Abstract

The aim of the present study was to provide a mechanistic insight into how phosphatase activity influences calcium-activated chloride channels in rabbit pulmonary artery myocytes. Calcium-dependent Cl− currents (IClCa) were evoked by pipette solutions containing concentrations between 20 and 1000 nM Ca2+ and the calcium and voltage dependence was determined. Under control conditions with pipette solutions containing ATP and 500 nM Ca2+, IClCa was evoked immediately upon membrane rupture but then exhibited marked rundown to ∼20% of initial values. In contrast, when phosphorylation was prohibited by using pipette solutions containing adenosine 5′-(β,γ-imido)-triphosphate (AMP-PNP) or with ATP omitted, the rundown was severely impaired, and after 20 min dialysis, IClCa was ∼100% of initial levels. IClCa recorded with AMP-PNP–containing pipette solutions were significantly larger than control currents and had faster kinetics at positive potentials and slower deactivation kinetics at negative potentials. The marked increase in IClCa was due to a negative shift in the voltage dependence of activation and not due to an increase in the apparent binding affinity for Ca2+. Mathematical simulations were carried out based on gating schemes involving voltage-independent binding of three Ca2+, each binding step resulting in channel opening at fixed calcium but progressively greater “on” rates, and voltage-dependent closing steps (“off” rates). Our model reproduced well the Ca2+ and voltage dependence of IClCa as well as its kinetic properties. The impact of global phosphorylation could be well mimicked by alterations in the magnitude, voltage dependence, and state of the gating variable of the channel closure rates. These data reveal that the phosphorylation status of the Ca2+-activated Cl− channel complex influences current generation dramatically through one or more critical voltage-dependent steps.

INTRODUCTION

In smooth muscle cells, Cl− ions are actively accumulated by three major uptake mechanisms: the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter, the Cl:HCO3 exchanger, and a poorly characterized “pump III” (Chipperfield and Harper, 2000). The product of these transporter systems is an intracellular [Cl−] lying between 30 and 80 mM (Chipperfield and Harper, 2000). This results in an electrochemical gradient favoring Cl− efflux at the measured resting membrane potential of ∼−40 to −60 mV. As a consequence, activation of Cl− channels is an important mechanism to increase smooth muscle cell excitability by depolarizing the cell membrane potential (Large and Wang, 1996; Leblanc et al., 2005).

The most extensively recorded Cl− channel current in smooth muscle cells is evoked by a rise in intracellular [Ca2+], the so called calcium-activated chloride current (IClCa). There have been numerous studies reporting the activation of IClCa by various agents and manipulations in smooth muscle cells (Large and Wang, 1996; Leblanc et al., 2005). However, the molecular identity remains elusive and little is known about how the channel is gated by a rise in [Ca2+] or how intracellular regulators modify this process. Recent studies revealed that the activity of Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels (ClCa) is influenced by Ca2+-dependent enzymes. For example, blockers of the Ca2+-calmodulin–dependent kinase CaMKII prolong the duration of IClCa in myocytes isolated from trachea (Wang and Kotlikoff, 1997) and enhance IClCa in pulmonary and coronary artery smooth muscle cells (Greenwood et al., 2001). The suppressive role of CaMKII in pulmonary artery myocytes was substantiated by the use of constitutively active CaMKII (Greenwood et al., 2001). Subsequent experiments established that a counter mechanism of regulation is provided by the Ca2+-dependent serine/threonine phosphatase calcineurin or PP2B (Ledoux et al., 2003; Greenwood et al., 2004). Moreover, in pulmonary artery myocytes, the positive regulation of IClCa depends on the isoform of the catalytic subunit (Greenwood et al., 2004). Consequently, while it is axiomatic that generation of IClCa relies upon an increase in [Ca2+]i, dephosphorylation of the channel complex also determines IClCa activity.

The aim of the present study was to undertake a rigorous examination of the activation of IClCa by intracellular [Ca2+] under conditions where phosphorylation is supported or minimized. To obviate any reliance upon Ca2+ influx or Ca2+ release mechanism, IClCa was activated by pipette solutions containing free [Ca2+]i set at known concentrations. This technique has been employed to characterize similar conductances in lacrimal cells (Evans and Marty, 1986), parotid acinar cells (Arreola et al., 1996), endothelial cells (Nilius et al., 1997), and Xenopus oocytes (Kuruma and Hartzell, 2000). Recently we have used this technique to study IClCa in smooth muscle cells isolated from hepatic portal vein, pulmonary artery, and coronary artery (e.g., Greenwood et al., 2001; Ledoux et al., 2003; Greenwood et al., 2004; Ledoux et al., 2005). With pipette solutions containing free Ca2+ higher than the threshold for activation, IClCa was sustained and exhibited distinctive voltage-dependent kinetics following membrane depolarization. In the present study, IClCa was recorded with pipette solutions containing different [Ca2+] ranging from 20 to 1000 nM and either 3 mM ATP or 3 mM adenosine 5′-(β,γ-imido)-triphosphate (AMP-PNP) to assess the mechanistic effect of dephosphorylation on the Cl− conductance. As the terminal phosphate of AMP-PNP is resistant to hydrolysis (Yount, 1975), this compound prohibits substrate phosphorylation and has been used in studies to explore the role of phosphorylation (e.g., regulation of CFTR; Gadsby and Nairn, 1999). Consequently, the action of endogenous phosphatases was accentuated. These experiments revealed calcium and voltage dependency of IClCa activation. Moreover, the results provide a novel insight into how the gating of the Ca2+-activated Cl− channel is influenced by dephosphorylation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of Freshly Dissociated Pulmonary Artery Myocytes

A similar technique to that previously used by our group (Greenwood et al., 2001, 2004) was used to isolate smooth muscle cells. In brief, cells were prepared from the main and secondary pulmonary arterial branches dissected from New Zealand white rabbits (2–3 kg) killed by anesthetic overdose in accordance with British and American regulations. After dissection and removal of connective tissue, the pulmonary arteries were cut into small strips and incubated overnight (∼16 h) at 4°C in a low Ca2+ physiological salt solution (PSS) containing either 10 or 50 μM CaCl2 and 1 mg ml−1 papain, 0.15 mg ml−1 dithiothreitol, and 2 mg ml−1 BSA. The next morning, the tissue strips were rinsed three times in low Ca2+ PSS and incubated in the same solution for 10 min at 37°C. Cells were released by gentle agitation with a wide bore Pasteur pipette. Cells were stored at 4°C and used within 10 h after dispersion.

Patch Clamp Methods

Ca2+-activated Cl− currents were elicited in conventional whole-cell path clamp mode by pipette solutions containing 10 mM BAPTA and free [Ca2+] set to values ranging from 20 to 1000 nM by the addition of 0.84–8.7 mM CaCl2 as determined by the calcium chelator program EQCAL (Biosoft). Free [Ca2+] was verified independently using a Ca2+-sensitive electrode (Thermo Orion, model 93–20) using calibrated solutions (CALBUF-2; World Precision Instruments Inc.). These [Ca2+] constitute a dynamic range experienced by smooth muscle cells physiologically (e.g., ZhuGe et al., 2002). It is worth stressing that contraction of the myocyte was observed with pipette solutions containing Ca2+ >100 nM as Ca2+ flooded into the cell following membrane rupture. No attempt was made to block this contraction (e.g., by inhibition of myosin light chain kinase) as this would introduce another variable into the recording conditions. Contamination of IClCa from other types of current was minimized by the use of CsCl and TEA in the pipette solution, and TEA in the external solution. Control pipette solutions contained 3 mM ATP, whereas the test internal solutions contained 3 mM AMP-PNP. On any given experimental day, pipette solutions containing ATP were rigorously alternated with one containing AMP-PNP. However only one Ca2+ concentration could be practically tested on the same day due to the low success rate of maintaining a stable recording for the entire 20 min of cell dialysis. Consequently, data for each group were collected in cells from at least two animals. In all cases, the cell capacitance was similar across the whole study. Mean ± SEM cell capacitances measured from cells dialyzed with ATP for the following pipette Ca2+ concentrations were as follows: 20 nM, 21.3 ± 6.4 pF (n = 5); 100 nM, 18.8 ± 3.0 pF (n = 3); 250 nM, 21.1 ± 1.6 pF (n = 13); 500 nM, 18.2 ± 1.3 pF (n = 11); 750 nM, 16.4 ± 1.7 pF (n = 8); 1000 nM, 13.1 ± 1.4 pF (n = 6). Conversely, for the AMP-PNP group of data, mean ± SEM cell capacitances for the same pipette Ca2+ concentrations were as follows: 20 nM, 21.3 ± 2.4 pF (n = 5); 100 nM, 19.3 ± 1.9 pF (n = 8); 250 nM, 22.3 ± 3.9 pF (n = 7); 500 nM, 18.5 ± 1.1 pF (n = 15); 750 nM, 18.1 ± 1.5 pF (n = 13); 1000 nM, 19.1.1 ± 1.9 pF (n = 16). The relatively small error bars in each group combined with the high correlation coefficients of the Hill equation fits to the data (see Fig. 3) gave us confidence in our ability to determine accurately the Ca2+ dependence of IClCa in phosphorylated and dephosphorylated conditions.

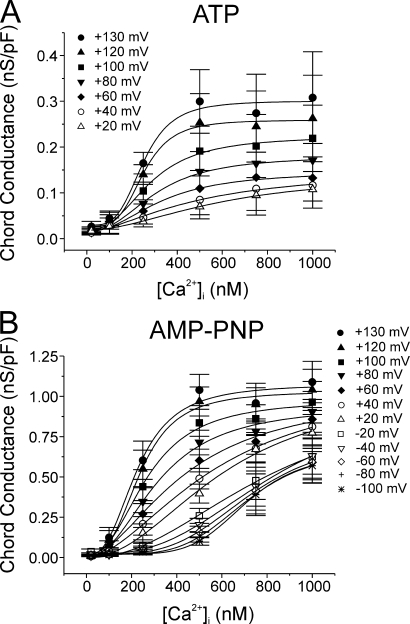

Figure 3.

Calcium dependence of IClCa at different membrane potentials recorded after prolonged cell dialysis with ATP or AMP-PNP. For the experiments conducted with ATP (A; n = 3–13) and AMP-PNP (B; n = 5–16), all data from experiments identical to those described in Fig. 2 were pooled and the mean chord conductance ± SEM (calculated using Eq. 1 in the Materials and Methods) at each step potential plotted as a function of pipette Ca2+ concentration ranging from 20 to 1000 nM Ca2+. Data at many potentials were purposely omitted for the sake of clarity but values extracted from such potentials are represented in Fig. 4. Each data set was fitted with the Hill equation (Eq. 1 in Materials and Methods) for determination of the Ca2+ affinity and Hill coefficient at a given step potential, which are described in Fig. 4. In A, the Ca2+ dependence of the chord conductance measured with ATP at potentials negative to 0 mV could not be fitted due to the small and variable magnitude of the macroscopic IClCa recorded in the negative range of membrane potentials. All plots were generated from data obtained after 20 min of cell dialysis with either nucleotide.

IClCa was evoked immediately upon rupture of the cell membrane, and the voltage-dependent properties were monitored every 10–20 s by stepping from a holding potential (Vh) of −50 mV to either +70 or +90 mV for 750 ms or 1 s, followed by repolarization to −80 mV for 0.5 or 1 s. Current–voltage relationships were constructed by stepping in 10-mV increments from Vh to test potentials between −100 mV and +130 mV for 1 s after 20 min dialysis. IClCa was represented as the chord conductance normalized to cell capacitance determined from a 10-mV hyperpolarizing pulse from Vh. The calcium dependence of IClCa was determined at each test potential by plotting the mean conductance at the end of the test step (t = 1 s) from n cells against pipette [Ca2+] and fitting the data with the Hill equation (Eq. 1) lacking fitting constraints on upper and lower asymptotes. For Eq. 1, Y is the Cl− conductance (nS/pF), Ymax is the maximal conductance, Kd is the apparent binding affinity constant, η is the Hill coefficient, and c is a constant:

|

(1) |

The voltage dependence of IClCa generation was assessed by plotting the mean chord conductance against test potential for each pipette [Ca2+]. These data were then fitted by a Boltzmann function (Eq. 2) where G is the conductance at a given potential, G max is the maximum conductance, V is the voltage, V0.5 is the voltage required for half-maximal amplitude, k is the steepness of the voltage dependence, and c is a constant:

|

(2) |

The kinetics of IClCa were generally well fitted by a single exponential function although two exponential terms were required in some cases at higher [Ca2+] (e.g., >500 nM; see Fig. 9). The formula describing such fits is the following:

|

(3) |

where I is the amplitude of the current, A 1 (equal to 0 for a single exponential term) and A 2 are the amplitudes of the fast and slow component of deactivation, respectively, t is the time, τfast and τslow are the fast and slow time constant deactivation, respectively, and c is a constant.

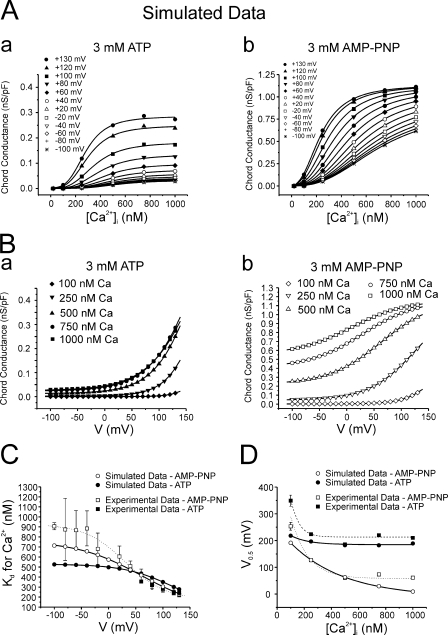

Figure 9.

Comparison of experimental and simulated IClCa data. (A) Plots of simulated chord conductance vs. [Ca2+]i relationships derived from analysis of data generated with the ATP (a) and AMP-PNP (b) models at potentials ranging from −100 to +130 mV (HP = −50 mV), as indicated by the different symbols. All solid lines are fits of the simulated sets of data to the Hill equation (Eq. 1) calculated by Origin software. Parameters calculated from such fits are presented in C. Please note the remarkable similarity between such graphs and those represented in Fig. 3. (B) Plots of simulated chord conductance vs. voltage relationships derived from analysis of data generated with the ATP (a) and AMP-PNP (b) models at [Ca2+]i ranging from 100 to 1000 nM Ca2+ as indicated by the different symbols. All solid lines are fits of the simulated sets of data to the Boltzmann equation (Eq. 2) calculated by Origin software. Parameters calculated from such fits are presented in D. Again, note the high similarity between these relationships and those derived from the experimental results described in Fig. 5. (C) Graph showing the relationship between estimated EC50 for Ca2+ and step potential for experimental (squares) and simulated (circles) data obtained with ATP (filled symbols) and AMP-PNP (empty symbols). The two experimental data sets (ATP and AMP-PNP) and the fit (dotted line; AMP-PNP) are reproduced from Fig. 4 for comparison. The solid lines passing through the two sets of simulated data are Boltzmann fits (Eq. 2) described by the following formulas: ATP, EC50 for Ca2+ = {443.07/[1 + exp((V − 118)/44.6)]} + 85.4; AMP-PNP: EC50 for Ca2+ = {686.4/[1 + exp((V − 59.5)/58.8)]} + 74.7, where V is membrane potential. (D) Graph showing the relationship between the half-maximal activation voltage (V0.5) estimated and internal Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) for experimental (squares) and simulated (circles) data obtained with ATP (filled symbols) and AMP-PNP (empty symbols). The two experimental data sets and associated fits (dashed and dotted lines) are reproduced from Fig. 6 for comparison. The solid lines passing through the two sets of simulated data are single exponential fits (Eq. 3) described by the following formulas: ATP, V 0.5 = 260.2 * exp(−[Ca2+]i/398.4) − 11.4; AMP-PNP, V 0.5 = 73.5 * exp(−[Ca2+]i/128.8) + 184.5.

Solutions

Single pulmonary arterial myocytes were isolated by incubating pulmonary arterial tissue strips in the following low Ca2+ PSS (in mM): NaCl (120), KCl (4.2), NaHCO3 (25; pH 7.4 after equilibration with 95% O2–5% CO2 gas), KH2PO4 (1.2), MgCl2 (1.2), glucose (11), taurine (25), adenosine (0.01), and CaCl2 (0.01 or 0.05). The K+-free bathing solution used in all patch clamp experiments had the following composition (in mM): NaCl (126), HEPES-NaOH (10, pH 7.35), TEA (10), glucose (20), MgCl2 (1.2), and CaCl2 (1.8). The pipette solution had the following composition (in mM): TEA (20), CsCl (106), HEPES-CsOH (10, pH 7.2), BAPTA (10), GTPNa2 (0.2), MgCl2 (0.42), and either 3 mM ATP or 3 mM AMP-PNP (both Mg and Na salts of ATP were used because a Mg salt of AMP-PNP was unavailable and quantitatively similar results were obtained) or no added nucleotide (0 ATP). All enzymes and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Computer Simulations

The behavior of macroscopic ClCa channel activity in pulmonary artery myocytes dialyzed with ATP and AMP-PNP was mathematically simulated using Markov chain kinetic models that were solved numerically by Axon Engineer software (version 2.11c, Aeon Software Inc.) run under DOS on a PC (Pentium III, 800 MHz) running under Windows ME platform. Ordinary differential equations were simultaneously solved by the Gear numerical integration method using incremental time steps of 0.1 μs in duration with enabled stiffness constraint. All voltage clamp simulations lasted 2.5 s and were initiated from a holding potential of −50 mV under steady-state conditions. Simulated time-dependent currents elicited with 20, 100, 250, 500, 750, and 1000 nM Ca2+ for potentials ranging from −100 to +140 mV (20-mV increments), and steady-state conductance vs. voltage curves at each [Ca2+] generated by Axon Engineer were exported in ASCII format into Microsoft Office Excel 2003 and then into Origin 7.5 (OriginLab Corp.). The specific parameters and equations used in the simulations are listed in Table I.

TABLE I.

Parameters Used To Compute the Mathematical Model Describing the Impact of Global Phosphorylation Status on the Regulation of IClCa

| ATP | AMP-PNP | Units | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conductance and equilibrium potential | |||

| Maximal conductance | 1.16 | 1.16 | mS/cm2 |

| ECl | 0 | 0 | mV |

| Values of gating variables | |||

| C 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| C 2.Ca | 0 | 0 | |

| C 3.2Ca | 0 | 0 | |

| C 4.3Ca | 0 | 0 | |

| O 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| O 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| O 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| Ca2+ binding rates | |||

| k on(C 1→C 2.Ca) | 20 × 106 | 20 × 106 | M−1s−1 |

| k on(C 2.Ca→C 3.2Ca) | 20 × 106 | 20 × 106 | M−1s−1 |

| k on(C 2.Ca→C 3.2Ca) | 20 × 106 | 20 × 106 | M−1s−1 |

| Unbinding rates | |||

| k off(C 2.Ca→C 1 + Ca) | 50 | 50 | s−1 |

| k off(C 3.2Ca→C 2.Ca + Ca) | 50 | 50 | s−1 |

| k off(C 4.3Ca→C 3.2Ca + Ca) | 50 | 50 | s−1 |

| Channel opening rates | |||

| α1(C 2.Ca→O 1) | 75 | 75 | s−1 |

| α2(C 3.2Ca→O 2) | 150 | 150 | s−1 |

| α3(C 4.3Ca→O 3) | 300 | 300 | s−1 |

| Channel closing ratesa | |||

| β1(V)(O 1→C 2.Ca) | |||

| where a, V 0.5, and k = | 10, 75, and 50 | 5, 90, and 50 | s−1, mV, mV |

| β2(V)(O 2→C3.2Ca) | |||

| where a, V 0.5, and k = | 75, 120, and 50 | 5, 0, and 50 | s−1, mV, mV |

| β3(V)(O 3→C4.3Ca) | |||

| where a, V 0.5, and k = | 100, 120, and 50 | 5, −60, and 50 | s−1, mV, mV |

All βx(V) used the following Boltzmann equation form: βx(V) = a/{1 + exp [(V − V0.5)/k]}.

Statistical Analysis

All data were accrued from n cells taken from at least three different animals with error bars representing the SEM unless otherwise stated (e.g., Figs. 5 and 7). For each experimental day, IClCa was evoked by ATP-containing pipette solutions alternated with AMP-PNP–containing pipette solutions, i.e., the comparison between ATP and AMP-PNP was maintained for each set of cells. All data were first pooled in Excel and means exported to Origin 7.5 software for plotting and curve fitting. Time constants of activation and deactivation were determined by curve fitting of individual current traces using Clampfit (PClamp, version 8.2; Molecular Devices Corp.) and the data exported to Excel 2003 and Origin 7.5 software. All graphs and current traces were exported to CorelDraw 12 for final processing of the figures. Statistica for Windows 99 (version 5.5) was used to determine statistical significance between groups with one-way or two-way ANOVA tests followed by Fisher LSD post-hoc multiple range tests in multiple group comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

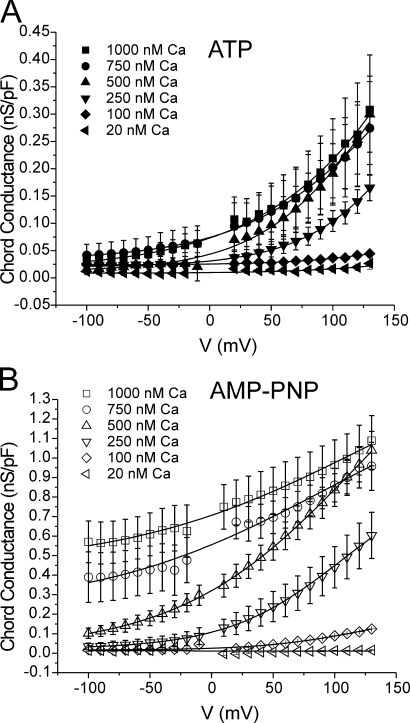

Figure 5.

Voltage dependence of IClCa analyzed after prolonged dialysis with ATP and AMP-PNP. The same data from the experiments described in Fig. 2 were used to construct the voltage dependence of IClCa for each pipette Ca2+ concentration ranging from 100 to 1000 nM in the presence of 3 mM ATP (A) or AMP-PNP (B). The two graphs shown in A and B report the mean ± SEM chord conductance of fully activated IClCa as a function of step potential ranging from −100 to +130 mV. Data points at or around 0 mV were not included due to the small current near the equilibrium potential for Cl−. All lines are least-square Boltzmann fits to the data (Eq. 2) from which we extracted the half-maximal voltage (V 0.5), which are reported in Fig. 6. All sigmoidal relationships in the two panels were fitted by constraining each fit to a maximal conductance of 1.16 nS/pF; the latter value is the mean of the maximal conductance estimated from curve fitting of the data obtained with 500, 750, and 1000 nM Ca2+ and AMP-PNP, which yielded similar estimates. Mean data points in A and B are reproduced from Fig. 3 but plotted differently. All plots were generated from data obtained after 20 min of cell dialysis with either nucleotide.

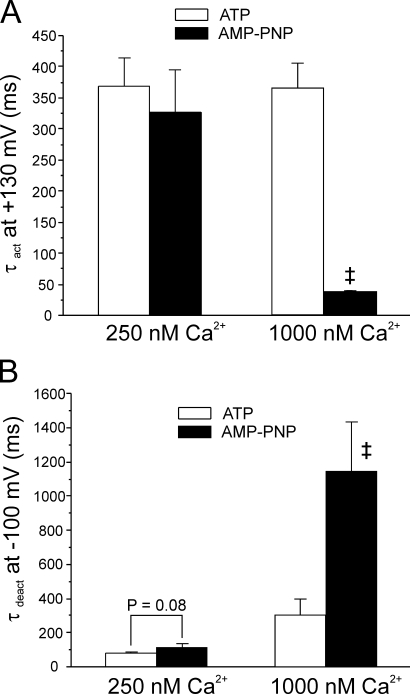

Figure 7.

Ca2+ dependence of IClCa kinetics recorded from ATP- and AMP-PNP–loaded myocytes. (A and B) Bar graphs summarizing the effects of cell dialysis with 3 mM ATP (open bars) or 3 mM AMP-PNP (filled bars) on the time constant of activation at +130 mV (τact; A) and deactivation at −100 mV (τdeact; B) of IClCa elicited with either 250 or 1000 nM Ca2+ in the pipette solution. Please note in B that τdeact measured in AMP-PNP and 1000 nM Ca2+ is the slower of the two time constants of deactivation estimated by least-squares biexponential fitting. For both panels, each bar represents a mean ± SEM of four to five measurements. Two-way ANOVA tests were used to assess statistical significance between mean data obtained in ATP and AMP-PNP; with 1000 nM Ca2+, mean τact (A) and τdeact (B) in ATP were significantly different from those estimated with AMP-PNP (‡, P < 0.001, determined with LSD post-hoc test). Both bar graphs were generated from data obtained after 20 min of cell dialysis with either nucleotide. A more thorough analysis of the effects of the two nucleotides on IClCa kinetics can be found in the online supplemental material.

Online Supplemental Material

Full details of the kinetic analysis of IClCa recorded in myocytes dialyzed with ATP or AMP-PNP and the parameters used for the computer simulations can be found in the online supplemental material (available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200609507/DC1).

RESULTS

Cell Dialysis with AMP-PNP, a Nonhydrolyzable Analogue of ATP, Attenuates the Rundown of IClCa in Pulmonary Artery Myocytes

Under conditions prohibiting the activity of K+ channels, intracellular dialysis of rabbit pulmonary artery myocytes with a pipette solution containing free Ca2+ concentration >100 nM consistently elicited a membrane current that had characteristics identical to the “classical” Ca2+-activated Cl− current (IClCa) evoked by a similar method in this preparation (Greenwood et al., 2001; Piper et al., 2002; Greenwood et al., 2004) and other cell types (Evans and Marty, 1986; Arreola et al., 1996; Nilius et al., 1997; Kuruma and Hartzell, 2000; Ledoux et al., 2003). These include the following: (a) anion selectivity with a permeability sequence of SCN− ≫ I− > Cl− ≫ aspartate; (b) activation by [Ca2+]i in the range of 100 to 1000 nM; (c) strong outward rectification due to voltage-dependent gating; (d) time-dependent activation and deactivation; and (e) sensitivity to block by niflumic acid, a putative IClCa blocker. This approach bears a great advantage over other conventional methods used to elicit IClCa (e.g., by spontaneous or evoked Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, or by Ca2+ entry through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels; for a review see Leblanc et al., 2005) in that potentially undesirable effects of manipulating phosphorylation status on the Ca2+ source triggering IClCa can be effectively eliminated, thus allowing a direct study of how phosphorylation influences the channels themselves or any regulatory subunits.

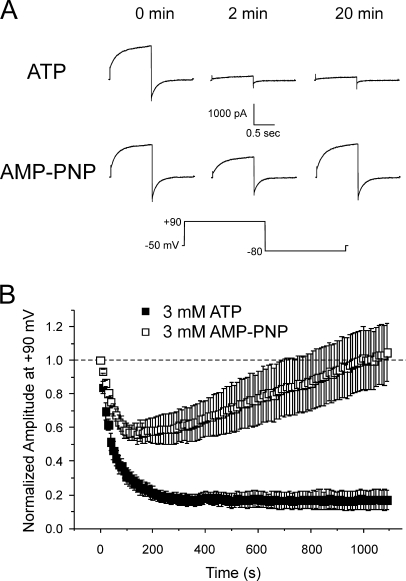

Fig. 1 A shows that IClCa elicited by 500 nM Ca2+ exhibited rapid rundown in cells dialyzed with 3 mM ATP. The amplitude of IClCa remained constant once the initial rundown period had passed so that after the 20-min recording period, the relative amplitude of IClCa was 17 ± 6% of initial control amplitude at t = 0 (n = 5; Fig. 1 B). In contrast, IClCa elicited with pipette solutions containing 500 nM Ca2+ and AMP-PNP, a nonhydrolyzable analogue of ATP, recovered steadily after an initial attenuated rundown so that after 20 min recording, the amplitude of IClCa at +90 mV was 105 ± 17% of the current recorded at t = 0 (n = 6; Fig. 1 B). The pattern of rundown and recovery of IClCa was similar in experiments performed with a pipette solution lacking ATP (nominally zero ATP; unpublished data). These data are consistent with recent findings showing that IClCa in smooth muscle cells is down-regulated by phosphorylation through CaMKII, an effect that is antagonized, at least in part, by calcineurin (Greenwood et al., 2001, 2004; Ledoux et al., 2003). These observations suggest that the rundown of IClCa in pulmonary artery myocytes dialyzed with ATP was likely due to a shift in the phosphorylation status in the vicinity of the channel. The following series of experiments aimed to determine the biophysical mechanisms driving IClCa gating under different conditions of global cellular phosphorylation, that is after 20 min cell dialysis with 3 mM ATP or 3 mM AMP-PNP.

Figure 1.

Attenuation of rundown of Ca2+-activated Cl− current in rabbit pulmonary artery myocytes by intracellular dialysis with a nonhydrolyzable form of ATP, AMP-PNP. (A) Representative current traces from typical experiments showing the time-dependent changes of Ca2+-activated Cl− current recorded from pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells dialyzed with 500 nM Ca2+ and 3 mM ATP (first row) or 3 mM AMP-PNP (second row). Currents recorded immediately after breaking the seal (0 min), and after 2 and 20 min of cell dialysis were elicited by repetitive steps (every 10 s) to +90 mV lasting 1 s from a holding potential (HP) of −50 mV . Each depolarizing pulse to +90 mV was followed by a repolarizing step to −80 mV to enhance the magnitude of the tail current. The voltage clamp protocol is shown below the traces. (B) Similar to the experiments depicted in A, this graph shows the mean time course of changes of normalized IClCa amplitude elicited by 1-s depolarizing pulses to +90 mV, followed by 1-s repolarizing steps to −80 mV, in the presence of 3 mM ATP (filled squares; n = 5) or 3 mM AMP-PNP (empty squares; n = 6); each step was applied from HP = −50 mV at a frequency of one pulse every 10 s for 20 min. Please note the attenuation of rundown of IClCa and the delayed recovery of this current in cells dialyzed with AMP-PNP.

Ca2+ Dependence of IClCa

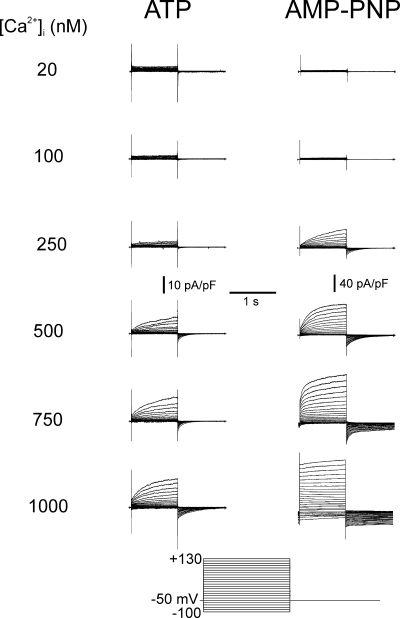

To obtain quantitative information about the impact of phosphorylation on Ca2+-activated Cl− channels, we studied the effect of dialyzing pulmonary artery myocytes with pipette solutions containing different free [Ca2+] and either ATP or AMP-PNP. With pipette solutions containing ATP and 20 nM free Ca2+ no time-dependent current was evoked at the holding potential of −50 mV and no outward relaxations were recorded upon membrane depolarization up to +130 mV (Fig. 2, left). Similarly, 100 nM Ca2+ elicited negligible current at −50 mV, but in some cells, test steps to potentials positive to +80 mV produced an instantaneous outward current followed by an outward relaxation that was well fitted by a single exponential. When pipette solutions contained Ca2+ in the range of 250 to 1000 nM, progressively greater inward current was generated at −50 mV, and time-dependent outward relaxations were observed with depolarizing test steps that were followed by prominent time-dependent inward tail currents upon repolarization to −50 mV. With AMP-PNP in the pipette solution, the threshold for activation of IClCa was similar to that observed for ATP-containing pipette solutions (Fig. 2, right). Dialysis with 20 nM Ca2+ had a negligible effect on membrane currents, and only occasionally were time-dependent currents observed at very depolarized potentials in response to 100 nM Ca2+. However, with 250 and 1000 nM Ca2+, much larger IClCa with distinctive outward relaxations were evoked. The kinetics of the outward relaxation and subsequent inward current upon repolarization were dependent on [Ca2+] and are analyzed in a later section.

Figure 2.

General properties of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents recorded from cells dialyzed with distinct free Ca2+ concentrations in the presence of ATP or AMP-PNP. Typical families of IClCa recorded with pipette solutions containing 20, 100, 250, 500, 750, or 1000 nM Ca2+, with either 3 mM ATP (left) or 3 mM AMP-PNP (right). All families of currents were evoked by the protocol shown at bottom. Notice the different vertical calibration bars for the traces recorded with ATP and AMP-PNP. Besides being much larger in cells dialyzed with AMP-PNP versus ATP, IClCa activated more quickly and deactivated more slowly with AMP-PNP. All traces were obtained after 20 min of cell dialysis.

The Ca2+ dependence of IClCa at different potentials was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. While the maximal conductance of IClCa was more than threefold larger in AMP-PNP–containing myocytes, IClCa displayed a similar Ca2+ dependence in the two cell groups with a threshold between 100 and 250 nM Ca2+ and a maximum lying between 500 and 1000 nM depending on the voltage (Fig. 3). Ca2+-dependent activation curves for cells dialyzed with ATP could not be determined for potentials below the predicted ECl (∼0 mV) as the currents were too small in the negative range of membrane potentials. Also apparent from the plots in Fig. 3 (A and B) was the progressive rightward shift of the Ca2+ dependence of IClCa with membrane hyperpolarization.

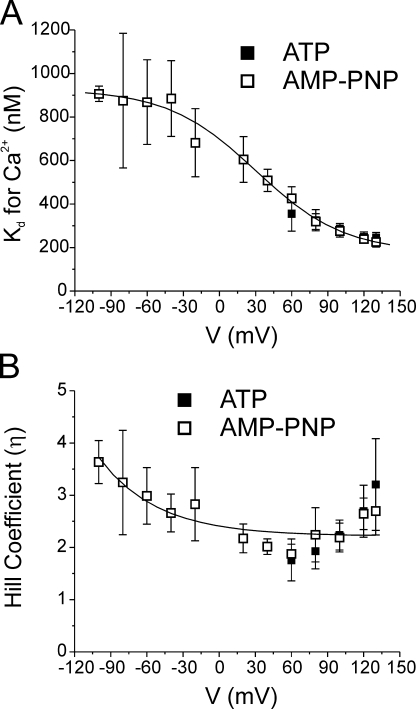

A more detailed analysis of the impact of the two nucleotides on the Ca2+ dependence of IClCa is shown in Fig. 4. Panel A shows a graph reporting the voltage dependence of the apparent Kd for Ca2+ obtained with ATP (filled squares) and AMP-PNP (empty squares). In both cases, the apparent Kd decreased with membrane depolarization from ∼400 nM at +60 mV to ∼200 nM at +130 mV. However, only the data obtained with AMP-PNP could be fitted with confidence over the entire range of membrane potentials examined (due to much larger currents measured at negative potentials). We also determined the effects of membrane potential on the Hill coefficient in the two cell groups. The data obtained with AMP-PNP indicate that the Hill coefficient η decreased exponentially as function of membrane potential from ∼3 at −100 mV to a minimal level of ∼2 at potentials >0 mV. The range of values of η and its voltage dependence are similar to those reported for IClCa in Xenopus oocytes (Kuruma and Hartzell, 2000). Again, Hill coefficients could not be determined for the ATP data at potentials more negative than +60 mV. However, as for the apparent Kd, there were no significant differences in η between the two groups of data at potentials ranging from +60 to +130 mV. Thus, neither a change in Ca2+ sensitivity of the channels nor the number of Ca2+ ions activating the channel is responsible for the alterations of the biophysical properties of IClCa in response to global changes in phosphorylation status of the smooth muscle cell.

Figure 4.

The Ca2+ sensitivity and number of Ca2+ ions required for activation of IClCa are not influenced by the global state of phosphorylation. (A) Graph showing the voltage dependence of the Ca2+ affinity of IClCa (apparent Kd for Ca2+) derived from experiments obtained with 3 mM ATP (filled squares) or 3 mM AMP-PNP (empty squares). Mean Kd ± fitting error (error scaled to the square root of reduced χ2 as calculated by Origin software) for Ca2+ at each voltage was estimated from curve fitting of the data to the Hill equation as represented in Fig. 3. The line passing through the data points is a Boltzmann fit to the data points and is described by the following parameters: Kd for Ca2+ = {748.1/ [1 + exp((V − 30.3)/36.7)]} + 178.42, where V is membrane potential. (B) Graph illustrating the voltage dependence of the Hill or cooperativity coefficient (η) obtained from analysis of the Ca2+ dependence of IClCa with the Hill equation (Fig. 3) after 20 min of cell dialysis with ATP (filled squares) or AMP-PNP (empty squares). The solid line is a single exponential least-square fit to the data and is described by the following formula: η = 0.19 * exp(−V/48.3) + 2.22, where V is membrane potential. All plots were generated from data obtained after 20 min of cell dialysis with either nucleotide.

Voltage Dependence of IClCa

Activation of IClCa has an obligatory requirement for an increase in [Ca2+], as discussed above (also see Leblanc et al., 2005). However, the current–voltage relationship (I-V) of IClCa in pulmonary artery myocytes and other cell types at steady state is outwardly rectifying (Arreola et al., 1996; Nilius et al., 1997; Kuruma and Hartzell, 2000; Greenwood et al., 2001; Ledoux et al., 2003; Greenwood et al., 2004), suggesting that activation of IClCa is influenced by voltage. In the present study the voltage dependence of IClCa activation was ascertained by fitting the normalized maximal Cl− conductance at a given [Ca2+] with the Boltzmann function (Eq. 2). All data were collected after 20 min dialysis. In ATP and AMP-PNP recording conditions, membrane depolarization increased the amplitude of IClCa at all [Ca2+] tested.

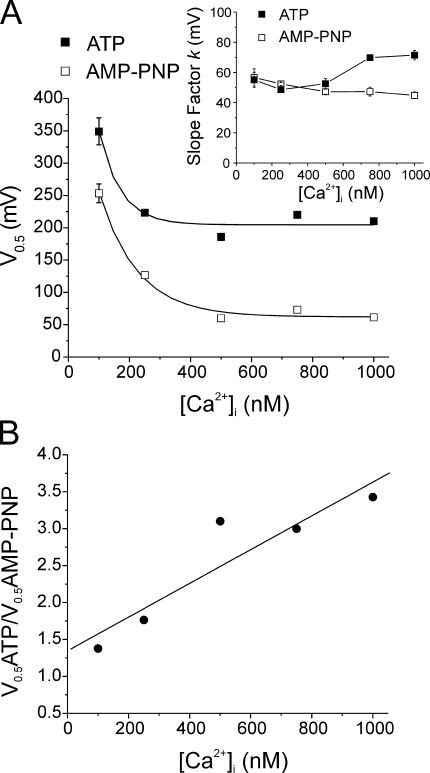

As shown in Fig. 5, the voltage dependence of activation of IClCa spanned >230 mV, exceeding the practical range of measurement. The half-maximal activation voltage (V 0.5) values in ATP and AMP-PNP at low Ca2+ were positive to +130 mV. To characterize the voltage dependence of current activation, we fitted the data with a Boltzmann function. The data generated with AMP-PNP (Fig. 5 B) for 500, 750, and 1000 nM Ca2+ extrapolated to maximum conductances between 0.95 and 1.78 nS/pF with an average of 1.16 nS/pF. The fact that extrapolation of the Boltzmann relationships calculated for these three data sets, each of which started at a different basal level in the negative range of membrane potentials (Fig. 5 B), yielded similar extrapolated maximal conductances (considering they were obtained from different experimental series) provided support to our approach of using the mean value of 1.16 nS/pF as the maximum conductance to fit all data sets (see Discussion). In both groups, increasing the pipette [Ca2+] produced a leftward shift in the voltage-dependent activation, manifest as a decrease in the calculated potential for V 0.5. However, the most remarkable difference between cells dialyzed with ATP (Fig. 5 A) and AMP-PNP (Fig. 5 B) was the large elevation of the minimal or basal conductance level at negative potentials in the cells dialyzed with AMP-PNP for pipette [Ca2+] ≥ 250 nM. A consequence of the marked basal elevation of ClCa conductance was that the channels were less influenced by membrane potential within the physiological range of voltages, especially at higher intracellular Ca2+ levels (750 and 1000 nM Ca2+). For example, ClCa conductance only increased from 0.59 ± 0.11 nS/pF at −60 mV to 0.63 ± 0.13 nS/pF at −20 mV with 1000 nM Ca2+.

Fig. 6 A shows that an exponential function described the relationship between V 0.5 and [Ca2+] in both groups. Importantly, the AMP-PNP curve was significantly lower than that obtained with ATP again, indicating an increased sensitivity to voltage at all Ca2+ levels examined. Plots of the Ca2+ dependence of the slope factor k for the calculated Boltzmann relationships are displayed in the inset of Fig. 6 A and reveal a small but significant enhancement of the steepness of the voltage dependence of IClCa at [Ca2+]i > 500 nM with AMP-PNP vs. ATP. Fig. 6 B shows that the ratio of V 0.5 recorded with ATP and AMP-PNP internal solutions at a given [Ca2+] was linearly related to the pipette [Ca2+]. These data show that under control conditions where phosphorylation is supported, the activation of IClCa by internal Ca2+ can be augmented considerably by depolarization because the recorded currents are elicited at potentials that are far away from the apparent V 0.5. However, when phosphorylation is prohibited by AMP-PNP dialysis, the recorded currents are augmented less by depolarization because they are registered at potentials nearer to saturation, especially with elevated [Ca2+]. In both cases, the level of Ca2+ in the internal solution caused an “apparent” modulation of the voltage sensor, which was more prominent in cells dialyzed with AMP-PNP.

Figure 6.

A reduction in the global state of phosphorylation by cell dialysis with AMP-PNP causes a pronounced shift of the voltage dependence of IClCa toward negative potentials. (A) From the experiments conducted with pipette solutions containing ATP (filled squares) or AMP-PNP (empty squares), the mean ± fitting error (error scaled to the square-root of reduced χ2 as calculated by Origin software) of half-maximal activation voltages (V 0.5) determined from the analyses outlined in Fig. 5 (Eq. 2) were plotted as a function of internal Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]). The lines passing through the data points are least-square exponential fits to the data points and are described by the following formulas: ATP, V 0.5 = 608.8 * exp(−[Ca2+]/69.2) + 205.5; AMP-PNP, V 0.5 = 482.3 * exp(−[Ca2+]/119) + 66.1. Inset, graph illustrating the Ca2+ dependence of the slope factor k extracted from analysis of the voltage dependence of the conductance of IClCa (Fig. 5) measured with ATP (filled squares) and AMP-PNP (empty squares). As for V 0.5, each data point is mean ± fitting error (error scaled to the square-root of reduced χ2 as calculated by Origin software) of the k value determined for each data set. (B) In this graph, the ratio of the mean half-maximal voltage obtained in ATP over that in AMP-PNP (V 0.5ATP/V 0.5AMP-PNP; derived from A) was plotted as a function of pipette Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i). The slope of the linear regression passing through the calculated data points is significantly different from 0, with P = 0.025. The parameters of the equation determining this regression are: V 0.5ATP/V 0.5AMP-PNP = 0.0023 * [Ca2+]i + 1.35 (r2 = 0.852). All plots were generated from data obtained after 20 min of cell dialysis with either nucleotide.

Kinetics of IClCa Evoked by Different Pipette [Ca2+]

The time-dependent increase in outward current at positive potentials is a distinctive feature of Ca2+-gated Cl− channels and reflects an increase in the fraction of open channels relative to those open at the holding potential. As stated above, increasing the [Ca2+] in the pipette solution increased the amplitude of the outward relaxation. Repolarization to −80 mV produced large deactivating inward IClCa. The decay of these currents was generally well fitted by a single exponential although double exponential functions were required to fit the data with pipette containing >750 nM Ca2+ with ATP and >500 nM Ca2+ with AMP-PNP. A detailed analysis of the voltage and Ca2+ dependence of the activation and deactivation kinetics of IClCa recorded in ATP and AMP-PNP is provided in the online supplemental material (available at http://ww.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200609507/DC1). Fig. 7 gives an abbreviated account of our kinetic analyses at two [Ca2+] spanning the activation of IClCa, 250 and 1000 nM. Except for ATP and 250 nM Ca2+, where regression analysis revealed a slope significantly different from 0 (P = 0.035), the time constant of activation (τact) did not vary as a function of voltage in cells dialyzed with ATP or AMP-PNP at all pipette [Ca2+] tested (P ≥ 0.298; unpublished data; see Fig. S1 A). Fig. 7 A shows that the time constant of activation (τact) of IClCa at +130 mV was Ca2+ independent in cells dialyzed with ATP. However, although τact was similar with 250 nM Ca2+ in ATP- and AMP-PNP–loaded myocytes, elevation of [Ca2+]i to 1000 nM accelerated the kinetics of activation of IClCa with AMP-PNP but not with ATP. These results suggest that phosphorylation of the Cl− channel may mask a Ca2+-dependent increase in the rate of activation.

Fig. 7 B shows that a similar trend, albeit in the opposite direction, was apparent when analyzing the Ca2+ dependence of the time constant of deactivation the slow tail current (τdeact) produced by IClCa (τdeact). With both ATP and AMP-PNP, increasing [Ca2+]i slowed IClCa deactivation. In comparison to ATP, IClCa in cells dialyzed with AMP-PNP deactivated more slowly (the difference at 250 nM Ca2+ was just at the limit of significance with P = 0.080), an effect that was accentuated at higher [Ca2+]i (note that for [Ca2+]i > 500 nM, the slow time constant of deactivation in AMP-PNP was compared with the single τdeact measured with ATP; see online supplemental material for further details). This is visually apparent when examining the typical currents shown in Fig. 2 where complete IClCa deactivation with AMP-PNP at higher [Ca2+]i required several seconds. Except for 1000 nM Ca2+, τdeact gradually increased with membrane potential at [Ca2+]i in the range of 250 to 750 nM in cells loaded with ATP (unpublished data; see Fig. S2 B). This is in line with the well known voltage dependence of deactivation of this current in smooth muscle cells (Large and Wang, 1996). At all [Ca2+]i tested, the difference of τdeact between ATP- and AMP-PNP–loaded myocytes declined with membrane potential with no significant difference at potentials >0 mV (unpublished data; see Fig. S2 B). These results indicate that global dephosphorylation reduced the rate of channel closure, an effect that was only apparent at negative potentials and more prominent at higher [Ca2+]i.

Computer Simulations

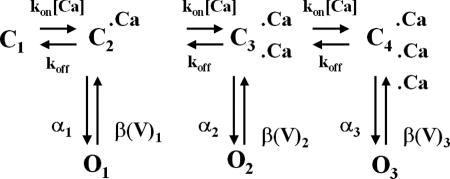

The behavior of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents recorded with ATP and AMP-PNP was simulated mathematically using methods employed previously by our group (Remillard and Leblanc, 1996; Ledoux et al., 2005) based upon the following scheme proposed by Kuruma and Hartzell (2000) to describe IClCa recorded from Xenopus oocytes.

|

(SCHEME 1) |

We adapted this model to best reproduce our data by implementing only minor modifications to the parameters used by Kuruma and Hartzell (2000). A full justification for setting and adjusting the rate constants and gating variables of the various kinetic steps is provided in the online supplemental material. This model incorporates the binding of three Ca2+ ions (suggested by our experimental data; see Fig. 4 B) and allows the channel to open (O 1, O 2, and O 3) from each of the Ca2+-bound states (C 1–C 4). In this model, the rate of Ca2+ binding is a simple first-order reaction scheme that is directly proportional to [Ca2+] and is equal to [Ca2+] * kon, where k on is a rate constant in M−1s−1; the rate of channel closure is voltage dependent (β1, β2, and β3; units are s−1). Similar to Kuruma and Hartzell (2000), transitions between the three open states were forbidden. We first modeled IClCa as recorded from AMP-PNP–loaded cells because our analysis of the voltage dependence of IClCa showed that a maximal ClCa conductance of 1.16 mS/cm2 was consistently observed for pipette [Ca2+] ≥ 500 nM Ca2+ in these experiments (Fig. 5 B), and this dictated an upper conductance limit for both groups of data. Since our results indicated that the Ca2+ sensitivity of IClCa and Hill coefficient were not significantly different between ATP- and AMP-PNP–loaded myocytes, at least at positive potentials, the only parameters that were adjusted were the value of the gating variables (between 0 and 1), which determines whether the channel is closed or open, and the magnitude and voltage dependence of the closure rate constants. All other parameters were identical as shown in Table I. To incorporate the effects of phosphorylation into the model, we noted the lack of Ca2+ dependence of τact in the presence of ATP (see Fig. S1 A) and we thus hypothesized that phosphorylation causes open channel block at higher Ca2+ bound states (O 2 and O 3). Accordingly, we set the gating variable of O 2 and O 3 to 0 for the ATP model (Table I). We also increased the magnitude of the rates of closure (β(V)x) and shifted the voltage dependence toward more positive potentials compared with currents recorded with AMP-PNP (Table I).

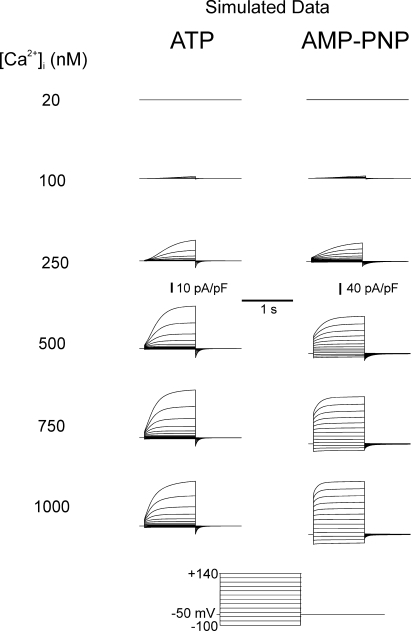

Fig. 8 shows families of simulated IClCa currents elicited from a holding potential of −50 mV with [Ca2+] facing the internal side of the membrane ranging from 20 to 1000 nM in conditions that support phosphorylation (ATP) or conditions that prohibit phosphorylation (AMP-PNP). Currents were generated at different potentials from −100 to +140 mV applied for 1 s. As for experimentally derived data, much larger currents were simulated in the presence of AMP-PNP than ATP (notice the different vertical calibrations). In both groups, threshold for activation was near 100 nM and saturated between 750 and 1000 nM Ca2+. Currents in ATP displayed signs of strong outward rectification at all [Ca2+], whereas this feature was much less apparent for the AMP-PNP–simulated currents especially at higher [Ca2+]. Indeed with [Ca2+] ≥ 500 nM, large instantaneous currents were apparent, which reflected high occupancy of the open states at the holding potential. A visual inspection of Fig. 8 also shows that the kinetics of activation are faster and the kinetics of deactivation are slower with AMP-PNP versus ATP. A short survey comparing some kinetic parameters of experimental and modeled data can be found in the online supplemental material, which demonstrates a very good correlation between our computer-simulated currents and IClCa measured in our experiments.

Figure 8.

Modeling of IClCa under conditions simulating prolonged cell dialysis with ATP or AMP-PNP. The nomenclature of this figure is identical to that of actual data shown in Fig. 2 except that the last potential of the voltage clamp protocol was +140 mV instead of +130 mV, and voltage steps were incremented by +20 mV from −100 mV. The conditions and parameters used for the simulation are described in the text (Materials and Methods and Results) and Table I. Again, note the different calibration bars for the simulations with ATP and AMP-PNP.

Fig. 9 A displays the Ca2+ dependence of steady-state activation obtained in ATP (panel a) and AMP-PNP (panel b) for potentials ranging from −100 to +130 mV as indicated. Notice the difference in maximal conductance between the two groups and the match with Fig. 3. In both cases, the affinity for Ca2+ shifted to higher levels of [Ca2+] with membrane hyperpolarization. This is better illustrated in Fig. 9 C, where the Kd for Ca2+ for model (solid lines) and experimental (dotted line: AMP-PNP) data in the two groups was plotted as a function of voltage. The simulated AMP-PNP curve matched quantitatively with that derived from experiments. The modeled ATP curve displayed a declining Boltzmann relationship reaching a value near 300 nM at +130 mV that compared well with an experimentally derived value of 246 ± 24 nM. The voltage dependence of simulated IClCa determined in the presence of ATP or AMP-PNP was also quantitatively similar to our experimental results (compare Fig. 9 B to Fig. 5). With ATP, the conductance of IClCa was very small at negative potentials and increased in a Ca2+-dependent manner at potentials >0 mV. In contrast, a marked basal elevation of IClCa was observed with AMP-PNP in the negative range of membrane potentials and was accompanied by a marked shift in its voltage dependence as a function of [Ca2+]i. Fig. 9 D shows a graph reporting the Ca2+ dependence of V 0.5 estimated from our simulations (data from Fig. 9 B; solid lines) overlaid with those measured experimentally (data from Fig. 6 A). Again, V 0.5 declined exponentially with [Ca2+]i in both groups and paralleled semi-quantitatively our experimental data, except at 100 nM Ca2+, where both models yielded V 0.5 values that were lower than those obtained in experiments. Overall, we found that the models reproduced a variety of our experimental results.

DISCUSSION

This study represents the first comprehensive investigation into the gating of Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels in smooth muscle cells under whole cell conditions and the effects of phosphorylation status on channel gating. Our experiments confirmed the absolute requirement for intracellular [Ca2+] to activate IClCa and a modulation of this activation by voltage. The apparent affinity for Ca2+ was increased at depolarized test potentials while an increase in the intracellular [Ca2+] produced a leftward shift in the voltage sensitivity of activation. Prohibiting phosphorylation by inclusion of the nonhydrolyzable ATP analogue, AMP-PNP, or by removal of ATP from the pipette solution, augmented IClCa considerably. This was not due to an increase in the apparent binding affinity for Ca2+ but resulted from an increase in the voltage sensitivity of the underlying channels. These data provide an important insight into the mechanism underlying the profound effect phosphorylation status has on the activity of Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels.

Comparison with Other Cell Types

Studies of IClCa have identified two forms of the current. In T84 epithelial cells, IClCa is time and voltage independent and the currents are activated solely by Ca2+ (Xie et al., 1996; Merlin et al., 1998; Xie et al., 1998). In all smooth muscle myocytes examined to date, including the pulmonary artery myocytes studied here, as well as a variety of other cell types, IClCa is controlled by both Ca2+ and voltage with characteristic activation and deactivation kinetics (for review see Frings et al., 2000; Hartzell et al., 2005; Leblanc et al., 2005). To investigate the mechanism of activation of IClCa, we (Greenwood et al., 2001, 2004; Britton et al., 2002; Ledoux et al., 2003) and others (Evans and Marty, 1986; Ishikawa and Cook, 1993; Arreola et al., 1996, Nilius et al., 1997; Qu et al., 2003; Boese et al., 2004) have used intracellular Ca2+ chelators such as EGTA or BAPTA to examine the time and voltage dependence of channel activation at constant [Ca2+]i. These studies have revealed qualitative similarities in the kinetics of gating but interesting variability in the Ca2+ sensitivity of the currents. The Ca2+ dependence of IClCa activation in rabbit pulmonary artery myocytes reported here was similar to that reported in other studies. Thus, at +60 mV, the apparent Kd for Ca2+ was ∼400 nM in the present study compared with 285 nM in bovine endothelial cells (Nilius et al., 1997) and 400 nM in medullary collecting duct cells (Qu et al., 2003; Boese et al., 2004). In contrast, activation of IClCa in parotid acinar cells required lower [Ca2+] (apparent Kd for Ca2+ at +70 mV was ∼60 nM, Arreola et al., 1996), whereas in Xenopus oocytes the Ca2+ sensitivity was lower (apparent Kd for Ca2+ at +120 mV was ∼900 nM, Kuruma and Hartzell, 2000). Interestingly, an extensive study of single Ca2+-activated Cl− channel activity in excised patches from rabbit pulmonary artery myocytes derived an EC50 value of 8 nM at +100 mV (Piper and Large, 2003), considerably higher than the Ca2+ sensitivity determined in the present study. The reason for this discrepancy is unknown but may reflect the highly regulated nature of these channels (see Leblanc et al., 2005 and below). Overall the channels underlying IClCa in an array of cell types, including vascular myocytes, exhibit similar basic gating properties with differing Ca2+ sensitivities.

The time-dependent development of current at positive potentials led to a current–voltage relationship that exhibited marked outward rectification although the channel conductance does not rectify inherently. Hence the voltage dependence of the open Cl− channel is approximately ohmic (Greenwood et al., 2001; Piper and Greenwood, 2003) and the unitary conductance does not change with depolarization (Piper and Large, 2003). Consequently, the outward rectification that is a characteristic of IClCa in these cells is a product of a time-dependent increase in channel activity (open probability). In parotid acinar, endothelial cells, and Xenopus oocytes this time-dependent property has been ascribed to an increase in Ca2+ sensitivity and a decrease in open to closed transitions at positive potentials (Arreola et al., 1996; Nilius et al., 1997; Kuruma and Hartzell, 2000). The data of the present study reveal that similar properties influence the kinetics of IClCa in vascular myocytes.

Working Model

The salient discoveries of our analysis were that generation of IClCa is augmented by membrane depolarization but has an obligatory requirement for an increase in [Ca2+]. Consequently, membrane hyperpolarization does not turn off IClCa when the pipette [Ca2+] is set to levels greater than the activation threshold (between 100 and 250 nM). This property was also observed for IClCa recorded from parotid acinar cells and Xenopus oocytes (Arreola et al., 1996; Kuruma and Hartzell, 2000) but differs from that of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels that can be opened by strong membrane depolarization in the absence of internal Ca2+ (Cui et al., 1997).

To gain better insight into the mechanism by which phosphorylation affects the gating of the ClCa channel in pulmonary myocytes, we took advantage of computer modeling techniques and the existence of already published kinetic models of ClCa in other cell types that well reproduced their macroscopic properties in pancreatic acinar cells (Arreola et al., 1996) and Xenopus oocytes (Kuruma and Hartzell, 2000). In the former model, there are two consecutive voltage-dependent Ca2+ binding steps, and binding of both Ca2+ ions is required for channel opening. Similar to Arreola et al. (1996), our data showed that the Kd for ClCa channel activation by intracellular Ca2+ declined with membrane depolarization. However, the Hill coefficient of ClCa channels increased from ∼1 at negative potentials to ∼2 at positive potentials, whereas ClCa channels in pulmonary myocytes (Fig. 5 B) required more than two Ca2+ ions (Hill coefficient of 2–4) for channel activation; moreover, this parameter declined rather than increased from ∼3 at negative potentials to ∼2 at potentials >0 mV, an observation similar to IClCa in Xenopus oocytes (Kuruma and Hartzell, 2000). All attempts to simulate our data with such a model failed to reproduce the Ca2+ and voltage dependence of IClCa in PA myocytes and their kinetics of activation and deactivation with ATP or AMP-PNP, although certain properties of the macroscopic current could be modeled reasonably well at any given concentration of Ca2+.

We therefore investigated the more complex model developed by Kuruma and Hartzell (2000), which described well the properties of IClCa in Xenopus oocytes and adapted it to simulate the gating of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels in pulmonary artery myocytes. Besides the fact that their model offered much more flexibility, the characteristics of IClCa recorded from Xenopus oocytes correlated better with the properties of “dephosphorylated” ClCa channels (AMP-PNP) in our preparation: (a) similar voltage dependence of the Kd for Ca2+ and Hill coefficient, (b) similar Ca2+ dependence of V 0.5, (c) lack of voltage dependence and similar Ca2+ dependence of τact at [Ca2+] > 200 nM, and (d) similar voltage and Ca2+ dependence of τdeact. As explained in Results, activation of the channel involves the consecutive binding of three Ca2+, all with identical affinities, but in contrast to the model of Arreola et al. (1996), Ca2+ binding per se is voltage independent. Each of the Ca2+-bound closed states can transit in the open state with progressively faster opening rates as the channel binds more calcium ions. In this kinetic scheme, voltage-dependent gating is due to the channel closing rate. Figs. 8 and 9 showed that an adapted version of the Kuruma and Hartzell model effectively simulated the experimentally derived data recorded with AMP-PNP–containing pipette solutions (compare Fig. 8 with Fig. 3). It is interesting to note that in the experiments of both Arreola et al. (1996) and Kuruma and Hartzell (2000), the solution facing the internal side of the membrane did not contain ATP, a situation that would minimize the state of phosphorylation of the channels and mimic our AMP-PNP experiments. Although it is unknown whether ClCa channels in these cells are regulated by phosphorylation in a similar fashion, it has been reported that IClCa in Xenopus oocytes is inactivated by activation of protein kinase C in a Ca2+-dependent manner (Boton et al., 1990). Overall, the model parameters used to simulate IClCa recorded from cells dialyzed with AMP-PNP (see Table I) accounted well for the “apparent” sigmoidal increase in Ca2+ affinity observed with membrane depolarization, the voltage dependence of fully activated IClCa, the basal activation of the underlying channels observed at negative potentials, the Ca2+ dependence of V 0.5 and kinetics of activation, and voltage dependence of deactivation.

To model the data with ATP, we simply increased the magnitude of the “off” (βx in Table I) rate constants and shifted their voltage dependence toward more positive potentials, assigning a value of 0 to the gating variable for the higher Ca2+-bound states, which means that the channels are either closed or blocked by phosphorylation. By analogy, this would correspond to open state channel block by phosphorylation. All other rate constants, including those defining Ca2+ affinity, were identical to those used in the AMP-PNP model (see Table I). Our simulations reproduced quantitatively in most cases, and semi-quantitatively in others, the macroscopic behavior of IClCa that includes potent inhibition of the Cl− channels within the physiological range of membrane potentials, their Ca2+ dependence at all potentials examined, and to a lesser extent their Ca2+ and voltage dependence of activation (except at 250 nM) and deactivation kinetics. Although this was not evaluated, it might have been possible to produce similar results by reducing the gating variable of all open states to a fraction between 0 and 1. This would be similar to the induction of subconductance states by phosphorylation. Indeed, higher levels of [Ca2+] were shown to induce the appearance of subconductance levels of single ClCa channels in rabbit pulmonary myocytes (Piper and Large, 2003), and perhaps phosphorylation of a cytoplasmic domain may cause open state block by an electrostatic interaction with acidic amino acid residues residing within or near the channel pore. By opposition, minimizing phosphorylation with AMP-PNP may “lock” the channels open at negative potentials, especially at higher levels of intracellular Ca2+, resulting in the appearance of very slowly declining tail currents (see Figs. 3 and 9) and large negative shifts in the holding current, leading to attenuation of the normally strong outward rectification. Although the model is undoubtedly overly simplistic, it nevertheless provides a valid framework from which specific hypotheses in regards to the regulation of ClCa channels by phosphorylation can be thoroughly tested under conditions allowing physiological intracellular Ca2+ dynamics. Future single channel experiments will be designed to test the hypothesis that the state of phosphorylation of the channel and/or regulatory subunit(s) alters the properties determining the rate of closure of the gate and perhaps the state of permeation of the channel.

Regulation of IClCa in Pulmonary Artery Myocytes

The data of the present study agree with our past studies (Greenwood et al., 2001, 2004; Ledoux et al., 2003) that the activity of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels in vascular smooth muscle cells is dictated by the phosphorylation status in the vicinity of the channel. Regulation of IClCa has been best studied in arterial myocytes where we have established that CaMKII suppresses activity (Greenwood et al., 2001) whereas calcineurin enhances IClCa (Ledoux et al., 2003; Greenwood et al., 2004). Previously, we showed that blockade of calcineurin in coronary artery myocytes produced a decrease in the Ca2+ sensitivity. However, the present study established that gross dephosphorylation markedly enhanced IClCa due to an increase in the voltage sensitivity and not the Ca2+ sensitivity. While there is the caveat that the studies were not performed in the same cell type, these data suggest that a hyperphosphorylated Cl− channel is less able to bind Ca2+ or is less able to transit to an open configuration upon Ca2+ binding, whereas a fully dephosphorylated channel is more active at less depolarized potentials. The present study also reveals that Cl− channel activity in rabbit pulmonary artery myocytes is highly labile and at the mercy of the opposing kinase/phosphatase activity. Thus, the amplitude of IClCa evoked immediately after membrane rupture was large but decreased to a stabilized level ∼20% of the initial value when the pipette solution was ATP rich. Under these conditions, phosphorylation would be supported, and therefore the current recorded at the stabilized level represents diminished ion flux through a partially phosphorylated channel. The degree of phosphorylation is dynamic and dependent on the kinase/phosphatase balance in the vicinity as described by Greenwood et al. (2004). This supposition is reinforced by the data with AMP-PNP that is unable to support phosphorylation (Yount, 1975; Gadsby and Nairn, 1999) and therefore allows phosphatase activity to dominate. Consequently, the degree of rundown is attenuated and the current stabilizes to a steady-state level close to the initial current amplitude. Whether calcineurin alone or in combination with other phosphatases drives this recovery of IClCa amplitude is the focus of future experiments.

In conclusion, the present study represents an extensive study of the kinetics, Ca2+ dependence, and voltage dependence of whole-cell IClCa in pulmonary artery myocytes. A corollary to this work is that we have been able to effectively simulate the experimental data using a minimal reaction scheme. Moreover, this exhaustive study has revealed a mechanism by which phosphorylation regulates Cl− channel activity and has reinforced the crucial role of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation mechanisms on IClCa.

Supplemental Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Cathy Lachendro for her technical help in isolating rabbit pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells and for preparing solutions.

The work was supported by grants to N. Leblanc from the National Institutes of Health (grant HL 1 R01 HL075477-01A2). Research in the laboratory of I.A. Greenwood was funded by the British Heart Foundation and The Wellcome Trust. This publication was also made possible by grant NCRR 5P20 RR15581 (N. Leblanc) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) supporting a Center of Biomedical Research Excellence at the University of Nevada School of Medicine. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR or NIH.

Olaf S. Andersen served as editor.

Abbreviations used in this article: AMP-PNP, adenosine 5′-(β,γ-imido)-triphosphate; PSS, physiological salt solution.

References

- Arreola, J., J.E. Melvin, and T. Begenisich. 1996. Activation of calcium-dependent chloride channels in rat parotid acinar cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 108:35–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boese, S.H., O. Aziz, N.L. Simmons, and M.A. Gray. 2004. Kinetics and regulation of a Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance in mouse renal inner medullary collecting duct cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 286:F682–F692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boton, R., D. Singer, and N. Dascal. 1990. Inactivation of calcium-activated chloride conductance in Xenopus oocytes−roles of calcium and protein kinase C. Pflugers Arch. 416:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton, F.C., S. Ohya, B. Horowitz, and I.A. Greenwood. 2002. Comparison of the properties of CLCA1 generated currents and ICl(Ca) in murine portal vein smooth muscle cells. J. Physiol. 539:107–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipperfield, A.R., and A.A. Harper. 2000. Chloride in smooth muscle. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 74:175–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J., D.H. Cox, and R.W. Aldrich. 1997. Intrinsic voltage dependence and Ca2+ regulation of mslo large conductance Ca-activated K+ channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 109:647–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, M.G., and A. Marty. 1986. Calcium-dependent chloride currents in isolated cells from rat lacrimal glands. J. Physiol. 378:437–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frings, S., D. Reuter, and S.J. Kleene. 2000. Neuronal Ca2+-activated Cl− channels−homing in on an elusive channel species. Prog. Neurobiol. 60:247–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby, D.C., and A.C. Nairn. 1999. Control of CFTR channel gating by phosphorylation and nucleotide hydrolysis. Physiol. Rev. 79:S77–S107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, I., J. Ledoux, and N. Leblanc. 2001. Differential regulation of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in rabbit arterial and portal vein smooth muscle cells by Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent kinase. J. Physiol. 534:395–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, I.A., J. Ledoux, A. Sanguinetti, B.A. Perrino, and N. Leblanc. 2004. Calcineurin Aα but not Aβ augments ICl(Ca) in rabbit pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279:38830–38837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell, C., I. Putzier, and J. Arreola. 2005. Calcium-activated chloride channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 67:719–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, T., and D.I. Cook. 1993. A Ca2+-activated Cl− current in sheep parotid secretory cells. J. Membr. Biol. 135:261–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuruma, A., and H.C. Hartzell. 2000. Bimodal control of a Ca2+-activated Cl− channel by different Ca2+ signals. J. Gen. Physiol. 115:59–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large, W.A., and Q. Wang. 1996. Characteristics and physiological role of the Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance in smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 271:C435–C454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc, N., J. Ledoux, S. Saleh, A. Sanguinetti, J. Angermann, K. O'Driscoll, F. Britton, B.A. Perrino, and I.A. Greenwood. 2005. Regulation of calcium-activated chloride channels in smooth muscle cells: a complex picture is emerging. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 83:541–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledoux, J., I. Greenwood, L.R. Villeneuve, and N. Leblanc. 2003. Modulation of Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels by calcineurin in rabbit coronary arterial myocytes. J. Physiol. 552:701–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledoux, J., I.A. Greenwood, and N. Leblanc. 2005. Dynamics of Ca2+-dependent Cl− channel modulation by niflumic acid in rabbit coronary arterial myocytes. Mol. Pharmacol. 67:163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin, D., L.W. Jiang, G.R. Strohmeier, A. Nusrat, S.L. Alper, W.I. Lencer, and J.L. Madara. 1998. Distinct Ca2+- and cAMP-dependent anion conductances in the apical membrane of polarized T84 cells. Am. J. Physiol. 275:C484–C495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius, B., J. Prenen, T. Voets, K. Van Den Bremt, J. Eggermont, and G. Droogmans. 1997. Kinetic and pharmacological properties of the calcium-activated chloride current in macrovascular endothelial cells. Cell Calcium. 22:53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper, A.S., and I.A. Greenwood. 2003. Anomalous effect of anthracene-9-carboxylic acid on calcium-activated chloride currents in rabbit pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 138:31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper, A.S., I.A. Greenwood, and W.A. Large. 2002. Dual effect of blocking agents on Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in rabbit pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J. Physiol. 539:119–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper, A.S., and W.A. Large. 2003. Multiple conductance states of single Ca2+-activated Cl− channels in rabbit pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J. Physiol. 547:181–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Z., R.W. Wei, and H.C. Hartzell. 2003. Characterization of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in mouse kidney inner medullary collecting duct cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 285:F326–F335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remillard, C.V., and N. Leblanc. 1996. Mechanism of inhibition of delayed rectifier K+ current by 4-aminopyridine in rabbit coronary myocytes. J. Physiol. 491:383–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.X., and M.I. Kotlikoff. 1997. Inactivation of calcium-activated chloride channels in smooth muscle by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:14918–14923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W., M.A. Kaetzel, K.S. Bruzik, J.R. Dedman, S.B. Shears, and D.J. Nelson. 1996. Inositol 3,4,5,6-tetrakisphosphate inhibits the calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-activated chloride conductance in T84 colonic epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271:14092–14097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.W., K.R.H. Solomons, S. Freeman, M.A. Kaetzel, K.S. Bruzik, D.J. Nelson, and S.B. Shears. 1998. Regulation of Ca2+-dependent Cl− conductance in a human colonic epithelial cell line (T84): cross-talk between Ins(3,4,5,6)P4 and protein phosphatases. J. Physiol. 510:661–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yount, R.G. 1975. ATP analogs. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 43:1–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZhuGe, R., K.E. Fogarty, R.A. Tuft, and J.V. Walsh. 2002. Spontaneous transient outward currents arise from microdomains where BK channels are exposed to a mean Ca2+ concentration on the order of 10 μM during a Ca2+ spark. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:15–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.