Abstract

Ca2+ entry through store-operated Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels is an essential trigger for lymphocyte activation and proliferation. The recent identification of Orai1 as a key CRAC channel pore subunit paves the way for understanding the molecular basis of Ca2+ selectivity, ion permeation, and regulation of CRAC channels. Previous Orai1 mutagenesis studies have indicated that a set of conserved acidic amino acids in trans membrane domains I and III and in the I–II loop (E106, E190, D110, D112, D114) are essential for the CRAC channel's high Ca2+ selectivity. To further dissect the contribution of Orai1 domains important for ion permeation and channel gating, we examined the role of these conserved acidic residues on pore geometry, properties of Ca2+ block, and channel regulation by Ca2+. We find that alteration of the acidic residues lowers Ca2+ selectivity and results in striking increases in Cs+ permeation. This is likely the result of enlargement of the unusually narrow pore of the CRAC channel, thus relieving steric hindrance for Cs+ permeation. Ca2+ binding to the selectivity filter appears to be primarily affected by changes in the apparent on-rate, consistent with a rate-limiting barrier for Ca2+ binding. Unexpectedly, the mutations diminish Ca2+-mediated fast inactivation, a key mode of CRAC channel regulation. The decrease in fast inactivation in the mutant channels correlates with the decrease in Ca2+ selectivity, increase in Cs+ permeability, and enlargement of the pore. We propose that the structural elements involved in ion permeation overlap with those involved in the gating of CRAC channels.

INTRODUCTION

Depletion of Ca2+ from the ER following stimulation of cell surface receptors produces Ca2+ influx through store-operated channels (SOCs) in a wide variety of cells. One well-characterized SOC is the calcium release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channel, which is expressed by mast cells, T cells, and related hematopoetic cells. CRAC channels mediate important biological functions including gene expression during T cell activation, release of histamine and serotonin from mast cells, and the exocytosis of lytic granules from cytotoxic T cells during target cell killing (Lewis, 2001; Parekh and Putney, 2005). In light of the critical roles of CRAC channels for cellular Ca2+ signaling and the devastating immunodeficiencies that result from the loss of their activity in human patients (Partiseti et al., 1994; Feske et al., 2005, 2006), there is considerable interest in understanding the phenotypic properties, modes of regulation, and the structural bases of CRAC channel function.

Electrophysiological studies have provided a wealth of information on the CRAC channel's pore properties and point to a unique biophysical fingerprint (for reviews see Lewis, 1999; Prakriya and Lewis, 2003; Parekh and Putney, 2005). The key characteristics of this fingerprint include (1) an extraordinarily high selectivity for Ca2+ over monovalent ions (PCa/PNa > 1,000). As in voltage-gated Ca2+ (Cav) channels, this appears to arise from a high affinity Ca2+ binding site within the pore whose properties are finely honed to block permeation of monovalent ions, (2) a relatively narrow pore size of ∼3.9 Å (Prakriya and Lewis, 2006), which is in striking contrast to the much larger pores of Cav channels (Cataldi et al., 2002), (3) a very low permeability to Cs+ (PCs/PNa∼0.1) that is also in contrast to the higher Cs+ permeability of Cav channels (Hess et al., 1986) and Ca2+-selective TRP channels (Voets et al., 2001), (4) an extremely low unitary conductance for both divalent and monovalent ions, and (5) multiple modes of modulation by Ca2+. The recent identification of the Orai family of proteins, thought to be the pore-forming subunits of store-operated channels (Feske et al., 2006; Vig et al., 2006b; Zhang et al., 2006), and the expression of functional CRAC currents from cloned Orai1 provide the necessary tools to elucidate the molecular underpinnings of these unique characteristics.

The Orai family consists of three closely conserved cell surface proteins (Orai1–3), each of which contains four predicted transmembrane domains with intracellular N and C termini (Feske et al., 2006; Prakriya et al., 2006). There is considerable evidence that Orai1 is a key subunit of the CRAC channel. First, a mutation in Orai1 (R91W) that causes a severe immunodeficiency in human patients eliminates ICRAC in T cells (Feske et al., 2006). Second, overexpression of Orai1 together with STIM1 in HEK293 cells generates a large Ca2+ current similar to native ICRAC in its biophysical and pharmacological profile (Mercer et al., 2006; Peinelt et al., 2006). Third, Orai1 contains a set of acidic residues that when altered greatly diminishes the Ca2+ selectivity of CRAC channels (Prakriya et al., 2006; Vig et al., 2006a; Yeromin et al., 2006). This is reminiscent of Cav channels, whose selectivity filters contain glutamate residues that are essential for high Ca2+ selectivity.

The acidic residues examined in the recent mutational studies include glutamates at positions 106 and 190 in TM1 and TM3 and aspartates at positions 110, 112, and 114 in the linker region between TM1 and TM2 (Prakriya et al., 2006; Vig et al., 2006a; Yeromin et al., 2006). By analogy to Cav channels, it is speculated that these residues form the key elements of the CRAC channel selectivity filter with the carboxylate-bearing side chains projecting into the pore to form one or more Ca2+-binding sites (Prakriya et al., 2006; Vig et al., 2006a; Yeromin et al., 2006). However, in the absence of knowledge of the number of subunits that make up the pore and lack of any structural information on the channel, a number of fundamental uncertainties persist about the characteristics of the selectivity filter. These uncertainties include the locations of the acidic residues within the pore and their role in shaping the overall pore architecture, the relationship between the pore diameter and ion permeation, and the affinity and kinetic properties of the Ca2+ binding site(s).

Much less is known about the molecular features of CRAC channel gating. In addition to its dependence on the luminal ER [Ca2+], the activity of CRAC channels is regulated at multiple levels. One mode of regulation, termed fast inactivation, arises from feedback inhibition of ICRAC during brief hyperpolarizing steps and is influenced by the local [Ca2+]i around individual CRAC channels (Hoth and Penner, 1993; Zweifach and Lewis, 1995a; Fierro and Parekh, 1999). Although the inactivation Ca2+-binding site has been mapped to the cytoplasmic face of the channel in close proximity to the pore (Zweifach and Lewis, 1995a), important details of the inactivation mechanism such as the molecular identities of the inactivation gate and the Ca2+ binding site(s), and the mechanisms that transduce Ca2+ binding to closure of the inactivation gate remain unknown.

In this study, we show that the same Orai1 acidic residues implicated in the control of Ca2+ selectivity are also important for regulating the CRAC channel pore geometry, Ca2+ block, and channel gating. We find that the loss of Ca2+ selectivity that results from alteration of the acidic residues is accompanied by striking increases in the CRAC channel pore diameter and Cs+ permeability, suggesting that the architecture of the pore as shaped by these residues strongly influences ion permeation. The mutations do not affect the CRAC channel's requirement for store depletion for activation, nor do they affect the spatial redistribution of Orai1 localization that occurs following store depletion, suggesting that the overall Orai1 structure is intact. Unexpectedly, alteration of the acidic residues also produces striking loss of Ca2+-dependent fast inactivation. These results suggest that the structural determinants of CRAC channel gating overlap with those involved in ion permeation, and raise the possibility that the opening and closing of the channel is regulated by the selectivity filter itself.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells

HEK293 cells were grown in a medium consisting of 44% DMEM (Mediatech) and 44% Ham's F12 (Mediatech), supplemented with 10% FCS (HyClone), 1% 200 mM glutamine, 1% 5,000 U/ml penicillin, and 5,000 μg/ml streptomycin. The cells were maintained in log-phase growth at 37°C in 5% CO2.

In some experiments, HEK293 cells grown in a medium consisting of CD293 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2% 200 mM GlutaMAX (Invitrogen) were used. These cells were grown in suspension at 37° in 5% CO2, plated onto poly-l-lysined coverslips at the time of passage, and grown in FBS-supplemented media (described above) until the time of transfection (24–48 h later).

Plasmids and Transfections

The IRES-eGFP-Orai1 plasmid was provided by S. Feske (Harvard University, Boston, MA). Site-directed mutagenesis to generate the Orai1 mutants was performed using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) according to manufacturer's instructions. The following mutations were generated: E106D, E190Q, and the D110/112/114A triple mutant. HEK293 cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), with 100 ng of Orai1 and 500 ng STIM1 per 12-mm coverslip. Cells were used for electrophysiology 24–48 h after transfection.

Solutions and Chemicals

The standard extracellular Ringer's solution contained (in mM) 135 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 20 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 d-glucose, and 5 Na-HEPES (pH 7.4). The standard divalent-free (DVF) Ringer's solution contained (in mM) 150 NaCl, 10 HEDTA, 1 EDTA, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4 with N-methyl-d-glucamine [NMDG] hydroxide). The 110 mM Ca2+ solution contained 110 CaCl2, 10 d-glucose, and 5 HEPES (pH 7.4). Where indicated, BaCl2 was substituted for CaCl2 in this solution. The 12 mM Ba2+ solution contained (in mM) 12 mM BaCl2, 118 NMDG chloride, 10 d-glucose, and 5 HEPES (pH 7.4). For experiments examining block of Na+-ICRAC by Ca2+ of the WT Orai1 channels, CaCl2 was added to the standard DVF solution at the appropriate amount calculated from the MaxChelator software (WEBMAXC 2.10, available at http://www.stanford.edu/∼cpatton/webmaxc2.htm). For the experiments examining block of Na+-ICRAC by Ca2+ in E106D-expressing HEK cells, MgCl2 was omitted from the standard extracellular solution and CaCl2 was added to the indicated concentration (i.e., this solution did not contain HEDTA or EDTA). Where indicated, the following organic compounds (purchased from Sigma-Aldrich) were substituted for NaCl in the standard DVF solution: ammonium chloride (NH4Cl), methylamine HCl (CH3NH2-HCl), dimethylamine HCl ((CH3)2NH-HCl), trimethylamine HCl ((CH3)3N-HCl), and tetramethylammonium chloride ((CH3)4NCl), hydroxylamine HCl (NH2OH-HCl), and hydrazine HCl (NH2NH2-HCl). pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NMDG except in the case of hydrazine HCl (pH 6.4) and hydroxylamine HCl (pH 6.2), which were studied at acidic pH to increase the ionized concentration of the test ion. 10 mM TEA-Cl was included in all extracellular solutions to prevent contamination from K+ v channels. The standard internal solution contained (in mM) 135 Cs aspartate, 8 mM MgCl2, 8 BAPTA, and 10 Cs-HEPES (pH 7.2). Where indicated, 10 mM EGTA was substituted for BAPTA in the internal solution.

Stock solutions of thapsigargin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate (2-APB) (Sigma, 20 μM) were prepared in DMSO at concentrations of 1 mM and 20 mM. All solutions were applied using a multibarrel local perfusion pipette with a common delivery port. Reversal potential measurements with 150 mM extracellular KCl applications indicated that the solution exchange time was <1 s.

Patch-Clamp Measurements

Patch-clamp recordings were performed using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments) interfaced to an ITC-18 input/output board (Instrutech) and an iMac G5 computer. Currents were filtered at 1 kHz with a 4-pole Bessel filter and sampled at 5 kHz. Recording electrodes were pulled from 100-μl pipettes, coated with Sylgard, and fire polished to a final resistance of 2–5 MΩ. Stimulation, data acquisition, and analysis were performed using in-house routines developed on the Igor Pro platform (Wavemetrics). Data are corrected for the liquid junction potential of the pipette solution relative to Ringer's in the bath (−10 mV). The holding potential was +30 mV unless otherwise indicated. Two types of stimuli were usually employed as indicated in the figure legends: (1) a 100-ms step to −100 mV followed by a 100-ms ramp from −100 to +100 mV usually applied every 1 s, or (2) a 300-ms step to −100 mV applied every 1 s. For variance/mean analysis, 200-ms sweeps were acquired at the rate of 4 Hz at a constant holding potential of −100 mV, digitized at 5 kHz, low-pass filtered using a 2 kHz Bessel filter, and recorded directly to hard disk. The mean current and variance were calculated from each sweep.

Data Analysis

The analysis of currents transfected with E190Q Orai1 presented special problems. A large fraction of HEK293 cells transfected with E190Q Orai1 cDNA (typically ∼30%) exhibited a small ICRAC-like current in 20 mM Ca2+ o (current density ≤2 pA/pF) and with I-V characteristics similar to native CRAC channels (reversal potential >+70 mV in 20 mM Ca2+ o and >+40 mV in DVF solutions). The remaining cells exhibited large currents (typically ≥10 pA/pF) with a reversal potential of ∼+25 mV in 20 mM Ca2+ o and ∼0 mV in DVF solutions. Because previous reports have demonstrated significant loss of Ca2+ selectivity and gain of Cs+ permeation by the E190Q Orai1 mutation (Prakriya et al., 2006; Vig et al., 2006a), we assumed that the cells with the small CRAC-like currents had failed to express E190Q Orai1, and manifested predominantly the endogenous CRAC current. Therefore, these cells were excluded from the analysis. For all mutants, only those cells exhibiting current densities ≥10 pA/pF were included for the analysis to exclude potential problems arising from the contamination of the ectopically expressed Orai1 channels by native CRAC channels of HEK293 cells.

Unless noted otherwise, all data were corrected for leak currents collected in 20 mM Ca2+ + 10–100 μM La3+. In cells expressing the D110/112/114A Orai1 triple mutant, 100 μM of La3+ was employed to account for diminished lanthanide sensitivity of these currents (Yeromin et al., 2006). Averaged results are presented as the mean value ± SEM. All curve fitting was done by least-squares methods using built-in functions in Igor Pro 5.0.

Relative permeabilities were calculated from changes in the reversal potential using the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) voltage equation:

|

(1) |

where R, T, and F have their usual meanings, and Px and PNa are the permeabilities of the test ion and Na+, respectively, [X] and [Na] are the ionic concentrations, and ΔErev is the shift in reversal potential when the test cation is exchanged for Na+.

To analyze the voltage dependence of block of Na+-ICRAC by Ca2+ o, the model described by Guo and Lu (2000) was employed. This model does not specify the location of the binding site within the field, but instead expresses voltage dependence in terms of an apparent valence, an empirical factor that encompasses the effects of blocker valence and the coupled movements of conducting and blocking ions within the field.

Ca2+ binds to a site within the pore according to the reaction:

|

where Ch is the channel, Ca2+ o and Ca2+ i are extracellular and intracellular Ca2+, k1 and k−1 are the binding and unbinding rates from the extracellular side, k2 is the unbinding rate from the intracellular side, and each zi represents the apparent valence for the corresponding transition. We assumed that block from the intracellular compartment is negligible due to nM intracellular Ca2+ concentrations. With these assumptions, the fraction of unblocked current is given by Guo and Lu (2000):

|

(2) |

where K 1 = k −1/k 1 is the equilibrium dissociation constant at 0 applied voltage, and Z 1 and zi are the apparent valences. Z 1 (= z 1 + z −1) provides a measure of the overall voltage dependence of Ca2+ block and arises from the movement of the charged blocker (Ca2+) within the field as well as the possible displacement of permeant ions (Na+) within the pore. k 2/k −1 is the ratio of the rates of Ca2+ escaping into the cytoplasm vs. returning to the extracellular solution from the pore, and thus provides a measure of Ca2+ permeation. The quantities k 2/k −1, and z −1 + z 2 were treated as single adjustable parameters for fitting the data.

Online Supplemental Material

The online supplemental material (Figs. S1–S3, available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200709872/DC1) contains additional information about the store dependence of activation of the wild-type and mutant CRAC channels, and about the kinetics of fast inactivation in currents arising from WT Orai1 and E190Q Orai1.

RESULTS

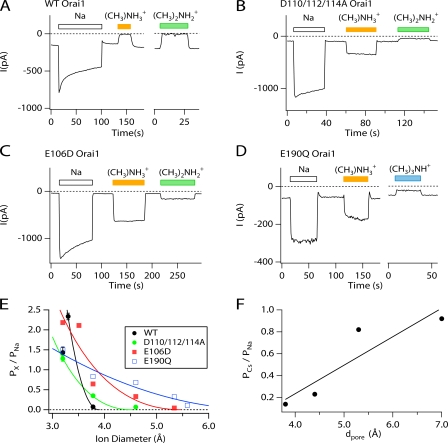

Mutations in the Putative Selectivity Filter Increase Cs+ Permeability of CRAC Channels

Recent studies have implicated a set of acidic residues, glutamates at positions 106 and 190 in TM1 and TM3, respectively, and aspartates (D110, D112, and D114) in the TM1–TM2 linker region of human Orai1, as important determinants of the Ca2+ selectivity of CRAC channels (Prakriya et al., 2006; Vig et al., 2006a; Yeromin et al., 2006). To uncover additional roles of these residues on ion selectivity, pore geometry, and channel gating, we constructed the E106D, E190Q, and D110/112/114A mutants. The mutations did not change the requirement for Ca2+ store depletion to occur before CRAC channel activation (see Fig. S1, available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200709872/DC1), nor did they affect the spatial redistribution of Orai1 into discrete puncta that follows store depletion (not depicted), suggesting that the alterations do not perturb the overall Orai1 structure. However, as previously shown for some residues, an important unexpected consequence of the mutations is a dramatic increase in Cs+ permeability (Prakriya et al., 2006; Vig et al., 2006a; Yeromin et al., 2006). This is illustrated in Fig. 1. HEK293 cells overexpressing either wild-type (WT) or mutant Orai1 together with STIM1 were pretreated with thapsigargin (TG, 1 μM) for 5–10 min before seal formation to deplete Ca2+ stores and activate ICRAC. As previously shown, overexpression of WT Orai1 and STIM1 in HEK293 cells reconstituted a Ca2+-selective inward current with key properties similar to native CRAC channels (Mercer et al., 2006; Peinelt et al., 2006). As in native CRAC channels, application of a Na-based divalent free (DVF) solution elicited a prominent Na+ current (Fig. 1 A), indicating that Orai1-encoded channels readily conduct Na+ in the absence of extracellular divalent ions. However, application of a Cs+-based DVF solution elicited only a small monovalent current (Fig. 1 A), consistent with the low Cs+ permeability of native CRAC channels (Lepple-Wienhues and Cahalan, 1996; Kozak et al., 2002; Prakriya and Lewis, 2002).

Figure 1.

Mutation of key Orai1 acidic residues enhances Cs+ permeation through CRAC channels. (A–D) Na+ and Cs+ currents were measured from HEK293 cells overexpressing WT Orai1 or mutant Orai1. Cells were pretreated with 1 μM TG to deplete stores and activate CRAC channels. Leak-corrected currents at −100 mV are plotted against time as the extracellular solution was periodically switched between 20 mM Ca2+ and Na+- or Cs+-based DVF solutions. Application of a Cs+-based DVF solution to cells expressing WT Orai1 fails to elicit significant monovalent CRAC current, whereas cells expressing the mutant Orai1 channels manifest significant Cs+ currents. (E) Plots of the I-V relationship of monovalent currents through CRAC channels in the presence of Na+-based DVF solution. The internal solution was Cs+-aspartate in all experiments.

In contrast to WT Orai1, application of a Cs+-based DVF solution elicited prominent inward currents in HEK293 cells overexpressing mutant Orai1 constructs (Fig. 1). With a Cs+-based pipette solution, the bi-ionic reversal potentials in the standard (Na+-based) DVF solution were 51 ± 2 mV (WT Orai1; n = 11), 6 ± 1 mV (E106D Orai1; n = 9), 40 ± 4 mV (D110/112/114A Orai1; n = 6), and 3 ± 0.7 mV (E190 Orai1; n = 5), which indicate relative Cs+ permeabilities (PCs/PNa) of 0.14 ± 0.009 (WT Orai1), 0.82 ± 0.03 (E106D Orai1), 0.23 ± 0.05 (D110/112/114A Orai1), and 0.92 ± 0.03 (E190Q Orai1), respectively. Thus, mutations within the proposed selectivity filter of the CRAC channel increase Cs+ permeability.

Orai1 Mutations that Affect Cs+ Selectivity Alter CRAC Channel Pore Geometry

What structural change in the pore is responsible for the increased Cs+ permeability in the mutants? The limiting dimension of the narrowest region of the pore of the native CRAC channel (∼3.9 Å) is very close to the atomic diameter of Cs+ (∼3.8 Å), suggesting that steric hindrance could explain the CRAC channel's unusually low permeability to Cs+ (Prakriya et al., 2006). We hypothesized that the increased Cs+ permeability conferred by the above mutations arises from an increase in the apparent pore diameter of the CRAC channel.

To test this hypothesis, we estimated the narrowest region of the pore of CRAC channels arising from overexpression of wild-type and mutant Orai1. In each case, the minimal dimension of the pore was estimated by examining permeation of a series of organic monovalent cations of increasing size (Prakriya and Lewis, 2006). Ammonium and its methylated derivatives are commonly used to estimate pore size because the progressive addition of methyl groups results in a gradual increase in ion size without introducing gross modifications in the overall ion structure (Dwyer et al., 1980; Burnashev et al., 1996). The diameters of these ions estimated from Corey-Pauling-Koltun space-filling models are as follows (Liu and Adams, 2001): NH4, 3.2 Å; hydroxylammonium, 3.30 Å; methylammonium, 3.78 Å; dimethylammonium, 4.6 Å; trimethylammonium, 5.34 Å; and tetramethylammonium (TMA), 5.6 Å. Experiments were performed in buffered Ca2+-free solutions to avoid the potent blocking effects of Ca2+ ions on monovalent CRAC channel currents.

Like native CRAC channels (Prakriya and Lewis, 2006), channels arising from overexpression of WT Orai1 in HEK293 cells failed to appreciably conduct methylated ammonium derivatives (Fig. 2 A). By contrast, large stable currents carried by methylammonium were easily detectable in channels arising from overexpression of E106D, E190Q, and the D110/112/114A triple mutants of Orai1 (Fig. 2, B–D). N-methyl-d-glucamine+ was not measurably permeant through any of the Orai1 mutants. The relative permeabilities for the various cations were calculated from changes in reversal potential using the GHK equation (Eq. 1). If we assume that these permeabilities are influenced primarily by steric hindrance rather than ion interactions with the pore, the permeabilities should follow the hydrodynamic relationship (Dwyer et al., 1980; Burnashev et al., 1996)

|

(3) |

A fit of this relationship to the plot of permeability against ion diameter gives an estimated dpore of 3.8 Å for WT Orai1, close to the value reported previously for native CRAC channels in Jurkat T cells (3.9 Å; Prakriya and Lewis, 2006). By contrast, estimates of dpore for the Orai1 mutants D110/112/114A Orai1, E106D Orai1, and E190Q Orai1 were 4.4, 5.3, and 7.0 Å, respectively (Fig. 2 E). Thus, Orai1 mutations that diminish the Ca2+ selectivity of CRAC channels significantly alter the geometry of the pore. Importantly, the enhancement of the relative Cs+ permeability of mutant channels was well correlated with the increase in dpore (Fig. 2 F), suggesting that the augmentation of Cs+ permeation in the mutant channels arises from relief of steric hindrance to Cs+ mobility.

Figure 2.

Orai1 mutations increase the pore diameter of CRAC channels. (A–D) TG-treated HEK293 cells expressing either WT Orai1 or mutant Orai1 were exposed to DVF solutions containing either Na+ or the indicated organic monovalent cation. Methylammonium and larger derivatives of ammonium fail to carry significant current through WT Orai1 channels, but these cations produce significant currents through the mutant channels. (E) The permeabilities of NH4 + and its methylated derivatives relative to Na+ are plotted against the size of each cation. The solid lines are least-squares fit to Eq. 3. The values of dpore estimated from the fits are 3.8 Å (WT Orai1), 4.4 Å, (D110/112/114A Orai1), 5.3 Å (E106D Orai1), and 7.0 Å (E190Q Orai1). (F) Plot of the relative Cs+ permeability (PCs/PNa) against the estimated dpore for WT and mutant Orai1 channels. The straight line is a linear regression with a Pearson's correlation coefficient (R) of 0.91.

The E106D Substitution Alters the Properties of Ca2+ Block of Na+-ICRAC

In currents arising from overexpression of E106D Orai1, we observed the appearance of a rapid phase of current decay during hyperpolarizing pulses in 20 mM Ca2+ o Ringer's solution (Fig. 3 A). The current decay could be well fit with a single exponential function with a time constant of ∼1.5 ms. We considered two explanations for this rapid current decay. First, because the E106D substitution dramatically lowers the CRAC channel's permeability to Ca2+ and elevates Na+ permeation (Prakriya et al., 2006; Vig et al., 2006a; Yeromin et al., 2006), the rapid current decay could arise from blockade of Na+ conduction by Ca2+. An alternative possibility is that it reflects Ca2+-dependent fast inactivation of CRAC channels (Zweifach and Lewis, 1995a; Fierro and Parekh, 1999). However, this form of inactivation requires hundreds of milliseconds for completion (e.g., Fig. 5 A), a significantly slower time course than the rapid decay of E106D Orai1 currents seen here (Zweifach and Lewis, 1995a; Fierro and Parekh, 1999).

Figure 3.

A rapid phase of current decay in E106D Orai1 channels arising from Ca2+ block of Na+ permeation. (A) HEK293 cells overexpressing E106D Orai1 were treated with thapsigargin to activate ICRAC. Traces show the sequential recordings of current during 300-ms hyperpolarizations to −100 mV from one cell in the presence of 20 mM Ca2+ o (with 130 mM Na+) then shortly after Ca2+ concentration was increased to 110 mM Ca2+ o (with 0 Na+). A rapid phase of current decay seen in the 20 mM Ca2+ o (+130 mM Na+ o) solution (indicated by the arrow) is not seen in 110 mM Ca2+ (+0 mM Na+ o), suggesting that this transient current arises from Ca2+ block of Na+ permeation. (B) [Ca2+]o dependence of the time constant of Na+-ICRAC decay. The fast decay of currents in 20 mM Ca2+ o was fitted by a single exponential function to obtain the time constant of block.

Figure 5.

Alteration of Orai1 acidic residues diminishes fast inactivation. (A–D) Representative traces showing fast inactivation in WT and mutant Orai1 channels during hyperpolarizing steps to −100 mV applied every second. Note that the current measured in 20 mM Ca2+ from E106D channels shows Ca2+ block of Na+-ICRAC (Fig. 3). Currents measured through E190Q channels exhibit complex kinetics with a small initial decay followed by strong enhancement during the voltage step. (E and F) Alteration of fast inactivation in the mutants in the presence of 20 and 110 mM [Ca2+]o. Inactivation of ICRAC was quantified here as fraction of the remaining current, Iss/Ipeak, where Ipeak and Iss are the currents at the start and end of the 300-ms voltage pulses. Inactivation of current arising from E106D Orai1 channels could not be assessed in 20 mM Ca2+ o due to rapid block of Na+ permeation (Fig. 3). * indicates significant (P < 0.05) difference between mutant and WT currents. Each point shows mean ± SEM from at least five cells.

To distinguish between these possibilities, we performed experiments in isotonic Ca2+ (110 mM Ca2+ o with 0 Na+), which should eliminate confounding effects of Na+ permeation. Substitution of 20 mM Ca2+ (+130 mM NaCl) with 110 mM Ca2+ (+0 NaCl) abolished the rapid current decay, indicating that it arises from Ca2+ block of Na+ permeation through E106D Orai1 channels. Further evidence for this conclusion was provided by the finding that increasing the Ca2+ concentration progressively accelerates the rate of current decay (Fig. 3 B), as would be expected from the kinetics of a first order Ca2+ binding reaction to a site within the pore (Eq. 4).

The appearance of time-dependent block in 20 mM Ca2+ o and diminished Ca2+ selectivity (Prakriya et al., 2006) indicates that the E106D Orai1 substitution alters the energetics of Ca2+ binding to the CRAC channel pore. This was examined further by two approaches. First, we measured the voltage dependence of Ca2+ blockade of Na-ICRAC. Voltage-dependent blockade of ion channels generally arises from the combined interaction of blocking molecules with specific pore sites and conducting ions. Thus, alteration of the voltage dependence would provide evidence that E106 regulates Ca2+ binding to the pore. Second, we quantified the rates of Ca2+ entry and exit from its binding site to determine the role of E106 in controlling the kinetic properties of Ca2+ block.

Ca2+ o blocked Na+-ICRAC through WT Orai1 channels in a dose-dependent manner with a K i of 23 μM and a Hill coefficient of 1.0 (n = 4 cells, Fig. 4 A). As shown previously, the E106D substitution increased the K i of block, in this case, to 490 μM with a Hill coefficient of 1.3 (n = 4 cells, Fig. 4 A). Hyperpolarizing steps revealed that the block was strongly voltage dependent, resulting in a rapid, time-dependent decrease in Na+-ICRAC amplitude (Fig. 4 C). The magnitude of block was estimated as (1-Iss/Ipk), where Iss and Ipk are the steady-state and extrapolated peak currents during each voltage step. The results, plotted for five cells in Fig. 4 D, show voltage-dependent blockade that increases with hyperpolarization. In WT Orai1-mediated currents, the block peaked at −100 mV and declined at more negative potentials, a phenomenon also seen in native CRAC channels and likely reflecting escape of Ca2+ into the cytoplasm (Prakriya et al., 2006). However, in E106D Orai1 currents, relief of block at negative voltages was not seen.

Figure 4.

The E106D Orai1 substitution alters the properties of Ca2+ block of Na+-ICRAC. (A) Inhibition of E106D Orai1 Na+ currents by Ca2+ o. A TG-treated cell was exposed to various concentrations of [Ca2+]o as indicated by the bars. 20 mM Ca2+ o was present in between the bars. The leak-corrected steady-state current measured at the end of 300-ms hyperpolarizing pulses to −100 mV is plotted against time. (B) Concentration dependence of Na+-ICRAC block by Ca2+ o in WT and E106D Orai1 currents. The solid line is a least-square fit of the Hill equation, block = 1/[1 + (Ki/[Ca])n] with Ki = 23 μM and n = 1.06 (WT Orai1), and Ki = 490 μM and n = 1.3 (E106D Orai1). Each point shows mean ± SEM from four to five cells from recordings similar to that shown in A. (C) Effects of 300 and 600 μM Ca2+ o on Na+ currents during voltage steps. Hyperpolarizing voltage steps from −120 to 0 mV lasting 250 ms were applied from a holding potential of +50 mV in each solution. Note the time-dependent reduction of Na+ currents in the presence of Ca2+ o within the first 20 ms following the hyperpolarizing step (indicated by the arrow). (D) Voltage dependence of Ca2+ o block. Block was quantified, as [1 − Iss/Ipeak], where Ipeak and Iss are the currents at the start and end of the voltage pulse. Ipeak was determined from a fit of the current decay with a single exponential function and extrapolating back to the start of the voltage pulse. The solid lines are a least-squares fit to Eq. 2. Fit parameters were as follows: WT Orai1 (20 μM): Z 1 = 0.78, K 1 = 440 μM, z −1 + z 2 = 1.7, and k 2/k −1 = 0.0007. E106D Orai1([Ca] = 600 μM): Z 1 = 1.4, K 1 = 820 μM, z −1 + z 2 = 1.2, and k 2 /k −1 = 0.09. E106D Orai1([Ca] = 300 μM): Z 1 = 1.27, K 1 = 1200 μM, z −1 + z 2 = 1.14, and k 2/k −1 = 0.09. (E) The time constant of block plotted against [Ca2+]o. Tau was obtained by fitting the current decay in the presence of Ca2+ o with a single exponential function. In D and E, each point shows mean ± SEM from four to five cells.

To describe the voltage dependence of block of Na+-ICRAC by Ca2+ o, we employed a model that has been previously used to describe Ca2+ block in native CRAC channels of Jurkat T cells (Prakriya and Lewis, 2006) (see Materials and methods). This model incorporates a permeant blocker without specifying the location of the Ca2+ binding site within the pore (Guo and Lu, 2000). For currents arising from overexpression of WT Orai1, the key parameters extracted from this model, the apparent valence Z 1 and the dissociation constant at zero applied voltage, K 1, were 0.78 and 440 μM. These values are similar to those reported for native CRAC channels in Jurkat T cells (Prakriya and Lewis, 2006). For currents arising from E106D Orai1, the model yielded Z 1 and K 1 values of 1.4 and 820 μM at [Ca2+] of 600 μM, and 1.27 and 1,200 μM at [Ca2+] of 300 μM, respectively. Thus, these results indicate that the E106D Orai1 substitution alters the voltage dependence of Ca2+ block. This change could arise either due to alteration in the location of the binding site within the pore or alteration in the degree of displacement of the conducting ions (Na+) by the blocker (Ca2+) across the electric field. In either case, the alteration of the voltage dependence of Ca2+ block is consistent with the idea that E106 controls Ca2+ binding to the pore.

Further, the kinetics of block revealed from experiments in Fig. 4 (D and E) were used to obtain information about the on- and off-rates of Ca2+ binding to the block site. At 600 μM [Ca2+] the observed time constant of block is ∼7.2 ms at −100 mV (Fig. 4 E). Assuming that Ca2+ accesses a single binding site from the extracellular side at a rate kon and exits in both directions at a combined rate koff then it follows that

|

(4) |

The fraction of channels that are blocked is given by

|

(5) |

Substituting the measured values of τ and the fractional block in Eqs. 4 and 5, we get kon = 9.8 × 104 M−1s−1 and koff = 94 s−1 for E106D Orai1-mediated currents. By contrast, kon and koff values for currents arising from WT Orai1 were 4.0 × 106 M−1s−1 and 116 s−1. Thus, these results indicate that the E106D Orai1 substitution results in a striking reduction in the kon for Ca2+ binding. Taken together, these results suggest that the E106 regulates high affinity Ca2+ binding within the CRAC channel pore, probably by directly interacting with the conducting ions.

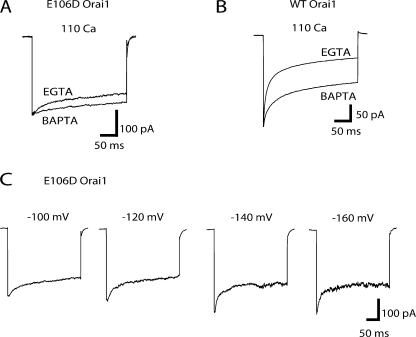

Alteration of Orai1 Acidic Residues Diminishes Ca2+-dependent Fast Inactivation

Fast inactivation is a prominent hallmark of CRAC channels and occurs from feedback inhibition of channel activity by the local [Ca2+]i around CRAC channels (Hoth and Penner, 1993; Zweifach and Lewis, 1995a; Fierro and Parekh, 1999). The lack of detectable inactivation during hyperpolarizing steps in the above experiments with 110 mM Ca2+ o (Fig. 3 A) hinted at an alteration of this process in currents arising from overexpression of E106D Orai1 and prompted us to investigate fast inactivation in greater detail in all the mutants. Fast inactivation was assessed by measuring the extent of current decay during 300-ms hyperpolarizing pulses to −100 mV in 20 and 110 mM Ca2+ o solutions. The 110 mM Ca2+ o solution confers the advantage that because Ca2+ carries all of the current, any confounding effects of Na+ permeation that might occur in the 20 mM Ca2+ o solution are eliminated. Additionally, the driving force for Ca2+ entry, and therefore the local [Ca2+] around the cytoplasmic face of the channel, is enhanced in isotonic Ca2+ o, thereby accentuating Ca2+-mediated fast inactivation.

We have previously shown that currents arising from the overexpression of WT Orai1 in human T cells derived from SCID patients exhibit fast inactivation with properties resembling the inactivation of CRAC currents in Jurkat T cells (Feske et al., 2006). ICRAC arising from overexpression of WT Orai1 + STIM1 in HEK293 cells also exhibited fast inactivation that was visible both during short (300 ms) and long (2 s) hyperpolarizing voltage steps (Fig. 5 A and Fig. S2). In the D110/112/114A Orai1 triple mutant, there was a small but significant reduction in the extent of fast inactivation in 20 and 110 mM [Ca2+]o solutions. In currents arising from E106D Orai1, fast inactivation could only be assessed in 110 mM Ca2+ o as currents in 20 mM Ca2+ o + 130 mM Na+ resulted in rapid block of Na+ permeation (Fig. 3). In these mutant channels, fast inactivation in 110 mM Ca2+ o was virtually absent. The most striking effect was in currents arising from the E190Q Orai1 substitution. Instead of inactivation, hyperpolarizing steps in 20 mM Ca2+ o triggered a gradual, time-dependent enhancement of the current (Fig. 5 D) in these channels. Examination of currents in 110 mM Ca2+ o revealed an additional degree of complexity. In this condition, an initial decay of the current lasting ∼40 ms was followed by robust enhancement resulting in a significantly larger current at the end of the hyperpolarizing step (Fig. 5 D). Switching the external solution to a DVF solution eliminated the time-dependent enhancement of the current (Fig. 5 D), indicating that the facilitation during hyperpolarization is Ca2+ dependent. Additionally, increasing [Ca2+]o from 2 to 110 mM progressively increased the degree of enhancement (Fig. S3). Thus, it appears that the E190Q substitution alters Ca2+ regulation of the channel such that feedback inactivation during hyperpolarizing pulses is overcome by strong Ca2+-mediated facilitation.

Fig. 5 (E and F) tabulates the degree of inactivation seen in WT Orai1 and in the three mutants analyzed. All mutations disrupted fast inactivation, with the largest changes occurring in the E106D and E190Q substitutions. These results indicate that the mutations that affect Ca2+ and Cs+ selectivity also result in significant alterations in CRAC channel gating. Plots of the extent of inactivation against reversal potentials measured in 20 mM Ca2+ o and DVF solutions showed a positive correlation (Fig. 6, A and B), suggesting a link between inactivation and the changes in Ca2+ (Fig. 6 A) and Cs+ selectivity (Fig. 6 B), respectively. The extent of inactivation also exhibited a positive correlation with the apparent pore diameter (Fig. 6 C), suggesting that the changes in pore geometry may be linked to the changes in inactivation.

Figure 6.

Alteration of inactivation is correlated with changes in ion selectivity and pore diameter. (A and B) Inactivation of ICRAC measured in 110 Ca2+ is plotted against the reversal potential of currents measured in either 20 mM Ca2+ (A) or in DVF solution (B) for WT and mutant Orai1 channels. Inactivation of ICRAC was quantified as Iss/Ipeak, where Ipeak and Iss are the currents at the start and end of a 300-ms voltage pulse to −100 mV, respectively. The Pearson's correlation coefficients (R) for plots in A and B are 0.81 and 0.92, respectively. (C) Inactivation ICRAC measured in 110 mM Ca2+ o is plotted against the measured pore diameter determined from Fig. 2 E. The Pearson's correlation coefficient (R) for this plot is 0.99.

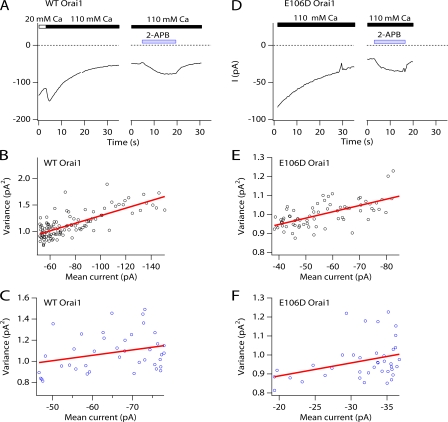

Diminished Inactivation Is Not due to Reduced [Ca2+] in the Vicinity of the CRAC Channel Pore or a Leaky Inactivation Gate

The apparent loss of fast inactivation in the mutant Orai1 channels could in principle arise from reduction of the Ca2+ concentration at the inactivation binding site, decrease in the ability of the inactivation gate to block ion conduction because of enlargement of the pore, or an alteration of some aspect of the inactivation gating machinery itself. We investigated the contribution of these factors in several ways: by estimating the unitary conductance of CRAC channels using noise analysis, by examining inactivation due to conduction of ions larger than Ca2+, and by varying the intracellular buffering of Ca2+ and therefore the local [Ca2+]i near CRAC channels. For simplicity, these tests were applied to the E106D Orai1 substitution because the changes in fast inactivation, ion selectivity, and pore geometry introduced by this mutation are large, providing an optimal tool to explore whether loss of inactivation is linked to changes in ion selectivity and/or pore geometry.

Diffusion models predict that the local [Ca2+]i a short distance away from the Ca2+ channel pore is directly related to the unitary Ca2+ current (Neher, 1986). Thus, any reduction in the unitary conductance would strongly diminish the local [Ca2+] in the vicinity of the inactivation binding site and reduce fast inactivation. To test for alteration of unitary Ca2+ current, we used nonstationary noise analysis to compare the unitary conductance of CRAC channels arising from WT Orai1 and E106D Orai1. The mean (I) and variance (σ2) of the macroscopic currents were calculated for a series of 200-ms epochs in TG-treated cells in 110 mM Ca2+. As shown previously for endogenous CRAC channels in Jurkat T cells (Zweifach and Lewis, 1993), a switch of the extracellular solution from 20 to 110 mM Ca2+ causes ICRAC to increase rapidly and then decay slowly (Fig. 7 A), possibly from slow Ca2+-dependent inactivation (Zweifach and Lewis, 1995b). Plots of the current variance against the mean current amplitude obtained during the slow decay of the current were well fitted by straight lines (Fig. 7). The average slopes (σ2/I) in WT Orai1 and E106D Orai1 currents were −6.6 ± 1.6 (n = 5) and −6.5 ± 1.6 fA (n = 4), respectively. Furthermore, application of a low concentration of 2-APB (5 μM), which is known to potentiate native CRAC channels (Prakriya and Lewis, 2001), enhanced both WT Orai1 and E106D Orai1 currents with similar σ2/I slopes (Fig. 7). If the open probability of CRAC channels in 110 mM Ca2+ during the current decay is low (Po ≪ 0.5), the slope (σ2/I) provides a direct estimate of the unitary CRAC channel current (Prakriya and Lewis, 2006). If the Po were higher, as might be expected for the E106D Orai1 channels due to lack of inactivation, the true unitary conductance would, in fact, be larger by a factor of 1/(1 − Po) (Prakriya and Lewis, 2006). Thus, the close similarity in the unitary current argues that, at least under these conditions, the local [Ca2+] in the vicinity of the inactivation binding site should be comparable in E106D Orai1 and WT Orai1 channels.

Figure 7.

Noise analysis indicates that the unitary Ca2+ conductance of E106D Orai1-mediated CRAC channels is not diminished. (A) HEK293 cells overexpressing either WT Orai1 or E106D Orai1 were pretreated with TG and held at a constant potential of −100 mV to record ICRAC. Application of 110 mM [Ca2+]o causes a slow decline of ICRAC, likely due to slow inactivation (Zweifach and Lewis, 1995b). After the current reached a steady amplitude in 110 mM Ca2+, a low concentration (5 μM) of 2-APB was applied to enhance ICRAC. The average and the variance of the Ca2+ current was measured from 200-ms sweeps collected every 0.25 s. (B and C) Mean-variance analysis of ICRAC measured during the slow decline in 110 mM Ca2+ o and enhancement of ICRAC by 2-APB from the experiment shown in A. The data are well fit by straight lines with slopes of 7 fA (B) and 5 fA (C). (D) As with WT Orai1 currents, E106D Orai1 currents exhibit slow inactivation in the presence of 110 mM Ca2+ o. Application of a low concentration (5 μM) of 2-APB enhances E106D Orai1 currents. (E and F) Mean-variance analysis of ICRAC measured during the slow decline in 110 mM Ca2+ o and 2-APB potentiation from the experiment shown in D. Plots were fit with straight lines with slopes of 4 fA (E) and 7 fA (F).

Next, we considered the possibility that the mutations do not fundamentally disrupt the inactivation gating mechanism, but the enlargement of the pore results in a “leaky” inactivation gate that is unable to effectively block the passage of Ca2+. This hypothesis predicts that while the gate may be ineffective in preventing conduction of small ions such as Ca2+, larger ions should be more effectively prevented from flowing and therefore produce inactivation. The largest divalent cation that is permeable through CRAC channels and that is known to support some degree of fast inactivation in native CRAC channels is Ba2+ (Pauling crystal diameters of Ba2+ and Ca2+ are 2.75 and 1.98 Å, respectively) (Zweifach and Lewis, 1995a). WT Orai1 currents in 110 mM Ba2+ exhibited fast inactivation during hyperpolarizing pulses, confirming that Ba2+ binds to the inactivation site and triggers the conformational changes underlying fast inactivation (Fig. 8 A). In E106D Orai1 channels, currents in 110 mM Ba2+ exhibited greater inactivation than those in 110 mM Ca2+ (Fig. 8 B). However, the Ba2+ currents were also approximately twofold larger than currents carried by Ca2+, likely due to the larger unitary conductance of CRAC channels for Ba2+. As noted above, because the single-channel current amplitude directly influences the local ion concentration at the intracellular inactivation-binding site, increased inactivation of the Ba2+ currents may be simply a consequence of a higher local [Ba2+]i concentration. When the extracellular Ba2+ concentration was lowered to 12 mM so that current amplitudes in 110 mM Ca2+ and 12 mM Ba2+ were equivalent, no difference in the degree of inactivation in E106D Orai1 currents was observed (Fig. 8, C and D). These results argue that the loss of inactivation in E106D Orai1 is not simply a consequence of a leaky inactivation gate and suggest that diminished inactivation arises from alteration of the inactivation gating event itself.

Figure 8.

Fast inactivation of Ba2+ currents is also diminished by the E106D Orai1 mutation. (A) Ba2+ currents through WT Orai1 channels exhibit fast inactivation. A TG-pretreated cell was exposed to 110 mM Ca2+ and 110 mM Ba2+ solutions as indicated by the bars. Exposure to 110 mM Ba2+ results in a transient Ba2+ current that declines within ∼20 s, presumably due to CRAC channel depotentiation. The lower traces show selected current responses to hyperpolarizing voltage steps (to −100 mV, 300 ms) at the time points indicated by arrowheads in the upper plots. (B) Ba2+ currents through E106D Orai1 channels. Exposure to 110 mM Ba2+ results in a large Ba2+ current that gradually declines over tens of seconds. The lower traces show inactivation of selected currents at the time points indicated by the arrowheads in the upper plots. Note the presence of inactivation in the 110 mM Ba2+ trace. (C) In a different cell, when the external Ba2+ concentration was reduced to 12 mM to produce comparable Ca2+ and Ba2+ current amplitudes, no difference in fast inactivation was observed between the Ca2+ and Ba2+ currents. To prevent monovalent permeation, NMDG+ was used instead of Na+ in the 12 mM Ba2+ solution (see Materials and methods). (D) The extent of inactivation (1 − Iss/Ipeak) in currents arising from WT Orai1 and E106D Orai1 channels in Ca2+ and Ba2+.

A comparison of the effects of intracellular EGTA and BAPTA provides further evidence that the E106D Orai1 mutation disrupts the inactivation gating process. Previous work has shown that fast inactivation is slowed by intracellular dialysis with BAPTA, a rapid Ca2+ chelator, but not EGTA, a slow chelator. This has been attributed to BAPTA's ability to attenuate [Ca2+] in the immediate vicinity (<20 nm) of open CRAC channels (Neher, 1986). Therefore, we examined whether elevating the local [Ca2+]i around CRAC channels by substituting intracellular BAPTA with EGTA restores inactivation.

Intracellular dialysis with EGTA resulted in only a minor reappearance of fast inactivation in E106D Orai1 currents (Fig. 9 A). Hyperpolarization, which would be expected to increase the size of the unitary Ca2+ current, sped up the kinetics of current decay and increased the extent of inactivation to a small degree, consistent with the known Ca2+ dependence of the process (Fig. 9 C). At a membrane potential of −100 mV, the degree of inactivation (1− Iss/Ipeak) with intracellular EGTA in 110 mM Ca2+ o in E106D Orai1 currents was only 34 ± 3% compared with 72 ± 5% in WT Orai1-mediated currents. These results indicate that elevating the local [Ca2+] in the vicinity of the CRAC channels fails to restore inactivation. Together with the lack of change of the unitary Ca2+ conductance noted in the preceding sections, these results suggest that the loss of inactivation elicited by the Orai1 mutations arises from alteration of the inactivation mechanism itself.

Figure 9.

Intracellular dialysis of EGTA does not restore fast inactivation in E106D Orai1-expressing cells. (A) ICRAC measured from cells expressing E106D Orai1 during hyperpolarizing pulses to −100 mV in two different cells dialyzed with either BAPTA (8 mM) or EGTA (10 mM). Replacing intracellular BAPTA with EGTA restores fast inactivation only to a small degree. (B) In cells expressing WT Orai1, replacing intracellular BAPTA with EGTA strongly enhances fast inactivation. In A and B, cells with comparable peak currents were chosen to compare inactivation rates of cells dialyzed with EGTA or BAPTA. (C) Responses of one cell to a graded series of hyperpolarizing steps to the indicated potential from a holding potential of +30 mV with 10 mM EGTA in pipette.

DISCUSSION

The molecular identity of the CRAC channel pore and the mechanisms linking store depletion to channel activation remain unknown. The recent identification of Orai1 as a subunit of the CRAC channel pore and findings showing that large CRAC-like currents can be reconstituted from the ectopic expression of Orai1 and STIM1 open the way for investigation of the molecular mechanisms of ion permeation, gating, and regulation of CRAC channels (Peinelt et al., 2006; Prakriya et al., 2006; Vig et al., 2006a; Yeromin et al., 2006). Orai1 mutagenesis studies show that Glu 106 and Glu 190, located in TM1 and TM3, and three closely spaced aspartates in the TM1–TM2 linker influence Ca2+ selectivity and lanthanide block of CRAC channels (Prakriya et al., 2006; Vig et al., 2006a; Yeromin et al., 2006). In this study, we find that altering these acidic residues elicits complex effects, including an increase in Cs+ permeation, widening of the CRAC channel pore, and diminished Ca2+-mediated fast inactivation. The striking alterations in both permeation and gating by the point mutations corroborates the view that Orai1 is a component of the CRAC channel pore. However, it was surprising to find so many different properties affected, and an important question is whether these various effects are linked in some way or if they are independent. In light of recent evidence showing that permeation and gating are coupled in many types of channels, the gating effects revealed by the mutations suggest that CRAC channel gating is strongly influenced by the selectivity filter. In the sections that follow, we discuss the implications of these phenomena and possible underlying mechanisms.

Relationship between Cs+ Permeability and Pore Geometry

A key hallmark of CRAC channels is their unusually low permeability to Cs+ (PCs/PNa ∼ 0.1; Lepple-Wienhues and Cahalan, 1996; Kozak et al., 2002; Prakriya and Lewis, 2002). This is in contrast to Ca2+-selective L-type Cav channels, which readily pass Cs+ under DVF conditions (PCs/PNa ∼ 0.6; Hess et al., 1986). Similarly, the Ca2+-selective TRPV6 channel is also highly permeable to Cs+ (PCs/PNa of ∼0.5; Voets et al., 2001). A recent study provides a clue for the basis for the CRAC channel's unusually low Cs+ permeability. Whereas the L-type Cav and TRPV6 channels have relatively large pore diameters of ∼6.2 Å (Cataldi et al., 2002) and 5.4 Å (Voets et al., 2004), respectively, the narrowest region of the CRAC channel pore is only ∼3.9 Å (Prakriya and Lewis, 2006). Given that the atomic diameter of a naked Cs+ ion is ∼3.8 Å, this raised the possibility that the low permeability to Cs+ reflects steric hindrance to its permeation.

In the present study, we show that mutations of acidic residues that diminish Ca2+ selectivity and enhance Cs+ permeation cause significant widening of the pore. In particular the E106D and E190Q substitutions, which strongly elevate Cs+ permeation, increase the apparent pore diameter from ∼3.8 Å (WT Orai1) to 5.3 and 7.0 Å, respectively. It is important to note that these estimates reflect the dimensions of the pore when conducting monovalent ions and may differ under conditions of Ca2+ permeation. This is because as Ca2+ diffuses into the pore, its binding to the flexible carboxylate side chains of the Glu and Asp residues may provide the necessary countercharges to stabilize and alter the conformation of the selectivity filter in a manner analogous to the change in the conformation of the KcsA channel selectivity filter by the entry of K+ (Zhou and MacKinnon, 2003). Nevertheless, the profound alterations of Cs+ permeability and pore diameter by the mutations suggests that regardless of the precise side chain orientation of the carboxylates, the acidic residues examined here regulate ion selectivity by influencing the structural and architectural features of the CRAC channel pore.

At present, we do not know the structural basis of the substantial alterations in pore geometry caused by alterations of the acidic residues. If we assume that these residues are all arranged at a single locus within the selectivity filter, analogous to the EEEE locus of L- type Cav channels, then one possibility is that the location of the minimal pore diameter is at the position of the acidic residues themselves. In this paradigm, the Glu→Asp substitution widens the selectivity filter due to shortening of the side chains. Similarly, elimination of the Asp side chains could underlie the widening seen with the D110/112/114A substitutions. However, this argument does not readily explain the widening seen with the E190Q substitution, which does not alter the chain length.

A second possibility is that the acidic residues are not arranged at a single locus, but instead mediate multiple binding sites along the permeation pathway and contribute to differing extents to the apparent pore diameter. It has been proposed that the CRAC channel permeation pathway might contain multiple binding sites with the TM glutamate residues (E106 and E190) contributing sites within the pore and the D110/112 residues forming a site at the extracellular pore mouth (Vig et al., 2006a; Yeromin et al., 2006). If true, the large alteration in the apparent pore diameter seen with the E190Q substitution might suggest that this residue contributes most significantly to the apparent CRAC channel pore diameter.

A further explanation is that the narrowest part of the pore occurs not at the locus of the acidic residues themselves, but rather at a neighboring site in the ion conduction pathway, with the mutations triggering changes in geometry at this distal location. Although simplistic and speculative, this idea embodies the notion that there may be a barrier for ion permeation in series with the selectivity filter responsible for sculpting the unique hallmarks of the CRAC channel pore such as its low Cs+ permeability. Regardless of the exact mechanism, the increase in pore diameter and accompanying changes in key Ca2+-binding properties such as the kon and the voltage dependence of Ca2+ block collectively indicate that the mutations trigger complex changes in the tertiary structure of the selectivity filter with profound consequences for ion permeation, selectivity, and channel gating.

Ca2+ Block of Na+-ICRAC

Characterization of the kinetics and extent of Ca2+ block of Na+ currents indicates that the association rate of Ca2+ block of Na+ conduction through WT Orai1 channels is ∼4 × 106 M−1s−1. This is similar to the value found in the endogenous CRAC channels of Jurkat T cells (∼6 × 106 M−1s−1; Prakriya and Lewis, 2006). The measured pore diameter of 3.8 Å for channels arising from WT Orai1 is also very similar to that determined for the endogenous CRAC channels of Jurkat cells (dpore of 3.9 Å; Prakriya and Lewis, 2006). Together with similarities in the affinity of Ca2+ block of Na+-ICRAC (∼20 μM; Prakriya and Lewis, 2006; Prakriya et al., 2006) and of the voltage dependence of Ca2+ block (apparent valence of 0.78 in WT Orai1 channels vs. 0.71 in Jurkat T cell CRAC channels; Prakriya and Lewis, 2006), these findings indicate that the Ca2+ binding properties of the native CRAC channel pore in Jurkat T cells can be fully accounted for by Orai1, confirming the essential role of Orai1 as a key pore-forming subunit of the CRAC channel.

It was our expectation that the large reduction (>10-fold) in affinity of Ca2+ block of Na+-ICRAC caused by the E106D Orai1 substitution could be most simply explained by strong enhancement of the koff for Ca2+ binding. Contrary to this expectation, the kinetics of Ca2+ blockade revealed that the E106D Orai1 substitution lowers the kon ∼10-fold, with only a minor change in koff. This suggests that the mutation raises a rate-limiting barrier for Ca2+ entry to its pore-binding site. It is not known why the on-rate is reduced by the E106D Orai1 substitution, but one simple explanation is that, if as expected, Ca2+ ions interact with the sites in the CRAC channel in their dehydrated state, then the slower kon reflects the longer time needed for dehydration of Ca2+ before binding. The diameter of the selectivity filter may directly influence this by constraining how easily the charged residues compensate for the hydration of Ca2+.

The precise molecular composition of the CRAC channel pore is not well understood at this point. A recent study has proposed that TRPC channels may encode the CRAC channel pore with the Orai proteins mediating regulatory roles as nonpore forming β subunits (Liao et al., 2007). Although TRPC channels have been found to be store operated in some studies, the known differences in Ca2+ selectivity between TRPC channels and CRAC channels, the similarities between the pores of Orai1-mediated channels and native CRAC channels noted above, and the striking alterations in CRAC channel pore properties by Orai1 mutations shown here highlight important differences that are difficult to reconcile with the notion that TRPC channels underlie the CRAC channel pore.

Pore Mutations Affect CRAC Channel Inactivation

In the classical view of ion channels, permeation and gating are distinct processes arising from separate structures of the ion channel protein: a selectivity filter that discriminates among permeating ions and (usually) an intracellular steric gate that regulates ion conduction. Consistent with this model, the activation and inactivation gates of K+, Na+, and voltage-gated Ca2+ channels have traditionally been localized at the intracellular end of the pore, whereas the selectivity filters are localized at the extracellular pore mouth. In this paradigm, control of gating and permeation by distinct structures would presumably allow large conformational changes in the steric gate to occur without disrupting the favorable ion binding interactions in the selectivity filter required for ion selection.

A variety of recent observations indicate that this strictly modular channel organization, specifically, the assignment of all gating function to an intracellular steric gate, is inaccurate for many channels. For example, C-type inactivation in voltage-gated K+ channels arises not from blockade of ion conduction by an intracellular gate but from the subtle dynamic movements of the selectivity filter itself producing a nonconducting pore (Liu et al., 1996; Kiss et al., 1999). There is evidence that this form of gating may not be limited to inactivation; in the bacterial K+ channel KcsA, Blunck et al. (2006) recently report that the main determinant of channel opening is not the cytoplasmic steric gate mediated by the bacterial K+ channel's TM2 helix but by a gate located in the selectivity filter. Finally, in voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, a recent report proposes that Ca2+-mediated inactivation occurs from a “subtle tuning” of the selectivity filter that alters the affinity of the Ca2+ binding site into a “sticky” state, essentially trapping ions within the pore and stopping ion conduction (Babich et al., 2007; Olcese, 2007). Collectively, these and other studies suggest that the selectivity filter may directly participate in channel gating in several types of ion channels.

For CRAC channels, key aspects of the fast inactivation mechanism such as the identities of the Ca2+ binding sites, the nature of the inactivation gate, and whether inactivation occurs by a change in open probability or unitary Ca2+ conductance remain unknown. Past experiments have shown that the Ca2+ binding sites for fast inactivation are intracellular (BAPTA sensitive; Hoth and Penner, 1993; Zweifach and Lewis, 1995a; Fierro and Parekh, 1999). Given that the acidic residues examined here are critical determinants of ion selectivity and therefore likely to be located within the CRAC channel's selectivity filter, the loss of inactivation in the mutants points to alteration of the inactivation gating event, which could occur at the selectivity filter or at some other site that is strongly affected by the mutations. The mutations did not alter the requirement for store depletion for channel activation (Fig. S1) or the reorganization of Orai1 following store depletion (unpublished data), ruling out large perturbations in the overall structure of Orai1. In at least one mutant (E106D Orai1), the diminished inactivation does not appear to be from a decrease in the local [Ca2+]i around individual CRAC channels due to a decrease in the unitary conductance nor due to a “leaky” inactivation gate. Moreover, the mutations that cause the largest alterations in divalent and monovalent ion selectivity, such as those triggered by E106D and E190Q substitutions, show the most striking changes in fast inactivation (Fig. 6). The close correspondence between permeation and fast inactivation leads us to propose that the structural elements regulating these apparently distinct functional properties overlap.

Although it is too early to speculate on the precise nature of this coupling, two possibilities exist. First, ion binding within the selectivity filter of the CRAC channels may modulate the function of a distal (possibly intracellular) gate through an allosteric mechanism that is disrupted by the pore mutations. An alternate possibility is that the selectivity filter doubles also as the CRAC channel gate, so that modulation of ion conduction occurs not from the steric blockade of ion flow by an intracellular gate, but from the subtle rearrangement of the conformation of the selectivity filter itself.

The inactivation domains mediated by steric blockade of ion conduction diverge widely among ion channels. One well-studied mode of inactivation mediated by steric blockade occurs via the N-type or “ball and chain” mechanism in which an intracellular region behaves as a blocking particle to occlude ion conduction (Hoshi et al., 1990; Zagotta et al., 1990). The channel regions responsible for this type of inactivation range from the N-terminal regions in K+ channels to the I–II loop (linking repeats I and II) of Cav channels (Hoshi et al., 1990; Zagotta et al., 1990; Stotz et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2004). Examination of the Orai1 sequence does not reveal a region that can be obviously identified as an inactivation gate and our preliminary experiments suggest that deletion of the cytoplasmic N terminus and mutations in the C-terminal region do not alter fast inactivation (unpublished data). Therefore, we currently favor a model in which the selectivity filter also functions as the channel gate. If this latter possibility is true, conformational changes during gating events might be expected to result in subtle changes in ion selectivity and unitary conductance. More studies are needed to gain insight into such issues, and the resolution of Orai1 structure as well as measurements of single channel currents in patch recordings might make it possible to directly reveal possible links between permeation and channel gating in CRAC channels.

Supplemental Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. S. Feske for providing the IRES-eGFP WT Orai1 plasmid, and Drs. R.S. Lewis, S. Feske, A. Gross, and T. Hornell for helpful comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by a Scientist Development award (0630401Z) from the American Heart Association and National Institutes of Health grant NS057499 to M. Prakriya.

Angus C. Nairn served as editor.

Abbreviations used in this paper: 2-APB, 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate; CRAC, calcium release-activated Ca2+; DVF, divalent free; NMDG, N-methyl-d-glucamine; TG, thapsigargin; TM, transmembrane; TRP, transient receptor potential; WT, wild type.

References

- Babich, O., V. Matveev, A.L. Harris, and R. Shirokov. 2007. Ca2+-dependent inactivation of Cav1.2 channels prevents Gd3+ block: does Ca2+ block the pore of inactivated channels? J. Gen. Physiol. 129:477–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blunck, R., J.F. Cordero-Morales, L.G. Cuello, E. Perozo, and F. Bezanilla. 2006. Detection of the opening of the bundle crossing in KcsA with fluorescence lifetime spectroscopy reveals the existence of two gates for ion conduction. J. Gen. Physiol. 128:569–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnashev, N., A. Villarroel, and B. Sakmann. 1996. Dimensions and ion selectivity of recombinant AMPA and kainate receptor channels and their dependence on Q/R site residues. J. Physiol. 496:165–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldi, M., E. Perez-Reyes, and R.W. Tsien. 2002. Differences in apparent pore sizes of low and high voltage-activated Ca2+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 277:45969–45976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, T.M., D.J. Adams, and B. Hille. 1980. The permeability of the endplate channel to organic cations in frog muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 75:469–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske, S., M. Prakriya, A. Rao, and R.S. Lewis. 2005. A severe defect in CRAC Ca2+ channel activation and altered K+ channel gating in T cells from immunodeficient patients. J. Exp. Med. 202:651–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske, S., Y. Gwack, M. Prakriya, S. Srikanth, S.H. Puppel, B. Tanasa, P.G. Hogan, R.S. Lewis, M. Daly, and A. Rao. 2006. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 441:179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierro, L., and A.B. Parekh. 1999. Fast calcium-dependent inactivation of calcium release-activated calcium current (CRAC) in RBL-1 cells. J. Membr. Biol. 168:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D., and Z. Lu. 2000. Mechanism of cGMP-gated channel block by intracellular polyamines. J. Gen. Physiol. 115:783–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess, P., J.B. Lansman, and R.W. Tsien. 1986. Calcium channel selectivity for divalent and monovalent cations. Voltage and concentration dependence of single channel current in ventricular heart cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 88:293–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi, T., W.N. Zagotta, and R.W. Aldrich. 1990. Biophysical and molecular mechanisms of Shaker potassium channel inactivation. Science. 250:533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoth, M., and R. Penner. 1993. Calcium release-activated calcium current in rat mast cells. J. Physiol. 465:359–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., S. Ghosh, D.A. Nunziato, and G.S. Pitt. 2004. Identification of the components controlling inactivation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Neuron. 41:745–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, L., J. LoTurco, and S.J. Korn. 1999. Contribution of the selectivity filter to inactivation in potassium channels. Biophys. J. 76:253–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, J.A., H.H. Kerschbaum, and M.D. Cahalan. 2002. Distinct properties of CRAC and MIC channels in RBL cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:221–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepple-Wienhues, A., and M.D. Cahalan. 1996. Conductance and permeation of monovalent cations through depletion-activated Ca2+ channels (ICRAC) in Jurkat T cells. Biophys. J. 71:787–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R.S. 1999. Store-operated calcium channels. Adv. Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 33:279–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R.S. 2001. Calcium signaling mechanisms in T lymphocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:497–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y., C. Erxleben, E. Yildirim, J. Abramowitz, D.L. Armstrong, and L. Birnbaumer. 2007. Orai proteins interact with TRPC channels and confer responsiveness to store depletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:4682–4687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.M., and D.J. Adams. 2001. Ionic selectivity of native ATP-activated (P2X) receptor channels in dissociated neurones from rat parasympathetic ganglia. J. Physiol. 534:423–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., M.E. Jurman, and G. Yellen. 1996. Dynamic rearrangement of the outer mouth of a K+ channel during gating. Neuron. 16:859–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, J.C., W.I. Dehaven, J.T. Smyth, B. Wedel, R.R. Boyles, G.S. Bird, and J.W. Putney Jr. 2006. Large store-operated calcium selective currents due to co-expression of Orai1 or Orai2 with the intracellular calcium sensor, Stim1. J. Biol. Chem. 281:24979–24990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher, E. 1986. Concentration profiles of intracellular calcium in the presence of a diffusible chelator. Experimental Brain Research Series. 14:80–96. [Google Scholar]

- Olcese, R. 2007. And yet it moves: conformational states of the Ca2+ channel pore. J. Gen. Physiol. 129:457–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh, A.B., and J.W. Putney Jr. 2005. Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol. Rev. 85:757–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partiseti, M., F. Le Deist, C. Hivroz, A. Fischer, H. Korn, and D. Choquet. 1994. The calcium current activated by T cell receptor and store depletion in human lymphocytes is absent in a primary immunodeficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 269:32327–32335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peinelt, C., M. Vig, D.L. Koomoa, A. Beck, M.J. Nadler, M. Koblan-Huberson, A. Lis, A. Fleig, R. Penner, and J.P. Kinet. 2006. Amplification of CRAC current by STIM1 and CRACM1 (Orai1). Nat. Cell Biol. 8:771–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya, M., and R.S. Lewis. 2001. Potentiation and inhibition of Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channels by 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate (2-APB) occurs independently of IP3 receptors. J. Physiol. 536:3–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya, M., and R.S. Lewis. 2002. Separation and characterization of currents through store-operated CRAC channels and Mg2+-inhibited cation (MIC) channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 119:487–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya, M., and R.S. Lewis. 2003. CRAC channels: activation, permeation, and the search for a molecular identity. Cell Calcium. 33:311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya, M., and R.S. Lewis. 2006. Regulation of CRAC channel activity by recruitment of silent channels to a high open-probability gating mode. J. Gen. Physiol. 128:373–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya, M., S. Feske, Y. Gwack, S. Srikanth, A. Rao, and P.G. Hogan. 2006. Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature. 443:230–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotz, S.C., J. Hamid, R.L. Spaetgens, S.E. Jarvis, and G.W. Zamponi. 2000. Fast inactivation of voltage-dependent calcium channels. A hinged-lid mechanism? J. Biol. Chem. 275:24575–24582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig, M., A. Beck, J.M. Billingsley, A. Lis, S. Parvez, C. Peinelt, D.L. Koomoa, J. Soboloff, D.L. Gill, A. Fleig, et al. 2006. a. CRACM1 multimers form the ion-selective pore of the CRAC channel. Curr. Biol. 16:2073–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig, M., C. Peinelt, A. Beck, D.L. Koomoa, D. Rabah, M. Koblan-Huberson, S. Kraft, H. Turner, A. Fleig, R. Penner, and J.P. Kinet. 2006. b. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science. 312:1220–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets, T., A. Janssens, G. Droogmans, and B. Nilius. 2004. Outer pore architecture of a Ca2+-selective TRP channel. J. Biol. Chem. 279:15223–15230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets, T., J. Prenen, A. Fleig, R. Vennekens, H. Watanabe, J.G. Hoenderop, R.J. Bindels, G. Droogmans, R. Penner, and B. Nilius. 2001. CaT1 and the calcium release-activated calcium channel manifest distinct pore properties. J. Biol. Chem. 276:47767–47770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeromin, A.V., S.L. Zhang, W. Jiang, Y. Yu, O. Safrina, and M.D. Cahalan. 2006. Molecular identification of the CRAC channel by altered ion selectivity in a mutant of Orai. Nature. 443:226–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagotta, W.N., T. Hoshi, and R.W. Aldrich. 1990. Restoration of inactivation in mutants of Shaker potassium channels by a peptide derived from ShB. Science. 250:568–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.L., A.V. Yeromin, X.H. Zhang, Y. Yu, O. Safrina, A. Penna, J. Roos, K.A. Stauderman, and M.D. Cahalan. 2006. Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca2+ influx identifies genes that regulate Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:9357–9362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y., and R. MacKinnon. 2003. The occupancy of ions in the K+ selectivity filter: charge balance and coupling of ion binding to a protein conformational change underlie high conduction rates. J. Mol. Biol. 333:965–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweifach, A., and R.S. Lewis. 1993. Mitogen-regulated Ca2+ current of T lymphocytes is activated by depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 90:6295–6299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweifach, A., and R.S. Lewis. 1995. a. Rapid inactivation of depletion-activated calcium current (ICRAC) due to local calcium feedback. J. Gen. Physiol. 105:209–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweifach, A., and R.S. Lewis. 1995. b. Slow calcium-dependent inactivation of depletion-activated calcium current. Store-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 270:14445–14451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.