Abstract

The intracellular distribution of glutaminyl–tRNA synthetases and their role in mitochondrial tRNA import were evaluated in the ancient eukaryote Leishmania tarentolae. The following results were obtained: (i) Glutaminyl–tRNA synthetase was detected in leishmanial mitochondria. This was unexpected because it has been postulated that, in organelles, Gln-tRNAGln is not formed by direct acylation of tRNAGln but by enzymatic transamidation of misacylated Glu-tRNAGln. (ii) Whereas the cytosolic extract is able to charge cytosolic and mitochondrial tRNAsGln, the mitochondrial matrix extract does not aminoacylate the cytosol-specific tRNAGln. This indicates that mitochondrial and cytosolic glutaminyl–tRNA synthetases are distinct. (iii) Seven of the 11 nucleotides that differ between the cytosolic and the mitochondrial tRNAGln are sufficient to convert the cytosol-specific tRNAGln into an optimal substrate for the mitochondrial enzyme. These nucleotides are arranged in three groups consisting of the nucleotides flanking the anticodon stem, the 5′ nucleotide of the anticodon, and four nucleotides within the acceptor stem. And (iv), it was shown that the identity elements for recognition by the mitochondrial glutaminyl–tRNA synthetase do not overlap with a previously identified sequence segment required for mitochondrial import of the tRNAGln.

Keywords: aminoacyl–tRNA synthetases, trypanosomatid, mitochondrial RNA import, evolution

Generally, 20 functionally different aminoacyl–tRNA synthetases (aaRS), one for each amino acid, are required for protein synthesis. However, there are exceptions; in certain organisms some, tRNAs are formed by transformation of acylated tRNAs rather than by direct acylation. One example is the formation of Gln-tRNAGln because it can be achieved by two different pathways. tRNAGln can either be charged directly with glutamine by glutaminyl–tRNA synthetase (GlnRS), or formation of Gln-tRNAGln is achieved by a two-step enzymatic reaction (1). In this case, the tRNAGln is first mischarged with glutamate by glutamyl–tRNA synthetase (GluRS), resulting in Glu-tRNAGln. The glutamate attached to the tRNAGln is then converted by a specific amidotransferase into a glutamine, yielding a correctly charged tRNAGln. Absence of GlnRS and usage of the transamidation pathway to form Gln-tRNAGln has been demonstrated in a large number of organisms, including Archea (2), Gram-positive bacteria (3, 4), and organelles of eukaryotes (5). In agreement with this, GlnRS was lacking in Rhizobium meliloti (6), a member of the α-subdivision of purple bacteria and, according to the endosymbiont theory, the ancestors of present day mitochondria.

L. tarentolae belongs to the earliest diverging cells in eukaryotic evolution that have mitochondria (7). This is illustrated by a number of unique features of their mitochondria, including a bipartite, topologically interlocked genome, guide RNA-mediated RNA editing, and the lack of mitochondrial tRNA genes (8, 9). Mitochondrial biogenesis in trypanosomatids therefore not only involves import of proteins, as in all other eukaryotes, but also import of the whole set of nuclearly encoded mitochondrial tRNAs (10–13). However, mitochondrial tRNA import is not restricted to protozoa but has also been shown in plants and yeast (14, 15). aaRS have been implicated in the import process. Whereas there is only indirect evidence for their involvement in plants (16), participation of a precursor of a mitochondrial aaRS in tRNA import has been shown directly in yeast (17). In L. tarentolae, in most cases, one gene codes for both mitochondrial and cytosolic tRNA isotypes, resulting in almost identical sets of tRNAs in the two compartments (10). This raises the questions whether, in L. tarentolae, the aaRS as well are identical in the cytosol and the mitochondrial fraction and whether these enzymes play a role in tRNA import.

To address these questions, we focused on the tRNAsGln. Two highly homologous tRNAsGln have been characterized in L. tarentolae: the tRNAGln with the anticodon UUG, which, like most other leishmanial tRNAs is found in the cytosol as well as in mitochondria (18), and the tRNAGln with the anticodon CUG, which is the only known cytosol-specific tRNA in that organism (19). The intracellular distribution and the substrate specificities of GlnRSs were determined. Unexpectedly, GlnRS activity was found in mitochondrial matrix fractions of L. tarentolae, showing that GlnRS is not universally absent from mitochondria. In addition, it was shown that the mitochondrial GlnRS of L. tarentolae is distinct from its cytosolic counterpart. Furthermore, it could be demonstrated that the sequence elements within mitochondrial tRNAGln that are identity determinants for the mitochondrial GlnRS are distinct from a previously identified import signal in the D loop (20).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

L. tarentolae (UC strain) was grown at 27°C in Difco brain heart infusion medium containing 10 mg/ml hemin to late log phase (0.5 × 108–1.5 × 108 cells/ml) and used immediately. Cells were washed once in cold 20 mM sodium-phosphate buffer (pH 7.9) containing 150 mM NaCl and 20 mM glucose.

Isolation of tRNA.

Washed L. tarentolae (3 × 1011 cells) were resuspended in 10 ml of 20 mM Tris⋅HCl/20 mM magnesium acetate, pH 7.4. Cells were extracted twice with an equal volume of phenol and equilibrated in 25 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.5) containing 50 mM NaCl. Sodium acetate (pH 5.2) was added to 0.3 M and total RNAs were precipitated by the addition of an equal volume of isopropanol. The RNA pellet was resuspended in 4 ml of 0.2 M Tris⋅acetate (pH 9.0) and deacylated for 30 min at 37°C. After addition of sodium acetate to 0.3 M, the RNAs were precipitated by the addition of 2 vol of ethanol. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 2 ml of 10 mM 1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino]propane⋅HCl (pH 7.0), 1 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM 1,4-dithiothreitol and treated with 10 units of RQ1 DNase (Promega) for 20 min at 37°C. Subsequently, the mixture was phenol-extracted and precipitated with ethanol as before. The pellet was dissolved in 3 ml of 1 M NaCl and centrifuged for 10 min at 16,000 × g to remove high molecular weight RNAs. The supernatant containing the tRNAs was ethanol precipitated, resuspended in 1 ml of H2O, and loaded on a 0.6 ml DEAE-cellulose column equilibrated in buffer A (10 mM sodium acetate/0.2 M NaCl/10 mM MgCl2, pH 5). The column was washed with 4 ml of buffer A and eluted by 2 ml of buffer A containing 0.7 M NaCl. The tRNAs (yield 2–3 mg) were precipitated, resuspended in H2O, and frozen at −70°C until further use.

In Vitro Transcription of tRNA.

The tRNAGln variants were produced by in vitro transcription using T7 polymerase (21). DNA-fragments containing the T7 promoter and the corresponding natural or synthetic tRNAGln genes were produced by PCR using the following oligonucleotides: QM1, 5′-GGAATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTCCTATAGTGTAGT-3′; QM2, 5′-TGGTGGTCCTACCAGGAT-3′; QC1, 5′-GGAATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGCTCCTATAGTGTAGCGG-3′; QS1, 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGCTCCTATAGTCTAGTTGGTTAGGACCTCGG ACTCTGAAT C-3′; QCUUG, 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGCTCCTATAGTGTAGCGGTTATCACCTCGGACTTTGA ATCCGAT-3′; QCM1, 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGTCCTATAGTGTAGCGGTT-3′; ACST, 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAG GTCCTATAGTGTAGTGGTTATCACT-3′; QC2, 5′-TGGCACTCCTACCTGGACTC-3′; QCM2, 5′-TGGTGGTCCTACCTGGACTCGAAC-3′; ACST-3′, 5′-TGGTGGTCCTACCTGGACTCGAACCAGGGTTT-3′; GNLT1, 5′-GCGGTACCGATGTTATGGGCTAACCG-3′; GNLT2, 5′-GGAGATCTCCCCAGCCGCTTTTTGG-3′; LTQM1, 5′-CTAGATCACCCACGCTTG-3′; and LTQM2, 5′-GAGTGCCGTACTCCCACT-3′. Sequences corresponding to the T7 promoter are underlined. As DNA templates to produce the variant tRNAsGln, in addition to some of the PCR products listed below, the following PCR products were used: PCR-fragment GlnCyt was produced using the primers GNLT1/GNLT2 and genomic leishmanial DNA as template; PCR-fragment GlnMit was produced using the primers LTQM1/LTQM2 and genomic leishmanial DNA as template. The variant tRNAGln genes containing a 5′-flanking T7 promoter were prepared using the following primer pairs and templates: cytosolic tRNAGln (QC1/QC2, template GlnCyt); cytosolic tRNAGln containing the mitochondrial acceptor stem (QCM1/QCM2, template PCR-product of the previous reaction); cytosolic tRNAGln containing the mitochondrial anticodon (QCUUG/QC2, template GlnCyt); cytosolic tRNAGln containing the mitochondrial acceptor stem and the anticodon (QCM1/QCM2, template PCR product of the previous reaction); cytosolic tRNAGln containing the mitochondrial acceptor stem and anticodon, the nucleotide substitutions flanking the anticodon stem and the D loop substitution (ACST/ACST3′, template GlnMit); cytosolic tRNAGln containing all the previous changes except the D loop substitutions (QCM1/ACST3′, template PCR product of previous reaction); mitochondrial tRNAGln (QM1/QM2, template GlnMit); and tRNAGln(D-Ile) (QS1/QC2, template GlnCyt).

Preparation of RNA-Free Cytosolic Fractions.

Washed L. tarentolae cells were hypotonically lysed at 2.4 × 109 cells/ml in 1 mM Tris⋅HCl/1 mM EDTA, pH 8, by four passages through a 25-G syringe needle. A quarter volume of 5X acylation buffer (250 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5/125 mM KCl/40 mM MgCl2/50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol), one-ninth volume of 100% glycerol was added, and the extract was centrifuged for 25 min at 150,000 × g at 4°C. NaCl was added to 150 mM, and the sample was applied on a DEAE cellulose column (13 mg protein/ml bed volume) equilibrated in the same buffer. The flow through fraction was concentrated using a Centricon-30 concentrator (Amicon) to 1 ml and loaded on a 10 ml Sephadex G-100 column (20 cm length) equilibrated in 1x acylation buffer containing 10% glycerol (22). Protein-containing fractions of the exclusion volume were pooled (yield 2.3 mg/1010 cells), frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −70°C until further use in the charging assays.

Preparation of RNA-Free Mitochondrial Matrix Fractions.

Mitoplasts of L. tarentolae were purified as described (23, 24). Isolated mitoplasts (40 mg protein) were resuspended in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8), 250 mM sucrose, and 2 mM EDTA and frozen in liquid N2. To prepare the mitochondrial matrix fraction, an equal volume of 16 mM MgCl2, 100 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), and 50 mM KCl containing 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride was added to thawed mitoplasts, and the suspension was sonicated on wet ice (10 bursts of 5 s using the microtip of a sonicator (MSE, Zivy, Switzerland), amplitude 3 at medium power setting). The extract was then subjected to another freeze thaw cycle, and the sonication step was repeated. After the addition of glycerol to 10% and 2-mercaptoethanol to 10 mM, the suspension was centrifuged at 180,000 × g at 4°C for 25 min. Approximately 35% of total proteins were recovered in the supernatant corresponding to the mitochondrial matrix fraction. The supernatant was adjusted to 150 mM NaCl and applied to a DEAE cellulose (12 mg matrix protein/0.5 ml bed volume) followed by Sephadex G-100 chromatography as described for the cytosol (see previous paragraph). Approximately 2.5 mg of mitochondrial matrix proteins was recovered in the final fraction.

Yeast mitochondria originating from the wild-type strain D273–10B were purified using Nycodenz gradients (25). Mitochondrial RNAs were isolated as described (26). From 20 mg of mitochondria, 270 μg of RNA was obtained. RNA-free mitochondrial matrix fraction was prepared as described for L. tarentolae. Fifty milligrams of purified mitochondria yielded 4 mg of RNA-free matrix fraction.

Charging Assays.

Aminoacylation reactions for L. tarentolae were performed in 100 μl of 1x acylation buffer supplemented with 4 mM ATP containing 20 μg of total leishmanial tRNA or 1.8 μg of the corresponding in vitro transcribed tRNA, 60 μg of crude cytosolic or mitochondrial aaRS fraction and 19 μM of 14C-glutamine (258 mCi/mmol) or 14C-glutamate (265 mCi/mmol) (Dupont) respectively. For the competition assays an additional 1.8 or 9 μg of the competitor tRNA [cytosolic tRNAGln or tRNAGln(D-Ile)] were added to a standard charging reaction. Charging assays for yeast were done under identical conditions with the exception that 50 μg of total mitochondrial RNA and 100 μg of crude mitochondrial aaRS-containing matrix fraction were used. All samples were incubated for 15 min at 37°C and spotted onto dried Whatman filter paper (2.5 x 2.5 cm) which had been pretreated with 5% TCA containing either 0.1 mM glutamine or glutamate. The filters were washed three times (15 min each) on ice in 4 ml/filter of cold 5% TCA containing 0.1 mM glutamine or glutamate followed by two washes in cold 0.1 M HCl. After a final wash in cold ethanol (96%) the filters were dried and processed for scintillation counting.

Thin Layer Chromatography.

After incubation at 37°C, a standard charging reaction containing total tRNAs, leishmanial mitochondrial matrix extract, and 14C-glutamine was phenol-extracted, ethanol-precipitated, and washed with 75% ethanol. The resulting pellet was deacylated in 50 μl of 10 mM KOH for 10 min at 65°C. Subsequently, the pH was adjusted (pH 6–7) by the addition of 0.1 M HCl and dried under vacuum. Finally, the pellet was resuspended in 3 μl of water and spotted onto a cellulose thin layer chromatography plate. The plate was developed for ≈3 h in a mixture of isopropanol/formic acid/water (77:18.2:4.8) and exposed on x-ray film.

Miscellaneous.

Antiserum directed against yeast Hsp60 was a generous gift of G. Schatz, Biozentrum, Basel. Polyclonal antiserum specific for leishmanial pyruvate kinase was kindly provided by P. Michels, International Institute of Cellular and Molecular Pathology, Brussels. Both sera were used at a dilution of 1/500. The signals were visualized using peroxidase-conjugated second antibody and the enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham). Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA assay (Pierce).

RESULTS

Mitochondrial GlnRS in L. tarentolae.

In vitro charging assays using labeled glutamine or glutamate were performed to measure GlnRS and GluRS activities in the mitochondria and the cytosol of L. tarentolae. Because of the nuclear origin of mitochondrial tRNAs in L. tarentolae, their cytosolic and mitochondrial sets of tRNAs overlap to a great extent (10). Therefore, tRNAs isolated from total cellular extract were used as substrates for both cytosolic and mitochondrial aaRS. Similar specific activities of GlnRS and GluRS were detected in the cytosol (Fig. 1A, left). Unexpectedly, not only GluRS but also GlnRS activity was detected in the corresponding mitochondrial matrix fractions (Fig. 1A, right). In yeast mitochondria assayed under the same conditions, however, only GluRS activity could be measured (Fig. 1B). Cytosolic contamination of the mitochondrial fraction, a possible trivial explanation for our results, can be excluded for the following reasons: (i) Immunoblots using antibodies against the mitochondrial heat shock protein 60 and the cytosolic protein pyruvate kinase demonstrate that very little cytosolic contamination is observed in the mitochondrial fraction (Fig. 1C). (ii) Comparable specific activities of cytosolic and mitochondrial GlnRS are detected. Should GlnRS be a cytosolic contaminant of the mitochondrial fraction, we would expect much lower specific activity. (iii) Comparable specific activities are observed for GlnRS and GluRS (Fig. 1A), indicating that, in L. tarentolae, GlnRS behaves like a bona fide mitochondrial aaRS. In the aminoacylation assays, crude mitochondrial matrix fraction was used so that metabolic conversion of glutamine to glutamate before charging could not be excluded. In this case, mitochondrial GluRS but not GlnRS activity would have been measured in the assay, even though labeled glutamine and not glutamate was added to the reaction. To rule out this possibility, we performed a preparative in vitro charging experiment using radioactive glutamine, total tRNA, and mitochondrial matrix fraction as a source of GlnRS activity. After the reaction, the charged tRNAs were precipitated and deacylated. The labeled amino acid released in this process was analyzed by thin layer chromatography and shown to comigrate with glutamine but not with glutamate (Fig. 1D), demonstrating that bona fide GlnRS activity was measured in the assay.

Figure 1.

Mitochondrial GlnRS in L. tarentolae. (A) Leishmanial total tRNAs were charged with 14C-glutamine (Gln) or 14C-glutamate (Glu) using 60 μg each of RNA-depleted cytosolic (Cyt) or mitochondrial matrix (Mit) fractions of L. tarentolae. Bars indicate mean values (±SD) of independent aminoacylation reactions (n = 4–8) using at least two independently prepared cytosolic or mitochondrial extracts. (B) Yeast mitochondrial tRNA was charged with 14C-glutamine (Gln) or 14C-glutamate (Glu) using 100 μg of RNA-depleted yeast mitochondrial matrix extract. The reactions were incubated in the presence (hatched columns) or as a control in the absence of the corresponding tRNAs (empty columns). The y axis indicates the specific activities corresponding to picomolars of aminoacylated tRNA formed per μg of proteins. (C) Equal amounts (50 μg) of RNA-depleted cytosolic (Cyt) and mitochondrial matrix (Mit) fraction used for the charging experiments were analyzed by immunoblots using antisera specific for mitochondrial heat shock protein 60 (HSP60) or the cytosolic protein pyruvate kinase (PYK). (D) A charging reaction containing total tRNAs, 14C-glutamine, and mitochondrial matrix extract was deacylated, and the released amino acid (Mit) was analyzed by thin layer chromatography. 14C-glutamine (Gln) and 14C-glutamate (Glu) served as markers.

In vitro charging experiments also were performed using the mitochondrial matrix fraction of Trypanosoma brucei. Qualitatively identical results as for L. tarentolae were obtained. Similar levels of activity of GlnRS and GluRS were measured in the mitochondrial matrix of trypanosomes (data not shown); however, the specific activities were significantly lower than in Leishmania. These results demonstrate the existence of GlnRS in the mitochondria of trypanosomatids, indicating that this enzyme is not universally absent in mitochondria.

Cytosolic and Mitochondrial GlnRS Are Distinct.

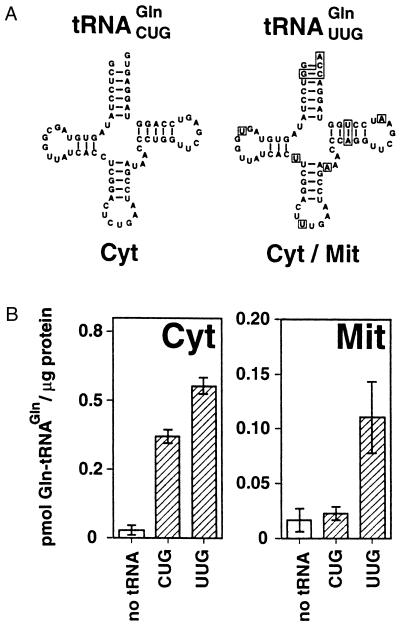

Two tRNAsGln have been characterized in L. tarentolae. They differ in 11 nucleotide positions and in their intracellular localization (Fig. 2A). The tRNAGln(CUG), unlike most other leishmanial tRNAs, is found exclusively in the cytosol (19). The tRNAGln(UUG), however, has a dual location and is found in both the cytosol and the mitochondria (18). We will refer in this study to the tRNAGln(CUG) as the cytosolic and the tRNAGln(UUG) as the imported mitochondrial tRNAGln, even though the latter also is found in the cytosol. In vitro charging assays were performed using in vitro-transcribed cytosolic or mitochondrial tRNAsGln as substrates and cytosolic or mitochondrial extract as source of enzyme. Cytosolic extract aminoacylated both substrates whereas the mitochondrial extract was only able to charge the mitochondrial but not the cytosolic tRNAGln (Fig. 2B). These results prove that the mitochondrial GlnRS activity cannot be caused by cytosolic contamination of the mitochondrial fraction, and, most importantly, they show that cytosolic and mitochondrial GlnRS activities are distinct.

Figure 2.

Cytosolic and mitochondrial GlnRS are distinct. (A) Inferred secondary strucures of cytosol-specific (Cyt) and mitochondrial (Cyt/Mit) tRNAsGln of L. tarentolae. Nucleotides in the mitochondrial tRNAGln that are different from the cytosolic ones are boxed. (B) Cytosol-specific tRNAGln (CUG) and mitochondrial tRNAGln (UUG) of L. tarentolae were charged with 14C-glutamine using 60 μg each of RNA-depleted cytosolic (Cyt) or mitochondrial matrix (Mit) fractions. As a control, the reactions were performed without adding the tRNAs (no tRNA). Bars indicate mean values (±SD) of independent aminoacylation reactions (n = 4–8) using at least two independently prepared cytosolic or mitochondrial extracts. Y axis as Fig. 1.

Identity Elements Recognized by Mitochondrial GlnRS.

Cytosolic and mitochondrial tRNAGln differ by 11 nucleotides that are distributed in six groups all over the molecule (Fig. 2A). To determine which groups of nucleotides, or which combination of groups, are critical for recognition by the mitochondrial GlnRS, the cytosolic tRNAGln sequences were successively replaced by the corresponding mitochondrial tRNAGln sequences (Fig. 3). The resulting hybrid molecules corresponded to the cytosolic tRNAGln containing (i) the mitochondrial acceptor stem, (ii) the mitochondrial anticodon, (iii) the mitochondrial acceptor stem and the anticodon, (iv) the mitochondrial acceptor stem, the anticodon, and the nucleotide substitutions flanking the anticodon stem, and (v) all of the previous changes and the D loop substitution. In vitro transcripts of all of these tRNAGln variants were tested for charging by the mitochondrial extract. Three elements required for recognition of the mitochondrial GlnRS were identified: (1) the nucleotides flanking the anticodon stem that contribute approximately half and (2) the 5′ nucleotide of the anticodon and (3) the acceptor stem each contributing approximately one-fourth to the conversion of the cytosolic tRNAGln into a substrate for the mitochondrial GlnRS. If all three elements are present, the same level of activity was reached as with the natural substrate, the mitochondrial tRNAGln. The nucleotide substitutions in the D loop or the T loop therefore are not identity elements.

Figure 3.

Identity elements recognized by mitochondrial GlnRS. Wild-type cytosolic tRNAGln and cytosolic tRNAGln variants were charged with 14C-glutamine using 60 μg of RNA-depleted mitochondrial matrix (Mit) fractions. The tested tRNAGln variants are indicated along the x axis. Nucleotides in the cytosol-specific tRNAGln that have been changed to the mitochondrial ones are indicated by letters. The level of activity of each tRNAGln variant is expressed relative to the charging levels reached by mitochondrial tRNAGln. Bars indicate mean values (±SD) of independent aminoacylation reactions (n = 3–8) using two independently prepared mitochondrial extracts. The background value of a charging reaction without added tRNA (no tRNA) also is shown.

Import Signal and Identity Elements for Mitochondrial GlnRS Are Distinct.

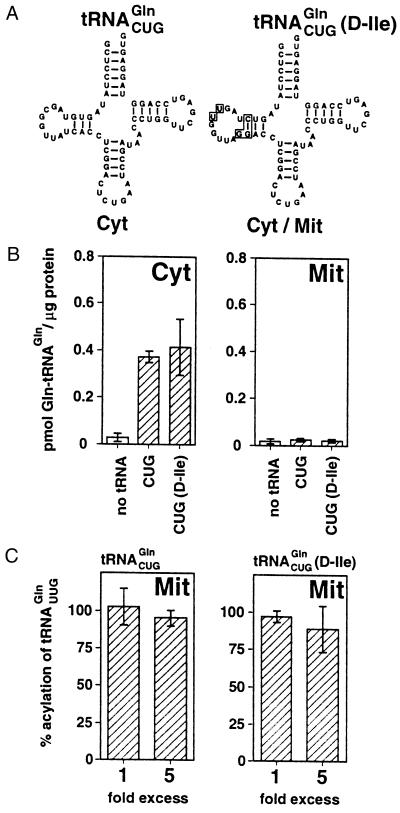

Mitochondrial tRNAGln must not only contain recognition elements for the mitochondrial GlnRS but also elements that specify its import into mitochondria. Recently Lima et al. (20) showed that, in L. tarentolae, the cytosolic tRNAGln is converted into an imported tRNA if its D stem loop is replaced with that of tRNAIle, which is predominantly found in mitochondria. The five point mutations necessary to switch the tRNAGln D stem loop to the tRNAIle D stem loop are indicated in Fig. 4A; the resulting molecule was called tRNAGln(D-Ile). From these results, it was concluded that at least one import signal must lie within the D loop region.

Figure 4.

Import signal and identity elements for mitochondrial GlnRS are distinct. (A) Inferred secondary strucures of cytosol-specific tRNAGln (Cyt) and mutant tRNAGln(D-Ile), which is imported into mitochondria (Cyt/Mit) (20). Nucleotides in the tRNAGln(D-Ile) that are different from the cytosolic ones are boxed. (B) Cytosol-specific tRNAGln (CUG) and mutant imported tRNAGln [CUG(D-Ile)] were charged with 14C-glutamine using 60 μg each of RNA-depleted cytosolic (Cyt) or mitochondrial matrix (Mit) fractions. As a control, the reactions were performed without adding tRNAs (no tRNA). Y axis as Fig. 1. (C) Competition assays were performed by charging of mitochondrial tRNAGln (UUG) with 14C-glutamine using 60 μg of mitochondrial matrix (Mit) in the presence of a 1- or 5-fold excess of cytosolic tRNAGln (CUG) (Left) or the mutant-imported tRNAGln [CUG(D-Ile)] (Right). The level of charging is expressed as percentage of a standard charging reaction without competitor tRNA. Bars indicate mean values (±SD) of independent aminoacylation reactions (n = 3–8) using at least two independently prepared cytosolic or mitochondrial extracts.

All mitochondrial aaRS are imported into mitochondria. It has therefore been suggested that these enzymes may mediate mitochondrial tRNA import (27). Indeed, direct involvement of an aaRS in mitochondrial tRNA import has been shown in yeast (17). In addition, it was shown in plants that a point mutation within the tRNAAla that abolishes charging also prevents its import into mitochondria, providing evidence that aaRS are also involved in tRNA import in plants (16). To assess the role mitochondrial GlnRS might play in tRNA import in L. tarentolae, the tRNAGln(D-Ile) was transcribed in vitro and subjected to charging assays. The tRNAGln(D-Ile) behaved identically to the cytosolic tRNAGln, in that both could be charged by the cytosolic but not by the mitochondrial GlnRS (Fig. 4B). Cytosolic tRNAGln and tRNAGln(D-Ile), however, differ in their intracellular localization; only tRNAGln(D-Ile) is imported into mitochondria, indicating that charging by mitochondrial GlnRS is not required for import of tRNAGln(D-Ile). Nevertheless, the fact that charging and mitochondrial import tRNAGln(D-Ile) are not coupled does not preclude the involvement of mitochondrial GlnRS in import because the imported tRNAGln(D-Ile) may still interact with the enzyme without being charged. Because the mitochondrial GlnRS has not been purified, direct binding of tRNAGln(D-Ile) to GlnRS cannot be assayed. However, should such a binding occur, it is possible to test whether it involves the same domain of GlnRS that is required for aminoacylation. In this case, tRNAGln(D-Ile), which is imported but not charged, is expected to interfere with aminoacylation of mitochondrial tRNAGln by mitochondrial GlnRS. Fig. 4C demonstrates that neither cytosolic tRNAGln, which is not expected to bind to the enzyme and therefore serves as a control, nor tRNAGln(D-Ile) inhibited charging of mitochondrial tRNAGln by GlnRS when added to the reaction in up to a 5-fold excess. It is therefore concluded that no significant binding of tRNAGln to the domain of mitochondrial GlnRS, which is responsible for charging, is required for import. Mitochondrial GlnRS might, however, still be involved in import. In this case, though, one must postulate that it contains two distinct nonoverlapping binding sites for imported tRNAGln, one for charging and one for import.

DISCUSSION

There is overwhelming evidence that mitochondria arose from endosymbiontic capture of a member of the α-subdivision of purple bacteria. It is generally assumed that the endosymbiontic event happened just once in eukaryotic evolution and that therefore all mitochondria are evolutionarily related (28). Recently, it was shown that R. meliloti (6), a member of the α-subdivision of purple bacteria, unlike other Gram-negative bacteria, uses the transamidation pathway for Gln-tRNAGln formation (6). In line with this, it was demonstrated also that mitochondria use the transamidation pathway like their presumed ancestors and therefore are devoid of mitochondrial GlnRS (5). The transamidation pathway is therefore considered to be a more ancestral pathway to form Gln-tRNAGln than direct acylation by GlnRS.

Using in vitro charging assays with radioactive glutamine and RNA-free cytosolic and mitochondrial extracts, we show here that GlnRS is not universally absent from mitochondria but is found in organelles of L. tarentolae and T. brucei. Evidence is presented that shows that, in L. tarentolae, mitochondrial and cytosolic GlnRS are distinct because they exhibit a different substrate specificity. One interpretation of these results is that the cytosolic GlnRS is able to charge both cytosolic and mitochondrial tRNAsGln. The mitochondrial GlnRS, which has a more limited substrate specificity, would in this scenario be localized in mitochondria only. However, it cannot be excluded that cytosolic and mitochondrial GlnRS have nonoverlapping substrate specificities. In this case, one needs to postulate a dual location of the mitochondrial enzyme, in both cytosol and mitochondria.

GlnRS is not found in the α-subdivision of purple bacteria, the presumed ancestors of present day mitochondria (6). Could this mean that trypanosomatid mitochondria are derived from a different endosymbiont than other mitochondria? Indeed, mitochondria of trypanosomatids are unique in other respects as well. Their genome consists of a complex intercalated network of two genetic elements, the maxi- and the minicircles (29). Nowhere else in nature has a comparable structure been found. In addition, many mitochondrial genes in trypanosomatids represent cryptogenes, whose transcripts have to be extensively edited to become functional mRNAs (9). RNA editing was shown to be mediated by short RNAs, called guide RNAs (30), which have not been found in mitochondria of any other organism. These features would argue for a polyphyletic origin of mitochondria. However, a monophyletic origin of mitochondria is favored by the fact that the mitochondrial genes in trypanosomes code for the same set of proteins as most other mitochondria. In this case, mitochondrial GlnRS would have been acquired later in evolution after the endosymbiontic event. This could have been achieved by gene duplication of the cytosolic GlnRS and establishing of a mitochondrial targeting sequence. At present, it is not possible to decide whether mitochondrial GlnRS in trypanosomatids has been acquired early or late in evolution. Cloning and sequencing of mitochondrial GlnRS might help to answer this question.

It is interesting to note that mitochondrial GlnRS may also exist in other protozoa. Already more than 20 years ago, GlnRS activity was measured in Tetrahymena mitochondria (27). This work was done before the discovery of transamidation as the primary pathway to form Gln-tRNAGln in mitochondria, however, and therefore needs to be confirmed. The reason why trypanosomatid and maybe other protozoal mitochondria contain GlnRS and do not use the transamidation pathway is unknown at present. Of interest, both trypanosomatids and Tetrahymena (31, 32) import all or most of their mitochondrial tRNAs, including the tRNAsGln, from the cytosol. However, we were able to show that, in L. tarentolae, there is no direct link between charging by mitochondrial GlnRS and import of tRNAGln. This conclusion is based on the identification of the sequence elements necessary for charging by mitochondrial GlnRS, which can be separated from a previously identified import signal located in the D loop of the tRNA (20). Consequently, a mutated tRNAGln that cannot be charged by mitochondrial GlnRS can still be imported into mitochondria, provided that it contains an import signal in the D loop. This is in contrast with the plant system, in which a single point mutation within the acceptor stem concomitantly inactivated both charging by the cognate aaRS and mitochondrial import (16). In yeast, the situation is different. Mitochondrial import of the single imported tRNALys is mediated by the mitochondrial precursor of lysyl–tRNA synthetase. Surprisingly, this enzyme is only able to bind, but not to aminoacylate, the imported tRNALys (17). The same could potentially be true in L. tarentolae. However, neither an excess of cytosolic tRNAGln nor an excess of import competent tRNAGln(D-Ile) was able to inhibit charging of mitochondrial tRNAGln by mitochondrial extracts, indicating that the binding sites for charging and the putative binding sites for import do not overlap. In addition, it has been shown in T. brucei that intron-containing tRNATyr that could not be charged could still be imported into mitochondria in vivo (33). These results, together with the observation that in vitro import of tRNA into mitochondria of Leishmania donovani does not require cytosolic factors (34, 35), make the involvement of aaRS in mitochondrial tRNA import in trypanosomatids unlikely.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Horn for excellent technical assistance. We also thank R. Kohler, T. von Zelewsky, I. Roditi, and N. Müller for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by Grant 31–46628.96 from the Swiss National Foundation, by a fellowship of the “Prof. Dr. Max Cloëtta”-Foundation (A.S.), and by a grant of the Roche Research Foundation (R.H.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- aaRS

aminoacyl–tRNA synthetase

- GlnRS

glutaminyl–tRNA synthetase

- GluRS

glutamyl–tRNA synthetase

References

- 1.Verkamp E, Kumar A M, Lloyd A, Martins O, Stange-Thomann N, Söll D. In: tRNA Structure, Biosynthesis and Function. Söll D, RajBhandary U L, editors. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 1994. pp. 545–550. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta R. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:9461–9471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schön A, Hottinger H, Söll D. Biochimie. 1988;70:391–394. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(88)90212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilcox M, Nirenberg M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;61:229–236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.61.1.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schön A, Kannangara C G, Gough S, Söll D. Nature (London) 1988;331:187–190. doi: 10.1038/331187a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gagnon Y, Lacoste L, Champagne N, Lapointe J. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14856–14863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.14856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sogin M L, Elwood H J, Gunderson J H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1383–1387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.5.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simpson L. Int Rev Cytol. 1986;99:119–176. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61426-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benne R. Eur J Biochem. 1993;221:9–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson A M, Suyama Y, Dewes H, Campbell D A, Simpson L. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:5427–5445. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.14.5427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hancock K, Hajduk S L. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:19208–19215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mottram J C, Bell S D, Nelson R G, Barry J D. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18313–18317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hauser R, Schneider A. EMBO J. 1995;14:4212–4220. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00095.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dietrich A, Small I, Cosset A, Weil J H, Marechal-Drouard L. Biochimie. 1996;78:518–529. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)84758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider A. Trends Cell Biol. 1994;4:282–286. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(94)90218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dietrich A, Marechal-Drouard L, Carneiro V, Cosset A, Small I. Plant J. 1996;10:101–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.10050913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tarassov I, Entelis N, Martin R P. EMBO J. 1995;14:3461–3471. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07352.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi X, Chen D-H T, Suyama Y. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;65:23–37. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lye L-F, Chen D-H T, Suyama Y. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;58:233–246. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90045-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lima B D, Simpson L. RNA. 1996;2:429–440. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perret V, Garcia A, Grosjean H, Ebel J-P, Florentz C, Giege R. Nature (London) 1990;344:787–789. doi: 10.1038/344787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marechal-Drouard L, Small I, Weil J-H, Dietrich A. Methods Enzymol. 1995;260:310–327. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)60148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braly P, Simpson L, Kretzer F. J Protozool. 1974;21:782–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1974.tb03752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris M E, Moore D R, Hajduk S L. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11368–11376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glick B S, Pon L A. Methods Enzymol. 1995;260:213–223. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)60139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chomczyinski P, Sacchi N. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suyama Y, Hamada J. In: Genetics and Biogenesis of Chloroplasts and Mitochondria. Büchner W N T, Sebald W, Werner S, editors. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1976. pp. 763–770. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weose C R. Sci Am. 1981;244:98–122. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borst P. Trends Genet. 1991;7:139–141. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(91)90374-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blum B, Bakalara N, Simpson L. Cell. 1990;60:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90735-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rusconi C P, Cech T R. EMBO J. 1996;15:3286–3295. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rusconi C P, Cech T R. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2870–2880. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.22.2870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider A, Martin J A, Agabian N. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2317–2322. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahapatra S, Ghosh T, Adhya S. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3381–3386. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.16.3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahapatra S, Adhya S. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20432–20437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]