Abstract

Adjustment of the Na/K ATPase activity to changes in oxygen availability is a matter of survival for neuronal cells. We have used freshly isolated rat cerebellar granule cells to study oxygen sensitivity of the Na/K ATPase function. Along with transport and hydrolytic activity of the enzyme we have monitored alterations in free radical production, cellular reduced glutathione, and ATP levels. Both active K+ influx and ouabain-sensitive inorganic phosphate production were maximal within the physiological pO2 range of 3–5 kPa. Transport and hydrolytic activity of the Na/K ATPase was equally suppressed under hypoxic and hyperoxic conditions. The ATPase response to changes in oxygenation was isoform specific and limited to the α1-containing isozyme whereas α2/3-containing isozymes were oxygen insensitive. Rapid activation of the enzyme within a narrow window of oxygen concentrations did not correlate with alterations in the cellular ATP content or substantial shifts in redox potential but was completely abolished when NO production by the cells was blocked by l-NAME. Taken together our observations suggest that NO and its derivatives are involved in maintenance of high Na/K ATPase activity under physiological conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Maintenance of the transmembrane ionic gradients by the Na/K ATPase is a prerequisite for neuronal activity and survival. High susceptibility of the brain to oxygen shortage is largely linked to a rapid suppression of the Na/K ATPase activity in neuronal cells. Initially it has been suggested that reduction in the ATPase activity is secondary to the ATP depletion caused by suppression of oxidative phosphorylation (Erecinska and Silver, 2001). Although this is obviously the case for extreme conditions such as warm ischemia or severe hypoxia, previous studies including our own suggest that hypoxia-induced suppression of the Na/K ATPase function in different cell types is not necessarily linked to ATP deprivation (Buck and Hochachka, 1993; Bogdanova et al., 2003; Nilsson and Lutz, 2004; Bogdanova et al., 2005; Jain and Sznajder, 2005).

Mechanisms of the intrinsic oxygen sensitivity of the Na/K ATPase in neurons remain unknown. Corresponding studies in other cell types suggest that acute responses are mediated by the alterations in free radical production and cellular redox state is responsive to changes in environmental oxygen (Dada et al., 2003; Litvan et al., 2006). However, lessons obtained from the other cell types cannot be translated to neurons since the corresponding signal transduction pathways were shown to be highly tissue and species specific (Bogdanova et al., 2006). Na/K ATPase in various cells has been reported to use several strategies for acute response to deoxygenation (hypoxia or brief ischemia), including changes in the phosphorylation state of α or γ subunits that may lead to reversible internalization of the enzyme in clathrin-coated vesicles (e.g., Dada et al., 2003; Fuller et al., 2004). Changes in expression of different isoforms of the α and β subunits of the Na/K ATPase are reported in response to the long-term oxygen shortage (Ostadal et al., 2003).

The goal of the present study was to determine physiologically optimal pO2 range for Na/K ATPase activity in cerebellar granule cells, and to characterize the mechanism by which cerebellar granule cell Na/K ATPase responds to hypoxia and hyperoxia with specific regard to the contributions of oxygen-derived free radicals and nitric oxide.

Our observations suggest that both transport and hydrolytic activity of the Na/K ATPase are highly dependent on oxygen concentration and that NO production plays a key role in oxygen-driven control over the ATPase function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

As a model we used freshly isolated dispersed cerebellar granule cells from neonatal rats. As we have shown earlier, neurons comprise the majority of the cellular population (∼70%) (Petrushanko et al., 2006). When in suspension these cells retain their native properties for several hours after isolation. Suspending the cells allows precise control of oxygen availability in contrast to brain slices in which gradients for oxygen are formed.

In Vivo Cerebellar Oxygen Concentrations

Oxygen concentration in the cerebellum was measured using Oxylite 2000 (Oxford Optronix Ltd.). Before the measurements were performed, the oxygen sensor probe was tested using water equilibrated with gas phase containing 1, 3, 5, 10, and 20% O2. Wistar rats of the age of P3, P7, P9–13 as well as adult male rats of 300–330 g remained under deep anesthesia (Nembutal, 50–100 μl [50 mg/ml] intraperitoneal injection) during the measurements. Breathing pattern was monitored as an indicator of the animal's condition. An optical oxygen sensor was introduced into the cerebellum (depth 1–3 mm depending on the age) intracranially within a metal needle holder provided by Oxford Optronix. After measuring, the probe was removed, the animals were immediately decapitated and the skull opened. Location of the probe within the cerebellum was confirmed post mortem.

Rat Cerebellar Granule Cell Model

Cerebellar granule cells were isolated from the Wistar rat pups of postnatal days 9–10 (P9–P10) as described earlier (Petrushanko et al., 2006). In brief, cerebella of six to nine animals were excised after decapitation, and then minced and digested with 200 U/ml of Worthington type 4 collagenase. After isolation, cells were suspended at a density of 1–2 × 106 cells/ml in Tyrode medium (containing 120 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.4 at 37°C) supplemented with 0.25% vol/vol FBS and incubated for 30 min at 37°C in the cell culture incubator (air + 5% CO2). The cells were used for experiments within 2–3 h after isolation.

Cell Death

A propidium iodide (PI) assay was used to assess viability of the cells in suspension at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. Viability of cells used for determination of ATP, GSH, and activity of the Na/K ATPase was assessed using trypan blue staining.

Cellular Reduced (GSH) and Oxidized (GSSG) Glutathione Levels

Cellular GSH and GSSG concentrations were determined using Ellmann's reagent as described elsewhere (Tietze, 1969). In brief, after incubation for 7, 30, or 60 min at various fixed pO2 values, cell suspensions were mixed with equal volume of 5% TCA and lysates were centrifuged to pellet denatured proteins. Nonprotein thiol levels in the supernatant were determined by adding Ellmann's reagent (5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid)) and assessing optical density (412 nm; Lambda 25 spectrophotometer, Perkin-Elmer). To quantify GSSG content the second aliquot of the supernatant was incubated with 50 μM β-NADH-Na2 and 0.1 mg/ml of glutathione reductase type II (20 min, room temperature), and then reduced thiol levels were detected as described above. GSSG content was then calculated as the difference between the thiol levels after and before GSSG reduction.

Free Radical Production as a Function of pO2

2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA) was used to monitor the generation of free radicals in cerebellar granule cells exposed to various oxygen concentrations. The dye accumulates in the cytosol of cells after de-esterification and is oxidized by *OH, by H2O2 in the presence of Fe2+ or active peroxidases and by ONOO− but not by *O2 − (LeBel et al., 1992; Royall and Ischiropoulos, 1993; Kooy et al., 1997). Cells were preloaded with 100 μM H2DCF-DA for 30 min. Suspended cerebellar granule cells were exposed for 60 min (samples were collected every 10 min), at various fixed pO2.

Generation of ONOO−, N2O3, NO2 −, and NO3 − at Various pO2

The rate of ONOO− production was determined as a difference in oxidation of the H2-DCF in the cells preincubated for 15 min with or without 100 μM methyl ester of N ω-nitro-l-arginine (l-NAME), a nonselective inhibitor of NO synthases (NOS). After pretreatment with l-NAME, the cells were loaded with 100 μM H2DCF-DA for 30 min and thereafter exposed to various pO2 for 15 or 60 min. Note that l-NAME was present in the medium also during incubation at different pO2.

Another fluorescent dye, 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′- difluorofluorescein diacetate (DAF-FM DA), was used to monitor the products of NO auto-oxidation (N2O3) at 15 and 30 min of various fixed pO2. The cells were loaded with DAF-FM DA (final concentration 5 μM) 1 h before exposure to different oxygen concentrations. Similar to H2-DCF-DA, DAF-FM DA is cleaved by esterases forming membrane-impermeable DAF-FM upon entering the cytosol. Cytosolic DAF-FM becomes fluorescent upon interaction with N2O3 as it forms a benzotriazole derivative (Balcerczyk et al., 2005). Of note, NO detection by DAF-FM is oxygen sensitive as the dye interacts with NO only after being transferred into N2O3. However, oxygen demand is modest and NO detection with DAF-FM was reported as successful even under virtually anoxic conditions (Kojima et al., 2001). Fluorescence was monitored by means of flow cytometry (FacsCalibur, Bekton Dickenson). Populations of cells for flow cytometry were chosen as described earlier (Petrushanko et al., 2006). Debris from destroyed cells and dead (PI positive described above) cells were excluded from the analysis.

Nitrite and Nitrate Production as a Function of pO2

Nitrite and nitrate levels were assessed in cerebellar granule cell suspensions using a chemiluminescence detection technique, previously described (Rassaf et al., 2004). In brief, after cells were incubated for 60 min at various fixed pO2, aliquots of cell suspensions were collected for NO2 − and NO3 − determination. Nitrite concentration was measured directly in cell suspensions by injecting 50 μl into a helium-gassed Brown's solution (1.62 g KJ and 0.57 g J2 in 200 ml CH3COOH) at 60°C, and NO formed from NO2 − was analyzed using a CLD 88 (Eco Medics). Nitrate was reduced to nitrite (Nitrate Reductor Kit, World Precision Instruments, Inc.) before the chemiluminescent analysis of NO levels derived from NO2 −. NO measured from the first sample of endogenous nitrite was subtracted from the second sample in which nitrate was reduced before NO measurement and the difference was shown as total nitrate concentration.

Cellular ATP Levels

After 7, 30, and 60 min at fixed pO2, cerebral granule cell ATP levels were detected in the protein-free supernatant using an ATP bioluminescence kit based on the luciferin–luciferase assay (FLAA-1kt, Sigma-Aldrich). Sample preparation was similar to that for GSH measurements. After deproteinization with 5% TCA, proteins were removed by centrifugation (10,000 g for 15 min at 4°C). The supernatant was buffered with Tris-OH (50 μl) and mixed with ATP assay mix (50 μl), and the chemiluminescence signal was immediately recorded (Sirius Luminometer V2.2, Berthold Detection Systems). The calibration curve covered from 10−10 to 10−7 M ATP.

Na/K ATPase Transport Activity: Unidirectional Active K+ Influx

The methods used for detection of the transport and hydrolytic activity of the Na/K ATPase were conducted as previously published (Petrushanko et al., 2006). In brief, suspensions of cerebellar granule cells were allowed to equilibrate for 2 min to reach a given pO2, and then incubated for 7, 30, and 60 in self-constructed tonometers. The Na/K ATPase-mediated (active) component of unidirectional K+ influx was measured as ouabain-sensitive K+(86Rb+) uptake, by adding the radioactive tracer to cell suspensions and collecting samples at 3, 5, and 10 min. K+ flux was stopped immediately by mixing samples with a 10-fold higher volume of ice-cold washing medium (100 mM Mg(NO3)2 and 10 mM imidazol-HNO3, pH to 7.4 on ice). After triple washing steps, the cell pellet was lysed with 5% TCA and 86Rb+ accumulation in the cells detected in water phase (Cherenkov effect) with a liquid scintillation counter (Tri-Carb 1600TR, Packard). When the role of NO in oxygen-induced regulation of the active K+ influx was studied the cells were preincubated in the presence or in the absence of 100 μM l-NAME for 15 min at pO2 of 20 kPa before adjustment of the oxygen level in the medium to 1, 3, or 10 kPa.

Na/K ATPase Hydrolytic Activity: Oxygen and NO Dependence and Isoform Specificity

Hydrolytic Na/K ATPase activity was determined in cells exposed for 30 min at various fixed pO2. Na/K ATPase hydrolytic activity was assayed in cell lysates and microsomal fractions, as previously described (Rathbun and Betlach, 1969). In brief, in order to obtain ouabain-permeable microsomes, cells were subjected to repetitive freeze–thaw cycles.

The obtained lysates containing ouabain-permeable microsomes were incubated in the medium containing 130 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl, and 3 mM MgCl2 with or without 1 mM ouabain (37°C, 10 min) before the actual measurements of the ATP cleavage rate. After pretreatment with ouabain, ATPase activity measurements were initiated by adding ATP-HEPES-NaOH mixture (final concentrations in the medium 3 mM and 30 mM, respectively). After the reaction was stopped with 1:1 dilution by ice-cold stopping solution (4% formaldehyde in 1.3 M sodium acetate buffered with acetic acid to pH 4.3), probes were supplied with 100 μl of SnCl2 solution (15 mg SnCl2 in 5 ml 0.002% acetic acid) and 100 μl of 2% (NH4)2MoO4 solution in distilled water. In 15 min, a colored complex of phosphate with tin and molebdate was formed and evaluated by measuring optical density (660 nm, Lambda 25 spectrophotometer, Perkin Elmer). Blank samples contained no cell lysates or the lysates were added after the ATP hydrolysis reaction was stopped. Hydrolytic activity of Na/K ATPase was calculated as a difference in phosphate production rates in samples with and without ouabain. Activities were normalized to the protein content. Protein concentration was determined using a modified Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

To characterize the role of NO and reactive nitrogen species in oxygen sensitivity of the Na/K ATPase hydrolytic activity, the cells were exposed to various oxygen concentrations in the presence or in the absence of 100 μM of l-NAME. Thereafter the cells were processed as described above to evaluate the hydrolytic activity of the ATPase. l-NAME was not present in the medium during detection of the rate of ouabain-sensitive ATP hydrolysis.

Isoform specificity of oxygen-induced regulation of the Na/K ATPase was monitored using ouabain titration assay. To discriminate between α1 with low affinity to ouabain and α2/α3 isoforms having significantly higher affinity to the inhibitor, ouabain-permeable microsomes were treated with varying ouabain concentrations; 10−3 mol/liter, 10−4 mol/liter, 5 × 10−5 mol/liter, 5 × 10−6 mol/liter, 10−6 mol/liter, 10−7 mol/liter, 10−8 mol/liter, and in the absence of ouabain, and samples analyzed for ATPase hydrolytic activity as described above. ATP cleavage rates were plotted against ouabain concentrations and specific activities of the α1 and α2–3 isoforms calculated from these graphs (see Fig. S1, available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200709783/DC1). Details of the analysis are presented in the Online Supplemental Material section.

Statistics

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using GraphPad Instat program (version 3, GraphPad InStat). After a normality test was performed, comparisons of the groups of data were done using paired or nonpaired Student's t test based on the two-tailed Anova. Origin 7.0 (Microcal Software, Inc.) was used to fit the data on oxygen sensitivity of different isoforms of the Na/K ATPase.

Online Supplemental Material

Fig. S1 (available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200709783/DC1) shows curves obtained by plotting the rates of ATP cleavage against ouabain concentrations and analyzing them to estimate the pseudomaximal activity of α1 and α3-α3 isozymes.

RESULTS

Viability of Cerebellar Granule Cells in Suspension as a Function of pO2

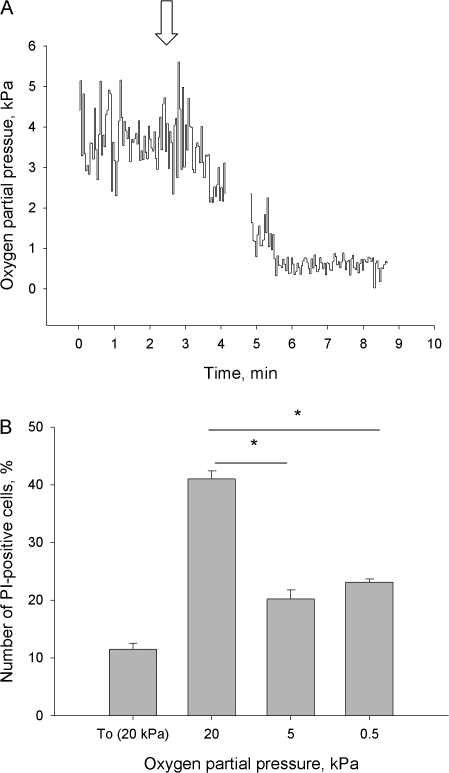

Oxygen partial pressure was monitored in vivo in cerebellum of rat pups aged P3–P13 and in adults. Oxygen levels remained as low as 0.5–1.3 kPa at the early stages of postnatal development (P3–P10). At the age of P12–P13, pO2 in cerebellum increased to 3.3–4 kPa, reaching maximal levels in adult animals 5.3–6 kPa. Oxygen partial pressure measured in the brain of anaesthetized animals was lower than that expected in the conscious rats because Nembutal is known to suppress breathing (Buelke-Sam et al., 1978). Based on the obtained data, pO2 of 3–5 kPa was chosen as a window of physiological normoxia, 0.5 kPa was defined as hypoxia and 10–20 kPa as mild to severe hyperoxic conditions. From day P12 forward, pO2 in the brain was vulnerable to the interruption of blood supply. Spontaneous cessation of breathing at this age observed in a single experiment was followed by an immediate decrease in cerebellar pO2 from a mean of 3.6 to 0.12 kPa (Fig. 1 A).

Figure 1.

(A) Original trace of oxygen concentration recording in cerebellum of 12 d postnatal rat using Oxylite 4000 (Oxford Optronix). Arrow shows the moment of cessation of breathing. (B) The amount of dead (propidium iodide–positive) cells at the beginning of experiment (To) and after 60 min of incubation at pO2 of 20, 5, or 0.5 kPa assayed by flow cytometry. The age of the animals varied from P10 to P12. Data are means of five independent experiments ± SEM. * denotes P < 0.05 between the selected values.

Cell Death with Increasing pO2

In accordance with the idea that 20 kPa is hyperoxic to cerebellar granule cells, the greatest cell death was noted after 60 min of incubation at 20 kPa, in comparison to 0.5 and 5 kPa. (Fig. 1 B). The high pO2 most likely accelerated cell death by progressive oxidative damage. To test this hypothesis we measured cellular bulk GSH and GSSG levels as well as the rate of free radical formation in the cells as a function of oxygen concentration in the medium.

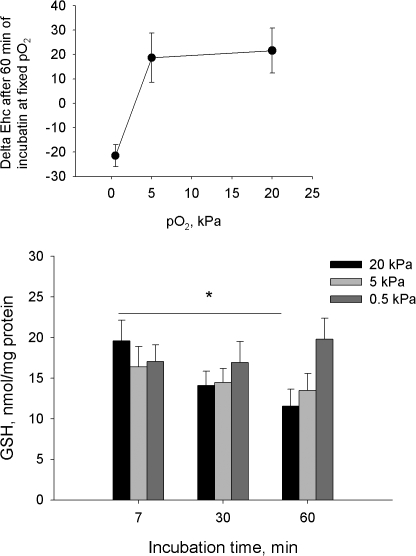

Intracellular GSH Content as a Function of pO2

As expected, exposure of cerebellar granule cells to pO2 of 20 kPa resulted in a gradual depletion of the cellular GSH stores (Fig. 2). In contrast, GSH content of cerebellar granule cells exposed to 0.5 kPa remained unchanged. Levels of cellular GSH alone are not particularly reliable as a marker of the modest changes in redox state since GSSG usually comprises several percent of the bulk GSH pool. Thus, doubling of GSSG content does not cause any significant shifts in the GSH levels. Therefore, based on the measurements of cellular GSH and GSSG content we have calculated half-cell reduction potential (Ehc) for GSH/GSSG couple, which is considered an adequate indicator of the changes in cellular redox state (see Schafer and Buettner, 2001, and figure legend for more details). The Ehc values for the granule cells incubated for 60 min at pO2 of 20 kPa shifted from −222.4 ± 1.15 mV to −200.8 ± 8.1 mV, with the corresponding values of 5 and 0.5 kPa being −203.7 ± 9.0 mV and −243.9 ± 3.3 mV. This means that the bulk redox state did not differ for cells incubated at 20 and 5 kPa, whereas at 0.5 kPa the latter was shifted toward more reduced state. Notably, as could be seen from the inset of Fig. 2, a steep change in redox potential occurred as oxygen partial pressure in the incubation medium decreased from 5 to 0.5 kPa. Interestingly, incubation of the cells at pO2 of 20-5 kPa was followed by gradual oxidation whereas at low oxygen concentration redox equilibrium was becoming more reduced. No changes in the cellular redox state over time occurred at pO2 of ∼3 kPa, supporting the in vivo data on the physiological window of pO2 in the rat cerebellum (Fig. 1 A).

Figure 2.

Reduced glutathione levels in cells incubated for 7, 30, or 60 min at pO2 of 20, 5, or 0.5. Data are means of five independent experiments ± SEM. * denotes P < 0.05 compared with the level at 20 kPa after 7 min of incubation. Inset represents the changes in GSH:GSSG half-reduction potential Ehc in cells exposed to pO2 of 20, 5, or 0.5 kPa for 60 min. Ehc was calculated using the following equation (for details see Schafer and Buettner, 2001): Ehc = −240 – (59.55/2)*log([GSH]/[GSSG]) for the T 25°C, pH 7.0.

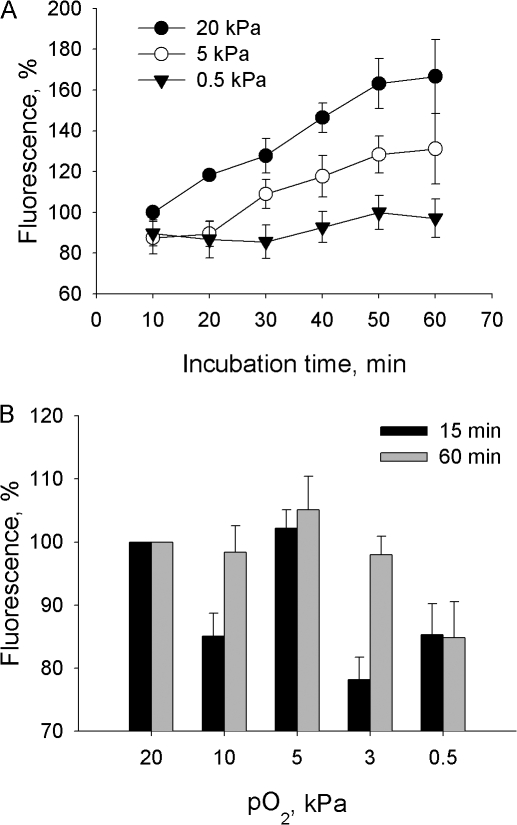

Free radical production as a function of pO2

The changes in cellular GSH content and redox potential usually reflect alterations in free radical production. As can be seen from Fig. 3, the rate of free radical formation monitored using fluorescent dye H2-DCF indeed depended on the oxygen concentration in the incubation medium. Because H2-DCF may be oxidized by several radical species in the cytosol including hydroxyl radicals, ONOO− and H2O2 (when peroxidases or Fe2+ are available to catalyze the oxidation reaction), we performed additional experiments to monitor oxygen-dependent formation of each radical species. Of special interest were the pO2 of 3 and 10 kPa where a marked increase in H2-DCF oxidation was observed when incubating the cells for 60 min (Fig. 3 B). Oxygen dependence of hydrogen radical production was evaluated as a difference in H2-DCF oxidation in the presence and in the absence of the selective *OH scavenger mercaptopropionyl glycine (MPG). Interestingly, MPG treatment had no effect on H2-DCF oxidation rate at any pO2 tested (unpublished data). This suggested that whenever formed, this radical species remained below the detection limit of our analytical method.

Figure 3.

(A) The rate of H2-DCF oxidation in cerebellar granule cells incubated at pO2 of 20, 5, or 0.5 kPa over 60 min detected by means of flow cytometry. Data are means of five independent experiments ± SEM normalized to the fluorescent signal immediately after loading. (B) Oxygen dose dependence of H2-DCF oxidation after 15 and 60 min of incubation at fixed pO2. Data are means of six independent experiments ± SEM normalized to the fluorescent intensity at the onset of incubation at fixed pO2 following 30 min of preincubation of cells loaded with fluorescent dye at pO2 of 20 kPa.

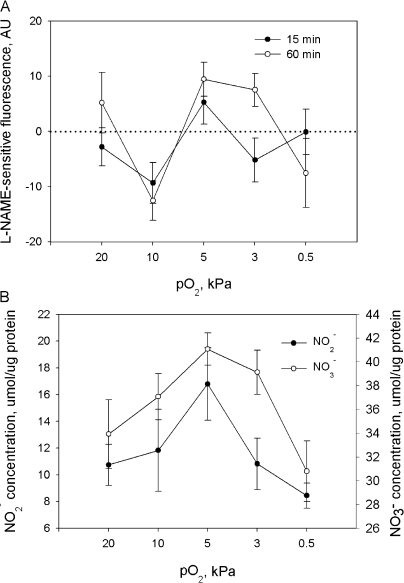

Treatment of cells with the nonselective inhibitor of nitric oxide synthases (NOS) N ω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (l-NAME) before and during the exposure of cells to various pO2 revealed that ONOO− contributed to the oxidation of the fluorescent dye and this contribution was oxygen dependent (Fig. 4 A). The highest rates of ONOO− production were observed at a pO2 of 5 kPa already after 15 min of exposure of cerebellar granule cells to fixed pO2. Of note is potentiation of ONOO− production during prolonged incubation at 3 kPa. Thus, the observed up-regulation in oxidation of the H2-DCF at pO2 of 3–5 kPa (see Fig. 3) is most likely attributed to the increase in production of ONOO−.

Figure 4.

(A) l-NAME–sensitive component of H2-DCF oxidation after 15 or 60 min of incubation at fixed pO2 measured by means of flow cytometry. Data are means of five independent experiments ± SEM. (B) Nitrite and nitrate production by cerebellar granule cells detected in cell suspension after 60 min of incubation at fixed pO2 using chemiluminiscence techniques. Data are means of six independent experiments ± SEM.

Reliable detection of nitric oxide production in living cells is technically demanding due to its short half-life. Therefore, we focused on characterization of the oxygen dependence of generation of the secondary NO metabolites such as N2O3, NO2 −, and NO3 −. The levels N2O3 were very low and barely detectible with a fluorescent dye DAF-FM after 15 min of incubation. Maximal fluorescent intensity for this dye was obtained after 60 min of incubation at 3 kPa (unpublished data). The oxygen dependence of formation of the end products of NO oxidation, NO2 − and NO3 −, is shown in Fig. 4 B. In agreement with data on the oxygen dependence of ONOO− and N2O3 production we obtained using H2-DCF and DAF-FM, nitrite levels after 60 min incubation at fixed pO2 were maximal at pO2 of 3 kPa (unpublished data). Maximum of nitrate production corresponded to 3–5 kPa (Fig. 4 B). A striking difference between NO2 − and NO3 − levels at pO2 of 3 kPa suggests that most of the NO2 − produced in cells at this oxygen partial pressure was rapidly oxidized to NO3 − (Fig. 4 B).

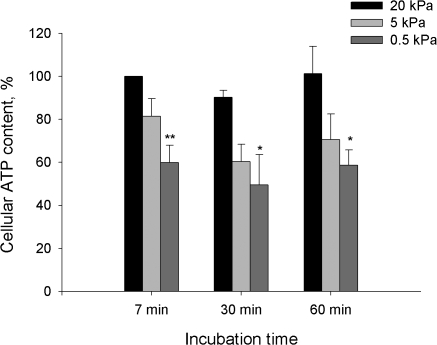

ATP Concentrations in Cerebellar Granule Cells Exposed to Various Oxygen Concentrations

Next set of experiments was performed to assess the impact of deoxygenation and oxidative stress on the ATP content of cerebellar granule cells. Fig. 5 shows the kinetics of the O2-induced changes in the bulk cellular ATP for 0.5, 5, and 20 kPa. Exposure of cerebellar granule cells to hypoxia (pO2 0.5 kPa) resulted in a rapid ATP depletion with no recovery over the 60 min of treatment. Incubation of the cells under hyperoxic (pO2 20 kPa) of normoxic (pO2 5 kPa) conditions for 60 min did not affect the cellular ATP content.

Figure 5.

Cellular ATP levels as a function of oxygen concentration. Data are means of 6–9 experiments ± SEM. ** denotes P < 0.01 and * denotes P < 0.05 compared with the levels at 7 min for pO2 of 20 kPa.

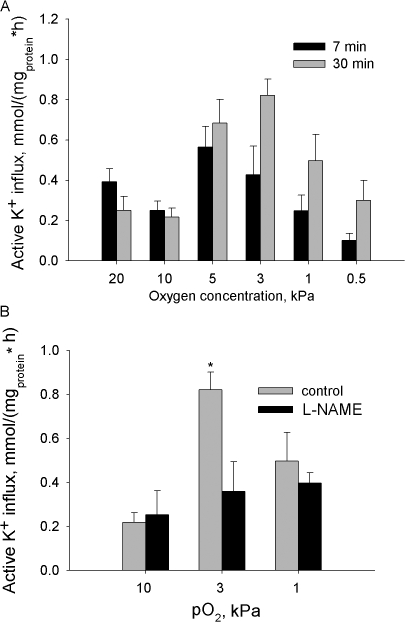

Transport Activity of the Na/K ATPase as a Function of pO2

Both changes in the free radical production and cellular ATP levels are known to affect the Na/K ATPase function. In the next set of experiments oxygen dependence of the transport and hydrolytic activity of this enzyme in cerebellar granule cells was determined. Oxygen sensitivity of unidirectional ouabain-sensitive K+ influx into the cerebellar granule cells is illustrated in Fig. 6 A. Oxygen-induced response of the ATPase could be observed as early as 7 min after the incubation of the cells at fixed pO2 and persisted over 60 min of treatment. Active K+ influx was up-regulated at physiologically normoxic pO2 levels whereas under hypoxic and hyperoxic conditions the activity of the Na/K ATPase in cerebellar granule cells remained low. Oxygen partial pressures at which maximal activity of the Na/K ATPase was observed ranged between 5 kPa for short-term incubation to 3 kPa for prolonged treatment (Fig. 6 A). Furthermore, maximal activity of the ATPase was observed under conditions favoring H2-DCF oxidation and NO production (compare Fig. 3 A, Fig. 4, and Fig. 6 A). To evaluate the role of hydroxyl radicals and reactive nitrogen species in the observed modulation of the transport function of the ATPase, the experiments were repeated in the presence of MPG or l-NAME. MPG did not affect active K+ influx into the cerebellar granule cells at any of the oxygen concentrations tested, as it did not affect free radical levels (unpublished data). Pretreatment with l-NAME abolished the up-regulation of active K+ transport at a pO2 of 3 kPa (Fig. 6 B).

Figure 6.

(A) Unidirectional active K+ influx into the cerebellar granule cells as a function of oxygen concentration. Data are means of 6–8 independent experiments ± SEM. (B) Effect of inhibition of NO synthases on oxygen-induced regulation of the active K+ influx in cells incubated for 30 min at pO2 of 10, 3, or 1 kPa. Data are means of five independent experiments ± SEM.

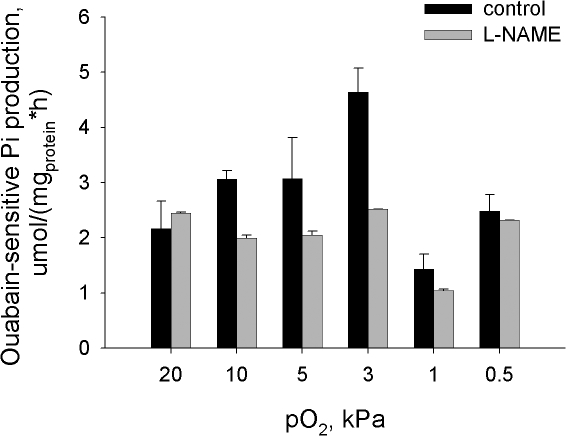

Hydrolytic Activity of the Na/K ATPase in Cells and Microsomes Exposed to Various Oxygen Concentrations

Transport activity of the Na/K ATPase depends on numerous factors including intracellular ATP and Na+ concentrations and the changes in phosphorylation state and interaction between the ATPase subunits. Specific hydrolytic activity of the Na/K ATPase was measured in the destroyed cells in the presence of optimal amounts of the substrate (ATP) and ligands (Na+, K+, and Mg2+) to obtain information on changes in the state of the enzyme itself. Presented in Fig. 7 are the values of ouabain-sensitive ATP cleavage rate in the membranes prepared from intact cells after they were incubated at various pO2. The pattern of oxygen dependence was similar for the hydrolytic and transport activities of the Na/K ATPase. Maximal hydrolytic activity was recorded for the cells incubated at pO2 of 3 kPa for 30 min (Fig. 7) or at 5 kPa for 15 min (not depicted). Oxygen-induced activation of Na/K ATPase hydrolytic activity in cells incubated at a pO2 of 3 kPa was abolished by pretreatment of cells with l-NAME (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Oxygen dependence of the Na/K ATPase hydrolytic activity in cerebellar granule cells incubated at fixed oxygen concentrations for 30 min in the presence or in the absence of 100 μmol of l-NAME. Data are means of six independent experiments ± SEM.

Ouabain titration curves (10−8–10−3 M ouabain) were obtained for lysates of cells exposed to various pO2. Analysis of these curves allowed discrimination between oxygen-induced responses of low-affinity (α1) and high-affinity (α2/3) isoforms of the Na/K ATPase (see Fig. S1). Results of this analysis are presented in Table I. Changes in oxygenation did not affect the affinities of either α1 or α2/3 isozymes to ouabain expressed as inhibition constants I50. However, up- regulation in hydrolytic activity of the Na/K ATPase in the physiological oxygen concentration range could only be observed for the α1 isoform. α2/3 isoforms did not show the pattern of oxygen sensitivity observed for the transport and total hydrolytic activity of the Na/K ATPase.

TABLE I.

Oxygen Dependence of I50 and Vmax for the α1 and α2/3 Isoforms

| I50, M

|

Vmax, μmol Pi/(mgprotein*h)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pO2, kPa | α1 | α2–α3 | α1 | α2–α3 |

| 20 | 5.3−5 ± 2.4*10−5 | 1.8*10−7 ± 1.4*10−7 | 2.17 ± 0.46 | 2.75 ± 0.48 |

| 10 | 3.0*10−5 ± 1.6*10−5 | 2.2*10−7 ± 4.9*10−7 | 2.78 ± 0.89 | 1.93 ± 0.91 |

| 5 | 7.2*10−5 ± 5.8*10−5 | 1.6*10−7 ± 2.9*10−7 | 2.98 ± 0.80 | 2.63 ± 0.93 |

| 3 | 3.0 *10−5 ± 0.8*10−5 | 1.7*10−7 ± 1.7*10−7 | 3.70 ± 0.50 | 2.97 ± 0.57 |

| 0.5 | 10.6*10−5 ± 15.4*10−5 | 7.8*10−7 ± 9.9*10−7 | 2.31 ± 1.21 | 3.36 ± 1.22 |

I50 is the ouabain concentration, which produced 50% of the inhibition; Vmax stands for specific activity of a given isoform of the Na/K ATPase. Shown are the data obtained from the fitting of the curve of means of seven independent experiments ± SEM obtained during approximation with each point weighted according to its standard deviation when computing chi-square during the iterative procedure. The equation used for approximation is a sum of two logistic sigmoid functions (for details see Cortes et al., 2001; Palasis et al., 1996): V = Vα1 + Vα2/3; Vi = [(Vmax − Vmin)/(1 + ([X] /I50)n) + Vmin ], where V is the hydrolytic activity, Vmax/min are maximal and minimal rates of Pi production, [X] is a concentration of ouabain, and I50 is a concentration of ouabain causing a 50% inhibition of the Na/K ATPase. Fitting was based on the assumption the Hill coefficient n = 1, Vmin = 0, and performed using Origin 7.0 software (Microcal Software, Inc.).

DISCUSSION

Data indicate that transport as well as hydrolytic activity of the Na/K ATPase in cerebellar granule cells is maximal within the physiologically normoxic window of pO2 in the neonatal rat cerebellum: 3–5 kPa. Inhibition of NO production by treatment of the cells with nonselective NOS inhibitor l-NAME makes the Na/K ATPase oxygen insensitive. This very important observation suggests that NOS's function most likely as primary oxygen sensors in oxygen-induced regulation of the Na/K ATPase function. To understand how oxygen may influence the Na/K ATPase activity via NO-dependent pathway one has to dissect the links between oxygen availability and NO production and in which form NO or products of its metabolism may affect the ATPase function. Thereafter, the targets of NO action have to be revealed. Finally, the possible impact of the O2/NO-induced regulation of the ATPase on the survival of neurons under hypoxic/hyperoxic conditions needs to be addressed.

NOS as a Putative Oxygen Sensor

Oxygen availability influences NO production directly since O2 along with l-arginine is a cosubstrate for NO production. Alternatively, reactive oxygen species produced from O2 are known to affect NO bio-availability as *O2 − and *OH catalyze NO oxidation. According to our data, ONOO− and NO2 − production reflecting NOS activity in cerebellar granule cells peaks at pO2 of 3–5 kPa. Affinity of all NOS isoforms in the brain to O2 is rather low (Km 23–35 kPa; Erecinska and Silver, 2001), suggesting that reduction in oxygenation would suppress NO production within physiologically relevant range of oxygen concentrations. At high oxygen concentrations l-arginine availability is a rate-limiting factor in control of NO production. Hyperoxia turns NOS from NO generators into *O2 − generators in different tissues including, e.g., kidney medulla (Beltowski et al., 2004). Our data reveal that this is the case also in cerebellar granule cells where up-regulation in l-NAME–sensitive H2-DCF oxidation at 20 kPa is not followed by an increase in NO2 − and NO3 − production (Fig. 4, A and B). Thus, activation of NOS may cause up-regulation of Na/K ATPase activity only when optimal ratio between O2 and l-arginine availability is maintained for NO generation, namely under conditions of physiological normoxia.

Signal Transduction Mechanisms Involved in O2/NO-induced Regulation of the Na/K ATPase

Data do not allow identification of elements of the signal transduction pathway leading to O2/NO-induced regulation of the ATPase. The cyclic GMP (cGMP) signal transduction pathway may be involved, as may be shifts in the redox state. It is also likely that nitrosylation of thiol groups of the ATPase itself or that of regulatory proteins is part of the pathway. Despite numerous reports on the NO sensitivity of the Na/K ATPase in different tissues, very little is known about the mechanisms of NO-induced regulation of the enzyme activity. In support of our findings, knocking out both nNOS and eNOS was reported to suppress Na/K ATPase function in the myocardium (Zhou et al., 2002). Activation of the Na/K ATPase by simultaneous application of NO and *O2 − was reported in denuded aortic rings (Gupta et al., 1994, 1996). However, the mechanisms of NO- induced stimulation of Na/K ATPase remain unknown. Reports on colocalization of eNOS with Na/K ATPase in the kidney medulla (McKee et al., 1994) suggest that signaling may include formation of intermediate products, thiol/amine nitrosylation.

The other set of data on NO-induced inhibition of the Na/K ATPase is mostly obtained from cells or isolated protein treated with abnormally high levels of ONOO− or NO (micromolar concentrations of presynthesized ONOO− or excessive concentrations of NO donors: see e.g., Sato et al., 1997; Muriel and Sandoval, 2000; Muriel et al., 2003; Beltowski et al., 2004; Varela et al., 2004; Kocak-Toker et al., 2005). In all of these studies NO/ONOO− caused inhibition of Na/K ATPase resulting from the oxidation of the cysteine thiol residues of the catalytic α subunit or activation of the cGMP-PKG signaling cascade. Inhibition of the Na/K ATPase following PKG activation was reported repeatedly for different tissues, including the brain (e.g., Nathanson et al., 1995; Ellis et al., 2000; Ellis and Sweadner, 2003). However, the mechanisms behind PKG-induced regulation of the Na/K ATPase remain unclear (Bogdanova et al., 2006). Our pilot studies suggest that PKG is not involved in oxygen-induced regulation of the Na/K ATPase in cerebellar granule cells (unpublished data).

Interestingly, only α1-containing isozymes of the Na/K ATPase seemed to respond to changes in oxygenation (Table I). Similar isoform-specific responses to the changes in oxygenation were observed in alveolar epithelial cells (Dada et al., 2003). α3 subunit, preferably expressed in neurons along with α1 subunit, shows no oxygen sensitivity, but is known to be much more sensitive to oxidative stress (Bogdanova et al., 2006). This suggests that molecular mechanisms engaged in oxygen- and redox-induced regulation of the Na/K ATPase differ. According to our knowledge, this is the first report on the isoform-specific NO-induced regulation of the Na/K ATPase.

Free Radical Speciation and Cellular Redox State as a Function of Oxygen Concentration

Our observations (see Fig. 1) as well as those of others (Erecinska and Silver, 2001) suggest oxygen partial pressure in the rat cerebellum in vivo increases from <1 to 3–5 kPa during maturation. This suggests that experimental work with cerebellar granule cells requires adjustment of the oxygen concentration in the incubation medium to these levels. Cells incubated in the air-equilibrated solution are necessarily exposed to oxidative stress. Results obtained using H2-DCF fluorescent dye (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 A) and GSH:GSSG measurements (Fig. 2) provide evidence for H2O2 as a major oxidant generated in cerebellar granule cells under hyperoxic conditions. An increase in H2O2 production was followed by a reduction in viability. Interestingly, prolonged (60 min) incubation of cells at different oxygen concentrations was followed by a shift in the redox state to more oxidized at pO2 20-5 kPa, whereas under hypoxic conditions (pO2 1.0-0.5 kPa) Ehc was shifted to more reduced. Thus, steady-state redox potential in freshly isolated cells was maintained only at pO2 of 3 kPa, suggesting extreme vulnerability of the cellular redox state to the changes in oxygenation. In a previous study we have shown that activity of the Na/K ATPase in cerebellar granule cells is particularly sensitive to changes in cellular redox state (Petrushanko et al., 2006). The present study suggests that oxygen-induced regulation of the enzyme is not directly driven by shifts in the cellular redox potential although the latter occur in response to the changes in pO2.

Oxygen-induced Regulation of the Cellular ATP Levels: Impact on Oxygen Sensitivity of the Na/K ATPase

Partial depletion of the cellular ATP stores was only observed in cells incubated under hypoxic conditions (pO2 0.5 kPa, see Fig. 5). A new steady-state ATP level was rapidly reached and retained over the 60-min incubation period. ATP depletion was followed by suppression of Na/K ATPase activity but not by reduction in cellular viability. In fact, survival was even improved at pO2 of 0.5 kPa compared with that at 20 kPa (Fig. 1 B). Unfortunately, low amounts of cells made direct measurements of the intracellular Na+ content technically impossible. However, according to our knowledge, reduction of the ATP content in cerebellar granule cells from ∼25 nmol/mg protein at pO2 of 20 kPa to ∼15 nmol/mg at 0.5 kPa (Petrushanko et al., 2006) should not compromise function of the Na/K ATPase with Km of ATP ranging from 0.5 to 0.1 mmol/liter water (Bogdanova et al., 2006). Thus, although occurring under hypoxic conditions, decreased cellular ATP levels are not linked to the suppression of transport and hydrolytic activity of the Na/K ATPase in our model. The latter is most probably driven by reduction in NO production and consequent shifts in the cellular redox potential.

The following question arises: to what extent does data obtained using freshly isolated neonatal cerebellar granule cells reflect the processes in the adult rat brain? Interneuronal connections in the cerebellum of neonatal rats are poorly established till postnatal days 15 coinciding with development of the vascular network to provide the growing ATP demand of the functioning brain with sufficient oxygen. (Ogunshola et al., 2000). Thus, hypoxia-induced ATP deprivation is much more pronounced in adult brain preparations compared with that in our model, which lacks electrical activity (Erecinska and Silver, 2001). On the other hand, our findings suggest that ATP consumption by the Na/K ATPase in neonatal cerebellar neurons may be controlled by the changes in oxygenation directly preventing immediate irreversible ATP depletion under hypoxic conditions.

The present study reveals that the activity of Na/K ATPase in cerebellar granule cells is extremely sensitive to the changes in oxygen concentration. Oxygen-induced regulation of Na/K ATPase is followed by changes in the cellular redox state and free radical production. Up-regulation of NO production is required to maintain maximal activity of the Na/K ATPase in the range of pO2 corresponding to physiologic normoxia.

Supplemental Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. M. Tissot van Patot and Dr. O. Ogunshola for editing the current manuscript.

This work was supported by the Roche Research Foundation (30-2003 and 56-2004), the Swiss National Science Foundation (3100B0-112449), the Molecular and Cellular Biology Program of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (07-04-01355a).

Olaf S. Andersen served as editor.

Abbreviations used in this paper: DAF-FM DA, 4-amino-5- methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein diacetate; GSH, reduced glutathione; GSSG, oxidased glutathione; H2DCF-DA, 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; MPG, mercaptopropionyl glycine; β-NADH-Na2, β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, reduced disodium salt; l-NAME, N ω-nitro-l-arginine; NOS, nitric oxide syntase; PI, propidium iodide; TCA, trichloracetic acid.

References

- Balcerczyk, A., M. Soszynski, and G. Bartosz. 2005. On the specificity of 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein as a probe for nitric oxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 39:327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltowski, J., A. Marciniak, A. Jamroz-Wisniewska, and E. Borkowska. 2004. Nitric oxide–superoxide cooperation in the regulation of renal Na+,K+-ATPase. Acta. Biochim. Pol. 51:933–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanova, A., B. Grenacher, M. Nikinmaa, and M. Gassmann. 2005. Hypoxic responses of Na/K ATPase in trout hepatocyte primary cultures. J. Exp. Biol. 208:1793–1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanova, A., O.O. Ogunshola, C. Bauer, M. Nikinmaa, and M. Gassmann. 2003. Molecular mechanisms of oxygen-induced regulation of Na+/K+ pump. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 536:231–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanova, A., I. Petrushanko, A. Boldyrev, and M. Gassmann. 2006. Oxygen- and redox-induced regulation of the Na/K ATPase. Curr. Enzyme Inhibition. 2:37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Buck, L.T., and P.W. Hochachka. 1993. Anoxic suppression of Na+-K+-ATPase and constant membrane potential in hepatocytes: support for channel arrest. Am. J. Physiol. 265:R1020–R1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buelke-Sam, J., J.F. Holson, J.J. Bazare, and J.F. Young. 1978. Comparative stability of physiological parameters during sustained anesthesia in rats. Lab. Anim. Sci. 28:157–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, A., M. Cascante, M.L. Cardenas, and A. Cornish-Bowden. 2001. Relationships between inhibition constants, inhibitor concentrations for 50% inhibition and types of inhibition: new ways of analysing data. Biochem. J. 357:263–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dada, L.A., N.S. Chandel, K.M. Ridge, C. Pedemonte, A.M. Bertorello, and J.I. Sznajder. 2003. Hypoxia-induced endocytosis of Na,K-ATPase in alveolar epithelial cells is mediated by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and PKC-ζ. J. Clin. Invest. 111:1057–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, D.Z., and K.J. Sweadner. 2003. NO regulation of Na,K-ATPase: nitric oxide regulation of the Na,K-ATPase in physiological and pathological states. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 986:534–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, D.Z., J.A. Nathanson, and K.J. Sweadner. 2000. Carbachol inhibits Na+-K+-ATPase activity in choroid plexus via stimulation of the NO/cGMP pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 279:C1685–C1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erecinska, M., and I.A. Silver. 2001. Tissue oxygen tension and brain sensitivity to hypoxia. Respir. Physiol. 128:263–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, W., P. Eaton, J.R. Bell, and M.J. Shattock. 2004. Ischemia- induced phosphorylation of phospholemman directly activates rat cardiac Na/K-ATPase. FASEB J. 18:197–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S., C. McArthur, C. Grady, and N.B. Ruderman. 1994. Stimulation of vascular Na+-K+-ATPase activity by nitric oxide: a cGMP-independent effect. Am. J. Physiol. 266:H2146–H2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S., K. Phipps, and N.B. Ruderman. 1996. Differential stimulation of Na+ pump activity by insulin and nitric oxide in rabbit aorta. Am. J. Physiol. 270:H1287–H1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain, M., and J.I. Sznajder. 2005. Effects of hypoxia on the alveolar epithelium. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2:202–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocak-Toker, N., M. Giris, F. Tulubas, M. Uysal, and G. Aykac-Toker. 2005. Peroxynitrite induced decrease in Na+, K+-ATPase activity is restored by taurine. World J. Gastroenterol. 11:3554–3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, H., M. Hirata, Y. Kudo, K. Kikuchi, and T. Nagano. 2001. Visualization of oxygen-concentration-dependent production of nitric oxide in rat hippocampal slices during aglycemia. J. Neurochem. 76:1404–1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooy, N.W., J.A. Royall, and H. Ischiropoulos. 1997. Oxidation of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin by peroxynitrite. Free Radic. Res. 27:245–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBel, C.P., H. Ischiropoulos, and S.C. Bondy. 1992. Evaluation of the probe 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin as an indicator of reactive oxygen species formation and oxidative stress. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 5:227–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvan, J., A. Briva, M.S. Wilson, G.R. Budinger, J.I. Sznajder, and K.M. Ridge. 2006. β-Adrenergic receptor stimulation and adenoviral overexpression of superoxide dismutase prevent the hypoxia-mediated decrease in Na,K-ATPase and alveolar fluid reabsorption. J. Biol. Chem. 281:19892–19898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee, M., C. Scavone, and J.A. Nathanson. 1994. Nitric oxide, cGMP, and hormone regulation of active sodium transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:12056–12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muriel, P., and G. Sandoval. 2000. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite anion modulate liver plasma membrane fluidity and Na+/K+-ATPase activity. Nitric Oxide. 4:333–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muriel, P., G. Castaneda, M. Ortega, and F. Noel. 2003. Insights into the mechanism of erythrocyte Na+/K+-ATPase inhibition by nitric oxide and peroxynitrite anion. J. Appl. Toxicol. 23:275–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson, J.A., C. Scavone, C. Scanlon, and M. McKee. 1995. The cellular Na+ pump as a site of action for carbon monoxide and glutamate: a mechanism for long-term modulation of cellular activity. Neuron. 14:781–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, G.E., and P.L. Lutz. 2004. Anoxia tolerant brains. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 24:475–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunshola, O.O., W.B. Stewart, V. Mihalcik, T. Solli, J.A. Madri, and L.R. Ment. 2000. Neuronal VEGF expression correlates with angiogenesis in postnatal developing rat brain. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 119:139–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostadal, P., A.B. Elmoselhi, I. Zdobnicka, A. Lukas, D. Chapman, and N.S. Dhalla. 2003. Ischemia-reperfusion alters gene expression of Na+-K+ ATPase isoforms in rat heart. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 306:457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palasis, M., T.A. Kuntzweiler, J.M. Arguello, and J.B. Lingrel. 1996. Ouabain interactions with the H5-H6 hairpin of the Na,K-ATPase reveal a possible inhibition mechanism via the cation binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 271:14176–14182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrushanko, I., N. Bogdanov, E. Bulygina, B. Grenacher, T. Leinsoo, A. Boldyrev, M. Gassmann, and A. Bogdanova. 2006. Na-K-ATPase in rat cerebellar granule cells is redox sensitive. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 290:R916–R925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassaf, T., M. Feelisch, and M. Kelm. 2004. Circulating NO pool: assessment of nitrite and nitroso species in blood and tissues. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 36:413–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathbun, W.B., and M.V. Betlach. 1969. Estimation of enzymically produced orthophosphate in the presence of cysteine and adenosine triphosphate. Anal. Biochem. 28:436–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royall, J.A., and H. Ischiropoulos. 1993. Evaluation of 2′,7′- dichlorofluorescin and dihydrorhodamine 123 as fluorescent probes for intracellular H2O2 in cultured endothelial cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 302:348–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato, T., Y. Kamata, M. Irifune, and T. Nishikawa. 1997. Inhibitory effect of several nitric oxide-generating compounds on purified Na+,K+-ATPase activity from porcine cerebral cortex. J. Neurochem. 68:1312–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, F.Q., and G.R. Buettner. 2001. Redox environment of the cell as viewed through the redox state of the glutathione disulfide/glutathione couple. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 30:1191–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tietze, F. 1969. Enzymic method for quantitative determination of nanogram amounts of total and oxidized glutathione: applications to mammalian blood and other tissues. Anal. Biochem. 27:502–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela, M., M. Herrera, and J.L. Garvin. 2004. Inhibition of Na-K-ATPase in thick ascending limbs by NO depends on O2− and is diminished by a high-salt diet. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 287:F224–F230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L., A.L. Burnett, P.L. Huang, L.C. Becker, P. Kuppusamy, D.A. Kass, J. Kevin Donahue, D. Proud, J.S. Sham, T.M. Dawson, and K.Y. Xu. 2002. Lack of nitric oxide synthase depresses ion transporting enzyme function in cardiac muscle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 294:1030–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.