Abstract

ω3 fatty acid desaturases are the enzymes responsible for the synthesis of trienoic fatty acids in plants. These enzymes have been mainly investigated using molecular, biochemical, and genetic approaches but very little is known about their subcellular distribution in plant cells. In this work, the precise subcellular localization of the ω3 desaturase FAD7 was elucidated by immunofluorescence and immunogold labeling using a monospecific GmFAD7 polyclonal antibody in soybean (Glycine max) photoautotrophic cell suspension cultures. Confocal analysis revealed the localization of the GmFAD7 protein within the chloroplast; i.e. signals from FAD7 and chlorophyll autofluorescence showed specific colocalization. Immunogold labeling was pursued on cryofixed and freeze-substituted samples for convenient preservation of antigenicity and ultrastructure of membrane subcompartments. Our data revealed that the FAD7 protein was preferentially localized in the thylakoid membranes. Biochemical fractionation of purified chloroplasts and western analysis of the subfractions further confirmed these results. These findings suggest that not only the envelope, but also the thylakoid membranes could be sites of lipid desaturation in higher plants.

Trienoic (TA) and dienoic fatty acids represent as much as 70% of total fatty acids from leaf or root lipids (Douce et al., 1990). They influence the function of biological membranes by maintaining their appropriate fluidity. Apart from this key role in cell function, TAs also serve as precursors of important plant hormones like jasmonates (JAs) that are involved in defense signaling against pathogen attack, the wound response, and plant development and adaptation to environmental stress (for review, see Iba, 2002; Schaller et al., 2005). Desaturase activity responsible for polyunsaturated fatty acid production was initially detected in microsomal and plastid preparations of various plant tissues (Ohlrogge and Browse, 1995). However, the difficulties in purifying these enzymes by biochemical methods hampered their identification. The molecular characterization of a collection of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) mutants defective in membrane lipid unsaturation allowed for the identification of desaturase genes, providing specific knowledge about their number, substrate specificity, and predicted location (Wallis and Browse, 2002). Thus, TAs are synthesized from dienoics by the activity of several ω3 desaturases that are localized in two different cell compartments: FAD3 is specific of the endoplasmic reticulum while FAD7 and its cold-inducible isozyme, FAD8, are plastid specific (Wallis and Browse, 2002). However, with the exception of one plastidial enzyme, the stearoyl acyl-carrier protein (ACP) desaturase FAB2, which is the only soluble desaturase isolated up to now, no detailed studies investigating the activity and precise localization of these enzymes were performed mainly due to the difficulties in developing purification methods, the absence of specific antibodies, or in performing enzymatic analyses for membrane-bound desaturases (Dyer et al., 2001). Heterologous expression studies in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) have proven successful for the analysis of posttranscriptional regulation and activity of endoplasmic reticulum ω6 and ω3 desaturases (FAD2 and FAD3; Dyer et al., 2001). However, these studies are not suited for the analysis of plastid desaturases as they require electron transport chains from the chloroplast (Schmidt and Heinz, 1990a).

Relatively little is known about the subcellular localization of fatty acid desaturases in plants, largely due to the lack of monospecific antibodies against them. In the only previous study concerning this question, immunocytological evidence of the subcellular localization of FAD2 and FAD3, the ω6 and ω3 desaturases of the reticulum, respectively, was obtained by developing an epitope-tagging scheme that allowed the immunological detection of transiently expressed FAD2 and FAD3 proteins in plant suspension-cultured cells (Dyer and Mullen, 2001). There are no evidences of the subcellular localization of the plastid desaturases, to our knowledge. In cyanobacteria, prokaryotic ancestors of plants, immunogold studies provided evidence that the Δ6, Δ9, Δ12, and ω3 desaturases were located in the regions of both cytoplasmic and thylakoid membranes (Mustardy et al., 1996). However, to our knowledge, in plants, there are no clear evidences showing which proportion of the total desaturase activity in the chloroplast takes place in each specific membrane. In a series of elegant experiments, Schmidt and Heinz (1990b) obtained a membrane fraction with high desaturase activity. This fraction was a mixture of thylakoid and envelope membranes. Further purification of this fraction resulted in envelope membranes that retained high and stable oleate desaturase activity while it was more difficult to reproduce linoleic acid desaturation (Schmidt and Heinz, 1990b). More recently, proteomic analysis of the chloroplast envelope identified both FAD6 and FAD7 desaturases as part of the proteins that were detected in inner envelope-enriched fractions (Ferro et al., 2003; Froehlich et al., 2003). However, other components of the machinery for fatty acid biosynthesis like the ACP, which is a cofactor of acyl-ACP:glycerol-3-P acyltransferase, are bound to the thylakoid membranes (Slabas and Smith, 1988), suggesting that thylakoids could also be sites of fatty acid biosynthesis and desaturation in plants.

We have recently described the obtention of a monospecific polyclonal antibody against the plastid ω3 desaturase FAD7 from soybean (Glycine max; Collados et al., 2006). We used this antibody as a tool for immunofluorescence, immunogold labeling, and biochemical fractionation essays to precisely determine the subcellular localization of the FAD7 ω3 desaturase in soybean cultured cells. This simple and convenient culture system of photosynthetic cells displays most of the structural and functional characteristics of mesophyll cells (Rogers et al., 1987) and has proven successful for different studies of the chloroplast function. Our results indicate that the FAD7 protein was detected preferentially in the thylakoid membranes, suggesting that these membranes could be sites of lipid desaturation in higher plants. These findings provide new information concerning the role of plant fatty acid desaturases, not only in the lipid synthesis metabolism but also in the environmental stress response and in plant defense-signaling pathways.

RESULTS

Subcellular Localization of GmFAD7 by Immunofluorescence

With the purpose to develop a specific immunobased method for the determination of the precise subcellular localization of the plastid ω3 fatty acid desaturase FAD7, we used our monospecific antibody raised against the GmFAD7 protein. The obtention and properties of this antibody have been already described in a previous article of our group (Collados et al., 2006). In brief, we raised an antiserum against a synthetic oligopeptide corresponding to residues 69 to 84 of the deducted mature FAD7 protein. This region was specific for FAD7 and presented very low homology with the microsomal FAD3 protein and the cold-inducible FAD8 plastid enzyme. The GmFAD7 antiserum reacted with a polypeptide of approximately 39 kD, which corresponds well with the predicted Mr of the GmFAD7 protein (Collados et al., 2006).

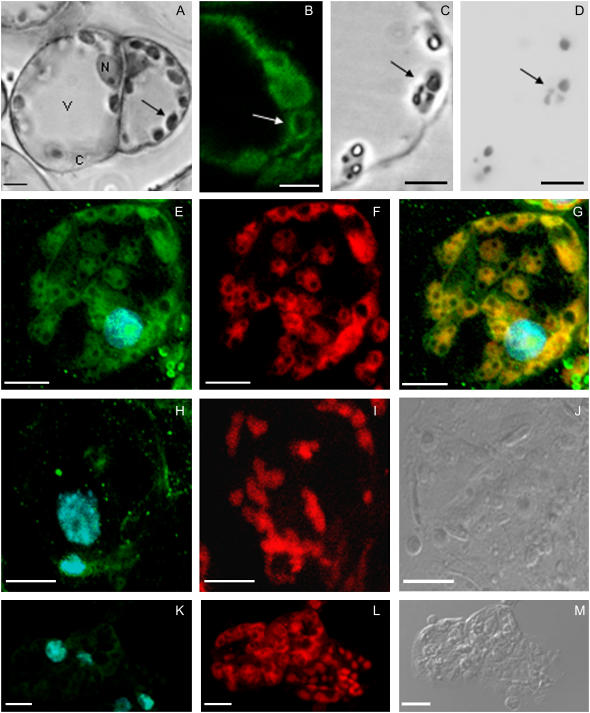

The structural organization of soybean photosynthetic cells, as visualized in toluidine blue-stained semithin sections (Fig. 1A), was similar to that of mesophyll cells from young leaves. They showed a large and central cytoplasmic vacuole, numerous chloroplasts distributed along the peripheral layer of cytoplasm, and an ellipsoid nucleus (Fig. 1A). Most chloroplasts contained large granules that appeared as clear inclusions in I2KI stained sections observed under phase contrast (Fig. 1C) or visualized under bright field (Fig. 1D). The content of these inclusions was revealed by iodide-based cytochemical methods as starch (Fig. 1, C and D).

Figure 1.

Subcellular localization of GmFAD7 by immunofluorescence. A, Structural organization of soybean photosynthetic cell cultures. Historesin semithin sections after toluidine blue staining. Vacuole (V), cytoplasm (C), nucleus (N), and chloroplasts (arrows). B, Anti-GmFAD7 inmunofluorescence showing green positive signal in rounded cytoplasmic structures (arrows). C and D, Structural organization of a similar cytoplasmic area than in B; historesin semithin sections visualized under phase contrast after I2IK staining for starch (C) with chloroplasts containing clear starch deposits (arrows). D, Starch deposits revealed as dark inclusions in the chloroplasts by iodide-based cytochemistry, observed under bright field. E to M, Confocal laser microscopy observations of the same vibratome sections. The images represent projections of 15 to 20 optical sections. E, Inmunofluorescence with anti-GmFAD7 antibody (green) in soybean photosynthetic cells. Nuclear DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). F, Autofluorescence from chlorophyll (red). G, Overlap of autofluorescence from chlorophyll (red) with anti-GmFAD7 immunofluorescence (green). Yellowish-orange colors indicate signal colocalization. The image shows the chloroplast localization of GmFAD7. H, Control with anti-GmFAD7 antibody blocked with synthetic peptide. Control showed no labeling. Nuclei are visualized by DAPI (blue; I) autofluorescence from chlorophyll. J, Differential interference contrast image of the corresponding section. K, Control without anti-GmFAD7. Nuclei are visualized by DAPI (blue). L, Autofluorescence from chloroplyll. M, Differential interference contrast image of the corresponding section. Bars in figures B to D represent 5 μm; bars in A and E to M represent 10 μm.

Immunofluorescence experiments with the anti-GmFAD7 on soybean cells (Fig. 1, B and E) provided specific signals as intense green fluorescence, in defined peripheral cytoplasmic oval spots (Fig. 1, B and E). Labeling was not found in the nucleus, which was revealed by 4,6-diamidine-2-phenylindol (DAPI) with an intense blue fluorescence, or in the vacuole, which appeared as a large dark central area (Fig. 1, B and E). The pattern of distribution of the immunofluorescence labeling obtained with the anti-GmFAD7 and its comparison with the structural organization of the soybean cells was strongly attributable to localization of the GmFAD7 protein in the chloroplast. To identify the chloroplasts in the same sections used for immunofluorescence, confocal images with excitation lines specific for autofluorescence emission of chlorophyll were obtained and collected as defined red signals (Fig. 1, F, I, and L). The overlay of both green and red signals showed the localization of the GmFAD7 antigen as a yellow signal in the chloroplast (Fig. 1G). Almost no individual green or red small spots were observed in the merged images (Fig. 1G), indicating that the colocalization was almost complete. The dark spots observed inside the chloroplasts most probably correspond to the starch deposits described above and revealed by specific cytochemistry (Fig. 1, C and D).

The specificity of the anti-GmFAD7 antibody in the immunofluorescence assays was supported by the immunodepletion experiments. These controls were performed by preincubating the anti-GmFAD7 antibodies with the oligopeptide used as immunogen to raise them. Immunofluorescence assays with the preblocked anti-GmFAD7 antibodies abolished the green signal in intact chloroplasts on soybean cells, as identified by their chlorophyll autofluorescence (red signal; Fig. 1, H–J). These results provided additional support to the specificity of the antibodies that were specifically titrated away by this known protein fragment. No significant labeling was obtained in control experiments with the preimmune serum (data not shown) or in the absence of anti-GmFAD7 antibody (Fig. 1, K–M).

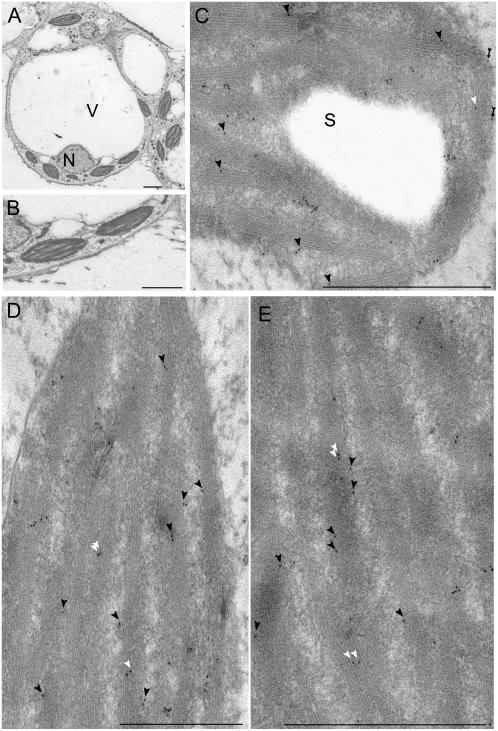

Ultrastructural Localization of GmFAD7 by Immunogold Labeling

The only previous report concerning the subcellular localization of two integral membrane-bound plant fatty acid desaturases was elucidated by immunofluorescence microscopic analyses of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) suspension cells transiently transformed with different epitope-tagged versions of the reticular FAD2 and FAD3 enzymes (Dyer and Mullen, 2001). To our knowledge, no data are available for plastid desaturases like FAD7. Moreover, the resolution of a confocal microscope and immunofluorescence studies could not inform about the precise localization of the GmFAD7 antigen inside the different chloroplast subcompartments. To precisely define the subcellular distribution of the GmFAD7 protein, electron microscopy immunogold labeling was performed (Fig. 2). An accurate electron microscopy immunolocalization of membrane-associated antigens requires specific sample processing methods to preserve the chemical integrity, antigenic reactivity, and membrane ultrastructure, which are highly affected by some chemically fixing and most dehydrating procedures. Cryofixation and freeze substitution have been reported as very convenient processing methods for immunogold assays of membrane-associated antigens in plant cells (Risueño et al., 1998; Seguí-Simarro et al., 2003, 2005; for review, see Koster and Klumperman, 2003). Our results showed that the cryoprocessing and freeze-substitution method followed by low-temperature embedding in an acrylic resin, was fully adequate for soybean cells, which displayed an excellent ultrastructural preservation of the different subcellular compartments, including chloroplasts and thylakoid membranes (Fig. 2, A and B). Immunogold labeling with the GmFAD7 antiserum was mostly found decorating the chloroplasts, labeling appearing either as isolated or clustered particles (Fig. 2, C–E). Some labeling could be found on the chloroplast envelope (Fig. 2C), but most gold particles were observed preferentially over thylakoid membranes, whereas the stroma appeared mostly free of labeling (Fig. 2, C–E). Interestingly, most part of the gold particles that appeared in the thylakoid membranes were located in regions that had access to the stroma (black arrowheads in Fig. 2, C–E), while only a low proportion of them (18% of the gold particles over thylakoids) were found inside the grana stacks (white arrowheads in Fig. 2, C–E). A few gold particles could be found over the rest of the cytoplasm, constituting the nonspecific background provided by the antibody. Immunogold control experiments replacing the first antibody by the preimmune serum or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) did not provide any significant labeling (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Anti-GmFAD7 immunogold labeling on soybean photosynthetic cell cultures. Ultrathin Lowicryl sections. A, General view of soybean cells. B, General view of chloroplasts. C, D, and E correspond to sections showing immunogold labeling distribution. Gold particles were localized in envelope (C; black arrow) and thylakoid membranes (C, D, and E; arrowheads). Difference is shown between those particles located in the thylakoid in regions that had access to the stroma (black arrowheads) and those located inside the grana stacks (white arrowheads). V, Vacuole; N, nucleus; R, stroma; T, thylakoid membranes; S, starch granules. Bars in A and B represent 0.5 μm, and in C, D, and E represent 200 nm.

To assess the results of the immunogold assays, quantification studies of the labeling density as the number of gold particles per area unit were performed over the chloroplasts and over other cytoplasmic regions where no presence of the protein was expected, as demonstrated by the immunofluorescence and previous western results. The quantification results revealed a labeling density in the chloroplasts of 17.3 ± 3.8 particles/μm2. This value was much higher than in the rest of the cellular regions, where a few isolated particles could be found, being the mean labeling density, as estimated background less than 5% of the quantified signal in the chloroplasts. The possibility that scarce cytoplasmic particles could correspond to a small subset of the newly formed protein in transit to the chloroplast, only detected with the highest sensitivity of the immunogold labeling technique, could not be excluded. The labeling densities obtained in this study are within the range of those obtained for other chloroplast integral membrane proteins (Bernal et al., 2007) and even for cyanobacterial acyl-lipid desaturases (Mustardy et al., 1996), indicating that the freeze-substitution and cryoembedding method used for the processing of samples and the immunogold technique were appropriate to preserve FAD7 antigen and its reactivity with the antibody used. More difficult is to assess whether the labeling densities reflect the relative abundance of the FAD7 protein in the cell. Nevertheless, our data in soybean (Collados et al., 2006) or those previously reported in Arabidopsis (Matsuda et al., 2005) suggest that the control mechanism of FAD7 is not based in the control of its abundance but on its stability and specifical activation through mechanisms that remain unknown.

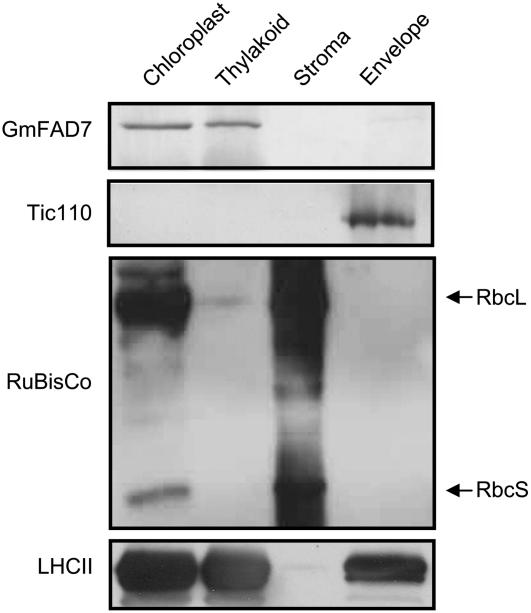

Biochemical Fractionation Studies for Subcellular FAD7 Protein Localization

To complete the subcellular localization study and to obtain additional information about the distribution of FAD7 in the different chloroplast subcompartments, we performed western-blot experiments on purified plastid subfractions (i.e. envelope membranes, stroma, and thylakoid). To purify plastid subfractions, Percoll-purified intact chloroplasts were lyzed in hypotonic medium and the three fractions were separated on a Suc gradient. The results obtained from the western-blot analysis of the purified fractions are shown in Figure 3. Several antibodies were used as specific markers of the different chloroplast subfractions. The Tic 110 protein was used as a specific envelope marker (Jackson et al., 1998). Antibodies against the light-harvesting complex II (LHCII) antenna protein, one of the components of PSII, were used for thylakoid membrane validation. Rubisco, the major stroma protein, was used as a marker of this chloroplast subfraction. As shown in Figure 3, the Tic 110 protein was only detectable in the envelope fraction while it was hardly visible in any of the other fractions. Tic 110 was not detectable in chloroplasts probably because its low abundance with respect to other plastid proteins. Rubisco was present in chloroplasts and stroma fractions while it was almost undetectable in the other fractions, indicating that the fractionation procedure was correct. The LHCII, which is a major thylakoid protein, was highly enriched in the thylakoid fractions as expected (Fig. 3). A significant amount was also detected in the envelope fraction (Fig. 3). The presence of LHCII in envelope fractions has been reported as a contaminant even in very pure preparations used for proteomic studies (see Ferro et al., 2003). However, we cannot discard that a part of this LHCII pool found repeatedly in envelope preparations could reflect a certain pool of LHCII in transit through its import route to the thylakoid. Being the most likely source of membrane contamination of the purified envelope fraction, thylakoid cross contamination was precisely assessed. Chlorophyll being the most conspicuous thylakoid component, we analyzed the presence of this pigment in the envelope membrane preparations. On a protein basis, the ratio of chlorophyll content detected in the purified envelope and thylakoid membranes was 1:25. This value is within the range reported by other groups during the isolation of envelope membranes for proteomic studies (Ferro et al., 2003; Froehlich et al., 2003). According to this, we can estimate thylakoid cross contamination of envelope membranes between 5% to 10%, depending on the preparations. This result indicated that the envelope fraction was highly pure. Interestingly, when the antibody against the GmFAD7 protein was tested, the major amount of FAD7 protein was detected in the thylakoid membranes while very low amounts were detectable in the envelope fractions (Fig. 3). No FAD7 protein was detected in the stroma fraction. These results further confirmed the results obtained by immunogold labeling, indicating that the FAD7 ω3 plastid desaturase is preferentially located in the thylakoid membrane.

Figure 3.

GmFAD7 protein distribution in chloroplast subfractions. Percoll-purified intact chloroplasts were lyzed and subjected to Suc gradient fractionation into envelope, stroma, and thylakoid fractions. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted against the GmFAD7 antibody and antibodies specific of each chloroplast subcompartment. Anti-Tic110 was specific of the envelope membranes, Rubisco was specific of the stroma, and the anti-LHCII was used as marker of the thylakoid membranes. 19, 16, 12.5, and 19 μg of total proteins from purified chloroplasts, thylakoids, stroma, and envelope fractions, respectively, were loaded per lane.

DISCUSSION

The absence of monospecific antibodies has made the development of immunobased methods for characterizing the subcellular localization of plant desaturase enzymes difficult. To date, in the only study in which this kind of approach was made, to our knowledge, the subcellular (reticular) localization of FAD2 and FAD3 desaturases was elucidated by immunofluorescence microscopic analysis of tobacco cultured cells transiently transformed with different epitope-tagged versions of both enzymes (Dyer and Mullen, 2001). In this study we provide in situ molecular evidence for the subcellular localization of the FAD7 ω3 desaturase in the plastids, revealed by immunofluorescence confocal analysis. This result is in agreement with the presence in its genomic sequence of a plastid transit peptide (Yadav et al., 1993) and the detection of desaturase activity responsible of polyunsaturated fatty acid production in plastid preparations of several plant tissues (Ohlrogge and Browse, 1995). However, the level of resolution of the immunofluorescence signals does not allow visualizing precisely the localization within the different chloroplast subcompartments of plastid proteins. Chloroplast is one of the most complex organelles in terms of ultrastructure, comprising three main different subcompartments: outer and inner envelope, stroma, and thylakoid. To precisely determine the subchloroplast location of GmFAD7, immunogold labeling assays were conducted using our specific anti-GmFAD7 antibody (Collados et al., 2006). Our results revealed that even if some labeling was detected in the envelope, a well-defined and specific immunogold signal was preferentially found in the thylakoid membranes. Furthermore, the biochemical fractionation of chloroplast subfractions (envelope, stroma, and thylakoids) and western-blot analysis using the GmFAD7 antibody together with specific fraction markers also revealed that the major amount of FAD7 protein was detected in the thylakoid membranes. These results suggest a dual localization of the FAD7 protein within the chloroplast and provide experimental evidence of its presence in the thylakoid. The elucidation of the distribution within the chloroplast of the different desaturase activities has been a subject of study for many years. Schmidt and Heinz (1990b) successfully obtained chloroplast membrane preparations (mixture of envelope and thylakoid membranes) that retained desaturase activity. Further fractionation of these preparations resulted in envelope membranes that retained high and stable oleate desaturase activity while it was more difficult to retain linoleic acid desaturation (Schmidt and Heinz, 1990b), making it very difficult to establish the distribution of ω3 desaturase activity in the chloroplast. Recent proteomic studies detected both ω6 and ω3 desaturases FAD6 and FAD7, respectively, among the proteins present in the inner chloroplast envelope (Ferro et al., 2003; Froehlich et al., 2003). Our data do not contradict the presence of a discrete amount of FAD7 protein in the chloroplast envelope, as reported by proteome analysis in Arabidopsis. In fact, we have detected gold particles in the envelope (Fig. 2C) and a slight but visible band was observed repeatedly in the western blot of purified envelope fractions (Fig. 3). However, both immunogold labeling and biochemical fractionation detected the major amount of FAD7 protein in the thylakoid membranes, indicating this preferential location in the chloroplast. Other enzymes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis have also been found associated to the thylakoid membrane. This is the case of the ACP, necessary for fatty acid biosynthesis and cofactor of the ACP:glycerol-3-P acyltransferase (Slabas and Smith, 1988). However, the strongest support to the presence in the thylakoid of the ω3 desaturase FAD7 comes from the immunogold localization of desaturases in cyanobacteria, prokaryotic ancestors of plants, which revealed that the Δ6, Δ9, Δ12, and ω3 desaturases were located in the regions of both cytoplasmic and thylakoid membranes (Mustardy et al., 1996). Our results suggest that this dual localization would have been conserved during evolution.

The presence in the thylakoid of FAD7 suggests that thylakoid membranes could be sites of TA fatty acid production in plants. In the chloroplast, the major reservoir of polyunsaturated fatty acids are the galactolipids present in the thylakoid membranes. In fact, they represent about 70% to 80% of the total amount of lipids in the chloroplast. Interestingly, our results indicate that the ω3 desaturase responsible for TA fatty acid production in the plastid is preferentially located in the same membrane where its product (18:3) is accumulated. In that sense, fatty acid desaturases need electron donors for their function. In the plastids, reduced ferredoxin provides the electrons necessary for FAD6 and FAD7 activity (Schmidt and Heinz, 1990a). Alternatively, several electron paramagnetic resonance signals, corresponding to iron-sulfur clusters, semiquinones, or flavins were detected in envelope preparations and proposed as components of an alternative electron transport chain that would facilitate electrons to the desaturases in the envelope (Jäger-Vottero et al., 1997). However, no specific components of these chains have ever been isolated or unambiguously identified. In principle, there would be no constraint for ferredoxin to donate its electrons to the desaturases present in the envelope. Similarly, our immunogold results suggest that most part of the FAD7 protein detected in the thylakoid is located in regions that have access to the stroma and thus are also accessible to ferredoxin. In fact, our results place the desaturase in close vicinity with its major electron donor (ferredoxin), making it unnecessary to invoke the presence of any other alternative electron carriers.

Another situation in which the thylakoidal localization of FAD7 should be relevant is related with the implication of this enzyme in the biosynthesis of JAs. JA was shown to be synthetized in the plastids from linolenic acid (18:3). Linolenic acid is first oxygenated by lipoxygenase (LOX) to yield 13(S)-hydroxyperoxy linolenic acid. Further cyclization is achieved by the consecutive action of two enzymes, namely, allene oxide synthase and allene oxide cyclase (Vick and Zimmerman, 1979; Schaller et al., 2005). There are evidences that either free fatty acids or fatty acids esterified to membrane lipids could be substrates for LOX; a soybean 13-LOX has been shown to act on polyunsaturated fatty acids esterified to neutral membrane lipids (Fuller et al., 2001; Feussner and Wasternack, 2002). In fact, it was shown in Arabidopsis that most 12-oxophytodienoic acid (an intermediate of jasmonic acid synthesis) was bound to the sn-1 position of monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (Stelmach et al., 2001). It has been proposed that these differences could contribute, with temporal differentiation of activity, to an orchestration of the formation of hydroxyl PUFAs (Liavonchanka and Feussner, 2006). In addition, proteomic studies in Arabidopsis have identified allene oxide synthase (At5g42650.1) and two isoforms of the allene oxide cyclase family (At3g25760.1 and At3g25770.1) as components of the thylakoid proteome as thylakoid peripheral proteins at the stromal side (Peltier et al., 2004; accessible via Plant Proteome DataBase). The preferential localization within the thylakoid of the GmFAD7 protein, as evidenced with our results, is consistent with a similar location of these enzymes that are at the early beginning of JA biosynthetic pathway. Altogether, these data suggest that in addition to the envelope, thylakoid membranes should play a role in JA synthesis and thus in plant defense-signaling responses where oxylipins like JA are involved.

In conclusion, the results presented in this article provide experimental evidence for the thylakoidal localization of FAD7 in the plastids. These data strongly suggest that thylakoid membranes could be sites of lipid desaturation in plants as it seems to be the case in cyanobacteria. These findings provide new information concerning the role of plant fatty acid desaturases, not only in the lipid synthesis metabolism but also in the environmental stress response and in plant defense-signaling pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Photosynthetic cell suspensions from soybean (Glycine max var. Corsoy) SB-P line were grown as described by Rogers et al. (1987) with some modifications (Alfonso et al., 1996). Liquid cultures were grown in KN1 medium with a supplement of 1% Suc under continuous light (30 ± 5 μE m−2 s−1) and an atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 24°C on a rotatory shaker at 110 rpm. For immunolocalization experiments, soybean cells were grown in 1.5% (w/v) agar plates with KN1 medium at 24°C and an atmosphere with 5% CO2. Cells cultured under these conditions were easier to handle during the fixation and sectioning procedures than liquid suspensions. For biochemical fractionation purposes and because of the difficulties for obtaining enough material, soybean plants instead of cultured cells were used. Soybean plants were grown hydroponically in one-half Hoagland solution in a growth chamber with 350 μE m−2 s−1 and 70% relative humidity at 24°C.

Purification of Chloroplast and Chloroplast Subfractions from Soybean

All procedures were carried out in a cold chamber (4°C–8°C) under a dim green light. Isolation of intact chloroplasts from soybean on Percoll gradients was carried out essentially as described in van Wijck et al. (1995). For subchloroplast fractionation, intact chloroplasts isolated from 50 g of soybean leaves were resuspended in 15 mm NaCl, 5 mm Mg Cl2, 50 mm MES, pH 6.0. Then, an equal volume of Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer (2 mm EDTA, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) was added and the chloroplasts were kept on ice for 10 min. The chloroplasts were subjected to Suc step gradient fractionation as previously described (Li et al., 1991). The discontinuous Suc gradient was prepared with a 1.2, 1, and 0.46 m Suc solutions in TE buffer. After loading the chloroplasts, the samples were centrifuged at 39.000 rpm for 70 min in a Beckman centrifuge using a swinging bucket rotor (SW41Ti). After gradient separation, the envelope (a mixture of inner and outer membranes) was obtained as a yellow-green band in the interface of the 0.46 to 1 m Suc cushion; the stroma was retrieved from the supernatant and the thylakoid fractions were collected as a green pellet at the bottom of the tube. The envelope fraction was carefully removed, diluted with three volumes of TE buffer, and centrifuged at 20.000 rpm for 45 min in a 70.1 Ti rotor. After centrifugation, the envelope pellet was resuspended in 50 μL of TE buffer. Proteins in the stromal fraction were concentrated by acetone precipitation. Thylakoid membranes were resuspended in TE buffer and centrifuged at 7.500 rpm for 10 min. The pellet was again resuspended in TE buffer. All solutions contained a cocktail of protease inhibitors: antipain (2 μg mL−1, leupeptin 2 μg mL−1, and Pefabloc 100 μg mL−1). To verify recovery and purity of the Suc density fractions several antibodies were used as markers: Tic110 was used as envelope marker (Jackson et al., 1998), anti-RuBisCO was used as stromal marker, and anti-LHC II was used as thylakoid membrane marker.

Production of the GmFAD7 Antiserum and Western-Blotting Analysis

Antiserum was obtained from rabbits that had been immunized with the synthetic oligopeptide VASIEEEQKSVDLTNG, which corresponds to residues 69 to 84 of the deduced amino acid sequence of the GmFAD7 protein at Sigma Genosys Custom Antibody Service (Sigma-Genosys). This antiserum (200-fold dilution) was used in western analysis for the detection of GmFAD7 protein. Total protein (approximately 20 μg, depending of the fractions) was loaded per lane. Protein content was estimated using the BIO-RAD protein assay reagent. Western-blot procedures were carried out essentially as described (Collados et al., 2006) except that detection was carried out using a highly sensitive chemiluminiscent reagent for peroxidase detection (SuperSignal West Pico, Pierce). Densitometry analysis was performed with the Quantity One Software (Bio-Rad).

Sample Processing for Structural and Cytochemical Analysis and for Immunofluorescence

Soybean cells were fixed overnight at 4°C in formaldehyde 4% (w/v) in PBS, pH 7.3, and washed with PBS. Some samples were stored at 4°C for direct sectioning in a vibratome and further use for immunofluorescence. Other samples were dehydrated through an acetone series (30%, 50%, 70%, and 100% [v/v]), infiltrated, and embedded in Historesin 8100 at 4°C. Semithin sections (1 μm thickness) were obtained and used for light microscopy observations. Toluidine blue-stained semithin sections were observed under bright and phase contrast field for structural analysis in a Leitz microscope fitted with a digital camera Olympus DP10.

Cytochemical Stainings for Starch and DNA

Starch was detected by I2KI staining (O'Brien and McCully, 1981) on Historesin semithin sections and observed under bright field (Barany et al., 2005) in a Leitz microscope coupled to an Olympus DP10 digital camera. DAPI staining for DNA was applied to semithin sections (Testillano et al., 1995) and observed under UV light in a Zeiss Axiophot epifluorescence microscope fitted with a CCD camera.

Immunofluorescence and Confocal Laser Microscopy

Immunofluorescence was performed on vibratome sections as previously described (Fortes et al., 2004). Vibratome sections of 30 μm (Vibratome1000, Formely Lancer) obtained from fixed soybean cells (see above) were placed onto 3-aminopropyltrietoxysilane coated slices and treated for permeabilization purposes. First, they were dehydrated (30%, 50%, 70%, 100% [v/v]) and rehydrated (100%, 70%, 50%, 30% [v/v]) in PBS:methanol series. Second, sections were treated with 2% (w/v) cellulose (Onozuka R-10) in PBS for 45 min at room temperature. After three washes in PBS for 5 min, sections were incubated with 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 5 min and then in anti-GmFAD7 polyclonal antibodies, diluted 1:25, respectively, in 1% (w/v) BSA for 1 h at room temperature. After washing twice with PBS for 10 min each, the signal was revealed with either ALEXA 488 (green fluorescence)-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies (Molecular Probes) diluted 1:25 in 1% (w/v) BSA for 1 h in the dark at room temperature. Finally, the sections were washed twice with PBS for 10 min, stained with DAPI (Serva) for 10 min, washed with milli-Q water, and mounted with Mowiol 4 to 88 (Polysciences). Confocal optical section stacks were collected using a confocal laser scanning microscope Leica TCS-SP and laser excitation lines of 348 (UV), 488 (blue), and 633 (far-red) nm wavelength to reveal DAPI (nuclei), anti-GmFAD7 immunofluorescence signal, and chlorophyll autofluorescence (chloroplast), respectively. Controls were performed by replacing the first antibody by preimmune serum or PBS.

Control Experiment by Antibody Preblocking (Immunodepletion Experiment)

Preblocking of the anti-GmFAD7 antibody with its corresponding immunogen, the synthetic oligopeptide used to raise the serum (Collados et al., 2006), was performed by incubating the antibody with a 1 mm solution of the peptide in a proportion of 1:2 (v:v) at 4°C overnight. The preblocked antibody solution was used as primary antibody for immunofluorescence on vibratome sections, following the same protocol and conditions as previously described.

Freeze Substitution and Low-Temperature Embedding for Immunoelectron Microscopy

Soybean cells were fixed overnight at 4°C in formaldehyde 4% (w/v) in PBS, pH 7.3, and washed with PBS. Fixed cells were stored in a 0.1% paraformaldehyde solution in PBS at 4°C to prevent reversion of the fixation. Fixed soybean cells were cryoprotected by immersion in Suc:PBS solution at the following concentrations and times: 0.1 m for 1 h, 1 m for 1 h, and 2.3 m overnight, at 4°C. Then, the specimens were put in cryoultramicrotomy pins and cryofixed by rapid plunging into nitrogen liquid at −190°C. After that, the samples were dehydrated by freeze substitution in an Automatic Freeze-substitution system (AFS, Leica) essentially as described in Seguí-Simarro et al. (2005). Cryofixed samples were immersed in pure methanol containing 0.5% (w/v) uranyl acetate at −80°C for 3 d, and then the temperature was slowly (during 18 h) warmed to −30°C. After three washings in pure methanol, 30 min each at −30°C, samples were infiltrated and embedded in Lowicryl K4M at −30°C under UV. Ultrathin sections were obtained in an ultramicrotome (Ultracut Reichert) and collected on 200-mesh nickel grids having a carbon-coated Formvar-supporting film.

Immunogold Labeling

Nickel grids carrying ultrathin Lowicryl sections were sequentially floated in PBS, 5% (w/v) BSA in PBS, and undiluted anti-GmFAD7 antibody, for 1 h. After several washes in 0.1% (w/v) BSA in PBS, the grids were incubated with a secondary antibody, anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to 10 nm gold particles (Biocell) diluted 1:25 in 1% (w/v) BSA, for 1 h at room temperature, washed in PBS and water, air dried, counterstained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and observed in a JEOL 1010 EM at 80 kV. Controls were performed excluding the primary antibody.

Quantitative Analysis of Immunogold Labeling Density

Sampling was carried out over selected samples on each grid. The number of micrographs to be taken was determined using the progressive mean test, with a maximum confidence limit of α = 0.05. The labeling density was defined as the number of gold particles per area unit (μm2). Particles were hand counted over the cellular compartment under study (chloroplast) and over other cytoplasm regions. The area in μm2 was measured using a square lattice composed by squares of 15 × 15 mm each. The labeling density was expressed as the mean density ± sd.

Acknowledgments

The SB-P line was kindly provided by Professor Jack M. Widholm (Department of Agronomy, University of Illinois, Urbana). The Tic 110 antibody was kindly provided by Dr. J.E. Froehlich (Department of Energy, Plant Research Laboratory, Michigan State University).

This work was supported by the Aragón Government (grant no. PIP 140/2005) and the Ministry of Education and Culture of Spain (grant nos. BFU2005–07422–C02–01, AGL2005–05104, BFU2005–01094, and PIP2006–120). R.C. and V.A. were recipients of a predoctoral fellowship from the Aragón Government.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Miguel Alfonso (alfonso@eead.csic.es).

References

- Alfonso M, Pueyo JJ, Gaddour K, Etienne A-L, Kirilovsky D, Picorel R (1996) Induced new mutation of D1 Serine-268 in soybean photosynthetic cell cultures produced atrazine resistance, increased stability of S2QB− and S3QB− states, and increased sensitivity to light stress. Plant Physiol 112 1499–1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barany I, González-Melendi P, Mityko J, Fadón B, Risueño MC, Testillano PS (2005) Microspore-derived embryogenesis in Capsicum annuum: subcellular rearrangements through development. Biol Cell 97 709–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal M, Testillano PS, Alfonso M, Risueño MC, Picorel R, Yruela I (2007) Identification and subcellular localization of the soybean copper P1B-ATPase Gm HMA8 transporter. J Struct Biol 158 46–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collados R, Andreu V, Picorel R, Alfonso M (2006) A Light-sensitive mechanism differently regulates transcription and transcript stability of ω3 fatty-acid desaturases (FAD3, FAD7 and FAD8) in soybean photosynthetic cell suspensions. FEBS Lett 580 4934–4940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douce R, Joyard J, Block MA, Dorne AJ (1990) Glycolipid analyses and synthesis in plastids. In JL Harwood, JR Bowyer, eds, Methods in Plant Biochemistry: Lipids, Membranes and Aspects on Photobiology, Vol 4. Academic Press, London, pp 71–103

- Dyer JM, Chapital DC, Cary JW, Pepperman AB (2001) Chilling-sensitive, post-transcriptional regulation of a plant fatty acid desaturase expression in yeast. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 282 1019–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer JM, Mullen RT (2001) Immunocytological localization of two plant fatty acid desaturases in the endoplasmic reticulum. FEBS Lett 494 44–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferro M, Salvi D, Brugière S, Miras S, Kowalski S, Louwagie M, Garin J, Joyard J, Rolland N (2003) Proteomics of chloroplast envelope membranes from Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Cell Proteomics 2 325–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feussner I, Wasternack C (2002) The lipoxygenase pathway. Annu Rev Plant Biol 53 275–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortes AM, Coronado MJ, Testillano PS, Risueño MC, Pais MS (2004) Expression of lipoxigenase during organogenic nodule formation from hoop internodes (Humulus lupulus var. Nugget). J Histochem Cytochem 52 227–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich JE, Wikerson CG, Ray WK, McAndrew RS, Osteryoung KW (2003) Proteomic study of the Arabidopsis thaliana chloroplastic envelope membrane utilizing alternatives to traditional two-dimensional eletrophoresis. J Proteome Res 2 413–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller MA, Weichert H, Fischer AM, Feussner I, Grimes MD (2001) Activity of soybean lipoxygenase isoforms against esterified fatty acids indicates functional specificity. Arch Biochem Biophys 388 146–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iba K (2002) Acclimative response to temperature stress in higher plants: approaches of gene engineering for temperature tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Biol 53 225–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DT, Froehlich JE, Keegstra K (1998) The hydrophilic domain of Tic110, an inner envelope membrane component of the chloroplastic protein translocation apparatus faces the stromal compartment. J Biol Chem 278 16583–16588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäger-Vottero P, Dorne AJ, Jordanov J, Douce R, Joyard J (1997) Redox chains in the chloroplast envelope membranes: spectroscopic evidence for the presence of electron carriers, including iron-sulfur centers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94 1597–1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster AJ, Klumperman J (2003) Electron microscopy in cell biology integrating structure and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4 SS6–SS10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HM, Moore H, Keegstra K (1991) Targeting of proteins to the outer envelope membrane uses a different pathway than transport into chloroplast. Plant Cell 3 709–717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liavonchanka A, Feussner I (2006) Lipoxygenases: occurrence, functions and catalysis. J Plant Physiol 163 348–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda O, Sakamoto H, Hashimoto T, Iba K (2005) A temperature-sensitive mechanism that regulates post-translational stability of a plastidial ω-3 fatty acid desaturase (FAD8) in Arabidopsis leaf tissues. J Biol Chem 280 3597–3604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustardy L, Los DA, Gombos Z, Murata N (1996) Immunocytochemichal localization of acyl-lipid desaturases in cyanobacterial cells: evidence that both thylakoid membranes and cytoplasmic membranes are sites of lipid desaturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93 10524–10527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien TP, McCully ME (1981) The Study of Plant Structure Principles and Selected Methods. Termarcarphi Pty. Ltd., Melbourne, Australia, pp 357

- Ohlrogge JB, Browse J (1995) Lipid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 7 957–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltier JB, Ytterberg AJ, Sun Q, van Wijck KJ (2004) New functions of the thylakoid membrane proteome of Arabidopsis thaliana revealed by a simple, fast, and versatile fractionation strategy. J Biol Chem 279 49367–49383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risueño MC, Testillano PS, González-Melendi P (1998) The use of cryomethods for plant biology studies. In HA Calderón-Benavides, MJ Yacamán, eds, Electron Microscopy 98. Inst. Physics, Philadelphia, pp 3–4

- Rogers SMD, Ogren WL, Widholm JM (1987) Photosynthetic characteristics of a photoautotrophic cell suspension culture of soybean. Plant Physiol 84 1451–1456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller F, Schaller A, Stinzi A (2005) Biosynthesis and metabolism of jasmonates. J Plant Growth Regul 23 179–199 [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H, Heinz E (1990. a) Involvement of ferredoxin in desaturation of lipid-bound oleate in chloroplasts. Plant Physiol 94 214–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H, Heinz E (1990. b) Desaturation of oleoyl groups in envelope membranes from spinach chloroplast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87 9477–9480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguí-Simarro JM, Testillano PS, Jouannic S, Henry Y, Risueño MC (2005) MAP kinases are developmentally regulated during stress-induced microspore embryogenesis in Brassica napus. Histochem Cell Biol 123 541–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguí-Simarro JM, Testillano PS, Risueño MC (2003) Hsp70 and Hsp90 change their expression and subcellular localization after microspore embryogenesis induction in Brassica napus cv. Topas. J Struct Biol 142 379–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slabas AR, Smith CG (1988) Immunogold localization of acyl carrier protein in plants and Escherichia coli evidence of membrane association in plants. Planta 175 145–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelmach BA, Muller A, Henning P, Gebhardt S, Schubert-Zsilavecz M, Weiler EW (2001) A novel class of oxylipins, sn-1-O-(12-oxophytodienoil)-sn2-O-(hexadecatrienoyl)-monogalactosyl diglyceride, from Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem 276 12832–12838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testillano PS, González Melendi P, Ahmadian P, Fadon B, Risueño MC (1995) The immunolocalization of nuclear antigens during the pollen developmental program and the induction of pollen embryogenesis. Exp Cell Res 221 41–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wijck KJ, Bingsmark S, Aro E-M, Andersson B (1995) In vitro synthesis and assembly of photosystem II core proteins. J Biol Chem 270 25685–25695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vick BA, Zimmerman DC (1979) Distribution of a fatty acid cyclase enzyme system in plants. Plant Physiol 64 203–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis JG, Browse J (2002) Mutants of Arabidopsis reveal many roles for membrane lipids. Prog Lipid Res 41 254–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav NS, Wierzbicki A, Aegerter M, Caster CS, Pérez-Grau L, Kinney AJ, Hitz WD, Russell Booth J, Schweiger B, Stecca KL, et al (1993) Cloning of higher plant ω3 fatty-acid desaturases. Plant Physiol 103 467–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]