Abstract

The horizontal transfer of genes by mobile genetic elements such as plasmids and phages can accelerate genome diversification of Vibrio spp., affecting their physiology, pathogenicity, and ecological character. In this study, sequence analysis of three plasmids from Vibrio spp. previously isolated from salt marsh sediment revealed the remarkable diversity of these elements. Plasmids p0908 (81.4 kb), p23023 (52.5 kb), and p09022 (31.0 kb) had a predicted 99, 64, and 32 protein-coding sequences and G+C contents of 49.2%, 44.7%, and 42.4%, respectively. A phylogenetic tree based on concatenation of the host 16S rRNA and rpoA nucleotide sequences indicated p23023 and p09022 were isolated from strains most closely related to V. mediterranei and V. campbellii, respectively, while the host of p0908 forms a clade with V. fluvialis and V. furnissii. Many predicted proteins had amino acid identities to proteins of previously characterized phages and plasmids (24 to 94%). Predicted proteins with similarity to chromosomally encoded proteins included RecA, a nucleoid-associated protein (NdpA), a type IV helicase (UvrD), and multiple hypothetical proteins. Plasmid p0908 had striking similarity to enterobacteria phage P1, sharing genetic organization and amino acid identity for 23 predicted proteins. This study provides evidence of genetic exchange between Vibrio plasmids, phages, and chromosomes among diverse Vibrio spp.

The Vibrionaceae are gram-negative Gammaproteobacteria that occur in temperate to tropical, coastal, and estuarine marine systems (62). Vibrio spp. occupy a diverse range of ecological niches, including sediments, the water column, and in association with organisms either as symbionts (48) or pathogens (26, 37). Phages contribute to Vibrio evolution and ecology by regulating host abundance (29) and transferring virulence genes, such as the cholera toxin encoded by ctxAB of the CTXφ phage of V. cholerae (64). Plasmids such as pJM1 of V. anguillarum (20) have also been shown to play a role in Vibrio pathogenicity. In recent years, sequencing has revealed the vast diversity of phage genomes (10) and their globally significant contributions to horizontal gene transfer within marine environments (35). In contrast to the demonstrated genetic diversity of vibriophages (16, 66), much less is known of Vibrio plasmid diversity and the role of plasmids in gene transfer. A few studies have reported the occurrence of plasmids among Vibrio populations (19-21, 44, 63), and several have reported complete sequences of Vibrio plasmids associated with pathogenic vibrios; however, the distribution and sequence diversity of Vibrio plasmids has not been studied as extensively as vibriophages.

As of September 2007, there are 16 plasmid and 20 phage sequences in GenBank that were isolated from vibrios (12-14, 20, 21, 23, 25, 27, 28, 31, 38, 41, 43, 45-48, 51, 67). These sequences are biased toward small elements (i.e., nine plasmids of <8 kb and 10 phages of <9 kb) and are primarily associated with well-characterized human and fish pathogens. Among these are plasmids isolated from V. anguillarum (20, 67), V. cholerae (46, 47), V. vulnificus (14), V. parahaemolyticus (41), and V. salmonicida. The lack of plasmid sequence data, particularly of plasmids from Vibrio hosts isolated from coastal water and sediment, limits our understanding of Vibrio plasmid evolution and diversity.

In the present study we provide a comparative assessment of plasmids with diverse sizes and gene contents isolated from vibrios. Similarities of replication initiation and hypothetical proteins revealed relatedness of plasmids from vibrios occupying diverse niches. In addition, these elements contained numerous phage-like proteins, including proteins with considerable similarity and conserved gene order to enterobacteria phage P1. To our knowledge, this is the first report of P1-like phage sequences isolated from a marine bacterium. A previous study identified two P1-like genes as part of a marine viral metagenome (10); however, no additional P1 genes or nearly complete P1 genomes have been characterized from the marine environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and plasmid isolation.

Vibrio sp. strains 0908, 23023, and 09022 were isolated from salt marsh sediment of Charleston, SC, in December 1998 (17). DNA for sequencing was obtained by purification of supercoiled plasmid DNA by cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation as previously described (52).

Plasmid sequencing and sequence analysis.

Plasmids were sequenced using whole-genome shotgun sequencing and finishing methods (26). Initial open reading frame designations and annotation of select open reading frames was done using an automated annotation system (26). Protein-coding sequences (CDSs) were confirmed by independent analysis using GeneMark software (7). Putative similarity to known proteins was determined by amino acid sequence comparison and identification of common motif and domain structure using a combination of PSI-BLAST (3) from the National Center for Biotechnology Information, SMART (50), COG (57), and Pfam (6) Web-based software. PSI-BLAST analysis was performed with the default threshold E-value of 0.005 and a maximum threshold of 1.0 over one to two iterations. ClustalW was used to generate all alignments (61).

Phylogenetic analyses and sequence alignments.

Host strains were identified by a concatenated phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA and rpoA nucleotide sequences as previously described (18). The neighbor-joining tree was generated using MEGA with the Jukes-Cantor (30) distance estimation model with 1,000 replications for the nucleotide concatenation or the Poisson correction for the amino acid RecA tree (42). Percent identities of the nucleotide sequences to the most related organism were determined using BLASTN (3) and BLAST2 (58) sequences. Sequencing was performed by the University of Nevada, Reno, Genomics Center and the Core Genomics Facility at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Identification of phage-like proteins.

Prophage Finder (9) was used with BLAST analysis (3, 49) of a phage sequence database to identify prophages and proteins with similarities to phage-associated proteins for all sequenced Vibrio plasmids available in GenBank as of July 2007. An E value of 0.001 with 10 hits/prophage and a hit spacing of 3,500 were used as parameters for all plasmids examined.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The plasmid sequences have been submitted to the GenBank database under accession numbers CP000755 to CP000757. All additional sequences have been submitted to the GenBank database under accession numbers EU022567 to EU022572.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Host phylogeny and plasmid features.

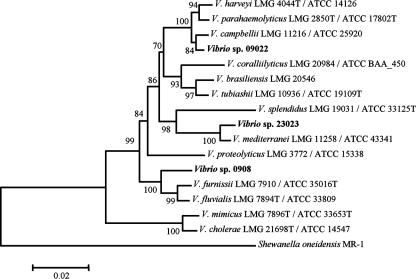

In this study we examined the sequence diversity of plasmids previously isolated from three Vibrio hosts (17). A concatenation of 16S rRNA sequences and rpoA nucleotide sequences was used for greater resolution of related Vibrio spp. (60). The 16S rRNA and rpoA nucleotide sequences of Vibrio sp. strains 0908, 23023, and 09022 were 98 and 97%, 98 and 99%, and 99 and 98% identical to those of V. fluvialis, V. mediterranei, and V. campbellii, respectively. Phylogenetic analysis of concatenated 16S rRNA and rpoA nucleotide sequences of Vibrio sp. strains 23023 and 09022 indicated they were most related to V. mediterranei and V. campbellii, respectively (Fig. 1). Vibrio sp. strain 0908 forms a clade with the closely related V. furnissii and V. fluvialis group (11). To date, the only report of mobile genetic elements (MGEs) associated with any of these Vibrio species is an SXT-like element of V. fluvialis with similarity to the multiple antibiotic resistance element SXT previously characterized from V. cholerae (2). This previous study indicated there may be transfer of MGEs among well-characterized pathogens such as V. cholerae and emerging marine pathogens such as V. fluvialis (11, 34, 55).

FIG. 1.

A concatenation of 16S rRNA and rpoA nucleotide sequences of the plasmid hosts, Vibrio sp. strains 0908, 23023, and 09022, was used to determine relatedness of the hosts to other Vibrio spp. as examined in a previous study (60). The neighbor-joining method with the Jukes-Cantor model of distance estimation (30) was used to generate the tree with a concatenation of 16S rRNA (1,452 nucleotides) and rpoA (772 nucleotides) sequences. Bootstrap values represent 1,000 replications, and only those with values of ≥50 are shown.

The nucleotide sequences of the Vibrio plasmids p0908, p23023, and p09022 were 81,413 bp, 52,527 bp, and 31,036 bp in length with overall G+C contents of 49.2%, 44.7%, and 42.4%, respectively (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). With the exception of p0908, the G+C contents of the plasmids were within the range of percentages reported for Vibrio genomes (38 to 47%) (14, 26, 37, 48). The plasmids p0908, p23023, and p09022 encoded 99, 64, and 32 predicted CDSs, respectively (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The predicted proteins were assigned primarily to the following functional categories: replication, stable maintenance, partitioning, and recombination. Additional predicted proteins identified on one or more of the plasmids may be involved in mobilization, restriction modification, or transcriptional regulation (see Tables S1 to S3 in the supplemental material). The only genes common to at least two of the three plasmids were the putative replication initiation and partitioning proteins. The predicted replication initiation protein of p09022 encoded by CDS19 was 94% identical to the replication initiation protein of plasmid pKA1 from V. cholerae and 39% identical to the replication initiation protein of p0908. The predicted protein of p23023 most closely resembling a replication initiation protein was that encoded by CDS11, although it had little similarity to predicted replication proteins from characterized Vibrio or other marine plasmids.

Plasmids encoding putative proteins for self-mobilization, such as p23023, may be frequently transferred between Vibrio hosts. In contrast, plasmids such as p0908 and p09022, without identifiable proteins aiding transfer, may rely on transmission by phages or other mechanisms. V. cholerae was recently shown to naturally transform 22-kb segments of genomic DNA, suggesting mechanisms of DNA uptake may facilitate incorporation of large DNA molecules (39). Additional studies would be required to determine mechanisms promoting transmission of the plasmids described in this study.

The significant amino acid identity (≥83%) (see Table S3 in the supplemental material) and conserved gene order of six predicted proteins encoded by p09022 compared to those of V. cholerae plasmid pKA1 suggest Vibrio plasmids from diverse hosts may undergo frequent gene exchange. Alternately, this may indicate a common rep family exists among diverse Vibrio hosts, as the conserved genes included three proteins likely to be involved in replication initiation and partitioning. The remaining three predicted proteins were hypothetical (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). An additional protein encoded on p09022 had 94% amino acid identity to a hypothetical protein of plasmid p0471 from an uncharacterized marine bacterial host (1).

Identification of P1-like proteins on Vibrio plasmid p0908.

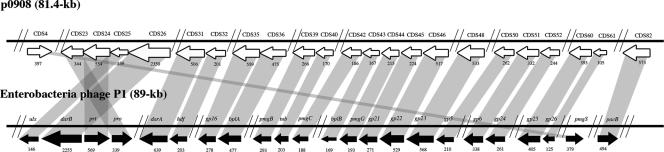

The phage P1 of enterobacteria has been isolated from enteric bacteria (40) and has been shown to infect diverse bacteria under certain laboratory conditions (40). P1-like proteins and evidence of intact P1 phage have been identified in freshwater (5); however, to date none has been identified in marine systems. We identified 23 CDSs on p0908 with similarity to P1-encoded proteins and 20 additional proteins with similarity to other phage-encoded proteins. The remaining 16 predicted proteins were similar to chromosomally or plasmid-encoded proteins, and 41 had no similarity to previously characterized proteins. The 23 CDSs of p0908 encoding P1-like proteins also occur in the same genomic arrangement as reported for the P1 genome, with a few differences, possibly due to rearrangements (Fig. 2) (36). The majority of these P1-like proteins (20 of 23) exhibited the same direction of transcription (Fig. 2). The G+C contents of CDSs encoding the P1-like proteins (47 to 54%) were more similar to the overall G+C contents of p0908 (49.2%), P1 (49%) (36), and the Escherichia coli host (50%) (8) than Vibrio chromosomes (39 to 47%) (14, 26, 37, 48).

FIG. 2.

Genetic organization and amino acid conservation of predicted CDSs of p0908 compared to CDSs of enterobacteria phage P1. Shading indicates regions with amino acid similarity, while the protein lengths (number of amino acids) are designated under each arrow and approximated by the arrow size. The orientation of each arrow indicates the direction of transcription. Vertical lines indicate the presence of additional genes that are not shown.

Of the proteins encoded on p0908 with similarity to P1 proteins, there were 16 structural proteins, 6 antirestriction and head-processing proteins, and 1 involved in DNA packaging (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The structural proteins included those described as base plate and tail tube (gp16, BplA, PmgB, Tub, PmgC, BplB, PmgG, gp5, gp6, gp24, gp25, and gp26), sheath (gp21 and gp22), and head (PmgS and gp23) components. The P1-like proteins involved in antirestriction and head processing include DarA and DarB (36). Antirestriction proteins such as DarA and DarB prevent damage of phage DNA by host restriction enzymes (36). Identification of a protein encoded on p0908 with similarity to DarA strongly suggests p0908 may have acquired the P1-like genes from a P1 phage, since DarA was shown to be unique to P1 (36). An additional indication of gene exchange between P1 and p0908 is the presence of a CDS encoding a protein similar to DarB. The predicted protein of CDS26 (2,350 amino acids) is comparable to DarB, which is the largest P1-encoded protein (2,255 amino acids) (36) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Most of the P1-like genes of p0908 encode proteins for phage structures, such as tub, encoding a tail protein, and pro, involved in cleavage of head proteins during phage formation (36). P1 genes involved in prophage addiction, phd and doc (26), were noticeably absent from p0908. Although there were many phage structural proteins encoded on p0908, it is unlikely this is a functional phage, as critical proteins for packaging and dispersal were absent. These included lydA and lydB, encoding a holin and antiholin for host cell lysis (36). Of the proteins known to be required for functional packaging, PacB was identified; however, PacA was absent. The gene encoding PacA includes the pac cleavage site, which is cleaved by the pacase enzyme, which is composed of PacA and PacB proteins (36). A few proteins of KVP40, a T4-like phage, were similar to proteins of P1; however, this similarity was attributed to the relatedness of P1 and T4, both of which are in the viral family Myoviridae (38). Two of these shared proteins were identified on p0908, BplA and Tub (38); however, numerous additional proteins similar to those encoded in the P1 genome were identified on p0908 that were not present on KVP40. Also encoded on p0908 are integrase-like proteins, indicating the potential for integration of this element into a host chromosome (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Although Vibrio phages have been characterized with similarity to T4 (38), T7 (25), and P2 (43) phages, none have been characterized with similarity to P1 (36). The P1 integrase (cre) was identified in bacterial lysogens from a freshwater pond, indicating the presence of P1 in a freshwater environment (5). A viral metagenomic study produced two sequences with similarity to P1 PacA and PacB in estuarine waters of southern California (10). To our knowledge, no additional P1-like sequences or nearly complete P1 genomes have been identified from marine environments. The complete P1 sequence was finished after the viral metagenome was performed and, therefore, some of the P1 genes may have not been identified in the viral metagenome; however, a recent comparison of the P1 nucleotide sequence to the viral metagenome database primarily yielded hits to prophage from fish ponds (F. Rohwer, personal communication). This indicates that additional P1 genes were not present in the marine viral metagenome. The pathogenic nature of some Vibrio spp. and possible residence in the gut may have facilitated a Vibrio MGE to exchange genes with P1 of an enteric bacterium, resulting in an element such as p0908.

Identification of additional phage-like proteins on Vibrio plasmids.

The prevalence of P1-like proteins on p0908 led us to examine the occurrence of additional proteins typical of phage on all available Vibrio plasmids. Several non-P1 phage-like proteins were identified on the plasmids and in some cases had a conserved gene order as well as amino acid identity. BLAST searches (3, 49) of the plasmid genomes to a phage-only sequence database using Prophage Finder (9) identified plasmid CDSs encoding proteins similar to phage proteins. There were 43, 5, and 6 predicted proteins with similarity to phage proteins encoded by CDSs of p0908, p23023, and p09022, respectively (see Tables S1 to S3 in the supplemental material). Functions assigned to these proteins included replication, partitioning, transcriptional regulation, methylation, and recombination.

Of the 16 complete Vibrio plasmid sequences currently available (pES100, pYJ106, pJM1, pEIB1, pPS41, pSA19, pSIO1, pTC68, pVS43/pVS54, pES213, pTLC, pC4602-1, pC4602-2, pMP-1, and pR99), we detected the highest frequency of phage proteins on plasmids described in this study. These proteins encoded by CDSs of p0908, p23023, and p09022 represented 43, 8, and 20% of the total predicted CDSs, respectively. In contrast, the other large plasmid sequences available, pES100 (45.8 kb) (48), pJM1 (65 kb) (20), pEIB1 (66.1 kb) (67), and pC4602-1 (56.6 kb), pC4602-2 (66.9 kb), pR99 (68.4 kb), and pYJ106 (48.5 kb) (14), isolated from V. fischeri, V. anguillarum, and V. vulnificus, respectively, encoded proteins with similarity to phage proteins that comprised between 4 and 14% of the predicted CDSs. Of the remaining nine plasmids, all less than 8 kb in size, pMP-1 (7.6 kb) had three proteins and pTLC (4.7 kb) (47), pVS43 (4.3 kb), and pVS54 (5.4 kb), isolated from a single strain of V. salmonicida, encoded a protein with similarity to a protein associated with a phage.

The additional non-P1 phage proteins identified by BLAST analysis included recombinases, transcriptional regulators, transposases, and hypothetical proteins. Specifically, CDSs 53 to 56 of p0908 encoded proteins with 49 to 72% amino acid identity to CDSs 35 to 38 of phage VHML of V. harveyi (see Table S1 of the supplemental material) (43). The comparable predicted amino acid sizes, identical gene order, and high amino acid identities of these proteins suggest recombination between Vibrio phage and plasmid elements. Additional proteins identified on phages and other plasmids include hypothetical proteins with a helix-turn-helix (H-T-H) motif. The H-T-H motif is typical of transcriptional regulators and other proteins with DNA-binding activity (6, 56). The amino acid sequence of CDS27 of p0908 is one example with 30% amino acid identity to a hypothetical protein of Photorhabdus luminescens and 25% identity to the luxR of V. parahaemolyticus. CDSs 10 and 21 of p23023 were shown to have similar H-T-H motifs. Hypothetical proteins with H-T-H motifs were also reported for predicted proteins of vibriophages VP16C and VP16T (51). To our knowledge, the function and role of these putative transcriptional regulators for plasmid or phage stability have not been characterized.

Identification of conserved Vibrio chromosomal genes on Vibrio plasmids.

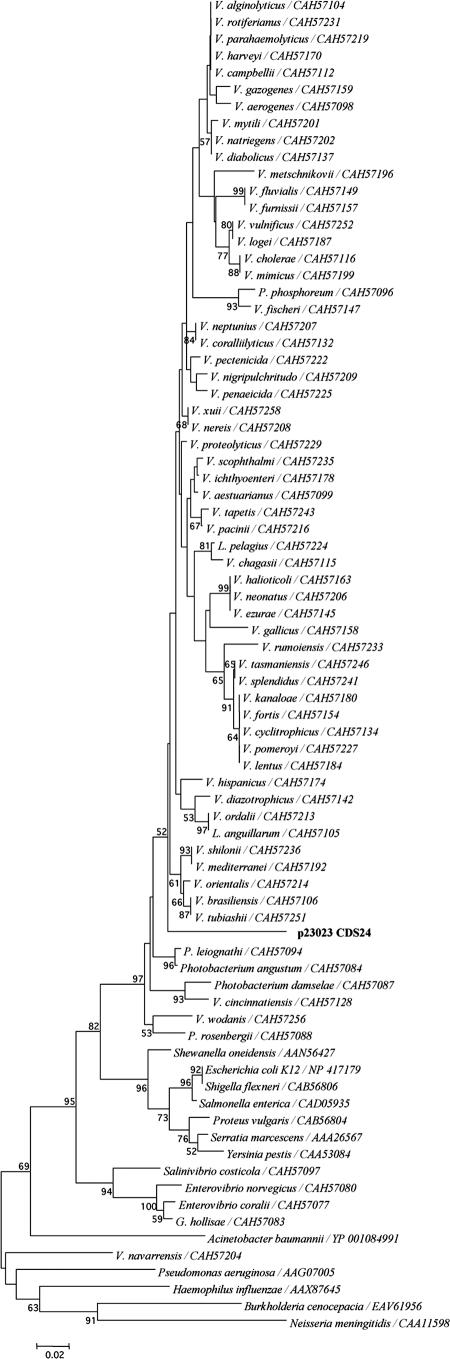

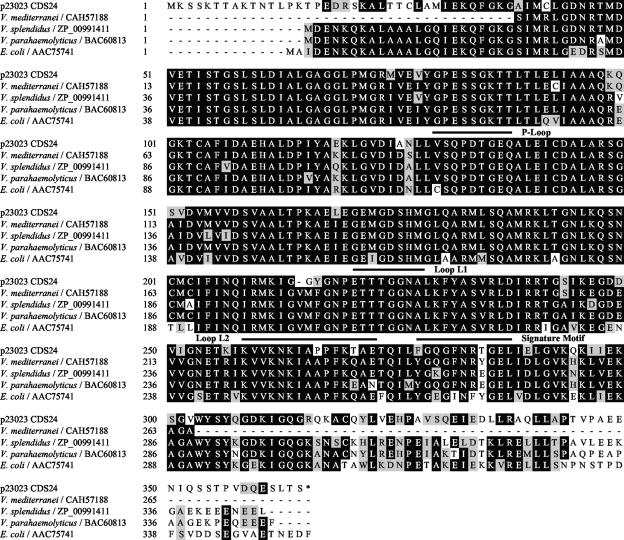

The three plasmids examined in this study encoded numerous CDSs with significant amino acid identity (33 to 81%) to chromosomally encoded genes of vibrios (see Tables S1 to S3 in the supplemental material). To our knowledge, these chromosomally encoded genes have exclusively been identified on chromosomes and not on MGEs. Among those with significant amino acid identity were RecA (81%), a nucleoid-associated protein, NdpA (65%), a type IV helicase, UvrD (65%), and a number of hypothetical proteins (50 to 80%). A RecA protein was previously reported on plasmid pNP40 (65 kb) from Lactococcus lactis (24); however, none has been identified to date on Vibrio plasmids. Also, the plasmid-encoded RecA described in this study has greater protein identity (81%) to Vibrio RecAs than the lactococcal plasmid RecA had to other characterized lactococcal RecAs (45% amino acid identity) (24). The RecA (CDS24) encoded on p23023 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) was more similar to RecA of other vibrios (81% amino acid identity) than to that of related Gammaproteobacteria, such as Photobacterium spp. (Fig. 3). This indicates the plasmid-encoded recA was likely from a Vibrio host. Sequence alignment of the predicted amino acid sequence of CDS24 to RecA sequences of V. mediterranei, V. splendidus, V. parahaemolyticus, and E. coli shows the extent of conservation of CDS24 to Vibrio RecAs (Fig. 4). The RecA signature motif characteristic of RecA proteins is present in all the aligned sequences (Fig. 4) (6). Also, the P-loop motif for ATP binding, which is characteristic of ATPase-like proteins, is present in CDS24 (4, 65) (Fig. 4). The DNA-binding loops L1 and L2, which are involved in double-stranded and single-stranded DNA binding, respectively (24, 54), are also present in CDS24. The DNA-binding loop L1 of CDS24 is identical to the same motif found in other RecAs (24, 54). In contrast, loop L2 contains a gap and two other amino acid changes that may alter the single-stranded DNA-binding activity of the protein encoded by CDS24. Based on sequence analysis of CDS24, the predicted protein likely has the recombinase (15) and proteolytic cleavage activities that have been characterized to date for other RecAs (22, 32). Future experimental studies are required to confirm these predicted functions of CDS24.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic comparison of the predicted amino acid sequence encoded by CDS24 of p23023 with RecA amino acid sequences representing most Vibrio spp. and additional members of the Vibrionaceae available in GenBank as of March 2007. Distantly related proteobacteria were included as outgroups. A neighbor-joining tree was constructed in MEGA (33) using the Poisson correction (42). Bootstrap values were generated over 1,000 replications and are indicated where the value was ≥50.

FIG. 4.

Sequence alignment of RecA amino acid sequences of CDS24 from p23023 with those sequences encoded on the genomes of V. splendidus, V. parahaemolyticus, and E. coli. The V. mediterranei RecA sequence was a partial sequence obtained from a multilocus sequence analysis of Vibrio spp. (60). The RecA signature motif (4), P-loop motif (Walker A motif) involved in ATP binding (6), loop L1 motif involved in binding of double-stranded DNA (24, 54), and the loop L2 motif for binding single-stranded DNA (24, 54) are all indicated.

RecA protein sequences have been shown for some bacterial species to provide greater resolution than phylogenetic analyses of an equal number of 16S rRNA sequences (22). Phylogenetic assessments of vibrios have previously demonstrated that recA nucleotide sequences can be used as an alternate phylogenetic marker to 16S rRNA (53, 59, 60). Several studies revealed considerable sequence variation (0 to 6%) of recA for certain Vibrio spp. (60), with as low as 94% recA nucleotide identity within a species. In contrast, Photobacterium spp., also within the Vibrionaceae, had less than 94% recA identity to the closest-related Vibrio recA. Overall, CDS24 is highly conserved compared to other RecA sequences; however, the N- and C-terminal regions have significantly diverged (Fig. 4). Sequence analyses of RecAs from diverse bacteria revealed the majority of the protein to be highly conserved while the N and C termini were significantly variable (22). The observed sequence divergence of the termini of the predicted protein sequence of CDS24 may have occurred by recombination with alleles having greater sequence divergence after the sequence was acquired by the plasmid. Alternately, selection pressure for a specialized role of the plasmid-encoded RecA for plasmid stability or uncharacterized functions may have led to the sequence divergence in the terminal regions.

This study is the first report of a recA encoded on a plasmid isolated from a Vibrio host. The potential for horizontal transmission of recA by Vibrio plasmids raises questions of whether recA provides reliable resolution for discriminating between related Vibrio spp. (59) or determining the extent of O-antigen gene exchange (53). Additional plasmid-encoded proteins with similarity to conserved chromosomal genes include the nucleoid-associated protein NdpA and a UvrD-like helicase. The plasmid-encoded NdpA reported here, CDS97 of p0908, had 65% amino acid identity (79% similarity) to NdpA of V. vulnificus (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Also, CDS48 of p23023 had 65% amino acid identity (79% similarity) to a UvrD-like helicase of Vibrio splendidus (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Recombination of host and plasmid-encoded uvrD-like genes may increase diversity of uvrD, potentially disrupting function of the host protein. To our knowledge this is the first description of an NdpA-like protein and a UvrD-like helicase encoded on a plasmid. These results indicate Vibrio plasmids may be involved in horizontal dissemination of conserved genes, such as recA and uvrD, both involved in host adaptive responses. Further investigation of the diversity encoded by Vibrio plasmids would be necessary to determine the extent that these elements transfer conserved genomic regions among diverse Vibrio spp.

In addition to high amino acid identity, several proteins had an identical gene order in the plasmid as that found in the Vibrio chromosomes. Specifically, CDSs 51 to 54 and 59 to 60 of p23023 encoded predicted proteins with amino acid identities and a conserved gene order to those reported for hypothetical proteins of V. fischeri (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Conclusion.

This study provides evidence for a role of Vibrio plasmids in gene exchange among diverse Vibrio spp., as evidenced by the gene content and unique genomic signatures of Vibrio plasmids relative to Vibrio chromosomes. Identification of P1-like proteins and other phage-like proteins on Vibrio plasmids supports the mosaicism of Vibrio MGEs and the potential for recombination between Vibrio plasmids and phages. The considerable diversity of recA among strains of certain Vibrio spp. may be facilitated by recombination of plasmid-encoded genes, such as the p23023 recA. Further studies into the genetic diversity of Vibrio plasmids as well as their potential host range are needed to better understand the evolution of MGEs and their role in diversification of Vibrio spp. This will serve as the basis for future molecular investigations into the role of plasmids for unique phenotypes promoting adaptation to fluctuating environmental conditions and the potential emergence of pathogens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mary Barnstead, Susan van Aken, Grace Pai, and M. Brook Craven for coordinating the library construction and sequencing of the plasmids. Also, we thank Ryan Mills and Heath Mills for the initial annotation work performed on the plasmids and Forest Rohwer for valuable suggestions for the sequence analysis and manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by Office of Naval Research grant N00014-02-1-0228 to P.A.S. and Office of Naval Research grant N00014-99-1-0860 to J.A.E. T. H. Hazen was supported by an NSF IGERT graduate fellowship.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 October 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agron, P. G., P. Sobecky, and G. L. Andersen. 2002. Establishment of uncharacterized plasmids in Escherichia coli by in vitro transposition. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 217:249-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed, A. M., S. Shinoda, and T. Shimamoto. 2005. A variant type of Vibrio cholerae SXT element in a multidrug-resistant strain of Vibrio fluvialis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 242:241-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schäffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bairoch, A. 1991. PROSITE: a dictionary of sites and patterns in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:2241-2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balding, C., S. A. Bromley, R. W. Pickup, and J. R. Saunders. 2005. Diversity of phage integrases in Enterobacteriaceae: development of markers for environmental analysis of temperate phages. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1558-1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bateman, A., L. Coin, R. Durbin, R. D. Finn, V. Hollich, S. Griffiths-Jones, A. Khanna, M. Marshall, S. Moxon, E. L. Sonnhammer, D. J. Studholme, C. Yeats, and S. R. Eddy. 2004. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:D138-D141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Besemer, J., and M. Borodovsky. 1999. Heuristic approach to deriving models for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:3911-3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett III, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bose, M., and R. D. Barber. 2006. Prophage Finder: a prophage loci prediction tool for prokaryotic genome sequences. In Silico Biol. 6:223-227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breitbart, M., P. Salamon, B. Andresen, J. M. Mahaffy, A. M. Segall, D. Mead, F. Azam, and F. Rohwer. 2002. Genomic analysis of uncultured marine viral communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:14250-14255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brenner, D. J., F. W. Hickman-Brenner, J. V. Lee, A. G. Steigerwalt, G. R. Fanning, D. G. Hollis, J. J. Farmer III, R. E. Weaver, S. W. Joseph, and R. J. Seidler. 1983. Vibrio furnissii (formerly aerogenic biogroup of Vibrio fluvialis), a new species isolated from human feces and the environment. J. Clin. Microbiol. 18:816-824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang, B., H. Miyamoto, H. Taniguchi, and S. Yoshida. 2002. Isolation and genetic characterization of a novel filamentous bacteriophage, a deleted form of phage f237, from a pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus O4:K68 strain. Microbiol. Immunol. 46:565-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang, B., H. Taniguchi, H. Miyamoto, and S. Yoshida. 1998. Filamentous bacteriophages of Vibrio parahaemolyticus as a possible clue to genetic transmission. J. Bacteriol. 180:5094-5101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, C. Y., K. M. Wu, Y. C. Chang, C. H. Chang, H. C. Tsai, T. L. Liao, Y. M. Liu, H. J. Chen, A. B. Shen, J. C. Li, T. L. Su, C. P. Shao, C. T. Lee, L. I. Hor, and S. F. Tsai. 2003. Comparative genome analysis of Vibrio vulnificus, a marine pathogen. Genome Res. 13:2577-2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark, A. J., and A. D. Margulies. 1965. Isolation and characterization of recombination-deficient mutants of Escherichia coli K12. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 53:451-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Comeau, A. M., A. M. Chan, and C. A. Suttle. 2006. Genetic richness of vibriophages isolated in a coastal environment. Environ. Microbiol. 8:1164-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook, M. A., A. M. Osborn, J. Bettandorff, and P. A. Sobecky. 2001. Endogenous isolation of replicon probes for assessing plasmid ecology of marine sediment microbial communities. Microbiology 147:2089-2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Criminger, J. D., T. H. Hazen, P. A. Sobecky, and C. R. Lovell. 2007. Nitrogen fixation by Vibrio parahaemolyticus and its implications for a new ecological niche. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:5959-5961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DePaola, A., J. L. Nordstrom, A. Dalsgaard, A. Forslund, J. Oliver, T. Bates, K. L. Bourdage, and P. A. Gulig. 2003. Analysis of Vibrio vulnificus from market oysters and septicemia cases for virulence markers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4006-4011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Lorenzo, M., M. Stork, M. E. Tolmasky, L. A. Actis, D. Farrell, T. J. Welch, L. M. Crosa, A. M. Wertheimer, Q. Chen, P. Salinas, L. Waldbeser, and J. H. Crosa. 2003. Complete sequence of virulence plasmid pJM1 from the marine fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum strain 775. J. Bacteriol. 185:5822-5830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunn, A. K., M. O. Martin, and E. V. Stabb. 2005. Characterization of pES213, a small mobilizable plasmid from Vibrio fischeri. Plasmid 54:114-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisen, J. A. 1995. The RecA protein as a model molecule for molecular systematic studies of bacteria: comparison of trees of RecAs and 16S rRNAs from the same species. J. Mol. Evol. 41:1105-1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faruque, S. M., I. B. Naser, K. Fujihara, P. Diraphat, N. Chowdhury, M. Kamruzzaman, F. Qadri, S. Yamasaki, A. N. Ghosh, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2005. Genomic sequence and receptor for the Vibrio cholerae phage KSF-1: evolutionary divergence among filamentous vibriophages mediating lateral gene transfer. J. Bacteriol. 187:4095-4103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garvey, P., A. Rince, C. Hill, and G. F. Fitzgerald. 1997. Identification of a RecA homolog (RecALP) on the conjugative lactococcal phage resistance plasmid pNP40: evidence of a role for chromosomally encoded RecAL in abortive infection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1244-1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardies, S. C., A. M. Comeau, P. Serwer, and C. A. Suttle. 2003. The complete sequence of marine bacteriophage VpV262 infecting Vibrio parahaemolyticus indicates that an ancestral component of a T7 viral supergroup is widespread in the marine environment. Virology 310:359-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleishmann, W. C. Nierman, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, H. O. Smith, R. R. Colwell, J. J. Mekalanos, J. C. enter, and C. M. Fraser. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honma, Y., M. Ikema, C. Toma, M. Ehara, and M. Iwanaga. 1997. Molecular analysis of a filamentous phage (fs1) of Vibrio cholerae O139. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1362:109-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ikema, M., and Y. Honma. 1998. A novel filamentous phage, fs-2, of Vibrio cholerae O139. Microbiology 144:1901-1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen, M. A., S. M. Faruque, J. J. Mekalanos, and B. R. Levin. 2006. Modeling the role of bacteriophage in the control of cholera outbreaks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:4652-4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jukes, T. H., and C. R. Cantor. 1969. Evolution of protein molecules. Academic Press, New York, NY.

- 31.Kapfhammer, D., J. Blass, S. Evers, and J. Reidl. 2002. Vibrio cholerae phage K139: complete genome sequence and comparative genomics of related phages. J. Bacteriol. 184:6592-6601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kowalczykowski, S. C., D. A. Dixon, A. K. Eggleston, S. D. Lauder, and W. M. Rehrauer. 1994. Biochemistry of homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 58:401-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, and M. Nei. 2004. MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 5:150-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, J. V., P. Shread, A. L. Furniss, and T. N. Bryant. 1981. Taxonomy and description of Vibrio fluvialis sp. nov. (synonym group F Vibrios, group EF6). J. Appl. Bacteriol. 50:73-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindell, D., M. B. Sullivan, Z. I. Johnson, A. C. Tolonen, F. Rohwer, and S. Chisholm. 2004. Transfer of photosynthesis genes to and from Prochlorococcus viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:11013-11018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lobocka, M. B., D. J. Rose, G. Plunkett, M. Rusin, A. Samojedny, H. Lehnherr, M. B. Yarmolinsky, and F. R. Blattner. 2004. Genome of bacteriophage P1. J. Bacteriol. 186:7032-7068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Makino, K., K. Oshima, K. Kurokawa, K. Yokoyama, T. Uda, K. Tagomori, Y. Iijima, M. Najima, M. Nakano, A. Yamashita, Y. Kubota, S. Kimura, T. Yasunaga, T. Honda, H. Shinagawa, M. Hattori, and T. Iida. 2003. Genome sequence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a pathogenic mechanism distinct from that of V. cholerae. Lancet 361:743-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller, E. S., J. F. Heidelberg, J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, A. S. Durkin, A. Ciecko, T. V. Feldblyum, O. White, I. T. Paulsen, W. C. Nierman, J. Lee, B. Szczypinski, and C. M. Fraser. 2003. Complete genome sequence of the broad-host-range vibriophage KVP40: comparative genomics of a T4-related bacteriophage. J. Bacteriol. 185:5220-5233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller, M. C., D. P. Keymer, A. Avelar, A. B. Boehm, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2007. Detection and transformation of genome segments that differ within a coastal population of Vibrio cholerae strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3695-7304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murooka, Y., and T. Harada. 1979. Expansion of the host range of coliphage P1 and gene transfer from enteric bacteria to other gram-negative bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 38:754-757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nasu, H., T. Iida, T. Sugahara, Y. Yamaichi, K. S. Park, K. Yokoyama, K. Makino, H. Shinagawa, and T. Honda. 2000. A filamentous phage associated with recent pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2156-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nei, M., and R. Chakraborty. 1976. Empirical relationship between the number of nucleotide substitutions and interspecific identity of amino acid sequences in some proteins. J. Mol. Evol. 7:313-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oakey, H. J., B. R. Cullen, and L. Owens. 2002. The complete nucleotide sequence of the Vibrio harveyi bacteriophage VHML. J. Appl. Microbiol. 93:1089-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pedersen, K., and J. L. Larsen. 1995. Evidence for the existence of distinct populations of Vibrio anguillarum serogroup O1 based on plasmid contents and ribotypes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2292-2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Powers, L. G., J. T. Mallonee, and P. A. Sobecky. 2000. Complete nucleotide sequence of a cryptic plasmid from the marine bacterium Vibrio splendidus and identification of open reading frames. Plasmid 43:99-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Purdy, A., F. Rohwer, R. Edwards, F. Azam, and D. H. Bartlett. 2005. A glimpse into the expanded genome content of Vibrio cholerae through identification of genes present in environmental strains. J. Bacteriol. 187:2992-3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubin, E. J., W. Lin, J. J. Mekalanos, and M. K. Waldor. 1998. Replication and integration of a Vibrio cholerae cryptic plasmid linked to the CTX prophage. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1247-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruby, E. G., M. Urbanowski, J. Campbell, A. Dunn, M. Faini, R. Gunsalus, P. Lostroh, C. Lupp, J. McCann, D. Millikan, A. Schaefer, E. Stabb, A. Stevens, K. Visick, C. Whistler, and E. P. Greenberg. 2005. Complete genome sequence of Vibrio fischeri: a symbiotic bacterium with pathogenic congeners. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:3004-3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schäffer, A. A., L. Aravind, T. L. Madden, S. Shavirin, J. L. Spouge, Y. I. Wolf, E. V. Koonin, and S. A. Altschul. 2001. Improving the accuracy of PSI-BLAST protein database searches with composition-based statistics and other refinements. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:2994-3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schultz, J., F. Milpetz, P. Bork, and C. P. Ponting. 1998. SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: identification of signaling domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:5857-5864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seguritan, V., I. W. Feng, F. Rohwer, M. Swift, and A. M. Segall. 2003. Genome sequences of two closely related Vibrio parahaemolyticus phages, VP16T and VP16C. J. Bacteriol. 185:6434-6447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sobecky, P. A., T. J. Mincer, M. C. Chang, A. Toukdarian, and D. R. Helinski. 1998. Isolation of broad-host-range replicons from marine sediment bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2822-2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stine, O. C., S. Sozhamannan, Q. Gou, S. Zheng, J. G. Morris, Jr., and J. A. Johnson. 2000. Phylogeny of Vibrio cholerae based on recA sequence. Infect. Immun. 68:7180-7185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Story, R. M., I. T. Weber, and T. A. Steitz. 1992. The structure of the E. coli recA protein monomer and polymer. Nature 355:318-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tacket, C. O., F. Hickman, G. V. Pierce, and L. F. Mendoza. 1982. Diarrhea associated with Vibrio fluvialis in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 16:991-992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tatusov, R. L., N. D. Fedorova, J. D. Jackson, A. R. Jacobs, B. Kiryutin, E. V. Koonin, D. M. Krylov, R. Mazumder, S. L. Mekhedov, A. N. Nikolskaya, B. S. Rao, S. Smirnov, A. V. Sverdlov, S. Vasudevan, Y. I. Wolf, J. J. Yin, and D. A. Natale. 2003. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics 4:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tatusov, R. L., E. V. Koonin, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science 24:631-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tatusova, T. A., and T. L. Madden. 1999. Blast 2 sequences: a new tool for comparing protein and nucleotide sequences. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 174:247-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thompson, C. C., F. L. Thompson, K. Vandemeulebroecke, B. Hoste, P. Dawyndt, and J. Swings. 2004. Use of recA as an alternative phylogenetic marker in the family Vibrionaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:919-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thompson, F. L., D. Gevers, C. C. Thompson, P. Dawyndt, S. Naser, B. Hoste, C. B. Munn, and J. Swings. 2005. Phylogeny and molecular identification of Vibrios on the basis of multilocus sequence analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5107-5115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. Clustal-W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties, and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thompson, J. R., M. A. Randa, L. A. Marcelino, A. Tomita-Mitchell, E. Lim, and M. F. Polz. 2004. Diversity and dynamics of a North Atlantic coastal Vibrio community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4103-4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vadivelu, J., S. D. Puthucheary, A. Mitin, C. Y. Wan, B. Van Melle, and J. A. Puthucheary. 1996. Hemolysis and plasmid profiles of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 27:126-131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Waldor, M. K., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1996. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science 272:1910-1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Walker, J. E., M. Saraste, M. J. Runswick, and N. J. Gay. 1982. Distantly related sequences in the α- and β-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases, and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1:945-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wommack, K. E., and R. R. Colwell. 2000. Virioplankton: viruses in aquatic ecosystems. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:69-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu, H., Y. Ma, Y. Zhang, and H. Zhang. 2004. Complete sequence of virulence plasmid pEIB1 from the marine fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum strain MVM425 and location of its replication region. J. Appl. Microbiol. 97:1021-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.