Abstract

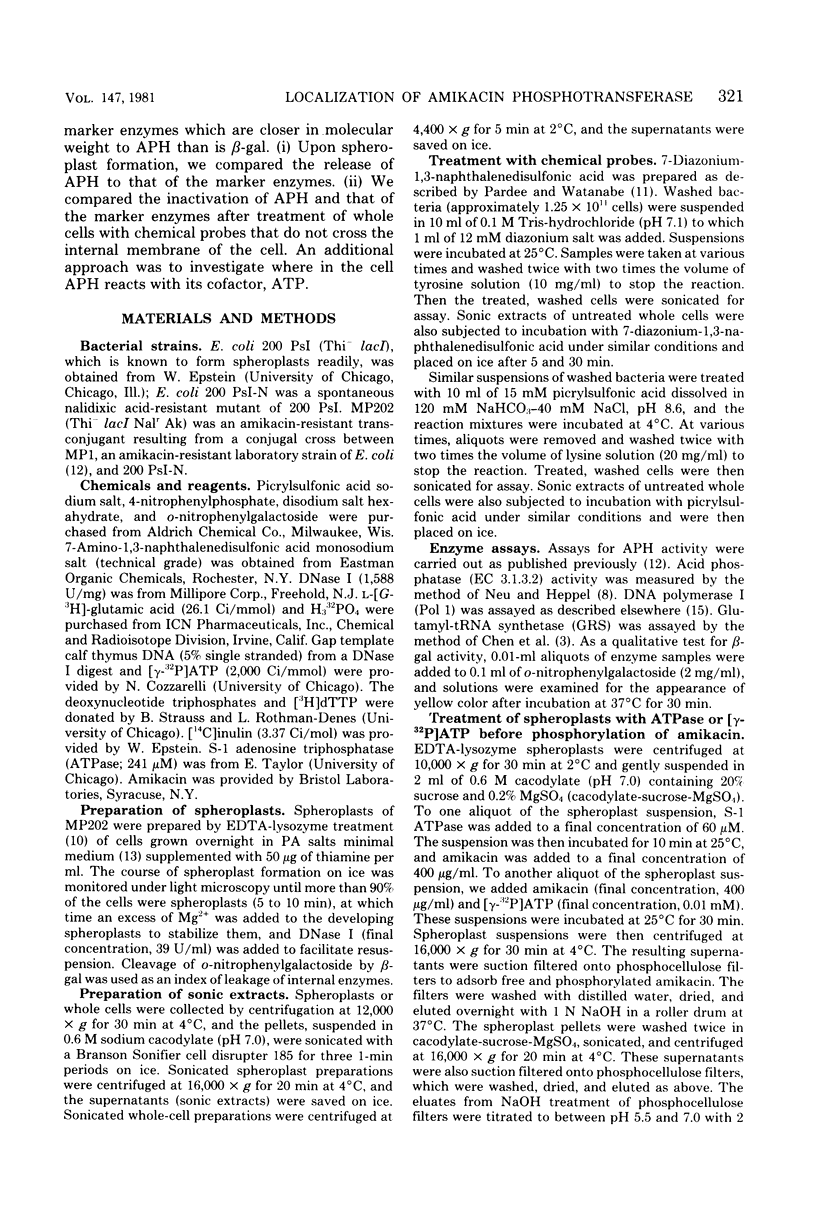

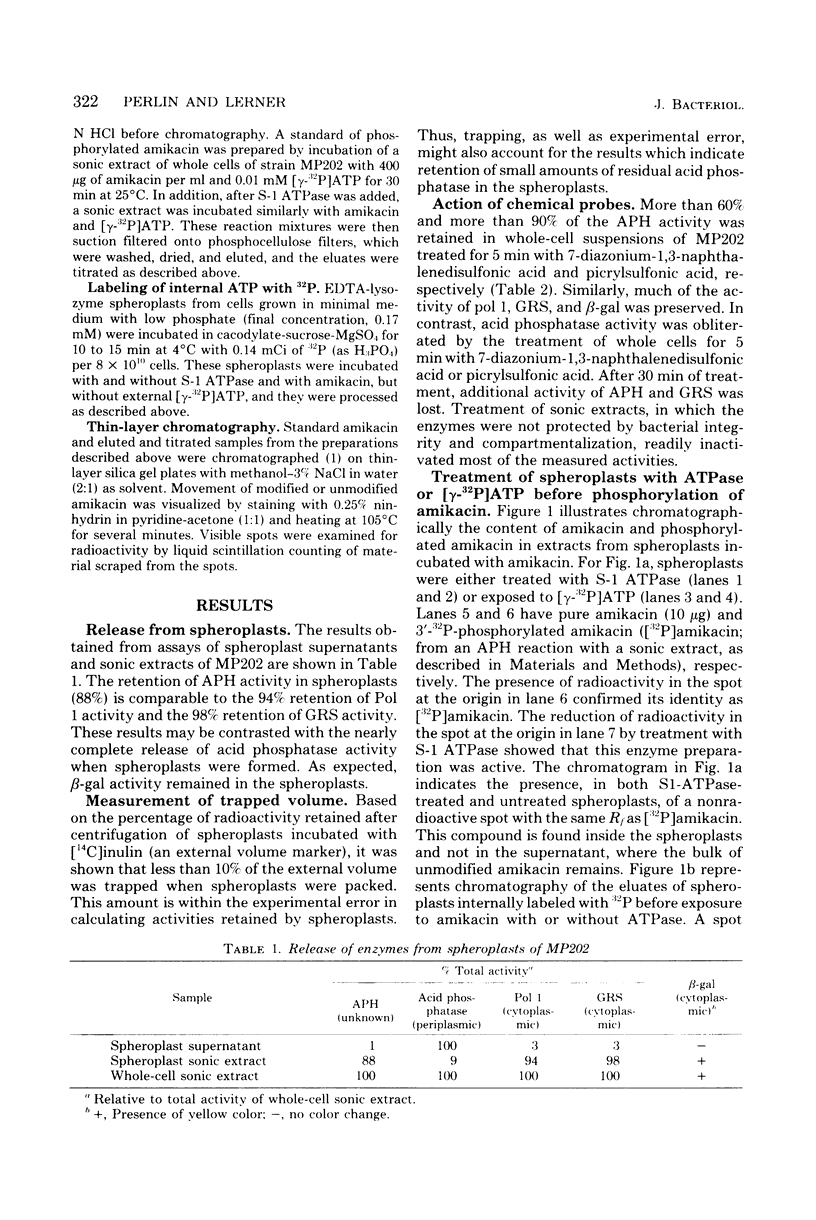

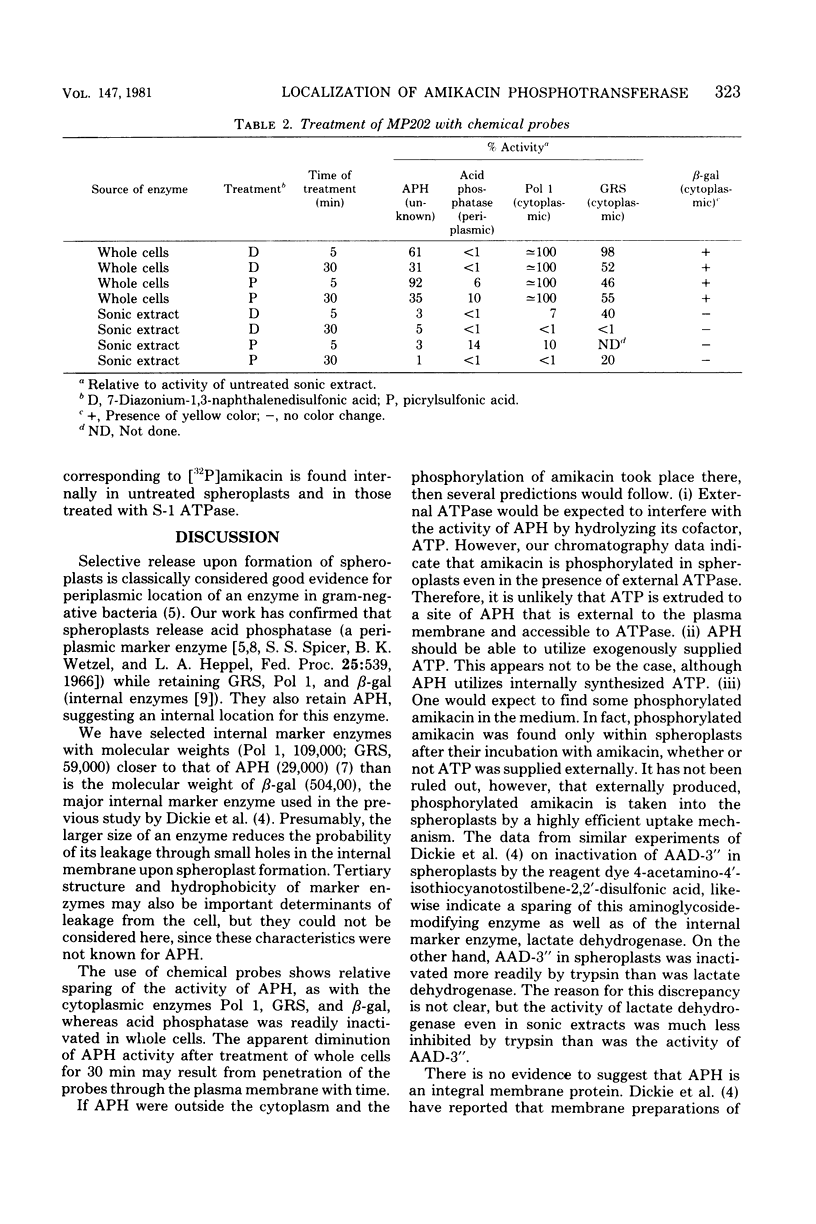

A plasmid-encoded enzyme reported by us to phosphorylate amikacin in a laboratory strain of Escherichia coli has been localized in the bacterial cell. More than 88% of this amikacin phosphotransferase (APH) activity was retained in spheroplasts formed by ethylenediaminetetraacetate-lysozyme treatment of an APH-containing E. coli transconguant known to form spheroplasts readily. By comparison, the spheroplasts retained 94% of deoxyribonucleic acid polymerase I and 98% of glutamyl-transfer ribonucleic acid synthetase, two internal markers, whereas less than 10% of the activity of a periplasmic marker, acid phosphatase, was present in spheroplasts. Treatment of whole cells of the transconjugant with chemical probes incapable of crossing the plasma membrane obliterated acid phosphatase activity, whereas the internal markers deoxyribonucleic acid polymerase I, glutamyl-transfer ribonucleic acid synthetase, and β-galactosidase were virtually unaffected after treatment for 5 min; more than 60% of the APH activity remained. As a control, similar chemical treatment of sonic extracts, in which enzymes were not protected by bacterial compartmentalization, produced more extensive reduction in the activities of all test enzymes, including APH. Spheroplasts preincubated with adenosine triphosphatase were shown by thin-layer chromatography to phosphorylate amikacin. Spheroplasts of cells grown in the presence of H332PO4 were shown to utilize internally generated adenosine 5′-triphosphate in the phosphorylation of amikacin. The absence of 32P-phosphorylated amikacin after incubation of [γ-32P]adenosine 5′-triphosphate with spheroplasts confirmed that exogenous adenosine 5′-triphosphate was not used in the reaction. These results suggest an internal location for APH. This conclusion has implications for the role of such enzymes in aminoglycoside resistance of gram-negative bacteria.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aszalos A., Frost D. Thin-layer chromatography of antibiotics. Methods Enzymol. 1975;43:172–213. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(75)43084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste R., Davies J. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 1973;42:471–506. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.42.070173.002351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. J., Locker J., Weiss S. B. The physical mapping of bacteriophage T5 transfer tRNAs. J Biol Chem. 1976 Jan 25;251(2):536–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickie P., Bryan L. E., Pickard M. A. Effect of enzymatic adenylylation on dihydrostreptomycin accumulation in Escherichia coli carrying an R-factor: model explaining aminoglycoside resistance by inactivating mechanisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978 Oct;14(4):569–580. doi: 10.1128/aac.14.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppel L. A. Selective release of enzymes from bacteria. Science. 1967 Jun 16;156(3781):1451–1455. doi: 10.1126/science.156.3781.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundbäck A. K., Nordström K. Mutations in Escherichia coli K-12 decreasing the rate of streptomycin uptake: synergism with R-factor-mediated capacity to inactivate streptomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1974 May;5(5):500–507. doi: 10.1128/aac.5.5.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuhashi Y., Sawa T., Takeuchi T., Umezawa H., Nagatsu I. Localization of aminoglycoside 3'-phosphotransferase II on a cellular surface of R factor resistant Escherichia coli. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1976 Oct;29(10):1129–1130. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.29.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu H. C., Heppel L. A. On the surface localization of enzymes in E. coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1964 Oct 14;17(3):215–219. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(64)90386-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu H. C., Heppel L. A. The release of enzymes from Escherichia coli by osmotic shock and during the formation of spheroplasts. J Biol Chem. 1965 Sep;240(9):3685–3692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn M. J., Gander J. E., Parisi E., Carson J. Mechanism of assembly of the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium. Isolation and characterization of cytoplasmic and outer membrane. J Biol Chem. 1972 Jun 25;247(12):3962–3972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardee A. B., Watanabe K. Location of sulfate-binding protein in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1968 Oct;96(4):1049–1054. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.4.1049-1054.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlin M. H., Lerner S. A. Amikacin resistance associated with a plasmid-borne aminoglycoside phosphotransferase in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979 Nov;16(5):598–604. doi: 10.1128/aac.16.5.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBINSON D. S. OXIDATION OF SELECTED ALKANES AND RELATED COMPOUNDS BY A PSEUDOMONAS STRAIN. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1964;30:303–316. doi: 10.1007/BF02046736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg H. The measurement of membrane potential and deltapH in cells, organelles, and vesicles. Methods Enzymol. 1979;55:547–569. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)55066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlow P. DNA polymerase I from Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1974;29:3–12. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(74)29003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]