Abstract

The lifelong addition of neurons to the hippocampus is a remarkable form of structural plasticity, yet the molecular controls over proliferation, neuronal fate determination, survival, and maturation are poorly understood. Expression of Notch1 was found to change dynamically depending on the differentiation state of neural precursor cells. Through the use of inducible gain- and loss-of-function of Notch1 mice we show that this membrane receptor is essential to these distinct processes. We found in vivo that activated Notch1 overexpression induces proliferation, whereas γ-secretase inhibition or genetic ablation of Notch1 promotes cell cycle exit, indicating that the level of activated Notch1 regulates the magnitude of neurogenesis from postnatal progenitor cells. Abrogation of Notch signaling in vivo or in vitro leads to a transition from neural stem or precursor cells to transit-amplifying cells or neurons. Further, genetic Notch1 manipulation modulates survival and dendritic morphology of newborn granule cells. These results provide evidence for the expansive prevalence of Notch signaling in hippocampal morphogenesis and plasticity, suggesting that Notch1 could be a target of diverse traumatic and environmental modulators of adult neurogenesis.

Keywords: adult neurogenesis, Mash1, proneural, stem cell

The great majority of neurons in the mammalian brain are generated prenatally (1–3). Despite the existence of neural precursor cells in almost all regions of the adult brain, neurons are actively generated in large numbers only in the dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus and subependymal zone (SEZ) of the lateral ventricles. Although much progress has been made in identifying factors regulating these progenitors (4–6), our knowledge of the molecular mediators that permit neurogenesis in these regions remains limited (3, 7).

Notch is a transmembrane receptor (Notch1–4 in mammals) that upon ligand binding (Jagged1/2 or Delta 1–4 in mammals) is cleaved, releasing the intracellular portion (NICD) that translocates to the nucleus (8, 9). There, it binds Rbpsuh (also known as RBPjk) and the coactivator Mastermind to initiate transcription of target genes (10). The role of Notch in neural progenitors during postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis has not been investigated in vivo.

Here, we used an inducible form of Cre recombinase spatially restricted to astroglia. Here, we report that ablation or overexpression of Notch1 in glial fibrillary acidic protein (Gfap)-expressing astroglial cells dramatically affects the proliferation, cell fate, and survival of progenitors as well as the maturation of newly generated neurons, displaying the central role of Notch1 in postnatal hippocampal plasticity.

Results

Notch1 and Notch-Signaling Components Are Expressed in the Postnatal Hippocampal Neurogenic Niche.

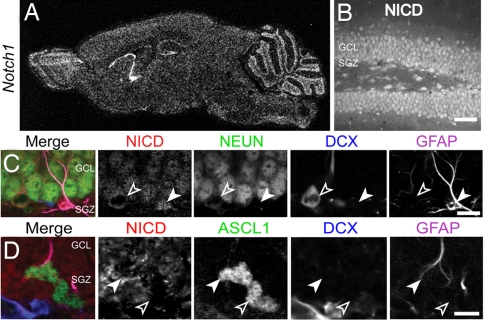

We first examined the expression pattern of Notch1 in the postnatal murine forebrain by using in situ hybridization. Notch1 signal was enriched in the germinal areas, which include the SEZ and the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the DG (Fig. 1A). Multiple components of the Notch pathway, including Hes1, Rbpsuh, Dll-1, and Jag1, were also expressed in this region (supporting information (SI) Fig. 6). An antibody raised against the intracellular portion of Notch (NICD) was used to precisely examine the cell types expressing Notch and determine the subcellular localization of NICD. This antibody should recognize all forms of Notch1 containing the intracellular aspect of the protein, including full-length Notch1 and NICD. NICD was present in the cytoplasm of many Gfap+ cells including the radial glia-like neural progenitors that reside in the SGZ of the DG (94 ± 2% of Gfap+ cells were NICD+, n = 231 cells, three animals; Fig. 1 B and C). This pattern did not significantly change in all ages examined from P5 to 6 months (data not shown). Among the Doublecortin+ (Dcx+) young neurons, NICD was typically absent from the nucleus of the most immature cells—as evidenced by their lack of a prominent process or dendritic arborization in comparison with neighboring, ramified Dcx+ cells (Fig. 1C, SI Fig. 7, data not shown). These more immature Dcx+ cells (also known as Type-3 cells) are thought to be a subpopulation of the transit-amplifying cells (TACs) in the postnatal brain (11, 12). However, mature Dcx+ cells exhibited higher levels of nuclear NICD, which was positively correlated with the age/maturation state of the cell as determined by dendritic complexity, size, and nuclear localization of the cdk inhibitor p27Kip1, an early indicator of postmitotic status (SI Fig. 7).

Fig. 1.

Notch1 and Ascl1 expression in the postnatal hippocampus. (A) In situ hybridization for Notch1 mRNA. (B) Low-magnification confocal image of the immunohistochemical localization of Notch1 in P24 hippocampal coronal sections. Immunoreactivity is present in virtually all mature neurons and astrocytes. (C) Confocal image of a section stained for NICD (red), NeuN (green), Dcx (blue), and Gfap (magenta) taken through the dentate gyrus. There is prominent colocalization of NeuN and NICD in mature neurons as well as significant localization of NICD in the cytoplasm of Gfap+ astrocytes (filled arrowhead) and an absence of NICD in the nearby Dcx+ cell (empty arrowhead). (D) Immunostaining for NICD (red), Ascl1 (green), Dcx (blue), and Gfap (magenta). Ascl1+ doublet with one Ascl1+ nucleus colocalizing with Gfap (filled arrowhead) and the other Gfap- (empty arrowhead). NICD did not colocalize with the mostly nuclear Ascl1 protein in either case. GCL, granule cell layer; SGZ, subgranular zone. (Scale bars: B, 100 μm; C and D, 10 μm.)

Embryonically, as the radial glial cells differentiate, proneural basic helix–loop–helix genes are activated to initiate cell cycle withdrawal and migration in cells with low Notch activity (13, 14). We found a similar pattern as the proneural genes Ascl1 and Ngn2 were expressed sporadically in the SGZ but not in the hilus, granule cell layer, or molecular layer (Fig. 1D, SI Figs. 6 and 8). Ngn2 was also found to frequently colocalize with Dcx (SI Fig. 6). Ascl1-expressing cells were present in substantially greater numbers compared with Ngn2 (data not shown), which is consistent with previous reports (15), and they were largely proliferative in nature as determined by colocalization with the cell cycle marker Ki67 (SI Fig. 8). There was frequently an inverse correlation between the intensity of cytoplasmic NICD and Ascl1 immunostaining (Fig. 1D). However, clear nuclear localization of NICD in precursors was rare but was found almost exclusively in Ascl1+ radial glia (SI Fig. 9). Taken together, the expression of Notch1 in hippocampal radial glia-like precursors and its down-regulation in TACs suggests that Notch1 is involved in the regulation of SGZ radial glia differentiation into committed neural progenitor cells during postnatal neurogenesis in the DG. Furthermore, the positive correlation between more mature NeuN+/Dcx+ cells and nuclear NICD intensity suggests that Notch signaling may also be important for newborn neuron maturation.

Genetic Manipulation of Notch1 Regulates Proliferation of Gfap+ Progenitor Cells in Vivo.

Because of the high toxicity of Notch-related side effects in the gut following the administration of γ-secretase inhibitors (GSIs) and because GSIs can potentially interfere with a host of signaling pathways, injection of GSIs allows for only an acute observation of the effects of chemical inhibition of Notch signaling (16, 17). Thus, we investigated the Notch signaling pathway further in a more precise, genetic manner. Mice that express a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre recombinase under the human Gfap promoter (GCE) (18) were crossed with either loxP-flanked Notch1 mice (19) or, conversely, with conditional NICD transgenic mice (20) to conditionally ablate (GCE; Notch1fl/fl hereafter referred to as “Notch1 cKO” mice) or overexpress activated Notch1 (GCE; NICD hereafter referred to as “NICD Tg” mice) in Gfap+ glial cells and all of their progeny on induction of Cre recombination (Fig. 2 A and B). A dose of 1 mg of tamoxifen was given at postnatal day (P) 10, P12, and P14 to induce recombination. This dosing paradigm was chosen because it limited outward signs of toxicity, permitted mice to gain weight normally, and allowed 100% survival of animals while permitting recombination as determined by reporter expression in significant numbers of Gfap+ cells (Fig. 2C). The control group in all experiments consisted of littermates that were either tamoxifen-treated GCE+; Notch1+/+, GCE; NICD−, GCE−; NICD/+, or GCE−; Notch1fl/fl mice, or vehicle-treated Notch1 cKO or NICD Tg mice (Fig. 2 A and B). No significant differences in proliferation or neuronal differentiation were noted between these groups at the time points examined (data not shown), indicating that Cre toxicity was properly controlled for (21). The efficacy of recombination in Notch1 cKO and NICD Tg mice was assessed by RT-PCR for Hes5. Levels of hippocampal Hes5 mRNA showed equal and opposite changes when compared with control mice (SI Fig. 10). This is consistent with the role of Hes5 as one of the primary effectors of Notch signaling and displays the effectiveness of these inducible mice in recombination of nonreporter, floxed alleles. Similarly, immunostaining for NICD generally showed the expected cell autonomous change in Notch protein levels when used in combination with GFP reporter staining in the Notch1 cKO; GFP and NICD Tg; GFP mice (SI Fig. 10).

Fig. 2.

Cre-mediated manipulation of Notch1. (A and B) Schematic of mouse breedings and ligand-induced Cre recombination. (A) GCE mice are crossed with loxP-flanked (“floxed”) Notch1 mice. GCE; Notch1fl/fl mice are given tamoxifen, causing the Cre-ERT2 fusion protein—which is otherwise bound to heat shock protein 90 in the cytoplasm and thus is inactive—to translocate to the nucleus where it recombines paired loxP sites, ablating the Notch1 protein. (B) GCE mice are crossed with NICD transgenic mice. GCE; NICD mice are given tamoxifen, causing nuclear translocation of the CreER protein which recombines the loxP sites, excising the “STOP” codon and inducing NICD protein transcription and translation. (C) Three doses of Tamoxifen induce recombination in a significant population of SGZ cells as determined by reporter expression (GFP, green). (Scale bar: C, 50 μm.)

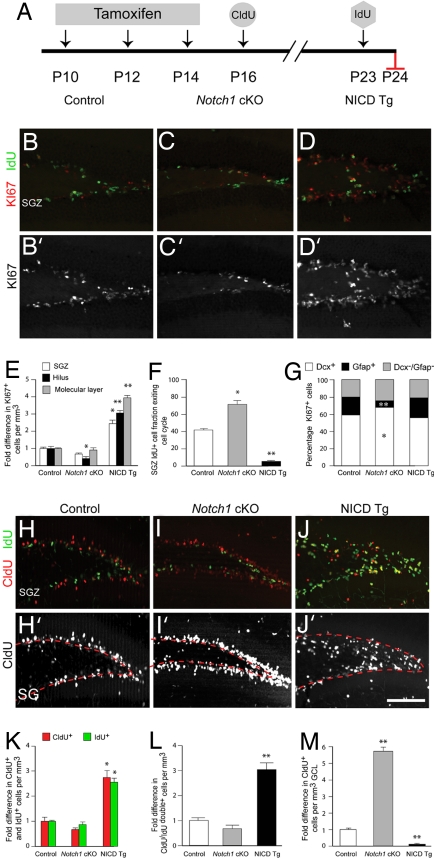

Compared with controls, Notch1 cKO mice killed 1 week after the final tamoxifen treatment displayed a modest but significant drop in proliferation in the hilus (Fig. 3 B, C, and E). This was similar to in vivo results obtained with gamma secretase inhibitors (SI Fig. 11). Rather remarkably, there was a dramatic and widespread 3- to 4-fold increase in Ki67+ cells in NICD Tg mice, which included an overall change in the pattern of proliferation as marker positive cells were widely present in the hilus and molecular layer, regions not noted for such high levels of proliferation at this age (Fig. 3 D and E). We then performed cell cycle analysis by using a Ki67/iodeoxyuridine (IdU) double-labeling method, which allows for cell cycle exit analysis due to the 24-h survival period after IdU injection, allowing some cells to enter G0 after incorporating the thymidine analogue into their DNA—while others reenter (22). Cells exiting the cycle should be IdU+/Ki67−, whereas reentering cells would be IdU+/Ki67+. The percentage of cells exiting the cell cycle in the SGZ (number of cells IdU+/Ki67− divided by number of cells IdU+) was 42 ± 2% in controls vs. 73 ± 6% in Notch1 cKO or 4 ± 2% in NICD Tg mice (Fig. 3F). Also, compared with controls and NICD Tg mice, fewer Gfap+ cells proliferated in Notch1 cKO mice a week postrecombination when the IdU was given (9 ± 1% in Notch1 cKO mice vs. 20 ± 1% in controls; P < 0.001; Fig. 3G).

Fig. 3.

Genetic manipulation of Notch influences cell proliferation, and cell cycle exit. (A) Schematic of the injection paradigm for tamoxifen, CldU, and IdU. (B–D) Ki67 (red)/IdU (green) immunostaining of the dentate gyrus of control (Ctrl), NICD overexpressing (NICD Tg), and Notch1 ablated (Notch1 cKO) animals. (B′–D′) Ki67 signal from B–D shown with enhanced contrast. (E) NICD overexpression drastically increases the number of proliferating cells in the subgranular zone (SGZ), hilus, and molecular layer when compared with controls and Notch1 cKO groups. The average number of Ki67 positive cells per mm3 in control animals was used for normalization. (F) Opposite effects on cell cycle exit are seen when comparing NICD Tg and Notch1 cKO animals with controls. Significantly more cells leave the cell cycle in Notch1 cKO animals than in controls or NICD Tg animals where only 7% of cells leave the cell cycle. (G) The phenotype of proliferating cells is skewed in Notch1 cKO animals where fewer Gfap+ cells proliferate at a reduced level. (Immunostaining for Dcx/Gfap is not shown for the sake of clarity.) (H–J) CldU (red)/IdU (green) immunohistochemistry on DG tissue sections. (H′-J′) CldU signal from H–J is shown with enhanced contrast and the upper limit of the SGZ is labeled with a dotted red line. (K) The number of cells labeled by CldU and IdU increase in the NICD Tg group. The average number of CldU or IdU positive cells per mm3 in control animals was used for normalization. (L) CldU/IdU double-positive cell number increases almost threefold in NICD Tg mice over control and Notch1 cKO animals. The average number of CldU/IdU double-positive cells per mm3 in control animals was used for normalization. (M) CldU+ cells, which synthesized DNA one week before perfusion, remain preferentially in the subgranular zone in NICD Tg animals whereas in Notch1 cKO animals CldU+ cells are preferentially found in the granule cell layer. The average number of CldU-positive cells per mm3 in control animals was used for normalization. Note n = 6 for each experimental group. Asterisks indicate a statistical difference between experimental groups (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001; Student's t test: E–G, K–M). Error bars represent SEM. (Scale bars: B–D′ and H–J′, 100 μm.)

Next, double immunolabeling was performed for IdU with chlorodeoxyuridine (CldU), another marker of DNA synthesis, which had been injected at P16, a week before IdU (injected at P23), and two days after the final tamoxifen injection was performed at P14. Monoclonal antibodies specific for these two thymidine analogues permit specific recognition of either compound in tissue, allowing for the identification of two cohorts of S-phase cells (23). Again, a more than twofold increase in singly labeled CldU+ or IdU+ cells was observed in NICD Tg animals compared with controls and Notch1 cKO mice. When counting CldU and IdU doubly positive cells, which would be indicative of a cell proliferating at both P16 and P23, there was little difference between control animals and Notch1 cKO mice, but there were 3-fold more CldU+/IdU+ cells in NICD Tg mice compared with both other groups (Fig. 3K). Also, the pattern of labeled cells in Notch1 cKO mice was altered in that most CldU+ cells were located in the GCL compared with controls where the proportion of cells in the SGZ vs. GCL was more balanced, indicating increased migration of CldU+ cells in Notch1 cKO mice (Fig. 3 I and M). Conversely, very few cells appeared to migrate into the GCL in the NICD Tg animals, which would be consistent with the lack of cell cycle exit observed (Fig. 3 J and M). These results show that ablating Notch1 in the hippocampus increases the number of progenitors leaving the cell cycle while overexpressing NICD decreases cell cycle exit.

Alteration of Newborn Neuron Number After Genetic Manipulation of Notch1.

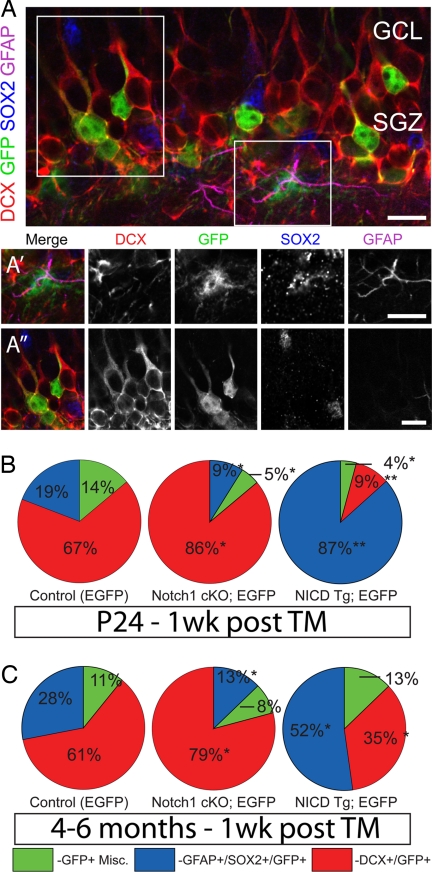

As these groups are genetic mosaics, we bred the Rosa26 (53) and CAG-CAT-GFP (24, 25) reporter strains into each group. By using the same TM delivery protocol and perfusion time as pictured in Fig. 3A, animals in each group were examined for the percentage of SGZ/GCL cells expressing GFP alone (miscellaneous cell types), or in combination with Gfap/Sox2 (astroglia/progenitors), or Dcx (new neurons). In agreement with the cell cycle exit data, Notch1 loss caused a significant increase in new neurons at the expense of progenitors and miscellaneous cell types (Fig. 4B). Conversely, GFP cells in NICD Tg animals overwhelmingly colocalized with Gfap and Sox2, indicating the NICD functions to maintain glial progenitor cells in the SGZ/GCL (Fig. 4B). There was no apparent difference in the average recombination rate or density of recombined cells across the groups or between reporter strains (data not shown). Overall cell death was increased in Cre+ controls, Notch1 cKO and NICD Tg animals but examination of the phenotype of dying cells did not yield a pattern indicating that apoptosis was a significant cause of the shift in cell fates (SI Fig. 12). The increase in death seen in Cre+ controls when compared with Cre− animals indicates that Cre toxicity is a significant factor in this assay and thus warrants caution in interpreting survival data from such Cre lines (21). This reciprocal change in cell fate was also seen in comparable young adult mice but the percentages were less than those seen in young animals (Fig. 4C). These results display that cell autonomous manipulation of Notch1 causes a dynamic shift in the ratio of Gfap-positive stem cells versus newborn neurons.

Fig. 4.

Cell autonomous changes in cell fate in the DG. (A) Induced GFP (green) reporter expression in the SGZ in tissue immunostained for Dcx (red), Sox2 (blue), and Gfap (magenta). Example of a GFP+ glial cell (A′) showing expression of Sox2 and Gfap. (A″) GFP+/Dcx+ neurons in the GCL. (B) Notch1 cKO animals show a preferential generation of neurons, but NICD Tg mice display a dramatic maintenance of glial cells at the expense of neurons. (C) This same reciprocal change in cell fates is seen in 4- to 6-month-old mice given tamoxifen 1 week before killing. Note n = 4 for each experimental group. Asterisks indicate a statistical difference between experimental groups (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001; Student's t test; B and E). Error bars represent SEM. (Scale bars: A-A″, C-C′, 10 μm; D, 50 μm.)

Notch is a Critical Modulator of Dendritic Arborization in Newly Generated Neurons.

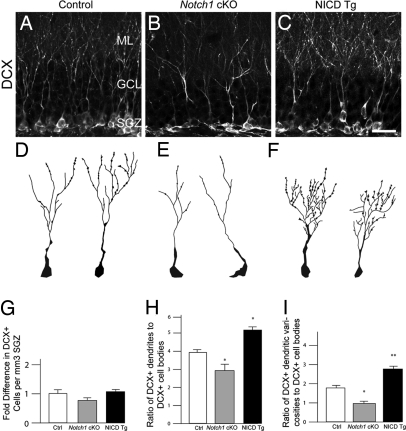

Because of its known effects on neurite outgrowth in vitro (26–28), we examined the morphology of newly generated, migrating/differentiating neurons at P37 by using Dcx immunostaining, which labels the maturing dendritic arbor of these young cells. Dcx marks newborn neurons that have been born after tamoxifen treatment at P10, P12, and P14 (11, 18). Despite a lack of significant alteration in the totals number of Dcx+ cell bodies in NICD Tg and Notch1 cKO groups (Fig. 5G), there was a remarkable and disproportionate change in dendritic arborization and branching (Fig. 5 A–F). Notch1 cKO animals had significantly less complex arborization than controls (Fig. 5 A, B, D, E, and H). NICD Tg animals showed the greatest amount of dendritic complexity, stubby arbors, and more numerous varicosities (Fig. 5 C, F, H, and I). The varicosities are thought to be indicative of more immature granule neurons and typically have no relationship with spine development (29). Thus, in addition to regulating proliferation, and differentiation of neural progenitors, Notch signaling regulates dendritic morphology in the newborn, maturing granule cells.

Fig. 5.

Notch-signaling modulates the dendritic arborization of maturing hippocampal neurons. (A–C) Confocal image of Dcx immunohistochemistry in the dentate gyrus at P37. Representative examples of Dcx+/GFP+ neurons in D Control, (E) Notch1 cKO, and (F) NICD Tg mice. GFP will label only newly born cells. Representative examples of the more ramified cells in each group are show. (G) Dcx+ cell numbers are not significantly different in the SGZ of NICD Tg and Notch1 cKO animals when compared with controls. The average number of Dcx+ cells per mm3 in control animals was used for normalization. (H) NICD Tg animals display more dendrites per Dcx+ cell body. Notch1 cKO animals show a significant drop in dendritic complexity. (I) NICD Tg animals have more varicosities per Dcx+ cell whereas Notch1 cKO mice show a significant decrease. Note n = 6 for each experimental group. Asterisks indicate a statistical difference between experimental groups (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001; Student's t test; G–I). Error bars represent SEM. (Scale bars: A–C, 30 μm.)

Discussion

Notch Mediates a Binary Switch Between Neural Stem or Precursor Cells and Committed Progenitor Cell Types.

By using inducible loss- and gain-of-function mice, our data demonstrate that Notch1 plays a role in the proliferation, cell fate determination, and maturation of cells in a context-dependent manner that can be correlated with subcellular distribution of the protein (SI Fig. 13). Previous studies have indicated that Notch biases cells toward an astrocytic fate at the expense of neurons and glia (30–32). These results have been found in vivo and in vitro. In vitro studies were performed by using retrovirally transduced, growth factor-dependent neural stem cells expressing NICD (31). In vivo studies used retrovirus or electroporation to express NICD in proliferating cells (30, 32–34). Indeed, we have confirmed that these methods do largely block neurogenesis (SI Fig. 14, data not shown). NICD overexpression leads to the maintenance of Gfap-expressing neural stem cells in vivo and promotes astrogliogenesis in vitro under differentiating conditions. We have seen that the reciprocal phenotype is observed on cell autonomous loss of Notch1 or on forced expression of a dominant-negative form of Mastermind (DN-MAML) (35, 36)—which functions to block the nuclear signaling of all four notch receptors (SI Fig. 14). Neural stem cells expressing DN-MAML continued to proliferate in the presence of EGF/FGF2 (data not shown) but largely lost the ability to generate glia and proliferate under differentiation conditions, suggesting that Notch1 functions to maintain neural stem cells whereas transit-amplifying cells use other signaling pathways or noncanonical Notch signaling (SI Fig. 13). The inability of DN-MAML expression to promote neurogenesis—as is seen after Notch1 ablation in the dentate gyrus—indicates that active neurogenic signals from the microenvironment are needed to promote neurogenesis even in the absence of antineuronal Notch signaling.

Reactive Neurogenesis in the Postnatal Brain.

It is noteworthy that the pattern of hyperproliferation and morphological plasticity shares similarities with the alterations in neurogenesis seen after trauma, indicating that Notch1 could be an in vivo modulator of posttrauma neurogenic responses (37–40). Consistent with this idea, Hes5 and Ascl1 mRNA levels are significantly altered in the SGZ after status epilepticus (41) and ischemia (42). Seizures are known to be one of the most profound stimulators of dentate gyrus neurogenesis. Different experimental models show varying degrees of neurogenesis. Strikingly, increased neurogenesis has been seen concurrently with dramatic dendritic changes in the newborn population (40). Furthermore, because of the transient increase in neurogenesis we observed, it is conceivable that Notch signaling is activated in a graded manner by other potent stimulators of adult neurogenesis such as running (43), ischemia (44), and focal lesion (45). In particular, it has recently been observed that Notch signaling mediates profound postischemia responses (46), and dynamic changes in the expression pattern of Notch-related molecules suggests the involvement of Notch in the postlesion (47) and postischemia neurogenic response (42, 44).

Dendritic Alterations in Newborn Neurons.

We also show that genetic manipulation of Notch in newborn neurons in the hippocampus alters the dendritic morphology. In vitro, Notch was found to have profound effects on the arborization of cortical neurons (26–28). Our results are consistent with this, showing that the dendritic arborization of newly generated neurons is modulated in vivo in a dosage-dependent manner based on the cleavage of the Notch receptor. Nevertheless, as Notch signaling levels vary with seizure (41), ischemia (46), and potentially many other stimuli, such changes in dendrite arborization may not be entirely artificial and can reflect physiological challenges. For example, it is has recently been shown that voluntary exercise can significantly alter dendritic morphology and complexity in the dentate gyrus (48, 49), in addition to its known function in neuronogenesis (43).

Our data illuminate the complexity of Notch signaling as a whole in the transition from progenitor to mature neuron, displaying its central role during postnatal neurogenesis and raising the possibility that it plays a part in the plasticity resulting from trauma or environmental stimulus. Notch acts in one context to stimulate proliferation of endogenous progenitors, yet in maturing neurons modulates structural plasticity and survival pathways, suggesting that differential clinical manipulation of Notch could aid in multiple aspects of functional recovery after disease, trauma, or pathological aging.

Note.

After the completion of these experiments, Mizutani et al. (50) reported that neural stem cells and committed progenitors display differential levels of Notch signaling in the embryonic brain, consistent with our findings in the postnatal and adult brain.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

GCE; R26R/R26R, GCE; Z/EG/+, GCE;+/+, +/Notch1fl/fl, +/NICD, GCE;Notch1fl/fl (Notch1 cKO), or GCE;NICD (NICD Tg) at the ages noted were administered 75 mg/kg of tamoxifen (Sigma) in corn oil by i.p. injection or oral gavage at the times noted. [No differences were noted between delivery methods, as has been described (51).] Littermates were used as controls. CldU or IdU (Sigma) were given at the times noted as a single i.p. injection equimolar to 100 mg/kg of bromodeoxyuridine. (Most experiments were performed on a C57/BL6 background.) Two-month-old CD1 mice were given i.p. injections of DAPT (Sigma) 200 mg/kg, DBZ (Calbiochem) 4 mg/kg, or DMSO (Sigma) every 12 h for 3 days based on studies characterizing in vivo activity (16, 52).

Statistical Analysis.

A two-tailed unpaired Student's t test was used for analyses of all experiments presented in Figs. 3–5. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Details on other methods are available in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank C. Anderson, J. Bao, and M. Pappy for excellent experimental assistance; D. Anderson, J. Aster, M. Colbert, A. Israel, J. Johnson, W. Pear, F. Radtke, and J. Shen for mice and reagents; and J. Arellano, K. Burns, R. Duman, M. Givogri, K. Hashimoto-torii, K. Herrup, C. Y. Kuan, J. Loturco, R. Rasin, M. Sarkisian, T. Town, and members of the P.R. and N.Š. laboratories for helpful discussions, technical support, and comments. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 MH067715, HD045481, AG019394, and NS047200; the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation Grant FY05-73; and the Kavli Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0710156104/DC1.

References

- 1.Rakic P. Limits of neurogenesis in primates. Science. 1985;227(4690):1054–1056. doi: 10.1126/science.3975601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhardwaj RD, et al. From the cover: Neocortical neurogenesis in humans is restricted to development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(33):12564–12568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605177103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gage FH. Mammalian neural stem cells. Science. 2000;287(5457):1433–1438. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lie DC, et al. Wnt signalling regulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Nature. 2005;437(7063):1370–1375. doi: 10.1038/nature04108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai K, et al. Sonic hedgehog regulates adult neural progenitor proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(1):21–27. doi: 10.1038/nn983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Machold R, et al. Sonic hedgehog is required for progenitor cell maintenance in telencephalic stem cell niches. Neuron. 2003;39(6):937–950. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00561-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lledo PM, Alonso M, Grubb MS. Adult neurogenesis and functional plasticity in neuronal circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(3):179–193. doi: 10.1038/nrn1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand MD, Lake RJ. Notch signaling: Cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science. 1999;284(5415):770–776. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroeter EH, Kisslinger JA, Kopan R. Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-induced proteolytic release of intracellular domain. Nature. 1998;393(6683):382–386. doi: 10.1038/30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bray SJ. Notch signalling: A simple pathway becomes complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(9):678–689. doi: 10.1038/nrm2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown JP, et al. Transient expression of doublecortin during adult neurogenesis. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467(1):1–10. doi: 10.1002/cne.10874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plumpe T, et al. Variability of doublecortin-associated dendrite maturation in adult hippocampal neurogenesis is independent of the regulation of precursor cell proliferation. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Britz O, et al. A role for proneural genes in the maturation of cortical progenitor cells. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16(Suppl 1):i138–i151. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castro DS, et al. Proneural bHLH and Brn proteins coregulate a neurogenic program through cooperative binding to a conserved DNA motif. Dev Cell. 2006;11(6):831–844. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pleasure SJ, Collins AE, Lowenstein DH. Unique expression patterns of cell fate molecules delineate sequential stages of dentate gyrus development. J Neurosci. 2000;20(16):6095–6105. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06095.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Es JH, et al. Notch/gamma-secretase inhibition turns proliferative cells in intestinal crypts and adenomas into goblet cells. Nature. 2005;435(7044):959–963. doi: 10.1038/nature03659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barten DM, et al. Gamma-secretase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease: Balancing efficacy and toxicity. Drugs R D. 2006;7(2):87–97. doi: 10.2165/00126839-200607020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganat YM, et al. Early postnatal astroglial cells produce multilineage precursors and neural stem cells in vivo. J Neurosci. 2006;26(33):8609–8621. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2532-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lutolf S, et al. Development. 2. Vol. 129. UK: Cambridge; 2002. Notch1 is required for neuronal and glial differentiation in the cerebellum. pp. 373–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang X, et al. Notch activation induces apoptosis in neural progenitor cells through a p53-dependent pathway. Dev Biol. 2004;269(1):81–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breunig JJ, et al. Everything that glitters is not gold: A critical review of analysis of neural precursor / stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.008. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chenn A, Walsh CA. Regulation of cerebral cortical size by control of cell cycle exit in neural precursors. Science. 2002;297(5580):365–369. doi: 10.1126/science.1074192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vega CJ, Peterson DA. Stem cell proliferative history in tissue revealed by temporal halogenated thymidine analog discrimination. Nat Methods. 2005;2(3):167–169. doi: 10.1038/nmeth741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura T, Colbert MC, Robbins J. Neural crest cells retain multipotential characteristics in the developing valves and label the cardiac conduction system. Circ Res. 2006;98(12):1547–1554. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000227505.19472.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burns KA, et al. Nestin-CreER mice reveal DNA synthesis by nonapoptotic neurons following cerebral ischemia-hypoxia. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(11):2585–2592. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sestan N, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rakic P. Contact-dependent inhibition of cortical neurite growth mediated by notch signaling. Science. 1999;286(5440):741–746. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berezovska O, et al. Notch1 inhibits neurite outgrowth in postmitotic primary neurons. Neuroscience. 1999;93(2):433–439. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Redmond L, et al. Nuclear Notch1 signaling and the regulation of dendritic development. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3(1):30–40. doi: 10.1038/71104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones SP, et al. Maturation of granule cell dendrites after mossy fiber arrival in hippocampal field CA3. Hippocampus. 2003;13(3):413–427. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaiano N, Nye JS, Fishell G. Radial glial identity is promoted by Notch1 signaling in the murine forebrain. Neuron. 2000;26(2):395–404. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanigaki K, et al. Notch1 and Notch3 instructively restrict bFGF-responsive multipotent neural progenitor cells to an astroglial fate. Neuron. 2001;29(1):45–55. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00179-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jadhav AP, Mason HA, Cepko CL. Development. 5. Vol. 133. UK: Cambridge; 2006. Notch 1 inhibits photoreceptor production in the developing mammalian retina. pp. 913–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chambers CB, et al. Development. 5. Vol. 128. UK: Cambridge; 2001. Spatiotemporal selectivity of response to Notch1 signals in mammalian forebrain precursors. pp. 689–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizutani K, Saito T. Development. 6. Vol. 132. UK: Cambridge; 2005. Progenitors resume generating neurons after temporary inhibition of neurogenesis by Notch activation in the mammalian cerebral cortex. pp. 1295–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maillard I, et al. Mastermind critically regulates Notch-mediated lymphoid cell fate decisions. Blood. 2004;104(6):1696–1702. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weng AP, et al. Growth suppression of pre-T acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells by inhibition of notch signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(2):655–664. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.2.655-664.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pierce JP, et al. Mossy fibers are the primary source of afferent input to ectopic granule cells that are born after pilocarpine-induced seizures. Exp Neurol. 2005;196(2):316–331. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scharfman HE, Goodman JH, Sollas AL. Granule-like neurons at the hilar/CA3 border after status epilepticus and their synchrony with area CA3 pyramidal cells: Functional implications of seizure-induced neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2000;20(16):6144–6158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06144.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parent JM, et al. Aberrant seizure-induced neurogenesis in experimental temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2006;59(1):81–91. doi: 10.1002/ana.20699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Overstreet-Wadiche LS, et al. Seizures accelerate functional integration of adult-generated granule cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26(15):4095–4103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5508-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elliott RC, et al. Differential regulation of basic helix-loop-helix mRNAs in the dentate gyrus following status epilepticus. Neuroscience. 2001;106(1):79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawai T, et al. Changes in the expression of Hes5 and Mash1 mRNA in the adult rat dentate gyrus after transient forebrain ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 2005;380(1–2):17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao C, et al. Distinct morphological stages of dentate granule neuron maturation in the adult mouse hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2006;26(1):3–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3648-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Felling RJ, et al. Neural stem/progenitor cells participate in the regenerative response to perinatal hypoxia/ischemia. J Neurosci. 2006;26(16):4359–4369. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1898-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emery DL, et al. Newly born granule cells in the dentate gyrus rapidly extend axons into the hippocampal CA3 region following experimental brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22(9):978–988. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arumugam TV, et al. Gamma secretase-mediated Notch signaling worsens brain damage and functional outcome in ischemic stroke. Nat Med. 2006;12(6):621–623. doi: 10.1038/nm1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Givogri MI, et al. Notch signaling in astrocytes and neuroblasts of the adult subventricular zone in health and after cortical injury. Dev Neurosci. 2006;28(1–2):81–91. doi: 10.1159/000090755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eadie BD, Redila VA, Christie BR. Voluntary exercise alters the cytoarchitecture of the adult dentate gyrus by increasing cellular proliferation, dendritic complexity, and spine density. J Comp Neurol. 2005;486(1):39–47. doi: 10.1002/cne.20493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Redila VA, Christie BR. Exercise-induced changes in dendritic structure and complexity in the adult hippocampal dentate gyrus. Neuroscience. 2006;137(4):1299–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mizutani K, et al. Differential Notch signalling distinguishes neural stem cells from intermediate progenitors. Nature. 2007;449(7160):351–355. doi: 10.1038/nature06090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Joyner AL, Zervas M. Genetic inducible fate mapping in mouse: Establishing genetic lineages and defining genetic neuroanatomy in the nervous system. Dev Dyn. 2006;235(9):2376–2385. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.El Mouedden M, et al. Reduction of Abeta levels in the Sprague Dawley rat after oral administration of the functional gamma-secretase inhibitor, DAPT: A novel non-transgenic model for Abeta production inhibitors. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12(6):671–676. doi: 10.2174/138161206775474233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mao X, Fujiwara Y, Orkin SH. Improved reporter strain for monitoring Cre recombinase-mediated DNA excisions in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(9):5037–5042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.