Abstract

We identified the phosphatidylinositol transfer protein (PITP) as being responsible for a powerful latent, nucleotide-independent, Golgi-vesiculating activity that is present in the cytosol but is only manifested as an uncontrolled activity in a cytosolic protein subfraction, in which it is separated from regulatory components that appear to normally limit its action to the scission of COPI-coated buds from trans-Golgi network membranes. A specific anti-PITP antibody that recognizes the two mammalian PITP isoforms fully inhibited the capacity of the cytosol to support normal vesicle generation as well as the uncontrolled vesiculating activity manifested by the cytosolic protein subfraction. The phosphatidylinositol- (PI) loaded form of the yeast PITP, Sec14p, but not the phosphatidylcholine- (PC) loaded form of the protein, was capable of substituting for the cytosolic subfraction in promoting the scission of coated buds from the trans-Golgi network. At higher concentration, however, Sec14p, when loaded with PI, but not with PC or phosphatidylglycerol, caused by itself an indiscriminate vesiculation of uncoated Golgi membranes that could be suppressed by PC-Sec14p, which also suppresses the uncontrolled vesiculation caused by the cytosolic subfraction. We propose that, by delivering PI to specific sites in the Golgi membrane near the necks of coated buds, PITP induces local changes in the organization of the lipid bilayer, possibly involving PI metabolites, that triggers the fusion of the ectoplasmic faces of the Golgi membrane necessary for the scission of COPI-coated vesicles.

The production of the different types of carrier vesicles that mediate transport between compartments of the cellular endomembrane system proceeds along two successive stages: (i) recruitment from the cytosol of protein coat components that assemble on the donor membrane and lead to the formation of coated buds, and (ii) severing of the buds to create free coated vesicles containing cargo molecules. Coat assembly for the COPII-coated vesicles that emerge from the endoplasmic reticulum, for the COPI-coated vesicles that form throughout the Golgi and in the trans-Golgi network (TGN), and for the clathrin-coated vesicles that transport lysosomal components from the TGN to incipient lysosomes is in all cases triggered by the activation of a small molecular weight GTP-binding protein, Sar1p for COPII-coated vesicles (1), and Arf1 for the COPI- (2) and clathrin-coated vesicles (3–6). Assembly of a coat is thought to be an important factor in leading to the deformation of the donor membrane to create a bud (7) and, at least for the case of clathrin- and COPII-coated vesicles, to play a role in concentrating cargo molecules within the emerging vesicles (for review, see ref. 8).

After bud formation, the release of a carrier vesicle requires a membrane fusion event in the donor membrane that must begin in the neck of the bud, where regions of the ectoplasmic face of the membrane are brought into close apposition. In the case of clathrin-coated vesicles, a specific GTP-binding protein, dynamin, plays a critical role in causing scission of the vesicles (9, 10) by constricting the neck of the bud through a conformational change that accompanies hydrolysis of GTP (11). A similar role has been assigned to dynamin in the severing of poly(IgA)-containing vesicles from the TGN of hepatocytes (12). On the other hand, scission of the COPI-coated vesicles involved in intra-Golgi transport takes place without a requirement for GTP hydrolysis but involves, in some unknown way, the participation of a long chain fatty acyl CoA (13), which is not, however, a requirement for the scission of COPII-coated vesicles from the endoplasmic reticulum (1).

We have previously studied the formation of COPI-coated vesicles containing the vesicular stomatitis virus envelope glycoprotein (VSV-G) from the TGN of Golgi fractions prepared from VSV-infected cells and were able to experimentally dissect this process into the two successive stages of coat assembly/bud formation and vesicle scission (14). Coat assembly, triggered by activation of Arf with GTP[γS], could be effected at 20°C but scission of coated buds from the recovered membranes required a higher temperature of incubation (37°C) and the presence of cytosolic proteins, although it proceeded without an energy supply or the addition of activating nucleoside triphosphates (14). The nature of the cytosolic proteins involved in scission and the mechanism by which they promote the lipid bilayer modifications necessary for it to occur are yet to be elucidated.

A role of the phosphatidylinositol transfer protein (PITP) in vesicular transport out of the Golgi apparatus was first suggested by the finding that in Saccharomyces cerevisiae the SEC14 gene, which when mutated leads to a block in secretion and to an expansion of the late Golgi compartment (15), encodes the yeast PITP (16). It was originally suggested that Sec14p serves as a sensor of the phospholipid composition of Golgi membranes that in its phosphatidylcholine (PC) form suppresses the synthesis of this phospholipid, thus maintaining a phosphatidylinositol (PI)/PC ratio sufficiently high for vesicular flow out of the Golgi apparatus to take place (17). More recent evidence indicates that the PI and PC forms of Sec14p, through independent pathways, promote the maintenance of high levels of diacylglycerol in Golgi membranes that were proposed to be necessary for proper function of the secretory pathway (18).

In mammalian systems, PITP has been implicated in providing the PI necessary for the synthesis of phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate (PIP2), which is necessary for the regulated exocytosis of secretory granules in both permeabilized PC12 pheochromocytoma cells (19) and granulocytes (20, 21). There is also considerable other evidence for a role of PI metabolites in regulating membrane traffic (22) and, most notably, a PI-3 kinase (Vps 34) has been found to be essential for sorting in the Golgi of proteins destined to the yeast vacuole (23). Recent studies have shown that PITP is a limiting cytosolic factor in the in vitro production of secretory vesicles from PC12 cell Golgi membranes (24, 25) and that in a hepatocyte cell-free system it acts synergistically with PI-3 kinase to stimulate the in vitro production from TGN membranes of exocytic vesicles containing the poly(IgA) receptor (26, 27).

Because the membrane fusion event required for vesicle scission is likely to follow a remodeling of the lipid bilayer, we investigated the participation of the PITP in this process. In this paper, we report that in its PI-loaded form this phospholipid transfer protein plays an essential role in the scission of COPI-coated vesicles from the TGN. When loaded with PI, PITP is able to vesiculate uncoated Golgi membranes in an uncontrolled fashion. In the cytosol, however, other proteins suppress the uncontrolled vesiculating properties of PITP and limit its action to the sites where COPI-coated buds are severed from the Golgi membranes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In Vitro Generation of TGN-Derived Vesicles.

Cytosolic Protein Subfractions.

Rat liver (28) cytosolic protein subfractions were obtained that precipitated at either 40% ammonium sulfate (AS) saturation (F0–40AS) or between 40% and 100% saturation (F40–100AS). They were resuspended in 20 mM Hepes-KOH (pH 7.3), 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, dialyzed against that buffer, clarified by centrifugation, concentrated (to 100 mg/ml) by ultrafiltration, and stored at −80°C in small aliquots.

Charging Sec14p with Phospholipids.

Liposomes containing PI or PC (Avanti Polar Lipids) were incubated with recombinant hexahistidine-tagged Sec14p (29) at a ratio of 1 mg of protein to 2.5 mg of phospholipid. The protein was recovered using a nickel column, dialyzed, and concentrated (to 20 mg/ml) by ultrafiltration. Phospholipid analysis revealed that: (i) Sec14p purified from Escherichia coli contained PG; (ii) PG could no longer be detected in purified Sec14p samples loaded with either PI or PC; and (iii) the phospholipid content of PI-Sec14p and PC-Sec14p was approximately 30 μg per mg of protein, corresponding to a phospholipid to protein ratio of 1:1 (30).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A Golgi fraction containing the [35S]methionine labeled and sialylated VSV-G protein obtained from virus-infected MDCK cells was used for in vitro vesicle generation. In this system, COPI-coated vesicles containing the VSV-G protein are generated during an incubation of the Golgi at 37°C in a process that requires a supply of cytosolic proteins and is promoted by the GTP analogues GTP[γS] or guanylyl-imidodiphosphate. When the vesicles are generated in the presence of ATP or GTP, uncoating takes place and only naked vesicles accumulate (14, 28, 31).

The Cytosol Contains a Latent, N-ethylmaleimide- (NEM) Sensitive, Nucleotide-Independent Golgi-Vesiculating Activity That Is Necessary for Normal Vesicle Generation.

To identify cytosolic proteins necessary for the in vitro generation of TGN-derived vesicles, we prepared two complementary protein subfractions from rat liver cytosol by AS precipitation, one (F0–40AS) that precipitated at 40% AS saturation, and another (F40–100AS) that was recovered from the 40% AS supernatant by precipitation at 100% AS saturation. The first fraction contained 20% of the total protein and essentially all of the β-COP in the cytosol and the second fraction contained the remaining protein, including essentially all of the Arf (not shown). When tested separately in the post-Golgi vesicle generation assay, the F40–100AS fraction was inactive but, surprisingly, the F0–40AS fraction was highly active in promoting the vesiculation of Golgi membranes even when an energy-generating system or nucleoside triphosphates (e.g., ATP, GTP, or GTP[γS]) were not provided (Fig. 1A). Sedimentation analysis (Fig. 1A, inset) and electron microscopy (Fig. 2b) indicated that the vesicles produced by the F0–40AS fraction were similar to the (uncoated) ones produced with complete cytosol and ATP (Fig. 2a), varying in size from 60 to 200 nm.

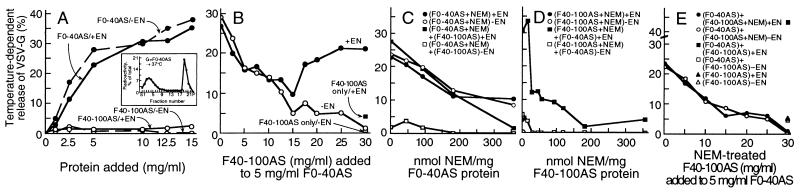

Figure 1.

A latent, NEM-sensitive, Golgi-vesiculating activity that participates in normal vesicle generation is present in the cytosol. (A) Nucleotide-independent Golgi-vesiculating activity of the F0–40AS subfraction. Golgi fractions were incubated for 60 min at either 37°C or 4°C, with (+EN) or without (−EN) an energy-generating system, in the presence of varying concentrations of either the F0–40AS or F40–100AS cytosolic subfractions and the temperature-dependent release of labeled VSV-G protein was measured. Inset, Sucrose gradient profile of labeled VSV-G protein released during an incubation with F0–40AS (15 mg/ml). Each point represents the average from four experiments using different preparations of F0–40AS. (B) The F40–100AS subfraction suppresses the nucleotide-independent vesiculating activity of F0–40AS and, when recombined with it, restores nucleotide-dependent vesicle generation (+EN). Assays were carried out as in A with F0–40AS (5 mg/ml) supplemented with varying amounts of the F40–100AS, with or without an energy-generating system, as indicated. (C and D) The nucleotide-dependent formation of TGN-derived vesicles requires at least two NEM-sensitive cytosolic factors, one of which is also necessary for the nucleotide-independent process of vesicle release. (C) Aliquots of F0–40AS were treated (10 min at 0°C) with varying amounts of NEM followed by addition of a 2-fold molar excess of DTT. They were then used (5 mg/ml) to support vesicle release with or without F40–100AS (25 mg/ml) in the presence or absence of an energy supply. (D) F40–100AS was treated with varying amounts of NEM, as described in C, and used (25 mg/ml) to support vesicle release, with or without the addition of F0–40AS (5 mg/ml) in the presence or absence of an ATP supply. (E) The suppressing factor in F40–100AS is not sensitive to NEM. F40–100AS was treated (0°C for 10 min) with NEM (175 nmol NEM/mg protein) or mock treated with control buffer, followed by the addition of a 2-fold molar excess of DTT. Vesicle release was measured after incubation of the Golgi membranes with various concentrations of NEM-treated or control F40–100AS, with or without F0–40AS (5 mg/ml), in the presence or absence of an ATP supply as indicated.

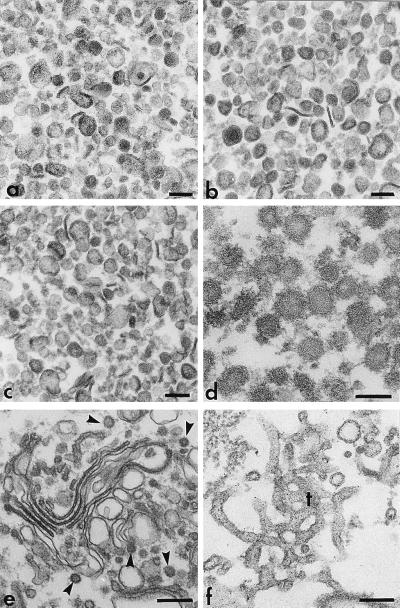

Figure 2.

Naked and coated vesicles released in vitro by PITP. (a–c) Naked vesicles generated from Golgi membranes by incubation (37°C, 60 min) with total liver cytosolic proteins and ATP (a), F0–40AS (5 mg/ml, b), or PI-Sec14p (1 mg/ml, c). The vesicles were purified as previously described (28). (d) Purified COPI-coated vesicles released from Golgi membranes that, after priming for coat assembly/bud formation (14), were reincubated at 37°C for vesicle scission with PI-Sec14p (1 mg/ml) and F40–100AS (25 mg/ml). (e and f) Whereas incubation (30 min at 20°C) of Golgi membranes for coat assembly with liver cytosolic proteins and guanylyl-imidodiphosphate (100 μM) leads to the production of coated buds (arrowheads) on stacked cisternae (e), a similar incubation with PI-Sec14p (1 mg/ml) leads to extensive tubulation of the Golgi membranes (f). All samples were recovered by sedimentation (10,000 × g for 10 min), fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde and OsO4, stained with tannic acid, and processed for routine electron microscopy. Bars, 100 nm (a–d) or 200 nm (e and f).

We, therefore, concluded that a latent vesiculating activity is present in the cytosol, but is normally suppressed by components recovered in the F40–100AS protein fraction. This was demonstrated directly when increasing amounts of F40–100AS were added to a constant amount of F0–40AS (Fig. 1B). When high levels of the F40–100AS were added, so as to reconstitute the normal protein composition of the cytosol, not only was the nucleotide-independent vesicle release totally suppressed, but the normal nucleotide-dependent vesicle generation activity was fully reconstituted (Fig. 1B). When, instead of an energy-generating system, GTP[γS] was used to promote the activation of Arf in the reconstituted cytosol, normal amounts of the TGN-derived, VSV-G containing vesicles, previously shown to be COPI-coated (31), were produced (not shown).

Since we have previously shown (28) that the cytosol contains one or more NEM-sensitive factors that are required for vesicle generation, we examined the effect of that alkylating agent on both cytosolic subfractions (Fig. 1 C–E). We found that the nucleotide-independent vesiculating activity of the F0–40AS was suppressed by NEM treatment, and this occurred in close parallel with the loss of capacity of this fraction to complement the F40–100AS in promoting the nucleotide-dependent vesicle release (Fig. 1C). NEM treatment of F40–100AS also eliminated its capacity to complement F0–40AS in the nucleotide-dependent vesicle-generating assay (Fig. 1D) but did not affect its capacity to suppress the uncontrolled nucleotide-independent vesiculating activity of F0–40AS (Fig. 1E). The latter suppressing capacity, however, was eliminated by protease treatment of F40–100AS (not shown).

Taken together, the results shown in Fig. 1 suggest that the uncontrolled nucleotide-independent vesiculating activity recovered in the F0–40AS fraction normally functions in cooperation with regulatory components present in F40–100AS to promote the physiological process of nucleotide-dependent formation and release of the Golgi-derived vesicles that carry the VSV-G protein. A likely role for the activity in the F0–40 AS fraction in normal vesicle generation would be to operate after the formation of coated buds to induce the periplasmic fusion of the lipid bilayers necessary to sever the emerging vesicle from the donor membrane. When coat assembly cannot take place (i.e., during incubation with F0–40AS alone, which lacks Arf), the activity would generate vesicles by severing tubules (32) that form from Golgi cisternae during the in vitro incubation (Fig. 2f).

When Added to NEM-Treated F0–40AS, Sec14p, the Yeast PITP Can Restore the Capacity of That Fraction to Complement the F40–100AS in Promoting the Nucleotide-Dependent Formation of Golgi-Derived Vesicles.

The coat-, nucleotide-, and energy-independent activity present in the F0–40AS is not specific to liver cytosol, but could be demonstrated in cytosolic protein fractions obtained from kidney, brain, and MDCK cells, and it did not have the capacity to induce the vesiculation of the rough endoplasmic reticulum in permeabilized cells (not shown). Moreover, the activity is due to a protein component, since it could be eliminated by trypsin treatment (not shown).

Recent evidence indicates that PITP plays a role in the formation of TGN-derived immature secretory granules and constitutive secretory vesicles (25, 27). Since the mammalian PITP is NEM sensitive (33), we determined whether it represents one of the NEM-sensitive factors required for nucleotide-dependent vesicle generation that we detected in the two cytosolic subfractions. Indeed, we found that Sec14p, the yeast PITP (16), could replace the NEM-sensitive component in the F0–40AS, but not that in the F40–100AS, when the two fractions were recombined to promote nucleotide-dependent vesicle generation (Fig. 3A). Since Sec14p, at the concentration used in this experiment (0.1 mg/ml), did not restore the nucleotide-independent vesiculating activity to an NEM-inactivated F0–40AS (Fig. 3B), we also tested the effect of higher concentrations (Figs. 3B and 4A). Surprisingly, we found that at concentrations higher than 0.1 mg/ml, PI-Sec14p by itself, but not PC- or PG-loaded Sec14p, caused the extensive nucleotide-independent vesiculation of Golgi membranes and the concomitant release of the VSV-G protein (Fig. 4A). This vesiculation could not be effected by PI alone, since PI-containing liposomes, even at concentrations as high as 1 mg/ml (≈30-fold higher than the concentration of PI contributed by 1 mg/ml of PI-Sec14p), did not cause any vesiculation (not shown). The vesicles produced in the presence of PI-Sec14p had sedimentation properties (Fig. 4A, inset) and morphological characteristics (Fig. 2c) similar to those of vesicles generated by the F0–40AS fraction (Fig. 2b). These observations suggest that the incorporation into the membranes of relatively large amounts of PI destabilizes them, causing their breakdown into vesicles of somewhat variable size. Electron microscopy revealed that during an incubation at 20°C (a temperature which does not allow for vesicle formation to take place) with either PI-Sec14p (Fig. 2f) or F0–40AS (not shown), Golgi cisterna became highly tubulated, suggesting that the tubulated domains break down into vesicles during the subsequent 37°C incubation. In contrast to its effect on Golgi membranes, PI-Sec14p did not have the capacity to induce the vesiculation of endoplasmic reticulum or mitochondrial membranes in permeabilized cells (C. De Lemos-Chiarandini, unpublished observations) and caused a very limited vesiculation of purified rough microsomes containing the labeled viral glycoprotein (not shown).

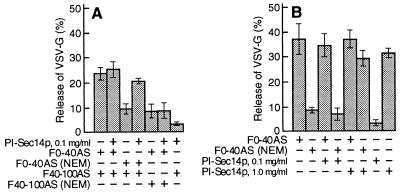

Figure 3.

The NEM-sensitive factor in F0–40AS can be replaced by the yeast PITP, Sec14p. (A) Cytosolic protein subfractions were mock-treated or treated with NEM (350 nmol NEM/mg protein for F0–40AS and 75 nmol NEM/mg protein for F40–100AS) and used as indicated (2 mg/ml of F0–40AS and/or 8 mg/ml of F40–100AS), with or without PI-Sec14p (0.1 mg/ml), for ATP-dependent vesicle generation. (B) Nucleotide-independent vesicle generation assays were carried out in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of PI-Sec14p with either mock-treated (F0–40AS) or NEM-treated (350 nmol NEM/mg protein) F0–40AS (5 mg/ml). In A and B, each point represents the mean (±SD) of four determinations.

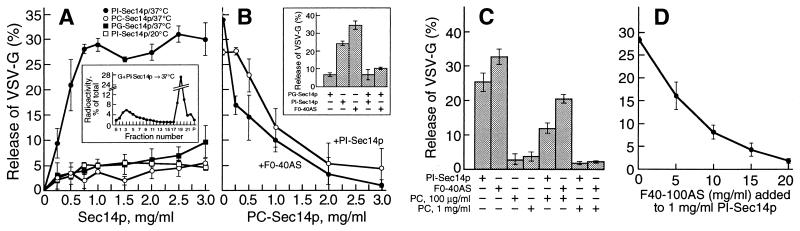

Figure 4.

PI-Sec14p vesiculates TGN membranes. (A) Golgi membranes (0.25 mg/ml) were incubated (60 min at 37°C or 20°C, as indicated) with varying concentrations of Sec14p charged with either PI, PC, or PG. Inset, Sucrose gradient profile of released VSV-G protein after incubation with PI-Sec14p (1 mg/ml). (B) PC- and PG-charged Sec14p prevent the vesiculation caused by PI-Sec14p (1 mg/ml) or F0–40AS (5 mg/ml). Vesicle generation reactions were carried out in the absence of nucleotides with either PI-Sec14p or F0–40AS and the indicated concentrations of PC-Sec14p. Inset, Incubations were carried out as in A with either PI-Sec14p (1 mg/ml) or F0–40AS (5 mg/ml) in the presence or absence of PG-Sec14p (3 mg/ml). (C) The addition of PC-containing liposomes to PI-Sec14p (1 mg/ml) or to F0–40AS (5 mg/ml) abolishes their capacity to vesiculate Golgi membranes, as expected from the replacement of PI in PITP by PC. Vesicle release assays were carried out with PI-Sec14p (1 mg/ml) or F0–40AS fraction (5 mg/ml) and the indicated concentrations of PC-containing liposomes. (D) F40–100AS abolishes the PI-Sec14p-mediated vesiculation of TGN membranes. Incubations for vesicle generation were carried out with PI-Sec14p (1 mg/ml) and various amounts of F40–100AS. (A–D) Each point represents the average (±SD) from three determinations using different Sec14p preparations.

Because, unlike PI-Sec14p, PC-loaded Sec14p showed no Golgi-vesiculating activity, we determined whether the two forms of phospholipid-loaded PITP had antagonistic effects. Indeed, the presence of PC-Sec14p countered the nucleotide-independent vesiculating activity of PI-Sec14p and, at sufficiently high concentrations, totally eliminated it (Fig. 4B). Strikingly, PC-Sec14p exerted a similar inhibitory effect on the nucleotide-independent vesiculating activity of F0–40AS (Fig. 4B), suggesting that the latter is also due to a PI-loaded form of the endogenous PITP. Similar inhibitory effects were obtained with PG-Sec14p (Fig. 4B, inset). That the inhibitory effects of the PC- or PG-bound forms of Sec14p are due to the capacity of the PITP to transfer its phospholipid moieties to the Golgi membrane was shown by the fact that—although preincubation of the Golgi fraction with high concentrations of PC-liposomes did not reduce the subsequent vesiculation induced by PI-Sec14p (not shown)—the presence of PC-containing liposomes at sufficient concentrations during an incubation with PI-Sec14p or F0–40AS effectively abolished the vesiculating effects of the latter two agents (Fig. 4C). It seems likely that the counteracting effects of the PI and the PC forms of Sec14p are due to their opposite effects on the ratio of the two phospholipids in the Golgi membranes.

The Vesiculating Activity of PI-Sec14p Is Suppressed by a Component of the F40–100AS Fraction.

Because the uncontrolled vesiculating activity of F0–40AS was suppressed by F40–100AS, we determined whether the latter cytosolic protein subfraction has a similar effect on pure recombinant PI-Sec14p. This was, indeed, the case (Fig. 4D) and, like the capacity to suppress the vesiculating activity of the F0–40AS, the suppression of the PI-Sec14p-vesiculating activity by F40–100AS was eliminated by protease treatment of the latter, but not by NEM treatment (not shown). Sec14p and the mammalian PITP, although functionally equivalent in phospholipid transport, show no primary sequence similarity (34). Hence, it is most likely that the suppressing activity in F40–100AS acts directly on the Golgi membranes rather than on the endogenous PITP itself or on the added Sec14p. Nevertheless, it is possible that the mammalian and yeast PITPs share conformational features recognized by the regulatory component in F40–100AS or that this interacts directly with the phospholipid moiety in PI-PITP.

PITP Acts by Promoting the Scission of Coated Buds from Golgi Membranes.

Using the two-stage assay for vesicle generation (14, 31), we found that both the F0–40AS and F40–100AS cytosolic protein subfractions contain components required for the scission of coated vesicles (Fig. 5A), but only the contribution of the former to the scission activity is inactivated by NEM (Fig. 5B). Moreover, PI-Sec14p could not only restore to the NEM-treated F0–40AS the activity necessary for scission (not shown) but, by itself, could completely replace that fraction in the scission reaction (Fig. 5C) to generate coated vesicles (Fig. 2d). PI-Sec14p, however, still required components of F40–100AS to promote scission of coated vesicles (compare Fig. 5 C and D), although by itself, like the F0–40AS (Fig. 5A), it could cause the nucleotide-independent vesiculation of uncoated portions of the Golgi membranes (Figs. 4A and 5D). In the presence of F40–100AS, PI-Sec14p could promote scission of coated vesicles in the two-step reaction at much lower concentrations (0.1–0.2 mg/ml) than those necessary to cause the nucleotide-independent vesiculation of uncoated Golgi membranes (Fig. 5C, inset). In contrast, PC-Sec14p or PI-containing liposomes could not replace F0–40AS in the scission reaction (Fig. 5C). These findings are consistent with a model in which PITP acts by replacing with PI other membrane phospholipids, most likely PC, at the necks of coated buds.

Figure 5.

PITP functions in vesicle scission. (A) Scission of coated buds requires at least two cytosolic components, one in F0–40AS and the other in F40–100AS. In a two-step vesicle generation assay, Golgi membranes (G) were incubated (30 min at 20°C) for coat assembly/bud formation with total liver cytosolic protein (LCP; 10 mg/ml) and guanylyl-imidodiphosphate (100 μM). The primed Golgi membranes were recovered and reincubated (60 min at 37°C) with either F0–40AS (2 mg/ml, open circles) or F40–100AS (8 mg/ml, closed circles) or a combination of both (open squares). The samples were then analyzed by sucrose gradient centrifugation. The values are the averages from six independent experiments. (B) Scission of coated buds requires an NEM-sensitive activity present in F0–40AS. Golgi membranes, primed as in A, were reincubated (60 min at 37°C) with a combination of mock- or NEM-treated (350 nmol NEM/mg protein) F0–40AS (2 mg/ml) and mock- or NEM-treated (175 nmol NEM/mg protein) F40–100AS (8 mg/ml), as indicated. Vesicle release was determined as in A, in four independent experiments. (C) F0–40AS can be replaced in the scission reaction by PI-Sec14p. Primed Golgi membranes were reincubated as in A, but with F40–100AS (20 mg/ml) either alone (closed squares) or along with either PI-Sec14p (1 mg/ml, open circles), PC-Sec14p (1 mg/ml, closed circles), or PI-containing liposomes (1 mg/ml, open squares). Each point represents the average from three (closed circles) or nine (other symbols) independent experiments using three different preparations of Sec14p. (Inset) Extent of coated vesicle scission as a function of PI-Sec14p concentration. (D) Vesiculation of uncoated portions of primed Golgi membranes by PI-Sec14p. Primed Golgi membrane fractions were incubated with either PI-Sec14p (1 mg/ml, open triangles), PC-Sec14p (1 mg/ml, closed triangles), or buffer alone (open circles). Points represent averages from three (closed triangles) or nine (other symbols) independent experiments using three different Sec14p preparations.

An Antibody to Mammalian PITP Inhibits Vesicle Scission.

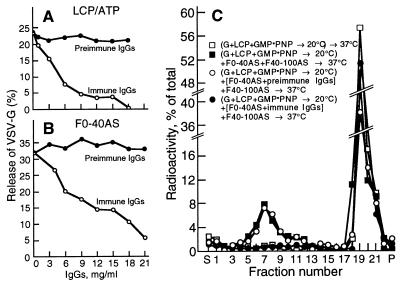

When tested in the standard vesicle generation system supported by a total liver cytosolic protein fraction and an energy supply (Fig. 6A) or in the nucleotide-independent system supported by the F0–40AS subfraction (Fig. 6B), specific antibodies (35) raised in rabbits to the recombinant human PITPα, but not an IgG fraction from preimmune serum, caused a dose-dependent inhibition of vesicle release that was nearly complete at sufficiently high IgG concentrations. In contrast, the antibodies did not decrease the number of vesicles recovered when added after the vesicle generation reaction had been completed, indicating that they did not cause a precipitation of the formed vesicles (not shown). In addition, when preincubated with the F0–40AS fraction, the specific antibodies blocked the capacity of that fraction to promote vesicle scission when recombined with an untreated F40–100AS and tested in a two-step assay (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

(A and B) Anti-PITPα antibodies inhibit the production of VSV-G-containing Golgi vesicles. (A) Assays were carried out with total liver cytosolic proteins (LCP; 10 mg/ml) and 1 mM ATP or with F0–40AS (5 mg/ml, B) pretreated for 60 min at 4°C with various concentrations of anti-PITPα or preimmune IgG from sera of a rabbit immunized with recombinant PITPα (35). Vesicle release is plotted as a function of the final concentration of IgG. (C) Anti-PITPα antibodies prevent the scission of COPI-coated vesicles from the TGN. Primed Golgi membranes were reincubated (60 min at 37°C) for coated vesicle scission with either buffer alone (open squares), a combination of F40–100AS (8 mg/ml) and F0–40AS (2 mg/ml, filled squares), or a combination of the two subfractions in which the F0–40AS had been preincubated (60 min at 4°C) with preimmune (open circles) or immune (filled circles) IgGs (20 mg/ml). The reaction mixtures were analyzed as in Fig. 5.

These observations suggest that F0–40AS contains only one NEM-sensitive factor necessary for the nucleotide-dependent formation of Golgi-derived vesicles and that this is a PITP which, when separated from regulatory components present in the F40–100AS, is capable of vesiculating Golgi membranes in a nucleotide- and coat-independent manner.

Because in our system vesicle generation can be supported by nonhydrolyzable GTP analogues in the nearly complete absence of ATP (14), we conclude that the action of PI-PITP in the final stage of vesicle scission does not require the conversion of its PI into phosphorylated derivatives, as is required in other systems (26, 27). Indeed, we have found that the capacity of PI-Sec14p to vesiculate Golgi membranes was unimpaired by the addition of an ATP-depleting system and that the PI-3 kinase inhibitor, wortmannin, at a concentration as high as 50 μM, had no effect on normal vesicle generation or on the nucleotide-independent process promoted by PI-Sec14p or F0–40AS (not shown), indicating that the formation of neither PIP nor PIP2 is obligatory for vesicle release. For these reasons, it seems likely that the effect of PITP results simply from the remodeling of the phospholipid bilayer in the vicinity of a coated bud that results from replacing a resident phospholipid with PI. This PI could, in principle, also serve as a substrate for local phospholipases that generate PI metabolites, such as phosphatidic acid or diacylglycerol, that have been implicated in vesicle generation (18, 36). During normal COPI-coated vesicle formation, PITP would then simply serve to transfer PI molecules from PI-rich membrane regions to sites of vesicle budding. In this function, PITP is likely to be aided by pilot or escort cytosolic proteins that target it to the appropriate delivery site and prevent its indiscriminate action on uncoated membrane regions. The participation of such regulatory proteins would account for the fact that 10-fold lower concentrations of PI-Sec14p are required to restore the capacity of NEM-treated F0–40AS to function in normal vesicle generation than are necessary to cause any nucleotide-independent vesiculation.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Chaojun Shi, Heide Plesken, Iwona Gumper, and Jody Culkin and the help of Myrna Cort and Antonio J. D. Rocha in preparing the manuscript. We are grateful to Dr. Justin Hsuan (University College, London, United Kingdom) for the gift of the plasmids encoding PITPα and β. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM43583.

ABBREVIATIONS

- TGN

trans-Golgi network

- VSV-G

vesicular stomatitis virus envelope glycoprotein

- PITP

phosphatidylinositol transfer protein

- PI

phosphatidylinositol

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PG

phosphatidylglycerol

- PIP2

phosphatidyl bisphosphate

- AS

ammonium sulfate

- NEM

N-ethylmaleimide

References

- 1.Barlowe C, Orci L, Yeung T, Hosobuchi M, Hamamoto S, Salama N, Rexach M F, Ravazzola M, Amherdt M, Schekman R. Cell. 1994;77:895–907. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serafini T, Stenbeck G, Brecht A, Lottspeich F, Orci L, Rothman J E, Wieland F T. Nature (London) 1991;349:215–220. doi: 10.1038/349215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donaldson J G, Finazzi D, Klausner R D. Nature (London) 1992;360:350–352. doi: 10.1038/360350a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Traub L M, Osatrom J A, Kornfeld S. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:561–573. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.3.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helms J B, Rothman J E. Nature (London) 1992;360:352–354. doi: 10.1038/360352a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stamnes M A, Rothman J E. Cell. 1993;73:999–1005. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90277-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pryer N K, Wuestehube L J, Schekman R. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:471–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.002351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirchhausen T, Bonifacino J S, Riezman H. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:488–495. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinshaw J E, Schmid S L. Nature (London) 1995;374:190–192. doi: 10.1038/374190a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takei K, McPherson P S, Schmid S L, De Camilli P. Nature (London) 1995;374:186–190. doi: 10.1038/374186a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sweitzer S M, Hinshaw J E. Cell. 1998;93:1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones S M, Howell K E, Henley J R, Cao H, McNiven M A. Science. 1998;279:573–577. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostermann J, Orci L, Tani K, Amherdt M, Ravazzola M, Elazar Z, Rothman J E. Cell. 1993;75:1015–1025. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90545-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simon J-P, Ivanov I E, Adesnik M, Sabatini D D. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:355–370. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.2.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novick P, Field C, Schekman R. Cell. 1980;21:205–215. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bankaitis V A, Aitkem J R, Cleves A E, Dowhan W. Nature (London) 1990;347:561–562. doi: 10.1038/347561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGee T P, Skinner H B, Whitters E A, Henry S A, Bankaitis V A. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:273–287. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.3.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kearns B G, McGee T P, Mayinger P, Gedvilaite A, Phillips S E, Kagiwada S, Bankaitis V A. Nature (London) 1997;387:101–105. doi: 10.1038/387101a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hay J C, Fisette P L, Jenkins G H, Fukami K, Takenawa T, Anderson R A, Martin T F J. Nature (London) 1995;374:173–177. doi: 10.1038/374173a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas G M, Cunningham E, Fensome A, Ball A, Totty N F, Truong O, Hsuan J J, Cockcroft S. Cell. 1993;74:919–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90471-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunningham E, Thomas G M, Ball A, Hiles I, Cockcroft S. Curr Biol. 1995;5:775–783. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Camilli P, Emr S D, McPherson P S, Novick P. Science. 1996;271:1533–1539. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schu P V, Takegawa K, Fry M J, Stack J H, Waterfield M D, Emr S D. Science. 1993;260:88–91. doi: 10.1126/science.8385367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuscher O, Lorra C, Bouma B, Wirtz K W, Huttner W B. FEBS Lett. 1997;419:271–275. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01471-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohashi M, Jan deVries K, Frank R, Snoek G, Bankaitis V, Wirtz K, Huttner W B. Nature (London) 1995;377:544–547. doi: 10.1038/377544a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones S M, Howell K E. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:339–349. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones S M, Alb J G, Jr, Phillips S E, Bankaitis V A, Howell K E. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10349–10354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon J-P, Ivanov I E, Shopsin B, Hersh D, Adesnik M, Sabatini D D. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16952–16961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skinner H B, McGee T P, McMaster C R, Fry M R, Bell R M, Bankaitis V A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:112–116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szolderits G, Hermetter A, Paltauf F, Daum G. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;986:301–309. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(89)90481-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon J-P, Shen T H, Ivanov I E, Gravotta D, Morimoto T, Adesnik M, Sabatini D D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1073–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cluett E B, Wood S W, Banta M, Brown W J. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:15–24. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helmkamp G M., Jr Chem Phys Lipids. 1985;38:3–16. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(85)90053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bankaitis V A, Fry M R, Cartee R T, Kagiwada S. Phospholipid Transfer Proteins. New York: Chapman–Hall; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cunningham E, Tan S K, Swigart P, Hsuan J, Bankaitis V A, Cockcroft S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6589–6593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ktistakis N T, Brown H A, Waters M G, Sternweis P C, Roth M G. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:295–306. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]