Abstract

The expression of the mRNA encoding galanin message-associated peptide (GMAP) in human keratinocytes is upregulated by lipopolysaccharides and exposure to Candida albicans. GMAP has growth-inhibiting activity against C. albicans and inhibits the budded-to-hyphal-form transition, establishing GMAP as a possible new component of the innate immune system.

The commensal organism Candida albicans resides on epithelial surfaces and is the major fungal pathogen in humans (11). In immunocompromised individuals, infections caused by C. albicans constitute a serious clinical problem (6). The pathogenicity of C. albicans is due to its different growth forms: the highly proliferative yeast (budded) form and the hyphal form supporting invasion into the host. The budded-to-hyphal-form transition is an important virulence factor of C. albicans (8). Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) participate in the innate immune response by providing a rapid first line of defense against pathogens. The fact that neuropeptides, like AMPs, are in general amphipathic molecules may explain the recent findings that several neuropeptides display antimicrobial activity (for a review, see reference 2).

Galanin, a 29-amino-acid neuropeptide (16), is processed from a 123-amino-acid precursor molecule, pre-pro galanin (ppGAL), which contains a signal peptide, the mature galanin peptide, and a carboxy-terminal 59-amino-acid galanin message-associated peptide (GMAP) (Fig. 1A). Galanin has been shown to be widely distributed in the central and peripheral nervous systems where it elicits diverse biological responses by binding to three known galanin receptors (10, 17, 18). For GMAP, no major physiological functions and receptors have been identified.

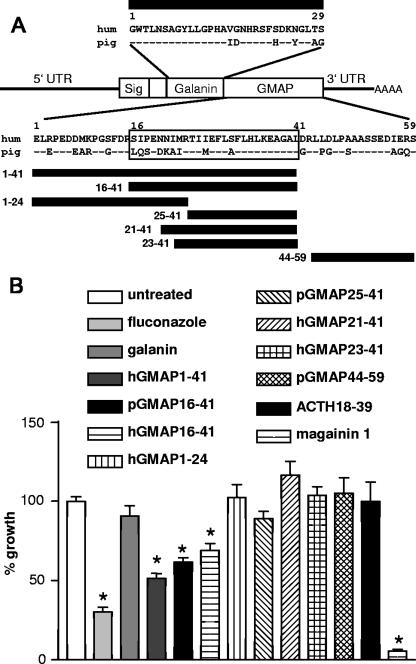

FIG. 1.

(A) Structure of the human ppGAL mRNA, sequences of galanin and GMAP, and alignment of the protein sequence of GMAP. The minimal peptide sequence affecting C. albicans growth is boxed. Sig, signal peptide; UTR, untranslated region; hum, human. Horizontal bars indicate the synthetic peptide fragments used in antifungal assays. (B) Effect of peptides on the growth of C. albicans. Percent growth refers to the untreated culture. Cultures were treated for 16 h at 30°C with either water (untreated), fluconazole (32 μM; n = 8), galanin (6.3 μM; n = 6), human GMAP (1-41) (4.3 μM; n = 8), porcine GMAP (16-41) (4.1 μM; n = 9), human GMAP (16-41) (4 μM; n = 6), human GMAP (1-24) (4 μM; n = 5), human GMAP (25-41) (4 μM; n = 5), human GMAP (21-41) (4 μM; n = 3), human GMAP (23-41) (4 μM; n = 6), porcine GMAP (44-59) (13 μM; n = 2), ACTH (18-39) (24.3 μM; n = 2), or magainin 1 (4.15 μM; n = 9). n indicates independent experiments with triple values. *, significant effect on growth with P of <0.01 (Dunnet's multiple comparison test). Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean.

Recently, ppGAL mRNA was detected in the epidermis, hair follicles, sweat glands, and around the blood vessels of human skin (7). In vitro receptor autoradiography detected galanin-binding sites around blood vessels and sweat glands of the dermis but not in the epidermis (7), indicating a non-receptor-mediated function of ppGAL in this outermost barrier of the body.

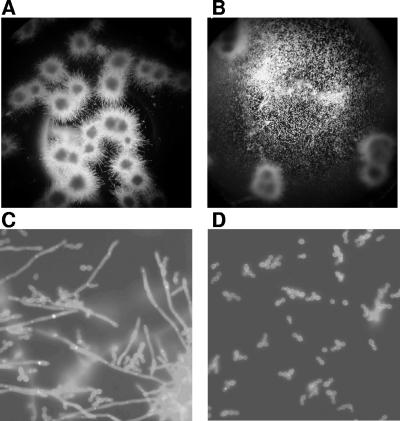

A mix containing three human synthetic peptides—galanin, GMAP (1-41), and GMAP (44-59) (all 40 μg/ml)—caused no significant growth inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, or Corynebacterium jeikeium as determined by the BacTiter-Glow microbial viability assay (Promega; data not shown). By contrast, the same galanin-GMAP mix caused a significant reduction in the growth of C. albicans K2 (1 × 103 to 3 × 103 CFU/ml; Sabouraud dextrose broth, 16 h at 30°C; BacTiter-Glow assay). Treatment with single-peptide GMAP (1-41) (20 μg/ml), but not galanin (20 μg/ml), resulted in a significant growth reduction (48.7%) of C. albicans K2 (Fig. 1B) as well as the laboratory strains C. albicans SC 5314 and CBS 5983 and two clinical C. albicans isolates from human skin. We were able to narrow the antimicrobial core sequence to GMAP (16-41) (Fig. 1). Further N-terminal and C-terminal truncations led to loss of antimicrobial activity. Porcine and human GMAP (16-41) had the same effect, indicating that the antifungal activity of GMAP is conserved across species. The antifungal activity of GMAP (16-41) occurs at a concentration of 12 μg/ml. However, GMAP is not as potent as the control peptide magainin I, which reduced the growth of C. albicans by more than 90%. Higher concentrations of GMAP (16-41), up to 50 μg/ml, did not increase its growth-inhibiting effect. In accordance with the literature, adenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (18-39) did not affect the growth of C. albicans (Fig. 1B) (3). Examination of cultures of C. albicans in RPMI medium [0.3 g/liter l-glutamine, 0.165 M 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid pH 7.0; 37°C] after 24 h showed a budded-to-hyphal transition (Fig. 2A and C). For better microscopic examination of hyphal structures, some representative cultures were stained with calcofluor white (5) (Fig. 2C and D). Treatment of these cultures with GMAP (1-41) (4 μM) or GMAP (16-41) (4 μM, human and porcine) resulted in a significant inhibition of this yeast-to-hyphal transformation (Fig. 2). This inhibition was still visible, albeit weaker, with 2 μM GMAP (1-41) or (16-41) but was lost with 1 μM concentrations of the peptides. The concentration of GMAP necessary to affect the growth features of C. albicans is in the range of other neuropeptides with antimicrobial activity (1 pM to 100 μM) (2). To our knowledge only the neuropeptide α-MSH has been reported to have an inhibitory effect on germ tube formation of C. albicans (3). That report suggested that the candidacidal effect of alpha melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) is mediated through induction of cyclic adenosine monophosphate, most likely via binding to a membrane receptor of C. albicans.

FIG. 2.

Effect of GMAP on the budded-to-hyphal-form transition of C. albicans SC 5314 after 24 h. (A, C) Untreated controls. (B, D) Human GMAP (16-41) (4 μM)-treated wells. Images were taken from unstained preparations (A and B, 10-fold magnification) and from calcofluor white-stained cultures (C and D, 40-fold magnification).

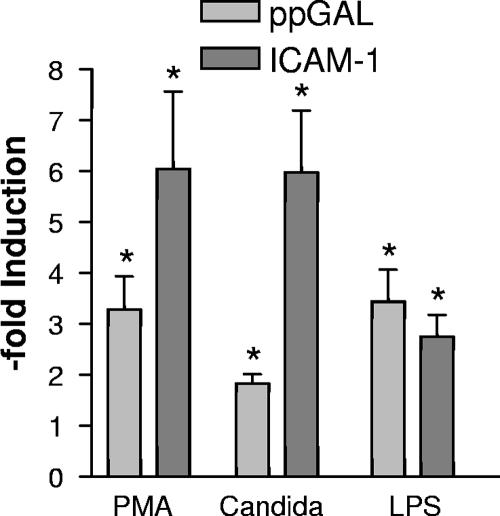

Since ppGAL mRNA was previously detected in human keratinocytes, the regulation of ppGAL upon treatment of human primary cultured keratinocytes (19) with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or living C. albicans was investigated. After isolation of the RNA (Tri-Reagent; Molecular Research Centre) and cDNA synthesis (Superscript II reverse transcriptase; Invitrogen), real-time PCR on the iCycler iQ real-time detection system using IQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) was carried out. Induction of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) was used as a positive control. Treatment of keratinocytes with LPS induced the ppGAL expression (3.4-fold). Cocultivation of primary human keratinocytes with C. albicans SC 5314 for 6 h induced ppGAL expression 1.8-fold (Fig. 3). Several properties of ppGAL are shared by other AMPs (1), suggesting that ppGAL is a natural AMP. These common properties include the following: a high level of expression in the epidermis (7), which, for example, parallels the expression of the antimicrobial neuropeptide α-MSH (14); sites of potential microbial entry in the skin, such as follicular structures and sweat glands, express ppGAL (7); and posttranslational processing of the precursor molecule is required for a functional peptide. Moreover, the ability of LPS to induce AMP gene expression has been demonstrated for several antimicrobial neuropeptides, including adrenomedullin, α-MSH, and proenkephalin (12, 13, 15).

FIG. 3.

Regulation of ppGAL expression in human keratinocytes. Primary cultured human keratinocytes were treated with phorbol-12-myristate (PMA; 50 nM), LPS (0.05 μg/ml), or live C. albicans SC 5134 (0.2 × 107 to 1 × 107 CFU/ml) for 6 h. Three independent experiments with quadruplicate values were carried out. Relative expression levels of galanin and ICAM-1 mRNA were calculated in relationship to the housekeeping gene hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase 1 (HPRT1). Primers used for real-time PCR were as follows: HPRT, (forward) TTC CTT GGT CAG GCA GTA TAA TC, (reverse) GGG CAT ATC CTA CAA CAA ACT TG; ppGAL, (forward) CTT CTC GCC TCC CTC CTC, (reverse) TGT CGC TGA ATG ACC TGT G; and ICAM-1, (forward) AAA CTT GCT GCC TAT TGG GT, (reverse) AGT AGA CAG CAG TGC CCA AG. *, significant difference compared to untreated control with P of <0.01 (Dunnet's multiple comparison test). Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean.

During the last decades, microbial resistance against antibiotics has emerged as a serious problem in the treatment of infection (4). In the search for new antimicrobial compounds, AMPs and their synthetic analogues seem to be a promising source (9). Synthetic derivatives of GMAP, chemically stable and resistant to enzymatic degradation, could form the basis for novel therapies. A potential advantage of using GMAP analogues as therapeutics for C. albicans infection is that, as an endogenous peptide, GMAP might be a nontoxic alternative to other commonly used agents. The mechanism of action of GMAP is different from those of common antifungal substances like fluconazole, which are cytotoxic to the pathogen either by inhibiting growth or direct killing. Inhibition of the budded-to-hyphal-form transition in combination with common cytotoxic drugs like fluconazole might lower the risk of pathogen dissemination and could have a preventive effect in high-risk patients. Furthermore, rising problems with resistance to antifungal drugs currently in use might be solved by using drugs with a different mode of action, such as GMAP, presented here.

Acknowledgments

The project was supported by a grant of the Paracelsus Medical University Salzburg (project no. 05/01/003), by the “Jubiläumsfonds” of the Austrian National Bank (project no. 11996), and by the Children's Cancer Foundation Salzburg.

We thank Roland Lang, Johann Bauer, and Sabine Schmidhuber for helpful discussions and Kamil Önder and Arnold Bito for technical advice and the generous gifts of strains.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 August 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bals, R. 2000. Epithelial antimicrobial peptides in host defense against infection. Respir. Res. 1:141-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brogden, K. A., J. M. Guthmiller, M. Salzet, and M. Zasloff. 2005. The nervous system and innate immunity: the neuropeptide connection. Nat. Immunol. 6:558-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cutuli, M., S. Cristiani, J. M. Lipton, and A. Catania. 2000. Antimicrobial effects of alpha-MSH peptides. J. Leukoc. Biol. 67:233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fish, D. N., and M. J. Ohlinger. 2006. Antimicrobial resistance: factors and outcomes. Crit. Care Clin. 22:291-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hageage, G. J., and B. J. Harrington. 1984. Use of calcofluor white in clinical mycology. Lab. Med. 15:109-112. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klepser, M. E. 2006. Candida resistance and its clinical relevance. Pharmacotherapy 26:68S-75S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kofler, B., A. Berger, R. Santic, K. Moritz, D. Almer, C. Tuechler, R. Lang, M. Emberger, A. Klausegger, W. Sperl, and J. W. Bauer. 2004. Expression of neuropeptide galanin and galanin receptors in human skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 122:1050-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumamoto, C. A., and M. D. Vinces. 2005. Contributions of hyphae and hypha-co-regulated genes to Candida albicans virulence. Cell Microbiol. 7:1546-1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marr, A. K., W. J. Gooderham, and R. E. Hancock. 2006. Antibacterial peptides for therapeutic use: obstacles and realistic outlook. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 6:468-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazarati, A. M. 2004. Galanin and galanin receptors in epilepsy. Neuropeptides 38:331-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odds, F. C. 1988. Candida and candidosis. A review and bibliography, 2nd ed. Bailliere-Tindall, London, United Kingdom.

- 12.Pepels, P. P., S. E. Bonga, and P. H. Balm. 2004. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) modulates corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) content and release in the brain of juvenile and adult tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus; Teleostei). J. Exp. Biol. 207:4479-4488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen, H., O. Behar, O. Abramsky, and H. Ovadia. 1989. Regulated expression of proenkephalin A in normal lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 143:3703-3707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schauer, E., F. Trautinger, A. Kock, A. Schwarz, R. Bhardwaj, M. Simon, J. C. Ansel, T. Schwarz, and T. A. Luger. 1994. Proopiomelanocortin-derived peptides are synthesized and released by human keratinocytes. J. Clin. Investig. 93:2258-2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugo, S., N. Minamino, H. Shoji, K. Kangawa, K. Kitamura, T. Eto, and H. Matsuo. 1995. Interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor and lipopolysaccharide additively stimulate production of adrenomedullin in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 207:25-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tatemoto, K., A. Rokaeus, H. Jornvall, T. J. McDonald, and V. Mutt. 1983. Galanin—a novel biologically active peptide from porcine intestine. FEBS Lett. 164:124-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vrontakis, M. E. 2002. Galanin: a biologically active peptide. Curr. Drug Targets CNS Neurol. Disord. 1:531-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walton, K. M., J. E. Chin, A. J. Duplantier, and R. J. Mather. 2006. Galanin function in the central nervous system. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Dev. 9:560-570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wittmann, M., R. Purwar, C. Hartmann, R. Gutzmer, and T. Werfel. 2005. Human keratinocytes respond to interleukin-18: implication for the course of chronic inflammatory skin diseases. J. Investig. Dermatol. 124:1225-1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]