Abstract

We describe the first IMP metallo-β-lactamase in Aeromonas caviae: IMP-19, which differed from IMP-2 by a single amino acid change (Arg to Ala at position 38). blaIMP-19 was found within a class 1 integron located on a 35-kb plasmid. This is also the first description of an IMP producer in France.

In the last few years, many acquired metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) have been detected worldwide; these IMP, VIM, SPM, and GIM types have very broad substrate profiles, including carbapenems (20). The first IMP-type MBL was described in Japan in 1988 (21). Since then, 23 IMP variant enzymes have been reported (http://www.lahey.org/studies/). IMP producers have now been detected worldwide: in Europe (3, 4, 14, 17, 19), South America (5), Australia (13), and Canada (7) and also, more recently, in the United States (8). So far, in France, IMP producers have not yet been detected. Nevertheless, the frequency of such isolates may be underestimated: several clinical isolates carrying a cryptic blaIMP gene demonstrated low-level carbapenem resistance (MIC ≤ 4 μg/ml) (16, 24). In this study, we describe the first isolate from France harboring an acquired blaIMP gene.

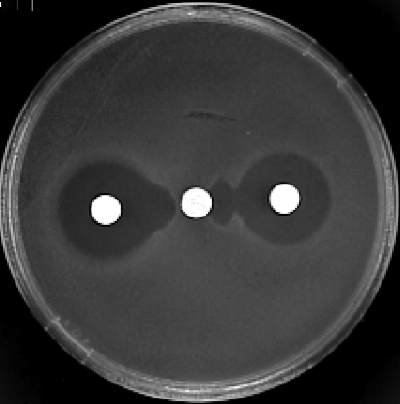

The Aeromonas caviae isolate (A324R) was recovered from a stool sample from an 8-year-old boy hospitalized for acute diarrhea, the final diagnosis being a celiac disease. The child had never been hospitalized before and had not received any antibiotic therapy for at least 6 months. The strain A324R was identified by using the API 20NE system (BioMérieux, Marne-la-Coquette, France) and by 16S rRNA and rpoB gene sequencing. Susceptibility testing by the disk diffusion method and the determination of the MICs by the standard broth dilution method were based on CLSI criteria (2). On the antibiogram from the disk diffusion method, A324R was characterized as being resistant to most β-lactams, except aztreonam and imipenem (inhibition zones of 24 and 27 mm in diameter, respectively). The MBL production was assessed by a positive double-disk test of synergy between a disk containing ceftazidime and a disk containing EDTA (10 μl; 500 mM) either alone or in combination with β-mercaptoethanol (2 μl) (Fig. 1) (1). The isoelectric point (pI) of the MBL was determined by analytical isoelectric focusing (12). The detection of β-lactamase activity was performed by a substrate-overlaying procedure (10). In all steps (from the bacterial growth to the gel preparation), 0.1 mM ZnCl2 was added. A324R produced a β-lactamase with a pI of 8.2. A plasmid of 35 kb (pJDB2) was extracted by an alkaline lysis method (15), but all attempts at conjugation failed. Escherichia coli DH5α transformed with pJDB2 also produced a β-lactamase of pI 8.2. Acquired MBL genes are inserted mostly in integrons, especially class 1 integrons (20). To search for the presence of such a class 1 integron, we performed PCR analysis of the total DNA from A324R and E. coli DH5α(pJDB2) with primers L1 and R1 (11). A fragment of 2.8 kb was obtained, and both strands were sequenced with an Applied Biosystems 373A sequencer according to the manufacturer's instructions. By using a set of primers (Table 1), the structure of this class 1 integron was deduced. There was an insertion sequence (ISAeca1) belonging to the IS30 family located immediately downstream of the cassette integration site attI1. ISAeca1 was followed by a first cassette that carried an aacA4 determinant identical to the cassette found in the integron In42 and in many integrons harboring blaIMP genes (14, 18). The aacA4 determinant was located upstream of the blaIMP-19 cassette. The 72-bp attC recombination site of the blaIMP-19-containing cassette was identical to those of the cassettes carrying blaIMP-2 and blaIMP-8 (14, 22). The amino acid sequence deduced according to the numbering scheme of Galleni et al. (6) revealed that IMP-19 was similar to IMP-2 (Arg for IMP-2 and Ala for IMP-19 at position 38) and IMP-8 (Gly for IMP-8 and Val for IMP-19 at position 254).

FIG. 1.

A324R: synergy between disks containing ceftazidime (center) and EDTA (10 μl; 500 mM) alone (left) or in combination with β-mercaptoethanol (2 μl) (right).

TABLE 1.

Primers used for PCRs

| Amplified DNA | Primer | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′ to 3′) | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable region of class 1 integrons | L1 | GGCATCCAAGCAGCAAGC | U49101 |

| R1 | AAGCAGACTTGACCTGAT | ||

| intI1 | Int-IN | TGTCGTTTTCAGAAGACGG | U49101 |

| IntA-R | ATCATCGTCGTAGAGACG | ||

| IntB-F | GTCAAGGTTCTGGACCAG | ||

| Int-out-F | GTAGAACAAGCAGGCATC | ||

| Int-out-R | GAAACGGATGAAGGCACG | ||

| aac(6′)-Ib | Aac6′Ib-F | ACTGAGCATGACCTTGCG | AY878717 |

| Aac6′Ib-R | TGTTCGCTCGAATGCCTG | ||

| blaIMP | Imp-F | GTTTTATGTGTATGCTTCC | AB184976 |

| Imp-R | AGCCTGTTCCCATGTAC | ||

| Imp-out-R | CCTTCTTCAAGCTTCTCG | ||

| 3′ conserved segment region | Qac-F | TCGCAATAGTTGGCGAAG | U49101 |

| Qac-R | AGCTTTTGCCCATGATGC | ||

| Sul-F | GACGGTGTTCGGCATTCT | ||

| Sul-R | TGAAGGTTCGACAGCACG | ||

| Orf5-F | GGTGATATCGACGAGGTT | ||

| Orf5-R | GATTTCGAGTTCTAGGCG | ||

| blaIMP-19 cloning primers | Sub-IMP19-EcoRI-F | GGGGAATTCTTAGAAAAGGGCAAGTATG | |

| Sub-IMP19-XbaI-R | GGGTCTAGATCACCGCCTTGTTAGAAAT |

The blaIMP-19 gene was subcloned into vector pK18, and the recombinant strain E. coli DH5α(pIP19) was selected on kanamycin (30 μg/ml) and ceftazidime (4 μg/ml). The β-lactam MICs (determined by broth dilution) for A324R, E. coli DH5α(pIP19), E. coli DH5α(pJDB2), and E.coli DH5α are reported in Table 2. IMP-19 production conferred a high level of resistance to ceftazidime, cefoxitin, and cefazoline and only reduced susceptibility to carbapenems. A324R was much more resistant to ticarcillin than to piperacillin (MICs of 1,024 and 2 μg/ml, respectively). There was discordance between the results of susceptibility testing for imipenem: by the disk diffusion method, A324R was categorized as susceptible (27-mm-diameter zone of inhibition), whereas by the determination of the MIC by broth dilution, A324R was categorized as resistant (MIC, 16 μg/ml).

TABLE 2.

MICs of β-lactams for A. caviae A324R, the transformant E. coli DH5α(pJDB2), the recombinant E. coli DH5α(pIP19), and E.coli DH5α

| β-lactam | MIC (μg/ml) for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. caviae A324R | E. coli DH5α(pJDB2) | E. coli DH5α(pIP19) | E. coli DH5α | |

| Ticarcillin | 2,048 | 512 | 1,024 | 4 |

| Piperacillin | 256 | 8 | 2 | 1 |

| Cefazoline | 512 | 256 | 512 | 2 |

| Cefoxitin | 1,024 | 128 | 512 | 4 |

| Aztreonam | 8 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Ceftazidime | 1,024 | 256 | 512 | ≤1 |

| Clavulanatea | 512 | 256 | 256 | ≤1 |

| Tazobactama | 1,024 | 256 | 256 | ≤1 |

| Imipenem | 16 | 4 | 8 | 0.5 |

| Meropenem | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | ≤0.25 |

Clavulanate and tazobactam were used at 2 and 4 μg/ml, respectively.

The difficulty of detecting IMP-2 variant producers has already been pointed out (23), and this characteristic is fully consistent with the findings of our study. The recombinant strain E. coli DH5α(pIP19) was used to determine the enzymatic parameters of IMP-19. The bacteria were disrupted by ultrasonic treatment. The supernatant was loaded onto an SP Sepharose column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) equilibrated with 50 mM MES (morpholineethanesulfonic acid)-NaOH (pH 6.0). The elution was performed with a linear NaCl gradient (0 to 500 mM). The β-lactamase-containing elution peak fraction was supplemented with 5 mM ZnCl2, loaded onto a Superose 12 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and eluted with the buffer 20 mM MES-NaOH-100 mM NaCl (pH 6.0). The level of purity was estimated at >97% by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

The Michaelis constant (Km) and catalytic activity (kcat) were determined three times with purified extracts by using a computerized microacidimetric method (9). The variation coefficients showed a maximum variation of 10%. The enzymatic parameters of IMP-19 (Table 3) were overall very different from those of IMP-2. The hydrolytic activities (kcats) of IMP-19 were much higher for penicillins than those of IMP-2, especially for amoxicillin (kcat of 456 versus 23 s−1). The hydrolytic efficiency of IMP-19 for amoxicillin and ticarcillin was 10- to 15-fold higher than that of IMP-2. IMP-19 had greater affinity for ceftazidime than IMP-2 (Km of 20 versus 111 μM) but lower hydrolytic activity, resulting in a twofold-higher kcat/Km ratio for IMP-19. Compared to that of IMP-2, the hydrolytic efficiency of IMP-19 was rather poor for carbapenems, despite an excellent affinity for meropenem (7 μM). Unfortunately, the IMP-8 enzymatic parameters are not available for comparison.

TABLE 3.

Kinetic parameters of purified IMP-19a

| Substrate | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (μM−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzylpenicillin | 1,011 | 206 | 4.91 |

| Amoxicillin | 456 (23) | 207 (110) | 2.20 (0.21) |

| Ticarcillin | 683 (252) | 140 (700) | 4.88 (0.36) |

| Piperacillin | 41.2 | 148 | 0.28 |

| Cephalothin | 11.0 | 76 | 0.14 |

| Cefuroxime | 16.4 | 95 | 0.17 |

| Cefoxitin | 9.7 (7) | 33 (7) | 0.29 (1.0) |

| Cefotaxime | 20.1 | 61 | 0.33 |

| Cefpirome | 14.3 | 48 | 0.30 |

| Ceftazidime | 6.4 (21) | 20 (111) | 0.32 (0.19) |

| Imipenem | 26.5 (22) | 100 (24) | 0.26 (0.92) |

| Meropenem | 1.0 (1) | 7 (0.3) | 0.14 (3.3) |

| Aztreonam | <0.1 | NDb | ND |

Values in parentheses are those for IMP-2 (14).

ND, not determined.

A324R had no clinical significance. Nevertheless, this is the first report of an IMP producer in France and the first report of IMP production by Aeromonas. The present findings confirm that the environmental reservoir of blaIMP genes is widespread.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the integron reported in this paper has been assigned the GenBank accession number EF118171.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rolande Perroux for technical assistance and Dominique de Briel for his help with bacterial identification.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arakawa, Y., N. Shibata, K. Shibayama, H. Kurokawa, T. Yagi, H. Fujiwara, and M. Goto. 2000. Convenient test for screening metallo-β-lactamase-producing gram-negative bacteria by using thiol compounds. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:40-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2007. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 15th informational supplement (M100-S17). Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 3.Da Silva, G. J., M. Correia, C. Vital, G. Ribeiro, J. C. Sousa, R. Leitao, L. Peixe, and A. Duarte. 2002. Molecular characterization of blaIMP-5, a new integron-borne metallo-β-lactamase gene from an Acinetobacter baumannii nosocomial isolate in Portugal. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 215:33-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Docquier, J. D., M. L. Riccio, C. Mugnaioli, F. Luzzaro, A. Endimiani, A. Toniolo, G. Amicosante, and G. M. Rossolini. 2003. IMP-12, a new plasmid-encoded metallo-β-lactamase from a Pseudomonas putida clinical isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1522-1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gales, A. C., M. C. Tognim, A. O. Reis, R. N. Jones, and H. S. Sader. 2003. Emergence of an IMP-like metallo-enzyme in an Acinetobacter baumannii clinical strain from a Brazilian teaching hospital. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 45:77-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galleni, M., J. Lamotte-Brasseur, G. M. Rossolini, J. Spencer, O. Dideberg, and J. M. Frère. 2001. Standard numbering scheme for class B β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:660-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibb, A. P., C. Tribuddharat, R. A. Moore, T. J. Louie, W. Krulicki, D. M. Livermore, M. F. Palepou, and N. Woodford. 2002. Nosocomial outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa with a new blaIMP allele, blaIMP-7. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:255-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanson, N. D., A. Hossain, L. Buck, E. S. Moland, and S. K. Thomson. 2006. First occurrence of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolate in the United States producing an IMP metallo-β-lactamase, IMP-18. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2272-2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Labia, R., J. Andrillon, and F. Le Goffic. 1973. Computerized microacidimetric determination of β-lactamase Michaelis-Menten constants. FEBS Lett. 33:42-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labia, R., M. Barthélemy, and J. M. Masson. 1976. Multiplicité des bêta-lactamases: un problème d'isoenzymes? C. R. Acad. Sci. 283D:1597-1600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levesque, C., L. Piche, C. Larose, and P. H. Roy. 1995. PCR mapping of integrons reveals several novel combinations of resistance genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:185-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathew, A., A. M. Harris, M. J. Marshall, and G. W. Ross. 1975. The use of analytical isoelectric focusing for detection and identification of beta-lactamases. J. Gen. Microbiol. 88:169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peleg, A. Y., C. Franklin, J. Bell, and D. W. Spelman. 2004. Emergence of IMP-4 metallo-β-lactamase in a clinical isolate from Australia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:699-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riccio, M. L., N. Franceschini, L. Boschi, B. Caravelli, G. Cornaglia, R. Fontana, G. Amicosante, and G. M. Rossolini. 2000. Characterization of the metallo-β-lactamase determinant of Acinetobacter baumannii AC-54/97 reveals the existence of blaIMP allelic variants carried by gene cassettes of different phylogeny. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1229-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 16.Senda, K., Y. Arakawa, S. Ichiyama, K. Nakashima, H. Ito, S. Ohsuka, K. Shimokata, N. Kato, and M. Ohta. 1996. PCR detection of metallo-β-lactamase gene (blaIMP) in gram-negative rods resistant to broad-spectrum β-lactams. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2909-2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toleman, M. A., D. Biedenbach, D. Bennett, R. N. Jones, and T. R. Walsh. 2003. Genetic characterization of a novel metallo-β-lactamase gene, blaIMP-13, harboured by a novel Tn5051-type transposon disseminating carbapenemase genes in Europe: report from the SENTRY worldwide antimicrobial surveillance programme. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:583-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toleman, M. A., D. Biedenbach, D. M. C. Bennett, R. N. Jones, and T. R. Walsh. 2005. Italian metallo-β-lactamases: a national problem? Report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55:61-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tysall, L., M. W. Stockdale, P. R. Chadwick, M. F. Palepou, K. J. Towner, D. M. Livermore, and N. Woodford. 2002. IMP-1 carbapenemase detected in an Acinetobacter clinical isolate from the UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:217-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsh, T. R., M. A. Toleman, L. Poirel, and P. Nordmann. 2005. Metallo-β-lactamases: the quiet before the storm? Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18:306-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watanabe, M., S. Iyobe, M. Inoue, and S. Mitsuhashi. 1991. Transferable imipenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:147-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan, J.-J., W. C. Ko, and J.-J. Wu. 2001. Identification of a plasmid encoding SHV-12, TEM-1, and a variant of IMP-2 metallo-β-lactamase, IMP-8, from a clinical isolate of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2368-2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan, J. J., W. C. Ko, S. H. Tsai, H. M. Wu, and J. J. Wu. 2001. Outbreak of infection with multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae carrying blaIMP-8 in a university medical center in Taiwan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4433-4439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan, J. J., W. C. Ko, C. L. Chuang, and J. J. Wu. 2002. Metallo-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates in a university hospital in Taiwan: prevalence of IMP-8 in Enterobacter cloacae and first identification of VIM-2 in Citrobacter freundii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:503-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]