Abstract

The phenolic diterpene totarol had good antimicrobial activity against effluxing strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Subinhibitory concentrations reduced the MICs of selected antibiotics, suggesting that it may also be an efflux pump inhibitor (EPI). A totarol-resistant mutant that overexpressed norA was created to separate antimicrobial from efflux inhibitory activity. Totarol reduced ethidium efflux from this strain by 50% at 15 μM (1/4× MIC), and combination studies revealed marked reductions in ethidium MICs. These data suggest that totarol is a NorA EPI as well as an antistaphylococcal antimicrobial agent.

Efflux is a common resistance mechanism employed by bacteria. Multidrug resistance (MDR) pumps can confer resistance to bile, hormones, and other substances produced by the host and may play a role in host colonization (24). The NorA MDR pump of Staphylococcus aureus effluxes a broad spectrum of compounds, including fluoroquinolones, quaternary ammonium compounds, ethidium bromide, rhodamine, and acridines (17). In addition to MDR pumps, there are those that are specific for a particular class of antibiotics; an example is TetK, which is also found in S. aureus and effluxes only tetracyclines.

There is significant interest in plant compounds which may inhibit bacterial efflux pumps. An example is the plant alkaloid reserpine, which inhibits both TetK and NorA (7, 21) but unfortunately is toxic at the concentrations required for this activity (17). An effective efflux pump inhibitor (EPI) could have significant benefits, including restoration of antibiotic sensitivity in a resistant strain (13) and a reduction in the dose of antibiotic required, possibly reducing adverse drug effects. It has also been demonstrated that use of an EPI with an antibiotic delays the emergence of resistance to that antibiotic (16). A new EPI lead compound (MP-601,205), which is in phase I clinical trials, has recently been described (15). A hybrid molecule of the synthetic MDR pump inhibitor INF55 (17) and the natural product berberine was effective in vivo in curing an enterococcal infection in a Caenorhabditis elegans nematode infection model (2). Therefore, the prospects for producing EPIs which could be used clinically are encouraging.

Conifer oleoresin, secreted as a defense mechanism against predators, has long been valued for its antiseptic properties. In this study, the phenolic diterpene totarol (Fig. 1) was isolated from the immature cones of Chamaecyparis nootkatensis. Here we demonstrate that totarol has both antibacterial and EPI activity against S. aureus, providing further evidence that effective EPI lead compounds can be isolated from plants.

FIG. 1.

Structure of totarol.

Unless stated otherwise, all reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Company Ltd., Dorset, United Kingdom. Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth was obtained from Oxoid and was adjusted to contain 20 mg/liter Ca2+ and 10 mg/liter Mg2+.

The strains of S. aureus used are listed in Table 1. Strains overexpressing various efflux-related resistance mechanisms were employed and will be referred to as “effluxing strains,” including strains XU212 (tetK), RN4220 (msrA), and SA-1199B (norA). SA-K1758 is a derivative of S. aureus NCTC 8325-4 having the norA gene deleted and replaced with an erm cassette (25). To help separate antimicrobial from efflux inhibitory activity, a totarol-resistant mutant of SA-K1758 (SA-K3090) was produced by employing gradient plates. The norA gene and promoter were amplified from SA-1199B and cloned into pCU1, producing pK364 (1). This plasmid was transduced into SA-K3090 using phage 85, resulting in SA-K3092 (6).

TABLE 1.

Study strains

| Strain | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| ATCC 25923 | Control strain | 7 |

| XU212 | Clinical isolate, has TetK efflux pump, erythromycin resistant | 7 |

| RN4220 (msrA) | Transformed with pSK265 into which the gene for the MsrA efflux protein has been cloned | 26 |

| SA-1199 | Clinical isolate, methicillin susceptible | 10 |

| SA-1199B | NorA-overproducing derivative of SA-1199, also has A116E GrlA substitution | 10, 11 |

| NCTC 8325-4 | Commonly used laboratory strain | |

| SA-K1758 | norA deletion mutant of NCTC 8325-4 | 25 |

| SA-K3090 | SA-K1758, resistant to totarol | This study |

| SA-K3092 | SA-K3090(pK364) | This study |

| EMRSA-15 | Clinical isolate, methicillin and erythromycin resistant | 27 |

Totarol was isolated from the immature cones of Chamaecyparis nootkatensis (Bedgebury Pinetum, Goudhurst, Kent), and a voucher specimen was placed in the herbarium at the School of Pharmacy (voucher specimen no. ECJS/008). Soxhlet extraction on 500 g of cones was carried out using 3.5 liters of solvents of increasing polarity: hexane, chloroform, acetone, and methanol. Vacuum-liquid chromatography was performed on 2 g of the chloroform extract using Merck Silica Gel 60 (VWR, Leicestershire United Kingdom), commencing elution with 100% chloroform with a gradient of 10% increments to 100% ethyl acetate. The solvent was then changed to ethyl acetate-acetone (50:50), followed by 100% acetone and finishing with acetone-methanol (50:50). Fraction 3 (852 mg) was subjected to preparative reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography using an XTerra MS C18 column (300 mm by 19 mm by 10 μm) (Waters, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom). Samples (65 mg) were eluted with acetonitrile-H2O (70:30) for 30 min, and the acetonitrile concentration was then increased in a gradient up to 100% over 5 min and held for 2 min. Four high-pressure liquid chromatography runs yielded 39.0 mg totarol.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis was carried out using an Agilent 6890 GC coupled to an Agilent 5973 mass selective detector. An HP-5ms capillary column of 30 m in length with a diameter of 250 μm was used with a nonpolar stationary phase of 5% phenylmethylsiloxane and a film thickness of 0.25 μm. Samples were introduced into the system using split injection with a split ratio of between 5:1 and 10:1 and an injector temperature of 250°C. Helium was used as the carrier gas at an average linear velocity of 50 cm/s. The initial oven temperature was 50°C, and the temperature was increased after 5 min at a rate of 5°C to a maximum of 300°C. The MS was run in EI mode. One-dimensional (1D) and 2D nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 500-MHz spectrometer and processed using XWin NMR 3.5 software. Samples were dissolved in deuterated chloroform, which was also used as the internal solvent standard. Extensive 1D and 2D NMR experiments and GC-MS facilitated the structure elucidation of the isolated diterpene (Fig. 1), and the spectral data were in close agreement with the literature values for totarol (23).

MIC and modulation assays were performed using a broth dilution technique as described previously (29). Totarol was assayed at half the MIC in modulation assays, and reserpine was used as a control. Checkerboard combination studies using ethidium bromide (EtBr) and totarol were performed as described previously (4). Totarol concentrations included in combination experiments were ≤1/4 of its respective MIC. Increasing concentrations of totarol and reserpine were assayed for their ability to inhibit EtBr efflux from SA-K3092 using methods exactly as previously described (12).

Totarol exhibited good antibacterial activity, having an MIC of 2 μg/ml against S. aureus ATCC 25923 and effluxing strains. EtBr MICs for NCTC 8325-4, SA-K1758 (norA null), SA-K3090, and SA-K3092 (plasmid-based norA overexpresser) were 6.25, 0.63, 0.63, and 100 μg/ml, respectively, demonstrating the marked increase in EtBr MIC associated with norA overexpression. The totarol MICs for these strains were 2.5, 1.25, 16, and 16 μg/ml, respectively, indicating that totarol is not a substrate for NorA.

At half the MIC, the modulatory activity of totarol against effluxing strains was comparable to that seen for reserpine (Table 2). Of particular note was the observation of a totarol-mediated eightfold reduction in the MIC of erythromycin against strain RN4220, which expresses the macrolide-specific MsrA pump, whereas reserpine had no activity as a modulator against this strain. No inhibitors of the MsrA pump have so far been reported; however, some caution must be exercised in defining totarol as an inhibitor of MsrA, as it has been suggested that the MsrA protein may not be an efflux pump (26).

TABLE 2.

Results of modulation assays for totarol and reserpine

| Test compound (concn, μg/ml) | MIC (μg/ml) of indicated drug for indicated strain with/without test compound (fold inhibition)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetracycline, XU212 (TetK) | Norfloxacin, SA1199B (NorA) | Erythromycin, RN4220 (MsrA) | |

| Totarol (1) | 128/32 (4) | 32/8 (4) | 128/16 (8) |

| Reserpine (20) | 128/32 (4) | 32/4 (8) | 128/128 (0) |

Isobolograms illustrating the effect of totarol on EtBr MICs of test strains are presented in Fig. 2. The effect of totarol on strains overexpressing NorA (SA-1199B and K3092) is evident and is consistent with an inhibitory effect on NorA function.

FIG. 2.

Isobolograms demonstrating the effect of totarol on EtBr MICs.

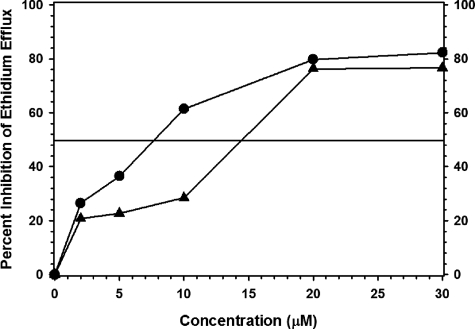

The activity of totarol against effluxing strains of S. aureus suggested that it may be an EPI. To test this possibility, a dose-response efflux inhibition assay was performed using SA-K3092 (Fig. 3). The concentration at which totarol inhibited EtBr efflux by 50% (IC50) (15 μM or 4.29 μg/ml) was approximately one-fourth of the MIC for this strain. Reserpine is a more efficient inhibitor of EtBr efflux in this test system, having an IC50 of 8 μM.

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of EtBr efflux in SA-K3092 by reserpine (•) and totarol (▴). The horizontal line indicates the IC50.

This is the first report of antibacterial and modulatory activities for totarol against effluxing strains of S. aureus. Efflux inhibition results using a mutant with an elevated totarol MIC indicated successful separation of antibacterial and modulatory activities. An IC50 for EtBr efflux at one-quarter of the MIC indicated that the antibacterial activity of totarol is not likely to be contributing to its activity as a modulator and that it does function as a weak EPI. Totarol's activity as a modulator has also been reported against mycobacteria. Mossa et al. (19) found the compound was active against several species (MIC, 2.5 μg/ml) and that at half of the MIC it caused an eightfold potentiation of isoniazid activity.

The antibacterial activity of totarol and its activity as a potentiator of methicillin activity against methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) have previously been reported (14, 20, 22). Various reductions in the MIC of methicillin against MRSA strains have been reported when used with totarol at half of the MIC. At least an 8-fold reduction in MIC, from >32 to 4 μg/ml, was noted by one group (22), but others observed a 16-fold reduction in MIC against one MRSA strain but only a 2-fold reduction against a different strain (20). For comparison, in this study we assayed totarol against the clinical isolate EMRSA-15 and found a 50-fold potentiation of oxacillin activity (data not shown). Nicolson et al. (22) studied the expression levels of PBP2′, and concluded that potentiation of methicillin activity by totarol is by interference with the synthesis of this MRSA-specific PBP. Obviously this would not be the mode of action in non-MRSA effluxing strains. The presence of other efflux pumps for which totarol may be a substrate is one possible reason for the difference in activity.

The mode of antibacterial action of totarol is not known. Several possibilities have been suggested, including inhibition of bacterial respiratory transport (8), but others have found that totarol inhibits growth of anaerobic bacteria (28). Another possibility is disruption of membrane phospholipids, leading to loss of membrane integrity (18). Increased leakage of protons through the mitochondrial membrane was observed by one group, although at a higher totarol concentration than required for antibacterial activity (5). Most recently, inhibition of bacterial cytokinesis by targeting the FtsZ protein, which forms the Z ring, was reported (9). In some instances it has been found that the presence of a modulator can have a negative effect on antibiotic activity (29, 30). It is possible that the modulator may interact with the antibiotic substrate, perhaps leading to reduced bioavailability of the drug (31).

Totarol reduces NorA-mediated EtBr efflux, but the mechanism(s) of this effect is not known. Whether totarol acts directly, i.e., by binding to the pump, or indirectly, perhaps by binding the pump substrate or affecting the assembly, conformation, or even the translation of the pump, remains to be determined.

There is a potentially useful separation between the antibacterial activity of totarol and its cytotoxicity. Clarkson et al. (3) reported antiplasmodial activity for totarol against a chloroquine-resistant strain of Plasmodium falciparum at an IC50 of 4.29 μM, which was 40-fold less than its cytotoxic activity against CHO cells. A recent report suggested differential inhibitory effects on mammalian and bacterial cell proliferation, with only weak inhibition of HeLa cell proliferation in the presence of totarol (9). The activity of totarol as an antibacterial, modulator and EPI seen in this study, together with results from others, suggests that totarol would be a good lead candidate for further development in the search for effective drugs against resistant S. aureus.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stiefel International R&D Ltd. for the award of a studentship and postdoctoral funding to E. C. J. Smith and The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council for a multiproject equipment grant (no. GR/R47646/01).

We thank Bedgebury Pinetum, Goudhurst, Kent, United Kingdom, for the supply of conifer material.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Augustin, J., R. Rosenstein, B. Weiland, U. Schneider, N. Schell, G. Engelke, K. Entian, and F. Götz. 1992. Genetic analysis of epidermin biosynthetic genes and epidermin-negative mutants of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Eur. J. Biochem. 204:1149-1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball, A. R., G. Casadei, S. Samosom, J. B. Bremner, F. M. Ausubel, T. I. Moy, and K. Lewis. 2006. Conjugating berberine to a multidrug efflux pump inhibitor creates an effective antimicrobial. ACS Chem. Biol. 1:594-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarkson, C., C. C. Musonda, K. Chibale, W. E. Campbell, and P. Smith. 2003. Synthesis of totarol amino alcohol derivatives and their antiplasmodial activity and cytotoxicity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 11:4417-4422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eliopoulos, G. M., and R. C. Moellering, Jr. 1991. Antimicrobial combinations, p. 432-492. In V. Lorian (ed.), Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, MD.

- 5.Evans, G. B., R. H. Furneaux, G. J. Gainsford, and M. P. Murphy. 2000. The synthesis and antibacterial activity of totarol derivatives. 3. Modification of ring-B. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 8:1663-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster, T. J. 1998. Molecular genetic analysis of staphylococcal virulence. Methods Microbiol. 27:433-454. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbons, S., and E. E. Udo. 2000. The effect of reserpine, a modulator of multidrug efflux pumps, on the in vitro activity of tetracycline against clinical isolates of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) possessing the tet(K) determinant. Phytother. Res. 14:139-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haraguchi, H., H. Ishikawa, and I. Kubo. 1996. Mode of antibacterial action of totarol, a diterpene from Podocarpus nagi. Planta Med. 62:122-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaiswal, R., T. K. Beuria, R. Mohan, S. K. Mahajan, and D. Panda. 2007. Totarol inhibits bacterial cytokinesis by perturbing the assembly dynamics of FtsZ. Biochemistry 46:4211-4220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaatz, G. W., S. I. Barriere, D. R. Schaberg, and R. Fekety. 1987. The emergence of resistance to ciprofloxacin during therapy of experimental methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 20:753-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaatz, G. W., S. M. Seo, and C. A. Ruble. 1993. Efflux-mediated fluoroquinolone resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1086-1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaatz, G. W., S. M. Seo, L. O'Brien, M. Wahiduzzaman, and T. J. Foster. 2000. Evidence for the existence of a multidrug efflux transporter distinct from NorA in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1404-1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaatz, G. W. 2005. Bacterial efflux pump inhibition: a potential means to recover clinically relevant activity of substrate antimicrobial agents. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 6:191-198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubo, I., H. Muroi, and M. Himejima. 1992. Antibacterial activity of totarol and its potentiation. J. Nat. Prod. 55:1436-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lomovskaya, O., and K. A. Bostian. 2006. Practical applications and feasibility of efflux pump inhibitors in the clinic—a vision for applied use. Biochem. Pharmacol. 71:910-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markham, P. N., and A. A. Neyfakh. 1996. Inhibition of the multidrug transporter NorA prevents emergence of norfloxacin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2673-2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markham, P. N., E. Westhaus, K. Klyachko, M. E. Johnson, and A. A. Neyfakh. 1999. Multiple novel inhibitors of the NorA multidrug transporter of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2404-2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Micol, V., C. R. Mateo, S. Shapiro, F. J. Aranda, and J. Villalain. 2001. Effects of (+)-totarol, a diterpenoid antibacterial agent, on phospholipid model membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1511:281-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mossa, J. S., F. S. El-Feraly, and I. Muhammad. 2004. Antimycobacterial constitutents from Juniperus procera, Ferula communis and Plumbago zeylanica and their in vitro synergistic activity with isonicotinic acid hydrazide. Phytother. Res. 18:934-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muroi, H., and I. Kubo. 1996. Antibacterial activity of anacardic acid and totoral, alone and in combination with methicillin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 80:387-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neyfakh, A. A., C. M. Borsch, and G. W. Kaatz. 1993. Fluoroquinolone resistance protein NorA of Staphylococcus aureus is a multidrug efflux transporter. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:128-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicolson, K., G. Evans, and P. W. O'Toole. 1999. Potentiation of methicillin activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by diterpenes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 179:233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishida, T., I. Wahlberg, and C. R. Enzell. 1977. Carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of some aromatic diterpenoids. Org. Mag. Reson. 9:203.209. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piddock, L. J. V. 2006. Multidrug-resistance efflux pumps—not just for resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:629-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Price, C. T. D., G. W. Kaatz, and J. E. Gustafson. 2002. The multidrug efflux pump NorA is not required for salicylate-induced reduction in drug accumulation by Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 20:206-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reynolds, E., J. I. Ross, and J. H. Cove. 2003. Msr(A) and related macrolide/streptogramin resistance determinants: incomplete transporters? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 22:228-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richardson, J. F., and S. Reith. 1993. Characterisation of a strain of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (EMRSA-15) by conventional and molecular methods. J. Hosp. Infect. 25:45-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shapiro, S., and B. Guggenheim. 1998. Inhibition of oral bacteria by phenolic compounds. 1. QSAR analysis using molecular connectivity. Quant. Struct. Activity Relationships 17:327-337. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith, E., E. Williamson, M. Zloh, and S. Gibbons. 2005. Isopimaric acid from Pinus nigra shows activity against multidrug-resistant and EMRSA strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Phytother. Res. 19:538-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tegos, G., F. R. Stermitz, O. Lomovskaya, and K. Lewis. 2002. Multidrug pump inhibitors uncover remarkable activity of plant antimicrobials. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3133-3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zloh, M., G. W. Kaatz, and S. Gibbons. 2004. Inhibitors of multidrug resistance (MDR) have affinity for MDR substrates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 14:881-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]