Abstract

Docking and fusion of vesicles to the plasma membrane is a fundamental process in living cells. An established model for the trafficking of vesicles is based on primary epithelial cells from the collecting duct of the nephron. Upon stimulation with the signaling peptide arginine-vasopressin (AVP), aquaporin-containing vesicles are directed to the plasma membrane. Since aquaporin selectively enhances the water permeability of plasma membranes, this process helps to balance the water content of the organism. A mechanism has been suggested involving local depolymerization of F-actin to facilitate the movement of vesicles to the membrane. Since F-actin is the major component of cytoskeletal restoring forces, AVP-stimulated cells can be expected to lose rigidity. Here, we used atomic force microscopy force mapping to test whether AVP alters cell stiffness. The Young's modulus of living epithelial cells at 37°C was continuously monitored, yielding a 51% decrease of Young's modulus after the addition of AVP. The data demonstrate that not the depolymerization of actin but a relaxation of actomyosin interaction facilitates vesicle translocation.

INTRODUCTION

The kidneys' function is to maintain the water and solute homeostasis of the organism. Of the water primarily filtered in the glomeruli, >99% is reabsorbed along the nephrons. Transcellular flow of water across tight epithelia is facilitated by aquaporins (AQPs), a family of transmembrane proteins selectively permeable for H2O (1,2). Fine-tuning of the net water reabsorption is performed by the epithelium of the collecting duct under control of the hypothalamic hormone arginine-vasopressin (AVP), secreted in case of thirst or low blood volume. As a response to this antidiuretic peptide AVP, these epithelial cells increase their water permeability, thereby preventing water loss of the organism.

The water permeability is directly proportional to the number of AQP-molecules in the membrane. Long-term regulation of AQP2 protein levels is controlled by a number of factors, including extracellular osmolarity (3), intracellular cyclic adenosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP), and AVP (4). The last is also the physiological stimulus for the quick adaptation of permeability increase. Its signaling cascade involves activation of the vasopressin-receptor 2 type (5) at the basolateral (blood) side of epithelial cells and a subsequent rise of the intracellular cAMP concentration. Defects in AQP2 are a cause of the autosomal dominant form of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.

The process of vesicle translocation to the plasma membrane is less elucidated than regulation of AQP2-protein levels, but the knowledge is increasing (6,7). Clearly, a rise of intracellular cAMP and activation of protein kinase A are obligatory (8), whereas specific A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAP) have an additional role (9). For the docking and fusion of AQP2-containing vesicles to the plasma membrane, elevation of intracellular cAMP might be sufficient (10). An inhibitory role within the translocation process has been demonstrated for the small GTPase Rho (11), probably via promoting actin polymerization. Consequently, the hypothesis has been raised that AQP2-containing vesicles are hindered or “caged” by actin fibers. Upon the rise of intracellular cAMP, this F-actin cage might be depolymerzsed (12). F-actin—as a major component of the cytoskeleton— has been proven to constitute the mechanical characteristics of a cell (13). Hence, it can be expected that cells lose rigidity upon stimulation with AVP if actin depolymerization is involved.

Mechanical characteristics of samples can well be determined under physiological conditions using atomic force microscopy (AFM) (14,15). This has been demonstrated by many AFM studies even on living cells. Cell stiffness is subject to change concomitantly to many cellular functions as important as cell division (16), cell migration (17), and cell volume regulation (18); however, detailed mechanisms are not always explored. Here, we used AFM to investigate whether mechanical aspects contribute to the response of primary renal cells to their physiological stimulus. We demonstrate cell softening after AVP stimulation to be mediated by actomyosin interaction concomitant to the translocation of AQP2-vesicles. This adds a new facet to the network of mechanisms regulating cellular water permeability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell isolation and cultivation

Inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) cells were prepared as described (19). Briefly, the inner medullas including papilla of deceased Wistar rats were removed, cut into small pieces, and digested in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) containing 0.2% hyaluronidase (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) and 0.2% collagenase type CLS-II (Sigma) at 37°C for 90 min. The cells were seeded on glass coverslips coated with collagen type IV (Becton-Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) at a density of ∼105 cells/cm2 and cultivated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing penicillin 100 IU/ml and streptomycin 100 μg/ml, 0.2% glutamine, 1% nonessential amino acids, and 1% ultroser. The osmolarity was adjusted to 600 mosmol/l by the addition of 100 mM NaCl and 100 mM urea. To maintain AQP2 expression, 10 μM dbcAMP was added. The cells were cultured for 5–7 days, and the dbcAMP was removed 14–18 h before the experiments.

Immunofluorescence

The localization of AQP2 was determined via immunofluorescence using a polyclonal AQP2 antibody, gratefully obtained from Dr. E. Klussmann, FMP, Berlin, Germany (19). IMCD cells either untreated or stimulated with AVP (0.5 μM final concentration; Bachem, Shirley, MA) were washed twice with PBS and fixed in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. The cells were washed with PBS (three times, 10 min), and the membranes were permeabilized in PBS containing 0.1% triton X100 for 5 min and washed three times for 10 min with PBS. The cells were incubated for 20 min in blocking solution (0.3% fish skin gelatin in PBS). The coverslips were then incubated at 37°C in a humidifying chamber for 90 min with the AQP2 antibody washed three times (PBS, 10 min) and incubated for 90 min with an Alexa488-labeled anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibody (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands). The cells were washed three times for 10 min in PBS and mounted with Crystalmount. Additional actin staining was performed, exposing the cells for 15 min to 5 μm TRITC (tetramethylrhodamine isothiocynate)-phalloidin (Sigma). Images were taken by a fluorescence microscope (Axiovert 200, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and a digital camera, CoolsnapHQ (Visitron, München, Germany).

AFM imaging

Contact mode AFM on epithelial cells was performed as described before (20). Briefly, AFM measurements were done in HEPES-buffered solution (pH 7.4) using a Multimode with Nanoscope III controller and heater stage under software version 5.12b48 (Digital Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA). Silicon nitride tips on V-shaped gold-coated cantilevers were used (0.01 N/m, MLCT, purchased through Veeco, Mannheim, Germany). To obtain the Young's modulus (YM) quantifying sample stiffness, arrays of force-distance curves were recorded by the “force volume” option implemented in the software, where the deflection of the cantilever (in nm) is taken as a function of the piezo elongation (z-distance in nm). To improve the time resolution, the number of force curves was reduced to 16 × 16 for the experiments on living cells, finally taking 8 min per force volume-image at 1 Hz scan frequency. Piezo travel speed was kept below 3 μm/s. In the reconstruction of maps for height and YM, raw data were processed by a routine for the software Igor Pro based on the Hertzian model of elasticity, as described earlier (15). Monitoring the development of elasticity with 20-s time resolution was performed using a tip with a 10-μm borosilicate sphere glued to the softest cantilever of an MLCT substrate (0.01 N/m; Novascan, Ames, IA). Scan area was set to zero and maximally 1.5 μm of z-travel were allowed with a deflection trigger of 44 nm not faster than 0.5 Hz. The data were processed with the software program PUNIAS, generously provided by Dr. Philippe Carl (Veeco).

RESULTS

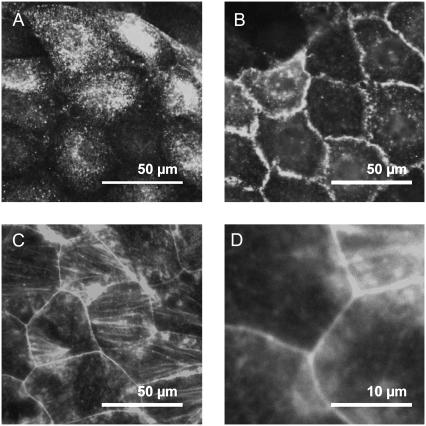

This study was designed to follow effects on cell mechanics upon a physiological stimulus in living cells. Hence, an intact signaling cascade of a well-differentiated epithelial cell culture is a central prerequisite. To assess the cell preparations (IMCD) to meet functional properties, they were exemplarily tested for hypotonic swelling by confocal microscopy; cells stimulated with AVP (500 nM) showed instant swelling upon hypotonic stress (data not shown). Furthermore, immunolabeling against AQP2 in permeabilized samples demonstrated a sensitivity of the cell preparations to the signaling peptide AVP (Fig. 1). Control cells clearly exhibited a cytosolic distribution of AQP2 (Fig. 1 A). The spotted appearance reflects the vesicular packaging of the protein. Contrastingly, in AVP-stimulated cells the major part of AQP2-immunoreactivity was localized at the plasma membrane (Fig. 1 B). Due to projection along the optical axis in the microscope, the main part of the plasma membrane appears at the cell junctions. Preparations that passed these tests indicating the signaling cascade to be intact were used for further experiments. To obtain an impression of the cytoskeletal organization, staining with rhodamine-labeled phalloidin was performed. Despite the rather heterogeneous situation with some poorly stained areas and others exhibiting intense stress fibers in proximity, the picture shown in Fig. 1 C is representative: the cytosol is almost devoid of fibers but is surrounded by a prominent F-actin belt at the cell junctions (zoom in Fig. 1 D).

FIGURE 1.

Fluorescence microscopy of IMCD cells. Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with triton. (A and B) Immunofluorescence labeling demonstrates subcellular distribution of AQP2-protein in (A) control and (B) AVP-stimulated samples. (C and D) Staining with rhodamin-labeled phalloidin shows the distribution of F-actin. (C) The concentration of f-actin to the junctions and (D) a rather low density of fibers in the cytosolic areas can be seen. Micrographs are representative for n > 10.

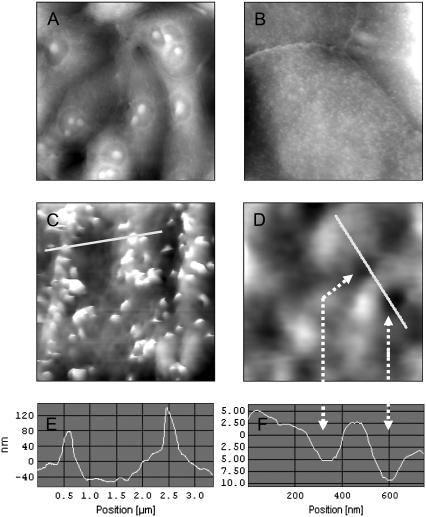

To further characterize the cellular architecture at the level of the apical membrane, we performed AFM contact imaging on cells that were fixed with the protein cross-linking agent glutardialdehyde (0.5% in growth medium for 30 min at 37°C) (Fig. 2). A 100 μm view of a typical IMCD culture is given in Fig. 2 A. A zoom to 25 μm (Fig. 2 B) exhibits two predominant structural features of IMCD cells: the numerous protrusions representing microvilli and the clearly elevated seam of well-developed cellular junctions. An even closer look at 5 μm scan range (Fig. 2 C) reveals the dimension of the microvilli, which resemble 100–200 nm in height and 200–400 nm in diameter (Fig. 2 E). Zooming into a flat area without microvilli (1 μm, Fig. 2 D) reveals pits in the surface of 150–250 nm in diameter and 5–10 nm in depth (Fig. 2 F). They might represent inserted vesicles that have been fixed in the course of membrane fusion. One would expect a stimulated sample to exhibit more of these depressions than a control cell. However, a representative vesicle count is difficult, because a large fraction of the surface is inaccessible for the AFM tip (due to steric hindrance by the microvilli). Thus, no further argument could be derived from the number of vesicles to assign these formations as freshly fused AQP2-containing vesicles.

FIGURE 2.

AFM of fixed IMCD cells. Cells grown on coverslips were fixed with 0.5% glutardialdehyde and subjected to AFM contact mode imaging. The height is coded in grayscale: the bottom is black and the top of the image is white. The scales are (A) 100 μm in width and 8 μm in height, (B) 25 μm/3 μm, (C) 5/500 nm, and (D) 1 μm/100 nm, respectively. E and F are sections along the white lines in C and D. The arrows mark the sites of pits (D and F).

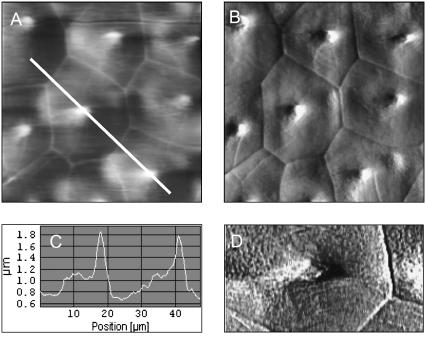

To address the hypothesis of vesicle translocation being facilitated through uncaging via actin depolymerization, the cellular stiffness had to be determined on nonfixed cells. Living cells were recorded in AFM contact mode first to get an overview (Fig. 3). A typical height image of a well-differentiated 50-μm region is shown in Fig. 3 A; the corresponding “deflection” image (uncorrected movements of the cantilever) lets us even better recognize the “cubic” organization of the cell layer (Fig. 3 B). At their center, the cells exhibit a large cilium up to 2 μm in height as seen from a section along the white line in Fig. 3 A (Fig. 3 C). This probably is the central cilium. Although not directly visible, image processing of Fig. 3 B applying a “Kirsch West” filter is also able to resolve the grainy pattern caused by microvilli on nonfixed cells (Fig. 3 D). The stiffness measurements were focused onto regions carrying central cilia, because they are indicative for principal cells, the subgroup of collecting duct epithelial cells positive for AQP2.

FIGURE 3.

AFM contact mode of living IMCD cells. Cells grown on glass coverslips were imaged in HEPES buffer at 37°C. (A) Height image and (B) deflection image showing a typical 50-μm region in contact mode operation. (C) Height profile along the white line in A. (D) A data zoom (20 × 10 μm2) of B is processed by image filtering to resolve microvilli (the small grainy pattern).

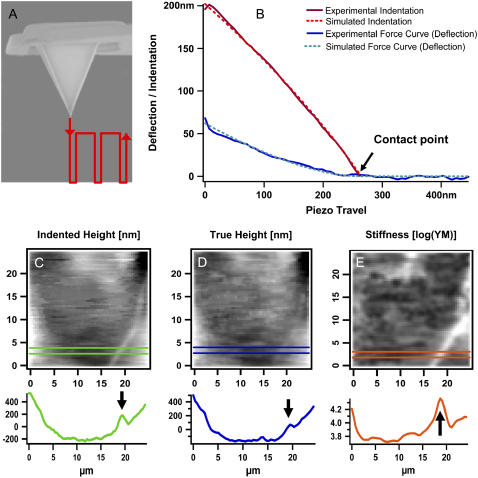

To test whether cell rigidity is affected in the course of AVP signaling, a so-called “force-volume” mapping was performed (Fig. 4). This procedure gently pokes into the sample point by point (Fig. 4 A) to record force versus distance cycles in an array of 64 × 64 curves, one example being given in Fig. 4 B. The bending of the cantilever (deflection) is plotted as a function of piezo travel (retraction). Starting from the right end, the line is horizontal as long as the tip is distant from the sample. Upon contact with the sample, the cantilever starts to bend more and more the further it is pressed down on the material. The deflection is depicted as a blue solid line, the curve fit as a dotted line. On the basis of the computed YM, the indentation of the sample can be calculated (red lines).

FIGURE 4.

AFM force mapping method. (A) Scheme of the tip and its travel path (red). (B) Example of a force-distance curve. Original tracing of one approach curve (blue) and its curve fit (green) are shown as well as the calculated indentation of the sample (red) and its curve fit (orange). A (25 μm2) scan area of cells grown on glass coverslips were covered by an array of 64 × 64 curves in HEPES buffer at room temperature. Three types of information can be extracted from the data field: (C) the height under force load, (D) the “true” height of the sample without any force load, and (E) a map of sample stiffness. Corresponding profiles are given below the maps. A cell junction is marked by an arrow. Note that the grayscales in C and D denote nanometers (nm) and E gives Pascal (Pa).

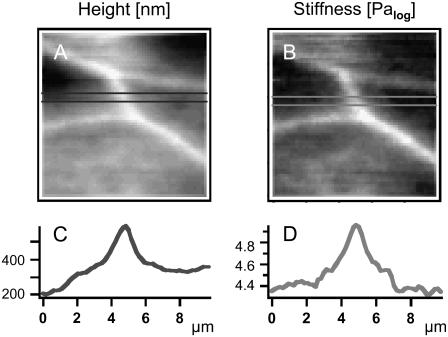

Here, a deflection of 50 nm equals 200 nm of sample indentation, given a YM of 40 kPa. From the force volume data array, mainly three types of maps can be extracted: i), the sample height at a given force load (indented height, Fig. 4 C); ii), the “true” height (height without force load, reconstructed from the contact points, Fig. 4 D); and iii), the YM depicting sample stiffness (from fitting of the curves according to the Hertz model of elasticity, Fig. 4 E). The example taken here is a 25-μm region of a living cell including cell junction (bright line) crossing the lower right corner. An arrow in the corresponding sections below the images marks the junction, whose elevation clearly appears higher under a given force load (Fig. 4 C) as compared to the case without force (Fig. 4 D). This is due to the fact that the stiff junctions are indented to a lesser extent by the tip force than the softer cytosolic areas are (Fig. 4 E). For a better visualization of the heterogeneous situation, a smaller region was recorded (Fig. 5). The “true” height (Fig. 5 A) is compared to sample stiffness (Fig. 5 B). From the sections below the maps, elevation of junctions is 150 nm (Fig. 5 C), which corresponds to a considerable local difference in YM: the junctions are three times as rigid as cytosolic areas (Fig. 5 D).

FIGURE 5.

AFM force mapping of living IMCD cells. Cells grown on glass coverslips were subjected to force volume imaging in HEPES buffer at 37°C. (A) Reconstructed height map and (B) stiffness map of a 10 μm junctional area of four neighboring cells. C and D show profiles through the corresponding maps above.

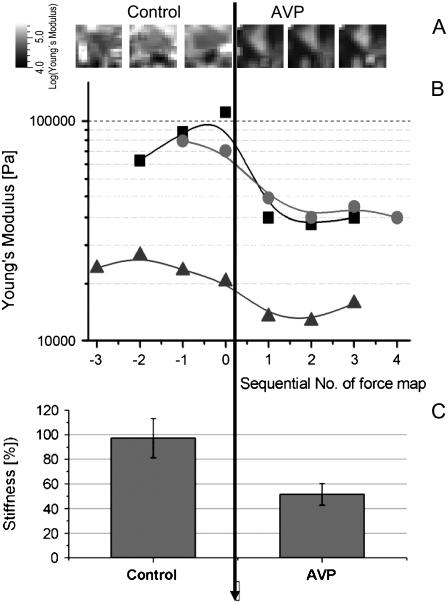

Due to the large spatial differences in YM, we monitored an area of (50 μm)2 covering several cell nuclei and cytosolic and junctional regions for the paired experiments with AVP-stimulation (Fig. 6). To shorten acquisition time from ∼1 h to 6 min, the map was reduced to a field of 16 × 16 (= 256) curves. Hence, the lateral resolution (3.1 μm) contains only minimal morphological information but gives a representative screen over different subcellular regions. Fig. 6 A shows a time series of stiffness maps corresponding to the filled squares data points in Fig. 6 B. Upon addition of AVP, the YM decreased in <15 min, seen as darkening of the stiffness maps. The mean of 256 values from each map is plotted as one data point in Fig. 6 B as a function of time, and three experiments are shown. Recording force maps as a function of time at 37°C yielded a fairly constant value for a given region in the course of more than an hour. Of note, this demonstrates a low degree of influence from the measuring process, i.e., through the gentle mechanical stimulation by the AFM tip. After addition of AVP the values clearly decreased. Taking all data points together before and after stimulation, the reduction resembled a factor of 2.05 (Fig. 6 C; ranging from 1.7 to 2.8, depending on the individual preparation; n = 3, t-value = 4 × 10−7). This shows a highly significant reduction of the cellular stiffness in response to AVP.

FIGURE 6.

Monitoring of sample stiffness in living cells. Force mapping experiments were sequentially performed at 37°C in PBS. (A) The development of the YM over time (addition of AVP at t = 0) is plotted for an experiment covering a (50 μm2) region (16 × 16 curves). (B) Each point represents an average value extracted from 256 curves, time interval is ∼8 min between data points. (C) Data from B before and after addition of AVP are gathered as relative values (control = 100%, linear scale).

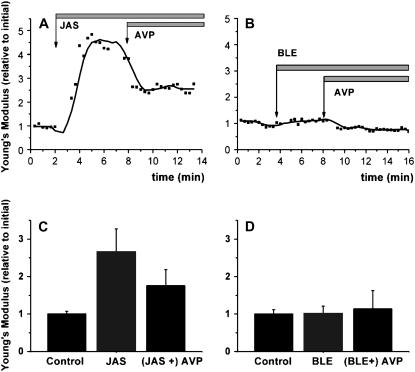

To discriminate between different mechanisms of cellular softening, we made some experiments using pharmacological actors on the actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 7). A continuous z-ramping was run with no morphological information for the sake of best time resolution; to maintain the coverage of a representative area and to reduce noise, a tip modified with a 10-μm glass sphere was used. If actin depolymerization is the reason for AVP-induced softening, then it should be blocked by jasplakinolide, an F-actin stabilizing agent. Jasplakinolide (10 μM) itself significantly increased cell stiffness, but surprisingly did not block the effect of AVP (Fig. 7 A). The average increase of four independent experiments gives an increase to 267% of initial YM for the increase and a reduction back to 171% (Fig. 7 C). Another main possibility for softening a cell is to relax actomyosin interaction. The nonmuscle myosinII inhibitor blebbistatin (10 μM) had no intrinsic effect, but it completely blocked the AVP response (Fig. 7 B). Within four experiments the values did not significantly alter from the starting level (100%) (Fig. 7 D).

FIGURE 7.

Monitoring stiffness with high time resolution. Z-ramping was performed on living cells at 37°C without lateral scanning using a tip with a 10-μm sphere. Cells were incubated with (A and C) jasplakinolide (10 μM) or (B and D) blebbistatin (10 μM) before addition of AVP (indicated by arrows). Each data point in A or B represents the average of 10 force curves. (C and D) represent the mean values (relative to initial) of four independent experiments as in A or B, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this study, AFM force mapping was applied to test whether AVP signaling influences cell mechanics via the actin cytoskeleton. Primary cultures of collecting duct epithelial cells were characterized in terms of biologic function, three-dimensional morphology, and cell mechanics. A loss of rigidity could be detected in response to this stimulus under physiological conditions. In contrast to the previously hypothesized actin depolymerization, this effect could be attributed to a relaxation of actomyosin interaction.

The IMCD cells taken here as a cellular model for vesicle translocation have been well characterized by light microscopic, biochemical, and electrophysiological methods. Here, we report on their morphology and mechanical characteristics by means of AFM. The appearance of fixed cells is quite comparable to what can be expected from electron microscopic and light microscopic knowledge (21). Moreover, the morphological data are very comparable to Madine-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells. Also, the elevation of junctions has been observed before in this cell line made from the collecting duct (22).

A novel structural feature is the occurrence of pits between 100 and 200 nm in size with a frequency of 0.5 per μm2. These structures cannot be identified unequivocally by AFM but might represent sites of vesicle fusion. A size of 120 nm for AQP2-carrying vesicles has been reported from a study using transmission electron microscopy with immunogold labeling (10). But apart from the pit size matching the expected regime of 200 nm, no further data could be gathered so far to prove this interpretation.

Since AFM is not a standard technique in cell biology yet, we would like to stress its advantages in the context here. Principally, the determination of a soft sample's elasticity requires careful calibration of the instrumentation. But performing experiments on identical cellular regions using the same tip liberates us from calibration of the cantilever force constant and other obstacles in the path to absolute values for the YM. In this respect, it is uniquely suitable for the observation of mechanical changes as a function of time. Moreover, data can be obtained even at subcellular resolution. From the cell biology perspective, this is advantageous, especially in the case of heterogenic cell culture samples as often obtained from primary cell culture. It has been clearly demonstrated that cell stiffness almost exclusively is built up by actin fibers, whereas microtubuli do not contribute to a significant extent (13). This equivalence is fundamental for the interpretation of the data.

Because we intended to address mainly the cell cortex, the experimental parameters were adjusted to indent the cells not more than a few hundred nanometers, which is only a small fraction of the total cell height (3–6 μm). The positive effects are, on the one hand, that the mechanical stress on the cells by the force load of the tip is kept at a minimum; the stable YM values over time (within ±0.15 orders of magnitude) prove that the measuring process does not lead to substantial cell activation. On the other hand, under these minimal invasion conditions, stiffness measurements can be considered to describe mainly the apical cortex region of the cells, because the contributions from the deeper regions vanish with the distance from the tip.

Within this study, AFM images of central cilia could be obtained. The physiological function of central cilia has not yet been identified equivocally, but they might serve as a sensor for the flow of urine (23,24). However, their appearance identifies principal cells, which are the ones positive for the AQP2-signaling mechanism. The experiments have been focused on these regions to maximize the relevance of the data.

Of note, the cytoskeletal organization of epithelia is obviously different from vascular endothelial cells: the so-called “stress fibers” which characteristically dominate the stiffness maps of living endothelial cells or fibroblasts (25,13) are not visible here. Instead of the rigid ropes of F-actin bundles, the IMCD cells develop an actin belt at their tight junctions, which is well reflected by the mechanical picture where the border regions are three times stiffer than the cytosol. Since in IMCD cells stress fibers occurred regularly, as seen by phalloidin staining (this study, data not shown, and Klussmann et al. (12)), the question arises of why their cytosolic area in a stiffness map appears more homogeneous than in endothelial cells. We would favor the view that because IMCD cells are higher than endothelial cells (5 versus 1 μm), the stress fibers are located more basolaterally and hence more distantly from the exploring AFM tip.

Our observation of cell softening as induced by AVP is in line with the concept of Tamma et al., who reported on cytoskeleton cross-linking proteins ezrin/radixin/moesin being redistributed within the cell cortex region after forskolin stimulation (26). Both AVP and forskolin elevate intracellular concentrations of the second messenger molecule cAMP, which is known to relax the actomyosin interaction. A recent report demonstrates the role of motor proteins for AQP-trafficking: in cholangiocytes, the colocalization of AQP1 to dynein and kinesin indicates a function in the translocation of AQP1-vesicles (27). The notion of actomyosin interaction being a relevant factor obtains support from a very recent molecular biology study: an equivalent transport system comprising myosinVb and Rab11 has been found necessary for vesicle shuttling in the AQP2/IMCD system (28). Of note, this also disproves depolymerization of cortical actin to be the responsible mechanism, because then the myosin would be deprived of the path to rail the cargo along.

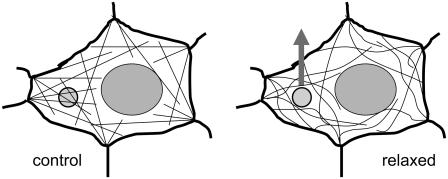

Taken together, AFM force mapping uniquely allows for monitoring cytoskeletal mechanics on living cells, demonstrating that vesicle translocation is accompanied by a reduction of cell stiffness, which is caused by actomyosin relaxation. The facilitating effect might be due to a loss of steric hindrance and thus a lowered flow resistance for the vesicles having to pass by the fibers (as schematically summarized in Fig. 8). The results tempt us to speculate that this rather general mechanism might facilitate not only the translocation to but also the reuptake of vesicles from the plasma membrane—an issue to be addressed in future studies.

FIGURE 8.

Sketch of the mechanical model. (Left) A vesicle (small circle) is spun into the web of actin filaments under a certain tension. (Right) Relaxation of actomyosin interaction facilitates the movement of vesicles due to reduced steric hindrance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rainer Matzke and Tilman Schaeffer for assistance with force curve analysis.

The study was financially supported by the European Union Project “Tips for Cells” to H.O., DFGSchl277/11-3 to E.S., and the “Innovative Medizinische Forschung” Münster project IMF RI 220506 to C.R.

Editor: Thomas Schmidt.

References

- 1.Nielsen, S., J. Frokiaer, D. Marples, T. H. Kwon, P. Agre, and M. A. Knepper. 2002. Aquaporins in the kidney: from molecules to medicine. Physiol. Rev. 82:205–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agre, P., L. S. King, M. Yasui, W. B. Guggino, O. P. Ottersen, Y. Fujiyoshi, A. Engel, and S. Nielsen. 2002. Aquaporin water channels—from atomic structure to clinical medicine. J. Physiol. 542:3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Storm, R., E. Klussmann, A. Geelhaar, W. Rosenthal, and K. Maric. 2003. Osmolality and solute composition are strong regulators of AQP2 expression in renal principal cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 284:F189–F198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasler, U., D. Mordasini, M. Bens, M. Bianchi, F. Cluzeaud, M. Rousselot, A. Vandewalle, E. Feraille, and P. Y. Martin. 2002. Long term regulation of aquaporin-2 expression in vasopressin-responsive renal collecting duct principal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277:10379–10386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birnbaumer, M., A. Seibold, S. Gilbert, M. Ishido, C. Barberis, A. Antaramian, P. Brabet, and W. Rosenthal. 1992. Molecular cloning of the receptor for human antidiuretic hormone. Nature. 357:333–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noda, Y., and S. Sasaki. 2006. Regulation of aquaporin-2 trafficking and its binding protein complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1758:1117–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valenti, G., G. Procino, G. Tamma, M. Carmosino, and M. Svelto. 2005. Minireview: aquaporin 2 trafficking. Endocrinology. 146:5063–5070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katsura, T., C. E. Gustafson, D. A. Ausiello, and D. Brown. 1997. Protein kinase A phosphorylation is involved in regulated exocytosis of aquaporin-2 in transfected LLC-PK1 cells. Am. J. Physiol. 272:F817–F822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henn, V., B. Edemir, E. Stefan, B. Wiesner, D. Lorenz, F. Theilig, R. Schmitt, L. Vossebein, G. Tamma, M. Beyermann, E. Krause, F. W. Herberg, G. Valenti, S. Bachmann, W. Rosenthal, and E. Klussmann. 2004. Identification of a novel A-kinase anchoring protein 18 isoform and evidence for its role in the vasopressin-induced aquaporin-2 shuttle in renal principal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279:26654–26665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lorenz, D., A. Krylov, D. Hahm, V. Hagen, W. Rosenthal, P. Pohl, and K. Maric. 2003. Cyclic AMP is sufficient for triggering the exocytic recruitment of aquaporin-2 in renal epithelial cells. EMBO Rep. 4:88–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamma, G., E. Klussmann, K. Maric, K. Aktories, M. Svelto, W. Rosenthal, and G. Valenti. 2001. Rho inhibits cAMP-induced translocation of aquaporin-2 into the apical membrane of renal cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 281:F1092–F1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klussmann, E., G. Tamma, D. Lorenz, B. Wiesner, K. Maric, F. Hofmann, K. Aktories, G. Valenti, and W. Rosenthal. 2001. An inhibitory role of Rho in the vasopressin-mediated translocation of aquaporin-2 into cell membranes of renal principal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20451–20457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rotsch, C., and M. Radmacher. 2000. Drug-induced changes of cytoskeletal structure and mechanics in fibroblasts: an atomic force microscopy study. Biophys. J. 78:520–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fritz, M., M. Radmacher, and H. E. Gaub. 1993. In vitro activation of human platelets triggered and probed by atomic force microscopy. Exp. Cell Res. 205:187–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radmacher, M. 1997. Measuring the elastic properties of biological samples with the AFM. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag. 16:47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matzke, R., K. Jacobson, and M. Radmacher. 2001. Direct, high-resolution measurement of furrow stiffening during division of adherent cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:607–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laurent, V. M., S. Kasas, A. Yersin, T. E. Schaffer, S. Catsicas, G. Dietler, A. B. Verkhovsky, and J. J. Meister. 2005. Gradient of rigidity in the lamellipodia of migrating cells revealed by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 89:667–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider, S. W., Y. Yano, B. E. Sumpio, B. P. Jena, J. P. Geibel, M. Gekle, and H. Oberleithner. 1997. Rapid aldosterone-induced cell volume increase of endothelial cells measured by the atomic force microscope. Cell Biol. Int. 21:759–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maric, K., A. Oksche, and W. Rosenthal. 1998. Aquaporin-2 expression in primary cultured rat inner medullary collecting duct cells. Am. J. Physiol. 275:F796–F801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oberleithner, H., C. Riethmuller, T. Ludwig, V. Shahin, C. Stock, A. Schwab, M. Hausberg, K. Kusche, and H. Schillers. 2006. Differential action of steroid hormones on human endothelium. J. Cell Sci. 119:1926–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fejes-Toth, G., and A. Naray-Fejes-Toth. 1993. Differentiation of intercalated cells in culture. Pediatr. Nephrol. 7:780–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson, R. M., and H. Oberleithner. 2000. Pushing, pulling, dragging, and vibrating renal epithelia by using atomic force microscopy. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 278:F689–F701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Praetorius, H. A., and K. R. Spring. 2005. A physiological view of the primary cilium. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 67:515–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singla, V., and J. F. Reiter. 2006. The primary cilium as the cell's antenna: signaling at a sensory organelle. Science. 313:629–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riethmuller, C., T. E. Schaffer, F. Kienberger, W. Stracke, and H. Oberleithner. 2007. Vacuolar structures can be identified by AFM elasticity mapping. Ultramicroscopy. 107:895–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamma, G., E. Klussmann, J. Oehlke, E. Krause, W. Rosenthal, M. Svelto, and G. Valenti. 2005. Actin remodeling requires ERM function to facilitate AQP2 apical targeting. J. Cell Sci. 118:3623–3630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tietz, P. S., M. A. McNiven, P. L. Splinter, B. Q. Huang, and N. F. Larusso. 2006. Cytoskeletal and motor proteins facilitate trafficking of AQP1-containing vesicles in cholangiocytes. Biol. Cell. 98:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nedvetsky, P. I., E. Stefan, S. Frische, K. Santamaria, B. Wiesner, G. Valenti, J. A. Hammer III, S. Nielsen, J. R. Goldenring, W. Rosenthal, and E. Klussmann. 2007. A Role of myosin Vb and Rab11-FIP2 in the aquaporin-2 shuttle. Traffic. 8:110–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]