Abstract

Phenazine production by Pseudomonas fluorescens 2-79 and P. chlororaphis isolates 30-84 and PCL1391 is regulated by quorum sensing through the activator PhzR and acyl-homoserine lactones (acyl-HSLs) synthesized by PhzI. PhzI from P. fluorescens 2-79 produces five acyl-HSLs that include four 3-hydroxy species. Of these, N-(3-hydroxyhexanoyl)-HSL is the biologically relevant ligand for PhzR. The quorum-sensing systems of P. chlororaphis strains 30-84 and PCL1391 have been reported to produce and respond to N-(hexanoyl)-HSL. These differences were of interest since PhzI and PhzR of strain 2-79 share almost 90% sequence identity with orthologs from strains 30-84 and PCL1391. In this study, as assessed by thin-layer chromatography, the three strains produce almost identical complements of acyl-HSLs. The major species produced by P. chlororaphis 30-84 were identified by mass spectrometry as 3-OH-acyl-HSLs with chain lengths of 6, 8, and 10 carbons. Heterologous bacteria expressing cloned phzI from strain 30-84 produced the four 3-OH acyl-HSLs in amounts similar to those seen for the wild type. Strain 30-84, but not strain 2-79, also produced N-(butanoyl)-HSL. A second acyl-HSL synthase of strain 30-84, CsaI, is responsible for the synthesis of this short-chain signal. Strain 30-84 accumulated N-(3-OH-hexanoyl)-HSL to the highest levels, more than 100-fold greater than that of N-(hexanoyl)-HSL. In titration assays, PhzR30-84 responded to both N-(3-OH-hexanoyl)- and N-(hexanoyl)-HSL with equal sensitivities. However, only the 3-OH-hexanoyl signal is produced by strain 30-84 at levels high enough to activate PhzR. We conclude that strains 2-79, 30-84, and PCL1391 use N-(3-OH-hexanoyl)-HSL to activate PhzR.

Phenazines belong to a class of heterocyclic, pigmented metabolites produced by select members of the genera Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, and Streptomyces (36). Several such compounds, including phenazine-1-carboxylic acid (PCA) and its derivatives, which are produced by root-associated, fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. (6, 8, 9, 35), exhibit antibiotic activity against a variety of prokaryotic and eukaryotic microbes. The antimicrobial activity associated with phenazines is important for the producer bacteria, providing them with a competitive advantage in the microenvironment they share with other members of the soil microbiota (22, 27). These metabolites also provide biological protection to plants by targeting pathogenic microorganisms. For example, the production of phenazines by P. chlororaphis (formerly P. aureofaciens) 30-84 and P. chlororaphis PCL1391 plays a key role in the efficient biocontrol of take-all disease of wheat caused by Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici and of root and foot rot of tomato caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicis-lycopersici (1, 6, 8, 27, 35).

Phenazines are products of secondary metabolism and are derived from amino acid anabolism pathways (20, 29, 36). Synthesis of PCA in P. chlororaphis strains 30-84 and PCL1391 and P. fluorescens 2-79, which is a close relative of strain 30-84, is catalyzed by the products of the phz genes. The core members of phz genes are arranged in a single operon (8, 20, 21, 29) that is strongly conserved in terms of organization and sequence in all phenazine-producing Pseudomonas spp. studied to date (20).

Phenazine production by P. chlororaphis 30-84, P. chlororaphis PCL1391, and P. fluorescens 2-79 is controlled by quorum sensing via the transcriptional regulator PhzR (7, 13, 28, 41). This activator is a member of the LuxR family of transcriptional regulators and requires acyl-homoserine lactone (acyl-HSL) signals for its activation. The signals in phenazine-producing pseudomonads are synthesized in turn by the acyl-HSL synthase PhzI, a LuxI homologue (7, 20, 40). phzR and phzI are located immediately upstream of the phz operon, and the sequences and arrangement of these genes in the three pseudomonads are strongly conserved.

At the molecular level, the initiation of transcription of the phz operon by PhzR depends upon the availability and nature of the acyl-HSL signals which accumulate in the environment as a function of an increase in population size. At a particular population density, the overall concentration of the signal, both extra- and intracellular, reaches a threshold level and is bound by and activates PhzR. Activated PhzR positively regulates the phz operon, triggering the onset of PCA production (13, 28). PhzR also activates phzI, resulting in a positive feedback loop leading to an accelerated production of acyl-HSL signals and a concomitant rapid increase in the expression of the phz genes.

Pseudomonas fluorescens 2-79 synthesizes a suite of six signals composed of four 3-hydroxy derivatives, N-(3-hydroxyhexanoyl)-l-HSL (3-OH-C6-HSL), N-(3-hydroxyheptanoyl)-l-HSL (3-OH-C7-HSL), N-(3-hydroxyoctanoyl)-l-HSL (3-OH-C8-HSL), and N-(3-hydroxydecanoyl)-l-HSL (3-OH-C10-HSL), and two alkanoyl-acyl-HSLs, N-(hexanoyl)-l-HSL (C6-HSL) and N-(octanoyl)-l-HSL (C8-HSL) (4, 13, 32). PhzI is responsible for the synthesis of all six acyl-HSLs produced by strain 2-79 (13). Of these, 3-OH-C6-HSL is produced at the highest levels and also is, by an order of magnitude, the most potent signal for the activation of PhzR of strain 2-79 (13).

On the other hand, P. chlororaphis 30-84 and P. chlororaphis PCL1391 have been reported to produce C6-HSL as their dominant signal (7, 41). Similarly, unlike PhzR of strain 2-79, PhzR of strains 30-84 and PCL1391 have been reported to recognize C6-HSL as the activating signal (7, 41). These differences in signal production and signal perception were puzzling given the high sequence similarity between the PhzI and PhzR proteins from the three bacteria (13).

In the present communication we have reexamined acyl-HSL production by strains 30-84 and PCL1391 and compared the suite of signals produced by these bacteria with that of strain 2-79. We have compared the signal sensitivity of PhzR from strain 30-84 to that of PhzR from strain 2-79 and have determined the specificity of each PhzR protein for activating its cognate phz operon promoter. Finally, we have characterized the acyl-HSLs produced by CsaI, a second acyl-HSL synthase present in isolate 30-84, and assessed the influence of these signals on the PhzR-mediated activation of the phz operon.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. All strains of Escherichia coli were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C unless stated otherwise. Pseudomonas sp. strains 2-79, 30-84, PCL1391, and 1855-344 were grown in King's medium B (14), ABM minimal medium (5), or LB medium at 28°C. The bioreporter strains, Agrobacterium tumefaciens NTL4(pZLR4) (4) and Chromobacterium violaceum CV026blu (23), were grown at 28°C in ABM and LB media, respectively. When required, antibiotics were added to final concentrations, in μg per ml, of 100 or 200 (ampicillin or carbenicillin), 100 (streptomycin or spectinomycin), 50 (kanamycin), 75 (rifampin), and 12.5 or 25 (tetracycline).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| P. chlororaphis | ||

| 30-84 | Phz+ Rifr wild-type strain | Linda Thomashawa |

| PCL1391 | Phz+ wild-type strain | E. J. J. Lugtenbergb |

| P. fluorescens | ||

| 2-79 | Phz+ Rifr wild-type strain | Linda Thomashaw |

| 1855-344 | Wild-type strain lacking any known homologues of luxR and luxI | 4 |

| 1855(pSF105)(pSF107) | 2-79 reporter strain | 13 |

| 1855(pSF110)(pSF116) | 30-84 reporter strain | This study |

| A. tumefaciens NTL4(pZLR4) | Indicator strain for detection of hydroxy-acyl-HSLs | 4 |

| C. violaceum CV026blu | Indicator strain for detection of alkanoyl-acyl-HSLs | 23 |

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F−recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 φ80lacZΔM15 | Invitrogen |

| BL21(DE3) | F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) | Novagen |

| S17-1 | Pro− Res− Mod+recA; integrated RP4-Tet::Mu-Kan::Tn7; Mob+ | 33 |

| SF114 | BL21(DE3) containing pSF114 | This study |

| SF117 | BL21(DE3) containing pSF106-1 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript II SK | Co1E1 f1(+) Ampr; cloning vector | Stratagene |

| pZLQ | Kmr; pBBR1MCS-2-derived expression vector containing trc promoter and lacIq | 18 |

| pDLB4 | Kmr; pBBR1MCS-2-derived expression vector containing the BAD promoter of pBAD22 | 16 |

| pET14b | Ampr; T7 promoter-based expression vector | Novagen |

| pET17b | Ampr; T7 promoter-based expression vector | Novagen |

| pRG970b | Broad-host-range promoter selection vector; Strr/Carbr | 37 |

| pLSP259 | pLAFR3 containing a 21-kb EcoRI fragment from P. chlororaphis 30-84 coding for phzR and phzI | Linda Thomashaw |

| pSF105 | pZLQ containing a 0.7-kb BamHI-NdeI fragment of P. fluorescens 2-79 containing phzR | 13 |

| pSF106 | pDLB4 containing phzI of P. fluorescens 2-79 at EcoRI-HindIII sites | 13 |

| pSF106-1 | pET14b containing phzI of P. fluorescens 2-79 at NdeI-BamHI sites | This study |

| pSF107 | pRG970b containing 0.38-kb phzR-phzA intergenic region of P. fluorescens 2-79 at SmaI-BamHI sites | 13 |

| pSF109 | PCR-amplified 0.7-kb phzR gene of P. chlororaphis 30-84 cloned at the BamHI site of pBluescript II SK | This study |

| pSF110 | pZLQ containing a 0.7-kb BamHI-NdeI fragment of P. chlororaphis 30-84 containing phzR | This study |

| pSF111 | pDLB4 containing phzI of P. chlororaphis 30-84 at EcoRI-HindIII sites | This study |

| pSF112 | 1.7-kb BglII fragment of pLSP259 cloned at BamHI site of pBluescript II SK | This study |

| pSF113 | pBluescript II SK containing csaI of P. chlororaphis 30-84 at EcoRI-BamHI sites | This study |

| pSF114 | pET17b containing csaI of P. chlororaphis 30-84 at NdeI-BamHI sites | This study |

| pSF115 | pBluescript II SK containing 0.43-kb P. chlororaphis 30-84 phzR-phzX intergenic region | This study |

| pSF116 | pRG970b containing 0.43-kb phzR-phzX intergenic region of P. chlororaphis 30-84 at SmaI-BamHI sites | This study |

USDA-ARS, Department of Plant Pathology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164.

Institute of Molecular Plant Sciences, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands.

DNA manipulations and analysis.

Standard methods were used for plasmid DNA isolation, restriction enzyme digestion, agarose gel electrophoresis, ligation, and transformation (2). Plasmids were introduced into P. fluorescens isolates by electroporation or by mobilization using E. coli strain S17-1 (Table 1) as the donor.

Plasmid constructions.

The coding sequence of phzR of strain 30-84 was amplified by PCR using pLSP259 (27) as the template and cloned in pBluescript II SK (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to give plasmid pSF109. For confirmation of the sequence of phzR30-84, a 1.7-kb BglII fragment of the insert in cosmid clone pLSP259 was subcloned at the BamHI site into pBluescript II SK, yielding pSF112. The nucleotide sequence of the cloned PCR fragment was identical to that of the cloned native fragment. The phzR gene was excised from pSF109 and cloned between the NdeI and BamHI sites (sites were generated during PCR amplification) in the broad-host-range expression vector pZLQ (18), yielding pSF110. In this plasmid, which also codes for lacIq, phzR is under the control of the IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside)-inducible trc promoter. The phzI amplicon was generated by PCR using cosmid pLSP259 as the template and cloned into pDLB4 (16) between EcoRI and HindIII sites to give pSF111. In this vector, phzI is under the control of PBAD, and its expression is inducible with arabinose (16). Clones of phzI2-79 and phzR2-79 in pZLQ and pDLB4 have been described previously (13). The phzI gene from strain 2-79 was placed downstream of the T7 promoter of pET14b by cloning a PCR-generated fragment between the NdeI and BamHI sites. This construct, pSF106-1, was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen), giving rise to SF117. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis.

The second acyl-HSL synthase gene from strain 30-84, csaI, was amplified by PCR using total genomic DNA as the template and cloned in pBluescript II SK between EcoRI and BamHI sites, generating pSF113. Subsequently, csaI was excised from pSF113 by digestion with NdeI and BamHI (the NdeI site was generated internal to EcoRI as part of the primer) and ligated into pET17b (Novagen) to yield pSF114. In this vector, csaI is under the control of the T7 promoter, and its expression is inducible with IPTG.

The PhzR-dependent phzX promoter-reporter from strain 30-84 was constructed in a manner similar to that described previously for the promoter-reporter from strain 2-79 (13). Briefly, the 430-bp intergenic region between the divergently oriented phzR and phzX genes of strain 30-84 was amplified by PCR and cloned into pBluescript II SK between EcoRI and BamHI sites, producing pSF115. This divergent promoter region was excised from pSF115 as a BamHI-SmaI fragment and ligated into the promoter selection vector pRG970b (37) (Table 1), yielding pSF116. In this construct, transcription towards phzX drives the expression of lacZ, while transcription towards phzR drives the expression of uidA.

Nucleotide sequencing.

DNA sequencing was performed on an ABI model 3730xl sequencer (Applied Biosystems), and sequence analyses were done using SeqApp 1.9 and DNA Strider 1.2.1 software or by using Biology WorkBench (San Diego Supercomputer Center).

Extraction of acyl-HSLs from culture supernatants.

Strains 30-84, 2-79, and PCL1391 were grown in King's medium B for 48 h at 28°C with shaking. Strains of E. coli and P. fluorescens strain 1855-344 expressing the arabinose-inducible phzI genes of 2-79 and 30-84 were grown in LB and in King's medium B, respectively, to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4. The expression of the acyl-HSL synthase in these cultures was induced by the addition of arabinose to a final concentration of 0.3%, and incubation was continued for another 15 h at 28°C. For the expression of CsaI in E. coli, strain SF114 was grown in LB medium to an OD600 of 0.5 and induced with IPTG (final concentration, 1 mM) for 4 to 8 h. Following growth, the bacterial cells were removed by centrifugation (5,000 × g, 10 min) and culture supernatants were extracted twice with equal volumes of ethyl acetate or dichloromethane. The extracted organic phases were pooled, residual water was removed by addition of anhydrous sodium sulfate, and the extracts were taken to dryness under vacuum. For thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis, the dried residues were redissolved in volumes of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade ethyl acetate or dichloromethane sufficient to yield concentration factors of 100 to 1,000.

For analyses by HPLC and mass spectrometry (MS), cultures of P. fluorescens 1855-344 and E. coli DH5α harboring pSF111 (pDLB4-phzI30-84) were grown in LB at 28°C and 37°C, respectively, to an OD600 of 0.5. Expression of the protein was induced by the addition of 0.2% arabinose, and growth was continued with shaking for another 8 h. Cultures of E. coli expressing PhzI2-79 or CsaI30-84 were grown at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.5, and expression of the protein was induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG for 8 h. Upon completion of the incubations, cells were removed by centrifugation and culture supernatants were passed through a 0.2-μm filter. Four hundred picomoles of deuterated C6-HSL (D3-C6-HSL) was added to 10 ml of each culture supernatant as an internal standard, and the acyl-HSLs from the culture supernatants were extracted with 10-ml volumes of ethyl acetate acidified with 0.1 ml of acetic acid per liter.

TLC separation and visualization of acyl-HSLs.

Two- to 10-μl volumes of the organic extracts to be analyzed were applied to C18 reversed-phase TLC plates and developed in methanol:water (70:30 [vol/vol]) as described previously (32). The plates were dried, overlaid with appropriate indicator strains, incubated, and examined as described previously (4, 10, 13, 32). One indicator strain, A. tumefaciens NTL4(pZLR4), responds strongly to 3-oxo- and 3-OH-substituted HSLs by producing blue spots, while the other, Chromobacterium violaceum CV026blu, responds only to medium-chain alkanoyl-HSLs by producing purple pigment (4, 23, 32).

MS identification and quantitation of acyl-HSLs.

The acyl-HSLs produced by wild-type strains and by strains expressing the cloned phzI and csaI genes were identified and quantified essentially as previously described (11). Briefly, cell-free culture supernatants were extracted with ethyl acetate as described above, and the acyl-HSLs were partially purified using solid-phase extraction cartridges. The partially purified acyl-HSLs were separated and analyzed by reversed-phase HPLC using a PE Sciex API-3000 triple-quadrupole tandem MS (MS-MS) (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Thornhill, Ontario, Canada). Precursor ion scanning mode, multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode, and retention-time analyses provided the data for the identification of acyl-HSLs present in the samples. The structures of 3-hydroxy-acyl-HSLs were confirmed by comparison of MS-MS fragmentation patterns from synthetic 3-OH-C6-HSL by use of an API Q-Trap MS (11) and published data (32). Two transitions were monitored for each of the acyl-HSLs (see reference 11 for details). However, for the MRM of the 3-OH-HSLs, the transition from the precursor to the acyl moiety was monitored for the acyllium ion decreased by the mass of a water molecule, a characteristic major fragment in the MS-MS analysis of compounds with hydroxyl groups (32). Components were quantified by comparing analyte peak areas from chromatographic separations with those of a dilution series of authentic acyl-HSLs, all normalized against D3-C6-HSL added as an internal standard. To construct the standard curves, a range of alkanoyl- and 3-hydroxyl acyl-HSLs were obtained from commercial sources or synthesized as previously described (11). The acyl-HSLs used as standards were analyzed by high-resolution proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectrometry, and the analyte peaks were quantified by manual integration using trimethylsilyl propionic-2,2,3,3,-d1 acid (TMSP; 50 mM in D2O in a thin glass capillary tube) as an external standard (31).

β-Galactosidase assay.

β-Galactosidase activity was assessed qualitatively by patching cultures onto solid ABM or LB medium containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal). Colony color and intensity were visually assessed after 18 to 36 h of growth at 28°C. β-Galactosidase activity, expressed as Miller units, was quantified according to the method of Miller (24) as previously described (13).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

Our sequence for PhzR30-84 has been deposited in GenBank under accession number EF626944.

RESULTS

Pseudomonas sp. strains 2-79, 30-84, and PCL1391 produce very similar patterns of acyl-HSLs.

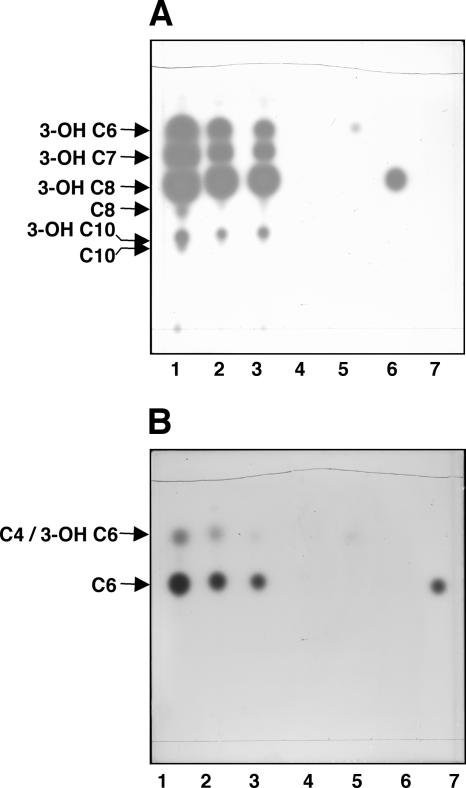

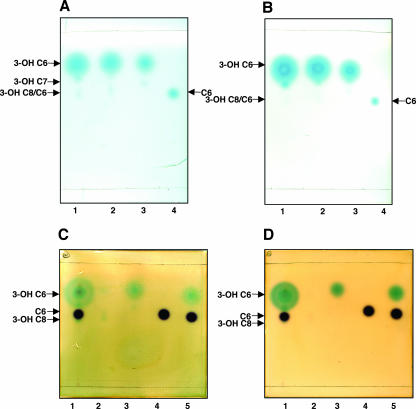

The acyl-HSL signals produced by Pseudomonas chlororaphis isolates 30-84 and PCL1391 were compared to those of strain 2-79 by use of TLC followed by detection with two acyl-HSL bioreporters, the A. tumefaciens indicator strain and the C. violaceum indicator strain.

The plate overlaid with the Agrobacterium reporter detected six activity spots in the extracts of strains 30-84 and PCL1391 (Fig. 1A, lanes 2 and 3). The spots comigrated with the suite of six acyl-HSLs, including the four 3-hydroxy species produced by strain 2-79 (Fig. 1A, lane 1). As judged by the plate overlaid with the C. violaceum indicator strain, which responds well only to medium-chain alkanoyl-HSLs, all three strains also produced a signal with the characteristic chromatographic properties of C6-HSL (Fig. 1B, lanes 1, 2, and 3). A second, fast-migrating species detected by C. violaceum in the extracts of all three strains could be either butanoyl-HSL (C4-HSL) or 3-OH-C6-HSL. Extracts of culture supernatants of strains 2-79 and 30-84 prepared using dichloromethane, as well as extracts prepared from cells grown in LB medium, gave indistinguishable results (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Pseudomonas chlororaphis 30-84 and P. chlororaphis PCL1391 produce suites of acyl-HSL signals similar to that of P. fluorescens 2-79. Ethyl acetate extracts of culture supernatants were chromatographed on C18 reversed-phase thin-layer plates, and the plates were overlaid with A. tumefaciens NTL4(pZLR4) (A) or C. violaceum CV026blu (B). Lanes 1, 2, and 3 contain extracts from Pseudomonas isolates as follows: 1, 2-79; 2, 30-84; 3, PCL1391; 4, 1855-344. Lanes 5, 6, and 7 contain authentic N-(3-OH-hexanoyl)-l-HSL, N-(3-OH-octanoyl)-l-HSL, and N-(hexanoyl)-l-HSL, respectively.

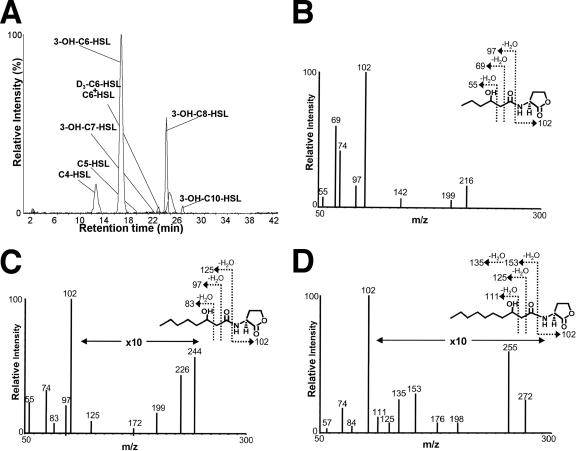

We identified the signals in extracts from culture supernatants of strains 30-84 and 2-79 by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-MS-MS (LC/MS-MS). Both extracts contained 3-OH-C6-HSL, 3-OH-C7-HSL, 3-OH-C8-HSL, and 3-OH-C10-HSL as well as small amounts of the alkanoyl signal, C6-HSL (Fig. 2; data for 2-79 not presented). An additional peak in the extracts from strain 30-84 not detected in extracts from strain 2-79 was identified as containing the alkanoyl derivative, C4-HSL (data not presented).

FIG. 2.

Pseudomonas chlororaphis strain 30-84 produces 3-hydroxy- and alkanoyl-acyl-HSLs. Extracts from cultures of strain 30-84 were prepared as described in Materials and Methods and analyzed for acyl-HSLs by LC/MS-MS as described in the text. (A) Reversed-phase chromatographic profile of the purified extract obtained from wild-type strain 30-84. Structural assignments to each peak were made by MRM, retention time analysis, and comparison to known standards. Only the transitions for the precursor [M + H]± → m/z 102 product are shown. The structures of selected 3-hydroxy-acyl-HSLs were confirmed by their fragmentation patterns in MS-MS as N-(3-OH-hexanoyl)-l-HSL (B), N-(3-OH-octanoyl)-l-HSL (C), and N-(3-OH-decanoyl)-l-HSL (D).

As determined by MRM, the 3-OH acyl-HSLs accumulated to the highest levels, with the most abundant species, 3-OH-C6-HSL, being present at a concentration more than 200-fold higher than that of C6-HSL in the extracts of the wild-type strains (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Relative amounts of acyl-HSLs produced by wild-type bacteria and by heterologous hosts expressing cloned acyl-HSL synthase genesa

| Source of extract | Relative concentrations of acyl-HSL signalsb

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxy-acyl-HSLs

|

Alkanoyl-acyl-HSLs

|

|||||||

| C6 | C7 | C8 | C10 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C8 | |

| 2-79 wild type | 61.10 | 7.10 | 23.40 | 7.50 | NDc | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.10 |

| 30-84 wild type | 64.70 | 6.60 | 22.70 | 0.70 | 4.3 | 0.30 | 0.30 | ND |

| E. coli(phzI2-79) | 60.40 | 1.70 | 33.80 | 3.50 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.10 |

| E. coli(phzI30-84) | 60.20 | 5.50 | 29.50 | 4.00 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.10 |

| 1855-344(phzI30-84) | 65.40 | 0.30 | 26.10 | 6.80 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.70 | 0.30 |

| E. coli(csaI30-84) | ND | ND | ND | ND | 97.80 | 1.70 | 0.04 | ND |

Values are the averages of two independent experiments.

Presented as percentages of the total amount of acyl-HSLs produced by the indicated strain.

ND, not detectable.

PhzI from strain 30-84 codes for synthesis of 3-OH-acyl-HSLs.

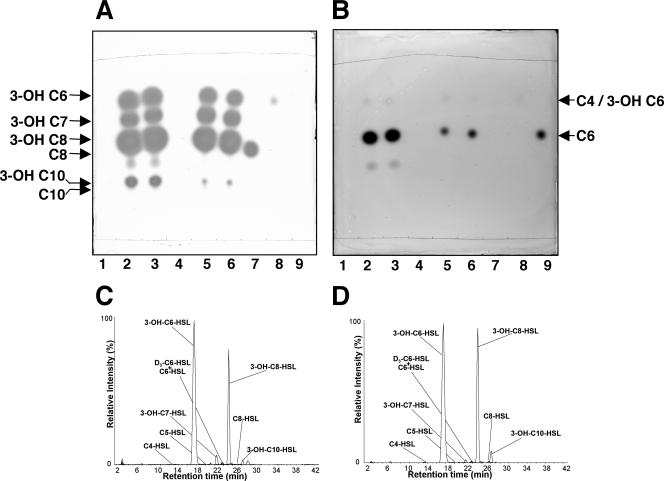

To determine which of the signals produced by strain 30-84 are synthesized by PhzI, we cloned the corresponding gene and expressed the recombinant gene in E. coli DH5α and P. fluorescens 1855-344. The recombinant PhzI from strain 30-84 catalyzed the production of a group of acyl-HSL signals qualitatively indistinguishable from those produced by PhzI of strain 2-79 in both E. coli and P. fluorescens hosts (Fig. 3A and B, lanes 2 and 3 and 5 and 6, respectively). Analysis by MRM of acyl-HSLs produced by the cloned PhzI from strains 2-79 and 30-84 confirmed the presence of the four 3-hydroxy-acyl-HSLs as well as C6-HSL and small amounts of C5- and C8-HSL (Fig. 3C and D). Clearly, as with strain 2-79 (13), PhzI of strain 30-84 confers production of 3-hydroxy-acyl-HSLs.

FIG. 3.

The phzI gene of P. chlororaphis 30-84 is responsible for production of 3-hydroxy-acyl-HSLs. Ethyl acetate extracts of culture supernatants of E. coli DH5α and P. fluorescens 1855-344 expressing phzI genes of P. chlororaphis 30-84 and P. fluorescens 2-79, together with culture supernatants of strains harboring control plasmids, were chromatographed on TLC plates, and the plates were overlaid with A. tumefaciens NTL4(pZLR4) (A) or C. violaceum CV026blu (B). Lanes 1 to 6 contain extracts from cultures as follows: 1, DH5α(pDLB4); 2, DH5α(pDLB4-2-79-phzI); 3, DH5α(pDLB4-30-84-phzI); 4, 1855-344(pDLB4); 5, 1855-344(pDLB4-2-79-phzI); 6, 1855-344(pDLB4-30-84-phzI). Lanes 7, 8, and 9 contain authentic N-(3-OH-octanoyl)-l-HSL, N-(3-OH-hexanoyl)-l-HSL, and N-(hexanoyl)-l-HSL, respectively. Signals in culture supernatants from strains of E. coli expressing cloned phzI genes from strains 30-84 (C) and 2-79 (D) were identified by LC/MS-MS in the MRM mode as described in Materials and Methods.

3-OH-C6-HSL accumulated in culture supernatants of strain 30-84 to a concentration over 200-fold higher than that of C6-HSL (Table 2). However, PhzI30-84, while catalyzing the synthesis of C6-HSL and C8-HSL and all hydroxy signals produced by strain 30-84, produced very little C4-HSL compared to the amount present in the extracts of the parent pseudomonad.

Collectively, these data indicate that the PhzI proteins from strains 2-79 and 30-84 are functionally indistinguishable (Fig. 3) and synthesize all of the hydroxy-acyl-HSLs as well as the small amounts of C5-, C6-, and C8-HSL produced by the wild-type strains (Fig. 1).

CsaI produces alkanoyl-acyl-HSLs.

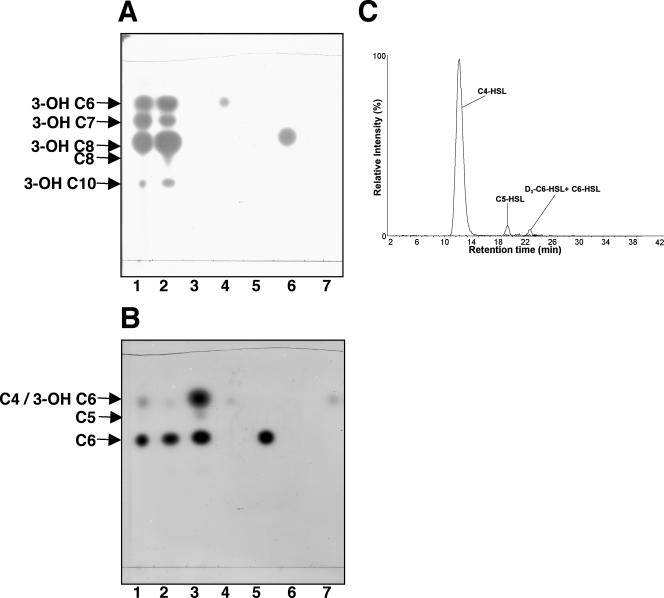

PhzI cannot account for the production of C4-HSL by strain 30-84. However, this isolate expresses a second quorum-sensing system comprised of the acyl-HSL synthase CsaI and the response regulator CsaR (44). This system is thought to regulate the cell surface properties of strain 30-84 in response to the signals produced by CsaI (19, 44). To identify the acyl-HSLs produced by csaI, we cloned and expressed the gene in E. coli.

As judged by TLC, culture extracts of E. coli strain SF114 induced for the expression of CsaI contained three active species detectable only by the Chromobacterium reporter. Two of the signals comigrated with the C6-HSL and C4-HSL standards (Fig. 4B, lanes 3, 5, and 7), while the third species migrated between the two standards. The Chromobacterium indicator strain exhibits a strong preference for C6-HSL, and the fact that the spot migrating at the position of C4-HSL was as intense as that of C6-HSL suggests that CsaI makes the short-chain signal at a concentration higher than that of the hexanoyl species.

FIG. 4.

CsaI of P. chlororaphis strain 30-84 catalyzes the synthesis of alkanoyl-acyl-HSLs. Ethyl acetate extracts of culture supernatants of E. coli expressing recombinant CsaI were subjected to TLC and the plates were overlaid with A. tumefaciens NTL4(pZLR4) (A) or C. violaceum CV026blu (B). Lanes 1, 2, and 3 contain extracts from cultures as follows: 1, wild-type strain 30-84; 2, DH5α(pDLB4-30-84-phzI); 3, BL21(DE3)(pET17b-30-84-csaI). Lanes 4, 5, 6, and 7 contain samples of authentic N-(3-OH-hexanoyl)-l-HSL, N-(hexanoyl)-l-HSL, N-(3-OH-octanoyl)-l-HSL, and N-(butanoyl)-l-HSL, respectively. The structures of the acyl-HSLs produced by CsaI in E. coli were confirmed by MRM (C).

Consistent with the qualitative profile shown in the TLC experiments, the expression of CsaI in E. coli resulted in the production of three alkanoyl signals identified by HPLC-MS as C4-, C5-, and C6-HSL (Fig. 4C). The C4-HSL species was produced at concentrations almost 300- and 60-fold higher than seen for C6-HSL and C5-HSL, respectively (Table 2). Taken together, our results show that PhzI catalyzes the synthesis of hydroxy-acyl-HSLs, whereas CsaI is responsible for the synthesis of C4-HSL. However, both PhzI and CsaI contribute to the total pool of C6-HSL produced by strain 30-84.

Cloning and sequence determination of PhzR.

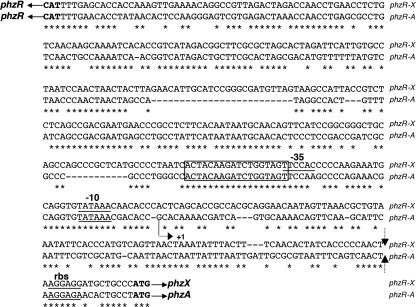

In comparing the primary amino acid sequences of the PhzR proteins from strains 2-79 and 30-84, we noticed that the annotated open reading frame of phzR2-79 had three extra codons at the region corresponding to the N terminus (GenBank accession number L48616). The coding sequence of phzR2-79 has a second potential translational start site at position 4, which is the annotated start codon for phzR30-84 (GenBank accession number L32729). Both start codons of phzR2-79 have potential upstream ribosomal binding sites. To identify the correct start codon of PhzR2-79, we cloned the corresponding open reading frame together with its promoter region in the broad-host-range vector pZLQ and mutated the first start site to an alanine and to an amber codon. Both mutants activated the transcription of our phzA::lacZ reporter in an acyl-HSL-dependent manner (data not presented). The conversion of the second ATG to an alanine codon resulted in the loss of acyl-HSL-dependent activation of the phzA::lacZ fusion (data not presented). These results strongly suggest that PhzR2-79 is translated from the second ATG in the coding sequence.

We subcloned phzR30-84 as a 1.7-kb BglII fragment from cosmid pLSP259 into pBluescript II SK. In confirming this construct, we noted that the sequence of our clone of phzR30-84 differed at 10 positions from the sequence in the GenBank database (accession number L32729). These differences resulted in four amino acid changes: arginine to alanine at position 43, alanine to tryptophan at position 95, serine to valine at position 232, and arginine to serine at position 233. The sequences of two additional phzR30-84 constructs derived from PCR fragments amplified using pLSP259 and genomic DNA from strain 30-84 as templates were identical to that of our subclone. All four new assignments in PhzR30-84 are conserved in the PhzR proteins of strains 2-79 and PCL1391 (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

PhzR of P. chlororaphis strains 30-84 and PCL1391 and that of P. fluorescens 2-79 are closely related. The corrected sequence of the PhzR protein from strain 30-84 (GenBank accession number EF626944) is aligned with the PhzR sequences of strains 2-79 (GenBank accession number L32729) and PCL1391 (GenBank accession number AF195615). Residues that are conserved in all three proteins are blocked in black. Changes in the sequence of PhzR from strain 30-84 relative to the reported sequence (GenBank accession number L48616) are marked with arrows. See text for details.

PhzR30-84 recognizes 3-OH-C6- and C6-HSL with equal sensitivities.

To examine the activity of PhzR30-84, we constructed a reporter system dependent on this activator by cloning the phzR-phzX intergenic region of strain 30-84 in the promoter-reporter vector pRG970b (37) (Table 1). This construct contains a fusion of the promoter of phzX with lacZYA. The reporter plasmid, called pSF116, was transformed into P. fluorescens 1855-344, together with pSF110, which codes for PhzR30-84.

Although PhzR30-84 has been reported to respond to C6-HSL, its similarity to PhzR2-79, as well as our previous and current analyses, suggests that the activator from strain 30-84 responds primarily to 3-OH-C6-HSL. To assess signal specificity, we assayed the PhzR30-84-mediated activation of the phzX30-84::lacZ fusion in cells incubated with different acyl-HSLs at several concentrations. PhzR2-79, as we previously reported (13), showed a clear preference for 3-OH-C6-HSL over C6-HSL and 3-OH-C8-HSL in activating its cognate phzA2-79::lacZ reporter (Fig. 6A). However, PhzR30-84 activated its reporter to similar levels in response to equivalent concentrations of 3-OH-C6-HSL and C6-HSL throughout the range of concentrations tested (Fig. 6B). PhzR30-84, like PhzR2-79 (13), recognized 3-OH-C8-HSL with much lower sensitivity and magnitude.

FIG. 6.

PhzR30-84 responds to N-(3-OH-hexanoyl)-l-HSL and N-(hexanoyl)-l-HSL with equal sensitivities. Cultures of the 30-84- and 2-79-based reporter strains were incubated with increasing concentrations of N-(3-OH-hexanoyl)-l-HSL (•), N-(hexanoyl)-l-HSL (▪), or N-(3-OH-octanoyl)-l-HSL (▴) for 3 h in ABM. Following incubation, the cells were assayed for β-galactosidase activity, expressed in Miller units. (A) The 2-79-based reporter strain harboring pSF105 (PhzR2-79) and pSF107 (phzA::lacZ). (B) The 30-84-based reporter strain harboring pSF110 (PhzR30-84) and pSF116 (phzX::lacZ). The experiment was repeated four times, and the mean values of all repetitions together with the standard errors are shown in the plots.

PhzR proteins of strains 30-84 and 2-79 are functionally interchangeable.

To determine if the PhzR orthologs of strains 2-79 and 30-84 can activate the heterologous phz promoter, we swapped the PhzR clones in the P. fluorescens 1855 reporter strains, placing pSF110 encoding PhzR30-84 with the phzA2-79::lacZ fusion and pSF105 encoding PhzR2-79 with the phzX30-84::lacZ fusion. The source of the PhzR activator made no difference in the response of the reporter strains in the TLC assays (data not shown) indicating that the two PhzR proteins and their target promoters are functionally equivalent.

Signal recognition specificity of PhzR30-84.

To determine which of the acyl-HSLs produced by strain 30-84 contribute to the activation of PhzR30-84, crude extracts of culture supernatants from strains 30-84 or 2-79, together with standards, were chromatographed on two TLC plates, one of which was overlaid with the 30-84-based indicator strain and the other with the 2-79-based indicator strain, P. fluorescens 1855-344 (pSF105)(pSF107) (13) (Table 1; Fig. 7A and B).

FIG. 7.

PhzR30-84 responds most strongly to N-(3-OH-hexanoyl)-l-HSL present in crude extracts of culture supernatants from strains 2-79 and 30-84. Ethyl acetate extracts were chromatographed and identical plates were overlaid with either the 30-84-based reporter strain (A) or the 2-79-based reporter strain (B). Lanes 1 and 2 contain crude extracts of strains 2-79 and 30-84, respectively. Lanes 3 and 4 contain samples of authentic N-(3-OH-hexanoyl)-l-HSL and N-(hexanoyl)-l-HSL, respectively. For the visualization of both N-(3-OH-hexanoyl)-l-HSL and N-(hexanoyl)-l-HSL present in the crude extracts, another set of plates was chromatographed and overlaid with mixtures of either C. violaceum CV026blu and the 30-84-based reporter (C) or C. violaceum CV026blu and the 2-79-based reporter (D). Lane 1 contains an extract of strain 2-79, and lanes 2, 3, 4, and 5 contain authentic N-(3-OH-octanoyl)-l-HSL, N-(3-OH-hexanoyl)-l-HSL, N-(hexanoyl)-l-HSL, and a mixture of N-(3-OH-hexanoyl)-l-HSL plus N-(hexanoyl)-l-HSL, respectively.

Of the suite of signals produced by both strains 30-84 and 2-79, the two reporter strains responded to 3-OH-C6-HSL with maximum intensity (Fig. 7A and B, lanes 1 and 2). They also responded to two additional acyl-HSLs migrating slower than 3-OH-C6-HSL but with greatly diminished intensity (Fig. 7A and B, lanes 1 and 2). These weakly activating species could represent 3-OH-C7-HSL and 3-OH-C8-HSL or C6-HSL.

To improve the detection of alkanoyl-acyl-HSLs, we overlaid a similar set of two TLC plates with a mixture of Pseudomonas and Chromobacterium indicator strains, the latter of which recognizes mid-chain-length alkanoyl-HSLs. In this overlay, the two reporter strains selectively responded to different acyl-HSLs, resulting in the visualization of both hydroxy- and alkanoyl-acyl-HSL species (Fig. 7C and D). The Chromobacterium indicator produced a purple spot in response to the authentic C6-HSL standard, while the Pseudomonas reporter responded to the 3-OH-C6-HSL standard (Fig. 7C and D, lanes 3, 4, and 5). The two extracts yielded strong blue spots from the Pseudomonas reporter, corresponding to 3-OH-C6-HSL, and a weaker purple spot from the Chromobacterium reporter, corresponding to C6-HSL. The Pseudomonas reporter also identified a faint blue signal corresponding to 3-OH-C8-HSL just below the purple spot in both extracts. That the two Pseudomonas reporters respond to 3-OH-C6-HSL and not to C6-HSL present in the extracts produced from culture supernatants of the wild-type pseudomonads suggests that the hydroxyl derivative is the biologically relevant signal produced by these bacteria for the activation of their PhzR proteins.

PhzR proteins and phz promoters of strains 2-79 and 30-84 exhibit functional differences.

The reporter systems of strains 2-79 and 30-84, while showing differences in their responsivenesses to C6- and 3-OH-C6-HSL, also differed with respect to maximum promoter activities. At saturating concentrations of 3-OH-C6, the PhzR2-79-activated phzA::lacZ fusion exhibited activity almost twofold higher than that of the PhzR30-84-activated phzX::lacZ fusion (compare Fig. 6A and B).

The difference in the acyl-HSL responsivenesses of the 30-84 and 2-79 reporter strains could be due to the properties of the PhzR activators or the respective phz promoters. To differentiate between these possibilities, we assayed signal specificity as described above, using the reporter strains in which we had swapped the PhzR clones. PhzR30-84, when activating the phzA::lacZ fusion of strain 2-79, responded to 3-OH-C6-HSL and C6-HSL with equal sensitivities (Fig. 8A), whereas PhzR2-79 continued to show a clear preference for 3-OH-C6-HSL in activating the transcription of the heterologous phzX::lacZ reporter from strain 30-84 (Fig. 8B). Moreover, the differences in the magnitudes of promoter activities remained consistent, with the phzA::lacZ fusion exhibiting high activity (Fig. 8A) compared to that observed from the phzX::lacZ fusion (Fig. 8B), no matter the source of PhzR.

FIG. 8.

Differences in the levels of transcription from the phz promoters of strains 2-79 and 30-84 are independent of the source of the PhzR proteins. Reporter strains harboring phzX::lacZ or phzA::lacZ fusion plasmids together with functional copies of noncognate phzR were incubated with increasing concentrations of N-(3-OH-hexanoyl)-l-HSL (•), N-(hexanoyl)-l-HSL (▪), or N-(3-OH-octanoyl)-l-HSL (▴) for 3 h in ABM. Following incubation, the cells were assayed for β-galactosidase activity, expressed as Miller units. (A) Reporter strain harboring pSF110 (PhzR30-84) and pSF107 (phzA::lacZ); (B) reporter strain harboring pSF105 (PhzR2-79) and pSF116 (phzX::lacZ). The experiment was repeated three times, and the mean values of all repetitions together with the standard errors are shown in the plots.

DISCUSSION

3-OH-C6-HSL is the major signal synthesized by strain 30-84.

In the present communication, we show that P. chlororaphis 30-84, P. chlororaphis PCL1391, and P. fluorescens 2-79 produce almost indistinguishable suites of acyl-HSLs comprised of 3-OH-C6-HSL, 3-OH-C7-HSL, 3-OH-C8-HSL, 3-OH-C10-HSL, C5-HSL, and C6-HSL (Fig. 1; Table 2). The pool of acyl-HSLs synthesized by strain 30-84 differs from that of strain 2-79 only by the presence of easily detectable levels of C4-HSL in the former. Moreover, based on the expression of the phzI gene of strain 30-84 in alternative hosts, this synthase accounts for the production of wild-type amounts of all of the acyl-HSL signals produced by strain 30-84, except C4-HSL (Table 2). As with PhzI2-79, recombinant PhzI30-84 produces the 3-OH-acyl-HSLs at levels more than 100-fold higher than the alkanoyl species (Table 2). Consistent with this observation, strain 30-84 produces 3-OH-C6-HSL as its most abundant signal (Table 2).

Our analysis of the acyl-HSL signals produced by strain 30-84 and its recombinantly expressed phzI gene differs significantly from a previous study in which C6-HSL was identified as the principal signal (41). Differences in medium, culture conditions, or solvent used for extraction cannot account for this discrepancy. However, we used as the primary reporter strain A. tumefaciens NTL4(pZLR4), which responds strongly to 3-oxo- and 3-OH-acyl-HSLs. Our preliminary assignments were then confirmed by LC/MS-MS. Based on our findings, we conclude that the PhzI proteins from strains 30-84 and 2-79 are functionally identical and that 3-OH-C6-HSL is the quantitatively dominant signal produced by strain 30-84. Although not based upon such a detailed examination, from our TLC analysis (Fig. 1) we also conclude that P. chlororaphis PCL1391 produces the same set of 3-OH-acyl HSLs. Moreover, it is likely that the PhzR protein of this strain is activated by 3-OH-C6-HSL.

CsaI catalyzes synthesis of C4- and C6-acyl-HSLs.

Strain 30-84 produces significant amounts of C4-HSL, an acyl-HSL not detected in extracts from strain 2-79 by bioassay or MS. CsaI, the second acyl-HSL synthase present in strain 30-84, apparently is responsible for synthesizing this short-chain alkanoyl-HSL (Table 2; Fig. 4). CsaI also contributes to the total pool of C6-HSL produced by strain 30-84 and, when expressed in heterologous hosts, synthesizes the rare odd-carbon-chain-length N-(pentanoyl)-l-HSL (C5-HSL) (Table 2; Fig. 4). The production primarily of C4-HSL by CsaI is consistent with its sequence relatedness to RhlI, an acyl-HSL synthase of P. aeruginosa, which also synthesizes this alkanoyl signal (39). CsaI and PhzI account for the total pool of acyl-HSLs synthesized by strain 30-84. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that other acyl-HSL synthases could contribute quantitatively to the set of signals produced by strain 30-84.

PhzR30-84 recognizes 3-OH-C6-HSL and C6-HSL with equal sensitivities.

Consistent with the gene homologies and with the relative abundance of each of the signals, our data support our conclusion that 3-OH-C6-HSL is the biologically relevant activating ligand for PhzR30-84. However, in contrast to PhzR2-79, PhzR30-84 exhibited equal sensitivities to C6-HSL in activating both the phzX::lacZ and phzA::lacZ promoter fusions (Fig. 6 and 8). Only one other member of the LuxR family, QscR from P. aeruginosa, is known to exhibit such relaxed specificity. At low concentrations, this regulator responds with essentially equal sensitivities to four acyl-HSLs (15).

The less stringent response of PhzR30-84 to the two signals suggests that the acyl-HSL recognition properties of PhzR2-79 and PhzR30-84 are different. The LuxR family of transcriptional regulators contains distinct DNA- and acyl-HSL-binding domains (17, 18, 34, 38, 43). In TraR, the LuxR homologue operative in the plant pathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens, amino acid residues responsible for signal binding are located at the N terminus of the protein, whereas the residues important for DNA binding are located at the C terminus (38, 43). PhzR30-84 and PhzR2-79 show high sequence identity in their C-terminal regions, indicating that their DNA recognition properties are similar (Fig. 5). The N-terminal segments of the two proteins, on the other hand, show comparatively higher diversity that could account for the apparent differences in their signal discrimination properties. Based on the crystal structure of the TraR-DNA complex (43), we located the positions of the residues, which are different within the N-terminal regions of PhzR30-84 and PhzR2-79. None of the changes are in residues that we would expect to make contact with the acyl-HSL ligand. However, four variant residues, histidine-66, leucine-78, arginine-102, and serine-114, are relatively close to the predicted signal binding site. How these sequence differences might modify signal discrimination remains to be determined.

Consistent with the high sequence similarity at their C-terminal DNA binding regions, PhzR30-84 and PhzR2-79 efficiently activated transcription from the heterologous promoters (Fig. 9). The promoter regions of the phz operons of strains 30-84 and 2-79 contain identical 18-bp palindromic phz boxes (Fig. 9). However, the comparative activities of the two promoters are different, with PphzA showing higher levels of activity irrespective of the source of the PhzR proteins (Fig. 6 and 8). Although very similar, the two promoters differ in several aspects (Fig. 9). Overall, the regions between the phz boxes and the ATG of the first gene of the phz operon from strains 2-79 and 30-84 are only 68% identical, and the promoter region of phzX is 3 bp longer than that of phzA (Fig. 9). The −35 element of PphzA (13) and the corresponding putative −35 region of PphzX, although overlapping with the respective phz boxes, differ by 1 nucleotide. Finally, the sequence directly upstream of the phz box, the promoter region at which the α-subunit of RNA polymerase contacts the DNA during transcription of class II promoters dependent on catabolite activator protein (3), is poorly conserved between the two isolates. Any of these differences could account for the weaker promoter activity exhibited by the 30-84 lacZ-based reporter fusion.

FIG. 9.

The promoter regions of the phz operons from strains 30-84 and 2-79 exhibit sequence and spacing differences. The palindromic phz boxes of the two promoter regions are marked with a rectangle, and the positions of the −35 and −10 elements are underlined. The transcriptional start site of phzA of strain 2-79 is marked as +1 (13), and the junctions at which the phz promoter regions are fused with the lacZ gene in the promoter-reporter vector pRG970b are marked with broken arrows. The putative ribosomal binding sites (rbs) for the phzX and phzA genes of the two phz operons are underlined and labeled.

Interaction between quorum-sensing systems in strain 30-84.

The less stringent signal recognition properties of PhzR30-84 could be a factor that connects the PhzI-dependent quorum-sensing system with other quorum-sensing systems operative in strain 30-84 or in other members of the microbial community (19, 41, 44). The second quorum-sensing system in strain 30-84, the CsaRI system, is closely related to the RhlRI system of P. aeruginosa with both systems regulating cell surface properties (25, 44). Moreover, CsaI and RhlI produce both C4-HSL and C6-HSL.

C6-HSL is not produced by strain 30-84 at levels high enough to activate the PhzR30-84 reporter system (Fig. 7A). This observation suggests that under the conditions tested, the alkanoyl-acyl-HSLs synthesized by CsaI do not contribute significantly to the PhzR-mediated activation of expression of the phz operon in this strain. However, nothing is known about the regulation of the csaRI locus, and it is conceivable that under appropriate conditions CsaI might be induced to produce amounts of C6-HSL which, in combination with the C6-HSL produced by PhzI, are sufficient to activate PhzR30-84.

The PhzI synthases from the three pseudomonads tested all produce as many as six acyl-HSLs of two substitution classes. However, production of multiple signals by an acyl-HSL synthase is not an uncommon phenomenon (4, 13). Almost all acyl-HSL synthases studied to date produce more than one signal, with the production of additional acyl-HSLs representing the relaxed substrate specificity characteristic of the LuxI family of synthases (11, 12, 26, 30, 42). These alternative signals, which do not necessarily play a role in controlling quorum sensing in the producer bacteria, have the potential to influence the acyl-HSL-dependent regulatory systems of other bacteria occupying the same habitat (41). Characteristically, the cognate signal in bacteria secreting multiple signals is produced in the highest amounts. Although PhzR30-84 fails to discriminate between 3-OH-C6-HSL and C6-HSL, 3-OH-C6-HSL is produced at levels considerably higher than those seen for C6-HSL. Based on our findings, we conclude that 3-OH-C6-HSL is the biologically relevant signal for the PhzR-dependent regulation of phenazine gene expression in strain 30-84.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work were funded by grant no. R01 GM52465 from the NIH and C-FAR grant no. IDACF01I-3-3 CS from the State of Illinois to S.K.F. and by grant no. AI 48660 from the NIH to M.E.A.C. J.K. was supported by grant no. R01 GM69338 from the NIH to Robert C. Murphy.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anjaiah, V., N. Koedam, B. Nowak-Thompson, J. E. Loper, M. Hofte, J. T. Tambong, and P. Cornelis. 1998. Involvement of phenazines and anthranilate in the antagonism of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PNA1 and Tn5 derivatives toward Fusarium spp. and Pythium spp. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11:847-854. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1995. Short protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, NY.

- 3.Benoff, B., H. Yang, C. L. Lawson, G. Parkinson, J. Liu, E. Blatter, Y. W. Ebright, H. M. Berman, and R. H. Ebright. 2002. Structural basis of transcription activation: the CAP-alpha CTD-DNA complex. Science 297:1562-1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cha, C., P. Gao, Y. C. Chen, P. D. Shaw, and S. K. Farrand. 1998. Production of acyl-homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signals by gram-negative plant-associated bacteria. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11:1119-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chilton, M.-D., T. C. Currier, S. K. Farrand, A. J. Bendich, M. P. Gordon, and E. W. Nester. 1974. Agrobacterium tumefaciens DNA and PS8 bacteriophage DNA not detected in crown gall tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 71:3672-3676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chin-A-Woeng, T. F. C., G. V. Bloemberg, A. J. Van der Bij, K. M. G. M. Van der Drift, J. Schripsema, B. Kroon, R. J. Scheffer, C. Keel, P. A. H. M. Bakker, H.-V. Tichy, F. J. De Bruijn, J. E. Thomas-Oates, and B. J. J. Lugtenberg. 1998. Biocontrol by phenazine-1-carboxamide producing bacterium Pseudomonas chlororaphis PCL1391 of tomato root rot caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicis-lycopersici. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11:1069-1077. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chin-A-Woeng, T. F. C., D. van den Broek, G. de Voer, K. M. van der Drift, S. Tuinman, J. E. Thomas-Oates, B. J. J. Lugtenberg, and G. V. Bloemberg. 2001. Phenazine-1-carboxamide production in the biocontrol strain Pseudomonas chlororaphis PCL1391 is regulated by multiple factors secreted into the growth medium. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 14:969-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin-A-Woeng, T. F. C., J. E. Thomas-Oates, B. J. J. Lugtenberg, and G. V. Bloemberg. 2001. Introduction of the phzH gene of Pseudomonas chlororaphis PCL1391 extends the range of biocontrol ability of phenazine-1-carboxylic acid-producing Pseudomonas spp. strains. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 14:1006-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conway. H. F., W. C. Haynes, R. W. Jackson, J. M. Locke, T. G. Pridham, V. E. Sohns, and F. H. Stodola. 1956. Pseudomonas aureofaciens Kluyver and phenazine α-carboxylic acid, its characteristic pigment. J. Bacteriol. 72:412-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farrand, S. K., Y. Qin, and P. Oger. 2002. Quorum-sensing system of Agrobacterium plasmids: analysis and utility. Methods Enzymol. 358:452-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gould, T. A., J. Herman, J. Krank, R. C. Murphy, and M. E. Churchill. 2006. Specificity of acyl-homoserine lactone synthases examined by mass spectrometry. J. Bacteriol. 188:773-783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang, I., P. L. Li, L. Zhang, K. R. Piper, D. M. Cook, M. E. Tate, and S. K. Farrand. 1994. TraI, a LuxI homologue, is responsible for production of conjugation factor, the Ti plasmid N-acylhomoserine lactone autoinducer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:4639-4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan, S. R., D. V. Mavrodi, G. J. Jog, H. Suga, L. S. Thomashow, and S. K. Farrand. 2005. Activation of the phz operon of Pseudomonas fluorescens 2-79 requires the LuxR homolog PhzR, N-(3-OH-hexanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone produced by the LuxI homolog PhzI, and a cis-acting phz box. J. Bacteriol. 187:6517-6527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King, E. O., M. K. Ward, and D. E. Raney. 1954. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescin. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 44:301-307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, J. H., Y. Lequette, and E. P. Greenberg. 2006. Activity of purified QscR, a Pseudomonas aeruginosa orphan quorum-sensing transcription factor. Mol. Microbiol. 59:602-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo, Z. Q., and S. K. Farrand. 1999. Cloning and characterization of a tetracycline resistance determinant present in Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. J. Bacteriol. 181:618-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo, Z. Q., and S. K. Farrand. 1999. Signal-dependent DNA binding and functional domains of the quorum-sensing activator TraR as identified by repressor activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9009-9014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo, Z. Q., A. J. Smyth, P. Gao, Y. Qin, and S. K. Farrand. 2003. Mutational analysis of TraR. Correlating function with molecular structure of a quorum-sensing transcriptional activator. J. Biol. Chem. 278:13173-13182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maddula, V. S., Z. Zhang, E. A. Pierson, and L. S. Pierson III. 2006. Quorum sensing and phenazines are involved in biofilm formation by Pseudomonas chlororaphis (aureofaciens) strain 30-84. Microb. Ecol. 52:289-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mavrodi, D. V., V. N. Ksenzenko, R. F. Bonsall, R. J. Cook, A. M. Boronin, and L. S. Thomashow. 1998. A seven-gene locus for synthesis of phenazine-1-carboxylic acid by Pseudomonas fluorescens 2-79. J. Bacteriol. 180:2541-2548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mavrodi, D. V., R. F. Bonsall, S. M. Delaney, M. J. Soule, G. Phillips, and L. S. Thomashow. 2001. Functional analysis of genes for biosynthesis of pyocyanin and phenazine-1-carboxamide from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 183:6454-6465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazzola, M., R. J. Cook, L. S. Thomashow, D. M. Weller, and L. S. Pierson III. 1992. Contribution of phenazine antibiotic biosynthesis to the ecological competence of fluorescent pseudomonads in soil habitats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:2616-2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClean, K. H., M. K. Winson, L. Fish, A. Taylor, S. R. Chhabra, M. Camara, M. Daykin, J. H. Lamb, S. Swift, B. W. Bycroft, G. S. Stewart, and P. Williams. 1997. Quorum sensing and Chromobacterium violaceum: exploitation of violacein production and inhibition for the detection of N-acylhomoserine lactones. Microbiology 143:3703-3711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller, J. H. 1972. Assay of β-galactosidase, p. 352-355. In J. H. Miller (ed.), Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 25.Ochsner, U. A., and J. Reiser. 1995. Autoinducer-mediated regulation of rhamnolipid biosurfactant synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:6424-6428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pearson, J. P., K. M. Gray, L. Passador, K. D. Tucker, A. Eberhard, B. H. Iglewski, and E. P. Greenberg. 1994. Structure of the autoinducer required for expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:197-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pierson, L. S., III, and L. S. Thomashow. 1992. Cloning and heterologous expression of the phenazine biosynthetic locus from Pseudomonas aureofaciens 30-84. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 5:330-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierson, L. S., III, V. D. Keppenne, and D. W. Wood. 1994. Phenazine antibiotic biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aureofaciens 30-84 is regulated by PhzR in response to cell density. J. Bacteriol. 176:3966-3974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pierson, L. S., III, T. Gaffney, S. Lam, and F. Gong. 1995. Molecular analysis of genes encoding phenazine biosynthesis in the biological control bacterium. Pseudomonas aureofaciens 30-84. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 134:299-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schaefer, A. L., D. L. Val, B. L. Hanzelka, J. E. Cronan, Jr., and E. P. Greenberg. 1996. Generation of cell-to-cell signals in quorum sensing: acyl homoserine lactone synthase activity of a purified Vibrio fischeri LuxI protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:9505-9509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serkova, N. J., T. F. Fuller, J. Klawitter, C. E. Freise, and C. U. Niemann. 2005. 1H-NMR-based metabolic signatures of mild and severe ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat kidney transplants. Kidney Int. 67:1142-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw, P. D., G. Ping, S. L. Daly, C. Cha, J. E. Cronan, Jr., K. L. Rinehart, and S. K. Farrand. 1997. Detecting and characterizing N-acyl-homoserine lactone signal molecules by thin-layer chromatography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:6036-6041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Pühler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering. Transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slock, J., D. VanRiet, D. Kolibachuk, and E. P. Greenberg. 1990. Critical regions of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein defined by mutational analysis. J. Bacteriol. 172:3974-3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomashow, L. S., and D. M. Weller. 1988. Role of a phenazine antibiotic from Pseudomonas fluorescens in biological control of Gaeumannomyces graminis var.tritici. J. Bacteriol. 170:3499-3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner, J. M., and A. J. Messenger. 1986. Occurrence, biochemistry and physiology of phenazine pigment production. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 27:211-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van den Eede, G., R. Deblaere, K. Goethals, M. Van Montagu, and M. Holsters. 1992. Broad host range and promoter selection vectors for bacteria that interact with plants. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 5:228-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vannini, A., C. Volpari, C. Gargioli, E. Muraglia, R. Cortese, R. De Francesco, P. Neddermann, and S. D. Marco. 2002. The crystal structure of the quorum sensing protein TraR bound to its autoinducer and target DNA. EMBO J. 21:4393-4401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winson, M. K., M. Camara, A. Latifi, M. Foglino, S. R. Chhabra, M. Daykin, M. Bally, V. Chapon, G. P. Salmond, B. W. Bycroft, A. Lazdunski, G. S. A. B. Stewart, and P. Williams. 1995. Multiple N-acyl-l-homoserine lactone signal molecules regulate production of virulence determinants and secondary metabolites in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:9427-9431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wood, D. W., and L. S. Pierson III. 1996. The phzI gene of Pseudomonas aureofaciens 30-84 is responsible for the production of a diffusible signal required for phenazine antibiotic production. Gene 168:49-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wood, D. W., F. Gong, M. M. Daykin, P. Williams, and L. S. Pierson III. 1997. N-Acyl-homoserine lactone-mediated regulation of phenazine gene expression by Pseudomonas aureofaciens 30-84 in the wheat rhizosphere. J. Bacteriol. 179:7663-7670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang, L., P. J. Murphy, A. Kerr, and M. E. Tate. 1993. Agrobacterium conjugation and gene regulation by N-acyl-l-homoserine lactones. Nature 362:446-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang, R. G., T. Pappas, J. L. Brace, P. C. Miller, T. Oulmassov, J. M. Molyneaux, J. C. Anderson, J. K. Bashkin, S. C. Winans, and A. Joachimiak. 2002. Structure of a bacterial quorum-sensing transcription factor complexed with pheromone and DNA. Nature 417:971-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang, Z., and L. S. Pierson III. 2001. A second quorum-sensing system regulates cell surface properties but not phenazine antibiotic production in Pseudomonas aureofaciens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4305-4315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]