Abstract

The 64-kD protein DAip1 from Dictyostelium contains nine WD40-repeats and is homologous to the actin-interacting protein 1, Aip1p, from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and to related proteins from Caenorhabditis, Physarum, and higher eukaryotes.

We show that DAip1 is localized to dynamic regions of the cell cortex that are enriched in filamentous actin: phagocytic cups, macropinosomes, lamellipodia, and other pseudopodia. In cells expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged DAip1, the protein rapidly redistributes into newly formed cortical protrusions.

Functions of DAip1 in vivo were assessed using null mutants generated by gene replacement, and by overexpressing DAip1. DAip1-null cells are impaired in growth and their rates of fluid-phase uptake, phagocytosis, and movement are reduced in comparison to wild-type rates. Cytokinesis is prolonged in DAip1-null cells and they tend to become multinucleate. On the basis of similar results obtained by DAip1 overexpression and effects of latrunculin-A treatment, we propose a function for DAip1 in the control of actin depolymerization in vivo, probably through interaction with cofilin. Our data suggest that DAip1 plays an important regulatory role in the rapid remodeling of the cortical actin meshwork.

Keywords: actin, Dictyostelium discoideum, endocytosis, motility, WD-repeat

The actin cytoskeleton is involved in cell locomotion, cytokinesis, cell-cell and cell-substratum interactions, the organization of the cytosol, vesicle and organelle transport, and the establishment and maintenance of cellular morphology. The organization of F-actin in different cytoskeletal structures is controlled by accessory proteins, some of which facilitate the assembly of actin filaments into a three-dimensional meshwork, whereas others regulate filament turnover or remodel the actin cytoskeleton in response to external signals.

Cytoskeletal fractions from Dictyostelium cells contain myosin II, actin, and actin-binding proteins such as α-actinin, ABP120, fimbrin, cortexillin, and coronin (Fechheimer and Taylor 1984; de Hostos et al. 1991; Faix et al. 1996; Prassler et al. 1997). One of these proteins, coronin (de Hostos et al. 1991), turned out to be the prototype of a class of WD-repeat proteins (Neer et al. 1994). Coronin homologues have been identified in yeast, Physarum polycephalum, Caenorhabditis elegans, sea urchin, mice, and humans (Suzuki et al. 1995; Grogan et al. 1997; Terasaki et al. 1997; Heil-Chapdelaine et al. 1998; Okumura et al. 1998). It has been shown repeatedly that coronin interacts with components of the actin cytoskeleton (de Hostos et al. 1991; David et al. 1998; Goode et al. 1999). In Dictyostelium, coronin accumulates at the leading edges of migrating cells (de Hostos et al. 1991; Gerisch et al. 1995), in phagocytic cups (Maniak et al. 1995), and in crown-shaped extensions on the dorsal cell surface (de Hostos et al. 1991), which are the sites of fluid-phase uptake (Hacker et al. 1997). Analysis of coronin-null mutants established a role of coronin in cell locomotion, cytokinesis, phagocytosis, and macropinocytosis (de Hostos et al. 1993; Maniak et al. 1995; Hacker et al. 1997).

Here we describe a new 64-kD protein from Dictyostelium that coprecipitates with actin-myosin complexes. Like coronin, this protein is a WD40-repeat protein. Therefore, its sequence has been indexed as WD-repeat protein 2 (Wdp2) in the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ databases (accession number U36936). We refer now to this protein as Dictyostelium Aip1 (DAip1), because it became evident that Wdp2 is the Dictyostelium homologue of the actin-interacting protein 1 (Aip1p) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The yeast protein has been discovered in a two-hybrid screen for proteins that interact with actin (Amberg et al. 1995). Recent entries in the protein sequence databases indicate that Aip1-like proteins are ubiquitously represented in eukaryotic cells.

DAip1 is strongly accumulated in dynamic regions of the cell cortex, in particular crowns and leading edges, as shown by monitoring the localization of a green fluorescent protein (GFP)1-tagged DAip1 fusion protein. Mutants lacking DAip1 are severely impaired in endocytosis and motility, and have a moderate cytokinesis defect. Our results provide in vivo evidence that proteins of this type play a role in the control of complex processes that are based on the turnover of actin.

Materials and Methods

Growth and Development of Dictyostelium Cells

Dictyostelium discoideum cells of the wild-type strain AX2, and DAip1-null and HG1569 coronin-null cells were cultivated in nutrient medium (Watts and Ashworth 1970) at 23°C, either in shaken suspension at 150 rpm (Claviez et al. 1982), or submerged on petri dishes. To induce starvation, cells were washed twice in 17 mM K-Na-phosphate buffer, pH 6.0 (nonnutrient buffer), and were shaken at a density of 107 cells/ml in the buffer. For cultivation on agar surfaces, Klebsiella aerogenes bacteria were spread on agar plates and AX2 or DAip1-null cells were inoculated onto the surface with a toothpick.

cDNA Cloning and Sequence Analysis

A partial clone of DAip1 was isolated from a λgt11 cDNA library of D. discoideum strain AX3 (Clontech Inc.). The sequence was completed in both directions using a PCR-based strategy using DAip1 and λgt11 sequence-specific primers and the cDNA library as template. DNA was sequenced on an Applied Biosystems sequencer ABI PrismTM 377 (Toplab). Sequences were analyzed using the UWGCG (Devereux et al. 1984) and EGCG software, as well as the MIPS and EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ databases.

Protein Purification, mAbs, and Immunoblotting

The contracted actin-myosin complex was prepared from AX2 cells starved for 14 h essentially as described previously (Fechheimer and Taylor 1984; de Hostos et al. 1991), except that 1 mM ATP, 20 mM KCl, and 5 mM MgCl2 were added subsequently for complex formation.

A cDNA fragment encompassing the entire coding region of DAip1 beginning with Ser-2 was amplified by PCR using primers designed to obtain a BamHI site at the 5′ end and a HindIII site at the 3′ end. The product was cloned into the expression vector pQE-30 (Qiagen Inc.), and the His-tagged protein was expressed in Escherichia coli M15. The recombinant protein was purified on a Ni2+-NTA-agarose column (Qiagen) to homogeneity using denaturing conditions (8 M urea, 0.1 M NaH2PO4, 0.01 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0).

Antibodies were obtained by immunizing BALB/c mice with recombinant DAip1 using either aluminum hydroxide or Freund's adjuvant. Spleen cells were fused with PAIB3Ag8 myeloma cells. mAbs 245-308-1, 246-466-6, 246-258-1, and 246-153-2 that specifically recognized DAip1 were used in this study. For detection of coronin, mAb 176-3-6 (de Hostos et al. 1991) was employed. Immunoblotting with diluted culture supernatants of anti-DAip1 or anti-coronin hybridoma cell lines was performed after SDS-PAGE in 10% gels. Phosphatase-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.) or iodinated sheep anti–mouse IgG (Amersham International) was used to visualize primary antibodies.

Gene Replacement in Dictyostelium

For construction of the DAip1 targeting vector, 5′ and 3′ fragments of the DAip1 sequence were generated by PCR using the primers 5′-GTGAAGCTTGAATTCAACACCAGCAACTACTCGTG-3′ and 5′-GTGAAGCTTACCATCATAAACAAAGGCTTTC-3′ for the 5′ fragment, and 5′-GTGTCTAGAAGCCCAACAACATACTGGTGG-3′ and 5′-GTGGAATTCACCTTCATTACCTGCAGAG-3′ for the 3′ fragment. The 3′ fragment was cleaved by XbaI and EcoRI and the 5′ fragment by HindIII, and both fragments were cloned subsequently into the plasmid pBsr2 (Sutoh 1993), thus flanking the blasticidin cassette. The construct was excised using EcoRI and PstI. After dephosphorylation, the fragment was used for calcium phosphate–mediated transformation of AX2 wild-type cells. DAip1-null cells were selected with 10 μg/ml blasticidin S (ICN Biomedicals Inc.) in nutrient medium and identified by the colony blot technique (Wallraff and Gerisch 1991), using mAbs 246-258-1 and 246-153-2.

Southern blotting was performed as described (Kreitmeier et al. 1995). The blots were hybridized under high stringency conditions for 4 h at 65°C in RapidHyb buffer (Amersham), with a PCR-generated probe comprising base pairs 1577–1791 of the DAip1 coding sequence, and washed with a buffer containing 50% formamide.

Expression of DAip1-GFP and GFP-Actin Constructs, and Overexpression of DAip1

Mutants expressing a DAip1-GFP fusion protein were produced by transformation of wild-type and DAip1-null cells with a vector conferring resistance to G418 essentially as described (Gerisch et al. 1995), but carrying the sequence for GFP-S65T (Heim and Tsien 1996). GFP was fused either to the NH2 terminus or to the COOH terminus of DAip1, generating GFP-(N)-DAip1 or DAip1-(C)-GFP, respectively.

For constructing the expression vector for GFP-(N)-DAip1, a PCR fragment was generated using the primers 5′-GTGAATTCAAAATGTCTGTAACTTTAAAAAATATT-3′ and 5′-GTGGAATTCTTAATTTGATACATACCAAATTTTAATAG-3′, and a Dictyostelium cDNA library in λgt11 (Clontech) as template. The fragment was cleaved with EcoRI, and cloned into the EcoRI site of pDEX gfp (Westphal et al. 1997) to express GFP-(N)-DAip1 under control of an actin-15 promoter in DAip1-null cells. The same fragment was ligated into pDEX RH (Faix et al. 1992) in an attempt to rescue DAip1-null cells by expression of DAip1. For DAip1-(C)-GFP, a PCR fragment was amplified by using the primers 5′-GTGGATATCATGTCTGTAACTTTAAAAAATATTATTG-3′ and 5′-GTGAGCTCTTGATACATACCAAATTTTAATAGCAC-3′, linked to the complete coding region of GFP, and cloned into the EcoRI site of pDEX RH.

For expression of GFP-actin, DAip1-null cells were transformed with the same vector that has been used previously for the expression and analysis of GFP-actin in wild-type cells (Westphal et al. 1997).

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

AX2 wild-type or mutant cells were allowed to settle onto glass coverslips for 30 min, fixed with picric acid/formaldehyde for 20 min, and postfixed with 70% ethanol as described (Jungbluth et al. 1994). Subsequently, they were processed for immunolabeling according to Humbel and Biegelmann 1992. DAip1 was detected with mAbs 246-466-6 or 246-153-2, and Cy2-conjugated (BioTrend Chemicals) or TRITC-conjugated (Jackson ImmunoResearch) goat anti–mouse IgG. F-Actin was labeled with TRITC-conjugated phalloidin (Sigma Chemical Co.). Cofilin was detected with a 1:100 dilution of an anti-cofilin antiserum kindly provided by Dr. H. Aizawa (Tokyo, Japan), and Cy3-conjugated goat anti–rabbit IgG (BioTrend). For conventional immunofluorescence microscopy, images were either taken using an Axiophot 1 microscope (Zeiss), or by a cooled CCD camera (SensiCam; PCO Computer Optics) using an Axiophot 2 microscope (Zeiss) equipped with a 100×/1.3 Neofluar objective. Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy was performed with a Zeiss laser-scanning microscope (LSM 410) equipped with a 100×/1.3 Plan-Neofluar objective. For three-dimensional image reconstructions, AVS software (Advanced Visual Systems) was used as described (Neujahr et al. 1997b).

In Vivo Microscopy

For observing the morphology of dividing cells, a double-view microscope was used, which combines phase-contrast and RICM imaging (Weber et al. 1995). For studying the localization of GFP-(N)-DAip1 fusion protein during cell locomotion, chemotaxis, cytokinesis, phagocytosis, and pinocytosis, a Zeiss LSM 410 equipped with a 100×/1.3 Plan-Neofluar objective was used. The 488-nm band of an argon-ion laser was used for excitation, and a 515–565-nm band-pass filter was used for emission. Cells were cultivated in nutrient medium on polystyrene culture dishes, washed in nonnutrient buffer, and transferred onto a glass surface. Before investigation of cytokinesis, cells were incubated with a suspension of K. aerogenes in nonnutrient buffer for at least 2 h (Weber et al. 1999b). For phagocytosis, cells were incubated with a suspension of heat-killed cells of the yeast S. cerevisiae in nonnutrient buffer for 20 min (Maniak et al. 1995). Chemotactic responses were recorded from cells stimulated with a micropipette filled with a solution of 10−4 M cAMP (Gerisch and Keller 1981).

Motility and Endocytosis Assays

Quantitative analysis of cell motility was performed according to the method of Fisher et al. 1989, using a Zeiss IM 35 inverted microscope and an image-processing system (OFG Imaging Technology). Motility of growth-phase cells was measured in nutrient medium on glass coverslips. In a single experiment, a field containing ∼50 cells was monitored, and cell positions were recorded for 30 min every 45 s. Results from six or seven experiments for each strain were pooled.

Phagocytosis assays using TRITC-labeled, heat-killed yeast in shaken suspension were carried out essentially as described by Maniak et al. 1995. Quantitative and microscopic assays of fluid-phase uptake were performed using TRITC-labeled dextran (Sigma Chemical Co.) according to Hacker et al. 1997. The results from quantitative endocytosis assays of wild-type and mutant cells (see Fig. 5 and Fig. 6) were corrected based on the determination of protein content (Maniak et al. 1995). For the experiment shown in Fig. 7, latrunculin-A (Lat-A; Molecular Probes) was added to the cells just before addition of fluid-phase or particle markers at the 0-min time point.

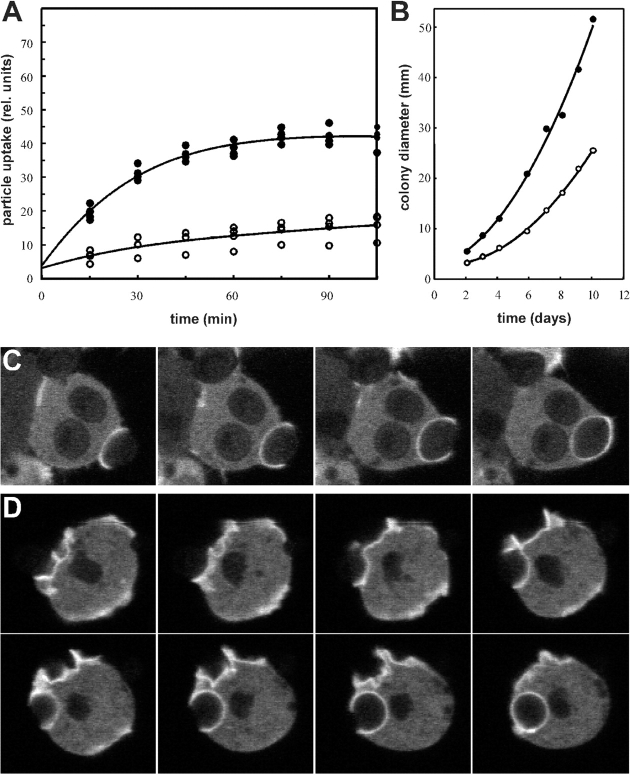

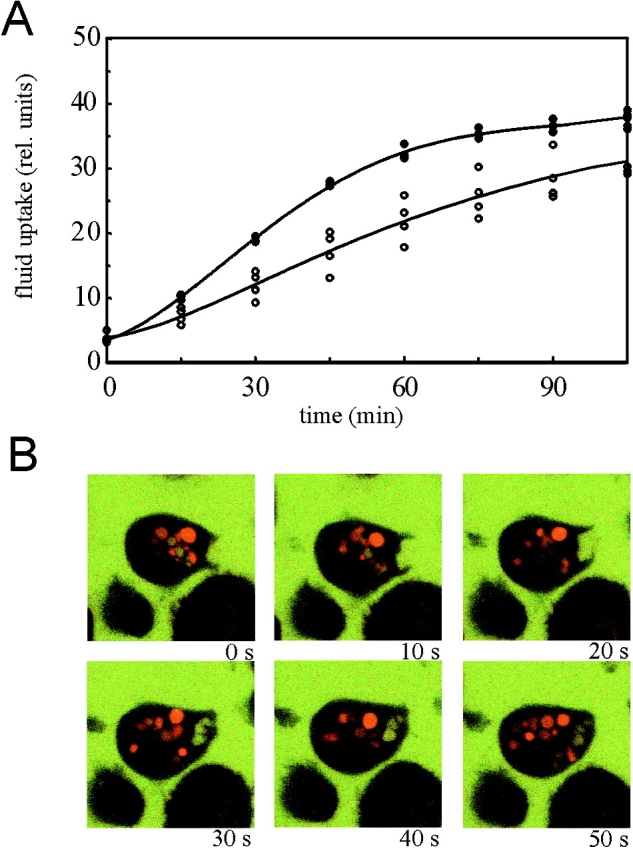

Figure 5.

Reduced fluid-phase uptake in DAip1-null mutant cells. (A) Endocytosis of TRITC-dextran was measured in AX2 wild-type cells (filled circles) and DAip1-null mutant cells (open circles). The data from four independent experiments were averaged to calculate the curves. (B) Confocal sections through single DAip1-null cells undergoing macropinocytosis. To distinguish older, acidified endosomes (red) from freshly formed macropinosomes (yellow), cells were incubated with a mixture of FITC-labeled and TRITC-labeled dextrans as described (Maniak 1999). Time points are in seconds.

Figure 6.

Reduced growth and phagocytosis rate of DAip1-null cells. (A) Uptake of TRITC-labeled yeast particles was determined in AX2 wild-type (filled circles) and in DAip1-null cells (open circles). The data from three independent experiments were averaged to calculate the curves. (B) Growth of AX2 wild-type (filled circles) and of DAip1-null mutant (open circles), on a lawn of K. aerogenes. For each time point, the diameter of 10 colonies was measured and averaged. (C and D) Monitoring of phagocytic cup formation from attachment until the complete engulfment of a yeast particle in wild-type (C), and DAip1-null cells (D), expressing actin-GFP. Images in C and D were taken in 10-s intervals.

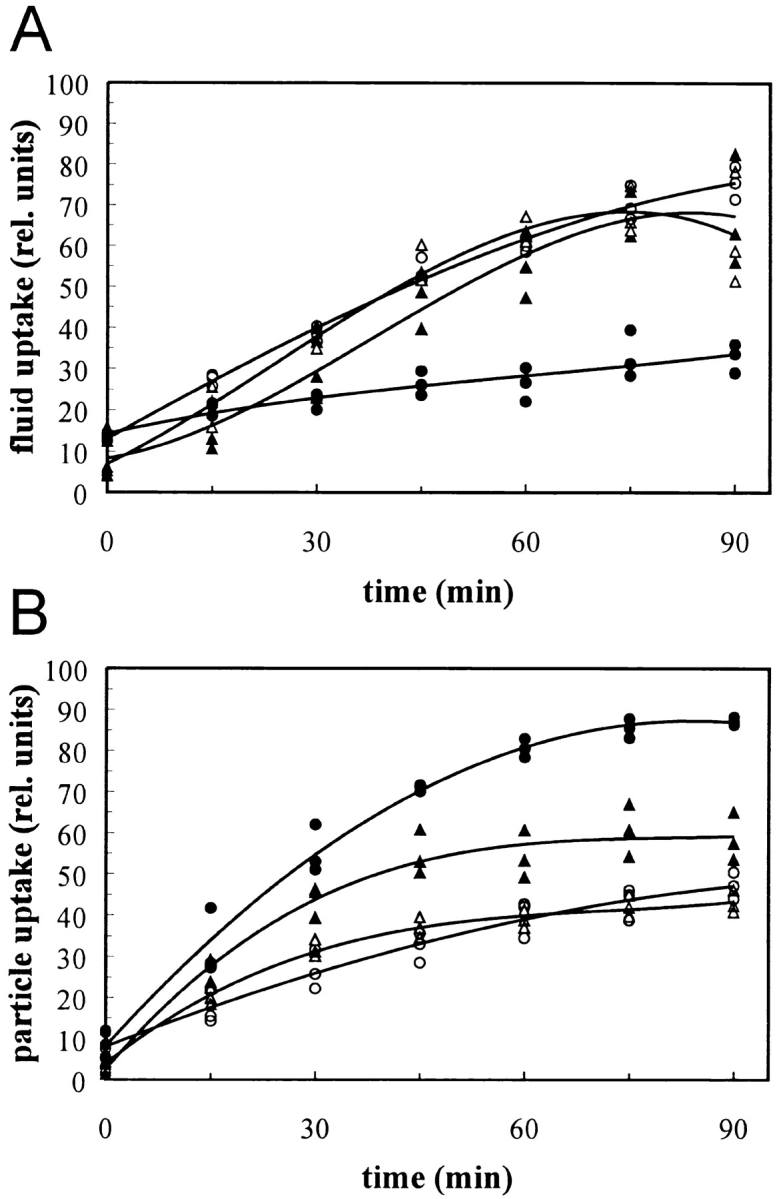

Figure 7.

Effects of Lat-A and of DAip1 overexpression on fluid-phase and particle uptake. (A) Fluid-phase uptake of TRITC-dextran was first determined in the AX2 wild-type (open triangles), and in DAip1-overexpressing cells (filled triangles). Fluid-phase uptake was independently determined for AX2 cells treated with a representative concentration of 0.3 μM Lat-A (filled circles) and an untreated control (open circles). The curves were plotted into a single graph to obtain maximal overlap between the wild-type data and the untreated control (open symbols). The data from three independent experiments were used to calculate the curves. (B) Uptake of TRITC-labeled yeast particles. Data acquisition and symbols as in A.

Results

DAip1 Is a Member of the WD-Repeat Family

During a cDNA screen for a PAK/STE20-related kinase from D. discoideum (GenBank accession number U51923), we isolated a partial clone encoding a protein that showed homology to the previously identified WD-repeat–containing cytoskeletal protein coronin. Sequence analysis of the complete cDNA revealed a polypeptide of 597 amino acid residues with a calculated molecular mass of 64 kD (Fig. 1 A), and an isoelectric point of 7.4. The gene is present in a single copy per haploid genome, and is constitutively expressed.

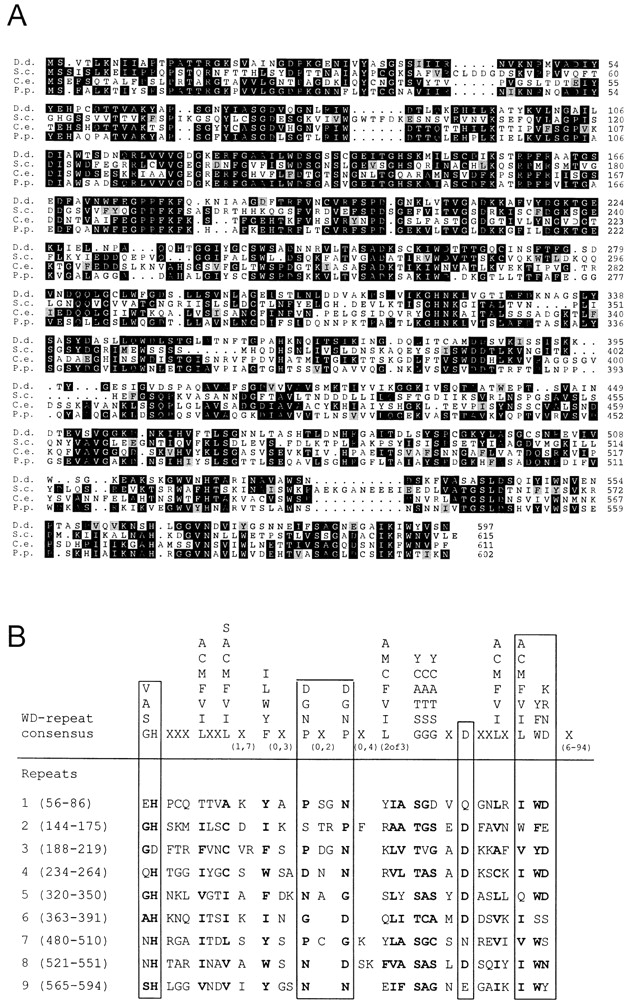

Figure 1.

Sequence analysis of D. discoideum DAip1. (A) Amino acid sequence alignment of DAip1 (D.d.) (GenBank accession number U36936) with the putative homologues Aip1p from S. cerevisiae (S.c.) (GenBank accession numbers S54451 and U35666), CO4F6.4 from C. elegans (C.e.) (GenBank accession number U42835), and P. polycephalum (P.p.) (Matsumoto et al. 1998). Alignment was performed using PILEUP (Genetics Computer Group) and the output was shaded using PRETTYBOX. Identical residues are shaded black, homologous residues are gray. The program used marks only homologous residues appearing within conserved blocks. Amino acid residues are numbered on the right. (B) Comparison of the amino acid sequences of the WD-repeat consensus described by Neer et al. 1994 (upper) and of DAip1 (lower). WD-repeat proteins are defined as having at least one unit that matches the consensus with zero or one mismatch and at least one other unit that has three or fewer mismatches. X means that any amino acid can be found at that position, and the numbers underneath give the range over which that symbol may be repeated. Numbers in brackets on the left give the positions of the individual repeats.

Comparison of the complete sequence to the protein databases revealed a significant degree of homology to Aip1p from S. cerevisiae, and during our studies it became evident that both proteins are also functionally related. Therefore, we refer to the new protein as Dictyostelium Aip1 (DAip1). An alignment of the DAip1 amino acid sequence with yeast Aip1p is shown in Fig. 1 A. The two sequences show 33% identity over their entire length. Aip1 homologues were also found in C. elegans and P. polycephalum (Fig. 1 A), and recently in Arabidopsis thaliana (GenBank accession number O23240), Xenopus laevis (Okada et al. 1999), and chickens, mice, and humans (Adler et al. 1999). Sequence identities of these proteins with DAip1 vary between 37 and 52%.

The DAip1 sequence contains nine WD40-repeat motifs extending from residues 56 to 594 (Fig. 1 B). When compared with the consensus (Neer et al. 1994), two WD units of DAip1 contain one mismatch (repeats 4 and 8), four contain two mismatches (repeats 3, 5, 6, and 9), two contain three mismatches (repeats 2 and 7), and the first repeat only loosely conforms to the consensus sequence (four mismatches). A putative nucleotide-binding motif is contained between amino acid residues 215 and 222. Analysis of the secondary structure predicts that the protein consists almost entirely of repeated β sheets interrupted by turns. Only a short α helix is positioned between residues 85 and 100.

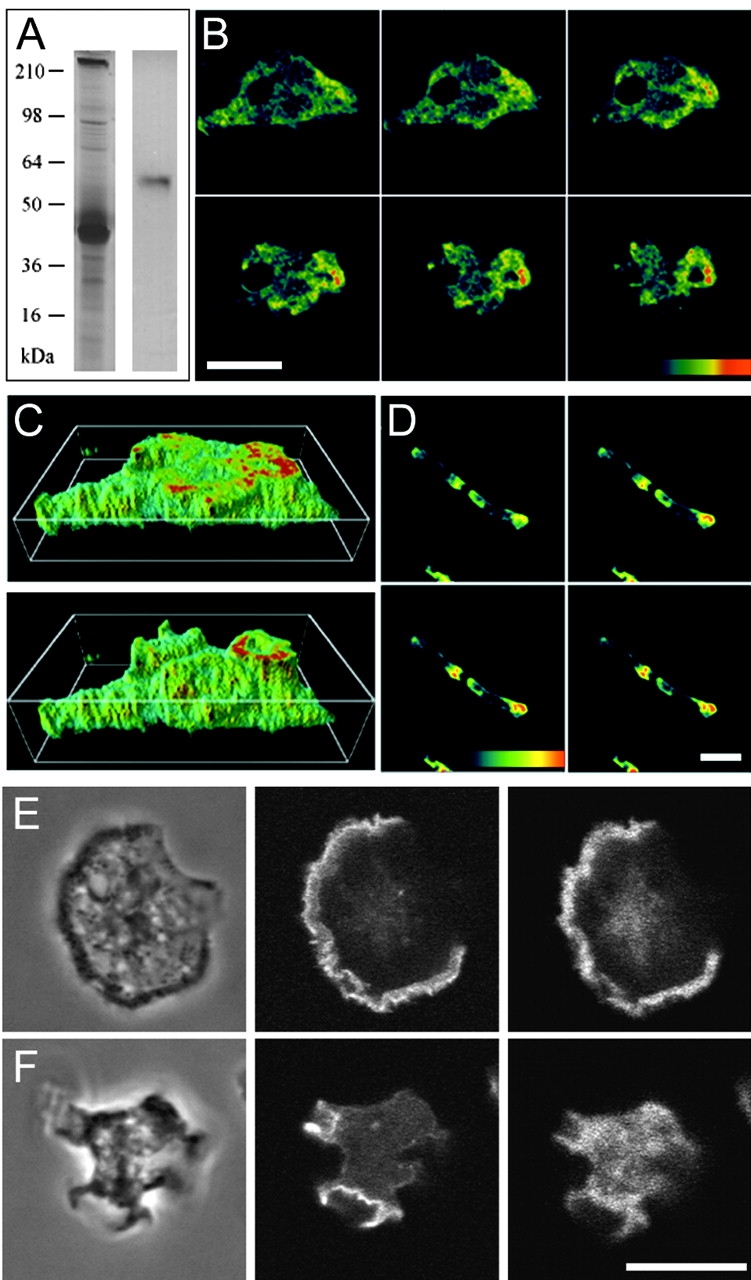

DAip1 Is Enriched in Cell Surface Projections

Antibodies that specifically recognized DAip1 in total cell lysates were used to show that DAip1 is a component of precipitated actin-myosin complexes (Fig. 2 A). Association of DAip1 with the actin system is supported by its intracellular localization. Immunofluorescence labeling of Dictyostelium cells in the growth phase showed an enrichment of DAip1 in the cell cortex. Crown-shaped extensions of the dorsal cell surface were most prominently labeled (Fig. 2B and Fig. C). These funnel-shaped protrusions are sites where nutrients from liquid medium are taken up by macropinocytosis (Hacker et al. 1997). In the elongated cells of the aggregation stage, DAip1 was distributed in a polarized fashion (Fig. 2 D). It was enriched in the anterior region of the cells and, to a minor extent, at their posterior poles. Double labeling of growth-phase cells confirmed the overlapping localization of F-actin and DAip1 in lamellipodia and crowns (Fig. 2E and Fig. F).

Figure 2.

Localization of DAip1 in a purified actin-myosin complex by Western blotting, and in the cell cortex and surface projections of Dictyostelium cells by immunofluorescence. (A) A purified actin-myosin complex was separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue (left lane), or blotted and probed with DAip1-specific mAb 246-153-2 (right lane). (B) Confocal sections of growth-phase AX2 wild-type cells labeled with DAip1-specific mAb 246-466-6. (C) Three-dimensional image reconstruction from confocal sections shown in B. (D) Confocal sections of aggregation-competent AX2 cells labeled with mAb 246-466-6. The color code represents relative fluorescence intensities as indicated by the colored scales. Distance between sections in B and D is 0.5 μm. (E and F) Confocal sections of two growth-phase AX2 cells double-labeled with DAip1-specific mAb 246-153-2 (right) and TRITC-phalloidin (middle) to visualize F-actin. Typical for the immunofluorescence labeling of DAip1 is the diffuse cytoplasmic distribution reflecting the presence of a cytoplasmic pool of the protein. Phase-contrast images are shown on the left. Bars, 10 μm.

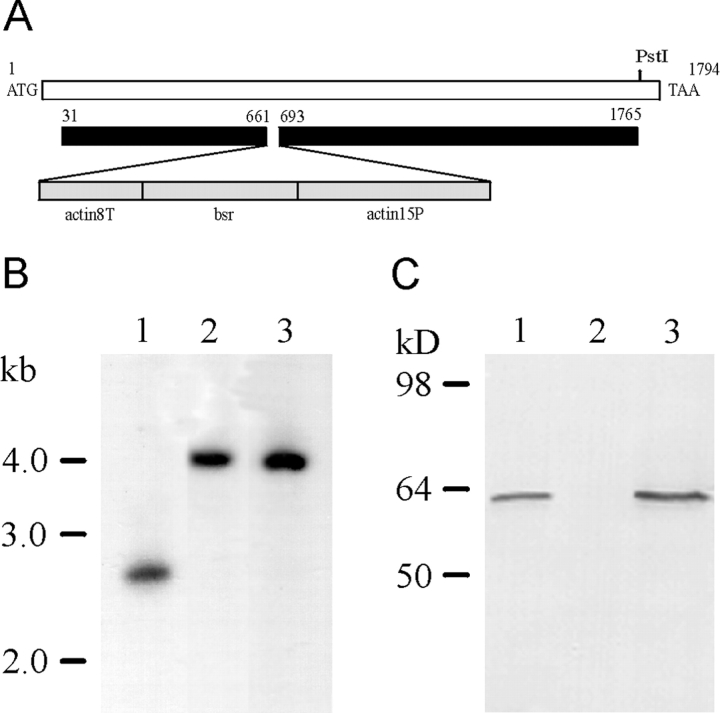

Generation of DAip1-Null Cells

To study the function of DAip1 in vivo, we eliminated DAip1 by gene replacement in the Dictyostelium wild-type strain AX2 using a blasticidin resistance cassette as marker for selection (Fig. 3 A). Mutants were identified by a shift in size of an EcoRI fragment of the DAip1 gene by 1.4 kb corresponding to the size of the blasticidin resistance gene cassette (Fig. 3 B). DAip1 was no longer detectable on Western blots of mutant cell lysates, whereas it was clearly recognized in wild-type and coronin-null cells (Fig. 3 C).

Figure 3.

Generation of DAip1-null cells by gene replacement. (A) Map of the DAip1 gene, and the construct used for the gene replacement. The blasticidin resistance gene (bsr) is transcribed from the actin-15 promoter (actin15P) and terminates in the actin-8 terminator (actin8T). (B) Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA. DNA of the wild-type AX2 (lane 1), or of DAip1-null mutants 9.1 (lane 2) and 10.10 (lane 3), was digested with EcoRI, and subjected to Southern blot analysis by hybridizing with a COOH-terminal fragment comprising nucleotides 1577–1791 of the DAip1 coding region. (C) Western blot analysis of DAip1 expression. Total cellular proteins from AX2 wild-type cells (lane 1), from 9.1 DAip1-null cells (lane 2), and from HG1569 coronin-null cells (lane 3) were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis using mAb 246-153-1.

Examination of DAip1-null cells by phase-contrast microscopy revealed that the mutant cells were larger than wild-type cells and tended to become multinucleate. Growth of DAip1-null cells on bacteria and in liquid medium was reduced. DAip1 proved not to be essential for multicellular development. On agar plates, DAip1-null cells formed normal fruiting bodies. In the following, we present a detailed analysis of the defects of the DAip1-null mutant in growth and cytokinesis, which suggests that the defects are a direct consequence of changes in the actin cytoskeleton dynamics caused by the lack of DAip1.

DAip1-Null Cells Show Altered Cytokinesis

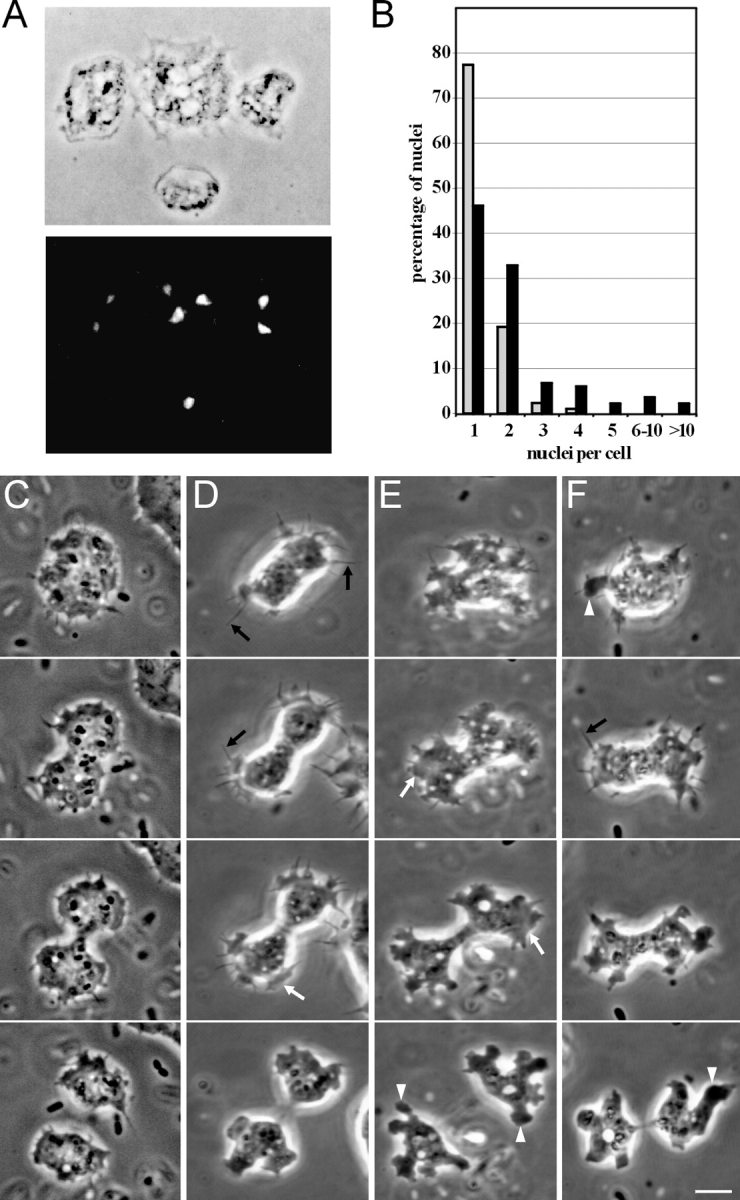

Staining of DAip1-null cells with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) revealed the conspicuous presence of multinucleate cells (Fig. 4 A). A quantitative analysis confirmed the shift in the DAip1-null cell population toward a larger number of nuclei per cell (Fig. 4 B). Furthermore, changes of the cell shape that occur during cytokinesis of DAip1-null cells show distinct alterations when compared with cytokinesis of wild-type cells (Fig. 4 C; Neujahr et al. 1997a; Weber et al. 1999a,Weber et al. 1999b). The duration of cytokinesis, as measured from the first detectable inception of the cleavage furrow until the separation of daughter cells, was significantly prolonged in DAip1-null cells when compared with wild-type cells (wild-type: t = 2.5 ± 0.4 min, DAip1-null: t = 3.4 ± 0.7 min; mean ± SD, n = 16, P < 2 × 10−4, t test). DAip1-null cells exhibited vigorous protrusive activity throughout cytokinesis. Frequently, the incipient cleavage furrow was not clearly distinguishable from the polar regions of a dividing cell. The mutant cells were characterized by the presence of exaggerated cortical protrusions, which are known to contain polymerized actin: filopodia, lamellipodia, and pseudopodia (Fig. 4, D–F). Such exceptional protrusive activity was also typical for the mutant cells in the interphase.

Figure 4.

DAip1-null cells are defective in cytokinesis. (A) Phase-contrast image (top), and fluorescence image after DAPI staining (bottom), of DAip1-null cells. (B) Histogram illustrating a quantitation of nuclei in AX2 wild-type (gray) and in DAip1-null cells (black). Cells cultivated for 2 d on glass coverslips in nutrient medium were fixed, the nuclei were stained with DAPI, and several hundred cells were counted. With cells grown in shaking culture, analogous results were obtained. (C) Shape of a wild-type AX2 cell during cytokinesis. Typically, only moderate ruffling at the polar regions is observed. (D–F) Cell shape of DAip1-null mutants during cytokinesis. Prominent cell protrusions appear as filopodia (black arrows in D and F), lamellipodia (white arrows in D and E), and pseudopodia (white arrowheads in E and F). The three forms convert into each other, yet filopodia and lamellipodia are predominant in the earlier stages, whereas pseudopodia are most frequent in the final stage of cytokinesis. The position of the incipient cleavage furrow is often not clearly discernible at early stages and remains covered with protrusions until the furrow has already ingressed substantially (E and F). Time intervals between consecutive frames: (C) 60, 70, and 40 s; (D) 60, 30, and 50 s; (E) 110, 110, and 140 s; (F) 80, 60, and 90 s. Bar, 10 μm.

DAip1-Null Cells Are Impaired in Macropinocytosis, Phagocytosis, and Motility

Loss of DAip1 led to a reduced growth rate of mutant cells both in liquid culture and on bacteria. In liquid medium, the generation time of DAip1-null cells was prolonged to 12 h as compared with 8 h determined for the wild-type. A large portion, if not the entire uptake of soluble nutrients in Dictyostelium, occurs through macropinocytosis (Hacker et al. 1997). Therefore, we measured the internalization of a fluid-phase marker, TRITC-dextran. The rate of fluid-phase uptake was decreased in DAip1-null cells to 56% relative to the wild-type rate (Fig. 5 A), but probably most of this residual uptake of fluid in the DAip1-mutant was still due to macropinocytosis (Fig. 5 B).

Next, we wanted to assay a pathway where the activity of the F-actin cytoskeleton can be affected by an experimental stimulus. In Dictyostelium, phagocytosis is induced by adhesion of a particle to the cell surface as opposed to macropinocytosis, which is a constitutive process. Therefore, we determined the rate of phagocytosis of yeast particles in wild-type and in DAip1-null cells. The rate of particle uptake in DAip1-null cells was reduced to 26% of the wild-type rate (Fig. 6 A). This strong deficiency in phagocytosis of yeast particles was paralleled by slow growth on bacterial lawns (Fig. 6 B).

To monitor the process of phagocytosis in vivo, we used GFP-tagged actin expressed in wild-type and DAip1-null cells. In wild-type cells, the formation of a phagocytic cup, from inception until the complete engulfment of a yeast particle, took between 20 and 40 s (Fig. 6 C). In the DAip1-null cells, the duration of this process was prolonged to 70–120 s (Fig. 6 D).

Since the radius of a colony is a cumulative function of both growth rate and of cell motility, we also compared the motility of wild-type and DAip1-null cells by a quantitative assay. The speed of locomotion of DAip1-null cells was reduced to 46% of the wild-type values (Table ).

Table 1.

Velocity of Growth-Phase Cells

| Cell strain | AX2 | DAip1-null | DAip1- overexpresser |

|---|---|---|---|

| Velocity (μm/min) | 3.7 ± 1.6 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 3.3 ± 1.2 |

Values are mean ± SD.

DAip1 Overexpression Suggests an Involvement of DAip1 in the Regulation of Actin Depolymerization

Since disruption of the DAip1 gene did not allow us to draw a definitive conclusion about its mode of action in vivo, we expressed DAip1 under control of an actin-15 promoter in DAip1-null cells. DAip1 accumulated to a level ∼20-fold higher than the endogenous DAip1 in the wild-type (data not shown). A quantitative analysis of the number of nuclei per cell in the DAip1-overexpressing cells indicated that the cytokinesis defect was partially rescued (data not shown). The motility of the DAip1-overexpressing cells was reversed to wild-type values (Table ).

Whereas the rate of pinocytosis in DAip1-overexpressing cells was almost identical to wild-type cells (Fig. 7 A), they phagocytosed yeast particles at a rate that was ∼50% higher than the rate determined for wild-type (Fig. 7 B). Overexpression of cytoskeletal proteins can sometimes be simulated by the addition of drugs that mimic the effect of actin-binding proteins. Cytochalasin A, known to block polymerization at the barbed end of actin filaments, decreases the rate of particle uptake and fluid-phase internalization in Dictyostelium (Maniak et al. 1995; Hacker et al. 1997), and thus does not reflect the effect of DAip1 overexpression. Lat-A is known to depolymerize existing actin filaments (Ayscough et al. 1997; Ayscough 1998). Here, we assayed its effect on endocytosis. Cells treated with Lat-A concentrations between 0.1 and 1 μM strongly increased the uptake of particles, even above the enhanced rate of uptake seen in the DAip1-overexpressing strain (Fig. 7 B). At the same doses, Lat-A did not stimulate, but rather inhibited, fluid-phase uptake (Fig. 7 A).

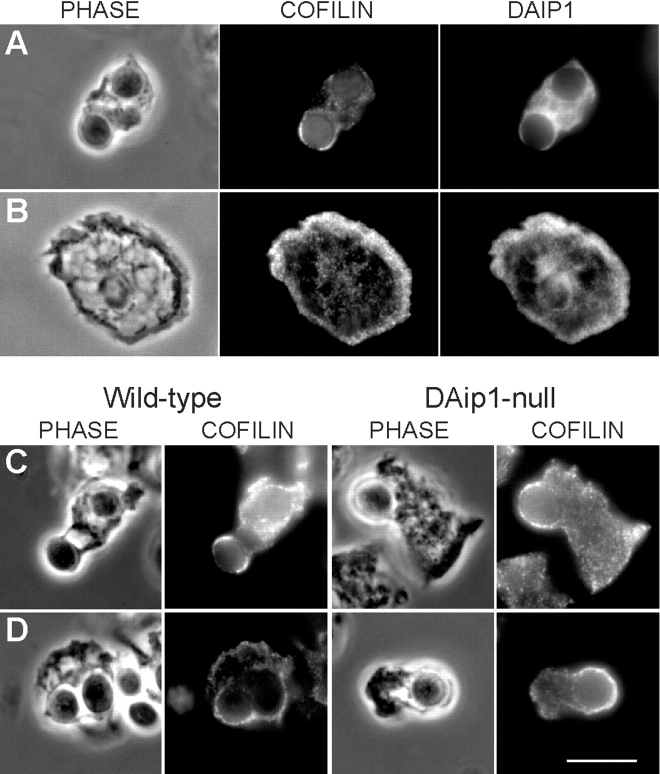

DAip1 and Cofilin Localize to Cortical Protrusions

Recent in vitro data suggested a functional interaction of DAip1 with cofilin (Aizawa et al. 1998; Okada et al. 1999). Therefore, we tested the distribution of DAip1 and cofilin in Dictyostelium wild-type cells by double immunolabeling. Cofilin and DAip1 are both enriched, but do not perfectly overlap, in phagocytic cups (Fig. 8 A) and in ruffling membranes (Fig. 8 B). Consistent with the previous report on the dynamics of GFP-cofilin in vivo (Aizawa et al. 1997), in wild-type and in DAip1-null cells cofilin was detected in early (Fig. 8 C) and late stages (Fig. 8 D) of phagocytic cup formation, as well as in ruffling membranes (not shown). Thus, the localization of cofilin in the DAip1-null mutant is apparently not altered in comparison to wild-type. In fixed preparations of DAip1-null cells, significantly more phagocytic cups were observed than in wild-type, consistent with the result that the process of phagocytic cup formation is prolonged in the mutant (Fig. 6C and Fig. D).

Figure 8.

Localization of cofilin in Dictyostelium wild-type and DAip1-null cells by immunofluorescence microscopy. (A and B) Colocalization of cofilin and DAip1 in Dictyostelium wild-type cells in phagocytic cups (A) and in lamellipodia (B) by double label immunofluorescence microscopy. (C and D) Wild-type and DAip1-mutant cells were labeled with cofilin-specific antibodies during early (C), and late stages (D) of phagocytosis of yeast particles. Bar, 10 μm.

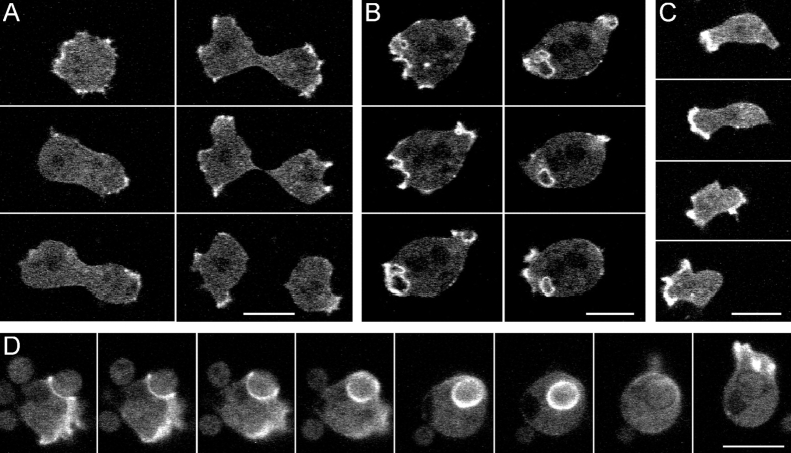

Dynamics of GFP-tagged DAip1 in Living Cells

To study the distribution of DAip1 in vivo, gene fusions were constructed comprising the full-length coding sequences of DAip1 and GFP. GFP was either fused to the NH2 terminus or to the COOH terminus of DAip1. The constructs were named GFP-(N)-DAip1 and DAip1-(C)-GFP, respectively. In DAip1-null cells, no functional rescue was achieved by expression of DAip1-(C)-GFP. Nevertheless, the intracellular distribution of the DAip1-(C)-GFP hybrid protein, both in wild-type and in DAip1-null cells, was similar to the antibody labeling of crowns and lamellipodia in wild-type cells (Fig. 2).

The expression of GFP-(N)-DAip1 in DAip1-null cells partially rescued the defects of DAip1-null cells. Their phagocytosis rate recovered to 80% of the wild-type rate, and the distribution of the number of nuclei was similar to that of wild-type cells (data not shown).

DAip1-null cells expressing the GFP-(N)-DAip1 construct showed a distinct labeling of cell surface protrusions. Using confocal microscopy, we recorded the dynamic redistribution of the GFP-(N)-DAip1 fusion protein in cells during cytokinesis, pinocytosis, directed movement, and phagocytosis (Fig. 9). A common feature of all these activities is the formation of specialized cortical structures rich in filamentous actin (de Hostos et al. 1991; Maniak et al. 1995; Hacker et al. 1997; Neujahr et al. 1997a). All these transient “dynamic organelles,” cortical protrusions at the poles of dividing cells (Fig. 9 A), macropinocytic crowns (Fig. 9 B), leading edges of locomoting cells (Fig. 9 C), and phagocytic cups (Fig. 9 D), were strongly enriched in GFP-(N)-DAip1. It is remarkable that GFP-(N)-DAip1 could be reshuffled between these structures in less than 30 s (Fig. 9 D, the last two frames).

Figure 9.

Localization of GFP-(N)-DAip1 fusion protein expressed in DAip1-null cells during cytokinesis (A), pinocytosis (B), cell movement (C), and phagocytosis (D). (A) GFP-(N)-DAip1 is enriched in the cortical protrusions at the onset and in the course of cell division. Time intervals between consecutive frames: 110, 70, 40, 20, and 30 s. (B) GFP-(N)-DAip1 is enriched in nascent macropinosomes. At the time point of the next recorded frame, the macropinosome was internalized and the GFP label disappeared (not shown). Time interval between consecutive frames: 10 s. (C) GFP-(N)-DAip1 is enriched at the leading edge of moving cells. Time intervals between consecutive frames: 40, 40, and 60 s. (D) GFP-(N)-DAip1 is enriched at the sites of enclosure and internalization of yeast particles. Approximately 1 min after the particle was engulfed, GFP-(N)-DAip1 was released from the phagosome. Shortly afterwards, the fusion protein was redistributed to the leading edge as cell movement commenced. Time interval between consecutive frames was 10 s up to the fourth frame and 30 s afterwards. Bars, 10 μm.

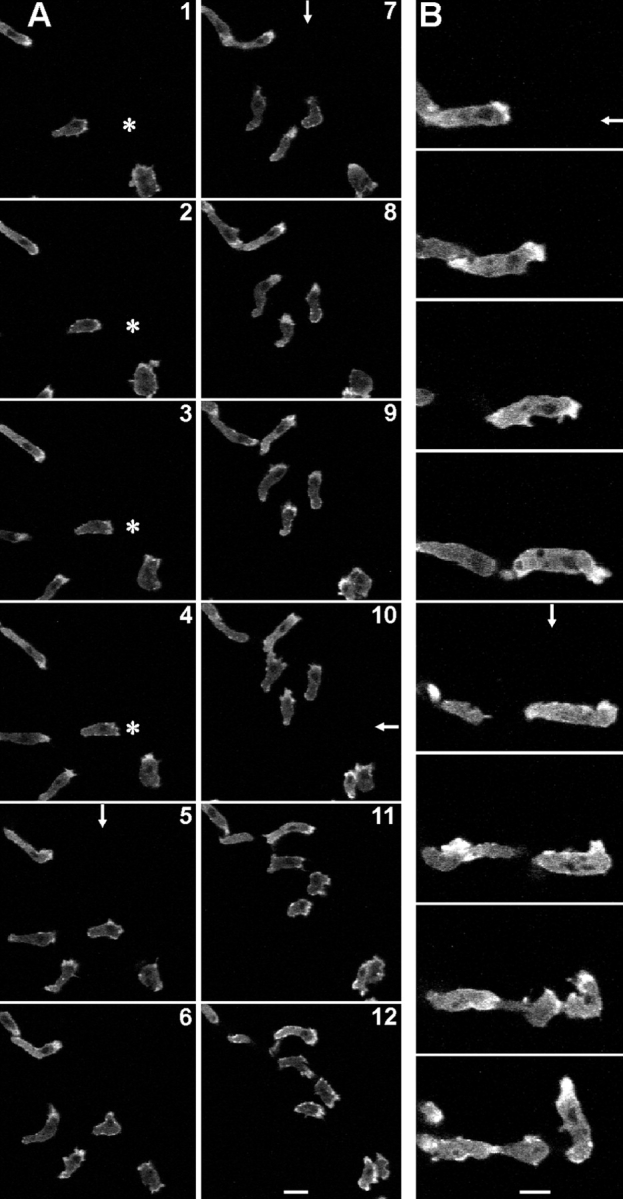

By local stimulation with the chemoattractant cAMP through a micropipette, the polarity of aggregation-competent Dictyostelium cells can be changed at will (Gerisch et al. 1975). A new front is elicited at the site of strongest stimulation, while the previous front is retracted, or the cell turns into a new direction (Kreitmeier et al. 1995; Weber et al. 1999a). Using this assay, we could show that GFP-(N)-DAip1 was localized to the leading fronts of cells moving in a chemotactic gradient, and was rapidly reshuffled into a newly elicited front evoked by the cAMP stimulus (Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

Rapid redistribution of GFP-(N)-DAip1 fusion protein expressed in DAip1-null cells moving in chemotactic gradients. The asterisk marks the position of the micropipette tip filled with the chemoattractant cAMP. Arrows indicate direction of the negative cAMP concentration gradient when the pipette was placed outside of the displayed field of view. An arrow is drawn only in those frames where the position of the pipette was changed. (A) Interval between frames, 40 s. Bar, 20 μm. (B) Intervals between frames, 60 s. Bar, 10 μm.

Discussion

DAip1 Is a Constituent of the Actin Cytoskeleton

D. discoideum Aip1 (DAip1) belongs to the WD-repeat family of proteins (Fig. 1; Neer et al. 1994). These proteins are thought to form a β-propeller structure, thereby exposing sites which participate in the assembly of macromolecular complexes. Especially the COOH terminus of DAip1 appears to play a role in protein interactions, since only expression of a fusion protein of DAip1 with GFP at the NH2 terminus was able to rescue the mutant phenotype, whereas a fusion of GFP to its COOH terminus was nonfunctional. This result indicates that GFP masks functionally important sites at the COOH terminus of DAip1, which are not necessary for localization but for interaction of DAip1 with an upstream regulator or an effector protein.

DAip1 is homologous to Aip1p from S. cerevisiae, an actin-interacting protein that has been identified using a two-hybrid screen (Amberg et al. 1995). Recently, Aip1-homologous sequences have been described for a variety of organisms ranging from plants to humans, indicating that Aip1 is conserved in evolution.

DAip1 is found in purified actin-myosin complexes and colocalizes with regions of the cell cortex known to be enriched in filamentous actin: phagocytic cups, crowns, leading edges of cells migrating toward a source of chemoattractant, and poles of dividing cells (Fig. 2, Fig. 9, and Fig. 10). The elimination of DAip1 by gene replacement results in defects both in macropinocytosis and in phagocytosis (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6), the main pathways responsible for fluid-phase and particle uptake in Dictyostelium. In both cases, the cell protrudes F-actin–rich extensions from its surface in order to capture and engulf the endocytic cargo (Maniak et al. 1995; Hacker et al. 1997). Although the mutant cells are capable of membrane ruffling and protrusive activity, the time needed to complete a phagocytic cup is largely increased (Fig. 6). Consequently, DAip1-null cells endocytose at a reduced rate. A defect in cytokinesis in DAip1-null cells is evident both on a solid surface and in shaking cultures (Fig. 4). During cytokinesis, DAip1 did not specifically localize to the cleavage furrow, but was enriched at the poles of dividing cells (Fig. 9 A). A detailed analysis of dividing DAip1-null cells revealed that their cytokinesis is substantially delayed. As a result of the reduced nutrient uptake and defective cytokinesis, DAip1-null cells were strongly retarded in growth when feeding on bacteria or when cultivated in liquid media.

DAip1 May Contribute to the Regulation of Actin Depolymerization

Overexpression of DAip1 in a DAip1-null mutant did not only rescue phagocytosis, but markedly increased particle uptake over wild-type rates, whereas fluid-phase uptake was barely affected. The effects of Lat-A observed in wild-type cells also distinguish phagocytosis, which is stimulated by the drug (Fig. 7 B), from macropinocytosis and cell migration, which both are inhibited by the same concentration of Lat-A (Fig. 7 A; Parent et al. 1998). The stimulating effect of both Lat-A and DAip1 overexpression on phagocytosis leads us to propose that DAip1 promotes actin depolymerization in vivo. On the basis of this hypothesis, the observed phenotypes can be explained in the following ways.

One possibility is that different stimuli make different sources of actin monomers available for polymerization. During phagocytosis, spreading of a lamella around a particle depends on a steady supply of monomeric actin. Depolymerization of actin filaments may be stimulated as a response to the continuous signal induced by adhesion of a particle, and could provide monomers for local actin assembly at the phagocytic cup. In distinction to phagocytic cups, surface ruffles for macropinocytosis and pseudopodia during directed migration are not necessarily supported by a solid substratum (Weber et al. 1995; Hacker et al. 1997). Therefore, a continuous, localized signal is absent. In these cases other signals could release actin monomers, e.g., from actin-sequestering proteins.

A second possible explanation is based on the fact that a phagocytic cup needs to follow precisely the shape of the particle during protrusion. If existing actin filaments do not depolymerize fast enough during this process, the structure becomes too rigid to allow close interaction between the membrane and the particle. To form a macropinosome in the absence of spatial guiding cues, the protruding surface ruffles must be rigid and persist until they fuse at their distal edges. The same argument applies to cell migration. Polarization of the cytoskeleton during protrusion of a leading edge needs to be maintained for a certain time, in order to achieve persistent directional migration.

Consistent with these ideas, DAip1-null cells are most severely affected in phagocytosis, which is reduced to 26% of the wild-type rate. The major reason for this reduction in the mutant appears to be a threefold slower protrusion of the phagocytic cup (Fig. 6). Fluid-phase uptake is only reduced to 56% of the wild-type rate. The DAip1-null cells migrate with 46% of the wild-type's velocity, suggesting that the requirements on cytoskeletal dynamics are similar for macropinocytosis and cell motility.

Cofilin as a Putative Effector Protein of Aip1

There is evidence in vitro that Aip1 exerts its effect on actin depolymerization through the stimulation of cofilin. Cofilin is a member of the ADF family known to depolymerize actin filaments at their pointed ends (Carlier et al. 1997; Lappalainen and Drubin 1997; Theriot 1997). It has been shown recently that Aip1 proteins bind to cofilin and strongly enhance its depolymerizing activity (Aizawa et al. 1998; Rodal et al. 1998; Iida and Yahara 1999; Okada et al. 1999).

Support for an interaction of Aip1 and cofilin is provided by the observation that GFP-tagged cofilin (Aizawa et al. 1997) and GFP-tagged DAip1 (this study) localize to the same structures in living cells. Like GFP-tagged DAip1, GFP-tagged cofilin accumulates in nascent phagocytic cups. However, it does not accumulate at sites where a macropinocytic crown is initiated. Only later, when the crown closes off to form a macropinosome, is GFP-cofilin enriched at these sites (Aizawa et al. 1997). Double labeling experiments that show a significant but not complete overlap in the distribution of DAip1 and cofilin provide additional support for a functional association of the two proteins in vivo (Fig. 8A and Fig. B, and Fig. 9 D). However, no clear-cut change in the distribution of cofilin during phagocytosis could be observed in the DAip1-null mutant (Fig. 8C and Fig. D). In light of the severe mutant phenotype (Fig. 6), this finding indicates that it is the activity and not the localization of cofilin that is affected by DAip1.

Although the results discussed above suggest that Aip1 acts through cofilin to enhance actin depolymerization (Aizawa et al. 1998; Rodal et al. 1998; Iida and Yahara 1999; Okada et al. 1999), the phenotype of a cofilin-overexpressing strain differs in some respect from that of the DAip1-overexpressing mutant. Different from what is shown in this work for DAip1, cofilin overexpression does not enhance phagocytosis, but instead leads to an increased velocity of cell migration (Aizawa et al. 1996). In part, the consequences of cofilin overexpression can be attributed to the drastically increased expression of actin, which accompanies the overexpression of cofilin. In the cofilin overexpresser, most of the actin is present in filamentous form and organized into bundles throughout the cells (Aizawa et al. 1996). In DAip1-overexpressing cells, the overall amount of actin is unchanged (data not shown). There is no cofilin-null mutant available in Dictyostelium to compare its phenotype to that of DAip1-null cells. The inability to obtain such a mutant in Dictyostelium suggests that cofilin is essential (Aizawa et al. 1995) as it is in yeast (Iida et al. 1993; Moon et al. 1993). The viability of the DAip1 mutant, on the other hand, suggests that cofilin function in vivo is in part independent of DAip1.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Günther Gerisch for his continuous support and stimulating discussions at all stages of the work. We thank Drs. Hiroyuki Aizawa and Ichiro Yahara for their generous gift of anti-cofilin antiserum, and John Murphy and Jean-Marc Schwartz for their help with image processing and for three-dimensional image reconstructions.

The work was supported by a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (MU 1415) to A. Müller-Taubenberger.

Footnotes

1.used in this paper: GFP, green fluorescent protein; Lat-A, latrunculin-A

References

- Adler H.J., Winnicki R.S., Gong T.-W.L., Lomax M.I. A gene upregulated in the acoustically damaged chick basilar papilla encodes a novel WD40 repeat protein. Genomics. 1999;56:59–69. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizawa H., Sutoh K., Tsubuki S., Kawashima S., Ishii A., Yahara I. Identification, characterization, and intracellular distribution of cofilin in Dictyostelium discoideum . J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:10923–10932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizawa H., Sutoh K., Yahara I. Overexpression of cofilin stimulates bundling of actin filaments, membrane ruffling, and cell movement in Dictyostelium . J. Cell Biol. 1996;132:335–344. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizawa H., Fukui Y., Yahara I. Live dynamics of Dictyostelium cofilin suggests a role in remodeling actin latticework into bundles. J. Cell Sci. 1997;110:2333–2344. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.19.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizawa H., Katadae M., Maruya M., Sameshima M., Murakami-Murofushi K., Yahara I. Contraction of actin bundles induced in Dictyostelium by overexpression of cofilin in response to hyperosmotic stress Mol. Biol. Cell. 9Suppl.1998. 93 [Google Scholar]

- Amberg D.C., Basart E., Botstein D. Defining protein interactions with yeast actin in vivo. Nature Struct. Biol. 1995;2:28–34. doi: 10.1038/nsb0195-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayscough K. Use of latrunculin-A, an actin monomer-binding drug. Methods Enzymol. 1998;298:18–25. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)98004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayscough K.R., Stryker J., Pokala N., Sanders M., Crews P., Drubin D.G. High rates of actin filament turnover in budding yeast and roles for actin in establishment and maintenance of cell polarity revealed using the actin inhibitor latrunculin-A. J. Cell Biol. 1997;137:399–416. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.2.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlier M.-F., Laurent V., Santolini J., Melki R., Didry D., Xia G.-X., Chua N.-H., Pantaloni D. Actin depolymerizing factor (ADF/cofilin) enhances the rate of filament turnoverimplication in actin-based motility. J. Cell Biol. 1997;136:1307–1323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.6.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claviez M., Pagh K., Maruta H., Baltes W., Fisher P., Gerisch G. Electron microscopic mapping of monoclonal antibodies on the tail region of Dictyostelium myosin. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1982;1:1017–1022. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David V., Gouin E., Van Troys M., Grogan A., Segal A.W., Ampe C., Cossart P. Identification of cofilin, coronin, Rac and capZ in actin tails using a Listeria affinity approach. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111:2877–2884. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.19.2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hostos E.L., Bradtke B., Lottspeich F., Guggenheim R., Gerisch G. Coronin, an actin-binding protein of Dictyostelium discoideum localized to cell surface projections, has sequence similarities to G protein β subunits. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1991;10:4097–4104. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04986.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hostos E.L., Rehfuess C., Bradtke B., Waddell D.R., Albrecht R., Murphy J., Gerisch G. Dictyostelium mutants lacking the cytoskeletal protein coronin are defective in cytokinesis and cell motility. J. Cell Biol. 1993;120:163–173. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devereux J., Haeberli P., Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucl. Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faix J., Gerisch G., Noegel A.A. Overexpression of the csA cell adhesion molecule under its own cAMP-regulated promoter impairs morphogenesis in Dictyostelium . J. Cell Sci. 1992;102:203–214. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faix J., Steinmetz M., Boves H., Kammerer R.A., Lottspeich F., Mintert U., Murphy J., Stock A., Aebi U., Gerisch G. Cortexillins, major determinants of cell shape and size, are actin-bundling proteins with a parallel coiled-coil tail. Cell. 1996;86:631–642. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fechheimer M., Taylor D.L. Isolation and characterization of a 30,000 dalton calcium sensitive actin cross-linking protein from Dictyostelium discoideum . J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:4514–4520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher P.R., Merkl R., Gerisch G. Quantitative analysis of cell-motility and chemotaxis in Dictyostelium discoideum by using an image processing system and a novel chemotaxis chamber providing stationary chemical gradients. J. Cell Biol. 1989;108:973–984. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.3.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerisch G., Keller H.U. Chemotactic reorientation of granulocytes stimulated with micropipettes containing fMet-Leu-Phe. J. Cell Sci. 1981;52:1–10. doi: 10.1242/jcs.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerisch G., Hülser D., Malchow D., Wick U. Cell communication by periodic cyclic-AMP pulses. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 1975;272:181–192. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1975.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerisch G., Albrecht R., Heizer C., Hodgkinson S., Maniak M. Chemoattractant-controlled accumulation of coronin at the leading edge of Dictyostelium cells monitored using a green fluorescent protein-coronin fusion protein. Curr. Biol. 1995;5:1280–1285. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode B.L., Wong J.J., Butty A.-C., Peter M., McCormack A.L., Yates J.R., Drubin D.G., Barnes G. Coronin promotes the rapid assembly and cross-linking of actin-filaments and may link the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 1999;144:83–98. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan A., Reeves E., Keep N., Wientjes F., Totty N.F., Burlingame A.L., Hsuan J.J., Segal A.W. Cytosolic phox proteins interact with and regulate the assembly of coronin in neutrophils. J. Cell Sci. 1997;110:3071–3081. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.24.3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker U., Albrecht R., Maniak M. Fluid-phase uptake by marcopinocytosis in Dictyostelium . J. Cell Sci. 1997;110:105–112. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil-Chapdelaine R.A., Tran N.K., Cooper J.A. The role of Saccharomyces cerevisiae coronin in the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:1281–1284. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim R., Tsien R.Y. Engineering green fluorescent protein for improved brightness, longer wavelength and fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Curr. Biol. 1996;6:178–182. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humbel B.M., Biegelmann E. A preparation protocol for postembedding immunoelectron microscopy of Dictyostelium discoideum with monoclonal antibodies. Scanning Microsc. 1992;6:817–825. [Google Scholar]

- Iida K., Yahara I. Cooperation of two actin-binding proteins, cofilin and Aip1, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genes to Cells. 1999;4:21–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida K., Moriyama K., Matsumoto S., Kawasaki H., Nishida E., Yahara I. Isolation of a yeast essential gene, COF1, that encodes a homologue of mammalian cofilin, a low-Mr actin-binding and depolymerizing protein. Gene. 1993;124:115–120. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90770-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungbluth A., von Arnim V., Biegelmann E., Humbel B., Schweiger A., Gerisch G. Strong increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of actin upon inhibition of oxidative phosphorylationcorrelation with reversible rearrangements in the actin skeleton of Dictyostelium cells. J. Cell Sci. 1994;107:117–125. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitmeier M., Gerisch G., Heizer C., Müller-Taubenberger A. A talin homologue of Dictyostelium rapidly assembles at the leading edge of cells in response to chemoattractant. J. Cell Biol. 1995;129:179–188. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen P., Drubin D.G. Cofilin promotes actin filament turnover in vivo. Nature. 1997;388:78–82. doi: 10.1038/40418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniak M. Green fluorescent protein in the visualization of particle uptake and fluid-phase endocytosis. Methods Enzymol. 1999;302:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)02008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniak M., Rauchenberger R., Albrecht R., Murphy J., Gerisch G. Coronin involved in phagocytosisdynamics of particle-induced relocalization visualized by a green fluorescent protein tag. Cell. 1995;83:915–924. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto S., Ogawa M., Kasakura T., Shimada Y., Mitsui M., Maruya M., Isohata M., Yahara I., Murakami-Morufushi K. A novel 66-kD stress protein, p66, associated with the process of cyst formation of Physarum polycephalum is a Physarum homologue of a yeast actin-interacting protein, AIP1p. J. Biochem. 1998;124:326–331. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon A.L., Janmey P.A., Louie K.A., Drubin D.G. Cofilin is an essential component of the yeast cytoskeleton. J. Cell Biol. 1993;120:421–435. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.2.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neer E.J., Schmidt C.J., Nambudripad R., Smith T.F. The ancient regulatory-protein family of WD-repeat proteins. Nature. 1994;371:297–300. doi: 10.1038/371297a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neujahr R., Heizer C., Gerisch G. Myosin II-independent processes in mitotic cells of Dictyostelium discoideumredistribution of the nuclei, rearrangement of the actin system and formation of the cleavage furrow J. Cell Sci. 110 1997. 123 137a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neujahr R., Heizer C., Albrecht R., Ecke M., Schwartz J.-M., Weber I., Gerisch G. Three-dimensional patterns and redistribution of myosin II and actin in mitotic Dictyostelium cells J. Cell Biol. 139 1997. 1793 1804b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada K., Obinata T., Abe H. XAIP1a Xenopus homologue of yeast actin interacting protein 1 (AIP1), which induces disassembly of actin filaments cooperatively with ADF/cofilin family proteins. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:1553–1565. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.10.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura M., Kung C., Wong S., Rodgers M., Thomas M.L. Definition of family of coronin-related proteins conserved between humans and miceclose genetic linkage between coronin-2 and CD45-associated protein. DNA Cell Biol. 1998;17:779–787. doi: 10.1089/dna.1998.17.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent C., Blacklock B., Froehlich W., Murphy D., Devreotes P. G protein signaling events are activated at the leading edge of chemotactic cells. Cell. 1998;95:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81784-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prassler J., Stocker S., Marriott G., Heidecker M., Kellermann J., Gerisch G. Interaction of a Dictyostelium member of the plastin/fimbrin family with actin filaments and actin–myosin complexes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1997;8:83–95. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodal A., Tetrault J., Amberg D., Drubin D. Aip1p functionally interacts with cofilin in vivo and in vitro Mol. Biol. Cell. 9Suppl.1998. 85 [Google Scholar]

- Sutoh K. A transformation vector for Dictyostelium discoideum with a new selectable marker, bsr. Plasmid. 1993;30:150–154. doi: 10.1006/plas.1993.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K., Nishihata J., Arai Y., Honma N., Yamamoto K., Irimura T., Toyoshima S. Molecular cloning of a novel actin-binding protein, p57, with a WD-repeat and a leucine zipper motif. FEBS Lett. 1995;364:283–288. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00393-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasaki A.G., Ohnuma M., Mabuchi I. Identification of actin-binding proteins from sea urchin eggs by F-actin affinity column chromatography. J. Biochem. 1997;122:226–236. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theriot J.A. Accelerating on a treadmillADF/cofilin promotes rapid actin filament turnover in the dynamic cytoskeleton. J. Cell Biol. 1997;136:1165–1168. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.6.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallraff E., Gerisch G. Screening for Dictyostelium mutants defective in cytoskeletal proteins by colony immunoblotting. Methods Enzymol. 1991;196:334–348. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)96030-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts D.J., Ashworth J.M. Growth of myxamoebae of the cellular slime mould Dictyostelium discoideum in axenic culture. Biochem. J. 1970;119:171–174. doi: 10.1042/bj1190171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber I., Wallraff E., Albrecht R., Gerisch G. Motility and substratum adhesion of Dictyostelium wild-type and cytoskeletal mutant cellsa study by RICM/bright-field double-view image analysis. J. Cell Sci. 1995;108:1519–1530. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.4.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber I., Niewöhner J., Faix J. Cytoskeletal protein mutations and cell motility in Dictyostelium Biochem. Soc. Symp. 65 1999. 245 265a [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber I., Gerisch G., Heizer C., Murphy J., Badelt K., Stock A., Schwartz J.-M., Faix J. Cytokinesis mediated through the recruitment of cortexillins into the cleavage furrow EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 18 1999. 586 594b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal M., Jungbluth A., Heidecker M., Mühlbauer B., Heizer C., Schwartz J.-M., Marriott G., Gerisch G. Microfilament dynamics during cell movement and chemotaxis monitored using a GFP-actin fusion protein. Curr. Biol. 1997;7:176–183. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(97)70088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]