Abstract

Paradoxical growth was noted in RPMI 1640 and antibiotic medium 3 in the case of 14 and 1 of 15 Candida tropicalis strains, respectively, at a caspofungin concentration of 12.5 μg/ml using minimum fungicidal concentration tests. Time-kill assays showed that against isolates killed at lower concentrations, caspofungin at a concentration of 12.5 μg/ml was only fungistatic.

The growing body of data shows that some Candida strains, which are inhibited by a low concentration of echinocandin antifungals, exhibit growth in the presence of high concentrations of the drugs (2, 9, 10). The frequencies of this paradoxical growth (PG) were found to vary (observed for 10 to 90% of strains) among the most frequently isolated Candida species (2, 7, 9). The only species found to grow in the presence of a high concentration of all three marketed echinocandins, i.e., caspofungin (CAS), micafungin (MICA), and anidulafungin, was C. tropicalis (2).

Our aim was to examine the occurrence of PG in clinical C. tropicalis isolates in vitro by means of MIC and minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC) tests as well as by determining the killing dynamics in time-kill experiments.

(This work was presented in part at the 8th European Congress of Chemotherapy and Infection, Budapest, Hungary, 2006 [poster no. 212].)

Fifteen C. tropicalis clinical isolates and the C. tropicalis strain ATCC 750 were used. The CAS (Merck) MICs and MFCs were determined according to the CLSI (formerly NCCLS) method with RPMI 1640 medium (6) and antibiotic medium 3 (AM3; Fluka), as recommended previously (1). In MFC tests, the starting inoculum was increased 100-fold (to 105 CFU/ml) (5). The CAS concentration range was 0.024 to 12.5 μg/ml. CAS MICs were read after 24 h, using the partial inhibition criterion (5). After 24 and 48 h, the entire contents of each well containing drug concentrations above the MIC was plated onto Sabouraud dextrose agar (5).

Time-kill studies were performed following the method described previously (4). CAS concentrations ranged from 1 to 512 times the MIC (0.024 to 12.5 μg/ml). Samples were removed at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h and plated onto Sabouraud dextrose agar. Plates were incubated at 35°C for 48 h, in both the MFC and the time-kill tests, and fungicidal activity was defined as a 99.9% reduction in viable CFU/ml compared to that of the starting inoculum (4, 5).

In another experiment, 1 μg/ml of amphotericin B (AMB) (Sigma), fluconazole (FLC) (Pfizer), or flucytosine (5FC) (Sigma) was added to the test tubes containing 12.5 μg/ml of CAS. All assays were repeated at least twice.

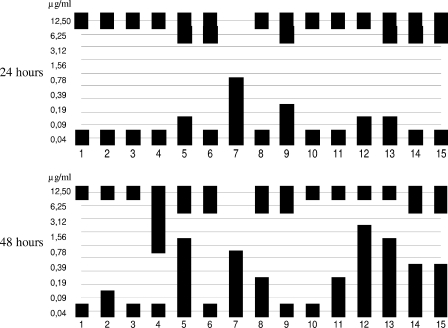

In both the RPMI 1640 medium and AM3, MICs were 0.024 μg/ml for all strains, regardless of the starting inoculum. In RPMI 1640 medium, PG was detected in two cases (isolates 4 and 15) at 12.5 μg/ml CAS, using the standard inoculum. In the case of the elevated starting inoculum, partial growth was detected in all wells. In MFC tests, all isolates except number 7 grew at 12.5 μg/ml (Fig. 1). Six of fifteen and 7 out of 15 isolates also grew at 6.25 μg/ml after 24 and 48 h of incubation, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Growth distribution of the C. tropicalis clinical isolates (no. 1 to 15) at different concentrations of CAS (0.4 to 12.50 μg/ml) in the MFC tests after 24 and 48 h in RPMI 1640 medium.

In AM3, isolate number 6 showed PG after the high-concentration inoculum was used but not with the standard starting inoculum. In the MFC test, this strain also grew at 6.25 and 12.5 μg/ml. Fifteen strains were killed by concentrations ≤0.09 μg/ml CAS (≤4 times the MIC) after 24 h.

The strains tested in the time-kill experiments together with their AMB, FLC, and 5FC MICs are listed in Table 1; representative kill curves with RPMI 1640 medium are shown in Fig. 2.

TABLE 1.

MICs and PG patterns of strains used in this studya

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)c

|

PG at 6.25 and 12.5 μg/ml after d:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMB | FLC | 5FC | 24 h | 48 h | |

| 4 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 12.5 | Both |

| 5 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.12 | Both | Both |

| 6b | 2 | 0.25 | 0.12 | Both | Both |

| 7 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.12 | None | None |

| 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 12.5 | 12.5 |

| 13 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 12.5 | 12.5 |

| 15 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.12 | Both | Both |

| ATCC 750 | 1 | 1 | 0.12 | Both | Both |

Strains used in the time-kill experiments are shown with their MICs for AMB, FLC, and 5FC and their PG patterns in MFC tests after 24 and 48 h in RPMI 1640 medium.

This isolate also showed PG in AM3.

MICs were determined according to the CLSI method (6).

Both, PG was observed at both concentrations. None, PG was observed at neither concentration.

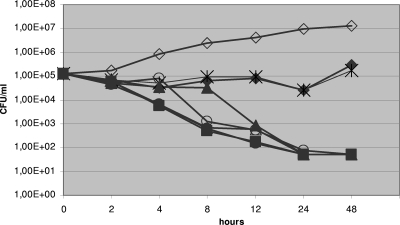

FIG. 2.

Representative time-kill plots of C. tropicalis isolate number 15 (MIC, 0.024 μg/ml) following exposure to CAS in RPMI 1640 medium. Filled diamonds, 512 times the MIC; asterisks, 256 times the MIC; filled triangles, 128 times the MIC; open circles, 32 times the MIC; filled squares, 8 times the MIC; filled circles, 2 times the MIC; open triangles, 1 times the MIC; open diamonds, drug-free control. Each datum point represents the mean of two independent experiments.

Time-kill curves confirmed the PG of seven of the clinical isolates found to grow paradoxically by using MFC determinations in both media. Ranges of CFU changes varied between −lg0.36 to −lg1.3 and −lg1.51 to +lg0.63 CFU/ml after 24 and 48 h, respectively. Generally, CAS proved to be fungicidal at lower (≤3.12 μg/ml) concentrations, but at high concentrations (6.25 to 12.5 μg/ml), only fungistatic activity was observed (Fig. 2). When we retested the strains growing at 12.5 μg/ml, we obtained essentially the same CAS kill curves.

The killing patterns obtained using the MFC and the time-kill methods (except for isolate 4 and the ATCC 750 strain in RPMI 1640 medium) were identical for the strains tested. C. tropicalis ATCC 750 grew at all CAS concentrations tested in the MFC tests, after both 24 and 48 h. In the time-kill test, this strain grew only at 512 times the MIC (12.5 μg/ml), but yeasts were killed at 1 to 256 times the MIC (0.19 to 6.25 μg/ml) for CAS concentrations after 24 h. A similar discrepancy, but to a lesser extent, was found for isolate number 4.

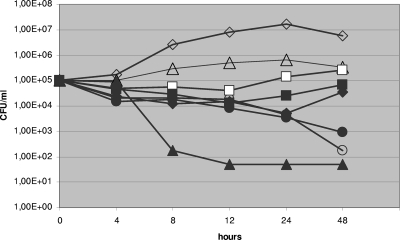

In the time-kill assay, the presence of FLC, but not of AMB or 5FC, at 1 μg/ml, regardless of the medium used, eliminated PG even after 24 h, for all clinical isolates (Fig. 3). In contrast, in the case of C. tropicalis ATCC 750, the combination of CAS with AMB, but not with FLC or 5FC, eliminated PG.

FIG. 3.

Time-kill plots of C. tropicalis isolate number 4 following exposure to CAS alone and CAS combined with other antifungals in RPMI 1640 medium. Open diamonds, drug-free control; filled diamonds, CAS (12.5 μg/ml) alone; open triangles, FLC (1 μg/ml) alone; filled triangles, CAS (12.5 μg/ml) plus FLC (1 μg/ml); open circles, AMB (1 μg/ml) alone; filled circles, CAS (12.5 μg/ml) plus AMB (1 μg/ml); open squares, 5FC (1 μg/ml) alone; filled squares, CAS (12.5 μg/ml) plus 5FC (1 μg/ml). Each datum point represents the mean of two separate experiments with similar results.

C. tropicalis is a species that shows PG equally in the presence of CAS, MICA, and anidulafungin (2). Moreover, Pappas et al. observed more treatment failures with daily doses of 150 mg MICA but not with daily doses of 100 mg MICA or 70 mg CAS (8), in cases of patients infected with several Candida species including C. tropicalis. They suggested that PG may contribute to this phenomenon. Similar in vivo effects were observed for infections by Aspergillus fumigatus and C. albicans (3, 11).

In our work, visible PG in RPMI 1640 medium was noted in the case of 2/15 (13%) and 14/15 (93%) isolates in the MIC and MFC tests, respectively. Similar to the results reported by Pai et al. (7), we found that the use of AM3 almost totally eliminated this phenomenon; a single isolate showed PG in the MFC tests but none in the MIC tests.

Killing curves obtained with high-concentration CAS clearly indicated that viable C. tropicalis cells were present at all times during the time-kill experiment; at very high concentrations, CAS practically became fungistatic rather than fungicidal. The time-kill method was superior to the MFC test for the ATCC strain.

In conclusion, PG could be reliably predicted by the time-kill and MFC tests but not by the MIC test. This may have future implications, because based on these and earlier data (2, 3, 11), the clinical relevance of PG cannot be excluded, suggesting that high doses of echinocandins may lead to treatment failure in certain clinical situations (8).

Acknowledgments

We thank Cecília Miszti and Erzsébet Falusi for help with isolation and identification of yeasts.

Caspofungin and fluconazole in pure powder form were kindly provided by Merck Research Laboratories and Pfizer Inc., respectively.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartizal, C., and F. C. Odds. 2003. Influences of methodological variables on susceptibility testing of caspofungin against Candida species and Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2100-2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chamilos, G., R. E. Lewis, N. Albert, and D. P. Kontoyiannis. 2007. Paradoxical effect of echinocandins across Candida species in vitro: evidence for echinocandin-specific and Candida species-related differences. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2257-2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clemons, K. V., M. Espiritu, R. Parmar, and D. A. Stevens. 2006. Assessment of paradoxical effect of caspofungin in therapy of candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1293-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klepser, M. E., E. J. Ernst, R. E. Lewis, M. E. Ernst, and M. A. Pfaller. 1998. Influence of test conditions on antifungal time-kill curve results for standardized methods. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1207-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majoros, L., G. Kardos, B. Szabó, and M. Sipiczki. 2005. Caspofungin susceptibility testing of Candida inconspicua: correlation of different methods with the minimal fungicide concentration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3486-3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2002. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard M27-A2. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 7.Pai, M. P., A. L. Jones, and C. K. Mullen. 2007. Micafungin activity against Candida bloodstream isolates: effect of growth medium and susceptibility testing method. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 58:129-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pappas, P. G., C. M. F. Rotstein, R. F. Betts, M. Nucci, D. Talwar, J. J. De Waele, J. A. Vazquez, B. F. Dupont, D. L. Horn, L. Ostrosky-Zeichner, A. C. Reboli, B. Suh, R. Digumarti, C. Wu, L. L. Kovanda, L. J. Arnold, and D. N. Buell. 2007. Micafungin versus caspofungin for treatment of candidemia and other forms of invasive candidiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45:883-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens, D. A., M. Espiritu, and R. Parmar. 2004. Paradoxical effect of caspofungin: reduced activity against Candida albicans at high drug concentrations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3407-3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens, D. A., M. Ichinomiya, Y. Koshi, and H. Horiuchi. 2006. Escape of Candida from caspofungin inhibition at concentrations above the MIC (paradoxical effect) accomplished by increased cell wall chitin; evidence for β-1,6-glucan synthesis inhibition by caspofungin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3160-3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiederhold, N. P., D. P. Kontoyiannis, J. Chi, R. A. Prince, V. H. Tam, and R. E. Lewis. 2004. Pharmacodynamics of caspofungin in a murine model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: evidence of concentration-dependent activity. J. Infect. Dis. 190:1464-1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]