Summary

In an ideal world, all of us – patients, parents, family members, nurses, physicians, social workers, therapists, pastoral care workers, and others – would always work together in a collaborative manner to provide the best care possible to the patient: this article is committed to this ideal. The chapter will base the frameworks and suggestions in part upon studies of communication between patients, families, and clinicians, as well as more general works on communication, collaboration, decision-making, mediation, and ethics.

This article unfolds in four parts. In Part I, we will explore what we mean by collaborative communication. In Part II, we will examine key concepts that influence how we frame the situations that children with life-threatening conditions confront and how these frameworks shape the care we provide. In Part III, we will consider a few general topics that are quite important to the task of collaborative communication, specifically how we use little “habits of thought”– called heuristics – when we set about to solve complicated problems; how emotion affects the exchange of information between people; and how we can avoid certain pitfalls when engaging in difficult conversations. In Part IV, we will proceed through three common tasks of collaborative communication offering practical advice for patient care.

Keywords: communication, decisionmaking, end of life

INTRODUCTION

Let us communicate with each other clearly, compassionately, and collaboratively, as we strive to improve the quality of life for children including, when necessary, that part of life that is dying.

I offer us this goal at the outset, as it will guide our journey over the course of the following pages, and perhaps beyond. Throughout this article, I will address you, the reader, directly. I do so with respect, aiming to be as straightforward and clear as possible about the cognitive and emotional challenges of communicating in a collaborative manner. While I anticipate that most of you are clinicians, I will also attempt to make our discussion useful for those of you who are parents or even patients. In an ideal world, all of us – patients, parents, family members, nurses, physicians, social workers, therapists, pastoral care workers, and others – would always work together in a collaborative manner to provide the best care possible to the patient: this article is committed to this ideal, and when I say “we” or “our” I respectfully mean to imply all of us. As much as possible, I base the frameworks and suggestions that I present in part upon studies of communication between patients, families, and clinicians(1–10), as well as more general works on communication, collaboration, decision-making, mediation, and ethics(11–19), all of which have been filtered through my own experiences as a physician, family member, and patient(20, 21).

This article unfolds in four parts. In Part I, we will explore what we mean by collaborative communication. In Part II, we will examine key concepts that influence how we frame the situations that children with life-threatening conditions confront and how these frameworks shape the care we provide. In Part III, we will consider a few general topics that are quite important to the task of collaborative communication, specifically how we use little “habits of thought” – called heuristics – when we set about to solve complicated problems; how emotion affects the exchange of information between people; and how we can avoid certain pitfalls when engaging in difficult conversations. In Part IV, we will proceed through three common tasks of collaborative communication offering practical advice for patient care.

Part I: Collaborative Communication

What does the phrase “collaborative communication” aim to convey? The wide-ranging concept of communication indicates “the imparting or exchanging of information or news”(22). Modifying this general concept with the concept collaboration speaks to a particular type of communication, one that aims to be “produced or conducted by two or more parties working together.”

Collaborative communication encapsulates both the exchange of information and the nature of the collaborative relationship between the persons who are communicating. It recognizes the essential reciprocity and dynamic synergy of this pair of concepts, whereby better communication enhances collaboration, and more skillful collaboration can improve communication. Stated somewhat differently: collaborative communication emphasizes the relationships between people, viewing interpersonal communication and relationships as inexorably entwined (23).

Collaborative communication is distinguished by participants’ desire to accomplish at least five important tasks:

Establishing a common goal or set of goals that guide our collaborative efforts

Exhibiting mutual respect and compassion for each other

Developing a sufficiently complete understanding of our differing perspectives

Assuring maximum clarity and correctness of what we communicate to each other

Managing intra-personal and interpersonal processes that affect how we send, receive, and process information

PART II: A GENERAL OVERVIEW OF PEDIATRIC PALLIATIVE CARE

The challenges – and opportunities – of collaborative communication are best understood when situated in the broader context of palliative care, including the core tasks of palliative care, the ways in which the experiences of “dying” unfold for children with life-threatening conditions and how our medical system distinguishes palliative care from other modes of care.

PALLIATIVE CARE

Over the past decade a consensus has emerged(24–27) that, in general, palliative care for adults involves eight interrelated core activities:

Provide effective pain and symptom management to help minimize suffering.

Attend to and minimize sources of emotional, social, and spiritual suffering.

Minimize the amount of time that patients spend with what they would deem to be an unacceptably poor quality of life prior to dying.

Communicate in a manner that prepares and empowers patients and families.

Enhance the patient and family’s ability to make what they feel are good decisions.

Assure that medical treatment is in accord with patient and family wishes.

Strive to strengthen important relationships between the patient and family and friends.

Provide loved ones with bereavement support and grief care.

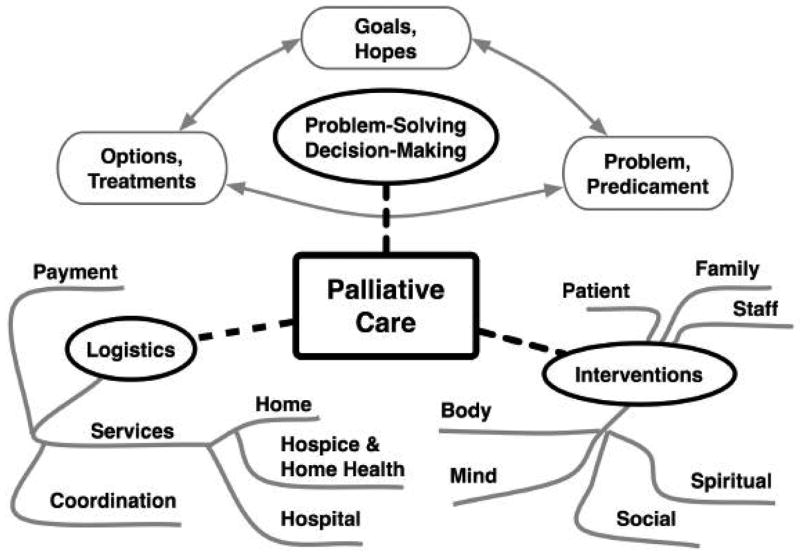

In pediatric palliative care(28, 29), we can organize this plethora of tasks into three domains illustrated by Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Palliative Care and Its Three Core Domains of Tasks

Problem-solving and decision-making activities involve identifying and describing the problems or predicaments that confront the patient and those caring for the patient. They include clarifying the goals and hopes that motivate and guide care; and in light of these goals of care, evaluating the pros and cons of a variety of options, ranging from specific treatments to locations of care.

Interventions typically seek to improve the quality of life and minimize suffering for patients, family members, and clinical staff. They address the physical, mental, emotional, social, cultural, spiritual, and existential needs of the individual.

Logistical efforts aim to provide high-quality services in various settings including the hospital and home; to coordinate these services; and to arrange appropriate payment.

PATHWAYS OF DYING

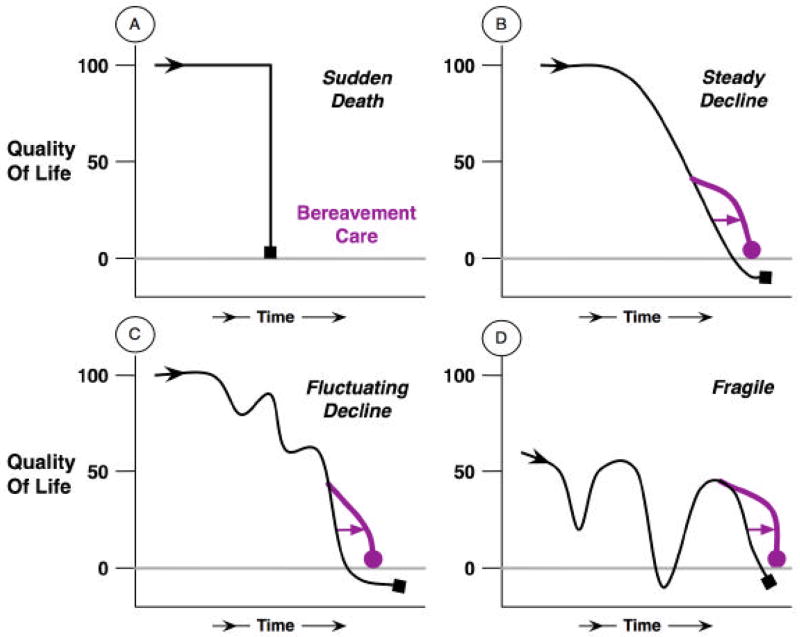

Broadly speaking, the pathways of dying followed by infants, children, and adolescents who die in the United States display four different patterns illustrated by Figure 2. For many children, death occurs suddenly as in pattern A. These are the deaths due to traumatic injury (either unintentional such as motor vehicle collisions or intentional such as homicide), precipitous premature birth, or occult conditions such as cerebral aneurisms and cardiac arrhythmias. In these cases, pediatric palliative care focuses mostly on bereavement care for the family after the child’s death and support of the emergency responders and clinicians who cared for the patient.

Figure 2.

Patterns of Pathways of Dying

The second pattern, pattern B, includes children who had been in good health until a disease or condition, such as a malignancy or a degenerative disorder, began to cause a steady decline in quality of life, predictably and inexorably. A major focus of palliative care for these children involves efforts to maximize a child’s quality of life for as long as possible (as depicted in the figure by the arrow and the rightward shift of the alternative palliative care pathway, with higher quality of life levels but perhaps for a shorter length of time).

Pattern B also illustrates a peculiar aspect of the pathways to death, an aspect that may seem macabre but is important. In each of the patterns depicted in Figure 2, the scale for quality of life ranges from 100 (maximum quality of life) to 0 (the quality of life associated with being dead). The scale then extends below 0 (a quality of life worse than being dead) as in pattern B, C and D. In common parlance, people will refer to certain circumstances as being “a fate worse than death”. Researchers focused on developing concepts about quality of life have documented that conditions involving great suffering or profound impairment are viewed by many as being worse than death(30). A core task of palliative care is to prevent a child’s quality of life from descending into these states worse than death. In pattern B, the alteration in the pathway brought about by palliative care therefore depicts not only maximization of quality of life, but also the minimization of time spent with the quality of life below 0.

Pattern C reflects, essentially, a variation on pattern B, whereby the pace of decline after the onset of the condition varies significantly, with episodes of worsening health interspersed among periods of relative recovery. Pattern C is the pathway for many children who die from a wide variety of medical conditions, ranging from malignancies that enter remission and then relapse, to cystic fibrosis with periodic exacerbations, to metabolic disorders that cause lasting injury with every episode of decompensation. Here again, palliative care aims to maximize quality of life by maximizing the “good” aspects of the child’s life, for example by facilitating goals such as residing at home and minimizing suffering through assiduous management of symptoms, and by preventing time spent with a quality of life worse than death.

A fourth group of children follow a different pathway, depicted as pattern D. These children have impairments of physiologic function that render them fragile and more vulnerable than other children to recurrent health crises. These crises are often of sudden onset and precipitated by otherwise innocuous events such as a common cold or a bout of emesis. This state of fragile health or extreme vulnerability to life-threatening illness is typically long-standing, with the quality of life less than ideal for months or years. Consequently - and very importantly - the pattern of fragile health comes to define the way of life for these children and their families, as they often live waiting for the next crises and setback. As a clinician or family member, determining when the child is dying can be difficult. Deciding when to redefine the goals of care from life-extending to comfort-seeking can be divisive within families, between families and clinicians, and among clinicians.

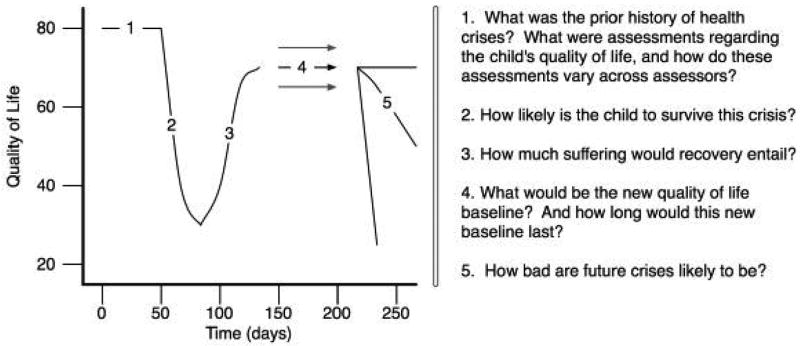

In large part, these difficulties of deciding when to redefine the goals of care arise due to difficulties of predicting what the child’s health state will be in the future. As illustrated in Figure 3, the difficulties of prognostication can be summarized by five major questions.

Figure 3.

Aspects of Prognostic Uncertainty for “Fragile” Children

First, what was the child’s health status and quality of life prior to this crisis? People are likely to have different answers to this question, based largely on their relationship to the patient, their degree of knowledge about the child over time, and their personal values and beliefs. These differences of perspective are worth exploring. For instance, if the clinicians have come to know the child chiefly when the child is critically ill and hospitalized, their perspective may be broadened if the family shares photographs of the child interacting with other family members taken during a period of relative wellness.

Second, how likely is the child to survive the current crisis? Clinicians should be aware that parents may have witnessed the child survive severe crises in the past. They may then condition their assessment of the probability of survival on this past record of “beating the odds”.

Third, if the child were to survive, what would the child have to endure on the path of recovery? For instance, in the best-case scenario, would a prolonged period of intubation and mechanical ventilation nevertheless be necessary?

Fourth, after recover is complete and a new baseline of health and quality of life is established, what will this new baseline be? Not infrequently, the injury incurred during a health crisis can persist, diminishing the new baseline significantly from previous levels. Furthermore, the duration of time living at this new baseline is also uncertain. How long before the next crisis?

Fifth, how severe are future crises likely to be? Families will worry both in terms of the likelihood of dying and the degree of suffering that may be part of their child’s future.

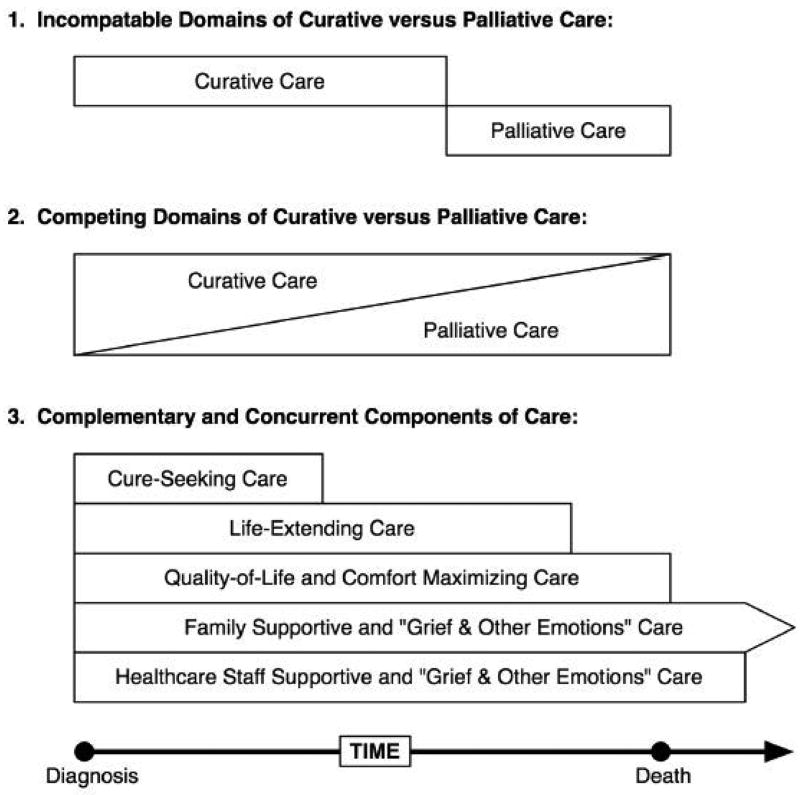

CONCEPTUAL MODELS OF CARE

Uncertainty is a fundamental aspect in all patterns of dying. In order to understand how to manage this irreducible element of uncertainty, we must understand how various conceptual models of care relate to each other. Figure 4 illustrates 3 common models.

Figure 4.

Evolution of the Relationships Between Conceptual Models of Care

Until the past decade or so, due largely to the history of how hospice and palliative care arose in opposition to standard medical care, the reigning model was that typical medical care (labeled as “curative care” even though most diseases are managed rather than cured) and palliative care were mutually exclusive, incompatible domains of care. One had to pick one or the other, with a consequently abrupt transition from curative to palliative care – if the transition was ever made.

Beginning in the 1990s, a new conceptual model was presented, wherein the two modes of care could be provided simultaneously, with a gradual increase in palliative care over time as a proportion of all care and an offsetting diminishment of curative care(31).

Whether intended or not, this model still conceives curative and palliative care as in competition, with any effort devoted to one form of care coming at the expense of the other. Both of these first two models may hinder problem-solving and decision making by their dichotomization of care and foisting upon decision makers the seemingly unavoidable tradeoffs between the two modes (such as, “are we willing to forgo all forms of life-prolonging treatments in order to enroll in hospice?”).

An alternative model categorizes all the interventions and acts of care based on their aims or objects: what does this act of care seek to accomplish? A single act of care can be motivated by one or several goals. Cure-seeking care aims to eradicate the underlying health problem. For example, penicillin can cure a bacterial pneumonia, and chemotherapy can cure certain malignancies. This objective is often sufficient for most pediatric patients.

For many life-threatening conditions, however, cure is never a feasible goal. Instead, life-extending care seeks to enable the child to live with the condition longer such as insulin therapy did for people with Type 1 diabetes. Importantly, many of these interventions also enhance quality of life and are valued and used eagerly because of this effect.

Other interventions aim more specifically to improve quality of life and comfort maximizing care, such as the use of medications to reduce muscular spasticity and its complications. Again, while the primary objective is to improve function, maximize quality of life, and minimize suffering, these interventions may also extend life.

For the practice of pediatrics, care important to the patient is not limited to just the patient but extends to the parents or other family members upon whom the patient depends for quality decision making and physical care. Family supportive care is an important mode of care that starts at diagnosis and extends beyond death, attending to the the grief and other emotions of the parents and family members. While much of this care must be recognized and managed prior to the child’s death, it extends past death in the form of bereavement care.

In parallel, a similar mode of care exists to support clinicians who in their humanity also grapple with a host of emotions in the care of children with life-limiting conditions. Healthcare staff supportive care, while not often delivered in a well organized manner, aims to address the grief and other emotions associated with caring for these children.

This conceptualization of care, by avoiding the dichotomization of the modes of care and by organizing the acts of care based on goals, allows some of the problems arising from uncertainty to be managed in a more flexible manner.

PART III: THE PSYCHOLOGY OF COLLABORATIVE COMMUNICATION

Beyond working to understand how each of us view the concepts of pediatric palliative care, we can advance our ability to communicate collaboratively if we also attend to our own habits of thought, emotions, and ways in which we handle interpersonal conflict. We will inspect this by exploring how our innate judgments and processes affect how we define situations and make decisions.

DEPICTIONS AND DETECTION

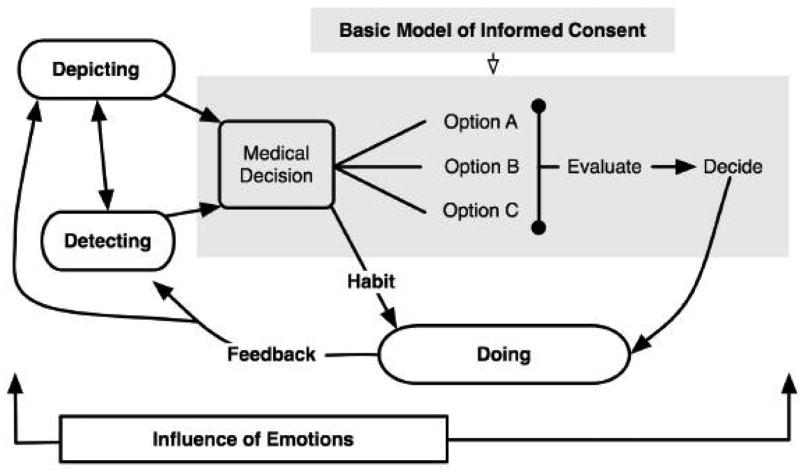

Over the past thirty years, the medical landscape of communication and decision-making has been shaped by the ideal of informed consent(32). In the basic model of informed consent (as depicted in Figure 5), a medical problem, such as a symptom or a disease, is evaluated by the physician. The physician then describes to the patient the range of reasonable treatment options and explains the pros and cons of each option so that the patient can make an informed decision.

Figure 5.

An Expanded Model of Decision Making

Often in pediatric palliative care, however, patients, parents, and clinicians have conceptualize the medical situation and predicaments quite differently (as in the difference between the viewpoints that “we can beat this” versus “there is no longer a realistic chance of cure”), leading us to differ regarding the way we think about various medical decisions and how we evaluate treatment options. Two psychological processes, which we will call depiction and detection, play large roles in creating these difference, as they guide us as we define what constitutes the “medical problem” and thus determine how options are viewed and evaluated(33).

First, each of us creates, within our own minds, a depiction or representation of reality. As we interpret the meaning of symptoms, test results, behaviors, or events, we develop notions of what is going on and what it all means. These depictions reflect our individual temperaments, personal experiences, social circumstances, and cultural heritage and may be quite different than another person’s interpretation. For example, a physician may consider the relapse of a malignant tumor in a patient as a challenge of medicine to rid the body of cancer, while a person of strong religious convictions may interpret the same event as a challenge of spiritual faith.

Second, based in part on how we have depicted a situation within ourselves, we focus on certain aspects of that situation while ignoring others. In the same way, the detection of problems warranting our attention will differ based on the individuals interpretation. Again, the same physician may detect as a problem the patient or family’s steadfast belief in an extremely unlikely cure, while the patient and family may detect as their chief problem the challenging of maintaining their faith in an environment of disbelief.

Collaborative communication is fostered by acknowledging that “the problem” can differ from various points of view. Asking each other to share their sense of what is going on and what it means enables us to compare and contrast our depictions, and perhaps learn why we have focused on different problems.

HABITS OF THOUGHT AND INFLUENCE OF EMOTIONS

Ideally, we make decisions on the basis of methodical consideration of all the advantages and disadvantages of the treatment options. However, collaborative communication must also consider with our tendency to make decisions on the basis of quick assessments built upon habits or shortcuts of thought (what psychologists call heuristics(34, 35)). While these habits may work well under most circumstances, they may also lead to systemic cognitive biases. Three of these heuristics are extremely pertinent to pediatric palliative care.

‘Availability’ and Probability

Most of the time, we gauge how likely something is to happen based on how easily we can imagine it happening rather than as a quantified measure of probability. If we have witnessed a chain of events unfold before our eyes in the past and can readily imagine the same sequence happening again we tend to believe that this is more likely to occur. Conversely, events that we have a hard time imagining we judge to be unlikely to occur. The memory of the experience is easily available to our imaginative mind.

This phenomenon may explain, in part, why parents who have watched their child recover “from death’s door”, defying prognoses offered by physicians, subjectively estimate the likelihood of recovery to be higher than what an objective assessment would estimate. It may also explain why physicians’ prognoses are influenced by the outcomes of their most recent or most memorable patients (as exemplified when clinicians recall that they “once had a similar patient who recovered” and thus over-estimate the likelihood of recover for the current patient).

To work with this innate habit of thought, collaborative communication sometimes involves helping each other envision possible events – desirable and undesirable – so that these events become mentally available allowing a better assessment of the probability that these events may occur. The key issue is to recognize that a sequence of events that people can not imagine will be judged as unlikely to occur, and a true assessment of the options must consider this bias.

‘Anchoring’ and Evaluation

When it comes to evaluative judgments (that is, how we answer questions like “which is better, A or B?”), first impressions matter. For instance, if when presenting the pros and cons of various treatment options we decide to first talk about the risks, our subsequent thinking will be more dominated by concerns about risk than if we had started out by talking about possible treatment benefits. This phenomenon of how our thinking gets anchored to a particular concern, perspective, or fact is pervasive, subtle, and difficult to overcome.

One method that can shift the anchor is to draw attention to it and then try to take an alternative perspective. For example, if thoughts about risk have come to dominate a conversation, one might say: “I’m noticing that we are talking a lot about the bad things that could happen if we choose one of these treatments, and while this is important, why don’t we try to focus just on the various good things that may happen and see how these treatments compare.”

The second point of advise about anchoring is to make sure that the same anchoring bias is bestowed upon all treatment options. In other words, do not tolerate yourself or someone else presenting treatment A first in terms of benefits and then risks, and then presenting treatment B first in terms of risks and then benefits. Instead, be even-handed and present both in the same manner, devoting equal time and attention to each.

The ‘Affective Heuristic’ and Aversion

The prospect of a child suffering or dying often evokes deeply disturbing images that generate strongly unpleasant feelings. Consequently, many people develop an aversion to contemplating the possibility of suffering, death or even certain treatment options that seek to minimize suffering but not prevent death. People often use these aversions associated with the disturbing images as a guide or shortcut to figure out the best course of action. Usually they pick the course of action that minimizes the negative images and feelings.

One example of this mode of thinking was expressed by a father who had dialed 9-1-1 when his child, who was at home with hospice care for an intractable tumor when he became somnolent. The father said, “I couldn’t image just sitting there doing nothing and watching my child die.” After empathetically wishing that neither he nor his child had to go through any of this, the conversation gently turned to imaging what could be done while sitting at the child’s bedside, perhaps holding a hand and talking with his child, or climbing into bed and rocking his child. In effect, this approach helped to create and explore new images with perhaps different feelings, still sad, but hopefully not as scary. The challenge presented when working with the affective heuristic point more broadly to the influence that emotion has on individuals and groups when they try to work together to solve problems and make decisions.

EMOTIONAL INTELLEGENCE

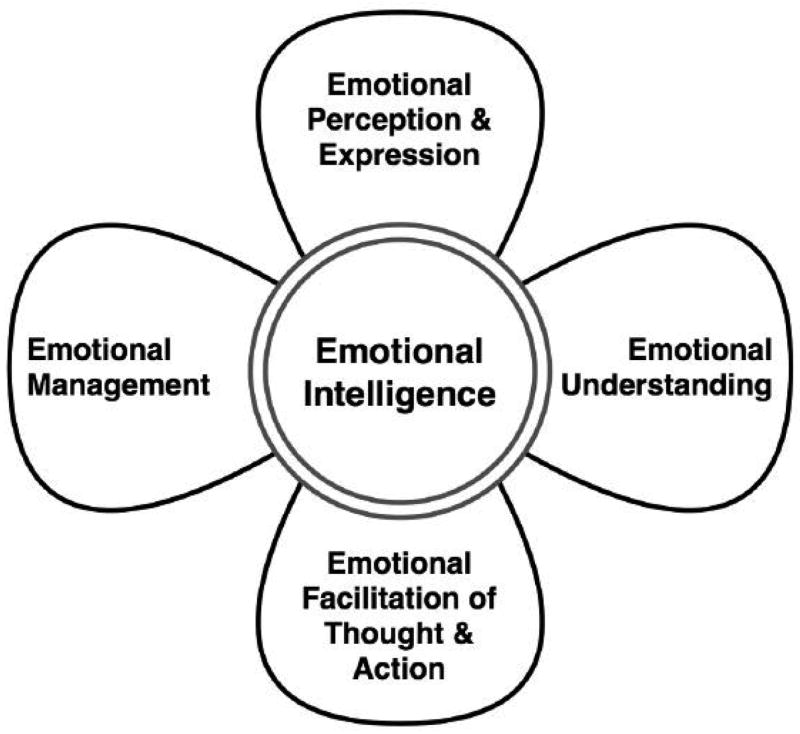

To handle emotions well, people engaged in collaborative communication use emotional intelligence, which is “ the ability to process emotion-laden information competently, to use it to guide cognitive activities like problem solving, and to focus energy on required behaviors.”(36) This vital ability can be broken down into four specific aptitudes as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Emotional Intelligence and Its 4 Core Aptitudes

Emotional Perception and Expression: your ability to perceive emotions in others and to effectively express your emotions to others, creating a two-way flow of emotional communication.

Emotional Understanding: when perceiving or feeling an emotion within yourself, to be able to interpret it correctly (for instance, when feeling sad, recognizing the emotion as sadness and not misinterpreting it as anger or irritation).

Emotional Facilitation of Thought and Action: your ability to use emotion to improve your ability to think more clearly or perform behaviors with greater skill (in other words, the ability to “psych yourself up” or “calm down” to perform a specific task).

Emotional Management: the ability to manage or influence your own emotions and the emotions of others when working together.

This model, I have found, can help when coaching either myself or others regarding how to handle emotionally challenging situations, as I ask myself “which of these aptitudes do I need to focus on to best help myself or another person through a difficult situation?” While many educational or training programs (which have been introduced in a wide variety of settings from elementary schools to corporate businesses) claim to improve emotional intelligence, none can be specifically recommended due to lack of rigorous evaluations.

MANAGING CONFLICT

Sometimes in the course of providing clinical care – despite our best efforts to clarify goals, understand each other’s perspectives, and manage our emotions – conflicts arise. These conflicts may be between parents and physicians, or between family members, or among various clinicians on the health care team, or almost any other combination of individuals who care about and for the patient. Often in these situations, what is most palpable is the feeling of discord, disagreement, or disgruntlement. Typically, the actual nidus of the conflict remains unspoken, and this root source may be unclear or unknown to one or even both parties. Regrettably, we often try to communicate while avoiding the source of conflict, under the assumption that the conflict is either unsolvable or could be solved only if “they” would be reasonable. In order to proceed in collaborative communication, the conflict must be addressed and managed.

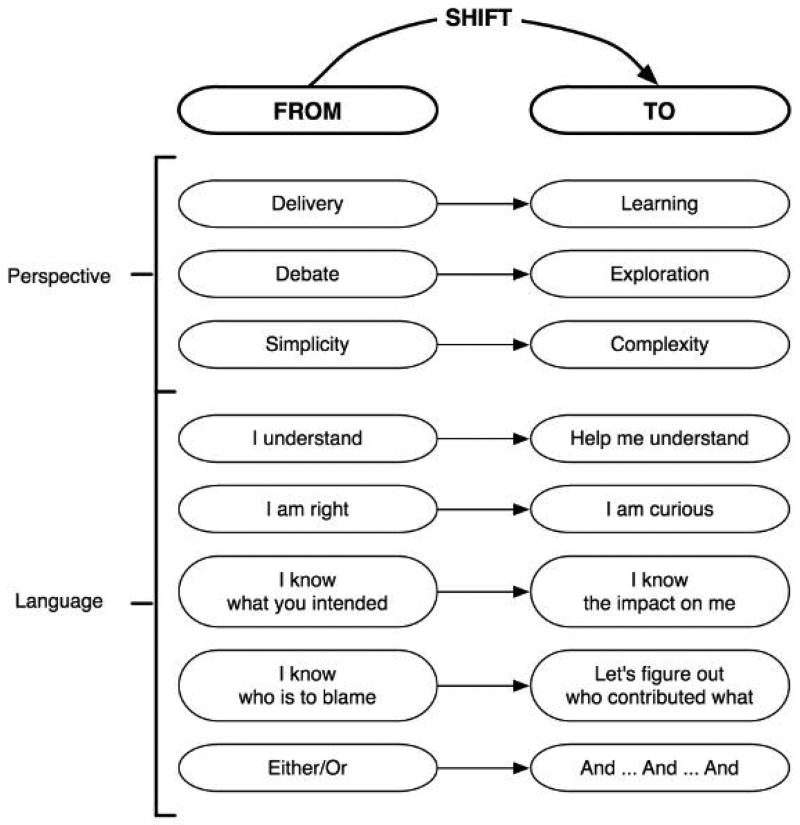

A useful strategy to address conflict and have more productive “difficult conversations” is to fundamentally shift our thinking about interpersonal conflict and how we deal with it (11, 20). Figure 7 illustrates some details of this shift.

Figure 7.

Shifting Difficult Conversations From Conflict Towards Learning

Difficult conversations usually are viewed as involving the delivery or receipt of accusations, debating who is right and who is wrong. Participants often settle for simple notions of what caused the conflict and what needs to be done to resolve it. We must recognize, however, that we usually do not know the intentions that motivated other people’s actions; instead, we infer these intentions (often inaccurately) from the impact that the actions had on us: we think (without really thinking about it) that “I feel hurt; therefore you meant to hurt me”.

Productive conversations about difficult issues focus on learning more about the perspectives of both parties, exploring what may be a complex web of actions that contributed to the conflict. This shift in approach is mirrored by a shift in perspective from the certainty of one’s understanding and rightness to a more curious posture, seeking not to blame but striving to understand everyone’s contributions. People engaging in collaborative communication should avoid the assumption that other people wanted the have a certain effect on them and rather talk openly about the impact that specific behaviors or actions did have.

Participants in collaborative communication should also attend to what they think the conflict says about themselves and their sense of personal identity, that is, whether they feel insecure or threatened, devalued or disappointed, incompetent or insensitive. Since we all make mistakes, sometimes acting in a manner that contributes to conflict with a mixture of motives that guides our behavior, some of these self-reflections may have a kernel of truth.

A way to acknowledge these reflections, while also endorsing the encompassing truth that our intentions are good, is to use the simple word AND repeatedly and avoid the word BUT. For example, “I hear you that when I had to cancel our last meeting on short notice that you felt upset AND that you felt that I did not value your time AND I want to apologize AND I want to assure you that I did not want to upset you AND that I do value your time AND I want to thank you for coming back in today to talk about your child AND I hope we can make some good progress today in our plans.” Using AND while avoiding BUT shifts the tone of the language from argument to mutual exploration.

PART IV: THREE COMMON TASKS IN PEDIATRIC PALLIATIVE CARE

While the work of pediatric palliative care involves a myriad of tasks that require our best efforts at collaborative communication, for the remainder of this article we will focus on three common tasks.

1. COMMUNICATING BAD NEWS

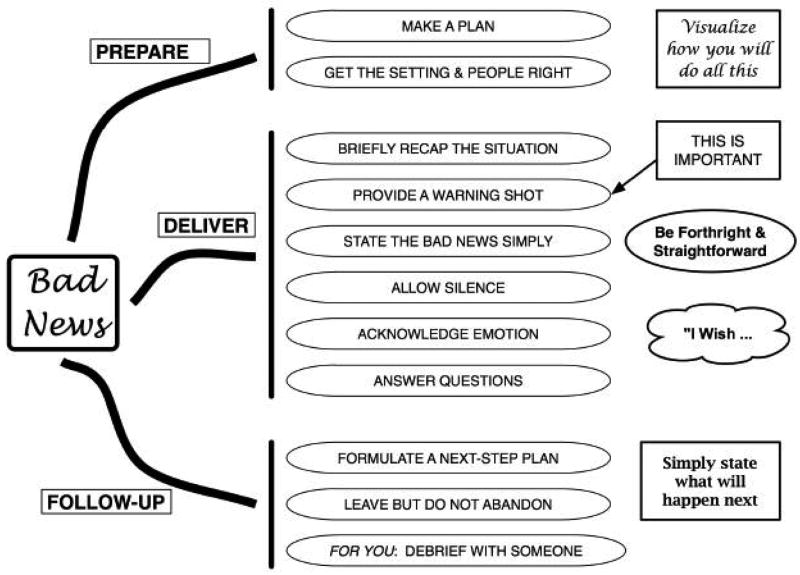

Clinicians who have the duty to communicate bad news to patients or family members might improve their performance of this task by following some guidelines that have been developed based on interviews with patients and family members as well as expert experience and opinion(37–41). Figure 8 illustrated these guidelines. First, the overall task of communicating bad news can be usefully subdivided into three phases: preparation, delivery, and follow-up.

Figure 8.

The Delivery of Bad News

The first phase, preparation, is essential. Taking the time to formulate a plan of how to deliver the news can dramatically improve how well the information is conveyed. Key parts of preparation include:

Rehearse what to say and how to say it. This should include visualizing how to get the right people to the proper setting and then how the delivery of the news.

Consider where to deliver the news. Should the setting be a private conference room or at the bedside? Who should be present at the meeting? Should we talk with just the patient? Should we include a parent alone or wait for both parents to be available? Will it be helpful to include the nurse or social worker?

Investigate if the patient or family is of a particular culture that handles the communication of bad news in a particular way. You should then make plans to work with their cultural values and expectations.

Visualize how to get the right people to the proper setting and then how the delivery of the news will unfold may take a small amount of time, but will yield many benefits in clinical practice.

The second phase involves the actual delivery of the news. Starting by briefly recapping the clinical situation provides some necessary context for receiving and interpreting the news. Even the most complex episode of hospital care can, for the purpose of providing a conversational context for some upcoming bad news, be condensed and conveyed in a minute or two.

At this point in the discussion, provide the patient or family with a “warning shot,” meaning a phrase that alerts them to the fact the news to follow is not good; for instance, one might say that “The results of the test are now back, and I am afraid that the news is not good.“ A pause should follow. According to patients and family members, this pause before the actual statement of the news provides a moment to brace themselves for the news, so that they are not caught off guard.

When communicating the news, state the facts simply and in plain language, such as “the cancer has spread.” Then be quiet. The core aspect of the news is often conveyed in a sentence, perhaps two or three. Avoid the temptation to continue to talk after this core news has been spoken. Instead, allow silence. Persons receiving bad news often are flooded with emotion and become disengaged from the conversation for a period of time. Although allowing silence may at first feel awkward, most people appreciate the silence as a sign of respect and empathy. Continuing to talk can be interpreted as unfeeling. The duration of silence can vary from one conversation to the next, and no reliable rules guide when to resume speaking other than remaining fully engaged and responsive to the reactions of the people in the room.

One way to resume speaking is to acknowledge your own emotion with an “I wish” statement, such as “I wish this news was different” or “I wish that the cancer had not spread.” Be careful to avoid making statements that attempt to relate yourself to another person’s emotions, such as “I can’t image how you feel”. Instead, acknowledge their emotions with simple observational statements, such as “I can see that you are very upset” or “I hear how angry you are.”

If the patient or family members ask questions, provide forthright and straightforward answers. Realize that much of the information may need to be repeated later as strong emotions can impair the subsequent recall of information. If no questions are asked, even after you have solicited them (“I don’t know if you want to ask any questions at this point; if you are, I can answer them; if not, you can ask them later”), then move on to the next phase.

Phase three involves making plans for the next steps in care and communication. While the family may need time to digest the bad news, they will need clear Information on what the next step of care Includes. This often includes reframing the situation, reanchoring the framework of understanding, or readdressing the goals of care for the child (methods that I will discuss shortly).

Before ending the meeting the patient and family will need to know when they can next expect more information or a future opportunity to ask questions. This may be a meeting with you or with someone else such as a new specialist or another trusted physician. Tell them what to expect at that meeting, for example “I am going to leave now and will be back in an hour (or whenever; just be specific). We’ll review what we just talked about and I’ll answer questions. We’ll then start to map out how we want to move forward.” By spelling out how you will be returning you will be much less likely to give the impression that you are abandoning them.

The final step regards personal self-care, so I will speak about it more personally. I find telling another person bad news to be a remarkably stressful task. Having a plan has made it less stressful for me over the years, but it is still challenging, intellectually and emotionally. Sometimes I can deliver bad news and keep moving to the next clinical task; other times I am blown away, either because I did not do as good a job as I had intended, or because the reaction of the patient or family to the news really affected me. Following these kinds of encounters, I have found it helpful to acknowledge my own emotions – sadness, anger, fear, guilt – to myself and to a trusted colleague, often within minutes of the conversation. If I wait, I rarely do this self-care debriefing, and it becomes less effective. Again, a minute or two is all this usually takes, but it is personally priceless time.

2. REFRAMING AND REANCHORING SITUATIONS

One of the most common events in collaborative communication involves framing a situation(13, 42). We do this every time we start a conversation, as we quickly answer a series of questions: What are we talking about? What problem or opportunity concerns us? What are we trying to achieve? What is the pertinent context of our discussion? What are the key facts that we should all know?

We have already seen how these questions can be addressed when the conversation is about bad news. While many of those tactics can be used for a wide range of conversational subjects, several inter-related issues that more decisively frame clinical situations warrant special attention here.

Goals of Care and the Range of Hopes

First, excellent pediatric palliative care requires that the goals of care be conceived through a process that is compassionate and holistically comprehensive. Quite often, however, the goals of care are obscure because they are never discussed explicitly, clearly, openly.

Typically, when a child first presents with signs of a medical problem, the primary goal is to rid them of the problem, often through a cure. This common goal is usually left unstated as it is assumed by the patient, family members and clinicians alike. However, when more prognostic information about the medical problem becomes available, and the prognosis shifts to a problem that will be life-long and potentially life-shortening, the situation needs to be reframed and reanchored.

Indeed, a change in clinical status usually causes people to reframe their understanding of a situation, altering how they depict it to themselves and others, and shifting their focus regarding what problems they detect. Alongside this process of reframing, family members may also reconsider what had been their previous goals, potentially reanchoring their evaluations of treatment options with a new set of priorities.

A question that can facilitate this process is to inquire: “Given what we now know about what your child is up against, it would help me if I could hear from you what you are hoping for, what you are worried about and what you want to see happen.” Expect, that the first response will be for a miracle, such as for the problem to go away. This is a normal and completely understandable desire and does not indicate that the family is not realistic. After the hope for a miracle is voiced, be patient and gently ask about what other hopes they have. Often, after a pause, a variety of hopes may be expressed: hopes about going home, about not having death occur too soon, about not suffering or having any further invasive interventions, or about being reunited with loved ones. These hopes can then be translated into goals and become the starting point for a conversation about how the different modes of care can support these goals of care.

Second, once these goals are clarified and articulated clearly, they must be disseminated throughout the health care team. While they should be documented in the medical record with sufficient detail that any reader would know what the goals are, the health care team should work together so that the spirit, as well as the letter, of the goals of care are understood by everyone. Often this requires face-to-face conversations.

Third, any agreements about the limits of care – usually documented as a Do-Not-Attempt-Resuscitation (DNAR) or Allow-Natural-Death (AND) order on the patient’s chart – must be incontrovertibly clear to everyone involved making these sorts of treatment decisions for the child. Standardized forms for documenting these orders should be simple and clear, yet sufficiently detailed so that the limits of care can be drawn at a variety of important gradations across the spectrum of treatments, for example from no cardioversion to no medications to support blood pressure, or from no tracheal intubation to no supplemental oxygen. This information must be readily transferable with the patient across settings of care, from an intensive care unit to a general ward and from the hospital to the home. Finally, the DNAR order must not lead to a “Do Nothing” mentality. Instead, by specifying a limit to the invasiveness of care while affirming the goals of care, it should result in a “Totally Committed” attitude about caring for the child. The health care team should work in concert to assure that this attitude prevails.

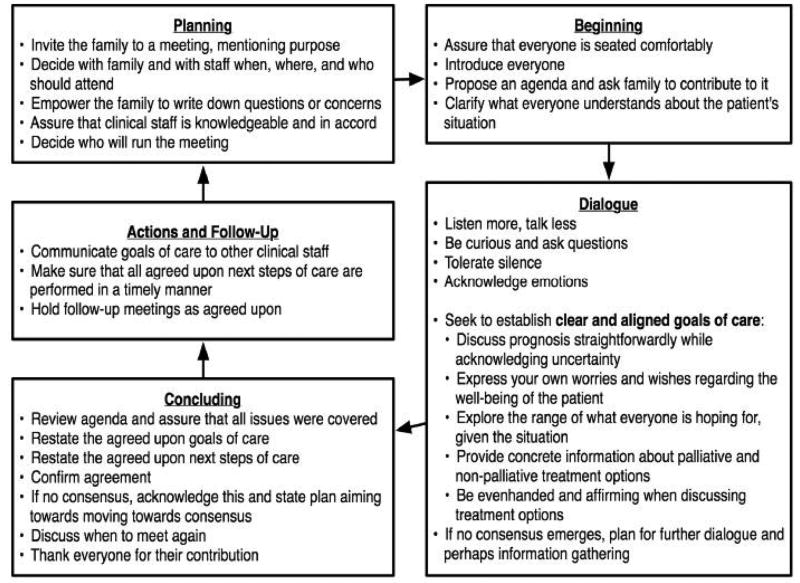

3. CONDUCTING FAMILY MEETINGS

Finding consensus in a plan of action

Family meetings, when clinicians and family members join together to engage in a dialogue and devise a plan of action, are a mainstay of pediatric hospital-based clinical practice. Often the focus of these meetings is determining a consensus of care and can help everyone take stock of the situation and come up with a plan. Surprisingly little is known about how these meetings are run or how to run them better. The advice offered below (and summarized in Figure 9) is based mostly on recommendations that are based on the care of adult patients in intensive care units (43–47), and my own experiences.

Figure 9.

Guidance on Conducting Family Meetings

Since most meetings of this sort do not include the child patient, I will refer to meeting with the family (as opposed to meeting with the patient). The assumption that children do not attend these meetings, however, should be examined case-by-case, as some older children, adolescents, and young adults may very much want to and should be included in these discussions.

Sometimes families request a meeting. However, often a member of the health care team recognizing a need for reframing or reanchoring communication and proposes a meeting to the family.

Planning

Just as planning is a crucial activity for the delivery of bad news, it is equally important for family meetings. In this setting, it is also helpful for the family to be prepared as well.

First, schedule the meeting so that all the people who the patient or family think should be present can attend and make plans so that a private room with adequate space and chairs is reserved. Encourage the family members to prepare themselves for the meeting by writing down any questions, concerns, or ideas that they have so that all of these points can be addressed at the meeting. At the same time, make sure that the participating clinicians are all prepared, having reviewed all available information about the patient’s condition. Decide who among the clinicians will be responsible for running the meeting.

Furthermore, work so that any disagreements between clinicians are identified, addressed and, if possible, resolved prior to the meeting. If disagreements can not be resolved, then develop a plan about how the disagreement will be described to the family, and what plan of action will be used to resolve this disagreement, such as ordering an additional confirmatory test, initiating an empirical trial of therapy, or seeking the opinion of the family. In general, attempting to hide conflicts from families is a dubious and often counter-productive strategy. It is far better to be candid and decide how to manage them.

Beginning

At the scheduled time and place, assure that everyone in attendance is seated comfortably. Have everyone introduce themselves regarding their role in the care of the child. At this stage, the point is to generate an agenda for the meeting and not to discuss each issue as it is mentioned. The clinician running the meeting should propose an agenda and invite the family’s input. For example: “Thanks for coming in this morning. For the next 30 minutes, from my point of view, I think we want to talk about how the patient is doing [using the child’s name], what we think might happen in the next few days, and then make some plans together about how to best care for your child. I also want to know what you want to talk about at this meeting.” Make sure to write down whatever questions, concerns, or ideas that the family mentions, encouraging them to keep getting all these issues “out on the table” at the start of the meeting. Once all the issues are written down, promise the family that by the end of the meeting you will have discussed each of them.

Having formulated the agenda, provide a brief summary of the clinical status of the patient. For instance, suggest that everyone “let me provide a brief 1 or 2 minute overview of the child’s main health problems and the child’s current clinical status”. When the summery is complete solicit questions: “Is there anything about that overview that is new information to anyone, or that you don’t agree with?” If there are no questions to clarify, move on to the dialogue.

Dialogue

How to manage the ensuing dialogue can be divided into advice regarding process and suggestions regarding how to establish clear and aligned goals of care. First, monitor how much the clinicians (including whoever is leading the meeting) are speaking. Try to achieve a balance whereby the family is speaking as much as the clinicians and thus the clinicians are doing more listening. Be inquisitive about what the family is thinking and feeling by intently listening to their thoughts, by asking questions and by respectfully listening to the answers. Allow for periods of silence. Instead of filling the void with your own voice, enable the family to share their thoughts. If emotions are evident, acknowledging and affirming them can be very helpful in creating a supportive, collaborative exchange.

Second, the clarification and alignment of care goals can be fostered by maintaining an empathetic but forthright tone. Present information about the patient’s prognosis, acknowledging any degree of uncertainty in a straightforward manner. Empathy can be expressed, as discussed earlier, by expressing your worries about what might happen to the patient or your wishes regarding how the situation might be different.

Ask the family members to discuss what they are hoping for (as outlined in the previous section). Listing each of the hopes can be transformative. Translate these hopes into a spectrum of possible goals of care for the patient, establishing a concrete framework for evaluating information and making decisions about both palliative and non-palliative care options.

These care options should then be presented in an even-handed manner, seeking to minimize the influence of the biases that heuristic short-cuts of thinking can create. Help the family to visualize what the different courses of treatment could look like, present the benefits and risks in the same order, suggest focusing explicitly on a set of concerns that previously have taken a back seat, and spend roughly equal time discussing each option with similar amounts of detail. If true, let the family know that loving, devoted families choose treatment option A (such as remaining on high-intensity life support) while other loving, devoted families choose treatment option B (such as gathering the family together and holding the child while the life-extending interventions are replaced by comfort-seeking interventions), and that they will be supported with either choice.

At some point in this discussion, a consensus will likely emerge about what the most important goals of care are and how to best pursue them. If consensus is not forthcoming, and the various family members or clinicians are not close to agreement about how to proceed, the leader should shift the discussion to focus on how the conversation can continue and what new information might be gathered to help reach agreement.

Concluding

Once a consensus has emerged, move onward by reviewing the meeting agenda and assuring that all the items were covered adequately, all questions answered and concerns addressed, and a plan of care established. Restate the goals of care and the plan of care. Confirm that everyone agrees.

If a consensus did not emerge, note this fact and the plan for further dialogue in a non-judgmental manner; for example: “Well, today we have talked about many important things and have learned a lot. We still differ in our views about what is the best way to take care of this child, and we have agreed to continue to meet and talk about how to come to an agreement.” Discuss when the next scheduled meeting should take place. Lastly, thank everyone for their time and effort, and end the meeting.

Actions and Follow-Up

The diagram regarding family meeting guidance presents a cyclic pattern, where the planning and conduct of one meeting is linked to subsequent meetings by a phase of action and follow-up that is critical. Meetings are most productive when they guide patient care and positively influence the family’s experience. The consensus goals of care must be disseminated outward from the meeting so that all clinicians are aware of them. If no consensus emerged, then this information too must be disseminated along with the plan regarding how the family-clinical team is working towards consensus. Implement the next steps of care in a timely manner and then abide by the agreed upon schedule for future meetings.

CONCLUSION

Collaborative communication builds the foundation upon which pediatric palliative care of the highest possible quality can be created. While I hope that the material we have covered and the advice offered is helpful to all of us as we strive to work together better, there is still so much to learn about how to improve our communication skills. Let us commit to advancing this area of medical care – through personal reflection and practice as well as rigorous research – so that in the future patients, families, and clinicians can all benefit.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Meyer EC, Ritholz MD, Burns JP, Truog RD. Improving the quality of end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit: parents’ priorities and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):649–57. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hays RM, Valentine J, Haynes G, Geyer JR, Villareale N, McKinstry B, et al. The Seattle Pediatric Palliative Care Project: effects on family satisfaction and health-related quality of life. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(3):716–28. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Back AL, Arnold RM. Dealing with conflict in caring for the seriously ill: “it was just out of the question”. JAMA. 2005;293(11):1374–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.11.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz J Johns Hopkins Paperbacks. The silent world of doctor and patient. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, Tulsky JA. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2476–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Homer CJ, Marino B, Cleary PD, Alpert HR, Smith B, Crowley Ganser CM, et al. Quality of care at a children’s hospital: the parent’s perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(11):1123–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.11.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Caldwell E, Greenlee H, Collier AC. The quality of patient-doctor communication about end-of-life care: a study of patients with advanced AIDS and their primary care clinicians. AIDS. 1999;13(9):1123–31. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199906180-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tulsky JA, Fischer GS, Rose MR, Arnold RM. Opening the black box: how do physicians communicate about advance directives? Annals of Internal Medicine. 1998;129(6):441–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-6-199809150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braddock CHr, Fihn SD, Levinson W, Jonsen AR, Pearlman RA. How doctors and patients discuss routine clinical decisions. Informed decision making in the outpatient setting. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12(6):339–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00057.x. [see comments] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hays RM, Haynes G, Geyer JR, Feudtner C. Communication at the end of life. In: Carter BS, Levetown M, editors. Palliative care for infants, children, and adolescents : a practical handbook. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2004. pp. 112–140. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone D, Patton B, Heen S. Difficult conversations : how to discuss what matters most. New York, N.Y: Viking; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keeney RL. Value-focused thinking : a path to creative decisionmaking. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammond JS, Keeney RL, Raiffa H. Smart choices : a practical guide to making better decisions. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher R, Ury W. Getting to yes : negotiating agreement without giving in. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ury W. Getting past no : negotiating with difficult people. New York: Bantam Books; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ury W. The power of a positive No : how to say No and still get to Yes. New York: Bantam Books; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. 5. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strong C, Feudtner C, Carter BS, Rushton CH. Goals, values, and conflict resolution. In: Carter BS, Levetown M, editors. Palliative care for infants, children, and adolescents : a practical handbook. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2004. pp. 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubler NN, Liebman CB. Bioethics mediation : a guide to shaping shared solutions. New York: United Hospital Fund of New York; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feudtner C. Tolerance and integrity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(1):8–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feudtner C. A piece of my mind: dare we go gently. Jama. 2000;284(13):1621–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKean E. The new Oxford American dictionary. 2. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Habermas J. The theory of communicative action. Boston: Beacon Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Field MJ, Cassel CK Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Approaching death : improving care at the end of life. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1997. Committee on Care at the End of Life. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrell B, Connor SR, Cordes A, Dahlin CM, Fine PG, Hutton N, et al. The national agenda for quality palliative care: the National Consensus Project and the National Quality Forum. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(6):737–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for quality palliative care, executive summary. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(5):611–27. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2004.7.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mularski RA, Curtis JR, Billings JA, Burt R, Byock I, Fuhrman C, et al. Proposed quality measures for palliative care in the critically ill: a consensus from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care Workgroup. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(11 Suppl):S404–11. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000242910.00801.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Field MJ, Behrman RE Institute of Medicine (U.S.) When children die : improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2003. Committee on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Himelstein BP, Hilden JM, Boldt AM, Weissman D. Pediatric palliative care. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(17):1752–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra030334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patrick DL, Starks HE, Cain KC, Uhlmann RF, Pearlman RA. Measuring preferences for health states worse than death. Med Decis Making. 1994;14(1):9–18. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9401400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lynn J. An 88-year-old woman facing the end of life. JAMA. 1997;277(20):1633–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faden RR, Beauchamp TL, King NMP. A history and theory of informed consent. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein GA. Sources of power : how people make decisions. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kahneman D, Slovic P, Tversky A. Judgment under uncertainty : heuristics and biases. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press; 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kahneman D, Frederick S. Representativeness revisited: attribute substitution in intuitive judgment. In: Gilovich T, Griffin DW, Kahneman D, editors. Heuristics and biases : the psychology of intuitive judgement. Cambridge, U.K.; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 49–81. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salovey P, Mayer JD, Caruso D. The positive psychology of emotional intelligence. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, editors. Handbook of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buckman R, Kason Y. How to break bad news : a guide for health care professionals. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quill TE, Arnold RM, Platt F. “I wish things were different”: expressing wishes in response to loss, futility, and unrealistic hopes. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(7):551–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-7-200110020-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedrichsen MJ, Strang PM, Carlsson ME. Receiving bad news: experiences of family members. J Palliat Care. 2001;17(4):241–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Contro N, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen H. Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(1):14–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Contro NA, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen HJ. Hospital staff and family perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1248–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0857-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kahneman D, Tversky A. Choices, values, and frames. New York Cambridge, UK: Russell sage Foundation; Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.West HF, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Curtis JR. Expressions of nonabandonment during the intensive care unit family conference. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(4):797–807. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Rubenfeld GD. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(8):844–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1267OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boyle DK, Miller PA, Forbes-Thompson SA. Communication and end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: patient, family, and clinician outcomes. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2005;28(4):302–16. doi: 10.1097/00002727-200510000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boyle D, Dwinnell B, Platt F. Invite, listen, and summarize: a patient-centered communication technique. Acad Med. 2005;80(1):29–32. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lautrette A, Ciroldi M, Ksibi H, Azoulay E. End-of-life family conferences: rooted in the evidence. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(11 Suppl):S364–72. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237049.44246.8C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]