Abstract

Impairment of neutrophil functions and high levels of apoptotic neutrophils have been reported in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients. The aim of the present study was to investigate the direct in vitro effects of the different HIV protease inhibitors (PIs) on neutrophil functions and apoptosis and to explore their mechanisms of action. The effects of nelfinavir (NFV), saquinavir (SQV), lopinavir (LPV), ritonavir (RTV), and amprenavir (APV) in the range of 5 to 100 μg/ml on neutrophil function, apoptosis, and μ-calpain activity were studied. The neutrophil functions studied included superoxide production stimulated by 5 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate, 5 × 10−7 M N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine, and 1 mg/ml opsonized zymosan; specific chemotaxis; random migration; and phagocytosis. Apoptosis was determined by DNA fragmentation, fluorescein isothiocyanate-annexin V binding, and nuclear morphology. All three neutrophil functions, as well as apoptosis, were similarly affected by the PIs. SQV and NFV caused marked inhibition and LPV and RTV caused moderate inhibition, while APV had a minor effect. μ-Calpain activity was not affected by the PIs in neutrophil lysate but was inhibited after its translocation to the membranes after cell stimulation. SQV, which was the most potent inhibitor of neutrophil functions and apoptosis, caused significant inhibition of calpain activity, while APV had no effect. The similar patterns of inhibition of neutrophil functions and apoptosis by the PIs, which coincided with inhibition of calpain activity, suggest the involvement of calpain activity in the regulation of these processes.

Neutrophils are the front line of defense against microbial infection. Neutrophil functions, which include chemotaxis, oxidative respiratory burst, phagocytosis, and killing activity against bacteria and fungi, have been reported to be impaired during human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (10). In patients with advanced HIV infection, neutrophils exhibited decreased chemotaxis (11, 13) due to reduced expression of chemotactic receptors (37). This reduced expression can result from continued exposure to HIV or viral products, such as Tat protein, which can desensitize phagocytes to chemotactic stimuli (40). The defective activity of neutrophils may also contribute to the development of secondary infections in AIDS patients, such as Pneumocystis carinii, Mycobacterium avium-M. intracellulare complex, Histoplasma capsulatum, Toxoplasma gondii, Rhodococcus equi, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Candida albicans infections (38). In addition, it has been shown that neutrophils from AIDS patients exhibit accelerated apoptosis ex vivo (42). Apoptotic neutrophils display morphological and biochemical characteristics of apoptotic cells, including cell shrinkage, compaction of chromatin, and loss of the multilobed shape of the nucleus (1), and are nonfunctional (9, 53). Thus, apoptosis might be one of the mechanisms responsible for the loss of function and reduction in neutrophils in AIDS patients (41). Treatment of AIDS patients with highly active antiretroviral therapy cocktails of compounds, including drugs designed to inhibit the HIV protease (12), leads to a reduction of inflammatory parameters and of neurological problems (28, 39). This treatment induced significant improvement in neutrophil chemotactic and fungicidal activities and enhancement of the oxidative burst, although there was no full recovery of these functions (35, 36). It has been shown that the protease inhibitors (PIs) counteract T-cell depletion (23, 29) and reduce apoptosis of T cells and neutrophils (36) in AIDS patients, even in the absence of inhibition of viral spread. Furthermore, PIs have been shown to increase in vitro cell viability by inhibiting apoptosis of infected and uninfected T cells (48, 52).

The aim of the present study was to determine the direct effects of the various HIV PIs on neutrophil functions and on apoptosis. Since the involvement of the neutrophil cysteine protease calpain has been reported in spontaneous apoptosis (2, 25, 26, 49) and in neutrophil functions (8, 17, 25, 34), we studied whether calpain is affected by the PIs. The present study demonstrates that chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and superoxide production, as well as apoptosis, are inhibited by the various PIs. The pattern of inhibition of neutrophil functions and apoptosis by the PIs coincided with inhibition of μ-calpain activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Neutrophil purification.

Neutrophils were isolated from heparinized blood of healthy donors (within 3 hours after the collection of blood) at 95% purity by Ficoll/Hypaque centrifugation, dextran sedimentation, and hypotonic lysis of erythrocytes, and their viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion (5). This study was approved by the Helsinki Committee of the Soroka University Medical Center.

PIs.

Nelfinavir (NFV) and saquinavir (SQV) were provided by Roche Pharmaceuticals, Tel Aviv, Israel. Lopinavir (LPV), ritonavir (RTV), and amprenavir (APV) were provided by Abbott Laboratories, Illinois. Apart from SQV, which was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), all the protease inhibitors were dissolved in ethanol (final solvent concentration, 0.025% [vol/vol]).

Superoxide anion measurements.

The production of superoxide anion (O2−) by neutrophils was measured as the superoxide dismutase-inhibitable reduction of acetyl ferricytochrome c by the microtiter plate technique, as previously described (7), with modifications. Cells (5 × 105/well) were suspended in 100 μl Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing acetyl ferricytochrome c (150 mM), with or without PIs, and stimulated by the addition of 5 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), 1 mg/ml opsonized zymosan (OZ), or 5 × 10−7 M N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP). In addition, superoxide production in nonstimulated cells was determined. The reduction of acetyl ferricytochrome c was followed by a change of absorbance at 550 nm at 2- to 5-min intervals on a Thermomax Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, CA). The maximal rates of superoxide generation were determined and expressed as nanomoles O2−/106 cells/10 min using an extinction coefficient (E550) of 21 mM−1 cm−1. OZ was prepared as follows: 20 mg OZ was incubated with 1 ml of pooled human serum (lipopolysaccharide free) for 1 h at 37°C and washed three times with HBSS buffer.

Chemotaxis.

Chemotaxis was assessed as previously described (33). Agarose was dissolved in sterile, distilled boiling water for 10 min. After being cooled to 48°C in a water bath, the agarose was mixed with an equal volume of prewarmed 2× minimal essential medium with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum and 7.5% (wt/vol) sodium bicarbonate. Five milliliters of the agarose medium was delivered to 60- by 15-mm tissue culture dishes and allowed to harden. A series of three wells, 2.4 mm in diameter and spaced 2.4 mm apart, were formed. In the first well, 10 μl of fMLP (10−7 M) was placed; in the center well, a 10-μl aliquot of the cell suspension (5 × 105) in HBSS, with or without PIs, was placed; and in the third well, 10 μl of HBSS was placed. The dishes were subsequently incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 in air for 2 h. The plates were fixed by the addition of 3 ml methanol at 4°C overnight. After the methanol was poured off, the plates were placed in glutaraldehyde (2.5%) for 30 min at room temperature. The agarose gel was removed intact after fixation, and the plates were stained with Giemsa stain and air dried. The random migration and the linear migration toward the chemoattractant (fMLP) were measured under a light microscope. Chemotaxis was defined as the ratio between the chemotactic and random migrations.

Phagocytosis.

Cells (5 × 106/ml) suspended in HBSS were preincubated with the PIs and incubated at 37°C for 15 min with 5 μl of OZ (1 mg/ml). Subsequently, the cells were smeared and stained with differential Wright-Giemsa stain. Phagocytosis was determined under the microscope in at least 100 cells and defined as the percentage of cells containing more than two phagocytized particles of OZ (33).

Assessment of apoptosis.

Isolated neutrophils (5 × 106/ml) were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum and glutamine (2 mM) for 16 h at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere to induce apoptosis (42). Where indicated, 25 μg/ml of different PIs was incubated with the neutrophils under the same conditions. Apoptosis was assayed by three different independent methods: (i) microscopic examination of apoptotic cells after smearing and staining them with May Grunwald/Giemsa stain, in which neutrophils were assessed for morphological changes characteristic of apoptosis (nuclear condensation) (45); (ii) fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis of cells labeled with an annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate kit (Bender MedSystems, Vienna, Austria), in which labeled cells were applied to flow microfluorimetry on FACS (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) (19); and (iii) nuclear fragmentation of apoptotic neutrophils, examined as described previously (4). A suspension of neutrophils (107) was supplemented with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to a final concentration of 0.5%, mixed vigorously, and incubated at 65°C for 1 h to obtain a viscous and clear cell lysate. The lysate was then treated with 20 μg/ml of RNase A (37°C; 1 h) and 20 μg/ml of proteinase K (50°C; 1 h) and extracted twice with an equal volume of phenol chloroform (1:1). DNA in the aqueous phase was precipitated in 0.3 M sodium acetate-75% ethanol at −20°C. Precipitates were pelleted by centrifugation (13,000 × g; 10 min; 4°C), washed with ice-cold 70% ethanol, and air dried. For electrophoresis, DNA samples were dissolved in Tris-EDTA buffer. Five micrograms of genomic DNA from each sample was separated on a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (pH 8.2). The relative amount of the fragmented DNA was quantified by using densitometry in ImageJ processing and analysis.

Cell lysate and calpain activity.

Calpain activity was measured in (i) neutrophil lysates, (ii) purified μ-calpain, and (iii) membrane fractions. For the samples of neutrophil lysates or purified μ-calpain, the PIs were added after the samples were prepared. (i) Neutrophil lysate was prepared as described previously (14). Cells (107) were suspended in 0.1 ml of lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 40 mM sucrose) and subjected to five cycles of freezing-thawing. (ii) Purified μ-calpain was obtained from the calpain activity assay kit (Oncogene, San Diego, CA). (iii) Membranes were separated as described previously (30). Neutrophils (106 cells/ml) suspended in HBSS were preincubated with each of the PIs at a concentration of 25 μg/ml for 10 min and stimulated with fMLP (3 min). After stimulation, the cells were centrifuged and suspended (108 cells/ml) in buffer [100 mM KCl, 3 mM NaCl, 3.5 mM MgCl2, 1.25 mM EGTA, 1 mM ATP, 10 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid), pH 7.4] containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μM aprotinin, and 10 μM benzamidin at 4°C and were sonicated three times for 10 s each time, resulting in about 95% cell breakage. Nuclei, granules, and unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation (2 min at 15,000 × g), and the supernatant was centrifuged (30 min at 100,000 × g) to obtain a cell membrane pellet. The membranes were solubilized in 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% NP-40. The activity of μ-calpain was assayed in each sample using a fluorigenic synthetic substrate, Suc-LLVY AMC, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Oncogene, San Diego, CA). Activity was measured in a TECAN spectrofluorimeter at an excitation of 360 nm and an emission of 465 nm for 40 min in continuous agitation.

Immunoblot analysis.

Membrane fractions (2 × 106 cell equivalents) were boiled in SDS sample buffer and electrophoresed on a 7% or 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel (27). The resolved proteins were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and the detection of μ-calpain protein was done using monoclonal antibodies that recognized the 80-kDa large subunit (kindly provided by Nechama S. Kosower, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel), followed by reaction with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-mouse antibody, which served as a secondary antibody, according to established procedures (15). Detection of the NADPH oxidase membrane subunit p22phox was performed using goat antibodies against p22phox (31). The relative amounts of calpain and p22phox in the membrane fractions were quantitated using densitometry in ImageJ processing and analysis.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical evaluation of the differences from the control was carried out by an unpaired Student's t test with a 95% confidence interval. The differences between the various PI treatments were analyzed by analysis of variance.

RESULTS

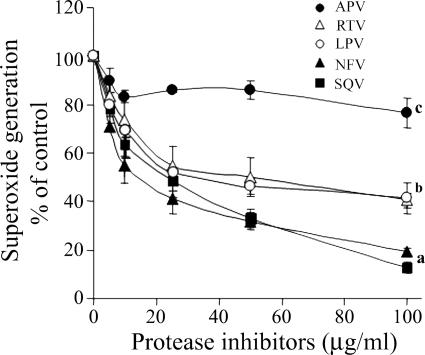

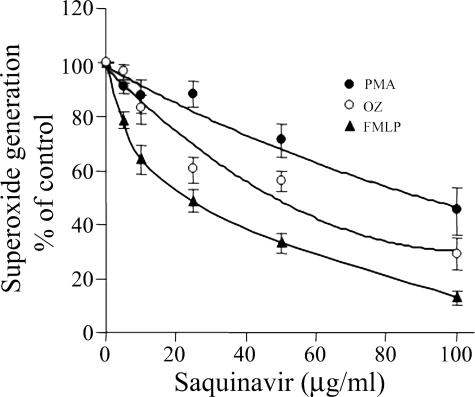

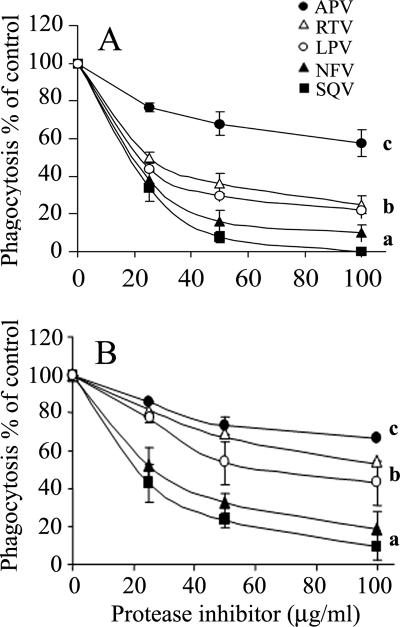

The effects of SQV, NFV, LPV, RTV, and APV on neutrophil functions were studied in vitro. Figure 1 shows the dose-response effects of PIs on superoxide production stimulated by fMLP. The presence of these PIs during the superoxide production assay caused significant inhibition in a rank order of SQV = NFV > LPV = RTV > APV. While SQV and NFV at 100 μg/ml caused almost complete inhibition, APV caused only slight and insignificant inhibition. The effects of the PIs were immediate, since preincubation for up to 60 min prior to stimulation did not change the effects (data not shown). The inhibitory effects of the PIs on superoxide production were not restricted to stimulation with fMLP but were also detected when neutrophils were stimulated with PMA or OZ, although to a lesser but significant extent (P < 0.001), as shown in the dose-response inhibition of SQV on superoxide production stimulated with the three stimuli (Fig. 2). The effects of the PIs on neutrophil chemotaxis and on phagocytosis were similar to those on superoxide production. The chemotactic responsiveness of neutrophils was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by the presence of the PIs during the assay, as shown in Fig. 3A. SQV at 100 μg/ml caused total inhibition of chemotaxis, while APV caused only slight inhibition. Likewise, phagocytosis of OZ particles by neutrophils was inhibited by the PIs in a similar dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3B). Thus, there were similar rank order effects of the PIs on the three different functions: superoxide production, chemotaxis, and phagocytosis.

FIG. 1.

The dose-response effects of PIs on superoxide production stimulated by fMLP (5 × 10−7 M). PIs were added to the reaction mixture before stimulation. The results, expressed as percentages of the control, are means ± standard errors of the mean from three experiments. DMSO was added to the control of SQV, and ethanol was added to the control of the other PIs. •, APV; ▵, RTV; ○, LPV; ▴, NFV; ▪, SQV. For all PIs, there was significant inhibition compared to the control (P < 0.001). a, significant differences compared to b and c (P < 0.001); b, significant differences compared to c (P < 0.001).

FIG. 2.

The effects of SQV on superoxide production stimulated by the different agents. There was a dose-response inhibition of SQV in a range of 5 to 100 μg/ml on superoxide production stimulated by PMA (5 ng/ml) (•), fMLP (5 × 10−7 M) (▴), or OZ (1 mg/ml) (○). SQV was added to the reaction mixture before stimulation. DMSO was added to the control. The results, expressed as percentages of the control, are means ± standard errors of the mean of three experiments. There were significant inhibition compared to the control and significant differences between the effects of the three stimuli (P < 0.001).

FIG. 3.

The effect of HIV PIs on neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis. (A) Chemotaxis; dose-dependent effects of the PIs on chemotactic migration toward 10−7 M fMLP and on random migration. The migration was assayed for 2 h in the presence of the PIs. DMSO was added to the control of SQV, and ethanol was added to the control of the other PIs. For all PIs, there was significant inhibition compared to the control (P < 0.001). a, significant differences compared to b and c (P < 0.001); b, significant differences compared to c (P < 0.001). (B) Phagocytosis; dose-dependent effects of the PIs on phagocytosis of OZ. Neutrophil phagocytosis was assayed for 15 min in the presence of the PIs. DMSO was added to the control of SQV, and ethanol was added to the control of the other PIs. The results, expressed as percentages of the control, are means ± standard errors of the mean from three experiments. a, significant differences compared to b and c (P < 0.001); b, significant difference compared to c (P < 0.01). The symbols are as described in the legend to Fig. 1, and the results, expressed as percentages of the control, are means ± standard errors of the mean of three experiments.

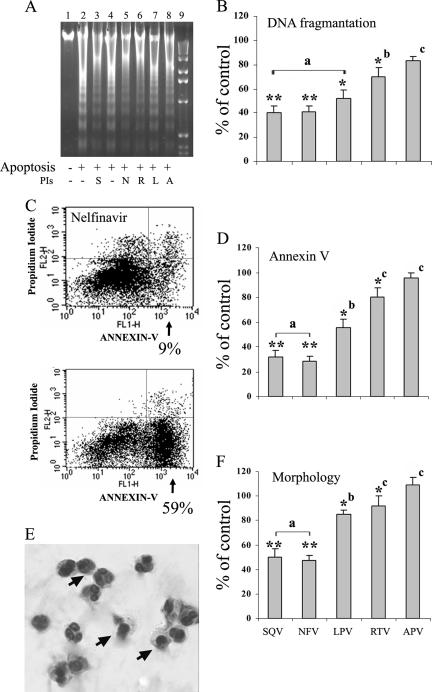

The in vitro effects of the PIs on spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis were studied by three different methods. Spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis was induced by overnight culture in the presence of 25 μg/ml of either the PIs or their solvents. Figure 4A presents the effects of the PIs as determined by DNA fragmentation. While cultured neutrophils exhibited significant DNA fragmentation, the presence of the different PIs during culture attenuated this process. The relative amounts of the fragmented DNAs quantified by densitometry presented in a bar graph (Fig. 4B) show that the PIs most effective in inhibiting neutrophil functions were also the most effective in reducing apoptosis. Figure 4C presents an example of the effects of the PIs on phosphatidylserine exposure as evidenced by annexin V-labeled neutrophils. As shown in the FACS analysis, 59% of early apoptotic cells were detected in cultured neutrophils, while only 9% of early apoptotic cells were detected in the presence of NFV. The effects of the various PIs on neutrophil apoptosis, as determined by annexin V-labeled neutrophils, is shown in a bar graph (Fig. 4D). The changes in the nuclear morphology from a polymorphonuclear form in normal neutrophils to condensed nuclei in apoptotic cells areshown by Giemsa staining in Fig. 5E. The effects of the various PIs on apoptosis as determined by Giemsa staining are presented in a bar graph (Fig. 4F). According to the three independent methodologies, SQV and NFV were the most potent PIs in inhibiting spontaneous apoptosis, while APV was the least potent.

FIG. 4.

The effects of HIV PIs on spontaneous apoptosis of peripheral blood neutrophils. Neutrophils were cultured for 16 h in the absence or presence of the different PIs (25 μg/ml) or their solvents. (A) DNA fragmentation analysis. Starting from the left side, lane 1, freshly isolated neutrophils; lane 2, cultured neutrophils (in the presence of DMSO, the solvent of SQV); lane 3, cultured neutrophils in the presence of SQV (S); lane 4, cultured neutrophils (in the presence of ethanol, the solvent of all other PIs); lanes 5 to 8, cultured neutrophils in the presence of NFV (N), RTV (R), LPV (L), and APV (A), respectively; lane 9, 1-kb ladder. (B) Bar graphs of the effects of the PIs on neutrophil apoptosis detected by the relative amounts of the fragmented DNAs, which were quantified by using densitometry in ImageJ processing and analysis. (C) Fluorescein isothiocyanate-annexin V binding assayed by flow cytometric analysis. Shown are representative results for cultured neutrophils in the presence of NFV (top) or its solvent (bottom). Early apoptotic cells with intact membranes were annexin V positive and propidium iodide negative (lower right quadrant). Late apoptotic or necrotic cells that lost cell membrane integrity were positive for both annexin V and propidium iodide (upper right quadrant). (D) Bar graphs of the effects of PIs on neutrophil apoptosis detected by labeled annexin V. (E) Giemsa staining of cultured neutrophils. The arrow shows the condensed nuclei in apoptotic neutrophils. A total of 40 to 65% of neutrophils cultured for 16 h were apoptotic (F) Bar graphs of the effects of the PIs on neutrophil apoptosis detected by changes in nuclear morphology after Giemsa staining. The results, expressed as percentages of the control, are means ± standard errors of the mean of four experiments. The significances of the results compared to the control were as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001. P values were as follows: a in comparison to b and c, <0.001 (for panels B, D, and F); b in comparison to c, 0.2, <0.001, and <0.01 (for panels B, D, and F, respectively). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

FIG. 5.

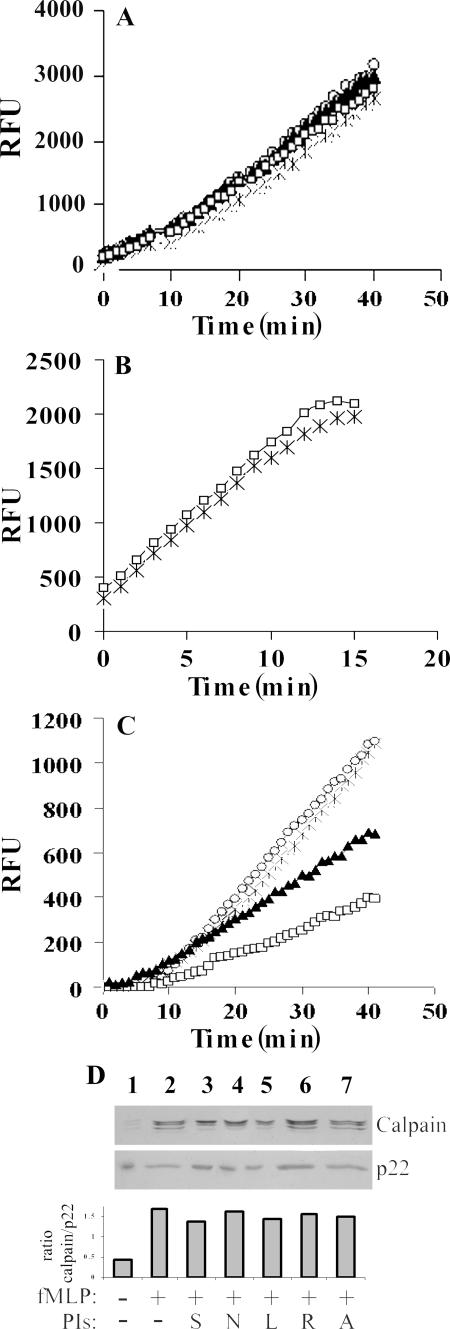

The effects of HIV PIs on calpain activity. (A) Neutrophil lysates. Cell lysate equivalents (1.5 × 106) were pretreated (10 min) without (×) or with NFV (▴), SQV (□), or APV (○) at 100 μg/ml before assay of calpain activity using 200 μM of the calpain substrate Suc-LLVY AMC. The results are presented as relative fluorescence units (RFU). (B) Purified μ-calpain. Recombinant μ-calpain (100 ng) was pretreated with solvent (×) or 100 μg/ml SQV (□) for 10 min before assay of activity using the synthetic substrate Suc-LLVY AMC. (C) Neutrophil membranes. Membrane fractions were prepared from neutrophils (106 cells/ml) preincubated without (×) or with the PIs NFV (▴), SQV (□), and APV (○) at a concentration of 25 μg/ml for 10 min and stimulated for 3 min with fMLP, and 1 × 107 cell membrane equivalents were analyzed for calpain activity using the synthetic substrate Suc-LLVY AMC. The significance of the effect was a P value of <0.001. (D) The effects of the PIs on calpain in membrane fractions of stimulated neutrophils. Membrane fractions from neutrophils preincubated without PIs or with PIs at a concentration of 25 μg/ml for 10 min and stimulated for 3 min with fMLP were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subjected to Western blot analysis against anti-μ-calpain or anti-p22phox antibodies to confirm equal loading of membrane fractions; 5 × 106 cell membrane equivalents were applied per lane. Starting from the left side, lane 1, unstimulated neutrophils; lane 2, stimulated neutrophils; lanes 3 to 7, stimulated neutrophils in the presence of SQV (S), NFV (N), LPV (L), RTV (R), and APV (A), respectively. The relative amounts of the proteins were quantified using densitometry, and the ratios between μ-calpain and p22phox membrane proteins are expressed in the bar graph. The results are from one representative experiment out of three presenting identical results.

The effects of the PIs on neutrophil lysates and on recombinant calpain μ isoform were studied. Addition of 100 μg/ml of the two most effective PIs, SQV and NFV, to the lysates did not cause any inhibition of calpain activity, nor did higher concentrations up to 400 μg/ml (data not shown). Likewise, the most effective PI, SQV, had no effect on recombinant μ-calpain activity (Fig. 5B). Calpain has been shown to translocate to the membranes after cell stimulation (43, 50); thus, its activity was assayed on the membrane fractions separated from stimulated neutrophils. The effects of the two most potent PIs, SQV and NFV, as well as that of APV, which had only slight effects on neutrophil functions and on apoptosis, were tested on calpain activity after its translocation to neutrophil membranes. As shown in Fig. 5C, membrane fractions of cells preincubated with either SQV or NFV exhibited significantly (P < 0.001) lower calpain activity than the membrane fractions of the untreated control cells. SQV was more potent in inhibiting calpain activity (P < 0.001), while APV did not cause any inhibition.

To determine whether the inhibition of calpain activity by the PIs was due to a direct effect on the enzyme or to inhibition of its translocation to the membranes, their effects on calpain translocation were analyzed. As shown in Fig. 5D, stimulation of neutrophils with fMLP caused a marked translocation of calpain to the membrane fractions, as determined by immunoblotting. Preincubation of neutrophils with each of the PIs did not affect the levels of calpain in the membrane fractions of stimulated neutrophils.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that PIs have a direct effect on inhibiting neutrophil functions (superoxide production, chemotaxis, and phagocytosis) and on neutrophil apoptosis in similar rank orders. SQV and NFV, the most effective PIs in attenuating neutrophil functions, caused a significant inhibition of apoptosis, while APV had only small effects on neutrophil functions and on neutrophil apoptosis. The concentrations of the PIs used in this study are readily achievable with oral dosing regimens in humans (46, 51). The PIs act by blocking the HIV aspartyl protease, a viral enzyme that cleaves the HIV Gag and Gag-Pol polyprotein backbone, thereby interrupting the viral life cycle. These PIs have been reported to have different affinities, inhibition constants, physiochemical properties, and cell culture efficacies (16, 47). The highest cell culture efficacies were detected for SQV and NFV and the lowest for APV. In addition, in HIV pharmacotherapy, it is important to consider intracellular drug concentrations. The distribution of the PIs from plasma into cells and tissues is dependent on many factors, including uptake mechanisms and the relative affinities for cells and tissues versus plasma components (18). The PIs show differential accumulations within lymphoblastoid cell lines (21) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of virologically suppressed patients in vivo, with NFV and SQV accumulations higher than those of LPV and RTV (24). Thus, the rank order effects of the different PIs on neutrophil functions and apoptosis shown in our study are similar to their reported cell culture efficacies (which represent the concentrations of inhibitor that result in 50% inhibition of HIV type 1 replication [47]) and to their rank order for cellular accumulation (18, 24). The significant recovery of neutrophil functions reported after the treatment of HIV patients (35) raises the possibility that the main in vivo effect of the PIs on neutrophils is in reducing the number of functionally defective apoptotic cells (53). However, the fact that there was no full recovery in those patients may be explained by the inhibitory effects of the PIs on neutrophil function.

The similar patterns of inhibition of the three different neutrophil functions and neutrophil apoptosis raised the possibility that the different processes have a common key regulator. Several studies have reported the involvement of calpain in regulation of different neutrophil functions, as well as of apoptosis. It has been shown that inhibition of calpain activation prevents phagocytosis of iC3b-opsonized particles (8) and neutrophil transendothelial migration or adhesion to endothelial cells (3). Calpain activities are responsible for rearrangement of the plasmalemmal cytoskeleton, including dissociation of protein from actin and loss of immunodetectable α-actinin and ezrin, a process that is important for neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis (17, 25), and may affect membrane NADPH oxidase activity. In addition, calpain has been implicated as a critical calcium-dependent regulator of the actin cytoskeleton and cell migration (20, 22). The role of calpain in the regulation of apoptosis, in addition to that of the caspases, has been recently reported (2, 6, 25). While constitutive calpain activity in neutrophils has been shown to mediate apoptosis by degradation of a caspase inhibitor, inhibition of calpain by calpeptin calpastatin delays the initiation of apoptosis (26, 49).

The present study demonstrates that the different PIs inhibited calpain activity in the membrane fractions of activated neutrophils in the same rank order of inhibition as for neutrophil functions and apoptosis. These results, together with the reported finding that calpain is involved in both neutrophil functions and apoptosis, raise the possibility that the effects of the PIs on both processes are mediated by calpain. In line with this suggestion, it was recently reported that elevated apoptosis and calpain activity of the neutrophils of AIDS patients decreased after PI treatment (32). HIV protease and calpain share similar secondary structures, in which the active site is flanked by hydrophobic regions (51). Although HIV protease is an aspartyl protease while calpain is a cysteine protease, peptide aldehyde inhibitors of calpain have been shown to inhibit HIV protease (44). The inhibition of μ-calpain in the membrane fraction by the PIs demonstrated in our study (Fig. 5C) is in line with the findings that μ-calpain, but not m-calpain, is the dominant isoform in neutrophils (50) and is activated in spontaneous and Fas receptor-mediated apoptosis of neutrophils (2). μ-Calpain activity was inhibited by the PIs after its translocation to the plasma membranes induced by neutrophil stimulation (Fig. 5C), but not in neutrophil lysates (Fig. 5A) or in its purified form (Fig. 5B), suggesting that its activated form is more susceptible to inhibition. Thus, it is possible that the site of the PI binding is exposed only when calpain is found on the membranes after its translocation.

In conclusion, the PIs tested in our study exhibited direct effects on neutrophil functions and on apoptosis, with similar rank orders. In addition, the PIs most effective in these processes were also potent in inhibiting neutrophil calpain activity in the membrane fractions, suggesting the involvement of calpain activity in the regulation of these processes. The treatment of HIV patients with PIs, which brings about improvement but not total recovery of neutrophil functions, probably reflects a balance between their effects in reducing the number of apoptotic cells that are functionally defective and their direct inhibition of neutrophil functions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Israel Ministry of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 September 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akgul, C., D. A. Moulding, and S. W. Edwards. 2001. Molecular control of neutrophil apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 487:318-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altznauer, F., S. Conus, A. Cavalli, G. Folkers, and H. U. Simon. 2004. Calpain-1 regulates Bax and subsequent Smac-dependent caspase-3 activation in neutrophil apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:5947-5957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, S. I., N. A. Hotchin, G. B. Nash, S. Dewitt, M. B. Hallett, M. K. Squier, A. J. Sehnert, K. S. Sellins, A. M. Malkinson, E. Takano, J. J. Cohen, S. Kobayashi, K. Yamashita, T. Takeoka, T. Ohtsuki, Y. Suzuki, R. Takahashi, K. Yamamoto, S. H. Kaufmann, T. Uchiyama, M. Sasada, and A. Takahashi. 2000. Role of the cytoskeleton in rapid activation of CD11b/CD18 function and its subsequent downregulation in neutrophils. J. Cell Sci. 113:2737-2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baran, J., K. Guzik, W. Hryniewicz, M. Ernst, H. D. Flad, and J. Pryjma. 1996. Apoptosis of monocytes and prolonged survival of granulocytes as a result of phagocytosis of bacteria. Infect. Immun. 64:4242-4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyum, A. 1976. Isolation of lymphocytes, granulocytes and macrophages. Scand. J. Immunol. Suppl. 5:9-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan, S. L., and M. P. Mattson. 1999. Caspase and calpain substrates: roles in synaptic plasticity and cell death. J. Neurosci. Res. 58:167-190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dana, R., T. L. Leto, H. L. Malech, and R. Levy. 1998. Essential requirement of cytosolic phospholipase A2 for activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:441-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dewitt, S., and M. B. Hallett. 2002. Cytosolic free Ca2+ changes and calpain activation are required for beta integrin-accelerated phagocytosis by human neutrophils. J. Cell Biol. 159:181-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dransfield, I., S. C. Stocks, and C. Haslett. 1995. Regulation of cell adhesion molecule expression and function associated with neutrophil apoptosis. Blood 85:3264-3273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elbim, C., M. H. Prevot, F. Bouscarat, E. Franzini, S. Chollet-Martin, J. Hakim, and M. A. Gougerot-Pocidalo. 1995. Impairment of polymorphonuclear neutrophil function in HIV-infected patients. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 25(Suppl. 2):S66-S70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis, M., S. Gupta, S. Galant, S. Hakim, C. VandeVen, C. Toy, and M. S. Cairo. 1988. Impaired neutrophil function in patients with AIDS or AIDS-related complex: a comprehensive evaluation. J. Infect. Dis. 158:1268-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flexner, C. 1998. HIV-protease inhibitors. N. Engl. J. Med. 338:1281-1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flo, R. W., A. Naess, A. Nilsen, S. Harthug, and C. O. Solberg. 1994. A longitudinal study of phagocyte function in HIV-infected patients. AIDS 8:771-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghibelli, L., F. Mengoni, M. Lichtner, S. Coppola, M. De Nicola, A. Bergamaschi, C. Mastroianni, and V. Vullo. 2003. Anti-apoptotic effect of HIV protease inhibitors via direct inhibition of calpain. Biochem. Pharmacol. 66:1505-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glaser, T., N. Schwarz-Benmeir, S. Barnoy, S. Barak, Z. Eshhar, and N. S. Kosower. 1994. Calpain (Ca2+-dependent thiol protease) in erythrocytes of young and old individuals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:7879-7883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Granfors, M. T., J. S. Wang, L. I. Kajosaari, J. Laitila, P. J. Neuvonen, and J. T. Backman. 2006. Differential inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A4, 3A5, and 3A7 by five human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) protease inhibitors in vitro. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 98:79-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofman, P. 2004. Molecular regulation of neutrophil apoptosis and potential targets for therapeutic strategy against the inflammatory process. Curr. Drug Targets Inflamm. Allergy 3:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoggard, P. G., and A. Owen. 2003. The mechanisms that control intracellular penetration of the HIV protease inhibitors. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:493-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Homburg, C. H., M. de Haas, A. E. von dem Borne, A. J. Verhoeven, C. P. Reutelingsperger, and D. Roos. 1995. Human neutrophils lose their surface Fc gamma RIII and acquire Annexin V binding sites during apoptosis in vitro. Blood 85:532-540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huttenlocher, A., S. P. Palecek, Q. Lu, W. Zhang, R. L. Mellgren, D. A. Lauffenburger, M. H. Ginsberg, and A. F. Horwitz. 1997. Regulation of cell migration by the calcium-dependent protease calpain. J. Biol. Chem. 272:32719-32722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones, K., P. G. Hoggard, S. D. Sales, S. Khoo, R. Davey, and D. J. Back. 2001. Differences in the intracellular accumulation of HIV protease inhibitors in vitro and the effect of active transport. AIDS 15:675-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kan, H., Y. Ruan, and K. U. Malik. 1996. Involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase and translocation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 to the nuclear envelope in acetylcholine-induced prostacyclin synthesis in rabbit coronary endothelial cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 50:1139-1147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufmann, D., G. Pantaleo, P. Sudre, A. Telenti, et al. 1998. CD4-cell count in HIV-1-infected individuals remaining viraemic with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Lancet 351:723-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khoo, S. H., P. G. Hoggard, I. Williams, E. R. Meaden, P. Newton, E. G. Wilkins, A. Smith, J. F. Tjia, J. Lloyd, K. Jones, N. Beeching, P. Carey, B. Peters, and D. J. Back. 2002. Intracellular accumulation of human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3228-3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knepper-Nicolai, B., J. Savill, and S. B. Brown. 1998. Constitutive apoptosis in human neutrophils requires synergy between calpains and the proteasome downstream of caspases. J. Biol. Chem. 273:30530-30536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi, S., K. Yamashita, T. Takeoka, T. Ohtsuki, Y. Suzuki, R. Takahashi, K. Yamamoto, S. H. Kaufmann, T. Uchiyama, M. Sasada, and A. Takahashi. 2002. Calpain-mediated X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis degradation in neutrophil apoptosis and its impairment in chronic neutrophilic leukemia. J. Biol. Chem. 277:33968-33977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ledergerber, B., M. Egger, M. Opravil, A. Telenti, B. Hirschel, M. Battegay, P. Vernazza, P. Sudre, M. Flepp, H. Furrer, P. Francioli, R. Weber, et al. 1999. Clinical progression and virological failure on highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 patients: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 353:863-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levitz, S. M. 1998. Improvement in CD4+ cell counts despite persistently detectable HIV load. N. Engl. J. Med. 338:1074-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levy, R., H. L. Malech, and D. Rotrosen. 1990. Production of myeloid cell cytosols functionally and immunochemically deficient in the 47 kDa or 67 kDa NADPH oxidase cytosolic factors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 170:1114-1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levy, R., D. Rotrosen, O. Nagauker, T. L. Leto, and H. L. Malech. 1990. Induction of the respiratory burst in HL-60 cells. Correlation of function and protein expression. J. Immunol. 145:2595-2601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lichtner, M., F. Mengoni, C. M. Mastroianni, I. Sauzullo, R. Rossi, M. De Nicola, V. Vullo, and L. Ghibelli. 2006. HIV protease inhibitor therapy reverses neutrophil apoptosis in AIDS patients by direct calpain inhibition. Apoptosis 11:781-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liel, Y., A. Rudich, O. Nagauker Shriker, T. Yermiyahu, and R. Levy. 1994. Monocyte dysfunction in patients with Gaucher disease: evidence for interference of glucocerebroside with superoxide generation. Blood 83:2646-2653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lokuta, M. A., P. A. Nuzzi, and A. Huttenlocher. 2003. Calpain regulates neutrophil chemotaxis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:4006-4011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mastroianni, C. M., M. Lichtner, F. Mengoni, C. D'Agostino, G. Forcina, G. d'Ettorre, P. Santopadre, and V. Vullo. 1999. Improvement in neutrophil and monocyte function during highly active antiretroviral treatment of HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS 13:883-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mastroianni, C. M., F. Mengoni, M. Lichtner, C. D'Agostino, G. d'Ettorre, G. Forcina, M. Marzi, G. Russo, A. P. Massetti, and V. Vullo. 2000. Ex vivo and in vitro effect of human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors on neutrophil apoptosis. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1536-1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meddows-Taylor, S., D. J. Martin, and C. T. Tiemessen. 1998. Reduced expression of interleukin-8 receptors A and B on polymorphonuclear neutrophils from persons with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 disease and pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 177:921-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meltzer, M. S., M. Nakamura, B. D. Hansen, J. A. Turpin, D. C. Kalter, and H. E. Gendelman. 1990. Macrophages as susceptible targets for HIV infection, persistent viral reservoirs in tissue, and key immunoregulatory cells that control levels of virus replication and extent of disease. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 6:967-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mezzaroma, I., M. Carlesimo, E. Pinter, D. S. Muratori, F. Di Sora, F. Chiarotti, M. G. Cunsolo, G. Sacco, and F. Aiuti. 1999. Clinical and immunologic response without decrease in virus load in patients with AIDS after 24 months of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:1423-1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitola, S., S. Sozzani, W. Luini, L. Primo, A. Borsatti, H. Weich, and F. Bussolino. 1997. Tat-human immunodeficiency virus-1 induces human monocyte chemotaxis by activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1. Blood 90:1365-1372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pitrak, D. L., S. H. Sutton, H. C. Tsai, K. M. Mullane, and A. K. Pau. 1999. Reversal of accelerated neutrophil apoptosis and restoration of respiratory burst activity with r-metHuG-CSF (Filgrastim therapy in patients with AIDS). AIDS 13:427-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pitrak, D. L., H. C. Tsai, K. M. Mullane, S. H. Sutton, and P. Stevens. 1996. Accelerated neutrophil apoptosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 98:2714-2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pontremoli, S., E. Melloni, F. Salamino, M. Patrone, M. Michetti, and B. L. Horecker. 1989. Activation of neutrophil calpain following its translocation to the plasma membrane induced by phorbol ester or fMet-Leu-Phe. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 160:737-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarubbi, E., P. F. Seneci, M. R. Angelastro, N. P. Peet, M. Denaro, and K. Islam. 1993. Peptide aldehydes as inhibitors of HIV protease. FEBS Lett. 319:253-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Savill, J. S., A. H. Wyllie, J. E. Henson, M. J. Walport, P. M. Henson, and C. Haslett. 1989. Macrophage phagocytosis of aging neutrophils in inflammation. Programmed cell death in the neutrophil leads to its recognition by macrophages. J. Clin. Investig. 83:865-875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shibata, N., W. Gao, H. Okamoto, T. Kishida, K. Iwasaki, Y. Yoshikawa, and K. Takada. 2002. Drug interactions between HIV protease inhibitors based on a physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model. J. Pharm. Sci. 91:680-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shuman, C. F., L. Vrang, and U. H. Danielson. 2004. Improved structure-activity relationship analysis of HIV-1 protease inhibitors using interaction kinetic data. J. Med. Chem. 47:5953-5961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sloand, E. M., P. N. Kumar, S. Kim, A. Chaudhuri, F. F. Weichold, and N. S. Young. 1999. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitor modulates activation of peripheral blood CD4+ T cells and decreases their susceptibility to apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Blood 94:1021-1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Squier, M. K., A. J. Sehnert, K. S. Sellins, A. M. Malkinson, E. Takano, and J. J. Cohen. 1999. Calpain and calpastatin regulate neutrophil apoptosis. J. Cell Physiol. 178:311-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tian, W., S. Dewitt, I. Laffafian, and M. B. Hallett. 2004. Ca2+, calpain and 3-phosphorylated phosphatidyl inositides; decision-making signals in neutrophils as potential targets for therapeutics. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 56:565-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wan, W., and P. B. DePetrillo. 2002. Ritonavir inhibition of calcium-activated neutral proteases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 63:1481-1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weichold, F. F., J. L. Bryant, S. Pati, O. Barabitskaya, R. C. Gallo, and M. S. Reitz, Jr. 1999. HIV-1 protease inhibitor ritonavir modulates susceptibility to apoptosis of uninfected T cells. J. Hum. Virol. 2:261-269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whyte, M. K., L. C. Meagher, J. MacDermot, and C. Haslett. 1993. Impairment of function in aging neutrophils is associated with apoptosis. J. Immunol. 150:5124-5134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]