Abstract

Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DHP) is an important new treatment for drug-resistant malaria, although pharmacokinetic studies on the combination are limited. In Papua, Indonesia, we assessed determinants of the therapeutic efficacy of DHP for uncomplicated malaria. Plasma piperaquine concentrations were measured on day 7 and day 28, and the cumulative risk of parasitological failure at day 42 was calculated using survival analysis. Of the 598 patients in the evaluable population 342 had infections with Plasmodium falciparum, 83 with Plasmodium vivax, and 173 with a mixture of both species. The unadjusted cumulative risks of recurrence were 7.0% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 4.6 to 9.4%) for P. falciparum and 8.9% (95% CI: 6.0 to 12%) for P. vivax. After correcting for reinfections the risk of recrudescence with P. falciparum was 1.1% (95% CI: 0.1 to 2.1%). The major determinant of parasitological failure was the plasma piperaquine concentration. A concentration below 30 ng/ml on day 7 was observed in 38% (21/56) of children less than 15 years old and 22% (31/140) of adults (P = 0.04), even though the overall dose (mg per kg of body weight) in children was 9% higher than that in adults (P < 0.001). Patients with piperaquine levels below 30 ng/ml were more likely to have a recurrence with P. falciparum (hazard ratio [HR] = 6.6 [95% CI: 1.9 to 23]; P = 0.003) or P. vivax (HR = 9.0 [95% CI: 2.3 to 35]; P = 0.001). The plasma concentration of piperaquine on day 7 was the major determinant of the therapeutic response to DHP. Lower plasma piperaquine concentrations and higher failure rates in children suggest that dose revision may be warranted in this age group.

The emergence of multidrug-resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum and, more recently, Plasmodium vivax poses a significant threat to the 40% of the global population at risk of malaria (13, 20). Following World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations, more than 60 countries are now moving towards deploying artemisinin combination therapies to improve antimalarial efficacy and minimize the selection of drug-resistant parasites. However, debate still continues as to the most effective combination and how these new treatments should be deployed and funded.

Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DHP) is a novel fixed-dose combination that is gaining a reputation as an important addition to the artemisinin combination therapy pharmacopoeia, particularly in areas with high levels of antimalarial drug resistance. The antimalarial activity of piperaquine has been recognized since the 1960s, although its widespread use in clinical practice has been restricted mainly to the People's Republic of China, where it replaced chloroquine in the national malaria control program in 1978 (4), and more recently Vietnam. In the last 5 years there has been an evolving body of evidence demonstrating excellent efficacy of DHP against multidrug-resistant strains of P. falciparum (1, 5, 7, 12, 15, 19, 22) and P. vivax (7, 15).

In Papua, Indonesia, where drug resistance has emerged in both P. falciparum and P. vivax (16), we have recently conducted two clinical drug studies with DHP. In both studies, the combination was found to be well tolerated and more effective at reducing recurrent malaria within 42 days than the comparator treatment arms (amodiaquine plus artesunate or artemether-lumefantrine) (7, 15). In this paper we have pooled these studies and incorporated measures of plasma piperaquine concentrations to assess the clinical and pharmacological parameters associated with the therapeutic response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study site.

The data used for this analysis were derived from two comparative studies conducted between April 2004 and December 2005, in two rural outpatient clinics, in the Timika district of southern Papua, Indonesia (7, 15). The annual incidence of malaria in the region is approximately 900 per 1,000 per year, divided 57:43 between P. falciparum and P. vivax infections (our unpublished data). Due to economic migration the ethnic origin of the local population is diverse, with highland Papuans, lowland Papuans, and non-Papuans resident in the region.

Study design.

These prospective open-label randomized comparative trials administered DHP for the treatment of infections with P. falciparum or P. vivax in children and adults with uncomplicated symptomatic malaria. The studies were based on the 2003 WHO in vivo antimalarial drug sensitivity protocol, modified to include mixed infections and any level of parasitemia. Patients were followed for 42 days using a standardized drug efficacy record form.

Patients.

Patients with slide-confirmed malaria (P. falciparum, P. vivax, or mixed infections) and fever or a history of fever during the 48 h preceding presentation to the outpatient clinic were eligible for enrolment. Pregnant or lactating women and children under 5 kg were excluded, as were patients with WHO danger signs or signs of severity, a parasitemia of >4% of infected red blood cells, or concomitant disease requiring hospital admission.

Study procedures.

After enrolment a standardized data sheet was completed recording demographic information, details of symptoms and their duration, and the history of previous antimalarial medication. Clinical examination findings were documented, including the axillary temperature, which was measured using a digital thermometer. Venous blood was taken for blood film, hematocrit, hemoglobin, and white cell count. Parasite counts were determined on Giemsa-stained thick films as the number of parasites per 200 white blood cells, and peripheral parasitemia was calculated assuming a white cell count of 7,300 μl−1. Hemoglobin level was measured using a battery-operated portable photometer (Hb201+; HemoCue, Angelholm, Sweden). Blood spots on filter paper (Whatman; BFC 1802) were also collected on day 0.

DHP (Artekin; Holley Pharmaceutical Co., People's Republic of China; containing 40 mg dihydroartemisinin and 320 mg piperaquine) was administered as a weight-per-dose regimen of 2.25 and 18 mg/kg of body weight per dose of dihydroartemisinin and piperaquine, respectively, rounded up to the nearest half tablet. Children under 9 kg were dosed with a suspension made by crushing one tablet in 5 ml of water (i.e., 8 mg DHA and 64 mg piperaquine per ml). Tablets for both studies came from the same batch, which was manufactured in February 2004, with an expiry date of February 2007. All doses were supervised and administered on admission and 24 and 48 h after admission. When drug administration was observed and vomiting occurred within 60 min, administration of the full dose was repeated. Primaquine (0.3 mg of base/kg of body weight for 14 days) was administered unsupervised to those individuals with P. vivax infection or mixed infection.

Patients were examined daily after enrolment until they became afebrile and aparasitemic. At each visit a blood smear was taken and a symptom questionnaire completed. Patients were then seen weekly for 6 weeks. At each clinic appointment a full physical examination was performed, the symptom questionnaire was completed, and blood was taken to check for parasite count and hemoglobin. Blood spots on filter paper were also collected on the day of failure. On days 7 and 28, 10 ml of blood was collected from patients who agreed to venipuncture. Samples were spun down within 2 h and stored at −80°C until processing. Plasma piperaquine concentrations were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography with UV detection (11); the lower level of quantification was 2.5 ng/ml, with an interassay coefficient of variation of 8.4% at 20 ng/ml.

Statistical analysis.

Data were double entered and validated using EpiData 3.02 software (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark), and analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows (version 15; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis method, or Spearman's rank correlation was used for nonparametric comparisons, and Student's t test or one-way analysis of variance was used for parametric comparisons. Proportions were examined using χ2 with Yates' correction or Fisher's exact test. The influence of the date of enrolment on treatment efficacy was investigated by categorizing patients according to four 4-month periods over the 16-month period of the study.

Efficacy end points were assessed using survival analysis. All patients meeting the enrolment criteria were included in the evaluable population. Results for anyone failing to complete follow-up were censored on the last day of follow-up and were regarded as not representing a treatment failure. In patients with P. falciparum alone or mixed infections in both the initial and recurrent parasitemia, reinfections and recrudescent infections were determined by PCR according to polymorphisms in MSP-1, MSP-2, and GLURP as described previously (3). Failure rates were defined by the cumulative incidence at day 42 calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The risks of treatment failure were compared by the Mantel-Haenszel log rank test, and the hazard ratio (HR) was presented. In the multivariable analysis any variables found to be associated significantly with the dependent variable in univariate analysis were entered into a Cox regression model and the model was constructed using all factors.

Since the relationship of the therapeutic response and plasma concentrations of antimalarial drugs is nonlinear (23), plasma piperaquine concentrations on day 7 were dichotomized using the receiver operator curve, and the optimal cutoff was defined as the maximum value of Youden's index (sensitivity plus specificity minus 1). The terminal elimination half-life was derived from the elimination rate constant, calculated from plasma piperaquine concentrations on day 7 and day 28 by log-linear interpolation.

Ethics.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the National Institute of Health Research and Development, Indonesian Ministry of Health (Jakarta, Indonesia), the ethics committee of the Menzies School of Health Research (Darwin, Australia), and the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee (United Kingdom). Written informed consent was obtained from adult patients and parents of enrolled children. The trials were registered with the clinical trial website (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct) as NCT 00157833 and NCT 00157885.

RESULTS

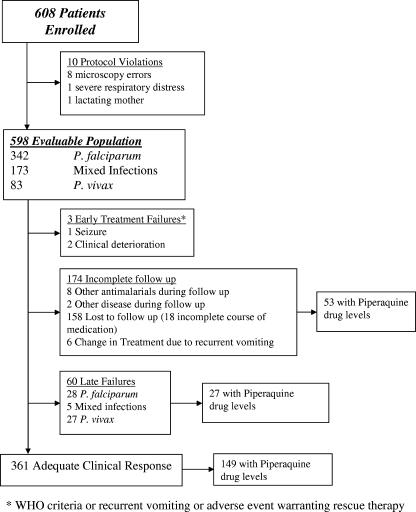

Between July 2004 and November 2005, 608 patients with uncomplicated malaria were enrolled in two comparative drug studies and treated with DHP. In total, 10 protocol violations were identified within 24 h; the patients involved were offered alternative treatment and excluded from further analysis (Fig. 1). Of the remaining 598 patients, 342 (57%) had pure P. falciparum infection, 83 (14%) had P. vivax infection, and 173 (29%) had both species present. Baseline characteristics are given in Table 1. Follow-up to day 42 or day of failure was achieved in 71% (424/598) of patients. Six patients (1.0%) were unable to tolerate their medication due to recurrent vomiting and required rescue treatment. The early therapeutic response in the remaining patients was rapid and within 48 h 99% of patients were aparasitemic (563/569) and afebrile (523/526).

FIG. 1.

Study profile.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics at baseline

| Parameter | Value for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Evaluable population | Subset of patients with plasma piperaquine measurementsa | |

| Total no. of patients | 598 | 229 |

| P. falciparum infection at enrolment | ||

| No. (%) of patients | 342 (57) | 136 (59) |

| Geometric mean parasitemia (organisms/μl−1) (95% CI) | 3,848 (3,198-4,632) | 3,631 (2,758-4,782) |

| No. (%) of patients with parasitemia >1,000 organisms μl−1 | 275 (80) | 111 (82) |

| P. vivax infection at enrolment | ||

| No. of patients (%) | 173 (29) | 51 (22) |

| Geometric mean parasitemia (organisms μl−1) (95% CI) | 1,988 (1,550-2,550) | 1,794 (1,168-2,757) |

| No. (%) of patients with parasitemia >400 organisms μl−1 | 136 (79) | 42 (82) |

| Mixed infections at enrolment | ||

| No. (%) of patients | 83 (14) | 42 (18) |

| Geometric mean parasitemia (organisms μl−1) (95% CI) | 4,717 (3,399-6,547) | 5,175 (3,269-8,193) |

| No. (%) of patients with parasitemia >400 organisms μl−1 | 79 (95) | 40 (95) |

| No. (%) of males | 349 (58) | 145 (63) |

| Median wt (kg) (range) | 46 (7-85) | 52 (11-80)* |

| Median age (yr) (range) | 16 (1-60) | 20 (3-60)* |

| No. (%) of patients aged | ||

| <5 yr | 96 (16) | 4 (1.7) |

| 5-14 yr | 178 (30) | 61 (27) |

| >14 yr | 324 (54) | 164 (72) |

| No. (%) of patients with temp >37.5°C | 136 (23) | 53 (23) |

| No. (%) of patients with history of malaria in previous mo | 141 (24) | 45 (20) |

| Mean hemoglobin level (g/dl) (SD) | 10.2 (2.5) | 10.9 (2.4)* |

| No. (%) of patients with splenomegaly | 402 (67) | 139 (61) |

*, significant difference (P < 0.001) between subset of patients with plasma piperaquine measurement and the whole cohort.

Treatment failure.

Early clinical deterioration with danger signs was observed within 24 h in three patients, who were transferred to hospital and treated with intravenous quinine. By day 42, a further 60 patients had had a recurrent parasitemia (Fig. 1), with an overall cumulative risk of treatment failure of 15% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 12 to 19%). In total, 53% (30/57) of patients with recurrences were symptomatic, 12% (7/57) had documented fever, and 23% (11/47) were anemic (hemoglobin < 10 g/dl). There were no significant differences in these proportions between the species at the time of recurrence. By day 42 the cumulative risks of recurrence were 7.0% (95% CI: 4.7 to 9.35%) for P. falciparum and 8.9% (95% CI: 6.0 to 12%) for P. vivax. After PCR correction the cumulative risk of recrudescent P. falciparum fell to 1.1% (95% CI: 0.1 to 2.1%). In those patients failing treatment the median time to recurrence with P. falciparum was 36 days (range, 22 to 45 days) compared to 43 days (range, 22 to 45 days) for patients failing with pure P. vivax (P = 0.04).

Clinical risk factors for treatment failure.

Four univariate factors on admission were associated with treatment failure: the species of the initial infection, being an indigenous Papuan (HR = 4.7; 95% CI: 1.7 to 13; P = 0.003), having diarrhea at presentation (HR = 1.9; 95% CI: 1.1 to 3.1; P = 0.014), and prior treatment for malaria within the preceding month (HR = 1.7; 95% CI: 1.0 to 2.9; P = 0.039). The overall cumulative risk of failure was 10.1% (95% CI: 6.2 to 14.0%) in patients presenting initially with P. falciparum infections, compared to 19.4% (95% CI: 12 to 26.8%) in patients infected with P. vivax and 27.3% (95% CI: 16.2 to 38.5%) in those with mixed infections; the overall P value was <0.001. In a multivariable model including all patients enrolled, after stratifying by the initial species of infection, the only significant risk factor for treatment failure was Papuan ethnicity (adjusted hazards ratio [AHR] = 5.0; 95% CI: 1.8 to 14; P = 0.002). The risk of recurrent parasitemia with P. vivax was 7.3% (95% CI: 4.4 to 10.2%) in children under 5 years old, compared to 17.0% (95% CI: 7.6 to 26.4%) in older children and adults (HR = 2.5; 95% CI: 1.2 to 5.1; P = 0.012). There was no significant difference in the cumulative risk of reappearance for P. falciparum between age groups. The risk of failure did not differ with sex, vomiting of medication, or baseline parasitemia. And there was not a significant difference or discernible trend in either the cumulative risk of treatment failure at day 42 or the speed of parasite clearance between patients recruited at the start and end of the study period.

Dose of DHP.

The mean total dose of dihydroartemisinin administered was 6.75 mg/kg (95% CI: 6.68 to 6.82 mg/kg; range: 4.62 to 9.23 mg/kg) and that of piperaquine was 54.0 mg/kg (95% CI: 53.4 to 54.6 mg/kg; range: 36.9 to 73.9 mg/kg) (Fig. 2a). Neither the dose of dihydroartemisinin nor that of piperaquine correlated with the speed of clearance of peripheral parasitemia. The mean dose of piperaquine administered to children under 5 years old was 55.4 mg/kg (95% CI: 52.8 to 58.1 mg/kg) compared to 56.9 mg/kg (95% CI: 55.9 to 57.9 mg/kg) in children aged 5 to 15 years and 51.9 mg/kg (95% CI: 51.6 to 52.2 mg/kg) in adults (overall P < 0.001). The spread of dosing was greatest in children under 5 years old (standard deviation [SD] = 12.7 mg/kg) compared to children aged 5 to 15 years (SD = 6.8 mg/kg) and adults (SD = 2.8 mg/kg) (Fig. 2b). Using Youden's index the best cutoff for the total piperaquine dose predicting treatment failure was 48 mg/kg, with 46% (42/92) of children under 5 years of age receiving a dose of piperaquine below this level compared to 8.1% (14/173) of children aged 5 to 14 years and 12.9% (39/263) of adults (overall P < 0.001). The overall risk of failure was 31% (95% CI: 20 to 42%) in patients administered less than 48 mg/kg compared to 9.0% (95% CI: 6.1 to 11.9%) in those receiving higher doses (HR = 3.1; 95% CI: 1.9 to 5.2; P < 0.001).

FIG. 2.

Scatter plots of weight (a) and age (b) with the mg/kg dose of piperaquine administered.

Piperaquine levels.

Plasma piperaquine levels were available for 33% (196/598) of patients on day 7 and 18% (109/598) on day 28 (Fig. 1). Overall, 51% (164/324) of adults agreed to venipuncture compared to 34% (61/178) of parents of children aged 5 to 14 years and only 4% (4/96) of parents of children under 5 years of age (P < 0.001). Compared to those refusing venipuncture, patients with available plasma concentrations did not differ in parasite density, ethnic group, diarrhea on admission, or risk of recurrence by day 42 (Table 1).

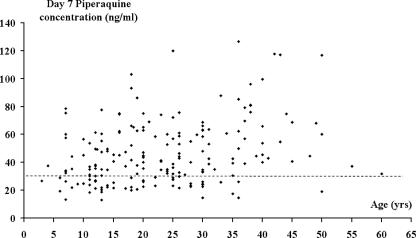

The mean plasma piperaquine concentration was 46.6 ng/ml (95% CI: 43.3 to 49.8 ng/ml) on day 7 and 16.8 ng/ml (95% CI: 15.1 to 18.6 ng/ml) on day 28. Age and the plasma concentration of piperaquine on day 7 were positively correlated (rs = 0.289; P < 0.001) (Fig. 3), with day 7 concentrations 26% lower in children aged less than 15 years (mean = 37.1 ng/ml; 95% CI: 32.8 to 41.3 ng/ml) than in adults (mean = 50.4 ng/ml; 95% CI: 46.4 to 54.5 ng/ml; P < 0.001).

FIG. 3.

Scatter plot of age and the plasma piperaquine concentration on day 7 (rs = 0.289; P < 0.001). The dashed line represents the 30-ng/ml cutoff, found to be the best predictor of treatment failure.

In total 73 patients had levels on both day 7 and day 28, 4 of whom had undetectable levels on the second measurement. In those with detectable levels on both days the mean elimination half-life was estimated as 16.5 days (95% CI: 11.5 to 21.5 days), with no differences between adults (n = 52) and children (n = 17).

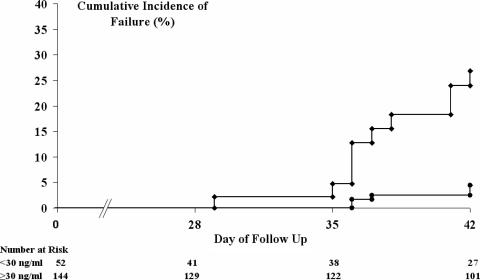

In patients with recurrent parasitemia, the mean plasma piperaquine level on day 7 was 28.4 ng/ml (95% CI: 22.1 to 34.8 ng/ml), compared to 48.7 ng/ml (95% CI: 45.3 to 52.1 ng/ml) in those treated successfully (P < 0.001). The best cutoff for the day 7 piperaquine concentration predicting any treatment failure was 30 ng/ml, with levels below this observed in 38% (21/56) of children and 22% (31/140) of adults (relative risk [RR] = 1.69; 95% CI: 1.1 to 2.7; P = 0.04). In the 196 patients with available day 7 piperaquine concentrations, the overall the risk of failure was 36% (95% CI: 20 to 52%) in patients with concentrations below this level compared to 6.8% (95% CI: 1.9 to 12%) in those above (HR = 6.1; 95% CI: 2.4 to 15.5; P < 0.001) (Fig. 4). The risks of failure stratified by species are given in Table 2.

FIG. 4.

Cumulative risk of patients failing with any parasitemia. Circles, day 7 piperaquine concentration of ≥30 ng/ml; diamonds, day 7 piperaquine concentration of <30 ng/ml. The overall P value for the difference between treatment groups at day 42 was 0.001.

TABLE 2.

Day 42 cumulative risk of failure following DHP in 198 patients with available plasma piperaquine concentrations on day 7

| Parasitological failure | Day 7 piperaquine concn < 30 ng/ml

|

Day 7 piperaquine concn ≥ 30 ng/ml

|

HRa (95% CI); P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Risk (%) (95% CI) | n | Risk (%) (95% CI) | ||

| Any species after initial infection with any species | 52 | 36 (20-52) | 144 | 6.8 (1.9-12) | 6.1 (2.4-15); 0.001 |

| P. falciparum | |||||

| After initial infection with any species | 52 | 23 (9.6-37) | 144 | 3.8 (0.1-7.5) | 6.6 (1.9-23); 0.003 |

| True recrudescence of P. falciparumb | 44 | 6.1 (0-14.5) | 106 | 0 | 0.02c |

| After reinfection with P. falciparum | 52 | 18 (4.7-31) | 144 | 3.8 (0.1-7.5) | 4.9 (1.3-18); 0.017 |

| P. vivax | |||||

| After initial infection with any species | 52 | 26 (10-42) | 144 | 3.1 (0-6.6) | 9.0 (2.3-35); 0.001 |

| After initial infection with P. vivax (alone or mixed) | 23 | 50 (21-79) | 60 | 4.8 (0-11) | 11.6 (2.3-57); 0.003 |

The HR was calculated using a Cox regression model after stratifying for the initial species of infection.

After correcting by PCR genotyping, in patients initially infected with P. falciparum (alone or mixed).

Value for P.

Piperaquine concentrations below 30 ng/ml on day 7 were significantly more likely to occur in patients who were Papuan (RR = 5.2; 95% CI: 1.7 to 15.8; P < 0.001), who were less than 15 years old (RR = 1.7; 95% CI: 1.1 to 2.7; P = 0.04), or who presented with diarrhea (RR = 1.8; 95% CI: 1.2 to 2.9; P = 0.02) or anemia (RR = 2.3; 95% CI: 1.5 to 3.6; P < 0.001). In a multivariable model including all these factors and stratifying by the initial species, the only significant risk factor predicting recurrent parasitemia was a day 7 concentration below 30 ng/ml (AHR = 5.1; 95% CI: 1.6 to 16; P < 0.001). The overall population attributable risk associated with low piperaquine concentration at day 7 was 21%.

DISCUSSION

The results of our studies demonstrate that DHP is well tolerated and a highly effective treatment of both multidrug-resistant P. falciparum and P. vivax in Papua, Indonesia. Of the 99% of patients who completed their course of treatment, the cumulative risk at day 42 of true recrudescence with P. falciparum was 1.1%, with a corresponding risk of recurrence with P. vivax of 8.9%. However, despite these excellent results we identified certain groups of patients at significantly greater risk for recurrence of malaria, in whom the risk of treatment failure rose to as high as 50%.

Artemisinin combination therapies achieve their antimalarial effect through an initial rapid reduction in parasite biomass, attributable to the short-acting but highly potent dihydroartemisinin, with the subsequent removal of the remaining parasites by the intrinsically less active but more slowly eliminated piperaquine. Overall cure rates depend upon there being sufficient partner drug to remove the residual parasite biomass left by the artemisinin derivative. Our venous sampling was pragmatic, but sparse and therefore did not allow us to define the full pharmacokinetic profile of piperaquine. However, as with other long-acting antimalarial drugs, the day 7 level may provide a useful surrogate marker of the area under the curve and time above the MIC (6, 18), both crucial determinants of the in vivo response to antimalarial drugs (23). Studies with both artemether-lumefantrine and mefloquine plus artesunate have shown that the day 7 concentrations of the long-acting partner drug are the primary predictors of subsequent treatment outcome (14, 18).

In the present study we show that two pharmacological parameters, the day 7 piperaquine concentration and the total mg/kg dose of piperaquine administered, were important determinants of treatment outcome. Children were more vulnerable to both inadequate dosing and low plasma drug concentrations. Even though the dose of DHP was administered on the basis of weight, this was carried out according to weight groups to the nearest half tablet, with a suspension used only for those weighing less than 9 kg. This strategy amounted to increments in dose of 160 mg of piperaquine and 20 mg of dihydroartemisinin, and the effects of such an increase resulted in a wide range in the mg/kg dose administered, particularly in young children (Fig. 2). Although this variability would be ameliorated by the wider use of pediatric syrup or suspensions, such formulations are not yet available for many antimalarials. Furthermore, in practice most rural clinics administer drugs according to age groups, with inevitable inaccuracies in dosing (21). These findings highlight the need for practical attention to, and reporting of, dosing practices, particularly in young children.

We were not able to define the relevance of inadequate dosing on plasma levels of piperaquine, since parents of only four children under 5 years of age agreed for their children to be bled. However, in older children the overall mean dose administered to children was actually 9% higher than that given to adults and yet the day 7 plasma piperaquine concentrations were 26% lower. This discrepancy could have arisen from higher clearance rates, which have been noted in children (9). Our estimate of the terminal elimination half-life of piperaquine was 396 h, similar to that observed previously (9), although no difference in half-life between adults and children aged 5 to 14 years was noted. An alternative explanation is that the low plasma concentrations of piperaquine are a consequence of inadequate drug absorption, to which children are particularly vulnerable, especially those presenting with diarrhea. Since coadministration with a high-fat meal increases the oral bioavailability of piperaquine by 120% (17), advocating that medication be taken with a glass of milk or a biscuit, as is currently recommended for artemether-lumefantrine, may help to improve piperaquine absorption.

Young children were 2.5-fold more likely to suffer a recurrent parasitemia with P. vivax than older children or adults. Although this difference was not apparent for P. falciparum infections, this may reflect the low failure rates with P. falciparum and the fact that only 16% of the patients recruited in our study were under 5 years of age. Hence our study may simply have been underpowered in this respect. The clinical implications of this may be more apparent in areas of high transmission, where nearly all of the patients seeking medical treatment are young children. Indeed cure rates for Rwanda suggest that the efficacy of DHP in this age group may be significantly lower than that observed in Asia (10).

Most formal pharmacokinetic studies of antimalarial drugs are conducted either with healthy volunteers or adults. Since pharmacokinetic profiles in children and pregnant women can be markedly different, the derivation of appropriate dosing recommendations necessitates that prospectively designed pharmacokinetic studies be conducted with the target population rather than extrapolated from studies with adults. Recently this has been highlighted in a study of the use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine which suggests that this widely deployed drug has systematically been underdosed in children for over 20 years (2). Our preliminary findings raise the possibility that a similar discrepancy may arise with DHP and that the currently recommended dose in children (2.25 mg/kg dihydroartemisinin and 18 mg/kg piperaquine) is suboptimal and accounts for approximately 20% of treatment failures. However, formal pharmacokinetic studies are needed to confirm our findings and define the relationship between the day 7 piperaquine concentration and the complete pharmacokinetic profile.

Concerns have been raised over the stability of the dihydroartemisinin component in the fixed-dose combination (8). Reassuringly, over the 16-month duration of the study, despite using the same batch of drugs there was no discernible change or temporal trend in the early or late treatment responses. Further studies are needed to confirm the clinical relevance of tablet stability, but in practice the DHP appears to retain excellent efficacy in a tropical rural setting.

In summary DHP is a well-tolerated and effective antimalarial that results in excellent treatment outcome both in curing initial infections with multidrug-resistant P. falciparum and P. vivax and preventing reinfection and relapse. Using current recommendations, health workers should aim to give a total of at least 48 mg/kg of piperaquine. Further studies are warranted to define the pharmacokinetic profile of piperaquine in children and determine whether increased dosing can optimize the efficacy of this important antimalarial combination regimen.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Lembaga Pengembangan Masyarakat Amungme Kamoro and the staff of PT Freeport Indonesia Public Health & Malaria Control Department and International SOS for support and technical assistance. We thank Mauritz Okeseray, Rosmini, Buhari, Alan Brockman, Kim Piera, Ferryanto Chalfein, and Budi Prasetyorini for their support and technical assistance. We are also grateful to Morrison Bethea and the executive staff of PT Freeport Indonesia for their support. We thank Nick White, Liz Ashley, François Nosten, and Julie Simpson for critical review of the manuscript and statistical methods.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust-NHRMC (Wellcome Trust ICRG GR071614MA-NHMRC ICRG ID 283321). N.M.A. is supported by an NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship. R.N.P. is funded by a Wellcome Trust Career Development Award, affiliated to the Wellcome Trust, Mahidol University, Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Programme (074637).

We declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 September 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashley, E. A., S. Krudsood, L. Phaiphun, S. Srivilairit, R. McGready, W. Leowattana, R. Hutagalung, P. Wilairatana, A. Brockman, S. Looareesuwan, F. Nosten, and N. J. White. 2004. Randomized, controlled dose-optimization studies of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for the treatment of uncomplicated multidrug-resistant falciparum malaria in Thailand. J. Infect. Dis. 190:1773-1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes, K. I., F. Little, P. J. Smith, A. Evans, W. M. Watkins, and N. J. White. 2006. Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine pharmacokinetics in malaria: pediatric dosing implications. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 80:582-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brockman, A., R. E. Paul, T. J. Anderson, I. Hackford, L. Phaiphun, S. Looareesuwan, F. Nosten, and K. P. Day. 1999. Application of genetic markers to the identification of recrudescent Plasmodium falciparum infections on the northwestern border of Thailand. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 60:14-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis, T. M., T. Y. Hung, I. K. Sim, H. A. Karunajeewa, and K. F. Ilett. 2005. Piperaquine: a resurgent antimalarial drug. Drugs 65:75-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denis, M. B., T. M. Davis, S. Hewitt, S. Incardona, K. Nimol, T. Fandeur, Y. Poravuth, C. Lim, and D. Socheat. 2002. Efficacy and safety of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (Artekin) in Cambodian children and adults with uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:1469-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ezzet, F., M. van Vugt, F. Nosten, S. Looareesuwan, and N. J. White. 2000. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of lumefantrine (benflumetol) in acute falciparum malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:697-704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasugian, A. R., H. L. Purba, E. Kenangalem, R. M. Wuwung, E. P. Ebsworth, R. Maristela, P. M. Penttinen, F. Laihad, N. M. Anstey, E. Tjitra, and R. N. Price. 2007. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine versus artesunate-amodiaquine: superior efficacy and posttreatment prophylaxis against multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax malaria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:1067-1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haynes, R. K., H. W. Chan, C. M. Lung, N. C. Ng, H. N. Wong, L. Y. Shek, I. D. Williams, A. Cartwright, and M. F. Gomes. 2007. Artesunate and dihydroartemisinin (DHA): unusual decomposition products formed under mild conditions and comments on the fitness of DHA as an antimalarial drug. ChemMedChem 2:1448-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hung, T. Y., T. M. Davis, K. F. Ilett, H. Karunajeewa, S. Hewitt, M. B. Denis, C. Lim, and D. Socheat. 2004. Population pharmacokinetics of piperaquine in adults and children with uncomplicated falciparum or vivax malaria. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 57:253-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karema, C., C. I. Fanello, C. Van Overmeir, J. P. Van Geertruyden, W. van Doren, D. Ngamije, and U. D'Alessandro. 2006. Safety and efficacy of dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine (Artekin) for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Rwandan children. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 100:1105-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindegardh, N., N. J. White, and N. P. Day. 2005. High throughput assay for the determination of piperaquine in plasma. J. Pharm. Biomed Anal. 39:601-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayxay, M., V. Thongpraseuth, M. Khanthavong, N. Lindegardh, M. Barends, S. Keola, T. Pongvongsa, S. Phompida, R. Phetsouvanh, K. Stepniewska, N. J. White, and P. N. Newton. 2006. An open, randomized comparison of artesunate plus mefloquine vs. dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in the Lao People's Democratic Republic (Laos). Trop. Med. Int. Health 11:1157-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price, R. N., E. Tjitra, C. A. Guerra, S. Yeung, N. J. White, and N. M. Anstey. Vivax malaria: neglected and not benign. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Price, R. N., A. C. Uhlemann, M. Vugt, A. Brockman, R. Hutagalung, S. Nair, D. Nash, P. Singhasivanon, T. J. Anderson, S. Krishna, N. J. White, and F. Nosten. 2006. Molecular and pharmacological determinants of the therapeutic response to artemether-lumefantrine in multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42:1570-1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ratcliff, A., H. Siswantoro, E. Kenangalem, R. Maristela, R. M. Wuwung, F. Laihad, E. P. Ebsworth, N. M. Anstey, E. Tjitra, and R. N. Price. 2007. Two fixed-dose artemisinin combinations for drug-resistant falciparum and vivax malaria in Papua, Indonesia: an open-label randomised comparison. Lancet 369:757-765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ratcliff, A., H. Siswantoro, E. Kenangalem, M. Wuwung, A. Brockman, M. D. Edstein, F. Laihad, E. P. Ebsworth, N. M. Anstey, E. Tjitra, and R. N. Price. 2007. Therapeutic response of multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in southern Papua, Indonesia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 101:351-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sim, I. K., T. M. Davis, and K. F. Ilett. 2005. Effects of a high-fat meal on the relative oral bioavailability of piperaquine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2407-2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simpson, J. A., E. R. Watkins, R. N. Price, L. Aarons, D. E. Kyle, and N. J. White. 2000. Mefloquine pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic models: implications for dosing and resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3414-3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smithuis, F., M. K. Kyaw, O. Phe, K. Z. Aye, L. Htet, M. Barends, N. Lindegardh, T. Singtoroj, E. Ashley, S. Lwin, K. Stepniewska, and N. J. White. 2006. Efficacy and effectiveness of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine versus artesunate-mefloquine in falciparum malaria: an open-label randomised comparison. Lancet 367:2075-2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snow, R. W., C. A. Guerra, A. M. Noor, H. Y. Myint, and S. I. Hay. 2005. The global distribution of clinical episodes of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature 434:214-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terlouw, D. J., J. M. Courval, M. S. Kolczak, O. S. Rosenberg, A. J. Oloo, P. A. Kager, A. A. Lal, B. L. Nahlen, and F. O. ter Kuile. 2003. Treatment history and treatment dose are important determinants of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine efficacy in children with uncomplicated malaria in western Kenya. J. Infect. Dis. 187:467-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tran, T. H., C. Dolecek, P. M. Pham, T. D. Nguyen, T. T. Nguyen, H. T. Le, T. H. Dong, T. T. Tran, K. Stepniewska, N. J. White, and J. Farrar. 2004. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine against multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Vietnam: randomised clinical trial. Lancet 363:18-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White, N. J. 2002. The assessment of antimalarial drug efficacy. Trends Parasitol. 18:458-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]