Abstract

Although homomeric channels assembled from the α9 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) subunit are functional in vitro, electrophysiological, anatomical, and molecular data suggest that native cholinergic olivocochlear function is mediated via heteromeric nAChRs composed of both α9 and α10 subunits. To gain insight into α10 subunit function in vivo, we examined olivo cochlear innervation and function in α10 null-mutant mice. Electrophysiological recordings from postnatal (P) days P8–9 inner hair cells revealed ACh-gated currents in α10+/+ and α10+/− mice, with no detectable responses to ACh in α10−/− mice. In contrast, a proportion of α10−/− outer hair cells showed small ACh-evoked currents. In α10−/− mutant mice, olivocochlear fiber stimulation failed to suppress distortion products, suggesting that the residual α9 homomeric nAChRs expressed by outer hair cells are unable to transduce efferent signals in vivo. Finally, α10−/− mice exhibit both an abnormal olivocochlear morphology and innervation to outer hair cells and a highly disorganized efferent innervation to the inner hair cell region. Our results demonstrate that α9−/− and α10−/− mice have overlapping but nonidentical phenotypes. Moreover, α10 nAChR subunits are required for normal olivocochlear activity because α9 homomeric nAChRs do not support maintenance of normal olivocochlear innervation or function in α10−/− mutant mice.

Keywords: cochlea, electrophysiology, inner hair cells, outer hair cells

The sensory epithelia responsible for hearing (cochlea) and balance (saccule, utricle, and cristae ampullaris) share a unique subset of cells that respond to mechanical cues. These hair cells possess apical mechanoreceptors and specialized basolateral membranes that act in concert to transduce mechanical stimuli into electrical signals (1). In mammals, cochlear hair cells are anatomically and functionally divided into inner and outer hair cells (IHCs and OHCs, respectively). IHCs are responsible for transducing acoustic stimuli and exciting the fibers of the cochlear nerve, whereas OHC are involved in the mechanical amplification and fine tuning of cochlear vibrations via their electromotile response (2, 3).

Both OHCs and type-I spiral ganglion cell processes receive descending cholinergic innervation, which originates in the superior olivary complex (4). Although the precise role of the olivocochlear (OC) system in hearing remains uncertain, the effects of activating efferent terminals forming synapses with OHCs have been well described (5–7). Acetylcholine (ACh), the principal neurotransmitter released by OC terminals (8), binds to postsynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) leading to calcium influx, activation of small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels, and subsequent hair cell hyperpolarization (9–17). As with electrical stimulation of the olivocochlear bundle (10), the result of OHC hyperpolarization is to reduce auditory afferent output via suppression of basilar membrane motion (18).

Combined immunohistochemical (19, 20), electrophysiological (9, 21–23), molecular biological (7, 24), and in situ hybridization studies (21, 25–27) suggest that the nAChR subtype present at efferent hair cell synapses is assembled from both α9 and α10 subunits. Although α10 subunits do not form ACh-gated ion channels, α9 subunits form functional homomeric nAChRs in Xenopus oocytes (25). Importantly, coinjection of cRNAs encoding both the α9 and α10 subunits results in an ≈100-fold increase in the amplitude of ACh-gated currents, and the resulting heteromeric α9α10 nAChRs possess the distinctive pharmacological and biophysical properties of native hair cell cholinergic receptors (21, 28).

Composed exclusively of α subunits, the hair cell α9α10 nAChR subtype is unusual. Moreover, the subunit composition and heterologous expression data raise some interesting questions. For example, do hair cell α9 homomeric nAChRs function in vivo (as they do in vitro)? If so, could they support normal hair cell cholinergic biology? If not, what added functionality is contributed by the α10 subunit? Is expression of the α10 subunit essential for normal hearing or proper efferent innervation of hair cell synapses? Is the α10 protein required to obtain a full complement of OC efferent effects in vivo? To gain insight into these questions and examine the role of α10 subunits in mammalian hair cells, we engineered a strain of mice that harbors a null mutation in the Chrna10 gene. Here, we report that even though a proportion of OHCs remain minimally responsive to ACh (because of the presence of residual α9 homomeric receptors), α10 subunit expression and assembly of heteromeric α9α10 nAChRs are required for both normal efferent activation of these hair cells and for development (or maintenance) of normal OC synapse structure and function.

Results

Hair Cell Electrophysiology.

Given that expression levels of genes important for efferent function were generally unaltered in α10−/− mice save for the α10 gene itself [supporting information (SI) Table 1 and SI Methods], and that nAChR α9 subunits form functional homomeric channels in Xenopus oocytes (21, 25), we sought to further investigate the functional state of the hair cells in the α10−/− mice, with special emphasis on determining whether currents attributable to α9 homomers could be identified.

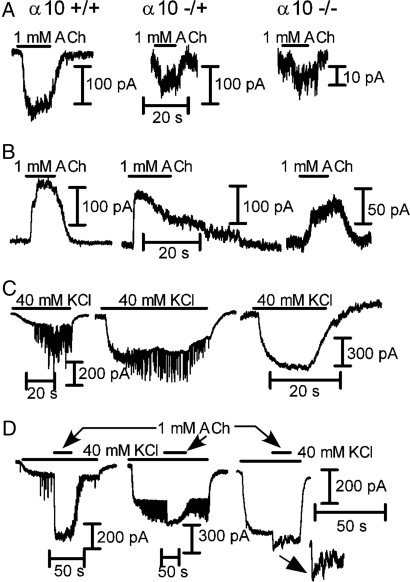

We compared cholinergic responses of IHCs isolated from α10+/+, α10+/−, and α10−/− mice at postnatal (P) days P8–9, a developmental time when IHCs are transiently innervated by OC terminals (29, 30) and robustly respond to ACh. Inward currents were elicited at −90 mV by the application of 100 μM ACh to IHCs from both α10+/+ (−200 ± 48 pA; n = 3 of 3 cells tested) and α10+/− (−517 ± 50 pA, n = 3 of 3 cells tested) mice (Fig. 1A). In contrast, no response to either 100 μM or 1 mM ACh (n = 0 of 7 cells tested) was detected in IHCs from α10−/− mice. IHCs from both α10+/+ and α10+/− mice also exhibited outward currents at −40mV (Fig. 1B; wild type: 236 ± 44 pA; n = 3 of 3 cells tested; heterozygous: 278 ± 80 pA; n = 3 of 3 cells tested), indicating functional coupling to SK channels (9, 28), whereas no response was found in IHCs from α10−/− mice (n = 0 of 8 cells tested).

Fig. 1.

IHC whole-cell recordings from P8–9 N5 B6.Cast α10+/+, α10+/−, and α10−/− mice. (A) Effects of ACh at Vhold of −90 mV in the three genotypes. (B) Same as A at a Vhold of −40 mV. Note that in A and B, no responses could be elicited by either 100 or 1,000 μM ACh from α10−/− mice. (C) Superfusion of the cells with high potassium (40 mM at Vhold of −90 mV) causes a change in the holding current due to the change in the K+ equilibrium potential in the three genotypes. In both the α10+/+ and α10+/− mice (Left and Middle, respectively), there are synaptic currents appearing on top of the holding current because of the release of ACh from depolarized efferent terminals. No synaptic activity can be observed in IHCs from α10−/− mice (Right). No currents could be elicited upon challenging the cells with either 100 or 1,000 μM ACh. Results are representative of those obtained in three IHCs from α10+/+ mice, three IHCs from α10+/− mice, and eight IHCs from three α10−/− mice. Holding currents at −90 mV ranged from −100 to −200 pA and from −200 to −400 pA in 5.8 and 40 mM K+, respectively. At −40 mV in 5.8 mM K+, holding currents ranged from 0 to 200 pA.

To determine whether IHCs respond to synaptic release of ACh, the preparation was superfused with a buffer containing 40 mM KCl to depolarize the efferent terminals, thus increasing the frequency of ACh release (9, 28). KCl depolarization generated ACh-inducible synaptic currents in IHCs from both α10+/+ (n = 3 of 3 cells tested) and α10+/− (n = 3 of 3 cells tested) mice (Fig. 1C Left and Center) but not in IHCs from α10−/− mice (n = 0 of 8 cells tested; Fig. 1C Right). Moreover, even when adding either 100 μM or 1 mM ACh in the presence of 40 mM K+ (Fig. 1C), a procedure that uncovers hair cells with small responses to ACh due to the change in the K+ equilibrium potential and the concomitant increase in the driving force for K+ ions at the holding voltage (−90 mV) (9), no responsive IHCs were observed.

At −90 mV, 1 mM ACh evoked inward currents in OHCs from both α10+/+ (−103 ± 24 pA; 6 of 7 cells tested) and α10+/− (−76 ± 40 pA; 3 of 4 cells tested) mice (Fig. 2A). In α10−/−, only 1 of 11 cells tested responded to 1 mM ACh (inward current of −13 pA). To determine whether ACh-evoked responses were coupled to activation of SK channels, OHCs were voltage-clamped at −40 mV and perfused with 1 mM ACh (Fig. 2B). OHCs from α10+/+ (12 of 13 cells tested) and α10+/− (16 of 17 cells tested) exhibited robust outward currents (104 ± 46 and 171 ± 37 pA, respectively). In α10−/−, consistent with the lack of ACh responses in most of the cells tested at −90 mV, only 2 of 24 OHCs responded to ACh with an outward current (amplitudes of 30 and 58 pA). In 40 mM KCl (Fig. 2C), OHCs from both α10+/+ and α10+/− mice exhibited synaptic currents (8 of 13 and 15 of 16 cells, respectively). Synaptic currents were not detected in OHCs from α10−/− mice (n = 0 of 24 cells tested; Fig. 2C). After application of 1 mM ACh plus 40 mM KCl (Fig. 2D), the number of responsive OHCs increased: 10 of 11 in α10+/+ and 15 of 15 in α10+/− (range from −160 to −1,300 pA). In contrast to what was observed in IHCs, boosting the system by elevating external K+ revealed small inward currents (−40 to −151 pA) in 11 of 24 OHCs from α10−/− mice, highly suggestive of α9 subunits assembling into functional homomeric receptors.

Fig. 2.

OHC whole-cell recordings from P10–13 N5-N8 B6.Cast α10+/+, α10+/−, and α10−/− mice. (A) Representative records of the effects of 1 mM ACh at a Vhold of −90 mV in the three genotypes (positive/studied cells = 6/7 α10+/+; 3/4 α10+/−; 1/11 α10−/−). (B) Same as A at a Vhold of −40 mV (positive/studied cells = 12/13 α10+/+; 16/17 α10+/−; 2/24 α10−/−). (C) Representative responses obtained upon superfusion of the cells with high potassium (40 mM at Vhold of −90 mV). A change in holding current due to the change in the K+ equilibrium potential can be observed in all three cases. In both the α10+/+ and α10+/− mice (Left and Middle, respectively), there are synaptic currents appearing on top of the holding current because of the release of ACh from depolarized efferent terminals (8 of 13 OHCs and 15 of 16 OHCs from α10+/+ and α10+/− mice, respectively). No synaptic activity can be observed in OHCs from α10−/− mice (Right; n = 24 cells). (D) After boosting the system by increasing the K+ driving force, almost all OHCs studied from both the α10+/+ and α10+/− mice (Left and Middle, respectively) showed ACh-evoked responses (Vhold of −90 mV; positive/studied cells = 10/11 α10+/+, 15/15 α10+/−). Interestingly, OHCs from α10−/− mice also exhibited small but consistent inward currents in response to ACh (11 of 24 cells studied, Right and Inset). Holding currents at −90 mV ranged from −100 to −300 pA and from -−250 to −600 pA in 5.8 and 40 mM K+, respectively. At −40 mV in 5.8 mM K+, holding currents ranged from 0 to 200 pA.

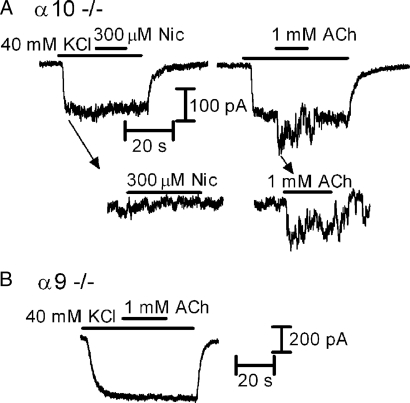

Both α9 homomeric and α9α10 heteromeric nAChRs can be distinguished from other nAChR subtypes by their unusual pharmacological profiles (21, 25, 31). In particular, activation by ACh but lack of activation by nicotine is a hallmark of receptors assembled from α9 and α10 subunits (21, 25, 31, 32). As shown in Fig. 3A, 300 μM nicotine did not evoke currents in OHCs that were responsive to ACh from α10−/− mice (n = 0 of 3 cells tested). Considered together, our quantitative RT-PCR (SI Table 1) and electrophysiological data suggest that ACh-evoked currents observed in Chrna10−/− OHCs are mediated by homomeric α9 nAChRs. The lack of comparable activity in Chrna9−/− mice (Fig. 3C; n = 0 of 14 cells tested) further supports this notion.

Fig. 3.

Whole-cell recordings in OHCs from cochlear preparations (medio-apical turns) excised from P10–13 α10−/−and α9−/− mice. (A) In OHCs from α10−/− mice, no responses to 300 μM nicotine (Left and Inset) could be obtained in the same OHCs in which 1 mM ACh elicited an inward current (Middle and Inset; n = 3). (B) Representative record of the lack of effect of 1 mM ACh applied in the presence of 40 mM KCl in OHCs from α9−/− mice (n = 14 cells). Vhold of −90 mV in both A and B.

Cochlear Function.

Because OC feedback can alter cochlear thresholds and is required for development of normal cochlear function and morphology (6, 7), we investigated baseline cochlear response sensitivity in α10−/− mice. No differences in threshold or suprathreshold responses (SI Fig. 6) were detected in either auditory brainstem responses (ABRs), the summed activity of auditory neurons evoked by short tone pips or distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs), which are distortions of the sound input created and amplified by normally functioning OHCs and actively transduced out of the cochlea and measured in the ear canal.

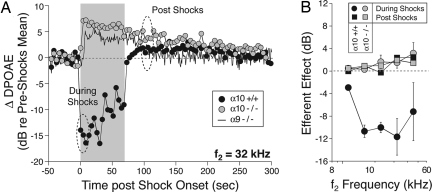

To test the effects of α10 gene deletion on OC function in vivo, we measured the effects of OC electrical activation on DPOAE amplitudes. DPOAE amplitudes in wild-type mice always show a fast suppression after OC fiber stimulation that is visible in the first DPOAE measurement after shock train onset (Fig. 4A). Suppression is greatest for mid-frequency tones (Fig. 4B), mirroring the peak of OHC efferent terminal density in the middle of the cochlear spiral (33).

Fig. 4.

Olivocochlear efferent function. Deletion of either the α9 or the α10 nAChR eliminates suppressive olivocochlear effects, leaving only a during-shocks response enhancement, which slowly decays back to baseline after shock offset. (A) Sample runs of the olivocochlear efferent assay from a wild-type, an α10−/−, and an α9−/− mouse. DPOAE amplitudes are repeatedly measured before, during, and after a 70-second train of shocks to the olivocochlear bundle at the floor of the IVth ventricle. DPOAE amplitudes are normalized to the mean preshocks value in each case. The dashed ellipses indicate the time windows during which efferent-evoked effects are sampled to produce the mean data in B. (B) Mean (±SEM) effects of olivocochlear stimulation in groups of α10+/+ vs. α10−/− ears. The “during-shocks” value is defined as the difference in DPOAE amplitude between the mean of the first three during-shocks points and the preshocks baseline; the postshocks value is defined by averaging the 7th to 12th points after shock-train offset.

In an earlier study of α9−/− mice, we used a paradigm in which DPOAEs were alternately measured with and without shocks in repeating 6-second trial intervals. In this paradigm, only suppressive effects of olivocochlear stimulation are seen in α9+/+ mice, and all these suppressive effects are eliminated by α9 gene deletion (7). Since that time, we modified our paradigm to one in which the shock train is maintained for 70 seconds and DPOAEs measured before, during, and after this shock epoch. This paradigm reveals a robust postshocks enhancement of DPOAE amplitudes in both α9+/+ and α9−/− mice (Fig. 4A) (also see ref. 34). In contrast to the fast-onset suppression, slow postshocks enhancement tends to increase monotonically in amplitude with increasing stimulus frequency (Fig. 4B).

In α10−/− mice, efferent-evoked suppression of DPOAEs was never observed (n = 12 mice tested, each ear tested at six different DPOAE-evoking frequencies). Interestingly, a during-shocks enhancement was observed in most α10−/− ears evaluated (7 of 10 ears tested that met DPOAE threshold criteria), which, after shock-train offset, behaved similarly to the normal postshocks enhancement observed in wild types both with respect to its amplitude and offset time constant (Fig. 4A). This result is similar to that observed in α9−/− (34) (reassessed and included in Fig. 4 for comparison).

Cochlear Morphology.

In the OHC region, efferent innervation in wild-type mice consists of clusters of synaptic terminals under the three rows of OHCs, except at the apical extreme of the cochlea. Similar to observations in α9−/− mice (7), efferent terminals contacting OHCs of α10−/− mice were larger in size but fewer in number (SI Fig. 7). The terminals measured an average 2.90 μm in diameter (±0.09 μm), ≈20% larger than those from the same cochlear region of wild-type mice (2.38 ± 0.07 μm; t test, P < 0.00001). Although OHCs of α10−/− mice were contacted by abnormally large efferent terminals, and were fewer in number than wild types, the number of those terminals under each OHC was greater than that in α9−/− mice (7). A count of 100 random OHCs from contiguous 250-μm regions of the middle turns of three α10−/− mice revealed an equal probability of the OHCs possessing either one or multiple efferent terminals (50% occurrence for each case) whereas 67% of synaptic contacts with OHCs in α9−/− mice consisted of single boutons. Only row three of α10−/− mice possessed a statistically significant number of single terminals (P < 0.01) compared with multiply innervated hair cells within the same row of wild-type mice. However, unlike α10+/+ mice, OHCs of the null-mutant mice contacted by three or more efferent terminals were exceedingly rare.

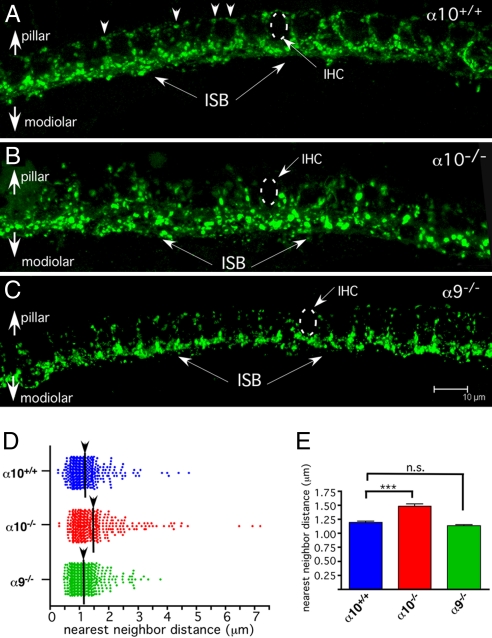

In wild-type mice, the inner spiral bundle contains efferent fibers synapsing with cochlear nerve dendrites in the region below and surrounding the IHCs. Most immunostained terminals are found on the modiolar side of the IHC (closer to the nerve trunk), but a lesser number of smaller and less brightly stained efferent boutons are found on the pillar side of the IHCs as well (Fig. 5A, arrowheads). The synaptophysin-stained inner spiral bundle of α10−/− mice appeared disorganized. Modiolar-side terminals were larger in α10−/− mice than in wild type, and there was a paucity of terminals on the pillar side of the hair cell (Fig. 5B). The degree of disorganization was quantified via a nearest-neighbor distance analysis of 388 terminals in α10−/− mice and 425 terminals in α10+/+ mice (Fig. 5 D and E). The mean distance between terminals was larger in α10−/− mice compared with α10+/+ mice (1.48 μm ± 0.04 vs. 1.19 μm ± 0.03 μm, Fig. 5D; unpaired two-tailed t test, P = 6.7 × 10−7). The maximal spread of the nearest-neighbor distance in α10−/− mice was increased by ≈50% over that of wild type (7 μm vs. 4.7 μm), and the number of terminals with nearest neighbors between 1.7 and 4.7 μm (the bulk of the terminals above the mean of the α10−/− mice) was larger in α10−/− mice (n = 81) compared with α10+/+ mice (n = 49). A similar examination of the α9−/− mice (656 terminals counted over a similar region as above) revealed no statistically significant difference in nearest-neighbor distance with the wild-type mice [1.19 μm ± 0.03 (WT) vs. 1.13 μm ± 0.02 (KO); Fig. 5 C–E].

Fig. 5.

Whole-mount cochlear turns demonstrating the inner spiral bundle (IHC region) immunostained with antibody to synaptophysin. (A) α10+/+ mice exhibit a regular progression of efferent terminals along the “bottom” (modiolar side) of the IHCs (ISB; arrows). These boutons are larger and more intensely stained than those on the pillar side of the IHC (arrowheads). As a group of terminals, the efferent system tends to outline the row of IHCs. (B) α10−/− mice exhibit a disorganized inner spiral bundle (ISB; arrows). The boutons tend to be large and stain very brightly. Additionally, there is little pillar-side innervation to the IHCs. (C) α9−/− mice were reexamined to compare the effects of nAChR subunit gene deletion. As previously reported, fewer pillar side terminals are evident in the α9−/− ISB, but the modiolar-side terminal field appears similar in organization to the wild-type ISB in A. Dotted circles indicate the position of the IHCs. (Scale bar is same for A–C, 10 μm) (D) Scatter plot of the distance between the nearest neighbor of each terminal in the field of view. The greater scatter of the ISB terminals in the α10−/− is evident in the greater number of terminals separated by >1.5 μm. (E) A bar graph of the mean and SEM further illustrates the change in innervation between the α10−/−and α10+/+ mice and lack of effect in α9−/− mice. Two-tailed, unpaired t test. ***, P = 6.7 × 10−7. n.s., not significant.

Discussion

Our data illustrate that the α10−/− phenotype is distinct from that observed in the α9−/− mouse line in terms of hair cell physiological function and synaptic structure. In addition, our data demonstrate that the residual functional α9 nAChRs expressed in α10−/− mice are insufficient to drive normal OC efferent function. Thus, our data definitively establish the requirement for α10 subunits in forming biologically relevant hair cell nAChRs.

Homomeric α9 nAChRs reconstituted in Xenopus oocytes produce small ACh-evoked currents (25). The presence of small ACh-evoked currents in some α10−/− OHCs suggests the continued expression of functional α9 receptors that likely consist of homomeric subunits. Lack of nicotine-induced activation in OHCs that are otherwise ACh-responsive is consistent with the presence of α9 homomeric receptors. Moreover, the fact that OHCs from α9−/− mice do not present ACh-evoked currents rules out the possibility that in the absence of functional α9α10 nAChRs, small residual muscarinic currents could be disclosed. Because both α9 homomeric and α9α10 heteromeric receptors have a high Ca2+ permeability (35, 36), one might expect coupling of α9 nAChRs to an SK2 channel in OHCs of the α10−/− mice. The fact that outward currents were observed in OHCs of α10−/− mice at −40 mV suggests coupling to a potassium channel. It is well recognized that nAChRs are coupled to SK2 channels in wild-type hair cells (9–11, 13–17, 28), and we show here that α10−/− mice express normal levels of SK2 transcripts. Thus, it seems reasonable to propose SK2 channels as the source of the potassium current. The fact that no synaptic currents were observed in OHCs of the α10−/− mice suggests that either α9 homomeric receptors are extrasynaptic, or that currents are simply too small to detect, perhaps owing to less efficient insertion into the membrane.

Our inability to detect ACh-evoked responses in IHCs of α10−/− mice is consistent with the observation that loss of α10 (but not α9) transcripts after the onset of hearing is correlated with the absence of functional ACh receptors in IHCs of wild-type mice (9, 21). This natural loss of ACh-inducible response reinforces the interpretation of the experimental data that α10 is a key component of functional nAChRs present in IHCs (9, 28) and suggests either that the number of homomeric α9 receptors is too small to generate detectable currents, or that in IHCs, a population of homomeric α9 receptors is not assembled or inserted into the membrane.

As reported for α9−/− mice (7), loss of α10 has no effect on cochlear baseline sensitivity. This loss is not unexpected given that there is no sound-evoked activity in the OC fibers at threshold levels and little spontaneous activity (37). The mammalian olivocochlear system constitutes a sound-evoked reflex pathway that is excited by sound in either ear (38, 39). Electric activation of the OC system evokes a fast-onset decrease in cochlear sensitivity, as measured either via afferent responses (5, 7, 40), hair cell receptor potentials (41, 42), DPOAEs (43, 44), or basilar membrane motion (18). The fact that no fast-onset DPOAE suppression was observed in the α10−/− mice indicates that calcium currents through residual α9 nAChRs are not sufficient to drive normal OC activity. Enhancement of DPOAEs (as seen in both α9−/− and α10−/− mice) suggests that this phenomenon is a normal part of the OC response whose initial activity has been unmasked by the loss of the normal, suppressive cholinergic activity. The molecular mechanism generating the enhancement remains to be determined but is clearly not generated by α9α10-containing nAChRs. It is likely that additional mechanisms will need to be explored, given that OC terminals also express GABA and CGRP, and that ACh can also activate OHCs via muscarinic cholinergic receptors (for a more complete discussion of these alternatives, see ref. 34).

We previously reported changes in OC innervation to OHCs in the α9−/− mouse (7). The dysmorphology of efferent innervation in the α10−/− mice suggests that the α10 subunit also plays a significant role in either the development or homeostatic maintenance of synaptic connections between efferent fibers and their cochlear targets, and, furthermore, that any residual ACh-evoked activity from activation of α9 homomeric receptors is not sufficient to drive a normal efferent synaptogenesis/maintenance program. However, the observed synaptic abnormalities observed in α10−/− mice differ from that of the α9−/− mice, possibly because of residual α9 nAChR activity in α10−/− mice. Indeed, whereas OHC terminals of the α9−/− and α10−/− mouse lines are both hypertrophied and abnormal in their number, α10−/− mice show a greater number of boutons contacting individual OHCs than do the α9−/− mice.

Comparing the disorganized efferent innervation to the IHC region of α10−/− mice with the more regular pattern of innervation in wild-type and α9−/− mice suggests that loss of the α10 gene is more detrimental to synapse formation than elimination of the α9 gene, which we have shown completely silences the cholinergic synapse (ref. 7 and present results). It is unknown whether homomeric α9 nAChRs are active in IHCs of α10−/− mice (albeit abnormally) during very early postnatal stages or embryonic development. If this is the case, such activity may result in a different response to ACh-induced activity compared with when the nAChR complex is fully silenced. Responses could indicate either a subtle change in activity that is lost before our date of examination by electrophysiology (P8), or that the hair cell nAChRs play a structural or metabolic role in synapse formation within the IHC region not previously appreciated.

Our data indicate that, although tempting to view α10 as a “modulatory” subunit given the homomeric α9 responses elicited in heterologous expression systems (21, 25), α10 is in fact absolutely necessary for proper nAChR activity induced by olivocochlear neurotransmission. It is thus possible to speculate that α10 has evolved to serve a special role in mammalian audition. From the present results, it is clear that although functional, homomeric α9 nAChRs are insufficient either in number or activity to suppress DPOAE amplitudes, and that the inner ear requires α9α10 nAChRs to permit CNS modulation of cochlear mechanics, thereby invoking the physiological roles of the OC system (e.g., protection from moderate noise-induced trauma, establishing attention to specific signals, etc.). An evolutionarily diverged α10 subunit capable of assembling with α9 and conveying new properties to the nAChR is therefore apparently required to obtain classical OC efferent effects. Our results complement previous phylogenetic and evolutionary analysis (45) of the α10 subunit indicating that α10 has likely evolved to give the auditory system a feedback control capability over the coevolved somatic electromotility (2, 46) that is not required in nonmammalian species.

Experimental Procedures

Genetic Engineering and Genotyping of α10 Null-Mutant Mice.

Standard procedures were used to generate the Chrna10 null-mutant mouse line (SI Fig. 8). The Chrna10 null-mutant allele has been backcrossed (n ≥ 5) and maintained in homozygous congenic B6.CAST-ahl+ mice (stock number 002756; Jackson Laboratory). All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as well as University of California (Los Angeles, CA), Tufts University, and Mass Eye and Ear Infirmary Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Quantitative PCR.

SYBR Green-based quantitative RT-PCR was used to assess gene-expression levels of various genes previously shown to be involved in OC function or general hair cell physiology (SI Table 1). Gene-specific DNA primers were purchased from Qiagen QuantiTect Primer assays library.

Electrophysiological Recordings from Hair Cells.

After killing the mice, apical turns of the organ of Corti were excised from α10+/+, α10+/−, α10−/−, and α9−/− mice at P8–9 for IHCs and P10–13 for OHCs. These ages were chosen because they are the times at which maximal ACh-inducible activity is observed in the different hair cell populations. Methods to record from IHCs and OHCs were as described in refs. 9, 28, and 47. Recordings were made at room temperature (22–25°C). Holding potentials were not corrected for liquid junction potentials (−4mV) or the voltage drop across the uncompensated series resistance (9–12 MΩ). All experimental results obtained in IHCs and OHCs are from two to eight mice of each phenotype.

Cochlear Physiology.

Procedures were as described in ref. 34. For recording DPOAEs, animals were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine. Primary tones f1 and f2 (with f2/f1 = 1.2 and f2 level 10 dB < f1 level) were presented continuously. The ear-canal sound pressure waveform was amplified (×1,000) and averaged (8 or 25 consecutive waveform traces), and spectrum was computed by fast Fourier transform. The process was repeated either two or four times, the resultant spectra averaged, and 2f1–f2 DPOAE amplitude and surrounding noise floor (six bins on each side of the DP) were extracted.

ABRs were obtained as described in ref. 7. For OC shock experiments, animals were anesthetized with urethane (1.20 g/kg i.p.) and surgically prepared as described in refs. 7 and 34. During the OC suppression assay, f2 level was typically set to produce a DPOAE ≈10–15 dB above noise floor. To measure OC effects, repeated measures of baseline DPOAE amplitude were first obtained (n = 12), followed by a series of 17 continuous periods in which DPOAE amplitudes were measured with simultaneous shocks to the OC bundle in the floor of the fourth ventricle.

Immunostaining and Image Processing.

Cochleas were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h and decalcified overnight in 8% EDTA buffered in 1xPBS. Adult 2- to 4-month-old mice were used for all analyses. Efferent terminals were visualized by using a mouse anti-synaptophysin antibody (MAB5258; Millipore). Sections were slide mounted and cover slipped with SlowFade Gold (Invitrogen). Samples were examined by using a Leica TCS SP2 AOBS confocal microscope. For analysis of innervation density in the IHC region, merged Z stacks of the inner spiral bundle were imported to ImageJ, and terminals were manually selected and mapped as points by using the ImageJ plug-in, point-picker (see http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). The resultant point distribution map was then imported into R (see www.R-project.org), and nearest-neighbor distance was calculated by using the SpatStat module (48) of R. A two-tailed unpaired t test was performed on the nearest-neighbor distances, and a scattergram plot was generated to illustrate minimum, mean, and maximum neighbor distances for each synaptic terminal. The mean nearest-neighbor distance was also graphed as a bar graph with SEMs. All statistical analyses were performed in Prism (v. 4.0b).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DC6258 (to D.E.V.), R01 DC0188 (to M.C.L.), R21 NS050419 (to J.B.), and P30 DC 05209 (to M.C.L.), a Smith Family New Investigator Award (to D.E.V.), an International Research Scholar Grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to A.B.E.), a research grant from Agencia Nacional de Promoción Cientifica y Técnia and Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina (to A.B.E.), and a grant to The Tufts Center for Neuroscience Research (P30 NS047243) supporting the Imaging and Computational Genomics Cores.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0708545105/DC1.

References

- 1.Hudspeth A. Neuron. 1997;19:947–950. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brownell WE, Bader CR, Bertrand D, de Ribaupierre Y. Science. 1985;227:194–196. doi: 10.1126/science.3966153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dallos P. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4575–4585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-12-04575.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasmussen GL. Anat Rec. 1942;82:441. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desmedt JE, Lagrutta V. Nature. 1963;200:472–474. doi: 10.1038/200472b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh E, McGee J, McFadden S, Liberman M. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3859–3869. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03859.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vetter DE, Liberman MC, Mann J, Barhanin J, Boulter J, Brown MC, Saffiote-Kolman J, Heinemann SF, Elgoyhen AB. Neuron. 1999;23:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80756-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eybalin M. Physiol Rev. 1993;73:309–373. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz E, Elgoyhen A, Gómez-Casati M, Knipper M, Vetter D, Fuchs P, Glowatzki E. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7814–7820. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2102-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuchs P, Murrow B. J Neurosci. 1992;12:800–809. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-00800.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanchet C, Eróstegui C, Sugasawa M, Dulon D. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2574–2584. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02574.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dulon D, Lenoir M. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:1945–1952. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans MG. J Physiol (London) 1996;491(Pt 2):563–578. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nenov AP, Norris C, Bobbin RP. Hear Res. 1996;101:149–172. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(96)00143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dulon D, Luo L, Zhang C, Ryan A. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:907–915. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliver D, Klöcker N, Schuck J, Baukrowitz T, Ruppersberg J, Fakler B. Neuron. 2000;26:595–601. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glowatzki E, Fuchs P. Science. 2000;288:2366–2368. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murugasu E, Russell IJ. J Neurosci. 1996;16:325–332. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00325.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lustig L, Peng H, Hiel H, Yamamoto T, Fuchs P. Genomics. 2001;73:272–283. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luebke AE, Maroni PD, Guth SM, Lysakowski A. J Comp Neurol. 2005;492:323–333. doi: 10.1002/cne.20739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elgoyhen A, Vetter D, Katz E, Rothlin C, Heinemann S, Boulter J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3501–3506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051622798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nie L, Song H, Chen M, Chiamvimonvat N, Beisel K, Yamoah E, Vázquez A. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:1536–1544. doi: 10.1152/jn.00630.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sgard F, Charpantier E, Bertrand S, Walker N, Caput D, Graham D, Bertrand D, Besnard F. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:150–159. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maison S, Luebke A, Liberman M, Zuo J. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10838–10846. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10838.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elgoyhen AB, Johnson DS, Boulter J, Vetter DE, Heinemann S. Cell. 1994;79:705–715. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90555-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo L, Bennett T, Jung H, Ryan A. J Comp Neurol. 1998;393:320–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morley B, Simmons D. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;139:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00514-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gómez-Casati M, Fuchs P, Elgoyhen A, Katz E. J Physiol (London) 2005;566:103–118. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hashimoto S, Kimura RS, Takasaka T. Acta Otolaryngol. 1990;109:228–234. doi: 10.3109/00016489009107438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sobkowicz HM. In: Development of Auditory Systems 2. Romand R, editor. New York: Elsevier; 1992. pp. 59–100. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verbitsky M, Rothlin C, Katz E, Elgoyhen A. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:2515–2524. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothlin CV, Katz E, Verbitsky M, Elgoyhen AB. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55:248–254. doi: 10.1124/mol.55.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maison S, Adams J, Liberman M. J Comp Neurol. 2003;455:406–416. doi: 10.1002/cne.10490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maison S, Vetter D, Liberman M. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:3269–3278. doi: 10.1152/jn.00067.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katz E, Verbitsky M, Rothlin CV, Vetter DE, Heinemann SF, Elgoyhen AB. Hear Res. 2000;141:117–128. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weisstaub N, Vetter D, Elgoyhen A, Katz E. Hear Res. 2002;167:122–135. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00380-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liberman M, Brown M. Hear Res. 1986;24:17–36. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(86)90003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Folsom RC, Owsley RM. Acta Otolaryngol. 1987;103:262–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liberman MC. Hear Res. 1989;38:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(89)90127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galambos R. J Neurophysiol. 1956;19:424–437. doi: 10.1152/jn.1956.19.5.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown MC, Nuttall AL, Masta RI. Science. 1983;222:69–72. doi: 10.1126/science.6623058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown MC, Nuttall AL. J Physiol (London) 1984;354:625–646. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mountain DC. Science. 1980;210:71–72. doi: 10.1126/science.7414321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siegel JH, Kim DO. Hear Res. 1982;6:171–182. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(82)90052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franchini LF, Elgoyhen AB. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;41:622–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brownell WE. Scanning Electron Microsc. 1984:1401–1406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lioudyno M, Hiel H, Kong J, Katz E, Waldman E, Parameshwaran-Iyer S, Glowatzki E, Fuchs P. J Neurosci. 2004;24:11160–11164. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3674-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baddeley A, Turner R. J Stat Software. 2005;12:1–42. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.