Abstract

Ammonia has been shown to function as a morphogen at multiple steps during the development of the cellular slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum; however, it is largely unknown how intracellular ammonia levels are controlled. In the Dictyostelium genome, there are five genes that encode putative ammonium transporters: amtA, amtB, amtC, rhgA, and rhgB. Here, we show that AmtA regulates ammonia homeostasis during growth and development. We found that cells lacking amtA had increased levels of ammonia/ammonium, whereas their extracellular ammonia/ammonium levels were highly decreased. These results suggest that AmtA mediates the excretion of ammonium. In support of a role for AmtA in ammonia homeostasis, AmtA mRNA is expressed throughout the life cycle, and its expression level increases during development. Importantly, AmtA-mediated ammonia homeostasis is critical for many developmental processes. amtA− cells are more sensitive to NH4Cl than wild-type cells in inhibition of chemotaxis toward cyclic AMP and of formation of multicellular aggregates. Furthermore, even in the absence of exogenously added ammonia, we found that amtA− cells produced many small fruiting bodies and that the viability and germination of amtA− spores were dramatically compromised. Taken together, our data clearly demonstrate that AmtA regulates ammonia homeostasis and plays important roles in multiple developmental processes in Dictyostelium.

The cellular slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum has a unique life cycle consisting of a unicellular growth phase and a multicellular developmental phase. When food sources such as bacteria are available, Dictyostelium amoeboid cells proliferate by cytokinesis. Starvation triggers cells to undergo developmental processes, during which up to 105 cells display chemotaxis toward cyclic AMP (cAMP) and form multicellular aggregates. On top of the aggregates, a small projection is formed, and this process is called tip formation. Cells located at the anterior part of aggregates differentiate into prestalk cells, precursors of stalk cells, while the rest of the aggregates become prespore cells, precursors of spores. The tipped aggregates form elongated multicellular structures called slugs. Slugs migrate and eventually culminate to form a fruiting body consisting of a mass of spores supported by a stalk (25, 44, 47).

A number of diffusible molecules regulate the development of Dictyostelium, including cAMP, differentiation-inducing factor, adenosine, and ammonia (5, 47, 74, 78). Ammonia has been shown to affect many developmental events in Dictyostelium. For example, in the presence of ammonia, the production and secretion of cAMP are inhibited, resulting in the impairment of chemotaxis toward cAMP and subsequent tip formation during early development (23, 61, 77). At later stages of development, ammonia acts against differentiation-inducing factor, suppresses differentiation into prestalk cells, and promotes differentiation into prespore cells (6, 26, 64, 72). In addition, ammonia plays an important role in the choice between the formation of a migrating slug and culmination. High concentrations of ammonia keep slugs migrating and block the initiation of culmination (60). The exhaustion of the ammonia supply triggers culmination at least in part by activating protein kinase A (PKA) through the DhkC signaling pathway (30, 61, 63). In fruiting bodies, extremely high concentrations of ammonium phosphate in sori maintain spore dormancy through the activation of the sporulation-specific adenylyl cyclase ACG (8).

Ammonia is produced by protein catabolism, and ammonia levels rise during development, when most energy is generated by the degradation of protein and RNA (27, 60, 71, 76). It has been suggested that glutamine synthetases, which incorporate ammonia into glutamine, control intracellular levels of ammonia. The expression of glutamine synthetases is developmentally regulated, and their activity becomes elevated during the culmination stage (12-14, 24), suggesting a role of glutamine synthetases in culmination. Indeed, the pharmacological inhibition of glutamine synthetase blocks culmination during development (14). In addition, there are five genes, amtA, amtB, amtC, rhgA, and rhgB, which belong to the evolutionarily conserved family of ammonium transporter/methylammonium permease/rhesus protein (Amt/Mep/Rh) in the Dictyostelium genome (15). Previous studies have shown that developmental phenotypes in cells lacking AmtC can be rescued by deleting the AmtA protein (62). These studies suggest that AmtC and AmtA antagonistically regulate developmental processes and that AmtA and AmtC function in either ammonium transport or ammonium sensing (20, 37, 62). In this study, we show that AmtA regulates intracellular ammonium/ammonia levels during growth and development and is critical for the morphogenesis of multicellular aggregates and normal spore formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, culture, and development.

The D. discoideum strain Ax2 (40, 73) was used for wild-type cells in this study. For sequencing, strain Ax4 (40) was used. Cells were cultured at 22°C either in HL-5 medium (73) or on A medium agar plates (0.5% glucose, 0.05% yeast extract, 0.75 g of proteose peptone, 16.5 mM KH2PO4, 4.0 mM K2HPO4, 2.0 mM MgSO4, 1.5% agar) associated with Klebsiella pneumoniae. For the selection and maintenance of transformants, the medium was supplemented with 10 μg/ml of blasticidin S (Wako) or 20 μg/ml Geneticin (Calbiochem). Peptone and yeast extract were obtained from Difco Laboratories.

For synchronous development, exponentially growing cells were harvested and washed three times in lower pad solution (LPS) buffer (20 mM KCl, 0.24 mM MgCl2, 40 mM K2HPO4-KH2PO4, pH 6.4) and placed on 47-mm-diameter cellulose membrane filters (Toyo Roshi Kaisha, Ltd.) at a density of 5 × 106 cells/cm2. The filters were placed on M-085 paper pads (Toyo Roshi Kaisha, Ltd.) containing LPS and housed in 6-cm-diameter petri dishes at 22°C. When NH4Cl was added, ammonia buffer A (20 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 40 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.3) was used instead of LPS buffer. Developmental processes were observed with an Olympus SZX12 microscope. Stalk lengths were determined using the NIH Image program (developed at the National Institutes of Health [http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/]).

Nucleic acid analyses.

Genomic DNA was extracted as described previously (33, 35). Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) by following the manufacturer's instructions. Poly(A)-containing RNA was purified using Oligotex-dT30 Super (JSR). RNA from prespore and prestalk cells was extracted as previously described (53, 56). Southern and Northern blot analyses were performed as previously described (57). A probe specific for amtA was prepared by random priming for a 1.1-kb EcoT22I/NotI-digested fragment of cDNA SSB490.

The amtA DNA sequence was determined by sequencing cDNA clones SSB490, SSB126, and SLB420, generated by the Japanese cDNA project (51, 67, 68), and the corresponding region of genomic DNA.

Phylogenetic analysis.

A neighbor-joining tree was generated by the Clustal program (65) based on Pfam database alignment (PF00909). The Swiss-Prot/TrEMBL sequence accession numbers for the indicated proteins are as follows: D. discoideum AmtA, Q9BLG4; D. discoideum AmtB, Q9BLG3; D. discoideum AmtC, Q8MXY0; Methanobacterium thermautotrophicum MTH661, O26757; Escherichia coli AmtB, P37905; Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mep1p, P40260; S. cerevisiae Mep2p, P41948; S. cerevisiae Mep3p, P53390; Caenorhabditis elegans C05E11.4, P54145; Arabidopsis thaliana AMT1;1, P54144; A. thaliana AMT1;2, Q9ZPJ8; A. thaliana AMT2;1, Q9M6N7; Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Rhp, Q94CJ2; C. elegans Rhp-1, Q9N2M5; Drosophila melanogaster Rhp, Q9V3T3; Xenopus laevis RhAG, Q9DGD8; Homo sapiens RhAG, O43514; H. sapiens RhBG, Q9H310; H. sapiens RhCG, Q9UBD6; H. sapiens RhCE, P18577; and H. sapiens RhD, Q02161. Amt alpha and beta groupings were based on previous work (39).

Gene disruption and expression.

For amtA disruption, the blasticidin resistance gene (bsr) from pBsrΔBam (1) was used as a selection marker. The amtA coding region in the cDNA clone SSB490 was amplified by PCR using primers LA-XbaI (5′-gctctagaTGTAACCAACCACCACCCCAAATCC-3′) and LA-HindIII (5′-cccaagcttGGTTTGGTTTTAATGCAGGTAGTGC-3′) (lowercase indicates restriction sites), and then the PCR product was ligated with a 1.3-kb XbaI/HindIII fragment of pBsrΔBam. For efficient homologous recombination, part of the 5′ region of the construct was replaced by a genomic sequence containing the first intron. The sequence for displacement was amplified from genomic DNA with the primers LAP-1 (5′-AATCAAGTAGCACCAGATCCAGG-3′) and LA-XbaI. The bsr gene was oriented in the same direction as the amtA gene to ensure the presence of a transcriptional terminator in the middle of the amtA coding sequence. From the resulting vector, pAMTAbsr (5.9 kb), the 2.9-kb amtA or bsr fragment was excised with SalI and NotI and used for transformation.

To express the wild-type amtA gene, a plasmid containing amtA was constructed by inserting a PCR fragment containing the complete amtA open reading frame into the Dictyostelium extrachromosomal expression vector HK12neo, a derivative of MB12neo (43).

Determinations of ammonia/ammonium.

The intercellular levels of ammonia were measured as follows (2, 8). Cells were developed on nitrocellulose filters at 5 × 106 cells/cm2. Filters were placed on a paper pad containing 2 ml of KK2 buffer (20 mM KH2PO4-K2HPO4, pH 6.4) and housed in petri dishes at 22°C. Cells were then harvested in 30 ml of ice-cold KK2 containing 20 mM EDTA at different time points during development, washed, and resuspended in 1 ml of KK2 buffer. The cell suspension was homogenized with a Mini-Bead-Beater (Wakenyaku Co., Ltd.), using 0.5-mm-diameter glass beads at 5,000 rpm for 3 min. For extracellular measurements, the paper pad under the nitrocellulose filter was soaked in 20 ml of KK2 buffer for 20 min to allow the ammonia to diffuse from the pad, and the resultant solution was used as a sample of the extracellular environment of the cells. To measure ammonia in the spores and spore mass solution, cells were developed on membrane filters, and sori were collected using a glass capillary. After centrifugation at 1,400 × g for 5 min, the supernatant was used as spore mass solution. The pellet of spores was resuspended in 1 ml of KK2 and then homogenized as described above. The concentrations of ammonia/ammonium in the sample solutions were measured using a Ti-9001Ka ammonia electrode (Toko Chemical Laboratories Co., Ltd.), by following the manufacturer's instructions.

Spore viability and germination.

The germination rates of spores were determined as described previously (50). Spores were collected in KK2 buffer from fruiting bodies on agar plates with a wire loop. To induce synchronous germination, 30 μl of supernatant from an overnight culture of K. pneumoniae in A medium was added to 0.3 ml of spore suspension in a siliconized 20-ml test tube (28). After being shaken at 150 rpm at 22°C for 6 h, germinated spores were counted using a hemocytometer. To determine the viability of spores, vital staining with propidium iodide (PI) was used (50). Spores were collected at 2, 4, 6, and 8 days after fruiting body formation, suspended in KK2 buffer, and stained with 20 μg/ml of PI (Sigma) for 5 min.

Glucose assay.

Glucose levels were measured as described previously (34), with a minor modification. Cells were grown in shaking cultures at 22°C in HL-5 medium with maltose as a carbohydrate source. Cells were harvested, developed for 0, 6, and 12 h in shaking cultures, and collected by centrifugation. The pellets were lysed by freezing at −70°C overnight. The pellets were thawed and resuspended in distilled water at 6 × 108 cells/ml. The lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 5 min, and 80 μl of the supernatants was used to measure glucose using a Sigma glucose assay kit (catalog no. GAGO20), by following the manufacturer's instructions. The protein concentration of lysate was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit (catalog no. 500-0006).

Immunoblotting.

Cells were developed on agar plates, and spores were harvested. Whole-cell lysates were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotted on polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Blots were immunostained with monoclonal antiactin antibody (C4; Chemicon) or monoclonal antiphosphotyrosine antibody clone PY20 (ICN), as previously described (81).

RESULTS

AmtA controls ammonia homeostasis during growth and development.

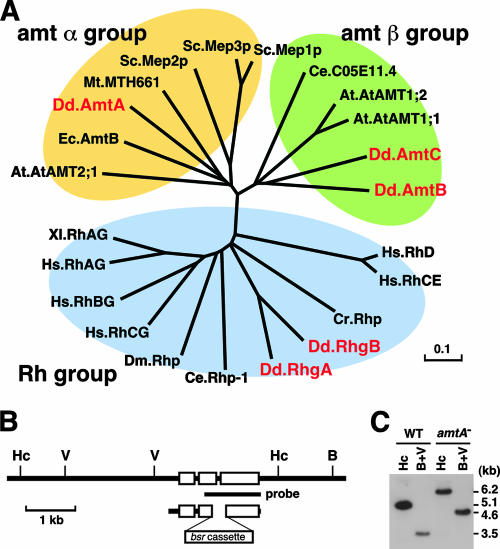

The Dictyostelium genome contains five genes, amtA, amtB, amtC, rhgA, and rhgB, which belong to the Amt/Mep/Rh family. A phylogenetic analysis showed that these five genes are divided into three groups: Amt alpha, Amt beta, and Rh (Fig. 1A). Although most organisms carry only one type of Amt/Mep/Rh gene (for example, vertebrates carry only genes that belong to the Rh group), Dictyostelium has all three types. In Dictyostelium, there are two genes that belong to each of the Rh (rhgA and rhgB) and Amt beta (amtB and amtC) groups, and the Amt alpha group contains a single gene, amtA. In this paper, we focused on the characterization of amtA. amtA encodes a 463-amino-acid protein (49.1 kDa), and a hydropathy analysis suggests that AmtA contains 11 transmembrane segments. The AmtA protein displays 11.0 to 23.6% identity to other Amt/Mep/Rh proteins in Dictyostelium and 23.8 to 35.6% identity to proteins in the Amt alpha groups in other organisms.

FIG. 1.

Disruption of the amtA gene. (A) Phylogenetic analysis of ammonium transporters in D. discoideum (Dd), M. thermautotrophicum (Mt), E. coli (Ec), S. cerevisiae (Sc), C. reinhardtii (Cr), C. elegans (Ce), D. melanogaster (Dm), X. laevis (Xl), H. sapiens (Hs), and A. thaliana (At). The scale indicates the number of substitutions per site. (B) Disruption of amtA. A blasticidin resistance marker (bsr cassette) replaced the second intron of the amtA gene by homologous recombination. Exons are indicated by white boxes. B, Hc, and V indicate BamHI, HincII, and EcoRV restriction sites, respectively. (C) The amtA disruption was confirmed by Southern blotting, using the probe shown in panel B. Genomic DNA isolated from wild-type and amtA− cells was analyzed after digestion with HincII or BamHI and EcoRV (B+V).

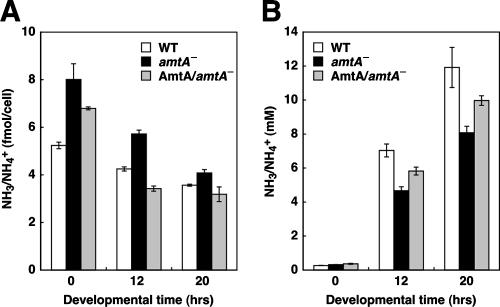

To determine whether AmtA regulates ammonium homeostasis, we disrupted the amtA gene in Dictyostelium by homologous recombination. The disruption was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 1B and C). Wild-type cells showed 5.1- and 3.5-kb DNA fragments generated by HincII digestion and by BamHI/EcoRV digestion, respectively. On the other hand, 6.2- and 4.6-kb fragments were observed in cells disrupted for the amtA gene. We measured levels of intracellular and extracellular ammonia/ammonium during growth and development using ammonia-specific electrodes (2, 8). We observed 5.24 ± 0.14 fmol of ammonia/ammonium per cell in wild-type cells during growth (Fig. 2A). In contrast, in amtA− cells, intracellular ammonium/ammonia levels were significantly increased. The mutants contained 8.0 ± 0.7 fmol of ammonium/ammonia per cell, showing an ∼1.5-fold increase. When we induced development by starvation, intracellular levels of ammonium/ammonia gradually decreased in wild-type cells during development. Although amtA− cells also showed a gradual decrease in ammonia/ammonium levels, intracellular levels of ammonia/ammonium in amtA− cells were much higher than those seen in wild-type cells at both the aggregation stage (12 h after starvation) and culmination stage (20 h). Increases in intracellular ammonia/ammonium levels could result from either overproduction of ammonia/ammonium or defects in its transport out of cells. Supporting the latter possibility, we found that extracellular levels of ammonium/ammonia were lower in amtA− cells (Fig. 2B). We confirmed that these phenotypes were caused by the loss of the amtA gene by expressing wild-type amtA in amtA− cells. All the phenotypes were significantly rescued by the expression of AmtA. These results clearly demonstrate that AmtA is required for normal ammonia homeostasis during growth and development.

FIG. 2.

AmtA is required for intracellular ammonia homeostasis. (A) Intracellular ammonia/ammonium levels. Cells were collected at 0, 12, and 20 h of development and homogenized, and the amounts of ammonia/ammonium were determined by an ammonia electrode. Values indicate means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) (n = 3). (B) Extracellular ammonia levels. Media were collected at the indicated time points, and the amounts of ammonia were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Values indicate means ± SEM (n = 3).

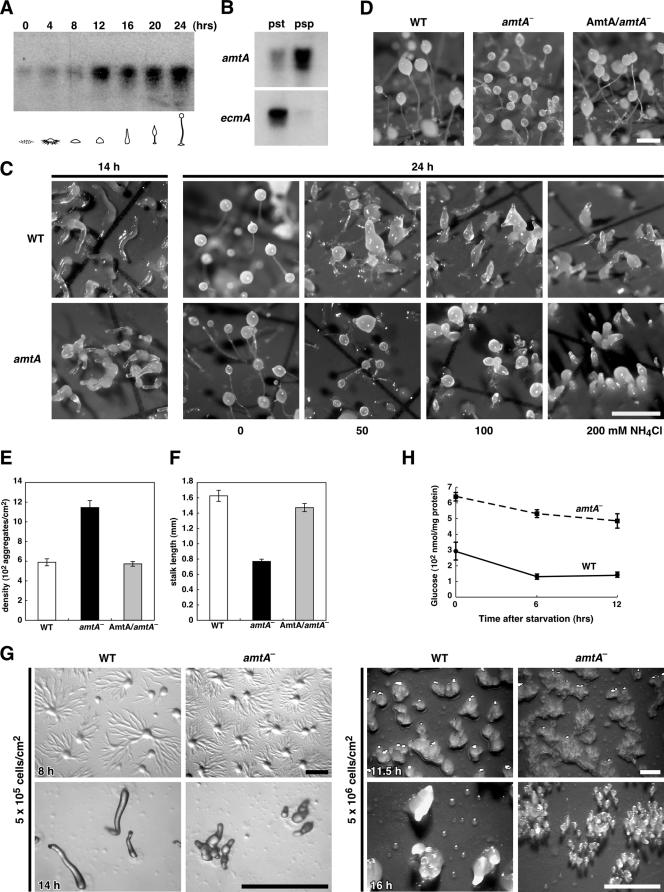

Consistent with a role for AmtA in ammonia homeostasis, we found that amtA mRNA (1.7 kb) is expressed during both growth and development using Northern blot analysis (Fig. 3A). The expression level increased continuously during development. This is in contrast with previous studies using reverse transcription-PCR that showed that amtA mRNA levels do not change during development (20). The apparent difference may result from different methods used to measure mRNA levels. Nevertheless, the previous study and our current study clearly demonstrate that AmtA is expressed during development. Furthermore, we confirmed the localization of amtA mRNA in prespore cells in slugs (20), using Northern blotting (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

amtA− cells display the aberrant morphology of fruiting bodies. (A) Poly(A)-containing RNAs were collected at the indicated time points and analyzed by Northern blotting with amtA cDNA as a probe. Five micrograms of poly(A)-containing RNAs were loaded in each lane. (B) amtA mRNA accumulates in prespore cells. Expression in respective cell types at the slug stage. Total RNA was extracted from prespore (psp) and prestalk (pst) cells in slugs. ecmA was used as a marker for prespore cells. (C) Effects of ammonia on culmination. Cells were developed in the absence of ammonia for 14 h and then transferred onto paper pads containing the indicated concentrations of NH4Cl. Photographs were taken 10 h after transfer. Bar, 1 mm. (D) amtA− cells produce many small fruiting bodies. Wild-type cells (WT), amtA− cells, and amtA− cells expressing amtA were plated on nitrocellulose filters to induce development and observed at 24 h. Bar, 0.5 mm. (E) Quantitation of aggregate density. Cells were plated on filters at a density of 5 × 106/cm2. After 12 h, aggregates in an area of 81 mm2 were counted. Values indicate means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) (n = 3). (F) Quantitation of stalk length. Values indicate means ± SEM (n ≥ 50). (G) Wild-type and amtA− cells were developed on nonnutrient plates for the indicated times. Compared to wild-type cells, amtA− cells show smaller aggregation territory sizes and increased group breakup. Cells were plated at densities of 5 × 105/cm2 and 5 × 106/cm2. Bar, 1 mm. (H) amtA− cells show higher glucose levels than wild-type cells. Cells were developed for 0, 6, and 12 h and analyzed for glucose levels. Values indicate means ± SEM (n ≥ 5).

We confirmed the results of previous studies (62) showing that amtA− cells normally grow both in shaking culture and on bacterial plates and that the time courses of development in wild-type and amtA− cells are similar, differentiating into fruiting bodies in 24 h upon starvation (data not shown). Wild-type and amtA− cells show similar sensitivities to ammonia in culmination (Fig. 3C). In Fig. 3C, cells were developed in the absence of NH4Cl, and then different amounts of NH4Cl were added to pads for further development. In addition, amtA− cells produced more aggregates and fruiting bodies than wild-type cells (Fig. 3D to F). In wild-type cells, the average density of aggregates was 593 aggregates/cm2. In contrast, amtA− cells produced 1,128 aggregates/cm2. The resulting fruiting bodies of amtA− cells were smaller than those of wild-type cells. The average stalk length in amtA mutants (0.77 mm) was almost half that in the wild-type (1.63 mm). The expression of wild-type AmtA in amtA− cells significantly suppressed those amtA− phenotypes. These results are consistent with the previous observation that AmtA plays a critical role in the number and size of aggregates and fruiting bodies (62). We also found that amtA− cells show smaller aggregation territory sizes and frequent group breakup (Fig. 3G). Since glucose has been suggested to increase aggregation size, we measured intracellular levels of glucose (34, 22). We found that glucose levels in amtA− cells were higher than those in wild-type cells (Fig. 3H). In contrast, protein amounts in wild-type and amtA− cells were indistinguishable (data not shown). These results suggest that the decreases of aggregation sizes in amtA− cells are affected mainly by ammonia, not glucose.

amtA− cells are hypersensitive to ammonia in early morphogenesis.

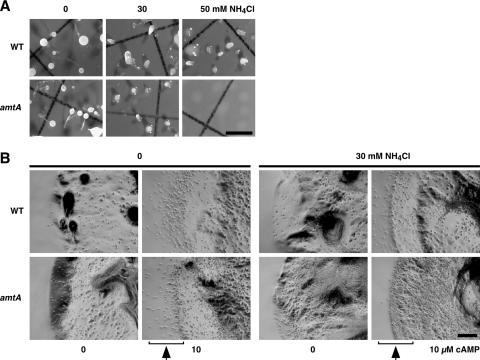

It has been shown that NH4Cl inhibits multiple steps in early developmental processes, including the aggregation and tip formation of aggregates (10, 23, 60). Since amtA− cells contain higher levels of ammonia/ammonium in early development than wild-type cells, we reasoned that mutant cells may be more sensitive to ammonia than wild-type cells. To test this idea, we induced development in amtA− and wild-type cells in the presence of ammonia. Cells were incubated throughout development on filter membranes containing 0, 30, or 50 mM of NH4Cl. As shown in Fig. 4A, in wild-type cells, ammonia inhibited aggregation and tip formation in a concentration-dependent manner. In the absence of NH4Cl, wild-type cells developed normally and formed fruiting bodies in 24 h after starvation. However, in the presence of 30 mM NH4Cl, wild-type cells were able to form only aggregates with pointed ends (tip formation) and did not differentiate further into fruiting bodies. In 50 mM NH4Cl, wild-type cells aggregated without tip formation. This result is not simply due to a delay in development. When we examined cells for prolonged periods of time (3 days), the cells still did not form fruiting bodies. In contrast, the mutants did not show tip formation of aggregates in 30 mM NH4Cl, although amtA− cells formed fruiting bodies in the absence of NH4Cl. Furthermore, 50 mM NH4Cl completely blocked aggregation in amtA− cells. These results show that the loss of AmtA makes cells hypersensitive to ammonia in aggregation and tip formation during development.

FIG. 4.

Effects of ammonia on tip formation, chemotaxis, and culmination. (A) Effects of ammonia on aggregation and tip formation. Wild-type and amtA− cells were placed on nitrocellulose filters and allowed to develop for 36 h in the presence of 0, 30, and 50 mM NH4Cl. Bar, 0.5 mm. (B) Effects of ammonia on chemotaxis toward cAMP. Wild-type and amtA− cells were plated on nonnutrient plates in the presence or absence of 10 μM cAMP and observed after 6 h. As indicated, plates contain 0 or 30 mM NH4Cl. We determined the original position of the edge immediately after the cells were spotted. Bar, 0.2 mm.

amtA− cells are defective in chemotaxis in the presence of ammonia.

The inhibitory effect of ammonia on the aggregation of amtA− cells suggests that ammonia suppresses chemotaxis toward cAMP in mutant cells. To test this possibility, we examined chemotaxis toward cAMP using a spot assay (Fig. 4B). Cells were spotted on the center of plates which contained 10 μM cAMP in the presence or absence of NH4Cl. Since there were no nutrients available on the plate, cells initiated development processes immediately after being spotted. Cells secrete phosphodiesterase and degrade extracellular cAMP, generating a difference in cAMP concentrations around the spot, with higher concentrations outside and lower concentrations inside. Along the cAMP gradient, cells move outward from the spotted area. If cells are defective in chemotaxis, they will stay inside the spotted areas. When wild-type and amtA− cells were spotted on plates containing 10 μM cAMP in the absence of NH4Cl, both wild-type and mutant cells developed normally. At the periphery of the spotted area, we found that many cells moved outward (Fig. 4B). This outward movement is chemotactic migration toward cAMP, since cells move out only when cAMP is present. On plates lacking cAMP, cells developed normally, but they stayed in the spotted area and did not move outward. However, when we added 30 mM NH4Cl to the plates, wild-type and amtA− cells showed distinct chemotactic behaviors. In the presence of 30 mM NH4Cl, wild-type cells were still able to develop, form aggregates, and move outward toward cAMP. In contrast, when amtA− cells were spotted, the mutant cells developed normally and formed aggregates, but they failed to move out of the spotted area. Our data suggest that cells lacking AmtA become more sensitive to NH4Cl during chemotaxis toward cAMP.

AmtA is required for normal spore formation.

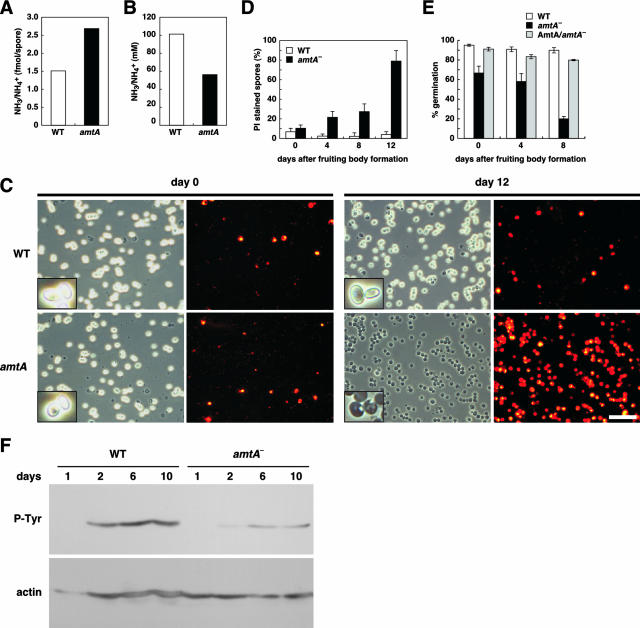

In Dictyostelium, the spore formation process is affected by ammonia through the regulation of cAMP-dependent PKA (30, 80). In addition, extra spore solution contains high concentrations of ammonium phosphate, which has been suggested to maintain the dormancy of spores (8, 9, 70). To determine whether AmtA is involved in ammonium homeostasis in spore and extra spore solution in sori, we collected sori, separated spores from extra spore solution by centrifugation, and measured levels of ammonia/ammonium. As shown in Fig. 5A, the levels of ammonia/ammonium increased twofold in amtA− spores. Wild-type spores contained 1.50 fmol of ammonia/ammonium per cell, whereas amtA− spores contained 2.69 fmol of ammonia/ammonium per cell. In addition, ammonia levels in extra spore solution decreased twofold in the mutant cells (Fig. 5B). Therefore, our data indicate that AmtA is required for normal ammonia homeostasis in spores.

FIG. 5.

AmtA is required for ammonia homeostasis, viability, and the germination of spores. Ammonia levels in spores (A) and spore mass solution (B). Three days after fruiting body formation, spore masses were collected and spores and sorus media were separated by centrifugation. The ammonia levels of each fraction were determined by an ammonia electrode. Values are normalized to 108 spores in 10 μl sori. (C) Spores were collected 0 and 12 days after fruiting body formation was completed and stained with PI. Spores were observed by phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy. Bar, 50 μm. (D) Quantitation of PI-positive spores. Spores were collected at the indicated periods of time after fruiting body formation and stained with PI. Spores that were stained with PI were counted. (E) Spores were collected at the indicated time points after the completion of fruiting body formation and examined for germination, as described in Materials and Methods. (F) Changes of tyrosine phosphorylation of actin with aging. Total proteins were prepared from 1-, 2-, 6-, and 10-day-old spores and immunostained with antiactin antibody and antiphosphotyrosine antibody.

To probe the role of AmtA in spores, we examined the morphology, viability, and germination rates of spores. We observed spore morphology using phase-contrast microscopy and checked spore viability using PI, which stains only dead spores (7, 50, 52). We found that the viability of spores lacking AmtA is compromised as the spores age. Immediately after the completion of fruiting body formation, both wild-type and mutant spores showed oval shapes and very few spores were stained by PI. However, as spores aged, amtA− spores appeared to be darker under the phase-contrast microscope (Fig. 5C and D). The majority of the dark spores were stained by PI, indicating that they were dead. Twelve days after fruiting body formation, 79.0% of amtA mutant spores were stained by PI, whereas only 4.4% of wild-type spores were PI positive. Furthermore, we found that germination rates were decreased in amtA− spores (Fig. 5E). Probably as a result of their compromised viability, amtA− spores are also defective in normal germination. Immediately after spore formation, ∼95% of wild-type spores germinated, whereas only 67% of amtA mutant spores germinated. Eight days after the completion of fruiting body formation, wild-type cells maintained a germination rate similar to that seen at day 0. In contrast, the germination rate of amtA− spores decreased as they aged. We found that only 20% of amtA− spores had germinated at 8 days. It has been shown that actins are organized into thick bundles in spores and are phosphorylated on tyrosine residues during the formation and maturation of spores (38, 59). Supporting the idea that amtA− cells are defective in normal spore formation, we found that tyrosine-phosphorylated actin levels decreased in amtA− spores (Fig. 5F). Therefore, our data indicate that AmtA is required for the formation and maintenance of viable spores.

DISCUSSION

A large number of studies have shown that ammonia regulates multiple processes during the development of Dictyostelium (45, 47, 78-80). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying ammonia homeostasis are poorly understood. Previous studies have suggested that AmtA functions in ammonia transport or ammonia sensing (20, 62). In this paper, supporting a role for AmtA in ammonium transport, we have shown that AmtA is required for normal ammonia homeostasis in Dictyostelium during growth and development. Our data strongly suggest that AmtA is involved in the excretion of ammonia/ammonium from cells. Supporting our conclusion, cells lacking AmtA accumulate ammonia/ammonium. The impairment of ammonium efflux results in a reduction in extracellular levels of ammonia/ammonium. Furthermore, intraspore levels of ammonia/ammonium are also highly increased in amtA mutants. Since the extracellular levels of ammonia/ammonium are slightly higher than the intracellular levels in Dictyostelium, AmtA might actively transport ammonium out of cells. Although our data suggest that AmtA is an important ammonium transporter in development, they do not rule out the possibility that AmtA also functions in ammonia sensing, as previously proposed (62).

Previous studies have shown that AmtA is important for the morphogenesis of fruiting bodies and for resistance to high concentrations of ammonia in culmination (62). Our study confirmed the previous findings and further identifies three additional developmental processes which involve AmtA-mediated ammonia homeostasis, including chemotaxis, tip formation, and spore formation. At the beginning of development, single cells undergo chemotaxis toward aggregation centers, which release the chemoattractant cAMP, leading to the formation of multicellular aggregates. We found that AmtA affects the sensitivity to ammonia in inhibition of chemotactic migration toward cAMP. amtA− cells fail to undergo chemotaxis in the presence of NH4Cl. Since the concentrations of NH4Cl that block chemotaxis do not inhibit the normal development of amtA− cells, it is unlikely that the chemotaxis phenotypes result simply from developmental defects. In addition, in our experiments, we examined chemotaxis toward exogenously added cAMP. Therefore, the observed chemotaxis defect is not due to the inhibition of the production and secretion of cAMP by ammonia. Rather, we suggest that ammonia directly affects signaling pathways for chemotaxis. Supporting our hypothesis, it has been shown that ammonia affects intracellular pH and thereby inhibits chemotaxis (10, 19, 69). It is possible that intracellular pH is regulated at least partially by AmtA during chemotaxis. Since the morphogenesis of aggregates involves cAMP signaling (66), the impaired chemotaxis may result in defects in tip formation in aggregates in amtA− cells. Furthermore, at the final stage of development, amtA− cells formed much smaller fruiting bodies than those of wild-type cells, even in the absence of exogenously added ammonia. Many smaller fruiting bodies may result from incomplete chemotaxis, which could produce many smaller aggregates. Alternatively, it is also possible that ammonia homeostasis directly controls the size of the fruiting bodies by affecting the differentiation of spore and stalk cells.

One of our most interesting observations is that AmtA regulates ammonia levels in spores. We found that amtA− spores in fruiting bodies contained higher levels of ammonia/ammonium but that extracellular levels were decreased. In addition, amtA− spores were severely defective in viability, and these phenotypes became more severe as spores aged. It has been shown that ammonia in sori is critical for the formation and maintenance of spores (8, 9, 30, 70, 80). Thus, our studies demonstrate that AmtA is a critical regulator for ammonia homeostasis during spore formation. It is likely that the reduced viability of amtA− spores leads to their defect in germination. Unlike with cells lacking the histidine kinase dhkB, which are defective in spore dormancy and prematurely geminate in sorus (82), we did not observe premature germination in amtA− spores; it is unlikely that amtA− cells are unable to inhibit premature germination in sorus, but rather they seem to be defective in formation of fully resistant spores. It has been suggested that the organization of the actin cytoskeleton is important for the formation and stabilization of spores (38, 58, 59). During spore formation, a large fraction of actin molecules are phosphorylated on tyrosine residues and organized into thick bundles. This process is induced under PKA activity and later mediated by the MADS box transcription factor SrfA (16-18). We found that the level of tyrosine phosphorylation of actin remains low in amtA− spores, suggesting that ammonia homeostasis might regulate spore formation and stabilization by affecting the actin organization mediated by PKA and SrfA.

Our current study and previous study have shown that the disruption of AmtA does not cause the severe defects in the culmination step of aggregates on its own (62). Wild-type and amtA− cells showed similar sensitivities to exogenously added ammonia in culmination, suggesting that other ammonium transporters regulate ammonia levels at the initiation of culmination. Supporting this idea, previous studies showed that AmtC was important for the induction of culmination and that cells lacking AmtC failed to culminate and remained as slugs (20, 37). In contrast to AmtA, AmtC is proposed to function as a sensor which monitors ammonia levels and activates intracellular signaling. Consistent with this idea, AmtC is preferentially expressed at the tip region of slugs, where the culmination signal may be generated (20). Interestingly, the disruption of amtA in the amtC null strain restored the ability of cells to differentiate to undergo the culmination stage (62). In this study, we showed that amtA functions as an ammonium transporter, although it is possible that amtA controls the slug/culmination transition as an ammonia sensor. To determine whether AmtC functions as an ammonium sensor or transporter, it would be important to determine whether intracellular levels of ammonia are also altered in amtC− cells.

Members of the Amt/Mep/Rh family are found in all domains of life and involved in a variety of biological processes. In microorganisms, ammonia is a nutrient, and most Amt/Mep/Rh proteins participate in the uptake of ammonium into cells (11, 31, 36, 42, 49). In contrast, in animals, ammonia is a waste product resulting from amino acid catabolism (29). Rh proteins have been suggested to excrete ammonia to maintain intracellular homeostasis (3, 4, 32, 48, 55, 75), although several recent studies suggest that the substrate of Rh proteins is CO2, not ammonia (41, 54). Furthermore, yeast Mep2 ammonium permease has been shown to function as a sensor of ammonia, generating a signal to regulate pseudohyphal differentiation (21, 46). Mep2 may lack the ability to transport ammonium across membranes (46). In contrast to most organisms, which carry only one type of ammonium transporter among the three subfamilies (Amt alpha, Amt beta, and Rh groups), Dictyostelium contains five ammonium transporters that belong to all three subfamilies. It would be tempting to speculate that Dictyostelium uses the different functions of ammonium transporters, such as ammonium uptake, efflux, and sensing, to control its unique development.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hideko Urushihara (University of Tsukuba) and Charles K. Singleton (Vanderbilt University) for valuable suggestions and comments. We also thank the Dictyostelium cDNA project in Japan for providing cDNA clones.

Research was supported by a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society fellowship (3374-05) and an American Heart Association beginning grant-in-aid (0765345U) (M.I.), an American Heart Association scientist development grant (0730247N) (H.S.), and Johns Hopkins University (M.I. and H.S.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi, H., T. Hasebe, K. Yoshinaga, T. Ohta, and K. Sutoh. 1994. Isolation of Dictyostelium discoideum cytokinesis mutants by restriction enzyme-mediated integration of the blasticidin S resistance marker. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 205:1808-1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aeckerle, S., B. Wurster, and D. Malchow. 1985. Oscillations and cyclic AMP-induced changes of the K+ concentration in Dictyostelium discoideum. EMBO J. 4:39-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakouh, N., F. Benjelloun, B. Cherif-Zahar, and G. Planelles. 2006. The challenge of understanding ammonium homeostasis and the role of the Rh glycoproteins. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 13:139-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biver, S., S. Scohy, J. Szpirer, C. Szpirer, B. Andre, and A. M. Marini. 2006. Physiological role of the putative ammonium transporter RhCG in the mouse. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 13:167-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bloom, L., and R. R. Kay. 1988. The search for morphogens in Dictyostelium. Bioessays 9:187-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradbury, J. M., and J. D. Gross. 1989. The effect of ammonia on cell-type-specific enzyme accumulation in Dictyostelium discoideum. Cell Differ. Dev. 27:121-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornillon, S., C. Foa, J. Davoust, N. Buonavista, J. D. Gross, and P. Golstein. 1994. Programmed cell death in Dictyostelium. J. Cell Sci. 107:2691-2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotter, D. A., A. J. Dunbar, S. D. Buconjic, and J. F. Wheldrake. 1999. Ammonium phosphate in sori of Dictyostelium discoideum promotes spore dormancy through stimulation of the osmosensor ACG. Microbiology 145:1891-1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotter, D. A., D. C. Mahadeo, D. N. Cervi, Y. Kishi, K. Gale, T. Sands, and M. Sameshima. 2000. Environmental regulation of pathways controlling sporulation, dormancy and germination utilizes bacterial-like signaling complexes in Dictyostelium discoideum. Protist 151:111-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies, L., M. Satre, J. B. Martin, and J. D. Gross. 1993. The target of ammonia action in Dictyostelium. Cell 75:321-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Detsch, C., and J. Stulke. 2003. Ammonium utilization in Bacillus subtilis: transport and regulatory functions of NrgA and NrgB. Microbiology 149:3289-3297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunbar, A. J., and J. F. Wheldrake. 1995. Evidence for a developmentally regulated prespore-specific glutamine synthetase in the cellular slime mould Dictyostelium discoideum. Microbiology 141:1125-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunbar, A. J., and J. F. Wheldrake. 1997. Analysis of mRNA levels for developmentally regulated prespore specific glutamine synthetase in Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev. Growth Differ. 39:617-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunbar, A. J., and J. F. Wheldrake. 1997. Effect of the glutamine synthetase inhibitor, methionine sulfoximine, on the growth and differentiation of Dictyostelium discoideum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 151:163-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eichinger, L., J. A. Pachebat, G. Glöckner, M. A. Rajandream, R. Sucgang, M. Berriman, J. Song, R. Olsen, K. Szafranski, Q. Xu, B. Tunggal, S. Kummerfeld, M. Madera, B. A. Konfortov, F. Rivero, A. T. Bankier, R. Lehmann, N. Hamlin, R. Davies, P. Gaudet, P. Fey, K. Pilcher, G. Chen, D. Saunders, E. Sodergren, P. Davis, A. Kerhornou, X. Nie, N. Hall, C. Anjard, L. Hemphill, N. Bason, P. Farbrother, B. Desany, E. Just, T. Morio, R. Rost, C. Churcher, J. Cooper, S. Haydock, N. van Driessche, A. Cronin, I. Goodhead, D. Muzny, T. Mourier, A. Pain, M. Lu, D. Harper, R. Lindsay, H. Hauser, K. James, M. Quiles, M. Madan Babu, T. Saito, C. Buchrieser, A. Wardroper, M. Felder, M. Thangavelu, D. Johnson, A. Knights, H. Loulseged, K. Mungall, K. Oliver, C. Price, M. A. Quail, H. Urushihara, J. Hernandez, E. Rabbinowitsch, D. Steffen, M. Sanders, J. Ma, Y. Kohara, S. Sharp, M. Simmonds, S. Spiegler, A. Tivey, S. Sugano, B. White, D. Walker, J. Woodward, T. Winckler, Y. Tanaka, G. Shaulsky, M. Schleicher, G. Weinstock, A. Rosenthal, E. C. Cox, R. L. Chisholm, R. Gibbs, W. F. Loomis, M. Platzer, R. R. Kay, J. Williams, P. H. Dear, A. A. Noegel, B. Barrell, and A. Kuspa. 2005. The genome of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature 435:43-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escalante, R., and L. Sastre. 1998. A serum response factor homolog is required for spore differentiation in Dictyostelium. Development 125:3801-3808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Escalante, R., and L. Sastre. 2002. Regulated expression of the MADS-box transcription factor SrfA mediates activation of gene expression by protein kinase A during Dictyostelium sporulation. Mech. Dev. 117:201-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Escalante, R., Y. Yamada, D. Cotter, L. Sastre, and M. Sameshima. 2004. The MADS-box transcription factor SrfA is required for actin cytoskeleton organization and spore coat stability during Dictyostelium sporulation. Mech. Dev. 121:51-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feit, I. N., E. J. Medynski, and M. J. Rothrock. 2001. Ammonia differentially suppresses the cAMP chemotaxis of anterior-like cells and prestalk cells in Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Biosci. 26:157-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Follstaedt, S. C., J. H. Kirsten, and C. K. Singleton. 2003. Temporal and spatial expression of ammonium transporter genes during growth and development of Dictyostelium discoideum. Differentiation 71:557-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forsberg, H., and P. O. Ljungdahl. 2001. Sensors of extracellular nutrients in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 40:91-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao, T., C. Roisin-Bouffay, R. D. Hatton, L. Tang, D. A. Brock, T. Deshazo, L. Olson, W.-P. Hong, W. Jang, E. Canseco, D. Bakthavatsalam, and R. H. Gomer. 2007. A cell number-counting factor regulates levels of a novel protein, SslA, as part of a group size regulation mechanism in Dictyostelium. Eukaryot. Cell 6:1538-1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gee, K., F. Russell, and J. D. Gross. 1994. Ammonia hypersensitivity of slugger mutants of D. discoideum. J. Cell Sci. 107:701-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gregg, J. H., A. L. Hackney, and J. O. Krivanek. 1954. Nitrogen metabolism of the slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum during growth and morphogenesis. Biol. Bull. 107:226-235. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gross, J. D. 1994. Developmental decisions in Dictyostelium discoideum. Microbiol. Rev. 58:330-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gross, J. D., C. D. Town, J. J. Brookman, K. A. Jermyn, M. J. Peacey, and R. R. Kay. 1981. Cell patterning in Dictyostelium. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 295:497-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hames, B. D., and J. M. Ashworth. 1974. The metabolism of macromolecules during the differentiation of myxamoebae of the cellular slime mould Dictyostelium discoideum containing different amounts of glycogen. Biochem. J. 142:301-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hashimoto, Y., Y. Tanaka, and T. Yamada. 1976. Spore germination promoter of Dictyostelium discoideum excreted by Aerobacter aerogenes. J. Cell Sci. 21:261-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heitman, J., and P. Agre. 2000. A new face of the Rhesus antigen. Nat. Genet. 26:258-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hopper, N. A., A. J. Harwood, S. Bouzid, M. Veron, and J. G. Williams. 1993. Activation of the prespore and spore cell pathway of Dictyostelium differentiation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase and evidence for its upstream regulation by ammonia. EMBO J. 12:2459-2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howitt, S. M., and M. K. Udvardi. 2000. Structure, function and regulation of ammonium transporters in plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1465:152-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang, C. H., and P. Z. Liu. 2001. New insights into the Rh superfamily of genes and proteins in erythroid cells and nonerythroid tissues. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 27:90-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes, J. E., and D. L. Welker. 1988. A mini-screen technique for analyzing nuclear DNA from a single Dictyostelium colony. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jang, W., B. Chiem, and R. H. Gomer. 2002. A secreted cell number counting factor represses intracellular glucose levels to regulate group size in Dictyostelium. J. Biol. Chem. 277:39202-49208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawabe, Y., T. Enomoto, T. Morio, H. Urushihara, and Y. Tanaka. 1999. LbrA, a protein predicted to have a role in vesicle trafficking, is necessary for normal morphogenesis in Polysphondylium pallidum. Gene 239:75-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khademi, S., and R. M. Stroud. 2006. The Amt/MEP/Rh family: structure of AmtB and the mechanism of ammonia gas conduction. Physiology (Bethesda) 21:419-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirsten, J. H., Y. Xiong, A. J. Dunbar, M. Rai, and C. K. Singleton. 2005. Ammonium transporter C of Dictyostelium discoideum is required for correct prestalk gene expression and for regulating the choice between slug migration and culmination. Dev. Biol. 287:146-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kishi, Y., C. Clements, D. C. Mahadeo, D. A. Cotter, and M. Sameshima. 1998. High levels of actin tyrosine phosphorylation: correlation with the dormant state of Dictyostelium spores. J. Cell Sci. 111:2923-2932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitano, T., and N. Saitou. 2000. Evolutionary history of the Rh blood group-related genes in vertebrates. Immunogenetics 51:856-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knecht, D. A., S. M. Cohen, W. F. Loomis, and H. F. Lodish. 1986. Developmental regulation of Dictyostelium discoideum actin gene fusions carried on low-copy and high-copy transformation vectors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6:3973-3983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kustu, S., and W. Inwood. 2006. Biological gas channels for NH3 and CO2: evidence that Rh (Rhesus) proteins are CO2 channels. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 13:103-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li, X. D., D. Lupo, L. Zheng, and F. Winkler. 2006. Structural and functional insights into the AmtB/Mep/Rh protein family. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 13:65-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Linskens, M. H., P. D. Grootenhuis, M. Blaauw, B. Huisman-de Winkel, A. Van Ravestein, P. J. Van Haastert, and J. C. Heikoop. 1999. Random mutagenesis and screening of complex glycoproteins: expression of human gonadotropins in Dictyostelium discoideum. FASEB J. 13:639-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loomis, W. F. 1975. Dictyostelium discoideum: a developmental system. Academic Press, New York, NY.

- 45.Loomis, W. F. 1988. Signals that regulate differentiation in Dictyostelium, p.25-30. ISI atlas of science: immunology. Institute for Scientific Information, Philadelphia, PA.

- 46.Lorenz, M. C., and J. Heitman. 1998. The MEP2 ammonium permease regulates pseudohyphal differentiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 17:1236-1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mahadeo, D. C., and C. A. Parent. 2006. Signal relay during the life cycle of Dictyostelium. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 73:115-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marini, A. M., G. Matassi, V. Raynal, B. Andre, J. P. Cartron, and B. Cherif-Zahar. 2000. The human Rhesus-associated RhAG protein and a kidney homologue promote ammonium transport in yeast. Nat. Genet. 26:341-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marini, A.-M., S. Soussi-Boudekou, S. Vissers, and B. Andre. 1997. A family of ammonium transporters in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:4282-4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mitra, B. N., R. Yoshino, T. Morio, M. Yokoyama, M. Maeda, H. Urushihara, and Y. Tanaka. 2000. Loss of a member of the aquaporin gene family, aqpA affects spore dormancy in Dictyostelium. Gene 251:131-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morio, T., H. Urushihara, T. Saito, Y. Ugawa, H. Mizuno, M. Yoshida, R. Yoshino, B. N. Mitra, M. Pi, T. Sato, K. Takemoto, H. Yasukawa, J. Williams, M. Maeda, I. Takeuchi, H. Ochiai, and Y. Tanaka. 1998. The Dictyostelium developmental cDNA project: generation and analysis of expressed sequence tags from the first-finger stage of development. DNA Res. 5:335-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nuckolls, G. H., N. Osherov, W. F. Loomis, and J. A. Spudich. 1996. The Dictyostelium dual-specificity kinase splA is essential for spore differentiation. Development 122:3295-3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ozaki, T., M. Hasegawa, Y. Hamada, M. Tasaka, M. Iwabuchi, and I. Takeuchi. 1988. Molecular cloning of cell-type-specific cDNAs exhibiting new types of developmental regulation in Dictyostelium discoideum. Cell Differ. 23:119-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peng, J., and C. H. Huang. 2006. Rh proteins vs Amt proteins: an organismal and phylogenetic perspective on CO2 and NH3 gas channels. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 13:85-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Planelles, G. 2007. Ammonium homeostasis and human Rhesus glycoproteins. Nephron Physiol. 105:11-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ratner, D., and W. Borth. 1983. Comparison of differentiating Dictyostelium discoideum cell types separated by an improved method of density gradient centrifugation. Exp. Cell Res. 143:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 58.Sameshima, M., Y. Kishi, M. Osumi, D. Mahadeo, and D. A. Cotter. 2000. Novel actin cytoskeleton: actin tubules. Cell Struct. Funct. 25:291-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sameshima, M., Y. Kishi, M. Osumi, R. Minamikawa-Tachino, D. Mahadeo, and D. A. Cotter. 2001. The formation of actin rods composed of actin tubules in Dictyostelium discoideum spores. J. Struct. Biol. 136:7-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schindler, J., and M. Sussman. 1977. Ammonia determines the choice of morphogenetic pathways in Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Mol. Biol. 116:161-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schindler, J., and M. Sussman. 1979. Inhibition by ammonia of intracellular cAMP accumulation in Dictyostelium discoideum: its significance for the regulation of morphogenesis. Dev. Genet. 1:13-20. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Singleton, C. K., J. H. Kirsten, and C. J. Dinsmore. 2006. Function of ammonium transporter A in the initiation of culmination of development in Dictyostelium discoideum. Eukaryot. Cell 5:991-996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singleton, C. K., M. J. Zinda, B. Mykytka, and P. Yang. 1998. The histidine kinase dhkC regulates the choice between migrating slugs and terminal differentiation in Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev. Biol. 203:345-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.So, J. S., and G. Weeks. 1992. The effects of presumptive morphogens on prestalk and prespore cell gene expression in monolayers of Dictyostelium discoideum. Differentiation 51:73-78. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Traynor, D., R. H. Kessin, and J. G. Williams. 1992. Chemotactic sorting to cAMP in the multicellular stages of Dictyostelium development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:8303-8307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Urushihara, H., T. Morio, T. Saito, Y. Kohara, E. Koriki, H. Ochiai, M. Maeda, J. G. Williams, I. Takeuchi, and Y. Tanaka. 2004. Analyses of cDNAs from growth and slug stages of Dictyostelium discoideum. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1647-1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Urushihara, H., T. Morio, and Y. Tanaka. 2006. The cDNA sequencing project. Methods Mol. Biol. 346:31-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van Duijn, B., and K. Inouye. 1991. Regulation of movement speed by intracellular pH during Dictyostelium discoideum chemotaxis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:4951-4955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Virdy, K. J., T. W. Sands, S. H. Kopko, S. van Es, M. Meima, P. Schaap, and D. A. Cotter. 1999. High cAMP in spores of Dictyostelium discoideum: association with spore dormancy and inhibition of germination. Microbiology 145:1883-1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Walsh, J., and B. E. Wright. 1978. Kinetics of net RNA degradation during development in Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Gen. Microbiol. 108:57-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang, M., and P. Schaap. 1989. Ammonia depletion and DIF trigger stalk cell intact Dictyostelium discoideum slugs. Development 105:569-574. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Watts, D. J., and J. M. Ashworth. 1970. Growth of myxameobae of the cellular slime mould Dictyostelium discoideum in axenic culture. Biochem. J. 119:171-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weeks, G., and J. D. Gross. 1991. Potential morphogens involved in pattern formation during Dictyostelium differentiation. Biochem. Cell Biol. 69:608-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weiner, I. D. 2004. The Rh gene family and renal ammonium transport. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 13:533-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.White, G. J., and M. Sussman. 1961. Metabolism of major cell components during slime mold morphogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 53:285-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Williams, G. B., E. M. Elder, and M. Sussman. 1984. Modulation of the cAMP relay in Dictyostelium discoideum by ammonia and other metabolites: possible morphogenetic consequences. Dev. Biol. 105:377-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Williams, J. G. 1988. The role of diffusible molecules in regulating the cellular differentiation of Dictyostelium discoideum. Development 103:1-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Williams, J. G. 1991. Regulation of cellular differentiation during Dictyostelium morphogenesis. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1:358-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Williams, J. G., A. J. Harwood, N. A. Hopper, M. N. Simon, S. Bouzid, and M. Veron. 1993. Regulation of Dictyostelium morphogenesis by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 340:305-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yamada, Y., and M. Sameshima. 2003. Hypertonic signal promotes stability of Dictyostelium spores via a PKA-independent pathway. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 229:159-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zinda, M. J., and C. K. Singleton. 1998. The hybrid histidine kinase dhkB regulates spore germination in Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev. Biol. 196:171-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]