Abstract

Inactivation of the quorum-sensing regulator HapR causes Vibrio cholerae El Tor biotype strain C7258 to adopt a rugose colonial morphology that correlates with enhanced biofilm formation. V. cholerae mutants lacking the cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein (CRP) produce very little HapR, which results in elevated expression of Vibrio exopolysaccharide (vps) genes and biofilm compared to the wild type. However, Δcrp mutants still exhibited smooth colonial morphology and expressed reduced levels of vps genes compared to isogenic hapR mutants. In this study we demonstrate that deletion of crp and cya (adenylate cyclase) converts a rugose ΔhapR mutant to a smooth one. The smooth ΔhapR Δcrp and ΔhapR Δcya double mutants could be converted back to rugose by complementation with crp and cya, respectively. CRP was found to enhance the expression of VpsR, a strong activator of vps expression, but to diminish transcription of VpsT. Ectopic expression of VpsR in smooth ΔhapR Δcrp and ΔhapR Δcya double mutants restored rugose colonial morphology. Lowering intracellular cAMP levels in a ΔhapR mutant by the addition of glucose diminished VpsR expression and colonial rugosity. On the basis of our results, we propose a model for the regulatory input of CRP on exopolysaccharide biosynthesis.

Cholera is a paradigm waterborne disease caused by Vibrio cholerae serogroups O1 and O139, which continue to cause seasonal outbreaks in heavily populated regions in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. V. cholerae is transmitted through contaminated food and drinking water as well as person to person through the fecal-oral route. The existence of an aquatic reservoir of serogroup O1 and O139 toxigenic strains has not been established. However, their capacity to survive and persist in estuarine and brackish waters is widely accepted (6, 8, 22). V. cholerae has been shown to alternate between a free-swimming planktonic lifestyle and biofilm communities attached to biotic and abiotic surfaces. In the biofilm lifestyle, V. cholerae has been found in association with phytoplankton and zooplankton (11, 12). In addition, large clumps of aggregated partially dormant V. cholerae cells can be detected in surface water as biofilms that resist cultivation in conventional microbiological media (7). These aggregates can be recovered as virulent V. cholerae cells by inoculation into rabbit ileal loops (7).

It has been shown that V. cholerae cells in biofilm communities are more resistant to environmental stresses and protozoan predation (11, 12, 13, 18, 31). The V. cholerae rugose colonial morphology variant initially described by White (27) has been shown to produces more exopolysaccharide and biofilm than the smooth colonial variant (28). Furthermore, the rugose variant has been demonstrated to be more resistant to chlorinated water (20, 21, 28) and osmotic and oxidative stresses than the smooth variant (26, 28).

The rugose colonial morphology has been demonstrated to be a highly multifactorial phenotype subject to complex regulatory mechanisms. The genes responsible for exopolysaccharide biosynthesis (vps) are clustered in two operons in which vpsA and vpsL are the first genes of operons I and II, respectively (28). Regulation of vps genes involves cyclic diguanylate signaling (16, 17, 25), the positive regulators VpsT (3) and VpsR (29), and the negative regulator CytR (10). In some El Tor biotype strains, the quorum-sensing regulator HapR negatively affects biofilm formation and rugosity by repressing the expression of vps genes (9, 30, 31). As a result, hapR mutants of these strains exhibit enhanced biofilm formation and rugose colonial morphology. In addition, a flagellum-dependent vps signaling cascade has been reported in some El Tor biotype strain (14). Finally, a third vps signaling pathway initiated by nutrient starvation has been hypothesized for strain N16961; the absence of hapR and flaA genes in this strain does not produce rugose colonies (14).

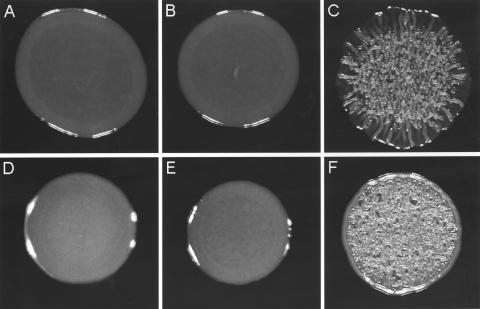

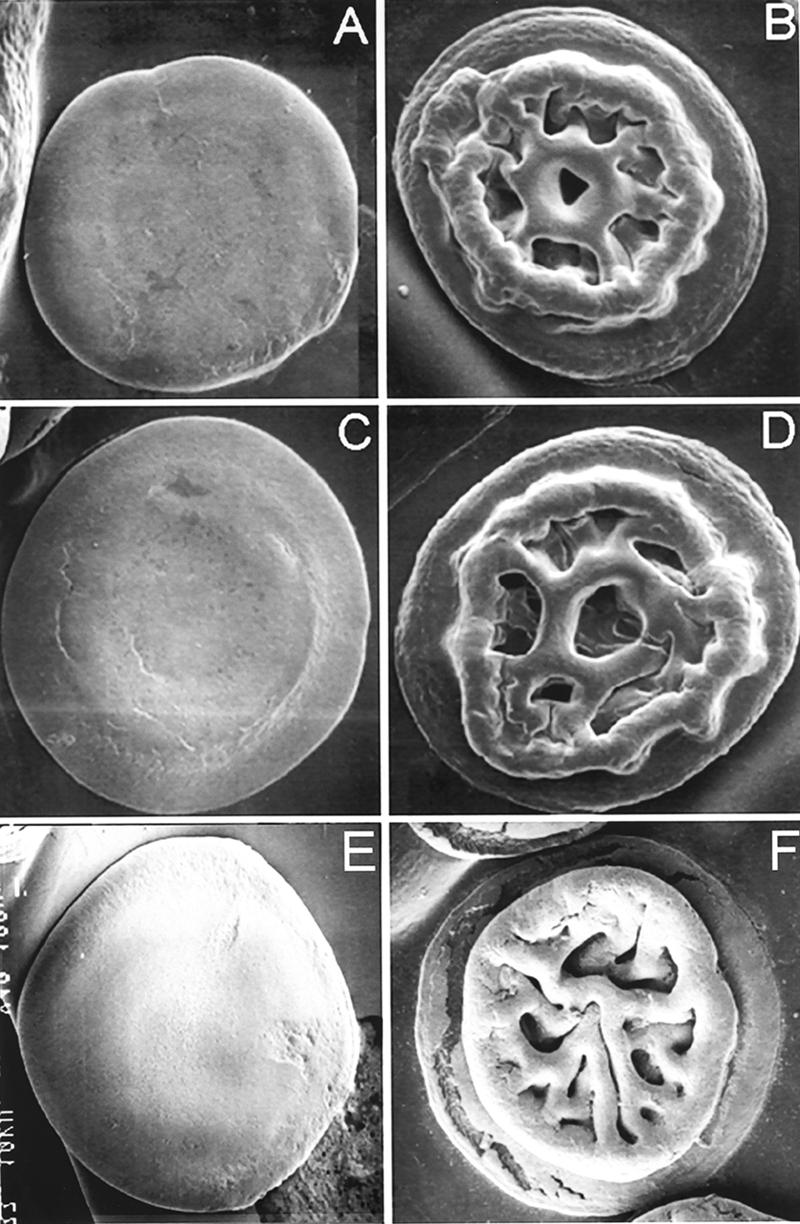

We have shown that the cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein (CRP) is required for the expression of cholera autoinducer I (15). Accordingly, deletion of crp in V. cholerae C7258 (El Tor, Ogawa, 1991 Perú isolate) resulted in very low expression of the quorum-sensing regulator HapR (15, 23). The V. cholerae Δcrp mutant expressed elevated vpsA, vpsL, and biofilm compared to the wild type (15). However, although the Δcrp mutant expressed extremely low levels of hapR mRNA, it produced less vpsA and vpsL mRNA compared to an isogenic rugose ΔhapR mutant and displayed smooth colonial morphology. These results suggested that CRP could be required for the expression of other factors required for maximal exopolysaccharide biosynthesis. In this study we address the relationship between CRP, HapR, and colonial morphology. To this end, we constructed isogenic Δcrp, ΔhapR, and ΔhapR Δcrp deletion mutants in the genetic background of the smooth strain C7258. The construction of these mutants (Table 1) has been described previously (15). We prepared colonies from LB agar plates for scanning electron microscopy as described earlier (28). As shown in Fig. 1A, the Δcrp mutant exhibited smooth colonial morphology, while the ΔhapR mutant AJB51 (Fig. 1B) was rugose. Furthermore, deletion of crp from the rugose ΔhapR mutant yielded a smooth ΔhapR Δcrp double mutant (Fig. 1C). This result is consistent with the finding that Δcrp and ΔhapR Δcrp mutants expressed less vpsA and vpsL than the isogenic ΔhapR mutant did (15). To confirm that the smooth colony morphology of strain WL51 (ΔhapR Δcrp) was due to deletion of crp, we restored the active crp allele by transformation with pBADCRP7 (Table 1). The transformant exhibited the rugose colonial morphology of the ΔhapR single mutant (Fig. 1D). Since the activity of CRP is determined by intracellular cAMP levels (4), we constructed a ΔhapR Δcya double mutant lacking adenylate cyclase. To this end, chromosomal DNA flanking the cya gene was amplified using primer pairs Cya7/Cya902 and Cya1759/Cya2567. These fragments and a Kmr gene from pUC4K (GenBank accession no. X06404) were sequentially cloned in pUC19 to yield pΔCya-Km (Table 1). The cya deletion/insertion was transferred to pCVD442 (5) and propagated in the permissive Escherichia coli strain SM10λpir (19). The resulting suicide vector pCVDΔCya-Km (Table 1) was transferred to strain AJB51 by conjugation, and the ΔhapR Δcya mutant WL52 was obtained by sucrose selection as described previously (15). We show that, similar to the ΔhapR Δcrp mutant, the ΔhapR Δcya double mutant exhibited smooth colonial morphology (Fig. 1E). For complementation, the cya open reading frame (ORF) was amplified using primers Cya7 and Cya2567 and cloned in the expression vector pTTQ18 (24) to yield pTT-Cya (Table 1). Transformation of the ΔhapR Δcya strain with plasmid pTT-Cya expressing cya from the Tac promoter restored the rugose colonial phenotype even without the addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Fig. 1F). These results clearly establish a role for the cAMP-CRP complex in regulating V. cholerae colonial variation.

TABLE 1.

Strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Description or sequence |

|---|---|

| Strains | |

| C7258 | Wild type, El Tor biotype (Perú isolate, 1991) |

| WL7258 | C7258 Δcrp (15) |

| AJB51 | C7258 ΔhapR (15) |

| WL51 | C7258 ΔhapR Δcrp (15) |

| WL52 | C7258 ΔhapR Δcya (this study) |

| Plasmids | |

| pTTVpsR | 1.4-kb BamHI-EcoRI DNA fragment encoding vpsR ORF in pTTQ18 |

| pBADCRP7 | crp ORF cloned in pBADHisB (23) |

| pCya1 | 0.9-kb EcoRI-BamHI DNA fragment 5′ of cya ORF in pUC19 |

| pCya2 | 0.8-kb BamHI-XbaI DNA fragment 3′ of cya ORF in pUC19 |

| pΔCya | EcoRI-BamHI and BamHI-XbaI fragments from pCya1 and pCya2 in pUC19 |

| pΔCya-Km | 1.2-kb BamHI Kmr cassette from pUC4K cloned in pΔCya |

| pCVDΔCya-Km | 2.9-kb EcoRI/Klenow-XbaI fragment from pΔCya-Km in pCVD442 |

| pTT-Cya | Cya ORF in pTTQ18 |

| Primers | |

| CytR295 | 5′-CAACAGAAGCGTCGGGAGAACTC |

| CytR421 | 5′-CGCAAATTCACACGCCATCACCAT |

| Cya7 | 5′-CGGAATTCCTTGCAGGCTTATACTCAG |

| Cya902 | 5′-CGGGATCCAGTCCATGCCGTACAGAT |

| Cya1759 | 5′-CGGGATCCTGGTGCTGAGCAGAAATG |

| Cya2567 | 5′-GCTCTAGAGATTTAGAAAACCTGAGACG |

| RecA578 | 5′-GTGCTGTGGATGTCATCGTTGTTG |

| RecA863 | 5′-CCACCACTTCTTCGCCTTCTTTGA |

| VpsA434 | 5′-ACCACTTTGCACCTACAGATACTTC |

| VpsA676 | 5′-CGGTAGTGATCAGCGCTTGGCAA |

| VpsL607 | 5′-ACTGGGCAGGTGCAAAATGTCTATA |

| VpsL775 | 5′-AGGGGGTATCAAAAATGCTAAACGC |

| VpsR75 | 5′-GGCTGTGTTGGAAAAAGTGGGTTG |

| VpsR206 | 5′-GGCTACTCACCAAATTCGCAATCC |

| VpsR78 | 5′-GCGAATTCCATGAGCACTCAATTCCGTA |

| VpsR1431 | 5′-GCGGATCCCAAGGTAAATCAGCAAAAC |

| VpsT56 | 5′-CCAGATTGTTGAAAGAGGCGTTAG |

| VpsT252 | 5′-TGCGGACAGTTTATGATGACCTCT |

FIG. 1.

Scanning electron microscopy of Δcrp, Δcya, and ΔhapR colonies. (A) Strain WL7258 (Δcrp); (B) strain AJB51 (ΔhapR); (C) strain WL51 (ΔhapR Δcrp); (D) WL51 transformed with pBADCRP7; (E) WL52 (ΔhapR Δcya); (F) WL52 (ΔhapR Δcya) transformed with pTT-Cya. Strains were streaked onto LB agar, and colonies were allowed to develop at 30°C for 24 h. Expression of crp was induced by the addition of 0.02% l-arabinose. Scanning electron microscopy was performed with a magnification of ×50.

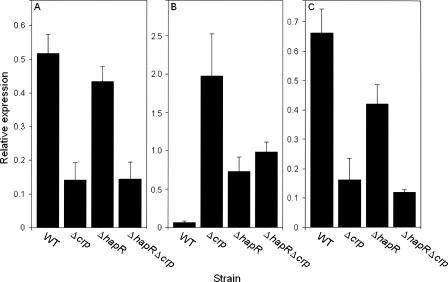

We first considered the possibility of cAMP-CRP directly interacting with the vpsA and vpsL promoters. However, analysis of the DNA sequence located upstream of vpsA and vpsL using the Virtual Footprint software program (http://www.prodoric.de/vfp) did not reveal any cAMP-CRP binding site. Therefore, we hypothesized that cAMP-CRP modulation of vpsA and vpsL is due to cAMP-CRP modulation of HapR and other factors required for maximal expression of vps genes. To investigate the mechanisms by which cAMP-CRP affects colonial morphology, we measured the expression of several regulators of vps gene expression in ΔhapR and Δcrp single and double mutants using quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). Because it is well established that hapR is expressed and functions in cells at a high cell density (9, 31), V. cholerae strains were grown in LB at 37°C, and cells were collected at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.5. Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen Laboratories) combined with DNase treatment on column and qRT-PCR conducted using the iScript two-step RT-PCR kit with SYBR green (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Relative expression values (R) were calculated using the equation R = 2−(ΔCT target − ΔCT reference) where CT is the fractional threshold cycle and recA mRNA was used as internal reference. Gene-specific primers for cytR, vpsT, and vpsR used in this analysis are listed in Table 1. The Δcrp mutant expressed reduced levels of CytR, a repressor of biofilm formation (10) (Fig. 2A). Analysis of the DNA sequence located upstream of the cytR ORF using the Virtual Footprint software program revealed the presence of two sites closely matching the TGTGAN6TCANA cAMP-CRP consensus binding sites. This result suggests that cAMP-CRP could act directly at the cytR promoter to activate its transcription. The cytR promoter contains a putative binding site for HapR, and it has been suggested that HapR activates cytR (30). However, cytR mRNA levels were unaffected by the deletion of hapR under our experimental conditions (Fig. 2A). This discrepancy could be due to the use of different strains and to the fact that in our study, RNA was extracted from cells grown to a higher cell density (OD600 of 1.5). In the preceding study, cells were harvested at a different physiological stage (OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4) (30). This difference would be expected to impact the expression and activity of HapR and CRP, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Expression of regulators of rugose colonial morphology in V. cholerae ΔhapR and Δcrp mutants. Strains C7258 (wild type [WT]), AJB51 (ΔhapR), WL7258 (Δcrp), and WL51 (ΔhapR Δcrp) were grown in LB medium to an OD600 of 1.5. Abundance of mRNAs encoding cytR (A), vpsT (B), and vpsR (C) was determined by qRT-PCR. Results were normalized to recA mRNA expression. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of at least three independent cultures.

The Δcrp mutant expressed elevated vpsT (Fig. 2B), a positive regulator of rugose colonial morphology (3). However, no cAMP-CRP binding sites were found upstream of vpsT, suggesting that CRP modulates expression of this gene indirectly. Deletion of hapR resulted in elevated vpsT mRNA, suggesting that HapR represses vpsT as reported earlier (30). It is noteworthy that the deletion of crp had little effect on vpsT expression in the ΔhapR background, suggesting that the CRP modulation of VpsT could be partly due to CRP modulation of HapR.

The Δcrp mutants expressed little VpsR (Fig. 2C), which has been reported to be a strong activator of vpsA and vpsL (29). No potential cAMP-CRP binding sites could be detected upstream of the vpsR coding sequence. It has been recently reported that VpsR is a stronger activator of vps expression than VpsT (2). Thus, the lower expression of VpsR in the ΔhapR Δcrp mutant could explain why inactivation of CRP in the ΔhapR background tends to diminish expression of vpsA and vpsL and convert the rugose ΔhapR mutant to the smooth form. This interpretation is in agreement with the finding that ΔhapR ΔvpsR double mutants display smooth colonial morphology (2). We have observed that the deletion of crp in the ΔhapR background has a more pronounced effect on vpsL, which contains a putative VpsR binding motif (30). It is noteworthy that the deletion of crp diminished VpsR expression in both the wild-type and ΔhapR backgrounds, but a negative effect on vpsA and vpsL expression was observed only in the ΔhapR background. We propose that the down-regulation of HapR and CytR and overexpression of VpsT in the Δcrp mutant partly compensates for reduced expression of VpsR resulting in a discrete increase in vps expression that is not big enough to switch the colonial morphology to rugose. We did not observe repression of vpsR by HapR in our study (Fig. 2C). In fact, the ΔhapR mutant expressed slightly less VpsR (Fig. 2C). These results contrast with a previous report suggesting that HapR represses VpsR in a different strain (2, 30). Strain differences and the cell density of cultures could be responsible for these discrepancies. Occurrence of strain variation is further suggested by the fact that no repression of VpsR by HapR was observed in mutants derived from strain C6706 of the El Tor biotype (9).

Since deletion of crp resulted in significantly lower vpsR expression in the ΔhapR background (Fig. 2C), we considered the possibility of low vpsR expression being responsible for the smooth colonial morphology of ΔhapR Δcrp and ΔhapR Δcya mutants. To test this hypothesis, we used primers VpsR78 and VpsR1431 to clone vpsR in plasmid pTTQ18 (24). The resulting plasmid, pTTVpsR (Table 1), expresses VpsR under the control of the inducible Tac promoter. Expression of VpsR from a heterologous promoter restored colonial rugosity to ΔhapR Δcrp and ΔhapR Δcya double mutants (Fig. 3C and F).

FIG. 3.

Spot colonial morphology of Δcrp and Δcya mutants expressing VpsR. Overnight cultures of strain WL51 (ΔhapR Δcrp) and WL52 (ΔhapR Δcya) were diluted 1:200, and 2 μl of each dilution was spotted onto LB agar containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin as required. (A) Strain WL51 with empty vector pTTQ18; (B) WL51 with pTTVpsR; (C) WL51 with pTTVpsR induced with 10 mM IPTG; (D) strain WL52 with empty vector pTTQ18; (E) WL52 with pTTVpsR; (F) WL52 with pTTVpsR induced with 10 mM IPTG. Plates were incubated for 24 h at 30°C, and colonies were photographed with a Canon EOS camera with a 60-mm macro lens.

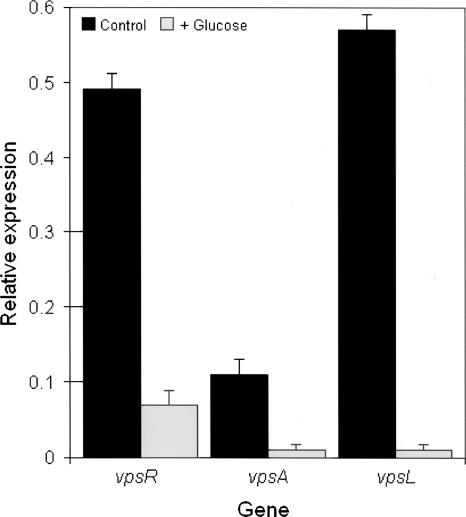

CRP plays a key role in carbon catabolite repression, a process by which the presence of a favorable carbon source (i.e., glucose, fructose, or sucrose) in the medium inhibits gene expression and/or activity of enzymes involved in the catabolism of other carbon sources (4). We have observed that the addition of 5% glucose to LB agar but not glycerol inhibited expression of rugose colonial morphology in the ΔhapR mutant AJB51 (data not shown). We hypothesized that lowering intracellular cAMP levels by the addition of glucose should abolish expression of rugose morphology by reducing VpsR expression. To test this hypothesis, we extracted RNA from cells grown with and without 5% glucose and performed qRT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 4, glucose significantly diminished expression of vpsR. We used primer pairs VpsA434/VpsA676 and VpsL607/VpsL775 and qRT-PCR to determine the expression of the vpsA and vpsL genes, which are located downstream of vpsR. As expected, glucose repression of VpsR was reflected in significantly reduced expression of vpsA and vpsL (Fig. 4). These results further confirm a role for cAMP and CRP in the modulation of V. cholerae colonial morphology phase. The inhibition of the rugose colonial morphology by sugars has been previously reported (1). Our results suggest that carbon catabolite repression participates among other factors in the regulation of exopolysaccharide biosynthesis.

FIG. 4.

Repression of VpsR by glucose. Strain WL51 (ΔhapR) was grown in LB (control) and LB supplemented with 5% glucose. Expression of vpsR, vpsA, and vpsL was determined by qRT-PCR. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of at least three independent cultures.

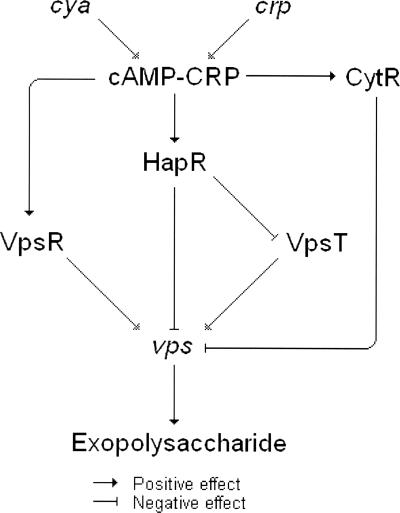

Our results add new information to the highly complex regulatory circuitry controlling exopolysaccharide biosynthesis and colonial rugosity in V. cholerae. In Fig. 5, we propose a model for the regulatory input of cAMP-CRP in exopolysaccharide biosynthesis and rugose colonial morphology. Deletion of crp results in diminished expression of the positive regulator VpsR, which is required for expression of rugose colonial morphology (Fig. 2C). However, this event is partially compensated for by reduced expression of the negative regulators HapR (15) and CytR (Fig. 2A) and overexpression of VpsT (Fig. 2B). As a result, Δcrp mutants express elevated vpsA and vpsL than the wild type does (15), but this increase is not big enough to induce rugose colonial morphology. The reduced motility of Δcrp mutants could be a second mechanism compensating for the reduced expression of VpsR. We have shown that the Δcrp mutant WL7258 is less motile than the wild type and expresses reduced FlaA (15). Inactivation of flaA has been reported to enhance the expression of vps genes (14). According to our model, maximal expression of vps genes resulting in rugose colonial morphology occurs when the vps repressor HapR is eliminated by mutation, but cAMP-CRP is available to induce the positive regulator VpsR. Further studies are required to understand how cAMP-CRP regulates VpsR. We considered the possibility that cAMP-CRP modulates the expression of GGDEF and EAL domain proteins that regulate VpsR by controlling intracellular levels of cyclic diguanylate (16, 17). However, we have not found any effect of deleting crp on the transcription of genes cdgA, mbaA, and cgdC encoding GGDEF/EAL domain proteins (data not shown). These results do not rule out the possibility of cAMP-CRP influencing cyclic diguanylate levels by affecting the activity of the above proteins or modulating other GGDEF/EAL domain proteins. VpsR has been reported to be a σ54-dependent activator (29). Interestingly, gene expression profiling of strain WL7258 revealed down-regulation of multiple σ54-dependent genes affecting motility and C4-dicarboxylate transport (15).

FIG. 5.

Model for the regulatory input of cya and crp in exopolysaccharide biosynthesis and rugose colonial morphology.

Our results clearly establish cAMP-CRP as a regulator of exopolysaccharide biosynthesis and rugose colonial morphology. The recognition of the role of cAMP-CRP in this process will facilitate further studies to determine how environmental cues influencing intracellular cAMP levels (i.e., carbon starvation) affect the ability of V. cholerae to adopt the rugose colonial morphology variant and resist environmental stresses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by PHS grants RO1AI063187 and 2S06GM008248-20 from the National Institutes of Health to J.A.B. and A.J.S., respectively.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali, A., J. G. Morris, Jr., and J. A. Johnson. 2005. Sugars inhibit the expression of the rugose phenotype of Vibrio cholerae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1426-1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyhan, S., K. Bilecen, S. R. Salama, C. Casper-Lindley, and F. H. Yildiz. 2007. Regulation of rugosity and biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae: comparison of the VpsT and VpsR regulons and epistasis analysis of vpsT, vpsR, and hapR. J. Bacteriol. 189:388-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casper-Lindley, C., and F. H. Yildiz. 2004. VpsT is a transcriptional regulator required for expression of vps biosynthesis genes and the development of rugose colonial morphology in Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. J. Bacteriol. 186:1574-1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deutscher, J., C. Francke, and P. W. Postma. 2006. How phosphotransferase system-related protein phosphorylation regulates carbohydrate metabolism in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70:939-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donnenberg, M. S., and J. B. Kaper. 1991. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive selection suicide vector. Infect. Immun. 59:4310-4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faruque, S. M., and G. B. Nair. 2002. Molecular ecology of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae. Microbiol. Immunol. 46:59-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faruque, S. M., K. Biswas, S. M. Nashir Udden, Q. S. Ahmad, D. A. Sack, G. B. Nair, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2006. Transmissibility of cholera: in vivo-formed biofilms and their relationship to infectivity and persistence in the environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:6350-6355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faruque, S. M., M. J. Albert, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1998. Epidemiology, genetics, and ecology of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1301-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammer, B. K., and B. L. Bassler. 2003. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 50:101-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haugo, A. J., and P. I. Watnick. 2002. Vibrio cholerae CytR is a repressor of biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 45:471-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huq, A., E. B. Small, P. A. West, M. I. Huq, R. Rahman, and R. R. Colwell. 1983. Ecological relationships between Vibrio cholerae and planktonic crustacean copepods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45:275-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huq, A., P. A. West, E. B. Small, M. I. Huq, and R. R. Colwell. 1984. Influence of water temperature, salinity, and pH on survival and growth of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae serovar O1 associated with live copepods in laboratory microcosms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48:420-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joelsson, A., Z. Liu, and J. Zhu. 2006. Genetic and phenotypic diversity of quorum-sensing systems in clinical and environmental isolates of Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 74:1141-1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauriano, C. M., C. Ghosh, N. E. Correa, and K. E. Klose. 2004. The sodium-driven flagellar motor controls exopolysaccharide expression in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 186:4864-4874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang, W., A. Pascual-Montano, A. J. Silva, and J. A. Benitez. 2007. The cyclic AMP receptor protein modulates quorum sensing, motility and multiple genes that affect intestinal colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology 153:2964-2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim, B., S. Beyhan, and F. H. Yildiz. 2007. Regulation of Vibrio polysaccharide synthesis and virulence factor production by CdgC, a GGDEF-EAL domain protein, in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 189:717-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim, B., S. Beyhan, J. Meir, and F. H. Yildiz. 2006. Cyclic-diGMP signal transduction systems in Vibrio cholerae: modulation of rugosity and biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 60:331-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matz, C., D. McDougald, A. M. Moreno, P. Y. Yung, F. H. Yildiz, and S. Kjelleberg. 2005. Biofilm formation and phenotypic variation enhance predation-driven persistence of Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:16819-16824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller, V. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane protein and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 170:2575-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris, J. G., Jr., M. B. Sztein, E. W. Rice, J. P. Nataro, G. A. Losonsky, P. Panigrahi, C. O. Tacket, and J. A. Johnson. 1996. Vibrio cholerae can assume a chlorine-resistant rugose survival form that is virulent for humans. J. Infect. Dis. 174:1364-1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rice, E. W., C. J. Johnson, R. M. Clark, K. R. Fox, D. J. Reasoner, M. E. Dunnigan, P. Panigrahi, J. A. Johnson, and J. G. Morris, Jr. 1992. Chlorine and survival of “rugose” Vibrio cholerae. Lancet 340:740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schoolnik, G. K., and F. H. Yildiz. 2000. The complete genome sequence of Vibrio cholerae: a tale of two chromosomes and of two lifestyles. Genome Biol. 1:reviews1016.1-1016.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva, A. J., and J. A. Benitez. 2004. Transcriptional regulation of Vibrio cholerae hemagglutinin/protease by the cyclic AMP receptor protein and RpoS. J. Bacteriol. 186:6374-6382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starks, M. J. 1987. Multicopy expression vectors carrying the lac repressor for regulated high-level expression of genes in Escherichia coli. Gene 51:255-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tischler, A., and A. Camilli. 2004. Cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 53:857-869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wai, S. N., Y. Mizunoe, A. Takade, S. I. Kawabata, and S. I. Yoshida. 1998. Vibrio cholerae O1 strain TSI-4 produces the exopolysaccharide materials that determine colony morphology, stress resistance, and biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3648-3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White, P. B. 1938. The rugose variant of vibrios. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 46:1-6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yildiz, F. H., and G. K. Schoolnik. 1999. Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor: identification of a gene cluster required for the rugose colony type, exopolysaccharide production, chlorine resistance, and biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:4028-4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yildiz, F. H., N. A. Dolganov, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2001. VpsR, a member of the response regulators of the two-component regulatory systems, is required for expression of vps biosynthesis genes and EPS (ETr)-associated phenotypes in Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. J. Bacteriol. 183:1716-1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yildiz, F. H., X. S. Liu, A. Heydorn, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2004. Molecular analysis of rugosity in a Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor phase variant. Mol. Microbiol. 53:497-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu, J., and J. J. Mekalanos. 2003. Quorum sensing-dependent biofilms enhance colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Dev. Cell 5:647-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]