Abstract

Researchers have questioned whether the addictions treatment infrastructure will be able to deliver high quality care to the large numbers of people in need. In this context, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) and Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) created a nationwide network to improve access and retention in treatment. Applicant agencies described results of an admissions process “walk-through.” This qualitative study used narrative text from 327 applications to RWJF, focusing on admissions-related problems. We developed and applied a coding scheme, then extracted themes from code-derived text. Primary themes described problems reported during treatment admissions: poor staff engagement with clients, burdensome procedures and processes, difficulties addressing the clients' complex lives and needs, and infrastructure problems. Sub-themes elucidated specific process-related problems. Though findings from our analyses are descriptive and exploratory, they suggest the value of walk-through exercises for program assessment and program-level factors that may affect treatment access and retention.

Keywords: Substance abuse treatment, process improvement, admissions, access, retention in care

1. Introduction

Substance abuse problems are a major source of dysfunction and reduced quality of life, and have high economic, medical, family, and social costs (Donnermeyer, 1997; Mark, Woody, Juday, & Kleber, 2001; Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2004; Rosenheck & Kosten, 2001; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2004). Despite these negative consequences, in 2005 only about 2.3 million of an estimated 23.2 million Americans with substance-related problems received some form of treatment, and many who sought help were unable to obtain treatment (SAMHSA, 2006). In addition, only about 51% of those who enter care complete treatment (SAMHSA, 2002). These findings show that substance-related problems remain under-addressed in our health care system, and that significant barriers exist for those who need care.

Such systemic problems suggest that major changes are needed to improve access and delivery of substance abuse treatment, yet poor treatment results have often been blamed on patients with little attention paid to the way care is organized or delivered, or the extent to which available care meets patient needs (Broome, Simpson, & Joe, 1999). Recently, more attention has been focused on treatment facilities, their ability to engage and retain clients in treatment for prescribed lengths of time, and their ability to provide appropriate therapeutic services (Simpson, Joe, Rowan-Szal, & Greener, 1997). Moreover, McLellan, Carise, and Kleber (2003) have questioned whether the addictions service infrastructure, in its current form, can support adequate provision of high quality care.

In addition, a host of treatment access and other difficulties are compounded by problematic “business processes” that negatively affect individuals seeking care (Ebener & Kilmer, 2001). Further, these problems are exacerbated by regulatory requirements that add additional barriers through increased paperwork, assessment requirements, and financial screening (Martin, 2005; Soman, Brindis, & Dunn-Malhotra, 1996). Together, these barriers can hinder initial intake assessments, delay entry into treatment, and lead to missed treatment opportunities (Farabee, Leukefeld, & Hays, 1998; Hser, Maglione, Polinsky, & Anglin, 1998).

To address these problems, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) and the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) created a nationwide effort to identify and address barriers to access and retention in addiction treatment. The RWJF Paths to Recovery initiative and CSAT Strengthening Treatment Access and Retention (STAR) program formed a nationwide learning collaborative called the Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment (NIATx) (Capoccia, Cotter, Gustafson, Cassidy, Ford, Madden, Owens, Farnum, McCarty, & Molfenter, 2007). NIATx provides collaborative learning opportunities and technical support to agencies so they can improve treatment access and retention. NIATx's central tenets are that patient-level outcomes are directly and indirectly affected by agency practices and policies, and by organizational influences (Heinrich & Fournier, 2005), and that process improvement can make organizational systems more consumer friendly, improving outcomes.

Substance abuse treatment agencies seeking participation in the RWJF Paths to Recovery program submitted six-page letters of intent that are the focus of the work presented here. As part of the application process, and as an introduction to process improvement, Paths to Recovery applicants were given instructions for completing an admissions “walk-through” exercise and asked to describe their agency's strengths and weaknesses in their letter of intent, basing their answers on the “walk-through” findings.

Walk-throughs are typically conducted by an employee of an organization, assuming the role of a prospective client and interacting with the organization as would a client. Such walk-throughs enable organizations to better understand their clients' points of view; can uncover assumptions, inconsistencies, and limitations of systems; and can generate ideas for improving organizational processes (Gustafson, 2004). Such patient-centered approaches have increasingly been called for to improve the quality of medical care (Institute of Medicine, 2001).

This paper examines agency and process information submitted as part of the first round of Paths to Recovery letters of intent, focusing on use of patient-centered walk-through exercises and describing potential barriers to treatment identified in the context of these exercises. Based on this work, we describe the organizational processes agencies identified as having the potential to impede access to care or affect treatment continuation.

2. Materials and Methods

The overarching goal of walk-through exercises is to identify problem practices and processes in order to improve service delivery and address customer needs by enabling providers to understand the experience of receiving care from the perspective of patients and their families (Gustafson, 2004). That is, a walk-through answers the question “What is it like to be our customer?” The specific objectives of the walk-through exercises reported here were to 1) identify potential service barriers and process problems experienced by clients attempting to obtain substance abuse treatment, and 2) to uncover methods for reducing or eliminating the problems identified.

2.1. Instructions for the Walk-through Exercise

Applicants were instructed to select two detail-oriented people, committed to enhancing customer service, to play the roles of “client” and “family member.” These individuals were to try to make the walk-through as realistic and informative as possible, and were instructed to choose a particular addiction problem to explore. For example, walk-through clients might present with the profile of a “typical” client or a client of a type the agency identifies as having special needs. Alternatively they might choose to represent a type of client that the agency is concerned about serving well. Applicants were told to let admissions staff know about the walk-through prior to conducting the exercise in order to ensure that staff did not feel undermined, examined surreptitiously, or tricked. Applicants were also reminded that admissions staff would likely be on their best behavior because they knew about the walk-through, and for this reason, that it was important for them to ask staff to treat the walk-through clients as they would anyone else.

Applicants were told to walk-through the admissions process just as a typical client and family member would experience it, starting with the customer's first contact and extending through the third outpatient visit, third day in inpatient care, or through a transfer between levels of care. During this time, walk-through clients were to try to think and feel as a client or family member would think and feel, to be sure to look around, and ask themselves “What might a customer be thinking? How might s/he feel?,” and to document those observations and feelings. Clients were also instructed to ask the staff, at each step in the process, about any changes they could think of that would improve the process for the client or for the staff working with the client, again documenting all ideas and feelings.

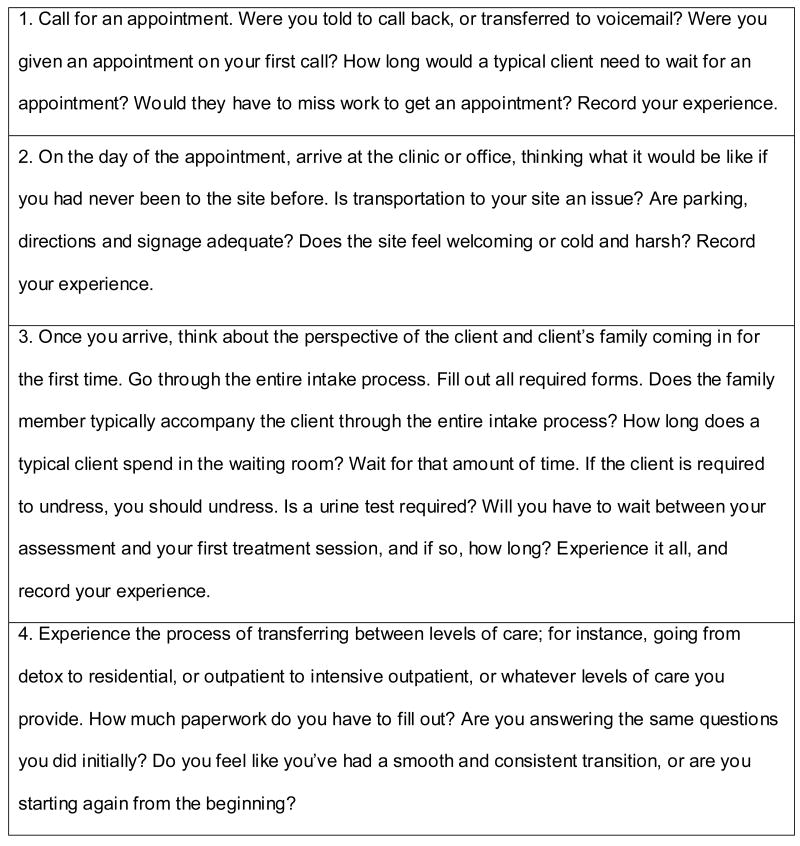

Following the exercise, both the walk-through client and family member were instructed to record a list of the needs and problems identified, and to write a brief report outlining the experience. In this report, they were to answer two questions: (1) What most surprised you during the walkthrough?, and (2) What two things would you most want to change?. In addition to these instructions, agencies were also provided with some additional suggestions, including a series of questions to help direct their focus toward key aspects of the admission process and to guide collection of appropriate and useful information (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Suggestions and questions provided by RWJF to potential Paths to Recovery applicants for use in conducting the walk-through exercise.

2.2. Participants

Paths to Recovery applicants were 327 addiction treatment agencies who submitted a letter of intent to RWJF in the spring of 2003. All applicants were required to have nonprofit status and to serve a client base that was at least 50% publicly funded. Letters of intent also included descriptive information about the agency and its setting (see Table 1), a report of the walk-through findings, and a description of areas for improvement the agencies identified as a primary focus for possible intervention.

Table 1.

Characteristics of agencies that submitted letters of intent for RWJF's Paths to Recovery program

| % of Applicant Agencies

(n = 327) |

|

|---|---|

|

| |

| Treatment settings | |

| Free-standing substance abuse treatment center | 56.4% |

| Mental health agency | 13.3 |

| Hospital or health center | 7.2 |

| Social service agency | 5.5 |

| Family and/or children's service agency | 5.0 |

| Other (local health department, integrated system of care, county jail) | 11.0 |

|

| |

| Location | |

| Urban setting | 75.0% |

| Rural setting | 25.0 |

|

| |

| Organization type | |

| Private not-for-profit organization | 88.41% |

| Unit of state government | 3.05 |

| Unit of local county or community government | 6.71 |

| Unit of tribal government | 1.22 |

| Federal Department of Veterans Affairs | 0.30 |

| Missing | 0.30 |

|

| |

| Region of United States and states represented | |

| Mountain (AZ, CO, ID, MT, NM, ND, SD, TX, UT, WY) | 7.93% |

| Midwest (AR, IA, IL, IN, KS, MI, MN, MO, NE, OH, OK, WI) | 28.35 |

| Northeast (CT, DE, MA, ME, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT) | 23.17 |

| Southeast (AL, DC, FL, GA, KY, LA, MD, MS, NC, SC, TN, VA, WV) | 18.29 |

| West (AK, CA, HI, NV, OR, WA) | 21.95 |

| Missing | 0.30 |

|

| |

| Number of employees (based on full-time equivalents or FTEs) | |

| ≤ 25 FTEs | 23.17 |

| 26 to 50 FTE's | 17.07 |

| 51 to 100 FTE's | 17.07 |

| 101 to 150 FTEs | 10.37 |

| 151 to 250 FTEs | 12.50 |

| ≥ 250 FTEs | 19.82 |

|

| |

| Size of agency boards of directors | |

| 0-10 members | 36.6% |

| 11-20 members | 47.9 |

| 21-30 members | 10.8 |

| ≥ 31 members | 4.7 |

|

| |

| Proportion of agency boards of directors that are minorities | |

| ≤ 10% minority members | 33.2% |

| 11-20% minority members | 25.0 |

| 21-49% minority members | 25.7 |

| 50-99% minority members | 12.0 |

| 100% minority members | 4.1 |

|

| |

| Proportion of agency boards of directors that are female | |

| ≤ 10% female members | 5.9% |

| 11-20% female members | 11.1 |

| 21-49% female members | 54.2 |

| 50-99% female members | 27.6 |

| 100% female members | 1.2 |

|

| |

| Reported proportion of agency boards of directors indicating they were in recovery (n = 212, 115 agencies did not provide these data) | |

| 0% of board in recovery | 17.5% |

| 1-10% of board in recovery | 13.2 |

| 11-20% of board in recovery | 26.8 |

| 21-49% of board in recovery | 26.0 |

| 50-99% of board in recovery | 15.1 |

| 100% of board in recovery | 1.4 |

2.3. Qualitative Analyses

We analyzed text from applicants' letters of intent, focusing on the walk-through exercise and agencies' self-identified strengths and weaknesses. All related text was coded and analyzed using Atlas.ti (Muhr, 1997). Atlas.ti is a software program that aids in the coding and retrieval of qualitative data. Electronic text files are attached to Atlas projects (Hermeneutic Units) and a coding scheme (developed by the researcher or research team) is either uploaded or entered directly into the Atlas.ti project. Trained coders then code by reading text on-line, selecting text that is consistent with a particular code or codes (based on code definitions created by the team), and then applying the appropriate code to the text (electronically, typically via dragging and dropping the code onto the selected text). When text has been coded, the Atlas query tool can be used to retrieve text associated with a particular code or a combination of codes (the latter using Boolean logic). Each query produces an electronic text file that includes all text meeting the criteria specified in the query. Queries identify each separately coded section with the filename of the document from which it was drawn and the line numbers of that document. This allows for easy return to the full document if additional information or clarification of the text is needed.

We used two primary sources of information for developing our coding scheme. First, we began with a list of preliminary descriptive codes derived from eight “promising practices & strategies” for process improvement in addiction treatment settings (Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment, 2006) that were developed based on a systematic literature review of relevant process improvement literature commissioned by the national program office for Pathways to Recovery (Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment, 2007). When the coding scheme was complete, we had included six descriptive categories derived (at least in part) from this review and the eight promising practices. These descriptive codes included: “initial contact,” “assessment/intake appointment,” “levels of care,” “engagement,” “paperwork,” and “family involvement.”

Because this study was exploratory in nature, we also used inductive methods for generating codes. Over a period of several weeks, six of the authors (JF, CG, JW, KR and LB) reviewed the same text from a subset of the letters of intent. For each application, each author independently created a set of descriptive categories or “codes” that reflected what s/he believed to reflect the information found in each application reviewed. The authors then met to discuss the text, line by line, creating a preliminary list of codes that identified common descriptive, pattern, or interpretive components (based on content, relevance, and prevalence) that occurred across the applications reviewed (Lofland & Lofland, 1995; Luborsky, 1994; Miles & Huberman, 1994). During this process we resolved disagreements though discussion, and created and refined the definitions for each code (Leininger, 1985). We then began to independently apply the preliminary coding scheme to text from several additional applications, jointly reviewing the text and associated codes line by line, discussing and resolving cases of disagreement, and finalizing codes and definitions (final n of codes = 39). When agreement across coders was consistently good, the coding scheme was finalized and all documents coded. To maintain consistency, coders were asked to code a new section of text each week for review and discussion during a weekly project meeting.

Once all text was coded, we used the Atlas.ti query tool to produce reports of text related to the admissions process. Themes and subthemes were identified by having two authors independently review all text for each of these queries and create a report of the themes they identified. The first three authors then reviewed, discussed, and consolidated the themes identified. To ensure validity, we also resolved discrepancies and looked for contradictory cases or examples in which the themes did not apply (Bernard, 1994; Miller & Crabtree, 1998; Spradley, 1980). The themes reported in the sections that follow were those that applied to the admissions process and appeared repeatedly in the data. Examples of contradictions are presented with the primary themes.

3. Results

Despite heterogeneity among applicant agencies in treatment processes, philosophies, staffing, and other characteristics, we found four primary themes associated with agency barriers to admissions: poor staff engagement with clients, burdensome procedures and processes, difficulties addressing the complex lives and needs of clients, and problems with infrastructure. We describe these themes (as well as some sub-themes) and provide examples of themes from agency applications. When quotations or our interpretations refer to the experiences of clients, these “clients” are agency staff playing the role of clients as part of the walk-through exercise.

3.1. Poor Staff Engagement and Interaction with Clients

Applicants reported that they found staff members playing a vital role in framing the experience of the client, fostering open communication, and engendering trust, and that information provided by staff, and the ways in which it was provided, could affect client engagement. For example, some applicants reported that information was improperly disseminated or that clients received outdated or conflicting information from staff. Indeed, walk-through clients sometimes received different information and directions for the same treatment agency from different staff members. This misinformation was seen as affecting the client's ability to successfully navigate treatment admission processes, and possibly influence clients' ability to make informed decisions about treatment. In the sections that follow, we describe themes derived from text that related how staff communicated and interacted with clients.

3.1.1. Setting the Tone

Typically, the first contact of a prospective client or family member with the treatment agency was by telephone. One applicant reported that initial contacts have the potential to produce apprehension and uncertainty on the part of the caller, and some agencies were concerned that the success of the interaction during that first call might affect treatment entry. Various walk-through clients (and walk-through “family members”) described frustrations when their initial telephone calls were improperly handled:

The initial phone call was routed incorrectly and then dropped. This was followed by a second phone call that was handled very poorly by a non-clinical admissions staff person such that an appointment was not made.

A total of five different persons became involved in responding to the first caller's inquiry for help, and the caller was passed to different people in an effort to find the right person with whom to speak. Both callers had numerous interruptions due to other calls coming into the agency. In the end, neither caller was able to successfully complete an intake process.

Some walk-through clients mentioned that information provided to them about the treatment program would have been easier to understand and remember if the staff person had been following a well-written script or had clear guidance about information that needed to be reviewed.

There is no universal script at [agency] about what to say during the initial contact, and therefore, the potential client's experience can vary depending on who answers the telephone or receives the client in the waiting area. There is no set process for training those who answer the phone or receive clients at reception.

As a result of these kinds of inconsistencies, some agencies reported that initial contact experiences could be quite different from client to client, even within the same agency. The absence of clear guidelines for initial contacts also was seen as resulting in incomplete information being provided to clients about treatment, particularly regarding paperwork requirements. Failures by staff to relay important information were identified in some agencies as having the potential to produce unexpected financial or other difficulties, and caused some clients to distrust the reliability of future information. For example, one client described not being instructed to bring required financial documents which would have necessitated an additional trip to the clinic had he been an actual client. Worse, some applicants discovered that staff disseminated incorrect information that could affect access to treatment. As an example, one agency found that walk-through clients were erroneously told that a school or family court would have to make a referral when that was not the case, and reported that the time associated with obtaining an external agency referral could increase the time between first contact and treatment admission.

Some applicants also identified improved telephone protocols as having the potential to address another problem they encountered—the assumption that the consumer knew about substance abuse treatment procedures and practices.

Clients are assumed to be knowledgeable about treatment and the various levels of treatment available. This is not always the case. The first question the posing client was asked on the telephone was, “Do you want outpatient or inpatient treatment?” The staff person answering the telephone is assuming the client knows the difference and can make that determination.

Other applicant agencies reported that their staff had provided complete and accurate information at the initial telephone call and beyond. These interactions included well-presented information about the agency, including funding and treatment options.

The client was given explicit written instructions on the next step, including where to go for initial counselor and group meetings and what to expect at that time.

The substance abuse secretary did a good job explaining the state-funded plan for low-income clients. When she had to check on the client's question, she came back quickly with the answer.

3.1.2. Facilitating Understanding of the Treatment Process

Although sharing information with clients is often considered a “patient-centered” practice, in some agencies the information provided at the assessment visit was noted as overwhelming and confusing, making comprehension difficult and potentially impairing the client's ability to make decisions about treatment options. Agencies discovered that simply being “informed” was not sufficient to support successful entry into treatment, particularly for those whose cognitive capacity was diminished as a result of their substance use or comorbid mental health problems. For example:

There was a lot of information to absorb, and it was confusing to have the treatment program revealed piecemeal.

Another applicant noted that the walk-through clients “were given so much information they could not remember it all, and they ended up not being sure of when their appointment for orientation was scheduled.” As a result, clients and staff may end up with contradictory expectations about important aspects of care, such as length and intensity of treatment.

In addition to providing patients with information, the admissions process affords an opportunity for engaging the client and forming a therapeutic alliance. Some walk-through clients reported that their agency did not perform well with regard to encouraging client participation or making clients feel comfortable about entering treatment.

The intake and follow-up…was not very engaging. The intake was dominated by a series of questions required to meet regulatory requirements. As a result, the intake felt somewhat rushed and formulaic. It did not feel as if there was much time for finding out how the program worked. The intake appointment ended with a recommendation for a group and only a vague sense that the intake clinician would serve as a “primary clinician.” There was little sense that the clinician would be “checking in” to make sure the client was seeing a benefit.

At the same time, attributes or qualities in staff members that enhance the admissions process can be elusive. One participant noted that she missed “the kind of personal attention that would be reassuring to a client.”

On the other hand, applicants reported many examples of staff performing well at recruiting, engaging, and retaining clients. In these instances, agency staff were often thorough, sympathetic, and caring in their interactions with clients. Such examples can provide useful information for agencies that want to improve these processes.

At the intake appointment, a counselor walked the client through several forms to further identify treatment needs. The counselor, who was extremely empathetic toward the client's frustration with the involved intake appointment, informed her of the program process and of her rights during treatment.

3.2. Burdensome Procedures and Processes

Walk-through clients identified various procedural problems that could create barriers to treatment and negatively affect client engagement. A common concern was the length of time required to successfully complete intake procedures. Other observations included frustration with the overwhelming amount of paperwork and forms, redundancies in paperwork, and the sometimes mechanical and routine feeling of the intake. Examples follow:

3.2.1. Slow Processes

Among problems noted by applicants was the need for improving the speed—and therefore the method—by which they moved clients through the intake process. Most commonly, the length of time from the first point of contact to completion of the assessment was deemed unacceptable. One walk-through client, who described the process as “stressful and frustrating,” noted that a two-week wait to be admitted into the program made her feel “scared and devalued.” Long delays and burdensome processes between first contact and scheduling an assessment appointment were also identified as having potential to increase client no-show rates. The following provides one example of the kinds of burdensome processes applicants identified:

[Client] was informed about the waiting list and that he needed to call in to the receptionist to be put on the waiting list. He would then need to call on three separate days during each week to remain active on the waiting list until his slot became available. If he failed to do that he would be dropped from the waiting list.

Walk-through clients also found themselves disappointed by the length of time it took to get an initial appointment—in some cases more than two months. Long waits were seen as fueling anxiety in already uncertain clients and family members, and delays were expected to affect whether or not a patient continued seeking treatment. The following examples were provided by agencies that treated adolescents:

The [walk-through] “parents” who were distraught and seeking urgent help were very frustrated at being referred from one department to another, only to learn then that it would be five days before an assessment could be completed, an additional week of delay before outpatient treatment could begin, and nearly two months to gain admission to inpatient services.

The [client] made it through the Orientation/Intake process easily … Asked when [client] could begin treatment, [staff] stated that the wait for treatment could be from six to eight weeks. … Both the client and the family member were disillusioned with this long wait, especially since the telephone screening and intake procedure had been handled so expediently. The family member became especially anxious about the wait, stating that surely the client would relapse during that time and might be unwilling to come to treatment by then.

Some applicants noted unacceptable time lags between the collection of client information, gaining an evaluation appointment, and progressing to the next level of care. One applicant stated that time delays in the intake process would “irritate and discourage the client” and increase the likelihood of treatment drop out. In some instances, the length of the intake process and access to services varied by level of care.

Walk-through clients who presented with substance abuse problems with comorbid mental illnesses voiced additional concerns. Some encountered long waits that were identified as particularly problematic for people with dual diagnoses, or for those who had needs for psychiatric medications that were not addressed. In the following example, the client's need for medication was addressed, but other delays and process problems were uncovered:

My [co-occurring disorder] status is discovered after I mention “my bipolar illness” after 45 minutes. Another counselor is called, I am told to call “dual diagnosis” intake (2 offices away), and am informed that “most dually diagnosed clients come through the Intake Group.” I call, get a busy signal for 20 minutes, leave a message, and get a call back on Tuesday with an appointment for Friday 1pm. I attend my intake and have to “wait” for a call for my Psychiatric evaluation. They call Tuesday with an appointment Thursday 6pm. I attend my appointment, am deemed eligible, and am told I will be on a waiting list “for up to 3 weeks.” I'm asked “do you have a month's medication or do you need a prescription?”

3.2.2. Redundancy in Processes

Applicants also expressed concerns over the repetition that occurred in the intake process and the intake paperwork. Duplication, such as multiple and repeat administration of assessments for placement, led to frustration among clients. Irritation also resulted when redundant information was gathering within a single visit, when information provided in prior visits was not used in subsequent visits, and when information collection was duplicated during transitions from one level of service to another. One applicant noted that redundant data collection during intake processes appeared designed to meet the needs of the agency rather than the needs of the client.

One of the most salient observations about this process [intake] was that there is way too much redundant data gathered in this process. Mr. Doe's [walk-through client] medical history was requested three times in detail.

Several clients were also surprised and dissatisfied with the number of staff they were required to interact with during intakes, often answering duplicative questions.

…the client…became frustrated with the repetition of questions posed by the counselor and then the nurse.

In addition to inducing client fatigue, some applicants were concerned that redundancy and lengthy paperwork could interfere with the creation of a successful relationship with providers:

The diagnostic interview lasted for two hours, but the need for (often redundant) paperwork to get done seemed to take precedence over any therapeutic aspect of the interview.

Redundancies in financial assessments and a focus on finances to the exclusion of client needs were also perceived negatively by some walk-through clients. In addition, treatment could be delayed while the agency worked to confirm insurance, and costs were seen as having the potential to impede treatment entry.

The women [walk-through clients] felt that the paperwork seemed to take too much time and that too much focus was placed on the client's financial situation. For an individual already burdened by legal issues and a drug problem, the invasive nature of these questions, and the implication that the client should contribute financially to his/her treatment to the extent possible, may well serve as a deterrent to seeking treatment.

If the patient is not aware of the sliding fee program the apparent cost of treatment may seem prohibitive…

3.3. Difficulties Addressing Clients' Complex Lives and Needs

By the time people seek treatment, they are often in considerable distress and may be experiencing multiple emotional, medical, financial, housing, family, and social problems. A recurrent theme in the Paths walk-throughs concerned missed opportunities for addressing these issues, with several applicants noting that there was little if any support available to assist patients struggling with various complexities, including language barriers. One applicant noted that such problems could be compounded when walk-through family members (who often provide support to individuals with difficult lives), were excluded from planning and treatment. Language barriers between clients and staff were also reported as lengthening an already long intake process.

One “client” remarked how long it actually takes to conduct an assessment in a non-English language. Intake and assessment questions are long and unfamiliar, and much effort is required to accurately capture the necessary information.

3.3.1. Mental Health and Comorbidities

A number of walk-through clients who presented with comorbid mental health problems were turned away from treatment because dual-diagnosis programs were full, or more often, because substance abuse treatment programs did not provide mental health services while mental health programs did not provide addiction services. An adolescent treatment facility applicant expressed concern for the “youth who fall through the cracks each year,” unable to access the services they need for co-occurring disorders, indicating:

They are either sent to psychiatric services or substance abuse services, when they need a combination of both.

In the few agencies that provided integrated treatment, Paths to Recovery walk-through clients found that they had to “jump through several hoops” to receive care for both mental health and substance abuse. For example:

Consumers with co-occurring disorders (if not identified through our Substance Abuse Unit) are categorized into one of two headings: Substance Abuse or Mental Health. Time constraints, physical location, multiple screening and assessments, waiting time for referral to other units, all add to the prospective client's barriers to quality care and service.

These barriers triggered additional steps in the intake process that could serve to create longer delays for clients with co-occurring disorders.

3.3.2. Court- and Child Welfare-mandated Clients

Mandated or court-referred walk-through clients who presented seeking treatment to resolve or avoid legal consequences were faced with additional barriers to treatment entry. These applicants reported that a lack of coordination between courts and agencies resulted in significant frustration, and that without appropriate linkages or mechanisms to share information, the client from the court system had to repeat paperwork at the treatment agency, adding time and tedium to the process of seeking treatment. Some mandated clients also reported concerns that they would face incarceration if the agency was not able to admit them quickly.

The client …had to play “telephone tag” with the case manager for several days before contact was made. This was very frustrating to her because a court appearance was upcoming and she was threatened with jail if she was not in treatment by that date.

3.3.3. Clients with Disrupted Lives and Limited Resources

Individuals with substance abuse problems often have mobile, turbulent lives and may not have access to a consistent telephone for making or receiving calls. This applicant noted that access to a telephone could be been very important during the three-day delay to intake:

Clients may not have a phone, [and] often are transient, so contacting them may be difficult. In three days they may have changed their mind…gone back out using, etc. It delays the opportunity for intervention and the client feels unimportant or disposable.

Walk-through clients also presented with transportation challenges that could interfere with their ability to reach the treatment agency and compromise their ability to seek treatment in a timely manner. Agency responses were sometimes found to be inadequate and other transportation options limited.

Logistics play an important role in having clients initiate and remain in treatment. Many, if not most, of our clients are dependent on public transportation. [City] has few options for transportation except the bus line, which runs infrequently at best. Most treatment programs are spread out away from the neighborhoods where people live—an average bus trip is 1 hour. With this, clients may be asked to go to different sites for different purposes—one for funding approval, one for intake, one for programming, one for AA/NA. This makes seeking and maintaining treatment services costly in terms of time and money.

The lack of adequate transportation or parking, combined with limited appointment times and the need for childcare, was also perceived as affecting the timing of treatment entry.

All the appointments were during “traditional work hours,” and parking and childcare are not available.

For walk-through clients whose role included having small children, some found that inadequate access to childcare was a complete barrier to treatment participation.

Clients are not able to be seen if they come in with children. No childcare or activities for children were offered.

3.4. Problems with Infrastructure

Intake process barriers, such as repetitive paperwork, did not exist in isolation. Some applicants noted that poorly designed intake processes combined with other problems such as antiquated phone systems, crowded waiting rooms, “uncomfortable chairs,” and “unpleasant bathroom facilities” to create an environment where engagement between the client and the treatment agency could be disrupted. Applicants identified several types of infrastructure problems:

3.4.1. Poor and Antiquated Telephone Systems

Applicants reported various problems with telephone systems. Walk-through clients often reached automated systems that dropped their calls or routed them to an individual who was not able to resolve their request. In other instances, the phone system was circuitous or made it impossible to reach a “live” person to request services or answer questions.

The initial call into the system is very confusing, even before the caller hits a “live” person, the voice prompts, and even the agency listing in the phone directory, are vague and unclear. Finding us is difficult.

The process was especially frustrating when the system required the prospective client to know names or numbers of program personnel in order to be connected, as some applicants discovered. Applicants were also concerned that those without telephones would give up when faced with needing to leave a message for a return call, or about delays related to “playing telephone tag” when a “live” person was not available.

The Urgent Care department (which schedules intake appointments and does a quick phone screening) receives 30-50 calls a day. Most callers leave a message in voice mail and it may take several days of voice mail phone tag before the client actually talks to an Urgent Care staff member for an initial screening and scheduling of the intake appointment.

Not all treatment agencies had inefficient telephone systems, however, some walk-through clients reported encountering robust systems that routed them quickly and efficiently. A few discovered they were able to reach a “live” person “24/7.” Likewise, some agencies operated state-of-the-art call centers capable of quickly linking clients with the appropriate treatment within their agency. These instances provide positive examples for process improvements that might be implemented elsewhere.

By far, the greatest strength of [Agency] is our Customer Service Center, which utilizes customized computer technology and telephone linkages to respond to all new requests for services…

3.4.2. Inadequate Intake Facilities

Walk-through clients also noted a lack of privacy and other problems in their waiting rooms and intake facilities. Concerns included crowded waiting areas, lack of confidentiality in waiting areas (“all conversation at the front desk could be overheard”), and intake rooms that did not provide adequate privacy.

They [walk-through clients] felt at ease with all staff, but felt somewhat uncomfortable in the waiting room because of who might walk in and see them.

The assessment in this group was conducted in a large room with the other potential clients sitting around—no privacy for initial individual contact.

Because substance abuse treatment can be stigmatizing (Link, Struening, Rahav, Phelan, & Nuttbrock, 1997; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005), treatment entry can depend upon the patient perceiving an atmosphere of confidence and trust in which he or she is willing to divulge uncomfortable facts and issues that may be germane to treatment. In the absence of this perception of confidentiality, agencies were concerned that some individuals with substance abuse disorders might refuse or fail to seek treatment, going without needed services.

4. Discussion

These qualitative analyses provide important information about admissions processes at substance abuse treatment agencies from the perspective of would-be consumers, and about the value of using walk-through exercises as a method for learning about consumer perspectives. Our findings highlight a series of problems that, if common across other agencies, could hamper efforts to successfully engage individuals in substance abuse treatment. These results also suggest that walk-through exercises provide valuable information that may assist agencies and providers in targeting and framing process improvements for the greatest impact.

The details of the exercises reported here also suggest processes that other agencies or clinicians may want to explore when they conduct walk-through exercises. For agencies that are already aware of problems in their admissions process, our findings provide information about possible opportunities and methods for improvement. For example, client-level complexities offer opportunities for improving the system broadly, perhaps by adding ancillary or wrap-around services or case management functions. Addressing telephone systems and procedures may provide a relatively easy avenue for improving client contacts throughout the treatment process. Other possible responses to the kinds of problems identified in our analyses include:

Have a person answer the phone; avoid answering machines and voice mail

Make assessments short and focused on the individual client's clinical concern

Avoid repetition during the admissions process

Identify common client needs, such as need for day-care, transportation, and mental health services, and create systems to address these issues when they arise

Ensure confidentiality by having assessments occur in private settings

Eliminate delays

Make sure consumers know what to expect from treatment

While such changes may seem difficult to implement, organizations now participating in the NIATx program have found that seemingly minor changes have the potential to improve consumer experiences in important ways. As one example, NIATx agencies have begun to adopt more “mindful,” client-centered approaches—those involving enhancing trust, caring, expertise, and an appropriate amount of autonomy. Such methods can help clients (who may otherwise feel devalued) experience a sense of receiving individualized and attentive care (Epstein, 1999). They can also help make intake processes easier to complete, more timely, confidential, rapport-building, and oriented toward the goal of engaging individuals in treatment, thus affording clients opportunities to develop relationships with program staff.

Finally, the richness of these data, which come from a large number of agency applicants adopting a consumer lens, suggests that clients themselves should also be considered a relevant resource for developing innovative solutions to addressing barriers to substance abuse treatment. In the absence of client assessments, or in combination with them, walk-throughs can help providers understand clients in ways that can produce the “deep knowledge of the underlying needs of the individual patients served…” that is needed to provide high-quality care (Berwick, 2005, p. 325).

4.1. Study Limitations

The data presented here are from letters of intent submitted by agencies seeking funding. As such, the accounts of their walk-through exercises are necessarily streamlined and were likely presented in ways the agencies expected would appeal to the funding agency. The data are useful, however, in that they are, to our knowledge, the first presentation of a systematic exercise by a large number of substance abuse treatment agencies to understand consumer perspectives and identify problematic agency processes. However, even with the large number of agencies represented, the characteristics of these agencies may not be representative of the field in general. The extent and depth of the problems identified, however, provide indications that agencies were reasonably candid in their reports.

4.2. Implications and Future Research

Our findings suggest that when admissions processes are burdensome, much can to be done so that such processes more closely reflect client, rather than agency, needs. Our findings also imply methods treatment agencies might adopt to create more accessible, efficient, and welcoming settings for clients. Although it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss solutions undertaken by treatment agencies to address the barriers discovered from the walk-throughs, other research suggests that treatment agencies who offer walk-in appointments; use reminder phone calls; or help facilitate client linkages between levels of care (e.g., residential to outpatient) can reduce barriers to treatment, time required to enter treatment, and assessment “no-shows,” and also engage clients more successfully in the next level of care (Capoccia, Cotter, Gustafson, Cassidy, Ford, Madden, Owens, Farnum, McCarty, & Molfenter, 2007; Molfenter, Zetts, Dodd, Owens, Ford, & McCarty, 2005). Future research should consider the bi-directionality of the intake process and how the complex lives of clients affect this process. Clients themselves may also be an important source for identifying areas for future system improvements.

Acknowledgments

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment support the Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment through grants and cooperative agreements. Awards to the University of Wisconsin (RWJF 48364; CSAT-SC-04-035) and Oregon Health & Science University (RWJF 46876 and 50165; PIC-STAR-SC-03-044) supported the preparation of this manuscript. The authors would like to thank Beth Hribar and Eldon Edmundson for their help with coding, Martha Swain for her help with editing, and Dennis McCarty for commenting on an earlier draft.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bernard HR. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Second. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Berwick DM. The John M. Eisenberg Lecture: Health services research as a citizen in improvement. Health Services Research. 2005;40:317–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broome KM, Simpson DD, Joe GW. Patient and program attributes related to treatment process indicators in DATOS. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;57:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capoccia VA, Cotter F, Gustafson DH, Cassidy EF, Ford JH, Madden L, Owens BH, Farnum SO, McCarty D, Molfenter T. Making “Stone Soup”: Improvements in Clinic Access and Retention in Addiction Treatment. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2007;33(2):95–103. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control, Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. Substance abuse treatment for injection drug users: A strategy with many benefits. [On-line]. Available: www.cdc.gov/idu. [Google Scholar]

- Donnermeyer JF. Rural Substance Abuse: State of Knowledge and Issues. NIDA Research Monograph 168. 1997 see RC 023 179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebener P, Kilmer B. Barriers to Treatment Entry: Case Studies of Applicants Approved to Admission. Santa Monica: Phoenix House/RAND Research Partnership; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein Ronald. Mindful Practice. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:833–839. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farabee D, Leukefeld CD, Hays L. Accessing Drug-Abuse Treatment: Perceptions of Out-of-Treatment. Journal of Drug Issues. 1998;28:391–394. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich CJ, Fournier E. Instruments of policy and administration for improving substance abuse treatment practice and program outcomes. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35:481–500. [Google Scholar]

- Hser Y, Maglione M, Polinsky ML, Anglin DM. Predicting Drug Treatment Entry Among Treatment-Seeking Individuals. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15:213–220. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson D. Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Information Gathering Tools: Walk-through (IHI Tool) 2004 Retrieved May 9, 2006 from http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/LeadingSystemImprovement/Leadership/Tools,Walk-through.htm.

- Institute of Medicine & Committee on Quality Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Leininger M. Qualitative Research Methods in Nursing. Orlando, Fl: Grune and Stratton; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, Phelan JC, Nuttbrock L. On stigma and its consequences: evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:177–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofland J, Lofland LH. Analyzing social settings: a guide to qualitative observation and analysis. 3. New York: Wadsworth Publishing; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky MR. The identification and analysis of themes and patterns. In: Gubrium J, Sankar A, editors. Qualitative methods in aging research. New York: Sage Publications; 1994. pp. 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Mark TL, Woody GE, Juday T, Kleber HD. The economic costs of heroin addiction in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;61:195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LL. Performance-Based Contracting for Human Services: Does It Work? Administration in Social Work. 2005;29:63–77. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Carise D, Kleber HD. The national addiction treatment infrastructure. Can it support the public's demand for quality care? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;25:117–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Clinical research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 1998. pp. 292–314. [Google Scholar]

- Molfenter T, Zetts C, Dodd M, Owens B, Ford J, McCarty D. Reducing Errors of Omission in Chronic Disease Management. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2005 October;19(5):521–523. doi: 10.1080/13561820500305151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhr Thomas. ATLAS.ti 4.1 - Short User's Manual. Scientific Software Development; Berlin: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment (NIATx) Literature Review of Key Paths to Recovery. Retrieved February 12, 2007 from http://chess.chsra.wisc.edu/NIATx/Content/ContentPage.aspx?NID=209.

- Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment (NIATx) Promising Practices & Strategies. Retrieved December 22, 2006 from http://chess.chsra.wisc.edu/NIATx/Content/ContentPage.aspx?NID=49.

- Office of National Drug Control Policy. Publication No. 207303. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President; 2004. The economic costs of drug abuse in the United States; pp. 1992–2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R, Kosten T. Buprenorphine for opiate addiction: Potential economic impact. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;63:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Rowan-Szal GA, Greener JM. Drug abuse treatment process components that improve retention. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1997;14:565–572. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soman LA, Brindis C, Dunn-Malhotra E. The Interplay of National, State, and Local Policy in Financing Care for Drug-Affected Women and Children in California. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1996;28:3–15. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1996.10471710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradley JP. Participant Observation. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. DHHS Publication No. SMA 02-3758. Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2002. Results from the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Volume I. Summary of National Findings. (NHSDA Series H-17). [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. DHHS Publication No. SMA 06–4194. Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2006. Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. (NSDUH Series H–30). [Google Scholar]