Abstract

We have investigated the nature of the Ca2+ entry supporting [Ca2+]i oscillations in human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells by examining the roles of recently described store-operated Ca2+ entry proteins, Stim1 and Orai1. Knockdown of Stim1 by RNA interference (RNAi) reduced the frequency of [Ca2+]i oscillations in response to a low concentration of methacholine to the level seen in the absence of external Ca2+. However, knockdown of Stim1 did not block oscillations in canomical transient receptor potential 3 channel (TRPC3)-expressing cells and did not affect Ca2+ entry in response to arachidonic acid. The effects of knockdown of Stim1 could be reversed by inhibiting Ca2+ extrusion with a high concentration of Gd3+, or by rescuing the knockdown by overexpression of Stim1. Similarly, knockdown of Orai1 abrogated [Ca2+]i oscillations, and this was reversed by use of high concentrations of Gd3+; however, knockdown of Orai1 did not affect arachidonic acid-activated entry. RNAi targeting 34 members of the transient receptor potential (TRP) channel superfamily did not reveal a role for any of these channel proteins in store-operated Ca2+ entry in HEK293 cells. These findings indicate that the Ca2+ entry supporting [Ca2+]i oscillations in HEK293 cells depends upon the Ca2+ sensor, Stim1, and calcium release-activated Ca2+ channel protein, Orai1, and provide further support for our conclusion that it is the store-operated mechanism that plays the major role in this pathway.

Activation of phospholipase C-coupled receptors results in both intracellular Ca2+ release and increased influx of Ca2+ across the plasma membrane. In many instances, the influx of Ca2+ occurs through the capacitative or store-operated route (Putney, 1986; 1997; Parekh & Penner, 1997; Parekh & Putney, 2005). When supramaximal receptor activation induces large, sustained increases in [Ca2+]i, the evidence for capacitative calcium entry is fairly straightforward. However, when lower, more physiological concentrations of receptor agonists induce regenerative [Ca2+]i oscillations, both the role and nature of the associated Ca2+ entry is a matter of some debate. Specifically, it has been suggested that another, non-capacitative pathway involving arachidonic acid-activated channels provides the Ca2+ entry necessary to drive [Ca2+]i oscillations (Shuttleworth, 1999; Shuttleworth et al. 2004). We recently published pharmacological evidence indicating that in human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells, maintenance of [Ca2+]i oscillations required capacitative or store-operated Ca2+ entry (Bird & Putney, 2005). However, the specificity of this pharmacological approach has been questioned (Mignen et al. 2005). In addition, in a recent report, Yan et al. (2006) found no effect of knockdown of the store-operated Ca2+ entry protein, Stim1, on [Ca2+]i oscillations in intestinal cells of Caenorhabditis elegans. These investigators concluded that store-operated entry was not required for Ca2+ signalling under physiological conditions, but rather functioned in pathophysiological conditions of extreme store depletion (Yan et al. 2006). Therefore, in the current study, we utilized a molecular approach to investigate the Ca2+ entry mechanism involved in [Ca2+]i oscillations in HEK293 cells. We utilized RNA interference (RNAi) to knock down two recently described molecular components of capacitative calcium entry, Stim1 (Roos et al. 2005; Liou et al. 2005) and Orai1 (Feske et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2006; Vig et al. 2006b). In confirmation of the finding of Roos et al. (2005), knockdown of Stim1, but not the structurally related Stim2, significantly decreased store-operated Ca2+ entry, as assessed with both thapsigargin and a supramaximal concentration of methacholine. Knockdown of Stim1 also significantly reduced the frequency of [Ca2+]i oscillations in response to low concentrations of methacholine. The specificity of Stim1 was demonstrated by the failure of Stim1 knockdown to reduce canomical transient receptor potential 3 channel (TRPC3)-dependent oscillations, or arachidonic acid-activated Ca2+ entry. Knockdown of the calcium release-activated calcium channel component, Orai1, similarly inhibited oscillations. These findings show that two proteins that play essential roles in capacitative calcium entry, Stim1 and Orai1, are essential in the signalling mechanism for [Ca2+]i oscillations under conditions of physiological stimulation strengths. They also provide further support for our conclusion that the store-operated pathway provides the Ca2+ entry supporting [Ca2+]i oscillations in HEK293 cells.

Methods

Cell culture

HEK293 cells (ATCC) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 2 mm glutamine and maintained in a humidified 95% air–5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. HEK293 cells stably expressing a green fluorescent protein-tagged TRPC3 were also maintained in culture as described by Trebak et al. (2003). In preparation for cDNA transfection or small inhibitory RNA (siRNA) knockdown, cells were transferred to six-well plates and allowed to grow to ∼90% confluence. In preparation for Ca2+ measurements, cells were cultured to about 70% confluence and then transferred onto 30 mm round glass coverslips (#1 thickness) at two different cell densities (Bird & Putney, 2005). Specifically, 0.5 ml either a 400 000 cells ml−1 (high density) or 60 000 cells ml−1 (low density) cell suspension was transferred to the centre of the coverslip, and the cells were left to attach for a period of 12 h. Additional DMEM was then added to the coverslip, and the cells were maintained in culture for an additional 36 h before use for calcium measurements. Unless specified, cells were grown in the high density condition; as previously described, low density conditions were required for reproducible responses to arachidonic acid (Bird & Putney, 2005).

Plasmids

Stim1 with the enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) fused to the N-terminus was obtained from Tobias Meyer, Stanford University. Full-length Stim2 cDNA plasmid was purchased from Origene in the pCMV6-XL5 vector, and EYFP-C1 from Clontech (Mountain View, CA, USA).

siRNA knockdown

HEK293 cells were plated in a six-well plate on day 1. On day 2, cells were transfected with siRNA (100 nm) against Stim1 (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA), Orai1 (Invitrogen) or siCONTROL (Dharmacon) using Metafectene (Biontex Laboratories GmbH, Martinsried/Planegg, Germany; 7 μl per well), and including siGLO (Dharmacon) as a marker. The sequence of the siRNA against Stim1 was: agaaggagcuagaaucucac (Mercer et al. 2006); for Orai1 it was: cccuucggccugaucuuuaucgucu (Mercer et al. 2006). After a 6 h incubation period, the medium bathing the cells was replaced by DMEM and maintained in culture. On day 3, siRNA-treated cells were optionally transfected with cDNA for Stim1 tagged with EYFP, Stim2 plus EYFP or EYFP alone as described below. On day 4, cells were transferred to 30 mm glass coverslips in preparation for Ca2+ measurements as described above, which were performed on day 5 or 6.

cDNA transfection

HEK293 cells were plated in a six-well plate on day 1. On day 2, cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; 2 μl per well) with cDNA for EYFP, EYFP-tagged Stim1 or EYFP-tagged Stim2. After a 6 h incubation period, the medium bathing the cells was replaced by complete DMEM and maintained in culture. On day 3, cDNA-treated cells were transferred to 30 mm glass coverslips in preparation for Ca2+ measurements as described above, which were performed on day 4 or 5. The concentrations of plasmids used were 0.5 μg well−1 for EYFP–Stim1, 0.1 μg well−1 for EYFP and 2 μg well−1 for Stim2.

Single-cell calcium measurement

Fluorescence measurements were made with HEK293 cells loaded with the calcium sensitive dye, fura-5F, as previously described (Bird & Putney, 2005). Briefly, cells plated on 30 mm round coverslips and mounted in a Teflon chamber were incubated in DMEM with 1 μm of the acetoxymethyl ester (AM) form of fura-5F (fura-5F/AM, Molecular Probes, USA) at 37°C in the dark for 25 min. For [Ca2+]i measurements, cells were bathed in Hepes-buffered salt solution (HBSS) at room temperature (21°C) containing (mm): NaCl 120, KCl 5.4, Mg2SO4 0.8, Hepes 20, CaCl2 1.8 and glucose 10; pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. Nominally Ca2+-free solutions were HBSS with no added CaCl2. Fluorescence images of the cells were recorded and analysed with a digital fluorescence imaging system (InCyt Im2, Intracellular Imaging Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA). Fura-5F fluorescence was monitored by alternatively exciting the dye at 340 and 380 nm, and collecting the emission wavelength at 520 nm. Changes in intracellular calcium are expressed as the ratio of fura-5F fluorescence due to excitation at 340 and 380 nm (F340/F380). Before starting the experiment, regions of interests identifying transfected cells expressing the EYFP tag were created by observing cells at a 530 nm emission wavelength and illuminated with 477 nm excitation light. Typically, 25–35 cells were monitored per experiment. In all cases, ratio values have been corrected for contributions by autofluorescence, which is measured after treating cells with 10 μm ionomycin and 20 mm MnCl2. Quantitative analysis of agonist-induced oscillation rates was carried out as previously described (Bird & Putney, 2005). Rates of oscillation were calculated on responding cells only, and the fraction of responding cells is reported in each case. Responding cells were those producing at least one immediate transient rise in [Ca2+]i following application of methacholine.

Calcium entry RNAi screen

By monitoring agonist- and thapsigargin-induced CCE in HEK293 cells, an RNAi screen was performed using SMARTpool siRNA reagents (Dharmacon). The screen involved transfection with SMARTpool siRNA, a mixture of four siRNAs designed and synthesized by the vendor. In preparation for siRNA knockdown, HEK293 cells were plated in a 96-well plate (at 10 000 cells per well) (day 1). On day 2, cells were transfected with various siRNAs using metafectene, and including siGLO (Dharmacon) as a marker. After 6 h incubation, the medium bathing the cells was replaced by complete DMEM. Transfected cells were maintained in culture until day 4 when [Ca2+]i measurements were performed.

The effects of siRNA on Ca2+ entry were screened using cells seeded in 96-well plates and a fluorescence imaging plate reader (FLIPR384, Molecular Devices, CA, USA). Agonist- and thapsigargin-induced [Ca2+]i changes were measured in transfected HEK293 cells grown on a 96-well plate and loaded with a calcium-sensitive ‘no wash’ dye (FLIPR Calcium 3 Assay kit, Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Fluorescence was monitored on a fluorescence imaging plate reader, FLIPR384, by exciting the calcium indicator at 488 nm, and collecting emission fluorescence at 510–570 nm.

Materials

Methacholine was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA), thapsigargin from Alexis (San Diego, CA, USA), fura-5F/AM from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA) and arachidonic acid, (5,8,11,14-eicosatetraenoic acid) was obtained from BioMol (PA, USA). SMARTpool combinations of four siRNAs against Stim1, Stim2 and 34 TRP genes, as well as a control siRNA (siCONTROL) and fluorescent siRNA (siGLO) were obtained from Dharmacon.

Results and Discussion

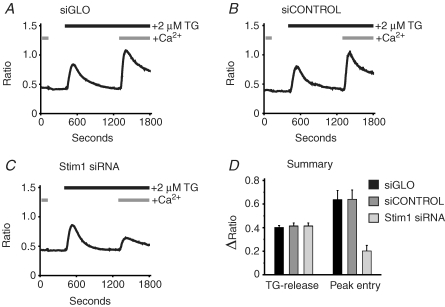

Figure 1 demonstrates the effectiveness of functional knockdown of capacitative calcium entry in HEK293 cells utilizing an siRNA duplex as previously described (Mercer et al. 2006). As shown in Fig. 1, treatment of HEK293 cells with Stim1 siRNA reduced the thapsigargin-induced calcium entry with no effect on the depletion of intracellular calcium by thapsigargin (Fig. 1C). It is interesting that the lack of effect on the size of the thapsigargin-sensitive pool indicates that HEK293 cells can maintain normal endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ stores with reduced (but not zero) store-operated Ca2+ entry. Treatment of cells with the siRNA constructs siGLO or siCONTROL had no effect on either thapsigargin-induced calcium release or calcium entry (Fig. 1A and B, respectively). Data summarizing the effects of each condition on the peak calcium release and peak calcium entry are shown in Fig. 1D.

Figure 1.

Effects of RNAi knockdown on thapsigargin-induced calcium responses in HEK293 cells using single-cell analysis HEK293 cells transfected with siGLO (A), siCONTROL (B) or Stim1 siRNA (C) were loaded with fura-5F and treated with thapsigargin (TG) in the absence and then the presence of 1.8 mm extracellular Ca2+. For each condition, data are summarized in D for the amplitude of thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ release in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (TG-release), and the amplitude of thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ entry in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ (Peak entry). The data are means ±s.e.m. for six (A and B) and three (C) independent experiments.

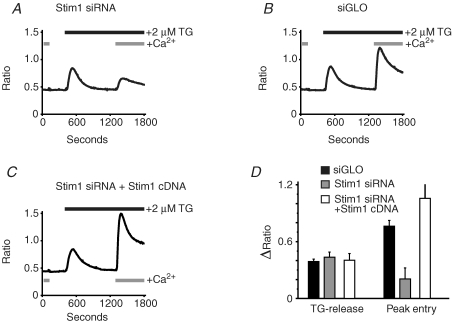

Two approaches can be used to ensure that the effects of a particular siRNA result specifically from reduction in expression of the targeted gene. Multiple siRNAs can be employed. However, a preferable strategy is to demonstrate that the effects of gene knockdown can be reversed or ‘rescued’ by restoring the targeted gene. Initially we engineered a construct of Stim1 in which several residues within the siRNA-targeted sequence were silently mutated (i.e. without changing the predicted amino acid sequence). This construct successfully reversed the effects of knockdown of store-operated entry by siRNA (data not shown). However, in subsequent experiments, we found that overexpression of the wild-type Stim1 (with N-terminal EYFP) also rescued store-operate entry. We reason that this happens because the siRNA probably does not completely knock down all message, and thus with the strong cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter in pcDNA3, sufficient message persists to restore a normal complement of Stim1. This is the construct used for the experiments in Fig. 2, where we demonstrate that the knockdown effect of Stim1 siRNA on thapsigargin-induced calcium entry can be rescued by subsequent transient expression of Stim1 cDNA in siRNA-treated cells (compare Fig. 2A and 2C). Effects of siRNA knockdown and the subsequent Stim1 rescue on peak calcium release and calcium entry induced by thapsigargin are summarized in Fig. 2D. Using this same approach (transfection of cDNA constructs in siRNA-treated cells), we also demonstrate that, unlike Stim1, Stim2 is unable to rescue the thapsigargin-induced calcium entry (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Thapsigargin-induced calcium entry can be rescued by over expression of Stim1 As described in the Methods, HEK293 cells transfected with Stim1 siRNA (A and C) and siGLO (B), were subsequently transfected with cDNA for EYFP (A and B) or EYFP–Stim1 (C). The cells were then loaded with fura-5F and treated with thapsigargin (TG) in the absence and then the presence of 1.8 mm extracellular Ca2+. For each condition, data are summarized in D for the amplitude of thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ release in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (TG-release), and the amplitude of thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ entry in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ (Peak entry). The data are means ±s.e.m. for three independent experiments.

Figure 3.

Thapsigargin (TG) induced calcium entry cannot be rescued by over expression of Stim2 As described in the Methods, HEK293 cells transfected with siGLO (A) or Stim1 siRNA (B and C), were subsequently transfected with cDNA for EYFP (A and B) or Stim2 together with EYFP (C). The cells were then loaded with fura-5F and treated with thapsigargin (TG) in the absence and then the presence of 1.8 mm extracellular Ca2+. For each condition, data are summarized in D for the amplitude of thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ release in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (TG-release), and the amplitude of thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ entry in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ (Peak entry). The data are means ±s.e.m. for three independent experiments. Analysis of variance followed by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test revealed that for entry, siGLO was significantly greater than either Stim1 siRNA or Stim1 siRNA + Stim2 siRNA (P < 0.01), but the latter were not significantly different from one another (P > 0.05).

Effect of Stim1 manipulations on agonist-induced Ca2+ oscillations in HEK293 cells

Thus far, we have confirmed findings from other laboratories that knocking down the levels of Stim1 in HEK293 cells substantially reduces the calcium entry signal activated under maximal stimulus conditions with thapsigargin, and by use of a rescue protocol, demonstrated that the effects of the specific siRNA duplex we have employed are specific for effects on Stim1 expression. However, the relevance of findings with complete Ca2+ store depletion by thapsigargin to signalling mechanisms with agonists at physiological stimulation strengths has been rightly questioned (Shuttleworth, 1999; van Rossum et al. 2004). Thus, we next wanted to use these same molecular approaches to investigate the Ca2+ entry pathway underlying a more physiologically relevant [Ca2+]i response (i.e. agonist-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations).

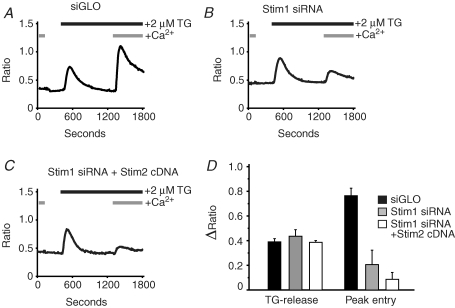

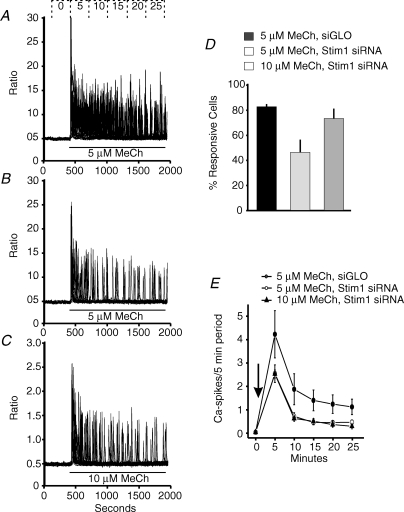

In experiments summarized in Fig. 4, we have characterized the effect of Stim1 siRNA on methacholine-induced calcium oscillations in HEK293 cells. As previously reported (Bird & Putney, 2005), treatment of fura-5F-loaded HEK293 cells with 5 μm methacholine in the presence of 1.8 mm extracellular Ca2+ results in a sustained, or slowly declining oscillatory Ca2+ response in the majority of cells (Fig. 4A). As previously described (Bird & Putney, 2005), the characteristics of this Ca2+ response to 5 μm methacholine are that ∼80% of the cells respond (Fig. 4D) and with an oscillatory response that is sustained over the 25 min period tested (Fig. 4E). By contrast, the oscillations in HEK293 cells treated with Stim1 siRNA in response to 5 μm methacholine were not sustained but transient (Fig. 4B and E). This would be consistent with the loss of a calcium entry required to support oscillations. However, as indicated in Fig. 4D, the percentage of responding cells under these conditions falls to ∼45%. These two characteristics, reduced responsiveness and transient oscillatory frequency, bare the hallmarks of an agonist response observed with a lower agonist concentration (see data for response to 1 μm methacholine by Bird & Putney (2005)).

Figure 4.

Effect of Stim1 RNAi knockdown on oscillatory calcium response in HEK293 cells HEK293 cells transfected with siGLO (A) or Stim1 siRNA (B and C) were loaded with fura-5F and treated with low concentrations of methacholine (MeCh) in Hepes-buffered salt solution containing 1.8 mm extracellular calcium. A, typical calcium response of a field of siGLO-transfected HEK293 cells to 5 μm MeCh. B and C, typical calcium response of a field of Stim1 siRNA transfected HEK293 cells to 5 and 10 μm MeCh, respectively. D, summarized data of the percentage responding cells observed in A–C (means ±s.e.m. for four independent experiments). E, summarized calcium oscillation frequency data of the effects of 5 μm (•) MeCh (added at arrow) in siGLO transfected HEK293 cells, and 5 μm (^) and 10 μm (▴) MeCh (added at arrow) in Stim1 siRNA transfected HEK293. The data are means ±s.e.m. of four independent experiments.

The mechanism for the partial decrease in the percentage of cells responding to 5 μm methacholine due to treatment with siRNA against Stim1 is not known. It is unlikely to be due to transfection in general, or RNAi in general, because neither the siGLO controls, nor siRNA against Orai1 had a similar effect. We were unable to reverse this effect of Stim1 siRNA by overexpressing EYFP–Stim1. Thus, it may represent an off-target effect due to reduction in expression of another gene in the muscarinic receptor signalling pathway. To address this as yet unexplained effect of Stim1 knockdown, we tested higher concentrations of methacholine that would result in a higher percentage of responding cells. As shown in Fig. 4D, increasing the methacholine concentration to 10 μm gave a similar percentage of responding cells compared to the control 5 μm response, yet the resulting oscillations were still transient (Fig. 4C and E).

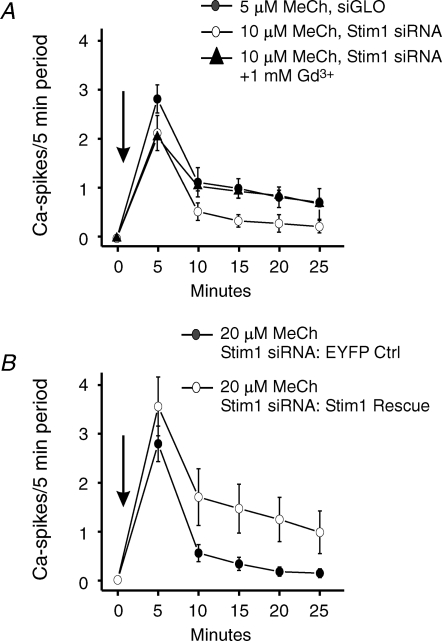

The above findings are consistent with a primary effect of Stim1 knockdown on loss of calcium entry necessary for sustained oscillations. To further evaluate this interpretation, we investigated the effects of ‘Gd3+ insulation’ on the oscillatory calcium response in Stim1 knockdown cells. That is, we incubated HEK293 cells in the presence of a high concentration of GdCl3 (1 mm), such that transmembrane calcium fluxes across the plasma membrane in both directions were prevented. Under these conditions, HEK293 cells do not lose intracellular calcium to the extracellular space, and agonist-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations are sustained despite the absence of calcium entry (Sneyd et al. 2004; Bird & Putney, 2005). As shown in Fig. 5A, the transient oscillatory calcium response observed with 10 μm methacholine in Stim1 siRNA-treated cells is now sustained in the presence of 1 mm GdCl3. Thus, the primary effect of Stim1 knockdown on agonist-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations is to cause loss of the calcium entry necessary to sustain them. As a final proof of this idea, we transiently expressed Stim1 in these same Stim1 siRNA-treated cells with the result that the sustained oscillatory calcium response to methacholine was now rescued (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

A sustained oscillatory calcium response to methacholine (MeCh) can be maintained in Stim1 siRNA-treated HEK293 cells by ‘Gd3+ insulation’ or by expression of Stim1 A, HEK293 cells transfected with siGLO (•) or Stim1 siRNA (^,▴) were loaded with fura-5F and treated with low concentrations of MeCh in Hepes-buffered salt solution (HBSS) containing 1.8 mm extracellular calcium. The summarized calcium oscillation frequency data are shown for siGLO-transfected cells responding to 5 μm MeCh (•) and Stim1 siRNA transfected cells responding to 10 μm MeCh (^,▴) (MeCh added at arrow). For one set of Stim1 siRNA treated cells (▴), the cells were treated under ‘Gd3+ insulation’ conditions (nominally calcium free HBSS supplemented with 1 mm GdCl3). The data are means ±s.e.m. of four independent experiments. B, HEK293 cells transfected with Stim1 siRNA were subsequently transfected with cDNA for enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP; ^) or EYFP–Stim1 (•). Fura-5F-loaded cells were then treated with 20 μm MeCh in HBSS containing 1.8 mm extracellular calcium. The summarized calcium oscillation frequency data for the MeCh response (added at arrow) are shown. The data are means ±s.e.m. of three independent experiments.

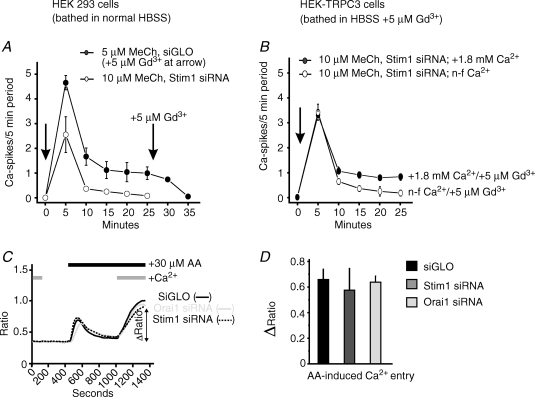

As a test for the specificity of Stim1 for supporting oscillatory calcium responses through store-operated calcium entry, we examined the effects of Stim1 siRNA in HEK293 cells stably expressing TRPC3. Previously, we demonstrated that TRPC3-expressing cells can support methacholine-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations even when the endogenous store-operated calcium entry process is blocked by low concentrations of Gd3+. As shown in Fig. 6A, inhibiting store-operated calcium entry with 5 μm Gd3+ blocks sustained oscillatory calcium response in control, wild-type HEK293 cells. By contrast, TRPC3-expressing HEK293 cells transfected with Stim1 siRNA and incubated in the presence of 5 μm Gd3+ still produce sustained oscillations in response to methacholine (Fig. 6B). This oscillatory response is dependent on the presence of extracellular Ca2+ because in parallel experiments performed under nominally calcium-free conditions, the rate of oscillations was significantly less (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

RNAi knockdown of Stim1 does not prevent a sustained oscillatory response to methacholine in the presence of TRPC3, nor does it reduce the calcium entry response to arachidonic acid A, HEK293 cells transfected with siGLO (•) or Stim1 siRNA (^) were loaded with fura-5F and treated with low concentrations of methacholine (MeCh) in Hepes-buffered salt solution (HBSS) containing 1.8 mm extracellular calcium. The summarized calcium oscillation frequency data are shown for siGLO-transfected cells responding to 5 μm MeCh (•) and Stim1 siRNA transfected cells responding to 10 μm MeCh (^) (MeCh added at arrow). After a 25 min MeCh response period in siGLO-transfected cells, 5 μm Gd3+ was added to demonstrate that the oscillatory response could be blocked. The data are means ±s.e.m. of three independent experiments. B, in parallel with the experiments performed in A, HEK293 cells stably expressing HTRPC3 (HEK–TRCPC3 cells) were transfected with Stim1 siRNA, loaded with fura-5F and treated with 10 μm MeCh in HBSS containing 5 μm GdCl3 (to block store-operated calcium entry) and with either 1.8 mm extracellular calcium present (•), or nominally calcium free (^). The summarized calcium oscillation frequency data are shown. The data are means ±s.e.m. of three independent experiments. C, as described in the Methods, HEK293 cells transfected with siGLO Orai1 siRNA or Stim1 siRNA were plated at low density, loaded with fura-5F and treated with 30 μm arachidonic acid (AA). The initial treatment with AA was in nominally calcium-free HBSS, and then 1.8 mm extracellular calcium was added back to monitor calcium entry. The data presented are means from three independent experiments. D, summarized data for AA-induced calcium entry (▵ ratio) shown in C. Data are means ±sem for three independent experiments.

As demonstrated previously (Shuttleworth, 1997; Shuttleworth & Thompson, 1998; Luo et al. 2001a, b), HEK293 cells also exhibit a calcium entry process that can be activated by treatment with arachidonic acid. This calcium entry response is considered a non-store-operated pathway, and has a pharmacological profile distinct from the store-operated one (Luo et al. 2001a, b), and does not appear to support agonist-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations in HEK293 cells (Bird & Putney, 2005). Thus we carried out experiments to determine whether Stim1 plays a role in mediating the effects of arachidonic acid. As shown in Fig. 6C, treatment of HEK293 cells with Stim1 siRNA did not appear to have any influence on the calcium signalling response to arachidonic acid.

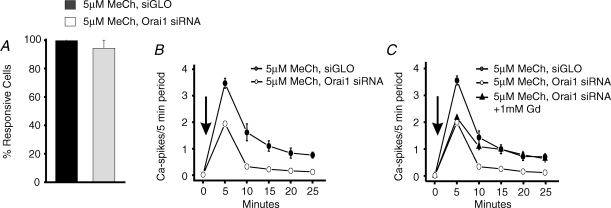

Effects of knockdown of Orai1 and TRP channels

In addition to Stim1, capacitative or store-operated Ca2+ entry depends upon a plasma membrane protein, Orai1 (Feske et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2006; Vig et al. 2006b). Recent findings indicate that Orai1 probably functions as a subunit of the store-operated channel itself (Yeromin et al. 2006; Prakriya et al. 2006; Vig et al. 2006a). As shown in Fig. 7, knockdown of Orai1 by RNAi (Mercer et al. 2006) significantly reduced the frequency of [Ca2+]i oscillations without reducing the percentage of cells responding to methacholine (Fig. 7A and B). This effect was due to reduction of Ca2+ entry because the inhibition resulting from knockdown of Orai1 was prevented by use of 1 mm Gd3+ to prevent both Ca2+ entry and Ca2+ extrusion (Fig. 7C). Finally, similar to the findings for Stim1, knockdown of Orai1 by RNAi did not affect arachidonic acid-induced Ca2+ entry (Fig. 6C).

Figure 7.

Effect of Orai1 RNAi knockdown on oscillatory calcium response in HEK293 cells HEK293 cells transfected with siGLO or Orai1 siRNA were loaded with fura-5F and treated with low concentrations of methacholine (MeCh) in Hepes-buffered salt solution (HBSS) containing 1.8 mm extracellular calcium. A, summarized data of the percentage cells responding to 5 μm MeCh (means ±s.e.m. for four independent experiments). B, summarized calcium oscillation frequency data on the effects of 5 μm (•) MeCh (added at arrow) in siGLO-transfected HEK293 cells, and 5 μm (^) MeCh (added at arrow) in Orai1 siRNA-transfected HEK293. The data are means ±s.e.m. of four independent experiments. C, summarized calcium oscillation frequency data are shown for siGLO- (•) and Orai1 siRNA (^,▴)-transfected cells responding to 5 μm methacholine (MeCh added at arrow). For one set of Orai1 siRNA-treated cells (▴), the cells were treated under ‘Gd3+ insulation’ conditions (nominally calcium free HBSS supplemented with 1 mm GdCl3). The data are means ±s.e.m. of three independent experiments.

These data are consistent with a role for Stim1 and Orai1 in store-operated entry, and in their essential role in maintaining [Ca2+]i oscillations in HEK293 cells. However, recent studies have implicated other channel proteins, specifically members of the TRPC ion channel family, as components of the Stim1-regulated store-operated channels in HEK293 cells (Huang et al. 2006) and platelets (Lopez et al. 2006). Thus, we carried out an RNAi-based screen of 34 different members of the TRP channel superfamily in HEK293 cells, using a FLIPR384 96-well real-time plate reader assay (see Methods). The genes targeted for knockdown by RNAi are listed in Table 1. Because of the size of the screen, negative results were not followed by biochemical assessment of protein knockdown. However, because of the use of a combination of four siRNAs, the likelihood of success with this approach is assumed to be quite good. As a positive control, we included a set of four siRNAs directed against Stim1 provided by the same commercial source, as well as Stim2 (the congener of Stim1).

Table 1.

Accession numbers of genes targeted for knockdown by RNAi

| Accession numbers |

|---|

| TRP channels |

| 6 TRPCs: NM_003304; NM_003305; NM_016179; NM_012471; |

| NM_004621; NM_020389 |

| 8 TRPMs: NM_002420; NM_003307; NM_020952; NM_017636; |

| NM_014555; NM_017662; NM_017672; NM_024080 |

| 6 TRPVs: NM_018727; NM_016113; NM_145068; NM_021625; |

| NM_019841; NM_018646 |

| 4 TRPPs (PKDs): NM_000297; NM_016112; NM_014386; |

| NM_006071 |

| TRPA1: NM_007332 |

| 2 MCOLNs (Mucolipins): NM_020533; XM_351266 |

| Sperm-specific calcium channels |

| 4 CATSPERs: NM_053054; NM_172095; NM_178019; XM_371237 |

| Two-pore channels |

| 2 TPCNs: NM_017901; NM_139075 |

| Voltage-gated channel-like |

| VGCNL1: NM_052867 |

| Calcium sensors |

| Stim1: NM_003156 |

| Stim2: NM_020860 |

The table lists 34 different members of the TRP channel superfamily that was targeted in the RNAi screen shown in figure 8.

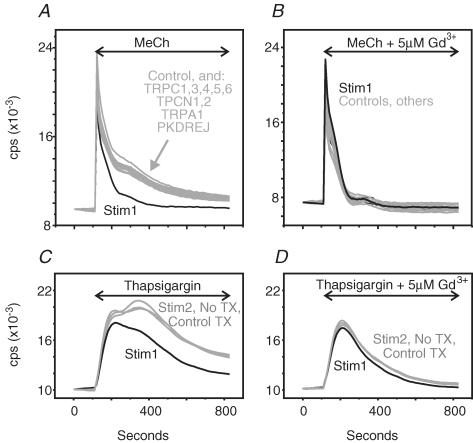

In the 96-well format, we found that by including a series of control wells, by including wells examining only Ca2+ release, and with replicates for each condition, we could assess about 10 different genes on a single plate with high reproducibility. Each screen was carried out with methacholine as well as thapsigargin to activate entry, and no differences were found between these two modes of stimulation. Figure 8A illustrates results for one plate with genes for nine cation channels and Stim1. Knockdown of Stim1 always resulted in significant reduction in the sustained phase of the response to methacholine, while for all 34 of the targeted channels, as well as Stim2, no significant effect was observed. The results in Fig. 8B show that this effect of Stim1 knockdown is lost when Ca2+ entry is blocked by 5 μm Gd3+.

Figure 8.

Characterization of the effects of RNAi knockdown on [Ca2+]i signalling responses to methacholine in HEK293 cells HEK293 cells grown in a 96-well well plate were transfected with siRNA against various targets (see Table 1), including Stim1 and Stim2. [Ca2+]i responses to 300 μm methacholine (MeCh) or 2 μm thapsigargin (TG) were monitored in the presence of 1.8 mm extracellular Ca2+ (A and C), or after addition of 5 μm Gd3+ to block Ca2+ entry (B and D). The data presented are from a single experiment, with each trace the average response from two wells. The data are representative of three similar experiments.

Conclusions

Together, our data confirm recent studies implicating Stim1, a Ca2+-binding protein located in the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum, as a potential Ca2+ sensor that initiates the process of store-operated Ca2+ entry. In contrast with the findings of Liou et al. (2005) and consistent with the findings of Roos et al. (2005), we found no evidence of such a role for Stim2; knockdown of Stim2 had no effect on Ca2+ signalling in HEK293 cells and, more significantly, Stim2 could not rescue [Ca2+]i responses after knockdown of Stim1. We have provided the first demonstration of an essential role for Stim1 and also Orai1 in the mechanism of [Ca2+]i signalling with physiological stimulus strength, when [Ca2+]i levels undergo oscillations. We have also demonstrated for the first time that TRPC3 channels and arachidonic acid-activated channels, both of which are activated downstream of phospholipase C, but not by Ca2+-store depletion, do not require Stim1.

While this work was under review, a publication appeared by Mignen et al. (2007) proposing a role for Stim1 in arachidonic acid-activated current in HEK293 cells. In contrast to the findings reported here, these authors reported suppression of arachidonate-activated currents by knockdown of Stim1. The reason for these discrepant results is not clear. However, interestingly, Mignen et al. (2007) also reported that it was specifically Stim1 in the plasma membrane that supported the arachidonate-activated currents. In our experiments in which we rescued [Ca2+]i oscillations following Stim1 knockdown, we utilized an EYFP–Stim1 construct which we (Mercer et al. 2006) and others (Liou et al. 2005) have shown does not traffic to the plasma membrane. Thus, it is unlikely that the role of Stim1 shown in our current study involves regulation of arachidonic acid-activated currents.

The current findings extend and support our previous conclusions on the nature of the Ca2+ entry mechanism that supports [Ca2+]i oscillations in this model system. Previously, we reported that it was predominantly if not exclusively the store-operated pathway that supported [Ca2+]i oscillations. That argument was based primarily on pharmacological properties of the store-operated pathway. Here we utilized a molecular criterion – the requirement for Stim1 and Orai1 – to further support this conclusion. The conclusion drawn by Yan et al. (2006) regarding the lack of a role for store-operated entry in C. elegans intestinal cell oscillations may be specific for that particular cell type, and at present should probably not be assumed to be a general property. The current study supports our previous conclusion (Bird & Putney, 2005) that [Ca2+]i oscillations are dependent on store-operated channels in the HEK293 cell model, but our results with TRPC3 over-expressing cells show that [Ca2+]i oscillations can be supported by non-store-operated channel mechanisms. Thus, we believe it is important to consider the question of the nature of regulated Ca2+ entry responsible for [Ca2+]i oscillations or other important response patterns independently for each particular cell type, receptor type or physiological process. The advent of molecular players in the store-operated pathway provides powerful tools for such investigations. With these and other tools, we can continue to probe the molecular and cellular processes that integrate plasma membrane Ca2+ fluxes with the complex [Ca2+]i oscillations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Elizabeth Murphy and Dave Miller who read the manuscript and provided helpful comments. This work was supported by funds from the Intramural Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Science (NIEHS) and NIH.

References

- Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Capacitative calcium entry supports calcium oscillations in human embryonic kidney cells. J Physiol. 2005;562:697–706. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.077289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;441:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GN, Zeng W, Kim JY, Yuan JP, Han L, Muallem S, Worley PF. STIM1 carboxyl-terminus activates native SOC, Icrac and TRPC1 channels. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1003–1010. doi: 10.1038/ncb1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE, Jr, Meyer T. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez J, Salido GM, Pariente JA, Rosado JA. Interaction of STIM1 with endogenously expressed human canonical TRP1 upon depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28254–28264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo D, Broad LM, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Signaling pathways underlying muscarinic receptor-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations in HEK293 cells. J Biol Chem. 2001a;276:5613–5621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007524200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo D, Broad LM, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Mutual antagonism of calcium entry by capacitative and arachidonic acid-mediated calcium entry pathways. J Biol Chem. 2001b;276:20186–20189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100327200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer JC, DeHaven WI, Smyth JT, Wedel B, Boyles RR, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Large store-operated calcium-selected currents due to co-expression of Orai1 or Orai2 with the intracellular calcium sensor, Stim1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24979–24990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604589200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. Stim1 regulates Ca2+ entry via arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective (ARC) channels without store-depletion or translocation to the plasma membrane. J Physiol. 2007 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.122432. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignen O, Thompson JL, Yule DI, Shuttleworth TJ. Agonist activation of arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective (ARC) channels in murine parotid and pancreatic acinar cells. J Physiol. 2005;564:791–801. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.085704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh AB, Penner R. Store depletion and calcium influx. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:901–930. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh AB, Putney JW., Jr Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:757–810. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya M, Feske S, Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Rao A, Hogan PG. Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature. 2006;443:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature05122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney JW., Jr A model for receptor-regulated calcium entry. Cell Calcium. 1986;7:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(86)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney JW., Jr . Capacitative Calcium Entry. Austin, TX: Landes Biomedical Publishing; 1997. pp. 1–210. [Google Scholar]

- Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, Velicelebi G, Stauderman KA. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:435–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth TJ. Arachidonic acid activates the noncapacitative entry of Ca2+ during [Ca2+]i oscillations. J Biol Chem. 1997;271:21720–21725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.21720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth TJ. What drives calcium entry during [Ca2+]i oscillations?– challenging the capacitative model. Cell Calcium. 1999;25:237–246. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1999.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth TJ, Thompson JL. Muscarinic receptor activation of arachidonate-mediated Ca2+ entry in HEK293 cells is independent of phospholipase C. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32636–32643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth TJ, Thompson JL, Mignen O. ARC channels: a novel pathway for receptor-activated calcium entry. Physiology (Bethesda) 2004;19:355–361. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00018.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneyd J, Tsaneva-Atanasova K, Yule DI, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. Control of calcium oscillations by membrane fluxes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1392–1396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303472101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trebak M, Bird GS, McKay RR, Birnbaumer L, Putney JW., Jr Signaling mechanism for receptor-activated TRPC3 channels. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16244–16252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rossum DB, Patterson RL, Kiselyov K, Boehning D, Barrow RK, Gill DL, Snyder SH. Agonist-induced Ca2+ entry determined by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2323–2327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308565100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig M, Beck A, Billingsley JM, Lis A, Parvez S, Peinelt C, Koomoa DL, Soboloff J, Gill DL, Fleig A. CRACM1 multimers form the ion-selective pore of the CRAC channel. Curr Biol. 2006a;16:2073–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig M, Peinelt C, Beck A, Koomoa DL, Rabah D, Koblan-Huberson M, Kraft S, Turner H, Fleig A, Penner R, Kinet JP. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science. 2006b;312:1220–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.1127883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X, Xing J, Lorin-Nebel C, Estevez AY, Nehrke K, Lamitina T, Strange K. Function of a STIM1 homologue in C. elegans: evidence that store-operated Ca2+ entry is not essential for oscillatory Ca2+ signaling and ER Ca2+ homeostasis. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:443–459. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeromin AV, Zhang SL, Jiang W, Yu Y, Safrina O, Cahalan MD. Molecular identification of the CRAC channel by altered ion selectivity in a mutant of Orai. Nature. 2006;443:226–229. doi: 10.1038/nature05108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SL, Yeromin AV, Zhang XH, Yu Y, Safrina O, Penna A, Roos J, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. Genomewide RNAi screen of Ca2+ influx identifies genes that regulate Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9357–9362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603161103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]