Abstract

The carotid body's physiological role is to sense arterial oxygen, CO2 and pH. It is however, also powerfully excited by inhibitors of oxidative phosphorylation. This latter observation is the cornerstone of the mitochondrial hypothesis which proposes that oxygen is sensed through changes in energy metabolism. All of these stimuli act in a similar manner, i.e. by inhibiting a background TASK-like potassium channel (KB) they induce membrane depolarization and thus neurosecretion. In this study we have evaluated the role of ATP in modulating KB channels. We find that KB channels are strongly activated by MgATP (but not ATP4−) within the physiological range (K1/2 = 2.3 mm). This effect was mimicked by other Mg-nucleotides including GTP, UTP, AMP-PCP and ATP-γ-S, but not by PPi or AMP, suggesting that channel activity is regulated by a Mg-nucleotide sensor. Channel activation by MgATP was not antagonized by either 1 mm AMP or 500 μm ADP. Thus MgATP is probably the principal nucleotide regulating channel activity in the intact cell. We therefore investigated the effects of metabolic inhibition upon both [Mg2+]i, as an index of MgATP depletion, and channel activity in cell-attached patches. The extent of increase in [Mg2+]i (and thus MgATP depletion) in response to inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation were consistent with a decline in [MgATP]i playing a prominent role in mediating inhibition of KB channel activity, and the response of arterial chemoreceptors to metabolic compromise.

The carotid body is a peripheral arterial chemoreceptor which senses oxygen, carbon dioxide and arterial pH. In response to hypoxia, hypercapnia or acidosis it evokes an increase in neural discharge within afferent fibres of the carotid sinus nerve which project to cardiovascular and respiratory control centres in the brain stem. This results in increased ventilation, stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system and modulation of blood flow and cardiac output (Daly, 1997). The primary sensory element within the carotid body is the type-1 or glomus cell (Fidone & Gonzalez, 1986; Gonzalez et al. 1994).

Type-1 cells express a background potassium channel (KB channel) with biophysical and pharmacological properties similar to those of the TASK group of tandem-p-domain K+ channels, including weak rectification (similar to that predicted by the Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz constant field equation); inhibition by acidosis, quinidine and bupivacaine; activation by halothane; and insensitivity to TEA and 4-AP (Buckler et al. 2000). These channels are active over a wide range of membrane potentials and are the predominant K+ conductance at the resting membrane potential (Buckler, 1997; Williams & Buckler, 2004). As a consequence modulation of these channels has a marked influence upon the type-1 cell. Their inhibition by either hypoxia or acidosis, the two main physiological stimuli of arterial chemoreceptors, causes destabilization of the resting membrane potential resulting in a depolarizing receptor potential which then initiates electrical activity and voltage-gated calcium entry (Buckler & Vaughan-Jones, 1994a, 1994b; Buckler, 1997; Buckler et al. 2000). Inhibition of other K+ channels, particularly the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels by hypoxia and other chemostimuli (Peers, 1990; Peers & O'Donnell, 1990; Peers & Green, 1991) may facilitate some aspects of this electrical signalling process although their precise role is still unclear (Peers & Wyatt, 2007). This calcium signal in turn leads to neurosecretion from the type-1 cell (Montoro et al. 1996) and consequently excitation of chemoreceptor afferents (through release of ATP and acetylcholine and the concomitant activation of postsynaptic P2X and nicotinic receptors; Zhang et al. 2000; Rong et al. 2003). Modulation of type-1 cell background K+ channels is therefore thought to be a pivotal event in the chemotransduction process for both hypoxia and acidic stimuli. Similar chemosensory roles have also recently been suggested for TASK-like potassium channels in mediating responses to hypoxia in pulmonary vascular smooth muscle (Olschewski et al. 2006) and in mediating the excitatory actions of acidosis in some putative central chemoreceptive neurons (Bayliss et al. 2001; Washburn et al. 2002; Washburn et al. 2003).

In addition to being able to sense hypoxia and acidosis we have also shown that the background K+ current of type-1 cells is sensitive to inhibitors of mitochondrial energy metabolism (Wyatt & Buckler, 2004). Metabolic inhibition results in a rapid decline in background K+ current, membrane depolarization, voltage-gated Ca2+ entry (Buckler & Vaughan-Jones, 1998; Wyatt & Buckler, 2004), and neurosecretion (Ortega Saenz et al. 2003) just as for physiological stimuli. This observation provides a part explanation for the long established phenomenon that the carotid body is rapidly and powerfully excited by numerous inhibitors of oxidative phosphorylation (Heymans et al. 1931; Shen & Hauss, 1939; Anichkov & Belen'kii, 1963; Mulligan & Lahiri, 1981; Mulligan et al. 1981; Obeso et al. 1989) (see also Fidone & Gonzalez, 1986; Gonzalez et al. 1994 and refs therein). Moreover the ability of these channels to respond to hypoxic stimuli is ablated when mitochondrial function is inhibited suggesting a strong link between energy metabolism and oxygen sensing (Wyatt & Buckler, 2004). Indeed it may be that this organ primarily responds to metabolic status rather than oxygen per se since it can also be excited by inhibitors of glycolysis (Obeso et al. 1986) and, in some preparations, by hypoglycaemia (Pardal & Lopez Barneo, 2002). In this respect it is of interest to note that another endogenous TASK-like potassium channel has recently been implicated in mediating glucose sensing in orexin neurons (Burdakov et al. 2006). The capacity to sense some aspect of metabolic status could therefore be another emerging role for endogenous TASK-like K+ channels.

The nature of the link between metabolism and background K+ channel activity has not yet been established. We have, however, noted in previous studies that background K+ channel activity in excised membrane patches can be enhanced by millimolar levels of ATP (Williams & Buckler, 2004). Here we investigate the potential for channel modulation by cytosolic nucleotides in greater detail. We find that, in excised inside-out patches, type-1 cell background K+ channels are indeed strongly modulated by variation in MgATP at levels within the physiological range (with a K1/2 in the low millimolar range). We also describe sensitivity to a number of other Mg-nucleotides, including GTP, UTP, AMP-PCP and ATP-γ-S, which suggests a mechanism that may involve some form of magnesium–nucleotide sensor rather than an enzymatic process. These data are consistent with a direct link between metabolism and cell excitability mediated through changes in cytosolic, or submembrane, ATP levels.

Methods

Cell isolation

Carotid bodies were excised from anaesthetized (4% halothane) Sprague–Dawley neonatal rats (10–15 days old) and put in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. The rats were then killed by decapitation whilst still anaesthetized. These procedures conformed with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, were approved by a local ethical review committee and were conducted in accordance with UK Home Office Project and Personal licences. The carotid bodies were enzymatically dissociated using collagenase type I (0.4 mg ml−1, Worthington) and trypsin (0.2 mg ml−1, Sigma) for about 20 min at 37°C and then mechanically triturated with a sterile glass Pasteur pipette, as previously described (Buckler, 1997). The cell suspension was then centrifuged, resuspended in Ham's F-12 medium or a 50/50 mixture of Ham's F12 and Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 i.u ml−1, penicillin 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 84 U l−1 insulin) and plated out onto poly d-lysine (Sigma) coated coverslips. Cells were kept at 37°C with 5% CO2 in humidified air until use (2–8 h).

Electrophysiology

Experiments were performed using the cell-attached and inside-out configuration of the patch clamp technique. Single channel recordings were performed using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, CA, USA). Patch current was filtered at 2 kHz and acquired at 20 kHz using a Cambridge Electronic Design (CED) power 1401 A/D converter and Spike 4 software. Electrodes were made from borosilicate glass capillaries (Harvard Apparatus Ltd, Edenbridge, Kent, UK) and coated with Sylgard 184 (Dow Corning). Electrode tips were fire-polished before using. The pipette filling solution contained (mm): 140 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, 10 Hepes, 10 tetraethylammonium (TEA, Sigma)-Cl, 5 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, Calbiochem), pH 7.4 with KOH (final [K+]: 145 mm). Only electrodes with resistance between 5 and 15 MΩ and seal resistances 5 GΩ were used. Pipette potential was held at +70 mV (membrane potential =−70 mV) throughout the experiment unless otherwise stated. The bath was grounded with an Ag–AgCl pellet.

Measurement of intracellular magnesium

Cells were loaded with Mag-Indo-1 by incubation in a solution of 2.5–5 μm Mag-Indo-1 AM in culture medium or bicarbonate-buffered Tyrode solution at room temperature for 15–30 min and then were transferred to normal culture medium, at room temperature, for 15–60 min before use. Mag-Indo-1 fluorescence was excited at 340 nm and the emitted fluorescence measured at 405 ± 16 nm and 495 ± 10 nm using photomultiplier tubes. Data acquisition and signal processing was performed using a CED power 1401 and Spike software. Experiments measuring intracellular magnesium concentration ([Mg2+]i) were conducted in Ca2+-free Tyrode solution to prevent any large changes in intracellular calcium during application of hypoxia, anoxia or metabolic inhibitors (see Buckler & Vaughan-Jones, 1994a, b; Buckler, 1997; Buckler et al. 2000). Note that although Mag-Indo-1 has a higher affinity for Ca2+ than Mg2+ (the dissociation constants for Mg-Mag-indo-1 and Ca-Mag-Indo-1 are 2.7 × 10−3m and 3.5 × 10−5m, respectively; Molecular Probes) since [Mg2+]i is typically around 0.5–1 mm (Grubbs, 2002), whereas the intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) is typically around 100 nm under our experimental conditions (see Buckler & Vaughan-Jones, 1998; Wyatt & Buckler, 2004) the concentration of the Ca2+-bound form will be less than 1/50th of that of the Mg2+-bound form. Consequently, under these conditions, this indicator primarily reports changes in [Mg2+]i not calcium.

Solutions

Standard HCO3−-buffered Tyrode solution contained (mm): 117 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 23 NaHCO3, 1.0 MgCl2, 2.5 CaCl2 and 11 glucose. Ca-free HCO3−-buffered Tyrode solution lacked CaCl2 and contained 3.5 mm MgCl2 and 1 mm EGTA. High-K-Ca-free bicarbonate-buffered Tyrode solution contained (mm): 21.5 NaCl, 100 KCl, 23 NaHCO3, 3.5 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, 11 glucose. All normoxic bicarbonate-buffered Tyrode solutions were bubbled with 5% CO2–95% air. Hypoxic Tyrode solution was bubbled with 5% CO2–95% N2; PO2 = 2 Torr. Anoxic Tyrode solutions were bubbled with 5% CO2–95% N2 and included 0.5 mm Na2S2O4 pH 7.4–7.45.

The ‘intracellular solution’ used for recording from inside-out patches contained (mm): 130 KCl, 5 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 10 Hepes and 10 glucose. The pH of this solution was adjusted to 7.2 with KOH (final K+ concentration = 152 mm). K2ATP, KADP, AMP, Na2AMP-PCP (β,γ-methylene-ATP), Li4ATP-γ-S, NaGTP and Na3UTP were added to the intracellular solution directly just before starting the experiments and the pH was re-adjusted to 7.2. In experiments with triphosphate nucleotides, MgCl2 was increased as necessary in order to maintain a free Mg2+ level of approx. 3–4 mm (except in the Mg2+-free experiments). The effects of ATP and pyrophosphate in magnesium-free solution where tested in a solution containing (mm): 130 KCl, 10 EGTA, 2.5 EDTA, 10 Hepes and 10 glucose with pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. All the nucleotides used in this work were from Sigma. Solutions were superfused at ∼2 ml min−1 through a recording chamber with a volume of ∼80 μl. Electrophysiological experiments were conducted at 28–32°C except experiments with rotenone, which were performed at 34–35°C; measurements of [Mg2+]i were conducted at 36°C.

Data analysis

Single channel recordings from inside-out patches were analysed with Spike 4.0 (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK). Channel activity was quantified as the open probability multiplied by the number of active channels in the patch (NPopen). Open events were detected using a simple threshold crossing method. Thresholds were set at currents equivalent to 50% of the main conductance level (approx 16 pS as determined from all-points histograms) for a single channel opening and at ((N − 1) × 100 + 50)% for multiple (N) channel openings. In order to account for possible variation in the number of channels in a patch, the effects of various compounds are reported as a relative change in NPopen where NPopen in the presence of the drug is divided by the control value for NPopen (NPopen/NPopen,control). Dose-dependent activation of the channels by ATP was fitted to the Hill equation:

where Nmax is the maximum value of relative NPopen, EC50 is the ATP concentration required for half-maximal channel activation and n is the Hill coefficient, using SigmaPlot 8.0 (Systat Software Inc., Richmond, CA, USA). All values reported are mean (± s.e.m.) unless otherwise stated. Statistical significance of the dose dependent activation of the channel by ATP was determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's post hoc t test using SPSS (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA). Other statistical comparisons were conducted using two-tailed paired, or non-paired, Student's t test as appropriate in Sigma Plot or Microsoft Excel.

Results

Channel activity in cell-attached and inside-out patches

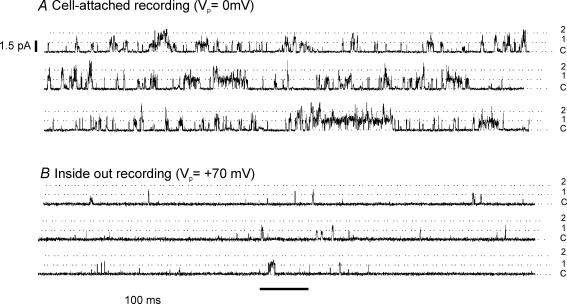

The predominant form of single channel activity observed upon formation of the cell-attached recording configuration (performed in normal bicarbonate Tyrode solution and with TEA and 4-AP in the pipette solution, see Methods) had a main conductance level of approximately 16 pS and rapid flickery openings (see, e.g. Figs 1A, 4A and Fig. 7B). Upon subsequent formation of the inside-out configuration (in intracellular solution) we routinely observed continued single channel activity, albeit at a much reduced frequency (Fig. 1B). This single channel activity also had a mean single channel conductance of about 16 pS (mean current amplitude of 1.12 ± 0.05 pA, n = 12 at a pipette potential of +70 mV) and rapid kinetics. In addition we often observed higher current levels which could represent higher conductance states of the same channel or the simultaneous opening of more than one channel. This channel activity corresponds to that previously described in these cells as a TASK-like background K+ channel (Williams & Buckler, 2004) and is believed to be the channel primarily responsible for the oxygen and metabolism sensitive background K+ currents observed in intact type-1 cells (see below). In common with previous studies from this laboratory we found these channels to have a very high relative abundance in the type-1 cell membrane, i.e. we observed background K+ channel activity in almost all patches successfully formed and frequently obtained more than one channel in each patch. Occasionally, we also observed a few other forms of channel activity but due to their low frequency these channels were not studied further.

Figure 1. Background K+ channel activity in cell-attached and inside-out patches.

A, three sections, 1 s each, from a continuous recording of background K+ channel activity in a cell-attached patch. The cell was superfused with a normal bicarbonate-buffered Tyrode solution. Pipette potential was 0 mV (patch membrane potential = cell resting potential). B, three sections of a continuous recording (1 s each) taken from the same patch as in A, but after formation of the inside patch recording configuration and following completion of channel rundown. The internal aspect of the patch was superfused with an intracellular solution lacking ATP. Pipette potential = 70 mV (patch membrane potential =−70 mV).

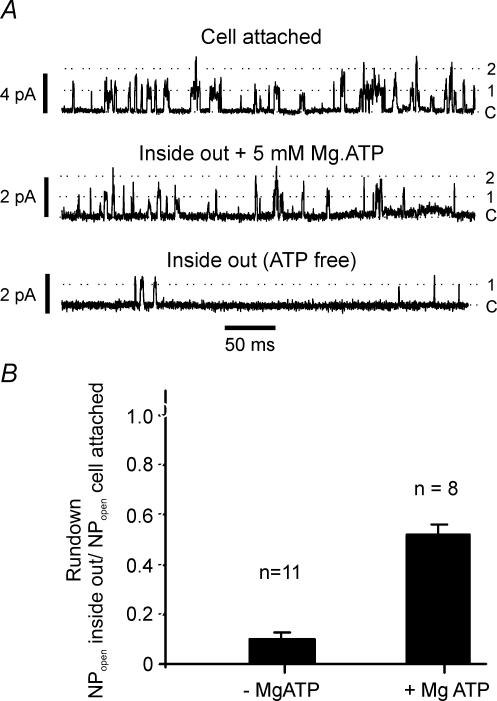

Figure 4. Effects of MgATP on rundown.

A, sections of recording from the same patch under cell-attached conditions in normal bicarbonate Tyrode solution (top trace) at a pipette potential of +70 mV (membrane potential approx −140 mV), and following patch excision into an intracellular solution containing 5 mm ATP (middle trace) at a pipette potential of +70 mV, and following subsequent MgATP removal (bottom trace). Note significant rundown in channel activity even in the presence of MgATP. B, comparison of channel rundown observed in patches excised into an intracellular solution containing 5 mm MgATP with that observed upon patch excision into an ATP-free intracellular solution. NPopen was calculated for each patch at least 60 s following patch excision and is expressed relative to channel activity (NPopen) recorded from the same patch in the cell-attached configuration prior to patch excision. Data are means (+s.e.m.).

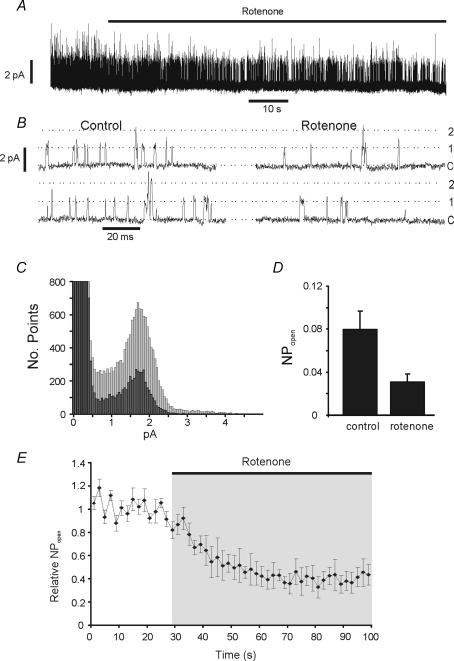

Figure 7. Effects of rotenone on channel activity in cell-attached patch.

A, recording from a cell-attached patch. The cell was bathed in high K+ Ca2+-free bicarbonate-buffered Tyrode solution. Pipette potential was +80 mV (membrane potential approx −90 mV). Trace shows effects of application of 1 μm rotenone. B, sections of cell-attached patch recording from experiment shown in part A. Traces on the right are taken from the control period and those on the left > 40 s after application of rotenone. C, all-points histogram from above experiment. Ten-second sections of trace were analysed from the control period (light bars) and after > 40 s of exposure to rotenone (dark bars). Bin width = 50 fA. Note that rotenone decreases the frequency of all points representing channel activity in the patch. Note also that the peak amplitude is the same in the presence and absence of rotenone. D, summary of effects of rotenone on channel activity in cell-attached patches. NPopen in the presence of rotenone was determined > 40 s after application of this compound. Data are means +s.e.m.; n = 6. E, time course of effects of rotenone on channel activity in cell-attached patches. Mean NPopen was determined at 2 s intervals from continuous records of single channel activity. Data are means ± s.e.m. for 6 patches.

Activation of background K+ channels by ATP in excised patches

In view of the rapid rundown in channel activity that occurs upon patch excision (see above and Williams & Buckler, 2004), studies into channel regulation in the inside-out patch were not commenced until this rundown was complete (approx. 1 min). Following rundown previous studies have shown that type-1 cell background K+ channel activity can be increased by application of MgATP to the inside of the patch (Williams & Buckler, 2004). We have now confirmed this fundamental observation in a large number of inside-out patches. In the majority of the patches tested, the addition of MgATP to the cytosolic side of the patch induced a robust, rapid and reversible increase in channel activity (Figs 2A and B and 4A). Comparison of channel activity using all-points histograms revealed a near identical distribution of current amplitudes corresponding to the main conductance level for a single channel opening (Fig. 2C) in the presence and absence of MgATP. This suggests that 5 mm MgATP increases the open probability of the background K+ channels previously active in the excised patch rather than activating a distinct, but previously dormant, channel. An increase in the frequency of higher conductance levels was also often seen, which probably represents multiple channel openings. Using a threshold crossing method (see Methods), analysis of 59 patches revealed that 5 mm MgATP increased NPopen by twofold or greater in 55 patches (i.e. 93%Fig. 2D). The mean relative increase in NPopen with 5 mm MgATP was 5.3 ± 0.3-fold (range 1.7- to 11-fold). In no instance did we observe 5 mm MgATP to inhibit background K+ channel activity.

Figure 2. Effects of 5 mm MgATP on channel activity in an inside-out patch.

A, top trace shows a continuous recording of channel activity in an inside-out patch. The patch was bathed in intracellular solution with or without 5 mm MgATP. Pipette potential was +80 mV (membrane potential −80 mV). Lower trace shows channel activity calculated as NPopen over successive 2 s intervals. B, inside-out single channel recording from another patch on a faster time base showing increase in channel activity in response to 5 mm MgATP. Pipette potential +70 mV (membrane potential −70 mV). C, all-points histograms constructed from two 10 s sections of an inside-out recording in the absence (black bars) and presence (grey bars) of 5 mm MgATP. Data taken from the patch shown in B at a pipette potential of +70 mV. Bin width 50 fA. D, frequency histogram showing extent of increase in channel activity caused by 5 mm MgATP. Relative NPopen is calculated as the ratio of NPopen in the presence of MgATP divided by that in its absence (control NPopen). NPopen was determined using a 50% threshold crossing method. Data from 59 inside-out patches.

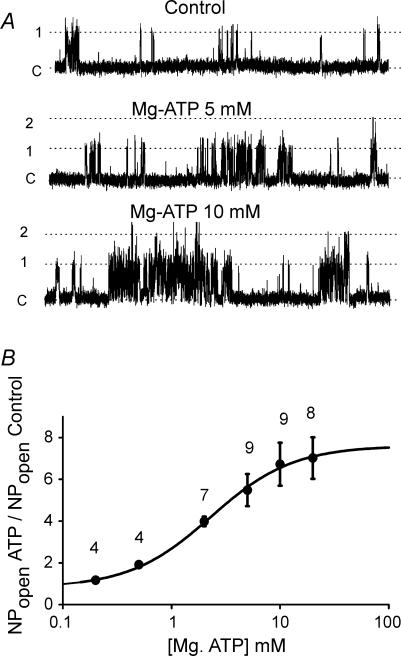

In order to define the sensitivity of background K+ channels to MgATP we studied the effects of a wide range of concentrations, from 0.2 to 20 mm, on channel activity (Fig. 3). A statistically significant response to ATP was evident at 0.5 mm ATP (NPopen = 0.02 ± 0.01 control and 0.03 ± 0.01 0.5 mm ATP, P < 0.05) and from this level upwards there was a graduated increase in channel activity with increasing MgATP concentration up to an apparent maximum around 10 mm ATP where an average ∼6-fold increase in channel activity was observed (NPopen 0.17 ± 0.01, n = 9). The dose-dependent activation of the channel by MgATP was adequately described (R2= 0.996) by a Hill equation with an estimated EC50 = 2.3 mm ATP and a Hill coefficient (n) = 1.2 (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Dose–response effects of MgATP on single channel activity.

A, inside-out patch recordings of background channel activity in the presence of varying levels of MgATP. Pipette potential +70 mV. B, summary of effects of 0.2–20 mm MgATP on single channel activity. Channel activity, determined as NPopen in the presence of MgATP, was normalized to that observed in the absence of MgATP (NPopen/NPopen,basal) for each patch/MgATP concentration. One-way analysis of variance showed significant effect of MgATP (P < 0.0001). Bonferoni's post hoc t test revealed that the effects of MgATP were significant at levels of 0.5 mm and above (P < 0.05). Line of best fit is the Hill equation obtained by nonlinear regression analysis (SigmaPlot). Hill constant = 1.15, EC50 = 2.3 mm. Data points are means ± s.e.m. with n indicated above each point.

In view of the dramatic and very rapid rundown in background K+ channel activity upon patch excision and powerful stimulatory effects of MgATP upon channel activity in excised patches, we sought to determine the extent to which channel rundown might simply result from loss of cytosolic ATP. Direct excision of patches from the cell-attached configuration into the inside-out configuration in the presence of 5 mm MgATP greatly attenuated channel rundown but did not fully prevent it. In eight such experiments patch excision into MgATP still resulted in a 52 ± 4.3% (P < 0.01, Fig. 4) decline in channel activity suggesting that the loss of other cytosolic factors in addition to MgATP also contributes to channel rundown. Comparison of this rundown with that observed in the absence of MgATP (in which channel activity falls to 10.6 ± 2.8% of that observed during cell-attached recording (P < 0.00001, n = 11) nevertheless emphasizes that, on a proportionate basis, the majority of rundown on patch excision can be attributed to loss of MgATP, i.e. of a 10-fold reduction in channel activity on patch excision, approximately 5-fold loss of activity could be attributable to loss of MgATP and 2-fold to other factors.

Effects of other nucleotides on channel activity

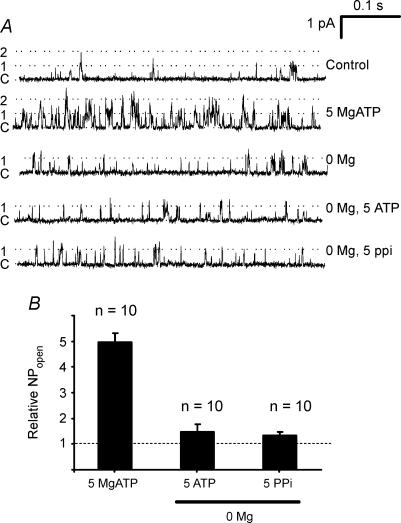

We have previously reported that high levels of ADP (2 mm) can also increase background K+ channel activity in inside-out patches (Williams & Buckler, 2004). Consequently we sought to try to determine the specificity of the effects of nucleotides. In the studies conducted above, Mg2+ ions have been added in near equimolar amounts to that of ATP such that free Mg2+ remains constant and the predominant form of ATP present in solution is that complexed to Mg2+ (i.e. MgATP−). In order to determine whether it was the MgATP form that was responsible for channel activation, or indeed whether it mattered if ATP was complexed to Mg2+ or not, we conducted a series of experiments under Mg+-free conditions. In the absence of intracellular magnesium ions (plus 2.5 mm EDTA), 5 mm ATP had no significant effect upon channel activity causing, on average, a 1.5 ± 0.3-fold increase in NPopen (n = 10, n.s., Fig. 5A and B). This degree of channel activation was substantially (and significantly, P < 0.001) less than the 4.8 ± 0.4-fold increase in channel activity seen with 5 mm MgATP in the same patches. These data indicate that it is the Mg-bound form of ATP that is responsible for activation of background K+ channels. We also sought to determine whether the effects of MgATP might be a non-specific effect of polyvalent anions by testing the effects of pyrophosphate (PPi). As pyrophosphate readily precipitates in the presence of magnesium ions these experiments were again conducted in magnesium-free medium. Under these conditions 5 mm pyrophosphate had no discernable effect (PPi increased NPopen by 1.3 ± 0.2-fold, n = 10, n.s., Fig. 5A and B) when compared to channel activity in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free conditions alone.

Figure 5. Effects of ATP (Mg free) and pyrophosphate on channel activity.

A, inside-out patch recordings in control intracellular solution containing 4 mm free [Mg2+] (top trace), intracellular solution plus 5 mm MgATP (second trace), magnesium-free intracellular solution (third trace), magnesium-free intracellular solution plus 5 mm ATP (fourth trace) and Mg-free intracellular solution plus 5 mm pyrophosphate (bottom trace). B, comparison of effects of 5 mm MgATP, Mg-free ATP and Mg-free pyrophosphate on channel activity. Relative NPopen was calculated using either Mg-containing intracellular solution as control (for MgATP) or Mg-free intracellular solution as control (for Mg-free ATP and pyrophosphate). Data are means (+s.e.m.). Effects of Mg-free ATP (n = 10) and pyrophosphate (n = 10) were not significant.

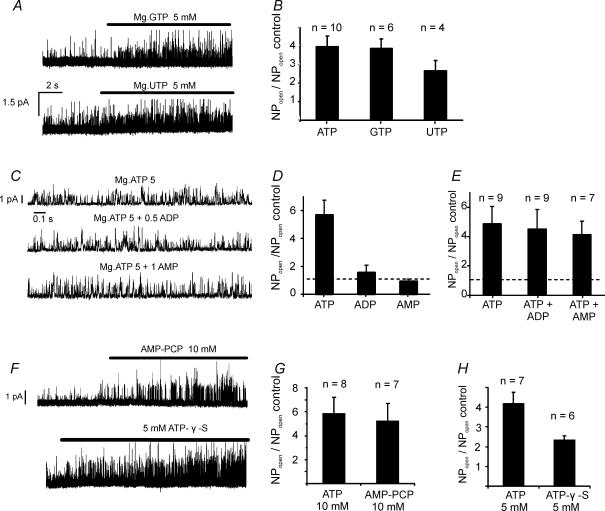

In order to determine whether the nature of the base had any effect upon the ability of nucleotides to activate background K+ channel activity, we examined the effects of other nucleotide triphosphates containing a different purine base (GTP) and a pyrimidine base (UTP). Both of these nucleotides were also powerful activators of background K+ channels (Fig. 6A). Five millimolar MgGTP increased NPopen by 3.9 ± 0.5-fold (n = 6, P < 0.002) and 5 mm MgUTP increased NPopen by 2.7 ± 0.6-fold (n = 4, P < 0.04) compared to basal. The effects of both MgGTP and MgUTP were not however, significantly different from those of 5 mm MgATP as determined in the same patches (relative NPopen compared to 5 mm MgATP was 1.2 ± 0.1 for MgGTP and 0.8 ± 0.1 for MgUTP, Fig. 6B). Thus both MgGTP and MgUTP appear to be as effective as MgATP in increasing channel activity.

Figure 6. Effects of other nucleotides on channel activity.

A, recordings from the same inside-out patch showing effects of both 5 mm MgGTP (top) and 5 mm MgUTP (bottom) on channel activity. Pipette potential +70 mV. B, summary of effects of MgGTP and MgUTP, compared to MgATP, on channel activity in inside-out patches. Channel activity is expressed as NPopen in presence of nucleotide relative to NPopen,basal in absence of nucleotide. Plot shows means +s.e.m., with n indicated above each bar. C, recording of single channel activity in an excised inside-out patch. All records are from the same patch showing channel activity in the presence of 5 mm MgATP, in the presence of 5 mm MgATP + 0.5 mm ADP and in the presence of 5 mm MgATP + 1 mm AMP. D, effects of 0.5 mm ADP and 1 mm AMP alone on relative channel activity. Note lack of effect of either nucleotide at these concentrations on channel activity. E, effects of 0.5 mm ADP and 1 mm AMP on relative channel activity recorded in the presence of 5 mm MgATP. F, inside-out patch recording showing effects of 10 mm AMP-PCP or 5 mm ATP-γ-S on single channel activity. Pipette potential +70 mV. G, comparison of effects of 10 mm AMP-PCP with those of 10 mm ATP on relative channel activity. H, comparison of effects of 5 mm ATP with those of 5 mm ATP-γ-S on relative channel activity.

Since background K+ channel activity is strongly dependent upon energy metabolism (see below) we decided to determine whether the effects of MgATP upon channel activity might be antagonized by either ADP or AMP. ADP alone at high (millimolar) levels stimulates channel activity (Williams & Buckler, 2004); but such levels are unlikely to be attained within cells (because adenylate kinase converts ADP to AMP and ATP, see e.g. Allen et al. 1985). In this series of experiments we therefore investigated the effects of lower levels of MgADP upon channel activity both alone and in the presence of MgATP (5 mm). At 500 μm, MgADP had no significant effect upon channel activity when applied alone (NPopen = 0.06 ± 0.01 control and 0.07 ± 0.01 with 500 μm MgADP, n = 5, n.s., Fig. 6D) and also failed to significantly alter channel activity recorded in the presence of MgATP (NPopen = 92 ± 3% of that recorded in 5 mm MgATP alone, n = 9, n.s., Fig. 6C and E). We also performed a similar study to look at the effects of AMP. AMP alone (1 mm) had no effect upon background K+ channel activity (NPopen = 0.06 ± 0.01 control and 0.05 ± 0.02 with 1 mm AMP, n = 5, n.s.) and also failed to have any effect upon channel activity recorded in the presence of 5 mm MgATP (NPopen in 5 mm Mg ATP + 1 mm AMP = 95 ± 4% of that with 5 mm MgATP alone, n = 7; Fig. 6C and E). Thus neither ADP nor AMP appeared to antagonize the effects of MgATP upon background K+ channel activity.

In order to gain some insight into the mechanism by which ATP exerts its effects upon channel activity we also studied the effects of two analogues. The non-hydrolysable ATP analog AMP-PCP (β,γ-methylene ATP) and ATP-γ-S which is reputedly a poor substrate for ATPases and phosphatases but can be utilized by kinases. AMP-PCP at 10 mm increased background K+ channel activity (NPopen) by 5.6 ± 1.5-fold (n = 7, P < 0.02, Fig. 6F). The effects of AMP-PCP were indistinguishable from an equivalent level of MgATP (5.8 ± 1.4-fold increase in NPopen, n = 8, Fig. 6G). ATP-γ-S at 5 mm also increased background K+ channel activity (Fig. 6F and H) albeit to a lesser extent than 5 mm MgATP. In this series of experiments 5 mm ATP caused a 4.17 ± 0.59-fold increase in NPopen whereas in the same patches ATP-γ-S caused only a 2.32 ± 0.22-fold increase with increase in NPopen (n = 6, Fig. 6H).

Sensitivity of channel activity to metabolic inhibition in cell-attached patches and effects of metabolic inhibition on cytosolic ATP

In view of the sensitivity of these background K+ channels to millimolar levels of cytosolic Mg-ATP we next sought to further confirm their sensitivity to metabolic inhibitors in situ (i.e. in the cell-attached configuration). We have previously shown that background K+ current in type-1 cells is greatly reduced by a wide range of inhibitors of oxidative phosphorylation (Wyatt & Buckler, 2004), and that background K+ channel activity is reduced by both CN and 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP; Williams & Buckler, 2004). Figure 7A and B shows data confirming that the same is true for another inhibitor of oxidative phosphorylation, rotenone (which inhibits complex 1 of the mitochondrial electron transport chain). In this experiment the cell was superfused with a 100 mm K+ Ca-free bicarbonate-buffered Tyrode solution (see Methods) to depolarize and stabilize the cell's resting membrane potential and to prevent large increases in intracellular [Ca2+]i during application of rotenone. Pipette potential was held at +80 mV such that the membrane potential of the patch would be around −90 mV, thus ensuring that only background K+ channels were active. Under these conditions rotenone caused a marked inhibition of channel activity by about 60% (Fig. 7D) after 1 min exposure, an effect comparable to that previously reported for cyanide and 2,4-dinitrophenol (Williams & Buckler, 2004). Analysis of all-points histograms (Fig. 7C) revealed that the effects of rotenone were manifest at all current levels corresponding to channel openings. The channel activity remaining in the presence of rotenone was indistinguishable from that observed in its absence except for a lower frequency of opening (Fig. 7B). These data suggest that rotenone only partially inhibits the activity of a single population of channels. We also analysed the time course of this effect. Channel activity was observed to begin to decline within 10 s of application of rotenone (solution exchange alone takes 2–3 s) and reached a minimum about 30 s later (Fig. 7E).

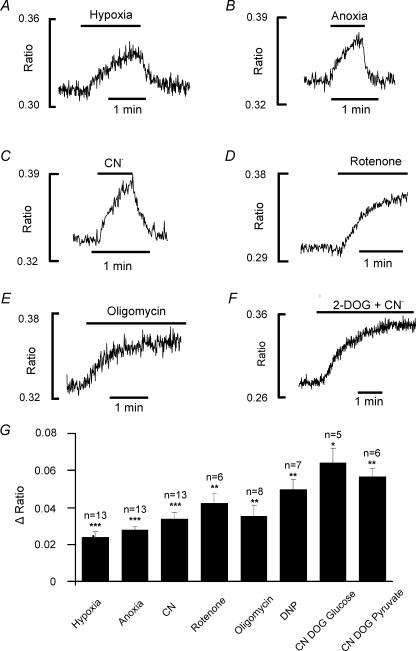

Because of the very small size of the carotid body it was impractical to directly measure changes in ATP in isolated type-1 cells in response to metabolic blockade. We have instead taken advantage of the fact that when there is net MgATP hydrolysis free magnesium ions are released into the cytosol and cytosolic [Mg2+]i increases. By directly measuring [Mg2+]i one can therefore gauge, approximately, the time course and extent of cellular MgATP depletion (Leyssens et al. 1996). Type-1 cells loaded with Mag-Indo-1 (see Methods) were superfused with a Ca2+-free bicarbonate-buffered Tyrode solution (to prevent changes in intracellular [Ca2+]i from interfering with [Mg2+]i measurement) at 36°C and exposed to brief intervals of hypoxia (Fig. 8A), anoxia (Fig. 8B), cyanide (2 mm; Fig. 8C), rotenone (1 μm; Fig. 8D), 2,4-dinitrophenol (250 μm) or oligomycin (2.5 μg ml−1; Fig. 8E). In response to all inhibitors of oxidative phosphorylation the Mag-Indo-1 fluorescence ratio began to increase almost immediately indicating an increase in free [Mg2+]i. A similar response was also seen with hypoxia, albeit to a slightly lesser extent than with some of the metabolic inhibitors. By 1–1.5 min the Mag-Indo-1 fluorescence ratio had increased by 0.024 ± 0.003 (P < 0.0001) in response to hypoxia, by 0.028 ± 0.002 (P < 0.0001) in response to anoxia and by between 0.035 ± 0.002 (P < 0.0001, CN) and 0.050 ± 0.005 (P < 0.001, DNP) in response to metabolic inhibitors (see Fig. 8G). In order to semiquantify this response we also exposed type-1 cells to a combination of 10 mm 2-deoxyglucose (DOG) to inhibit glycolysis plus 2 mm CN. Perfusion with this medium was continued until the ensuing rise in Mag-Indo-1 fluorescence ratio appeared to reach a maximum, which was presumed to equate to near complete exhaustion of cytosolic ATP. This experiment was conducted upon cells bathed in a normal Tyrode solution containing glucose (n = 5) and in a Tyrode solution lacking glucose but containing 5 mm pyruvate (n = 6) as an alternative metabolic substrate. In both instances the increase in Mag-Indo-1 fluorescence ratio attained at the end of incubation in DOG + CN was less than double that seen in response to brief application of CN alone or any of the other inhibitors of oxidative phosphorylation (0.064 ± 0.007, P < 0.002 in glucose-containing medium and 0.056 ± 0.004, P < 0.001 in pyruvate medium, average of both = 0.060); see Fig. 8. Assuming that the relation between Mag-Indo-1 ratio and Mg2+ concentration is approximately linear in the low millimolar range (Kd for Mg-Mag-Indo is approx. 2.7 mm), this result would suggest that even brief exposure to metabolic inhibitors results in a rapid decline in MgATP levels to between 42% (CN) and 20% (DNP) of the resting level. In response to hypoxia we estimate that MgATP levels decline to about 60% of the resting level.

Figure 8. Effects of hypoxia and metabolic inhibitors on cytosolic magnesium.

A–F, emission fluorescence ratio (405/495) of Mag-Indo-1 in isolated type-1 cells showing effects of, hypoxia (A), anoxia (B), 2 mm cyanide (C), 1 μm rotenone (D), 2.5 μg ml−1 oligomycin B (E), 2 mm cyanide + 10 mm 2-deoxyglucose (glucose-free Tyrode solution containing 5 mm pyruvate) (F). G, comparison of effects of brief application (1–1.5 min) of hypoxia, anoxia, cyanide, rotenone, oligomycin and 2,4-dinitrophenol with those of prolonged application of cyanide (2 mm) plus 2-deoxyglucose (10 mm) in both glucose-containing and glucose-free (+ pyruvate) Tyrode solution. Increase in ratio signifies increase in intracellular magnesium. Data are means +s.e.m.; n is indicated above each bar; *P < 0.002, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001 (paired t test). Recordings were conducted in a Ca2+-free Tyrode solution.

Discussion

Functional roles of background K+ channels

Background K+ currents play a fundamental role in chemoreception in type-1 cells in that they control the cells' resting membrane potential. The channels described in this and previous studies are those believed to be primarily responsible for generating this background K+ current, on account of their relative abundance in the type-1 cell membrane, activity in cell-attached patches at potentials close to the resting membrane potential, and similar pharmacology (Buckler et al. 2000; Williams & Buckler, 2004). The biophysical and pharmacological properties of these channels are remarkably similar to those of the TASK subfamily of tandem-p-domain K+ channels (Buckler et al. 2000). Moreover a number of studies have now reported that various members of the tandem-p-domain K+ channel family including TASK-1, TASK-2, TASK-3, TRAAK and TREK-1 are expressed in the carotid body and/or type-1 cell (Buckler et al. 2000; Yamamoto et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2006; Yamamoto & Taniguchi, 2006). The endogenous background K+ channel may therefore comprised tandem-p-domain K+ channel subunits, although formal identification is not yet available.

Endogenous TASK-like currents have also been described in many other excitable cells including cerebellar granule neurones (Millar et al. 2000; Maingret et al. 2001; Han et al. 2002; Kang et al. 2004), motor neurones (Talley et al. 2001), serotonergic neurones (Washburn et al. 2002), locus coeruleus neurones (Bayliss et al. 2001), adrenal glomerulosa cells (Czirjak et al. 2000) and cardiac myocytes (Kim et al. 1999). The properties of these channels suggest that one of their primary functions might be to control cell excitability by virtue of setting resting membrane potential and input resistance. In this context it is notable that the activity of these channels is often modulated by neurotransmitters (Talley et al. 2000). Indeed there is emerging evidence that the background K+ current in the type-1 cell can also be modulated in this manner (Fearon et al. 2003).

Background K+ channels are also increasingly being implicated in the process of chemoreception. TASK-like channels are thought to be involved in acid sensing in some putative central chemoreceptors including locus coeruleus neurones and serotonergic neurones of the medullary raphe (Bayliss et al. 2001; Washburn et al. 2002; Washburn et al. 2003), peripheral chemoreceptors (Buckler & Vaughan-Jones, 1994a; Buckler et al. 2000) and in nociceptive neurons (Cooper et al. 2004). In addition to being involved in acid sensing, TASK-like channels also play a role in oxygen sensing in the carotid body (Buckler, 1997) and human pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells (Olschewski et al. 2006). A TASK-like channel has also recently been implicated in glucose sensing in orexin neurones (Burdakov et al. 2006). These observations suggest that another general role for some endogenous TASK-like background K+ channels may be to sense metabolic stress. The sensitivity of background K+ channels to MgATP described here could provide an explanation for this sensitivity to metabolic disturbances.

Metabolism, background K+ channel activity, and chemoreceptor function

The possibility that background K+ channels are regulated by metabolic signals is of considerable interest with respect to chemoreceptor function. There are many hypotheses as to how oxygen is sensed by arterial chemoreceptors. Whilst we cannot resolve this issue here, not least because the chemoreceptive properties of the carotid body may reflect a composite of a number of oxygen-dependent signalling pathways rather than just one (Prabhakar, 2006), the mitochondrial hypothesis seems remarkably robust. It has been demonstrated repeatedly that the carotid body and/or isolated type-1 cells are excited strongly by most inhibitors of energy metabolism including numerous electron-transport inhibitors, uncouplers and ATP-synthase inhibitors (Heymans et al. 1931; Shen & Hauss, 1939; Anichkov & Belen'kii, 1963; Mulligan & Lahiri, 1981; Mulligan et al. 1981; Obeso et al. 1989; Duchen & Biscoe, 1992; Ortega Saenz et al. 2003; Wyatt & Buckler, 2004). Indeed cyanide has frequently been used as a surrogate stimulus of peripheral chemoreceptors. It is important to note in this context that what occurs seems to be a genuine excitation of chemoreceptor tissue, at least in response to brief inhibition of metabolism. Whilst many neurons and glia will respond to energy starvation, as occurs during ischaemia, with release of neurotransmitters this is often a slow process borne out of loss of ionic homeostasis and non-exocytotic release (Schomig, 1990; Rossi et al. 2000). In type-1 cells, and in some other oxygen sensing cells, e.g. chromaffin cells (Inoue et al. 1998), the rapid sequence of events linking inhibition of metabolism to membrane depolarization, voltage gated Ca2+ entry and exocytosis strongly suggests the presence of a specific metabolic signalling pathway.

Previous studies have shown that mitochondrial metabolism is coupled to type-1 cell excitation via inhibition of background K+ channels, membrane depolarization and subsequent elevation of intracellular calcium (Buckler & Vaughan-Jones, 1998; Wyatt & Buckler, 2004; Williams & Buckler, 2004). These events occur with a wide range of inhibitors including rotenone, myxothiazol, cyanide, FCCP, DNP and oligomycin. The fact that such a diverse range of mitochondrial inhibitors are able to influence channel activity suggests that the coupling factor, or factors, are likely to be closely associated with energy production itself rather than any other aspect of mitochondrial metabolism. The observation that neurosecretion can also be evoked by glycolytic inhibitors (Obeso et al. 1986) or hypoglycaemia (Pardal & Lopez Barneo, 2002) is also suggestive of a general sensitivity to energy status.

Role of ATP in linking mitochondrial metabolism to background K+ channel function

We have demonstrated that background K+ channel activity can be modulated by changing MgATP levels within the low millimolar range (with a K1/2 of 2.3 mm). This indicates that, in principle, changes in cytosolic MgATP could effectively regulate channel activity (note that cytosolic levels of other nucleotides are much lower than MgATP).

The extent to which MgATP levels must fall in order to cause a given reduction in channel activity can be estimated using the Hill equation, our dose–response data (Fig. 3B) and an estimate of resting MgATP (there are no data for the type-1 cell, but in brain tissue ATP levels are approximately 3 mm; Erecinska & Silver, 1994). To achieve the 60% inhibition of channel activity we have observed with cyanide, DNP and rotenone (Fig. 7D) would require a 75% decrease in [MgATP]. This poses the question as to whether cellular ATP levels could indeed fall this much in response to metabolic inhibition. Attempts at measuring changes in ATP levels in the carotid body have produced mixed results with a 55–75% decline in ATP levels reported for some metabolic inhibitors, e.g. CN and antimycin (Obeso et al. 1985; Verna et al. 1990). Our own estimates based on [Mg2+]i measurements suggest a similar decline in ATP levels of around 60–80% with a range of inhibitors of oxidative phosphorylation (see Fig. 8). Changes in global MgATP levels are therefore similar to what we would estimate to be required to account for the decline in background K+ channel activity.

Responses of background K+ channels to metabolic inhibition are manifest within tens of seconds (see Fig. 7E). This raises the question as to whether MgATP levels could change quickly enough to account for the observed channel inhibition. Estimates of ATP turnover can be obtained from measurements of uptake of metabolic substrates. Although the carotid body was once considered to have an exceptionally high oxygen consumption, a reasonable estimate for the whole organ would seem to be about 1.3 ml (100 g)−1 min−1 (Gonzalez et al. 1994). If all oxygen is consumed by oxidative phosphorylation (with 1 mol O2 generating 6 mol ATP), this gives an average ATP turnover fuelled by oxidative metabolism of about 3.5 mmol kg−1 min−1 for the carotid body as a whole. Estimates of energy consumption can also be derived from measurements of glucose utilization which, in the in vitro carotid body, is about 120 μmol kg−1 min−1 (Obeso et al. 1993). Assuming that 60% of glucose taken up is utilized in oxidative phosphorylation (and generates 36 mol ATP per mol glucose) this gives an ATP production rate of about 2.6 mmol kg−1 min−1. As pointed out by Obeso et al. (1993), only some 20% of the carotid body is actually composed of glomus cells yet these utilize 90% of the glucose. So the rate of ATP production by oxidative metabolism in type-1 cells should be in the range 12–16 mmol kg−1 min−1. Thus, upon cessation of oxidative metabolism, high energy phosphate levels should start to decline at a similarly rapid rate at least until anaerobic metabolism catches up and/or ATP utilization is reduced. The process of global MgATP depletion can be monitored by observing the coincident release of Mg2+ ions (Leyssens et al. 1996). The data in Fig. 8 show that upon inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation there is a relatively rapid increase in cytosolic [Mg2+]i with little appreciable delay. This rise in [Mg2+]i is nevertheless about 3-fold slower than the inhibition of K+ channel activity by rotenone. It is, however, important to note two factors which will confound direct temporal comparison of these events. Firstly channel activity will be determined by submembrane MgATP levels whereas Mag-Indo monitors global change in intracellular magnesium which will include both cytoplasmic and nuclear spaces (which is a significant fraction of a type-1 cell); secondly, even within the cytosol, there is evidence that nucleotide diffusion may be restricted in the proximity of the membrane (Rich et al. 2000). Indeed it has been argued that this restricted diffusion in combination with membrane ATPase activity and phosphotransfer networks involving creatine kinase and adenylate kinase can result in submembrane ATP levels being much more sensitive to changes in cellular energy metabolism than those in the bulk cytosol (Abraham et al. 2002; Selivanov et al. 2004). We can estimate submembrane energy consumption in the type-1 cell using data from previous electrophysiological recordings. Type-1 cell resting K+ conductance is about 300 pS (Buckler, 1997), with a resting potential of −60 mV and an EK of about −90 mV this gives a background K+ current of 9 pA, which is equivalent to a flux of 5.6 × 10−15 mol K+ min−1. Assuming rat type-1 cells have a spherical radius of 5 μm (and a volume of 5.2 × 10−13 dm3), resting K+ efflux via leak channels is equivalent to about 10 mmol dm−3 intracellular fluid (icf) min−1. If the cell is not to become K+ depleted this must be balanced by an equivalent K+ uptake by the Na+–K+-ATPase at a cost of 0.5 ATP per K+. Energy consumption by the Na+–K+-ATPase alone in an isolated type-1 cell is therefore equivalent to 5 mmol ATP dm−3 icf min−1 (or if expressed relative to membrane surface area 15.5 × 10−6μmol cm−2 s−1, which is 3 times that estimated for cardiac myocytes; Selivanov et al. 2004). Membrane ATP consumption alone in the type-1 cell would therefore seem to be quite substantial. Thus changes in MgATP levels in the submembrane region may well be significantly more rapid than changes in global [Mg2+]i.

In summary, given the ATP sensitivity of this channel, a moderately high rate of both global ATP utilization and particularly membrane ATP consumption in the type-1 cell, it seems probable that changes in submembrane MgATP levels might indeed account for a large part of the observed decline in background K+ channel activity that occurs upon metabolic inhibition.

Regulation of ion channels by ATP

ATP regulates the activity of a number of ion channels and transporters (Hilgemann, 1997). The best known example of functional regulation of cell excitability by cell metabolism is that mediated by the KATP channel. These channels control insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells in response to changes in glucose availability (Ashcroft, 1988) and regulate the activity of cardiac muscle during times of metabolic stress (Noma, 1983). The regulation of these channels is rather different to that described here in that KATP channel activity is inhibited by ATP. There are, however, other K+ channels that can either be stimulated by cytosolic ATP or for which spontaneous rundown upon patch excision can be slowed or reversed by cytosolic ATP (Kim, 1991; Fakler et al. 1994; Takumi et al. 1995; Hilgemann, 1997; Huang et al. 1998; Hughes & Takahira, 1998). In many cases this has been attributed to PIP2 generation by ATP-dependent lipid kinases (Hilgemann & Ball, 1996; Huang et al. 1998). The activity of Na+/Ca2+ exchange is also modulated by ATP-dependent PIP2 generation (Hilgemann & Ball, 1996; Hilgemann, 1997). The effect of ATP on Na+/Ca2+ exchange was not, however, mimicked by GTP, ADP or non-hydrolysable ATP analogues (Collins et al. 1992). Similarly the effect of ATP on atrial G-protein activated K+ channels (GIRK, IKAch) is not mimicked by non-hydrolysable ATP analogues or by ADP, or UTP (Kim, 1991). It would therefore appear that this pathway has a rather selective requirement for MgATP. Whilst we would not at this stage wish to exclude the possibility that the background-K+ channels of type-1 cells can be regulated by PIP2, particularly as there is evidence for such regulation in some cloned tandem-p-domain K+ channels (Lopes et al. 2005), the range of nucleotides that are effective in rapidly augmenting background K+ channel activity suggest a more direct, probably phosphorylation independent, form of control. Whilst there is some evidence of an additional non-PIP2-dependent mechanism by which GIRK channels might be regulated by ATP (Han et al. 2003), the channel that shows greatest similarity in its sensitivity to nucleotides to that reported here is another background K+ channel. Bovine adrenal cortical cells express a background K+ channel believed to be TREK-1 (Enyeart et al. 2002). This endogenous channel is strongly activated by ATP and a wide range of other nucleotides including GTP, UTP, ADP, ATP-γS and non-hydrolysable ATP analogues (Enyeart et al. 1997; Xu & Enyeart, 2001). This channel loses sensitivity to nucleotides in inside-out patches suggesting the presence of a regulatory factor that is only loosely associated with the channel. We are not aware of any published data showing cloned tandem-p-domain K+ channels to be intrinsically sensitive to nucleotides, or to possess identifiable nucleotide binding domains. We therefore presume that nucleotide sensitivity is probably conferred upon the type-1 cell background K+ channel by association with other proteins or via an intermediate, membrane delimited signalling pathway.

Summary

In the present study we have sought to evaluate the role that direct/membrane delimited pathways might play in linking changes in nucleotide levels to modulation of background K+ channel activity and to characterize the nucleotide specificity of this pathway. Our data lead us to the conclusion that changes in cytosolic, or more specifically submembrane, MgATP levels are likely to play a significant role in coupling cellular energy status to background K+ channel activity and thus to chemoreceptor excitability. This signalling pathway seems to have a fairly broad specificity with respect to the nucleotides that can activate it, which suggests that a low affinity Mg-nucleotide sensor may be coupled to the channel. Direct modulation by nucleotides may not, however, be the only link between energy metabolism and channel activity in these cells. Other, as yet unidentified, cytosolic factors also play a role in determining channel activity since significant rundown occurs upon patch excision even in the presence of high levels of MgATP. Until these factors are identified it is impossible to comment on whether they are also linked to energy metabolism. In addition there are two other signalling pathways that could also influence channel activity during periods of metabolic compromise. Adenosine has recently been shown to excite type-1 cells via A2A receptors (Xu et al. 2006) and an AMP-dependent kinase has been suggested to play a role in oxygen sensing (activated presumably via hypoxia induced decline in oxidative phosphorylation; Evans et al. 2005; Wyatt et al. 2007). It should be noted that the rise in Mg2+ reported here as signifying MgATP depletion also reflects the production of AMP which could serve both to activate AMP kinase and as substrate for adenosine production. Determining whether these other pathways regulate background K+ channel activity, and if so what their relative importance is, remains a challenge for the future. What is apparent from this study is that the direct MgATP sensitivity of background K+ channels alone could provide a sufficient mechanism for linking metabolism to cellular excitability and thus provide an explanation for the long known sensitivity of arterial chemoreceptors to metabolic inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the British Heart Foundation and the MRC.

References

- Abraham MR, Selivanov VA, Hodgson DM, Pucar D, Zingman LV, Wieringa B, Dzeja PP, Alekseev AE, Terzic A. Coupling of cell energetics with membrane metabolic sensing. Integrative signaling through creatine kinase phosphotransfer disrupted by M-CK gene knock-out. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24427–24434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201777200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DG, Morris PG, Orchard CH, Pirolo JS. A nuclear magnetic resonance study of metabolism in the ferret heart during hypoxia and inhibition of glycolysis. J Physiol. 1985;361:185–204. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anichkov S, Belen'kii M. Pharmacology of the Carotid Body Chemoreceptors. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft FM. Adenosine 5′-triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1988;11:97–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss DA, Talley EM, Sirois JE, Lei Q. TASK-1 is a highly modulated pH-sensitive ‘leak’ K+ channel expressed in brainstem respiratory neurons. Respir Physiol. 2001;129:159–174. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(01)00288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckler KJ. A novel oxygen-sensitive potassium current in rat carotid body type I cells. J Physiol. 1997;498:649–662. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckler KJ, Vaughan-Jones RD. Effects of hypercapnia on membrane potential and intracellular calcium in rat carotid body type I cells. J Physiol. 1994a;478:157–171. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckler KJ, Vaughan-Jones RD. Effects of hypoxia on membrane potential and intracellular calcium in rat neonatal carotid body type I cells. J Physiol. 1994b;476:423–428. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckler KJ, Vaughan-Jones RD. Effects of mitochondrial uncouplers on intracellular calcium, pH and membrane potential in rat carotid body type I cells. J Physiol. 1998;513:819–833. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.819ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckler KJ, Williams BA, Honore E. An oxygen-, acid- and anaesthetic-sensitive TASK-like background potassium channel in rat arterial chemoreceptor cells. J Physiol. 2000;525:135–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdakov D, Jensen LT, Alexopoulos H, Williams RH, Fearon IM, O'Kelly I, Gerasimenko O, Fugger L, Verkhratsky A. Tandem-pore K+ channels mediate inhibition of orexin neurons by glucose. Neuron. 2006;50:711–722. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Somlyo AV, Hilgemann DW. The giant cardiac membrane patch method: stimulation of outward Na+-Ca2+ exchange current by MgATP. J Physiol. 1992;454:27–57. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper BY, Johnson RD, Rau KK. Characterization and function of TWIK-related acid sensing K+ channels in a rat nociceptive cell. Neuroscience. 2004;129:209–224. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czirjak G, Fischer T, Spat A, Lesage F, Enyedi P. TASK (TWIK-related acid-sensitive K+ channel) is expressed in glomerulosa cells of rat adrenal cortex and inhibited by angiotensin II. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:863–874. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.6.0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly M de Burgh. Peripheral Arterial Chemoreceptors and Respiratory-Cardiovascular Integration, Monographs of the Physiological Society. Vol. 46. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Duchen MR, Biscoe TJ. Mitochondrial function in type I cells isolated from rabbit arterial chemoreceptors. J Physiol. 1992;450:13–31. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enyeart JJ, Gomora JC, Xu L, Enyeart JA. Adenosine triphosphate activates a noninactivating K+ current in adrenal cortical cells through nonhydrolytic binding. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:679–692. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.6.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enyeart JJ, Xu L, Danthi S, Enyeart JA. An ACTH- and ATP-regulated background K+ channel in adrenocortical cells is TREK-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49186–49199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207233200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erecinska M, Silver IA. Ions and energy in mammalian brain. Prog Neurobiol. 1994;43:37–71. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AM, Mustard KJ, Wyatt CN, Peers C, Dipp M, Kumar P, Kinnear NP, Hardie DG. Does AMP-activated protein kinase couple inhibition of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation by hypoxia to calcium signaling in O2-sensing cells? J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41504–41511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakler B, Brandle U, Glowatzki E, Zenner HP, Ruppersberg JP. Kir2.1 inward rectifier K+ channels are regulated independently by protein kinases and ATP hydrolysis. Neuron. 1994;13:1413–1420. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90426-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon IM, Zhang M, Vollmer C, Nurse CA. GABA mediates autoreceptor feedback inhibition in the rat carotid body via presynaptic GABAB receptors and TASK-1. J Physiol. 2003;553:83–94. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.048298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidone SJ, Gonzalez C. Initiation and control of chemoreceptor activity in the carotid body. In: Cherniack NS, Widdicombe JG, editors. Handbook of Physiology, section 3, The Respiratory System, Control of Breathing. II. Bethesda: American Physiological Society; 1986. pp. 247–312. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C, Almaraz L, Obeso A, Rigual R. Carotid body chemoreceptors: from natural stimuli to sensory discharges. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:829–898. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.4.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubbs RD. Intracellular magnesium and magnesium buffering. Biometals. 2002;15:251–259. doi: 10.1023/a:1016026831789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Kang D, Kim D. Properties and modulation of the G protein-coupled K+ channel in rat cerebellar granule neurons: ATP versus phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J Physiol. 2003;550:693–706. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.042119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Truell J, Gnatenco C, Kim D. Characterization of four types of background potassium channels in rat cerebellar granule neurons. J Physiol. 2002;542:431–444. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.017590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymans C, Bouckaert JJ, Dautrebande L. Sinus carotidien et reflexes respiratoires: sensibilite des sinus carotidiens aux substances chimiques. Action stimulante respiratoire reflexe du sulfure de sodium, du cyanure de potassium, de la nicotine et de la lobeline. Archives Internationales de Pharmacodynamie et de Therapie. 1931;40:54–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann DW. Cytoplasmic ATP-dependent regulation of ion transporters and channels: mechanisms and messengers. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:193–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann DW, Ball R. Regulation of cardiac Na+,Ca2+ exchange and KATP potassium channels by PIP2. Science. 1996;273:956–959. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CL, Feng S, Hilgemann DW. Direct activation of inward rectifier potassium channels by PIP2 and its stabilization by Gβγ. Nature. 1998;391:803–806. doi: 10.1038/35882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes BA, Takahira M. ATP-dependent regulation of inwardly rectifying K+ current in bovine retinal pigment epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1998;275:C1372–C1383. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.5.C1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Fujishiro N, Imanaga I. Hypoxia and cyanide induce depolarization and catecholamine release in dispersed guinea-pig chromaffin cells. J Physiol. 1998;507:807–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.807bs.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D, Han J, Talley EM, Bayliss DA, Kim D. Functional expression of TASK-1/TASK-3 heteromers in cerebellar granule cells. J Physiol. 2004;554:64–77. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.054387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. Modulation of acetylcholine-activated K+ channel function in rat atrial cells by phosphorylation. J Physiol. 1991;437:133–155. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Bang H, Kim D. TBAK-1 and TASK-1, two-pore K+ channel subunits: kinetic properties and expression in rat heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;277:H1669–H1678. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.5.H1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I, Kim JH, Carroll JL. Postnatal changes in gene expression of subfamilies of TASK K+ channels in rat carotid body. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;580:43–47. doi: 10.1007/0-387-31311-7_7. discussion 351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyssens A, Nowicky AV, Patterson L, Crompton M, Duchen MR. The relationship between mitochondrial state, ATP hydrolysis, [Mg2+]i and [Ca2+]i studied in isolated rat cardiomyocytes. J Physiol. 1996;496:111–128. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes CM, Rohacs T, Czirjak G, Balla T, Enyedi P, Logothetis DE. PIP2 hydrolysis underlies agonist-induced inhibition and regulates voltage gating of two-pore domain K+ channels. J Physiol. 2005;564:117–129. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.081935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maingret F, Patel AJ, Lazdunski M, Honore E. The endocannabinoid anandamide is a direct and selective blocker of the background K+ channel TASK-1. EMBO J. 2001;20:47–54. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar JA, Barratt L, Southan AP, Page KM, Fyffe RE, Robertson B, Mathie A. A functional role for the two-pore domain potassium channel TASK-1 in cerebellar granule neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3614–3618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050012597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoro RJ, Urena J, Fernandez Chacon R, Alvarez de Toledo G, Lopez Barneo J. Oxygen sensing by ion channels and chemotransduction in single glomus cells. J Gen Physiol. 1996;107:133–143. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan E, Lahiri S. Dependence of carotid chemoreceptor stimulation by metabolic agents on PaO2 and PaCO2. J Appl Physiol. 1981;50:884–891. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.50.4.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan E, Lahiri S, Storey BT. Carotid body O2 chemoreception and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. J Appl Physiol. 1981;51:438–446. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.51.2.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noma A. ATP-regulated K+ channels in cardiac muscle. Nature. 1983;305:147–148. doi: 10.1038/305147a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeso A, Almaraz L, Gonzalez C. Correlation between adenosine triphosphate levels, dopamine release and electrical activity in the carotid body: support for the metabolic hypothesis of chemoreception. Brain Res. 1985;348:64–68. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90360-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeso A, Almaraz L, Gonzalez C. Effects of 2-deoxy-D-glucose on in vitro cat carotid body. Brain Res. 1986;371:25–36. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90806-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeso A, Almaraz L, Gonzalez C. Effects of cyanide and uncouplers on chemoreceptor activity and ATP content of the cat carotid body. Brain Res. 1989;481:250–257. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90801-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeso A, Gonzalez C, Rigual R, Dinger B, Fidone S. Effect of low O2 on glucose uptake in rabbit carotid body. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:2387–2393. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.5.2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olschewski A, Li Y, Tang B, Hanze J, Eul B, Bohle RM, Wilhelm J, Morty RE, Brau ME, Weir EK, Kwapiszewska G, Klepetko W, Seeger W, Olschewski H. Impact of TASK-1 in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2006;98:1072–1080. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000219677.12988.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega Saenz P, Pardal R, Garcia Fernandez M, Lopez Barneo J. Rotenone selectively occludes sensitivity to hypoxia in rat carotid body glomus cells. J Physiol. 2003;548:789–800. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.039693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardal R, Lopez Barneo J. Low glucose-sensing cells in the carotid body. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:197–198. doi: 10.1038/nn812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peers C. Hypoxic suppression of K+ currents in type I carotid body cells: selective effect on the Ca2+-activated K+ current. Neurosci Lett. 1990;119:253–256. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90846-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peers C, Green FK. Inhibition of Ca2+-activated K+ currents by intracellular acidosis in isolated type I cells of the neonatal rat carotid body. J Physiol. 1991;437:589–602. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peers C, O'Donnell J. Potassium currents recorded in type I carotid body cells from the neonatal rat and their modulation by chemoexcitatory agents. Brain Res. 1990;522:259–266. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91470-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peers C, Wyatt CN. The role of maxiK channels in carotid body chemotransduction. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;157:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar NR. O2 sensing at the mammalian carotid body: why multiple O2 sensors and multiple transmitters? Exp Physiol. 2006;91:17–23. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.031922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich TC, Fagan KA, Nakata H, Schaack J, Cooper DM, Karpen JW. Cyclic nucleotide-gated channels colocalize with adenylyl cyclase in regions of restricted cAMP diffusion. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:147–161. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong W, Gourine AV, Cockayne DA, Xiang Z, Ford AP, Spyer KM, Burnstock G. Pivotal role of nucleotide P2X2 receptor subunit of the ATP-gated ion channel mediating ventilatory responses to hypoxia. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11315–11321. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-36-11315.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi DJ, Oshima T, Attwell D. Glutamate release in severe brain ischaemia is mainly by reversed uptake. Nature. 2000;403:316–321. doi: 10.1038/35002090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomig A. Catecholamines in myocardial ischemia. Systemic and cardiac release. Circulation. 1990;82:Ii13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selivanov VA, Alekseev AE, Hodgson DM, Dzeja PP, Terzic A. Nucleotide-gated KATP channels integrated with creatine and adenylate kinases: amplification, tuning and sensing of energetic signals in the compartmentalized cellular environment. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;256–257:243–256. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000009872.35940.7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen TCR, Hauss WH. Influence of dinitrophenol, dinitroortocresol and paranitrophenol upon the carotid sinus chemoreceptors of the dog. Archives Internationales de Pharmacodynamie et de Therapie. 1939;63:251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Takumi T, Ishii T, Horio Y, Morishige K, Takahashi N, Yamada M, Yamashita T, Kiyama H, Sohmiya K, Nakanishi S, et al. A novel ATP-dependent inward rectifier potassium channel expressed predominantly in glial cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16339–16346. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.27.16339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley EM, Lei Q, Sirois JE, Bayliss DA. TASK-1, a two-pore domain K+ channel, is modulated by multiple neurotransmitters in motoneurons. Neuron. 2000;25:399–410. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80903-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley EM, Solorzano G, Lei Q, Kim D, Bayliss DA. CNS distribution of members of the two-pore-domain (KCNK) potassium channel family. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7491–7505. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07491.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verna A, Talib N, Roumy M, Pradet A. Effects of metabolic inhibitors and hypoxia on the ATP, ADP and AMP content of the rabbit carotid body in vitro: the metabolic hypothesis in question. Neurosci Lett. 1990;116:156–161. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90402-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn CP, Bayliss DA, Guyenet PG. Cardiorespiratory neurons of the rat ventrolateral medulla contain TASK-1 and TASK-3 channel mRNA. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2003;138:19–35. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(03)00185-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn CP, Sirois JE, Talley EM, Guyenet PG, Bayliss DA. Serotonergic raphe neurons express TASK channel transcripts and a TASK-like pH- and halothane-sensitive K+ conductance. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1256–1265. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01256.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BA, Buckler KJ. Biophysical properties and metabolic regulation of a TASK-like potassium channel in rat carotid body type 1 cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L221–L230. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00010.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt CN, Buckler KJ. The effect of mitochondrial inhibitors on membrane currents in isolated neonatal rat carotid body type I cells. J Physiol. 2004;556:175–191. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt CN, Mustard KJ, Pearson SA, Dallas ML, Atkinson L, Kumar P, Peers C, Hardie DG, Evans AM. AMP-activated protein kinase mediates carotid body excitation by hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8092–8098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608742200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Enyeart JJ. Properties of ATP-dependent K+ channels in adrenocortical cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C199–C215. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.1.C199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Xu J, Tse FW, Tse A. Adenosine stimulates depolarization and rise in cytoplasmic [Ca2+] in type I cells of rat carotid bodies. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1592–C1598. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00546.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Kummer W, Atoji Y, Suzuki Y. TASK-1, TASK-2, TASK-3 and TRAAK immunoreactivities in the rat carotid body. Brain Res. 2002;950:304. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Taniguchi K. Expression of tandem P domain K+ channel, TREK-1, in the rat carotid body. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:467–472. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6755.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Zhong H, Vollmer C, Nurse CA. Co-release of ATP and ACh mediates hypoxic signalling at rat carotid body chemoreceptors. J Physiol. 2000;525:143–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00143.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]