Tobacco taxation is a key mechanism for reducing smoking consumption and prevalence in the general population. Few studies, however, have acknowledged the disproportionately heavy tobacco tax burden placed upon some groups—usually poor, marginalized populations—in the drive for population-based public health goals.1 Shelley et al.2 recently examined the relations between a large tax increase in New York State and the development of a pervasive, illicit cigarette market in a low-income minority community and described the financial burden of smoking among the poor who had not quit. Our letter extends these qualitative findings in 2 ways: by examining similar issues in a different marginalized, low-income population—psychiatric patients in one of Canada’s largest psychiatric hospitals—and by quantifying the relative magnitude of illicit cigarette consumption in this population.

Approximately 60% to 80% of people with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses smoke cigarettes3,4—a rate of roughly 4 times higher than that of the general population in Canada.5 Smoking plays an important role in the significantly higher rates of coronary heart disease morbidity and mortality found among people with severe mental illnesses, and coronary heart disease screening and smoking-cessation programs are much needed for this population.6

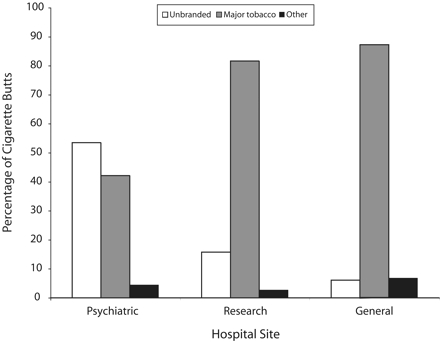

Our study involved the collection of cigarette butts from 3 sites in Toronto, Ontario: a 436-bed inpatient psychiatric hospital (where 70–75% of the patients have a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia), an addiction and mental health research and outpatient facility, and a large general hospital. In addition, a garbage audit was performed at the inpatient psychiatric facility to extract cigarette packages from 1 week’s worth of garbage. The collected cigarette butts were then sorted according to their filter-tip logos. In Ontario, an unbranded cigarette filter almost always indicates an illicit brand. The inpatient psychiatric hospital had a dramatically higher rate of “unbranded” cigarette butts: 54% versus 16% at the research facility and 6% at the general hospital site (Figure 1 ▶). The garbage audit resulted in the extraction of 320 cigarette packages. Approximately 80% of the packages were from illicit tobacco brands—a rate dramatically higher than that found in a recent, city-wide garbage audit in Toronto.7

FIGURE 1—

Patterns of branding on cigarette butts collected at an inpatient psychiatric hospital (n = 1288 butts), an addiction and mental health research and outpatient treatment facility (n = 1271 butts), and a general hospital (n = 1784 butts).

Similar to the findings of Shelley et al., our study demonstrated that cigarette taxation policies appear to place a disproportionate burden on some marginalized groups. As a result, it is important to assess and ensure principles of taxation equity for such populations,8 especially given that higher cigarette prices may paradoxically increase the availability of cheap (but illicit) cigarettes and undermine smoking-related interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Strategic Training Fellowship in Tobacco Use in Special Populations awarded to R.C. Callaghan.

Without the support and hard work of the housekeeping and grounds staff at the hospital sites, this study would not have been possible. In particular, we thank Joe Camarata, Joe Cordeiro, Manny Branco, Frank Wazette, and Blaine McEwan.

Human Participant Protection The research ethics office at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health concluded that ethical approval was not required because the study did not involve research on human participants.

Contributors R. C. Callaghan originated and supervised the study. J. Tavares conducted the analyses and assisted with the preparation of the letter. L. Taylor assisted with the study and also helped to prepare the letter.

References

- 1.Wilson N, Thomson G. Tobacco taxation and public health: ethical problems, policy responses. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shelley D, Cantrell J, Moon-Howard J, Ramjohn DQ, VanDevanter N. The $5 man: the underground economic response to a large cigarette tax increase in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1483–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dixon L, Medoff DR, Wohlheiter k, et al. Correlates of severity of smoking among persons with severe mental illness. Am J Addict. 2007;16:101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Leon J, Diaz FJ. A meta-analysis of worldwide studies demonstrates an association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking behaviors. Schizophr Res. 2005;76:135–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Statistics Canada. Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey, February–June 2006. Ottawa, Ont: Health Canada. 2007.

- 6.Osborn DPJ, Levy G, Nazareth I, et al. Relative risk of cardiovascular and cancer mortality in people with severe mental illness from the United Kingdom’s general practice research database. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MGM Management. The City of Toronto: Streets Litter Audit 2006. Toronto, Ont: City of Toronto, Solid Waste Management Services Division; 2006.

- 8.Remler DK. Poor smokers, poor quitters, and cigarette tax regressivity. Am J Public Health. 2004;94: 225–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]