Abstract

Calcium-dependent gating of the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channel is conferred by the large cytosolic carboxyl terminus containing two domains of the regulator of K+ conductance (RCK) and the high-affinity Ca2+-binding site (the Ca2+-bowl). In our previous study, we located the putative second RCK domain (RCK2) and demonstrated that it interacts directly with RCK1 via a hydrophobic “assembly interface”. In this study, we tested the structural model of the other interface, the “flexible interface”, by strategically positioning charge pairs across the putative interface. Several charge mutations on RCK2 affected the voltage-dependent activation of the channel. In particular, the Gly-to-Asp substitution at position 803 profoundly affected channel activation by stabilizing the open conformation of the channel with minimal effects on its Ca2+ affinity and voltage sensitivity. Various mutations at Gly-803 shifted the channel's conductance-voltage curve either left or right over a 145-mV range. Since this residue is predicted to be in the first loop of RCK2 these results strongly suggest that this loop plays a critical role in determining the intrinsic equilibrium constant for channel opening, and they support the hypothesis that this loop is part of an interface that mediates conformational coupling between RCK1 and RCK2.

INTRODUCTION

Large-conductance calcium-activated potassium (BKCa) channels play an important role in modulating a number of physiological processes, such as neuronal excitability, smooth-muscle contraction, frequency tuning of hair cells, and immunity (1–8). The opening of these channels is promoted by membrane depolarization and elevated cytosolic free calcium via separate regions of the α-subunit (Slowpoke or Slo) (9–12). The positive charges on transmembrane domains (S1–S4) are responsible for voltage sensing (13–19), whereas the calcium-dependent activation of the channel is mediated by the bulky cytoplasmic carboxy terminus (20–22). The cytoplasmic C-terminus of Slo has been proposed to contain a high-affinity Ca2+-binding site (Ca2+-bowl) and a structural module known as the regulator of K+ conductance (RCK) domain (21,23–28). The Ca2+-bowl is composed of a series of Asp residues and binds Ca2+ with micromolar affinity. Mutations here have been shown to cause positive shifts in the Slo channel's conductance-voltage relationship at constant Ca2+ concentrations (21,22,25,26,29,30). Recognized initially in a Ca2+-activated K+ channel of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (MthK), a double ring composed of eight RCK domains (gating ring) has been studied intensively as a model for Ca2+-dependent channel gating (31). Based on sequence homology and supporting experimental evidence, two RCK domains have been proposed to lie in tandem within the long C-terminus of the mammalian BKCa channel (23,32–34). The first RCK domain (RCK1), located at the proximal C-terminus of the Slo protein, has been characterized in detail using mutational analysis. RCK1 contains two divalent-cation-binding sites with high and low affinity for Ca2+, respectively (26–28). A gain-of-function mutation that causes epileptic seizures has also been localized to RCK1 (35). In the exogenously expressed mutant channel, the calcium sensitivity was found to increase by three- to fivefold over the wild-type and the conductance-voltage (G-V) relationship was shifted toward more negative potentials by 57 mV. The second RCK domain (putative RCK2), which is essential for Ca2+-dependent gating of the channel, is located in the distal region of the C-terminus and is immediately followed by the Ca2+-bowl. Recently, we reported that hydrophobic interactions between RCK1 and the putative RCK2 are essential for the gating of the channel. This interaction is reminiscent of the fixed (assembly) interface between the two RCK domains within the gating ring of MthK (23). It was also suggested that the dimeric pairs of RCK domains on a single subunit are responsible for cooperative activation of BKCa channels by calcium (36).

In a search for important amino acid residues for channel activation in the putative RCK2, we mutagenized several residues located in the region corresponding to the flexible interface as revealed in the crystal structure of the MthK gating ring. Among the mutant channel, an Asp substitution at Gly-803 greatly enhanced channel activity as evidenced by as much as an 80-mV shift in the G-V curve toward a more negative potential. This potentiation can be explained by a stabilization of the open conformation that neither leads to a change in Ca2+ affinity nor a change in voltage sensitivity. The residue is predicted to be located at the interface between RCK1 and the putative RCK2, suggesting that the region of the putative RCK2 that interfaces with RCK1 is important for determining the energetics of the conformational changes that lead to channel opening. This region may mediate the conformational coupling between downstream Ca2+ binding at the Ca2+-bowl and the upstream RCK1 and transmembrane domains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression of Slo channels in Chinese hamster ovary cells

All electrophysiological experiments, except for the gating-current measurements, were performed on Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1 cells expressing the rat Slo channel gene (GenBank accession No. AF135265) (37). CHO-K1 cells were maintained in F-12K nutrient mixture, Kaighn's modification (GIBCO, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), in a humidified atmosphere at 5% CO2 and 37°C. To obtain high-quality plasmid DNA for transient transfection, the plasmid DNA was prepared using a commercial kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Expression of Slo channels in Xenopus oocytes

To measure the gating current, wild-type and mutant rSlo channels were expressed in Xenopus oocytes. We used complementary DNA for rSlo subcloned into a modified pGH expression vector for high-level expression. Complementary RNAs for the rSlo channel were synthesized in vitro using T7 RNA polymerase (Ambion, Austin, TX) and plasmids were linearized with NotI. Approximately 150–200 ng of cRNA were injected into oocytes. The injected oocytes were incubated at 18°C for 4–8 days in ND96 solution.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the Slo channel

Silent mutations were introduced at amino acid positions 728, 729, and 1016 of rSlo (GenBank accession No. GI:4972782) using two sequential polymerase chain reactions to create AgeI (from ACTGGA to ACCGGT) and XhoI (from CTCGAA to CTCGAG) restriction sites. Cassette mutagenesis was performed to substitute specific amino acid residues. Mutations were generated by polymerase chain reaction using mutagenic primers. The amplified DNA fragments flanked by AgeI and XhoI were substituted for the wild-type rSlo gene cloned into the pcDNA3.1(+) vector using BamHI and XbaI restriction sites. To confirm the DNA sequence of each mutant channel, DNA sequencing was performed using an ABI 377 automatic DNA sequencer (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Foster City, CA).

Electrophysiological recordings and data analysis

Most of the macroscopic ionic currents carried by wild-type and mutant rSlo channels were recorded in excised membrane patches of CHO-K1 cells with inside-out configurations using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA). All patch recordings were performed at room temperature 24–48 h after transfection. Pipettes were prepared from thin-walled borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) and fire-polished. Macroscopic currents of rSlo channels were activated by voltage pulses delivered from a holding potential of −100 mV to test potentials ranging from −150 to 200 mV in 10-mV increments. When filled with the solutions described below, the input resistances of electrodes for macroscopic currents were 2.5–3.5 MΩ, whereas for single-channel recording they were >4.0 MΩ. Average series resistance, ∼2.9 MΩ, was used to compensate electronically for the macroscopic recordings. Signals were filtered at 1–2 kHz using a four-pole low-pass Bessel filter, digitized at a rate of 10 kHz using a Digidata 1200 (Axon Instruments), and stored in a personal computer. Commercial software packages such as Clampex 8.1 (Axon Instruments) and Origin 6.1 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA) were used for the acquisition and analysis of macroscopic data.

Single-channel opening events were obtained from patches containing one to hundreds of channels. Recordings were obtained for durations of 20 to hundreds of seconds. Unitary currents were sampled at 200 kHz and filtered at 10 kHz. Analysis was performed using the Clampfit program (Axon Instruments). In the limiting PO measurements, open probabilities <10−3 were determined at 0 [Ca2+] with patches that contained hundreds of channels. The number of channels in a given patch (N) was obtained from the instantaneous tail current amplitude during maximal opening at saturating [Ca2+]i divided by the unitary conductance for each channel at the tail voltage.

For the gating-current measurements, patch pipettes were made of borosilicate glass (VWR, West Chester, PA) and their tips were coated with sticky wax (Sticky Wax, Dharma Trading, San Rafael, CA) and fire-polished to a resistance of 0.5–1 MΩ. Voltage commands were filtered at 7.5 kHz. Data were acquired at 100 kHz and filtered at 10 kHz with an Axopatch 200B amplifier and a Macintosh-based computer system equipped with an ITC-16 hardware interface (Instrutech, Port Washington, NY) and pulse-acquisition software (HEKA Electronik, Southboro, MA). Data analysis was performed with Igor Pro graphing and curve-fitting software (WaveMetrics, Oswego, OR).

Solutions for macroscopic ionic-current recording were prepared according to Lim and Park (38). Pipette solutions contained 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM EGTA, 116 mM KOH, and 4 mM KCl. The intracellular solution for perfusing to the internal face of excised patches was the same as the pipette solution except for supplemental CaCl2. To provide the precise free concentration of intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i), the appropriate amount of total Ca2+ to be added to the intracellular solution was calculated using the program MaxChelator (39). The pH was adjusted to 7.2 with 2-[N-morpholino]ethanesulfonic acid. Gating-current recording solutions were prepared according to Bao and Cox (40). The composition of the pipette solution was 127 mM triethylammonium-OH, 125 mM HMeSO3, 2 mM HCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.2 (adjusted with HMeSO3 or triethylammonium-OH). The internal solution contained 141 mM N-methyl-D-glucamine, 135 mM HMeSO3, 6 mM HCl, 20 mM HEPES, 40 μM (+)-18-crown-6-tetracarboxylic acid (18C6TA), 5 mM EGTA, pH 7.2 (adjusted with NMDG and HMeSO3).

RESULTS

Functional effects of engineered charge pairs across the putative flexible interface between RCK1 and RCK2

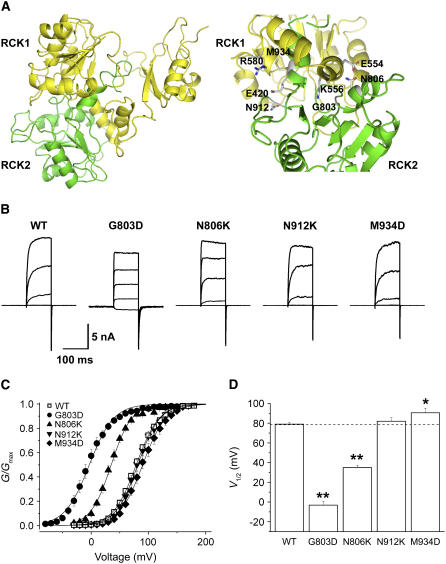

On the basis of the gating ring structure of MthK, we constructed a heterodimeric structural model of the Slo channel's putative flexible interface between RCK1 and RCK2 (Fig. 1 A, left). Although the flexible interfaces of the homomeric RCK dimers in MthK are formed by two helices from each RCK domain's N-terminal lobe (αF and αG), and also parts of their C-terminal lobes (23), our model of the Slo channel's heterodimeric RCK dimer predicts that RCK1 interacts with RCK2 mainly through αF helices. This is because of the apparent absence of an αG helix and a C-terminal lobe in the putative RCK2. We surveyed the amino acid residues at the contact sites in our model between RCK1 and RCK2, and residues of the putative RCK2 that appeared to be in close proximity to charged residues in RCK1 were identified (Fig. 1 A, right). We, then, substituted each interfacial residue of the putative RCK2 with a residue that had the counter charge of the one in RCK1 to create a charge pair across the interface.

FIGURE 1.

Effects of charge mutations at the putative flexible interface of between RCK1 and the putative RCK2 in BKCa channel. (A) Structural model of RCK1-2 dimer interacting via putative flexible interface (left). RCK1 and the putative RCK2 domains are denoted yellow and green, respectively. Several charged residues in RCK1 and their adjacent residues in the putative RCK2 are shown with stick in enlarged dimeric interface (right). (B) Representative raw traces of wild-type and mutant channels. In mutant channels, each interfacial residue in the putative RCK2 was substituted with countercharged residues of adjacent residue in RCK1. Ionic currents were induced by voltage steps ranging from −20 to 140 mV in 40-mV increments from the holding voltage of −100 mV. (C) The conductance-voltage (G-V) relationships of the wild-type (open symbols) and several mutant channels (solid symbols) are shown. The symbols for each mutant channel are indicated in the inset. Each channel was recorded with 2 μM [Ca2+]i. The curves were fitted with the Boltzmann function. (D) The half-activation voltage (V1/2) of the wild-type and mutant channels were determined at 2 μM [Ca2+]i. The V1/2 of the wild-type is indicated as a dotted line. Each data point represents the mean ± SE. Values differing from the wild-type by the paired Student's t-test at p < 0.05 (*) or p < 0.01 (**) are indicated.

The wild-type channel and each mutant were expressed in CHO-K1 cells, and their functional activities were investigated electrophysiologically. Fig. 1 B shows representative macroscopic currents from each channel type, evoked by a common voltage protocol in the presence of 2 μM [Ca2+]i. As is evident, the mutations showed varied effects. In Fig. 1 C, the steady-state extent of activation of the four mutant channels is plotted as a function of voltage and these plots compared with wild-type. The G-V relations of the G803D and N806K mutants were strongly shifted toward more negative voltages, whereas the G-V relation of M934D was slightly shifted in a positive direction. Compared to the half-activation voltage (V1/2) of the wild-type channel, 79 mV, the V1/2 values of the G803D and N806K mutants were −3 mV and 34 mV, respectively (Fig. 1 D), which correspond to shifts of 82 and 45 mV in the negative direction. Despite the fact that the mutants' G-V curves were spread across an ∼90-mV range, the slope of each G-V curve representing the apparent voltage dependence of the channel activation was not altered significantly. The apparent gating charges determined from the slope of each activation curve are as follows: for wild-type, 1.31e ± 0.07; for G803D, 1.38e ± 0.06; for N806K, 1.47e ± 0.04; for N912K, 1.41e ± 0.08; for M934D, 1.38e ± 0.06.

Ca2+-independent parallel shifts of the G-V relation in G803D mutant channel

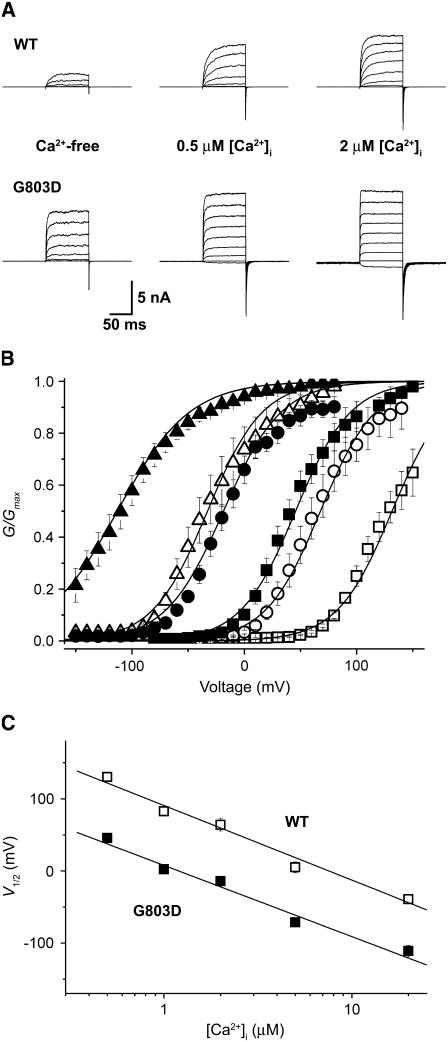

As we were intrigued by the dramatic G-V shift generated by the Gly-to-Asp mutation at position 803, we scrutinized the mutant channel for insights into the mechanism involved. As shown in Fig. 2 A, the ionic currents of G803D were activated at more negative voltages and at lower concentrations of intracellular Ca2+ than were those of the wild-type channel. The G-V relationships of the wild-type channel (open symbols) and the mutant (solid symbols) are plotted at 0.5 μM (rectangles), 2 μM (circles), and 20 μM (triangles) [Ca2+]i in Fig. 2 B. At all three [Ca2+]i the mutation negatively shifted the G-V curve by ∼80 mV. We then quantified the effects of intracellular Ca2+ on the position of the mutant's G-V relationship by plotting V1/2 vs. [Ca2+]i for [Ca2+]i ranging from 0.5 to 20 μM. In the semilogarithmic plot shown in Fig. 2 C, the V1/2 values of both the wild-type and mutant channels were found to be linearly related to [Ca2+]i; however, the G-to-D mutation shifted the V1/2 value of the each G-V curve by −78 mV at all [Ca2+]i tested.

FIGURE 2.

Functional analysis of the G803D mutant channel. (A) Representative macroscopic current traces of the wild-type and G803D mutant recorded at different [Ca2+]i are shown. The concentrations of intracellular calcium are indicated. Ionic currents were induced by voltage steps ranging from −20 to 140 mV at 20-mV increments from the holding voltage of −100 mV. Current traces represent an average of three successive records. (B) The G-V relationships of the wild-type (n = 14) and G803D mutant (n = 11) are shown for 0.5 μM (rectangles), 2 μM (circles), and 20 μM (triangles) [Ca2+]i. The wild-type and G803D are indicated by open and solid symbols, respectively. Each data set was fitted with the following equation: G/Gmax = 1/[1 + {(1 + [Ca2+]/KC)/(1 + [Ca2+]/KO)}4 × exp(−QFV/RT)/L0], where KC is the dissociation constant of [Ca2+] in the closed state, KO is the dissociation constant of [Ca2+] in the open state, Q represents the equivalent gating charge associated with this equilibrium, and L0 is the [O]/[C] at 0 [Ca2+]i. (C) Relationship between [Ca2+]i and the half-activation voltages. Open and solid symbols denote the wild-type and G803D, respectively. Each data point represents the mean ± SE.

To address which aspects of Slo-channel gating were altered by the G-to-D substitution in the putative RCK2 domain, we simulated our experimental data based on the simple voltage-dependent version of the Monod-Wyman-Changeux (MWC) model previously proposed as a gating model for the BKCa channel (41). In this model, there are several simplifying assumptions. The channel is a homotetramer containing four Ca2+-binding sites, one on each subunit. Ca2+ can bind to both the open and closed conformations but it favors the open conformation, and thereby promotes the opening. The voltage sensors from each subunit move in a highly concerted way such that their movement can be represented by a single voltage-dependent conformational change. Four different parameters obtained from the simulation were compared between the wild-type and G803D (Table 1). Three parameters were not significantly affected (i.e., the apparent gating charge (Q), and the affinities for Ca2+ in the closed state (KC) and the open state (KO)), however, the close-to-open equilibrium constant in the absence of bound Ca2+ at 0 mV, L0, was altered dramatically from 8.6 × 10−4 to 0.021. The results of our simulation suggest that the substitution of Asp at position 803 alters the equilibrium constant for channel opening by 24-fold.

TABLE 1.

Parameters of the voltage-dependent MWC model for the wild-type and G803D

| Parameter | WT | G803D |

|---|---|---|

| L0 | 8.6 × 10−4 ± 3.0 × 10−5 | 0.021 ± 0.002 |

| KO | 0.931 ± 0.066 | 0.743 ± 0.048 |

| KC | 13.7 ± 1.5 | 11.1 ± 1.7 |

| Q | 1.16 ± 0.04 | 1.18 ± 0.04 |

Frequent opening of single G803D channels in the absence of Ca2+

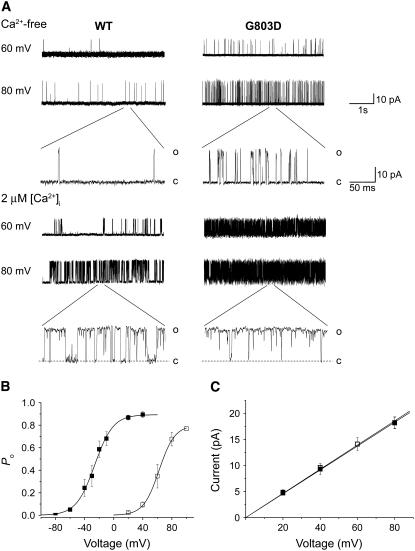

The potentiating effects of the G803D mutation were then examined at the single-channel level. Single-channel current traces of the wild-type channel and G803D were compared in the absence and presence of 2 μM [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3 A). As predicted from our analysis of macroscopic currents, the mutant channel opened more frequently than did the wild-type channel, even in the absence of Ca2+. And, at 2 μM Ca2+, where the wild-type channel exhibited significant opening, G803D always displayed a higher open probability (see the expanded timescale in Fig. 3 A).

FIGURE 3.

Effects of the Gly-to-Asp substitution on single-channel characteristics. (A) Representative current traces of single wild-type and G803D mutant channels recorded at two different voltages and [Ca2+]i. The scales for both the current and time are the same for the wild-type and mutant channels. Portions of the current traces are presented in an expanded timescale. The current levels of the single open state (O) and closed state (C) are indicated. (B) The open probability of the wild-type (□) and G803D (▪) were plotted against the membrane voltage at which the single-channel recordings were obtained. Intracellular calcium was set at 2 μM throughout. Each data set was fitted by the Boltzmann function. (C) The single-channel current amplitudes were plotted against membrane voltage. Single-channel currents were obtained by fitting the all-point histograms to the Gaussian function. The unitary conductances estimated from the linear fit of each slope were 232 ± 3 pS for the wild-type and 229 ± 3 pS for G803D.

The open probabilities (PO) of the wild-type and the mutant channel were plotted against membrane voltage in Fig. 3 B. The PO of both channels increased as the membrane potential was set to more positive values. However, the wild-type channel was activated in the voltage range of 20–100 mV, whereas the G803D channel was activated at far lower voltages, between −80 and 40 mV. Thus, the mutation negatively shifts the rSlo channel's PO versus voltage curve by 88.6 mV (Fig. 3 B). This shift is similar to the G-V shift we observed with macroscopic current recordings, 82 mV (Fig. 2 B). Despite its large effects on gating, the mutation did not affect the single-channel conductance of the rSlo channel. When we plotted the current amplitudes obtained from all-point histograms at different membrane voltages, the unitary conductances of the wild-type channel and G803D mutant were determined to be 232 ± 3 pS and 229 ± 3 pS, respectively (Fig. 3 C).

Effects of G803D on the intrinsic gating equilibrium

Since the simulation of the macroscopic current recordings suggested a significant shift in the intrinsic gating equilibrium of the G803D mutant channel, we directly determined the equilibrium constants for the intrinsic close-to-open conformational change for both channels by measuring open probability (PO) at hyperpolarized membrane potentials. According to the Horrigan et al. model (43–45), at extreme negative voltages, where no voltage sensors are active, PO = L0exp(zLFV/RT), which can be rearranged to log (PO) = 0.4342zLFV/RT + log(L0) (40,46), where L0 represents the equilibrium constant between closed and open at 0 mV in the absence of Ca2+ when no voltage sensors are active, zL is a small amount of gating charge associated with the closed-to-open conformational change, and F, R, and T have their usual meanings. This equation can be interpreted to mean that, as the membrane voltage becomes more and more hyperpolarized, a plot of log(PO)-voltage will reach a limiting slope that is less than its maximum slope and reflects the voltage dependence of just the close-open conformational change, zL. That is, in this voltage range, the slope of the log(PO)-voltage relation will be determined only by zL, and the position of the curve in the vertical axis will be determined only by L0. Thus, we can directly estimate zL and L0 by determining the PO versus voltage relation at far negative voltages. Here, it is important to note that the L0 value is defined differently from the L0 simulated with the voltage-dependent MWC model (Table 1). Whereas the L0 parameter in the voltage-dependent MWC model represents the equilibrium constant between open and closed at 0 mV in the absence of Ca2+, the L0 value obtained from limiting slope measurements represents the equilibrium constant between open and closed at 0 mV in the absence of Ca2+ if no voltage sensors are active (42). Thus, the L0 parameter in the simple voltage-dependent MWC model includes L0 as defined by Horrigan and Aldrich but also factors that depend on voltage sensor activation (43–45).

We measured PO for the wild-type channel and the G803D mutant over a wide range of voltages at 0 [Ca2+]i and determined the effects of the mutation on intrinsic and voltage-dependent gating. For the wild-type channel, PO values between −150 and +60 mV were measured using single-channel recordings, and PO values between +70 and +200 mV were obtained from macroscopic recordings. In the case of the G803D mutant, single-channel recordings were used for voltages between −150 and +20 mV and macroscopic recordings were used for voltages between +30 and +200 mV. Examples of single-channel recordings are shown in Fig. 4 A. Notice at each voltage the G803D mutant opens more frequently than does the wild-type channel. In Fig. 4 B, log(PO)-voltage relations for the wild-type and mutant channels are compared. As the voltage becomes more negative, both plots deviate from linear. The wild-type curve deviates at around −30 mV, and reaches a limiting slope by −110 mV. By fitting just the most negative part of this curve, L0 and zL were calculated to be 8.69 × 10−7 and 0.3e, respectively. The slope of the mutant channel's log(PO)-voltage relation deviates from linear at around −70 mV and approaches a limiting slope near −140 mV. The values of L0 and zL for the mutant channel were by the same analysis determined to be 2.04 × 10−5 and 0.64e, respectively. Thus, this analysis suggests that the Gly-to-Asp mutation stabilized the open state of the channel by 23-fold, a number very similar to that which we obtained with voltage-dependent MWC modeling, 24-fold (Table 1). Thus, we can assume that most of the mutation's effects on gating come from its effect on the intrinsic energetics of channel opening, rather than on Ca2+ binding or voltage sensor movement.

FIGURE 4.

Estimation of L0 and zL from open probability (PO) at negative voltages. (A) Unitary currents were recorded at 0 Ca2+ from the wild-type and G803D channels. Each patch contains 2,768 channels of wild-type and 2,664 channels of G803D channels. (B) Mean log(PO)-voltage relations are shown for the wild-type (□) and G803D (•) channel. Linear fits of log (PO)-V relation at the “steep phase” (dashed line) indicate that the measurements either have reached or are approaching the limiting slope. The dashed line represents best fits to the Boltzmann function. The solid line at the bottom of the data point was fitted with the following function: log(PO) = log(L0) + 0.4342zLFV/RT. The resulting parameters were L0 = 8.69 × 10−7 and zL = 0.3e for the wild-type, and L0 = 2.04 × 10−5 and zL = 0.64e for G803D.

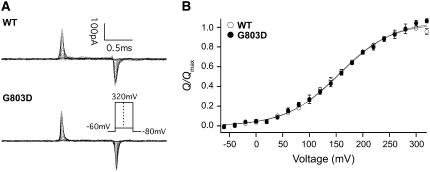

Lack of mutational effects on the voltage sensor and voltage sensing

As a member of the voltage-gated ion-channel superfamily, the BKCa channel senses the membrane voltage by moving its voltage sensor within the S2–S4 segment of the α-subunit (19). Membrane depolarization drives the outward movement of the positively charged voltage sensor and evokes outward or “on-gating” currents, whereas membrane hyperpolarization generates inward or “off-gating” currents. To check whether the G803D mutation brings about any changes in other measurable gating parameters, we examined directly the effect of the mutation on voltage sensor movement by measuring gating currents from both wild-type and G803D channels. The ON- and OFF-gating currents of both channel types were measured at membrane voltages between −60 and +320 mV with 1-ms voltage steps (Fig. 5 A). Gating charge displacement was determined by integrating the ON-gating current of each trace, and plots of charge displaced (Q) versus voltage are displayed in Fig. 5 B normalized to their maxima. As is evident the Q-V curves of the wild-type channel and the G803D mutant are superimposable, with half-activation voltages of 154 mV (wild-type) and 158 mV (G803D), and apparent gating charges per voltage senor of 0.52 (wild-type) and 0.50 (G803D). This result indicates that the G-to-D mutation in the putative RCK2 domain insignificantly affects voltage sensor movement in response to changes in voltage and therefore that the negative shift in the rSlo G-V (and PO-V) relationship caused G803D at all [Ca2+]i is not due to changes in voltage sensing. Furthermore, combined with the data in Fig. 2 and, discussed above, it strongly suggests that G803D alters predominately, if not exclusively, the intrinsic equilibrium constant for channel opening.

FIGURE 5.

Gating currents of the wild-type and G803D mutant channels. (A) Representative traces of gating currents recorded for the wild-type and G803D mutant channels in the absence of internal Ca2+ are shown. (B) Normalized averaged Q-V relations for the wild-type (average of 12, ○) and G803D (average of 6, •). Each curve was fitted with the Boltzmann function. The fit parameters were as follows: for the wild-type, z = 0.519 ± 0.013e, V1/2 = 154 ± 1.8 mV; for G803D, z = 0.499 ± 0.013e, V1/2 = 158 ± 1.5 mV. Each data point represents the mean ± SE.

Modulation of the rSlo G-V position by mutation at amino acid 803

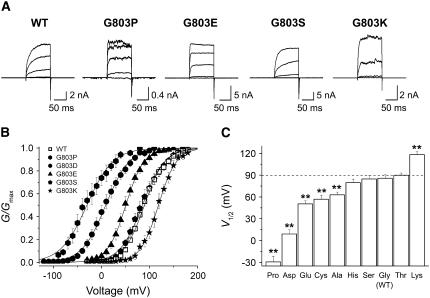

To find out how other amino acid residues at position 803 affect the gating properties of the Slo channel, we replaced Gly-803 with various amino acids. As expected all mutant channels evoked K+ currents in response to membrane depolarization or increases in intracellular Ca2+, but there were large differences in expression level among the mutant channels (Fig. 6 A). Whereas some mutants, i.e., G803D and G803E, produced macroscopic currents comparable to wild-type, others, including G803P, evoked much smaller currents. Substitution of Gly-803 with hydrophobic residues, for example, G803F and G803L, did not generate enough K+ current for accurate and reproducible recordings. Moreover, different substitutions at G803 gave rise to markedly different effects on channel activation. In Fig. 6 B, the G-V relationships of the wild-type channel (open symbols) and several mutants (solid symbols) are compared. The effects of each mutation were quantified by examining V1/2 values (Fig. 6 C). The mutations could be categorized into four subgroups. Three polar amino acids (Thr, Ser, and His) had no effect. Three others (Ala, Cys, and Glu) produced small negative G-V shifts of <40 mV. And three others (Pro, Asp, and Lys) produced large G-V shifts. The substitution of Gly-803 with Pro or Asp negatively shifted the Slo G-V relationship by 119.3 and 80.9 mV, respectively. In contrast, the substitution to Lys shifted the Slo G-V relation 30.0 mV in the positive direction. In all channels tested, the slopes of the G-V curves were not altered significantly by the mutation. These results indicate that the voltage-dependent activation of the BKCa channel is highly sensitive to the residue at position 803, and that single substitutions at this position can modulate the range of channel activation by as much as 147 mV without affecting the channel's voltage sensitivity.

FIGURE 6.

Functional effects of amino acid substitutions at Gly-803 in the putative RCK2. (A) Representative raw traces of the wild-type and four different mutant channels are shown. Ionic currents were induced by voltage steps ranging from −20 to 140 mV in 40-mV increments from the holding voltage of −100 mV. Each current trace represents an average of three successive records. Due to the marked differences in channel expression, the scale bar for each mutant channel was adjusted accordingly. (B) The G-V relationships of the wild-type (open symbols) and several mutant channels (solid symbols) are shown. The symbols for each mutant channel are indicated in the inset. Each channel was recorded with 2 μM [Ca2+]i. The curves were fitted with the Boltzmann function. (C) The V1/2 of the wild-type and nine different mutant channels were determined at 2 μM [Ca2+]i. The V1/2 of the wild-type is indicated as a dotted line. Each data point represents the mean ± SE. Values differing from the wild-type by the paired Student's t-test at p < 0.05 (*) or p < 0.01 (**) are indicated.

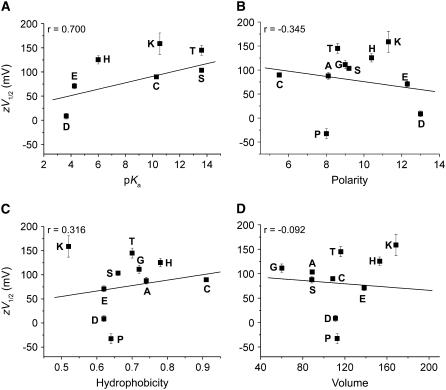

We wondered which aspect of the R-group is responsible for the perturbation of the gating equilibrium so sensitively. We tried to correlate the functional effects of the mutations with the biochemical and biophysical properties of the R-groups (47–49). The zV1/2 value of each mutant channel was plotted against the acid-ionization constant (pKa), polarity, hydrophobicity, and volume of the R-group (Fig. 7). pKa showed a statistically significant positive correlation with the G-V shifts of the mutant channels (correlation coefficient = 0.7 (n = 7)). The correlation coefficients (r) for the other comparisons however (−0.345 for polarity (n = 10), 0.316 for hydrophobicity (n = 10), and −0.092 for volume (n = 10)) did not indicate significant correlation.

FIGURE 7.

Correlation analysis of the zV1/2 values and biochemical and biophysical properties of the R-group at amino acid position 803. The zV1/2 values of each mutant channel were plotted against the pKa (A), polarity (B), hydrophobicity (C), and volume (D) of the R-group at position 803. Correlation coefficient (r) values for each property are shown in the inset.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the functional importance of amino acid residues located in the putative second RCK (RCK2) domain of the BKCa channel's α-subunit. We focused our attention on residues predicted by homology modeling to interact with RCK1 via the putative “flexible interface”. We did this to test for the presence of RCK2 and as well to perhaps gain experimental evidence in support of the arrangement of RCK1 and RCK2 in the homology model. Initially, we located four potential charge pairs across the interface and replaced the neutral residues on the putative RCK2 individually to either Lys or Asp, so that the mutated residues could interact electrostatically with countercharges on amino acids of RCK1. By examining the activation characteristics of the mutant channels, we initially found three mutations that altered the position of the G-V relation significantly. It was intriguing to observe that the mutations at different positions shifted the rSlo G-V relation in both the negative and positive directions, which suggests that they can stabilize either the open or the closed conformation. To examine whether mutations on the putative RCK2 domain alter the intrinsic equilibrium between open and closed, we performed further mechanistic studies on one such mutation, G803D.

This Gly residue (Gly-803 of rat Slo) is conserved, not only in the putative RCK2 of Slo homologs from Caenorhabditis elegans to human, but also in mammalian Slo paralogs such as Slick and Slo3 (Supplementary Fig. 1, highlighted in blue). Based on the known structure of the MthK RCK domain and our secondary-structure prediction, Gly-803 is predicted to be located within the first loop between βA and αA of the N-terminal Rossmann-fold. The significance of this position in the gating ring of octameric RCK domains may be considered from many points of view. Gly-803 is predicted to be close to the Ca2+-binding sites of homologous RCK domains. When aligned with the amino acid sequence of RCK1, Gly-803 is only two residues away from one of the Asp residues (Asp-428 of rat Slo) known to affect the calcium sensitivity at low concentration of calcium (27) (Supplementary Fig. 1, highlighted in yellow). In addition, the sequence alignment also predicts that the first loop of the MthK RCK domain, where Gly-803 is located in the putative RCK2, is physically close to the bound Ca2+ with the closest distance of only 6.2 Å from polypeptide chain. (23). Since the relative movement of the flexible interface has been shown to be the main conformational change induced by Ca2+ binding in MthK (23), it is conceivable that the residues facing the flexible interface would be sensitive to any mutation. Due to its positioning at this strategically critical region of the RCK heterodimer, the chemical nature of Gly-803 may determine the equilibrium between the open and the closed conformations and thus determines the position of the G-V relationship of BKCa channel.

Based on the positive correlation between zV1/2 and pKa of R-group at position 803 (Fig. 7 A), some electrostatic influence at this position on the shift in the gating equilibrium can be expected. In fact, we probed the charge pair corresponding to mutagenized Asp at position 803 of the putative RCK2 and Lys-556 of RCK1 to understand the nature of the interaction. Using the Ala substitution at Lys-556 in the background of the G803D mutation, a double mutant cycle analysis gave a coupling energy of 3.0 kJ mol−1 between Lys-556 of RCK1 and Asp-803 of RCK2 (data not shown). The magnitude of the coupling energy was rather weak, suggesting that the stabilization of the open conformation by the G803D mutation is more likely to be due to a weak through-space electrostatic attraction between the two residues rather than to a short-range salt bridge. It is also worth mentioning that no other countercharges other than Lys-556 were found in proximity to the amino acid position 803 in the structural model of the heterodimeric interface (Fig. 1 A). It is intriguing that Pro was such a stabilizing mutation for the open conformation and that it deviated the most from the correlation plots. It is conceivable that an amino-acid-like proline at this position adopts a local conformation that favors the open state. It remains to be seen whether the Gly-to-Pro mutation will also cause a shift in the intrinsic gating equilibrium.

In summary, we identified amino acid residues on the putative RCK2 domain of the BKCa channel's C-terminus that are important for channel activation. The most dramatic residue, Gly-803, modulated the channel's G-V relationship over a wide range of transmembrane voltages by altering the intrinsic gating equilibrium. These results are consistent with the structural model proposed for the putative RCK2 domain in which this residue is located on the flexible interface between RCK1 and RCK2. Thus, a conformational change in the gating ring, similar to that of bacterial Ca2+-activated K+ channels, may underlie the Ca2+-induced activation of the BKCa channel, and the putative RCK2 may be involved in the coupling between the Ca2+-bowl and transmembrane domains via RCK1.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view all of the supplemental files associated with this article, visit www.biophysj.org.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the members of the Laboratory of Molecular Neurobiology at Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology for their valuable comments and timely help throughout the work. Preliminary results of this work were presented in the 49th Annual Meeting of the Biophysical Society, 2005.

This research was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Korea (21C Frontier, 06K2201-00410) and the Korea Research Foundation (2005-015-C00398) to C-S.P., the U.S. National Institutes of Health (R01HL64831) to D.C., and the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (M10503010001-07N0301-00110) to D.H.K.

Editor: Richard W. Aldrich.

References

- 1.Robitaille, R., M. L. Garcia, G. J. Kaczorowski, and M. P. Charlton. 1993. Functional colocalization of calcium and calcium-gated potassium channels in control of transmitter release. Neuron. 11:645–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yazejian, B., D. A. DiGregorio, J. L. Vergara, R. E. Poage, S. D. Meriney, and A. D. Grinnell. 1997. Direct measurements of presynaptic calcium and calcium-activated potassium currents regulating neurotransmitter release at cultured Xenopus nerve-muscle synapses. J. Neurosci. 17:2990–3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fettiplace, R., and P. A. Fuchs. 1999. Mechanisms of hair cell tuning. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 61:809–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson, M. T., H. Cheng, M. Rubart, L. F. Santana, A. D. Bonev, H. J. Knot, and W. J. Lederer. 1995. Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science. 270:633–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner, R., G. J. Perez, A. D. Bonev, D. M. Eckman, J. C. Kosek, S. W. Wiler, A. J. Patterson, M. T. Nelson, and R. W. Aldrich. 2000. Vasoregulation by the beta1 subunit of the calcium-activated potassium channel. Nature. 407:870–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pluger, S., J. Faulhaber, M. Furstenau, M. Lohn, R. Waldschutz, M. Gollasch, H. Haller, F. C. Luft, H. Ehmke, and O. Pongs. 2000. Mice with disrupted BK channel beta1 subunit gene feature abnormal Ca2+ spark/STOC coupling and elevated blood pressure. Circ. Res. 87:E53–E60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petkov, G. V., A. D. Bonev, T. J. Heppner, R. Brenner, R. W. Aldrich, and M. T. Nelson. 2001. Beta1-subunit of the Ca2+-activated K+ channel regulates contractile activity of mouse urinary bladder smooth muscle. J. Physiol. 537:443–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahluwalia, J., A. Tinker, L. H. Clapp, M. R. Duchen, A. Y. Abramov, S. Pope, M. Nobles, and A. W. Segal. 2004. The large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel is essential for innate immunity. Nature. 427:853–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 9.Pallotta, B. S., K. L. Magleby, and J. N. Barrett. 1981. Single channel recordings of Ca2+-activated K+ currents in rat muscle cell culture. Nature. 293:471–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marty, A. 1981. Ca-dependent K channels with large unitary conductance in chromaffin cell membranes. Nature. 291:497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cui, J., D. H. Cox, and R. W. Aldrich. 1997. Intrinsic voltage dependence and Ca2+ regulation of mslo large conductance Ca-activated K+ channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 109:647–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang, X., C. R. Solaro, and C. J. Lingle. 2001. Allosteric regulation of BK channel gating by Ca2+ and Mg2+ through a nonselective, low affinity divalent cation site. J. Gen. Physiol. 118:607–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diaz, L., P. Meera, J. Amigo, E. Stefani, O. Alvarez, L. Toro, and R. Latorre. 1998. Role of the S4 segment in a voltage-dependent calcium-sensitive potassium (hSlo) channel. J. Biol. Chem. 273:32430–32436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui, J., and R. W. Aldrich. 2000. Allosteric linkage between voltage and Ca2+-dependent activation of BK-type mslo1 K+ channels. Biochemistry. 39:15612–15619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bezanilla, F. 2002. Voltage sensor movements. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:465–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horn, R. 2002. Coupled movements in voltage-gated ion channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:449–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gandhi, C. S., and E. Y. Isacoff. 2002. Molecular models of voltage sensing. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:455–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armstrong, C. M. 2003. Voltage-gated K channels. Sci. STKE. 2003:re10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma, Z., X. J. Lou, and F. T. Horrigan. 2006. Role of charged residues in the S1–S4 voltage sensor of BK channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 127:309–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei, A., C. Solaro, C. Lingle, and L. Salkoff. 1994. Calcium sensitivity of BK-type KCa channels determined by a separable domain. Neuron. 13:671–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schreiber, M., and L. Salkoff. 1997. A novel calcium-sensing domain in the BK channel. Biophys. J. 73:1355–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schreiber, M., A. Yuan, and L. Salkoff. 1999. Transplantable sites confer calcium sensitivity to BK channels. Nat. Neurosci. 2:416–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang, Y., A. Lee, J. Chen, M. Cadene, B. T. Chait, and R. MacKinnon. 2002. Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Nature. 417:515–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang, Y., A. Pico, M. Cadene, B. T. Chait, and R. MacKinnon. 2001. Structure of the RCK domain from the E. coli K+ channel and demonstration of its presence in the human BK channel. Neuron. 29:593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bao, L., C. Kaldany, E. C. Holmstrand, and D. H. Cox. 2004. Mapping the BKCa channel's “Ca2+ bowl”: side-chains essential for Ca2+ sensing. J. Gen. Physiol. 123:475–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bao, L., A. M. Rapin, E. C. Holmstrand, and D. H. Cox. 2002. Elimination of the BKCa channel's high-affinity Ca2+ sensitivity. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:173–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia, X. M., X. Zeng, and C. J. Lingle. 2002. Multiple regulatory sites in large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature. 418:880–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeng, X. H., X. M. Xia, and C. J. Lingle. 2005. Divalent cation sensitivity of BK channel activation supports the existence of three distinct binding sites. J. Gen. Physiol. 125:273–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bian, S., I. Favre, and E. Moczydlowski. 2001. Ca2+-binding activity of a COOH-terminal fragment of the Drosophila BK channel involved in Ca2+-dependent activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:4776–4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun, A. P., and L. Sy. 2001. Contribution of potential EF hand motifs to the calcium-dependent gating of a mouse brain large conductance, calcium-sensitive K+ channel. J. Physiol. 533:681–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lingle, C. J. 2007. Gating rings formed by RCK domains: keys to gate opening. J. Gen. Physiol. 129:101–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roosild, T. P., K. T. Le, and S. Choe. 2004. Cytoplasmic gatekeepers of K+-channel flux: a structural perspective. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29:39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pico, A. 2003. RCK domain model of calcium activation in BK channels. PhD thesis. The Rockefeller University, New York.

- 34.Kim, H. J., H. H. Lim, S. H. Rho, S. H. Eom, and C. S. Park. 2006. Hydrophobic interface between two regulators of K+ conductance domains critical for calcium-dependent activation of large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 281:38573–38581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Du, W., J. F. Bautista, H. Yang, A. Diez-Sampedro, S. A. You, L. Wang, P. Kotagal, H. O. Luders, J. Shi, J. Cui, G. B. Richerson, and Q. K. Wang. 2005. Calcium-sensitive potassium channelopathy in human epilepsy and paroxysmal movement disorder. Nat. Genet. 37:733–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qian, X., X. Niu, and K. L. Magleby. 2006. Intra- and intersubunit cooperativity in activation of BK channels by Ca2+. J. Gen. Physiol. 128:389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ha, T. S., S. Y. Jeong, S. W. Cho, H. Jeon, G. S. Roh, W. S. Choi, and C. S. Park. 2000. Functional characteristics of two BKCa channel variants differentially expressed in rat brain tissues. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:910–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim, H. H., and C. S. Park. 2005. Identification and functional characterization of ankyrin-repeat family protein ANKRA as a protein interacting with BKCa channel. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16:1013–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patton, C., S. Thompson, and D. Epel. 2004. Some precautions in using chelators to buffer metals in biological solutions. Cell Calcium. 35:427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bao, L., and D. H. Cox. 2005. Gating and ionic currents reveal how the BKCa channel's Ca2+ sensitivity is enhanced by its beta1 subunit. J. Gen. Physiol. 126:393–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cox, D. H., J. Cui, and R. W. Aldrich. 1997. Allosteric gating of a large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 110:257–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cox, D. H., and R. W. Aldrich. 2000. Role of the beta1 subunit in large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel gating energetics. Mechanisms of enhanced Ca2+ sensitivity. J. Gen. Physiol. 116:411–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horrigan, F. T., J. Cui, and R. W. Aldrich. 1999. Allosteric voltage gating of potassium channels I. Mslo ionic currents in the absence of Ca2+. J. Gen. Physiol. 114:277–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horrigan, F. T., and R. W. Aldrich. 1999. Allosteric voltage gating of potassium channels II. Mslo channel gating charge movement in the absence of Ca2+. J. Gen. Physiol. 114:305–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horrigan, F. T., and R. W. Aldrich. 2002. Coupling between voltage sensor activation, Ca2+ binding and channel opening in large conductance (BK) potassium channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:267–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, B., and R. Brenner. 2006. An S6 mutation in BK channels reveals beta1 subunit effects on intrinsic and voltage-dependent gating. J. Gen. Physiol. 128:731–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grantham, R. 1974. Amino acid difference formula to help explain protein evolution. Science. 185:862–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zamyatnin, A. A. 1972. Protein volume in solution. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 24:107–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rose, G. D., A. R. Geselowitz, G. J. Lesser, R. H. Lee, and M. H. Zehfus. 1985. Hydrophobicity of amino acid residues in globular proteins. Science. 229:834–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]