial value seen in the presence (•) and absence (^) of 50 nm MLA. Time to 50% depression (τ) was 10.3 ± 0.6 s and 14.8 ± 0.9 s for control and MLA conditions, respectively. The curves represent the best fits of the data using the calculated time constants and standard exponential simulation. C, MLA significantly increased the τ-value (Control) normalized for that obtained in the absence of MLA, unless the slice was pretreated with αBgt (αBgt) or was obtained from α7-nAChR knockout mice (α7 KO). The results represent the mean ±s.e.m. with n = 8–13 neurons. *P < 0.01, Student's t test.

Discussion

The major findings reported here are that α7-nAChRs on the postsynaptic cell reversibly inhibit GABAA receptors and do so via calcium influx and activation of CaMKII and MAPK. The inhibition can be seen in autonomic neurons where α7-nAChRs are concentrated on the soma along with GABAA receptors, and on hippocampal interneurons where α7-nAChRs often cocluster with GABAA receptors on dendrites and filopodia. Activation of α7-nAChRs either by application of nicotine or by stimulation of cholinergic fibres reversibly decreases GABAergic IPSC amplitude in hippocampal interneurons. Chronic activation of α7-nAChRs by endogenous agonists appears to depress the ability of the neuron to sustain repeated GABAergic responses. These results identify a new mechanism by which nicotinic cholinergic pathways influence GABAergic signalling and thereby help shape the output of the system.

Freshly dissociated CG neurons provided a useful preparation for studying postsynaptic α7-nAChR effects on GABAA receptors because both receptor types are expressed in relative abundance on the soma and because presynaptic structures can be removed (McEachern et al. 1985; Engisch & Fischbach, 1990; Wilson Horch & Sargent, 1995; Shoop et al. 1999). Synaptic activation of α7-nAChRs is known to produce pronounced calcium influx in CG neurons (Shoop et al. 2001) and activation of both CaMKII and MAPK to drive downstream signalling (Liu & Berg, 1999b; Chang & Berg, 2001). The finding that inhibitors for both CaMKII and MAPK were required to block completely the α7-nAChR effects on GABA-induced currents raises the possibility that the two pathways operate in parallel. Alternatively, the inhibitors may not have had sufficient access to exert complete blockade individually.

The effects of α7-nAChRs on GABAergic IPSCs in hippocampal interneurons were shown both by applying nicotine directly to the cells and by stimulating endogenous cholinergic inputs to the cells. Both procedures reduced the amplitude of the evoked GABAergic IPSCs in SR interneurons. The latter paradigm provided a convenient system for examining mechanism, and revealed that the same components identified in the CG – calcium influx, CaMKII, and MAPK – were operative here, enabling α7-nAChRs to acutely and reversibly diminish the responsiveness of synaptic GABAA receptors. Blockade by the compounds also made unlikely an alternative explanation for the nicotinic effect on IPSCs, namely that activation of α7-nAChRs on distal dendrites might provide a local current shunt reducing the IPSC amplitude recorded in the soma. The blocking agents were effective when applied to the soma, and, moreover, would not themselves be expected to diminish α7-nAChR currents: in other systems these blockers preserve α7-nAChR responses (Liu & Berg, 1999b).

Though a significant fraction of α7-nAChRs on hippocampal interneurons are colocalized with GABAA receptors, the reverse is less true. Some populations of interneurons have few visible α7-nAChR clusters or express an excess of GABAA receptors compared to α7-nAChRs (Zago et al. 2006; Massey et al. 2006). Accordingly, nicotinic stimulation might be expected to have little effect on the whole-cell GABA-induced currents, which combine contributions from synaptic and extrasynaptic receptors. Nonetheless, spontaneous endogenous activation of α7-nAChRs measurably influenced the rate of inactivation observed for a series of closely spaced GABA-induced whole-cell currents. The effect was reversible and not large enough to be apparent when examining isolated single responses. That α7-nAChRs were responsible was demonstrated by showing blockade of the effect with low concentrations of MLA and confirming that MLA had no effect in hippocampal slices pretreated with αBgt to block α7-nAChRs or in slices from α7-nAChR knockout mice. The spontaneous activation of α7-nAChRs could have resulted either from the accumulation of ACh released from cholinergic fibres or from basal levels of choline in the preparation since both serve as agonists for the receptors (Alkondon et al. 1999).

Previous studies have emphasized the importance of presynaptic nicotinic receptors, particularly α7-nAChRs, in modulating GABAergic and glutamatergic transmission in the hippocampus (McGehee et al. 1995; Gray et al. 1996; Alkondon et al. 1997; Guo et al. 1998; Li et al. 1998; Radcliffe & Dani, 1998; Maggi et al. 2001, 2004; Mok & Kew, 2006). It is also clear that α7-nAChRs can contribute directly to postsynaptic responses and elevate intracellular calcium (Alkondon et al. 1998; Frazier et al. 1998; Hefft et al. 1999; Hatton & Yang, 2002; Khiroug et al. 2003). Together these α7-nAChRs can have complex effects, depending on the cell type affected (Ji & Dani, 2000). Globally, spontaneous nicotinic activity can drive giant depolarizing potentials, dependent on excitatory GABA in the developing hippocampus (Maggi et al. 2001; Le Magueresse et al. 2006), and recently it has been found that spontaneous nicotinic activity, via α7-nAChRs in part, drives the conversion of GABA excitation to inhibition during development with consequences for neuronal maturation (Liu et al. 2006).

The effects of α7-nAChRs on GABAergic signalling reported here are different from past reports in constituting a local and acute postsynaptic action that modulates GABAA receptors in a reversible manner. A recent study has demonstrated α7-nAChR responses from SR interneurons using slices from slightly older animals (Chang & Fischbach, 2006). The younger neurons examined here may have even higher levels of α7-nAChRs (Adams et al. 2002). Nicotine application did not induce visible currents in the present experiments presumably because the relatively distal and prolonged application of agonist would have induced little, if any, current in the soma, given the distance and susceptibility of α7-nAChRs to desensitization (Alkondon & Albuquerque, 1993; Zhang et al. 1994). Strong evidence for a postsynaptic site of action for α7-nAChRs in the present experiments came from infusion of blocking agents into the postsynaptic cell, which specifically blocked the α7-nAChR effects elicited by SO stimulation. Though the α7-nAChR-generated currents were too small to detect in the soma, the blockers were apparently able to diffuse into the dendrites and reach the sites where the calcium- and CaMKII/MAPK-dependent modifications of GABA responses would otherwise have occurred. Also supporting a postsynaptic site of α7-nAChR action was the observation that SO stimulation was unable to change the paired-pulse ratio of SR-elicited synaptic responses in the cell, as anticipated for most presynaptic effects. Notably, single SO stimuli were most effective at inducing α7-nAChR-dependent attenuation of SR-elicited IPSC amplitude. High frequency SO stimulation had no effect (data not shown), perhaps because of desensitization or because of a compensatory increase in GABA release mediated by presynaptic α7-nAChRs (Maggi et al. 2003).

The hippocampal experiments reported here were performed on slices from P9–14 animals. Activation of α7-nAChRs by endogenous agonist in P21–35 animals increases IPSC frequencies in SR interneurons (Mok & Kew, 2006). No effect on IPSC frequency was seen in the younger animals (Mok & Kew, 2006), and conversely, we saw no postsynaptic α7-nAChR effect on IPSC amplitude in the older animals (data not shown). The reasons for this are not clear but may reflect differences in the relative weighting of cholinergic input to pre- and postsynaptic α7-nAChRs as a function of age. Nicotine application to hippocampal slices from older animals has been reported to decrease the responsiveness of CA1 pyramidal neurons to GABA application, but the effect was thought to be indirect because no nicotine-induced currents were observed (Yamazaki et al. 2005). As noted above, however, nicotine application may activate nAChRs on pyramidal dendritic projections, which work through local calcium-dependent processes to regulate GABA responses, even though the nicotine-induced currents are not sufficient to be detected in the soma.

The juxtaposition of α7-nAChR clusters and GABAA receptors on developing hippocampal interneurons clearly positions α7-nAChRs for calcium-dependent regulation of GABAergic responses (Kawai et al. 2002; Zago et al. 2006). Finding discrete cholinergic terminals abutting the α7-nAChR clusters suggests focal transmission (Zago et al. 2006), though volume transmission may also contribute to activation (Descarries, 1998; Zoli et al. 1999a). It is striking that this positioning of α7-nAChRs and the potential for GABAA receptor regulation by nicotinic signalling is prominent at a time in postnatal development when spontaneous nicotinic activity drives conversion of GABAergic signalling from excitatory to inhibitory (Liu et al. 2006). The contribution of α7-nAChRs to the GABAergic conversion is qualitatively different and clearly distinct from the effects described here, but the capacity for acute, local regulation of GABAA receptors by α7-nAChRs may be particularly important for constraining GABAergic signalling during such a critical period.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kerri A. Massey and Jeffrey D. Schoelman for maintaining the breeding colony of mutant mice. Grant support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (NS012601 and NS035469). J.Z. is a Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program Postdoctoral Fellow.

References

- Adams CE, Broide RS, Chen Y, Winzer-Serhan UH, Henderson TA, Leslie FM, Freedman R. Development of the α7 nicotinic cholinergic receptor in rat hippocampal formation. Dev Brain Res. 2002;139:175–187. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00547-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Albuquerque EX. Diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat hippocampal neurons. I. Pharmacological and functional evidence for distinct structural subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:1455–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Pereira EFR, Albuquerque EX. α-Bungarotoxin- and methyllycaconitine-sensitive nicotinic receptors mediate fast synaptic transmission in interneurons of rat hippocampal slices. Brain Res. 1998;810:257–263. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00880-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Pereira EFR, Barbosa CTF, Albuquerque EX. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activation modulates γ-aminobutyric acid release from CA1 neurons of rat hippocampal slices. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:1396–1411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Pereira EFR, Eisenberg HM, Albuquerque EX. Choline and selective antagonists identify two subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that modulate GABA release from CA1 interneurons in rat hippocampal slices. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2693–2705. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-07-02693.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannon AW, Decker MW, Holladay MW, Curzon P, Donnelly-Roberts D, Puttfarcken PS, Bitner RS, Diaz A, Dickenson AH, Porsolt RD, Williams M, Arneric SP. Broad-spectrum, non-opioid analgesic activity by selective modulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Science. 1998;279:77–81. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5347.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand D, Galzi JL, Devillers-Thiery A, Bertrand S, Changeux J-P. Mutations at two distinct sites within the channel domain M2 alter calcium permeability of neuronal α7 nicotinic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:6971–6975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.6971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K, Berg DK. Voltage-gated channels block nicotinic regulation of CREB phosphorylation and gene expression in neurons. Neuron. 2001;32:855–865. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00516-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Q, Fischbach GD. An acute effect of neuregulin 1β to suppress α7-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11295–11303. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1794-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C, Booker TK, Allen RS, Grady SR, Whiteaker P, Marks MJ, Salminen O, Tritto T, Butt CM, Allen WR, Stitzel JA, McIntosh JM, Boulter J, Collins AC, Heinemann SF. The β3 nicotinic receptor subunit: a component of α-conotoxin MII-binding nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that modulate dopamine release and related behaviors. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11045–11053. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-11045.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA. Overview of nicotinic receptors and their roles in the central nervous system. Bio Psychiatry. 2001;49:166–174. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descarries L. The hypothesis of an ambient level of acetylcholine in the central nervous system. J Physiol (Paris) 1998;92:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(98)80013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drisdel RC, Green WN. Neuronal α-bungarotoxin receptors are α7 subunit homomers. J Neurosci. 2000;20:133–139. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00133.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engisch KL, Fischbach GD. The development of ACh- and GABA-activated currents in normal and target-deprived embryonic chick ciliary ganglia. Dev Biol. 1990;139:417–426. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90310-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian-Fine R, Skehel P, Errington ML, Davies HA, Sher E, Stewart MG, Fine A. Ultrastructural distribution of the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7993–8003. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-07993.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier CJ, Buhler AV, Weiner JL, Dunwiddie TV. Synaptic potentials mediated via α-bungarotoxin-sensitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8228–8235. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08228.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray R, Rajan AS, Radcliffe KA, Yakehiro M, Dani JA. Hippocampal synaptic transmission enhanced by low concentrations of nicotine. Nature. 1996;383:713–716. doi: 10.1038/383713a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J-Z, Tredway TL, Chiappinelli VA. Glutamate and GABA release are enhanced by different subtypes of presynaptic nicotinic receptors in the lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1963–1969. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-01963.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton GI, Yang QZ. Synaptic potentials mediated by α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in supraoptic nucleus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:29–37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00029.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefft S, Hulo S, Bertrand D, Muller D. Synaptic transmission at nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat hippocampal organotypic cultures and slices. J Physiol. 1999;510:709–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.769ab.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji D, Dani JA. Inhibition and disinhibition of pyramidal neurons by activation of nicotinic receptors on hippocampal interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:2682–2690. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai H, Zago W, Berg DK. Nicotinic α7 receptor clusters on hippocampal GABAergic neurons: regulation by synaptic activity and neurotrophins. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7903–7912. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-07903.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khiroug L, Giniatullin R, Klein RC, Fayuk D, Yakel JL. Functional mapping and Ca2+ regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channels in rat hippocampal CA1 neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9024–9031. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09024.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambe EK, Olausson P, Horst N, Taylor JR, Aghajanian GK. Hypocretin and nicotine excite the same thalamocortical synapses in prefrontal cortex: correlation with improved attention in rat. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5225–5229. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0719-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviolette SR, van der Kooy D. The neurobiology of nicotine addiction: bridging the gap from molecules to behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:55–65. doi: 10.1038/nrn1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Magueresse C, Safiulina V, Changeux JP, Cherubini E. Nicotine modulation of network and synaptic transmission in the immature hippocampus investigated with genetically modified mice. J Physiol. 2006;576:533–546. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.117572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, McClernon FJ, Rezvani AH. Nicotinic effects on cognitive function: behavioral characterization, pharmacological specification, and anatomic localization. Psychopharmacol. 2006;184:523–539. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy RB, Aoki C. α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors occur at postsynaptic densities of AMPA receptor-positive and -negative excitatory synapses in rat sensory cortex. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5001–5015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-05001.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Rainnie DG, McCarley RW, Greene RW. Presynaptic nicotinic receptors facilitate monoaminergic transmission. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1904–1912. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01904.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu QS, Berg DK. Extracellular calcium regulates responses of both α3- and α7-containing nicotinic receptors on chick ciliary ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999a;82:1124–1132. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.3.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q-S, Berg DK. Actin filaments and the opposing actions of CaM kinase II and calcineurin in regulating α7-containing nicotinic receptors on chick ciliary ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 1999b;19:10280–10288. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10280.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Ford B, Mann MA, Fischbach GD. Neuregulins increase α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and enhance excitatory synaptic transmission in GABAergic interneurons of the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5660–5669. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05660.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Neff RA, Berg DK. Sequential interplay of nicotinic and GABAergic signaling guides neuronal development. Science. 2006;314:1610–1613. doi: 10.1126/science.1134246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi L, Le Magueresse C, Changeux J-P, Cherubini E. Nicotine activates immature ‘silent’ connections in the developing hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2059–2064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437947100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi L, Sher E, Cherubini E. Regulation of GABA release by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the neonatal rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2001;536:89–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi L, Sola E, Minneci F, Le Magueresse C, Changeux JP, Cherubini E. Persistent decrease in synaptic efficacy induced by nicotine at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses in the immature rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2004;559:863–874. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.067041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansvelder HD, McGehee DS. Cellular and synaptic mechanisms of nicotine addiction. J Neurobiol. 2002;53:606–617. doi: 10.1002/neu.10148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margiotta J, Pugh P. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the nervous system. In: Maue RA, editor. Molecular and Cellular Insights to Ion Channel Biology. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 269–302. [Google Scholar]

- Marubio LM, del Mar Arroyo-Jimenez M, Cordero-Erausquin M, Lena C, Le Novere N, de Kerchove d'Exaerde A, Huchet M, Damaj MI, Changeux J-P. Reduced antinociception in mice lacking neuronal nicotinic receptor subunits. Nature. 1999;398:805–810. doi: 10.1038/19756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey KA, Zago WM, Berg DK. BDNF up-regulates nicotinic receptor levels on subpopulations of hippocampal interneurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;33:381–338. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEachern AE, Margiotta JF, Berg DK. GABA receptors on chick ciliary ganglion neurons in vivo and in cell culture. J Neurosci. 1985;5:2690–2695. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-10-02690.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee D, Heath MJ, Gelber S, Role LW. Nicotine enhancement of fast excitatory synaptic transmission in CNS by presynaptic receptors. Science. 1995;269:1692–1696. doi: 10.1126/science.7569895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee DS, Role LW. Physiological diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed by vertebrate neurons. Ann Rev Physiol. 1995;57:521–546. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.002513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok MH, Kew JNC. Excitation of rat hippocampal interneurons via modulation of endogenous agonist activity at the α7 nicotinic ACh receptor. J Physiol. 2006;574:699–710. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.104794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse PA, Potter A, Levin ED. Nicotinic system involvement in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Implications for therapeutics. Drugs Aging. 1997;11:206–228. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199711030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr-Urtreger A, Goldner FM, Saeki M, Lorenzo I, Goldberg L, De Biasi M, Dani JA, Patrick JW, Beaudet AL. Mice deficient in the α7 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor lack α-bungarotoxin binding sites and hippocampal fast nicotinic currents. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9165–9171. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09165.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Zoli M. Nicotinic receptors in aging and dementia. J Neurobiol. 2002;53:641–655. doi: 10.1002/neu.10102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Zoli M, Lena C, Bessis A, Lallemand Y, Le Novere N, Vincent P, Pich EM, Brulet P, Changeux J-P. Abnormal avoidance learning in mice lacking functional high-affinity nicotine receptor in the brain. Nature. 1995;374:65–67. doi: 10.1038/374065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe KA, Dani JA. Nicotinic stimulation produces multiple forms of increased glutamatergic synaptic transmission. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7075–7083. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07075.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raggenbass M, Bertrand D. Nicotinic receptors in circuit excitability and epilepsy. J Neurobiol. 2002;53:580–589. doi: 10.1002/neu.10152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Mleux B, Eggermann E, Bisetti A, Bayer L, Machard D, Jones BE, Muhlethaler M, Serafin M. Nicotinic enhancement of the noradrenergic inhibition of sleep-promoting neurons in the ventrolateral preoptic area. J Neurosci. 2004;24:63–67. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0232-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguela P, Wadiche J, Dineley-Miller K, Dani JA, Patrick JW. Molecular cloning, functional properties, and distribution of rat brain α7: a nicotinic cation channel highly permeable to calcium. J Neurosci. 1993;13:596–604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00596.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoop RD, Chang KT, Ellisman MH, Berg DK. Synaptically-driven calcium transients via nicotinic receptors on somatic spines. J Neurosci. 2001;21:771–781. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-00771.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoop RD, Martone ME, Yamada N, Ellisman MH, Berg DK. Neuronal acetylcholine receptors with α7 subunits are concentrated on somatic spines for synaptic signaling in embryonic chick ciliary ganglia. J Neurosci. 1999;19:692–704. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00692.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernallis AB, Conroy WG, Berg DK. Neurons assemble acetylcholine receptors with as many as three kinds of subunits while maintaining subunit segregation among receptor subtypes. Neuron. 1993;10:451–464. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90333-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson Horch HL, Sargent PB. Perisynaptic surface distribution of multiple classes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on neurons in the chicken ciliary ganglion. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7778–7795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-07778.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki Y, Jia Y, Hamaue N, Sumikawa K. Nicotine-induced switch in the nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms of facilitation of long-term potentiation induction. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:845–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zago WM, Massey KA, Berg DK. Nicotinic activity stabilizes convergence of nicotinic and GABAergic synapses on filopodia of hippocampal interneurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;31:549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Liu C, Miao H, Gong Z-H, Nordberg A. Postnatal changes in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α2, α3, α4, α7 and β2 subunits genes expression in rat brain. Int J Devl Neurosci. 1998;16:507–518. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(98)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZW, Vijayaraghavan S, Berg DK. Neuronal acetylcholine receptors that bind α-bungarotoxin with high affinity function as ligand-gated ion channels. Neuron. 1994;12:167–177. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Wang HK, Ye CQ, Ge W, Chen Y, Jiang ZL, Wu CP, Poo MM, Duan S. ATP released by astrocytes mediates glutamatergic activity-dependent heterosynaptic suppression. Neuron. 2003;40:971–982. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00717-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoli M, Jansson A, Sykova E, Agnati LF, Fuxe K. Volume transmission in the CNS and its relevance for neuropsychopharmacology. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999a;20:142–150. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01343-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoli M, Picciotto MR, Ferrari R, Cocchi D, Changeux J-P. Increased neurodegeneration during ageing in mice lacking high-affinity nicotine receptors. EMBO J. 1999b;18:1235–1244. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]