Abstract

Synaptogenesis is a highly regulated process that underlies formation of neural circuitry. Considerable work has demonstrated the capability of some adhesion molecules, such as SynCAM and Neurexins/Neuroligins, to induce synapse formation in vitro. Furthermore, Cdk5 gain-of-function results in an increased number of synapses in vivo. To gain a better understanding of how Cdk5 might promote synaptogenesis, we investigated potential crosstalk between Cdk5 and the cascade of events mediated by synapse-inducing proteins. One protein recruited to developing terminals by SynCAM and Neurexins/Neuroligins is the MAGUK family member CASK. We found that Cdk5 phosphorylates and regulates CASK distribution to membranes. In the absence of Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation, CASK is not recruited to developing synapses and thus fails to interact with essential presynaptic components. Functional consequences include alterations in calcium influx. Mechanistically, Cdk5 regulates the interaction between CASK and liprin-α. These results provide a molecular explanation of how Cdk5 can promote synaptogenesis.

Introduction

Interneuronal synapses are highly organized structures consisting of ion channels, receptors and intricate protein complexes that all work together to mediate synaptic transmission and plasticity. To account for this precise organization, a complicated and meticulous synaptogenesis program is likely required. Considerable work has suggested that certain adhesion molecules, such as SynCAM and Neurexins/Neuroligins, are capable of inducing in vitro synapse formation (Biederer et al., 2002; Scheiffele et al., 2000), and that some of these molecules are important for synaptic maturation in vivo (Varoqueaux et al., 2006). On both sides of the synapse, there is strong evidence that scaffolding proteins provide a framework for the synaptic foundation and that they may be amongst the first wave of components recruited to a developing synapse. One such scaffolding protein is the membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) family member CASK.

CASK was discovered in a yeast two-hybrid screen for molecules that interact with neurexins, a family of neuronal cell surface proteins (Hata et al., 1996). The neurexin family contains thousands of different isoforms, generated mainly through alternative splicing, that are primarily expressed in axonal growth cones and at the presynaptic terminal (Dean et al., 2003; Ullrich et al., 1995; Ushkaryov et al., 1992). The ligands for neurexins are neuroligins, a family of neuronal transmembrane proteins that localize to the postsynaptic compartment (Ichtchenko et al., 1995; Rosales et al., 2005; Song et al., 1999). The extracellular interaction between neurexins and neuroligins allows them to function, in a calcium-dependent manner, as heterophilic cell adhesion molecules capable of forming an asymmetric synapse (Nguyen and Sudhof, 1997; Scheiffele et al., 2000). Exogenous neuroligin clusters neurexins, CASK and synaptic vesicles in contacting axons, and induces vesicle turnover in the newly formed presynaptic specialization (Sara et al., 2005; Scheiffele et al., 2000). The neurexin cytoplasmic tail that interacts with CASK is required for this clustering activity (Dean et al., 2003). Furthermore, neurexins, when expressed in nonneuronal cells, can induce postsynaptic specializations in cocultured neurons (Graf et al., 2004). These hemi-synapses suggest that neurexin/neuroligin mediated cell adhesion can influence synaptogenesis and that CASK may act as a presynaptic intracellular scaffolding protein at the maturing synapse.

In support of this potential function, CASK is also capable of interacting with the intracellular domain of another synaptic cell adhesion molecule, SynCAM (Biederer et al., 2002). Similar to neuroligins, SynCAM expressed in heterologous cells can induce presynaptic specializations displaying neurotransmitter release in contacting axons. Unlike neurexins and neuroligins, however, SynCAM forms homophilic synapses in that it is expressed on both sides of the synapse and can homodimerize with itself to mediate synaptogenesis.

The purpose of scaffolding proteins at the synapse is to support protein-protein interactions and clustering so that the architecture promotes efficient synaptic function. In vitro synapse formation assays have suggested CASK is amongst the first wave of proteins to be recruited to presynaptic specializations induced by neuroligins (Lee, 2005). CASK interacts with N- and P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channels (Khanna et al., 2006; Maximov and Bezprozvanny, 2002; Maximov et al., 1999; Spafford et al., 2003; Zamponi, 2003) and the adaptor proteins Veli/MALS and Mint1 (Munc18-interacting protein), which are important for neurotransmitter release (Butz et al., 1998; Ho et al., 2003; Olsen et al., 2005; Olsen et al., 2006). Therefore one might predict a cascade of events where neurexin or SynCAM mediated recruitment of CASK to the developing presynaptic terminal could help trigger active zone maturation by stabilizing the adhesion site, promoting function of calcium channels and the release machinery and participating in signaling cascades. Consistent with this hypothesis, CASK RNAi abolishes synaptic transmission in invertebrates (Spafford et al., 2003).

One pathway implicated in regulating the synaptogenesis program involves the serine/threonine kinase Cdk5. While best understood for regulating the cytoarchitecture of the developing brain, emerging evidence supports an important role for Cdk5 at the synapse. Several presynaptic substrates of Cdk5 have now been defined, indicating a direct role for the kinase in the synaptic vesicle cycle (Barclay et al., 2004; Fletcher et al., 1999; Floyd et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2004; Shuang et al., 1998; Tan et al., 2003; Tomizawa et al., 2003). Furthermore, acute Cdk5 gain-of-function results in a dramatic increase in synapse number in vivo that correlates with enhanced learning ability in several behavioral tasks (Fischer et al., 2005). To gain insight into a molecular mechanism detailing how Cdk5 functions to promote synaptogenesis, we investigated the possibility that CASK is a substrate. We found that Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation promotes CASK distribution to developing presynaptic terminals and thereby allows CASK to interact with several presynaptic components including synapse-inducing molecules, the neurotransmitter release machinery and voltage-gated calcium channels. Functionally, we found that this distribution of CASK is important for depolarization-dependent calcium influx. We also have determined a potential mechanism whereby Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation directly regulates the interaction of CASK with liprin-α, a group of proteins that organize the presynaptic active zone.

Results

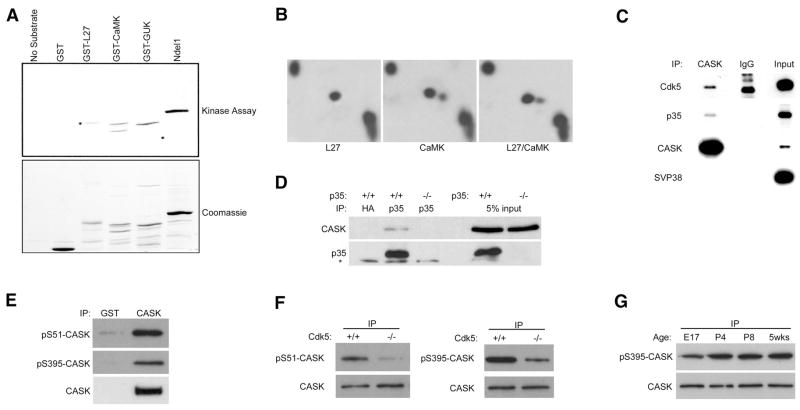

To investigate potential phosphorylation by Cdk5, CASK was divided into different domains that were expressed as GST fusion proteins and used as substrates in an in vitro kinase assay with purified active Cdk5. The autoradiography results show that the L27, CaMK and GUK domains were phosphorylated by Cdk5 to a similar extent as the known substrate Ndel1 (also known as Nudel) (Figure 1A). Next, to determine the sites, we used two-dimensional phosphoaminoacid analysis to distinguish phospho-serine, -threonine and –tyrosine residues. The results suggested that serine residues are the major sites of phosphorylation in the L27 and CaMK domains (Figure 1B), and that threonine residues are primarily phosphorylated in the GUK domain (data not shown). The L27 and CaMK each contain only one serine that can be phosphorylated by Cdk5, indicating that the major sites are Ser 395 and Ser 51 respectively. Likewise, the GUK domain contains only one proline-directed threonine residue, Thr 846. We also processed samples for mass spectrometry and with a combination of data from a cellular system and mouse brain synaptosomes, we were able to detect phosphorylation of CASK at both Ser 51 and Ser 395 (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1. CASK is a Cdk5 substrate.

(a) In vitro Cdk5 kinase assay of CASK GST-fusion domains. Ndel1 (Nudel) is a positive control, GST and Cdk5/p25 without substrate are negative controls. (b) In vitro phosphorylation sites of CASK resolved by two-dimensional phosphoaminoacid analysis. Phosphorylated GST-L27 and GST-CaMK were analyzed alone or in combination as indicated. (c) Membrane fractions from adult mice were solubilized in TX buffer and subjected to IP. (d) Brains from adult mice of indicated genotype were lysed in RIPA and subjected to IP. * indicates IgG light chain. (e) RIPA lysates from E17 mouse brains were subjected to IP. (f) RIPA lysates from E17 mouse brains of wild-type or Cdk5 deficient littermates were subjected to IP. (g) RIPA lysates of brains from indicated mouse age were subjected to IP.

We next tested for an in vivo association between the Cdk5 activator p35 and CASK in brain lysate. Some Cdk5 substrates, such as Amphiphysin-1 (Floyd et al., 2001), bind p35. Immunoprecipitates made with CASK antibodies demonstrated an interaction with p35 and Cdk5 (Figure 1C). Likewise, p35 immunoprecipitates from wild-type mouse brains contained endogenous CASK (Figure 1D). While the total amount of CASK interacting with p35 in this snapshot is small, it is consistent with the transient nature of a substrate-kinase relationship. Also, CASK was not immunoprecipitated from littermate p35 deficient mice or with a control antibody, indicating specificity to the association between CASK and p35.

To analyze phosphorylation of CASK in vivo, we made phosphorylation state-specific antibodies. Phospho-Ser 51 (pS51) and phospho-Ser 395 (pS395) antibodies recognized several bands in brain lysate but only one in samples enriched for CASK by immunoprecipitation (Figure 1E; Supplemental Figure 2), suggesting that both phospho-antibodies recognize a form of CASK present in embryonic mouse brains. Subsequently, CASK immunoprecipitates were made from lysates of Cdk5 deficient or littermate brains and probed for phospho-CASK. While total CASK did not differ between wild-type and Cdk5 knockout mice, pS395 and pS51 levels were markedly decreased in the absence of Cdk5 (Figure 1F). We were also able to detect decreased phosphorylation of CASK by other Cdk5 loss-of-function methods including dominant negative and pharmacological approaches (Supplemental Figure 3). Phosphorylation of T846 did not appear to be a major event in vivo (data not shown). These data indicate that Cdk5 is a major kinase for phosphorylation of S51 and S395 in vivo.

We next examined the temporal profile of CASK phosphorylation in the developing brain. Interestingly, phosphorylation increases slightly during postnatal development and plateaus around P4 while the total amount of CASK remains the same (Figure 1G). Phosphorylation of Cdk5 substrates important for the neuronal migration program, such as FAK, decrease in the postnatal period (Xie et al., 2003). However, this profile suggests a more important role for Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation of CASK during later stages of brain development and the more mature nervous system.

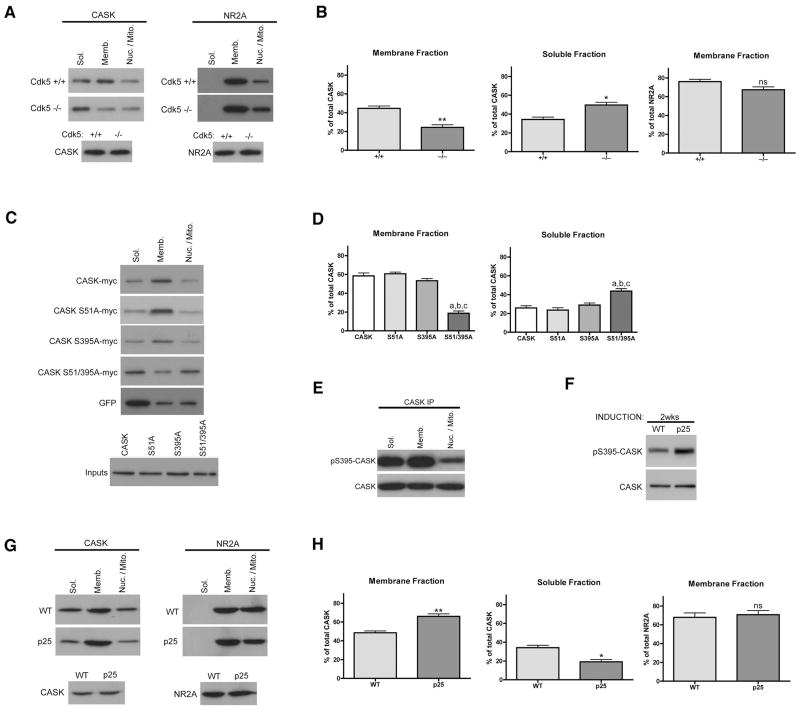

To understand a potential role for CASK phosphorylation, we examined the subcellular distribution of CASK in Cdk5 deficient mice. We used a series of centrifugations to resolve nuclear/mitochondrial, membrane-associated and cytosolic pools of cellular proteins. In wild-type embryonic brains, the highest level of CASK is in the membrane-associated fraction, with a significant amount also in the cytosol (soluble) (Figure 2A). In Cdk5 deficient brains, however, CASK is significantly reduced in the membrane-associated fraction (Figure 2A–B) (44.6±2.6% vs 24.4±2.8% of total CASK is membrane-associated; Mean±SEM; control vs KO/mutant), while the soluble pool of CASK is increased (34.3±2.5% vs 49.7±2.9% is soluble). In comparison, the NR2A subunit of NMDA receptors, another Cdk5 substrate, is not altered when comparing control and Cdk5 deficient membrane fractions (Figure 2A–B). These data indicate Cdk5 activity is necessary for the appropriate membrane localization of CASK. This is an intriguing result as CASK is a member of the MAGUK family, proteins that play significant intracellular scaffolding roles at cellular membranes.

Figure 2. Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation mediates membrane association of CASK.

(a) Wild-type or littermate Cdk5 deficient E17 brains were subjected to subcellular fractionation. Soluble (Sol.), membrane (Memb.) and nuclear/mitochondrial (Nuc./Mito.) fractions are indicated. (b) Relative amounts of CASK or NR2A in each fraction were determined by densitometry and totaled. Student’s t-test was used and n=3. ** indicates p=0.0059, * indicates p=0.0162 and ns means not significant. (c) CAD cells cotransfected with Cdk5, p35 and indicated construct were differentiated and fractionated. (d) Relative amounts of myc-tagged CASK in each fraction were determined by densitometry and analyzed by One-Way ANOVA. For membrane fraction a: S51/395A vs CASK, p<0.001; b: S51/395A vs S51A, p<0.001; c: S51/395A vs S395A, p<0.001. For soluble fraction a: S51/395A vs CASK, p<0.01; b: S51/395A vs S51A, p<0.01; c: S51/395A vs S395A, p<0.01. (e) E17 brains were fractionated and equalized for CASK levels by overloading non-membrane fractions prior to IP. (f) RIPA lysates from 2 week induced (6–7 weeks old) p25 transgenic mice or wild-type littermates were subjected to IP. (g) Forebrains of two week induced p25 transgenic mice or wild-type littermates were fractionated. (h) Percentages of CASK or NR2A in membrane or soluble fractions for wild-type and p25 trangenic mice were analyzed by Student’s t-test. ** indicates p=0.0063, * indicates p=0.0129, and ns means not significant.

We next determined if elimination of CASK phosphorylation by Cdk5 was directly responsible for this distribution phenotype. To this end, CASK constructs tagged with myc and mutated from serine to alanine at S51, S395, or both, were created. Neuroblastoma CAD cells were cotransfected with the different constructs and active Cdk5, then differentiated and fractionated. Cells expressing wild-type CASK-myc or the single site alanine mutants had a CASK distribution similar to control brains. In cells expressing the double alanine mutant S51/395A, however, the transfected CASK was depleted from the membrane-associated fraction (Figure 2C-D) (58.5±3.2% vs 18.7±2.4% is membrane-associated) and increased in the cytosol (25.8±2.4% vs 43.8±2.6% is soluble), recapitulating the localization phenotype seen in the Cdk5 deficient mice. While similar, this shift in the localization of CASK is even stronger than that seen in the Cdk5 knockout mice, likely due to the residual phosphorylation that remains in the mouse and that the stoichiometry of phosphorylation may be higher in CAD cells. These observations argue that loss of Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation at both S51 and S395 is necessary for removal of CASK from the membrane-associated fraction.

To gain an understanding of the subcellular localization of endogenous phospho-CASK in neurons, we used the pS395-CASK antibody to probe fractions from wild-type embryonic mice brains. Since total CASK is enriched in membrane-associated compartments, an effort was made to equalize all of the fractions prior to immunoprecipitation in order to get a reasonable determination of where phosphorylation was occurring. The results suggest phospho-CASK is enriched in membrane fractions with a significant amount also present in the soluble pool (Figure 2E). This result provides in vivo evidence that endogenous phospho-CASK is present at membranes and supports our data using overexpression of the double alanine mutant in CAD cells and neurons.

Having seen a decrease in phosphorylation and a resulting redistribution of CASK in Cdk5 loss-of-function mice, we next tested if CASK was altered in a Cdk5 gain-of-function model. We employed a bitransgenic mouse model using the tetracycline-controlled transactivator (tTA) system to drive inducible expression of the Cdk5 activator p25 under control of the CaMKII promoter (CK-p25 mice) (Cruz et al., 2003). Bitransgenic mice were raised in the presence of doxycycline for 4–6 weeks postnatal before induction of p25. We then examined CASK phosphorylation and subcellular distribution in CK-p25 mice where the p25 transgene has been expressed for only two weeks. At this timepoint, similar to other Cdk5 substrates such as Pak1 and NR2A (Fischer et al., 2005), CASK phosphorylation was increased in brains from CK-p25 mice (Figure 2F). Furthermore, while in Cdk5-deficient brains CASK was depleted from membranes, in p25-overexpressing brains CASK is more enriched in membrane fractions compared to wild-type littermates (Figure 2G–H) (48.6±1.9% vs 66.0±2.7% is membrane-associated). Also, the cytosolic pool of CASK is depleted in p25 transgenic mice (34.1±2.6% vs 19.2±2.4% is soluble) and NR2A is unchanged in p25 fractions (Figure 2G–H). Taken together, these results confirm that Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation of CASK regulates the subcellular distribution of CASK in a dynamic fashion. As phospho-CASK levels increase, CASK shifts from the cytosolic pool of proteins to a membrane-associated pool.

While this data suggests that Cdk5 activity can directly regulate CASK distribution to membrane-associated pools, we sought to determine what effect Cdk5 activity has on CASK distribution specifically to synaptic membrane-associated pools. To this end, we performed synaptosome preparations using wild-type adult mice brains to determine the distribution of CASK, and more importantly, phospho-CASK. As expected, a pool of CASK was distributed to LP1, the presumptive synaptosomal membrane fraction (Figure 3A). We next performed CASK immunoprecipitations from H (the homogenate or input fraction), LS1 (the synaptosome cytosol) and LP1. Interestingly, we found that phospho-CASK is relatively more enriched in synaptosomal membrane fractions than total CASK (Figure 3B). Finally, we determined if Cdk5 loss-of-function altered CASK distribution to synaptic membranes. Rather than using the Cdk5 deficient mice, which die around birth, we crossed floxed Cdk5 and αCaMKII-Cre (Yu et al., 2001) mice to generate forebrain-specific Cdk5 conditional knockout (Cdk5 cKO) mice. Importantly, CASK phosphorylation was markedly reduced in the Cdk5 cKO mice relative to control littermates (Figure 3C). Preparation of synaptosomes from Cdk5 cKO mouse brains revealed a strikingly altered distribution of CASK relative to control (Figure 3D–E). In synaptosomes from Cdk5 cKO mice, CASK is significantly decreased in the LP1 membrane fraction and increased in the LS1 and LS2 cytosolic fractions relative to control littermates. Importantly, synaptophysin, a synaptic vesicle associated protein, is not altered (Figure 3D–E). This data suggests that Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation in part mediates CASK distribution to synaptic membranes.

Figure 3. Cdk5 mediates CASK distribution in synaptosomes.

(a) Synaptosome preparations were made using adult wild-type mouse brains. (b) CASK IPs were made from synaptosome fractions. (c) RIPA lysates from forebrains of adult Cdk5 cKO mice or control littermates were subjected to IP. (d) Synaptosomal preparations were made using brains from adult Cdk5 cKO or control littermates. (e) Relative amounts of CASK or Synaptophysin in purified synaptosome fractions were determined by densitometry and analyzed by One-Way ANOVA. For CASK, * indicates p<0.05 when comparing LS1 fractions and p<0.01 when comparing LS2 fractions. ** indicates p<0.001 when comparing LP1 fractions. n=3 for both genotypes. AU indicates arbitrary units and ns not significant.

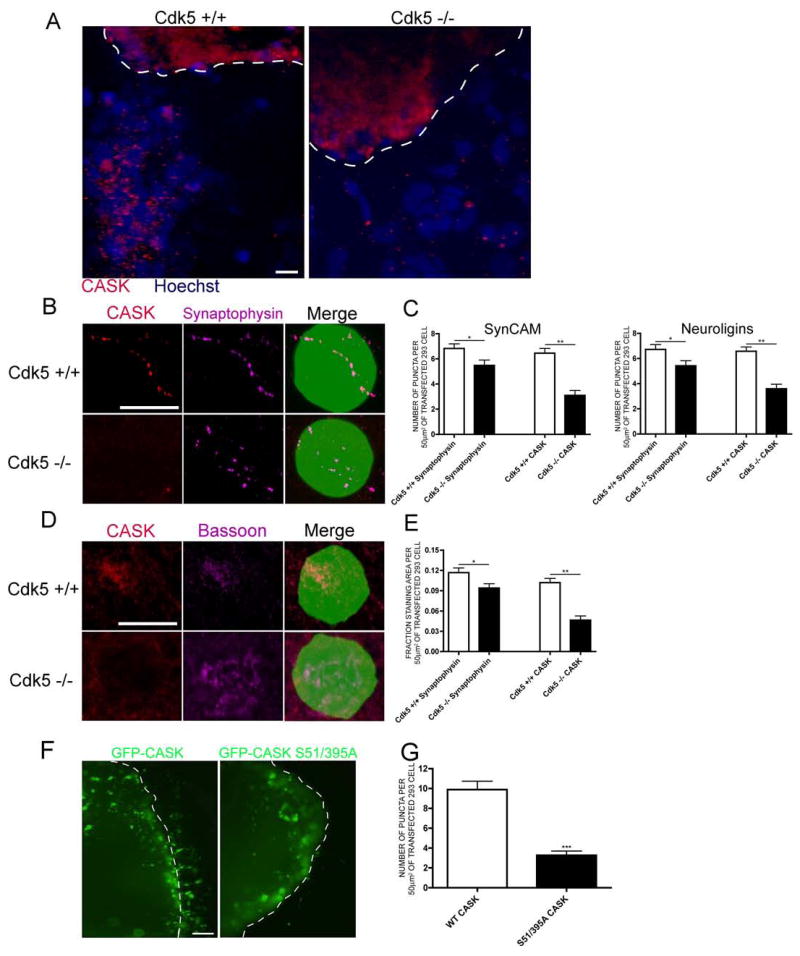

To determine if Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of CASK, and CASK distribution to synaptic membrane-associated pools, is important during synaptogenesis, we used a synapse formation assay where heterologous cells (such as 293) overexpressing a synaptic cell adhesion molecule (such as Neuroligins or SynCAM) are cocultured with pontine explants from late embryonic/early postnatal mouse brains. After a few days, axonal processes emanating from the pontine explants are capable of forming presumptive presynaptic terminals enriched with CASK and presynaptic markers at points of contact with the heterologous cells expressing the synaptic cell adhesion molecules (Scheiffele et al., 2000). We cocultured pontine explants from wild-type or Cdk5-deficient mice with 293 cells expressing SynCAM or Neuroligins. There was no significant difference in the number or length of processes emanating from Cdk5-deficient explants relative to wild-type (Supplemental Figure 4). At low magnification, it is apparent that Cdk5 deficient explants display less clustering of CASK on the 293 cells, which are visualized with Hoechst (Figure 4A). At higher magnification, where the 293 cells are visualized by cotransfected GFP, quantification of the number of puncta per surface area of 293 cell (Biederer and Scheiffele, 2007) demonstrates significantly less clustering of CASK, suggesting that Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation is important for CASK recruitment to developing synapses (Figure 4B–C). In addition, Cdk5-deficient processes demonstrated a mild but significant decrease in the amount of synaptophysin clusters (Figure 4B–C, Supplemental Figure 5), suggesting that Cdk5 is important for synapse formation.

Figure 4. Cdk5 is required for CASK recruitment to presynaptic terminals and for synapse formation.

(a) Pontine explants from E17 wild-type or Cdk5-deficient mouse brains were cocultured with 293 cells expressing SynCAM isoforms. CASK staining is red and Hoechst nuclei are blue. The dashed white line indicates the border of the explant. Scale bar = 10 μm. (b) Pontine explants from E17 wild-type or Cdk5-deficient mouse brains were cocultured with 293 cells expressing SynCAM isoforms and GFP. CASK is red and Synaptophysin is purple. Scale bar = 10 μm. (c) One-Way ANOVA quantification of (b) for 293 cells expressing SynCAM or Neuroligin isoforms. * indicates p<0.05 and ** p<0.001. 40 cells were counted in 3 experiments. (d) Cortical neurons from E17 wild-type or Cdk5-deficient mouse brains were cocultured with 293 cells expressing SynCAM isoforms and GFP. CASK is red and Bassoon is purple. Scale bar = 10 μm. (e) One-Way ANOVA quantification of (d). * indicates p<0.05 and ** p<0.001. 40 cells were counted in 4 experiments. (f) Pontine explants were infected with HSV-GFP-CASK or CASK S51/395A prior to addition of transfected 293 cells. GFP is visualized in green. The dashed white line indicates the border of the explant. Scale bar = 5 μm. Comparison of puncta size with scale bar confirms these are not cell bodies migrating from the explant. (g) Student’s t-test quantification of (f). 40 cells were counted in n=6 experiments for wild-type and n=4 for mutant CASK. *** indicates p<0.0001.

We also used a second assay of in vitro synapse formation to complement the pontine explant experiments. In this assay, cortical neurons were cultured from wild-type or Cdk5-deficient littermates with 293 cells that had been transfected with SynCAM and GFP. In wild-type cocultures, CASK and the presynaptic marker Bassoon clustered at sites of contact with the 293 cells (Figure 4D). However, in Cdk5-deficient cocultures, CASK was often absent at sites of contact where Bassoon accumulated (Figure 4D). Quantification, determined by the fractional area of staining per surface area of 293 cell (Biederer and Scheiffele, 2007), indicated a marked decrease in CASK at developing synapses made by Cdk5-deficient neurons (Figure 4E). There was also a more mild, but significant, decrease in the percentage of 293 cells displaying clusters of Bassoon, once again indicating that Cdk5 activity is important for synapse formation (Figure 4E).

Finally, we infected explants made from wild-type embryonic mice with herpes simplex virus encoding GFP-tagged wild-type or S51/395A CASK and investigated the clusters that formed on 293 cells (Figure 4F). Although these clusters were larger than seen with endogenous CASK (likely due to the overexpression system), comparison of their size with the scale bar indicates they are puncta. Quantification determined that there were significantly fewer GFP-S51/395A CASK clusters (Figure 4G), suggesting that mutation of Ser 51 and Ser 395 limits the ability of CASK to cluster at developing synapses.

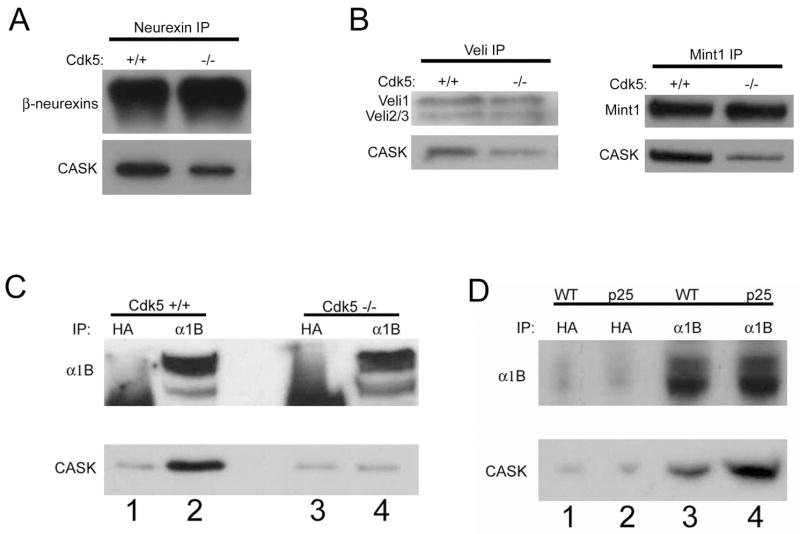

Given that membrane localization and recruitment of CASK to developing synapses is Cdk5-dependent led us to hypothesize that phosphorylation may promote the interaction between CASK and proteins enriched at synaptic membranes. CASK was originally identified as an intracellular interactor of neurexin proteins (Hata et al., 1996), which are the presynaptic partners mediating neuroligin-induced synaptogenesis (Dean et al., 2003; Nguyen and Sudhof, 1997; Scheiffele et al., 2000). Interestingly, CASK association with neurexins is significantly decreased in membrane fractions from Cdk5 deficient mice compared to wild-type mice (Figure 5A), suggesting that CASK interaction with synaptic cell adhesion molecules is also Cdk5-dependent.

Figure 5. CASK interactions with presynaptic proteins are regulated by Cdk5.

(a) Membrane fractions were prepared from E17 wild-type or littermate Cdk5 deficient brains and subjected to Neurexin IPs. (b) Membrane fractions from E17 wild-type or littermate Cdk5 deficient brains were subjected to Veli or Mint1 IPs. (c) Membrane fractions were prepared from E17 wild-type (lanes 1–2) or littermate Cdk5 deficient (lanes 3–4) brains. Fractions were lysed in DOC buffer, dialyzed against .1% Triton buffer and subjected to IP with an α1B (lanes 2 & 4) or control (lanes 1 & 3) antibody. (d) Membrane fractions were prepared from two week induced p25 transgenic mice or wild-type littermate brains. Fractions were subsequently lysed in DOC buffer, dialyzed against .1% Triton buffer and subjected to IP with an α1B (lanes 3–4) or control (lanes 1–2) antibody.

We next examined the interaction of CASK with Mint1 and Veli. The tripartite complex of CASK, Mint1 and Veli is established in mammalian brains (Butz et al., 1998; Olsen et al., 2005; Olsen et al., 2006), and is evolutionarily conserved and well understood in organisms such as C.elegans (Kaech et al., 1998; Simske et al., 1996). Triple knockout mice of all Veli (also known as MALS) isoforms have decreased CASK levels and reduced EPSCs relative to wild-type mice (Olsen et al., 2005; Olsen et al., 2006). Mint1 binds the essential synaptic vesicle exocytosis protein Munc18-1 (Okamoto and Sudhof, 1997), and Mint1 deficient mice have impairments in GABAergic transmission (Ho et al., 2003). As expected, immunoprecipitates of Veli from wild-type mouse brain membranes demonstrate a strong interaction with CASK. However, much less CASK associated with Veli in the absence of Cdk5 activity (Figure 5B). Similarly, Mint1 immunoprecipitates made from wild-type mice membrane fractions contained much more CASK than those made from Cdk5 deficient mice (Figure 5B).

We next examined the interaction of CASK with α1B subunits of N-type calcium channels. This interaction has been demonstrated with GST-pulldowns (the C-terminal tail of α1B interacts with the SH3 domain of CASK in vitro) (Maximov and Bezprozvanny, 2002; Maximov et al., 1999) and immunoprecipitation from chick brain lysate (Khanna et al., 2006). Indeed, endogenous α1B from embryonic wild-type brain membranes coimmunoprecipitated CASK. Intriguingly, endogenous α1B immunoprecipitates made from brain membranes of Cdk5 deficient littermates did not contain CASK (Figure 5C). This result suggests that CASK interaction with N-type calcium channels is abolished in vivo in the absence of Cdk5 activity.

Taken together, our data suggests that in the absence of Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of CASK at Serine 51 and Serine 395, CASK is depleted from neuronal membranes, is not recruited to developing synapses, and has a decreased association with presynaptic machinery, such as N-type voltage gated calcium channels, Veli, Mint1 and neurexins. While CASK displays decreased phosphorylation and depletion from membranes in Cdk5-deficient mice, CASK phosphorylation and localization to membranes is increased in Cdk5 gain-of-function (CK-p25) mice. Therefore, we prepared endogenous N-type calcium channel immunoprecipitates from brain membranes of CK-p25 mice and found that the in vivo interaction between the α1B subunit and CASK is increased relative to wild-type littermates (Figure 5D). This data confirms that Cdk5 promotes the interaction between CASK and N-type calcium channels.

While our data suggests that CASK recruitment to presynaptic membranes and subsequent interactions with essential presynaptic machinery are Cdk5-dependent, we wanted to understand what impact altering these interactions might have in neurons. To this end, wild-type or double alanine mutant CASK was introduced to primary hippocampal neurons using high efficiency electroporation and potential changes in [Ca2+]i in response to high K+ stimulation was assessed. After 10–14 days in culture, ratiometric calcium imaging was performed using the conventional indicator fura-2 AM. Upon depolarization with high K+, calcium influx into untransfected or wild-type CASK transfected neurons was very prominent (Figure 6A–B). However, in S51/395A CASK transfected neurons, the peak change in [Ca2+]i was moderately decreased (Figure 6B). We also found that Cdk5 knockdown, mediated by two distinct RNAi constructs, caused a significant decrease in the peak change in [Ca2+]i (Supplemental Figure 6). This data demonstrates that calcium influx into neurons expressing a mutant form of CASK that cannot be phosphorylated by Cdk5 is significantly compromised.

Figure 6. CASK is important for depolarization-dependent calcium influx in hippocampal neurons.

(a–b) Electroporated primary hippocampal neurons cultured for 10–14 days were loaded with the calcium indicator fura-2 AM. Neurons were stimulated with a depolarization solution containing high K+. Upon depolarization the 340/380 nm excitation ratio was determined and the change in [Ca2+]i was calculated. (a) shows the change in intracellular calcium concentration in response to KCl of an average neuron for each condition. (b) shows a scatter plot of the peak intracellular calcium concentration of all neurons analyzed (n=40 for each group) by One-Way ANOVA. a: S51/395A vs CASK, p<0.001; b: S51/395A vs Untransfected, p<0.01. (c–d) Prior to stimulation with high K+, neurons were treated with 1 μM ω-conotoxin GVIA and 1 μM ω-agatoxin IVA for 30 mins. (c) shows the change in intracellular calcium concentration in response to KCl of an average neuron for each condition. (d) shows a scatter plot of the peak intracellular calcium concentration of all neurons analyzed (n=40 for both groups). By student’s t-test there is no significance (p=0.138). (e) COS7 cells were transfected with indicated constructs and lysed in RIPA. (f) The change in [Ca2+]i in response to high K+ for neurons transfected with indicated constructs are plotted (n=15 for each group). Statistical analysis was performed with One-Way ANOVA. a: CASK RNAi vs CASK, p<0.05; b: CASK RNAi vs Ndel1 (Nudel) RNAi, p<0.05; c: CASK RNAi vs CASK RNAi + CASKrescue, p<0.05. (g) Representative calcium currents recorded from TSA cells stably expressing N-type channels and transfected with CASK or control plasmids. Peak calcium current (Ipeak) and the voltage-pulse paradigm are indicated. Current records were lowpass filtered at 5 kHz and sampled at greater than 25 kHz. (h) Population averages of peak current density (Jpeak) for control or CASK transfected TSA cells. Jpeak was defined as Ipeak divided by cell capacitance.

It has been suggested that CASK interaction with calcium channels is limited to Cav2 channels (Spafford and Zamponi, 2003), so to determine the source of calcium influx primarily affected by double alanine mutant CASK we pretreated transfected hippocampal neurons with ω-conotoxin GVIA and ω-agatoxin IVA, inhibitors of N- and P/Q-type channels respectively. While calcium influx was significantly decreased with the treatment, upon high K+-mediated depolarization a prominent amount was still detectable, consistent with the fact that there are many other sources of calcium influx in neurons. We found that pretreatment with blockers of N- and P/Q-type calcium channels eliminated the significant difference in calcium influx between wild-type and S51/395A-CASK transfected neurons (Figure 6C–D). Pretreatment with APV, which blocks NMDAR-mediated calcium influx, did not eliminate the difference (Supplemental Figure 6). This data suggests that Cdk5-phosphorylated CASK promotes calcium influx primarily through Cav2 calcium channels.

When CASK is not phosphorylated, it does not interact with calcium channels embedded in membranes. Therefore, one way to explain the calcium influx phenotype is that eradication of the interaction with N-type channels is akin to CASK loss-of-function. Therefore, to test our hypothesis that regulation of presynaptic calcium channels is an in vivo function of CASK in neurons, we developed a RNAi construct that knocks down CASK levels (Figure 6E). Furthermore, cells cotransfected with CASK RNAi and CASKrescue, a construct containing a silent mutation in the coding sequence within the region targeted by the CASK RNAi, are able to maintain expression of CASK. While calcium influx was not altered when comparing neurons expressing CASK, Ndel1 (Nudel) RNAi or CASK RNAi in conjunction with CASKrescue, the change in [Ca2+]i was significantly decreased in cells expressing CASK RNAi alone relative to the other conditions (Figure 6F). This data suggests that CASK loss-of-function results in a similar decrease in calcium influx as overexpression of the nonphosphorylatable form of CASK, and that CASK is capable of promoting calcium influx in response to depolarization.

We next sought a more direct means to test the effect of CASK on calcium channels. To this end, calcium currents were recorded through N-type channels (rat α1b, β3, α2δ) stably expressed in TSA cells (Lin et al., 2004) in the presence or absence of CASK. Figure 6G shows exemplar calcium current records evoked with the indicated voltage-pulse paradigm. Intriguingly, CASK causes an amplifying effect. Next we determined the peak current density (Jpeak) by measuring peak calcium current as shown (Ipeak) and dividing by cell capacitance. Population averages are shown in Figure 6H, plotting Jpeak as a function of test-pulse potential (10 mV for the exemplars in Figure 6G). These average data confirm that CASK produces a 2–3 fold enhancement of N-type currents, fitting nicely with the calcium imaging. We also utilized G-Q analysis (Agler et al., 2005) and determined that an increase of channel open probability appears to account for much of the current augmentation by CASK (Supplemental Figure 7). Taken in conjunction with the calcium imaging, this data indicates that CASK is capable of modulating the function of N-type channels.

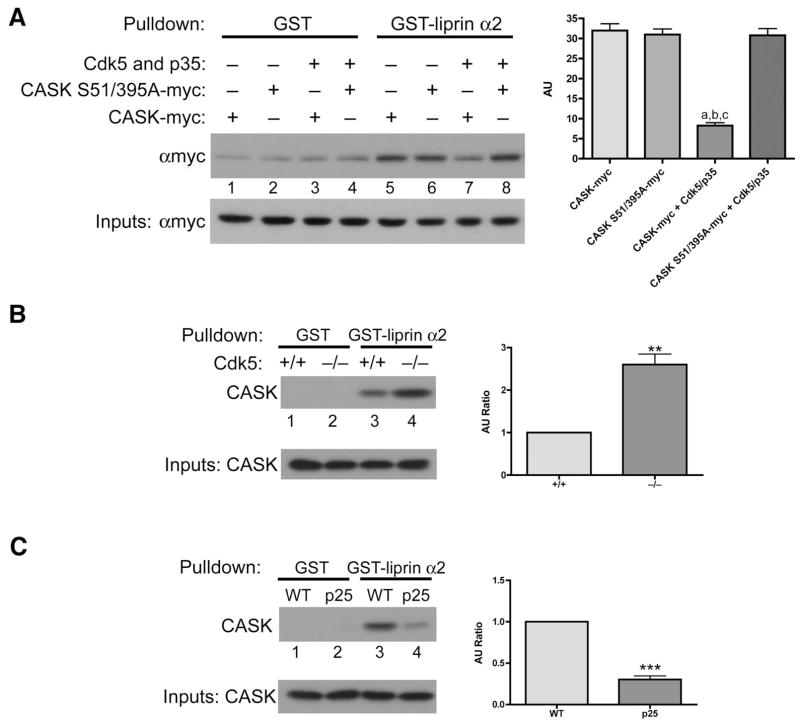

While Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation regulates the subcellular distribution of CASK, and in turn modulates interactions of CASK with presynaptic proteins, we wanted to gain a better understanding of a direct mechanism. Ser 51 and Ser 395 are located in the CaMK and L27 domains of CASK, respectively. Interestingly, the interaction between CASK and liprin-α proteins is dependent on both domains being intact (Olsen et al., 2005). As liprin-α proteins organize the presynaptic active zone, we tested if Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation of CASK regulated this interaction. Using a GST fusion protein of the liprin-α2 SAM domain, we pulled down overexpressed CASK from transfected 293 cells (Figure 7A). Interestingly, when wild-type CASK, but not S51/395A CASK, was cotransfected with active Cdk5 we noticed a significantly decreased binding between CASK and liprin-α (Figure 7A, lanes 7–8). Other known interactors of CASK, including Mint1, Veli and SAP97, did not display such an altered binding (Supplemental Figure 8).

Figure 7. Cdk5 directly regulates the interaction between CASK and liprin-α.

(a) 293 cells were transfected with either CASK-myc or CASK S51/395A-myc alone or in combination with active Cdk5. Cell lysates were then subjected to GST pulldowns using a GST-liprin-α SAM domain fusion protein or GST control. Quantification of the pulldowns were carried out by densitometry with relative values being determined by subtraction of the background pulldown by GST (lanes 1–4) for each condition (lanes 5–8). One-Way ANOVA analysis was used. a, b and c indicate that p<0.001 when comparing lane 7 with lanes 5, 6 and 8, respectively and n=3. (b) Total forebrain lysates were made from wild-type or Cdk5-deficient littermates and subjected to GST pulldowns using a GST-liprin-α SAM domain fusion protein or GST control. Quantification was performed by assessing the densitometric signal and taking the ratio of CASK pulled down from Cdk5-deficient brains (in AU) relative to wild-type littermates (in AU). ** indicates p=0.0030 and n=3. (c) Total forebrain lysates were made from wild-type or CK-p25 littermates and subjected to GST pulldowns using a GST-liprin-α SAM domain fusion protein or GST control. *** indicates p<0.0001 and n=3.

We next performed pulldowns from Cdk5-deficient brain lysate. Compared to wild-type, GST-liprin-α pulled down more CASK from Cdk5-deficient brains (Figure 7B), suggesting that Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation of CASK disrupts the association with liprin-α proteins. We next assessed this interaction using lysates from Cdk5 gain-of-function mouse brains. In comparison to wild-type lysate, GST-liprin-α pulled down less CASK from CK-p25 brains (Figure 7C). Taken together, these results suggest that Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation is capable of directly regulating the interaction between CASK and liprin-α proteins, and suggests a potential molecular mechanism of how Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation may regulate CASK subcellular distribution and subsequent interaction with other components of the presynaptic machinery.

Discussion

CASK represents a novel substrate of Cdk5 that provides a potential mechanism to explain how Cdk5 can drive formation of new synapses. The amount of CASK localized to synaptic membranes is dependent on Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation. Furthermore, Cdk5-dependent CASK localization to membranes mediates the interaction between CASK and components of the presynaptic terminal such as neurexins, Mint1, Veli proteins and N-type channels. Functional data suggests CASK is capable of regulating Cav2 calcium channels. Mechanistically, our data suggests that Cdk5 directly dissociates CASK from liprin-α proteins.

A hypothetical model encompassing our data would be that liprin-α is responsible for the localization of CASK to and within presynaptic terminals, whereby Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation could dissociate and free CASK to bind other necessary presynaptic partners (Figure 8). This idea would fit our fractionation data, including the synaptosome preps where CASK distribution was altered in synaptosomes, and in fractions that precede the crude synaptosomes (Figure 3D). Consistent with this idea, proper dendritic targeting of LAR requires a phosphorylation-dependent dissociation from liprin-α1 (Hoogenraad et al., 2007). Importantly, liprin-α, itself a protein that is present presynaptically and interacts with membrane proteins (Olsen et al., 2005; Serra-Pages et al., 1998), would not serve to sequester CASK as a soluble protein in this model, but rather would be a limiting factor in the distribution of CASK to membranes. If CASK could not dissociate from liprin-α, then only a small pool of CASK would be correctly distributed. Consistent with this idea, overexpression of S51/395A-CASK has dominant-negative effects as assayed by calcium influx, a phenotype that is similar to CASK loss-of-function mediated by RNAi.

Figure 8. Model of Cdk5-phosphorylated CASK at the presynaptic terminal.

Non-phosphorylated CASK is trafficked to and within the presynaptic terminal by liprin-α proteins, where Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation then dissociates CASK from the complex. CASK is then available to interact with the presynaptic machinery, such as Neurexins, SynCAM, Mint1, Veli and voltage-gated calcium channels.

Cdk5 and synaptogenesis

Hints that Cdk5 promotes the synaptogenesis program came from the gain-of-function p25 transgenic mice, where acute expression of p25 resulted in dramatic increases in synapse number as assayed by electron microscopy (Fischer et al., 2005). Increased phosphorylation of CASK may represent one mechanism of how Cdk5 gain-of-function can promote the formation of new synapses. Consistent with this idea, in p25 mice, CASK phosphorylation was increased, CASK was more enriched at membranes and CASK exhibited an increased association with voltage-gated calcium channels. It is important to also point out that while CASK phosphorylation was markedly decreased in every Cdk5 deficiency paradigm we tested, there remained some residual phospho-CASK. This hints that other kinases may also participate in synapse formation/maturation via phosphorylation of CASK. With regard to the role of Cdk5 in synaptogenesis, it is also important to note that phosphorylation of CASK may only be part of the story. p25 trangenic mice exhibit a marked increase in dendritic spine density suggesting that Cdk5 also promotes formation or stabilization of spines (Fischer et al., 2005). It will be essential to also detail the postsynaptic mechanisms by which Cdk5 regulates the synaptogenesis program.

CASK and building of synapses

To a certain extent, CASK is a strong candidate to help a developing presynaptic terminal mature. Neuroligins and SynCAM, two proteins that can drive functional presynaptic terminal formation in vitro (Biederer et al., 2002; Scheiffele et al., 2000), induce CASK recruitment to the developing synapse with the same temporal resolution as their binding partners (Lee, 2005). Once recruited to the materializing synapse, CASK interacts with Cav2 voltage-gated calcium channels (Khanna et al., 2006; Maximov and Bezprozvanny, 2002; Maximov et al., 1999; Spafford et al., 2003; Zamponi, 2003), and colocalizes with N-type channels in the presynaptic terminal, though not necessarily the transmitter release face (Khanna et al., 2006). Our calcium imaging data suggests that overexpression of a dominant-negative CASK alanine mutant or usage of CASK RNAi decreases calcium influx in neurons. Likewise, our recordings suggest that CASK amplifies N-type channel currents by altering channel open probability. Secondly, CASK is involved in an evolutionarily conserved tripartite complex, containing Mint1 and Veli/MALS, that is linked to machinery involved in synaptic vesicle exocytosis (Butz et al., 1998). Mint1 binds the essential exocytosis protein Munc18-1 (Okamoto and Sudhof, 1997), and Mint1 deficient mice have impaired GABAergic transmission (Ho et al., 2003). Veli/MALS deficient mice have decreased CASK levels and reduced EPSCs in autaptic cultures (Olsen et al., 2005; Olsen et al., 2006). Thirdly, CASK interacts with some presynaptic machinery that regulates synaptic vesicle exocytosis, independently of the tripartite complex. For example, CASK interacts with Rab3A (Zhang et al., 2001), a protein involved in a late step of exocytosis (Geppert et al., 1997). Finally, RNAi-mediated knockdown of CASK abolishes synaptic transmission in Lymnaea stagnalis (Spafford et al., 2003). Taken together, the defined protein-protein interactions of CASK can provide a compelling model for how organization of the presynaptic terminal may be orchestrated by synaptic adhesion molecules during synaptogenesis.

CASK may also contribute to synaptogenesis postsynaptically. By immunogold EM, the highest density of CASK occurs at synaptic membranes, where it is roughly evenly distributed between the pre- and postsynapse (Hsueh et al., 1998). Accordingly, CASK is in a complex containing NMDA receptor subunits (Setou et al., 2000), can interact with the glutamate receptor interacting protein, GRIP1 (Hong and Hsueh, 2006), and the CASK binding partners SynCAM and Syndecan-2 are also present in postsynaptic densities (Biederer et al., 2002; Hsueh et al., 1998). The C2 (CASK binding) region of Syndecan-2 is required for dendritic spine maturation (Lin et al., 2007). CASK may also regulate synaptogenesis by acting as a transcriptional coactivator in a complex with the transcription factor Tbr1 and the nucleosome assembly protein CINAP, where target genes include NR2B subunits of NMDA receptors (Hsueh, 2006; Hsueh et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2004a; Wang et al., 2004b). While we cannot rule out a role for Cdk5-phosphorylated CASK postsynaptically, our calcium imaging studies hint that the NMDA receptor is not responsible for the effects caused by S51/395A-CASK (Figure 6 and Supplemental Figure 6).

Recent work has also characterized the phenotype of CASK deficient mice (Atasoy et al., 2007). Deletion of CASK is lethal, causes an increased susceptibility of neurons to apoptosis, and alters levels of Mint1, Veli, β-neurexins and Neuroligins. Most intriguing, however, is that CASK deletion impairs synaptic function. There is an alteration in the ratio of spontaneous “mini” event frequency, with a decrease in the inhibitory minifrequency and an increase in the excitatory minifrequency (Atasoy et al., 2007). This result indicates that there may be an altered balance of inhibitory and excitatory synapses in CASK deficient mice. Downregulation of neuroligin expression by RNAi results in a reduction predominantly in inhibitory synapses (Chih et al., 2005), and there is also a milder reduction in this ratio in Neuroligin triple knockout mice (Varoqueaux et al., 2006). One exciting hypothesis is that β-neurexins, Neuroligins, and intracellular binding partners (such as CASK and PSD-95) may play an important role in governing the balance of inhibitory and excitatory synapses in vivo (Levinson and El-Husseini, 2005). Further study of this idea is important, but may be difficult in the knockout paradigm due to the fact that, at least at excitatory synapses, MAGUK proteins are especially susceptible to compensation (Elias et al., 2006).

Potential link with Autism

Our findings may also have implications for studying autism. Mutations in the genes encoding Neuroligin-3 and -4 are associated with autism (Jamain et al., 2003), and copy number variance analyses linked the Neurexin-1 gene (Szatmari et al., 2007). Also, exciting new work shows that mice harboring a point mutant in Neuroligin-3 have decreased social interaction, and interestingly, altered inhibitory synaptic transmission (Tabuchi et al., 2007). Previous work, combined with our findings here, suggest that Cdk5 and CASK are intracellular mediators of Neurexin/Neuroligin-mediated synaptogenesis. Importantly, mutations and polymorphisms in the Cdk5 activator p35 (Venturin et al., 2006), as well as deletions in CASK (Froyen et al., 2007), have been found in mental retardation patients. Therefore, accumulating evidence strongly suggests that alterations in the synaptogenesis program can lead to serious diseases.

CASK interaction with liprin-α proteins and synaptogenesis

Homologs of liprin-α proteins are essential for presynaptic terminal formation in C.elegans and Drosophila. Mutations in C.elegans syd-2 result in a diffuse localization of several presynaptic proteins and abnormally sized active zones, and loss- and gain-of-function experiments demonstrate that presynaptic organization is dependent on syd-2 (Dai et al., 2006; Patel et al., 2006; Zhen and Jin, 1999). Likewise, Dliprin-α is required for normal synaptic morphology including the size and shape of the presynaptic active zone in Drosophila (Kaufmann et al., 2002). Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation of CASK occurs in both the CaMK and L27 domains, and only mutation of both sites yields a localization phenotype. Since liprin-α proteins require the presence of both domains to interact with CASK (Olsen et al., 2005), the phosphorylation sites are in a prime spot to mediate the interaction. According to our model, liprin-α is required for initial CASK localization to presynaptic terminals. Since, liprin-α binds directly to the kinesin motor KIF1A (Shin et al., 2003), and in Drosophila liprin-α mutant axons there is decreased anterograde processivity resulting in reduced levels of presynaptic markers at terminals (Miller et al., 2005), it is feasible that liprin-α acts as a cargo receptor that delivers CASK, as well as other components, to and within the developing synapse. Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation could then act to coordinate distinct pools of CASK that are bound to liprin-α or are bound to other components of the presynaptic machinery. Importantly, we do not believe that Cdk5 loss-of-function generally affects liprin-α mediated transport since synaptophysin, a marker of synaptic vesicles, is still properly localized within synaptosomes (Figure 3D–E). In our model, there would be advantages of having locally enhanced Cdk5 activity within the presynaptic terminal relative to some other cellular compartments. Supporting this idea, phospho-CASK is particularly enriched at synaptic membranes, and Cdk5 has been shown to phosphorylate and regulate several proteins, including Munc-18, Dynamin-1, Amphiphysin-1 and Synaptojanin-1, that function to control multiple rounds of the synaptic vesicle cycle (Fletcher et al., 1999; Floyd et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2004; Tan et al., 2003; Tomizawa et al., 2003). Synapsin-1 is also a Cdk5 substrate (Matsubara et al., 1996). With regard to the role of liprin-α, it will ultimately be essential to assay synapse formation and CASK localization in mammalian liprin-α loss-of-function models.

Materials and Methods

In vitro Kinase Assay

Kinase Assays were performed as described (Xie et al., 2003). Briefly, 5–10 μg of CASK fragments fused with GST, GST alone, or Ndel1 (Nudel) were incubated with p25/Cdk5 purified from bacculovirus (a gift from A. Musacchio) in kinase buffer (30 mM HEPES pH 7.2, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM MnCl2, 100 μM ATP, 5 μCi [32P]γATP, 1 mM DTT) for 30 min. at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 2X sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, Coomassie stained and then dried prior to analysis by autoradiography.

Antibodies

To generate the phospho-S51 and phospho-S395 antibodies, rabbit antiserum was raised against the respective peptides INTKSpSPQIRNC and AKFTSpSPGLSTC at Covance Research Products (Denver, PA). The antiserum was affinity purified through phospho-peptide columns using a SulfoLink kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The following antibodies were also used: HA (Y-11), p35 (C-19), Mint1/X11α (H-265), Veli1 (C-15), Cdk5 (C-8), CASK (C-19), and GST (Z-5) from Santa Cruz; anti-Neurexin-1 from Abnova; anti-Mint1 from BD Transduction; anti-α1B from Chemicon; anti-α1B from Exalpha; anti-Bassoon from Synaptic Systems; anti-Synaptophysin from Sigma and anti-GFP from Molecular Probes. 9E10 mouse monoclonal against the myc epitope was produced in the Tsai lab. Cdk5 (DC17) and p35 polyclonal have been described (Tsai et al., 1994). For CASK, described polyclonal (Hsueh et al., 1998) and monoclonal (Hsueh and Sheng, 1999) antibodies were used.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the tests detailed in figure legends using Prism 4 for Macintosh (GraphPad Software). For experiments with two comparisons, Student t-test was performed. For multiple comparisons, One-Way ANOVA with the Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test was used.

In vitro synapse formation assays

Performed similarly to as described (Scheiffele et al., 2000). Briefly, pontine explants from E17 brains were plated in Lab-Tek Permanox culture chambers pre-coated with 10 μg/ml polyornithine (Sigma) and 30 μg/ml laminin (Boehringer Mannheim) in neuronal culture medium (Neurobasal, B27, L-glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin and 5 ng/ml BDNF). Separately, 293 cells were transfected with SynCAM, Neuroligin and/or GFP using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). The 293 cells were suspended in neuronal culture medium and seeded at 74,000 cells/cm2 into the chambers with the explants after 2–3 days of culture. After 2–3 days of coculture, 4% paraformaldehyde was used for fixation. In the primary neuron coculture assay, cortical neurons were plated at 175,000 cells/well, and on DIV5 transfected 293 cells were seeded into the culture at 50,000–80,000 cells/well. 24–36 hrs later the cocultures were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Azad Bonni, Yasunori Hayashi, Minh Dang Nguyen, Jisong Guan and Andre Fischer for critical input, Ying Zhou and Zhigang Xie for creating floxed Cdk5 mice and Jie Shen for Cre mice. BAS is a fellow and LHT an investigator of HHMI. This project was supported by a NINDS RO1 Grant to LHT and a NIMH R01 Grant to DTY.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agler HL, Evans J, Tay LH, Anderson MJ, Colecraft HM, Yue DT. G protein-gated inhibitory module of N-type (ca(v)2.2) ca2+ channels. Neuron. 2005;46:891–904. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atasoy D, Schoch S, Ho A, Nadasy KA, Liu X, Zhang W, Mukherjee K, Nosyreva ED, Fernandez-Chacon R, Missler M, et al. Deletion of CASK in mice is lethal and impairs synaptic function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2525–2530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611003104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay JW, Aldea M, Craig TJ, Morgan A, Burgoyne RD. Regulation of the fusion pore conductance during exocytosis by cyclin-dependent kinase 5. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41495–41503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406670200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederer T, Sara Y, Mozhayeva M, Atasoy D, Liu X, Kavalali ET, Sudhof TC. SynCAM, a synaptic adhesion molecule that drives synapse assembly. Science. 2002;297:1525–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.1072356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederer T, Scheiffele P. Mixed-culture assays for analyzing neuronal synapse formation. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:670–676. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butz S, Okamoto M, Sudhof TC. A tripartite protein complex with the potential to couple synaptic vesicle exocytosis to cell adhesion in brain. Cell. 1998;94:773–782. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81736-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chih B, Engelman H, Scheiffele P. Control of excitatory and inhibitory synapse formation by neuroligins. Science. 2005;307:1324–1328. doi: 10.1126/science.1107470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz JC, Tseng HC, Goldman JA, Shih H, Tsai LH. Aberrant Cdk5 activation by p25 triggers pathological events leading to neurodegeneration and neurofibrillary tangles. Neuron. 2003;40:471–483. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00627-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Taru H, Deken SL, Grill B, Ackley B, Nonet ML, Jin Y. SYD-2 Liprin-alpha organizes presynaptic active zone formation through ELKS. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1479–1487. doi: 10.1038/nn1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean C, Scholl FG, Choih J, DeMaria S, Berger J, Isacoff E, Scheiffele P. Neurexin mediates the assembly of presynaptic terminals. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:708–716. doi: 10.1038/nn1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias GM, Funke L, Stein V, Grant SG, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. Synapse-specific and developmentally regulated targeting of AMPA receptors by a family of MAGUK scaffolding proteins. Neuron. 2006;52:307–320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A, Sananbenesi F, Pang PT, Lu B, Tsai LH. Opposing roles of transient and prolonged expression of p25 in synaptic plasticity and hippocampus-dependent memory. Neuron. 2005;48:825–838. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher AI, Shuang R, Giovannucci DR, Zhang L, Bittner MA, Stuenkel EL. Regulation of exocytosis by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 via phosphorylation of Munc18. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4027–4035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd SR, Porro EB, Slepnev VI, Ochoa GC, Tsai LH, De Camilli P. Amphiphysin 1 binds the cyclin-dependent kinase (cdk) 5 regulatory subunit p35 and is phosphorylated by cdk5 and cdc2. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8104–8110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008932200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froyen G, Van Esch H, Bauters M, Hollanders K, Frints SG, Vermeesch JR, Devriendt K, Fryns JP, Marynen P. Detection of genomic copy number changes in patients with idiopathic mental retardation by high-resolution X-array-CGH: important role for increased gene dosage of XLMR genes. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:1034–1042. doi: 10.1002/humu.20564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geppert M, Goda Y, Stevens CF, Sudhof TC. The small GTP-binding protein Rab3A regulates a late step in synaptic vesicle fusion. Nature. 1997;387:810–814. doi: 10.1038/42954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf ER, Zhang X, Jin SX, Linhoff MW, Craig AM. Neurexins induce differentiation of GABA and glutamate postsynaptic specializations via neuroligins. Cell. 2004;119:1013–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata Y, Butz S, Sudhof TC. CASK: a novel dlg/PSD95 homolog with an N-terminal calmodulin-dependent protein kinase domain identified by interaction with neurexins. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2488–2494. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02488.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho A, Morishita W, Hammer RE, Malenka RC, Sudhof TC. A role for Mints in transmitter release: Mint 1 knockout mice exhibit impaired GABAergic synaptic transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1409–1414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252774899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong CJ, Hsueh YP. CASK associates with glutamate receptor interacting protein and signaling molecules. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:771–776. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenraad CC, Feliu-Mojer MI, Spangler SA, Milstein AD, Dunah AW, Hung AY, Sheng M. Liprinalpha1 degradation by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates LAR receptor tyrosine phosphatase distribution and dendrite development. Dev Cell. 2007;12:587–602. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh YP. The role of the MAGUK protein CASK in neural development and synaptic function. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:1915–1927. doi: 10.2174/092986706777585040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh YP, Sheng M. Regulated expression and subcellular localization of syndecan heparan sulfate proteoglycans and the syndecan-binding protein CASK/LIN-2 during rat brain development. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7415–7425. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07415.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh YP, Wang TF, Yang FC, Sheng M. Nuclear translocation and transcription regulation by the membrane-associated guanylate kinase CASK/LIN-2. Nature. 2000;404:298–302. doi: 10.1038/35005118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh YP, Yang FC, Kharazia V, Naisbitt S, Cohen AR, Weinberg RJ, Sheng M. Direct interaction of CASK/LIN-2 and syndecan heparan sulfate proteoglycan and their overlapping distribution in neuronal synapses. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:139–151. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichtchenko K, Hata Y, Nguyen T, Ullrich B, Missler M, Moomaw C, Sudhof TC. Neuroligin 1: a splice site-specific ligand for beta-neurexins. Cell. 1995;81:435–443. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90396-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamain S, Quach H, Betancur C, Rastam M, Colineaux C, Gillberg IC, Soderstrom H, Giros B, Leboyer M, Gillberg C, Bourgeron T. Mutations of the X-linked genes encoding neuroligins NLGN3 and NLGN4 are associated with autism. Nat Genet. 2003;34:27–29. doi: 10.1038/ng1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaech SM, Whitfield CW, Kim SK. The LIN-2/LIN-7/LIN-10 complex mediates basolateral membrane localization of the C. elegans EGF receptor LET-23 in vulval epithelial cells. Cell. 1998;94:761–771. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81735-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann N, DeProto J, Ranjan R, Wan H, Van Vactor D. Drosophila liprin-alpha and the receptor phosphatase Dlar control synapse morphogenesis. Neuron. 2002;34:27–38. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00643-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna R, Sun L, Li Q, Guo L, Stanley EF. Long splice variant N type calcium channels are clustered at presynaptic transmitter release sites without modular adaptor proteins. Neuroscience. 2006;138:1115–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Eickhorst A, Dean C, DeMaria S, Scheiffele P, Isacoff EY. Society for Neuroscience. Washington, D.C.: 2005. Temporal sequence of presynaptic terminal assembly downstream of b-neurexin. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Wenk MR, Kim Y, Nairn AC, De Camilli P. Regulation of synaptojanin 1 by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 at synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:546–551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307813100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson JN, El-Husseini A. Building excitatory and inhibitory synapses: balancing neuroligin partnerships. Neuron. 2005;48:171–174. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, McDonough SI, Lipscombe D. Alternative splicing in the voltage-sensing region of N-Type CaV2.2 channels modulates channel kinetics. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:2820–2830. doi: 10.1152/jn.00048.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YL, Lei YT, Hong CJ, Hsueh YP. Syndecan-2 induces filopodia and dendritic spine formation via the neurofibromin-PKA-Ena/VASP pathway. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:829–841. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara M, Kusubata M, Ishiguro K, Uchida T, Titani K, Taniguchi H. Site-specific phosphorylation of synapsin I by mitogen-activated protein kinase and Cdk5 and its effects on physiological functions. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21108–21113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximov A, Bezprozvanny I. Synaptic targeting of N-type calcium channels in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6939–6952. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-06939.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximov A, Sudhof TC, Bezprozvanny I. Association of neuronal calcium channels with modular adaptor proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24453–24456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, DeProto J, Kaufmann N, Patel BN, Duckworth A, Van Vactor D. Direct observation demonstrates that Liprin-alpha is required for trafficking of synaptic vesicles. Curr Biol. 2005;15:684–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T, Sudhof TC. Binding properties of neuroligin 1 and neurexin 1beta reveal function as heterophilic cell adhesion molecules. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26032–26039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.26032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M, Sudhof TC. Mints, Munc18-interacting proteins in synaptic vesicle exocytosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31459–31464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen O, Moore KA, Fukata M, Kazuta T, Trinidad JC, Kauer FW, Streuli M, Misawa H, Burlingame AL, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. Neurotransmitter release regulated by a MALS-liprin-alpha presynaptic complex. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:1127–1134. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen O, Moore KA, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. Synaptic transmission regulated by a presynaptic MALS/Liprin-alpha protein complex. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MR, Lehrman EK, Poon VY, Crump JG, Zhen M, Bargmann CI, Shen K. Hierarchical assembly of presynaptic components in defined C. elegans synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1488–1498. doi: 10.1038/nn1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales CR, Osborne KD, Zuccarino GV, Scheiffele P, Silverman MA. A cytoplasmic motif targets neuroligin-1 exclusively to dendrites of cultured hippocampal neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:2381–2386. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sara Y, Biederer T, Atasoy D, Chubykin A, Mozhayeva MG, Sudhof TC, Kavalali ET. Selective capability of SynCAM and neuroligin for functional synapse assembly. J Neurosci. 2005;25:260–270. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3165-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiffele P, Fan J, Choih J, Fetter R, Serafini T. Neuroligin expressed in nonneuronal cells triggers presynaptic development in contacting axons. Cell. 2000;101:657–669. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80877-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra-Pages C, Medley QG, Tang M, Hart A, Streuli M. Liprins, a family of LAR transmembrane protein-tyrosine phosphatase-interacting proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15611–15620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setou M, Nakagawa T, Seog DH, Hirokawa N. Kinesin superfamily motor protein KIF17 and mLin-10 in NMDA receptor-containing vesicle transport. Science. 2000;288:1796–1802. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H, Wyszynski M, Huh KH, Valtschanoff JG, Lee JR, Ko J, Streuli M, Weinberg RJ, Sheng M, Kim E. Association of the kinesin motor KIF1A with the multimodular protein liprin-alpha. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11393–11401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211874200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuang R, Zhang L, Fletcher A, Groblewski GE, Pevsner J, Stuenkel EL. Regulation of Munc-18/syntaxin 1A interaction by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 in nerve endings. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4957–4966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.4957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simske JS, Kaech SM, Harp SA, Kim SK. LET-23 receptor localization by the cell junction protein LIN-7 during C. elegans vulval induction. Cell. 1996;85:195–204. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JY, Ichtchenko K, Sudhof TC, Brose N. Neuroligin 1 is a postsynaptic cell-adhesion molecule of excitatory synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1100–1105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spafford JD, Munno DW, Van Nierop P, Feng ZP, Jarvis SE, Gallin WJ, Smit AB, Zamponi GW, Syed NI. Calcium channel structural determinants of synaptic transmission between identified invertebrate neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4258–4267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211076200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spafford JD, Zamponi GW. Functional interactions between presynaptic calcium channels and the neurotransmitter release machinery. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:308–314. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatmari P, Paterson AD, Zwaigenbaum L, Roberts W, Brian J, Liu XQ, Vincent JB, Skaug JL, Thompson AP, Senman L, et al. Mapping autism risk loci using genetic linkage and chromosomal rearrangements. Nat Genet. 2007;39:319–328. doi: 10.1038/ng1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi K, Blundell J, Etherton MR, Hammer RE, Liu X, Powell CM, Sudhof TC. A Neuroligin-3 Mutation Implicated in Autism Increases Inhibitory Synaptic Transmission in Mice. Science. 2007 doi: 10.1126/science.1146221. Published Online Sept 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan TC, Valova VA, Malladi CS, Graham ME, Berven LA, Jupp OJ, Hansra G, McClure SJ, Sarcevic B, Boadle RA, et al. Cdk5 is essential for synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:701–710. doi: 10.1038/ncb1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomizawa K, Sunada S, Lu YF, Oda Y, Kinuta M, Ohshima T, Saito T, Wei FY, Matsushita M, Li ST, et al. Cophosphorylation of amphiphysin I and dynamin I by Cdk5 regulates clathrin-mediated endocytosis of synaptic vesicles. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:813–824. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200308110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai LH, Delalle I, Caviness VS, Jr, Chae T, Harlow E. p35 is a neural-specific regulatory subunit of cyclin-dependent kinase 5. Nature. 1994;371:419–423. doi: 10.1038/371419a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich B, Ushkaryov YA, Sudhof TC. Cartography of neurexins: more than 1000 isoforms generated by alternative splicing and expressed in distinct subsets of neurons. Neuron. 1995;14:497–507. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushkaryov YA, Petrenko AG, Geppert M, Sudhof TC. Neurexins: synaptic cell surface proteins related to the alpha-latrotoxin receptor and laminin. Science. 1992;257:50–56. doi: 10.1126/science.1621094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varoqueaux F, Aramuni G, Rawson RL, Mohrmann R, Missler M, Gottmann K, Zhang W, Sudhof TC, Brose N. Neuroligins determine synapse maturation and function. Neuron. 2006;51:741–754. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venturin M, Moncini S, Villa V, Russo S, Bonati MT, Larizza L, Riva P. Mutations and novel polymorphisms in coding regions and UTRs of CDK5R1 and OMG genes in patients with non-syndromic mental retardation. Neurogenetics. 2006;7:59–66. doi: 10.1007/s10048-005-0026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GS, Hong CJ, Yen TY, Huang HY, Ou Y, Huang TN, Jung WG, Kuo TY, Sheng M, Wang TF, Hsueh YP. Transcriptional modification by a CASK-interacting nucleosome assembly protein. Neuron. 2004a;42:113–128. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TF, Ding CN, Wang GS, Luo SC, Lin YL, Ruan Y, Hevner R, Rubenstein JL, Hsueh YP. Identification of Tbr-1/CASK complex target genes in neurons. J Neurochem. 2004b;91:1483–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Sanada K, Samuels BA, Shih H, Tsai LH. Serine 732 phosphorylation of FAK by Cdk5 is important for microtubule organization, nuclear movement, and neuronal migration. Cell. 2003;114:469–482. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00605-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Saura CA, Choi SY, Sun LD, Yang X, Handler M, Kawarabayashi T, Younkin L, Fedeles B, Wilson MA, et al. APP processing and synaptic plasticity in presenilin-1 conditional knockout mice. Neuron. 2001;31:713–726. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00417-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamponi GW. Regulation of presynaptic calcium channels by synaptic proteins. J Pharmacol Sci. 2003;92:79–83. doi: 10.1254/jphs.92.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Luan Z, Liu A, Hu G. The scaffolding protein CASK mediates the interaction between rabphilin3a and beta-neurexins. FEBS Lett. 2001;497:99–102. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen M, Jin Y. The liprin protein SYD-2 regulates the differentiation of presynaptic termini in C. elegans. Nature. 1999;401:371–375. doi: 10.1038/43886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.